MISSILE WARNING SATELLITES

Space Development Agency Should Be More Realistic and Transparent About Risks to Capability Delivery

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

|

Revised 02/02/2026 to replace the word “mission” with “missile” in both instances in Recommendation 3 on page 47. |

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Jon Ludwigson at LudwigsonJ@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Space Development Agency (SDA) is developing space- and ground-based systems to detect and track potential missile threats in low Earth orbit. SDA aims to rapidly deliver capability and frequently update technology by delivering multiple satellites in phases, which it calls tranches, planned for contract award every 2 years. Each tranche needs to be replaced roughly 5 years after launch.

However, SDA is at risk of being unable to deliver capability as quickly as planned. For example, SDA is overestimating the technology readiness of some critical elements it plans to use. This includes the spacecraft, which must be modified for the mission. As a result, contractors have performed additional unplanned work, which has added to already delayed schedules.

Additionally, SDA’s requirements process is not transparent to users. For example, SDA is not sufficiently collaborating with combatant commands, which report having insufficient insight into how SDA defines requirements and when, or whether, SDA will deliver planned capabilities. Consequently, SDA is at risk of delivering satellites that do not meet warfighter needs.

SDA reports achieving early milestones, but these achievements do not reflect schedule risks. SDA has continued to award new tranche contracts every 2 years irrespective of satellite performance. SDA relies on contractor schedules for each tranche but has not developed an overall or architecture-level schedule. Using an architecture-level schedule to monitor schedule risks would better position SDA and stakeholders to understand earlier how schedule changes affect SDA’s progress in delivering capabilities.

In addition, the Department of Defense (DOD) does not know the life-cycle cost to deliver missile warning and tracking capabilities because it has not created a reliable cost estimate. SDA required limited cost data from contractors for tranches 1 and 2. Requiring more complete and frequent cost data moving forward would enable DOD to develop reliable cost estimates for future tranches.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD is developing large constellations of satellites for missions that include missile warning and tracking. SDA’s effort—known as the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture—plans to have at least 300-500 satellites in low Earth orbit. This constellation is expected to cost nearly $35 billion through fiscal year 2029. Given the design life of the satellites, each one must be replaced about every 5 years.

A Senate report contains a provision for GAO to assess DOD’s efforts to develop these capabilities. GAO’s report (1) describes SDA’s efforts to develop and deliver missile warning and tracking capabilities; (2) identifies risks SDA faces delivering these planned capabilities; (3) assesses aspects of SDA’s requirements process; and (4) evaluates the extent to which SDA is meeting schedule milestones and cost estimates.

GAO reviewed relevant program, DOD, and contractor documents; assessed SDA’s schedule and cost estimates against best practices; conducted site visits to a ground operations center, the Boulder Ground Innovation Facility, which analyzes satellite data, and seven contractor sites; and interviewed SDA and DOD officials and three combatant commands.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that SDA should assess the technology readiness of new critical technologies; collaborate with warfighters on requirements and deferred capabilities; develop an architecture-level schedule and a reliable, data-informed cost estimate; and include requirements for cost data in new contract awards. DOD concurred with five of the recommendations and partially concurred with one recommendation.

Abbreviations

|

CAPE |

Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation |

|

DCMA |

Defense Contract Management Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

GEO |

geosynchronous Earth orbit |

|

HEO |

highly elliptical orbit |

|

LEO |

low Earth orbit |

|

MEO |

medium Earth orbit |

|

MT |

missile tracking |

|

MVC |

minimum viable capability |

|

MVP |

minimum viable product |

|

MW |

missile warning |

|

NEBULA |

Network Established Beyond the Upper Limits of the Atmosphere |

|

Next Gen OPIR |

Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared |

|

NOVA |

NEBULA Operations – Vendor Architecture |

|

OCT |

optical communications terminal |

|

OPIR |

Overhead Persistent Infrared |

|

PWSA |

Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture |

|

RTS |

Realtime Transfer Service |

|

SBIRS |

Space Based Infrared System |

|

SDA |

Space Development Agency |

|

SUPERNOVA |

SDA Unified Planning Environment and Resources for NEBULA Operations – Vendor Agnostic |

|

TRL |

technology readiness level |

|

T(#) |

tranche number |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 28, 2026

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Space Development Agency (SDA) is developing a new space-based architecture comprised of a large constellation of at least 300-500 satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) to detect and track potential missile threats.[1] This system will complement other space systems currently providing this capability. SDA is developing this new system in part in response to peer and near-peer competitors that are designing strategic and tactical hypersonic weapons that are not easily detected, identified, or tracked by current space-based missile warning systems. DOD has committed nearly $11 billion to this effort—known as the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA)—since 2020 and plans to spend a total of nearly $35 billion through fiscal year 2029. PWSA is intended to provide space surveillance and communications for persistent, timely, global awareness that is designed to operate in an increasingly contested space environment.[2] Last year we reported on challenges facing SDA’s development of the space-based laser communications technology that is key to enabling PWSA to transmit data among other satellites in the constellation and to Earth.[3]

This work stems from a provision in the Senate Report 117-39 accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 for us to report on DOD’s efforts to deploy an Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) architecture.[4] The OPIR architecture includes space systems using infrared sensors from space to support U.S defense and intelligence communities. These sensors provide essential launch detection, missile tracking, and reconnaissance data to mitigate, predict, track, and respond to a variety of threats. SDA, established in 2019, is charged with developing national security space systems. DOD is planning that PWSA missile warning satellites in LEO, referred to as the Tracking Layer, will complement the Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next Gen OPIR) satellites for critical missile warning/missile tracking (MW/MT) functions, among other things. We (1) describe SDA’s efforts to develop and deliver MW/MT capabilities; (2) assess risks SDA faces in delivering planned MW/MT capabilities; (3) assess aspects of SDA’s requirements process; and (4) evaluate the extent to which SDA is meeting schedule milestones and cost estimates in developing its MW/MT capabilities.

To describe SDA’s plans to deliver MW/MT capabilities, we reviewed relevant documentation such as SDA’s acquisition strategies, concept of operations, contracts,[5] and SDA briefings.[6] To assess the risks SDA faces in delivering planned MW/MT capabilities, we reviewed program and contractor risk and opportunity documents, planned supply chain incentives, and ground segment program documentation. To assess SDA’s requirements process, we reviewed acquisition documents, such as acquisition decision memorandums, DOD and SDA briefings, and SDA’s Warfighter Council Charter.[7] We assessed SDA’s requirements process against our leading practices for product development.[8] To evaluate the extent to which SDA is meeting schedule milestones and cost targets in developing its MW/MT capabilities, we reviewed program and contractor schedule documentation, as well as DOD and Air Force cost estimates. We compared originally planned schedule milestones with actual dates and assessed DOD PWSA cost estimates and schedules using criteria from our schedule and cost estimating guides.[9]

To support all objectives, we interviewed officials from SDA; three combatant commands (U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Space Command, and U.S. Strategic Command); the Department of the Air Force; the Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE); DOD’s office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation; and the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Research and Engineering office of Developmental Test and Evaluation. We visited the Boulder Ground Innovation Facility, which is a government-owned data analysis and processing facility; a PWSA ground operations center; and seven contractor sites to understand program progress and planned operations.

See appendix I for a more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Legacy Missile Warning/Missile Tracking Satellites and Systems

Traditional missile threats can be detected and tracked because they are launched using powerful rocket boosters and follow easy to predict ballistic trajectories. Infrared sensors detect heat from missile and booster plumes against Earth’s background. According to DOD, MW/MT is a no-fail mission, meaning that the systems used to detect and track missiles must be designed and operated to ensure uninterrupted coverage of potential threats. The systems that support this mission are tasked with providing timely, continuous, and unambiguous warning and assessment information on missile threats.

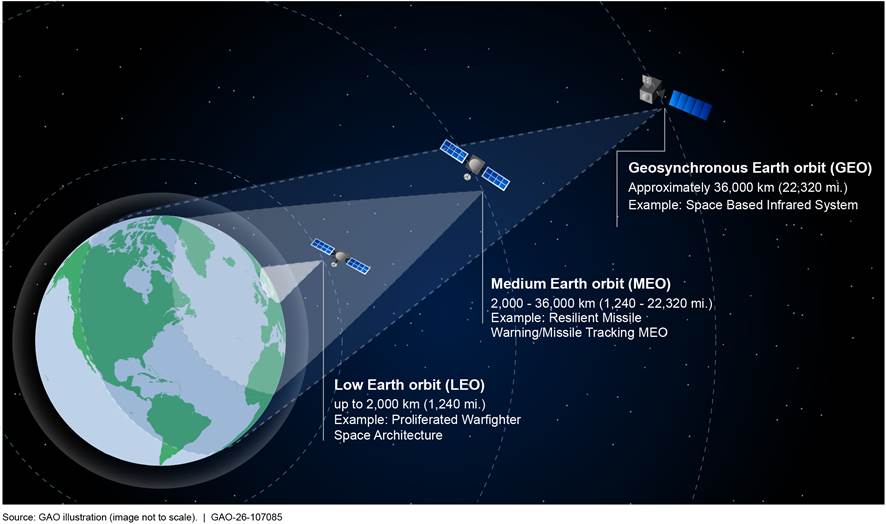

DOD has relied on satellites and associated ground systems for its early missile warning capabilities to detect ballistic and other missile launches and track missile trajectories. In 1970, DOD launched the first Defense Support Program satellites, which use infrared sensors. In the mid-1990s, DOD developed the Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) to replace and provide significantly more robust data than the Defense Support Program. SBIRS will be followed by the Next Gen OPIR system, designed as an upgraded replacement for SBIRS, with sensors that are expected to have even greater sensitivity than SBIRS sensors. While providing some enhanced capabilities, such as greater sensitivity, the Next Gen OPIR system is built around an architecture similar to existing systems. Each of these systems was designed to operate in geosynchronous Earth orbits (GEO), located about 22,000 miles above Earth, with each satellite maintaining constant observation of a specific area of the globe and collectively monitoring the entire planet.[10]

In recent years, DOD has identified emerging threats that these systems may be unable to effectively warn or defend against. For example, Russia and China have successfully demonstrated hypersonic missile capabilities.[11] In addition to new missile threats posed by potential adversaries, DOD has also publicly acknowledged emerging threats to our space assets. For example, DOD reported that China is developing additional counterspace capabilities including directed energy weapons, electronic warfare, and other anti-satellite weapons. DOD officials have also stated that Russia is reinvigorating its space and counterspace capabilities, and that Russia considers space a warfighting domain. U.S. missile warning satellites currently operating in GEO may be particularly vulnerable to these emerging threats because there are relatively few of them—making them high-value targets—and their location above Earth is effectively stationary and predictable. See table 1 for satellite program quantities in current and planned systems.

|

Satellite constellation |

Initial launch year |

Orbit |

Number of satellites |

|

Defense Support Program |

1970 |

Geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) |

20+ |

|

Space Based Infrared System |

2011 |

GEO, Highly elliptical orbit (HEO)b |

10c |

|

Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared |

2026a |

GEO, HEO |

4 |

|

Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture Tracking and Transport Layers |

2025 |

Low Earth orbit |

616d (Tranches 1-3) |

|

Resilient Missile Warning/Missile Tracking – Medium Earth Orbit |

2026a |

Medium Earth orbit |

24-36d |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense information. | GAO‑26‑107085

aPlanned initial launch year.

bHEO satellites, which linger over a designated area of Earth, can provide for coverage of polar regions.

cSpace Based Infrared System includes both satellites and sensors on host satellites.

dEstimated quantity to achieve full capability.

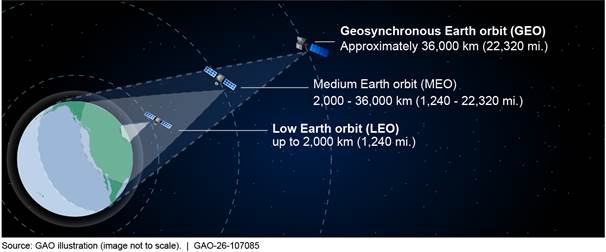

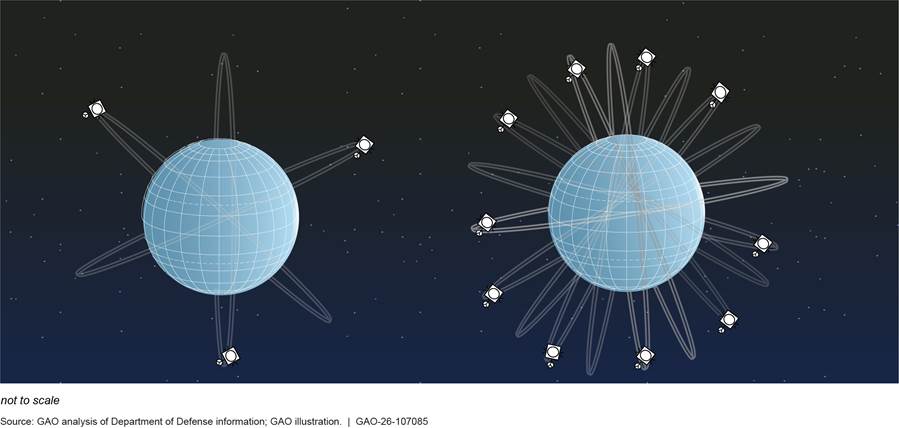

In 2019, DOD established SDA and provided that the head of the agency should, among other things, develop a proliferated space-based architecture in LEO to support critical sensing, tracking, and data transport missions.[12] To meet this goal, DOD initiated efforts to develop a large constellation of satellites in LEO, and it plans to replenish each tranche every 2 years in perpetuity, along with associated ground systems.[13] As the satellites approach the end of their life, SDA will deorbit them. Some DOD officials say having a greater number of satellites performing MW/MT in LEO will result in greater resiliency for the constellation as a whole and the capability it provides. For example, if one satellite in a proliferated constellation is damaged—whether intentionally or by natural environmental effects—the constellation’s capability is degraded by a smaller margin than if the entire constellation was made up of only a handful of satellites (non-proliferated). Figure 1 illustrates the relative altitudes of low, medium, and geosynchronous orbits.

Figure 1: Notional Depiction of Satellites in Low Earth Orbit, Medium Earth Orbit, and Geosynchronous Earth Orbit

SDA has aimed to prioritize more rapid delivery of these capabilities to the warfighter and established its agency motto as “semper citius,” which is Latin for always faster. We and others have highlighted the historically slow pace of satellite system and other acquisitions. In particular, in 2025, we reported that the average weapon system program took about 12 years to deliver to the warfighter.[14] In recent years, DOD has highlighted the urgent need to speed up time frames for developing and delivering weapon systems and related capabilities, and in particular, noted that SDA’s rapid approach could be a model for how to reform DOD weapon system acquisitions.[15] An executive order issued in April 2025 identified the slow pace of weapon systems acquisition and the need to speed up acquisitions as the basis for a review of acquisition policies across DOD.[16]

Conducting MW/MT From LEO

With hypersonic missiles and other potential adversarial threats emerging, DOD is prioritizing development of missile warning and tracking capabilities in LEO and medium Earth orbit (MEO), with constellations consisting of large numbers of low-value satellites. Because satellites in LEO are much closer to Earth than those in GEO, many more satellites are needed in a LEO-based constellation to achieve the same coverage as a single one in GEO (see fig. 1).[17] Satellites in LEO are also traveling much faster relative to Earth’s surface. Therefore, satellites in LEO can only observe a small section of Earth’s surface for a short time—only about 10 minutes. This makes constellation management considerably more complicated if constant global coverage is required, as it is for MW/MT. In contrast, satellites in GEO can see a larger portion of Earth’s surface and are geosynchronous, meaning when observed from the earth these satellites appear to stay in the same location in the sky because they orbit at the same rate and direction of Earth’s rotation.

We previously reported on both the advantages and challenges of meeting warfighter needs through a large constellation of satellites in LEO.[18] Table 2 highlights some of the advantages and challenges of operating in LEO versus the higher orbits, like GEO, where DOD has traditionally conducted the missile warning mission.

Table 2: Advantages and Challenges of Conducting Missile Warning and Missile Tracking in Low Earth Orbit

|

Advantages |

|

Smaller, lower-cost satellites |

|

More frequent opportunities to update technology |

|

Potential for improved tracking of hypersonic missiles |

|

Ability to adapt to changes in satellite constellation |

|

Challenges |

|

More satellites are needed to achieve full coverage of Earth’s surface |

|

More frequent replacement and shorter satellite lifespan |

|

Separating target signal from background clutter is more complex due to high speed of satellite relative to Earth |

|

Requires high data transmission rates due to limited time satellite is in view of a given ground station |

Source: GAO summary of Department of Defense, Space Development Agency and Congressional Budget Office information. | GAO‑26‑107085

PWSA-Enabling Technologies and Processes

According to SDA planning documents, the PWSA Tracking Layer’s primary mission is missile warning, and its highest priority is tracking missile threats. SDA is acquiring both Tracking and Transport Layer satellites in groups, or tranches, every 2 years, beginning with a demonstration tranche, called Tranche 0 (T0). T0 began launching in April 2023. SDA plans for the Tracking Layer satellites to collect infrared emissions from missile launches and, for hypersonic threats, infrared emissions produced as the object heats up due to its high speed through the atmosphere. SDA plans for tracking satellites to transmit data on the path of the object—referred to as a missile track—down to a ground processing facility for further action. SDA is also developing its Transport Layer to transmit data throughout the constellation. The tracking satellites can transmit the missile track to the ground directly or through PWSA Tracking and Transport satellites.

SDA is developing tracking satellites comprised of a spacecraft—referred to as a bus—plus other components such as infrared sensors, on-board mission data processors, and communication payloads, together with a ground segment to manage the constellation and receive and process track data to send to the wider DOD and intelligence community. SDA plans to field tracking satellites in multiple orbital planes. Tracking satellites in the same plane will move together like train cars moving along a track. An orbit is a regular, repeating path that one object in space takes around another one. Figure 2 depicts a notional view of multiple orbital planes.

Buses. A spacecraft, or bus, houses the equipment that enables the payload to perform its mission.[19] Specific features of the bus can determine the lifespan of a satellite, such as the extent to which it is hardened to endure some aspects of space flight such as radiation, how much propellant it carries, and power. Other features of the bus can affect its accuracy in controlling the position and alignment of its payload. This is important because some payloads, such as laser communications technologies, require more accuracy than others in pointing to a specific location to achieve their missions. SDA’s acquisition strategy relies on contractors leveraging commercial products, like buses, to reduce development timelines and support its 2-year tranche award and replenishment cycle. Private companies develop these buses and qualify their use in space.

Infrared sensors. Infrared sensors are devices used to detect and visualize objects or targets based on the infrared radiation they emit. A key element of an infrared sensor is a focal plane array, which converts incoming infrared radiation into electrical signals and creates an image. Focal plane arrays are manufactured in a variety sizes or formats, based on the number of pixels. According to one subcontractor manufacturing focal plane arrays for Tracking contractors, the infrared sensors needed for MW/MT require high sensitivity, large format infrared focal plane arrays. In its first tranche intended to deliver operational capabilities, Tranche 1 (T1)—which followed its demonstration T0—SDA is planning to field two types of tracking satellites: missile tracking, which carry wide field of view sensors, and missile defense, which carry medium field of view sensors.[20] Because they can see a larger portion of Earth’s surface, wide field of view sensors perform MW/MT of conventional and advanced missile threats, including hypersonic systems, without needing an operator prompting the satellites to look for the event (known as cueing). Medium field of view sensors employ a smaller field of view to enable higher accuracy tracking, so these sensors are cued to observe specific locations of interest.

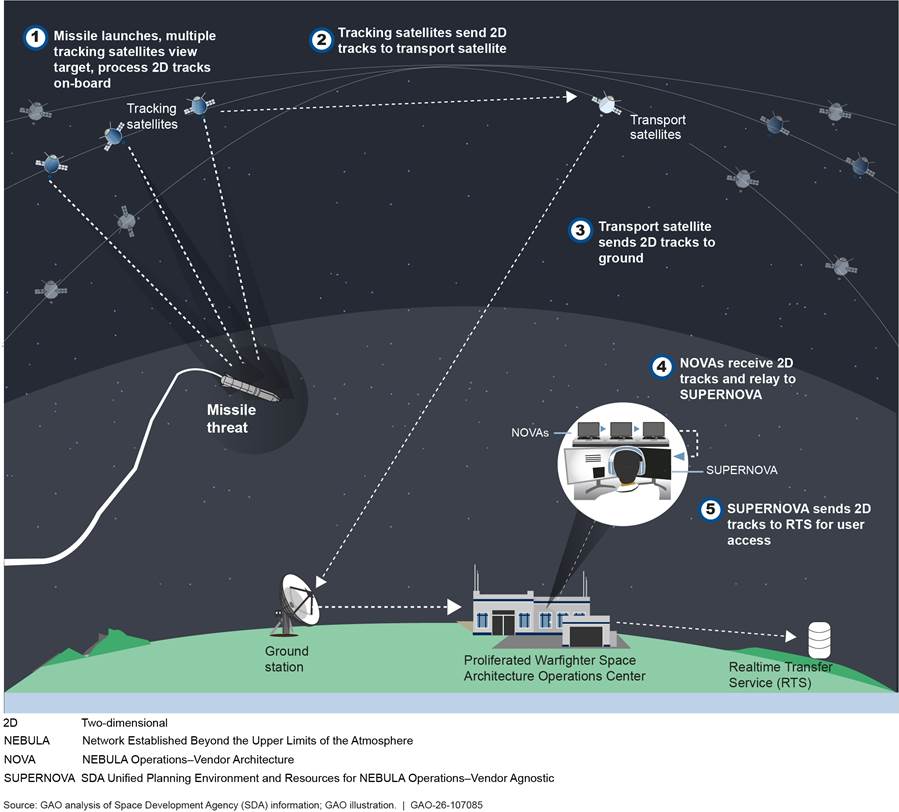

On-board mission data processor. SDA plans for PWSA tracking satellites to perform mission data processing on orbit. The on-board mission data processor performs a series of steps on the raw image data collected by the infrared payload that enables it to detect potential targets, or missiles. From these detections the mission data processor forms 2-dimensional tracks, which include the missile’s position, its motion through the field of view, and its brightness. The mission data processor will then convert the track into a standard message format that is transmitted to the ground.

Communication payloads. To move data to the ground quickly and efficiently, PWSA will rely on laser communications. Sometimes referred to as optical communications, laser communications technology uses laser beams to transmit data between satellites and to Earth. We previously reported that SDA identified laser communications technology as central to the success of its overall PWSA architecture because only laser communications can provide the data speed and throughput that the missile tracking and data transport missions require.[21] Its advantages include the ability to transmit data at much higher rates through significantly narrower transmission beams, which enables more secure communication between users. In addition to laser communications technology, SDA plans to incorporate communications technologies such as radio frequency communication. However, SDA officials have said that, although these complementary communications technologies will be helpful, the laser communications must work across a network of hundreds of satellites to achieve planned mission capabilities.

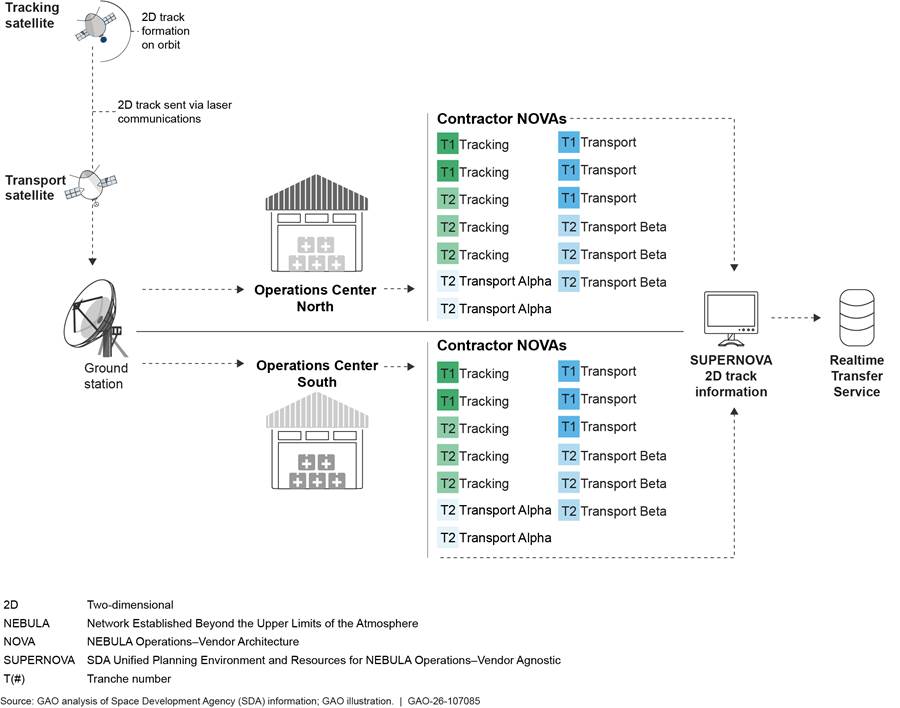

Ground segment. SDA plans for each tracking satellite contractor to deliver, integrate, and operate its own ground processing system, called a Network Established Beyond the Upper Limits of the Atmosphere (NEBULA) Operations – Vendor Architecture. These systems are referred to as NOVAs and will be integrated at each of the two SDA ground operations centers for the life of each contractor’s respective satellites.[22] Consisting of both hardware and software, NOVAs will perform numerous enterprise and mission management functions for each contractor’s satellites, such as monitoring satellite health and planning satellite maneuvers.[23] SDA’s plan calls for each of its two government owned, contractor operated ground operations centers to have a unified ground system, or SUPERNOVA.[24]

When operational, NOVAs will receive two-dimensional tracks from the tracking satellites and relay them to the SUPERNOVA. The SUPERNOVA is developed by the ground segment contractor. The two-dimensional track is then sent via the Realtime Transfer Service as a message to users including military and intelligence leadership.[25] Additionally, the SUPERNOVA will take the two-dimensional tracks and fuse them into three-dimensional tracks in a standard message format. Sensors from multiple satellites must capture images of the same object from different angles to develop three-dimensional tracks critical to missile tracking. Each of these steps is required to happen in near real time to provide timely information to leadership to assess threats and make timely decisions on how to respond. According to SDA, T1 establishes the PWSA ground and operations baseline, or the foundation upon which SDA plans to add capabilities in future tranches. To reduce risk, SDA is taking an incremental approach to delivering these ground operations.

Transport Layer. SDA’s PWSA Transport Layer satellites are intended to work with Tracking Layer satellites to transmit data from satellite-to-satellite using laser communications. The Transport Layer will use both laser and radio frequency communications to transmit data from satellite-to-ground and satellite-to-aircraft. The PWSA Tracking Layer needs functional data transport satellites to fully perform the MW/MT mission from LEO.

In February 2025, we reported that SDA awarded contracts for the larger and more complex T1 and Tranche 2 (T2) before it had demonstrated intended laser communications capabilities in T0. This means SDA does not yet fully understand what will and will not work from its T0 demonstration. Our report made several recommendations, including that SDA should demonstrate the minimum viable product on orbit and incorporate lessons learned and corrective updates in current and future tranches before proceeding further with launch decisions.[26] DOD concurred but noted that it believes SDA is already implementing our recommendations. DOD’s response to our recommendation that SDA should demonstrate the minimum viable product for laser communications capability in T0, before proceeding with investments in T1, was that SDA met the minimum viable product for T0. However, our view is that SDA revised downward its minimum viable product, which is at odds with leading practices for iterative development. We continue to believe that SDA would benefit from taking steps aimed at implementing our recommendations.

See figure 3 for a step-by-step depiction of the PWSA missile tracking process.

Figure 3: Notional Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture Missile Warning/Missile Tracking Process

SDA Plans to Deliver Missile Warning/Missile Tracking Capabilities Using Its Own Incremental, System of Systems Approach

SDA Is Developing and Plans to Deliver MW/MT Capabilities Incrementally Using Its Own Requirements Process and Various Contracting Methods

PWSA is intended to operate as a system of systems, developed incrementally by a diverse set of contractors, that will enable the MW/MT mission.[27] A system of systems approach means that a set of unique systems must work together to achieve overall mission success. In its acquisition strategies, SDA stated that it would invest in nontraditional space companies and leverage commercial technology and innovation. SDA is rapidly developing PWSA capabilities through a series of iterative development efforts, where space and ground-based technologies are developed and built upon through phases. According to planning documents, SDA is pursuing this strategy to deploy capability quickly and to provide frequent opportunities to refresh technology and respond to new threats. SDA plans to award these development efforts, referred to as tranches, every 2 years.

To provide operational capability, tracking and transport satellite tranches are required to be fielded and interoperating. SDA has established a minimum viable capability—the set of requirements SDA has agreed to fulfill within a specific tranche’s timeline—for each satellite tranche. Each tranche is expected to demonstrate increasing capability over the previous tranche, while also connecting with earlier operational tranches to create an interconnected and interoperable architecture. SDA’s planning documents indicate that the Tracking Layer will achieve full warfighting capability in Tranche 3 (T3), for which SDA plans to begin launching satellites in 2029.[28] The documents also show that tracking satellites from the first three operational tranches —T1, T2, and T3—are needed to provide full warfighting capability at the architecture level, along with an operational Transport Layer and ground segment.

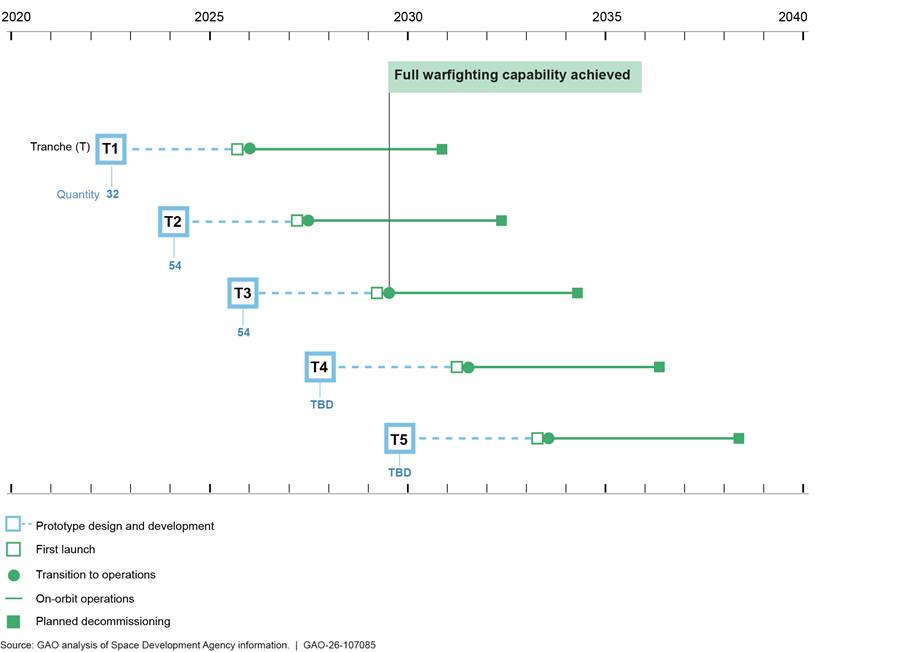

Once the capability is established with T3, to maintain full warfighting capability, SDA has said that it needs to continue to acquire a new tranche every 2 years to replenish the constellation. PWSA tracking satellites have 5-year lifespans. As shown in figure 4, multiple tranches are required to achieve and maintain full warfighting capability.

Figure 4: Replenishment of Tracking Tranche Satellites Is Planned Every 2 Years to Maintain Full Warfighting Capability as of July 2025

Note: After full warfighting capability is initially achieved in T3, the Space Development Agency plans to replenish T1 with T4 satellites. Similar replenishment will take place in subsequent tranches. As of July 2025, satellite quantities per tranche beyond T3 were to be determined (TBD). In December 2025, SDA reported that it awarded contracts for 72 tracking satellites in T3, but we did not obtain the contracts from SDA. As a result, the T3 tracking quantities in this table reflect SDA planning documentation as of July 2025.

SDA’s T0 was the first step in its effort to rapidly develop a MW/MT capability in LEO. The tranche following T0, referred to as T1, is planned to be the first tranche to deliver operationally relevant capabilities to the warfighter. Beginning with T1, SDA is acquiring each tranche for the Tracking and Transport Layers as a separate effort using the middle tier of acquisition rapid prototyping pathway.[29] Middle-tier acquisitions are exempt from acquisition and requirements-development processes defined by DOD Directive 5000.01 and the Manual for the Operation of the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System.[30] As a result, SDA developed its own tailored requirements-setting process, involving submission and refinement of warfighter operational needs statements and assessment and validation by the SDA Warfighter Council. The Warfighter Council meets twice a year and is cochaired by the SDA Director and Vice Chair of Space Operations. Council members include representatives from combatant commands, intelligence agencies, and Joint Chiefs of Staff, among others. The Warfighter Council process is outlined in the SDA Warfighter Council Charter, which we discuss later in this report.

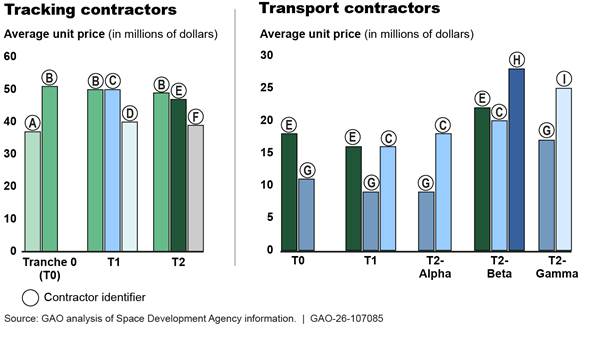

SDA structured its PWSA acquisitions for the tracking and transport layers to attract companies that are not traditional defense contractors through fixed price agreements known as “other transactions.”[31] Each tranche has its own requirements, and SDA conducted a new competition for each tranche. T1 and T2 Tracking and Transport Layer contractors are required to deliver satellites, a contractor-specific ground system for integration into SDA’s ground operations centers, operations and maintenance for the lifetime of the satellites, and launch analysis and integration. Some contractors we spoke to told us that maintaining a business case to compete for tranche awards is predicated on winning early tranches. For example, one contractor told us that if it had not won a T2 contract, it would not have bid again because it would be too far behind the learning curve to successfully field the number of satellites required for T3 and beyond. Another contractor told us it did not intend to bid on any further work because the contractor could not reuse enough of its own designs to satisfy internal profitability. SDA is acquiring the ground segment under a Federal Acquisition Regulation-based cost-type contract.[32] The ground segment contractor for T1 and T2 is responsible for developing, equipping, staffing, operating and maintaining two government-owned operations centers. This contractor is also responsible for acquiring and operating ground stations that serve as entry points for incoming data from the satellites, and leading ground-to-space integration efforts. For T3, SDA officials said that they plan to shift to a ground enterprise solution with new capabilities, and that they expect the T3 ground effort will be even more complex than that of T1 and T2.

Table 3 shows the prime contractors involved in each tranche awarded as of July 2025, as well as the cost and number of planned satellites.[33]

Table 3: Original Number of Satellites by Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) Tranche and Layer as of July 2025

|

PWSA layer |

Tranche 0 |

Tranche 1 |

Tranche 2 |

Approximate total contract value by layer (dollars in millions) |

|

Tracking |

8 |

39 |

54 |

$4,707 |

|

SpaceX |

Northrop Grumman |

Lockheed Martin |

|

|

|

L3Harris |

L3Harris |

Sierra Space |

|

|

|

|

Raytheon |

L3Harris |

|

|

|

Transport |

20 |

126 |

|

$2,074 |

|

Lockheed Marin |

Lockheed Martin |

|

|

|

|

York Space Systems |

Northrop Grumman |

|

|

|

|

|

York Space Systems |

|

|

|

|

Transport (Alpha) |

|

|

100 |

$1,328 |

|

|

|

York Space Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

Northrop Grumman |

|

|

|

Transport (Beta) |

|

|

90 |

$2,064 |

|

|

|

Northrop Grumman |

|

|

|

|

|

Lockheed Martin |

|

|

|

|

|

Rocket Lab |

|

|

|

Transport (Gamma) |

|

|

10 |

$170 |

|

|

|

York Space Systems |

|

|

|

Ground Segment |

|

General Dynamics Missions Systems |

General Dynamics Mission Systems |

$816 |

|

Approximate total cost by tranche (dollars in millions) |

$657 |

$3,999 |

$6,505 |

$11,160 |

|

Total number of planned satellites by tranche |

28 |

165 |

254 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Space Development Agency (SDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107085

Notes: The table includes the original prototyped satellite capabilities in Tranches 0, 1, and 2 as reflected in the original contracts. SDA ultimately launched 27 Tranche 0 satellites and removed seven Raytheon satellites from Tranche 1 (Tracking). Alpha, Beta, and Gamma refer to variants of the satellites introduced in the Tranche 2 Transport Layer. SDA partnered with the Naval Research Laboratory for ground support for Tranche 0 demonstrations. Due to rounding, the approximate total cost does not add up to exactly $11,160 million. In December 2025, SDA reported awarding four contracts for 72 T3 Tracking satellites totaling approximately $3.5 billion.

SDA Completed Some Tranche 0 Demonstrations Planned to Reduce Risk for PWSA

As we reported in February 2025, SDA completed only a portion of what it had planned for T0 related to laser communications capability.[34] We found similarly incomplete capability demonstrations in our review of the Tracking Layer. According to program documents, SDA planned a capstone event for its demonstration tranche that included both transport and tracking satellites. SDA intended T0 to demonstrate the feasibility of the new architecture from a cost, schedule, and scalability perspective. As part of the capstone event, planned for late 2022, SDA intended for the Tracking Layer satellites to detect and initiate tracks on advanced threats like hypersonic weapons, without an external prompt to the satellite to look for an event, known as cueing. The tracking satellites would then transmit the track data through the transport satellite network to the ground.

In July 2024, SDA told us it had reduced its integrated T0 capstone event to a series of capability demonstrations. According to SDA, a capability demonstration is intended to show that a specific capability, such as tracking an object, can be achieved. SDA reduced the T0 capstone event in part due to a longer than expected T0 on-orbit satellite calibration process. SDA had planned to allow the warfighter to provide feedback on capabilities prior to a larger SDA investment in T1 and future tranches, but officials from combatant commands we spoke to told us that they have not been asked to provide feedback on T0 MW/MT demonstrations.[35]

According to an SDA official, SDA demonstrated in T0 the ability to track a short-range ballistic missile throughout its flight and into its terminal phase and then transmit raw data to the ground from space. SDA officials also told us that T0 demonstrations included connecting Link-16, the tactical data link network used by NATO, from space to specific ships and military airplanes. This provides Link-16 users with beyond line-of-sight communications previously limited by the horizon. As reported in our recent work, in December 2024, SDA established the first satellite-to-satellite demonstration of optical links between two of the four T0 contractors.[36] One of the two successful T0 contractors told us that the company made a business decision not to participate in T1 or T2.

SDA Faces Technology, Requirements, and Integration Risks to Delivering Capability

SDA faces many technical challenges to delivering MW/MT capability. Specifically, SDA’s strategy to use commercial products in a novel way has led SDA to overestimate the technology maturity of some PWSA-enabling technologies. Furthermore, both space and ground contractors said that they underestimated the complexity of PWSA development and integration. With limited integrated capability demonstrated in T0, as described above, and complex integration and interoperability requirements remaining, the risk to delivering MW/MT capabilities in T1 is high. However, SDA is taking a new approach in T3, awarding a contract to an integration contractor. Awarding a contract for system engineering and integration support indicates that SDA is applying lessons learned and taking steps in T3 to mitigate integration risk between the satellites and the ground segment.

|

Technology Readiness Levels Technology readiness levels (TRL) are numbered 1 through 9 from least to most mature, based on demonstrations of increasing fidelity and complexity. TRLs are the most common measure for systematically communicating the readiness of new technologies or new applications of existing technologies to be incorporated into a system or program. Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107085 |

SDA Is Overestimating Technology Maturity

SDA is overestimating the technical maturity of some of its critical enabling technologies. Satellite technologies are mature when they have been tested in a relevant space environment (Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 6) and are therefore less likely to encounter failures during test and integration.[37] A TRL is a measurement of maturity for each critical technology element. A key aspect of SDA’s acquisition strategy is to leverage proven commercial products to reduce development timelines. SDA cited the wide variety of proven commercial products available for use in T1 and T2 as its basis for assessing various technologies as mature. However, in some cases, the items SDA identified as commercial items were used in different applications or configurations. Our prior work on space acquisitions found that first time integration of new technology with technology that has already been proven can be difficult.[38]

Tracking Layer satellite contractors have needed to modify previously proven components, such as their buses and infrared sensors, or to mature software to integrate with other components to perform MW/MT capabilities in LEO. Specifically, commercial buses and associated flight software provided by T1 contractors have required significant, unplanned development and upgrades to meet SDA requirements.

For example, one T1 tracking satellite contractor identified the bus’s flight software as having a technology readiness level of 4 at the start of the program. The contractor planned to mature the software to TRL 6 by its critical design review, but this did not occur.[39] As a result, the contractor had to perform additional, unplanned work to mature the flight software. Using immature technologies and modifying proven technologies adds risk to the program until such time that the technologies can be tested in a relevant environment.

For definitions of technology readiness levels 1-9, see table 4 below.

|

TRL |

Definition |

|

1 |

Basic principles observed and reported |

|

2 |

Technology concept and/or application formulated |

|

3 |

Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof of concept |

|

4 |

Component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment |

|

5 |

Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment |

|

6 |

System/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment |

|

7 |

System prototype demonstration in an operational environment |

|

8 |

Actual system completed and qualified through test and demonstration |

|

9 |

Actual system proven through successful mission operations |

Source: GAO analysis of National Aeronautics and Space Administration data. | GAO‑26‑107085

Further, SDA told us it relies on informal contractor technology readiness assessments to determine technology maturity. In SDA’s T1 and T2 Tracking Layer documentation from August 2024, SDA asserted that prior to T1 and T2 initiation, tracking satellites had demonstrated TRL 6 and 7, respectively. However, this was not accurate. L3Harris officials told us that the company is still in the process of demonstrating its T0 satellite design on orbit in LEO, and neither Sierra Space, Northrop Grumman, nor Lockheed Martin demonstrated tracking satellites on orbit in LEO prior to T1 or T2 initiation. However, SDA states that the T1 Tracking Layer is expected to have achieved TRL 9 following a successful T1 capstone event because the Tracking Layer will have been proven in an operational environment.[40] Lastly, in a separate program self-assessment provided to us from July 2024, SDA assessed, based on contractor information, current technology readiness is TRL 7 for T1 satellites and TRL 8 for T2 satellites, despite T2 satellites being further behind in design and development.

SDA has not conducted a sufficient review of the maturity of critical technologies planned for the satellites and therefore lacks assurance that the technology readiness estimates it receives from the contractors are accurate. Further, this means SDA has insufficient information to determine if the contractors’ cost and schedule estimates are reasonable and if additional time or resources are needed to meet planned time frames. According to DOD’s Technology Readiness Assessment Guidebook, when the prototyping solution involves new technology insertion or technology refreshment for which technology maturity has not been assessed, a tailored assessment should focus on whether the technology is sufficiently mature to be developed and fielded within the 5-year prototyping time frame.[41]

Further, SDA’s approach to technology readiness assessment limits the insights it obtains from these examinations. In documentation submitted to DOD, SDA identifies the tracking satellites, as a unit, as a single critical technology element.[42] A critical technology element is a new or novel technology on which a program depends to successfully meet an operational threshold. It can be hardware, software, or a process critical to the performance of a larger system. Because SDA identified the entire satellite as the critical technology element and then assesses technologies at the satellite-level, its assessment lacks detail to provide insight into the maturity of enabling technologies. As described above, PWSA tracking satellites are comprised of multiple critical technologies that are in various stages of maturity—infrared payloads, optical communications terminals, flight software, and others—that are required for the satellite to perform the mission.

Because SDA is assessing technology maturity at the satellite-level, it is under-identifying critical technology elements. Under-identifying critical technology elements can result in an underrepresentation of the integration needs, which is a significant cause of system failure.[43] By conducting and documenting a tailored technology readiness assessment of critical technology elements, SDA can ensure realistic development schedules that meet planned delivery dates.

As noted above, SDA is planning on developing and fielding prototypes on a compressed timeline, every 2 years, with each tranche expected to demonstrate increasing capability over the previous tranche. SDA’s system-level assessment of T2’s technology readiness may lead to decision-makers being overconfident in the readiness of PWSA’s operational capability and ability to deliver capability on schedule.

Contractors Underestimated the Complexity of Requirements

The ground contractor and one of the PWSA space contractors reported underestimating the complexity of requirements to be satisfied in T1, adding risk to delivering MW/MT capability on schedule. Following initial T1 Tracking contract awards to L3Harris and Northrop Grumman, SDA awarded Raytheon an additional contract to develop and launch seven satellites in a fifth orbital plane to bolster T1 tracking coverage. However, the contract was reduced in value and scope at Raytheon’s request. Specifically, in early 2023, SDA told us that they received an additional $250 million to provide additional coverage in the Indo-Pacific region. SDA awarded a contract to Raytheon for the additional orbital plane to enhance the ability of the system to cover the Indo-Pacific, in February 2023, but by the end of the year, Raytheon submitted a request to terminate the contract.

Raytheon representatives told us that the company had underestimated the complexity of the system development to include unexpected operations, like when a satellite loses its network connection and must perform autonomously without the ground system. This underestimation resulted in significantly more software development than was originally planned, which Raytheon officials did not believe they could complete while maintaining the aggressive launch schedule. Raytheon representatives said that they initially understood the T1 Tracking Layer’s detect and track mission but did not account for the larger PWSA mission, which includes transmitting data to the ground operations center in near real time with a high rate of availability, among other required activities.

In early 2024, SDA and Raytheon agreed to reduce the scope and value of the contract. This included removing the seven tracking satellites and reducing the overall effort from developing and launching the fifth plane of satellites to conducting two studies related to the Ka-band communications payload and networking and encryption systems. Following this descope, SDA said that the fifth plane was meant to provide additional coverage but was not part of the baseline T1 Tracking capability and that therefore removing it did not affect the planned T1 capability delivery.

The contract for the ground segment has also had to be modified due to underestimated requirements. In August 2024, the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) noted that the T1 ground segment contract, awarded to General Dynamics Mission Systems has been plagued from the start by confusion and misunderstandings about project scope and technical requirements. Further, DCMA reported that SDA expected General Dynamics to lead as the enterprise integrator and manage the overall enterprise architecture, but these requirements were not planned nor explicitly explained in the original proposal. General Dynamics representatives told us that they initially understood the scope of the effort to be integrating the internal components of the SUPERNOVA ground segment and then later integrating the SUPERNOVA with the satellite contractor NOVAs. The representatives told us that, after the contract award, SDA identified additional work that was not included in the initial contract award. This work included integrating all segments inside and outside the ground system after General Dynamics developed interface control documents.

SDA modified the contract in August 2024 to include the additional work. This included the additional integration, managing and tracking schedules with external agencies, developing a tracking data fusion application to support missile track processing, and providing technical assistance to satellite contractors. Additionally, General Dynamics and its subcontractor had planned to follow commercial best practices and rely on significant software reuse. This approach, however, did not comply with DOD cybersecurity requirements. General Dynamics attributed this noncompliance to the software being outdated.

This disconnect regarding the software resulted in a significant unplanned software development effort that must be completed and tested in time to support ground segment delivery and satellite operational acceptance for T1. Contractor data provided by General Dynamics shows it originally estimated $743,000 for this effort. However, in June 2024, the estimated cost to complete this effort had jumped to $6.8 million. To stay on track, General Dynamics added staff to maintain schedule, resulting in increased costs.

Risk Remains High for PWSA’s Complex Integration and Interoperability Requirements

To conduct the MW/MT mission, PWSA, as a system of systems, requires a significant amount of integration and interoperability between the satellites and the ground segment, much of which SDA has yet to demonstrate. These include:

· NOVA-SUPERNOVA integration,

· Laser communications interoperability,

· On-orbit processing, track generation, and sensor performance evaluation, and

· Launch detection and missile tracking in LEO.

As discussed earlier, SDA reduced its original T0 capstone event to a series of lesser capability demonstrations. T0 did mitigate some risks associated with developing, manufacturing, and launching satellites. However, by not completing planned demonstrations, SDA shifted remaining risk to T1—intended to function as the first part of the operational tranche. In addition, SDA added new requirements to T1, such as the NOVA/SUPERNOVA interface, which will need to be designed, developed, and integrated between the satellites and ground segment. As a result, PWSA faces significant integration challenges in T1 that were not addressed in T0.

Figure 5 is a notional depiction of the integration and interoperability required to enable PWSA.

Figure 5: Notional Depiction of Key Ground and Space Integration and Interoperability Points Required to Enable the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture

Note: Each satellite contractor will deliver its own ground system, referred to as a NOVA, which will be integrated at each of the two SDA ground operations centers for the life of each contractor’s respective satellites. SDA’s plan calls for each of its two government-owned, contractor-operated ground operations centers to have a unified ground system, or SUPERNOVA.

NOVA-SUPERNOVA Integration

As the lead integrator for T1, General Dynamics must complete integration and test activities with five distinct satellite contractor-provided ground systems, referred to as NOVAs, to deliver MW/MT capability as the PWSA constellation. Because PWSA is a heterogenous constellation with five contracts for tracking and transport as part of T1, significant effort will be required to integrate each NOVA with the integrated ground system, referred to as SUPERNOVA. NOVA to SUPERNOVA interface development was not part of T0 contracts, and the aggressive schedule, under which the T1 tranche is to launch, leaves little schedule margin to address issues or defects identified during integration and testing.

NOVA-SUPERNOVA integration is an undemonstrated requirement and, according to General Dynamics, building compatible interfaces between the satellite contractors’ NOVAs and its SUPERNOVA ground system has been challenging. An interface is a boundary where two or more systems interact. The five satellite contractors are required to build to General Dynamics’ top-level defined interfaces, but in implementing these top-level interfaces, have faced interoperability challenges between the NOVAs and SUPERNOVA. General Dynamics representatives described the interface issues as if space and ground segment contractors each built railroad tracks, but the tracks were unable to line up and connect.

Delays in NOVA deliveries from the satellite contractors to the ground operations centers have also resulted in compressed schedules for integration and test activities and have required the contractors to provide surge support. This situation has led to increased contract costs for the ground contract. Satellite contractors are also encountering issues with their own integration and test activities, which further pushes out integrated ground testing.

SDA told us recently that ground testing was not complete prior to the T1 first launch in September 2025. This means, for some satellites, SDA accepted the risk of identifying defects while satellites were already on orbit. Late discoveries can result in further schedule delays, rework, retesting, or deferred capability. Integration of all T1 contractor NOVAs with the SUPERNOVA is required for SDA to deliver planned PWSA capabilities.

Laser Communications Interoperability

As we discussed in our February 2025 report, SDA had yet to demonstrate an interoperable mesh network of transport and tracking satellites.[44] A mesh network is a decentralized type of network that automatically reconfigures and adapts itself to route data most efficiently. While SDA asserted that a mesh network demonstration is not required, T0 planning documentation described SDA’s intent to demonstrate a mesh network as a minimum viable product. SDA now plans to deliver an interoperable, laser-based mesh network in T1. PWSA is predicated on tracking and transport satellites being able to maintain laser links and move MW/MT data around the globe and to the ground for additional processing, cueing, and eventual decision-making by U.S. leadership. To meet mission requirements, laser communications must be functioning across the mesh network using both the Tracking and Transport Layers. Because multiple contractors are designing and building optical communications terminals (OCT)—devices used to establish these laser data transmission links—SDA has developed the SDA OCT Standard to increase the likelihood of interoperability among the diverse set of satellites from different contractors.

T0 required testing on the ground to demonstrate OCT interoperability. However, as of July 2025, only two of the four contractors–SpaceX and York—had proven that different satellite contractors can establish a link in space. This achievement is tempered by the fact that SpaceX and York both used the same subcontractor, Tesat, to develop their OCTs.[45] The remaining two satellite contractors in T0 had not demonstrated a space-to-space laser link between their own satellites or satellites built by other contractors at that time. All five T1 Tracking and Transport contracts rely on different OCT subcontractors, none of which had demonstrated the ability to make an optical link on orbit.[46] Undemonstrated OCT designs on orbit put at risk the ability to achieve OCT interoperability in T1, as was the case in T0. Without a fully interoperable constellation, data will not be able to traverse the network through the most efficient pathways, potentially increasing the time it takes to get the data down to the ground. With limited laser links demonstrated on orbit, SDA risks extended calibration timelines and technical challenges during T1 early operations and verification checks with contractors that have yet to prove out their designs.

On-Orbit Processing, Track Generation, and Sensor Performance Evaluation

SDA and the contractors have yet to demonstrate the development of timely, actionable, and accurate two-dimensional tracks on orbit and three-dimensional tracks on the ground needed to counter hypersonic and other evolving threats. A contractor responsible for the on-board infrared sensor told us it launched T0 satellites without the software needed to demonstrate on-board mission processing to maintain the T0 launch schedule. The contractor said SDA successfully uploaded the software to the first T0 satellite in March 2025, after nearly 2 years on orbit. SDA identified assessing the tradeoff between processing mission sensor data onboard the satellite and on the ground as a key goal of T0. The contractor said it lost an opportunity to apply lessons learned from on-board mission data processing from T0 to T1 and T2 efforts because materials for subsequent tranches have already been ordered and received, constraining design. The contractor said that while it has been able to leverage some of the data collected from T0 satellites, limited opportunities for passing data to the ground and issues with other satellite subsystems have limited opportunities to learn from the infrared sensor’s performance on T0.

Launch Detection and Missile Tracking in LEO

The satellites comprising T1 will provide SDA’s first attempt at detecting missile launch without an operator prompting the satellite to look for an event or cueing by the enterprise ground system. While T0 sensors were able to detect missile launches with operator prompting, the operational system is expected to be surveilling Earth, all the time, and notifying operators of potential threats.

As mentioned earlier in this report, the missile threat is evolving, requiring infrared sensors to track dimmer, faster targets that are more difficult to discriminate than traditional ballistic missiles. New, emerging weapons can maneuver in flight, which renders established techniques of missile tracking less effective because the target is moving very quickly during flight with an unpredictable trajectory. Infrared payloads on the tracking satellites use focal plane arrays, a type of sensor that converts infrared radiation into electrical signals, creating an image.

PWSA tracking satellites are using increasingly larger focal plane arrays, called wafers, between T0 and T2, which are expected to be better for missile tracking according to focal plane array manufacturers. We spoke with representatives from a vendor that supplies wafers for PWSA contractors. They told us that manufacturing larger format wafers is difficult because it is a time intensive and delicate process, and the wafer must maintain its flatness to work as expected. Additionally, developers told us smaller wafers can be stitched together in lieu of the larger format wafers. However, this results in gaps in coverage.

SDA told us T1 Tracking and resulting data collection will be performed differently than T0. In T0, SDA told us the satellite was cued by an operator, via script, to start recording for a 10-minute window and then that recording was transmitted to the ground as raw data.[47] Because the mesh network was not in place and there were only two ground stations to serve as entry points for incoming data as part of T0, SDA told us it took multiple days for the data to downlink to the ground. For T1, tracking satellites and sensors are not planned to require cueing by the operator. This means the sensor should automatically capture the launch, develop tracks, and once processed on board, transmit data continuously to the ground in near real time. Additionally, raw data will be transmitted to the ground as capacity and bandwidth allow.[48] SDA told us T1 is intended to have a constant connection to the ground via the mesh network, enabled by seven satellites per plane forming a complete ring around the globe.

A critical aspect of identifying missile launches and tracking missiles in flight is the ability of the infrared payload and its associated algorithm to suppress clutter. This process removes unwanted signals or echoes by filtering them from the intended target’s received signal.[49] Contractors told us that because satellites in LEO have a high relative motion to Earth, each LEO satellite takes about 90 minutes to circle Earth at an altitude of 1,000 kilometers. Therefore, they have had to develop algorithms to reject clutter to focus on the target. DOD test organizations raised concerns about the ability to suppress clutter and track dim objects from LEO because it is a novel approach compared with traditional infrared sensors that have historically been looking for brighter objects. Additionally, DOD officials stated that processing to detect targets in heavy clutter is the most uncertain aspect of the Tracking Layer, as each contractor-unique infrared sensor will need to be demonstrated on orbit along with its associated clutter suppression algorithm. SDA told us that its T0 contractors have provided multiple demonstrations of their algorithms’ capabilities to suppress background clutter for a range of target types from LEO. Because multiple T1 and T2 contractors are using the same infrared payload and clutter suppression algorithm provider, these demonstrations can inform improvements over T0.

SDA Is Applying Some Lessons Learned to Future PWSA Space-Ground Integration

In its recent T3 contract awards, SDA is applying some lessons learned from T1 and T2 ground contract challenges to better align ground and satellite development efforts. For T1 and T2, SDA delegated integration responsibilities to the ground segment contractor. In April 2025, SDA announced it awarded a $55 million contract to a third-party contractor, separate from ground and satellite contractors, to act as the dedicated integrator for T3 efforts. This contract, awarded to Science Applications International Corporation, is the result of challenges in testing and operating satellites from different manufacturers in previous tranches. SDA expects that having a third-party contractor as the integrator will help alleviate challenges that T1 and T2 experienced with the integration efforts involved with the ground systems and satellites.

The T1 ground contract was awarded approximately 3 months after the T1 satellite contracts, which resulted in late development and integration of the ground system and satellite ground systems. SDA attempted to alleviate this issue in T2 by allowing the ground contractor to start work prior to agreeing upon the terms and conditions of the contract, which it also awarded 11 months after it awarded the T2 satellite contracts. According to DCMA, the ground segment contractor expended additional resources to minimize schedule effects, but ground contractor development teams continue to fall behind schedule due to the complexity of the work.

SDA acknowledges that concurrent engineering and integration among multiple NOVA and SUPERNOVA contractor teams is risky. It noted that supply chain delays and late NOVA deliveries to the ground operations centers contributed to the risk of failing to complete integration testing prior to the T1 launch. The T1 ground operations centers are dependent on both the ground and space segments for successful delivery. The T1 ground segment delivery is so behind schedule, according to the contractor, that it is unlikely to recover even given T1 satellite launch delays and resources added. In September 2024, the ground contractor was unable to demonstrate system readiness as scheduled. Recent updates from SDA show that the ground readiness review was not complete as of October 2025.

Both satellite and ground contractors told us that significant orchestration is required to ensure requirements and standards are being interpreted and implemented similarly across the enterprise. To achieve this, the ground contractor told us it conducts 22 working groups each week to support interoperability efforts between ground and space segments. While the contractors reported that the meetings were mutually beneficial for all parties, they also noted challenges due to proprietary information and competition concerns among contractors. For example, one T1 satellite contractor told us that it is using a supplier that previously worked under a different satellite contractor in T0. Due to contractual limitations with its T0 satellite contractor, however, the supplier cannot fully share lessons learned with the T1 contractor.

SDA stated that it learned in T1 and T2 that integration needs to happen from the beginning. This was echoed by the T1/T2 ground contractor, which reported that integration would be easier if ground and space segments were awarded at the same time to keep both sides in sync with their respective development phases. SDA told us that moving forward, the ground and space segments would not be tied together with satellite launches. The ground system will be an enterprise capability that serves all tranches and will be continually updated.

SDA Requirements and Prioritization Processes Lack Transparency for Warfighters

Warfighters told us they lack insight into how SDA defines and prioritizes tranche requirements. Additionally, SDA is planning to defer T1 capability to launch as early as possible but is not providing insight to the warfighter on how, when, and whether capability will be delivered.

SDA Tranche Requirements Setting Process Lacks Transparency for Warfighters

Officials we spoke with from three combatant commands said that they lack insight into how SDA establishes requirements for each tranche. SDA’s acquisition strategies for T1 and T2 state that SDA determines each program’s requirements using multiple approved requirements and guidance documents as well as the Warfighter Council process. The requirements setting process described to us by the combatant commands, though, differs from the Warfighter Council operating procedures SDA describes in its charter. This situation is therefore inconsistent with SDA guidance and our leading practices for product development.[50]

SDA’s Warfighter Council charter from November 2020 states that requirements identification, definition, and prioritization will be a collaborative process between SDA and its council members, which, as previously noted, include combatant commands. Further, the charter states that SDA and council members, together, will determine which requirements will be included in future SDA tranches, and through ongoing collaboration and feedback will refine the requirements. Our leading practices for product development found that leading companies seek and obtain continuous user feedback throughout the development cycle to determine if the design is meeting user needs and reflects a product with the minimum capabilities needed for customers to recognize value.

Despite the Warfighter Council charter indicating the council’s collaborative process, combatant commands said that council meetings are comprised of an SDA presentation rather than an interactive dialogue among council members, leaving members relegated to listening. One combatant command office told us that it appeared that requirements for an upcoming tranche are already determined by the time of the Warfighter Council meetings. The combatant commands we spoke with agreed that the council meetings are not decision-making meetings that involve evaluating options and reaching consensus. Rather, it appears to these combatant commands that SDA focuses the meeting on disseminating information about decisions made by SDA ahead of the meeting.

In addition, combatant commands told us that they lacked detailed insight as to the disposition of warfighter requirements they had submitted to SDA for consideration, but which SDA had not yet included in planned tranches. Specifically, some combatant commands we spoke with told us that requirements they submitted that were not included in a tranche, or those that will be deferred to a later tranche, are not discussed at Warfighter Council meetings. Combatant commands told us they lack insight into how and why SDA prioritizes requirements for inclusion in each tranche.

While SDA told us that it offered feedback opportunities leading up to and following the T3 council meeting on requirements that had been submitted, officials from one combatant command said the process to receive adjudication for their T3 requirements from SDA was insufficient. Officials said SDA informed the combatant command that SDA had conducted analysis to determine what would be included in T3. When SDA submitted documentation to the requesting combatant command, the officials said SDA cited general reasons for not including the requirement, such as that the requirement was cost prohibitive, or technology required to satisfy the requirement was immature. Further, the combatant command officials said SDA’s documentation did not include technical analysis to support deferring the requirement or information as to when the requirement would be included in a future tranche. In discussing our findings for this report with SDA, the SDA Director was surprised to learn that some combatant commands said the requirements process lacked transparency. SDA officials told us that the Warfighter Council process has evolved since the 2020 charter, and that SDA is currently drafting an update.

Because SDA’s requirements-setting through the Warfighter Council meetings so far has not been collaborative or transparent, council members lack insight into whether and when PWSA will deliver planned capabilities. SDA is not providing combatant commands insight into the prioritization of submitted requirements and combatant commands are unsure when their operational needs will be met. As a result, combatant commands told us that, although they have submitted requirements, they are concerned that PWSA will not provide the data or coverage they need. Without collaboration with warfighter participants in identifying, defining, and prioritizing requirements, SDA is at risk of developing an architecture that falls short of warfighter needs. However the Warfighter Council process evolves, and its charter is updated, SDA should provide regular opportunities for interactive feedback from the warfighter.

SDA Is Not Providing Insight into Process to Defer Capabilities for T1 Programs

SDA is considering deferring some capabilities it had planned to deliver in T1, but so far has not provided insight to the warfighter into what capabilities are being deferred or how the agency tracks deferred capabilities. SDA documentation highlights an increased urgency as of January 2025 to avoid further delay of the T1 launches. At that time, the best case scenario was to launch the first of the T1 satellites in May 2025. SDA had efforts underway at that point to determine a minimum set of capabilities required to launch T1 satellites.[51] Multiple agencies—including the combatant commands, CAPE, and DOD test organizations—reported that SDA was not forthcoming with updates regarding PWSA execution status. Officials from some of these agencies noted that information they were able to obtain came from public social media posts, like SDA’s LinkedIn account, rather than SDA directly.[52] CAPE officials confirmed that SDA was making trade-offs to stay within budget and schedule parameters but said they were unaware of what the trade-offs included or the logic behind them.

Typically, requirements that are not immediately slated for development are placed into what is commonly referred to as a backlog. Our leading practices emphasize the importance of using a backlog to organize, rank, and track included and deferred capabilities.[53] This backlog is then considered along with any new requirements when making future development priority decisions. In response to the findings of this report, SDA officials said requirements submitted by Warfighter Council members that are not met by the current tranches of PWSA remain in the hands of SDA for potential inclusion in future tranches.

SDA originally planned to begin launching T1 Transport satellites in September 2024; however, according to SDA, supply chain delays have resulted in a schedule slip of approximately 1 year. SDA has already awarded incentive fees under the contracts to two satellite contractors, totaling $40 million, to try to maintain its revised T1 launch schedule. SDA is weighing changes to the included capabilities and testing requirements to launch as soon as possible. According to SDA, areas under consideration for trade-offs include reduced or delayed capability and increased performance risk. Additionally, SDA indicated that these trade-offs to maintain launch schedule would likely result in SDA accepting additional program risk ranging from early degradation of satellites on orbit to non-acceptance by the military services. As was noted in a 2022 DOD independent risk assessment on missile warning programs, launching missile warning satellites does not equate to delivering missile warning capabilities.[54]

Space and ground contractors are also making trade-off decisions based on maintaining launch schedule, which some indicated to us is, in their view, a top priority for SDA. Contractors told us that SDA’s emphasis on maintaining launch schedule influences how contractors address technical issues. One contractor said that maintaining SDA’s schedule influences whether the contractor fixes a problem or accepts it as a risk, deferring resolution to a future date. Another contractor told us the 2-year development and launch cadence causes it to seek out “band-aid” solutions for problems, postponing efforts to identify and fix root causes to a future tranche. For example, if on-orbit issues are identified in T0, but satellites are too far into the integration phase, this contractor said it will implement a software work-around in T1 to preserve schedule and pursue a hardware fix before the T2 satellites launch. The viability of this approach for any contractor depends upon whether it is a participant in subsequent tranches.

We previously found that off-ramping capabilities that can be deferred to a later iteration to meet schedule goals can be a leading practice, but only if the deferred capabilities are not essential to the users. In this case, combatant commands have said that they do not have insight into how SDA prioritizes requirements. Further, using a backlog, in coordination with users, provides insight into when capabilities will be delivered. Without such a backlog, prioritized on warfighter needs and that maintains traceability between overall MW/MT requirements and tranche development, SDA is at risk of paying for satellites that do not meet the warfighter’s needs, and not delivering capabilities on the timeline promised.

Early Milestone Achievements Do Not Reflect Schedule Challenges, and Life-Cycle Cost to Deliver PWSA Remains Unknown

SDA reports success achieving early milestones, but these achievements do not reflect schedule challenges associated with moving from design to on-orbit capability. Further, DOD does not know the life-cycle cost to deliver missile warning and tracking capabilities.

Reported Milestone Successes Do Not Reflect Overall Schedule Challenges

The SDA planning documents we reviewed, which focus on major milestones such as design review events and launch dates, do not reflect the overall schedule challenges and nuances of moving from design to on-orbit capability for PWSA. In response to our repeated requests to see a government integrated master schedule depicting PWSA as a whole, SDA provided only high-level, static timeline pictures because it had not developed a schedule at the architecture-level.[55] According to our best practices, an integrated master schedule constitutes a program schedule that includes the entire required scope of effort, including the effort necessary from all government, contractor, and other key parties for a program’s successful execution from start to finish.[56]

SDA contracts require the satellite contractors to integrate their own integrated master schedules into the government’s master program schedules for T1 and T2, which reflect each middle tier of acquisition program. However, SDA officials told us they did not develop an integrated master schedule for scheduling, executing, and tracking the work to implement PWSA at the architecture level, to include all the space segment and ground segment efforts.