WEAPON SYSTEMS TESTING

DOD Needs to Update Policies to Better Support Modernization Efforts

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Shelby S. Oakley at oakleys@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) identified test and evaluation modernization as a crucial part of its effort to get capabilities to warfighters faster. DOD organizations, including the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the military departments, have undertaken modernization planning efforts with varying areas of focus and levels of detail. Nonetheless, these plans share themes, including the use of digital engineering tools and highly skilled workforces.

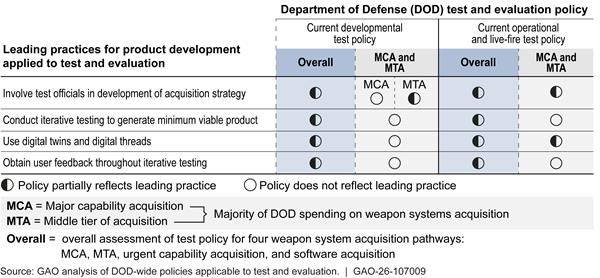

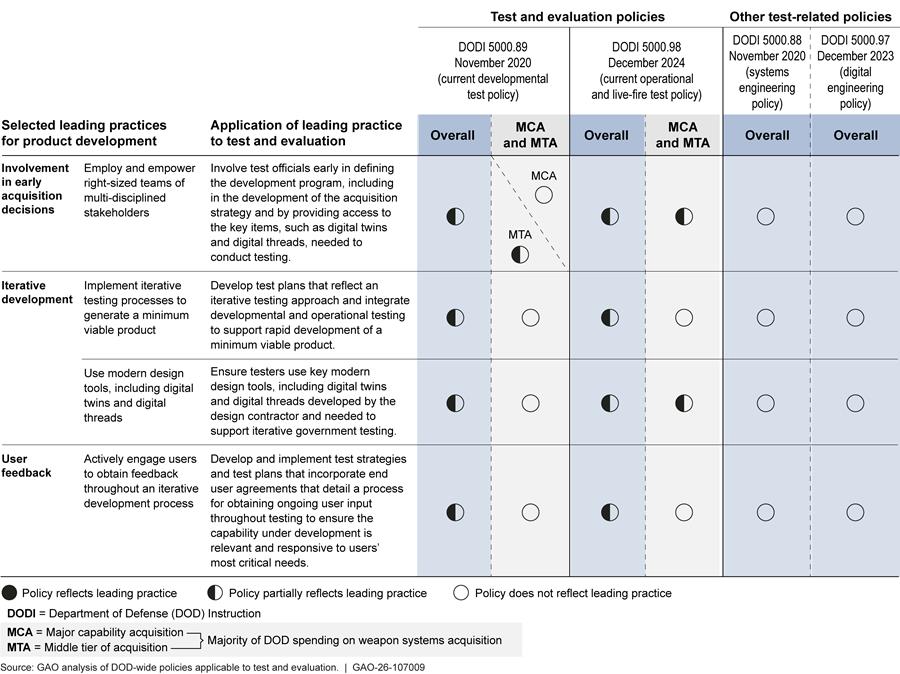

GAO’s analysis of DOD-wide test and evaluation policies found they were not fully consistent with selected leading practices for product development as applied to test and evaluation: involve testers early, conduct iterative testing, use digital twins and threads, and obtain user feedback iteratively. These policies contained some tenets of the leading practices, particularly for the software acquisition and urgent capability acquisition pathways. However, these leading practices were largely not reflected in the policies for programs in the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways, which account for the majority of DOD spending on weapon systems acquisition.

Further, GAO found that DOD’s digital engineering policy and the test and evaluation section of DOD’s systems engineering policy do not describe specific processes to ensure application of leading practices to testing.

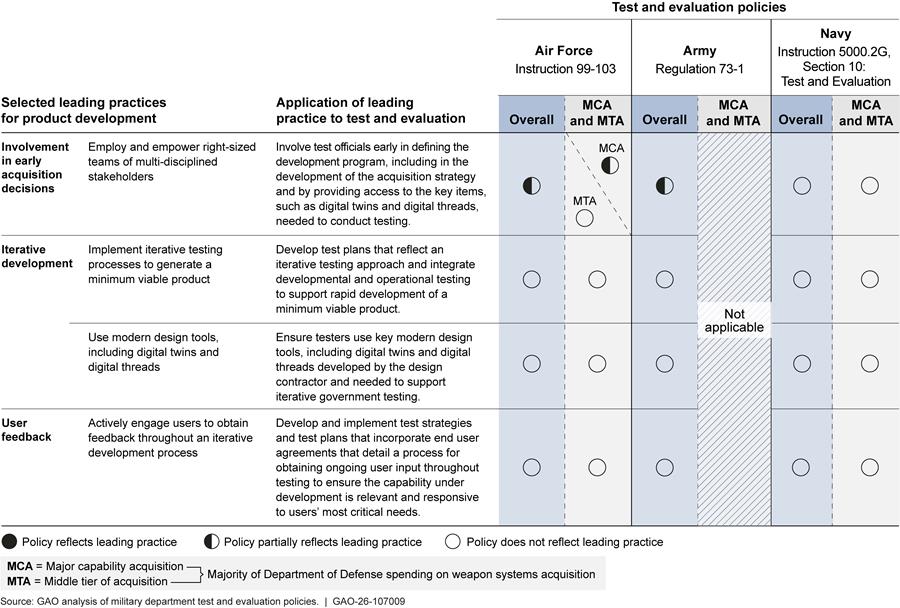

GAO also found that military department-level test and evaluation policies generally did not reflect the leading practices beyond the level found in DOD-wide policies. GAO similarly found that these leading practices were not reflected in key program documents, like acquisition strategies and test strategies, for selected weapon systems acquisition programs it reviewed.

DOD has a unique opportunity to not only retool its existing test and evaluation enterprise, but to redefine the role that enterprise can play in enabling faster delivery of relevant capabilities to warfighters. Fully incorporating leading practices into policies relevant to weapon system test and evaluation could help pivot the test enterprise’s current reactive role to a proactive one, informing and aiding defense acquisition efforts.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD has yet to realize its goal to rapidly develop weapon systems to get capabilities to the warfighter when needed. DOD acquisition programs have identified challenges discovered during test and evaluation as contributing to delays in development.

A House committee report includes a provision for GAO to assess how DOD is modernizing weapon system test and evaluation. GAO’s report (1) describes DOD’s plans to modernize test and evaluation to deliver capabilities faster to the warfighter, and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD-wide and military department policies for test and evaluation reflect selected GAO leading practices for product development.

To do this work, GAO assessed DOD test and evaluation modernization plans and policies and weapon system acquisition documentation. GAO visited three military department test organizations to observe tools in practice. GAO also interviewed DOD and military department officials from test organizations and other entities.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 13 recommendations, including that the Secretary of Defense and the Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy each should revise weapon system test and evaluation policies and other related policies to reflect selected leading practices for product development. Specifically, revisions should require involvement of testers in acquisition strategies; iterative approaches to testing, including use of digital twins and threads; and ongoing end user input. DOD concurred with seven recommendations, partially concurred with five recommendations, and did not concur with one recommendation. GAO continues to believe all 13 of its recommendations are valid, as discussed in this report.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AFOTEC |

Air Force Operational Test Center |

|

AFTC |

Air Force Test Center |

|

ATEC |

Army Test and Evaluation Command |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DODI |

Department of Defense Instruction |

|

DOT&E |

Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation |

|

DSB |

Defense Science Board |

|

F-22 SeE |

F-22 Sensor Enhancements |

|

FLRAA |

Future Long Range Assault Aircraft |

|

MCA |

major capability acquisition |

|

MTA |

middle tier of acquisition |

|

OPTEVFOR |

Operational Test and Evaluation Force |

|

OSD |

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

|

OUSD(A&S) |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment |

|

OUSD(R&E) |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 11, 2025

Congressional Committees

For more than 20 years, we have reported annually on the Department of Defense’s (DOD) most expensive weapon system acquisition programs, which often cost significantly more than planned, fall years behind schedule, and deliver less capability in the end than initially promised. At the same time, changes in the global threat environment and leaps in technology have changed the nature of the capabilities that DOD seeks to acquire. Weapon systems are increasingly cyber-physical—complex networks of hardware and software—with software driving programs more than ever before. Our recent work on leading practices for product development identified that delivering these complex systems with speed requires new, iterative approaches for development, including test and evaluation.[1]

Still, many weapon system acquisition programs continue to use a slow, linear approach to development and fall short of delivering relevant capabilities quickly and at scale. In June 2025, we found that DOD’s expected time frame to deliver initial capabilities for 79 of its major defense acquisition programs averaged about 12 years.[2] This average was longer than the average time frame of 10 years we identified for 82 programs in May 2019—less than 1 year before DOD revamped its acquisition policy to emphasize speed.[3] In part due to these longstanding issues, DOD weapon systems acquisition has been on our High-Risk List for 35 years.[4]

Weapon system acquisition programs frequently cite challenges discovered during test and evaluation as a cause for why they cannot deliver capabilities faster. As our prior work has found though, test and evaluation of new capabilities is often just the “canary in the coal mine” providing indication on whether a program is on sound footing. Specifically, weapon system acquisition programs are regularly framed by unrealistic business cases, including optimistic assumptions by the acquisition community as to how the program will perform in test and evaluation. Later, as development progresses, and test and evaluation reveals previously-unknown deficiencies, these unrealistic business cases deteriorate, resulting in cost growth, schedule delays, and capability reductions. While this traditional, reactive test and evaluation helps warfighters understand any limitations on effectiveness and suitability associated with their weapons, it does little to aid faster development and delivery of relevant capabilities that those warfighters need.

A House committee report accompanying a bill for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 contains a provision for us to assess how DOD is modernizing weapon systems test and evaluation to improve performance of defense acquisition programs. Our report (1) describes plans DOD has established to modernize test and evaluation to deliver relevant capabilities faster to warfighters, and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD-wide and military department policies for test and evaluation reflect our selected leading practices for product development.

To address our objectives, we reviewed and assessed DOD documentation, including test and evaluation policies, other related functional area policies, test and evaluation modernization plans and strategies, and weapon system acquisition documentation. We assessed the DOD-wide and military department test and evaluation policies and other related policies against our leading practices for product development. We focused our review on test and evaluation policies, rather than guidance, because these policies require courses of action while the test and evaluation guidance is generally not binding and therefore optional to follow. We conducted three site visits to the Air Force Test Center (AFTC), Army Test and Evaluation Command (ATEC), and Navy Operational Test and Evaluation Force (OPTEVFOR). We selected these sites because they are primary test agencies at each of the military departments and have centrally located workforces to meet with test officials and see test and evaluation tools in practice, such as modeling and simulation and live virtual constructive environments.

Additionally, we interviewed officials from DOD-wide and military department-level test organizations and other entities to obtain additional context and corroborate our document reviews and assessments. Those organizations and entities include the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)); Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E); the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)); Air Force Operational Test Center (AFOTEC); AFTC; ATEC; the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations; and OPTEVFOR. We also reviewed program documentation for eight selected ongoing weapon system acquisition programs to examine the military departments’ implementation of selected leading practices for product development. Appendix I presents a detailed description of the objectives, scope, and methodology for our review.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

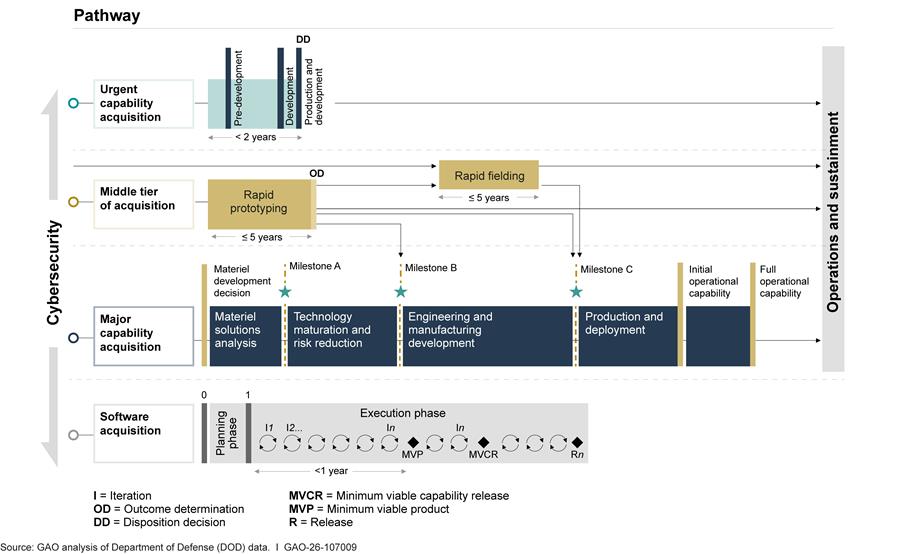

DOD’s Adaptive Acquisition Framework

In January 2020, DOD revised its acquisition policies as part of an effort to deliver more effective, suitable, survivable, sustainable, and affordable solutions to the warfighter in a timely manner. These changes were designed to allow military departments to select one or more pathways for acquiring a weapon system to best match the capability being acquired, as well as tailor and streamline certain processes. The Adaptive Acquisition Framework emphasizes several principles that include simplifying acquisition policy, tailoring acquisition approaches, and conducting data-driven analysis. The framework includes six acquisition pathways, but for the purposes of this report, we reference only the four acquisition pathways relevant to test and evaluation of weapon systems: (1) urgent capability acquisition, (2) middle tier of acquisition, (3) major capability acquisition, and (4) software acquisition. Each pathway has unique processes, reviews, documentation requirements, and metrics designed to match the characteristics and risk profile of the capability being acquired (see fig. 1).

Overview of Weapon Systems Test and Evaluation Activities and Oversight

Test and evaluation is a critical aspect of ensuring successful outcomes for weapon systems throughout their life cycles. Testing provides opportunities to collect data on system performance and identify and resolve system errors before a final fielding or acquisition decision is made. DOD conducts various types of testing activities:

· Developmental testing: conducted by contractors and the government and designed to provide feedback on a system’s design and combat capabilities before initial production or deployment.

· Operational testing: conducted by the government and designed to evaluate a system’s effectiveness and suitability to operate in realistic conditions before full-rate production or deployment. Traditionally, DOD has completed initial operational test and evaluation using an acquisition program’s low-rate initial production quantities.

· Live-fire testing: conducted by the government and involves the realistic survivability and lethality testing of systems configured for combat.

DOD test and evaluation policy also emphasizes the importance of integrated testing.[5] This type of testing is built on collaboration between developmental and operational test officials and involves the sharing of data and planning resources to facilitate communication and allow testing to build on previous efforts. Integrated testing can help identify deficiencies in a system design and help inform corrective fixes early during development and potentially reduce the scope of dedicated operational testing at the end of the acquisition process.

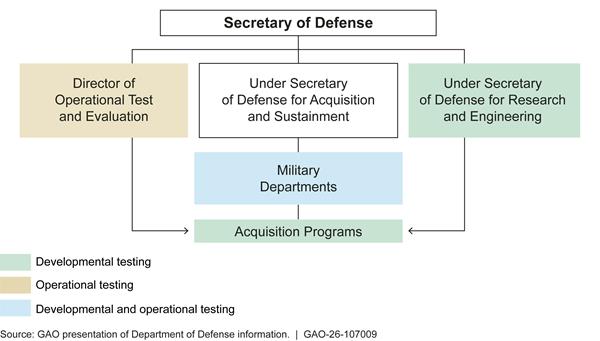

The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the military departments share oversight responsibilities for test and evaluation (see fig. 2).

OUSD(R&E) and DOT&E have the statutory authority to oversee test adequacy and establish policies for developmental testing activities and operational testing activities, respectively.[6] Beyond policy, OSD and the military departments can further define test and evaluation processes by issuing guidance. The military departments have officials in their own test and evaluation organizations and in acquisition programs who execute testing.

· DOT&E is the organization responsible for oversight of operational testing and live-fire testing across the department. The office has broad statutory authority to create policies and monitor how operational testing is conducted in the enterprise, as well as monitor and review all live-fire test activities.[7] Statute also requires DOT&E to approve plans for all operational test and evaluation of major defense acquisition programs.[8] DOD acquisition and test and evaluation policy further defines oversight responsibilities for approving operational testing in program test plans and strategies along with assessing the adequacy of a program’s test execution for weapon system programs. In a May 2025 memorandum, the Secretary of Defense directed DOT&E to eliminate any non-statutory or redundant functions and conduct a civilian reduction-in-force.[9]

· OUSD(R&E) develops governing policies relating to research and engineering, technology development, prototyping, and all developmental test activities and programs.[10] Within OUSD(R&E), the Office of Developmental Test Evaluation and Assessments oversees, in collaboration with other test and evaluation stakeholders, the development of test plans, including test activities, execution, and evaluation.

· Military departments have their own test and evaluation organizations that develop test plans and conduct developmental and operational testing, working in coordination with the acquisition programs, contractors, and warfighters, among others. Each military department assigns responsibilities for different test activities differently across its test organizations and acquisition programs.

· Acquisition programs can also have their own developmental test officials who conduct testing or review test data from the contractor.

In November 2025, the Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum to transform the defense acquisition system into the warfighting acquisition system to accelerate the fielding of urgently needed capabilities.[11] As part of the transformation, the memorandum directs the department to modernize test infrastructure, reduce test oversight, implement an adaptable test approach, and streamline test and evaluation requirements. DOD issued this memorandum several months after we provided a draft of this report to DOD for comment. As a result, we did not specifically assess how the changes called for by this memorandum will address the challenges identified in our report.

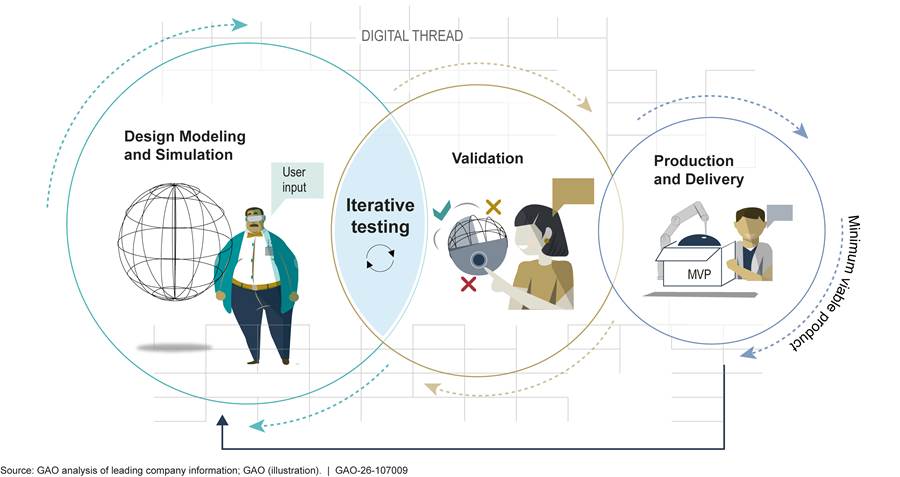

Leading Practices for Product Development

In July 2023, we reported how leading companies rely on iterative cycles to deliver innovative cyber-physical products with speed.[12] This iterative development structure—a process that includes test and evaluation activities—involves continuous cycles that include common key practices, such as identifying a minimum viable product and obtaining user feedback to ensure that capabilities are relevant and responsive to users’ needs. The iterative structure is enabled by digital engineering, including the use of digital twins or digital threads.[13]

Activities in these iterative cycles often overlap as the design undergoes continuous user engagement and testing. We found that as the cycles proceed, leading companies’ product teams refine the design to achieve a minimum viable product—one with the initial set of capabilities needed for customers to recognize value suitable to field and can be followed by successive iterations. These companies use modern design and manufacturing tools and processes to produce and deliver the product in time to meet their customers’ needs. Figure 3 depicts key elements of this approach.

Figure 3: Leading Companies Progress Through Iterative Design, Validation, and Production Cycles to Develop a Minimum Viable Product

Over the past few years, we have recommended that DOD and the military departments update their pathway policies to incorporate our leading practices for product development.[14] DOD is updating its Adaptive Acquisition Framework policies, but one recently updated policy and the draft we reviewed of another policy do not fully implement leading practices to achieve positive outcomes. Further, although DOD’s military departments have issued policies in alignment with DOD’s goals and the Adaptive Acquisition Framework, they do not consistently reflect leading practices.[15]

Table 1 details how leading practices for product development can be applied to test and evaluation to support rapid development of weapon systems.

Table 1: Relevant Leading Practices for Product Development Applied to Department of Defense (DOD) Test and Evaluation

|

Leading practices |

Application of leading practice to test and evaluation |

|

|

Involvement in early acquisition decisions |

Employ and empower right-sized teams of multi-disciplined stakeholders |

Involve test officials early in defining the development program, including in the development of the acquisition strategy and by providing access to the key items, such as digital twins and digital threads, needed to conduct testing. |

|

Iterative development |

Implement iterative testing processes to generate a minimum viable product |

Develop test plans that reflect an iterative testing approach and integrate developmental and operational testing to support rapid development of a minimum viable product. |

|

Use modern design tools, including digital twins and digital threads |

Ensure testers use key modern design tools, including digital twins and digital threads developed by the design contractor and needed to support iterative government testing. |

|

|

User feedback |

Actively engage users to obtain feedback throughout an iterative development process |

Develop and implement test strategies and test plans that incorporate end user agreements that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user input throughout testing to ensure the capability under development is relevant and responsive to users’ most critical needs. |

Source: GAO analysis of leading practices on product development applied to DOD test and evaluation processes. | GAO‑26‑107009

Plans for Modernizing Test and Evaluation Vary Across DOD

DOD has identified test and evaluation modernization as a crucial part of its larger effort to deliver new capabilities with speed. Because test and evaluation responsibilities are divided among different organizations within DOD—including at the Office of the Secretary of Defense and military department levels—these planning efforts have varied in terms of their areas of focus and their level of detail, among other differences. Even so, multiple test organizations identified several common themes that were significant to their plans for modernizing test and evaluation, including increased use of digital twins and digital tools and highly skilled test and evaluation workforces.

DOD and Military Departments Describe Modernization Efforts for Test and Evaluation in Various Plans

DOD-wide and military department-level organizations describe their plans for modernizing test and evaluation in various ways, such as strategic plans, task force briefings, and other documents. These plans vary in their focus, the level of detail and number of action items presented. For example, DOT&E’s Strategy Implementation Plan and its Science and Technology Strategic Plan outline strategic goals and objectives for modernizing test and evaluation. Table 2 describes selected DOD-wide and military department plans for modernizing test and evaluation that we reviewed.

|

Plan |

Organization |

Description |

|

DOD-wide plans |

|

|

|

Test and Evaluation, August 2024 |

Defense Science Board (DSB) |

A DOD-wide report tasked by the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, in response to a congressional directive in statute to evaluate DOD’s test and evaluation activities and explore opportunities to increase test and evaluation speed and efficiency. The report provides several findings and recommendations calling for a strategic shift in DOD acquisitions and identified key factors related to test and evaluation for achieving this goal. |

|

Digital Engineering Capability to Automate Testing and Evaluation Final Report, May 2024 |

DSB |

Final report from the congressionally directed DSB Task Force on Digital Engineering Capability to Automate Testing and Evaluation. The task force found that proper application of digital engineering can improve cost, schedule, and performance of complex projects and programs. They recommended, among other things, that DOD-wide organizations and the military services invest in digital engineering infrastructure and workforce and accelerate the use of digital engineering in testing. |

|

Director, Operational Test & Evaluation (DOT&E) Strategy Implementation Plan, April 2023 |

DOT&E |

A DOD-wide plan that outlines five strategic pillars: test the way we fight; accelerate the delivery of weapons that work; improve the survivability of DOD in a contested environment; pioneer test and evaluation of weapon systems built to change over time; and foster an agile and enduring test and evaluation enterprise workforce. These pillars are intended to produce end states such as testing under operational environment conditions, using digital tools and data to accelerate weapons delivery, and having a highly skilled test and evaluation workforce. |

|

DOT&E Science and Technology Strategic Plan, January 2021 |

DOT&E |

A DOD-wide plan that documents DOT&E’s framework for addressing key science and technology priorities including test and evaluation for software and cybersecurity, next-generation test and evaluation capabilities, the integrated test and evaluation life cycle, digital transformation, and workforce expertise. |

|

Test and Evaluation as a Continuum, March 2023 |

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) |

A white paper by a test official within OUSD(R&E) that calls for a new integrated framework of test and evaluation activities using capability and outcome-focused testing, an agile and scalable evaluation framework, and enhanced test design. This framework contrasts with the current serial nature of test activities. An OUSD(R&E) official told us they are developing a communications strategy to socialize this framework with the rest of DOD’s test and evaluation community and are identifying programs to serve as pathfinders of these practices. This framework is not included in policy nor adopted in practice across DOD. |

|

Military department-level plans |

||

|

Fiscal Year 2024 Army Test and Evaluation Command (ATEC) Next: Campaign Plan for 2024-2029 |

ATEC |

A plan for the Army that sets multi-year objectives and identifies specific fiscal year 2024 tasks related to modernizing the workforce, investing in test and evaluation capabilities, and leveraging digital technologies, among other things. |

|

U.S. ATEC Modernization Task Force Summary, March 2024 |

ATEC |

Briefing slides that summarize focus areas—including workforce transformation, business processes, and test and evaluation capabilities. |

|

Air Force Operational Test and Evaluation Center (AFOTEC) Strategic Vision 2030, February 2024 |

AFOTEC |

Briefing slides that summarize AFOTEC’s strategic vision and progress made toward identified end states. Key issue areas include talent management, policies, tools, and integrated test capabilities. |

|

Navy Operational Test and Evaluation Force (OPTEVFOR) Strategic Roadmap, January 2022 |

OPTEVFOR |

A roadmap to define strategic priorities and measure progress of each initiative, based on the Chief of Naval Operations’ Navigation Plan and its Implementation Framework. Focus areas include implementing adaptive relevant testing, external engagement, improving cyber testing, and command operations. |

Source: GAO summary of Department of Defense (DOD) and military department information. | GAO‑26‑107009

Note: GAO also reviewed DOD-wide and military department plans, such as strategies for implementing digital engineering, that were not directly about modernizing test and evaluation but could affect test practices.

In response to a congressional directive in statute, OUSD(R&E) directed the Defense Science Board (DSB)—a DOD committee that provides independent advice and recommendations on matters supporting scientific and technical enterprise—to report on how DOD can improve the speed and efficiency of test and evaluation. Congress also directed DSB to assess DOD’s progress in implementing a digital engineering capability to automate testing and evaluation.[16] The reports describe a DOD-level end-state of modernized test and evaluation. DOD is in the process of responding to DSB’s recommendations. OUSD(R&E)’s Office of Developmental Test Evaluation & Assessment plans to address relevant recommendations through updated developmental test policy, which the office is currently revising. Further, a DOT&E official stated that DOT&E does not have a formal response to the digital engineering report and that the focus areas identified in the test and evaluation report reflected issues of which the test community was already aware. According to the DOT&E official, that office is already implementing the recommendations from the DSB reports through its Strategy Implementation Plan.

Additionally, some of these plans listed in table 2 outlined conceptual frameworks. For example, an OUSD(R&E) official described their “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” concept as a framework to move the test enterprise into a more iterative structure. The “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” concept—which is not included in policy and is not adopted in practice—is a pivot from DOD’s traditional linear testing and systems engineering approach.

Specifically, in DOD’s traditional approach, DOD begins testing a weapon system after sufficient requirements and design are set. In contrast, the “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” concept moves test and evaluation from a serial set of activities conducted largely after system design to a continuum of activities beginning once a mission need is identified. A model-based environment will enable mission engineering, systems engineering, and test and evaluation communities to work in tandem early and continually and to respond quickly to the dynamic threat environment.[17] The framework also states that in the future, the “requirements” of a particular weapon system will most likely evolve from discrete key performance parameters to one of “system behaviors” where the continuous testing process will allow more rapid evaluation against those desired system behaviors within the context of the model-based environment. Further, OUSD(R&E) expects that the missions engineering process associated with “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” will identify mission sets as well as the capabilities needed to conduct them, thereby enabling timely updates to performance requirements for the weapon system under development.

Because the modernization plans differ in how much detail they provide regarding steps the organization plans to take, we did not assess the degree to which these plans have been implemented. However, officials from DOD-wide and military department-level test organizations described various efforts taken to modernize test and evaluation in accordance with relevant plans, with implementation in various stages. For example, OUSD(R&E) is currently developing tenets for “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” while some military departments developed targets to help them measure progress toward meeting their goals.

Plans Share Several Focus Areas to Modernize Test and Evaluation

Despite the varied purpose, focus, and level of detail, we found several common themes across the modernization plans we reviewed, including but not limited to investment in test infrastructure, workforce transformation, and revisions to policy and guidance.

Investment in Test Infrastructure

Plans from each of the DOD-wide and military department test organizations, as well as the DOD Strategic Management Plan, identify the need to invest in test infrastructure.[18] Specifically, multiple plans call for infrastructure investments to increase the use of digital engineering and business tools, such as:

· Modeling and simulation and digital twins. Plans from each military department, DOT&E, and OUSD(R&E) call for expanded use of modeling and simulation and digital engineering tools. For example, DOT&E’s Strategy Implementation Plan calls for increasing the use of credible digital twins in test and evaluation. Further, the DSB report on test and evaluation recommends that programs be prepared to execute test and evaluation using digital engineering principles and to ensure they develop and deliver digital tools to enhance testing strategies.

At the military department-level, ATEC—the Army’s developmental and operational test organization—describes in its 2024-2029 Campaign Plan its goal for digital transformation that leverages a distributed test network. Currently, ATEC digitally models its vehicle test ranges, which allows it to simulate various conditions and run digital simulations to collect more data than would be possible with live testing. ATEC officials told us that some of the advantages of these digital simulations were that they could run far more iterations of a test than is possible on a physical range, including simulating changes in weather conditions that may not be present on a physical range at the time of test.

· Digital environments and distributed test networks. DOT&E’s Strategy Implementation Plan calls for developing the requirements and concept for a digital environment to integrate with live testing.

At the military department-level, AFOTEC—the Air Force’s operational test agency—calls for a digital transformation of processes and infrastructure to enable operational testing and business activities in a digital environment. Additionally, ATEC’s Modernization Task Force identified a need to connect the ATEC enterprise on a distributed test network and to perform data collection, instrumentation, analysis, and reporting in a cloud-based environment. Leveraging this network, ATEC officials conducted a test event using a mixture of live and virtual assets across the country.

· Digitized business tools. Multiple test organizations also identified improvements to business tools as an area of modernization. For example, DOT&E’s Science and Technology Plan and Navy officials we interviewed highlighted the use of a digital test plan to streamline their business processes by reducing the development time of the test plan and fully integrating digital engineering.

The DSB report on test and evaluation also identified a need to modernize test infrastructure and recommended that DOD reevaluate test infrastructure to support future needs. It also recommended that the Test Resource Management Center—a group within OUSD(R&E) that manages test and evaluation infrastructure department-wide—accelerate the development of a knowledge management system and assess emerging commercial capabilities in autonomous vehicles and sensing that could be leveraged. DSB also recommended that OUSD(R&E) explore approaches to increase the priority of test and evaluation infrastructure in military construction prioritization discussions to identify funding to meet test and evaluation needs.

DSB found, and test officials similarly stated to us, that funding structures pose a challenge to modernizing test and evaluation. The DSB report on digital engineering found that the cost of acquiring tools and applications is a barrier for some programs to use digital engineering. For example, both Air Force and Navy officials told us that investing in digital tools or other test infrastructure can be a challenge for some programs that have less funding to invest in these tools, because testers rely on programs for funding rather than having funding of their own to invest in tools. The Test Resource Management Center provides funding to develop and acquire new test capabilities and address modernization projects too large for a single military department, but such projects must satisfy multi-service requirements.

Workforce Transformation

Plans from test organizations DOD-wide and at each military department call for identifying workforce needs or for filling skills gaps that affect the organization’s ability to modernize test and evaluation through training or recruitment.

· Identifying skill gaps. The DOD Strategic Management Plan calls for annual assessments of DOD’s science and technology workforce to support critical technology development. Additionally, the DOT&E Science and Technology Strategic Plan calls for developing internal expertise and creating a pipeline of incoming workers with necessary skill sets for test and evaluation.

· Training for new technology and processes. The DSB test and evaluation report recommended that OUSD(A&S) and OUSD(R&E) develop a comprehensive approach to developing the test and evaluation workforce to enable it to adapt to rapidly advancing technologies. The report also recommended that OUSD(A&S) ensure program and test staff have been trained in the use of needed digital tools and environments. Modernization efforts require program or testing staff to make changes to existing processes to affect speed of development and testing; training prepares the workforce to execute new processes. Plans from DOT&E, OUSD(R&E), and each military department emphasize the need to ensure training opportunities to prepare the workforce for modernizing test and evaluation.

Officials at DOD-wide and military department test organizations told us that an impediment to modernization is that adherence to existing practices prevents change. For example, AFTC officials said that, historically, findings from test events were not typically shared until the test reports were signed and provided to programs. This created lag time between when issues were identified during testing and when those issues were addressed. These officials said that the cultural shift is needed to ensure that contractors and the test community are more collaborative. Some officials described actions taken by their organization to improve processes or enhance collaboration.

· Hiring flexibilities. Officials at multiple military departments told us that they have difficulty competing with the private sector in recruiting and retaining staff with necessary skill sets for digital transformation due to the differences in government pay scales and private sector compensation. As part of its fiscal year 2024 Campaign Plan, ATEC identified efforts to promote the use of incentives and direct hiring authorities to improve recruitment and stated an intent to implement programs aimed at supporting staff to improve work-life balance and workforce retention.

Policy and Guidance Revisions

Plans from DOT&E, OUSD(R&E), the Army, and the Navy call for updating policies and guidance to address the need to test new and emerging technologies or to leverage new tools that can be used in test and evaluation. DSB’s recommendations call for a strategic shift in testing and point toward the need for additional policy or guidance.

· Testing new technologies. The DOT&E Strategy Implementation Plan states that updated guidance is needed to test space systems and AI-enabled systems, and to use advanced tools to support operational test activities.

· Employing digital engineering. OUSD(R&E)’s “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” framework states that OSD and the military departments should develop and employ a common test and evaluation modeling system—including data dictionaries—and contracting guidance consistent with test and evaluation as a continuum.[19] The digital engineering strategies issued by OSD, the Army, and the Navy acknowledge digital engineering’s role in facilitating a shift from the traditional method of capability development to a more flexible approach that allows for prototyping, experimentation, and testing in a virtual environment. These strategies call for developing policy and guidance related to digital engineering.

The DSB task force on digital engineering found, among other things, that DOD lacks common standards in digitally representing environments and systems. It recommended that DOD develop common digital reference architecture and infrastructure to support the implementation of digital engineering across services and systems. Additionally, the DSB test and evaluation task force recommended that OUSD(R&E) publish best practices on the use of digital engineering and guidance on developmental testing requirements to enable efficient software development and use of digital engineering principles.

· Testing early and continuously. The DSB report on test and evaluation calls for a strategic shift in test and evaluation from the current acquisition-based framework to one that incorporates continuous development and testing. It made several recommendations aimed at this strategic shift that would likely require new policy and guidance to implement. For example, it recommended that:

· OUSD(A&S), OUSD(R&E) and DOT&E expand their view of test and evaluation activities to incorporate verification and validation activities that occur before initiation of formal acquisition programs to accelerate the transition to the formal program by avoiding repetition;

· OUSD(A&S) direct service acquisition executives—military department-level acquisition executives responsible for implementing DOD acquisition policy within their respective department—to structure new programs to incorporate testability requirements, maximize use of automation to increase testing, and develop approaches to report data that can be used to improve system performance; and

· OUSD(R&E) develop developmental testing guidance to ensure system capability to use automated developmental testing to the maximum extent possible.

Collectively, these modernization plans identified a need for DOD to issue new or revised policies and guidance to support modernized test and evaluation.

Test and Evaluation Modernization Is Constrained by Policies That Do Not Fully Reflect Leading Practices

DOD-wide policies related to test and evaluation do not fully reflect relevant leading practices for product development. For example, the policies specific to test and evaluation largely did not reflect those leading practices for the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways, which account for the majority of DOD’s spending on weapon systems acquisition. Instances where we found these leading practices take root were largely confined to the software acquisition and urgent capability acquisition pathways. Other related DOD-wide functional area policies on digital engineering and systems engineering largely did not include processes for how testers can apply these leading practices. Further, military department test and evaluation policies generally do not reflect leading practices beyond what is reflected in applicable DOD-wide policies. Correspondingly, in our review of acquisition strategies and test strategies for selected programs across the military departments, we found no evidence that these programs have operationalized relevant leading practices.

DOD-wide Policies Related to Test and Evaluation Do Not Fully Reflect Relevant Leading Practices for Product Development

DOD-wide policies related to test and evaluation do not fully reflect key tenets of our leading practices for product development.[20] The policies specific to test and evaluation generally reflect leading practices applicable to certain acquisition pathways, such as the software acquisition and urgent capability acquisition pathways.[21] In June 2025, we found that programs in two other acquisition pathways—major capability acquisition and middle-tier of acquisition—account for the largest spending on DOD’s weapon system acquisitions.[22] However, DOD-wide test and evaluation policies did not fully reflect leading practices for those acquisition pathways. Further, we found that two DOD-wide functional area policies that support test and evaluation—DOD Instruction 5000.97 on digital engineering and DOD Instruction 5000.88 on systems engineering—reflect some elements of leading practices for product development. These policies, however, do not define or describe any specific processes for ensuring their application to test and evaluation (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Key DOD-wide Policies Applicable to Weapon System Test and Evaluation Do Not Fully Reflect Selected Leading Practices

Notes: The “overall” determinations reflect GAO’s assessments of the full contents of a given policy applicable to the four weapon system acquisition pathways: major capability acquisition, middle tier of acquisition, urgent capability acquisition, and software acquisition. For the test-specific and test-related policies, GAO’s policy determinations for partially reflects indicate at least one of the following: (1) the policy language under review reflects some, but not all, parts of GAO’s selected leading practice description as it applies to test and evaluation; or (2) the policy language fully reflects GAO’s selected leading practice but only for some of the acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems in the Adaptive Acquisition Framework. For the test-specific policies, a partial determination for the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways indicates that the policy partially reflects the relevant leading practice for at least one of the pathways.

DOD Instruction 5000.98 establishes policy, assigns responsibilities, and prescribes procedures for operational test and evaluation of DOD systems and services acquired via the Defense Acquisition System or via other non-standard acquisition systems. DOD Instruction 5000.98 supersedes information regarding operational test and evaluation located in DOD Instruction 5000.89.

· Involvement in early acquisition decisions. DOD-wide test and evaluation policies state that programs should set up a test and evaluation working-level integrated product team, which we refer to as a cross-functional test team. The cross-functional test team assists in developing the test strategy and is the primary forum for collaboration between the program manager and test community. These test and evaluation policies also state the programs should set up the cross-functional test team early in the program, but the policies are not specific as to when.

Specifically, DOD Instruction 5000.89—herein referred to as the DOD-wide developmental test and evaluation policy—includes tester involvement in the development of the acquisition strategy, including the development of testing requirements, for the software acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways.[23] However, there is no similar language for the other acquisition pathways, including the major capability acquisition pathway. The policy also does not state whether testers are to have access to digital twins or digital threads, which are key items needed to conduct testing in an iterative development framework. OUSD(R&E) drafted revisions to its developmental test and evaluation policy that, if implemented, would include provisions placing greater emphasis on early tester involvement. For example, one draft provision would require the involvement of the cross-functional test team in the development of requirements and other critical acquisition documents including the acquisition strategy and the contract.

Similarly, DOD Instruction 5000.98—herein referred to as the DOD-wide operational test and evaluation policy—states that testers should be involved in the development of the acquisition strategy and the inclusion of test requirements for programs in all pathways, including the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways.[24] However, the test policy does not identify whether the testers have access to digital twins or digital threads.

DOD-wide digital engineering policy further states that programs generally should incorporate digital engineering for the capability in development, and that digital engineering must be addressed in the acquisition strategy, including how and when it will be used in the system life cycle. However, the policy does not further define a process by which testers can advocate for the access to digital twins and digital threads during development of the acquisition strategy. Similarly, the systems engineering policy does not provide that additional context.

· Iterative development. DOD-wide developmental test and evaluation policy requires programs in the software acquisition pathway to develop test strategies that detail how they plan to use iterative test processes. However, it does not require test strategies or test plans to address iterative testing for acquisition programs in other pathways, including the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways.[25] Additionally, the policy requires all DOD acquisition programs, regardless of acquisition pathway, to execute iterative developmental and operational testing for cybersecurity throughout the program’s life cycle. The policy also requires testers to consider using digital twins for some programs in the software acquisition pathway but does not require testers to use digital twins for other pathways, including major capability and middle tier of acquisition pathways. OUSD(R&E) drafted revisions to its developmental test and evaluation policy that, if implemented, would emphasize a shift away from the traditional testing approach for acquisition programs toward an iterative approach to support an agile decision-making process. For example, one draft provision would require that, in this new approach, developmental testing encompass a campaign of learning covering the entire capability life cycle, which would provide focused and relevant information to support decision-making with the goal of accelerating the fielding of capabilities. This provision, if implemented, would reflect OUSD(R&E)’s “Test and Evaluation as a Continuum” framework for modernizing test and evaluation.

Similarly, DOD-wide operational test and evaluation policy requires test plans for programs in the software acquisition pathway to use an iterative test process but does not require test strategies or test plans to address iterative testing for acquisition programs in other pathways.[26] The policy also references the use of digital engineering and digital tools such as digital twins, though it does not reference the use of digital threads.

DOD-wide digital engineering policy states that OUSD(R&E) is responsible for implementing digital engineering in the activities for developmental testing, and states that DOT&E supports the use of digital engineering in operational testing. It also states that DOD will develop a digital engineering capability that includes digital twins and threads. However, it does not describe how the test community will use those digital twins and threads in their test processes, including the development of test strategies and test plans. Similarly, the DOD-wide systems engineering policy does not expand upon those areas.

· User feedback. DOD-wide test and evaluation policies generally do not require testers to iteratively engage users to obtain feedback throughout testing to support system development. Specifically, DOD-wide developmental test and evaluation policy states that testing should generally include user feedback to support design and operational use improvements for the urgent capability acquisition pathway, and the DOD-wide operational test and evaluation policy reiterates this for the urgent capability acquisition pathway. However, there is no similar language for the other acquisition pathways, including the major capability acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways. The policies also do not specify how end user feedback is to be solicited routinely throughout iterative testing. Further, DOD-wide digital engineering and systems engineering policies do not expand on how the test community should solicit user feedback through iterative testing.

DOD acquisition policy requires programs using the software pathway to create user agreements.[27] User agreements are a commitment between the sponsor and program manager for continuous user involvement. The agreements assign decision-making authority for decisions about required capabilities, user acceptances, and readiness for operational deployment. These agreements help to ensure the user community is represented and engaged throughout development by defining responsibilities and expectations for involvement and interaction of users and developers. In July 2023, we recommended, among other things, that DOD incorporate agile principles into requirements policy and guidance for all programs using agile for software development, including a user agreement.[28] DOD partially concurred with this recommendation, and agreed to clarify requirements policy to provide guidance on using an acquisition Capability Needs Statement and user agreement for development of software that is embedded within an already validated requirements document without needing additional requirements validation. This recommendation remains open as of May 2025.

Without revising DOD-wide test and evaluation policies and related functional area policies to fully reflect the relevant leading practices for all acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems, DOD is missing opportunities to ensure that the systems under test are responsive to and relevant to warfighter needs. Such practices include obtaining early input from testers on the acquisition strategy, reflecting an iterative test approach in test strategies and test plans, and developing user agreements in test strategies and test plans to obtain user feedback.

Military Department Test and Evaluation Policies Reflect Marginal Additional Use of Leading Practices Beyond DOD-Wide Policies

Military department test and evaluation policies reflect relevant leading practices to only a limited extent beyond what is in the DOD-wide policies.[29] Further, we found no evidence in our review of program documentation that DOD has operationalized those leading practices in its test and evaluation function. Figure 5 summarizes the extent to which military department test and evaluation policies reflect our selected leading practices for product development beyond what is already reflected in DOD-wide policies.

Figure 5: Military Department Weapon System Test and Evaluation Policies Do Not Fully Reflect Selected Leading Practices Beyond the Level in DOD-Wide Policy

Notes: The “overall” determinations reflect GAO’s assessments of the full contents of a given policy applicable to the four weapon system acquisition pathways: major capability acquisition, middle tier of acquisition, urgent capability acquisition, and software acquisition. GAO assigned ratings for the military department test and evaluation policies by determining whether the policy language further reflected leading practices for product development beyond the policy established in DOD Instruction 5000.89 and DOD Instruction 5000.98. Air Force, Army, and Navy test and evaluation policies incorporate and implement DOD-wide test and evaluation policy. See figure 4 for GAO’s analysis of DOD-wide test and evaluation policy.

A partial rating indicates at least one of the following: (1) the policy language under review reflects some, but not all, parts of GAO’s selected leading practice for product development as it applies to test and evaluation; or (2) the policy language fully reflects GAO’s selected leading practice but for some, but not all, acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems in the Adaptive Acquisition Framework.

The Army issued its test and evaluation policy in June 2018, prior to the establishment of the Adaptive Acquisition Framework in 2020, and as such, does not contain any acquisition pathway specific test policy or procedures. Therefore, GAO did not evaluate the policy against specific pathways.

Air Force Test and Evaluation Policy Does Not Fully Reflect Leading Practices

Air Force test and evaluation policy partially reflects one leading practice beyond what is in DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.[30] Our assessment also found the following:

· Involvement in early acquisition decisions. The current Air Force test and evaluation policy partially reflects the leading practice—tester involvement in the development of acquisition strategies and advocating for access to digital twins and digital threads—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.[31] Specifically, the Air Force policy requires developmental testers to be involved in the development of program acquisition strategies irrespective of the selected acquisition pathway. This is an improvement over DOD-wide policies, which include developmental tester involvement for only those programs on the software acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways. Like the DOD-wide policies though, the Air Force policy does not require testers to advocate for access to digital twins and digital threads—a shortfall that is inconsistent with the leading practice.

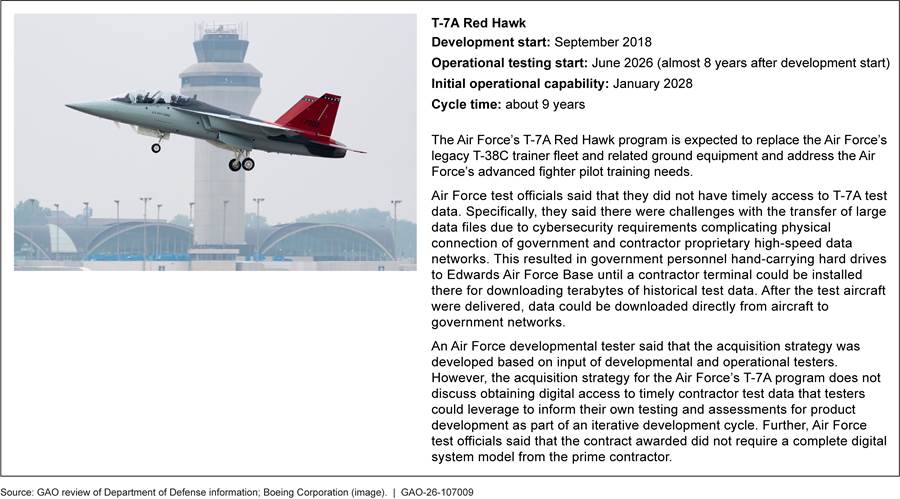

Air Force test officials are not always involved early in the acquisition process. Air Force developmental test officials said that a cross-functional test team is usually established too late in the acquisition process. Those officials added that Air Force testers rely on acquisition officials to acquire program models and data through the contract, and in some instances, it has taken an extra year of negotiations to get the data and models from the contractor. To illustrate this issue, figure 6 below provides information on tester involvement in developing the T-7A acquisition strategy.

Figure 6: T-7A Acquisition Strategy Does Not Describe Timely Access to Contractor Test Data and Digital Model

· Iterative development. Air Force test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practices—developing test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative test approach and use digital twins—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies. The Air Force drafted revisions to its test and evaluation policy that, if implemented, would include requirements for testers to evaluate digital models of systems, digital twins, and digital threads as components of the supporting infrastructure for test analysis and evaluation planning across all Adaptive Acquisition Framework pathways.

Additionally, none of the acquisition strategies and test plans associated with the three Air Force programs we reviewed considered the use of digital twins and digital threads for test and evaluation to support iterative product development.

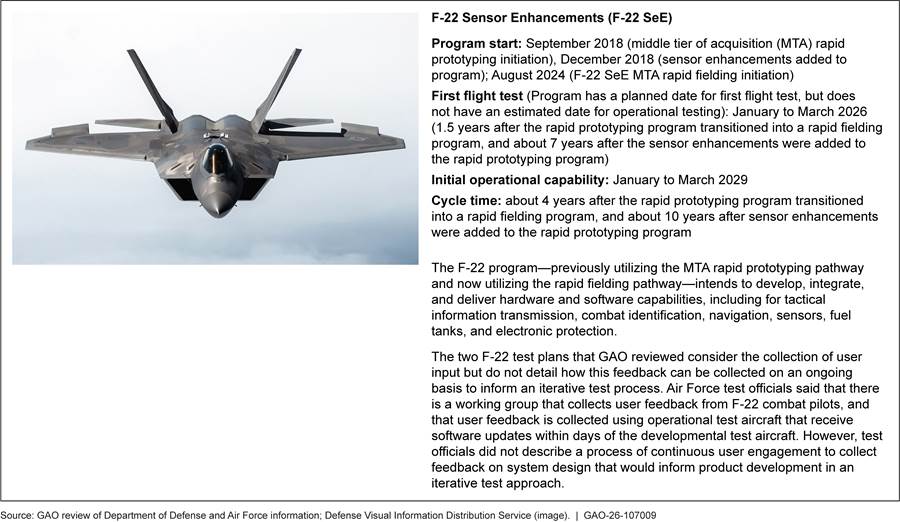

· User feedback. Air Force test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practice—developing test strategies and test plans that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user feedback—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.

For the selected Air Force programs we reviewed, the test plans did not identify how ongoing user feedback can be used to support an iterative test process. As a result, programs across pathways are not ensuring that the weapon system under test meets essential user needs. Figure 7 below provides information about the extent to which the F-22 program incorporated end user feedback into its test plans.

Figure 7: Test Plans for Air Force’s F-22 SeE Program Do Not Consider How Ongoing User Feedback Could Be Incorporated into an Iterative Test Process

Tester involvement in the development of the acquisition strategy could better enable test officials to get access to contractor test data. This would allow the test community to use leading practices for product development and conduct systems-integrated tests on a digital twin or a physical prototype connected to a digital twin to assess whether the minimum viable product meets user needs.

Without revising Air Force test and evaluation policy to fully reflect the relevant leading practices for all acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems, the Air Force is missing opportunities to ensure that testing proceeds expeditiously and that the systems under test are responsive and relevant to warfighter needs. Such practices include advocating for tester access to digital twins and digital threads as part of acquisition strategy development, reflecting an iterative test approach in test strategies and test plans, and developing user agreements in test strategies and test plans to obtain user feedback.

Army Test and Evaluation Policy Does Not Fully Reflect Leading Practices

The Army’s test and evaluation policy reflects leading practices to a limited extent beyond what is in DOD-wide test and evaluation policies. Specifically, the current policy states that testers should have early involvement in the acquisition strategy. The Army’s test and evaluation policy predates the Adaptive Acquisition Framework that established the different acquisition pathways. As such, this policy provides a common set of test and evaluation policies irrespective of the different pathways. Our assessment of the policy found the following:

· Involvement in early acquisition decisions. The Army test and evaluation policy requires tester involvement in the development of acquisition strategies for all programs—whereas the DOD-wide developmental test policy requires it only for the software acquisition and middle tier of acquisition pathways.[32] However, similar to the DOD-wide test and evaluation policy, the Army test and evaluation policy does not require testers to advocate for access to digital twins and digital threads.

Army test officials said they are not always involved early in the acquisition process, and therefore not proactively involved in getting test data requirements into the contract. Instead, Army test officials said they must work through the program manager to get access to data. Those officials added that they are working to be more involved earlier in the acquisition process, but they believe that programs are beginning to embrace testers as part of the team developing the weapon system.

· Iterative development. Army test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practices—developing test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative test approach and use digital twins and digital threads—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.

The Army drafted revisions to its test and evaluation policy that, if implemented, would include provisions referencing the use of models and data to conduct integrated testing and to support an agile approach with continuous operational testing. The draft policy also would contain provisions requiring models and data to be used to digitally represent the system in a mission context to conduct integrated test and evaluation activities, and to the largest extent possible, programs would use an accessible digital ecosystem as part of the Army’s digital engineering strategy. Army officials said they do not have an estimate for when they plan to publish the revised test policy.

The Army acquisition strategies and test plans we reviewed generally did not advocate for government access to contractor-developed digital twins and digital threads and provided limited tester access to contractor data to inform product development. Additionally, the Army test plans that we reviewed inconsistently supported implementing an iterative government testing approach. Further, none of the selected Army acquisition strategies and test plans we reviewed considered the use of digital twins and digital threads for test and evaluation to support iterative product development. Figure 8 describes how the Future Long Range Assault Aircraft program intends to use digital tools, but not in an iterative test approach.

· User feedback. Army test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practice—developing test strategies and test plans that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user feedback—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.

Without revising Army test and evaluation policy to fully reflect the leading practices for all acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems, the Army is missing opportunities to provide testing that is tailored and responsive to rapid design iterations, and to ensure that integrated testing proceeds expeditiously to get new capabilities to warfighters sooner. Such practices include obtaining early input from testers on the acquisition strategy, reflecting an iterative test approach in test strategies and test plans, and developing user agreements in test strategies and test plans to obtain user feedback.

Navy Test and Evaluation Policy Does Not Fully Reflect Leading Practices

The Navy’s test and evaluation policy does not further reflect leading practices beyond what is in DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.[33] Our assessment found the following:

· Involvement in early acquisition decisions. Navy test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practice—tester involvement in the development of acquisition strategies and advocating for access to digital twins and digital threads—beyond what is in DOD-wide test and evaluation policies for all the Adaptive Acquisition Framework pathways.

Navy operational test officials said that they are generally not involved in the development of acquisition strategies. For example, Navy operational test officials said that most programs are proactive in discussions with their office, but others delay coordinating with test officials because the program is working through technical challenges. Additionally, these test officials said that the current acquisition framework does not incentivize program managers to reach out to testers early because many programs choose to delay testing while addressing other issues.

· Iterative development. Navy test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practices—developing test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative test approach and use digital twins and digital threads—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.

The Navy test plans that we reviewed did not consistently support implementing an iterative government testing approach. Additionally, the Navy acquisition strategies and test plans we reviewed did not consider the use of digital twins and digital threads for test and evaluation to support iterative product development. Furthermore, none of the Navy test plans identified how user feedback can be used to support an iterative test process. As a result, these programs are not positioned to ensure, on an ongoing basis throughout development, that the weapon systems under test meet essential user needs. Figure 9 identifies how the Navy approached iterative development for the Ford class aircraft carrier program.

Figure 9: The Navy’s Ford Class Aircraft Carrier Program Did Not Fully Implement an Iterative Test Process

· User feedback. Navy test and evaluation policy does not reflect the leading practice—developing test strategies and test plans that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user feedback—beyond the DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.

Navy operational test officials said that user feedback is often derived from different types of operational testing. However, we found that the Navy test plans we reviewed did not identify how user feedback can be used to support an iterative test process. As a result, programs across pathways are not ensuring that the weapon system under test meets essential user needs.

Without revising Navy test and evaluation policy to fully reflecting the leading practices for all acquisition pathways directly related to weapon systems, the Navy is missing opportunities to ensure that the systems under test are responsive and relevant to warfighter needs. Such practices include obtaining early input from testers on the acquisition strategy, reflecting an iterative test approach in test strategies and test plans, and developing user agreements in test strategies and test plans to obtain user feedback

Fully Realizing Test and Evaluation Modernization Hinges on Changes to Acquisition Strategy Development Policy

Multiple organizations are responsible for ensuring the test community is involved to effectively develop weapon systems. OUSD(A&S) is responsible for issuing acquisition policies to ensure an effective partnership between the program and test community. OUSD(A&S) also has a role in ensuring that the test community is consulted early and that test official input is obtained and incorporated into the acquisition strategy. In March 2022, we recommended that OUSD(A&S) update its acquisition policies to fully implement our leading practices throughout development, including obtaining a sound business case.[34] As part of a sound business case, programs should ensure they have stakeholder—anyone with interest in the product—input early in the program. DOD concurred with our recommendations, but as of February 2025 had yet to implement them. DOD is currently revising some of its acquisition policies that may yet introduce these practices.[35]

Test officials have a vested interest in weapon system acquisitions because they ultimately assess whether the systems are deemed suitable, effective, and lethal for the warfighter. Acquisition strategies set the program manager’s plan to achieve program execution and programmatic goals across a program’s entire life cycle and provide a basis for more detailed planning. Test officials provide input into the key items—such as digital twins and digital threads, and other resources—that are needed to test weapon systems and rapidly deliver capabilities.

As discussed, DOD acquisition programs have missed opportunities to obtain and incorporate test official input into the acquisition strategy. We found that, generally, cross-functional test teams are available to support acquisition programs. However, acquisition programs are not always using cross-functional test teams to help develop the acquisition strategy. Specifically, program officials for nearly half the programs told us that they did not seek input from the test and evaluation community while developing the programs’ acquisition strategies. Further, we found that some of the acquisition programs did not form their cross-functional test teams until after the acquisition strategy was developed. As we previously discussed, the acquisition strategies for these programs generally did not include information on key items, such as digital threads and digital twins, needed to conduct testing.

OUSD(A&S) officials said that they are currently updating their acquisition policies to identify when the test community should be involved in the development of the acquisition strategy. However, because these policy revisions were still in development at the time of our review, we were unable to assess how the revisions addressed access to digital engineering tools. By not requiring early tester involvement in the development of the acquisition strategy in both acquisition and test and evaluation policy, DOD is missing opportunities to optimize acquisition strategies and test more efficiently to avoid the typical problems that reveal themselves downstream in weapon system acquisition programs.

Conclusions

Through its ongoing modernization planning, DOD has a unique opportunity to not only retool its existing test and evaluation enterprise, but to redefine the role that enterprise can play in enabling faster delivery of relevant capabilities to warfighters. Our prior work identifying the key practices that leading companies employ to successfully develop new products can guide DOD’s efforts. However, modernization plans that advocate rapid, iterative test and evaluation approaches—consistent with leading practices—face headwinds from existing policies that predominantly continue to reflect traditional, linear approaches. These policies, which include ones issued by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Air Force, Army, and Navy, could hamstring potential gains in speed that test and evaluation modernization might achieve.

DOD therefore faces a choice. On the one hand, it could continue to treat test and evaluation as a means of identifying deficiencies in weapon systems already developed and, often, already produced. This would require no changes to existing policy and the status quo, but it does not further DOD’s goal of accelerating delivery of relevant capabilities to warfighters. On the other hand, DOD has an opportunity to embrace test and evaluation as a core foundation of every weapon systems acquisition program. Specifically, it could organize weapon system acquisition strategies, test plans, and strategies around iterative test and evaluation processes, enabled by digital twins and digital threads, that center on rapidly developing minimum viable products. By revising their test and evaluation policies to reflect such leading practices, DOD and the military departments would structure test and evaluation in ways that proactively inform and aid development of weapon systems’ performance requirements and design, underpinned by ongoing and persistent user feedback. This approach, while potentially a significant change in the short term, over the long term would leave DOD better positioned to ensure that warfighter needs are consistently understood, prioritized, and met.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 13 recommendations, including four to the Secretary of Defense (Recommendations 1-3 and 13), three to the Secretary of the Air Force (Recommendations 4-6), three to the Secretary of the Army (Recommendations 7-9), and three to the Secretary of the Navy (Recommendations 10-12):

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation revise their weapon system test and evaluation, digital engineering, and systems engineering policies to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to provide input into the development of acquisition strategies, including on testing-related topics such as the use of and access to digital twins and digital threads. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation revise their weapon system test and evaluation, digital engineering, and systems engineering policies to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative, integrated testing approach enabled by digital twins and digital threads to support delivery of minimum viable products. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation revise their weapon system test and evaluation, digital engineering, and systems engineering policies to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop and implement test strategies and test plans that incorporate end user agreements that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user input and feedback for the system under test. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Air Force should, as the Air Force revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to provide input into the development of acquisition strategies, including on testing-related topics such as the use of and access to digital twins and digital threads. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Air Force should, as the Air Force revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative, integrated testing approach enabled by digital twins and digital threads to support delivery of minimum viable products. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Air Force should, as the Air Force revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop and implement test strategies and test plans that incorporate end user agreements that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user input and feedback for the system under test. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of the Army should, as the Army revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to provide input into the development of acquisition strategies, including on testing-related topics such as the use of and access to digital twins and digital threads. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of the Army should, as the Army revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative, integrated testing approach enabled by digital twins and digital threads to support delivery of minimum viable products. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of the Army should, as the Army revises its weapon system test and evaluation policy, ensure that policy fully reflects leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop and implement test strategies and test plans that incorporate end user agreements that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user input and feedback for the system under test. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of the Navy should revise the military department’s weapon system test and evaluation policy to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to provide input into the development of acquisition strategies, including on testing-related topics such as the use of and access to digital twins and digital threads. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of the Navy should revise the military department’s weapon system test and evaluation policy to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop test strategies and test plans that reflect an iterative, integrated testing approach enabled by digital twins and digital threads to support delivery of minimum viable products. (Recommendation 11)

The Secretary of the Navy should revise the military department’s weapon system test and evaluation policy to fully reflect leading practices for product development by requiring developmental and operational testers to develop and implement test strategies and test plans that incorporate end user agreements that detail a process for obtaining ongoing user input and feedback for the system under test. (Recommendation 12)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment revises its weapon system acquisition policies to require that such acquisition programs obtain and incorporate input from developmental and operational testers in the development of acquisition strategies, including on testing-related topics such as the use of and access to digital twins and digital threads. (Recommendation 13)