FEDERAL LAND AND WATER MANAGEMENT

Additional Actions Would Strengthen Agreements with Tribes

Report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Natural Resources, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Natural Resources, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Anna Maria Ortiz at OrtizA@gao.gov or Cardell Johnson at JohnsonCD1@gao.gov

What GAO Found

Shared decision-making agreements with federal agencies enable Tribes to provide substantive, long-term input into natural and cultural resource management decisions for public lands. In treaties, Tribes ceded millions of acres of their territories to the federal government in exchange for certain commitments. Many of these areas are now public lands. Agencies committed in 2022 to ensure Tribes play an integral role in deciding how to manage federal natural resources. These agencies include the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and the Interior and their components, such as Agriculture’s Forest Service and Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). GAO identified 11 features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements, including a commitment to seeking consensus and a clearly outlined dispute resolution process. Fully incorporating these 11 features into policies would better position agencies to strengthen shared decision-making.

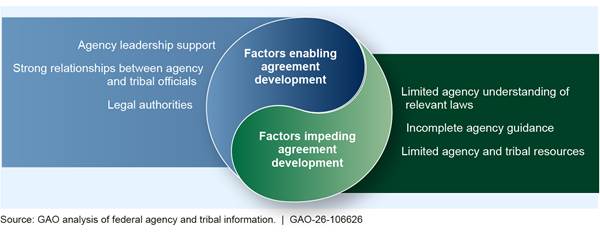

Agency and tribal officials GAO interviewed identified factors that facilitated agreement development, including having certain legal authorities. For example, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as amended, authorizes eligible Tribes to assume administration of certain Interior programs through a self-governance agreement. However, the Forest Service and NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries are not authorized to enter into this type of agreement, even though they manage natural resources similar to Interior. Providing these agencies a similar authority would allow for increased tribal input into management decisions, consistent with current administration priorities.

Agency and tribal officials also identified factors that impeded development of agreements, including limited agency understanding of legal authorities and incomplete guidance. Agencies have taken steps to address these factors, such as training staff working with Tribes. However, in light of significant federal workforce reductions that began in 2025, agencies have not conducted workforce planning to assess their capacity related to developing agreements. Doing so could enable better understanding of how to allocate agencies’ limited resources, address any skill gaps, and make strategic use of partnerships with Tribes.

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal agencies manage public lands, including national forests and parks, that are Tribes’ ancestral territories. Public lands retain special significance and importance to Tribes. Agencies collaborate with Tribes when meeting their missions and to fulfill unique federal trust and treaty responsibilities.

GAO was asked to examine issues related to agencies developing shared decision-making agreements with Tribes. This report identifies features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements and examines factors that facilitated or impeded their development, as well as agency actions to address impediments.

GAO reviewed agreements between federal agencies and Tribes, as well as federal laws, academic reports, and agency documents. GAO selected five shared decision-making agreements for in-depth analysis and interviewed the federal and tribal officials involved.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider three matters, including authorizing mechanisms for the Forest Service and NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to enter self-governance type agreements with Tribes. GAO is also making eight recommendations, including for departments to fully incorporate the 11 features into existing policies and agencies to assess staffing capacity and address any skill gaps related to developing agreements. Interior and NOAA generally agreed with our recommendations. Forest Service generally agreed with the report, but did not explicitly state whether it agreed with the recommendations. Commerce did not provide comments.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BLM |

Bureau of Land Management |

|

FWS |

Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

ISDEAA |

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as amended |

|

JSO |

Joint Secretarial Order 3403 |

|

NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

|

NPS |

National Park Service |

|

TFPA |

Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004, as amended |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 28, 2026

The Honorable Jared Huffman

Ranking Member

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

Dear Ranking Member Huffman:

For thousands of years, Tribes stewarded the lands and waters of what is now the U.S.[1] In treaties with the U.S., Tribes ceded millions of acres of their ancestral territories to the federal government in exchange for certain commitments.[2] Some of these ceded areas are now federally managed public lands and waters, including national forests, national parks, and wildlife refuges. These lands are home to natural and cultural resources that Tribes consider sacred and important. Because of these enduring historical, cultural, and spiritual connections, Tribes seek partnerships to help manage these resources with the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and the Interior and their subcomponent agencies. These subcomponents include the Forest Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS).

Federal agencies have affirmed their commitment to collaborating with Tribes when meeting their missions and to fulfill unique federal trust and treaty responsibilities.[3] Through Joint Secretarial Order 3403 (JSO), issued in November 2022, Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior committed to collaborate with Tribes to ensure that tribal governments play an integral role in decision-making regarding public lands and water management.[4] The JSO noted that honoring the treaty and trust responsibilities benefits these departments and agencies by incorporating tribal expertise and Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge. Further, the JSO notes that tribal collaboration must be implemented as a component of, or in addition to, public land management priorities and direction for recreation, timber, and habitat conservation, among other uses.[5]

The agencies have entered into a variety of agreements pursuant to the JSO, including “shared decision-making” agreements, which involve Tribes providing substantive input into federal natural and cultural resource management decisions over the long-term. You asked us to review issues related to federal agencies engaging with Tribes to develop shared decision-making agreements. This report examines the (1) features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements, (2) factors that facilitated the development of these agreements, and (3) factors that have impeded the development of these agreements and actions that federal agencies have taken to address these factors.

To address all three objectives, we identified initial lists of features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements and factors that facilitated and impeded their development through an iterative process. We started by researching about federal-tribal agreements online to identify features that are characteristic of shared decision-making and any factors that facilitate and impede their development. We also attended a tribal forestry symposium and conducted preliminary interviews with agency and tribal officials and individuals knowledgeable about the agreement development process and relevant laws. We identified features and factors in approximately 10 sources, including two academic reports, a Congressional Research Service report,[6] and tribal and federal agency summaries of a tribal consultation and a listening session. To identify additional features that strengthen agreements, we assessed two federal-tribal agreements that interviewees and symposium attendees said were examples of shared decision-making agreements.[7] When we reviewed these sources, we documented statements that indicated the features that helped strengthen agreements and may enable better management of public lands and waters as well as statements that described factors that positively or negatively influenced the development of agreements.

To further support all three objectives, we selected five agreements for in-depth analysis out of about 40 agreements that agencies and Tribes provided us. Each of the five selected agreements included at least one federal agency in our review, tribal or Native Hawaiian community signatories, and met our definition of shared decision-making.[8] These agreements and signatories are not generalizable to all shared decision-making agreements but provide illustrative examples of these agreements and the signatories’ perspectives about them. Appendix I describes our agreement selection process. We conducted site visits to Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, and Minnesota to meet with signatories and other parties interested in developing shared decision-making agreements.

To further refine and finalize our list of features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements for our first objective, we discussed our initial list of features with the signatories to all our selected agreements, including the federal agencies—at the national and field office levels—and tribal and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials. We sought signatories’ perspectives to confirm that we had identified the important features and ensure we did not exclude features that strengthen agreements that our preliminary work had not identified. Signatories agreed that we had identified the features that strengthen agreements on our initial list, and we incorporated their input to adjust the language describing some of the features.

To further refine the factors that facilitated and impeded the development of shared decision-making agreements, we asked signatories to our selected agreements about the factors that affected their agreements’ development and incorporated their input into our initial lists of factors. To obtain perspectives beyond our selected agreements, we interviewed an additional 10 Tribes and one Alaska Native Corporation about factors that might have impeded their efforts to develop shared decision-making agreements with federal agencies.[9] We selected these Tribes and the Alaska Native Corporation by identifying an initial list based on our interviews with tribal organizations, agency officials, academics, and our reviews of congressional hearing transcripts, academic reports, and news articles.[10] We contacted a selection of 13 Tribes from the initial list to obtain geographic diversity, among other goals, and interviewed those that agreed to meet with us.[11]

We finalized our list of facilitating and impeding factors by grouping similar factors together.[12] In some cases, interviewees described a factor as both facilitating and impeding. We narrowed the final lists to include those factors that were within federal agencies’ purview to address (for the impeding factors), represent perspectives from different types of entities interviewed, and were relevant to developing shared decision-making agreements. To further inform our understanding of the factors on our final lists, we reviewed relevant laws, agency documents, and federal-tribal agreements.

We examined the actions that federal agencies have taken that address impeding factors by reviewing agency documents, including guidance documents and available training materials. We discussed these actions with federal agency officials at the national and field office levels, and the agency, tribal, and Office of Hawaiian Affairs signatories to our selected agreements. We assessed agency actions in light of key principles identified in our previous reports on strategic workforce planning because of significant changes in agencies’ funding and workforces that began in early 2025.[13]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2023 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Co-Stewardship, Shared Decision-Making, and Co-Management Agreements

Federal agencies have referred to involving Tribes in natural and cultural resources management as “co-stewardship.” Co-stewardship is a broad term that does not have a universally accepted definition, but agencies define it as including a wide variety of activities and levels of tribal involvement. For example, co-stewardship can refer to collaborative or cooperative agreements that involve Tribes implementing discreet projects, such as performing forest thinning. Co-stewardship can also include Tribes providing substantive input over the long-term into federal resource management decisions, such as helping develop resource management plans or managing ongoing programs. We refer to this type of co-stewardship as “shared decision-making” to provide clarity on the type of agreements we discuss in this report.[14]

Federal agencies distinguish co-stewardship from “co-management” but the term “co-management” also does not have a universally accepted definition.[15] Interior and NOAA define co-management as those circumstances in which federal statutes or courts have required agencies to delegate some aspect of federal decision-making over public lands and water management to a Tribe.[16] This might allow a Tribe to make certain decisions with federal agencies as equal partners. In contrast, agencies are required to retain final decision-making authority when entering into co-stewardship agreements, including shared decision-making agreements, because of the requirements in applicable statutes governing those agreements and certain legal doctrines.[17] Figure 1 shows the range of tribal involvement in federal natural and cultural resource management decision-making.

Figure 1: Range of Tribal Involvement in Federal Natural and Cultural Resource Management Decision-Making

Federally Recognized Tribes, Native Hawaiian Communities, and Other Entities Eligible to Enter into Shared Decision-Making Agreements

Several entities are eligible to enter into shared decision-making agreements with federal agencies. These include federally recognized Tribes, Native Hawaiian communities, and others, depending on the authorizing statute.

Federally recognized Tribes. The U.S. has a government-to-government relationship with Tribes. In addition, the federal government has a trust responsibility for Tribes and their citizens. This trust responsibility comprises both a general trust responsibility and a more specific responsibility for Tribes’ and their citizens’ trust funds and certain trust assets.[18] The trust responsibility is based on statutes, treaties, regulations, executive orders, and actions. The general trust responsibility extends to all agencies included in this review, whether tribal affairs are their primary responsibility or not. In addition, many treaties contain certain rights retained by the Tribes, such as hunting and fishing on lands and waters that Tribes ceded in treaties.[19]

Native Hawaiian communities. Native Hawaiians are the Indigenous people who settled the Hawaiian archipelago, exercised their sovereignty, and eventually formed the Kingdom of Hawaii.[20] Certain federal laws have established a special trust relationship between the U.S. and the inhabitants of Hawaii, but Native Hawaiians do not have a formal, organized government.[21] Interior refers to the relationship between the U.S. and Native Hawaiians as one of government to sovereign.[22] The Office of Hawaiian Affairs serves as a representative of Native Hawaiian communities in certain forums.[23]

Other entities. Tribes can form organizations or consortia that represent the interests of multiple Tribes, and those tribal organizations may enter into agreements with agencies as authorized by law. In addition, Alaska Native Corporations with individual Alaska Natives as shareholders are authorized to enter into certain agreements. These corporations own lands across Alaska that contain a variety of natural and cultural resources. The corporations are not governments or federally recognized Tribes, but they are treated as Tribes under certain laws.[24]

Tribal Self-Governance

For the past several decades, federal policy has supported greater tribal autonomy and control by promoting and supporting opportunities for increased tribal self-governance and self-determination. This has included enactment of federal laws that establish mechanisms for tribal self-governance. For example, Title IV of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as amended, (ISDEAA) authorizes Tribes to enter into self-governance compacts and annual funding agreements (self-governance agreements) with Interior to assume the administration of certain programs, services, functions, and activities that the agency would otherwise conduct.[25]

Self-governance agreements transfer control to tribal governments over funding and decision-making for federal programs, services, functions, and activities upon tribal request.[26] These agreements may not include programs where the statute establishing that program does not authorize the type of participation sought by the Tribe.[27] Generally, activities Tribes assume responsibility for administering in self-governance agreements are still subject to relevant federal laws and regulations, such as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended.[28] Tribes meeting eligibility criteria can negotiate with Interior to enter into these agreements.[29]

In certain circumstances, these self-governance agreements can include programs, services, functions, and activities administered by Interior’s non-Bureau of Indian Affairs components, such as BLM, FWS, and NPS, which are of special geographic, historical, or cultural significance to the Tribe.[30] As officials from a Tribe explained, self-governance agreements solidify and affirm the government-to-government relationship, respect tribal sovereignty, and empower Tribes by providing a mechanism to exercise their inherent decision-making authority.

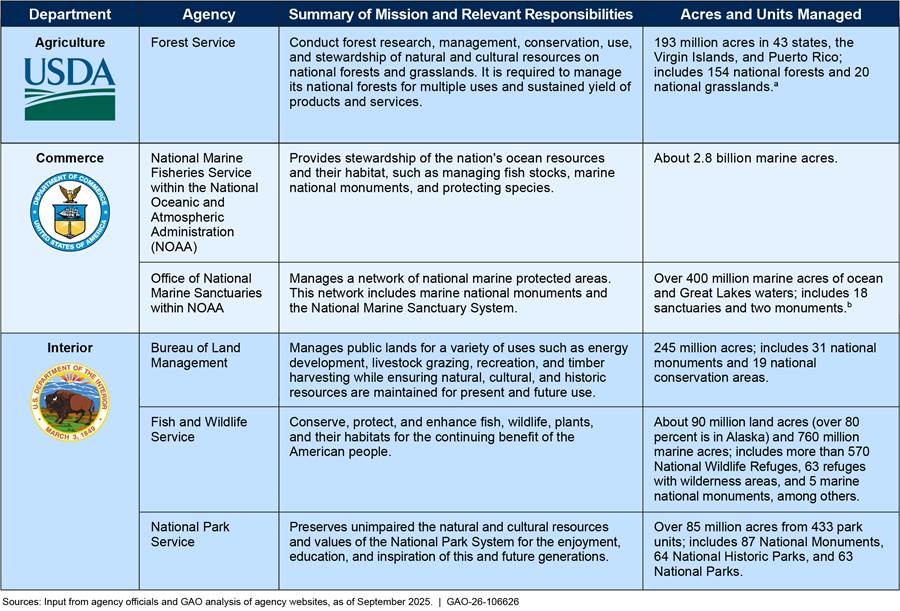

Federal Agency Management of Public Lands and Waters

The agencies within Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior in our review are authorized to pursue co-stewardship, including shared decision-making, as part of their broader responsibilities related to natural and cultural resource management, public access, and enjoyment of public lands and waters (see fig. 2).

aThe Forest Service also manages a network of 84 experimental forests and ranges for ecological research hosted on a combination of public and private lands.

bNational Marine Sanctuaries can include state waters. In these instances, NOAA officials said they work with states and Interior when taking management actions in these areas.

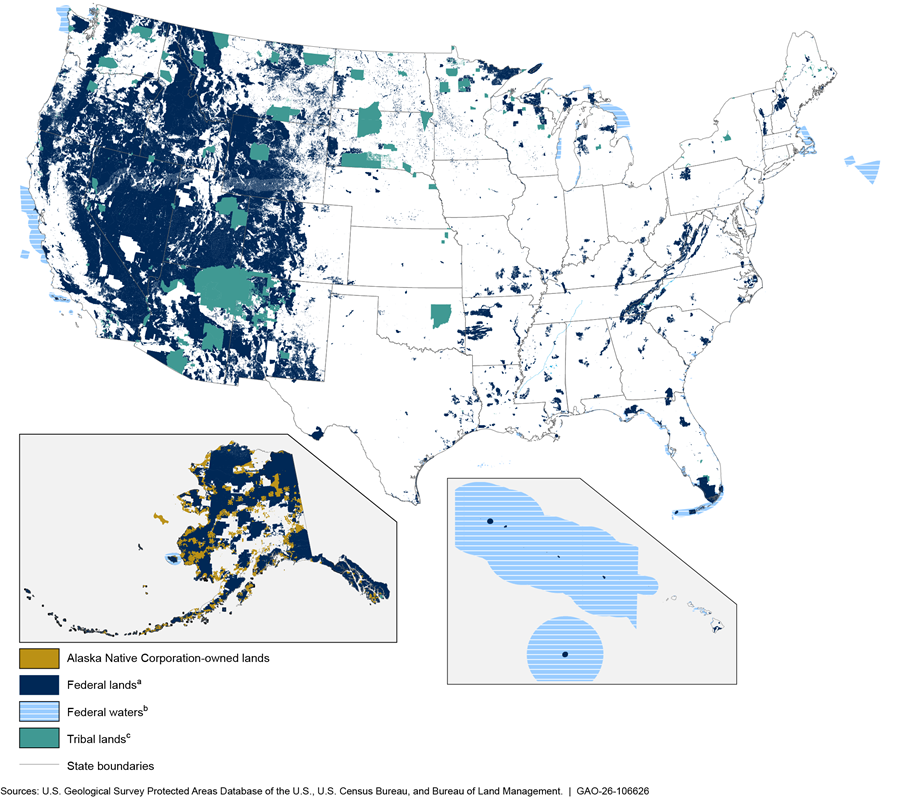

In many parts of the country, the public lands and waters that the federal agencies manage are located near or around reservations, Alaska Native Corporation-owned lands, and lands that the federal government holds in trust for the benefit of Tribes and tribal citizens (see fig. 3).

aFederal lands depicted on this map include lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service, National Park Service, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Federal lands located on U.S. territories are not depicted on this map.

bFederal waters depicted on this map include protected waters administered by the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service, National Park Service, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. For illustrative purposes, this map does not include all waters under federal jurisdiction, including those protected waters near U.S. territories and in parts of the South Pacific Ocean.

cTribal lands depicted on this map include reservation lands and off-reservation trust land. Reservations are land set aside by treaty, federal law, or executive order for the use of federally recognized Tribes. The federal government holds the legal title to lands held in trust for Tribes and their citizens (trust lands), but the Tribes or citizens retain the benefits of land ownership.

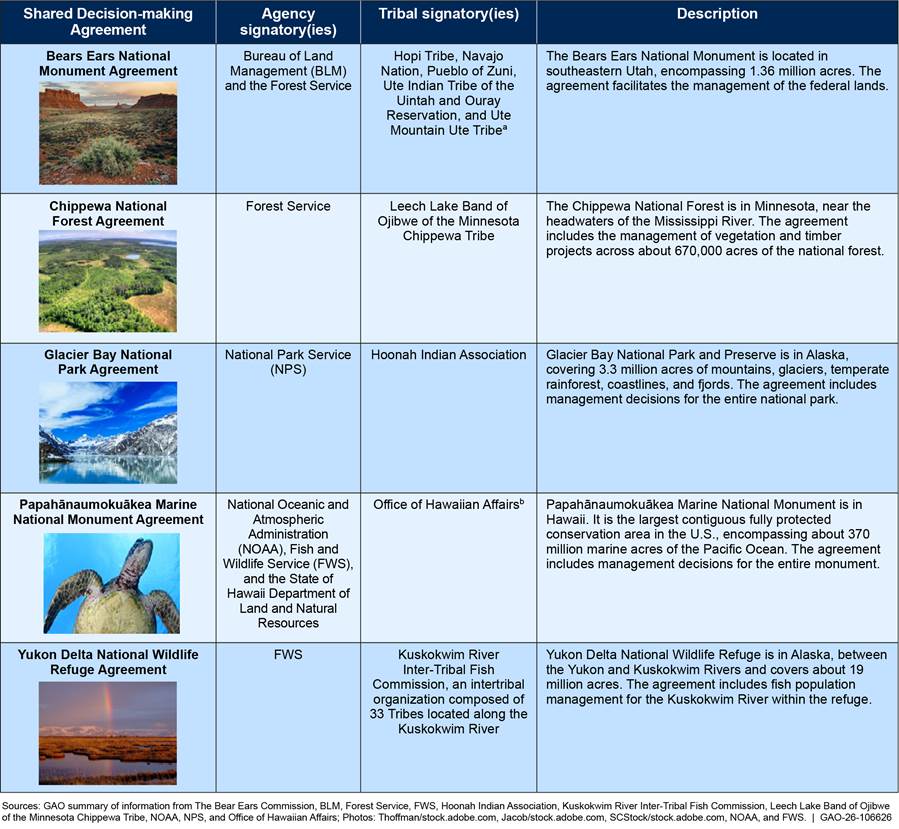

Five Selected Shared Decision-Making Agreements

The five shared decision-making agreements that we selected for in-depth review are between BLM, the Forest Service, FWS, NOAA, or NPS and Tribes or the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (see fig. 4). The agreements take different forms, including memoranda of understanding, memoranda of agreement, and cooperative agreements.

Figure 4: Five Selected Shared Decision-Making Agreements Between BLM, the Forest Service, FWS, NOAA, or NPS and Tribes or the Office of Hawaiian Affairs

aThese Tribes have representatives on the Bears Ears Commission whose work includes collaboratively managing the Bears Ears National Monument with BLM and the Forest Service.

bThe Office of Hawaiian Affairs is a state agency independent from the executive branch that serves as a representative of Native Hawaiians in certain forums.

Eleven Features Are Important to Include in Shared Decision-Making Agreements, and Policies Could Be Strengthened by Encouraging Their Adoption

We identified 11 features that strengthen shared decision-making agreements between federal agencies and Tribes or Native Hawaiian communities. Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior have developed policies that their component agencies can use to develop such shared decision-making agreements. However, moving forward, the usefulness of these policies could be improved by including additional discussion of these 11 features and encouraging their adoption into future agreements whenever applicable and to the extent legally permissible.

Eleven Features Strengthen Shared Decision-Making Agreements

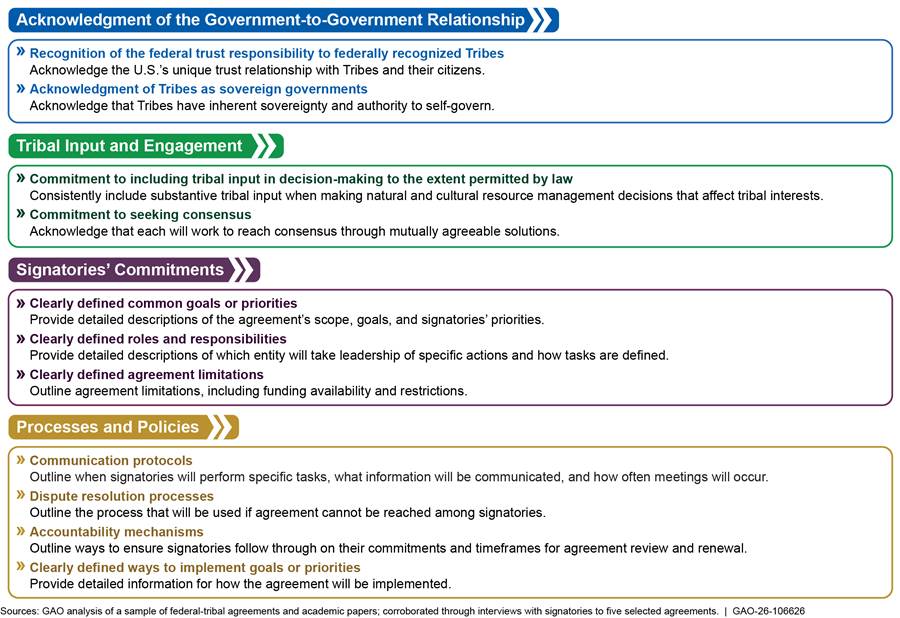

We identified 11 features that are important to include in shared decision-making agreements because they strengthen these agreements (see fig. 5). Including these features in the language of written agreements, to the extent legally permissible, memorializes partnerships and helps ensure these partnerships are sustained through staff turnover and changing priorities.

Figure 5: Features That Strengthen Shared Decision-Making Agreements Between Federal Agencies and Tribes

Signatories to our selected agreements said each of the features we identified provides various benefits. For example, signatories said features such as recognizing the federal trust responsibility to federally recognized Tribes are important because they communicate Tribes’ rights and justification for involvement. In addition, recognizing the federal trust responsibility can help set the stage for clear and respectful interactions with Tribes, according to FWS signatories to the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge agreement. Further, signatories to our selected agreements discussed the importance of including agreement limitations, such as if an agreement includes funding or not. A tribal signatory to the Glacier Bay National Park agreement said including agreement limitations in an agreement can prevent future issues and conflict.

While signatories noted that all 11 features strengthen agreements, they elaborated on several features, including a commitment to seeking consensus and a clear dispute resolution process.

Commitment to seeking consensus. Signatories to our selected agreements said a commitment to seeking consensus when making decisions is important because it helps ensure that all signatories’ perspectives are included. Seeking consensus in this context involves aiming to find mutual agreement on a course of action, even if it may not be the first preference of one of the signatories. For example, the Chippewa National Forest agreement outlines a framework in which the signatories commit to seeking consensus to achieve mutual landscape restoration goals. This framework includes a decision-making model intended to ensure the signatories reach mutually agreeable solutions about natural resource management, including commercial timber harvesting. Additionally, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument agreement states that the joint governing body responsible for managing the monument should seek consensus on all matters.[31]

We found that although shared decision-making agreements can include a commitment to seeking consensus, agencies must retain authority to make final decisions unless specifically authorized to delegate it to nonfederal partners.[32] In addition, according to Agriculture’s and Interior’s legal reports about implementing the JSO, these agreements cannot include inherently governmental functions for nonfederal partners, including Tribes or Native Hawaiian communities, to carry out.[33]

Agency officials said they aim to get as close to reaching consensus as possible within their existing legal authorities. This includes engaging with Tribes as equal partners until the point of making the final decision, when the agency is required to be the sole signer of final decision documents.[34] In addition, signatories to our selected agreements told us that in practice, they informally seek and reach consensus when making decisions. For example, according to the Glacier Bay National Park agreement signatories, they regularly make decisions together, such as by holding bi-weekly meetings and forming project-specific working groups.

In addition to seeking consensus, some Tribes want to guarantee agencies will incorporate tribal input into decisions by playing a larger role, such as being equal partners throughout the decision-making process under co-management agreements (see text box).

|

Co-Management Agreements Tribal officials said they support the use of co-management agreements with federal agencies in addition to shared decision-making agreements. Co-management means those circumstances in which federal statutes or courts have required agencies to delegate some aspect of federal decision-making over public lands and water management to a Tribe, according to agency documents. This could include making some final decisions together as equal partners and ensuring that agencies cannot override their tribal partners’ input, according to tribal officials. The National Congress of American Indians and other tribal organizations have expressed support for co-management and said that it could benefit agencies, Tribes, and the public. Specifically, a National Congress of American Indians resolution notes that co-management brings together the expertise of diverse perspectives to build a collective and participatory framework that has mutual benefits. Agency officials said they would need additional legal authority to enter co-management agreements with Tribes. Source: GAO analysis of tribal organization resolutions and interviews with tribal and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials | GAO‑26‑106626 |

Source: GAO analysis of tribal organization resolutions and interviews with tribal and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials

Dispute resolution processes. Signatories to our selected agreements said it is important to agree upon and document a process to follow if a dispute arises. A tribal signatory said that clearly outlining how dispute resolution mechanisms will work in practice can guide signatories through difficult situations and disagreements.

For example, the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge agreement outlines specific actions to take if the signatories cannot reach agreement on an issue. These actions include requesting a meeting with federal decision-makers, such as FWS’s Alaska Regional Director, or submitting a request to the Federal Subsistence Board—which consists of certain agency officials, such as the Alaska Regional Director of FWS, and members who possess personal knowledge of and direct experience with subsistence in rural Alaska, including three members nominated or recommended by federally recognized tribal governments. The agreement also notes that such requests should be addressed with urgency.

Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior Policies Could Be Strengthened by Encouraging Adoption of the 11 Features in Future Agreements

We found that Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior include some discussion of the 11 features in the policies that their component agencies can use to guide the development of shared decision-making agreements.[35] For example, in the JSO, these departments noted that dispute resolution mechanisms should be incorporated into agreements with Tribes.[36] In addition, Interior’s departmental manual on collaborative and cooperative stewardship states that in making management decisions related to federal lands and waters that impact Tribes, agencies should incorporate tribal input, including tribal knowledge.[37] This aligns with the key feature that calls for a commitment to including tribal input in decision-making to the extent legally permissible. Further, Agriculture’s legal report about implementing the JSO and Commerce’s tribal consultation and coordination policy both acknowledge the government-to-government relationship they have with Tribes.[38]

|

Including Features Could Help Avoid Pitfalls When Implementing Agreements Including the 11 important features in agreements may help avoid potential challenges that could arise once it is time to put the agreement into practice. For example, one of the signatories to the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument agreement noted that signatories did not consistently share key information necessary to support mutual decision-making. They said that more consistent, open communication during decision-making would have improved collaboration. In reviewing the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument agreement, we observed that it did not include specific communication protocols—a feature that outlines what information will be shared, how often meetings will occur, and through what mechanisms. Including this feature in the agreement could have helped mitigate these challenges. This underscores the importance of federal agencies ensuring such features are incorporated during agreement development, to support smoother implementation. Source: GAO analysis of documents and interviews. | GAO-26-106626 |

However, we also found that the Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior policies generally do not include all aspects of the 11 features we identified as strengthening shared decision-making. For example, these departments’ relevant policies do not include language regarding a commitment to seeking consensus with Tribes when developing these agreements or clearly defined ways to implement goals or priorities.

NOAA and Forest Service officials said they had not included all 11 features in their policies because they did not have access to our analysis when they developed them. Interior officials and a Forest Service official said they generally agreed that these features are important to include in agreements with Tribes, and a NOAA official said including these features in policy would be helpful moving forward. In addition, GAO’s leading practices for collaboration reflect several of the 11 features we identified.[39] For example, these leading practices also highlight the importance of clarifying roles and responsibilities and ensuring accountability during collaborative activities, including when documenting mutual commitments in written agreements such as shared decision-making agreements.

As departments update their existing policies, they could benefit from including a discussion of the 11 features we identified and encouraging their adoption into future agreements whenever applicable and to the extent legally permissible.[40] Doing so could strengthen shared decision-making agreements and better ensure that Tribes have substantive input into the management of public lands and waters. The 11 features could serve as a common starting point for agency and tribal officials’ negotiations and create stronger agreements. Moreover, incorporating the features into policies would also help safeguard against the loss of institutional knowledge when staff responsible for developing agreements depart the agencies.

Strong Relationships, Legal Authorities, and Other Factors Facilitated Agreement Development, but the Forest Service and NOAA Have Fewer Authorities Than Interior

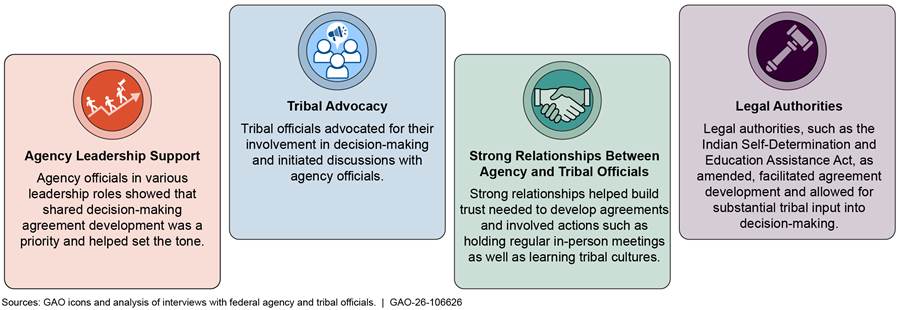

Agency leadership support, tribal advocacy, strong relationships between agency and tribal officials, and agencies’ legal authorities facilitated their ability to develop agreements, according to signatories of shared decision-making agreements (see fig. 6). Conversely, in some instances where these factors were not present, signatories told us it was more difficult to develop shared decision-making agreements. While legal authorities were generally cited as a facilitating factor, Forest Service and NOAA’s legal authorities for developing agreements are more limited than those of BLM, FWS, and NPS within Interior. As a result, the Forest Service and NOAA are limited in their ability to develop agreements with Tribes in certain circumstances.

Figure 6: Factors That Agency and Tribal Officials Said Facilitated the Development of Shared Decision-Making Agreements

Agency Leadership Support

Signatories said that support from senior agency leadership facilitated their development of agreements. Their support helped set the tone from top-level officials and demonstrated that these agreements were a priority for the agency. For example, agency officials said their leadership made it clear that pursuing agreements with Tribes was a priority, including by issuing the JSO and developing guidance to implement it.

Officials from Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe said the Forest Service Chief’s direct support facilitated the development of their agreement with Chippewa National Forest. Specifically, after the Tribal Chair requested to be involved in developing a new forest management plan that included updated timber harvest practices, the Forest Service Chief directed the Regional Forester to develop an agreement with the Tribe, going above and beyond the Tribe’s requests, according to tribal officials.

We found that having support from field office leadership was also helpful. For example, according to Hoonah Indian Association officials, the Glacier Bay National Park superintendent and other leadership championed tribal goals and priorities and pursued creative solutions to share certain management decisions with the Tribe.

Tribal Advocacy

Signatories said Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities advocating to be involved in decision-making helped facilitate their agreements. This advocacy included initiating discussions with agency officials and consistently pushing for their perspectives to be included. Tribal signatories also said they needed to continue their advocacy for months or years when developing the language in agreements so that it reflected their desired level of involvement in agreement implementation. For example, many years of tribal advocacy was instrumental in developing the Bears Ears National Monument agreement.[41] This advocacy prompted the 2021 Presidential Proclamation that re-established a commission composed of elected officers from Tribes to provide guidance and recommendations on monument management.[42]

Strong Personal Relationships

|

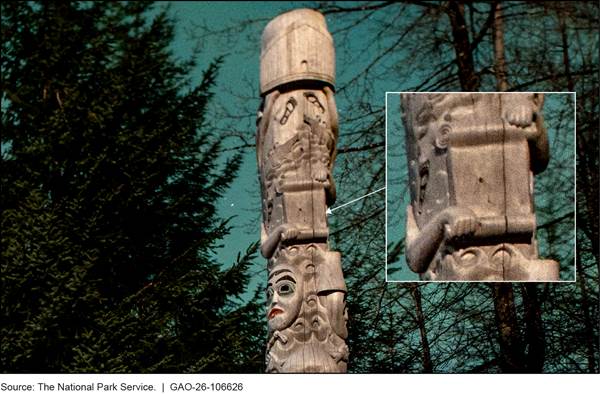

Building Relationships Through Collaboration In 2016, National Park Service (NPS) and the Hoonah Indian Association built the Huna Tribal House, a traditional Łingít structure. The Tribal House is located within Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and serves as a venue for tribal citizens to reconnect with their traditional homeland, way of life, and ancestral knowledge. It is a focal point for conveying the story of the Huna Łingít and their evolving relationship with NPS. To create the Tribal House, the Tribe and NPS partnered to develop a common vision. According to a tribal official, establishing the Tribal House helped the Tribe heal from historical trauma stemming from the removal of tribal citizens from the park. Efforts to build the Tribal House, along with other collaborative projects, in turn, facilitated the development of the Tribe and NPS’s 2016 shared decision-making agreement that covered a wide set of management decisions, including developing natural and cultural resource research programs.

Photo of the Huna Tribal House Sources: National Park Service website and GAO interview with the Hoonah Indian Association. | GAO-26-106626 |

Signatories said having already established strong personal relationships between agency and tribal officials facilitated the development of their agreements. They said it was very helpful when agencies prioritized in-person meetings, took the time to get to know tribal leaders and staff, and learned about tribal histories and cultures. Strong relationships served as a foundation to continue building the trust needed for agreement development.

For example, an agency signatory to the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge agreement said established relationships between FWS and the Tribes that compose the Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission were instrumental to agreement development. A tribal official said the signatories came together monthly to meet in person, which helped build connections.

In another example, tribal and agency signatories to the Glacier Bay National Park agreement said they built their relationship over many years of working together on various efforts, including the construction of the Huna Tribal House, a traditional structure located within the park boundaries. By working together on smaller individual projects over time, officials with the Tribe and NPS built trust. This enabled them to work better together on difficult issues, including the painful history of the federal government’s removal of tribal citizens from the area that later became part of the park.

This strong relationship then facilitated their 2016 shared decision-making agreement. In recognition of the relationship, an NPS official was naturalized as a tribal citizen, and the Tribe and NPS memorialized the evolution of the relationship in a healing totem pole, which included a scroll of papers, symbolizing their 2016 agreement (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: The Glacier Bay National Park Agreement Carved into Yaa Naa Néx Kootéeyaa, the Healing Totem Pole

Three Legal Authorities Facilitated Agreement Development, but Opportunities Exist to Expand the Forest Service and NOAA’s Authorities

Tribal and agency signatories to shared decision-making agreements we reviewed said that legal authorities facilitated agreement development. Such authorities include those provided by the Antiquities Act of 1906;[43] Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004, as amended (TFPA);[44] and Title IV of ISDEAA. However, the Forest Service and NOAA have more limited authorities compared to Interior’s agencies.

National Monument Proclamations Under the Antiquities Act of 1906

Presidential national monument proclamations under the Antiquities Act of 1906 facilitated agreement development, according to signatories to the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and Bears Ears National Monument agreements. Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials said that the President establishing the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and encouraging Native Hawaiian involvement in its management paved the way for the agreement’s development. In addition, the 2021 proclamation that re-established Bears Ears National Monument directed agencies to engage with Tribes. Specifically, it directed the Forest Service and BLM to jointly manage the monument and for the Bears Ears Commission to provide guidance and recommendations on the monument’s management.

Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004, as Amended

The TFPA was instrumental for developing agreements with the Forest Service, according to tribal signatories to two agreements.[45] The TFPA authorizes the Forest Service to enter into agreements with Tribes to carry out certain projects on federal lands that border or are adjacent to certain tribal lands.[46] These agreements can include activities to mitigate wildfire and other threats to tribal lands.[47]

TFPA agreements can involve substantive tribal input into agency decision-making over the long-term, such as on a 5-, 10-, or 20-year basis, according to Forest Service officials. For example, Forest Service officials told us that they used TFPA agreements as a mechanism to implement their Chippewa National Forest agreement. One Forest Service official said these TFPA agreements help improve vegetative conditions on the Chippewa National Forest. The projects to improve these conditions, such as restoring conifer trees, and the desired conditions are included in the Chippewa National Forest agreement.

|

Chippewa National Forest Tribal Forest Protection Act (TFPA) Agreements TFPA agreements between the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe and Chippewa National Forest have been used to achieve tribal desired vegetative conditions on the national forest using the best available science based on Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge and western science, according to tribal staff. Tribal staff also said that one of these TFPAs has improved habitat in the short-term for the snowshoe hare. The hare is important to the Tribe culturally and contributes to the local ecosystem’s balance by being a source of food for certain predators on the Tribe’s Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive Species List. Snowshoe hares prefer habitat, such as areas where trees are piled, offering a horizontal structure that provides protection from predators and the elements.

Photo of Restored Habitat for Snowshoe Hares Source: GAO. | GAO-26-106626 |

However, because of specific TFPA requirements, some Tribes are precluded from entering into TFPA agreements for projects on Forest Service lands even though they have maintained connections to those lands. Specifically:

· Definition of eligible tribal lands. To be eligible for TFPA agreements, Tribes must have trust or certain other land under their jurisdiction.[48] However, many Tribes, particularly those in Alaska, do not have such land. For example, although there are 227 Tribes in Alaska, few have land held in trust.[49] Also, Alaska Native Corporations meet TFPA’s definition of “Indian Tribe” but do not have eligible land or jurisdiction over any land.[50]

· Land adjacency requirement. To be eligible for TFPA agreements, Tribes must have eligible tribal lands that border or are adjacent to Forest Service lands.[51] The federal government forcibly removed certain Tribes from their ancestral homelands and relocated them to reservations that in some cases were hundreds of miles away. As a result, these Tribes’ current lands may not be adjacent to Forest Service lands that retain importance to them, and TFPA agreements cannot include projects on such national forest lands.

Tribes and agencies have noted the potential benefits that could result from removing these requirements to expand TFPA eligibility. For example, an Agriculture framing paper for a 2024 tribal consultation said removing the adjacency requirements would help maximize tribal self-determination opportunities.[52] This paper stated that the Forest Service could instead involve Tribes in TFPA projects on lands that have historical, geographic, or cultural significance to them. In addition, Tribes have said that removing these land eligibility and adjacency requirements would allow them to participate in projects that include shared decision-making on national forest lands.[53] Specifically, a tribal official we interviewed in Alaska told us the Tribe would like to participate in TFPA agreements to help manage lands administered by the Forest Service because it would provide more opportunities to work with the agency through government-to-government relationships.

Bills have been introduced in Congress in recent years that would amend the TFPA in various ways. For example, in February 2025, a bill was introduced that would expand the definition of eligible tribal lands to include lands held by an Alaska Native Corporation and eliminate the adjacency requirement, among other things.[54]

In testimony during a May 2025 Senate hearing, the Acting Associate Chief of the Forest Service said the agency is going to start relying more heavily on partners, such as Tribes, to assist in conducting the Forest Service’s work.[55] This includes management of national forest lands. In addition, in testimony during a July 2024 Senate hearing, a Deputy Chief of the Forest Service said that the TFPA has been a key authority for the agency, but it has limitations. The official said that changing its scope, such as eliminating the adjacency requirement, could help address these limitations.[56]

Amending the TFPA provisions that preclude some Tribes and Alaska Native Corporations from entering into TFPA agreements and authorizing TFPA agreements for national forest lands with a tribal nexus, such as those that have historical, geographic, and cultural significance to Tribes, would allow more Tribes and Alaska Native Corporations to participate in shared decision-making agreements.

Self-Governance Agreements Under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, as Amended

We identified two shared decision-making agreements between Tribes and BLM or FWS where tribal signatories said ISDEAA’s authority to enter into self-governance agreements facilitated their development.[57] Tribal signatories to these agreements, as well as other tribal and some agency officials we interviewed, said self-governance agreements provide several advantages:

· Funding. ISDEAA’s requirement that agencies provide the funding to implement programs and activities included in self-governance agreements was an appealing reason to develop agreements using this authority, according to tribal officials.[58] For example, a tribal official in New Mexico said their self-governance agreement with BLM included multi-year funding for the management of a national monument, which goes directly to the Tribe for things such as ranger salaries.[59] In addition, the director of an intertribal timber organization said Tribes can manage their forested land efficiently and with smaller budgets than federal agencies.

· Independence with decision-making. Tribal officials we interviewed said they pursue self-governance agreements whenever possible because this type of agreement enables the Tribe to be more independent and have a substantial say in decision-making. For example, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe developed a self-governance agreement in 2024 with FWS for the shared management of two national wildlife refuges in Washington State. Tribal officials said they used a self-governance agreement because it gave the Tribe significant decision-making authority and the flexibility to design programs and services.[60]

BLM and FWS can use ISDEAA’s self-governance authority, which facilitated agreement development. However, NOAA, including its Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, and the Forest Service do not have this or similar authority, although they also manage public lands and waters under other statutes.[61] Specifically, NOAA does not have any statutory authority to enter into any type of self-governance agreement with Tribes, although Tribes have expressed interest in using self-governance with NOAA, according to NOAA officials.

Further, the Forest Service has authority under ISDEAA to contract with Tribes to implement TFPA agreements, but these are not self-governance agreements.[62] In addition, the scope of the activities that can be included in these contracts is limited by the TFPA. The TFPA allows Tribes to manage activities and projects related to land restoration and risk reduction—including to reduce the risk of wildfire, disease, and other threats—but it does not apply to other Forest Service programs and activities. For example, TFPA agreements cannot include comprehensive management planning and wildlife or fisheries habitat management. However, tribal officials told us they would like to take on a greater role in managing Forest Service lands than the TFPA allows, including this kind of broader management.[63]

Forest Service District Rangers and NOAA officials we interviewed said that being able to enter into self-governance type agreements with Tribes could better position them to meet the agencies’ goals. For example, one Forest Service District Ranger said the ability to enter into self-governance type agreements would better support the agency’s goal to strengthen government-to-government relationships with Tribes. National level Forest Service officials said they did not oppose having authority to enter into self-governance type agreements but told us that any such authority should be tailored to the agency’s specific mission and responsibilities.[64] NOAA officials said their lack of authority to enter into self-governance type agreements is a barrier to implementing their commitments in the JSO and contributed to NOAA developing fewer agreements than other agencies.

Federal law has been amended several times to establish mechanisms for additional agencies to enter into self-governance type agreements with Tribes.[65] This trend could be continued by authorizing a mechanism for the Forest Service and NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to enter into self-governance type agreements with Tribes that enable them to share decision-making responsibility for the management of public lands and waters, to the extent legally permissible. This would enable eligible Tribes to enter into self-governance type agreements that could include Tribes assuming the administration of certain programs like they can with BLM, FWS, and NPS. Doing so would advance tribal self-determination and could enable solutions that incorporate Tribes’ unique knowledge, experience, and capabilities in specific places while helping agencies meet their goals.

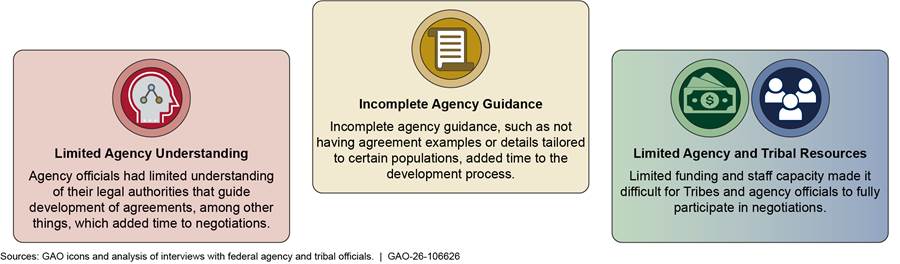

Three Factors Impeded Agreement Development, and Agencies Have Not Assessed Their Associated Funding and Staff Capacity

Federal agency and tribal officials said that agency staff’s limited understanding of the agency’s legal authorities and other core concepts, incomplete guidance, and limited agency and tribal resources impeded the development of shared decision-making agreements (see fig. 9). Conversely, in some instances where these factors were not present—such as where staff had a better understanding of core concepts—agency and tribal officials said it was easier to develop shared decision-making agreements. Agencies have not assessed their funding and staff capacity to develop shared decision-making agreements in light of these impediments and significant changes to agency budgets and staffing levels that were proposed or began taking effect in 2025.

Figure 9: Factors That Federal and Tribal Officials Said Impeded Shared Decision-Making Agreement Development

Limited Understanding of Legal Authorities and Core Concepts Underlying Tribal Partnerships

Federal agency, tribal, and Office of Native Hawaiian Affairs officials said that some staff within each of the federal agencies had not acquired a sufficient depth of understanding of agency legal authorities or the core concepts that underlie partnering with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities. They said this made it difficult to develop some shared decision-making agreements.

Understanding agency legal authorities. Not all agency field office staff who develop agreements understood their legal authorities to enter into agreements with Tribes, according to agency and tribal officials we interviewed. Field staff were not always clear on what they were authorized to have in the agreements, including how to determine which activities were inherently federal functions, and this lengthened negotiating time frames in some cases.[66] For example, Chippewa National Forest officials said that, as they were developing their agreement with the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, they had to regularly check with their attorneys regarding the activities they were authorized to include in the agreement, which added time to the process. Also, a tribal official who developed a self-governance agreement with FWS said that the Tribe spent a significant amount of time researching and then educating FWS officials on how to develop this type of agreement and the kinds of activities that Tribes are authorized to conduct, which extended the length of the negotiations.

Departmental leadership has taken some actions to help staff understand agency legal authorities. For example, to help implement the JSO, Agriculture and Interior issued reports in 2022 identifying the relevant legal authorities that can be used to develop agreements.[67] However, agency officials we interviewed said they were not aware of these reports, or the reports did not include details of how to apply the authorities they discussed. Also, NOAA finalized its report in December 2024, so field staff did not have this direction until 2 years after Commerce signed the JSO.[68]

Agencies have provided some direction about how to define activities that only federal employees can perform. For example, Interior officials have instructed their staff to consult with Interior’s Solicitors Office to determine which activities are inherently federal functions and cannot be included in self-governance agreements.[69] However, consulting with attorneys on every individual agreement has slowed down the development of some agreements. Interior has not created a standard or suggested list of inherently federal functions to guide land management agencies because the Solicitors Office has determined that these functions must be defined on a case-by-case basis.[70] The Forest Service has taken a similar approach and encouraged staff to contact their local Office of General Counsel with any questions about inherently governmental functions.

Understanding core concepts that underlie partnering with Tribes. Agency officials have at times demonstrated a limited understanding of the core concepts that underlie partnering with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities, which added more difficultly to the development of some agreements, according to agency, tribal, and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials we interviewed. Examples of these core concepts include:

· Trust and treaty responsibilities. Federal agencies have a general trust responsibility to Tribes and must respect and honor any relevant treaty rights. Forest Service officials said that a lack of education and understanding of tribal relations, including the trust responsibility and treaty rights, affects co-stewardship throughout the National Forest system, from field, regional, and national leadership to staff tasked with executing agreements.

· Tribes’ political relationship with the U.S. Tribal officials observed that agency staff may not understand Tribes’ political status and relationship to the U.S. and how it differs from other entities that are not tribal governments, such as Alaska Native Corporations.[71] In some cases, agency officials have not included Tribes in agreements to manage public lands and instead included other entities. For example, officials from Tribes in Alaska we interviewed said they were frustrated when the Forest Service developed an agreement with an Alaska Native Corporation to co-steward parts of a national forest rather than the local Tribe. Forest Service officials said the agency chose this approach since the Alaska Native Corporation had the capacity to complete the technical aspects of the agreement and was eligible to enter into the agreement.[72] A tribal official noted that Forest Service officials should understand the agency’s government-to-government relationship is with Tribes and therefore agency officials should first discuss potential agreements with Tribes.

|

Example of Information Available to Help Build Understanding of Core Concepts The Office of Hawaiian Affairs, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Native Hawaiian community, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service developed a document titled Mai Ka Pō Mai to help guide decisions regarding how to integrate Native Hawaiian culture into the collaborative management of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. The publicly available document includes information on Native Hawaiian knowledge systems, values, and practices, among other things. See https://www.oha.org/wp-content/uploads/MaiKaPoMai_FINAL-web.pdf. Source: Office of Hawaiian Affairs. | GAO-26-106626 |

· Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge. Tribal and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials we interviewed explained that agency staff did not always understand Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge or the value of incorporating it into the decision-making process.[73] Agencies are used to managing these resources according to western science, according to agency and tribal officials. For example, a FWS official said agency staff did not initially understand the tribal approach to managing fish within a national wildlife refuge in Alaska. This approach was based on the Tribes’ experiences subsistence fishing along a river that is part of the refuge. Conveying tribal approaches to fish management to FWS officials added time to the development of an agreement, according to a FWS official.

The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe and Office of Hawaiian Affairs, in partnership with others, have developed and disseminated documents that discuss some of these concepts within the context of their Tribe or community. These documents can assist agency officials’ understanding of the core concepts that are important to the Tribe and Native Hawaiian communities.

The agencies have each taken some steps to ensure staff understand these core concepts. For example, Forest Service and Interior officials said departments and agencies have provided staff with training on ways the agencies should carry out the government’s trust relationship with Tribes and other topics related to Indigenous cultures. In addition, Interior officials said they provided trainings in 2024 for upper management within BLM, FWS, and NPS. The Forest Service and NOAA also sent some staff to participate in these Interior-sponsored trainings. However, some agencies, such as NOAA, have not been able to train all their staff who develop agreements on these core concepts because officials said they have limited resources. Other agencies, such as NPS, do not require their relevant staff to attend all training the agency offers on these core concepts.

Incomplete Agency Guidance

While agencies have developed guidance, including orders and instructions, related to implementing the JSO and developing shared decision-making agreements, agency and tribal officials cited instances where guidance was incomplete and impeded agreement development. As noted earlier, the JSO states that the departments will evaluate and update departmental manuals, handbooks, or other guidance documents for consistency with this order. Agencies developed two types of implementation guidance: (1) legal, written by the agencies’ counsel based on reviews of certain treaty responsibilities and authorities that can support co-stewardship and tribal stewardship; and (2) department- or agency-specific, which outlines steps staff need to take to develop co-stewardship agreements with Tribes. Table 1 shows the types of guidance that, as of August 2025, Agriculture, Commerce, Interior, and some of their agencies developed specifically to assist the implementation of the JSO.

Table 1: Types of Guidance that Departments and Their Agencies Developed Specifically to Implement Joint Secretarial Order 3403, as of August 2025

|

|

Types of guidance developed |

|

|

Department and agency |

Legala |

Department- or Agency- specificb |

|

Agriculture |

●c |

● |

|

Forest Service |

○d |

● |

|

Commerce |

○ |

○ |

|

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) |

● |

○ |

|

NOAA/National Marine Fisheries Service |

○ |

○ |

|

NOAA/Office of National Marine Sanctuaries |

○ |

○ |

|

Interior |

● |

● |

|

Bureau of Land Management |

○ |

● |

|

Fish and Wildlife Service |

○ |

● |

|

National Park Service |

○ |

● |

Legend:

● =

Yes

○ = No

Source: GAO analysis of department and agency guidance. | GAO‑26‑106626

Notes: We did not include guidance that was indirectly related, such as tribal consultation and incorporating Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge guidance. Joint Secretarial Order 3403 says the departments will evaluate and update departmental manuals, handbooks, or other guidance documents for consistency with this Order.

aThese reports are written by the agencies’ legal counsel and include reviews of current land, water, and wildlife treaty responsibilities and authorities that can support co-stewardship and tribal stewardship, as directed by Joint Secretarial Order 3403.

bThis guidance includes direction from the departments or agencies that outlines steps staff need to take to develop co-stewardship agreements with Tribes.

cThis guidance had been issued and posted online, but as of January 2026 it was no longer available. A Forest Service official said they were updating guidance to align with presidential priorities.

dAgriculture’s guidance discusses relevant authorities for Forest Service and other agencies within Agriculture. However, as of December 2025, Forest Service had not developed its own guidance that instructs field office staff how to implement Agriculture’s legal guidance.

Agency officials said the existing guidance was incomplete in the following ways, which posed challenges for developing some agreements:

No example agreements provided. Agency officials we interviewed said they found it difficult to negotiate agreements without having an example to use as a model or template. FWS and Forest Service officials we interviewed said they have not been sure about what should be included in agreements, and Forest Service field office staff said examples would help provide more clarity.

Insufficient detail. Agency field office staff we interviewed said their agencies’ guidance was too high level for them to understand how to develop agreements. A FWS official said it would be helpful if guidance more specifically delineated how to implement the JSO’s priorities.[74] One NOAA official said not having detailed guidance to lead their actions means that they spend time trying to understand how to implement the JSO and incorporate Indigenous knowledge.

Furthermore, agency officials we interviewed said agreement development guidance was not tailored to specific populations or regions, such as Hawaii. For example, none of the agencies had developed a specific Native Hawaiian community relations guide for use in agreement development, although they administer lands or waters in Hawaii or have staff who work on natural resource issues there. FWS and NPS officials said Interior finalized departmental guidance on Native Hawaiian consultation procedures in January 2025, and as of June 2025 agency officials said they plan to incorporate this guidance. However, this guidance is not specific to agreement development. A NOAA official in Hawaii said there is an existing agency document that can be used for co-stewarding marine sanctuaries with Native Hawaiian communities and tribal governments. However, it does not describe cultural considerations, including values and beliefs, for working specifically with Native Hawaiian communities.[75]

Definitions for key terms are unclear. Tribal and agency field officials said that definitions of key terms are not always clear, which impeded agreement development in some instances. For example, tribal officials said they do not fully understand the Forest Service’s guidance regarding co-stewardship because it lacks a specific definition of that term.[76] Further, tribal officials said they do not always agree with the agencies’ definitions. This has made it difficult to communicate their priorities to agencies. For example, a tribal official said that their Tribe has a different definition of “cultural resources” than BLM and the Forest Service. To the Tribe, this term includes activities like ceremonial hunting and medicinal plant use. BLM’s definition of cultural resources, which is based on Interior’s, includes generic language and does not mention either of these activities. The Forest Service’s definition also does not specifically mention these activities and notes that cultural resources are objects or locations of human activity.[77]

Limited Agency and Tribal Resources

We found that limited agency and tribal resources—specifically funding and staff—impeded the development of some shared decision-making agreements.[78] FWS, NPS, and Forest Service officials said their agencies have not provided funding to Tribes to specifically support their participation in agreement development. A tribal official in Alaska said that doing so would help agreement development.

Limited funding. Agency and tribal officials said that limited funding to support their efforts impeded developing agreements. Developing agreements involves various expenses over a long period of time, such as travel-related expenses—fuel, lodging, food, meeting space—for in-person meetings and site visits essential to building relationships. More specifically, they said funding was limited in the following ways:

· Agency funding. Agency officials we interviewed either did not know of or have specific funding mechanisms to support agency officials’ participation in developing agreements. For example, BLM officials said funding has come from its regular appropriations and a FWS official said the agency does not have special accounts or line items specifically to support agreement development. Therefore, funding spent on agreement development can take away funding from the agencies’ other responsibilities.

· Tribal funding. Tribal and Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials said they also have limited funding for agreement development. For example, Office of Hawaiian Affairs officials said their limited funding made it difficult for them to fully participate in negotiating the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument agreement.[79]

Insufficient staffing. Agency and tribal officials said that limited staffing also impeded their capacity to develop agreements.

· Agency staff. Agency officials said that they did not have enough staff, or staff with the right expertise, which limited agreement development. For example, some NOAA officials said the agency did not have enough attorneys and natural and cultural resource coordinators to effectively communicate with Tribes or Native Hawaiian communities to develop agreements.

· Tribal staff. Tribal officials said they also did not have sufficient staff to pursue agreements. They noted that tribal representatives are often greatly outnumbered by other entities at meetings, which can make it difficult for Indigenous perspectives to be communicated and incorporated. For example, during initial meetings to discuss establishing the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument, Tribes had about four representatives out of about 40 attendees, according to tribal officials. In addition, these officials said tribal representatives have multiple responsibilities and only a portion of their time to spend on developing agreements. This can be especially difficult when the Tribe needs to spend its own limited resources to support staff participation in negotiations.

Agencies Have Not Assessed Funding and Staff Capacity

Agencies’ ability to develop agreements and address the impediments we identified may be further affected by decreases in the agencies’ funding and staffing levels that were proposed or began taking effect in early 2025. Examples of decreases included the following:

· Proposed funding reductions. In May 2025, the President’s budget request for fiscal year 2026 proposed cuts to Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior operations. For example, within Interior, it proposed a reduction of about 76 percent for BLM’s wildlife habitat management and 75 percent for national monuments and national conservation areas management. These proposed reductions could include funding used for agreement implementation, which tribal, BLM, and Forest Service officials said is an important component to consider when developing agreements.

· Reductions in staff. In February 2025, the President issued Executive Order 14210, which directed agency heads to prepare to initiate large-scale reductions in staff.[80] Agencies responded to this order in part by offering employees deferred resignations. According to BLM officials and the agency’s website, 820 staff out of about 10,000 had taken either a deferred resignation or voluntary early separation offer as of summer 2025. About 5,000 Forest Service staff out of 35,000 had taken a deferred resignation or voluntary early separation offer as of summer 2025. Reductions at these agencies include key staff who had established relationships with Tribes and expertise regarding ways to develop shared decision-making agreements.[81]

These reductions present additional opportunities for and advantages to partnering with Tribes to meet agencies’ missions, according to a Forest Service official.[82] For example, a Forest Service District Ranger said that because of the staff loss at a national recreation area in southeast Alaska, tribal cultural ambassadors are now primarily responsible for keeping the visitor center open. The Interior Secretary said in a May 2025 Senate hearing that the department is committed to continue working with Tribes.[83]

However, Tribes have expressed their concern over the cuts to agencies. For example, in June 2025, a coalition of tribal organizations sent letters to the Secretaries of Commerce and the Interior expressing their concerns with how staffing cuts will impede the departments’ abilities to uphold their trust and treaty responsibilities. In the letter to Interior, the tribal coalition also noted that the decrease in Interior’s workforce has already resulted in the abrupt ending of long-term relationships between Tribes and agency officials and delayed agency responses to Tribes.

As of September 2025, further funding and staff changes were underway, and the effect of these reductions was unclear, particularly since agencies have not assessed their capacity to develop agreements since the changes started earlier in the year. NPS and Forest Service officials said they are waiting until the current administration completes these changes before they conduct this assessment. BLM and NOAA officials did not say if they have plans to conduct this assessment, and FWS officials said they do not have plans to do so because of their limited capacity. Our report on strategic workforce planning stated that taking the following steps can help agencies ensure they meet their mission and programmatic goals. Agencies should:

· determine the critical skills, knowledge, and competencies that will be needed to achieve current and future programmatic results and identify any workforce gaps; and

· develop strategies that are tailored to address the identified gaps in number, deployment, and alignment of human capital, and the necessary critical skills, knowledge, and competencies.[84]

With limited resources, assessing agency capacity is important. By assessing staffing capacity related to developing shared decision-making agreements and identifying any skills and knowledge gaps, such as those we identified in our review, agencies will better understand how to allocate their limited resources and make strategic use of partnerships with Tribes. By addressing any skill and knowledge gaps, including through additional training and updating existing guidance, agencies will be better positioned to build trust and relationships with Tribes through informed and strategic collaboration.

Conclusions

Tribes have deep connections to and knowledge about lands and waters that are now federally managed. Shared decision-making provides an opportunity to substantively involve Tribes in managing public lands and waters, to the mutual benefit of federal agencies and Tribes. Agriculture, Commerce, and Interior and their component agencies have taken important steps to pursue shared decision-making agreements with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities, but additional actions would strengthen agreements.

Amending the TFPA provisions that preclude some Tribes and Alaska Native Corporations from participating—while also allowing for agreements on national forest lands with special significance to Tribes—would enable more Tribes to access shared decision-making with the Forest Service. It would allow for increased tribal input regarding effective management and stewardship for land restoration and risk-reduction projects and activities under the TFPA. In addition, authorizing a mechanism for the Forest Service and NOAA to enter into self-governance type agreements with Tribes to share decision-making responsibility to the extent legally permissible would enable eligible Tribes to enter into more shared decision-making agreements. Such a mechanism could include Tribes assuming the administration of certain programs with these agencies like they can with BLM, FWS, and NPS.

By updating their existing policies to include a discussion of the 11 features we identified as strengthening agreements and encouraging their adoption into future agreements whenever applicable and to the extent legally permissible, the departments could better ensure that Tribes have substantive input into the management of public lands and waters. The 11 features could serve as a common starting point for agency and tribal officials’ negotiations and create stronger agreements. In addition, incorporating the features into policies would also help safeguard against the loss of institutional knowledge when staff responsible for developing agreements depart the agencies.

Finally, as the agencies continue to pursue shared decision-making agreements with limited resources, it is important that agencies assess their workforce capacity related to developing shared decision-making agreements so they can better understand how to allocate those resources and develop partnerships with Tribes. By addressing skill and knowledge gaps, such as those we identified in our review, including through additional training and updating existing guidance, agencies will be better positioned to build trust and relationships with Tribes through informed and strategic collaboration.

Matters for Congressional Consideration

We are recommending the following three matters for congressional consideration:

If Congress supports the increased use of TFPA agreements, Congress should consider (1) amending the provisions of the Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004 that preclude some Tribes and Alaska Native Corporations from entering into TFPA agreements with the Forest Service, and (2) authorizing TFPA agreements for national forest lands with a tribal nexus, such as those that have historical, geographic, and cultural significance to Tribes. (Matter for Consideration 1)

Congress should consider authorizing a mechanism for the Forest Service to enter self-governance type agreements with Tribes that enable them to share decision-making responsibility over the administration of programs for national forest lands and waters, including natural and cultural resources, to the extent legally permissible. (Matter for Consideration 2)

Congress should consider authorizing a mechanism for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to enter self-governance type agreements with Tribes that enable them to share decision-making responsibility over the administration of programs for national marine sanctuaries, to the extent legally permissible. (Matter for Consideration 3)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of eight recommendations, including two to Agriculture, two to Commerce, and four to Interior:

The Secretary of Agriculture should update the department’s existing policies to include a discussion of the 11 features GAO identified as strengthening shared decision-making agreements to encourage their adoption in the Forest Service’s shared decision-making agreements with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities, as applicable. (Recommendation 1)

The Chief of the Forest Service should assess staff capacity related to developing shared decision-making agreements with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities, and address any skills and knowledge gaps, including through additional training and updating existing guidance. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Commerce should update the department’s existing policies to include a discussion of the 11 features GAO identified as strengthening shared decision-making agreements to encourage their adoption in NOAA’s shared decision-making agreements with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities, as applicable. (Recommendation 3)