TERRORISM RISK INSURANCE ACT

Considerations for Reauthorization

Statement of Jill Naamane, Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

Statement for the Record to Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance, Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

A statement for the record to the Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance, Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Jill Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) requires the Department of the Treasury to administer a program in which the federal government would share some of the losses from a certified act of terrorism with private insurers. After an event is certified (determined to have met certain criteria), Treasury reimburses insurers for the federal share of losses, after insurers pay mandated deductibles.

The terrorism insurance market has been stable under the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program. Treasury reported in 2024 that the insurance is generally available and affordable.

In 2021, Treasury clarified that the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program can cover terrorism losses on eligible cyber policies. But certifying cyberattacks under TRIA can be challenging for three reasons:

1. Cyberattacks may not meet TRIA’s requirement that an attack be violent or dangerous to human life, property, or infrastructure.

2. Cyberattacks may not readily meet the TRIA requirement that attacks be part of an effort to coerce the U.S. population or government, or influence policy.

3. Cyberattacks may not meet the TRIA requirements that damage occur in the U.S. or in specific areas outside the U.S.

Additionally, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Federal Insurance Office have not completed an assessment on whether cybersecurity risks warrant a specific federal insurance response. GAO’s recommendations to both agencies to conduct such an assessment remain open. If Congress were to consider legislation for a federal cyber insurance response, GAO’s framework for providing federal assistance to private market participants could help inform its design, such as taking steps to mitigate moral hazard.

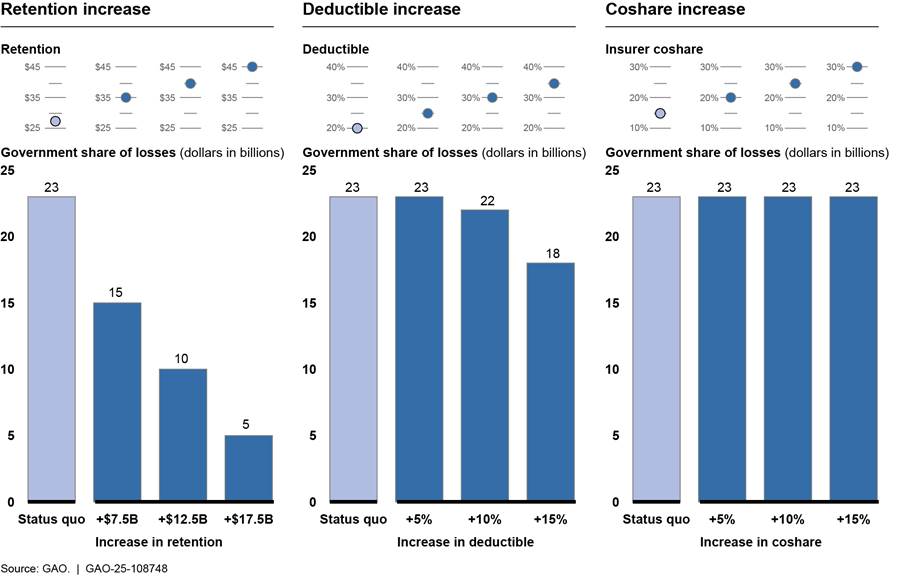

Past changes to TRIA reduced federal fiscal exposure, but some future changes may affect affordability and availability. Each reauthorization of TRIA through 2015 reduced the magnitude of the government’s explicit fiscal exposure, such as by increasing the insurer deductible from 7 percent of premiums in 2003 to 20 percent in 2020. GAO found changes to the industry aggregate retention would have a higher impact on federal fiscal exposure than changing the deductible or coshare parameters. Insurers told GAO they considered the potential effect of program changes in each reauthorization and modified risk-mitigation strategies, as needed. However, some program changes, such as those to the deductible and copayment share, and program triggers could affect the availability and affordability of terrorism insurance.

There could be significant disruptions to the insurance market if no federal terrorism risk insurance program existed. Our analysis of insurance data and information from Treasury and industry found TRIA’s federal backstop has played a role in stabilizing the terrorism insurance market. In the absence of a loss-sharing program, insurers likely would limit coverage or exit certain markets.

Why GAO Did This Study

In November 2002 Congress enacted TRIA to protect businesses, ensure widespread availability and affordability of insurance for terrorism risk, and respond to concerns about how absence of such coverage would affect the U.S. economy.

This statement for the record provides information on (1) the stability of the terrorism insurance market, (2) TRIA’s ability to cover cyber losses, (3) the impact of past TRIA changes on federal fiscal exposure and the potential impact of further changes, and (4) how the absence of TRIA could affect the terrorism insurance market.

This statement is based on GAO’s prior reports from May 2014 to June 2022. Detailed information on GAO’s objectives, scopes, and methodologies can be found in the published reports.

What GAO Recommends

In its June 2022 report, GAO made two recommendations that the Department of Homeland Security and Treasury assess cyber coverage, which remain open. Both agencies agreed with GAO’s recommendations. As of May 2025, the Department of Homeland Security told GAO it planned to continue collaborating with Treasury on a joint cyber insurance assessment. In March 2024, Treasury stated it had completed its initial assessment and determined to further explore the appropriate form of a federal cyber insurance response. As of April 2025, Treasury had not provided GAO with an update on when it would conclude its overall assessment or communicate the results to Congress.

Chairman Flood, Ranking Member Cleaver, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to submit this statement highlighting our work examining the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (TRIP).

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, insurers generally stopped covering terrorism risk because they determined the risk of loss was unacceptably high, relative to the premiums they charged. In November 2002 Congress enacted the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) in an effort to protect businesses, ensure widespread availability and affordability of terrorism risk insurance, and respond to concerns about the effect on the U.S. economy in the absence of such coverage.[1] In this statement, we collectively refer to the 2002 act and subsequent reauthorizations as TRIA, while we refer to the program itself as TRIP.[2]

TRIA requires the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) to administer a program in which the federal government would share some of the losses from an act of terrorism with private insurers. Not all incidents of terrorism will trigger reimbursements under the act. The Secretary of the Treasury must certify that an incident meets TRIA-specified criteria. After an event is certified, Treasury is to reimburse insurers for the federal share of losses, after insurers have paid statutorily mandated deductibles.

My statement provides information on the stability of the terrorism insurance market, TRIA’s ability to cover cyber losses, the impact of previous TRIA changes on federal fiscal exposure, the potential impact of further changes to TRIA, and how the absence of TRIA would affect terrorism insurance markets. This information is from our (1) 2014 report on changes to the terrorism insurance market and potential impacts of selected changes to TRIA, (2) 2017 report on alternative funding approaches, (3) 2020 reports on changes in explicit fiscal exposure and the impact of ending the program, and (4) 2022 report on the extent to which TRIP could provide a backstop to private insurance for catastrophic cyber losses.[3] Detailed information on our objectives, scopes, and methodologies can be found in the issued reports. We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The purposes of TRIA are to (1) protect businesses by addressing market disruptions and ensuring the continued widespread availability and affordability of commercial property/casualty insurance for terrorism risk; and (2) allow for a transitional period for the private markets to stabilize, resume pricing of such insurance, and build capacity to absorb any future losses, while preserving state insurance regulation and consumer protections.[4]

TRIP provides for shared public and private compensation for insured losses resulting from certified acts of terrorism. Under the current program, if an event were to be certified as an act of terrorism and insured losses exceeded $200 million, an individual insurer that experienced losses would have to satisfy a deductible before receiving federal coverage. An insurer’s deductible under TRIA is 20 percent of its previous year’s direct earned premiums in TRIA-eligible lines. After the insurer pays its deductible, the federal government would reimburse the insurer for 80 percent of additional losses and the insurer would be responsible for the remaining 20 percent. Annual coverage for losses is capped––neither private insurers nor the federal government cover aggregate industry insured losses in excess of $100 billion.[5]

After an act of terrorism is certified and once claims are paid, TRIA requires Treasury to recoup at least part of the federal share of losses in some instances. When insurers’ uncompensated insured losses are less than a certain amount (up to about $53 billion for 2025), Treasury must impose policyholder premium surcharges on commercial property/casualty insurance policies until total industry payments reach 140 percent of any mandatory recoupment amount. When the amount of federal assistance exceeds this mandatory recoupment amount, TRIA allows for discretionary recoupment.[6]

The Terrorism Insurance Market Has Been Stable with TRIA Support

Our prior analyses of insurance data and information from Treasury and industry stakeholders found that TRIA has supported a stable market that ensured coverage of risks that would otherwise be largely uninsured.[7] In a 2018 report, Treasury concluded that TRIA made coverage available and affordable and had supported a relatively stable market over the past decade. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, TRIA helps foster the existence of a broader market for risks that otherwise would be largely uninsured or borne by taxpayers. In its 2019 report, Marsh, an insurance risk-management company, noted TRIA’s federal backstop remained crucial to the continued stability of the terrorism risk insurance market.

More recently, in a 2024 report, Treasury reported that terrorism risk insurance is generally available and affordable.[8] Treasury noted direct premiums for the property/casualty sector increased 10 percent from 2021 to 2022, which was the second consecutive year of strong growth in premiums. Further, most commercial property owners continued to purchase terrorism risk insurance, including most places of worship.

TRIA Backstop Not Readily Applicable to Cyberattacks; More Action Needed to Assess If Federal Insurance Response Is Warranted

TRIA Backstop Designed for Terrorism Is Not Readily Applicable to All Cyberattacks

In June 2022, we reported Treasury issued a final rule in 2021 clarifying that TRIP can cover terrorism losses on eligible cyber policies.[9] But because TRIA was designed specifically as a federal backstop for losses from acts of terrorism, only losses from cyberattacks certified by Treasury as acts of terrorism would have TRIA coverage. As a result, even large cyberattacks that result in catastrophic losses would not be covered under TRIA if they were not certified as acts of terrorism.

Certifying cyberattacks under TRIA can be challenging for three key reasons:

4. Cyberattacks may not meet TRIA’s requirement that an attack be violent or dangerous to human life, property, or infrastructure. For example, a data breach or denial of service attack may result in stolen data or IT system disruption but may not be a violent act or dangerous to human life, property, or infrastructure.

5. Cyberattacks may not readily meet the TRIA criterion that attacks be part of an effort to coerce the U.S. civilian population or the government or influence policy. Although threat actors might use cyberattacks to coerce or affect the conduct of the U.S. government, many cyberattacks such as ransomware may be motivated only by financial gain.

6. Cyberattacks may not meet the TRIA requirement that damage occur in the United States or in specific areas outside the United States. Several industry stakeholders cited the potential example of a cyberattack affecting a U.S. company with a server in an overseas location as one that likely would not meet this criterion.

More Action Needed to Assess the Extent to Which Risks Warrant a Federal Insurance Response

In June 2022, we reported that the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Federal Insurance Office both had taken steps to better understand the financial implications of growing cybersecurity risks.[10] But neither agency had completed an assessment on whether these risks warranted an additional federal insurance response. Using a risk-management process to inform such an assessment could involve evaluating risks associated with systemic cyber incidents and developing an alternative to a federal insurance response. It also could examine how such responses would be triggered and funded or the appropriate amount of federal support or financial assistance. Such information could be helpful to Congress for considering policy options and tradeoffs.

We made recommendations to both the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Federal Insurance Office to conduct a joint assessment for Congress on the extent to which risks to the nation’s critical infrastructure from catastrophic cyberattacks warranted a federal insurance response. Both agencies agreed with the recommendations, which remain open. The Department of Homeland Security told us that, as of May 2025, the agency planned to continue to collaborate with Treasury on a joint cyber insurance assessment.

In September 2022, Treasury published a request for information in the Federal Register to solicit comments related to a potential federal insurance response to catastrophic cyber incidents and received dozens of responses. In March 2024, Treasury stated it had begun its initial assessment of the potential need for a federal response to catastrophic cyber incidents and determined to further explore the appropriate form of a federal insurance response, in coordination with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.

In April 2025, Treasury stated that it had continued its research and engaged industry stakeholders, including by hosting a conference in May 2024 that included three panels of cyber insurance experts. As of April 2025, Treasury had not provided a timeline for when it planned to conclude its overall assessment or communicate the results to Congress.

Defined Criteria and Security Requirements Are Among Key Elements for a Federal Insurance Response

In June 2022, we reported that if Congress were to consider legislation for a federal cyber insurance response, our framework for providing federal assistance to private market participants could help inform its design.[11] Three of the eight principles we identified may be particularly important in any consideration of a federal insurance mechanism for cybersecurity risk:

· Problem definition and identification are critical. Defining the problem could include establishing criteria for the type and magnitude of cyberattack the federal program would cover. As with TRIP certification criteria for acts of terrorism, any criteria established for covered cyberattacks would need to balance risks to critical infrastructure operations with the potential level of federal fiscal exposure in the longer term.

· Interventions should protect government—and thus taxpayer—interests. Protecting government and taxpayer interests could involve minimizing exposure and losses by collecting an up-front fee or premium or establishing an industrywide recoupment mechanism, as TRIA requires. Measures also could involve ensuring that companies, particularly those with critical infrastructure functions, take appropriate steps to manage their cybersecurity risks.

· In providing assistance, the government should take steps to mitigate moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when entities take more risk than they otherwise would because of the presence of insurance or other financial assistance. A federal insurance backstop without any cybersecurity requirements or incentives could result in some policyholders relying on promised federal assistance rather than investing in strong cybersecurity controls. One proposed option would tie federal assistance for cyber-related losses to cybersecurity requirements.

Changes in Past Reauthorizations Decreased Fiscal Exposure and Provide Examples of Considerations for Future Changes

Explicit Fiscal Exposure Decreased Under Prior TRIA Reauthorizations

In 2020, we reported that each reauthorization of TRIA through 2015 had reduced the magnitude of explicit federal fiscal exposure.[12] For example, the program trigger for aggregate annual loses rose from $5 million in 2003 to $200 million in 2020.[13] The insurer deductible increased from 7 percent in 2003 to 20 percent for 2020, also reducing the federal share of payments.[14] The 2019 reauthorization extended the program until 2027, but did not make any changes to program parameters.

According to our 2020 analysis of Treasury data on insurer direct-earned premiums, federal losses following a terrorist event under the loss-sharing provision in effect in 2020 would be smaller than for a similar event under the provision in effect in 2015, across a variety of event sizes and subsets of insurers. And more of the federal losses would be recovered through mandatory recoupment.

When considering changes to programs parameters, our 2014 report found that increasing the industry aggregate retention amount would have a greater impact on reducing fiscal exposure than changing the deductible or coshare percentages.[15] The potential reduction to federal exposures was most pronounced in our scenario of a $50 billion loss and an increased retention amount. This scenario would approximate losses (in 2013 dollars) similar to those from the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Every $1 increase in the retention amount could result in an equal $1 decrease in federal exposure, when insured losses were more than the industry aggregate retention amount ($27.5 billion at that time). The insurers’ share of losses increased with any decrease in federal fiscal exposures.

According to this $50 billion loss scenario, under the 2014 program parameters the federal share of losses after mandatory recoupment would be $23 billion. If the industry aggregate retention amount were increased from $27.5 billion to $35 billion, as suggested by surplus levels in the industry, federal exposure could decrease to $15 billion. To achieve a similar reduction in the federal share of losses, the deductible would have to be increased from 20 to more than 35 percent. There was no observable change to federal exposure when the coshare was increased in this $50 billion loss example because of the mandatory recoupment amount. See figure 1.

Figure 1: Examples of Reductions in Estimated Fiscal Exposure by Increasing Program Parameters, $50 Billion Terrorism-Related Insured Loss Event in 2012

Note: This example assumes a terrorist attack that occurred in 2012 resulted in $50 billion of insured losses and affected the 10 largest commercial property/casualty insurers in Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA)-eligible insurance lines. The example also assumes all 10 insurers have an equal market share and that the event will have an equal impact on the TRIA-eligible insurance lines. The increases in the deductible and coshare represent percentage point increases, not percentage increases.

Prior Reports Found Insurers Adjusted to Changes, but Some TRIA Changes Could Affect Affordability and Availability

We previously reported that insurers have been able to adjust to program changes but some changes may affect the affordability and availability of terrorism insurance. For example, for our 2020 report, insurers told us they considered the potential effect of program changes in each reauthorization and modified risk-mitigation strategies, as needed.[16] Other industry stakeholders, including a broker and an industry association, told us that because program changes have been gradual and expected, insurance companies were able to adjust their coverage accordingly.

However, we also found that some program changes could affect the availability and affordability of terrorism insurance.

· Deductible and coshare. Most of the insurers we surveyed for our 2014 report said that increases to the deductible (then at 20 percent of previous year’s direct earned premium) or private-sector coshare (then at 15 percent) could affect insurer capacity and pricing.[17] For example, insurers commented that an increase in either parameter would result in their companies reevaluating their risk and likely reducing capacity or increasing policyholders’ premiums. Insurers also stated that increasing the deductible or private-sector coshare would bring many companies under rating agency scrutiny for risk concentrations, likely resulting in industry-wide reductions in terrorism exposure.

· Industry aggregate retention. In our 2017 report, we found changes in the 2015 reauthorization of TRIA incrementally shifted a greater share of losses from the federal government to insurance companies for 2016–2020.[18] One change increased the industry aggregate retention by $2 billion a year, which potentially shifted a portion of the federal share of losses from the discretionary recoupment provision to the mandatory provision.

· Recoupment time frames. Also in our 2017 report, we found different mandatory recoupment collection time frames from 2016 to 2020 could affect potential premium increases due to recoupment surcharges.[19] Although discretionary recoupment surcharges must not increase annual TRIA-eligible premiums by more than 3 percent, mandatory surcharges partly would be determined by deadlines for collecting mandatory recoupment. Longer mandatory recoupment collection periods could result in smaller price increases and impacts on affordability than shorter time frames.

· Program triggers. If the total losses from a certified act of terrorism were below the program trigger (currently $200 million), insurers could sustain losses larger than their TRIA deductible without receiving any federal coshare. Because the amount of the program trigger has increased over time, more insurers potentially face this scenario. For our April 2020 report, stakeholders told us that small insurers and those that offer workers’ compensation insurance are most affected by changes to the program trigger.[20] Although the market is currently stable, some insurers may leave the market to mitigate the risks of suffering losses that might not be subject to TRIA’s loss sharing, which could reduce the availability of insurance in certain markets.

Disruptions Likely Without Reauthorization or an Alternative Program

In 2020, we reported significant disruptions to the insurance market could occur if no federal terrorism risk insurance program existed.[21] As previously noted, our analysis of insurance data and information from Treasury and industry stakeholders showed TRIA’s federal backstop has played a role in stabilizing the terrorism insurance market. In the absence of a loss-sharing program, insurers likely would limit coverage, exit certain markets, or attempt to increase capacity, according to our review of reports from the federal government, researchers, and industry entities, and interviews with industry stakeholders. Some stakeholders also noted concerns that new building projects might be stalled if the law expired, similar to concerns after the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Chairman Flood, Ranking Member Cleaver, and Members of the Subcommittee, this concludes my statement for the record.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgements

If you or your staff members have any questions concerning this statement for the record, please contact Jill Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

GAO staff who made contributions to this statement for the record include Winnie Tsen (Assistant Director), Nicholas Jones (Analyst-in-Charge), Barbara Roesmann, and Jessica Sandler.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-297, 116 Stat. 2322 (2002). Originally scheduled to expire at the end of 2005, TRIA was amended and reauthorized in 2005 (extended to 2007), 2007 (extended to 2014), 2015 (extended to 2020), and 2019 (extended to 2027).

[2]Pub. L. No. 107-297, 116 Stat. 2322 (2002); Terrorism Risk Insurance Extension Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-144, 119 Stat. 2660 (2005); Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110-160, 121 Stat. 1839 (2007); Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-1, 129 Stat. 3 (2015); Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019, Pub. L. No. 116-94 (2019);133 Stat 2534, 3026.

[3]See GAO, Terrorism Insurance: Treasury Needs to Collect and Analyze Data to Better Understand Fiscal Exposure and Clarify Guidance, GAO‑14‑445 (Washington, D.C.: May 22, 2014); Terrorism Risk Insurance: Market Challenges May Exist for Current Structure and Alternative Approaches, GAO‑17‑62 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 12, 2017); Terrorism Risk Insurance: Program Changes Have Reduced Federal Fiscal Exposure, GAO‑20‑348 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2020); Terrorism Risk Insurance: Market Is Stable but Treasury Could Strengthen Communications about Its Processes, GAO‑20‑364 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2020); and Cyber Insurance: Action Needed to Assess Potential Federal Response to Catastrophic Attacks, GAO‑22‑104256 (Washington, D.C.: June 21, 2022).

[4]15 U.S.C. § 6701 n. § 101(b).

[5]Once combined industry insured losses and federal payments reach $100 billion, no further payments are made. Insurers remain liable for amounts up to their deductible, even if the $100 billion cap is reached.

[6]Treasury may recoup additional amounts based on factors that include the ultimate cost to taxpayers of no additional recoupment after mandatory recoupment, marketplace conditions, affordability of commercial insurance for small and medium-sized businesses, and other factors Treasury considers appropriate.

[8]Department of the Treasury, Federal Insurance Office, Report on the Effectiveness of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program (Washington, D.C.: June 2024).

[9]GAO‑22‑104256. Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Updated Regulations in Light of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019, and for Other Purposes, 86 Fed. Reg. 30537 (June 9, 2021). In December 2016, Treasury issued interim guidance confirming that certain stand-alone cyber coverage written in a TRIP-eligible line of insurance was within the scope of TRIP, so that insurers were obligated to adhere to the ‘‘make available’’ and disclosure requirements under TRIA. The 2021 final rule codified in regulation Treasury’s 2016 guidance.

[10]The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, an agency in the Department of Homeland Security, is the lead federal agency for coordinating efforts to understand and manage risks to critical infrastructure. The Federal Insurance Office in the Department of the Treasury assists the Secretary with administration of TRIP. The Office also monitors the insurance sector, helps develop federal policy on prudential aspects of international insurance matters, and serves as an advisory member of the Financial Stability Oversight Council. See GAO‑22‑104256.

[11]See GAO‑22‑104256; and Financial Assistance: Ongoing Challenges and Guiding Principles Related to Government Assistance for Private Sector Companies, GAO‑10‑719 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 3, 2010). Building on lessons learned from prior financial crises, we identified eight guiding principles to help serve as a framework for evaluating large-scale federal assistance efforts and provided guidelines for assisting failing companies.

[13]TRIA did not have a program trigger until the 2005 reauthorization. However, the $5 million certification threshold acted as a program trigger because loss sharing would not occur unless the event was certified.

[14]The 2015 reauthorization required incremental reductions in the federal share of losses over 5 years.

[15]GAO‑14‑445. The industry aggregate retention amount is the lesser of the aggregate amount of insured losses for all insurers during the calendar year and the annual average of the sum of insurer deductibles for all insurers participating in the program for the prior 3 calendar years, as determined by the Treasury Secretary and according to regulation. For example, if the industry did not experience terrorism losses, the aggregate retention would be $0. If the industry experienced losses, the aggregate retention would be capped at the 3-year annual average of the insurer deductible. Treasury calculated the aggregate retention amount to be $40.9 billion in 2020.