SERVICE ACADEMIES

Clarifying Guidance Would Enhance Effectiveness of Honor and Conduct Systems

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Kristy E. Williams at williamsk@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The service academies—West Point, Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine—operate honor and conduct systems to help ensure students adhere to expected ethical and moral standards. Each academy has student-led honor systems to enforce honor codes that prohibit lying, cheating, and stealing; each also has officer-led conduct systems to maintain good order and discipline. However, key differences exist across the academies’ systems, such as the use of hearings and the right to appeal hearing findings or punishments.

Typically, each academy offers procedural due process protections to help ensure that students accused of an honor or conduct offense receive a fair hearing. The academies offer most of the 12 common due process protections GAO reviewed, but some academies’ guidance does not clearly specify the availability of certain protections. For example, two academies do not provide clear guidance on students’ rights to access a complete record of their proceeding. By reviewing and revising honor and conduct system guidance to clearly articulate available protections, the academies can help ensure students are informed of their rights when engaging with processes that could impede their ability to graduate and serve as officers.

The honor and conduct offense data collected by the academies are not always complete or easily accessible. Specifically, some academies do not collect data on certain stages of their honor and conduct systems, such as investigations or appeals. Further, officials from four academies said they faced challenges in accessing relevant data. Addressing these challenges would improve the academies’ ability to manage their systems with quality information

Students GAO surveyed at the academies generally reported favorable opinions about their honor and conduct systems but raised some concerns about their fairness. Between about 25 to 45 percent of students, depending on the academy, said honor system findings were not applied fairly to all students, while about 40 to 55 percent said the same for conduct. Students also stated a reluctance to report honor offenses and minor conduct offenses. However, around 50 to 80 percent of students, depending on the academy, were willing to report major conduct offenses.

Why GAO Did This Study

The service academies seek to graduate military officers with high ethical and moral standards. Students who violate these standards may be disenrolled.

House Report 118-125 includes two provisions for GAO to review academies’ honor and conduct processes. This report assesses the extent to which (1) academy honor and conduct systems compare to one another and provide common procedural due process protections, and (2) academies collect honor and conduct data. It also describes (3) the perceptions of students toward their respective academies’ honor and conduct systems.

GAO reviewed academy policies and honor and conduct data for academic years 2018-2019 through 2023-2024. It also surveyed 6,984 students across the five academies. The survey results are generalizable to the sophomore through senior population at each respective academy. Complete survey results can be viewed at GAO-26-108179. GAO also interviewed academy officials and conducted site visits to each academy.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 13 recommendations, including that the academies assess and update honor and conduct system guidance to ensure that due process protections are clearly articulated and include data collection requirements for all system stages. GAO also recommends the academies address challenges that limit timely access to data. The Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, and Transportation concurred with all recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

Air Force Academy |

United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado |

|

Coast Guard Academy |

United States Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

Merchant Marine Academy |

United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York |

|

Naval Academy |

United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland |

|

UCMJ |

Uniform Code of Military Justice |

|

West Point |

United States Military Academy in West Point, New York |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 16, 2025

Congressional Committees

The U.S. service academies exist to educate and graduate students with the knowledge and character needed to lead as officers in the U.S. armed forces. As future leaders, academy students are expected to possess the highest ethical and moral standards and may be disenrolled for violating them.[1] To help ensure students exemplify these standards, each of the five academies—the United States Military Academy, United States Naval Academy, United States Air Force Academy, United States Coast Guard Academy, and United States Merchant Marine Academy—has honor and conduct systems, which review and adjudicate student misconduct.[2] Nevertheless, there have been several high-profile cases in recent years in which students at each of the academies have been charged with honor or conduct offenses.

House Report 118-125, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes two provisions for us to review the honor and conduct processes at each service academy.[3] Our report examines the extent to which (1) academy honor and conduct systems compare to one another and provide common procedural due process protections; and (2) academies collect honor and conduct data; and describes (3) the perceptions and attitudes of students toward their respective academy’s honor and conduct systems.

For our first objective, we reviewed departmental, service, and academy policies and guidance to compare the academies’ honor and conduct systems and to determine the extent to which they include certain procedural due process protections for students accused of honor or conduct offenses. We assessed this information against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principles that management should communicate quality information to achieve objectives and communicate that information throughout the entity.[4]

For our second objective, we obtained and analyzed data for academic years 2018-2019 through 2023-2024 to identify the type of information that each academy collects related to its honor and conduct systems. We selected data from this period because they constituted the most complete and recent data available. We assessed the reliability of these data by interviewing officials responsible for them, reviewing related documentation and reviewing the data for missing values, outliers, and obvious errors. We determined they were sufficiently reliable for reporting on the academies’ honor and conduct data. We assessed this information against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principle that management should use quality information to achieve objectives.

For our third objective, we surveyed a census of 6,984 sophomore through senior students in academic year 2024-2025 across the five service academies to obtain their perceptions of and experiences with the honor and conduct systems.[5] The response rate to our survey ranged from 31 percent to 94 percent, depending on the academy. The results of our survey are generalizable to the sophomore through senior student population at each respective academy.

For all objectives, we interviewed academy officials involved in the administration of honor and conduct systems. We also conducted site visits to each academy to encourage survey participation and to conduct in-person interviews with school administrators and 23 selected students with experience in either the honor or conduct system, whether as a subject of the systems or as an administrator. Appendix I provides a detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Service Academies

The U.S. has five tuition-free, 4-year degree granting service academies—the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York (hereafter, West Point); the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland (hereafter, the Naval Academy); the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado (hereafter, the Air Force Academy); the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut (hereafter, the Coast Guard Academy); and the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York (hereafter, the Merchant Marine Academy). See figure 1 for the emblems and founding dates for each academy.

As of May 2025, the Department of Defense academies (West Point, Naval, Air Force) each had around 4,500 students, while the Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academies had around 1,000 students. While enrolled at the academies, students have the rank of cadet (Army, Air Force and Coast Guard) or midshipman (Navy) and are considered to be on active duty. Merchant Marine Academy students are also midshipmen, but they are not on active duty.[6]

Students at each academy live in military-style barracks, wear uniforms, and, in addition to the academic curriculum, participate in military training and professional development. The service academies are a major officer commissioning source, accounting for approximately 16 to 51 percent of all active commissioned officers in fiscal year 2022, depending on the branch of service.[7] Except for the Merchant Marine Academy, students are obligated to accept an appointment as a commissioned officer upon graduation and serve 5 years on active duty.[8] Merchant Marine Academy students may commission as an officer and serve 5 years on active duty in any branch of the U.S. military or in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or enter the U.S. maritime private industry for 5 years while serving as an officer in any reserve unit of the U.S. military for 8 years.[9]

Academy Oversight Responsibilities

Various entities have oversight responsibility for the academies. There are three entities that oversee the military service academies (West Point, Naval, and Air Force): the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, the Board of Visitors for each academy, and the military department Secretaries.[10] The Coast Guard and the Merchant Marine Academies have multiple entities responsible for academy oversight. Specifically, the Coast Guard Academy is overseen by the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, a Board of Visitors, and a Board of Trustees.[11] The Merchant Marine Academy is overseen by the Secretary of Transportation, a Board of Visitors, and an Advisory Board.[12]

Each academy is led by a Superintendent who is responsible for the operation and management of the academy.[13] A Commandant of Cadets or Midshipmen and an Academic Dean or Provost serve under the Superintendent and have functional responsibility for the student body and faculty, respectively.[14] The Commandant at each academy is responsible for the training, discipline, and administration of the student body.[15] Each academy also has a student chain of command that operates alongside the officer chain of command and has progressively greater leadership responsibilities as students advance through their academic career.

Academy Honor and Conduct Systems

In support of the service academies’ missions to educate and graduate students with knowledge and character, students are expected to possess the highest ethical and moral standards. Academy students are expected to adhere to civilian laws, the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), and departmental and academy directives and standards.[16] Each academy operates honor and conduct systems to provide students with relevant training designed to help maintain discipline and standards. Moreover, these systems facilitate the reporting, investigation, and adjudication of reported offenses; the discipline of students who commit offenses; and the appeal of certain findings or punishments.

· Honor Systems. Academy students are expected to adhere to honor codes, which prohibit lying, cheating, or stealing.[17] The honor systems are generally student-led, with students administering the reporting, investigation, and hearing processes. Students also serve as honor staff who perform specific duties, such as scheduling honor hearings.[18] Honor staff also generally serve on honor boards, which are student-comprised entities that hear cases of accused students at honor hearings and vote to determine if an accused student committed an honor violation. As noted previously, each academy’s Superintendent, Commandant, and designated officers are responsible for oversight of these systems and for disciplining students found guilty of an honor offense.[19] Figure 2 shows public displays at each academy that remind students to conduct themselves with honor.

· Conduct Systems. Academies use their conduct systems to maintain good order and discipline by providing regulations and processes for adjudicating a variety of misconduct that ranges from minor offenses, such as a deviation from uniform standards, to major offenses, such as illegal drug use.[20] Accordingly, conduct offenses are generally grouped into minor and major offense classifications at each academy.[21] Table 1 provides a range of examples of minor and major offenses as defined in relevant academy guidance.

|

|

West Point |

Naval |

Air Force |

Coast Guard |

Merchant Marine |

|

Minor |

Being late to class; being disrespectful to a superior officer. |

Failure to perform a duty properly; unsatisfactory appearance in uniform. |

Late to class or formation; improper pass usage. |

Asleep at unauthorized time or place; tobacco or electronic smoking device use on academy grounds. |

Failing to comply with orders of an officer; late to class; improper performance of mess hall duty. |

|

Major |

Wrongful use or possession of controlled substances (drugs); criminal conviction; hazing. |

Fraternization of a romantic or sexual nature; providing alcohol to underage persons. |

Possession of unauthorized weapon; driving under the influence. |

Assault; bullying; slander or libel. |

Gambling for money or other items of value; possession, use, or sale of drugs. |

Source: GAO review of service academy guidance. | GAO‑26‑107049

Notes: For the purposes of this report, we grouped conduct offenses into minor and major offense classifications for each academy. Criminal offenses such as serious violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice or of local, state or federal law are adjudicated through those respective judiciary processes, such as court-martial.

The conduct systems are officer-run, with officers administering reporting, investigation, adjudication, and discipline processes.[22] The rank of the adjudicator, formality of proceedings, and allowable punishments escalate in response to the severity of the offense. All students may report conduct offenses, and all the academies encourage students to address less severe minor offenses immediately, without the need for formal punishment. Criminal offenses such as serious violations of the UCMJ or of local, state, or federal law are adjudicated through those respective judiciary processes, such as court-martial. However, academies are not precluded from also using the conduct system to discipline students for offenses that are coincident to the criminal offense or if the court-martial convening authority or external entity declines to prosecute, according to officials.

While the honor and conduct systems generally operate independent of one another, there are instances in which these bodies may coordinate to address student misconduct. For example, Air Force Academy officials told us that some offenses, such as lying on an official form, are covered by both honor and conduct systems and may be addressed through either the honor process or the conduct process. In addition, an incident that includes a mix of honor and conduct offenses may be addressed under both respective systems, according to officials from each academy. For example, Naval Academy officials told us that if a student was found to have been drinking underage and to have also lied about it, the underage drinking charge would be processed under the conduct system, and the lie would be processed under the honor system.

Students who resign or are disenrolled from the academies for honor or conduct offenses may be required to complete a period of active duty enlisted service or to reimburse the federal government for the cost of their education.[23] While honor and conduct offense records are maintained at the academies, such information is generally not included in individuals’ records once they become commissioned officers, according to officials.

Procedural Due Process Protections

Procedural due process refers to safeguards afforded to individuals involved in adjudicatory proceedings to help ensure that official governmental action meets minimum standards of fairness. To help ensure fairness, adjudicatory systems are typically designed to minimize or structure the discretion of the adjudicator(s) by imposing standardized procedures and mandating certain protections for the accused. The concept of due process is embodied in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution and states that no person shall “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Due process protections are generally greater in criminal proceedings than in civil proceedings, such as administrative hearings. However, per case law, the courts view procedural due process as a concept that should be flexibly applied to fit the circumstances and may vary by subgroups and settings. Courts have established that students facing expulsion from tax-supported colleges and universities have constitutionally protected interests that require certain due process protections and established standards for student disciplinary proceedings.[24] The courts have also ruled that the government’s interest in assuring the fitness of future military officers permits the academies greater freedom in providing such protections than in civilian institutions.[25]

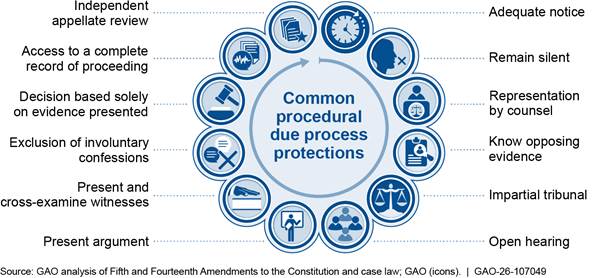

There are 12 categories of procedural due process rights commonly used to ensure fairness in hearings (see figure 3).[26]

· The right to adequate notice prescribes a minimum amount of time between an individual being informed of an accusation against them, including the nature of the accusation, and its adjudication.

· The right to remain silent prescribes protection from self-incrimination, including awareness of the protection and the ability to invoke it at any time.

· The right to representation by counsel prescribes the rights of individuals to seek counsel and to have counsel accompany them and speak on their behalf at a hearing.

· The right to know opposing evidence prescribes the ability of the individual to be aware of the case made against them before their hearing begins.

· The right to an impartial tribunal prescribes protection from a judgment made by members of the tribunal who may have biases based on a relationship with the individual, and the burden of proof required to find an individual guilty.

· The right to an open hearing prescribes protection from unfair hearings by subjecting them to outside scrutiny, balanced against the individual’s right to privacy.

· The right to present argument prescribes the ability of the individual to make statements and present evidence.

· The right to present and cross-examine witnesses prescribes the ability of the individual to be aware of and confront witnesses against them, as well as to provide their own in support of their case.

· The right to exclusion of involuntary confessions made by an individual prescribes the exclusion of admissions or statements made before being given the right to remain silent.

· The right to have a decision based solely on the evidence presented prescribes the protection provided by any evidentiary standards and requirements to find an individual guilty based on that evidence

· The right to a complete record of the proceedings for the individual prescribes the ability to obtain records of the hearing, including any rationale for the decision and punishment.

· The right to independent appellate review prescribes the opportunity to identify whether there were any legal shortcomings that may have worked to the disadvantage of the individual.

Honor and Conduct Systems Have Similarities and Differences and Guidance Does Not Clearly Articulate Availability of Some Due Process Protections

Academy Honor and Conduct Systems Share Some Similarities

The service academies’ honor and conduct systems are similar in that they all generally progress through five stages when addressing an alleged offense. These include: (1) reporting an alleged offense, (2) investigation of allegation(s), (3) adjudication to determine whether the alleged offense occurred, (4) determination of punishment or discipline for validated allegations, and (5) option to appeal if found guilty. There are similarities within each stage of the academies’ honor and conduct systems that are described in further detail below.

Honor System

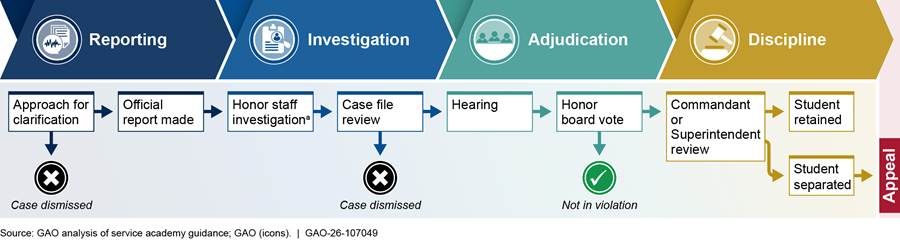

There are similarities in how the academies address each stage of an alleged honor offense. Figure 4 provides an overview of these shared practices followed by additional stage-by-stage details.

aAt the Coast Guard Academy, investigations are completed as part of the conduct investigation process.

Reporting. Academies typically encourage any student or staff member who suspects a violation of the honor code to first engage in an “approach for clarification.” This involves discussing the alleged offense directly with the individual in question to address and potentially resolve any misunderstandings. If an honor offense is still suspected after the approach for clarification, then the student or staff member may make an official report directly to student honor staff or through the student or officer chains of command.

Investigation. Once an honor offense allegation is reported, students from the honor staff are appointed to investigate. These students conduct interviews with relevant parties and collect evidence that they will use to develop a case file for review.[27] Officers who oversee the honor system review the case file and determine whether there is sufficient evidence to proceed to an honor hearing.[28]

Adjudication. If the case file review finds sufficient evidence of an offense, a formal hearing is convened. During the hearing, student honor board members review the case file and conclude by voting on whether the accused student committed the offense.

Discipline. If the honor board finds the student guilty of the offense, it will develop a recommendation for disciplinary action, focusing mainly on whether the student should be disenrolled or retained at the academy. The case file, along with the board’s recommendation, is then typically sent to the Commandant or Superintendent for further review and to decide the appropriate punishment.

Appeal. A student found guilty of an honor offense and recommended for disenrollment may appeal the decision to the appropriate authority or to an administrative board, depending on the academy.[29]

Conduct System

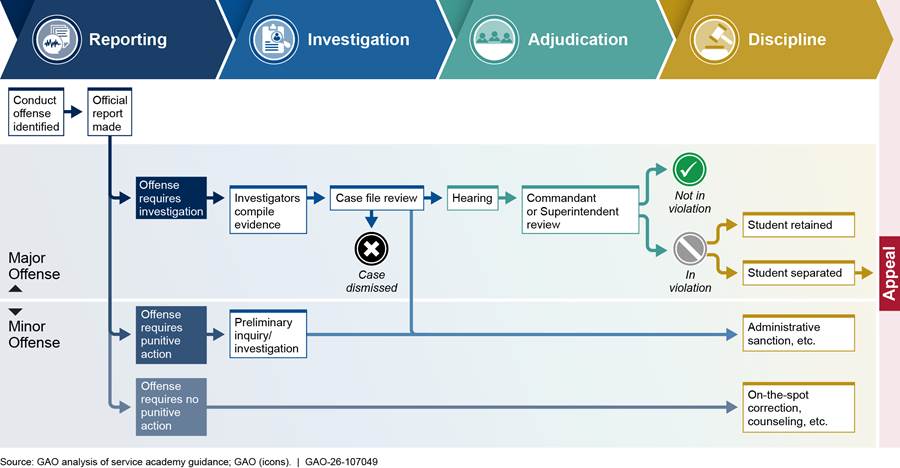

We also identified similarities in how the academies approach each stage of addressing an alleged conduct offense. Figure 5 provides an overview of these shared practices followed by additional stage-by-stage details.

Figure 5: Shared Stages of Service Academies’ Conduct Systems: Major and Minor Offense Case Scenarios

Reporting. Students or staff members generally may report conduct offenses through the student and officer chains of command. Offenses such as sexual assault and sexual harassment are typically handled through judicial processes given their severity.[30] However, such allegations may be reviewed as a conduct offense if the convening authority decides not to take judicial action.[31]

Investigation. The decision to investigate an alleged conduct offense depends, in part, on whether it is deemed to be a major or minor offense. Specifically, major offenses are typically investigated, whereas minor offenses do not always require an investigation, according to academy officials. The type of investigation is also circumstance dependent and may be done as an officer-led investigation or a criminal investigation conducted by a military criminal investigative organization, military police, or civilian law enforcement.[32] An Air Force Academy official provided the example that if a student is suspected of destroying government property by kicking through a locked door but does not admit to it, an investigating officer would be assigned to conduct interviews and obtain evidence such as surveillance footage. The official further stated that the officer would complete the investigation in accordance with relevant service or academy guidance. However, the official further explained that guidance may require that certain offenses such as sexual assault or damages over a specified dollar amount be investigated by a military criminal investigative organization or military police.[33] In general, the appropriate authority reviews the file for conduct systems cases in which an investigation has been completed and determines whether there is sufficient evidence to move forward with adjudication.

Adjudication. The adjudicating authority is a designated officer, who, depending on the academy and severity of the alleged offense, may include the Commandant, Deputy Commandant, or relevant brigade or company officer. The rank of the adjudicator and formality of proceedings is determined by whether the alleged offense is deemed to be major or minor. Major offenses are typically adjudicated via a formal hearing. During the hearing, the adjudicating authority reviews the case file and, depending on the academy, may consider witness testimony and any relevant evidence submitted by the accused and determines guilt. For cases that proceed to disenrollment, the Superintendent is involved. Minor offenses are typically adjudicated by the student or officer chains of command, and, depending on the academy, may or may not involve a formal hearing.

Discipline. Punishments escalate in response to the severity of the offense and tend to be similar across different academies. For major offenses, discipline is determined by the officer chain of command and punishments may include administrative sanctions, such as demerits, extra duty or military instruction, and tours; remediation or probation; or disenrollment.[34] For minor offenses, discipline may be determined by either the student or officer chains of command. As noted previously, all academies generally encourage students to address less severe minor offenses immediately, without the need for formal punishment. According to academy officials, these minor offenses—such as uniform violations—are addressed through nonpunitive methods, such as on-the-spot verbal correction or counseling. For minor offenses that require formal punishment, such punishments typically involve some form of administrative sanctions.

Appeal. Students found guilty of a conduct offense and recommended for disenrollment may appeal the decision to the appropriate authority or to an administrative board, depending on the academy.[35]

Key Differences Distinguish Academies’ Honor and Conduct Systems

While there are similarities in the academies’ honor and conduct systems, there are also key differences.

Honor Systems

We identified five key differences in how academy honor systems operate. These differences include the (1) types of offenses recognized as actionable, (2) legal review of investigation findings, (3) types of hearings, (4) authority and discretion of adjudicators, and (5) accused’s right to appeal.

Types of Offenses

Beyond the standard honor code offenses of lying, cheating, and stealing, West Point and the Air Force Academy also have a toleration clause, meaning that students who witness an honor offense and fail to report it are considered to be in violation themselves and can face punishment.[36] According to a West Point official, the toleration clause requires a commissioned leader of character to report honor offenses, but added that this rarely occurs in practice. Air Force officials stated that the toleration clause has been part of the academy’s framework since its inception, and that they revised their honor guidance in 2023 due to concerns that students were deliberately avoiding confronting misconduct or, at worst, feigning ignorance of offenses to avoid being accused of tolerating an honor offense.[37] However, in May 2025, the Air Force reverted to its former toleration clause requiring students of all class years to report a suspected honor offense, which officials attributed to a cheating incident occurring earlier in the year.[38]

Legal Review of Investigation Findings

To help ensure sufficient evidence, three academies (West Point, Naval, and Air Force) require government attorneys to review honor investigation findings in conjunction with officers before proceeding to a hearing. However, the other two academies (Coast Guard and Merchant Marine) proceed to a hearing after review by the Commandant or Assistant Commandant at the Coast Guard Academy and after a review by the Honor Board Chair and subsequent investigation at the Merchant Marine Academy. Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academy officials told us that they do not have the capacity or resources to complete legal reviews of every honor investigation and do not think such a review is necessary to ensure appropriate due process.

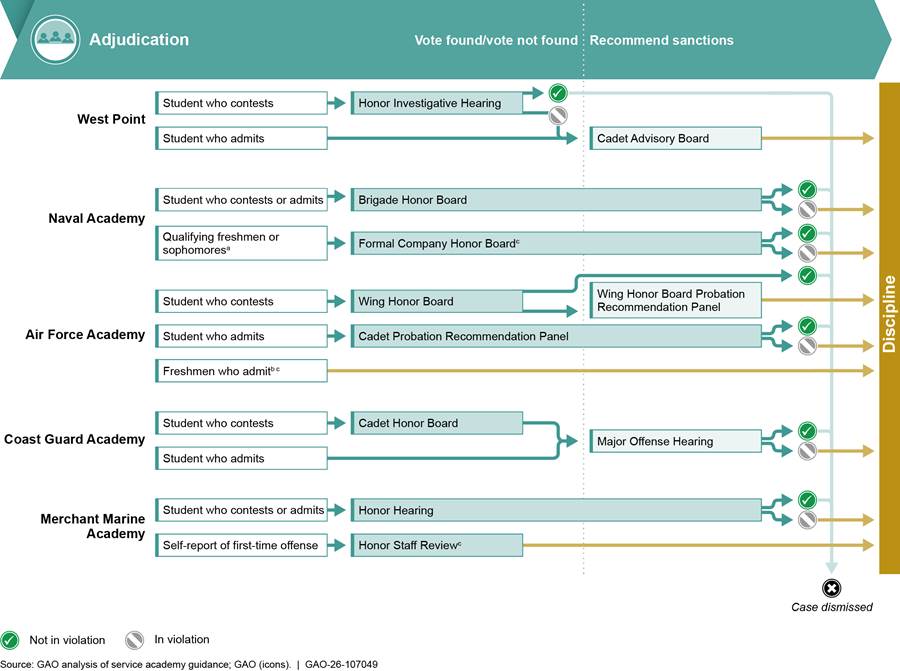

Hearing Types

Four academies (West Point, Naval, Air Force, and Merchant Marine) adjudicate honor offenses through hearings, but for some academies, the type of hearing varies based on whether the accused preemptively admits to the alleged offense or contests it. Specifically, West Point and the Air Force Academy hold different types of hearings depending on the accused’s admission or denial of guilt. For admitted offenses, validation occurs before the hearing, which then focuses on the honor board’s recommendation for retention or disenrollment. Conversely, the Naval and Merchant Marine Academies conduct the same type of hearing regardless of how the individual pleads.[39] At these academies, validation of the offense takes place during the hearing itself. At the Coast Guard Academy, the honor board is considered to be an advisory body to the Commandant of Cadets and only holds hearings in certain situations, such as for contested cases.

At three academies (Naval, Air Force, and Merchant Marine), qualifying students who admit to the offense may be routed to a different hearing or proceed directly to the disciplinary phase where the possibility of immediate disenrollment is eliminated.[40] See figure 6 for additional details on the academies’ hearing processes.

aAfter the investigation, the Brigade Honor Advisor may refer cases involving freshmen or sophomores who admit to an offense and show remorse to the Formal Company Honor Board for review. The Brigade Honor Board may also unanimously approve a voting member’s motion to refer qualifying students to the Formal Company Honor Board.

bFreshmen who commit non-egregious honor offenses that meet certain criteria may waive the Cadet Probation Recommendation Panel and receive immediate honor probation. These criteria are (1) the offense occurring prior to lesson T20 of Spring Semester; (2) the student admitting to the offense on the Honor Allegation Notification form; (3) the student having had no prior honor offenses or pending cases; (4) the student cannot be facing more than one honor offense allegation; and (5) the offense does not involve aiding other students to violate the honor code.

cStudents who qualify for this process are not subject to immediate disenrollment but may ultimately be recommended for it if they fail to complete their required honor remediation or probation.

Disciplinary Authority and Discretion

The authority to discipline students for honor offenses varies by academy and depends on the specific circumstances of each case. At West Point, the Superintendent is responsible for issuing disciplinary actions to all students that have been found to have violated the honor code. In contrast, at the other four academies (Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine), this authority is mainly reserved for cases where disenrollment is recommended, while other cases are typically handled by the Commandant or other authority.

The extent to which a disciplinary authority is obligated to accept the student honor board’s findings (i.e., the adjudicator’s discretion) also varies by academy. Specifically, at three academies (West Point, Naval, and Air Force) disciplinary authorities are prohibited from overturning unfounded findings, although they do have the authority to challenge certain founded cases. In contrast, the Merchant Marine Academy allows disciplinary authorities to overrule the honor board’s decisions entirely. Meanwhile, at the Coast Guard Academy, where all honor offenses are major conduct offenses, disciplinary authorities are only expected to consider the honor board’s findings and ultimately determine whether a case should proceed to a Major Offense Hearing.

See table 2 for a comparison of disciplinary authority and discretion at each academy.

|

Academy |

Disciplinary authority |

Hearing findings binding on disciplinary adjudicatora |

Potential disciplinary actions |

|

West Point |

Superintendent. The chain of command and Commandant provide recommendations to retain or disenroll.b |

· Yes for unfounded cases. · No for founded cases if adjudicator finds a lack of evidence. |

Superintendent may retain student or recommend disenrollment to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs.c All students found in violation are put on honor probation and assigned sanctions.d |

|

Naval |

Superintendent and Secretary of the Navy make decisions on disenrollments; other cases handled by Battalion Officer or Commandant.e |

· Yes for unfounded cases. · No for founded cases if the Commandant finds a serious honor board error. |

Commandant may place student on honor probation, which may include sanctions, or recommend disenrollment. Superintendent may recommend disenrollment to the Secretary of the Navy or retain and refer back to Commandant.f |

|

Air Force |

Superintendent makes decisions on disenrollments; other cases handled by Commandant. |

· Yes except when the Superintendent considers disenrollment. |

Commandant may place student on honor probation, which includes sanctions, or recommend disenrollment. The Superintendent has all options available.g |

|

Coast Guard |

Superintendent makes decisions on disenrollments; other cases handled by Commandant or other authority.h |

· No, Cadet Honor Board findings are considered advisory. |

Major Offense Hearing Authority may retain the student, recommend disenrollment, or impose other penalties such as remediation. |

|

Merchant Marine |

Superintendent makes decisions on deferred graduations, setbacks, and disenrollments; other cases handled by Commandant. |

· No |

Commandant may place student on honor probation, which may include sanctions, and remediation or recommend deferred graduation, setback, or disenrollment to the Superintendent. The Superintendent has all options available.i |

Source: GAO analysis of service academy guidance. | GAO‑26‑107049

aFinding refers to whether the student was found in violation (called founded here) or not in violation (unfounded).

bThe Commandant is the final authority for new student cases. New students are those in summer training prior to Acceptance Day, which marks their transition to freshmen.

cWest Point freshmen and sophomores can be directly disenrolled by the Superintendent.

dWhile students can face probation or other sanctions, the Superintendent may set aside “founded” findings if he or she determines they are not supported by evidence and can close the case, direct further investigation, or direct enrollment in honor probation (called the Special Leader Development Program).

eThe Battalion Officer adjudicates cases for freshmen and sophomores with no prior honor offenses and for which the board voted on a recommendation for retention or where their vote for disenrollment did not reach seven of nine board members. The Commandant adjudicates cases for juniors and seniors and all repeat honor offenders.

fIf the Superintendent refers the case back to the Commandant, they may take no further action or place the midshipman on honor probation or remediation, which may include sanctions.

gThe Superintendent can take no action, place the cadet in honor probation, or disenroll the cadet. This decision is final. Honor probation includes certain administrative sanctions such as removal of all rank.

hExamples of other authorities include the Assistant Commandant of Cadets, Company Officers, and the Chief of Cadet Training and Operations Branch. According to officials, the hearing authority is chosen by the circumstances of the case.

iThe Superintendent may impose deferred graduation, setback (i.e., temporary separation from the Academy), disenrollment, exonerate, or refer back to the Commandant for honor probation and remediation.

Further, two academies’ policies (West Point and Air Force), limit disciplinary authority discretion in assigning punishments by requiring that students found guilty of an honor offense immediately be given a prescribed set of sanctions, such as restriction, reduction in rank, and placed into a remediation or probation program. At the Naval, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine Academies, the disciplinary authority has more discretion to determine what punishments to apply, including sanctions and whether the student will enter remediation or probation.

Appeal

A student’s right to appeal honor hearing findings and sanctions also varies by academy. Four academies (Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard and Merchant Marine) allow students to appeal honor hearing findings if new evidence is provided, while West Point does not.[41] Further, four academies (West Point, Naval, Coast Guard and Merchant Marine) allow students to appeal imposed sanctions, whereas the Air Force Academy does not.[42] As noted previously, students at all academies have the option to appeal a recommendation for disenrollment to the appropriate authority or to an administrative board, depending on the academy.

Conduct Systems

We identified five key differences in how academy conduct systems operate, including (1) student roles and responsibilities, (2) the use of hearings, (3) the disenrollment authority and proceedings, (4) the right to appeal, and (5) the use of nonjudicial punishment.

Student Roles and Responsibilities

As noted previously, all academies generally encourage students to address less severe minor offenses immediately, without the need for formal punishment. However, three academies (Naval, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine) delegate extra responsibilities to certain students for overseeing conduct offenses. Specifically, at the Naval Academy, the student chain of command is empowered to establish a Midshipman Independent Review Board, which is responsible for reviewing and addressing a student’s trend of small offenses. In addition, student company commanders at the Naval Academy are authorized to adjudicate minor offenses committed by freshmen-through-junior students. At the Coast Guard Academy, the student chain of command can directly adjudicate minor conduct offenses.[43] Meanwhile, at the Merchant Marine Academy, students adjudicate certain minor offense hearings but do so under the supervision of an officer.[44]

The Naval and Coast Guard Academies have also codified specific steps in policy that students should follow when holding others accountable for minor offenses. In general, students are advised to first provide verbal correction and then proceed to more formal types of punishment, such as written correction or assigning extra military instruction for subsequent offenses.[45]

Use of Hearings

Three academies (West Point, Naval, and Merchant Marine) hold hearings to adjudicate both major and minor offenses. Specifically, West Point uses Misconduct Hearings to address major offenses and Article 10 hearings to address minor offenses; the Naval Academy uses Adjudicative Hearings to address both offense types; and the Merchant Marine Academy uses Class I Masts for major offenses and Class II Masts for minor offenses.[46]

In contrast, one academy, the Coast Guard Academy, uses Major Hearings to address major offenses but does not use hearings to address minor offenses.[47] Finally, at the remaining academy, the Air Force Academy, hearings are not typically required to adjudicate offenses, but they may use student-run Squadron or Group Command Review Boards to review student performance, take disciplinary action, or make sanction recommendations to the squadron or group commander, an officer, for adjudication.[48]

Disenrollment Authority and Proceedings

The same three academies that hold hearings to adjudicate both major and minor offenses (West Point, Naval, and Merchant Marine) require disenrollments to be approved by service-level leadership. Specifically, the authority for West Point juniors and seniors is the Assistant Secretary of the Army; for Naval Academy students disenrolled for honor or conduct offenses is the Assistant Secretary of the Navy; and for all Merchant Marine Academy disenrollments is the Assistant Secretary for Administration.[49] In contrast, the disenrollment authority at the Air Force and Coast Guard Academies is typically the Superintendent.[50]

The academies also use different proceedings for disenrollment. Specifically, at four academies (Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine) a fact-finding Board may be held prior to the Superintendent’s decision or recommendation to the adjudicating authority.[51] However, at the Naval and Air Force Academies, these Boards are reserved for disenrollment under other than honorable conditions. Finally, at three academies (Naval, Air Force, and Coast Guard) students recommended for disenrollment have the option to meet with the Commandant of Cadets or Superintendent, depending on the infraction, prior to his or her decision.

Appeal

As with the honor system, a student’s right to appeal conduct hearing findings and sanctions differs by academy. Three academies (Naval, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine) allow students to appeal major conduct hearing findings and sanctions under certain circumstances, while the other academies (West Point and Air Force) do not.[52] All academies permit their students to appeal a recommendation for disenrollment.

Use of Nonjudicial Punishment

Of the four academies where students are subject to the UCMJ, two academies (Air Force and Coast Guard) offer nonjudicial punishment as an option for adjudicating conduct offenses, while the other two (West Point and Naval Academy) do not.[53] The Merchant Marine Academy is not subject to the UCMJ and therefore does not use nonjudicial punishment.

Air Force and Coast Guard Academy officials stated that the decision to use nonjudicial punishment is at the commander’s discretion, given that both the conduct system and nonjudicial punishment are designed to handle similar types of offenses.[54] They stated that factors such as the severity of the offense and any history of prior misconduct play a role in this decision-making process. However, Coast Guard Academy officials told us that they rarely use nonjudicial punishment, as they consider the conduct system to generally be better suited to address any misconduct issues that arise in the academy setting.

West Point and Naval Academy officials told us that while nonjudicial punishment is not an official form of discipline at their academies, their conduct systems generally serve the same function. Specifically, West Point officials stated that the Article 10 hearings used to adjudicate minor offenses closely mirror nonjudicial punishment, except that any Article 10 punishments are not documented outside the student’s academy record and do not follow them once they are commissioned. Similarly, Naval Academy officials stated that the conduct system is designed to more efficiently and effectively address misconduct and remediate students than nonjudicial punishment. Further, these officials stated that a subject’s right to request a court-martial in lieu of nonjudicial punishment could potentially increase the number of courts martial, which would be a substantial strain on academy resources.

Academy Guidance Does Not Clearly Articulate the Full Range of Due Process Protections Available for Honor and Conduct Offenses

The academies’ honor and conduct guidance clearly identifies that students are entitled to some of the 12 procedural due process protections commonly used in judicial and administrative proceedings.[55] However, the availability of other protections is vague or not mentioned at all.

Honor Systems

Our analysis of each academy’s honor system determined that four of five academies provide 10 of the 12 common procedural due process protections to students accused of an honor offense and that West Point provides all 12. The provision of the remaining two due process protections, or whether guidance specifically addressed them, varied among the academies. While the academies similarly offer many of these protections, how they are implemented can vary, in ways such as the timeline for notifying students of charges and whether government legal counsel is available free of charge.[56] Table 3 provides details on the due process protections each academy provides to students accused of honor offenses.

|

|

West Point |

Naval |

Air Force |

Coast Guard |

Merchant Marine |

|

Adequate notice |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Right to remain silent |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Legal representation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Know opposing evidence |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Impartial tribunal |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Open hearing |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Present argument |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Present and cross-examine witnesses |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Exclusion of involuntary confessions |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Decision based on evidence presented |

Yes |

Guidance |

Guidance |

Guidance unclear |

Guidance |

|

Access to a complete record of proceeding |

Yes |

Guidance |

Yes |

Guidance |

Yes |

|

Right to appeal |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: GAO analysis of service academy guidance. | GAO‑26‑107049

Based on our analysis, we found that guidance on the availability of two protections—the right to a decision based on evidence presented and the right to a complete record of the proceeding—was either unclear or lacking at four of the academies. Below, we provide additional information on those due process protections that were missing or unclear in academy guidance.

Right to Decision Based on Evidence Presented

While all academies provide a right to a decision based on evidence presented, three of them do not clearly define in guidance what types of evidence are allowed and four of them do not thoroughly address protections against illegal search and seizure or the related exclusion of evidence in their guidance.

The presentation of evidence plays a crucial role in honor board hearings and may come in various forms, such as documentation and witness testimonies. While all academies recognize the significance of evidence, officials from the Naval, Air Force, and Merchant Marine Academies told us that certain types of evidence—such as hearsay, which typically would not be admissible in legal contexts, depending on the circumstances—can be used in honor proceedings. However, these academies’ existing guidance does not clearly define what types of evidence are allowed. For example, Naval Academy guidance establishes that any relevant evidence can be considered, and relevancy is determined by the presiding officer in consultation with a judge advocate general. This ambiguity regarding hearsay may lead to misunderstandings among students facing accusations regarding evidentiary standards in honor cases.

Similarly, Air Force Academy guidance states that all evidence deemed relevant by the presiding officer is permissible, but it likewise does not clarify whether hearsay may be used. Merchant Marine Academy guidance acknowledges that the rules of evidence for judicial proceedings do not apply to Honor Boards. However, while students may object to particular pieces of evidence presented in honor board hearings, the guidance does not discuss grounds for objection or explicitly confirm whether all forms of evidence, including hearsay, are acceptable though officials told us that they are.

Additionally, officials at all academies told us that unlawful search and seizure is prohibited in honor investigations to help ensure evidence is obtained in accordance with a student’s civil rights. However, written guidance for the Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine Academies does not clearly articulate this right or the related exclusion of evidence. Officials from these other academies did not consider the absence of this protection in their honor system guidance to be an issue because they said it is provided for elsewhere, such as in the U.S. Constitution and the UCMJ.

Right to Access a Complete Record of the Proceeding

A record of the proceeding can aid the accused in evaluating options for appeal or in understanding the rationale for the verdict. West Point, Air Force, and Merchant Marine Academy guidance specifies that students are entitled to a complete record of their honor hearing. In contrast, Naval and Coast Guard Academy guidance does not include such a provision.

Naval Academy officials told us that a student accused of an honor offense may request to listen to a recording of their hearing, but it can only take place in the office that oversees the honor system. Further, students are not permitted to make a copy of the recordings or of other materials from their case unless they file a Freedom of Information Act request for the records. However, Naval Academy guidance does not state or describe these access rights. Coast Guard Academy officials told us that they do not record or transcribe honor hearings but said that a scribe is designated to take written notes at every major offense hearing, including honor hearings. However, Coast Guard Academy guidance does not specify under what circumstances the notes may be available to a student or how to make such a request.

Conduct Systems

We also analyzed the academies’ conduct systems and found that all academies provide six of the 12 common procedural due process protections to students accused of a conduct offense.[57] The provision of the remaining six due process protections, or whether guidance specifically addressed them, varied among the academies. As with honor processes, the manner in which these protections are implemented can vary. Table 4 provides details on the due process protections each academy provides students accused of conduct offenses.

|

|

West Point |

Naval |

Air Force |

Coast Guard |

Merchant Marine |

|

Adequate notice |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Right to remain silent |

Yes |

Yes |

Guidance unclear |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Legal representation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Know opposing evidence |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Impartial tribunal |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Open hearing |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Present argument |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Guidance uncleara |

|

Present and cross-examine witnesses |

Yesb |

Yes |

Guidance |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Exclusion of involuntary confessions |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Decision based on evidence presented |

Guidance unclearc |

Yes |

Guidance |

Guidance |

Guidance |

|

Access to a complete record of proceeding |

Yes |

Guidance |

Yes |

Guidance |

Yes |

|

Right to appeal |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: GAO analysis of service academy guidance. | GAO‑26‑107049

Note: We reviewed West Point misconduct hearings and Article 10 proceedings; Naval Academy adjudicative hearings; Air Force Academy Form 10, Letter of Notification, and Board of Inquiry processes; Coast Guard Academy Major Offense Hearings; and Merchant Marine Academy Class I Masts, Executive Boards and Superintendent Hearings.

aAccording to officials, students may make opening and closing statements in Class I Masts, Executive Boards, and Superintendent Hearings. However, only Executive Boards and Superintendent Hearings establish this right in written guidance.

bWest Point allows respondents to cross examine witnesses during misconduct hearings; however, they leave this to the discretion of the tactical officer during Article 10 proceedings

cDuring misconduct hearings, misconduct hearing guidance prohibits the use of evidence that was obtained from an unlawful search and seizure. To the contrary, Article 10 guidance states that the rules of evidence do not apply; it allows the tactical officer to consider any evidence that is “relevant to the offense.”

Based on our analysis, we found that guidance on the availability of six protections—right to remain silent, right to an open hearing, right to present argument, right to present and cross-examine witnesses, right to a decision based on evidence presented, and right to a complete record of proceedings—was either unclear or lacking among the five academies. Below, we provide additional information on those due process protections that were missing or unclear in academy guidance.

Right to Remain Silent

Air Force Academy officials told us that students have the right to remain silent when they are facing UCMJ actions, which they said students are trained on prior to their freshman year. However, Air Force conduct guidance does not specify that a student accused of a conduct offense that is not a UCMJ offense is entitled to this protection.

Right to Open Hearing

As noted previously, at the Air Force Academy, hearings are not typically required to adjudicate offenses and therefore there is not a consistent right to an open hearing.[58] However, the right to an open hearing may be provided at a Board of Inquiry for students recommended for disenrollment from the academy under other than honorable conditions. Per guidance, Boards of Inquiry may be opened to spectators at the request of the respondent, with the approval of the board president in consultation with the legal advisor.

Right to Present Argument

Merchant Marine Academy officials told us that students accused of a conduct offense have the right to make a statement to the Deputy Commandant or Regimental Commander who is adjudicating their Class I Mast. However, this right is not clearly articulated in existing guidance, which may limit a student’s awareness that they are permitted to make a statement on their own behalf at these conduct hearings. Merchant Marine Academy officials told us that they plan to clarify the availability of this protection in future revisions of their conduct system guidance. However, they have not provided a timeline for when these revisions will take place.

Right to Present and Cross-Examine Witnesses

All academies that use hearings with binding outcomes allow the presentation and cross-examination of witnesses, but Air Force guidance is unclear on the use of witness statements. As previously noted, the Air Force Academy use of hearings is limited to non-binding student-run hearings that make recommendations for sanctions to officers and for students facing disenrollment under other than honorable conditions. Air Force officials told us that students may include witness statements in their written rebuttals for disenrollment proceedings. However, their guidance does not specify whether the accused can include witness statements in their rebuttal to a conduct allegation or disenrollment notice. Clearly outlining how witness statements can be submitted as evidence in guidance would enhance students’ understanding of their rights during these administrative proceedings.

Right to Decision Based on Evidence Presented

While all academies provide a right to a decision based on evidence presented, four of them do not thoroughly address protections against illegal search and seizure or the related exclusion of evidence in their guidance. As with the honor systems, officials stated that academies generally provide protections against illegal search and seizure through external sources, such as the UCMJ and the U.S. Constitution. However, written guidance for West Point, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine Academies does not clearly articulate this right or the exclusion of evidence resulting from illegal search and seizure in all types of conduct proceedings, even though officials assert that these protections apply.

Specifically, West Point’s Article 10 guidance specifies that tactical officers are not bound by the rules of evidence and may consider any evidence relevant to the offense, but it does not discuss protection from illegal search and seizure. Officials told us that they advise officers against imposing punishment if it is evident that a cadet’s rights have been infringed upon. At the Air Force Academy, guidance does not address protection from search and seizure, but according to officials, their students are protected by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Military Rules of Evidence for searches. Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academy officials told us that they would apply the right as described in laws or guidance outside of their own conduct guidance—specifically, the UCMJ for the Coast Guard Academy and the Fourth Amendment for the Merchant Marine Academy. The conduct processes at these academies, like the honor processes, generally do not follow formal rules of evidence and may accept types of evidence that are normally inadmissible in legal proceedings, such as hearsay. Consequently, it may be unclear to students subjected to these processes whether evidence from illegal searches and seizures may be used. By more explicitly detailing this and other protections available to students in their conduct guidance, the West Point, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine Academies could enhance students’ understanding of their administrative due process rights.

Right to Access a Complete Record of Proceedings

The Naval and Coast Guard Academies’ guidance does not clearly specify whether students are entitled to a complete record of their conduct hearing. Specifically, Naval Academy officials told us that, upon request, students may access some records of their conduct hearing, but officials said that access to the complete record would require that they submit a Freedom of Information Act request. However, this is not specified in the academy’s existing conduct system guidance. As with honor proceedings, Coast Guard Academy officials told us that they do not record or transcribe conduct proceedings but said that a scribe is designated to take written notes at every major offense hearing. However, Coast Guard Academy guidance does not specify when or how the accused may request access to these notes.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should communicate quality information to achieve objectives and that management communicate that information throughout the entity.[59] Moreover, the U.S. Constitution and federal case law require the military services to provide applicable procedural due process protections in their honor and conduct processes.[60] The academies’ honor and conduct system guidance emphasize the importance of applying standards fairly. However, the due process protections available for honor and conduct proceedings is not always clear in guidance. Assessing the existing guidance and updating it to ensure that it fully and clearly reflects and communicates the protections available to accused students, would help ensure that students are informed of their rights.

|

Use of Attorneys During Hearings Honor and conduct proceedings at all academies are administrative proceedings, similar to nonjudicial punishment under Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. For both nonjudicial punishment and some, but not all, of these academy proceedings, the accused is allowed to have a spokesperson who speaks on their behalf. At nonjudicial punishment proceedings, this spokesperson can be the accused’s attorney. Similarly, West Point allows an attorney to accompany the accused for formal misconduct hearings and to serve as the spokesperson for Article 10 proceedings, and the Coast Guard Academy allows counsel for an Executive Board when the board is considering discharge under other than honorable conditions. For other administrative proceedings at the academies, if a spokesperson is permitted, the role is typically filled by a fellow student or an officer advisor. Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107049 |

Officials at some of the academies told us that they believe their honor and conduct systems provide adequate due process protections to students and some also said that guidance contains sufficient information about those processes. Specifically, some academy officials stated they assess the protections provided when legal review of cases is required by policy, such as when disenrollment is recommended, or when their relevant guidance is revised. Officials from West Point and the Naval, Air Force, and Coast Guard Academies noted their relevant guidance was updated within the last several years. Merchant Marine officials acknowledged some areas of their guidance were not clear and that they planned to address them in the next update, though they did not provide a date for when the next update would occur.

We recognize that administrative proceedings, such as those used to adjudicate honor and conduct violations, do not necessarily require that the accused be afforded all 12 due process protections. However, without guidance that clearly articulates the intended range of due process protections available—such as those that academy officials told us were available but not documented—students accused of honor and conduct violations may not be fully informed of their rights and thus be unintentionally limited in their ability to mount an effective defense when engaging with processes that could impede their ability to graduate and serve as officers. Furthermore, clear guidance may also help to ensure that students have a favorable perception of the honor and conduct systems and that systems are implemented in a fair and just manner.

The Academies Collect Some Data but Two Issues Limit Visibility Over Honor and Conduct Systems

The Honor and Conduct Data That Academies Collect Are Not Complete

The academies collect and maintain some data related to honor and conduct offenses and their associated proceedings, but these data are incomplete.[61] Specifically, the academies collected and maintained data on some, but not all, of the stages of their honor and conduct systems for academic years 2018-2019 through 2023-2024. As noted previously, the honor and conduct systems at each academy typically involve five stages: (1) reporting a suspected violation, (2) investigating the claim, (3) adjudicating the alleged offense, (4) determining appropriate punishment for confirmed offenses, and (5) providing certain appeal rights. Below we provide an overview of our findings and, in appendix II, we provide more detailed results of our analysis of honor and conduct data.[62]

Honor Data

Each academy collects and maintains data on reported honor offenses and their adjudication, but none collect data consistently across the remaining three stages of the honor system, including investigations, disciplinary actions resulting from honor cases, and appeals.

Investigations. The investigative stage produces key information, such as documentary and testimonial evidence, that is used during honor system proceedings. The Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academies collect some data on investigations of honor offenses, such as who completes the investigation or the date it was completed.[63] However, the other three academies (West Point, Naval, and Air Force) do not.

Discipline. All five academies have the option to impose administrative sanctions, honor remediation or probation, or disenrollment as disciplinary measures for individuals found guilty of honor offenses. Data on the type of discipline that academies impose is important for a variety of reasons, such as identifying potential disparities in how sanctions are applied. We found that the academies track honor remediation or probation, but not all academies collect data on instances of imposed administrative sanctions or honor related disenrollments. Specifically, we found that two academies (Air Force and Merchant Marine) do not collect data on administrative sanctions, and two academies (Air Force and Coast Guard) do not collect data on related disenrollments.

Appeals. The appeal stage reflects the final outcome of a case, which may differ from the decision reached during the adjudication phase. However, four academies (West Point, Naval, Air Force, and Coast Guard) do not currently track data on appeals, such as the number of appeals or their results.[64]

Conduct Data

As noted previously, each academy collects and maintains some conduct data, but we found that the data from the 2018-2019 through 2023-2024 academic years were incomplete across all five stages of the system.[65]

Reporting. Data on reported offenses helps provide information about the different conduct issues that may be occurring. However, the degree to which each academy collects data on the types of reported conduct offenses varies. Three academies (Naval, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine) collect data on reports of both major and minor offenses. However, West Point only collects data on reports of minor offenses, and the Air Force Academy collects data on conduct probation, but not on reports of offenses.

West Point and Air Force Academy officials stated that they maintain records for reported offenses outside of their databases, such as in related PDFs or files, but acknowledged they could use current systems to collect and maintain such data. Specifically, West Point’s Office of the Staff Judge Advocate maintains major offense hearing information in its records, but conduct officials acknowledged that collecting information in their conduct database could improve visibility of all reported conduct offenses, provided that doing so does not add a substantial burden to officials’ workloads.

An Air Force Academy official stated that the academy implemented a new database in 2022 to capture derogatory student information, including conduct data.[66] However, this official stated that data in the new system are incomplete because there was no formal requirement to enter data on reported offenses, which the academy anticipated implementing in a forthcoming conduct policy. The academy’s revised policy published in March 2025 requires entering information on probations stemming from a conduct offense in the database but does not require data entry related to reported offenses.[67] Another Air Force Academy official told us that the academy plans to continue maintaining conduct offense data at the squadron level and use data calls as needed and to track disenrollments in Excel workbooks. According to this same official, the Excel workbooks are easier to work with to meet data needs, such as for transferring to briefing slides or for filtering the data.

Investigations. As noted previously, the investigative stage produces important evidence that is used in conduct proceedings. The Naval and Coast Guard Academies collect data on investigations of conduct offenses, such as who completes the investigation. However, three academies (West Point, Air Force, and Merchant Marine) do not collect data related to this stage.

Adjudications. The adjudications stage includes reviewing evidence and determining guilt. The adjudicating authority or hearing type varies based on offense severity, among other factors. The Naval and Coast Guard Academies collect data on adjudication, and West Point collects it for the minor offense data it maintains.[68] However, two academies (Air Force and Merchant Marine) do not collect data on the adjudication method, such as the hearing type or who adjudicated the offense.

Discipline. All academies may impose administrative sanctions, use conduct remediation or probation, or initiate disenrollment for students found guilty of a conduct offense, and the academies collect some data on these actions at varying levels. However, the academies do not consistently collect data on the various disciplinary measures they use. Specifically, the Air Force does not collect data on the use of administrative sanctions, and two academies (West Point and Merchant Marine) do not collect data on the use of remediation for conduct offenses. We also found that no academies collect data on disenrollments resulting from a conduct offense.

Appeal. As noted previously, an appeal may result in an outcome that differs from the adjudicated decision. However, none of the academies collect data on appeals related to a conduct offense.[69]

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should use quality information—that is, information from reliable data that is current, complete, accurate, accessible, and timely—to achieve the entity’s objectives. In doing so, management identifies the information requirements needed to achieve the entity’s objectives and address related risks, and such requirements consider the expectations of internal and external users.[70] Further, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 included requirements related to collecting data across all stages of the military justice system to facilitate case management, analysis, and decision-making.[71] For example, the statute directed the Secretary of Defense to collect data on substantive offenses and procedural matters for pretrial, trial, posttrial, and appellate processes, among other things. While academy honor and conduct systems are distinct from the military justice system and are administrative in nature, they maintain numerous similarities to processes under the UCMJ—such as nonjudicial punishment. Furthermore, offenses by students that are not pursued for prosecution under the UCMJ may be eventually adjudicated under the academy conduct system.

The academies strive to ensure that all honor and conduct offenses are fairly adjudicated, and officials at each academy told us that they rely on the data collected to manage their respective honor and conduct systems. Some noted they use it to respond to external inquiries, such as from Congress or DOD. However, the academies cannot be sure that they are meeting their stated objectives or able to thoroughly respond to requests for information because they have not identified their own comprehensive set of data collection requirements for all stages of honor and conduct systems or documented these requirements in their guidance.[72]

Officials from each academy told us that they collect the data necessary to meet their needs, and some officials stated data collected may adjust as their leaderships’ needs change. Officials also told us that they do not believe that documenting data collection requirements in guidance would improve their ability to oversee their respective honor and conduct systems, as they believe they are able to effectively manage both systems with the data that they currently collect. Naval Academy officials also questioned the utility of expending resources to update guidance with a more comprehensive list of data collection requirements due to the relatively small number of students who are adjudicated under the honor and conduct systems.

While the likelihood of students being adjudicated for an honor or conduct offense may be low, the demand on academy resources, possible repercussions, and the overall experience for students involved in the process can be considerable. By systematically identifying and updating their data needs across all stages, the service academies will be better able to leverage information to pinpoint opportunities to enhance efficiency and address challenges faced by students who become involved in the process, such as the length of investigations or adjudications. Further, by establishing complete and consistent data collection requirements, and documenting them in guidance, the academies will be better positioned to fairly adjudicate all honor and conduct offenses, respond thoroughly to requests for information, and identify related risks across all stages of the systems.

The Academies Are Unable to Readily Access Data

We found that visibility over honor and conduct systems is further constrained by the challenges officials at four academies described in accessing relevant data. West Point officials did not identify any challenges in accessing relevant data, but officials from the remaining academies did. Specifically,

· Naval Academy officials told us that the dated nature of their database, which was created in the 1990s, presents challenges that lead to a less user-friendly experience and hinders their ability to access and analyze conduct data in a timely manner. For example, an official told us they track the number of conduct offenses and their level, such as major, but could not access further detail on the offenses such as the specific offense or demographic data.

· Air Force Academy officials told us that their use of a spreadsheet to track honor-related cases limits their ability to maintain visibility over required tasks related to processing an honor case and showing at what stage it is in.

· Coast Guard Academy officials stated that they do not have immediate access to certain honor and conduct data, such as historical records, necessary for tracking related offenses. Specifically, officials told us that data requests must be submitted through another Academy office, which, despite being supportive, has many competing priorities that delay the completion of these requests.

· Merchant Marine Academy officials told us that they also cannot access historical conduct data from their database. Rather, they must rely on a contractor who manages the database, leading to delays in processing requests. Further, these officials said that the dated nature of their database, at 25 years old, hinders their ability to query the data directly.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should use quality information—that is information from reliable data that is current, complete, accurate, accessible, and timely—to achieve the entity’s objectives. In doing so, management obtains relevant data from reliable sources and on a timely basis and processes it into quality information within the entity’s information system.[73]

While Naval, Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine Academy officials may eventually access the data needed, they cannot do so in a timely manner. Because the academies have not yet addressed the challenges that limit officials’ timely access to the information, they cannot readily access needed data. Officials at all four academies acknowledged these limitations and described steps they are taking to address these challenges. However, the academies are at varying stages of completion in addressing such challenges. Specifically,