TRIBAL ENERGY FINANCE

DOE Actions Needed to Reduce Barriers for Tribes

Statement of Anna Maria Ortiz, Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, U.S. Senate

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Chairman Murkowski, Vice Chairman Schatz, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our recent work on the Department of Energy’s (DOE) tribal energy programs. My testimony summarizes our August 2025 report, Tribal Energy Finance: Changes to DOE Loan Program Would Reduce Barriers for Tribes.[1] This statement discusses (1) the status of applications to DOE’s Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP), (2) strengths and limitations of the program, and (3) ways to improve its design and implementation.

While considerable conventional and renewable energy resources exist throughout Indian country, tribal communities often face challenges to developing these resources.[2] These include a lack of access to capital and systemic barriers to accessing federal programs.[3] According to DOE, 86 percent of tribal lands with energy potential are undeveloped. Developing these resources through tribal energy projects could help address the nation’s energy needs and create economic development opportunities for some Tribes and their members.[4] For example, such projects can help Tribes lower their energy costs and create access to reliable energy, improve living conditions, fund government programs and services, increase employment, and reduce poverty within the Tribe and surrounding areas.

TEFP, administered by DOE’s Loan Programs Office (LPO), provides loans and loan guarantees for tribal energy development.[5] The program supports federally recognized Indian Tribes or tribal energy development organizations that develop energy resources, products, or services using commercial technology. TEFP is intended to support a broad range of energy development projects and activities. It is technology neutral, which means it offers financing for projects that use various types of energy technology such as electricity generation, transmission, or distribution facilities that use conventional or renewable energy sources; energy resource extraction, refining, or processing facilities; or energy storage facilities. These projects can be on or off tribal land, and applicants can include Tribes, tribal energy development organizations, and lenders that apply on behalf of Tribes.

To conduct this work, we reviewed relevant laws, regulations, agency policies, and guidance documents related to program applications, design, and implementation. We analyzed TEFP application documents and LPO data as of February 2025 to describe the status of applications since 2018.[6] We interviewed DOE officials, 12 potential participants (e.g., Tribes and lenders) that applied or considered applying to the program, and five tribal energy stakeholders (e.g., lenders, consultants, and nongovernment organizations). Our work was performed in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of our work is provided in our August 2025 report.

DOE Has Closed One Loan Guarantee, and More than Half of Applications are Inactive

From its first program solicitation in 2018 through July 2025, DOE received 20 TEFP applications for approximately $15 billion in loans and loan guarantees for various project types and amounts.[7] Loan and loan guarantee requests ranged from $23.7 million for a solar project to $8.7 billion for an ammonia production facility for low-carbon fuel. Proposed projects were located throughout the contiguous United States and Alaska.[8]

Of these 20 applications, DOE closed a $100 million loan guarantee in August 2024 for a solar and long-duration storage microgrid project on tribal lands of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians in California.[9] As of February 2025, 12 applications were inactive (i.e., put on hold, withdrawn, or abandoned). Progress on the remaining seven active applications was limited by a pause that began in January 2025 as the current administration reviewed the program.[10] In July 2025, Congress rescinded all unobligated program appropriations provided by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), reducing available funding.[11]

Many applications spent considerable time in the intake phases of the application process, and most active and inactive applications (16 of 20) remained in these phases as of February 2025 (see fig. 1). Time spent in intake ranged from 41 days to 821 days, as of February 2025. LPO officials told us that various factors, such as project readiness and the applicant’s familiarity with the application process, can influence how quickly an application progresses.

Figure 1: Status of Applications to the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Tribal Energy Financing Program, as of February 2025

Note: Active applications are project applications undergoing review by DOE and include closed loans that DOE continues to monitor through the end of the loan term. Inactive applications are those that were withdrawn, abandoned, or otherwise put on hold. According to DOE officials, as of July 18, 2025, DOE had not received any new applications for the program.

TEFP Has Restrictions That Can Discourage Tribal Participation

Several aspects of the program’s design create significant financial barriers for Tribes that can discourage them from participating in the program, including the following:

· Limited project development assistance. LPO expects applicants to its programs to have projects that are well defined and significantly beyond the concept stage, according to LPO documents and officials. However, many Tribes do not have the upfront cash resources for early project development activities, which can be expensive, especially for larger-scale projects. One applicant told us a Tribe could spend a total of $10 million to $30 million to make a project “shovel ready.”

· Potentially high and unpredictable due diligence fees. DOE requires tribal applicants to pay fees and expenses for external legal and expert services (e.g., technical, financial, and environmental), as needed, that help DOE evaluate projects and requested financing. However, the level and unpredictability of these due diligence costs discourages Tribes from applying to TEFP, according to potential participants and stakeholders. For example, one Tribe that decided not to apply to the program said these costs could translate into millions of dollars. Another tribal applicant said the contractors DOE uses for TEFP legal work did not know enough about tribal law and energy projects, resulting in more hours billed to the Tribe.

Our report provides more detail about these and other challenges.

While LPO has taken some steps to help Tribes with these costs, we recommended doing more to further reduce the challenges Tribes still face. Actions LPO has taken include, for example, increased outreach, allowing project development costs to be included in TEFP loans on a project-by-project basis, and plans to develop a public finance “application pathway” that could reduce due diligence for lower-risk projects and shorten application time frames. However, Tribes often need immediate assistance and funding for project development activities and help identifying and accessing them. LPO offers this help on a case-by-case basis and has compiled an internal list of development grants used to support larger-scale energy projects. But it is unclear how comprehensively these options will address Tribes’ needs. DOE also has not finalized steps it is taking to reduce due diligence costs, such as details and guidance for the application pathway.

We recommended that DOE (1) identify and disseminate information on federal funding that could help Tribes develop large-scale energy projects ready for application and provide Congress information on gaps, and (2) further develop and implement options to revise the due diligence process to further reduce or eliminate fees on a project-by-project basis. In its comments on our report, DOE concurred with these two recommendations and described steps it plans to take to implement them.

Complex and Unclear Agency Processes Create Barriers That Can Derail Tribes’ Applications

DOE has taken steps to improve its outreach to Tribes about TEFP, but we identified barriers that can hinder Tribes’ ability to complete the application process and close on loan guarantees or direct loans. These barriers have created uncertainties for potential participants, lengthened application time frames, and may have reduced interest in the program.

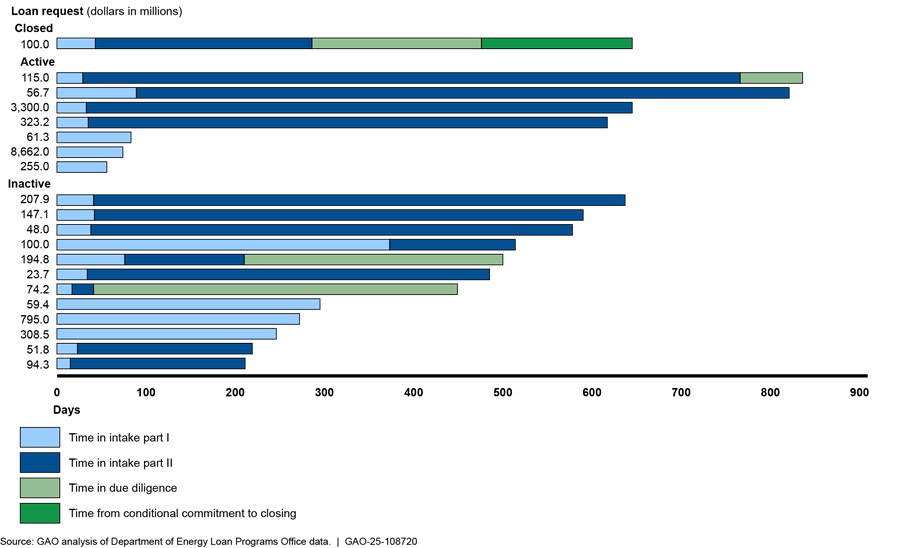

· Long application time frames. Lengthy application time frames have resulted in delayed project timelines, higher project costs, and loss of project partners, according to potential participants. For example, one tribal applicant said it lost its power purchaser and access to a multimillion-dollar bridge loan, making its project unviable. Our analysis of application data found that the median time in intake was 334 days (see fig. 2). The Viejas project, the only application to complete the full process, spent almost 2 years (645 days) from entering intake to closing. LPO officials noted that these timelines may include extended periods of guidance and preparation to assist applicants with their applications, as well as the applicant’s turnaround time to submit additional application support documents.

Figure 2: Loan Request Amount, Status, and Time Spent in the Application Process for Each Application to Department of Energy’s (DOE) Tribal Energy Financing Program, as of February 2025

Note: The Tribal Energy Financing Program had received 20 applications as of February 2025 and did not receive any new applications between then and July 18, 2025, according to DOE officials.

· Complex application process. The TEFP application process involves multiple stages of review and feedback, according to our review of program documents. LPO officials said they understood that tribal applicants might see the program as complex, but that to be successful, applicants must complete significant work upfront with the aid of legal counsel, engineering firms, and consultants. However, one potential participant said that because of this complexity, many Tribes cannot move through the application process without costly third-party assistance.

· Unclear program guidance. Tribal applicants we interviewed said they received different information from different LPO officials about certain program rules, such as equity requirements or whether TEFP could cover development costs. For example, one tribal applicant said they were told the loan could be used for development costs, such as environmental reviews, site control leases, and legal costs. However, LPO later told the applicant that such costs were not covered. When the applicant said it could no longer move forward with the loan without help with development costs, LPO agreed to include the costs. We reviewed LPO’s program documents and found that its guidance was not clear on some TEFP requirements. For example, requirements varied for loan sizes, equity, technology types, and outreach and intake.

· Limited tribal experience at DOE. Most LPO staff reviewing TEFP applications have limited experience in tribal energy finance, according to our analysis of LPO staffing practices. While LPO designated 12 of its 274 federal staff to focus primarily on TEFP or to work for the program on a recurring basis as of May 2025, most of these positions have not been filled consistently. Significant changes to LPO’s overall staffing levels and an ongoing government-wide hiring freeze are also likely to affect the availability of dedicated staff with expertise to work on tribal applications.[12] As of July 18, 2025, 43 of LPO’s 271 authorized positions were vacant, and 110 employees who had elected to resign on a deferred basis were on administrative leave until their resignation or retirement date, according to DOE officials. LPO officials and staff told us that without adequate experienced staff, LPO could continue to face challenges effectively processing Tribes’ applications—increasing application review times and requiring greater use of outside consultants to fill knowledge gaps. One tribal applicant also told us LPO staff resources were taken away from its application because LPO said it had inadequate staff for tribal projects.

LPO has taken some actions to address these barriers, according to LPO officials, but Tribes continue to face challenges. For example, LPO is revising its application processes, such as adjusting the rigor of its review and testing a new public finance application pathway; has identified timeliness goals; is verbally clarifying misconceptions; and began providing some staff with specific training on working with Tribes that addresses topics such as awareness of tribal law and government procedures. However, LPO officials said they were not yet certain whether their effort to revise the application process would be effective, had not developed the necessary documents to guide the effort, and did not have the staff with the needed expertise in public finance. LPO also had not documented information to correct misconceptions or updated internal and external guidance on the application process.

The barriers that still exist have created uncertainties for potential participants and lengthened application time frames, which may make it challenging for DOE to meet its timeliness goals and limit Tribes’ ability use TEFP to develop their own energy resources. Given ongoing changes to the program, including the loss of staff and rescission of funding, streamlining program processes and ensuring there are designated program staff with appropriate knowledge of tribal energy finance to review applications is particularly important. We recommended that DOE take steps to (1) reduce the length and complexity of the application process, (2) clarify program guidance, and (3) maintain designated staff.

In its comments on our report, DOE also concurred with these three recommendations and described steps it plans to take to implement them.

In conclusion, fully implementing all of our recommendations would help DOE address the barriers we identified and ensure more Tribes can access and leverage TEFP to generate important economic and energy development opportunities for their communities, as well as nationwide energy benefits.

Chairman Murkowski, Vice Chairman Schatz, and Members of the Committee, this concludes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to answer any questions you have at this point.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgements

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Anna Maria Ortiz, Director, OrtizA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Paige Gilbreath (Assistant Director), Courtney Tepera (Analyst-in-Charge), Marcia Carlsen, Katherine Chambers, Tara Congdon, William Gerard, Serena Lo, Karla Springer, Sara Sullivan, Swati Thomas, and Jack Wang.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Tribal Energy Finance: Changes to DOE Loan Program Would Reduce Barriers for Tribes, GAO‑25‑107441 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 11, 2025).

[2]As of August 2025, there were 574 federally recognized Tribes in the contiguous United States and Alaska. Federally recognized Tribes have a government-to-government relationship with the United States and are eligible to receive certain protections, services, and benefits by virtue of their status as Indian Tribes. For the purposes of this statement, we use the term “Tribes” to refer to any Indian tribe, band, nation, or other organized group or community, including any Alaska Native village or regional or village corporation as defined in or established pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which is recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided by the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians.

[3]See GAO, Tribal Energy: Federal Assistance to Support Microgrid Development, GAO‑24‑106278 (Washington, D.C.: July 22, 2024); and Tribal Issues: Barriers to Access to Federal Assistance, GAO‑25‑107674 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 3, 2024).

[4]U.S. Department of Energy, National Renewable Energy Lab, Techno-Economic Renewable Energy Potential on Tribal Lands, NREL/TP-6A20-70807 (Golden, Colo.: 2018); “Department of Energy Makes Up to $11.5 Million Available for Energy Infrastructure Deployment on Tribal Lands,” news release, February 16, 2018, https://www.energy.gov/articles/department‑energy‑makes‑115‑million‑available‑energy‑infrastructure‑deployment‑tribal‑lands; and National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “NREL Supports Native American Tribes in Clean Energy Transformational Leadership,” news release, March 30, 2016, https://www.nrel.gov/news/features/2016/24665.html.

[5]The Energy Policy Act of 2005 created the Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program, which initially only provided loan guarantees. Pub. L. No. 109-58, tit. V, § 503(a), 119 Stat. 594, 764–78 (codified in relevant part as amended at 25 U.S.C. §§ 3501, 3502(c)). The program was first funded in 2017; see Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2017, Pub. L. No. 115-31, 131 Stat. 135, 313 (2017). In 2022, it was expanded to allow direct loans. DOE refers to the expanded program as the Tribal Energy Financing Program.

[6]In July 2025, DOE officials provided an update on the status of new applications to the program. We incorporated this information into the report where appropriate.

[7]In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) increased TEFP’s loan authority from $2 billion to $20 billion. An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to Title II of S. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 117-169, § 50145(b)(2), 136 Stat. 1818, 2046 (2022) (amending 25 U.S.C. § 3502(c)(4)).

[8]Our report provides additional information on energy technology type, requested loan amount, application status, and time spent in each phase of the application process for each TEFP application LPO has received since 2018.

[9]A loan or guarantee is closed when LPO and the applicant sign an agreement that finalizes it, and LPO begins to disburse funds to the applicant for the project. LPO considers closed loans active because LPO plans to monitor the loan or loan guarantee over its lifetime. The loan guarantee amount for the Viejas project was the actual obligated amount, based on data we received from LPO as of February 2025.

[10]E.O. 14154 of January 20, 2025, Unleashing American Energy, directed agencies to immediately pause disbursement of funds appropriated under the IRA or the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, pending a review of such disbursements. 90 Fed. Reg. 8353, 8357 (Jan. 29, 2025).

[11]Congress in the IRA appropriated $75 million for credit subsidy and to administer the program. Pub. L. No. 117-169, § 50145(a), 136 Stat.at 2045–46. In July 2025, Congress rescinded the unobligated balance of TEFP’s IRA appropriations in Public Law 119-21—commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. V, subtit. D, § 50402(b), 139 Stat. 72, 152. As a result, the program has only pre-IRA appropriations, if any remain unobligated, of $8.5 million. Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, Pub. L. No. 115-31, 131 Stat. 135, 313 (2017).

[12]For example, a February 2025 executive order directed agency heads to promptly undertake preparations to initiate large-scale reductions in force, among other steps. E.O. 14210 of February 11, 2025, Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Workforce Optimization Initiative, 90 Fed. Reg. 9669 (Feb. 14, 2025). In addition, a presidential memorandum extended a previously issued hiring freeze for executive branch agencies through October 15, 2025. Presidential Memorandum, Ensuring Accountability and Prioritizing Public Safety in Federal Hiring (July 7, 2025).