PUERTO RICO

IRS Should Improve Oversight of Taxpayers Claiming Exemption from Federal Taxes

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: James R. McTigue, Jr. at McTigueJ@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

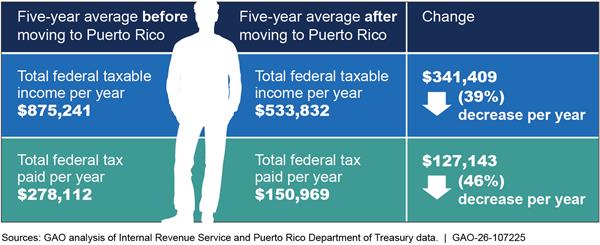

In 2021, the most current year for which GAO had complete data, there were approximately 2,200 recipients of the Puerto Rico resident investor tax incentive. GAO’s analysis found a significant decrease in the average federal taxable income and federal taxes paid by this population between the 5 years prior to and up to 5 years after moving to Puerto Rico (see figure). GAO’s analysis found that the decrease in federal tax revenue in aggregate could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

Note: Dollar amounts are inflation-adjusted 2023 dollars.

Additionally, from 2012 through 2024, almost 4,000 taxpayers received Puerto Rico’s business export service tax incentive. The effect of the resident investor and business export service incentives on Puerto Rico’s economy is difficult to isolate as the evidence is mixed on the overall costs and benefits. This is, in part, due to recipients representing a small fraction of Puerto Rico’s population. Some economic studies undertaken for the Puerto Rico government suggest an increase in economic activity and employment related to the tax incentives while local perspectives and migration data suggest mixed results.

In 2021, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced a compliance initiative, called a campaign, to address concerns that some recipients of Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive may not be meeting their federal tax obligations. The campaign only recently began showing results, in part, due to the complexity of high-income and high-wealth audits, IRS not prioritizing the effort, and communication gaps between IRS and Puerto Rico. Until 2025, IRS was unable to obtain complete data on taxpayers claiming Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive with Social Security numbers to help ensure compliance with federal tax laws. Further, IRS has no documented plan to routinely acquire the most current data from Puerto Rico going forward. Obtaining such data regularly would improve IRS’s ability to ensure compliance.

Additionally, IRS did not pursue referrals from Puerto Rico government officials who identified U.S. taxpayers whom officials could not confirm met Puerto Rico’s residency requirement. IRS also does not have a plan to prioritize any future referrals. GAO analyzed these referrals along with IRS data and identified taxpayers with indicators of potential noncompliance with federal tax law, which GAO shared with IRS. Establishing procedures to review cases of potential noncompliance identified by Puerto Rico government agencies could help IRS improve federal tax compliance.

Why GAO Did This Study

In 2012, Puerto Rico enacted the resident investor (Act 22) and export service business (Act 20) tax incentives to encourage relocation to and investment in Puerto Rico. Federal law generally exempts residents of Puerto Rico from federal income tax on income sourced from Puerto Rico. IRS is responsible for ensuring that taxpayers claiming Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive are meeting their federal tax obligations.

GAO was asked to review the Puerto Rico resident investor and export service business tax incentives. This report (1) describes the population receiving tax incentives, (2) describes selected economic effects of these tax incentives on Puerto Rico’s economy, and (3) assesses IRS efforts to ensure compliance among U.S. persons relocating to Puerto Rico and claiming residency.

GAO analyzed IRS and Puerto Rico documentation and data and interviewed relevant officials. GAO also interviewed local officials, economic development firms, and stakeholder groups.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to IRS, including that it establish procedures to regularly obtain data on all taxpayers claiming Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive and procedures to review cases of potential noncompliance referred to IRS by Puerto Rico government agencies. IRS agreed with all three of the recommendations.

Abbreviations

|

AGI |

adjusted gross income |

|

DDEC |

Puerto Rico Department of Economic Development and Commerce (known by its abbreviation in Spanish) |

|

GDP |

gross domestic product |

|

GNP |

gross national product |

|

Hacienda |

Puerto Rico Department of Treasury (known by its name in Spanish) |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

SSN |

Social Security number |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 8, 2025

The Honorable Jared Huffman

Ranking Member

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

The Honorable Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ritchie Torres

House of Representatives

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

House of Representatives

Taxpayers moving to Puerto Rico may be eligible for exemptions from both federal and Puerto Rico taxes. Specifically, federal law generally exempts residents of Puerto Rico from federal income tax on income sourced from Puerto Rico. In 2012, Puerto Rico enacted resident investor and export service business tax incentives to encourage relocation to and investment in the commonwealth. These incentives give eligible residents of Puerto Rico preferential tax treatment on investment income.[1] The resident investor incentive could be particularly appealing to high-net-worth individuals whose income is primarily based on investments, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is responsible for ensuring that taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive are meeting their federal tax obligations. In 2021, IRS implemented a compliance initiative—called a campaign. In May 2024, former IRS Commissioner Werfel publicly acknowledged the campaign’s initial progress was slow. In addition, an anonymous person who identified themself as an IRS employee alleged in a letter to members of Congress that mismanagement of the campaign led to a lack of results. In summer 2024, Democratic staff of the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance opened its own investigation into oversight of the exemptions.

You asked us to review the Puerto Rico resident investor and export service business tax incentives. This report (1) describes the population of individuals and businesses receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export service business tax incentives, (2) describes selected economic effects of Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export service business tax incentives on Puerto Rico’s economy based on available data, and (3) assesses IRS efforts to ensure compliance among U.S. persons relocating to Puerto Rico and claiming residency.

To address these objectives, we reviewed documents produced by IRS and multiple government agencies in Puerto Rico. We analyzed data from the Puerto Rico Department of Economic Development and Commerce (known by its acronym in Spanish, DDEC), the Puerto Rico Department of Treasury (known by its name in Spanish, Hacienda), and IRS to identify the number of individuals holding resident investor and export service decrees. We also used these data to identify the number of resident investor incentive recipients in a particular tax year and to determine their average annual income and taxes due before and after moving to Puerto Rico. We used these same data sources to determine information such as the states from which resident investor incentive recipients moved and the number of individuals who notified IRS that they were moving to Puerto Rico.

We reviewed publicly available data on economic activity and housing trends in Puerto Rico and reviewed studies of the economic effects of the tax incentives. We also conducted site visits to Puerto Rico and interviewed government officials, researchers, economic development firms, and stakeholder groups about the effects of the tax incentives. Additionally, we interviewed local officials from a nongeneralizable selection of municipalities. We selected Aguadilla, Dorado, Rincón, and San Juan because officials told us that a large number of resident investor incentive recipients lived in these municipalities.

To analyze how the campaign was designed and managed, we interviewed IRS officials, including those who manage the campaign. We also reviewed testimonial evidence about changes to the campaign that occurred over time, data on the number of cases opened and closed, data on the outcomes of those cases, and steps the campaign was taking beyond audits to promote compliance.

In addition, we met with Puerto Rico government officials responsible for Puerto Rico tax administration, decree oversight, and communication with IRS. We analyzed communications between IRS and the government of Puerto Rico related to the exchange of tax data between the agencies. We compared IRS’s actions in this area to the existing coordination agreement between the federal government and Puerto Rico, applicable sections of the Internal Revenue Manual, the campaign’s objectives, the rights outlined in the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, and leading practices for enhancing interagency collaboration.[2] We also reviewed cases of potential noncompliance identified by DDEC and have shared the results of our analysis with IRS. A more detailed discussion of our methodology is included in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Puerto Rico Economy

Puerto Rico’s economy lags that of the United States as a whole, with lower median incomes and overall economic growth.[3] In addition, doing business in Puerto Rico can be more expensive compared to the mainland. One reason for the higher expense is residential energy prices that are consistently higher in Puerto Rico than the U.S. average (see fig. 1). Additionally, the Puerto Rico electric grid remains unstable and residents lose power more often than any state, according to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico.[4]

Historically, the U.S. federal government has provided tax incentives specific to Puerto Rico, with the goal of promoting economic growth in the commonwealth. This included Section 936, enacted as part, of the Tax Reform Act of 1976, which provided eligible corporations an exemption for the full amount of federal taxes related to income from operations in Puerto Rico.[5] Section 936 was phased out over 10 years beginning in 1996. Since then, the government of Puerto Rico has offered several tax incentives intended to promote economic activity in the commonwealth.

Puerto Rico Tax Incentives and the Federal Tax Exemption

The resident investor incentive and the export service business incentive are two of Puerto Rico’s local tax incentives, originally enacted in 2012 under Acts 22 and 20. Both incentives are now part of chapters 2 and 3 respectively of Puerto Rico’s Incentives Code, commonly known as Act 60, enacted in 2019.[6] Taxpayers may receive both the Puerto Rico incentives and a federal tax exemption on Puerto Rico sourced income, if they meet the requirements for both, thereby increasing the tax advantage of relocating to Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico Resident Investor Incentive

Under the law establishing the resident investor incentive, DDEC issues decrees to eligible individuals that provide the taxpayer with favorable rates on their Puerto Rico income taxes if that taxpayer relocates to Puerto Rico (see fig. 2).[7] These decrees serve as individual contracts between the taxpayer and the Puerto Rico government. Generally, the decree grants a

· 100 percent exemption from interest and dividends, as well as certain net capital gains, accrued after moving to Puerto Rico, and

· fixed income tax rate of 5 percent on certain Puerto Rico capital gains accrued before moving to Puerto Rico and realized after 10 years of residency.[8]

Eligible individuals must meet annual requirements, including moving to Puerto Rico, maintaining residency in Puerto Rico, and filing an annual report with DDEC. Taxpayers need to live in Puerto Rico for more than half the year (183 days) to meet Puerto Rico’s residency requirement.[9] According to one Puerto Rico official, Puerto Rico structured its residency requirement such that taxpayers who reside in Puerto Rico for 183 days per year would generally meet both Puerto Rico and federal requirements. In recent years, DDEC has also required recipients of the resident investor incentive to make an annual $10,000 donation to a nonprofit organization in Puerto Rico.[10]

Figure 2: Key Federal and Puerto Rico Tax Benefits and Requirements Available to Resident Investor Incentive Recipients

Puerto Rico Export Service Business Incentive

Puerto Rico offers tax incentives to businesses engaged in export services. As with the resident investor incentive, DDEC issues decrees to eligible businesses. The decree grants favorable rates on their Puerto Rico tax obligations, including a 4 percent fixed income tax rate and a 100 percent tax exemption from dividend or profit distributions.

To qualify for the Puerto Rico export service business incentive, a business must operate through an office located in Puerto Rico and perform services for foreign entities or individuals without a connection to domestic business in Puerto Rico. Some examples of export service businesses that could qualify include call centers, asset management firms, and data centers.

Although this tax incentive is not directly related to the resident investor incentive, many resident investor incentive recipients also own businesses with export service decrees.[11]

Federal Tax Exemption

Federal law generally exempts bona fide residents of Puerto Rico from federal income tax on income sourced from Puerto Rico.[12] To qualify as a bona fide resident of Puerto Rico for federal tax purposes, taxpayers must meet a three-part test.[13] Specifically, they must

· not have a tax home outside of Puerto Rico,[14]

· not have a closer connection to the United States or to a foreign country than to Puerto Rico,[15] and

· meet the presence test (see sidebar).

|

Internal Revenue Service Presence Test Taxpayers meet the federal presence test for the tax year if they meet one of the following conditions. · They were present in the territory for at least 183 days during the tax year. · They were present in the territory for at least 549 days during the 3-year period that includes the current tax year and the 2 immediately preceding tax years. During each year of the 3-year period, they must also be present in the territory for at least 60 days. · They were present in the United States for no more than 90 days during the tax year. · They had $3,000 or less of earned income from United States sources and were present for more days in the territory than in the United States during the tax year. · They had no significant connection to the United States during the tax year. Source: Internal Revenue Service. | GAO‑26‑107225 |

While the federal government and Puerto Rico offer different tax benefits with different requirements, elements of the residency requirements overlap. Taxpayers meeting the Puerto Rico resident investor incentive requirement to reside in Puerto Rico for at least 183 days per year would generally meet IRS’s presence test.

IRS’s Oversight of Taxpayers Claiming Puerto Rico Residency Under the Incentive Program

IRS has no oversight authority over the resident investor and export service business tax incentives offered by Puerto Rico’s government, including whether a taxpayer has satisfied the residency requirements under Puerto Rico law. However, IRS is responsible for administering and enforcing U.S. tax law. For individuals, this includes IRS verification of compliance with federal residency requirements that grant federal income tax exemption from income sourced from Puerto Rico. Corporations organized under the laws of Puerto Rico are considered foreign corporations for U.S. tax purposes and are subject to the same oversight as other foreign corporations.

One way IRS works to improve compliance is through compliance projects known as campaigns. IRS campaigns address a specific issue area that IRS has identified as presenting a high risk of noncompliance. In January 2021, IRS announced the launch of a compliance campaign to address concerns that taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor tax incentive could be:

· improperly excluding income subject to U.S. tax on an income tax return,

· failing to file a required tax return reporting income subject to U.S. taxes, or

· improperly reporting U.S.-sourced income as Puerto Rico-sourced income to evade taxation.

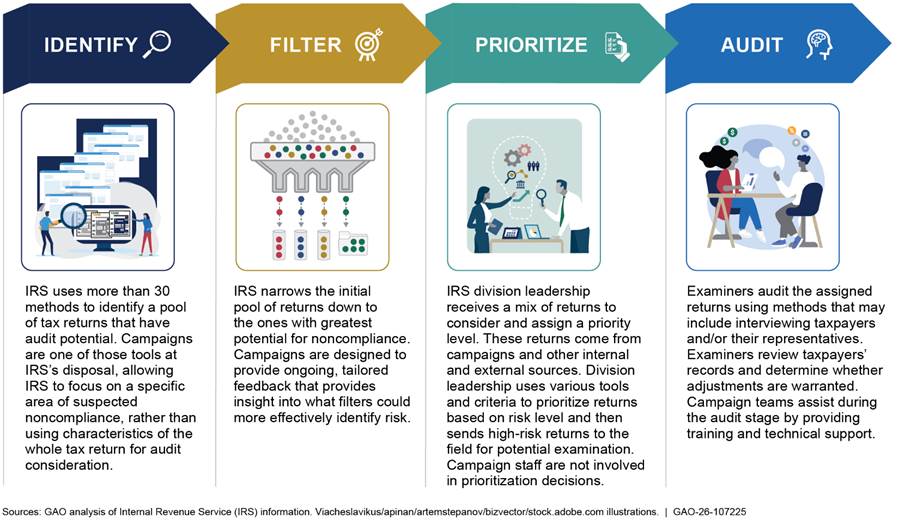

IRS’s Puerto Rico Act 22 Campaign was one of 46 active Large Business and International campaigns that IRS had in place as of July 2025. According to IRS, the objective of this campaign is to address noncompliance in this area through a variety of means including examinations, outreach, and education letters. The campaign is designed to have a role throughout the audit process (see fig. 3).

Thousands of Individuals Received Tax Incentives to Move to Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Granted More than 5,800 Resident Investor and Nearly 4,000 Export Service Business Incentive Decrees from 2012 Through 2024

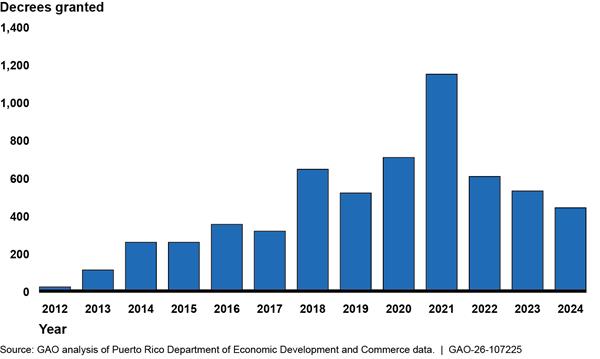

Resident investor decrees. Puerto Rico granted a total of 5,852 resident investor decrees from 2012 through 2024, with the largest number of decrees granted in 2021 (see fig. 4 below).[16] The number of decrees granted peaked in 2021, coinciding with the increase in teleworking following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recipients of these decrees are the taxpayers potentially eligible to receive federal tax exemptions and Puerto Rico tax incentives and who are the subject of IRS’s compliance campaign.

Not everyone who received decrees made use of them. In 2021, there were 2,236 Puerto Rico tax returns filed with a resident investor decree, but more than 4,200 resident investor decrees had been granted at that time, according to data from DDEC and Hacienda. From 2021 to 2023, taxpayers filed more than 2,200 Puerto Rico tax returns each year and 3,165 unique primary taxpayers filed with a resident investor decree on their Puerto Rico tax returns across the 3 years, as shown in table 1.

|

Year |

Puerto Rico returns filed with a resident investor decree |

|

2021 |

2,236 |

|

2022 |

2,520 |

|

2023 |

2,302 |

|

Total unique |

3,165 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Puerto Rico Department of Treasury. | GAO‑26‑107225

aThe total is the number of unique primary taxpayers (individuals listed as the taxpayer and not the spouse on their tax returns) claiming the resident investor incentive across the 3 years. The total is not the sum of the years because some taxpayers were incentive recipients for multiple years. The analysis of total unique primary taxpayers is based on June 2023 data. Puerto Rico updated its data in June 2025 to identify 10 additional returns across 2022 and 2023. These 10 returns are included in the counts for those years but not included in the total number of unique primary taxpayers. Additionally, in 2021, 2022, and 2023, Hacienda identified 156, 192, and 444 returns, respectively, on which both the taxpayer and spouse claimed the resident investor incentive on the same return.

DDEC can terminate a resident investor decree if it finds that the decree holder is not meeting requirements, for example if the taxpayer does not reside in Puerto Rico for 183 days per year. Officials noted that while certain requirements can be remediated—for example, in some cases, the requirement to file an annual report can be met by filing late—failing to meet the residency requirement cannot be corrected after the fact.

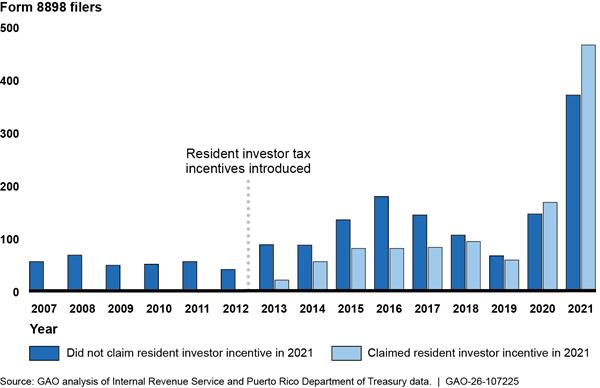

All U.S. taxpayers—not just resident investor incentive recipients—who are establishing bona fide residency and earning more than $75,000 must file Form 8898 for that year, Statement for Individuals Who Begin or End Bona Fide Residence in a U.S. Possession, with IRS.[17]

The number of individuals beginning bona fide residency may be lower than the number of decrees granted if, for example, a decree was not used or the resident investor incentive recipient simply did not file Form 8898 with IRS when they should have filed it. From 2012 through 2023, a total of 3,108 individuals had filed Form 8898 with IRS indicating they were changing their residency to Puerto Rico. In each year since 2013, more individuals have been granted decrees than have filed Form 8898 declaring residency in Puerto Rico (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Annual Counts of New Resident Investor Decrees Granted and Individuals Filing Form 8898 Declaring Bona Fide Residency in Puerto Rico, 2012-2023

Based on our analysis of resident investor incentive recipients who claimed the incentive in 2021, we found that only half filed a Form 8898 telling IRS they had changed their residency to Puerto Rico. According to IRS officials, some high-net-worth individuals who know that they will not satisfy the test for bona fide residency may choose not to file a Form 8898 with IRS because the $1,000 penalty for failing to notify IRS is low compared to the tax benefit they are receiving. Conversely, some high-net-worth individuals may be exempt from the requirement to file Form 8898 because they fall below the $75,000 income threshold. This can happen if a taxpayer chooses not to realize large unrealized capital gains until some future tax year after relocating to Puerto Rico.

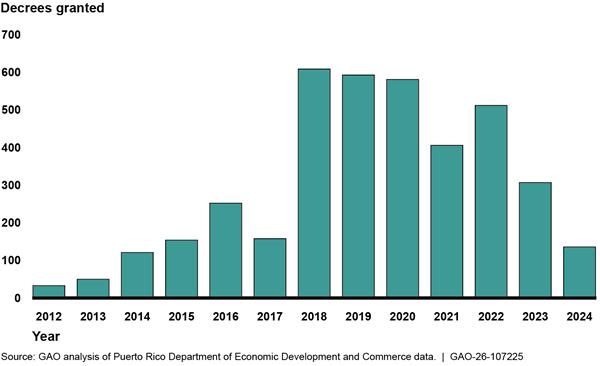

Export service decrees. Since 2012, DDEC has granted 3,899 export service decrees (see fig. 6).[18] To receive this decree, businesses must operate through an office located in Puerto Rico and must perform services for foreign individuals or entities that do not have any nexus (e.g., business connection) to Puerto Rico. Our analysis indicates that at least 529 of the 2,201 active resident investor incentive recipients in 2021 (24 percent) also had an export service business decree in 2022.

Incentive Recipients’ Federal Taxes Paid Decreased Sharply After Moving to Puerto Rico

Resident investor incentive recipients were disproportionately high-income taxpayers (see fig. 7). We found the adjusted gross income (AGI) of resident investor incentive recipients prior to moving was about $900,000.[19] At the highest income levels, we found that 17.4 percent of resident investor incentive recipients reported an average AGI of $1 million or more, including 1.5 percent with an average AGI of $10 million or more.[20] This compares to 0.5 percent of all U.S. taxpayers with a reported average AGI of $1 million or more and 0.02 percent who had an average AGI of $10 million or more.

Figure 7: Income of All U.S. Taxpayers and Taxpayers Receiving the Puerto Rico Resident Investor Tax Incentive

Notes: The income of taxpayers who received the resident investor incentive is based on the inflation-adjusted average of their federal adjusted gross incomes in the 5 years prior to relocating to Puerto Rico for those who claimed the incentive on their Puerto Rico tax returns in 2021. The U.S. taxpayer distribution is based on data in the Internal Revenue Service 2022 Statistics of Income Individual Complete Report. Dollar amounts are inflation-adjusted 2022 dollars.

We also found that 11 percent of resident investor incentive recipients reported average AGIs that were negative or $0. For taxpayers with negative AGIs, total positive income can provide additional insight into taxpayers’ financial situations.[21] AGI accounts for certain expenses, deductions, and other adjustments which can be used to lower total income. For this reason, even taxpayers with low or negative AGIs may have relatively high total positive income.

For example, taxpayers could have significant income from capital gains, which would be included in their total positive income, but have even larger business losses, which would offset the income in their AGIs. This is consistent with our finding that the 5 percent of taxpayers who reported negative average AGIs also reported average positive income. These taxpayers reported average positive incomes of just over $960,000 and average AGIs of negative $1.2 million.

When considering the effect of resident investor incentive recipients moving to Puerto Rico on federal taxes, total federal taxable income and federal tax paid provide key insights.[22] Based on our analysis, the average federal taxable income and federal taxes paid by resident investor incentive recipients decreased significantly after they moved to Puerto Rico. Specifically, we found:

· average annual federal taxable income decreased by $341,409 (39 percent) from $875,241 to $533,832, adjusting for inflation; and

· average annual federal tax paid decreased by $127,143 (46 percent) from $278,112 to $150,969, adjusting for inflation (see fig. 8).

In aggregate, the decrease in federal tax revenue from this population could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.[23]

Figure 8: Average Total Federal Taxable Income and Total Federal Taxes Paid by Taxpayers Receiving the Puerto Rico Resident Investor Tax Incentive

Note: Dollar amounts are inflation-adjusted 2023 dollars.

Our analysis found that resident investor incentive recipients move to Puerto Rico from a range of U.S. states (see table 2).[24] Among those for whom we could identify the state from which they moved, about 57 percent moved from California, Florida, New York, or Texas, the four most populous U.S. states.[25]

|

State |

Number |

Percent |

|

California |

381 |

19.9 |

|

Florida |

290 |

15.1 |

|

New York |

254 |

13.2 |

|

Texas |

174 |

9.1 |

|

New Jersey |

86 |

4.5 |

|

Illinois |

79 |

4.1 |

|

Nevada |

75 |

3.9 |

|

Colorado |

52 |

2.7 |

|

Massachusetts |

50 |

2.6 |

|

Arizona |

48 |

2.5 |

|

Washington |

46 |

2.4 |

|

Georgia |

45 |

2.3 |

|

Pennsylvania |

42 |

2.2 |

|

Virginia |

40 |

2.1 |

|

Connecticut |

33 |

1.7 |

|

Utah |

30 |

1.6 |

|

North Carolina |

27 |

1.4 |

|

Tennessee |

27 |

1.4 |

|

Maryland |

24 |

1.3 |

|

Oregon |

24 |

1.3 |

|

Michigan |

19 |

1.0 |

|

Ohio |

15 |

0.8 |

|

Minnesota |

13 |

0.7 |

|

Washington, D.C. |

11 |

0.6 |

|

Missouri |

11 |

0.6 |

|

Wisconsin |

11 |

0.6 |

|

South Carolina |

10 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

1,917 |

100% |

Source: GAO analysis of data from Internal Revenue Service and the Puerto Rico Department of Treasury. | GAO‑26‑107225

Note: This analysis starts with the population of resident investor incentive recipients who claimed the incentive on their 2021 tax returns filed with the Puerto Rico Department of Treasury. The tax return data include the year that they established residency in Puerto Rico. For these taxpayers, we identified the most recent U.S. state that the taxpayers used for their addresses on IRS Form 1040 prior to the year they established bona fide residency in Puerto Rico. For the purpose of this analysis, we included Washington, D.C. and excluded U.S. territories. Missing data, non-U.S.-state locations, and states with fewer than 10 former residents are excluded. Percentages add up to 100.1 due to rounding.

Tax Incentives’ Effect on Puerto Rico’s Economic Growth Is Difficult to Determine

Overall Economic Activity in Puerto Rico Has Remained Relatively Flat over the Past Decade

The federal government and the government of Puerto Rico forgo revenue from taxpayers receiving the resident investor and export service business tax incentives. The favorable tax rates offered by Puerto Rico are intended to generate economic activity to offset the forgone revenue. There are multiple sources of information that provide insight into economic activity in Puerto Rico in the years following the introduction of the resident investor and export servics business tax incentives. Two key indicators that we considered are trends in economic growth and trends in the housing market. Macroeconomic events, including two hurricanes, a series of earthquakes, and the global COVID-19 pandemic, also affected these indicators over the last decade.

Puerto Rico’s Economic Growth in Recent Years

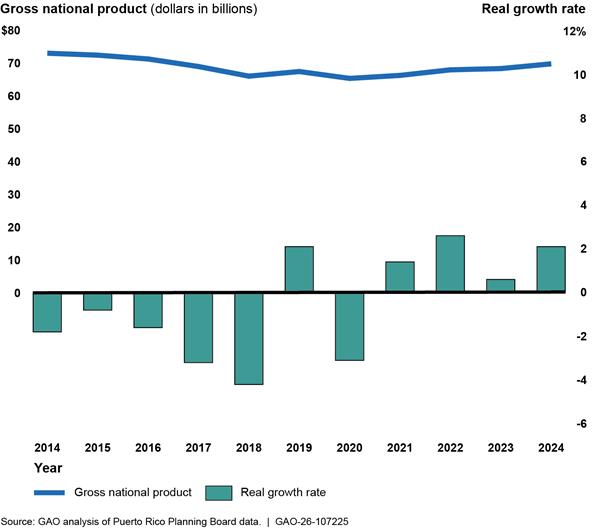

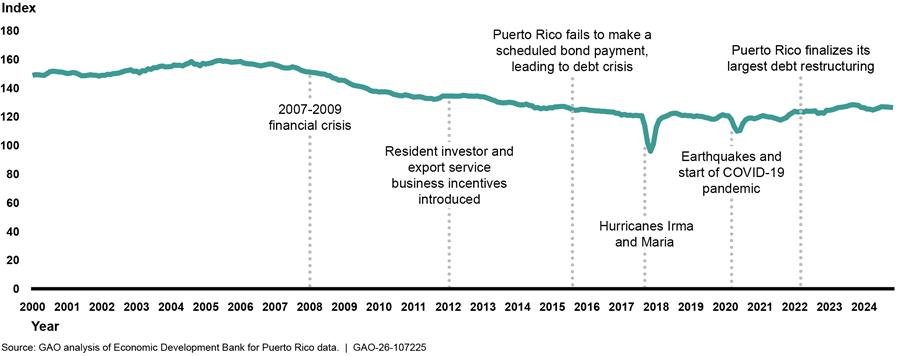

In real terms, Puerto Rico’s economy has shown little or no growth since the resident investor and export service business tax incentives were first introduced in 2012, but it is not possible to measure what growth or decline would have been without the incentives. Real gross national product (GNP) in Puerto Rico is 4.4 percent lower in 2024 than it was in 2014, but growth was positive in 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024, as shown in figure 9.[26]

Other economic indicators also show a lack of economic growth in the last decade. The Economic Development Bank of Puerto Rico devised the Economic Activity Index to measure general economic activity in Puerto Rico, with higher numbers representing greater economic activity. As shown in figure 10, economic activity has fluctuated in response to various events but has shown little growth over time. The index in November 2014 was approximately the same as it was in November 2024, the most recent date for which the information was available at the time of our analysis.

The economic effects of natural disasters, the pandemic, and subsequent federal funding make it difficult to isolate the effect of the resident investor and export service business incentives on the Puerto Rico economy. Throughout the last 10 years, Puerto Rico’s economy has been significantly affected by macroeconomic factors, including the debt crisis that began in 2015, Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, a series of earthquakes in December 2019 and January 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The hurricanes caused billions of dollars in damage to Puerto Rico’s infrastructure, housing, and economy. For example, the hurricanes severely damaged Puerto Rico’s electric grid, resulting in an 11-month blackout that was the longest in U.S. history and complicated recovery efforts following the storms.

The hurricanes, earthquakes, and COVID-19 pandemic were followed by an influx of federal funds for disaster relief and pandemic response, which have contributed to economic growth in Puerto Rico. For example, as of 2023, the Federal Emergency Management Agency had awarded about $23.4 billion in Public Assistance to Puerto Rico’s permanent recovery work related to the hurricanes and earthquakes. Following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, six federal laws allocated $24.8 billion to Puerto Rico.

Trends in Puerto Rico’s Housing Market

Some local officials and representatives from nongovernmental organizations we spoke to raised concerns that the resident investor incentive may be affecting Puerto Rico’s housing market. However, the effect of the incentive on the price of housing is unclear. According to data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency, while home prices have increased in Puerto Rico, they have risen less rapidly than in the United States as a whole over the past decade, as shown in figure 11.

Notes: The indexes presented here are the Federal Home Finance Agency purchase-only house price index for Puerto Rico and the United States. Puerto Rico housing price index data are published by the Federal Housing Finance Agency with the first quarter of 1995 equal to 100. Housing price index data for the United States are published with the first quarter of 1991 equal to 100. To present price growth of the United States and Puerto Rico together, we renormalized the United States data so that the first quarter of 1995 would be equal to 100 for both series. The house price index for Puerto Rico is considered “developmental” and accordingly has greater uncertainty.

Rents have also increased in Puerto Rico, but also by less than they have in the United States as a whole. According to data from the Census American Community Survey, median gross rent in Puerto Rico increased from $448 in 2012 to $557 in 2023, a 24 percent increase. Over that same period, median gross rent across the United States as a whole increased from $884 to $1,406, a 59 percent increase.

Recipients of tax incentives are participating in the housing market as both purchasers and renters. According to a 2024 report from DDEC, 37 percent of resident investor incentive recipients owned a home in Puerto Rico with an average value of over $5 million as of 2020, 30 percent rented, and 33 percent were unknown.

Municipal leaders we spoke to expressed differing views of the effects of tax incentives on housing in their localities. A local official from one municipality said that resident investor incentive recipients were not competing for the same properties as local residents because the recipients were purchasing more expensive homes than other local residents. However, officials from other municipalities cited concerns related to resident investor incentive recipients purchasing numerous properties for use as short-term rental units.

Local officials noted that residents of their municipalities face challenges finding affordable rental housing. However, the local officials were not sure if these challenges could be attributed to resident investor incentive recipients. Officials from two municipalities said it is difficult to find property owners willing to rent to recipients of low-income housing vouchers since short-term rentals are more profitable.[27] An official from one of these municipalities said that he thought short-term rentals were increasingly prevalent and that money sourced from them did not stay in the local area. Officials from another municipality said they had observed some incentive recipients buying many buildings at the same time. These officials said they believed this was in part responsible for unfavorable views of resident investor incentive recipients by local residents.

Evidence Is Mixed on Overall Costs and Benefits of the Tax Incentives and Economic Effects Are Difficult to Isolate

Given the influence of the factors described above, it is not clear if the economic development that has occurred since the Puerto Rico tax incentives were introduced would have occurred in the absence of the incentives. It is also not clear if these incentives are generating economic activity equal to the revenue the government forgoes to offer them or if economic activity would have decreased without the incentives in place.

The economic effects of the resident investor incentive are likely small on the scale of Puerto Rico’s economy overall. In 2023, there were fewer than 3,000 resident investor incentive recipients. This is less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the 3.2 million people who lived in Puerto Rico in 2023. This ratio makes any effects that this population may have on Puerto Rico’s overall economy difficult to measure apart from larger economic trends. Some economic studies funded by DDEC suggest an increase in economic activity and employment related to the tax incentives, with local perspectives and migration data suggesting more mixed results.

Evidence from Economic Studies

Hacienda projects that from 2020 through 2026, the Puerto Rico government will forgo $4.4 billion as a result of the resident investor incentive and $1.8 billion in revenue as a result of the export service business incentive.[28] For 2022, Hacienda estimated the forgone revenue for the resident investor and export service business incentives to be $637 million and $264 million respectively. These estimates represent the difference between the taxes that incentive recipients paid, compared to the taxes they would have paid if they did not receive the incentives, assuming reported income stayed the same. Hacienda’s measure of forgone revenue does not incorporate potential behavioral responses by taxpayers, such as whether the taxpayers would have moved to Puerto Rico had these incentives not been offered.

Economic studies done on behalf of the Puerto Rico government have attempted to quantify the economic effects of the resident investor and export service business tax incentives. A 2021 study contracted by DDEC found that economic activity in Puerto Rico was between 1 and 3 percentage points higher because of these economic incentives compared to what it would have been without them.[29] The study found that these effects were modest and that positive employment effects were primarily due to the export service business incentive. It also made recommendations, including modifying the resident investor incentive to increase the capital gains tax rate for new recipients. This recommendation has not been implemented.

A 2024 study also published by DDEC found that the incentives have positive revenue effects.[30] This study specifically attempted to identify the return on investment associated with the resident investor and export service business tax incentives, among other incentives. It estimated that in 2022, resident investor incentive recipients paid over $200 million in taxes and donations to Puerto Rico, while the incentives cost Puerto Rico $184 million.[31] Additionally, the study estimated that in 2022, resident investor incentive recipients had established more than 1,000 businesses. These recipients also held nearly 800 export services decrees that generated approximately $420 million in tax revenue compared to a cost of $356 million.[32] Additionally, the study estimated that export service businesses employed approximately 22,000 persons directly and led to employment for an estimated 52,000 persons indirectly.[33]

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the overall economic effects of these incentives, given variation in results from the economic studies due to a variety of factors including limitations in available data and differing assumptions and methodologies used. Each of the economic studies we reviewed focused on different inputs and outcomes and are not necessarily comparable. For example, the 2021 DDEC study generally tried to estimate the size of Puerto Rico’s overall economy with the incentives compared to where it may have been without the incentives. In contrast, the 2024 study generally measured benefits and costs in terms of Puerto Rico territorial and local government revenue.

Evidence from Local Perspectives

Local officials, researchers, economic development firms, and nongovernment organizations we spoke with in Puerto Rico were less certain about the effectiveness of the tax incentives at generating sufficient economic activity to offset their costs. Officials involved in economic development work said that few, if any, of the people receiving tax incentives would be in Puerto Rico without the incentives and emphasized the positive effects on Puerto Rico’s economy. Conversely, an economist thought Puerto Rico has relied too heavily on tax incentives to develop its economy, relative to other tools for growth.

One municipal official expressed mixed views on the effect of the incentives on local taxes. The official said that his area benefitted from an increase in certain municipal taxes, such as those charged on construction projects, as resident investor incentive recipients may purchase and remodel expensive homes. However, the same official noted that the structure of the export services business incentive limits the benefit to municipalities that could come from local property taxes. Consistent with this observation, the 2024 study published by DDEC estimates that forgone property taxes associated with this incentive are considerably higher than the benefits. An official in another locality agreed that the municipality had seen an increase in the number of construction permits in the area, which had benefited the locality.

While perspectives varied on the overall benefits of the incentives, most local officials we spoke to cited positive effects on employment, even those who thought the overall effects were not positive or worth the cost. For example, officials from one municipality noted that tax incentive recipients often established corporations as well as other businesses, such as restaurants, which generate employment. As noted above, the DDEC 2024 return on investment study estimated that more than 70,000 jobs were directly or indirectly attributable to the export service businesses incentives.

New resident investor incentive recipients are required to make an annual $10,000 charitable donation.[34] An official from one municipality expressed skepticism about the extent to which the charitable donations of resident investor incentive recipients are benefitting the local community. According to the DDEC study, in 2022, out of 2,660 individuals with active decrees, 765 individuals reported making at least one donation.[35] DDEC’s 2024 study reported that in 2022, resident investor incentive recipients made almost $11 million in required charitable donations. The study reported that the top recipients of donations made by resident investor incentive recipients are the Boys & Girls Club and the Act 20/22 Foundation, an organization that allocates money to different charities and provides guidance related to Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export services incentives. Officials from two municipalities pointed out that the donations do not need to be made to organizations located in the cities where the recipients live. One of these officials said he thought the requirements should be changed to ensure the donations are made to organizations that are local to the recipient of the resident investor incentive.

Evidence from Migration Data

Data on migration to Puerto Rico suggest that while the resident investor and export service business incentives may have motivated some people to move to Puerto Rico, other factors also contribute to relocation. The population of resident investor decree holders has grown in recent years, particularly in 2021. Additionally, the number of people filing Forms 8898—which taxpayers use to notify IRS that they either became or ceased to be a bona fide resident of a U.S. territory—has increased among both resident investor incentive recipients and nonrecipients, as seen in figure 12.

Note: Some taxpayers who did not receive the resident investor incentive in 2021 may have received the incentive in earlier years, and either stopped receiving the incentive or ceased to be residents of Puerto Rico.

This increase in individuals declaring bona fide residency in Puerto Rico without claiming resident investor incentives suggests that these tax incentives may not be the only factor driving migration to Puerto Rico, although the incentives may encourage some additional people who would not move to Puerto Rico otherwise to do so.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported that Puerto Rico’s population declined over the past decade, though the rate of decline slowed in 2024. In 2024, Puerto Rico’s population experienced a 0.02 percent decline over the prior year, in contrast to 1.3 percent and 0.5 percent declines in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Puerto Rico also experienced net positive migration in 2024. As shown in figure 13, Puerto Rico’s population declined 8.6 percent from 2015 through 2024.

IRS Did Not Effectively Leverage Data on Taxpayers Receiving Puerto Rico Tax Incentives

IRS Compliance Efforts Have Been Slow to Show Results

The IRS campaign was slow to demonstrate results, in part due to the complexity of high-income, high-wealth audits. In addition, IRS did not prioritize this effort and communication gaps between IRS and Hacienda left the campaign without key data on the taxpayer population for more than 4 years, as discussed in greater detail later in the report. We are not reporting results of IRS’s audits due to the sensitivity of the data, but the number of audits opened and closed in the initial years of the campaign was low until substantially increasing in the last year.

IRS officials told us up to 12 staff were assigned to the campaign, as of July 2025. These staff manage campaign operations, splitting their time across various projects and program areas. Revenue agents audit the individual returns designated as high risk and receive technical support from campaign staff as needed. According to IRS officials, audits of these taxpayers are resource intensive, taking an average of 2 years to complete and requiring highly trained revenue agents. Confirming residency and income source are particularly challenging.

· Residency. Where and when a taxpayer was residing for a given period is determined based on facts that are often difficult to obtain and confirm. For example, IRS may need to review detailed information such as credit card statements and travel records.

· Income source. The source of income may stem from multiple jurisdictions and can be difficult to verify, especially for taxpayers with numerous income streams that are individually complex.

Because of the level of complexity, officials said these audits are only suited for experienced revenue agents.

In the last year, IRS has taken some steps to make improvements in its compliance efforts. Specifically, the IRS campaign has increased the number of opened and closed audits, and campaign officials held their first formal coordination meeting with Hacienda in April 2025.

Going forward, the campaign will face staffing-related challenges. According to IRS officials, as of June 2025, IRS had lost 87 of the revenue agents conducting examinations in this area to the Deferred Resignation Program, retirement, promotion, or reassignment within the agency, an approximately 38 percent loss. Not all of these agents were auditing campaign-specific cases, but remaining agents had to absorb additional workload following their departures. This reduces IRS’s capacity to open new campaign audits. In addition, the campaign lost two of its subject matter experts. We have previously reported that IRS has skills gaps in mission critical occupations, including revenue agents.[36]

The campaign focuses only on civil noncompliance. Separately from the campaign, IRS Criminal Investigation special agents investigate individual taxpayers for criminal noncompliance, as well as professionals who were found to have promoted criminal noncompliance to clients. IRS Criminal Investigation refers any taxpayer data under review that are not indicative of criminal potential, but could have potential for civil noncompliance, to the campaign.

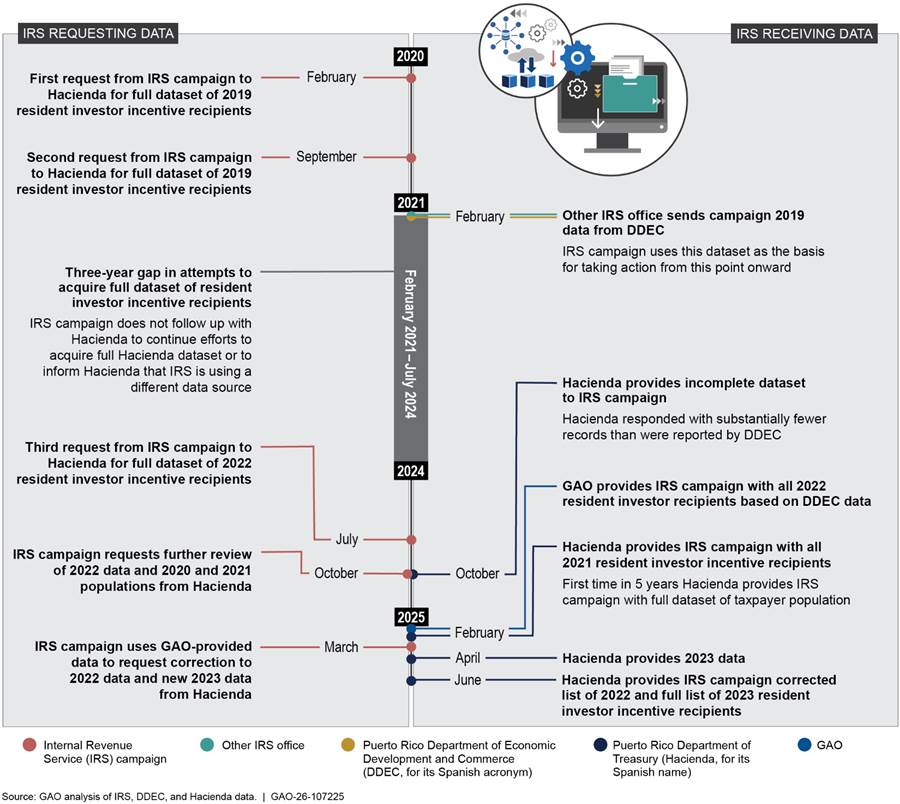

IRS Does Not Have Procedures to Address the Challenge of Acquiring Data from Hacienda

For the first 4 years of the campaign, IRS did not obtain a dataset of all taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive that was both current and contained Social Security numbers (SSN). Although IRS does not oversee the administration of Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive, the campaign focuses on the federal tax obligations of taxpayers receiving the resident investor incentive. Thus, these data are important for IRS to make fully informed enforcement decisions for this population.

DDEC maintains the list of taxpayers with active decrees, including a public list with names and the dates decrees were granted. However, this list does not include SSNs and not all decree holders claim the incentive on their Puerto Rico tax returns. Hacienda processes resident investor incentive recipients’ tax returns and has the most complete data on this taxpayer population.

IRS has requested data from Puerto Rico intermittently. The IRS campaign made two initial requests to Hacienda in 2020, but Hacienda did not respond to either IRS request. Hacienda officials told us that at that time, Puerto Rico was recovering from an earthquake that struck the commonwealth in January 2020 and significantly damaged the infrastructure. The earthquake and the ensuing COVID-19 pandemic contributed to this lack of response. IRS stopped following up with Hacienda in 2021, resulting in a 3-year gap in attempts to acquire data from Puerto Rico until 2024 when IRS made its third request, as shown in figure 14.

After receiving DDEC’s approval, we provided IRS a list of SSNs of taxpayers with active decrees as of 2022 that we obtained from DDEC in February 2025. This was the first new data covering all active decree holders that IRS had received in 4 years. IRS used this list as a source for additional data requests to Hacienda.

Subsequently, the IRS campaign received its first dataset from Hacienda that covered the full taxpayer population for tax year 2021. Additionally, IRS campaign officials reported holding their first formal meeting with Hacienda in April 2025 to discuss Puerto Rico data sharing efforts. However, the IRS campaign has no documented plans to routinely acquire the most current data from Hacienda going forward. IRS officials told us the campaign is an ongoing effort and that they have no plans to end the campaign. Thus, there will be a continuing need for current, actionable data.

IRS and Hacienda have a tax coordination agreement which states that Puerto Rico and the federal government are to routinely exchange tax information to assist in their respective tax administration responsibilities. Additionally, our prior work has identified several leading practices to enhance interagency collaboration, such as defining common outcomes and bridging organizational cultures.[37]

IRS officials told us the campaign decided to move forward without data from Hacienda in 2021 because the campaign received a 2019 dataset of decree-holders that was provided to the campaign by IRS Criminal Investigation staff, which officials thought was sufficient.

However, relying solely on 2019 data from 2021 to 2025 restricted IRS enforcement options due to the statute of limitations that limits IRS’s ability to assess taxes on older cases.[38] Further, IRS did not have data on new entrants to the taxpayer population during this period.

By not having current data on all recipients of the resident investor incentive, IRS did not have full visibility into the relevant taxpayer population, including new entrants. Establishing procedures to regularly obtain current data on all taxpayers who receive Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive would improve IRS’s efforts to ensure compliance. Additionally, these procedures could include processes that incorporate our leading collaboration practices (see fig. 15), helping IRS and Hacienda establish support for one another’s initiatives, reinforce mutual goals and expectations, and better equip officials in both agencies to effectively share current data on the full taxpayer population.

IRS Has Not Established Written Procedures to Evaluate Referrals from Puerto Rico

IRS does not have a process for evaluating referrals it received from DDEC of taxpayers whom Puerto Rico identified as not meeting its residency requirement. Specifically, in August 2023, DDEC shared audit reports with IRS that identified 179 taxpayers who did not provide evidence that they met Puerto Rico’s residency requirement. One campaign official reviewed a few cases before determining the referrals did not need to be prioritized.

Residency is a shared requirement between the Puerto Rico resident investor incentive and the federal income tax exemption. We analyzed the information from the DDEC audit reports against IRS data and identified a significant number of taxpayers with indicators of potential noncompliance with their federal tax obligations. About half of these taxpayers reported no taxable income to IRS in 2019, the most recent year in the audit period. Yet, all of the taxpayers we reviewed had between 1 and 7 years of noncompliance with Puerto Rico’s residency requirement from 2013 to 2019. While there are some differences in the Puerto Rico and federal residency requirements, taxpayers who do not meet Puerto Rico’s residency requirement are less likely to meet federal residency requirements. Taxpayers who do not meet federal residency requirements are not eligible for the federal tax exemption.

We have shared the results of our analysis with IRS for additional consideration. According to the Internal Revenue Manual, campaigns help IRS achieve its objective of identifying and assigning resources to address the highest potential compliance risks, and a main objective in selecting workload for campaigns is to select returns with the highest positive effect on tax administration.[39] However, IRS did not take action on DDEC’s referral of taxpayers who did not provide evidence that they met Puerto Rico’s residency requirement. Additionally, IRS does not have written processes in place for how it will address any future referrals from government agencies in Puerto Rico.

IRS officials said they did not pursue these DDEC referrals because they would have rather invested their resources in leveraging data from Hacienda, which has more relevant data than DDEC. However, when IRS received the referrals in August 2023, Hacienda had not provided IRS any taxpayer data, and IRS did not request data from Hacienda again until July 2024. According to IRS officials, IRS determines resource allocations among different campaigns based on their priority ranks, and IRS officials said they do not believe written guidance on external referral prioritization is necessary given the campaign’s high-priority rank. However, the campaign does not have written policies or criteria to identify external referrals that have high potential for audit in comparison to internal leads within the campaign, and IRS did not leverage previous referrals from the Puerto Rico government within the campaign.

Developing written procedures to review cases of potential noncompliance among resident investor incentive recipients referred to IRS by Puerto Rico government agencies could help IRS strategically allocate its resources toward high audit potential cases and help improve compliance. It would also help ensure referrals are treated consistently.

IRS’s Campaign Has Not Pursued Efforts to Promote Voluntary Compliance

The objective of the IRS campaign is to address noncompliance through a variety of treatment streams beyond examinations, including educational outreach. Additionally, the Taxpayer Bill of Rights states that taxpayers have the right to clear explanations of the laws and IRS procedures in all correspondence.[40]

As of November 2025, IRS’s campaign had not taken additional action to educate taxpayers whom IRS had identified as receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive, such as sending an educational letter to those taxpayers. According to IRS officials, they began drafting an educational letter in November 2024 tailored to taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive as a result of our audit. As of November 2025, IRS finalized the text of the letter and used data we provided during the course of this audit to identify the letter recipients. However, there are additional steps IRS plans to take before sending the letter, including its ongoing effort to refine the taxpayer data necessary to process the letters.

IRS officials said that they had not sent educational letters in the past because it can be difficult to determine whether an individual is currently claiming the resident investor incentive. Sending a letter to taxpayers for whom the information would not be relevant could create confusion among the taxpayers and could lead taxpayers to call IRS for clarification. However, in 2025, IRS obtained more current data on taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive which can inform its educational outreach. IRS officials confirmed that there are generally few drawbacks to sending such letters.

IRS has an opportunity to provide clear explanations of complex compliance requirements and increase voluntary compliance among taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive by sending educational letters to this taxpayer population. Educational letters are a cost-effective tool, and IRS is also able to track the efficacy of these efforts by identifying taxpayers who filed amended returns after receiving an educational letter.

Conclusions

Since 2012, thousands of individuals have moved from the mainland United States to Puerto Rico and received tax incentives from the territory that are intended to bring new businesses and residents to the commonwealth, and along with them, economic growth. Individuals who receive Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive could also, separately, be largely exempt from federal income taxes depending on the source of their income. Specifically, we found that in aggregate, the decrease in federal tax revenue from taxpayers receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

IRS has missed opportunities to leverage data from Puerto Rico on taxpayers receiving resident investor incentives. From the start of the campaign until early 2025, IRS’s compliance initiative was generally not basing its audit decisions on the most current data that included the full population of taxpayers receiving the Puerto Rico tax incentives. Communication gaps between IRS and Hacienda delayed IRS’s acquisition of these data for years. Establishing procedures to regularly obtain current data on all relevant taxpayers from Hacienda would strengthen IRS compliance efforts. Moreover, the inclusion of leading collaboration practices into such procedures could help IRS and Hacienda establish support for one another’s initiatives.

Further, with the information it did have, IRS did not pursue cases with indicators of potential noncompliance that the government of Puerto Rico identified and sent to IRS. Specifically, DDEC identified 179 taxpayers who did not provide evidence that they resided in Puerto Rico for the required 183 days per year—one of the ways taxpayers can meet federal residency requirements to qualify for federal income tax exemption from income sourced from Puerto Rico. IRS only reviewed a small number of these cases before determining the information did not need to be prioritized. However, we reviewed these files and identified a significant number of taxpayers with indicators of potential noncompliance, which we have shared with IRS. IRS could improve compliance and ensure referrals are treated consistently by establishing written procedures to review cases of potential noncompliance among resident investor incentive recipients referred to IRS by Puerto Rico government agencies.

In light of the complex enforcement and resource challenges IRS faces, IRS should also consider avenues to promote voluntary compliance. Educational efforts, such as sending taxpayers educational letters that explain compliance requirements related to an aspect of their probable tax situation, can be a cost-effective way to promote voluntary compliance. In November 2025, IRS reported it is in the later stages of sending an educational letter tailored to this taxpayer population as a result of our audit.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to IRS:

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue should establish procedures to regularly obtain from Hacienda current data on all recipients of the Puerto Rico resident investor incentive. These procedures could incorporate GAO’s leading collaboration practices. (Recommendation 1)

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue should establish written procedures to review cases of potential noncompliance among recipients of the resident investor incentive that Puerto Rico government agencies identify and send to IRS. (Recommendation 2)

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue should take action to promote voluntary compliance, such as sending educational letters explaining key compliance requirements to taxpayers who are benefiting from Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Internal Revenue Service and the Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico for review and comment. IRS and the Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico provided written comments that are reprinted in appendixes II and III. IRS and the Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. IRS concurred with all three of our recommendations and stated that it will take steps to address our recommendations by institutionalizing procedures specific to this campaign and completing final review of an educational letter.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Internal Revenue Service, the Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at mctiguej@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

James R. McTigue, Jr.

Director, Strategic Issues

Tax Policy and Administration

This report (1) describes the population of individuals and businesses receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export service business tax incentives; (2) describes selected economic effects of Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export service business tax incentives on Puerto Rico’s economy based on available data; and (3) assesses the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) efforts to ensure compliance among U.S. persons relocating to Puerto Rico and claiming bona fide residency.

Population of Resident Investor and Export Service Incentive Recipients

To describe the number of resident investor and export service decrees granted by year, we analyzed data from the Puerto Rico Department of Economic Development and Commerce (known by its acronym in Spanish, DDEC). These data list each decree holder and the date the decree was granted. We analyzed data from 2012, when the incentives were first introduced, through 2024.

Not all individuals who were granted a decree from DDEC ever relocated to Puerto Rico or used their decree to receive tax incentives. To ensure our analysis described resident investor incentive recipients, we focused on the 2,201 individuals who received the incentive on their 2021 tax returns submitted to the Puerto Rico Department of Treasury (known by its name in Spanish, Hacienda. [41]

We also received summary data on individual investor incentive recipients from 2022 and 2023. Collectively, tax returns filed from 2021 to 2023 included returns filed by 3,165 of the 5,852 (54 percent) of individuals granted individual investor decrees from 2012 to 2024.[42] We were not able to determine if any of the remaining individuals ever relocated to Puerto Rico or used their decrees.

To analyze income characteristics before and after individuals relocated to Puerto Rico, we matched the 2,201 individuals from 2021 Hacienda data to federal tax return information from IRS.

Because these individuals relocated to Puerto Rico in different years, we took data for each individual from 5 years before they relocated to Puerto Rico, as well as data from up to 5 years after they relocated to Puerto Rico. Some taxpayers did not file 1040s in all 5 of the prior years, and IRS data were only available through 2023. If there were fewer than 5 years of data available before or after an individual relocated, we used as many years as were available. We adjusted all dollar values for inflation prior to averaging to account for the fact that they occurred at different points in time.

To identify the states from which resident investor incentive recipients moved, we analyzed IRS Form 1040 data, identifying the most recent U.S. state the individual listed on their income tax return prior to the year in which the person relocated to Puerto Rico.

Individuals meeting certain requirements are required to file Form 8898 with IRS when they establish bona fide residency in Puerto Rico. We matched individuals receiving resident investor tax benefits in 2021 to IRS data on individuals who filed Form 8898. As part of this analysis, we interviewed officials from IRS, DDEC, and Hacienda, and conducted standard data reliability assessments. We found that the available data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

Economic Effects on Puerto Rico’s Economy

To capture macroeconomic events that have significantly affected Puerto Rico’s economy throughout the last decade, we reviewed our prior reports on disaster relief to Puerto Rico following Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, a series of earthquakes in 2019 and 2020, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic.[43] We also reviewed reports on Puerto Rico’s debt crisis and its efforts to recover from it.[44]

To describe selected economic effects of Puerto Rico’s resident investor and export service business tax incentives on Puerto Rico’s economy, we reviewed publicly available data from a variety of governmental sources in Puerto Rico and in the federal government. To understand recent trends in Puerto Rico’s economy, we reviewed data from the Puerto Rico Planning Board on the commonwealth’s gross national product and economic growth and the Economic Activity Index, a measure developed by the Economic Development Bank of Puerto Rico. We also used data on housing prices from the Federal Housing Administration and rental prices from Census’s American Community Survey to describe the housing market in Puerto Rico.

To consider how the tax incentives specifically have affected the economy in Puerto Rico, independent of other events, we reviewed available studies that have attempted to determine the effects of the tax incentives on the commonwealth’s economy. We reviewed a report from Hacienda quantifying tax expenditures offered by the government. We also reviewed studies contracted by DDEC that attempted to isolate the effect of the incentives from other factors and that attempted to identify the return on investment associated with the incentives by quantifying benefits as well as costs.

We supplemented our review of available data and research by conducting site visits in Puerto Rico and interviewing government officials, researchers, economic development firms, and stakeholder groups, selected based on their knowledge of the tax incentives.

We also selected the municipalities of Aguadilla, Dorado, Rincón, and San Juan for additional focus because local stakeholders and government officials noted that large numbers of resident investor incentive recipients lived in these localities. We met with local officials from these municipalities to better understand local perceptions of the incentives and their effects. These municipalities were selected judgmentally and are not necessarily representative of all communities in Puerto Rico. We used conversations with local officials from these municipalities as well as other organizations to determine how the tax incentives are perceived at the local level.

Finally, we used IRS data on the number of Form 8898 filers and Hacienda data on individuals who used their decrees to receive tax incentives to understand how many individuals who moved to Puerto Rico received and used decrees. We supplemented this with information from the Census Bureau and the Puerto Rico Planning Board about overall trends in migration to and from Puerto Rico.

IRS Oversight

To assess IRS efforts to ensure compliance among U.S. persons relocating to Puerto Rico and claiming bona fide residency, we reviewed IRS documents and spoke with agency officials about IRS’s efforts to ensure individuals receiving Puerto Rico’s resident investor incentive met federal residency and income sourcing requirements. We met regularly with IRS officials responsible for IRS’s compliance campaign focusing on taxpayers receiving tax benefits in Puerto Rico to discuss their oversight efforts. We also met with Puerto Rico government officials responsible for Puerto Rico tax administration, decree oversight, and communication with IRS. We also reviewed email correspondence and meeting minutes related to IRS’s work in this area, including communications between IRS and the government of Puerto Rico related to the exchange of tax data between the agencies. We also reviewed data on audit outcomes, including the number of cases opened and closed by the campaign and total dollars assessed from these cases. We compared IRS’s actions in this area to the existing tax coordination agreement between the federal government and Puerto Rico, our prior work on leading practices for enhancing interagency collaboration, applicable sections of the Internal Revenue Manual, IRS campaign objectives, and the Taxpayer Bill of Rights.[45]

We also reviewed data on instances of noncompliance identified by the government of Puerto Rico. IRS provided us with information on 179 individuals who did not provide evidence that they met Puerto Rico’s residency requirement. We used the identifying information to locate each individual’s Form 1040 and Form 8898 filings, when available. We have shared the results of our analysis with IRS, based on our analysis of indicators of potential noncompliance.

To determine additional actions IRS might take to ensure compliance, we met with campaign officials to discuss requirements and challenges associated with taxpayer education. We also reviewed minutes from IRS coordination meetings during which this topic was discussed. We compared IRS’s efforts to educate taxpayers to the written objective of the campaign and relevant section of the Taxpayer Bill of Rights.

For each of our objectives, we reviewed our relevant prior reports. In all cases, we found the data presented in this report sufficiently reliable for its purpose.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

James R. McTigue, Jr., McTigueJ@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Tara Carter (Assistant Director), Melissa King (Analyst in Charge), Pedro Almoguera, Virginia Chanley, Jacqueline Chapin, Zachary Conti, Daniel Mahoney, Meredith Moles, Andrew J. Stephens, Alicia White, and Sarah Steele Wilson made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Act to Promote the Export of Services, 2012 P.R. Laws Act 20; Act to Promote the Relocation of Individual Investors to Puerto Rico, 2012 P.R. Laws Act 22. Commonly referred to as Act 20 and Act 22 respectively, these provisions are generally codified, as amended, at P.R. Laws Ann. tit. 13, §§ 1301–1357.

[2]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023); and Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Manual, § 4.50.1.2.2(5) (July 1, 2022), and The Taxpayer Bill of Rights, Publication 1 (September 2017).

[3]For additional information, see GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt and Economic Outlook – 2025 Update, GAO‑25‑107560 (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2025).

[4]Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, Annual Report 2024 (San Juan, PR: Jan. 22, 2025).

[5]The Tax Reform Act of 1976 established the possessions tax credit under section 936 of the Internal Revenue Code with the purpose of assisting U.S. possessions in obtaining employment-producing investments by U.S. corporations. The credit effectively exempted two kinds of income from U.S. taxation: (1) income from the active conduct of a trade or business in a possession, or from the sale or exchange of substantially all of the assets used by the corporation in the active conduct of such trade or business; and (2) certain income earned from financial investments in U.S. possessions or certain foreign countries, if they were generated from an active business in a possession, and were reinvested in the same possession. See GAO, Puerto Rico: Factors Contributing to the Debt Crisis and Potential Federal Actions to Address Them, GAO‑18‑387 (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2018).

[6]2019 P.R. Laws Act 60.

[7]The law limits eligibility to individuals who were not residents of Puerto Rico during a prior specified period.

[8]Qualifying net capital gains must be realized before January 1, 2036, in order to receive the resident investor preferential tax rates.

[9]According to Hacienda, Puerto Rico residency is based on the domicile of the individual, which is established through physical presence, together with the intention to remain in a place indefinitely. An individual is presumed to be a domiciled resident of Puerto Rico if the individual has been present in Puerto Rico for 183 days during the year, although this presumption can be rebutted by the actions and personal circumstances of the taxpayer. Under Puerto Rico law, an individual can have only one domicile. P.R. Laws Ann. tit. 31§ 5551.

[10]These payments must be made every year to nonprofit entities that operate in Puerto Rico, are certified under the Puerto Rico Internal Revenue Code, and are not controlled by the resident investor or their immediate family members. Evidence of these payments must be included as part of the annual report incentive recipients file with the government of Puerto Rico. Half of the donation must be to certain organizations that work to eradicate child poverty. 13 P.R. Laws § 45830(b).

[11]The export service business incentive does not have a residency requirement for the owner(s) of the business.

[12]26 U.S.C. § 933.

[13]26 U.S.C. § 937(a). For federal tax law purposes, the determination as to whether a person is present for any day is made under the principles of 26 U.S.C. § 7701(b) and 26 C.F.R. § 1.937-1(c)(3).

[14]An individual’s tax home is their regular or main place of business, employment, or post of duty regardless of where they maintain their family home. If the taxpayer does not have a regular or main place of business because of the nature of their work, then their tax home is where they regularly live. If a taxpayer does not fit either of these categories, they are considered an itinerant and their tax home is wherever they work.