HEALTH CARE ACCESSIBILITY

Further Efforts Needed to Address Barriers for People with Disabilities

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Elizabeth H. Curda at curdae@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

People with disabilities may encounter barriers related to accessibility in the U.S. health care system; these barriers can affect the quality of their care. GAO analyzed research literature on health care accessibility and conducted interviews with stakeholders and identified the following potential barriers.

Types of Potential Barriers to Accessibility in Health Care Described by Literature and Selected Stakeholders

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) does not collect national-level data on the accessibility of health care from people with disabilities. GAO analyzed 12 HHS population health surveys. One survey included a question on bias, but none covered other barriers to accessibility. HHS has established goals to increase the accessibility of health care through data collection, but officials stated that they do not have plans to collect related national-level data. Such plans would better position HHS to accurately identify barriers and evaluate the effects of HHS regulations that cover nondiscrimination in health care.

Within HHS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and Office of Civil Rights (OCR) oversee aspects of health care organizations’ compliance with federal laws, but oversight related to accessibility has been limited. Specifically, CMS (1) uses an on-site inspection process to ensure that organizations participating in Medicare comply with health and safety standards and (2) inspects some aspects of accessibility. OCR investigates some accessibility issues through compliance reviews and from complaints. But it does not routinely share information on the results of its compliance reviews or complaint investigations. Sharing these results could broaden the impact of OCR’s efforts to other health care organizations. In 2024, HHS amended its regulations, adding accessibility requirements, and HHS’s current strategic plans state that accessibility is a priority. However, these plans do not include details or time frames for achieving this priority. As a result, HHS may not take appropriate steps to ensure that health care organizations meet accessibility requirements and some people with disabilities may continue to face barriers to obtaining health care.

Why GAO Did This Study

Millions of adults in the U.S. report having some form of a disability, such as a condition that affects vision, movement, hearing, or mental health. Federally funded programs such as Medicare pay for health services, including for people with disabilities. Although federal laws prohibit these programs from discrimination on the basis of disability, people with disabilities may face barriers to obtaining health care.

GAO was asked to review federal efforts, including data collection and oversight, to ensure the accessibility of health care for people with disabilities. This report examines (1) barriers to accessible health care that people with disabilities may face, (2) HHS data collection efforts on the accessibility of health care, and (3) related HHS oversight.

GAO reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and HHS policies and guidance; examined peer-reviewed literature on barriers to accessible health care published between 2013 and 2024; analyzed HHS accessibility-related data collection efforts; and conducted a nongeneralizable survey of 1,194 adults with disabilities. GAO also interviewed HHS officials and representatives from nine disability associations and research groups and two accrediting organizations.

What GAO Recommends

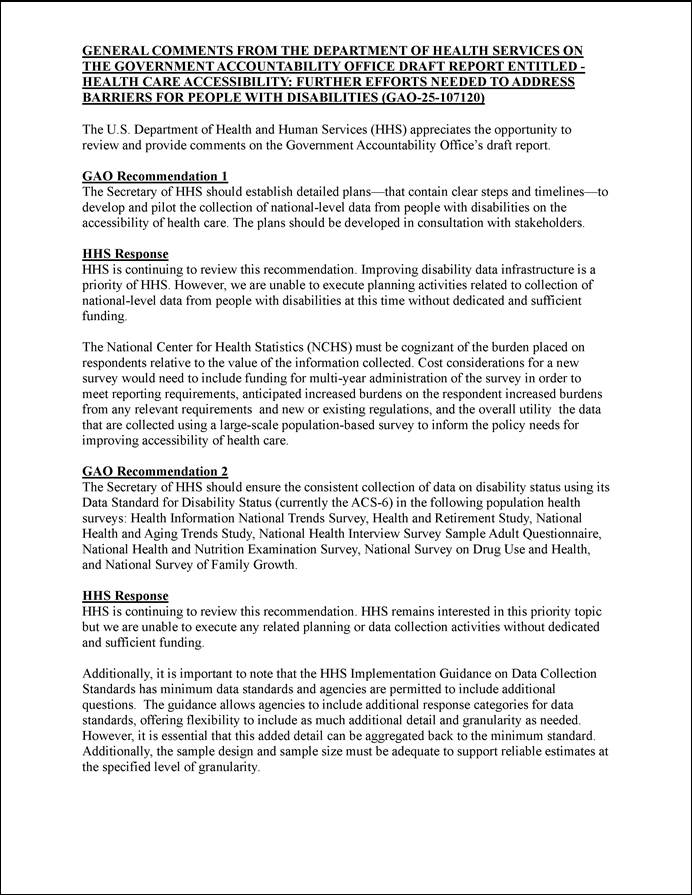

GAO is making five recommendations, including that HHS develop plans to collect national-level data from people with disabilities on health care accessibility, share data on results of OCR’s current oversight efforts, and establish detailed plans to help ensure health care accessibility. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendations, as discussed in the report.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ACS-6 |

American Community Survey six questions on disability |

|

ADA |

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 |

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NCI |

National Cancer Institute |

|

NIA |

National Institute on Aging |

|

OCR |

Office for Civil Rights |

|

SAMHSA |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 19, 2025

Congressional Requesters

One in four adults in the United States reports having a disability.[1] There are many types of disabilities, such as those that affect a person’s vision, movement, hearing or mental health. People can be born with disabilities or acquire disabilities at any point in their lives. People with disabilities may have complex health care needs and require multiple health care services including specialty care, medical equipment, prescriptions, and in-home services.

Federally funded programs, such as Medicare, pay for health care services for many people with disabilities. Although federal laws prohibit these programs from discriminating on the basis of disability, people with disabilities may face barriers to obtaining health care, such as inaccessible exam rooms and equipment. Health disparities for people with disabilities compared with people without disabilities have persisted over decades.[2]

You asked us to review federal efforts to ensure equitable treatment of people with disabilities in health care settings, including data collection and oversight. This report examines: (1) barriers to accessible health care that people with disabilities may face and steps taken by selected providers to address such barriers, (2) the extent of the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) data collection efforts on the accessibility of health care and on disability status, and (3) the extent of HHS oversight of the accessibility of health care for people with disabilities.

To answer all objectives, we reviewed relevant federal laws and regulations as well as agency policies and documents. We also interviewed agency officials at HHS, the Department of Justice, and the U.S. Access Board.[3]

To address our first objective, we reviewed and analyzed existing research on health care accessibility for people with disabilities. To identify studies, we searched various health care and social science databases for reviews of studies published in peer-reviewed journals between calendar years 2013 and 2024, using keywords related to types of disabilities, health care settings, accommodations, barriers, and health insurance. We identified 22 reviews of studies, which covered a wide range of disabilities, including physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental, and mental disabilities, and used them to help us establish the categories of barriers that people with disabilities might face.

We also interviewed nine stakeholder organizations, including disability associations and policy research groups. We selected these organizations to cover a range of disability populations and knowledge about health care and accessibility. We gathered their perspectives on barriers to accessible health care, how these barriers may be experienced by different disability populations, and any recent or emerging barriers not captured in the literature. To describe steps taken by providers to address these barriers, we first identified health care organizations that have taken steps to address specific barriers by asking stakeholders for recommendations. We then selected among the recommended organizations by focusing on those that could speak to a range of health care accessibility-related initiatives targeted to people with disabilities.

To obtain perspectives from people with disabilities about their experiences receiving health care, we conducted a survey of adults with disabilities who obtain their health care in the United States. This nongeneralizable web-based survey included open-ended questions about barriers faced in receiving health care. We distributed the survey to the stakeholders and researchers we interviewed and asked them to disseminate it among their networks. We received a total of 1,426 responses: 1,194 from adults with disabilities and 232 from caregivers on behalf of a person with a disability. We reviewed responses to our survey and identified excerpts of these responses to illustrate the barriers described in the report.

To address our second objective, we reviewed HHS documents and websites and interviewed officials about HHS’s collection of national-level data on the accessibility of health care for people with disabilities and disability status. We limited the scope of our analysis to population health surveys conducted or sponsored by HHS. Based on this review and these interviews, we identified and analyzed 12 population health surveys and a Medicaid information system. We compiled the results and confirmed our findings with HHS officials.[4] We assessed HHS’s data collection efforts against HHS guidance and plans and federal standards for internal controls for the use of quality information. We also interviewed five researchers in the areas of the accessibility of health care and disability measurement about current HHS data collection efforts on the accessibility of health care and disability status, gaps in these efforts, and best practices for the collection of disability data. Other stakeholders we interviewed recommended these researchers to us.

To address our third objective, we reviewed HHS’s processes for monitoring and overseeing health care organizations regarding accessibility. We focused our review on HHS’s oversight of health care organizations participating in Medicare. We focused on Medicare because the Medicare program is administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), while Medicaid is jointly administered by CMS and the states. Moreover, many institutions receiving Medicare funding also receive Medicaid funding. We also reviewed agency requirements for health care organizations, including Medicare health and safety standards.[5] We focused on health and safety standards for organizations that provide sustained patient care, including hospitals, hospice, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies. We also interviewed officials from CMS and the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) about efforts to oversee Medicare-participating health care organizations on accessibility.[6] We assessed HHS’s efforts to monitor accessibility against HHS policies and federal internal control standards for designing and implementing control activities. We also interviewed selected stakeholder organizations discussed earlier, and two accrediting organizations, about HHS’s monitoring efforts and areas for improvement. We selected the two accrediting organizations because they focus on multiple facility types that were included in our review.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Requirements Related to the Accessibility of Health Care for People with Disabilities

Health care facilities are generally subject to federal laws and regulations prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability. Specifically:

· Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA): prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities by public entities and by places of public accommodation, regardless of whether they receive federal funds.

· Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504): prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. Thus, organizations (including health care facilities) who receive federal financial assistance, such as through Medicare reimbursement, are subject to Section 504.

· Section 1557 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Section 1557): prohibits health programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance from discriminating against people on various grounds, including disability. According to HHS, examples of health programs or activities subject to this prohibition include hospitals that accept Medicare, doctors that receive Medicaid payments, insurance companies that participate in Health Insurance Marketplaces, and health programs administered by HHS.

In 2024, HHS issued final rules to amend both Section 504 and Section 1557 regulations, which address requirements for entities receiving federal funds. Among other things, the updates to the Section 504 regulations:

· Explicitly prohibit discrimination against individuals with disabilities in medical treatment, web content and mobile applications, and medical diagnostic equipment.

· Generally permit the use of service animals and mobility devices.

· Generally require the maintenance of features of facilities and equipment to be accessible.

|

Reasonable Modifications Recipients of federal funding from HHS must generally make reasonable modifications in policies, practices, or procedures to avoid discriminating on the basis of disability. Examples of possible modifications include: · Allowing a service animal to be present at a medical appointment. · Providing discharge or medication instructions in large print. · Making an exam room accessible. People with disabilities can potentially face barriers when certain modifications are not provided. Source: Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). | GAO‑26‑107120 |

Among other things, the updates to the Section 1557 regulations require entities to inform patients that accessibility services are available at no cost.

The Department of Justice also updated its regulations for Title II of the ADA, which included specific requirements about accessibility through web content and mobile applications.

Role of Federal Agencies

Several federal agencies have responsibilities related to ensuring accessibility in health care for people with disabilities:

· Department of Health and Human Services. Several agencies and offices at HHS have taken steps to help ensure accessibility for people with disabilities. For example, HHS’s OCR enforces Section 504, Title II of the ADA, and Section 1557. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and CMS have collected disability data, including information about health care needs and access.[7] CMS sets health and safety standards for facilities that receive their funding and oversees a monitoring process to ensure compliance with these standards.

· Department of Justice. The Department of Justice’s Disability Rights Section enforces federal civil rights laws through investigations; compliance reviews; and, if necessary, lawsuits and settlement agreements. The Department of Justice is also responsible for developing regulations that implement Titles II and III of the ADA. The Department of Justice also coordinates executive agencies’ implementation of Section 504 and the ADA, among other activities.

· U.S. Access Board. The U.S. Access Board is an independent federal agency that develops and maintains accessibility guidelines for information and communication technology and medical diagnostic equipment, among other areas. It also provides related technical assistance and training.

People with Disabilities May Face Various Barriers to Receiving Health Care, and Selected Providers Have Taken Steps to Enhance Accessibility

People with disabilities may encounter various barriers to receiving health care, according to peer-reviewed literature we reviewed and stakeholders we interviewed. These barriers can include features of medical facilities and equipment, technology, communication with providers, and insufficient provider training on health care for people with disabilities (see fig. 1).[8]

Figure 1: Types of Potential Barriers to Accessibility in Health Care Described by Literature and Selected Stakeholder Organizations

Features of Medical Facilities and Equipment

Medical Facilities

Literature and interviews with selected stakeholder groups identified features of medical facilities as a potential barrier for some individuals with disabilities. In particular, people with physical disabilities or sensory differences can find navigating medical facilities challenging.

|

Quote “I had an appointment that I was unable to keep because the elevator to the provider’s office was not functioning; it wasn’t fixed for several months.” —A person who has cerebral palsy Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Physical disabilities. One review of studies on cancer screening for women with physical disabilities found that elements such as narrow hallways, stairs, poorly designed restrooms, and inadequate signage made people with disabilities feel unwelcome and discouraged them from returning for care.[9] In other studies, women with disabilities receiving maternity care reported that offices, restrooms, and washrooms were inaccessible to wheelchairs and impeded their ability to receive care.[10]

|

Quote “I have severe reactions to fragrances and chemicals. Many doctors and dental offices have used cleaners and other heavily scented products throughout their spaces. This includes soap. As someone who is high-risk for infections due to being immunosuppressed, it's bad news when I cannot wash my hands in a healthcare facility, let alone when I have to take allergy medications to simply not go into anaphylaxis in these offices.” —A person with developmental, physical, and psychiatric disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Sensory differences. Some individuals with disabilities may have difficulties processing sensory information in medical facilities. For example, some individuals with autism may become overwhelmed by bright lighting, strong smells (e.g., cleaning products), or noise.

Several reviews of studies noted that the physical environment of a waiting room, including the uncertainty of long wait times and crowds, may also heighten feelings of anxiety or create undue stress.[11] One review regarding autistic adults’ access to mental health care found that many of the sensory aversions they cited could be accommodated. However, autistic adults reported that providers often did not offer accommodations.[12]

|

Quote “There are no options for a private waiting area. [The person I care for] gets overstimulated by a noisy waiting room due to his autism.” —A caregiver for an autistic person with several disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

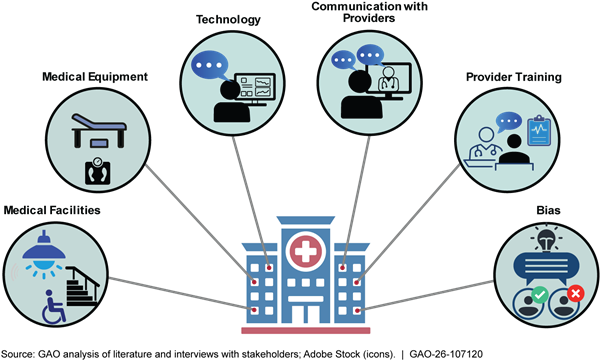

Selected providers have adopted some promising practices to address accessibility barriers regarding medical facilities. (See fig. 2.)

Medical Equipment

Literature and selected stakeholders we interviewed identified inaccessible medical equipment as a potential barrier for some people with disabilities. For example, they found that some mammography equipment, exam tables, and scales may not accommodate people with physical disabilities.

Mammography equipment. One review of studies on cancer screenings found that mammography units that require people to stand during the process could be problematic for people with physical limitations.[13]

|

Quote “I had to leave without care because I couldn’t get on an exam table. My care for a wound was delayed for a month.” —A person who has spina bifida with several disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Exam tables. Colorectal and gynecological screenings often require people to be able to climb onto and position themselves on an exam table, which can be difficult for some people with physical disabilities.[14] For example, the exam table may be too high or narrow, it may lack handles, or its surface may be slippery.

|

Quote “As a rural [resident] with disabilities, many of my doctor's offices are in old houses with…old wooden exam tables. I can only get weighed at the veterinarian.” Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Scales. People with physical disabilities may also be unable to access scales. One respondent in a study of maternity care for women with disabilities told researchers that, throughout her pregnancy, her doctors had never been able to monitor her weight because the office did not have a wheelchair-accessible scale.[15]

See figure 3 for examples of medical equipment designed to accommodate people with disabilities.

|

Quote “When getting a CPAP [a machine used to treat sleep apnea], no one understood my needs as a blind person, specifically the need to be able to independently operate the equipment…The digital display is not accessible. I had to call [my provider] to get help to change the humidity setting, and they said, ‘you can see it on the display.’ Once again, I had to say I am blind, and they made the change remotely. So, I have to wait for their office hours to make changes to equipment that I use through the night.” —A person who is blind Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

According to stakeholders we interviewed, if people with disabilities cannot be properly examined because of inaccessible medical equipment, their care may suffer. For example, one stakeholder described a person with cerebral palsy who uses a feeding tube and had not been weighed for about 10 years; as a result, their providers had no accurate weight to calculate their caloric needs.

Even when offices have medical equipment designed for people with disabilities, it may not be consistently available when needed, or providers may lack training on correct usage. According to stakeholders we interviewed, the equipment may be missing pieces, stored away, or disassembled when not in use. One stakeholder stated that physicians have said that accessible exam tables take too long to operate.

Technology

Technologies—including telehealth services, electronic health records and other digital systems, and check-in kiosks—play an increasing role in health care, but some people with disabilities may struggle with using and accessing them.

|

Quote “I have done two telehealth calls. Neither had captions or even a chat box. No telehealth system should be without a chat box…Moreover, the lighting and video quality was poor, making it hard to watch [the provider’s] face.” —A person who is deaf Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Telehealth services. Some people who are deaf or blind may face barriers using telehealth services. For example, one stakeholder we interviewed stated that a telehealth platform may permit only one person to join the appointment with the provider, meaning that a sign language interpreter or support person in another location cannot participate.

Electronic health records. According to stakeholders we interviewed, electronic health record systems may not have cognitive accessibility standards, such as standardized layouts or easily understandable language. This can make them difficult to navigate for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities. In addition, although electronic health records may contain data on a person’s disability or their necessary accommodations, that information can be difficult to find when it is stored in different sections of the electronic health record.

|

Quote “My pharmacy will no longer accept phone calls to set up medication delivery; that must be done online. The form I need to complete to do that is not completely accessible using my screen reader. This means that I must constantly ask friends and relatives to pick up my medications. This means that I am less independent than I was several months ago.” —A person with developmental and sensory disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Check-in kiosks. Stakeholders we interviewed said that check-in kiosks may not be usable by people with visual disabilities. Check-in instructions may also be difficult to navigate and lack plain language, which can pose a problem for some people with cognitive disabilities.[16]

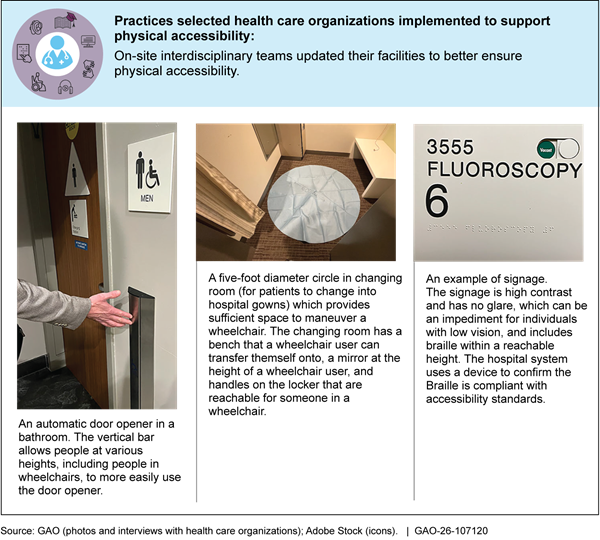

Selected providers have adopted some promising practices to address accessibility barriers regarding technology (see fig. 4).

Communication with Providers

Based on our review of research literature and interviews with selected stakeholders, people with a variety of disabilities may struggle to receive the information they need from medical staff. For example, communication could be challenging for people with some disabilities.

|

Quote “There is a lack of available sign language interpreting services. All my appointments require waiting a significant amount of time to get an interpreter. Frequently they will ask to change the appointment as they can’t get one.” —A person who is deaf Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Deaf or hard of hearing. A review of studies that focused on health care access for people who are deaf or hard of hearing found that 92 percent of those studies mentioned communication as a barrier, including a lack of sign language interpreters and the need to spend more time with patients to ensure understanding.[17]

|

Quote “Information collection either prior to or at time of appointment is always small print text or computer screen. My requests for either large print or assistance are often met with consternation, dismissal, or insistence that I 'try my best.' I refuse and demand accommodations but am quite aware that this negatively impacts services received.” —A person who has low vision Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Blind or low vision. One stakeholder stated that providers may not use verbal cues with people who are blind or have low vision, such as informing the patient that they are in the room. Also, the stakeholder said that providers may expect them to bring a companion to complete paperwork.

|

Quote “I also struggle with my communication. Doctors talk too quickly, and I don't always understand. I also have problems expressing myself. And when I do bring up concerns, I am aware that I'm often being misunderstood or not taken seriously.” —An autistic person with several disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Intellectual or developmental disabilities. In multiple reviews of studies, people with intellectual or developmental disabilities reported finding it difficult to understand both verbal and written health information. For example, when providers used medical terminology instead of plain language or did not provide supplemental information such as diagrams or clear follow-up instructions, people with intellectual or developmental disabilities said that this meant they were poorly prepared for later appointments or procedures.[18]

One review also found that people with intellectual or developmental disabilities often felt they did not understand their providers, and felt less capable when interacting with providers than they did in everyday life.[19] The review also found that they felt that health care providers did not always take communicating with them seriously. Literature and stakeholders also found that people with intellectual or developmental disabilities may require accommodations to effectively communicate with their providers, such as longer or more frequent appointment times and the use of plain language.

For all these disabilities, communication difficulties can be further complicated by the large amount of information a provider may give a person and the limited amount of time providers spend with individuals, according to a stakeholder and a review of studies.

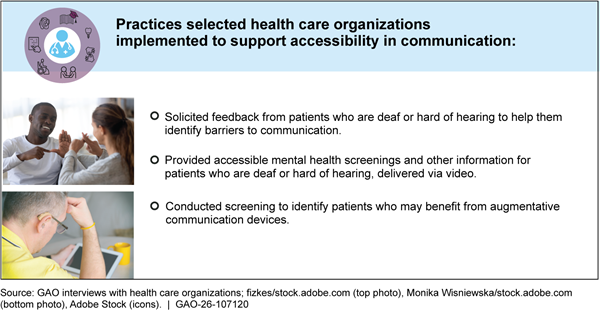

Selected providers have adopted some promising practices to address accessibility barriers regarding communication. (See fig. 5.)

Provider Training and Bias

Provider Training

Literature and interviews with stakeholders identified lack of training for medical staff as a potential barrier that impedes individuals’ receipt of care. In a 2024 report, we found that disability training for health care providers is not widely required or standardized by the organizations that accredit provider training programs.[20] We reported in 2024 that stakeholders noted that limited training can affect the care people with disabilities receive, including contributing to delays in receiving care or the need to travel long distances.

|

Quote “Often, only a few staff know how to use the lift and sling for transferring me from my motorized wheelchair to an MRI table, CT scan, or x-ray table which limits the days and times of appointments for tests. Staff do not receive monthly in-service training on patient lifts so without practice, they forget how to use the lift and sling when it is actually needed.” —A wheelchair user with several disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Literature and stakeholders we interviewed provided examples of how limited disability training for medical staff can affect care.

Equipment expertise. According to one review of studies, staff who lack training on the use of accessible medical equipment may not use it when examining individuals with disabilities or may attempt to use it with limited skill.[21] For example, lifts can be used to transfer individuals with mobility disabilities onto an exam table, and one interviewee with a disability described the experience of being transferred by untrained staff as “frightening.”

|

Quote “Even living in a city with access to very skilled doctors at research and teaching institutions, there are very few health care providers who have a functional working knowledge of my condition—and its specific features and risks. Getting high-quality health care requires significant personal research so that I can competently share the currently developing clinical protocols to my providers.” —A person with a physical disability Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Provider knowledge. One study discussed in a review of studies found that over one-third of respondents felt as though they had to educate their doctors about their disabilities; nearly a quarter had some feeling of dissatisfaction when they left appointments.[22]

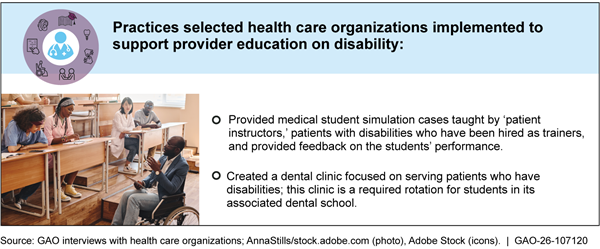

Selected providers have adopted some promising practices to address accessibility barriers regarding provider training. (See fig. 6.)

Bias

|

Quote “I have had dentists refuse to take me to have my wisdom teeth removed. I was told they don’t take people like me.” —A person with autism Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

According to literature and interviews with stakeholders, providers’ lack of understanding and lack of training about disabilities can cause providers

to rely on perceived stereotypes and misconceptions in their care of people with disabilities, which can be a further barrier to health care access. For example, bias may affect the services offered to people with disabilities or their interactions with providers.

|

Quote “I had gynecologists recommending a hysterectomy from about the time I was 16 years of age on because it was presumed I wouldn't have children. When I had difficulty getting pregnant, I was not offered the same fertility testing and treatments as my non-disabled peers. This resulted in me not having children.” —A person with a physical disability Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Preventive Screenings. A review of studies on preventive screenings among women with physical disabilities found that physicians were less likely to inform women with disabilities than others without disabilities about the importance of preventive screenings, such as mammograms and Pap smears, and to make referrals for such screenings. The review found that these providers assumed that women with disabilities are less likely to develop cancer, are not sexually active, or are unable to undergo screenings because of their disability. These assumptions can lead to negative experiences that deter women with disabilities from obtaining preventive screenings.[23]

Reproductive care. The same review also found that social misconceptions might influence the delivery of care to people with disabilities. For example, the review found that some medical professionals assumed that women with disabilities did not wish, were incapable of, or should preferably not have children.

|

Quote “My doctor tried to force me to sign a ‘do not resuscitate’ order when I was not terminally ill, because she told me people with autism don’t have a good quality of life…But I did not agree I had a bad quality of life, and I didn’t want to die.” —An autistic person with several disabilities Source: Respondent to GAO survey. | GAO-26-107120 |

Patient-provider interactions. Both literature and stakeholders we interviewed described negative encounters with providers, influenced by perceived bias or stigma. For example, one study of autistic adults found that many perceived the providers they had encountered to be “insensitive and unaccommodating,” “challenging or refusing to acknowledge diagnoses,” or unwilling to adjust their methods to meet their patients’ individual needs. According to the study, “several autistic adults described experiences of being blamed for lack of treatment success.”[24]

In addition, one stakeholder described how if people with disabilities visit a provider accompanied by a support person, the provider may ignore the individual with the disability and talk exclusively to the support person.

Additional Barriers to Health Care

Accessibility barriers can be magnified for individuals with disabilities who face financial constraints or who have complex health care needs. For example:

· Availability of services. Several stakeholders stated that people with disabilities may face a lack of available services (e.g., health care providers in their area, specialists, and timely appointments). For example, according to one stakeholder, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities often have complex medical needs, and may find it difficult to find specialists, particularly in the field of mental health. Another stakeholder stated that, due to a lack of available in-home medical services, people with disabilities who require in-home services may not be able to find care. In addition, people with disabilities may face increased difficulty finding providers willing or able to provide accommodations that are necessary for them to receive care. For example, one stakeholder said that providers are not reimbursed for the additional time they may spend on patients with disabilities (such as longer appointment times or time writing paperwork for durable medical equipment), which causes providers to be less willing to take these patients, as they are seen as requiring extra work.

· Affordability. Stakeholders we interviewed gave examples of financial access barriers that may have a greater impact on people with disabilities. One stakeholder described how people with disabilities may have lower incomes and greater medical needs, which can impact the overall cost of their health care. For example, the National Council on Disability reported that inadequate health insurance could lead to people with disabilities paying additional out of pocket costs for items like wheelchairs, prescription drugs, sign language interpreters, or specialty care.[25] If these costs are too great, people with disabilities may delay care, skip medication, go without needed equipment, or go into debt. In 2021, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that 27 percent of households that had at least one member with a disability had medical debt, compared with 14 percent of households where no members had a disability.[26]

· Transportation. According to literature and stakeholder interviews, people with disabilities, who may need specialized transportation arrangements, such as paratransit, can face difficulty coordinating this transportation to attend medical appointments. For example, delays in arranged transportation may cause a person to be late for their appointment. Long wait times at a clinic may cause people to miss their arranged transportation home.

HHS Does Not Have a Focused Effort to Collect Data on the Accessibility of Health Care and Disability Status

HHS Does Not Have Plans to Collect National-Level Data from People with Disabilities on the Accessibility of Health Care

HHS does not collect national-level data on the accessibility of health care from people with disabilities, according to our analysis of selected HHS population health surveys, the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System, and interviews with HHS officials.[27] We reviewed 13 HHS data sources to determine if they included questions on the accessibility of health care, such as questions about limitations or barriers in a health care setting for people with disabilities. We identified one question on bias, which could provide information on a single type of barrier but not the full range of barriers that people with disabilities could experience.[28]

According to our analysis, several population health surveys that were identified by HHS officials included questions on health care access but not accessibility. Questions on health care access in selected surveys covered topics such as health insurance coverage, usual source of care, and emergency room visits. According to AHRQ, access to health care consists of four components: coverage, services, timeliness, and a qualified workforce.[29] Disability organizations and a researcher told us that access relates to barriers that can be faced by the broader population when seeking health care, while accessibility relates to barriers that are unique to people with disabilities. They also said that though the concepts of access and accessibility are sometimes conflated, it is important to address each as it relates to health care for people with disabilities.

HHS officials indicated they do not have plans to collect national-level data on the accessibility of health care from people with disabilities and provided various reasons why they do not collect these data. HHS officials from several offices stated that these population health surveys and the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System were not designed for the express purpose of identifying barriers to health care for people with disabilities. For example, officials at AHRQ stated that the sample size of people with disabilities in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey is too small to get reliable estimates on the accessibility of health care. Officials at three offices stated that adding questions to their surveys could increase the burden for respondents with disabilities or require the removal of questions more relevant to the survey target population. Officials at two offices stated that adding questions to their surveys involves outside entities in the review of plans and decision-making such as a work group of state coordinators, an expert committee, and universities that administer the surveys. Finally, an office who sponsors longitudinal surveys was concerned about the impact of new questions to the integrity of the survey data over time.

A researcher and disability organization we interviewed stated that HHS population health surveys are an important starting point to improve data collection for people with disabilities. According to HHS, population health surveys allow agencies to monitor and track health and health care information over time. HHS has previously collected data on a target population of people with disabilities in population health surveys:

· In 1994 to 1995 the National Health Interview Survey included supplemental questionnaires, called the National Health Interview Survey-Disability Survey, to collect disability data. The survey included questions on a range of topics for people with disabilities such as housing and long-term care services, transportation, and assistive devices and technologies.

· In 2014 to 2015, the Nationwide Adult Medicaid Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems was administered. It continues to be cited by CMS as a source of data on barriers to health care for people with disabilities such as issues with the approval, coverage, and payment for care.[30] However, according to our review, this survey did not explicitly address the accessibility of health care for people with disabilities.

Researchers and a disability organization that we interviewed were not aware of a question set on the accessibility of health care that HHS could readily adopt. However, HHS could leverage the existing research literature on barriers to health care for people with disabilities and its offices focused on disability research, such as the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, to inform this data collection effort. Researchers that we interviewed also acknowledged that collecting these data could be challenging for HHS since people with disabilities experience many types of barriers and have individualized needs for modifications in a health care setting. However, researchers we interviewed identified several key areas for data collection on the accessibility of health care from people with disabilities, such as physical spaces (e.g., medical equipment and facilities), digital health content (e.g., web content and electronic health records), and assistive technologies (e.g., communication devices).

HHS has acknowledged the importance of collecting data from people with disabilities to better understand the barriers to health care they experience and has established objectives for this data collection. First, the HHS Strategic Plan (Plan) states that to remove barriers to health care HHS will collect, use, and monitor data.[31] Second, the CMS Framework for Healthy Communities (Framework) includes priorities to increase access to health care services for people with disabilities and to expand the collection of standardized data.[32] In addition, federal internal control standards state that agencies should use quality information to achieve their objectives.[33]

However, HHS has not defined specific actions and timelines for meeting these goals. Federal internal control standards state that defining project objectives—such as through clear steps, goals, performance measures, and timelines—supports successful outcomes for the agency.[34] In addition, our prior work has found that consultation with stakeholders is a key practice when conducting evidence-building activities, such as assessing evidence needs and collecting and synthesizing data.[35]

Without detailed plans—that contain clear steps and timelines—for developing and piloting the collection of national-level data from people with disabilities on the accessibility of health care, HHS may not adequately track its progress or be held accountable for meeting its own strategic goals. These data would enable HHS to accurately identify and estimate the prevalence of accessibility barriers to health care and evaluate the effects of HHS regulations that cover nondiscrimination in health care for people with disabilities.[36]

HHS Does Not Consistently Collect Data on Disability Status

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Data Standard for Disability Status HHS selected the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey six questions on disability (ACS-6) as its data collection standard to identify people with disabilities in its population health surveys. The response options for all questions are yes/no. A yes response indicates a disability. 1. Are you deaf, or do you have serious difficulty hearing? (hearing) 2. Are you blind, or do you have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses? (vision) 3. Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions? (cognition) 4. Do you have serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs? (mobility) 5. Do you have difficulty dressing or bathing? (self-care) 6. Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have difficulty doing errands alone such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping? (independent living) Source: GAO analysis of HHS and Census Bureau documents. | GAO‑26‑107120 |

HHS has established a data standard for disability status to identify people with disabilities in their data collection efforts. However, HHS does not consistently collect data on disability status using its standard according to our analysis of selected HHS population health surveys and interviews with HHS officials. HHS selected the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey six questions on disability (ACS-6) as its data standard for disability status.[37] The ACS-6 asks questions about functional limitations in six domains (hearing, vision, cognition, mobility, self-care, and independent living) to identify people with disabilities.[38] A respondent who reports at least one difficulty is categorized as having a disability (see sidebar).

The HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status (Guidance) provides several requirements for the collection of these data in national population health surveys conducted or sponsored by HHS.[39] The Guidance states that these data collection standards be used, to the extent practicable, in all national population health surveys. The Guidance also states that these data collection standards represent a minimum standard and are not intended to limit an agency’s collection of needed data. The Guidance specifically notes that the question-and-answer categories for the ACS-6 cannot be changed.

We reviewed 12 HHS population health surveys conducted or sponsored by HHS and found that the collection of the HHS data standard for disability status in some surveys was inconsistent with the Guidance.[40] Specifically, seven of the 12 surveys did not include the ACS-6.[41] Five surveys did include the ACS-6; however, in four of those surveys, the ACS-6 questions or response options were modified (see table 1 below).[42]

Table 1: Collection of Disability Status Data in Selected Population Health Surveys Conducted or Sponsored by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as of May 2025

|

|

|

Collection of data standard on disability status |

|

|

HHS population health survey |

Responsible |

Does not use HHS standard |

Uses HHS standard |

|

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Core Component |

CDC |

- |

üa, b |

|

Health and Retirement Study |

NIA |

ü |

- |

|

Health Information National Trends Survey |

NCI |

ü |

- |

|

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component |

AHRQ |

- |

üb |

|

Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Community Questionnaire |

CMS |

- |

üa, b |

|

National Health and Aging Trends Study |

NIA |

ü |

- |

|

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

CDC |

ü |

- |

|

National Health Interview Survey Sample Adult Questionnaire |

CDC |

ü |

- |

|

National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System |

CDC |

- |

üb |

|

National Survey of Family Growth |

CDC |

ü |

- |

|

National Survey on Drug Use and Health |

SAMHSA |

ü |

- |

|

Nationwide Adult Medicaid Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems |

CMS |

- |

ü |

ü = Yes - = No

AHRQ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CMS: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

NCI: National Cancer Institute

NIA: National Institute on Aging

SAMHSA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Source: GAO analysis of selected HHS population health survey questionnaires. | GAO‑26‑107120

aModifies an ACS-6 question.

bIncludes yes/no and additional response options.

HHS officials provided several reasons why the ACS-6 was not used to collect data on disability status in seven population health surveys:

· Officials at the CDC stated that the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the National Health Interview Survey, and the National Survey of Family Growth use different measures of functional limitations that are more suited for the purpose of their data collection efforts. According to officials, it would be redundant and affect respondent burden to include the ACS-6 with the other measures of functional limitations.

· Officials from the National Cancer Institute stated that several of the ACS-6 constructs (e.g., hearing and vision) were assessed in the Health Information National Trends Survey but with different questions. They further explained that adding another measure that asks similar questions could confuse participants.[43]

· Officials at the National Institute on Aging stated that the Health and Retirement Study and the National Health and Aging Trends Study use other functional limitation questions that predate the ACS-6. According to officials, adding the ACS-6 or removing the existing questions on functional limitations could have negative consequences for maintaining longitudinal response rates.[44]

· Officials for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration stated that they revised the disability status questions in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health to be consistent with measures commonly used in the National Health Interview Survey.

Nonetheless, the Guidance specifically states that additional questions on disability may be added to a population health survey as long as the ACS-6 is included.

HHS officials also provided reasons why the ACS-6 was modified in some population health surveys. For example, officials at AHRQ and the CDC stated that response options (e.g., “refused” and “don’t know”) were added to be consistent with the other questions in their surveys. Officials from both offices stated that respondents rarely select the additional response options.

The HHS Plan and CMS Framework discuss the importance of improving the collection and use of data, including standardized data, to reduce health disparities. In the Plan, HHS states that it will establish a departmentwide approach to ensure that all HHS national surveys include disability status.[45] In the Framework, CMS states that it will expand the collection, reporting, and analysis of standardized data including individual-level demographic data.[46]

Without the consistent collection of data using its data standard for disability status, HHS may not meet its objective to improve the collection and use of data for people with disabilities as it relates to health. Researchers told us that consistent data collection by HHS would help to ensure there are sufficient data to examine the health and health care outcomes for people with disabilities, including by subgroup. Researchers and a disability organization also said that if HHS does not consistently collect data on disability status, HHS is limited in comparing its survey data across the department and to other federal datasets that use the ACS-6.

Furthermore, different measures for disability status can result in different national estimates of the number of people with disabilities, according to a review of Census data.[47] For example, research has found different estimates of the number of people with disabilities when two measures of disability status were both used in the National Health Interview Survey.[48] Relatedly, researchers said that some states are collecting disability data to better understand the health of people with disabilities in their states. Researchers told us that the Oregon Health Authority has adopted the HHS data standard for disability status in their data collection efforts. According to officials at the Oregon Health Authority, using the ACS-6 enables them to compare their data to federal data on people with disabilities (see text box).

|

Disability Data Collection Standards at the Oregon Health Authority Officials at the Oregon Health Authority told us that a state law required them to develop and implement disability demographic data collection standards. Officials said that the data collection standards serve a variety of purposes including the use of data for program administration and for research on health equity for people with disabilities. Officials also said that they are aligning the collection of disability demographic data with data on the needs for disability-related accommodations. Officials told us that their disability demographic data collection standards include the ACS-6 and three additional questions to identify subgroups of people with disabilities missed by the ACS-6. (Survey respondents are also asked to report their age of onset for each disability that they identified.) In 2024, the Oregon Health Authority expanded disability data collection to include an open-text field for a respondent to describe their disability or condition in their own words and a question on disability-related accommodations. The ACS-6 and the following questions are included under the functional difficulties section of their service-based questionnaire: · Do you have serious difficulty learning how to do things most people your age can learn? · Using your usual (customary) language, do you have serious difficulty communicating (for example, understanding or being understood by others)? · Do you have serious difficulty with the following: mood, intense feelings, controlling your behavior, or experiencing delusions or hallucinations? · If you identify as someone with a disability, or as having a physical, mental, emotional, cognitive, or intellectual condition, describe your disability or condition in any way you prefer. · If you identify as someone with a disability, or as having a physical, mental, emotional, cognitive, or intellectual condition, do you need or want disability-related accommodations? If yes, select all that apply and enter additional details below: alternate formats, building access, communication access (in-person, print materials, electronic), coordinating and scheduling care or services, environmental and sensory, equipment access, other staff support, not listed (specify). |

Source: GAO analysis of Oregon Health Authority documents and an interview with Oregon officials. | GAO‑26‑107120

Finally, modifying the ACS-6 in HHS population health surveys may affect the resulting data. The ACS-6 is a standardized measure, and according to a Census Bureau report, slight changes to the questions or answers in the ACS-6 could result in different estimates of the number of people with disabilities.[49] Additionally, according to leading practices for designing questionnaires, a change to questions or response options could negatively affect data reliability as well as the measure of change over time.

HHS Oversight and Information Sharing on Accessibility Are Limited

HHS Conducts Some Oversight of Health Care Organizations through CMS and OCR

Within HHS, CMS and OCR have mechanisms to oversee health care organizations and to assess the accessibility of health care for people with disabilities. CMS uses health and safety standards to oversee health care organizations, including with respect to accessibility. OCR investigates compliance with accessibility-related civil rights laws through compliance reviews, among other mechanisms.

CMS Health and Safety Standards

CMS uses an on-site inspection process—referred to as a survey—to ensure certain organizations participating in Medicare are compliant with its health and safety standards.[50] This inspection process is used to certify organizations to receive Medicare funding. CMS defines certain health and safety standards for Medicare-participating organizations.[51] Accrediting organizations and state agencies assess health care organizations’ compliance with CMS’s health and safety standards.[52] According to CMS, health and safety standards are the foundation for improving quality and protecting the health and safety of those receiving services and they cover topics such as staffing, patient rights, and quality review, among others.

Different types of health care organizations have separate sets of health and safety standards. There are separate standards for home health agencies, hospitals, and long-term care facilities, among others. CMS officials noted that these standards may not be uniform across all organization types because they reflect specific aspects unique to that organization type and population served.

CMS officials indicated that some standards pertaining to patient rights and the physical environment address accessibility. For example, home health agency standards state that information must be provided to patients in plain language and in a manner that is accessible and timely to people with disabilities. In addition, for hospitals, the standards state that condition of the physical plant and overall hospital environment must be developed and maintained to assure patient safety and well-being. CMS officials explained that surveyors are instructed to review the organization’s environmental risk assessment to determine how it plans to address any identified concerns regarding accessibility.

However, information on accessibility is not captured in a consistent manner. According to two interviewees involved in the survey process, the survey results do not categorize accessibility issues in a way that would allow CMS to track specific issues related to accessibility or Section 504. For example, as discussed earlier, patients with mobility disabilities may have issues being transferred safely. If identified on a survey, this issue could be categorized under patient rights, physical environment, or staff training, depending on the circumstances. As a result, it is difficult to ascertain from the survey process the extent to which accessibility issues are detected and addressed.

OCR Oversight Mechanisms

OCR has two primary mechanisms for overseeing compliance with accessibility-related civil rights laws: civil rights clearance reviews and compliance reviews.

Clearance reviews. OCR conducts civil rights clearance reviews of health care organizations applying to participate in Medicare Part A.[53] The clearance review process requires organizations to submit a form attesting to their compliance with civil rights laws.[54] The form states that the United States shall have the right to seek judicial enforcement of the assurance. OCR officials stated that they received about 7,000 of these forms in calendar year 2023.

OCR does not validate or assess the information collected from these forms. Prior to 2016, OCR reviewed entity policies as part of the approval process for becoming a participating Medicare provider. OCR officials stated that they no longer follow up or verify information once the organization submits the form. One stakeholder we interviewed noted that with respect to accessibility, when federal oversight relies heavily on provider attestation forms without validation, the information on the forms may not be accurate.

Compliance reviews. OCR conducts periodic compliance reviews, which are investigations of health care organizations to determine compliance with civil rights laws it enforces. OCR does not regularly review compliance with relevant regulations. However, OCR may initiate a compliance review due to a pattern of recurring, valid complaints about a particular organization, according to OCR officials. OCR may initiate a compliance review for other reasons, such as a priority by agency leadership or a media report. If OCR’s investigation reveals significant systemic noncompliance, OCR may negotiate a settlement agreement or voluntary resolution agreement, which includes OCR’s monitoring of the agreed-to corrective actions.

OCR has conducted some compliance reviews related to accessibility, but these have been limited in their reach. For example, OCR reported that from October 2019 through July 2025, it conducted a total of 65 compliance reviews, and 14 were focused on accessibility-related compliance. Of these 14 reviews, all were designated as “limited scope,” meaning they focused on a single health care organization or on a single issue. Correspondingly, their impact was also narrow. Specifically,

· Two resulted in changes after the entity took steps to address identified concerns.

· Two resulted in voluntary resolution agreements which included OCR’s monitoring of corrective actions.[55]

· Two resulted in no violation findings.

· Seven resulted in no further investigation.[56]

· One was administratively closed.

Further, OCR officials stated that its compliance reviews are typically desk reviews, meaning they are not conducted on-site at the organization. As such, these reviews do not assess an organization’s physical space, and therefore may miss physical or other barriers.

HHS Does Not Have Plans to Update Oversight Mechanisms In Light of Recent Regulations

On May 9, 2024, HHS issued a final rule to amend its Section 504 regulations, and this final rule includes additional accessibility requirements related to accessible communication and equipment.[57] The updated regulations went into effect in July 2024. Some of the requirements contain deadlines years into the future. For example, there is a requirement that by July 8, 2026, health care organizations receiving federal funding generally must have at least one examination table and weight scale that meet certain accessibility standards. In addition, organizations will be required to ensure that their web content and mobile applications are accessible by complying with specific technical standards.[58]

Disability stakeholder organizations, a health care organization, and other disability experts we interviewed told us that HHS oversight on health care accessibility has been limited and cited concerns about enforcing the new regulations. In the preamble to the final rule, HHS noted that it received many comments expressing concern about the lack of enforcement procedures in the proposed rule. Several stakeholders we interviewed noted that providers might not take proactive steps to improve accessibility if it is unclear how HHS would hold them accountable. They noted that further HHS efforts, including OCR enforcement, would help address barriers to accessible health care for people with disabilities, such as those identified earlier in the report. They provided examples of how such efforts could be improved, such as more on-site visits and guidance and information to health care organizations.

HHS’s efforts to oversee accessibility may be hindered because the agency does not have plans to enhance its efforts, either by updating existing oversight mechanisms or creating new ones, to help improve accessibility. OCR does not have plans to change its efforts under the new regulations. In addition, CMS officials stated they had no plans to update standards or survey guidance.

Both CMS and OCR cited reasons for not planning to update their current oversight mechanisms to reflect the new regulations. CMS officials reported that OCR—rather than CMS—has the primary responsibility to enforce civil rights laws. They said that CMS would be duplicating OCR efforts by including specifics pertaining to the Section 504 regulatory updates in its standards. However, CMS officials noted that their health and safety standards incorporate accessibility in some cases and that these standards are established through CMS’s own authority to establish health and safety standards for each organization type. OCR officials noted that the new regulations do not require changes to its process for conducting investigations or compliance reviews. They noted that any OCR enforcement actions under Section 504 will include monitoring of the applicable requirements in effect at the time of their enforcement activity. However, this approach would likely touch a limited number of organizations, depending on the number and extent of investigations conducted by OCR.

HHS has previously reported that increasing accessibility of health care is a priority. For example, the current HHS Plan included a specific objective to collaborate with others to remove barriers.[59] In addition, the current CMS Framework includes a priority on health care for people with disabilities. It states that people with disabilities need to be able to get health care services when and where they need them.[60] However, contrary to internal control standards, HHS has not fully established and operated monitoring efforts to achieve this objective.[61] Monitoring is essential in helping ensure that internal controls remain aligned with changing laws and risks, such as the Section 504 regulations.[62] Moreover, the Framework lacks specific steps for how the agency will work toward achieving its priority related to accessible health care. We have previously identified desirable characteristics of an effective, results-oriented plan, or components of sound planning practices, such as establishing goals and a strategy for achieving them, developing activities and timelines, involving stakeholders, and assigning responsible parties.[63]

CMS officials stated they intend to develop more detailed plans for the priorities in the Framework, but they did not provide time frames for this effort or further details on incorporating the recent Section 504 regulations. Without establishing detailed plans with timeframes to achieve its priorities related to accessible health care, HHS may not take appropriate steps to ensure that health care organizations are complying with accessibility requirements, including the recent regulations. Agency plans could strengthen mechanisms to ensure organizations are held accountable for complying with the new accessibility regulations and making their spaces and equipment accessible to people with disabilities.

OCR Does Not Routinely Compile or Share Summary Information on Accessibility-Related Complaints and Compliance Reviews

OCR does not routinely compile or share summary data on the findings of its complaint investigations and compliance reviews related to accessibility. OCR officials stated that they may review summary data for all complaints at the end of the fiscal year but do not routinely do so. They also said they do not share summary data with other HHS entities on the findings of the complaint investigations. Regarding compliance reviews, OCR officials indicated that the office neither prepares reports on compliance review results nor routinely shares data on their results. OCR officials stated that they coordinate with some HHS operating divisions regarding individual investigations and share information with CMS under limited circumstances.[64] OCR has also shared some information, via its website and email distribution list, on individual voluntary resolution and settlement agreements, including those related to accessibility.

Officials cited competing priorities, as well as the functionality of OCR’s case management system, as reasons why they do not compile or share such data. Specifically, they said that the current case management system, which tracks complaints and compliance reviews, lacks functionality to readily produce certain summary reports. For example, although OCR maintains information in its files on the rationale for initiating compliance reviews, officials were unsure whether this information could be compiled into a report. Officials said that producing such reports in the current case management system would require some time to develop, and that this has not been a priority.

However, as of fiscal year 2022, OCR had begun to revise its case management system. Specifically, it plans to improve the system’s ease of use and enhance its capacity for reporting and analytics. In March 2025, OCR reported that it had not yet finalized details related to data collection for the new system. OCR expects to launch its new case management system by early fiscal year 2027.

Data on OCR-resolved compliance reviews and complaints could be beneficial to health care organizations, and the public. Summary data would provide timely information on common issues where health care providers may have confusion or face challenges in meeting accessibility requirements in federal laws. For example, OCR officials stated that for resolved complaints, those that involve disability issues could be further broken down into sub-categories to identify accessibility-related issues, such as effective communication or issues with physical accessibility. OCR officials provided information describing categories that help identify accessibility-related compliance reviews, including categories by statute (e.g., Section 504 or Section 1557), and aspects such as interpreters and program accessibility. Identifying these common issue areas could help determine needs for technical assistance or training to health care organizations more broadly.

Moreover, sharing summary data on resolved complaints and compliance reviews could help health care organizations and others understand where they could improve accessibility. As described above, researchers and others we interviewed noted that HHS does not collect national-level data from individuals with disabilities on barriers to accessible health care. Complaint data reflect potential vehicles through which accessibility could be improved on a broader scale.

In addition, one stakeholder organization noted that people with disabilities may lack confidence in the complaint process because there is generally little follow up to complaints. The Office of Management and Budget’s Open Government Directive explains that increasing transparency by expanding access to information promotes accountability.[65] Summary data on resolved accessibility complaints could bolster confidence in the process.

Federal standards for internal controls state that management should use and externally communicate quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Without developing a mechanism to compile summary data on accessibility-related complaints and reviews, OCR is missing an opportunity to make data-driven decisions on how to enhance accessibility in health care. Moreover, without sharing such summary data externally, OCR may lose an opportunity to broaden the impact of its efforts to health care organizations beyond those it works with directly.

OCR Does Not Have Time Frames for Sharing Additional Information and Guidance on Accessibility Requirements for Health Care Organizations

OCR shares some information publicly regarding accessibility issues but does not have timeframes for providing additional guidance to health care organizations on how to operationalize the changes to accessibility requirements. According to HHS’s fiscal year 2025 congressional budget justification, OCR ensures compliance with civil rights laws by investigating complaints and conducting compliance reviews, requiring corrective action, issuing policy and regulations, and providing technical assistance and public education.

When HHS updated its Section 504 regulations in May 2024, OCR took steps to disseminate information about these regulations. For example, in fall 2024, OCR conducted outreach through OCR regional offices, who used methods including webinars and in-person outreach to share information about the regulations. In January 2025, OCR issued a “Dear Colleague” letter to inform health care organizations of their responsibilities under the Section 504 regulations.[66] OCR has also issued fact sheets that discuss aspects of the regulations, such as new requirements for the accessibility of medical diagnostic equipment and web content, mobile apps, and kiosks, and relevant definitions and exceptions to the requirements.[67]

Despite these efforts, stakeholders we spoke with stated that health care providers may still be unsure of how to operationalize accessibility-related requirements. For example, two interviewees said some health care organizations have found the requirements for the number and location of accessible medical equipment in a facility unclear. Several disability and health care organizations told us that health care leaders were unaware of the key provisions of the new Section 504 regulations and the extent of changes that would be required. For example, a representative from one stakeholder organization stated that small health care organizations may not know how to purchase accessible medical equipment or how to make their websites and telehealth platforms accessible.

As of July 2025, OCR’s website does not include further guidance, training or other materials to help health care organizations understand their new Section 504 obligations. For example, OCR web pages labeled ‘Provider Obligations’ and ‘Resources for Covered Entities’ do not contain any information on additional requirements, such as accessible examination tables and web content. The website also lists two trainings relevant to health care for people with disabilities, but the links are broken.[68] In addition, the fact sheets described earlier are located on a section of OCR’s website labeled ‘Information for Individuals’ and may not be readily located by health care organizations seeking information about Section 504. Moreover, while these fact sheets provide details on some aspects of the regulations, other aspects—such as the prohibition on limiting medical treatment based on bias about disability—have not received similar detailed coverage.

According to OCR, there are no specific timeframes for providing additional guidance. OCR officials noted that several requirements in the Section 504 regulations have deadlines that have not yet passed. However, the Dear Colleague letter urges health care organizations to take steps to understand the new requirements and ensure they are compliant before their effective dates to avoid inadvertent discriminatory acts that result in enforcement actions by OCR. In April 2025, OCR officials stated they were reviewing website materials to determine what can be added to their website, but did not provide a timeframe for completing this effort.

Federal standards for internal controls state that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[69] Selecting the appropriate method to communicate externally and ensuring the information is readily available to the audience, can contribute to the effectiveness of this effort. Without providing sufficient and readily available guidance, OCR runs the risk that health care organizations will not take appropriate steps to comply with the Section 504 regulations.

Conclusions

People with disabilities can face numerous barriers which may negatively affect the quality, timeliness, and safety of their health care. Some providers have taken steps to address these barriers, such as documenting accommodation needs and enhancing provider training.

HHS does not have plans to collect national-level data from people with disabilities on the accessibility of health care. Federal data on this topic is important for HHS and others to help understand and address the barriers people with disabilities experience in health care settings. Detailed plans with steps and timelines for developing and piloting such data collection would help ensure the agency tracks progress towards meeting its goals to reduce barriers to health care for people with disabilities. In addition, with more consistent efforts to collect data on disability status, HHS could better identify and monitor the health and health care outcomes of people with disabilities.

HHS conducts some oversight of health care organizations regarding accessibility and has acknowledged the importance of addressing health care needs of people with disabilities. However, the agency has not determined how to continue making progress in this area. Developing robust agency plans that incorporate sound planning practices, would help HHS establish a road map to achieve its priorities related to accessible health care. Without such plans, HHS may not take appropriate steps to ensure that health care organizations are held accountable for complying with the new accessibility regulations and making their facilities and equipment accessible to people with disabilities.

As HHS’s enforcement entity regarding accessibility, OCR maintains information regarding compliance of health care organizations with accessibility requirements. Developing a mechanism to compile and publicly share summary data on accessibility-related complaints and compliance reviews would help OCR identify the most frequent concerns about accessibility and better target its enforcement and other efforts. OCR’s updated case management system offers an opportunity to add this functionality.