TRIBAL PROGRAMS

Information on Freedmen Descendants of the Five Tribes

Report to the Committee on Indian Affairs, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Indian Affairs, U.S. Senate.

For more information, contact: Anna Maria Ortiz at ortiza@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Before the Civil War, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations—known as the Five Tribes—had citizens who enslaved people. In 1866, each Tribe entered a treaty with the U.S. that abolished slavery and addressed tribal citizenship rights of the formerly enslaved people living among the Tribes. Historically, these people are referred to as “Freedmen.”

GAO estimates that the population of descendants of the Freedmen could have ranged from 146,400 to 395,400 in 2022. Since the 1800s, several courts have considered whether the Freedmen and their descendants are entitled to tribal citizenship or other rights under the 1866 treaties. In part because of those cases, Freedmen descendants are eligible to enroll as tribal citizens in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations, but not the Chickasaw or Choctaw Nations. Further, the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court recently ruled that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation must begin to permit its Freedmen descendants to enroll.

Federal agencies administer a range of services, such as health care, education, and housing assistance, for the benefit of Tribes and their citizens, including enrolled Freedmen descendants. However, most of the 19 enrolled Freedmen descendants GAO interviewed said they encountered barriers accessing such services. Agencies have taken some actions to address these barriers, such as by clarifying enrollment eligibility. In addition, enrolled Freedmen descendants are regarded differently than other tribal citizens under certain federal statutes concerning land ownership and criminal jurisdiction.

Why GAO Did This Study

To better understand the status of Freedmen descendants, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs held a hearing in 2022 on selected provisions of the 1866 treaties between the U.S. and the Five Tribes. The committee subsequently requested that GAO provide related information.

This report (1) estimates the population of Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes, (2) describes key court decisions on Freedmen descendants’ eligibility for tribal citizenship, (3) describes barriers to certain federal services identified by enrolled Freedmen descendants and agency actions to address them, and (4) describes how Freedmen descendants are regarded differently than other citizens of the Five Tribes under certain federal statutes.

GAO conducted demographic modeling to estimate the population of Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes as of 2022, the most recent year for which data were available.

GAO reviewed the 1866 treaties, the Five Tribes’ constitutions, federal statutes, and key court cases from tribal and federal courts related to the tribal citizenship rights of the Freedmen descendants.

GAO interviewed officials from the Cherokee Nation, an association that represents Freedmen descendants, 19 Freedmen descendants enrolled as tribal citizens in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations, and federal agency officials.

Abbreviations

|

BIA |

Bureau of Indian Affairs |

|

BIE |

Bureau of Indian Education |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CDIB |

Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HUD |

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

IHS |

Indian Health Service |

|

Interior |

Department of the Interior |

|

NAHASDA |

Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996, as amended |

|

VSUS |

Vital Statistics of the United States |

|

WONDER |

Wide-ranging ONline Data for Epidemiologic Research |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 15, 2025

The Honorable Lisa Murkowski

Chairman

The Honorable Brian Schatz

Vice Chairman

Committee on Indian Affairs

United States Senate

In the 1830s, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations, collectively known as the Five Tribes, were forcibly relocated from the southeastern United States to land that makes up present-day Oklahoma.[1] At that time, the Five Tribes had citizens who enslaved people of African descent. The forced displacement is known as the “Trail of Tears,” and both the Tribes and the enslaved people were forced to make the devastating journey.[2] In 1866, following the Civil War, each of the Five Tribes entered a Treaty with the United States that abolished slavery within the Tribe.[3] Each Treaty also addressed the tribal citizenship rights of the formerly enslaved people and people of African descent living among the Tribes following the war.

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States undertook a broad effort to break up tribal lands, allot parcels to individual tribal citizens, and sell lands that were not allotted to white settlers. At that time, in preparation for allotment, Congress directed a commission to create lists of the Five Tribes’ citizens “by blood” and “Freedmen”—the formerly enslaved people and people of African descent living among the Tribes who might be entitled to tribal citizenship or other rights under the 1866 treaties.[4] The resulting lists are referred to as the Dawes Rolls and are the base rolls for each of the Five Tribes today. For purposes of this report, Freedmen refers to people on the Freedmen lists of the Dawes Rolls and “Freedmen descendants” refers to people whose ties to one of the Five Tribes are based only on their lineal descent from a person or people listed as Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls.[5]

In the years following the 1866 treaties and subsequent allotment, four of the Tribes—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations—permitted the Freedmen and their descendants to enroll as tribal citizens (the Chickasaw Nation never formally enrolled Freedmen in the Tribe). However, beginning in the 1970s, the four Tribes that had afforded the Freedmen and their descendants tribal citizenship adopted new tribal constitutions that limited or attempted to limit tribal citizenship rights for Freedmen descendants. Today, Freedmen descendants are permitted to enroll as tribal citizens in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations, but not in the Chickasaw or Choctaw Nations. Until recently, Freedmen descendants were likewise ineligible for citizenship in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. However, in July 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Supreme Court found that the relevant 1866 Treaty guaranteed the Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen and their descendants the right to tribal citizenship and that references to “by blood” citizenship in the Tribe’s Constitution were unlawful and void.[6] The Court directed the Muscogee (Creek) Citizenship Board to apply the 1866 Treaty and issue citizenship to any future applicants of Freedmen descent; however, as of November 2025, Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen descendants’ ability to obtain tribal citizenship was an evolving matter.[7]

There have been long-standing disputes over the tribal citizenship rights of the Freedmen descendants in the Five Tribes.[8] Tribal and federal courts have considered the extent to which Freedmen descendants are entitled to tribal citizenship under several of the 1866 treaties with the United States. Some of the Five Tribes have asserted that they are not required to allow the Freedmen or their descendants to enroll as tribal citizens. By contrast, some Freedmen and their descendants have asserted that they are entitled to tribal citizenship rights under the 1866 treaties. In some cases, Freedmen and their descendants have filed litigation aimed at determining their eligibility for tribal citizenship.

The United States has undertaken a unique trust responsibility to support and protect Tribes and their citizens through statutes, treaties, and historical relations.[9] Additionally, as part of the government-to-government relationship with Tribes, Congress has authorized provision of certain services to Tribes and their citizens. For example, tribal citizens, including those in the Five Tribes, may have access to certain federal services and programs—such as health care, housing assistance, and education—because of their status as tribal citizens. Federal agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the Department of the Interior administer some of these services.

To help better understand the status of Freedmen descendants in the Five Tribes, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs held a hearing in July 2022 on selected provisions of the 1866 treaties between the United States and the Five Tribes. In response to this hearing, the committee requested that we provide related information. In this report we (1) estimate the population of Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes; (2) describe key court cases regarding Freedmen descendants’ citizenship rights in the Five Tribes since the 1866 treaties; (3) describe barriers that Freedmen descendants enrolled as tribal citizens have faced when accessing federal services and funds, and steps federal agencies have taken to address such barriers; and (4) describe how specific federal statutes and judicial interpretations have led to enrolled Freedmen descendants being regarded differently than other tribal citizens.

To estimate the population size of Freedmen descendants, we developed a demographic model that simulated how the population of Freedmen and their descendants may have changed over time since 1907, given historical birth and death rates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a starting point, we used lists of the Freedmen of the Five Tribes compiled from 1898 to 1907, which are part of The Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory, typically referred to as the Dawes Rolls. There are long-standing concerns about how the Dawes Rolls were compiled.[10] Nonetheless, these rolls are the base rolls for the Five Tribes and the Freedmen according to the U.S. government and are also the primary source the Five Tribes use in establishing eligibility for enrollment today. We ended our analysis in 2022, which was the most recent year with data available for all model inputs, given a starting year of 1907 and fixed 5-year intervals.

We obtained electronic database copies of the Dawes Rolls from the Oklahoma Historical Society and a commercial vendor.[11] To assess the reliability of these databases, we compared the number of unique people between sources. We consulted with two independent external subject matter experts who have extensive experience in the history and genealogy of the Freedmen population; and two independent internal reviewers with expertise in demography and vital statistics to ensure that the analysis and estimates are reliable for our purposes. Appendix I describes our analysis and modeling in more detail.

For key court cases regarding Freedmen descendants’ tribal citizenship rights, we reviewed the 1866 treaties between the United States and each of the Five Tribes to identify those portions of the treaties that address the status of the Freedmen and their descendants in the Tribes. We also reviewed the constitutions for each of the Five Tribes to identify the extent to which each Tribe extends tribal citizenship rights to its Freedmen descendants. Finally, we researched and reviewed court cases from tribal and federal courts that pertain to the status of Freedmen descendants within the Five Tribes and provide relevant historical context for how the Five Tribes have regarded their Freedmen descendants since the 1866 treaties.

We report on the key cases that directly address the Freedmen descendants’ citizenship rights in the Five Tribes or provide relevant information about how courts may consider questions regarding these rights, and that have not been overturned or challenged by subsequent case law.[12] To verify our selection of key cases, we reviewed scholarly articles and discussed the identified cases with officials from Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Department of Justice to ensure we covered the most relevant cases. Courts are the appropriate entities to consider the legal questions regarding what the 1866 treaties require with respect to the Freedmen and their descendants, and thus we do not offer an independent legal opinion on what rights the 1866 treaties may or may not guarantee to the Freedmen descendants. Appendix II includes details on the relevant provisions of the 1866 treaties and key court cases that pertain to the status of Freedmen descendants in each of the Five Tribes.

To identify barriers and relevant statutes, we conducted a comprehensive literature search of academic, governmental, and other sources issued from 2003 through 2024 to identify (1) examples of barriers enrolled Freedmen descendants had to accessing federal services and (2) examples of how enrolled Freedmen descendants are regarded differently than other tribal citizens under certain federal statutes.[13] In addition, we met with an association that represents Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes to help identify selected individuals who had encountered such barriers to interview.

We relied on non-generalizable snowball sampling to select and interview enrolled Freedmen descendants who expressed concerns about their ability to access certain federal services or being treated differently than other tribal citizens under federal law. We asked them about their experiences accessing federal services from 2017 through 2024.[14] The information we obtained from the enrolled Freedmen descendants we interviewed is illustrative of barriers they experienced and is not generalizable to other enrolled Freedmen descendants or Tribes. We interviewed a total of 19 Freedmen descendants (12 Cherokee citizens and seven Seminole citizens).[15]

We reviewed policies, procedures, and guidance provided by the federal agencies primarily responsible for administering the relevant federal programs and services, including HHS’s Indian Health Service (IHS), Interior’s BIA and Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), HUD’s Office of Native American Programs, and the Department of Justice. We interviewed agency officials about the reported barriers to receiving federal services described by Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee or Seminole Nations and steps their respective agencies have taken to address those barriers. We also analyzed specific federal statutes to determine how those statutes, or judicial interpretations of those statutes, regard enrolled Freedmen descendants differently from other tribal citizens and interviewed agency officials about what we learned.

While the focus of our review was federal programs, services, and statutes, we reached out to the Five Tribes and requested meetings with officials from each Tribe to obtain their perspectives. Of the Five Tribes, officials from the Cherokee Nation met with us to share information and perspectives.[16]

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The history of the Five Tribes, the Freedmen and their descendants, and their relationship with the United States is part of the larger context of the federal government’s approach to Tribes over the course of our country’s existence. We summarize some of that history and relevant context below.

The Five Tribes During the Early History of the United States

In the years following the Revolutionary War, the Five Tribes occupied portions of the southeastern United States. As the United States expanded further into this region in the early 1800s, pressure from American settlers led to a federal policy focused on removing Tribes from the eastern United States and relocating them on western lands. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed, authorizing the President to relocate Tribes to certain territory west of the Mississippi River.[17] As a result, the Five Tribes and the enslaved and free people of African descent living among them were forcibly relocated to land that is present-day Oklahoma through what has come to be known as the Trail of Tears.

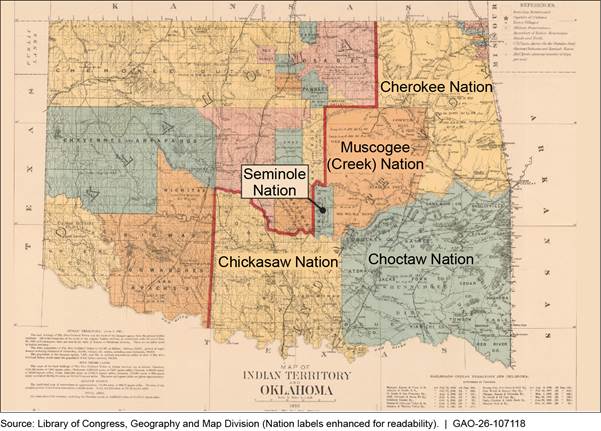

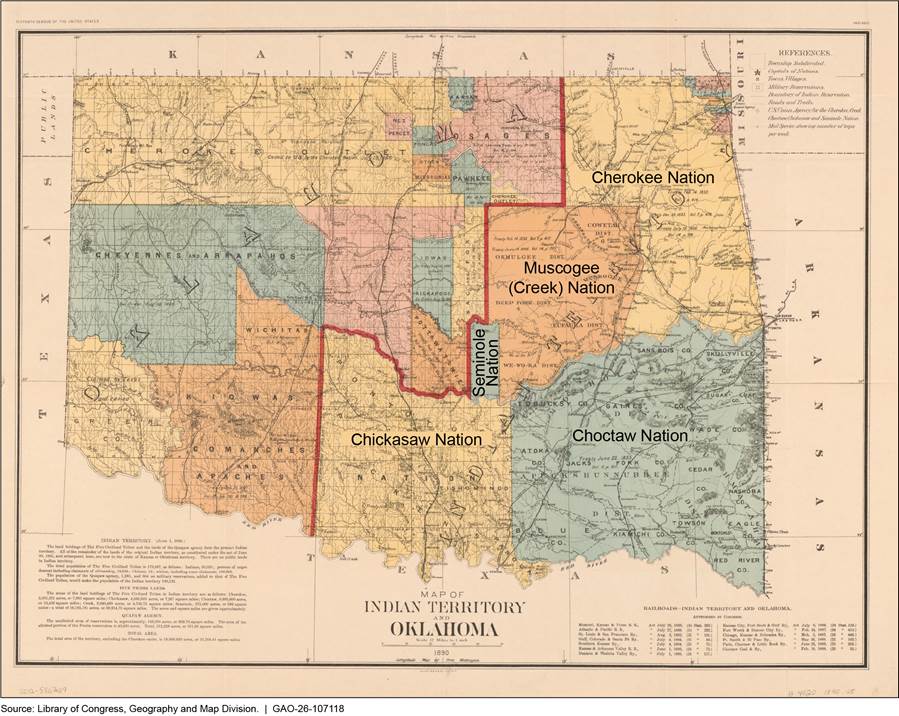

By the mid-1800s, federal policy toward Tribes had shifted from removal to placement on fixed reservations. During this period, the federal government often entered treaties with Tribes to, for example, establish peace, fix land boundaries, and establish reservations. As previously noted, in 1866, following the Civil War, each of the Five Tribes entered a treaty with the United States that—among other things—abolished slavery within the Tribe and addressed the status of Freedmen in that Tribe. By 1890, the Five Tribes had territories along the eastern side of present-day Oklahoma, as shown in figure 1.

Note: GAO made minor edits to the above image to improve readability of some labels.

The Dawes Commission and the Dawes Rolls

By the late 19th century, American settlers increasingly sought access to western lands held by Tribes. Accordingly, in 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act—or Dawes Act—which began a policy under which the government divided tribal lands into allotments for individual tribal citizens and, in many cases, land that was not allotted was sold to settlers for homesteading.[18]

The Five Tribes were initially exempt from the Dawes Act, but in 1893, Congress created a commission—known as the Dawes Commission—to negotiate with the Five Tribes for the allotment of their communal lands in preparation for the creation of a new state—Oklahoma. The Five Tribes resisted allotment, and in 1898, Congress passed the Curtis Act, which provided for forced allotment of the Five Tribes’ communal land without tribal consent.[19] The Curtis Act transferred the authority to determine tribal citizenship to the Dawes Commission and authorized it to compile citizenship rolls—known as the Dawes Rolls—for each of the Five Tribes as a basis for forced allotment.

The Dawes Commission prepared rolls for the Five Tribes starting in 1898 and ending in 1907.[20] For each Tribe, the Dawes Rolls have categories of people identified as having a degree of “Indian blood” (referred to as “by blood”) and people identified as formerly enslaved (the Freedmen) who are referred to as having no “Indian blood.”[21] In general, the Dawes Rolls list individuals who lived with the Tribes in Indian Territory, chose to apply to the Dawes Commission, and were approved by the Dawes Commission.

The process of enrollment used by the Dawes Commission for the Dawes Rolls raised some concerns among the Tribes and the Freedmen, according to Oklahoma Historical Society documents. For example, concerns arose because the Dawes Commission had the authority to enroll people not already included on existing tribal rolls and records. In addition, the enrollment process put the burden of proof on the applicants and some people chose not to participate. Furthermore, according to Oklahoma Historical Society documents, some people with interest in acquiring allotted land allegedly engaged in bribery to be included on the rolls. However, today, the Dawes Rolls are considered the base roll for each of the Five Tribes by the U.S. government and the Tribes.

The Five Tribes Today

Today, the Five Tribes remain located in Oklahoma. Each Tribe has its own elected government, a governing constitution, and process for enrollment of tribal citizens.[22] For each Tribe, the Dawes Rolls remain the basis for enrolling tribal citizens. Therefore, only those who can trace their lineage back to someone whose name appears on the Dawes Rolls may be eligible for citizenship in one of the Five Tribes. In 2024, the Tribes reported the following enrollment information:

· Cherokee Nation, approximately 468,600 people

· Chickasaw Nation, approximately 81,500 people

· Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, approximately 225,000 people

· Muscogee (Creek) Nation, approximately 102,000 people

·

Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, approximately 18,800 people[23]

Freedmen of the Five Tribes and Their Descendants

In the years following the 1866 treaties, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations granted tribal citizenship rights to Freedmen. The Chickasaw Nation, by comparison, never formally enrolled Freedmen in the Tribe. The Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations continued to grant tribal citizenship rights to Freedmen and their descendants for a period of time after enrollment on the Dawes Rolls closed. However, starting in the 1970s, these Tribes undertook several efforts to limit tribal citizenship solely to those descended from the “by blood” individuals on the Dawes Rolls, thereby making Freedmen descendants ineligible for tribal citizenship in some of the Five Tribes.

The Freedmen and their descendants’ tribal citizenship rights—or lack thereof—have been the subject of litigation since shortly after the 1866 treaties. Some Freedmen and their descendants have claimed that they are entitled to tribal citizenship rights under the 1866 treaties, and many federal and tribal courts have considered questions regarding Freedmen descendants’ rights to citizenship in the Five Tribes. Today, partly as a result of that litigation, Freedmen descendants are eligible for tribal citizenship in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations, but they are not eligible for tribal citizenship in the Chickasaw or Choctaw Nations. Until recently, Freedmen descendants were also ineligible for tribal citizenship in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. However, as noted above, in July 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court ruled that the Tribe’s Freedmen descendants are entitled to tribal citizenship. As of November 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had not enrolled any of the Tribe’s Freedmen descendants.

Today, enrolled Cherokee Freedmen descendants live primarily in Oklahoma, and have large populations located in Kansas and Texas.[24] According to some of the Freedmen descendants we interviewed, being a tribal citizen is an important part of their identity and their tribal identity is important because it allows them to preserve Freedmen history and culture and educate future generations about the challenges they endured.

The United States’ Relationship with Federally Recognized Tribes

As of December 2024, the federal government recognized 574 Indian Tribes—including the Five Tribes—as distinct, independent political entities whose inherent sovereignty predates the United States but has been limited in certain circumstances by treaty and federal law. The United States maintains a government-to-government relationship with these Tribes. In addition, Congress has broad legislative authority over issues related to federally recognized Tribes. However, federally recognized Tribes, such as the Five Tribes, generally have the authority to establish their own tribal constitutions, which can include criteria for citizenship in the Tribes. While some Tribes’ citizenship criteria are subject to requirements in federal law or treaty, criteria for tribal citizenship are generally determined and set by individual Tribes.

The United States has undertaken a unique trust responsibility to protect and support federally recognized Tribes and their citizens through statutes, treaties, and historical relations.[25] Additionally, as part of the government-to-government relationship with Tribes, Congress has authorized certain federal agencies to provide various services and benefits to Tribes and their citizens. For example, the following federal agencies provide direct services or funding to Tribes or tribal citizens: HHS’s IHS, HUD’s Office of Native American Programs, and Interior’s BIA and BIE. These services include federally funded or operated facilities that provide health care services, housing assistance through federal grant programs, and education services through federally funded schools. In addition, each of the Five Tribes has entered into self-determination contracts or self-governance compacts with the United States that transfer administration of some federal programs to the Tribes.[26]

To be eligible for certain federal programs, benefits, and services, an individual must meet the relevant legal definition of “Indian.” However, these programs and benefits arise under different authorities, and there is no single definition of who qualifies as an “Indian” under federal law. For certain programs, being a citizen of a federally recognized Tribe is sufficient for an individual to qualify. However, in other circumstances an individual must possess “Indian blood” to qualify as an “Indian” under federal law.

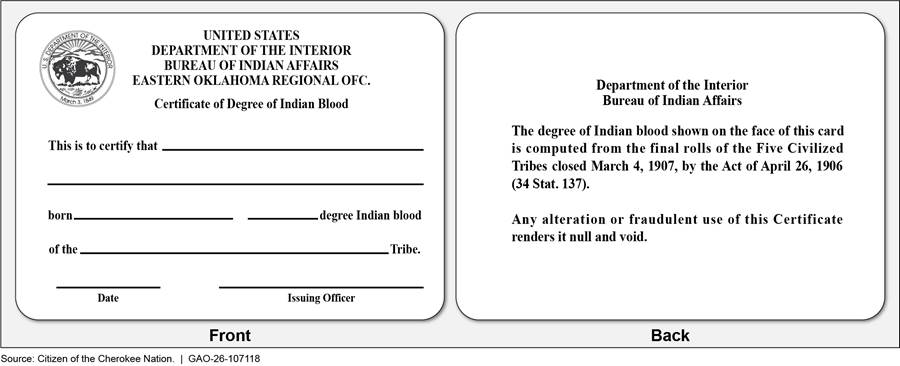

A Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) card is an official document from Interior’s BIA that certifies that an individual has a specific degree of “Indian” or Alaska Native blood of a federally recognized Tribe. An individual’s degree of Indian blood is computed from lineal ancestors of Indian blood who were enrolled with a federally recognized Tribe or whose names appear on the designated base rolls of a federally recognized Tribe. The term “Indian blood” was used by the Dawes Commission in the creation of the Dawes Rolls for the Five Tribes in the early 1900s, and the Dawes Rolls are still used as the base rolls for issuing CDIB cards for the Five Tribes. The Dawes Rolls did not record “Indian blood” for the Freedmen, and therefore Freedmen descendants are ineligible for a CDIB card. However, enrolled Freedmen descendants in both the Cherokee and Seminole Nations are issued tribal identification cards by the Tribes. Figure 2 shows an example of a CDIB card.

Figure 2: Example of a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) Card Issued by Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs

Note: GAO edited this figure to redact personally identifiable information.

Population of Freedmen Descendants of the Five Tribes Estimated to Have Ranged from 146,400 to 395,400 in 2022

Using a demographic model that we developed, we estimate that the population of Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes could have ranged from 146,400 to 395,400 in 2022, which was the year of the most recent data available at the time of our analysis.[27] The broad range in our estimate reflects the uncertainty in estimating a population that has not been counted or measured in detail since 1907, including their rates of birth and death, their migration to locations beyond Oklahoma, and their fertility within and outside the descendant population.

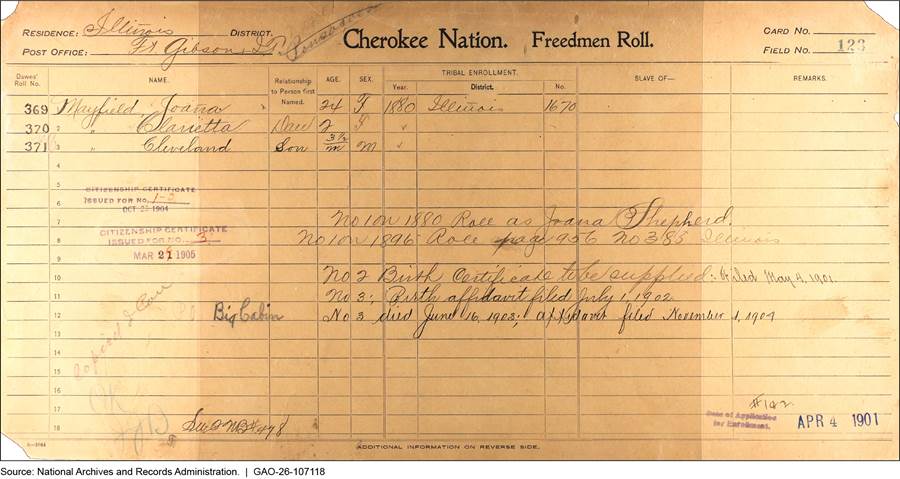

Our demographic model is based on the Dawes Rolls as the starting population, which listed 23,599 Freedmen in 1907.[28] All Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls had an enrollment card that recorded the applicant’s name, age, and sex, among other information. This information makes estimating the population of Freedmen descendants in 2022 possible. Figure 3 shows an example of an enrollment card from the Cherokee Nation’s Freedmen Rolls from 1901.

Our model applied historical birth and death rates from 1907 through 2022 to the data on Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls.[29] Due to the limited availability of historical data and uncertainty in how the population changed over time, we made assumptions about which of the historical data best represented Freedmen and their descendants, and confirmed these assumptions with two subject matter experts who have extensive experience in genealogy of Freedmen populations. We modeled various possible scenarios, based on these assumptions, for how the population may have changed over time, and the range—the high and low estimates—reflects how the population size estimates varied based on these assumptions. Table 1 shows the size of the Freedmen population from the Dawes Rolls in 1907 compared with our estimated population size of Freedmen descendants in 2022, based on birth and death rates across the period. We present population estimates for each of the Five Tribes separately and combined. Appendix I describes our analysis and modeling in more detail.

|

|

|

Freedmen descendants population estimated, rounded, 2022 |

|

|

Tribe |

Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls, actual counts, 1907 |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|

Cherokee Nation |

4,948 |

30,200 |

81,700 |

|

Chickasaw Nation |

4,778 |

29,400 |

79,400 |

|

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma |

6,080 |

37,200 |

100,400 |

|

Muscogee (Creek) Nation |

6,777 |

43,500 |

117,300 |

|

Seminole Nation of Oklahoma |

1,016 |

6,200 |

16,700 |

|

Total |

23,599 |

146,400 |

395,400 |

Source: GAO demographic modeling from an analysis of the

Dawes Rolls. | GAO‑26‑107118

Note: The Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory, which are typically referred to as the Dawes Rolls, were compiled by a commission of the U.S. government between 1898 and 1907. The Dawes Rolls are the base rolls for each of the Five Tribes. The low and high range of the estimates reflects uncertainty about births, deaths, migration, and other factors needed for demographic modeling. The intervals reflect how our population size estimates varied, when we assumed various possible scenarios for how the population may have changed over time. Due to rounding, estimate totals may not reflect the sum of the population as presented.

Our estimates do not represent the total population of people who

· may identify as Freedmen descendants, because our estimates are based on people who could trace lineage back to the Dawes Rolls;

· may choose to apply for enrollment in a Tribe if the Freedmen descendants are eligible for enrollment;

· may prove lineage to be accepted into a Tribe as Freedmen descendants; or

· are entitled to federal services or benefits because such entitlement is based on the specific requirements of the relevant federal programs.

Nevertheless, our estimates provide Congress, Tribes, and Freedmen descendants with information that may be useful in understanding the current magnitude of this population.

Court Decisions About Freedmen Descendants’ Rights to Tribal Citizenship Under the 1866 Treaties Vary by Tribe

Several tribal and federal courts have considered whether the Freedmen and their descendants are entitled to tribal citizenship in the Five Tribes and concluded that while some of the 1866 treaties guarantee the Freedmen descendants tribal citizenship rights in the relevant Tribe, others do not. Based in part on those court decisions, Freedmen descendants are currently eligible for tribal citizenship in the Cherokee Nation and the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma; they are not eligible for tribal citizenship in the Chickasaw or Choctaw Nations. As noted above, until recently, the Freedmen descendants were also ineligible for citizenship in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, but, in July 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Supreme Court held that the relevant 1866 Treaty guarantees the Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen descendants the right to tribal citizenship. Nonetheless, the ability of Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen descendants to obtain tribal citizenship was an evolving matter as of November 2025.

Below, we summarize each of the Five Tribes’ criteria for tribal citizenship and some of the relevant case law for each Tribe. In addition, appendix II includes details on the relevant provisions of the 1866 treaties and key court cases that pertain to the status of Freedmen descendants in each of the Five Tribes.

Cherokee Nation. Under the Cherokee Nation Constitution, Freedmen descendants are eligible for enrollment in the Cherokee Nation. In 2017, a federal court held that descendants of Cherokee Freedmen are entitled to the same citizenship rights as “by blood” Cherokees under the relevant 1866 Treaty.[30] In 2021, the Supreme Court of the Cherokee Nation ordered the Tribe to remove any reference to “by blood” citizenship from its Constitution, laws, rules, regulations, policies, and procedures.[31]

As of November 2025, “Article IV. Citizenship” of the Constitution of the Cherokee Nation states, “All citizens of the Cherokee Nation must be original enrollees or descendants of original enrollees listed on the Dawes Commission Rolls, including the Delaware Cherokees of Article II of the Delaware Agreement dated the 8th day of May, 1867, and the Shawnee Cherokees of Article III of the Shawnee Agreement dated the 9th day of June, 1869, and/or their descendants.”[32]

Chickasaw Nation. Under the Chickasaw Nation Constitution, Freedmen descendants are not eligible for enrollment in the Chickasaw Nation. In 1904, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Chickasaw Freedmen were not entitled to citizenship in the Chickasaw Nation under the relevant 1866 Treaty, because the Nation never adopted their Freedmen as provided for in the treaty.[33] Accordingly, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that the Chickasaw Freedmen (and their descendants) did not acquire the citizenship rights that were dependent upon adoption by the Chickasaw Nation.[34]

As of November 2025, “Article II – Citizenship” of the Constitution of the Chickasaw Nation states, “This Chickasaw Nation shall consist of all Chickasaw Indians by blood whose names appear on the final rolls of the Chickasaw Nation . . . and their lineal descendants.”[35]

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Under the Choctaw Nation Constitution, Freedmen descendants are not eligible for enrollment in the Choctaw Nation. No tribal or federal court has directly spoken to whether the Choctaw Freedmen descendants are entitled to citizenship in the Choctaw Nation according to the relevant 1866 Treaty.

As of November 2025, “Article II – Membership” of the Constitution of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma states, “The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma shall consist of all Choctaw Indians by blood whose names appear on the final rolls of the Choctaw Nation . . . and their lineal descendants.”[36]

Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Freedmen descendants’ ability to enroll in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation was an evolving matter as of November 2025.

In 2023, a Muscogee (Creek) Nation district court held that the relevant 1866 Treaty guarantees Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen descendants the same rights and privileges as the Tribe’s “by blood” citizens.[37] In July 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court upheld this decision, ruling that any reference to “by blood” citizenship in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Constitution and any of the Tribe’s rules, regulations, policies, or procedures was unlawful and that Freedmen descendants are eligible for tribal enrollment under the 1866 Treaty.[38] Accordingly, the Court directed the Muscogee (Creek) Citizenship Board to issue citizenship to any future applicants of Freedmen descent. In August 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation filed a petition for rehearing, arguing that the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court’s decision did not incorporate certain key facts and law, among other things. The Supreme Court denied the Tribe’s petition, finding that the Court had fully considered the issue, and that a rehearing was not warranted.

Following that decision, the Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation issued an executive order directing the Tribe’s citizenship office to continue accepting citizenship applications from Freedmen descendants, but not to issue them citizenship cards, or any other membership identification cards, until the Tribe’s law and policy had been fully reviewed and amended to meet the qualification requirements under the 1866 Treaty.[39] Thereafter, in October 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Freedmen descendants who filed the case above sought to have the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court enforce its ruling and order the Citizenship Board to issue them citizenship cards immediately. In response, in November 2025, the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court ordered the Citizenship Board to provide monthly status reports, with the first report covering, among other things, (1) actions taken by various tribal entities to update the Tribe’s code, rules, and internal policies and procedures, and (2) what the Citizenship Board asserts is a reasonable timeframe for completing all necessary steps prior to issuing Freedmen descendants citizenship documents pursuant to the Court’s July 2025 order. The Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court ordered that the first status report be filed by December 5, 2025.

As of November 2025, “Article III – Citizenship” of the Constitution of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation states, “Persons eligible for citizenship in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation shall consist of Muscogee (Creek) Indians by blood whose names appear on the final rolls . . . and persons who are lineal descendants of those Muscogee (Creek) Indians by blood whose names appear on the final rolls . . .”[40] However, as noted above, the Muscogee (Creek) Supreme Court has held that the restriction of citizenship to only descendants from the Dawes rolls “by blood” is unlawful and void.

Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. According to congressional testimony offered by the Seminole Nation in 2022, Freedmen descendants may enroll as “citizens” of the Seminole Nation, but not as what the Tribe refers to as “members,” which is a category only available to “by blood” Seminoles.[41] The Seminole Nation has developed two forms of tribal identification cards. According to the Tribe, a Seminole Nation Tribal Membership card can be obtained after an individual obtains a CDIB; a Tribal Citizenship card can be obtained by Seminole Freedmen descendants. The Tribe has stated in written testimony that “the Freedmen Tribal Citizenship Card provides the holder with the rights of citizenship of the Nation, primarily the right to vote.”[42] Under Seminole Nation law and policy, enrolled Seminole Freedmen descendants are not always regarded in an identical manner to Seminole Indian citizens with a degree of Indian blood.[43]

In 1940, a federal court found that the rights granted to the Seminole Freedmen in the relevant 1866 Treaty were equal rights to “by blood” Seminoles “in all tribal property as well as civil and other rights.”[44] Further, a federal court in 2001 determined that Interior had properly refused to approve amendments to the Seminole Nation’s Constitution that sought to remove their Freedmen descendants from the Tribe because the amendments would have violated the 1866 Treaty.[45]

As of November 2025, “Article II – Membership” of the Constitution of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma states, “The membership of this body shall consist of all Seminole citizens whose names appear on the final rolls of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma . . . and their descendants.” Further, “Article XII – Bill of Rights” of the Constitution states, “Each Seminole Indian citizen by blood of this body shall be entitled to membership in a Seminole Indian Band. Each Seminole Freedman citizen of this body shall be entitled to membership in a Freedman Band.”[46]

Enrolled Freedmen Descendants Have Faced Some Barriers Accessing Federal Services and Funds

Access to certain federal programs and services intended to benefit Tribes and their citizens extends to tribal citizens of the Five Tribes, including the more than 15,000 Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee Nation and the more than 2,000 Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma.[47] However, most of the 19 enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed told us of instances in which they and others faced barriers accessing federal services. These instances took place from 2017 through 2024 and were related to health care, education, or housing assistance generally available to tribal citizens that, according to agency officials, enrolled Freedmen descendants are eligible to receive.

|

Cherokee Nation 2024 Report on Access to Services by Enrolled Cherokee Freedmen Descendants The Cherokee Nation published a report that assessed enrolled Freedmen descendants’ access to Cherokee Nation programs, identified gaps, and proposed strategies to address any deficiencies. The report determined, among other things, that there is often a lack of awareness among enrolled Freedmen descendants about the programs and services available to them. In response to one of the report’s recommendations, the Cherokee Nation has taken steps to establish a resource team to help guide enrolled Freedmen descendants to more easily find information about these services, according to Cherokee Nation officials. Source: Cherokee Nation, 2024 Report on Access to Services by Cherokee Citizens of Freedmen Descent (June 19, 2024). | GAO‑26‑107118 |

According to several enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed, experiencing these barriers may discourage others from attempting to access such services. In addition, most of the enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma we interviewed told us of instances in which they faced barriers accessing some federal funds made available to other tribal citizens. According to Cherokee Nation officials and documentation they provided, the Cherokee Nation has been proactive in identifying and addressing potential access barriers for Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee Nation (see sidebar).

Difficulty Accessing Health Care Services

IHS, an agency within HHS, is responsible for providing health care for more than 2.8 million individuals who are citizens or descendants of federally recognized Tribes.[48] IHS provides health care services directly through its federally operated medical facilities and provides funding to Tribes to operate and manage their own medical facilities. Enrolled Freedmen descendants are eligible to access the same health care services provided and funded by IHS as other tribal citizens.

According to IHS officials we interviewed, there are many acceptable forms of documentation for proving eligibility to receive health care services, such as tribal identification cards, and none should be given a higher priority than other forms of documentation. According to these officials, IHS-funded facilities do not require tribal citizens to provide a CDIB card, issued by Interior’s BIA, to access their services or programs.[49] As previously noted, Freedmen descendants are ineligible to receive a CDIB card because they cannot document lineal descent from an ancestor with “Indian blood.” However, enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations are issued tribal identification cards.[50]

Several of the enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed told us that, since 2017, staff at IHS-funded facilities had denied them health care services because their tribal identification cards indicated that they were Freedmen descendants or because they could not provide CDIB cards to demonstrate eligibility. For example, in 2021, an enrolled Seminole Freedmen descendant was denied access to the COVID-19 vaccine at a federally operated IHS facility in the Oklahoma City area because of the individual’s status as an enrolled Freedmen descendant.[51] According to IHS officials, the incident initiated an internal agency review of the beneficiary status of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma’s enrolled Freedmen descendants, which resulted in a determination that enrolled Freedmen descendants are eligible for IHS health care services.

In October 2021, IHS issued a Dear Tribal Leader letter clarifying that enrolled Seminole Freedmen descendants are eligible to receive health care services in accordance with IHS eligibility requirements. Dear Tribal Leader letters inform Tribes about any rules, regulations, procedures, policies, and guidance that affect them directly or their duties and responsibilities to carry out programs or provide services administered by a federal agency. According to IHS officials, Dear Tribal Leader letters are primarily used to initiate the agency’s tribal consultation on specific topics. Moreover, in response to the incident, IHS officials told us that they also provided training to the staff at the facility in the Oklahoma City area regarding eligibility requirements for services provided.

According to IHS officials, Freedmen descendants who are enrolled as Cherokee citizens have been eligible for IHS services since 2017, when the Cherokee Nation began enrolling them. In response to the court ruling and the Cherokee Nation’s enrollment of Freedmen descendants, in November 2017, IHS sent a Dear Tribal Leader letter informing Tribes that enrolled Cherokee Freedmen descendants were eligible to receive health care services from IHS on the same basis as other tribal citizens of the Cherokee Nation.

IHS officials also told us that when the agency issued Dear Tribal Leader letters regarding the eligibility of enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations in 2017 and 2021 respectively, the Area Director of the Oklahoma City Area also issued copies of those letters to all IHS-funded facilities in the area. However, after these letters were issued, some of the enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed told us that administrative staff at certain healthcare facilities continued to request a CDIB to demonstrate eligibility, making it difficult for enrolled Freedmen descendants to access health care services.

Difficulty Accessing Education Services

BIE, a bureau within Interior, seeks to provide a high-quality education to approximately 46,000 students at 183 elementary and secondary schools on or near reservations in 23 states. About two-thirds of these schools are operated by Tribes through grants or contracts with BIE, while the remaining one-third are operated by BIE. BIE also contracts with Tribes, tribal organizations, school districts, and states to provide certain education programs to eligible students. In addition, BIE also operates a tribal college and a tribal university. For the purposes of certain BIE programs, under federal statute and regulations, an individual can be an “eligible Indian student” if they are a “member” of a federally recognized Tribe.[52]

Accordingly, Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations are eligible for education services that BIE funds and administers, provided they meet other relevant eligibility requirements. BIE does not require a CDIB card to access its services or programs, and an individual can satisfy certain eligibility criteria by showing enrollment in a federally recognized Tribe.

However, we learned of an incident, occurring in October 2020, in which an enrolled Freedmen descendant was denied admission to a BIE-operated university. According to some enrolled Freedmen descendants we interviewed and agency officials, administrative staff at the BIE-operated university denied the applicant admission because the applicant did not have a CDIB card. After the university’s administrative staff denied the applicant admission, the applicant relied on their tribal leadership to verify eligibility for admission and to coordinate with the university staff. After a delay of several months, the university stated that it would accept the applicant for admission the following semester if they reapplied, but the applicant ultimately chose not to reapply or attend this university. According to the applicant, this was partly because they felt discouraged by the university denying them admission based on their lack of a CDIB card. BIE officials were not aware of any additional incidents since 2017 in which an enrolled Freedmen descendant had encountered a barrier accessing BIE services.

In September 2024, BIE issued a Dear Tribal Leader letter clarifying the agency’s interpretation of “eligible Indian student” under the Indian School Equalization Program. The letter clarifies that program eligibility can be demonstrated by presenting a tribal identification card and that a CDIB card is not required.[53] BIE officials have also coordinated with leaders of BIE-operated schools, including the college and university, to help ensure that the schools’ staff understand the agency’s interpretation of the eligibility requirements. For example, BIE officials assisted college and university officials in developing new eligibility guidelines that were consistent with the agency’s 2024 Dear Tribal Leader letter.

Difficulty Accessing Housing Services

The Office of Native American Programs, an office within HUD, administers programs authorized by the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996, as amended (NAHASDA).[54] Such programs include block grants that Tribes use to develop new housing and to provide other types of housing assistance to eligible individuals. Subject to certain exceptions, such funding for eligible housing activities is generally “limited to low-income Indian families on Indian reservations and other Indian areas” as defined by the law.[55] NAHASDA defines an “Indian” as any person who is a “member” of a Tribe, which includes federally recognized Tribes.[56]

According to agency officials, eligibility is based on tribal enrollment in accordance with NAHASDA. Therefore, Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee and Seminole Nations are eligible for NAHASDA-authorized housing assistance that HUD’s Office of Native American Programs funds and the Tribes administer.

However, according to most of the enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma we interviewed, the Tribe’s housing policy prevents enrolled Freedmen descendants from receiving NAHASDA-authorized federally funded housing assistance because the Tribe’s policy gives preference to “by blood” Seminole citizens. Under NAHASDA, Tribes can establish a preferencing system for allocating housing assistance to eligible recipients.[57] As such, Tribes may give priority to applicants according to certain categories, provided the preference is consistently applied. For example, under the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma’s current preference systems for allocating NAHASDA funding to eligible recipients, “full-blood, enrolled Seminole Nation tribal member[s]” are awarded five points and “[a]ll other Seminole Nation tribal members,” excluding Freedmen descendants, are awarded one point for priority consideration. Enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma are not awarded any points for priority consideration under the Seminole Nation’s housing policies that we reviewed.[58]

According to officials from the Office of Native American Programs, the agency received a complaint about the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma’s housing policies in 2016 and reviewed the policies. According to agency documentation, at the time, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma required applicants for federally funded housing assistance to provide a CDIB card in addition to a tribal enrollment card. In 2016, HUD responded to the complaint and stated that the Tribe had since changed its application policy and no longer required applicants to provide a CDIB card for federally funded housing assistance. Agency officials told us that they have expressed concerns to Seminole Nation of Oklahoma officials that the execution of the Tribe’s housing policy, including its preferencing system, could raise further legal concerns based on possible Treaty obligations owed and potentially expose the Tribe to legal liability. Agency officials stated that they recommended that the Tribe change its policy.[59] However, as of July 2025, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma had not changed the preferencing system it uses to allocate NAHASDA funding to eligible recipients.

Agency officials told us that, since 2017, they have received no specific complaints regarding a denial of federally funded housing assistance provided by the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, including the Tribe’s use of its preferencing system. According to agency officials, HUD has a process to address any civil rights complaints and discrimination issues reported to the agency through an online portal and all complaints are investigated. They also told us that, as of October 2024, no enrolled Freedmen descendants were receiving federally funded housing assistance from the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. Several of the enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma we interviewed confirmed that Seminole Freedmen descendants do not apply for housing assistance through the Tribe because they consider it to be a futile effort and that, based on the Seminole Nation’s preference system, they expect there would be no funding available for them.

Difficulty Accessing Certain Tribal Programs That Have Received Federal Funds

According to most of the enrolled Freedmen descendants in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma we interviewed and federal agency officials, Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Seminole Nation are ineligible for certain tribal programs that have received federal funds. For example, Freedmen descendants cannot access the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma’s “Judgement Fund” programs. The Judgement Fund was awarded to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma in the 1970s as compensation for tribal lands in Florida ceded to the United States before the Tribe’s forced removal from those lands. Specifically, this compensation was awarded to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma as it existed in 1823, and the Tribe has used that fund to establish programs including for burial, clothing, and elderly assistance. However, tribal criteria for Judgement Fund programs generally restrict eligibility to enrolled members of the Tribe descended from a member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma as it existed in 1823. The Freedmen were not officially recognized as part of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma until 1866, and thus, are ineligible for the Tribe’s Judgement Fund programs.

While these programs have historically been funded by the compensation awarded to the Tribe in the 1970s, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma has also elected to distribute other federal funds—such as those provided to the Tribe under the American Rescue Plan Act—as a part of its Judgement Fund programs. Because the funds have been distributed in this manner, they are not accessible to enrolled Freedmen descendants. According to Interior officials, the American Rescue Plan Act provided Tribes with wide discretion in how they allocated the funding provided and Interior’s oversight of how the funding was allocated was limited.

Regarding these access issues, several of the enrolled Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed told us that agency guidance, such as Dear Tribal Leader Letters, may be helpful in addressing the barriers they encountered. Such guidance could clarify their eligibility for federal services, such as health care, education, and housing, among others, as well as identify appropriate documentation necessary to demonstrate eligibility for such federal services. For example, several Freedmen descendants of the Seminole Nation told us that, after IHS issued its Dear Tribal Leader letter regarding their eligibility for health care services and provided training to facility staff, they no longer encountered barriers accessing services at that particular federally operated facility in the Oklahoma City area.

Enrolled Freedmen Descendants Are Regarded Differently than Other Citizens of the Five Tribes Under Certain Federal Statutes

Our analysis and interviews with Freedmen descendants and agency officials showed that, under certain federal statutes concerning criminal jurisdiction and land ownership, enrolled Freedmen descendants are regarded differently than other citizens of the Five Tribes.

Criminal Jurisdiction

The exercise of criminal jurisdiction in “Indian country”—that is, which court has the legal authority to hear and decide a criminal case—depends on several factors.[60] In particular, under the Indian Country Crimes Act and Major Crimes Act, whether a crime committed in Indian country falls under federal, state, or tribal jurisdiction depends in part on the Indian status of the alleged offender and victim.[61] For example, the Major Crimes Act, as amended, provides federal courts with criminal jurisdiction over Indians charged with certain felony-level offenses enumerated in the statute, and generally state courts do not have jurisdiction over such crimes.[62]

However, neither the Indian Country Crimes Act nor the Major Crimes Act defines the term “Indian.” Therefore, federal and state courts have generally interpreted and applied the test for determining Indian status as set forth in United States v. Rogers, 45 U.S. 567 (1846). Under the Rogers test, for someone to be considered an “Indian,” there must be evidence that the person has some degree of Indian blood and that they are recognized as Indian by a Tribe or the federal government. Even though they are tribal citizens, enrolled Freedmen descendants may not meet the elements of this test because they do not have a lineal relationship to a person with a degree of “Indian blood” on official tribal rolls.

Because courts have defined Indian status for the purposes of criminal jurisdiction as requiring some degree of “Indian blood,” certain Freedmen descendants’ cases are heard in state court, while other tribal citizens’ cases are heard in federal or tribal court.[63] Several of the enrolled Freedmen descendants of both the Cherokee and Seminole Nations we interviewed raised concerns about the potential legal status of enrolled Freedmen descendants in the courts. For example, in a recent case, a Freedmen descendant who is enrolled in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma challenged the state’s authority to prosecute them on the basis of their Indian status.[64] However, the state appellate court ultimately determined that the individual met only one of the two requirements of the Rogers test—the individual proved affiliation with a Tribe through their tribal citizenship but was not able to demonstrate “Indian blood.” The individual attempted to use DNA evidence to demonstrate Indian ancestry; however, the court rejected the evidence based on its reliability, and the individual was ultimately found to be subject to state criminal jurisdiction.

Officials from the Department of Justice and Interior have met with tribal officials from the Cherokee Nation to discuss the Tribe’s concerns regarding criminal jurisdiction for Freedmen descendants who are Cherokee citizens, including revisions to the law proposed by leaders of the Cherokee Nation to include a statutory definition of “Indian” based on tribal enrollment. Officials from the Department of Justice told us that there are challenges in exercising jurisdiction over enrolled Freedmen descendants because case law has defined Indian status for the purposes of criminal jurisdiction as requiring some degree of “Indian blood.”

Land Ownership

Land in Indian country may include a complicated mixture of lands held by a Tribe, lands held by individual tribal citizens, and lands held by individuals and entities that are not affiliated with the Tribe. Such land held by the Tribe and individual tribal citizens may be held in trust, restricted, or fee status. Trust land is land that the United States holds the legal title to for the benefit of a Tribe or tribal citizen, which generally cannot be transferred (e.g., sold, gifted) or encumbered (e.g., mortgaged or leased) without the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. Restricted land is land that a Tribe or tribal citizen holds the legal title to and that is likewise subject to restrictions on transfers and encumbrances without the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. Trust and restricted lands are generally exempt from state and local property taxes. By comparison, fee land generally does not have restrictions on transfer or encumbrance and, when located outside Indian country, is subject to property taxes.

The Act of August 4, 1947 (commonly referred to as the Stigler Act), as amended, governs the restricted status of allotted lands held by citizens of the Five Tribes. Under the act, when such land is inherited or otherwise acquired, it retains its restricted status only if it is held by citizens of the Five Tribes with lineal descent from the “by blood” rolls.[65] Because the Freedmen were documented as having no degree of Indian blood, Freedmen descendants who are tribal citizens are unable to inherit or otherwise acquire restricted land without the land losing its status.[66] Interior officials we interviewed said that while they are aware of the differential treatment of enrolled Freedmen descendants under the law, their ability to resolve that differential treatment is limited because of the statutory language requiring lineal descent from the “by blood” rolls.

Agency Comments and Third-Party Views

We provided a draft of this report to HHS, HUD, Interior, the Department of Justice, and the National Archives and Records Administration for review and comment. HHS, HUD, and the Department of Justice provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. Interior and the National Archives and Records Administration did not have any comments on the report. We also provided selected draft excerpts to the Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma; the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation; officials we interviewed from an association representing Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes; and other stakeholders for review and comment. The Cherokee Nation did not have any comments. The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and Chickasaw Nation did not provide comments. The association representing Freedmen descendants of the Five Tribes and other stakeholders did not have any comments.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of HHS, the Secretary of HUD, the Secretary of the Interior, the U.S. Attorney General, the Acting Archivist of the United States, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at OrtizA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Anna Maria Ortiz

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Appendix I: Demographic Simulation Models for Estimating the Five Tribes’ Freedmen Descendant Population

We developed cohort-component demographic models to estimate the population size, as of 2022, of Freedmen descendants of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations of Oklahoma, collectively known as the Five Tribes.[67] The models estimate how the Freedmen population size may have changed over time, as people died, reproduced, and migrated for the 1907 through 2022 estimation period. Two independent internal reviewers with expertise in demography and vital statistics concurred that our analysis and estimates were reliable for estimating the Freedmen descendants’ population size. Below, we describe our models’ assumptions, implementation methods, validation process, and limitations.

Starting Population

The starting population for our models is the lists of the Freedmen on the Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory, referred to as the Dawes Rolls, which were compiled from 1898 through 1907.[68] For our analysis, Freedmen refers to people listed as Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls and Freedmen descendants refers to people who can trace their lineal descent back to a person or people listed as Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls. The Dawes Rolls are considered the base rolls for each of the Five Tribes for the U.S. government and the Tribes, and only those who can trace their lineage back to a person or people listed on the Dawes Rolls may be eligible for citizenship in one of the Five Tribes.

We determined the Dawes Rolls to be the only population lists for Freedmen and the best data source for the Freedmen population. There are no other lists of Freedmen or Freedmen descendants that could be used for demographic modeling. We made this determination by conducting a literature review in March 2024 to identify any lists of the Freedmen population. We also reviewed publicly available documents, including from the Five Tribes and the Oklahoma Historical Society, and met with officials from BIA and the National Archives and Records Administration.

The National Archives and Records Administration maintains the records for the Dawes Rolls, including those records that have data needed to estimate the Freedmen descendants’ population, the Dawes Rolls and enrollment cards.[69] These documents provide each Freedmen’s name, enrollment number, age, and sex. The Dawes Rolls list Freedmen for each of the Five Tribes.

Electronic databases for the Dawes Rolls were necessary to tabulate the starting populations of Freedmen descendants by age and sex. We obtained electronic copies of the Dawes Rolls from the Oklahoma Historical Society and a commercial vendor. Both databases included lists of people approved for enrollment on the Dawes Rolls of the Five Tribes. We relied primarily on the commercial vendor database because the vendor used a more thorough process for inputting the data from both the original enrollment cards and Dawes Rolls.

We determined that the electronic databases were reliable for our purposes by reviewing documentation about the databases and meeting with officials from the National Archives and Records Administration, the Oklahoma Historical Society, and the commercial vendor about the process and quality controls used to digitize and maintain the databases. We conducted electronic reliability tests on both databases to assess completeness of the records by comparing population counts by age, enrollment group, and sex between each source and with population totals reported for the Dawes Rolls from secondary source documents.

Modeling Inputs: Fertility and Mortality Rates Based on Geographic Location and Migration

The demographic models required input data on fertility and mortality rates based on geographic location and migration rates across 115 years. We made assumptions about Freedmen and their descendants, including which of the available data for geographic location, migration, and racial groupings best represented the Freedmen population.[70] We met with experts who have historical and current knowledge on the population of Freedmen and their descendants, and the experts agreed that our data assumptions on locations and fertility and mortality rates were the best available for the modeling.

Geographic Location Assumptions for Fertility and Mortality Rates

Our cohort-component demographic models required input data on migration, fertility, and mortality rates, which vary by geographic location. We could not obtain reliable and precise data on exactly where Freedmen descendants moved over more than 115 years, which would have required an extensive genealogical analysis of households. As a result, we developed assumptions about the possible domestic migration patterns and residential locations of Freedmen descendants from 1907 through 2022 to identify applicable fertility and mortality rates.

Geographic location could have affected the fertility and mortality of Freedmen descendants over time, because infectious disease rates and mortality have varied geographically within the United States from 1907 to the present, even accounting for other factors, such as age and race. For example, local conditions may have varied with respect to public health interventions, socioeconomics, and climate, producing variation in fertility and mortality rates. Therefore, we made assumptions about where Freedmen descendants lived from 1907 on.

For international migration, we assumed there was no emigration or immigration of the Freedmen and their descendants during the period of analysis. International migration is unlikely to have affected the population of Freedmen descendants, because Freedmen descendants that may have moved abroad would retain their lineage to ancestors on the Dawes Rolls, so our estimates include any descendants living abroad. Further, migration into the population of interest is not possible because Freedmen descendants must trace lineal descent from a person or people on the Freedmen lists of the Dawes Rolls.

Fertility and mortality rates vary by geographic location, and, therefore, we developed assumptions about the possible domestic migration patterns and residential locations of Freedmen descendants from 1907 through 2022 to apply rates to the modeling. We based these location assumptions on two sources. First, as of 2024, the Cherokee Nation reported that 60 percent of their Freedmen citizens lived in Oklahoma and substantial populations of Freedmen descendants lived in California, Kansas, and Texas.[71] Second, an expert on the Freedmen descendant population we interviewed agreed that descendants may have disproportionately remained in Oklahoma or moved to California, Kansas, and Texas.

Racial and Ethnic Assumptions for Fertility and Mortality Rates

To meet the input requirements of cohort-component models, we identified the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sources from 1907 through 2022 measuring fertility and mortality rates separately by year, age, race, ethnicity, and sex for the United States and California, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. In particular, the models require “age-specific fertility rates,” which measure the ratio of births by women in specific age groups to the total number of women in those age groups.

The format and detail of the sources varied over time and by geographic location, which presented options for data collection and model specification. Earlier data were available only in printed publications, while later data were available in electronic data files. Racial classifications changed and expanded throughout the period. We scoped our analysis and choice of data sources to balance staff time against the breadth and precision of the input data available. Below, we describe our choice of data sources and methods for processing them.

National Fertility Rates

We obtained national fertility rate data for 1907 through 2002 from printed statistical tables published by the CDC and its predecessors, primarily yearly or multiyear editions of Vital Statistics of the United States.[72] We used age-specific fertility rates, which avoided the need to apply separate adjustments for varying mortality across age groups.

1907 through 1932. We obtained national fertility rates for 1907 through 1932 from Vital Statistics Rates in the United States, 1900-1940, and a similar publication covering 1940 through 1960 that included data in this date range, from federal health statistical agencies.[73] We collected rates separately by year, the mother’s age, and two racial groups: “White” and “All Other.” We used rates for people in the “All Other” group in lieu of more specific groups that may have been more likely to contain Freedmen descendants. Published rates in this period reflected data submitted by various states, as part of the national birth registration system. Some states joined the system earlier than others, and the system included all states in our review for the first time in 1933.

Through 1932, fertility data were available only for the “registration area,” which included participating states. Fertility rates were not available in these sources by race until 1918, so we used data for the registration area in 1918 to impute values during this period.

1933 through 1967. We obtained national fertility rates for 1933 through 1967 from Vital Statistics Rates in the United States, 1900-1940, and a similar publication covering 1940 through 1960, separately by year, the mother’s age, and two racial groups: “White” and “All Other.” The latter group continued to serve as the closest approximation for Freedmen descendants. State participation in the vital statistics system varied through 1933, when all states existing at the time were participating, and CDC corrected rate estimates for the under-reporting of births within each state through 1959.

1968 through 2002. We obtained national fertility rates for 1968 through 2002 from a historical table in the CDC publication, Vital Statistics of the United States, 2003, separately by year, the mother’s age, and “American Indian” and “Black” racial groups.[74]

2003 through 2022. We obtained national fertility rates from CDC’s Wide-ranging ONline Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) website, separately by year, the mother’s age, and “Non-Hispanic Black/African American” and “Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native” racial groups.[75]

State Fertility Rates

Fertility rates for each state were less available, accessible, and detailed by age and race from 1907 through 2022 than for the United States overall. In particular, the CDC did not start publishing fertility data for Oklahoma until 1930 and Texas until 1940. As a result, we could not use state fertility rates before 1930, so we substituted national rates.

1930 through 1967. We obtained state fertility rates by the mother’s age and race for decennial census years from 1930 through 1960, via time-series tables published in the summary publications mentioned above. Available racial groups most relevant to Freedmen descendants included “Other (non-White).” We interpolated rates for 1962 using the published 1960 estimates from CDC’s Vital Statistics of the United States and estimates for 1968 that we made using public-use microdata.

1968 through 2002. Aggregate electronic data on births and fertility rates are not available from the CDC until 1995. However, CDC public-use microdata files exist for 1968 through 2002, which contain records for each birth along with various characteristics of the mother, child, and birth setting.[76] For each year, we used the microdata to tabulate births by state and the mother’s age and race. The available racial groups most relevant to Freedmen descendants were “Negro” and “Other (non-Negro, non-White)” from 1968 through 1979, and “Black” and “American Indian” from 1980 through 2002. We calculated fertility rates by merging female population data for each year and age-race group from the Population Estimates Program at the U.S. Census Bureau (1968 through 1992) and CDC WONDER (1997 through 2002).[77]

2003 through 2022. We obtained fertility rates from CDC’s WONDER website for each year and by mother’s age and race from 2003 through 2022.[78] The available racial/ethnic groups most relevant to the Freedmen were “Non-Hispanic Black/African American” and “Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native.”

National Mortality Rates

Similar to fertility rates, the format and detail of available mortality rates varied over time and by geography. Earlier data were available only in printed publications, while later data were available in electronic data files.

1907 through 1967. We obtained national mortality rates by age, race, and sex from 1900 through 1998 from a series of CDC published tables, known as the “HIST290” tables.[79] The data were grouped by age into approximately 10-year intervals, and grouped by race into “Black,” “White,” and “All-Other,” with “Black” being the group most relevant for Freedmen descendants. “HIST290” provided a series of data that were consistently collected and formatted over a long time period, which limited the need to collect extensive data. Mortality rate data prior to 1933 were available only for those states that participated in the national death registration system. Before 1933, we used the available rates for the “registration area” of participating states.

1968 through 2022. We obtained mortality rates for 1968 through 2022 from the CDC’s WONDER website.[80] Various racial groups relevant to Freedmen descendants were available throughout the period, including periods when data were available on multiple group identifications and both race and Hispanic ethnicity. We selected data for the groups that were most relevant to the Freedmen descendant population and that allowed for reasonable consistency with prior time periods. These included “American Indian” and “Black/African American” of any ethnicity, using “bridged race” groups from 1999 through 2020 and “single race” groups from 2021 through 2022. We developed scenarios of plausible racial and ethnic classifications over time and used mortality rates from different groups in specific years as model inputs, in order to develop interval estimates and account for uncertainly.

State Mortality Rates

State mortality rates prior to 1968 had similar limitations of access and granularity as state fertility rates. During this period, CDC published state mortality counts and rates in yearly and multiyear editions of CDC’s Vital Statistics of the United States, which we converted into electronic format through manual data entry and automatic processing of images. We obtained post-1968 state mortality rates in electronic formats from CDC’s WONDER website.