PERSONNEL SECURITY CLEARANCES

Actions Needed to Address Significant Data Reliability Issues That Impact Oversight

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-26-107100, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Alissa H. Czyz at CzyzA@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Federal agencies must vet individuals who will need security clearances to access classified information. In 2018, we put this process on our High-Risk List partly due to delays and IT systems issues. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) oversees the efficiency and effectiveness of the process. ODNI has stated that consistent data are vital to meeting these responsibilities.

GAO Key Takeaways

In 2019, ODNI began requiring over 100 agencies that vet cleared personnel to submit data on timeliness, the number of investigations completed, and other key aspects of the personnel security clearance process. But more than 60 percent of the data we reviewed were not reliable across eight reporting requirements and seven agencies.

ODNI officials look closely at data measuring the time for agencies to complete the process. Of the timeliness data we analyzed, 86 percent were inaccurate—a third by 20 percent or more. Most of these inaccuracies were due to a calculation method inconsistent with ODNI guidance. This affected the timeliness measurement of 95 percent of the clearances completed across the government. Agency officials stated they revised their method to align with ODNI’s guidance for data collected starting in fiscal year (FY) 2025. However, much of the data reported to Congress and the public from 2020–2024 has underestimated the time to complete the clearance process.

ODNI reviews data it collects from agencies, but not in a way that aligns with data reliability principles. It also has not issued adequate guidance to agencies for assessing their data. Addressing these gaps will ensure ODNI and Congress have more reliable data to enable better oversight.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed FY 2024 data from ODNI and

· Departments of Defense, Energy, and the Treasury

· General Services Administration

· National Capital Planning Commission

· National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

· U.S. Agency for International Development

We also compared ODNI’s oversight to key practices and interviewed officials.

What GAO Recommends

We make four recommendations, including that ODNI implement a process to assess the reliability of agencies’ security clearance data and issue guidance to agencies on assessing data. ODNI did not explicitly agree or disagree with these but raised concerns, which we addressed.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DCSA |

Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency |

|

DNI |

Director of National Intelligence |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

IC |

intelligence community |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

ODNI |

Office of the Director of National Intelligence |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

PAC |

Performance Accountability Council |

|

SNAP |

Security Executive Agent National Assessments Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 11, 2025

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The government-wide personnel security clearance process helps ensure the trustworthiness of the federal government’s workforce.[1] Federal departments and agencies use this process to vet personnel to determine whether they are eligible to access classified information or hold a sensitive position. The process further helps to prevent unauthorized disclosure of classified information that could put national security at risk. In January 2018, we placed this process on our High-Risk List due to delays in the government completing the clearance process, a lack of measures to assess the quality of investigations, and information technology (IT) systems challenges.[2]

As the Security Executive Agent, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) is responsible for overseeing the security clearance process and ensuring, among other things, the process’s effectiveness, efficiency, quality, and timeliness. To fulfill these responsibilities, the DNI has stated that standardized, consistent data from agencies are vital.[3] Therefore, beginning in 2019, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) has required quarterly data reports from all agencies that conduct national security vetting. Under ODNI’s guidance, such reports are to cover key aspects of the security clearance process, including the number of investigations and timeliness, among others.

However, we and some executive branch offices of inspectors general have reported that data on security clearance timeliness and reciprocity—when agencies honor previously granted clearances—are not sufficiently reliable for ODNI to carry out its oversight role.[4] For example, in our 2025 High-Risk Report, we noted that ODNI’s timeliness data were not sufficiently reliable to enable us to determine the percentage of executive branch agencies that met timeliness goals for the security clearance process.[5] Similarly, in January 2024, we reported that ODNI did not have reliable data to determine the extent that agencies were granting reciprocity.[6]

In addition, in November 2023, the Office of the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community reviewed data from seven intelligence community (IC) organizations. The review found that several of these organizations did not accurately capture, document, or report information on the time to complete the security clearance process. In addition, these IC organizations did not calculate processing timeliness in a consistent manner.[7] Also, in September 2021, the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of State reported that the department reported inaccurate data to ODNI in fiscal year 2019 on the timeliness of its clearance process.[8]

House Report 118-125, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, includes a provision for us to assess the reliability of data and ODNI’s approach for oversight of the personnel security clearance process.[9] In this report, we evaluate the extent to which ODNI (1) has reliable data to oversee the government-wide personnel security clearance process and (2) has used a data-driven approach to inform its oversight of the security clearance process.

To address both objectives, we reviewed key documents, including executive orders; guidance; and documents about the personnel security clearance process, ODNI’s oversight, and personnel vetting reforms.[10]

For our first objective, we collected personnel security clearance data from a nongeneralizable selection of seven agencies that were required to submit data to ODNI. We selected the third quarter of fiscal year 2024 for reviewing data since it was the most recently available data at the time of our review. We selected a cross-section of agencies from various sectors of the executive branch including intelligence, nonintelligence, defense, and nondefense. We selected a mix of cabinet-level departments and independent agencies and considered factors such as whether the agency conducts its own background investigations, among others. The seven agencies we selected for a more in-depth review were: the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA),[11] the Department of Energy, the Department of the Treasury, the General Services Administration, the National Capital Planning Commission, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. These seven agencies are, collectively, required to submit security clearance data to ODNI for over 90 percent of all individuals with a clearance.[12]

We analyzed data ODNI collects across key aspects of the security clearance process including the timeliness of different phases of the clearance process, reciprocity, and continuous vetting.[13] To assess the reliability of the data, we evaluated the accuracy, completeness, and in some instances, consistency of the data. We also compared ODNI processes related to data for security clearances to the principle established in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government that management should use quality information to achieve its objectives.[14] Additionally, we interviewed officials from six of the seven selected agencies and ODNI about their data collection and reliability efforts.

For our second objective, we defined a data-driven approach to oversight as one that effectively builds and uses evidence—including performance information and statistical data—to manage performance. To assess how ODNI builds and uses evidence as part of its clearance process oversight, we compared evidence related to ODNI’s oversight of the personnel security clearance process to 13 key practices and 29 supporting actions we published in prior reporting on evidence-building and performance-management activities.[15] We then assessed the extent to which ODNI followed each key practice using a scorecard methodology and assigned ratings of generally followed, partially followed, or did not follow for each key practice.

While we focused our analysis on ODNI actions to oversee the personnel security clearance process specifically, we considered any evidence related to personnel vetting more broadly if the personnel security clearance process was subject to the actions indicated in the evidence. In addition, we interviewed ODNI officials to (1) obtain testimonial evidence where we had not found documentary evidence corresponding to the criteria, (2) obtain their perspectives on our assessment, and (3) if applicable, determine reasons ODNI did not generally follow all key practices. Further information on our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Personnel Security Clearance Process

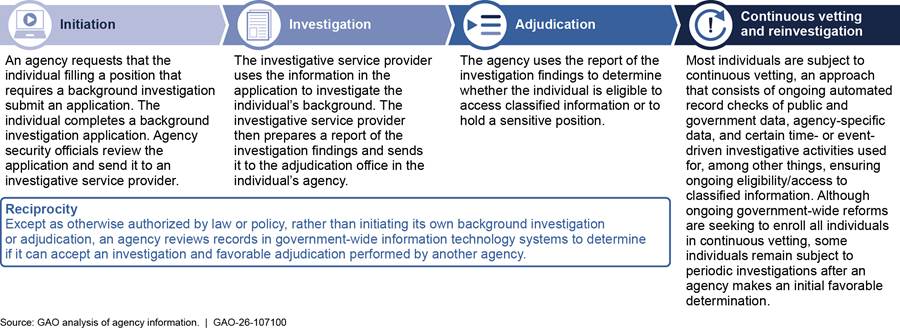

Federal departments and agencies use the personnel security clearance process to vet personnel and determine their eligibility to access classified information or hold a sensitive position.[16] The process consists of multiple phases: initiation, investigation, adjudication (or alternatively, reciprocity); as well as continuous vetting or reinvestigation, as shown in figure 1.

The Performance Accountability Council and the DNI’s Role in Overseeing the Government-Wide Personnel Security Clearance Process

In June 2008, Executive Order 13467 established the Security, Suitability and Credentialing Performance Accountability Council (PAC) as the government-wide entity responsible for implementing reforms to the federal government’s personnel vetting processes.[17] The executive order, as amended, outlines the responsibilities of the PAC and designates the four principal members of the PAC as (1) the Deputy Director for Management of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), (2) the DNI, (3) the Director of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), and (4) the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security.[18]

In addition, Executive Order 13467, as amended, specifies the responsibilities of the DNI as the Security Executive Agent.[19] The executive order states that as the Security Executive Agent, the DNI shall

· direct the oversight of investigations, reinvestigations, adjudications, and, as applicable, polygraphs for eligibility for access to classified information or eligibility to hold a sensitive position made by any agency; and

· be responsible for developing and issuing uniform and consistent policies and procedures to ensure the effective, efficient, timely, and secure completion of investigations, polygraphs, and adjudications relating to determinations of eligibility for access to classified information or eligibility to hold a sensitive position.[20]

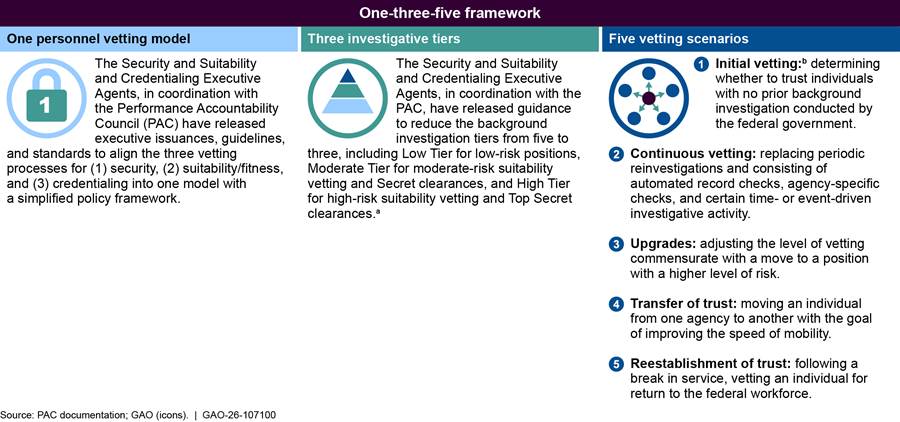

Trusted Workforce 2.0

In March 2018, the PAC’s principal members initiated Trusted Workforce 2.0 to reform the personnel vetting processes. Specifically, Trusted Workforce 2.0 is a series of policy and procedural reforms that officials designed to streamline government-wide personnel vetting and address problems, such as lengthy background investigations, persistent backlogs, inconsistent practices across agencies, and information security concerns. Trusted Workforce 2.0 aims to align the three personnel vetting processes and revise the investigative tiers and vetting scenarios, as depicted in the PAC’s “one-three-five” framework for the reform shown in figure 2.

aSpecifically, the new investigative tiers will include: Low Tier for low-risk, nonsensitive positions and physical or logical access or credentialing determinations; Moderate Tier for moderate-risk public trust and noncritical sensitive positions and granting eligibility and access to classified information at the confidential or Secret level, or L access; and High Tier for high-risk public trust and critical or special sensitive positions and granting eligibility and access to classified information at the Top Secret level, access to sensitive compartmented information, or Q access. See Office of the Director of National Intelligence and Office of Personnel Management, Office of the Director, Federal Personnel Vetting Investigative Standards (May 17, 2022).

bUnder Trusted Workforce 2.0, an initial vetting determination is also conducted for previously vetted individuals who have been away from the government for more than 5 years.

ODNI’s Approach to Overseeing the Personnel Security Clearance Process

ODNI uses two methods to carry out the DNI’s responsibility to oversee the government-wide personnel security clearance process. First, the DNI established the Security Executive Agent National Assessments Program (SNAP).[21] Under this program, SNAP teams consisting of ODNI personnel assess agencies to ensure they follow applicable statutes, executive orders, and regulations. The teams also assess the extent that agencies are implementing policies, processes, and procedures established under the personnel vetting reform effort, Trusted Workforce 2.0. SNAP teams assess about 30 agencies or components of agencies each year.[22] They assess agencies by (1) reviewing agencies’ operation manuals, policies, documents, and case files, and (2) interviewing staff responsible for the clearance processes, including security and personnel officials. SNAP teams report their findings and recommendations to agencies and follow up to assess the agencies’ progress in implementing the recommendations.

Second, ODNI collects data from all agencies that conduct national security vetting. In 2019, ODNI required agencies to begin reporting data on their national security vetting programs quarterly and annually to enable the DNI to assure the quality, consistency, and integrity of the national security vetting practices.[23] ODNI directed agencies to report a variety of clearance-related data including the number of investigations, adjudications, instances of reciprocity, continuous vetting alerts, and time for agencies to complete the clearance process, among other things.

Agencies Involved in the Security Clearance Process

In addition to ODNI serving as the agency facilitating the DNI’s oversight, over 100 departments and agencies are involved in the security clearance process for federal civilians, military personnel, and contractor personnel.[24] In particular, DCSA has a significant role. DCSA serves as the primary investigative service provider for the federal government and performs about 95 percent of the federal government’s background investigations, including for most Department of Defense (DOD) personnel and other departments and agencies.[25]

In addition, about two dozen other agencies are also investigative service providers. For example, multiple IC organizations are investigative service providers and perform investigations for their personnel. Most agencies adjudicate the results of investigations of their employees to determine if they are eligible to access classified information.

Agencies use continuous vetting services provided by DCSA or ODNI. DCSA enrolls personnel from DOD and other agencies in Mirador, its IT system for continuous vetting. ODNI also offers continuous vetting services through its Continuous Evaluation System.

Key Practices for Evidence-Based Decision-Making

Federal decision-makers need evidence—including performance information and statistical data—about whether federal programs and activities are achieving intended results. Congress and executive branch leaders can use evidence to determine how federal programs and activities could best make progress toward national objectives such as enhancing national security. For decades, various laws, policies, and guidance have directed evidence-building and performance-management activities at multiple levels across the federal government—including government-wide; at individual departments and agencies; and for individual offices, bureaus, programs, and other activities.[26]

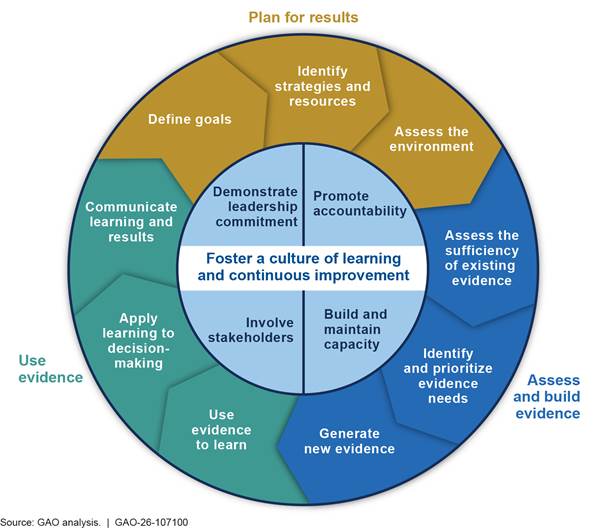

To reflect these directions and activities, in 2023 we developed a guide that included 13 key practices, organized in four topic areas, that can help federal agency leaders at any organizational level develop and use evidence to manage and assess the performance of federal programs effectively (see fig. 3).[27] To develop these practices, we reviewed (1) federal laws and guidance related to evidence-building and performance-management activities and (2) several hundred of our past reports. We refined the practices, as appropriate, based on input from cognizant officials at 24 major federal agencies and OMB staff.

The first three topic areas and their practices—illustrated as the outer ring of the figure—are part of an iterative cycle. Our past work has shown that implementing one of these practices can inform actions taken to implement others. The fourth topic area and its practices—all related to organizational culture—are central to effectively implementing the cycle.

· Plan for results. The practices in the “plan for results” topic area are foundational to the other two topic areas in the iterative cycle. Until an agency defines goals, it is not positioned to identify or prioritize its evidence needs to use evidence in monitoring progress toward those goals.

· Assess and build evidence. The practices on assessing and building evidence emphasize the need for high-quality evidence to help decision-makers assess, understand, and identify opportunities to improve the results of federal efforts. Following quality standards can provide decision-makers and stakeholders greater assurance that they can use the evidence for its intended purpose in making decisions.

· Use evidence. The benefit of building evidence is fully realized when it is used to learn and inform different types of decisions.[28] For example, quantitative performance data can help determine whether performance goals were met, and other types of analysis can help an organization better understand what led to the results it achieved or why desired results were not achieved.

· Foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement. A federal organization’s culture, and demonstrated commitment of senior leaders in particular, is key to its success in building and using evidence to manage and improve its performance. These practices help provide the necessary foundation for the organization to plan for results, assess and build evidence, and use that evidence to learn and improve.

Most ODNI Data We Reviewed Were Not Reliable to Oversee the Personnel Security Clearance Process

More than sixty percent of the data we reviewed that ODNI used to oversee the security clearance process in fiscal year 2024 were not reliable across eight reporting requirements. ODNI used data that were not reliable, in part, because it has not implemented a process to assess security clearance data using principles for data reliability, issued guidance on assessing data reliability, or defined the role of a key official accountable for data.

More Than Sixty Percent of ODNI’s Security Clearance Data We Reviewed Were Inaccurate or Incomplete Across Eight Reporting Requirements

A Majority of ODNI’s Security Clearance Data We Reviewed Were Inaccurate or Incomplete in the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2024

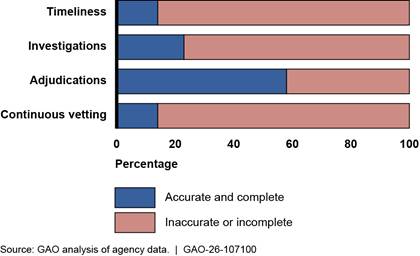

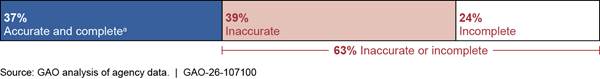

Based on our analysis of over 300 statistics, we found that over 60 percent of ODNI’s security clearance data we reviewed for the third quarter of fiscal year 2024 were inaccurate or incomplete.[29] We selected and analyzed 44 descriptive statistics, on average, for each of the seven agencies we reviewed, or about 300 statistics in total.[30] For example, we analyzed descriptive statistics on the number of individuals with a security clearance in an agency, and the average times to complete adjudications for individuals who are undergoing the security clearance process. Of the total statistics we analyzed, 63 percent (191 out of 305) were inaccurate or incomplete. Specifically, 39 percent (118 out of 305) were inaccurate, and 24 percent (73 out of 305) were incomplete (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Percent of Inaccurate or Incomplete Descriptive Statistics Used for Oversight of the Security Clearance Process, Third Quarter Fiscal Year 2024

aWe could not verify the accuracy and completeness of all underlying data. When the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s summary statistic for an agency matched the summary statistic we calculated using the agency’s case-level data, we identified that statistic as accurate. However, our methods did not enable us to determine whether the agency’s case-level data accurately reflected factual circumstances. For instance, if an agency conducted 25 investigations in a quarter, but its case-level data inaccurately showed that the agency conducted 10 investigations, our methods would not enable us to identify this error.

We also estimated the magnitude of the inaccuracies we identified and found that the majority of inaccurate statistics were inaccurate by 50 percent or more. To measure the magnitude of inaccuracies, we compared summary statistics we calculated using agencies’ case-level data to agency-calculated statistics to identify the difference between the two. However, because we were not able to determine which of the two statistics was accurate, if either, we then divided the difference between the two by the average of the two statistics, multiplied that result by 100 and used that result to estimate the magnitude of the inaccuracy. Of the 118 inaccurate statistics we identified, more than half (60 out of 118) were inaccurate by 50 percent or more and nearly a third (34 out of 118) were inaccurate by 100 percent or more (see table 1).[31]

Table 1: Estimated Magnitude of Inaccuracies in Security Clearance Data Used for Oversight, Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2024

|

Number of statistics GAO analyzed |

Estimated magnitude of inaccuracy |

|

43 |

1 to 24 % |

|

15 |

25 to 49 % |

|

23 |

50 to 74 % |

|

3 |

75 to 99 % |

|

34 |

100 or more % |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107100

Note: Of the 305 descriptive statistics we analyzed, 118 were inaccurate. The 118 statistics are organized by the magnitude of error.

Further, the majority of inaccuracies were concentrated between 1 and 24 percent. For example, ODNI’s statistic showed that the U.S. Agency for International Development had initiated 34 Secret clearances for contractor personnel, whereas using the agency’s case-level data, we found that it had initiated 38 of these clearances. When dividing the difference between the two by the average of the two statistics, ODNI’s statistic was inaccurate by 11 percent.

Similarly, the extent to which ODNI’s data were incomplete for the agencies we reviewed varied. For example, ODNI did not have data for one of 45 statistics we analyzed for the Department of Energy, illustrating a lower level of incomplete data. On the other hand, ODNI did not have any of the 39 statistics we analyzed for the National Capital Planning Commission.[32]

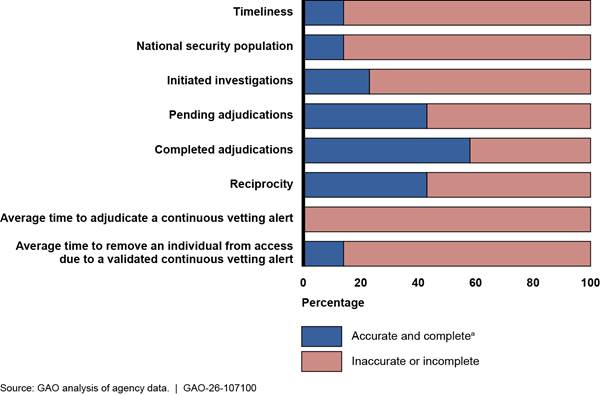

ODNI’s Security Clearance Data That We Reviewed Were Inaccurate or Incomplete Across Eight Reporting Requirements

In addition, the inaccurate or incomplete statistics we found were widespread across eight reporting requirements and all seven agencies we reviewed, with no single data type or agency being the primary source of these issues. For seven out of the eight reporting requirements, a majority of the descriptive statistics were incomplete or inaccurate, as shown in figure 5. Moreover, on average, 63 percent of the statistics across the seven agencies contained inaccuracies or were incomplete. Further, officials from most of the agencies we selected agreed with our findings that their data for this quarter contained inaccuracies.

Figure 5: Extent of Selected Agencies’ Data Inaccuracies or Incompleteness Across Eight Reporting Requirements for the Personnel Security Clearance Process, Third Quarter Fiscal Year 2024

Note: Reciprocity occurs when officials from one agency review records in government-wide IT systems to determine if they can accept a personnel vetting determination, such as a security clearance granted by another agency. Continuous vetting is an approach that consists of ongoing automated record checks, of public and government data, agency-specific data, and certain time or event driven investigative activities used for, among other things, ensuring ongoing eligibility/access to classified information.

aWe could not verify the accuracy and completeness of all underlying data. When the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s summary statistic for an agency matched the summary statistic we calculated using the agency’s case-level data, we identified that statistic as accurate. However, our methods did not enable us to determine whether the agency’s case-level data accurately reflected factual circumstances. For instance, if an agency conducted 25 investigations in a quarter, but its case-level data inaccurately showed that the agency conducted 10 investigations, our methods would not enable us to observe this inaccuracy.

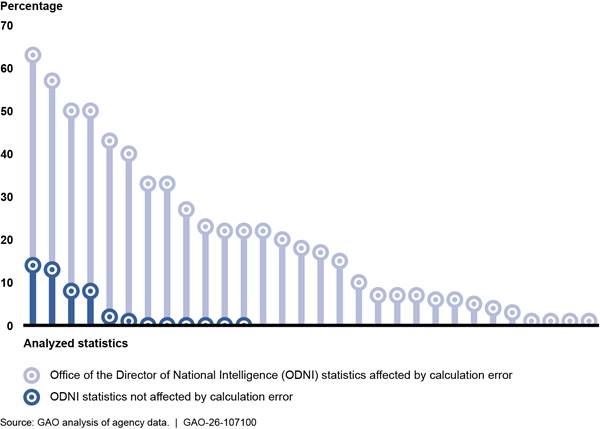

Timeliness. ODNI officials focus particular attention on data measuring the timeliness of the clearance process and use these data to assess the extent that agencies meet timeliness goals.[33] However, 86 percent (36 out of 42) of the timeliness descriptive statistics we analyzed were inaccurate. Specifically, 30 of the 36 inaccurate statistics we analyzed were inaccurate due to an error we found DCSA made in identifying the sample of cases to use to calculate the average times for agencies to complete the fastest 90 percent of clearances. Specifically, DCSA did not exclude the 10 percent of cases with the slowest end-to-end times and use the resulting sample of cases to calculate the average time agencies took to complete the end-to-end time and each phase of the clearance process, as ODNI guidance instructs. Instead, DCSA excluded the 10 percent of cases with the slowest end-to-end times and the slowest times in each phase of the process. As a result, DCSA incorrectly used four different samples of cases to calculate the average times. Under goals that applied at the time of our review, agencies were required to complete the fastest 90 percent of clearances in specified amounts of time for each phase of the clearance process.[34] For more details on this error, see appendix II.

The 30 descriptive statistics affected by DCSA’s error were more substantially inaccurate than the statistics ODNI calculated using agencies’ case-level data.[35] Specifically, 100 percent (30 out of 30) of the statistics affected by DCSA’s error were inaccurate, and nearly half (14 out of 30) were inaccurate by 20 percent or more. For the other 12 of the 42 statistics we reviewed not affected by this error, half (six out 12) were inaccurate, but these six statistics were inaccurate by less than 20 percent (see fig. 6). The inaccuracies across ODNI’s timeliness data we analyzed, regardless of the calculation method used, ranged from 1 percent to 63 percent.

Figure 6: Magnitude of Inaccuracies in Timeliness Statistics Affected and Not Affected by a Calculation Error by the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA), Third Quarter Fiscal Year 2024

Note: Calculation error refers to the error that resulted from DCSA’s method for calculating the average times for agencies to complete the fastest 90 percent of clearances, which was inconsistent with ODNI guidance.

Additionally, due to DCSA’s error, the average times ODNI calculated using DCSA’s data systematically underestimated the time for agencies to complete each phase of the clearance process. For example, as a result of DCSA’s error, ODNI incorrectly determined the General Services Administration’s average time to complete the initiation phase of the clearance process as 28 days. However, if the correct calculation was used, the average initiation time would have been 36 days. In another instance, due to DCSA’s calculation error, ODNI determined that DOD had met a timeliness goal for contractor personnel that it had not met.[36]

DCSA officials agreed with our observations about its method, stating they began using this incorrect method in fiscal year 2020, and have revised their process to align with ODNI’s guidance, effective from the first quarter of fiscal year 2025. Additionally, ODNI officials stated that, in the future, this calculation error would not be an issue as new timeliness reporting metrics under Trusted Workforce 2.0 call for agencies to report timeliness for 100 percent of cases.[37]

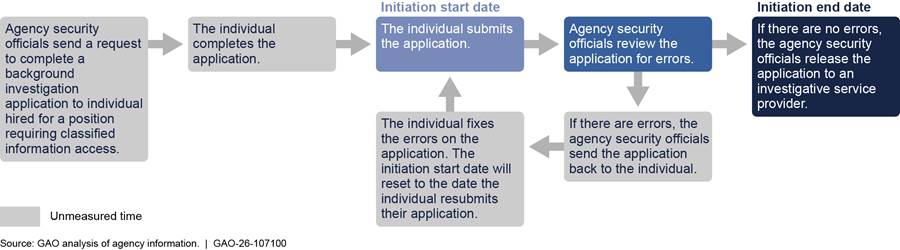

Lastly, we identified that ODNI’s data on the time to complete the initiation phase were incomplete. Specifically, ODNI defines the initiation start date as the day an individual submits a background investigation application, according to officials, and the end date as the day the agency sends the application to an investigative service provider. However, this definition does not include the time for an individual to complete the application. Additionally, if the agency finds an error in its review of the application, the definition does not include the additional time for an individual to revise and resubmit the application, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Unmeasured Time in the Initiation Phase of the Personnel Security Clearance Process, According to the Definition Used by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence

As a result, ODNI’s data on the initiation phase did not account for as many as 15 days. Specifically, officials from five of the seven agencies in our review stated individuals typically take anywhere from 3 to 10 days to complete a background investigation application and around 2 to 5 days to correct and resubmit the application, if needed. Officials from DCSA stated they identify errors in 5 percent of applications, while officials from the U.S. Agency for International Development stated they identify errors in 50 percent of applications. ODNI officials stated they recognized this gap in measuring the time for the initiation phase and have changed the definition to include the unmeasured time in a new measure for initiation that is a part of the Trusted Workforce 2.0 reform that is planned to take effect in fiscal year 2026.

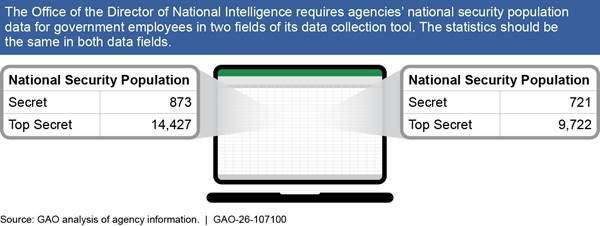

National security population.[38] ODNI requires agencies to submit the same information on the number of individuals with a security clearance in two separate fields in its data collection tool. The statistics in the two fields should match, but five of the seven agencies we analyzed reported different numbers in these two fields, suggesting that the data are inaccurate in at least one of these fields. See figure 8 for an example of this inaccuracy from ODNI’s data for the Department of Energy. We also found that data for this requirement for three agencies were incomplete and we did not identify inaccuracies or incompleteness in the data for the General Services Administration for this requirement.

Figure 8: Example of Inaccurate Data Collected by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence for the Department of Energy, Third Quarter Fiscal Year 2024

We analyzed 28 statistics related to the national security population and found that half (14 out of 28) were inaccurate and over a third (10 out of 28) were incomplete. Of the 14 inaccurate statistics we identified, more than half (nine out of 14) were inaccurate by 50 percent or more and nearly a quarter (three out of 14) were inaccurate by 100 percent or more.

For more details on the inaccurate and incomplete data we found for the remaining six reporting requirements, see appendix III.

ODNI Has Not Implemented a Process to Assess Data, Issued Adequate Guidance, or Defined the Role of a Key Official

Management is responsible for ensuring its data are standard, consistent, and reasonably free of errors and bias, as the effective use of data depends on their reliability. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agencies’ management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[39] The standards further state that management (1) obtains data from reliable sources that are reasonably free from errors and bias and (2) evaluates the sources of data for reliability. Similarly, a memorandum on data integrity issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) states that the value of data hinges on the reliability, validity, and overall quality of data.[40] Additionally, ODNI’s memorandum establishing data reporting requirements states that to assure the quality, consistency, and integrity of the national security vetting process, standardized, consistent metrics are vital.[41]

However, ODNI’s data were not reliable because it has not taken sufficient actions to ensure data reliability as part of its oversight. Specifically, the following three issues contribute to ODNI’s unreliable data:

· First, ODNI has not developed and implemented a process that incorporates data reliability practices or principles to assess the data it collects. Multiple organizations have issued guides that set out such data reliability practices and principles. For example, we have issued a data reliability guide that includes specific actions that can help organizations assess whether data they collect are sufficiently reliable.[42] In addition, Data Management Association (DAMA) International issued a guide that describes data management best practices and includes guidance on assessing data to ensure they are accurate and complete.[43]

ODNI officials told us they assess the reliability of agencies’ data by reviewing the data for anomalies and trends and communicating with agencies about discrepancies. These are positive actions, but ODNI’s process is not informed by data reliability practices or principles, such as those that we discuss in our guide or that DAMA International established. Also, officials from a majority of the agencies we selected stated that ODNI had not provided any feedback regarding their data, despite the inaccuracies and incompleteness we observed.

In addition, ODNI officials told us that they put the onus on agencies to ensure their data are accurate and complete. For example, ODNI includes a statement in its data collection tool stating that by submitting the requested information, agencies acknowledge that the data are the most accurate and up-to-date data available. However, ODNI does not require agencies to take any active steps to support this statement and it does not assign the responsibility of acknowledgement to a specific agency official. Additionally, ODNI officials told us they include general tips to assist in completing reporting requirements in a quarterly reminder email they send to agencies, but these steps do not incorporate data reliability practices or principles.

· Second, ODNI has not issued guidance to agencies that clarifies their role in assessing the characteristics, quality controls, and limitations of their data; and that incorporates practices or principles for assessing and ensuring the reliability of data and addressing any gaps, such as those found in our data reliability guide or those established by DAMA International. In 2023, the Intelligence Community Inspector General reported that multiple IC organizations did not capture, document, or report accurate security clearance processing timeliness information.[44] According to the report, to address the inaccuracy of IC elements’ timeliness data, ODNI and OPM issued several guidance documents including the Federal Personnel Vetting Performance Management Standards.[45] However, we analyzed these guidance documents and found that they did not incorporate data reliability principles that can help agencies assess whether data are sufficiently accurate and complete. For details of our analysis of these guidance documents, see appendix IV.

· Third, ODNI has not defined the role of a senior data official and ensured agencies have identified these officials to be accountable for reliable data. The DNI’s 2018 memorandum that requires agencies to report security clearance data also requires agencies to identify a senior official responsible for the quarterly data submissions.[46] However, the 2018 memo does not specify any responsibilities for this official. Further, officials from a majority of the agencies we selected for our review stated that ODNI has not followed up with them to ensure the agencies had designated their senior data officials. Also, officials from most of the agencies we selected were not able to identify the officials in their agency with this responsibility. ODNI officials stated that they do not know who the senior data officials are at agencies and they are open to revisiting this requirement.

Data that are not sufficiently reliable may have limited the ability of Congress and the PAC to make fully informed decisions about the Trusted Workforce 2.0 reform. For example, from 2020 through 2024, DCSA’s error in calculating timeliness statistics for DOD and over 100 other agencies resulted in underestimations of the amount of time agencies took to complete the clearance process. During this period, these inaccurate data were included in quarterly reports the PAC publishes on the status of Trusted Workforce 2.0, according to ODNI officials.

Until ODNI takes the following actions, ODNI and Congress will not have data that are sufficiently reliable to oversee the clearance process:

1. Develops and implements a process that incorporates data reliability practices or principles to assess the data it collects from agencies

2. Issues and monitors agencies’ adherence to guidance clarifying their role in assessing their data, which incorporates practices or principles for assessing and ensuring the reliability of data

3. Defines the role of a senior data official at each relevant agency, and ensures agencies have identified these officials

Further, without reliable data, ODNI will not be able to ensure the quality, consistency, and integrity of the personnel security clearance process.

ODNI Has Not Effectively Used a Data-Driven Approach in Its Oversight of the Personnel Security Clearance Process

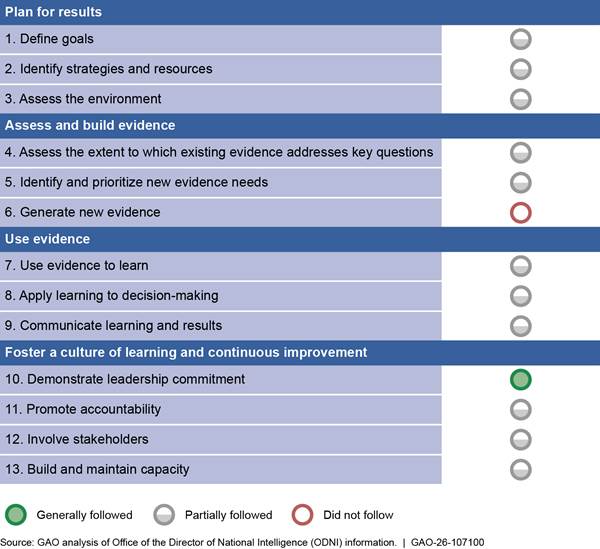

ODNI has not effectively used a data-driven approach to oversee the personnel security clearance process. Agencies that use a data-driven approach effectively build and use evidence—including performance information and statistical data—to manage performance. In particular, ODNI has not fully followed most key practices for evidence-building and performance-management activities.[47] Of 13 key practices that we developed, we found that ODNI generally followed one of these key practices, partially followed 11 of these key practices, and did not follow one key practice in its efforts to oversee the federal personnel security clearance process. (See fig. 9.) While these key practices are not requirements that agencies must follow, we distilled them from a broad range of practices identified in our past work. Our guide explains how these key practices can help agencies meet federal requirements to manage performance by building and using different sources of evidence.

Figure 9: Assessment of the Extent That ODNI Followed 13 Key Practices for Evidence Building and Performance Management

Note: Each key practice has two to three key supporting actions. For key practices we assessed as “generally followed,” we determined that ODNI generally implemented each of the supporting actions for that key practice. For key practices we assessed as “partially followed,” we determined that ODNI had partially implemented supporting actions or had a mix of generally implementing some actions and not others. For key practices we assessed as “did not follow,” we determined that ODNI did not implement any of the supporting actions for that key practice.

We compared ODNI’s oversight efforts with the 13 key practices organized across four topic areas: (1) plan for results, (2) assess and build evidence, (3) use evidence, and (4) foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement. Below, we provide illustrative examples of our assessment of one key practice in each of the four topic areas. See appendix V for a more detailed assessment.

· Plan for results: Define goals—partially followed. ODNI, in coordination with OPM, has defined a broad, overarching goal for the federal personnel vetting program, which is to establish and maintain a trusted workforce.[48] ODNI officials stated that they also used an overarching goal for the Trusted Workforce 2.0 reform effort to improve timeliness and mobility without increasing risk. In addition, ODNI has identified some long-term outcomes and near-term results that apply to the personnel security clearance process, consistent with a supporting action for the defining goals practice. For example, in the Federal Personnel Vetting Performance Management Standards Implementation Guidance, ODNI, in coordination with OPM, includes near-term results such as performance measures to assess the timeliness and quality of the initiation, investigation, and adjudication phases.[49]

However, ODNI’s personnel vetting goal to establish and maintain a trusted workforce is defined too broadly to allow it and other decision-makers to assess performance by comparing actual and planned results. In addition, ODNI does not have quantifiable targets and time frames for all its performance measures, which are key components of near-term results. Fully following this practice would help guide ODNI’s oversight by enabling it to assess performance against its goals.

· Assess and build evidence: Generate new evidence—did not follow. Although ODNI has identified some new evidence needs, it has not developed a plan for building additional evidence—such as statistical data—that it may need to assess, understand, and identify opportunities to improve results. For example, in the Federal Personnel Vetting Performance Management Standards Implementation Guidance, ODNI included new near-term results intended for future development. However, it has not yet identified how and when it will develop these near-term results. In addition, ODNI has not followed key principles for assessing the reliability of data, as discussed above, to ensure that any new or existing evidence it uses is of high quality. As a result, ODNI has reported incomplete and inaccurate information, including information that is key to assessing the progress of Trusted Workforce 2.0.

ODNI officials noted that they would like to automate and streamline the data collection process to help ensure the quality of the data they collect, but ODNI has not yet implemented those efforts. Fully following this practice would help ensure that any new evidence ODNI generates will meet its needs and can be used for its intended purpose, including to support personnel vetting reform more broadly.

· Use evidence: Use evidence to learn—partially followed. ODNI assesses whether departments and agencies have met their timeliness goals and requests that agencies that did not meet their goals identify reasons for delays and plans to improve timeliness. However, ODNI does not assess progress or develop an understanding of results for performance goals other than those related to timeliness. ODNI officials stated that other than for timeliness, they do not use the data they collect to assess progress toward goals. ODNI officials stated that the data on performance measures they will be collecting, as part of implementing the Federal Personnel Vetting Performance Management Standards Implementation Guidance, will allow them to assess progress better. Fully following this practice would help ODNI assess program outcomes and better understand the results as it oversees the personnel security clearance process.

· Foster a culture of learning and continuous improvement: Demonstrate leadership commitment—generally followed. As we have previously reported, the DNI, as part of the PAC, has demonstrated leadership in addressing challenges in the personnel security clearance process.[50] For example, ODNI issued guidance emphasizing the importance of using quality evidence to address those challenges, among other things.[51] In addition, the DNI, ODNI senior leaders, and other ODNI staff coordinate across other agencies on personnel vetting in several ways and with varying frequency, from weekly to quarterly. For example, ODNI officials noted that the DNI coordinates with other agency heads at PAC meetings, while other ODNI senior staff meet biweekly with officials from agencies such as OPM and DOD, and with security directors from the intelligence community monthly.

As we have previously reported, various laws, policies, and guidance established over past decades direct federal organizations to build and use evidence to manage performance.[52] In our key practices guide—developed to help agencies meet selected requirements for federal evidence-building and performance-management activities—we reported that federal decision-makers need evidence about whether federal programs and activities are achieving intended results to better address challenges and set priorities to improve implementation.[53] However, ODNI has not built and used evidence effectively in its oversight of the clearance process because it has not analyzed and updated its personnel vetting policy framework—the collection of policies that guides personnel vetting and Trusted Workforce 2.0—to incorporate our key practices, to the maximum extent practicable.[54]

ODNI officials acknowledged they had not developed the personnel vetting policy framework in a way that aligned with our key practices. For example, the officials noted that they had not ensured that the goals and objectives defined in different parts of the framework aligned with one another. ODNI officials also stated that they developed the personnel vetting policy framework over multiple years.

Following our key practices can help federal organizations, including ODNI, build and use evidence. Such evidence is needed for organizations to manage and continually assess performance. For example, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Office of Inspector General reported problems enrolling national security personnel in continuous vetting programs.[55] A lack of information could hinder ODNI from addressing such problems and could further hinder ODNI’s ability to achieve its goal of establishing and maintaining a trusted workforce.

Analyzing and updating its personnel vetting policy framework to incorporate our key practices, to the maximum extent practicable, would help ODNI ensure that it has the information it needs to effectively oversee the process. Obtaining sufficient information to identify and correct problems and achieve its goals for the workforce will be particularly important for ODNI and the PAC as the executive branch implements Trusted Workforce 2.0.

Conclusions

Personnel security clearances are a critical component of establishing and maintaining trust in the federal government’s workforce. The process to grant personnel security clearances helps prevent unauthorized disclosure of classified information that could put national security at risk. As the Security Executive Agent, the DNI has significant responsibilities to ensure, among other things, the effectiveness, efficiency, quality, and timeliness of the personnel security clearance process.

However, the data we reviewed that ODNI used to oversee the clearance process were not sufficiently reliable. By implementing a process for assessing the reliability of data that incorporates data reliability practices or principles, issuing and monitoring agencies’ adherence to guidance on data reliability, defining the senior data official’s role in accountability, and ensuring agencies have identified these officials, ODNI will have access to more complete and accurate data. Quality, reliable data are critical to ODNI’s oversight of the clearance process to ensure its quality, consistency, and integrity. Furthermore, taking these steps will help ensure Congress has more complete and accurate data to enable better oversight of the clearance process, and enable the PAC to more effectively monitor Trusted Workforce 2.0.

In addition, ODNI does not effectively build and use evidence to manage performance in its oversight of the security clearance process. By analyzing and updating its personnel vetting policy framework to incorporate our key practices, to the maximum extent practicable, ODNI will help ensure it has the information necessary to identify and correct problems, such as delays completing the clearance process. These steps will also help ODNI ensure that the clearance process effectively establishes and maintains a trusted workforce and will provide valuable information as ODNI and the PAC monitor the implementation of Trusted Workforce 2.0.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence:

The Director of National Intelligence should develop and implement a process that guides ODNI’s efforts to assess agencies’ security clearance data. This process should incorporate data reliability practices or principles, such as those found in our data reliability guide or those established by DAMA International. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of National Intelligence should issue and monitor agencies’ adherence to guidance clarifying the agencies’ role in assessing data to improve the reliability of the data they report to ODNI. The guidance should require agencies to assess the characteristics, quality controls, and limitations of their data, using data reliability practices or principles, and address any gaps. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of National Intelligence should define, at each relevant agency, the senior data official’s role for assessing the reliability of the agency’s data, and ensure agencies have identified these accountable officials. (Recommendation 3)

The Director of National Intelligence should analyze and update, to the maximum extent practicable, ODNI’s personnel vetting policy framework to incorporate GAO’s key practices for evidence-building and performance-management activities and apply those practices in its oversight of the clearance process. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report for review and comment to DOD, the Department of Energy, the General Services Administration, the National Capital Planning Commission, ODNI, the Department of the Treasury, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Of these agencies, only ODNI provided comments on the report, which it sent via email. ODNI did not state whether it agreed or disagreed with our recommendations. The agency provided suggestions to revise three of our recommendations and commented on the fourth recommendation. Below, we summarize and respond to ODNI’s suggestions and comments.

In its emailed comments, ODNI suggested revising recommendation 1 to remove reference to our data reliability principles, noting that these principles are designed for auditors and that ODNI lacks the infrastructure or expertise to conduct audits. While ODNI is correct that we follow our principles to ensure we use reliable data to inform our audits, any agency that collects data can adapt and apply the principles in the guide for its own purpose. Furthermore, ODNI could incorporate data reliability practices or principles from other organizations that reflect a similar intent as our guide on data reliability. We revised our report to highlight another source of these practices and principles, DAMA International. We also revised our recommendation to acknowledge that ODNI should incorporate data reliability practices or principles—whether from our guide, DAMA International’s, or another, similar source—into a process to assess agency data.

For example, ODNI could incorporate our principle to interview knowledgeable officials about their data systems. Alternatively, ODNI could incorporate the DAMA International practice to develop and use business rules related to data quality (e.g., completeness, accuracy, and consistency of data) to assess agency data. Without incorporating data reliability practices or principles into its processes, ODNI does not have the assurance that the data it uses to oversee the clearance process are accurate and complete.

ODNI further suggested removing language from recommendation 2 that it ensure agencies adhere to ODNI-issued data reliability guidance. ODNI described two reasons for this suggestion. First, it stated that it does not have traditional enforcement abilities and uses a collaborative approach to encourage agency compliance with data reporting responsibilities. Second, it stated that ensuring such adherence would be difficult and resource intensive.

To the first point, as we describe in our report, as the Security Executive Agent, the DNI is responsible for overseeing the personnel security clearance process, including its quality, timeliness, consistency, and integrity. The Security Executive Agent is further required to review agencies’ programs to determine whether they are being implemented in accordance with Executive Order 13467. As such, it has the authority to issue guidelines and instructions to the heads of agencies. Such guidance can help ensure appropriate uniformity, centralization, efficiency, effectiveness, timeliness, and security in the personnel security clearance process. In carrying out these oversight responsibilities, ODNI should work with agencies to implement its guidance on security clearance data reliability.

To the second point, we recognize that it may be complicated for ODNI to ensure other federal agencies adhere to the data reliability guidance it issues. Therefore, we revised our recommendation to state that ODNI should monitor, rather than ensure, agencies’ adherence to such guidance.

With respect to recommendation 3, ODNI stated in its comments that departments and agencies are to identify Senior Implementation Officials responsible for implementing Trusted Workforce 2.0. ODNI also stated it could issue guidance to those officials regarding their agencies’ practices to ensure data are reliable. We believe these would be positive steps toward addressing our recommendation; however, ODNI would need to fully implement those steps before we can analyze their effectiveness.

Finally, ODNI suggested we remove specific reference to our key practices for evidence-building and performance-management activities in recommendation 4. ODNI stated that there is already a periodic review process under the Trusted Workforce 2.0 personnel vetting reform effort. We recognized this process in our report. However, as we also described in the report, ODNI has not effectively used a data-driven approach in its oversight activities. Incorporating our key practices into its oversight could help ODNI more effectively manage and assess the personnel security clearance process.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of National Intelligence, the Secretary of Defense, the DCSA Acting Director, the Secretary of Energy, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Acting Administrator of the General Services Administration, the Chair of the National Capital Planning Commission, and the Director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at czyza@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Alissa H. Czyz

Director

Defense Capabilities and Management

The objectives of this report were to evaluate the extent to which the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) (1) has reliable data to oversee the government-wide personnel security clearance process and (2) has used a data-driven approach to inform its oversight of the security clearance process.

For both objectives, we reviewed executive orders, guidance, and documents related to the personnel security clearance process, ODNI’s oversight, and the Trusted Workforce 2.0 reforms, including the following:

· Executive Order 13467, which specifies the oversight and reform responsibilities for the personnel security clearance process[56]

· Guidance issued by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) and the Director of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) on Trusted Workforce 2.0 to reform federal personnel vetting[57]

· ODNI guidance on data collection requirements and metrics reporting[58]

· ODNI Security Executive National Assessments Program (SNAP) guidance and requirements, such as metrics reporting requirements for national security vetting, best practices and interview guidance, and standard operating procedures[59]

· DNI and Director, OPM guidance on personnel vetting performance management standards and performance management implementation[60]

· Performance Accountability Council (PAC) documents on Trusted Workforce 2.0, including the Trusted Workforce 2.0 Implementation Strategy and Trusted Workforce 2.0 Quarterly Progress Reports[61]

· Prior GAO reports and reports by executive branch audit agencies[62]

· Federal and intelligence community standards and guidance on personnel vetting[63]

Analysis of the Reliability of ODNI’s Data on the Security Clearance Process

Agencies Selected to Review

For our first objective, we selected and analyzed the reliability of data ODNI collected from the following seven executive branch agencies:

· The Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA)

· The Department of Energy

· The Department of the Treasury

· The General Services Administration

· The National Capital Planning Commission

· The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

· The U.S. Agency for International Development

To select these seven agencies, we first obtained a list of about 100 agencies that conduct national security vetting and are thus required to report data on their security clearance process to ODNI. We then identified a nongeneralizable selection of seven agencies from this population. To do this, we considered multiple factors to obtain a cross-section of agencies to ensure a diverse set of perspectives. In particular, we selected agencies from various sectors of the executive branch including intelligence, nonintelligence, defense, and nondefense. We included a mix of cabinet-level departments and independent agencies. We also considered (1) whether an agency has the authority to conduct background investigations, according to ODNI, (2) whether an agency reported data to ODNI in a consistent format over time,[64] and (3) whether ODNI had recently identified that the agency is required to report data.[65]

Though our observations of data from our selection of agencies are not generalizable to all the agencies in the executive branch, these seven agencies are, collectively, required to submit security clearance data to ODNI for over 90 percent of all individuals with a clearance.[66]

Data Reporting Requirements and Statistics Analyzed

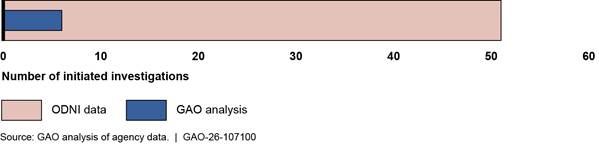

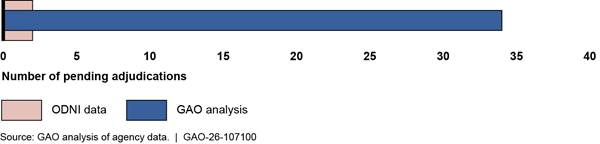

ODNI requires agencies to submit data quarterly in response to 39 reporting requirements related to the personnel security clearance process. We selected eight of the 39 reporting requirements to analyze. Although the eight reporting requirements are not generalizable, we selected these eight requirements because they address the key components of the clearance process relevant to all agencies. Additionally, ODNI will continue to require agencies to report them in response to new performance measures that take effect in October 2025.[67] Further, we collected and analyzed agencies’ quarterly data for the third quarter of fiscal year 2024, since these data were the most recently available at the time of our review.

ODNI requires agencies to provide a different number of summary statistics for each reporting requirement we analyzed. For instance, sometimes agencies are required to report multiple statistics for one reporting requirement to distinguish between employee types (government or contractor) and clearance types (Secret or Top Secret, initial or reinvestigation). In other instances, ODNI requires agencies to report one statistic, such as an average. See table 2 for the eight reporting requirements we selected and the number of statistics corresponding to each requirement.

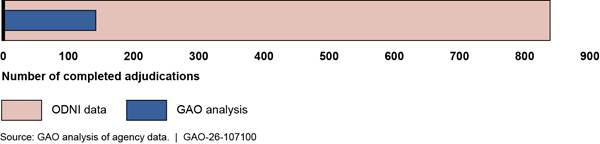

|

Reporting requirement |

Number of statistics analyzed |

|

Timeliness |

6 |

|

National security population |

4 |

|

Initiated investigations |

8 |

|

Pending adjudications |

8 |

|

Completed adjudications |

16 |

|

Reciprocity |

1 |

|

Average time to validate a continuous vetting alert |

1 |

|

Average time to remove an individual from access |

1 |

|

Total |

45 |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107100

Selection of Statistics

For five of the eight reporting requirements we selected, we analyzed all the statistics agencies are required to report to ODNI. For the remaining three requirements, we selected a nongeneralizable subset of the statistics to analyze. These three requirements were timeliness, national security population, and reciprocity.

· Timeliness. ODNI collects timeliness data from agencies in two formats: summary data and case-level data. Summary data are the total number of days and cases. For example, an agency might report completing investigations for 25 Top Secret clearances in a quarter, and combined, the agency took 2,000 days to complete all those investigations. Case-level data are raw data for each clearance including start and end dates for each phase. DCSA provides summary timeliness data to ODNI for Department of Defense (DOD) components and the agencies that obtain investigative services from DCSA. Similarly, five IC elements provide summary data to ODNI: the Central Intelligence Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigations, the National Security Agency, and the National Reconnaissance Office. The remaining agencies that conduct investigations provide case-level data to ODNI.

ODNI then uses both data formats to calculate the average times for agencies to complete the clearance process. ODNI uses these statistics in timeliness performance reports it sends to agencies each quarter. These timeliness performance reports include statistics on each agency’s average time to complete the fastest 90 percent of cases in the clearance process, categorized by clearance type, and phase of the process. ODNI shares these performance reports with agencies and asks agencies that did not meet timeliness goals to determine why and develop a plan to address gaps in performance. Data from these performance reports are also used in the Security, Suitability, and Credentialing Performance Accountability Council’s (PAC) quarterly performance updates on the Trusted Workforce 2.0 reform, according to ODNI officials.

We selected a nongeneralizable set of six statistics from these timeliness reports to analyze. These statistics cover a range of aspects from the initiation, investigation, and adjudication phases of the clearance processes for both initial clearances and periodic reinvestigations. Whenever possible, we included statistics for both Secret and Top Secret clearances.

· National security population. ODNI requires agencies to submit 25 statistics on their national security population. We selected a nongeneralizable set of four statistics that ODNI requires agencies to report in two separate locations of its data collection tool. ODNI requires agencies to report the same statistics in both locations. These four statistics were the total populations of (1) government employees with a Secret clearance, (2) government employees with a Top Secret clearance, (3) contractor employees with a Secret clearance, and (4) contractor employees with a Top Secret clearance.

· Reciprocity. ODNI requires agencies to submit case-level data for each reciprocal clearance the agency accepted or rejected during the quarter. To analyze reciprocity data, we analyzed one statistic. In particular, we compared the total number of cases agencies reported to ODNI with the total number of cases reflected in the agency’s case-level data.

Statistics Selection Limitations and Mitigations

We attempted to analyze each of the 45 statistics we selected for each of the seven agencies we reviewed. We analyzed all 45 statistics for three of the seven agencies we selected to review: the Department of the Treasury, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. However, four of the seven agencies were unable to provide case-level data to support some of the statistics we selected. Specifically:

· DCSA. We analyzed 43 of the 45 statistics for DCSA. We analyzed additional timeliness statistics but removed statistics on initiated investigations. Specifically, we analyzed 12 timeliness statistics, twice the number of statistics we analyzed for the other six agencies we reviewed. We expanded our scope because ODNI provides multiple timeliness performance reports for DOD components and other groups, such as DOD industry and DOD agencies. We selected these two groups, DOD industry and DOD agencies, as DCSA officials indicated their case-level data was the most accurate. With the additional timeliness statistics, we would have analyzed 51 statistics for DCSA. However, we could not analyze eight statistics on initiated investigations because DCSA could not provide the necessary case-level data for our analysis.

· Department of Energy. We analyzed 44 of the 45 statistics for the Department of Energy. We were unable to analyze the one reciprocity statistic from this agency because some of the agency’s data were classified, and we did not include classified data in the scope of our review.

· General Services Administration. We analyzed 44 of 45 statistics for the General Services Administration. The agency was unable to provide case-level data to support one statistic reported for the average time to adjudicate a continuous vetting alert.

· The National Capital Planning Commission. We analyzed 39 of 45 statistics for the National Capital Planning Commission. We did not analyze the six timeliness statistics for this agency. DCSA completes investigations for the agency and DCSA officials stated the agency did not initiate any investigations in the quarter and therefore did not have any timeliness data to report.

In total, we analyzed 305 of 315 statistics across all seven agencies we selected for our review.

Analysis of Agency Data

We analyzed the accuracy, completeness, and, in some instances, consistency of the data ODNI collected from executive branch agencies we selected for review.[68]

Accuracy. To evaluate the accuracy of the statistics for seven of the reporting requirements, we used agencies’ case-level data to calculate summary statistics that corresponded to the requirements for statistics we selected for analysis, and compared the results to the following:[69]

· Agency-calculated statistics. Agencies calculate summary statistics from their case-level data, which are either totals or averages, and submit them to ODNI for six out of the eight reporting requirements we reviewed—initiated investigations, pending adjudications, completed adjudications, reciprocity, and both averages related to continuous vetting alerts.

· ODNI-calculated statistics. Agencies submit data on timeliness to ODNI. Using the data, ODNI calculates summary statistics, compares them to timeliness goals, and reports this analysis to agencies. If the agency uses DCSA for investigative services, DCSA calculates these statistics, and ODNI reports them.

For the eighth reporting requirement on national security population, ODNI requires agencies to report the same information in two separate fields in its data collection tool. To evaluate the accuracy of these statistics, we compared the agencies’ two responses in these separate fields.

We also analyzed the extent that statistics were inaccurate. For seven of the reporting requirements, we determined the extent of inaccuracies by comparing a summary statistic we calculated using the agencies’ case-level data to the agency-calculated statistic. However, we were not able to identify which statistic was accurate, if either. Therefore, we

1. calculated the average of the two statistics we compared,

2. calculated the difference between these two statistics,

3. divided the difference by the average, and

4. multiplied this result by 100.

For example, the Department of Energy reported adjudicating 28 government Secret reinvestigations, but our analysis of the agency’s case-level data found 53 of these reinvestigations. The average of the two statistics is 40.5 and the difference is 25. We divided the difference of 25 by the average of 40.5 and multiplied this result by 100 (i.e., [(25/40.5)*100]) to conclude that this statistic was inaccurate by 62 percent.

For the eighth reporting requirement on timeliness, we determined the extent of inaccuracy using a similar process. However, when comparing the statistics we calculated using case-level data to ODNI-calculated statistics, we were able to identify that the statistics we calculated were correct. Therefore, we

1. calculated the difference between ODNI’s statistic and the one we calculated,

2. divided the difference by our statistic, and

3. multiplied this result by 100.

For example, ODNI reported that the General Services Administration’s average adjudication time for the fastest 90 percent of cases was 8 days, but our analysis of the agency’s case-level data found that it was 14 days. The difference between these statistics is six. We divided the difference by our calculated statistic and multiplied this result by 100 (i.e., [(6/14)*100] to conclude that this statistic was inaccurate by 43 percent.

Completeness. To analyze the completeness of agencies’ data, we observed instances when agencies did not provide a required statistic.

Consistency. To analyze the consistency of the data, we reviewed whether agencies calculated statistics using definitions and methods that aligned with ODNI’s guidance. However, we did not examine the consistency of all eight reporting requirements we selected to analyze. Instead, we noted cases where agency officials described measurement or calculation methods that were inconsistent with ODNI’s guidance. When we found an agency used an incorrect or inconsistent definition or method, we did not systematically assess whether all other agencies we selected for review used similarly incorrect or inconsistent definitions or methods. Therefore, we present our findings about inconsistencies as examples related to data inaccuracies.

Analysis of Agency Data Reliability Controls, ODNI Guidance, and Internal Controls

In addition to this data analysis, we assessed agency controls by interviewing knowledgeable officials from ODNI and six of the seven agencies we selected for our review about the controls they have in place to ensure the reliability of the agencies’ data.[70]

Also, we conducted a content analysis on guidance ODNI recently issued that officials said was designed to ensure that the data it receives are reliable. We compared the guidance documents to the key principles for data reliability from our 2019 report on assessing data reliability.[71] To complete the analysis, a GAO analyst reviewed each guidance document to determine the extent to which it incorporated each of the data reliability key principles and assigned a score of generally incorporated, partially incorporated, or not incorporated. A second GAO analyst also assessed the guidance and assigned a score using the same criteria. If the two analysts disagreed on a rating, they met, discussed evidence for their determination, and reached concurrence on a final rating. See appendix IV for more information about this analysis.

We also compared ODNI actions related to data it used to oversee the security clearance process to guidance on ensuring high-quality data. We relied on the principle established in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government that management should use quality information to achieve its objectives. We further relied on memorandums from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and ODNI stating, respectively, that (1) the value of data hinges on the reliability, validity, and overall quality of data, and (2) to assure the quality, consistency, and integrity of the national security vetting process, standardized, consistent metrics are vital.[72]

Analysis of Extent to Which ODNI Followed Key Evidence-Building and Performance-Management Practices in Its Security Clearance Process Oversight

For our second objective, we defined a data-driven approach to oversight as one that effectively builds and uses evidence—including performance information and statistical data—to manage performance as part of oversight. To determine how ODNI builds and uses evidence as part of its clearance process oversight, we compared evidence related to ODNI’s oversight of the personnel security clearance process to our key practices on evidence building and performance management.[73]

While we focused our analysis on ODNI actions to oversee the personnel security clearance process specifically, much of the evidence we reviewed was prepared jointly by ODNI and OPM or the PAC and related to personnel vetting more broadly. This included evidence on the personnel security clearance process as well as the suitability, fitness, and credentialing processes. We considered any evidence related to broader personnel vetting efforts if the personnel security clearance process was subject to the actions indicated in the evidence.

We met with ODNI officials to share our preliminary observations, obtain testimonial evidence in instances when we had not found documentary evidence corresponding to the criteria, and obtain their perspectives on our assessment and reasons why ODNI did not fully follow certain key practices, as applicable. We used our analysis of the documentary and testimonial evidence from ODNI to determine the extent to which ODNI had followed each of the 13 key practices and 29 supporting key actions in its oversight of personnel security clearance processes.

To complete our analysis, two analysts reviewed and assessed documentation and testimonial evidence of ODNI’s efforts to oversee the clearance process using the key practices and, using a scorecard methodology, determined whether ODNI generally implemented, partially implemented, or did not implement each of the 29 supporting key actions. For supporting actions we assessed as “generally implemented,” we determined that ODNI had taken steps that covered all aspects of the supporting action. For supporting actions we assessed as “partially implemented,” we determined that ODNI had taken some steps or had implemented the action but only for a specific aspect of the personnel security clearance process. For supporting actions we assessed as “did not implement,” we determined that ODNI had not taken steps to implement the supporting action.

Where ODNI had generally implemented all supporting actions for a key practice, we determined that it had generally followed the key practice. Where ODNI had partially implemented supporting actions or had a mix of implementing some actions and not others, we determined that it had partially followed the key practice. Where ODNI had not implemented the supporting actions of a key practice, we determined that it had not followed the practice.