FEDERAL PRISONS

Improvements Needed to the System Used to Assess and Mitigate Incarcerated People’s Recidivism Risk

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Gretta Goodwin at goodwing@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) required the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to assess incarcerated people’s risk of recidivism and their needs, that if addressed, may reduce that risk. BOP did not conduct all assessments within required time frames (28 days for initial and 90 or 180 days for reassessments) for various reasons, including technology issues. For example, BOP conducted initial risk assessments within required time frames for about 75 percent of the 57,902 incarcerated people who entered a BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024. For the needs it is responsible for assessing, BOP conducted 69 to 95 percent of this cohort’s assessments within required time frames. BOP plans to enhance an existing application to ensure assessments are conducted as required, in response to a 2023 GAO recommendation.

BOP officials said they offer FSA programs and activities that address all 13 needs (e.g., substance use). However, BOP does not have accurate program data because, for example, staff used different methods to record when an incarcerated person declined to participate in a recommended program. GAO also found inaccuracies in program participation data, which BOP officials attributed to data entry errors. Without accurate data, BOP cannot determine if it offers sufficient programming to meet the needs of its incarcerated population.

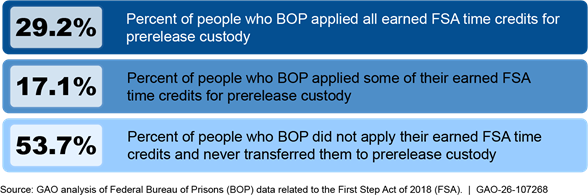

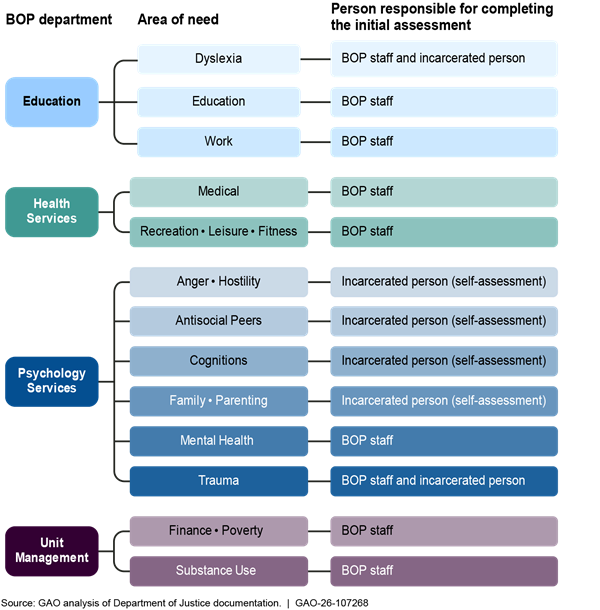

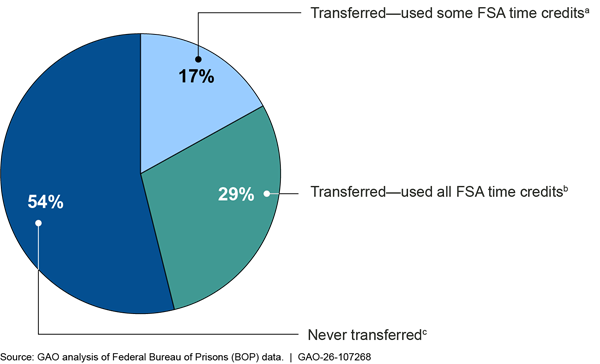

Eligible incarcerated people who agree to participate in programs, among other things, may earn time credits toward early transfer to supervised release and prerelease custody (i.e., home confinement or residential reentry center). GAO found that BOP generally applied all time credits toward supervised release but not for prerelease custody. BOP implemented new planning tools in 2024 and 2025 to help staff anticipate upcoming transfers to prerelease custody and ensure incarcerated people receive their FSA time credits. GAO has ongoing work examining BOP’s efforts to forecast capacity needs and provide sufficient residential reentry center resources.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has not been able to fully address all FSA annual reporting requirements because not enough time has passed since the agency implemented FSA to determine certain things, such as recidivism rates. This requirement expired in 2025, and absent congressional actions, DOJ no longer has to submit a report to Congress. Without such information, Congress may be hindered in its decision making regarding the FSA.

Why GAO Did This Study

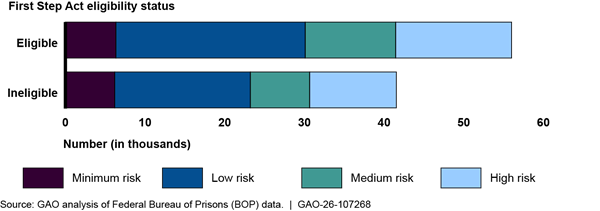

In 2024, BOP released approximately 42,000 people from federal prisons. Approximately 45 percent of people released from federal prison recidivate (are re-arrested or return within 3 years of their release), according to BOP. Under the FSA, BOP is to help reduce recidivism by assessing a person’s recidivism risk and needs and providing programs and activities to address their needs. The FSA allows eligible people to earn time credits that may reduce their time in prison.

The FSA includes a provision for GAO to assess certain FSA requirements. This report examines the extent to which BOP conducted risk and needs assessments; offered programs and activities; and applied FSA time credits. This report also examines the extent to which DOJ met FSA reporting requirements, among other objectives.

GAO analyzed BOP data from January 2022 through December 2024 for people in BOP custody as of March 30, 2024. GAO analyzed DOJ and BOP policies, guidance, and reports and interviewed officials at BOP’s Central Office and three regional offices. GAO also interviewed staff and incarcerated persons at four facilities. GAO selected facilities based on factors such as geographic location and security level.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider extending the reporting requirement for DOJ’s annual FSA report. Additionally, GAO is making six recommendations to BOP, including several recommendations to improve its data collection. BOP concurred with all six recommendations and plans to take action to address them.

Abbreviations

BOP Federal Bureau of Prisons

DOJ Department of Justice

FSA First Step Act of 2018

PATTERN Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and

Needs

SPARC-13 Standardized Prisoner Assessment for Reduction in

Criminality

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 27, 2026

Congressional Committees

In 2024, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) released approximately 42,000 people after they had served their federal prison sentence.[1] Central to BOP’s agency mission is to prepare incarcerated people to successfully reenter communities upon release. However, approximately 45 percent of people released from federal prison are re-arrested or return to a federal prison within 3 years of their release, according to BOP.[2] On December 21, 2018, the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) was enacted and includes certain requirements for DOJ and BOP to help reduce recidivism among individuals incarcerated in federal prisons.[3]

As required by the FSA, BOP is to assess an incarcerated person’s risk of recidivism and identify their “criminogenic needs,” which are characteristics of a person that directly relate to their likelihood to commit another crime. BOP is to use these assessments to place incarcerated people in programs and activities that may help address their needs and reduce their risk of recidivism. Further, eligible incarcerated people may earn FSA time credits related to these programs and activities that may reduce the amount of time they spend in a federal prison.[4] The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, designated not less than approximately $409 million of BOP’s annual appropriation for the programs and activities authorized by the FSA.[5]

We have previously reported on DOJ and BOP’s implementation of the FSA, the challenges that formerly incarcerated people face upon reentering society after incarceration, and the federal grant programs designed to help reduce recidivism.[6] Due to longstanding staffing and infrastructure challenges, leadership changes, and other challenges, we added Strengthening Management of the Federal Prison System to our high-risk list in 2023.[7] The Related GAO Products section at the end of this report lists our prior work.

The FSA includes a provision for us to assess on an ongoing basis the extent to which DOJ and BOP have implemented certain FSA requirements. This report addresses the extent to which: (1) BOP conducted and monitored risk and needs assessments, and DOJ validated the risk and needs assessment tools; (2) DOJ and BOP evaluated and offered programs, activities, and work assignments; (3) BOP applied FSA time credits for eligible incarcerated people; (4) BOP ensured the FSA is consistently implemented bureau-wide; and (5) DOJ met reporting requirements.

To address all five of our objectives, we analyzed relevant legislation and regulations, including the FSA, and relevant DOJ and BOP documents. Documents included BOP policies and guidance, contracts, and agency reports. We also obtained perspectives from DOJ and BOP headquarters officials, through interviews and written responses, regarding their FSA-related efforts. In addition, we interviewed BOP union officials to obtain their perspectives on the FSA. As relevant, we assessed BOP’s processes and practices against criteria, including the FSA,[8] BOP policies, and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[9]

For objectives one through four, we conducted case studies of four BOP facilities to obtain perspectives from regional and facility-level officials and incarcerated people about their experiences with the FSA.[10] We selected these facilities based on a variety of conditions, such as selecting a range of security levels and different geographic locations.

For objectives one through three, we analyzed BOP data. We obtained and analyzed individual-level BOP data from the SENTRY system on people who have been sentenced and were in BOP custody to conduct analyses related to risk and needs assessments, programs and activities, and FSA time credits, among other things.[11] We assessed the reliability of the data by conducting electronic tests; reviewing BOP documentation; and interviewing BOP staff knowledgeable about the data. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of determining timeliness of risk and needs assessments, program completions, and application of FSA time credits, among other things. See appendix I for additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Elements of the FSA

Elements associated with the FSA include the risk and needs assessment system, evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities, and FSA time credits, as shown below in figure 1.

Note: An evidence-based recidivism reduction program is either a group or individual activity that has been shown by empirical evidence to reduce recidivism or is based on research indicating that it is likely to be effective in reducing recidivism; and is designed to help people succeed in their communities upon release from prison. A productive activity is either a group or individual activity that is designed to allow incarcerated people determined as having a minimum or low risk of recidivating to remain productive and thereby maintain a minimum or low risk of recidivating.

Risk and Needs Assessment System

Under the FSA, BOP is to assess both the recidivism risk and the needs of incarcerated people. Specifically, BOP is to complete these assessments when an incarcerated person first arrives at a BOP facility and reassess them at least annually if the incarcerated person is successfully participating in programs or activities.[12] BOP is to conduct these assessments using two tools: the Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs (PATTERN) and the Standardized Prisoner Assessment for Reduction in Criminality (SPARC-13).

PATTERN. PATTERN is DOJ’s risk assessment tool that BOP staff are to use to measure an incarcerated person’s risk of recidivism. The National Institute of Justice developed PATTERN for DOJ in 2019.[13] Since then, DOJ has updated and issued three iterations of the tool. DOJ implemented PATTERN 1.3—the most recent version—in May 2022. BOP uses PATTERN to predict general or violent recidivism:

· General recidivism is any arrest or return to BOP custody following release.[14]

· Violent recidivism is an arrest for an act of violence following release.[15]

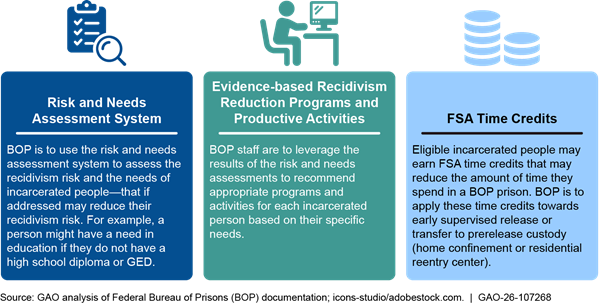

PATTERN assesses a person’s risk of recidivism based on factors an incarcerated person can change over time (dynamic factors) and those that cannot change (static factors). It has four static factors and 11 dynamic factors, as described in figure 2.

Figure 2: DOJ’s Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs (Version 1.3) and Its Static and Dynamic Factors

Note: Static factors are characteristics of incarcerated people that are historical and therefore unchangeable, such as an incarcerated person’s age at the time of assessment. By contrast, dynamic factors are variables that may change over time and may reflect more recent incarcerated person behavior, such as prison misconduct or completion of recidivism reduction programs while incarcerated.

aPresentence Investigation Report is a structured report required pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3552 to be conducted by a U.S. Probation Officer prior to a defendant’s sentencing. A Presentence Investigation Report contains information from various sources, including criminal history records, educational systems, hospitals and counseling centers, family members, and associates.

bThe Walsh criteria refers to whether the person is a sex offender as defined in the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act, Title I of the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-248, 120 Stat. 587.

cBOP staff may issue an incident report to an incarcerated person when the official witnesses or reasonably believes the person committed a prohibited act as described in BOP regulations and policy. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Discipline Program, 5270.09 CN-1 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 18, 2020).

dAccording to BOP, a 100-level incident is an incident of greatest severity, such as killing another person or rioting. A 200-level incident is an incident of high severity, such as fighting another person or stealing/theft. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Discipline Program, 5270.09 CN-1 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 18, 2020).

ePrograms completed does not include all the evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities currently available throughout BOP. Additionally, some of the programs currently included in this variable, such as Adult Continuing Education, are not considered evidence-based recidivism reduction programs or productive activities by BOP policy.

PATTERN classifies an incarcerated person’s risk of recidivism into four levels—minimum, low, medium, or high—based on their numerical risk score and applicable “cut points.”[16] A person’s risk score and level may increase or decrease during their incarceration based on some of these factors. For example, as a person ages, their risk score may lower.[17] PATTERN includes different predictive models and scales based on whether an incarcerated person is female or male because risk factors vary among females and males.[18] It uses different cut points for females and males to account for differences in their risks.

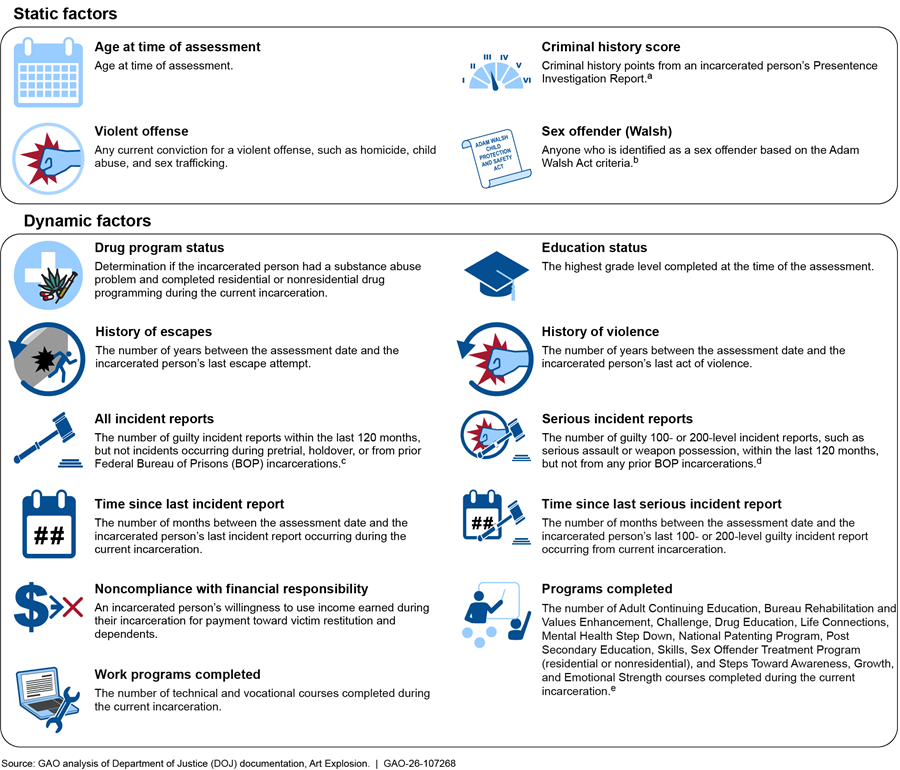

SPARC-13. SPARC-13 is BOP’s needs assessment tool that staff are to use to identify incarcerated people’s needs that, if addressed, may reduce their recidivism risk.[19] As shown in figure 3, BOP is to assess people’s needs in 13 areas. Different BOP departments are responsible for initially assessing specific areas of need. Other areas of need require the voluntary participation of the incarcerated person by completing a self-assessment, and other areas require participation from both BOP staff and the incarcerated person.

Figure 3: Needs Assessed by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), by Department and Person Responsible for the Initial Assessment

While initial assessments are conducted by BOP staff or an incarcerated person, BOP uses an automated electronic tool for reassessments. Specifically, this tool reassesses needs from information in SENTRY. This information, which is to be updated as appropriate by BOP staff, can include a person’s refusal to take an assessment or a new incident report. For both risk and needs assessments, staff press a button, and the tool pulls the data from SENTRY to create the reassessment result. BOP implemented this tool in August 2021. Prior to this tool, staff at BOP facilities manually calculated risk scores for each reassessment, as we reported in 2023.[20]

Evidence-Based Recidivism Reduction Programs and Productive Activities

BOP is to offer evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities (programs and activities) to people incarcerated within BOP facilities to help them address their individual needs identified through the SPARC-13 assessments.[21]

· The FSA defines an evidence-based recidivism reduction program as either a group or individual activity that has been shown by empirical evidence to reduce recidivism or is based on research indicating that it is likely to be effective in reducing recidivism, and is designed to help people succeed in their communities upon release from prison.[22]

· A productive activity is either a group or individual activity that is designed to allow incarcerated people determined as having a minimum or low risk of recidivating to remain productive and thereby maintain a minimum or low risk of recidivating.[23]

Each evidence-based recidivism reduction program and productive activity is to address one or more of the 13 areas of need. Some programs and activities address several needs. For example, the anger management program can help address two needs—the anger/hostility need and the cognitions need. Appendix II lists BOP’s programs and productive activities and the needs they address.[24] According to its August 2025 Approved Program Guide, BOP has 48 evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and 73 productive activities.[25] The number of programs and activities have changed over time, and BOP has criteria to review external entities’ proposals—such as from researchers and faith-based organizations—to create new evidence-based recidivism reduction programs that could be offered at BOP facilities.[26] Some of these programs and activities (10 programs and one activity) will result in an incarcerated person’s recidivism risk score lowering if they complete the program or activity. If a person’s risk score lowers, then their risk level may also lower.[27]

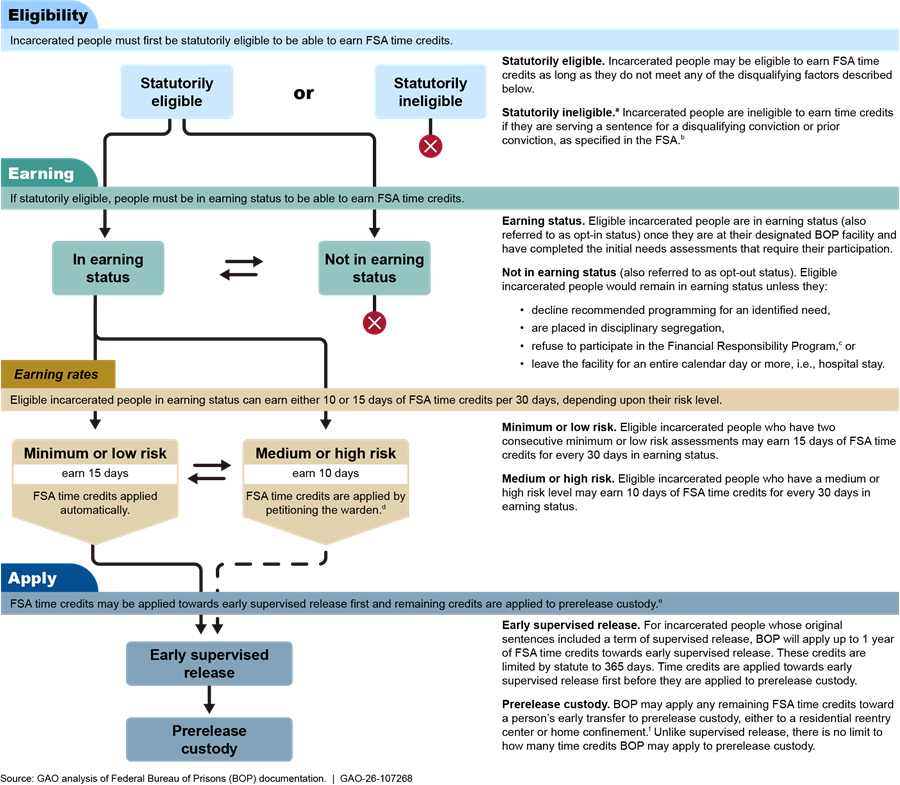

FSA Time Credits

Based on BOP’s implementation of the FSA, eligible incarcerated people earn FSA time credits based on their earning status. To be in earning status, eligible incarcerated people must have arrived at their designated BOP facility and completed the needs assessments that require their participation, as shown in figure 4. They remain in earning status unless certain events occur, such as a person declining to participate in recommended programming.

Note: FSA time credits are not earned based on program participation or completion. As such, a person does not need to participate or complete programs or activities to remain in earning status.

aIncarcerated people who are ineligible to earn or apply FSA time credits may still earn other rewards and incentives for successfully participating in evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities. For example, these people may earn increased phone and video conferencing privileges and additional time for visitation at the prison, as determined by the warden and per the BOP policy guiding the issuance of FSA incentives.

b18 U.S.C. § 3632(d)(4)(D). These disqualifying offenses generally involve violent or gang-related offenses, sex offenses, certain national security or immigration-related offenses, and some drug-trafficking offenses.

cThe Financial Responsibility Program helps people develop a financial plan to complete obligatory payments, such as court-ordered restitutions, fines, and court costs.

dFor a person with a medium or high recidivism risk level to have their time credits applied, they must petition the warden. 18 U.S.C. § 3624(g)(1)(D)(II). And if approved, these time credits would be applied. An incarcerated person who has a final order of removal is ineligible to apply earned FSA time credits. 18 U.S.C. § 3632(d)(4)(E).

eUnder the FSA, to have their time credits applied, eligible incarcerated people generally must have accrued time credits in an amount that is equal to the remainder of the person’s imposed term of imprisonment. 18 U.S.C. § 3624(g)(1)(A)-(D)(i)(I). An incarcerated person who has a final order of removal is ineligible to apply earned FSA time credits. 18 U.S.C. § 3632(d)(4)(E).

fIn making its decision toward prelease custody, in addition to FSA time credits, BOP may also need to consider the Second Chance Act. Specifically, the Act permits incarcerated people to spend a portion of the final 12 months of their sentence in prerelease custody. Additionally, BOP facility staff are to individually assess incarcerated people for the appropriateness of prerelease custody, based on criteria set forth in 18 U.S.C. § 3621(b), and recommend how long the person should be placed at a residential reentry center or home confinement. All incarcerated people are statutorily eligible for prerelease custody under the Act. However, the length of a person’s prerelease custody is also determined by other factors, such as bed space and resource availability of the residential reentry center.

The amount of FSA time credits that incarcerated people earn is not based on how many, if any, programs or activities they participate in or complete. The FSA states that eligible incarcerated people who successfully complete evidence-based recidivism reduction programming or productive activities are to earn 10 days of FSA time credits for every 30 days of successful participation in programs or activities.[28] However, as we reported in 2023, under BOP’s implementation of the FSA, incarcerated people earn time credits based on their earning status—not the number of programs they participate in or complete.[29]

We also reported that BOP officials noted that they designed their earning status criteria to account for items in the FSA Time Credits regulations.[30] For example, under BOP’s procedure, and consistent with the FSA Time Credits regulations, facility interruptions and program unavailability do not affect an incarcerated person’s ability to be in earning status.[31] Thus, a person can earn time credits even when programming is not available or without ever participating in a program.

Ultimately, FSA time credits may reduce the amount of time an incarcerated person spends in a BOP facility. Eligible incarcerated people can earn FSA time credits toward early supervised release and transfer to prerelease custody (i.e., residential reentry centers or home confinement).[32] In making its decision toward prelease custody, in addition to FSA time credits, BOP may also need to consider the Second Chance Act. By law, the Director of BOP is required, to the extent practicable, to ensure incarcerated people serving a term of imprisonment are able to spend a portion of the final 12 months of their sentence under conditions that will afford them a reasonable opportunity to adjust and prepare for reentry into the community.[33]

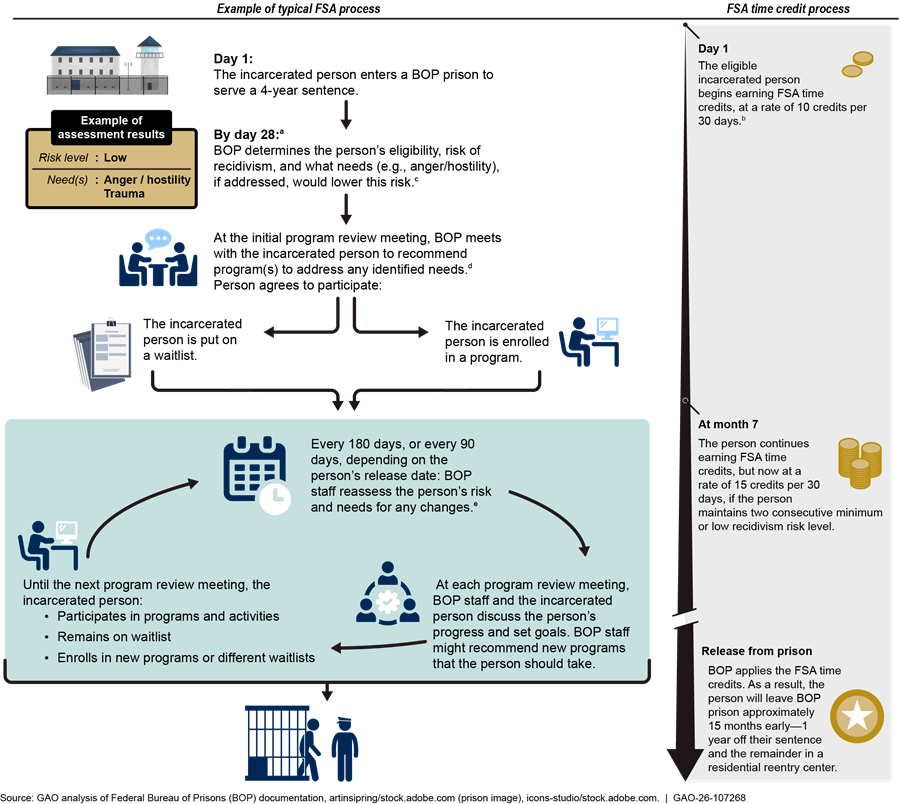

Figure 5 shows an example of how an incarcerated person entering a BOP facility could have FSA time credits applied.

Figure 5: Example of the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) Time Credits Process for an Eligible Incarcerated Person at a BOP Facility

Note: This figure is an example of how an eligible incarcerated person in earning status may earn FSA time credits. Incarcerated people may be eligible to earn FSA time credits as long as they are not serving a sentence for a disqualifying conviction or prior conviction, as specified in the FSA. Eligible incarcerated people are in earning status once they are at their designated BOP facility and have completed the initial needs assessments that require their participation. This figure does not address other rewards or incentives for which an incarcerated person may be eligible.

aBOP policy states that staff are to complete risk assessment by day 28 and some of the needs assessments by day 30. However, according to BOP officials, they ask staff to complete all assessments by day 28.

bAccording to BOP, all eligible incarcerated individuals are to begin earning time credits from day 1, once they arrive at their designated BOP facility. While eligibility and earning status may not be known on day 1, according to BOP officials once this is determined, FSA time credits would be retroactively earned since day 1 of their arrival. An incarcerated person remains in earning status unless the individual declines recommended programming for an identified need, is placed in disciplinary segregation, refuses to participate in the Financial Responsibility Program, or leaves the designated facility for an entire calendar day or more.

cBOP defines risk of recidivism as the likelihood that a person may continue to engage in unlawful behavior once released from prison. DOJ defines recidivism as (a) a new arrest in the U.S. by federal, state, or local authorities within 3 years of release or (b) a return to federal prison within 3 years of release. BOP staff are to conduct a review of the person’s current and prior conviction(s) to determine their eligibility to earn FSA time credits.

dBOP staff are to hold two types of regularly schedule meetings with incarcerated individuals: initial classification and program reviews, per BOP policy. The purpose of the initial classification is to develop a program plan for the incarcerated person during their incarceration. At program reviews, BOP staff are to review progress in recommended programs, and recommend new programs based upon skills the incarcerated person has gained during incarceration. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Classification and Program Review, 5322.13 (Washington, D.C.: May 16, 2014).

eAccording to BOP policy, staff are to reassess the incarcerated individuals’ risk and needs at the program review meetings which are to occur every 180 or 90 calendar days if the incarcerated person is within 12 months of their projected release date. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Classification and Program Review, 5322.13 (Washington, D.C.: May 16, 2014).

Agency Roles and Responsibilities

Federal Bureau of Prisons. Generally, the FSA requires BOP to ensure all incarcerated people have a recidivism risk level assigned, assess the criminogenic needs of each person, provide programs and activities to address people’s needs, and apply FSA time credits to eligible incarcerated people’s sentences.[34] Within BOP, the Central Office divisions, regional offices, facility departments, and Residential Reentry Management Branch staff have various FSA-related responsibilities, among other duties.

· At the Central Office, staff from various divisions are responsible for the oversight and guidance on the risk and needs assessments. The Central Office is to also oversee the application of FSA time credits. The Designation and Sentence Computation Center is to screen incarcerated people, assign them to a BOP facility that aligns with their security level and basic needs, and enter data into SENTRY that tracks each incarcerated person’s security and custody level classification data.

· Regional offices may monitor some FSA processes at the facilities, such as reviewing data on FSA processes from each facility. Specifically, BOP’s six regional offices may collect data from the facilities on missing needs assessments, program participation, and time credit eligibility, among others.

· At BOP facilities, the unit team is responsible for implementing and overseeing the risk and needs assessment system. Each unit team consists of a unit manager, case manager, and counselor. Specifically, case managers are to conduct, or ensure other BOP staff conduct, risk and needs assessments. Facility staff from the education and recreation services, health services, and psychology services departments are responsible for conducting initial needs assessments and entering data into SENTRY. These departments, plus some other departments, offer programs and activities to the incarcerated population. As of April 2025, BOP had 120 secure facilities (prisons).

· Unit team staff are also responsible for initiating an incarcerated person’s transfer to prerelease custody by referring the person to one of BOP’s Residential Reentry Management offices for placement in a residential reentry center or home confinement. The Residential Reentry Management Branch staff assess the person’s situation, such as a potential location for home confinement, and their history and needs to determine the prerelease custody placement that would best transition them to living in the community again.

Department of Justice. Under the FSA, generally, the Attorney General’s responsibilities include the following activities:

· Annually review, validate, and release publicly on DOJ’s website the risk and needs assessment system. This review includes any changes and a statistical validation of the risk and needs tools.[35]

· Conduct ongoing research and data analysis on evidence-based recidivism reduction programs, among others.[36] Under this requirement, DOJ must conduct research on which programs are most effective at reducing recidivism, and the type, amount, and intensity of programming that most effectively reduces the risk of recidivism.

· Submit an annual report to certain committees of Congress that summarizes the Attorney General’s FSA-related activities and accomplishments, among other things.[37]

BOP Is Taking Steps to Monitor Risk and Needs Assessments, and DOJ Validated the Risk and Needs Assessment System

While BOP staff are conducting risk and needs assessments as required by the FSA, as of December 2024, they are not conducting all assessments within FSA required or internal time frames. However, BOP plans to enhance an application to better monitor whether assessments are conducted within these time frames. Additionally, DOJ validated the risk and needs assessment system as required by the FSA.

BOP Conducted Some, but Not All, Risk and Needs Assessments Within FSA Required and Internal Time Frames

BOP conducted most initial risk assessments and many initial needs assessments within internal time frames. For reassessments, BOP was generally more timely for first reassessments than for second and third reassessments.[38]

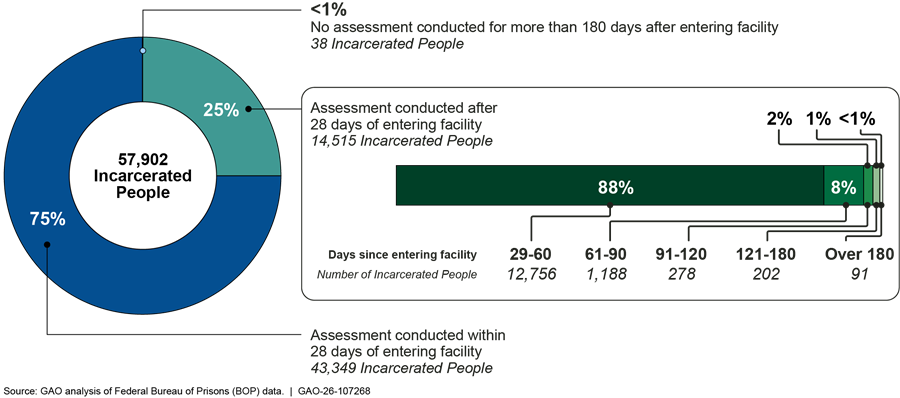

Initial Risk Assessments

BOP staff conducted most, but not all, initial risk assessments within internal time frames. According to BOP policy, staff are required to conduct initial risk assessments for incarcerated people in conjunction with their initial classification meeting, which should be within 28 calendar days of their arrival at their designated BOP facility.[39] As shown in Figure 6, we examined a selected cohort of incarcerated people who entered BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024.[40] We found that BOP conducted initial risk assessments within 28 calendar days for about 75 percent (43,349) of the 57,902 incarcerated people in the selected cohort. For those in the selected cohort whose initial risk assessment was late (14,515), BOP staff conducted these assessments within 60 days for almost 88 percent of these individuals (12,756).

Figure 6: Percent of Selected Cohort of Incarcerated People by When Initial Risk Assessment Was Conducted

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for a cohort of incarcerated people who started their sentence and entered a designated BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024. According to BOP policy, BOP staff are required to conduct initial risk assessments within 28 calendar days of an incarcerated person’s arrival at their designated BOP facility.

BOP facility staff at all four facilities we visited stated that they believe the reason for the late assessments was due to a missing sentence computation.[41] According to BOP officials, the Designation and Sentence Computation Center must complete the sentence computation before BOP staff can conduct a risk assessment. Designation and Sentence Computation Center staff must complete the sentence computation within 60 days of the date that BOP determines where a person will serve their sentence, depending upon the person’s sentence length.[42] BOP facility staff must complete the initial risk assessment within 28 days of a person arriving at a facility. As such, the time frames to complete these processes may not align. However, initial risk assessments that are not conducted within 28 days do not affect an incarcerated person’s ability to be in earning status. Once BOP completes a person’s initial risk assessment, they will retroactively begin earning time credits, as long as they are eligible and otherwise in earning status.

Initial Needs Assessments

According to our analysis, BOP conducted many, but not all, initial needs assessments within internal time frames. While BOP staff are to complete risk assessments during an incarcerated person’s initial classification meeting, the initial needs assessments are to be conducted within 30 days of the incarcerated person’s arrival at a designated BOP facility.[43] Of the 13 initial needs assessments, BOP staff conduct seven independently and another two with participation from the incarcerated person. The incarcerated person completes self-assessments for the remaining four needs.

Specifically, as shown in table 1, the extent to which BOP conducted initial needs assessments within internal time frames for those in the selected cohort varied by need and which department was responsible for the assessment.

Table 1: Percent of Incarcerated People with Initial Needs Assessments Conducted Within BOP Internal Time Frames, by Department and Person Responsible

|

BOP Facility Department |

Area of Need |

Person Responsible for Assessment |

Percent |

|

Education |

Dyslexia |

BOP staff and incarcerated person |

93% |

|

Education |

Education |

BOP staff |

—a |

|

Education |

Work |

BOP staff |

95% |

|

Health Services |

Medical |

BOP staff |

84% |

|

Health Services |

Recreation/Leisure/Fitness |

BOP staff |

83% |

|

Psychology Services |

Anger/Hostility |

Incarcerated person (self-assessment) |

69% |

|

Psychology Services |

Antisocial Peers |

Incarcerated person (self-assessment) |

68% |

|

Psychology Services |

Cognitions |

Incarcerated person (self-assessment) |

68% |

|

Psychology Services |

Family/Parenting |

Incarcerated person (self-assessment) |

69% |

|

Psychology Services |

Mental Health |

BOP staff |

69% |

|

Psychology Services |

Trauma |

BOP staff and incarcerated person |

91% |

|

Unit Management |

Finance/Poverty |

BOP staff |

90% |

|

Unit Management |

Substance Use |

BOP staff |

—b |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data. | GAO‑26‑107268

Note: For this table, we analyzed data for a cohort of incarcerated people who started their sentence and entered a designated BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024. The total size of the cohort population with initial needs assessments was 57,902 people. Initial needs assessments are to be conducted within 30 days of the incarcerated person’s arrival at a designated BOP facility.

aFor the education need, BOP recorded data in the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) needs assessments field for 38 percent of incarcerated people within 30 days, respectively. However, BOP stated that assessments for this need may have been conducted but were documented in a different data field that we did not examine.

bFor the substance use need, BOP recorded data in the FSA needs assessments field for 36 percent of incarcerated people within 30 days, respectively. However, BOP stated that assessments for this need may have been conducted but were documented in a different data field that we did not examine.

We found that BOP conducted seven of the nine needs assessments that staff were solely or partially responsible for within 30 days for 69 percent to 95 percent of the 57,902 incarcerated people in the selected cohort.

For the remaining two needs that staff were responsible for conducting, education and substance use, we were unable to determine when these assessments were done due to data limitations. Specifically, while our data analysis found BOP staff conducted these two initial needs assessments within 30 days for approximately one third of the people incarcerated during this time, BOP officials said that these data were not accurate. Officials explained that BOP assessed these two needs using specific data fields prior to the FSA—different than the FSA data fields we analyzed. For example, staff completed a data field in SENTRY that determined if the incarcerated person had a high school diploma or equivalency for the education need. When BOP staff complete this data field, they do not also enter data into the FSA needs data field in SENTRY. However, these assessments do get recorded during the reassessment when staff press the FSA assessment button. As a result, BOP officials stated that BOP staff are generally conducting these needs assessments within internal time frames, but they are not reflected in the FSA data we analyzed.[44]

According to BOP officials, they are working to improve their FSA processes, but technology limitations and staffing shortages have delayed some inputs of initial needs assessments. However, for initial needs assessments that staff are solely or partially responsible for completing, assessments not conducted within internal time frames do not affect an incarcerated person’s ability to be in earning status for FSA time credits.

For the four initial needs assessments that incarcerated people complete through self-assessments, nearly 70 percent of the people in the selected cohort completed each within 30 days of their arrival. The remaining 30 percent could include people who did them after 30 days or refused to complete them. BOP places incarcerated people in a refusal status if they do not complete their self-assessments. BOP facility staff said that some incarcerated people refused to complete their self-assessments. Additionally, incarcerated people may not complete their self-assessments because the system timed out, the person neglected to answer every question in the assessment, or the person was unaware they needed to complete the self-assessments.[45] BOP staff stated that the refusal rate for self-assessments has decreased over time because BOP staff and other incarcerated people informed those newly incarcerated about the process.

Risk and Needs Reassessments

BOP conducted many, but not all, reassessments within FSA required and internal time frames for the incarcerated people in the selected cohort who were incarcerated long enough to have these reassessments.

FSA required time frames. Generally, the FSA requires BOP to reassess each incarcerated person’s risk level annually.[46] We found that BOP conducted the vast majority (99.6 percent) of first risk reassessments within 365 days for incarcerated people in our selected cohort, as required by the FSA.[47] Further, BOP conducted 99.8 percent of second and third risk reassessments within 365 days of the previous assessment.[48]

BOP internal time frames. BOP internal time frames require staff to complete risk and needs assessments during program review meetings, which occur more frequently than the FSA requirements.[49] Specifically, BOP policy requires that staff conduct these meetings every 180 days or at least once every 90 days when an incarcerated person is within 12 months of their projected release date.[50]

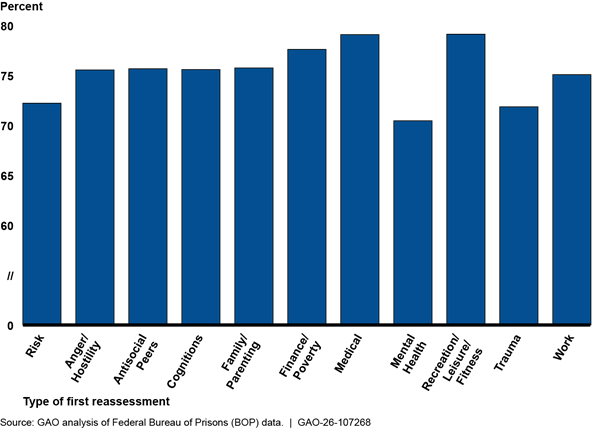

We found that BOP conducted first risk and needs reassessments within internal time frames for 70 to 79 percent of incarcerated people in the selected cohort, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Percent of Incarcerated People with First Risk and Needs Reassessments Conducted Within BOP Internal Time Frames

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for a cohort of incarcerated people who started their sentence and entered a designated BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024, and that were incarcerated long enough to have a first reassessment for risk and 10 needs. Populations varied for each risk and needs assessment based on the number of incarcerated people in this cohort who had been incarcerated long enough for a first reassessment. Populations ranged between 54,478 for the antisocial peers need and 56,748 for the work need. BOP reassesses 12 of the 13 needs for incarcerated people. BOP does not reassess dyslexia. In addition, we did not include two other needs, education and substance use, because we identified data limitations with the initial assessments. For this analysis, we compared the initial assessment date to the first reassessment date. While BOP’s FSA assessment button conducts reassessments for risk and needs simultaneously, initial assessments are not done at the same time. As a result, the amount of time to complete a reassessment may vary per risk or need.

The percent conducted within internal time frames decreased for subsequent reassessments for risk and each need that was analyzed.[51] For example, BOP conducted first reassessments for the recreation/leisure/fitness need for almost 79 percent of people in our selected cohort who were incarcerated long enough to have a first reassessment (44,735 of 56,551). However, for people incarcerated long enough to have second and third reassessments, BOP conducted those reassessments for 69 percent (36,128 of 52,738) and 66 percent (26,860 of 40,484) of incarcerated people, respectively. For those incarcerated people for whom BOP did not conduct their first risk or needs reassessments within internal time frames (11,382 to 15,374 people), BOP varied in how late it was in conducting these reassessments.

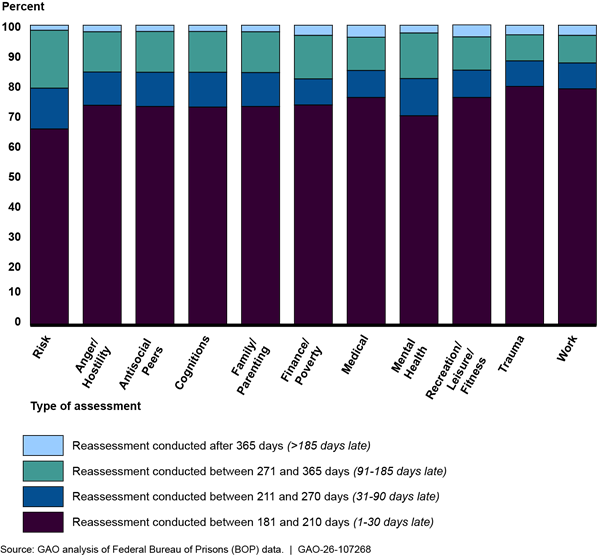

People with more than 1 year remaining on their sentence. For incarcerated people whose risk and needs BOP should have first reassessed at 180 days but did not, BOP conducted reassessments for the majority of these individuals between 181 and 210 days after their initial assessment (1 to 30 days late), as indicated in figure 8. We found a similar pattern when we analyzed second and third reassessments for risk and needs that were not conducted within internal time frames.

Figure 8: Percent of Incarcerated People with Late First Reassessments (Conducted After 180 Days), by Number of Days

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for a cohort of incarcerated people who started their sentence and entered a designated BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024, and were incarcerated long enough to have a first reassessment for risk and 10 needs. This figure includes people whose first reassessments were not conducted within internal time frames (180 days) and had more than 1 year remaining on their sentence at the time of their first reassessment. It does not include people for which BOP conducted reassessments on time. The number of incarcerated people with more than 1 year remaining on their sentence with first reassessments conducted after 180 days ranged between 7,195 for the finance/poverty need and 10,265 for the trauma need. BOP does not reassess dyslexia. In addition, we did not include two other needs, education and substance use, because we identified data limitations with the initial assessments. For this analysis, we compared the initial assessment date to the first reassessment date. While BOP’s assessment button conducts reassessments for risk and needs simultaneously, initial assessments are not done at the same time. As a result, the amount of time to complete a reassessment may vary per risk or need.

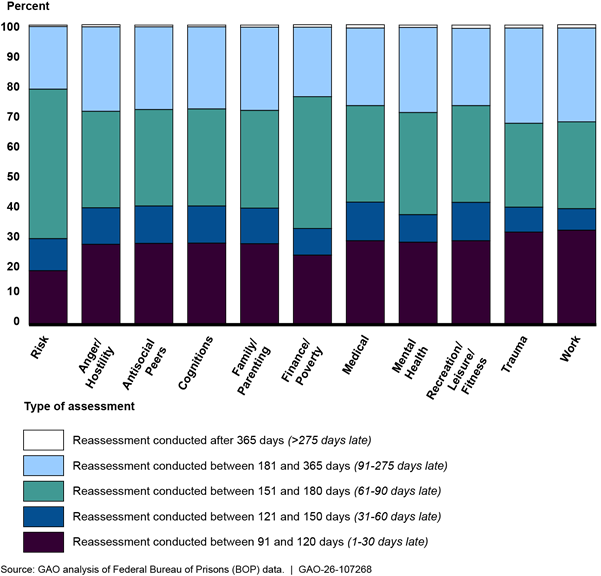

People with 1 year or less remaining on their sentence. For incarcerated people whose risk and needs BOP should have first reassessed at 90 days but did not, BOP most frequently conducted these reassessments 151 to 180 days after their initial assessment (61 to 90 days late) for risk and 8 of the 10 needs, as indicated in figure 9. For the trauma need, BOP most frequently conducted this assessment 181 to 365 days after their initial assessment (91 to 275 late). For the work need, BOP most frequently conducted this assessment 91 to 120 days after their initial assessment (1 to 30 days late). Further, if BOP would have been required to first reassess these individuals at 180 days, rather than 90 days, BOP would have conducted most of these assessments (67 to 79 percent) within internal time frames.

Figure 9: Percent of Incarcerated People with Late First Reassessments (Conducted After 90 Days), by Number of Days

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for a cohort of incarcerated people who started their sentence and entered a designated BOP facility from June 1, 2022, to March 30, 2024, and were incarcerated long enough to have a first reassessment for risk and 10 needs. This figure includes people whose first reassessments were not conducted within internal time frames (90 days) and had 1 year or less remaining on their sentence at the time of their first reassessment. It does not include people for which BOP conducted reassessments on time. The number of incarcerated people with 1 year or less remaining on their sentence with first reassessments conducted after 90 days ranged between 4,127 for the medical need and 7,132 for risk. BOP does not reassess dyslexia. In addition, we did not include two other needs, education and substance use, because we identified data limitations with the initial assessments. For this analysis, we compared the date of the initial assessment to the first reassessment date. While BOP’s assessment button conducts reassessments for risk and needs simultaneously, initial assessments are not done at the same time. As a result, the amount of time to complete a reassessment may vary per risk or need.

BOP facility staff highlighted technology issues as the primary driver of late reassessments. To conduct reassessments, BOP staff use a tool that pulls data from SENTRY to automatically reassess both risk and needs when staff press the FSA assessment button. One specific technology issue noted by both BOP staff at the facilities we visited and union officials was that there would be instances where staff would press the FSA assessment button, but the system would not record an assessment. In addition, staff noted that sometimes the system would not allow them to conduct an assessment if they were too far ahead of the reassessment timeline. BOP Central Office officials stated that most of these technology issues have since been resolved or were the result of issues with a specific incarcerated person’s information rather than system-wide issues. This normally requires staff and officials to look over the person’s specific case and resolve whatever parts of the file are causing the technology issues before a reassessment can be conducted.

In addition, BOP facility staff provided an explanation as to why 90-day reassessments may not be conducted within internal time frames. Specifically, these staff stated that there is nothing in SENTRY that indicates when an incarcerated person transitions from 180 to 90-day reassessments. Further, these staff stated that SENTRY does not automatically populate the next date for an incarcerated person’s program review meeting. Instead, facility staff manually calculate the date of the next program review meeting and enter that date into SENTRY.

BOP officials stated that they plan to enhance the automated-calculation application to ensure that risk and needs reassessments are conducted according to FSA required and internal time frames, as we discuss in more detail below. Implementing such enhancements will help ensure that incarcerated people are awarded the maximum amount of FSA time credits. While late initial assessments and reassessments may not affect an incarcerated person’s ability to earn FSA time credits—unless they choose to not complete self-assessments—it may affect how many time credits they can earn. Specifically, if risk assessments are delayed, that may affect how long it takes for an individual to demonstrate consecutive low or minimum risk levels which would allow them to earn 15 days of FSA time credits for every 30 days they are in earning status.[52] Further, if initial needs assessments are delayed, then incarcerated people may be delayed in signing up for evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities that could help address their needs and potentially reduce their recidivism risk.

BOP Is Taking Steps to Better Monitor the Timeliness of Risk and Needs Assessments

BOP conducted some monitoring of the timeliness of risk and needs assessments at the regional and facility level and plans to enhance its automated-calculation application to better monitor whether these assessments are conducted within FSA and internal time frames. For example, BOP officials stated they currently rely on supervisors, such as unit managers and case management coordinators, to monitor assessment timeliness. At all four facilities we visited, officials stated they ran weekly, and sometimes monthly, reports to ensure that case managers are completing their initial risk and needs assessments on time. At some facilities, staff with FSA expertise also monitored the completion of initial assessments through reports and provided this information to the regional office. In addition, two of the three regional offices we spoke with asked facility staff to send them monthly reports that included information on missing needs assessments.[53]

In 2023, we reported on limitations in BOP’s monitoring efforts, finding that BOP had not confirmed whether its monitoring efforts would measure timeliness of risk and needs assessments.[54] We recommended that BOP ensure that the monitoring efforts it implements can determine if BOP is conducting assessments in accordance with FSA required and internal time frames. In addition, we recommended that BOP use and document the results of this monitoring to take appropriate corrective actions, as needed.

In response to our 2023 recommendation on limitations in BOP’s efforts to monitor assessment timeliness, BOP officials stated they were in the process of enhancing their automated-calculation application of FSA time credits. According to officials, this enhanced application will integrate risk and needs reassessments into a single, monthly automated process.[55] Through this application, BOP officials stated they would be able to ensure that risk and needs reassessments are conducted in accordance with FSA required and internal time frames.

Once implemented, this application should be able to address the issues with late risk and needs reassessments identified above. For example, the application will record a reassessment if there is a change to an incarcerated person’s records, such as when a person completes a program. This should help alleviate technology issues that prevent a reassessment from taking place when BOP facility staff attempt to run these reassessments. Further, BOP officials stated that running this application monthly would ensure that a new reassessment is conducted if any of the incarcerated person’s records changed in the last month.

In addition, the application will populate initial assessment results, if missing, for six needs when the monthly automated process occurs. Specifically, the application will extract information, if available, from other data fields in SENTRY. For example, for the education need, the application would search the high school diploma or equivalency data field and record an initial assessment, if missing. However, the application will not populate initial assessment results for the other seven needs. Missing initial assessments for three of these needs will not affect an incarcerated person’s ability to earn FSA time credits.[56] The remaining four needs are self-assessments, which are the responsibility of the incarcerated person to complete and do affect their ability to earn FSA time credits.

BOP originally anticipated initial implementation of the enhanced application in September 2023. However, BOP officials stated that implementation has been delayed due to staff shortages and the departure of key personnel. Further, in December 2025, BOP officials stated that they would begin working on the application after they replace SENTRY with a new system, which they anticipate occurring in September 2026.[57] Taking action to implement the application as intended would help ensure that risk and needs reassessments are completed within FSA required and internal time frames, in line with our previous recommendation.

DOJ Validated the Risk and Needs Assessment System as Required

Since it was first implemented in 2019, the National Institute of Justice, on behalf of DOJ, has validated PATTERN on an annual basis, as required by the FSA.[58] DOJ issued its most recent revalidation report for PATTERN version 1.3 in August 2024. In this report, National Institute of Justice researchers found that racial and ethnic biases persisted since the implementation of PATTERN version 1.2 in 2020.[59] Specifically, the report stated that the transition to the current version of PATTERN neither exacerbated nor solved these racial bias issues overall. However, the over-prediction of recidivism for Black males and females worsened, whereas the over-prediction for Hispanic males was mitigated when compared to previous reports.[60]

National Institute of Justice’s review of recidivism rates of similarly classified incarcerated people found that PATTERN version 1.3 over or under-predicted the risk of recidivism for certain groups. For example, regarding general recidivism, PATTERN tended to over-predict recidivism for Asian, Black, and Hispanic people and under-predict for Native American people, compared to White people. According to DOJ officials, while they have not identified an ideal solution, the researchers continue to develop strategies to reduce these biases. For example, researchers are assessing the viability of obtaining reconviction data, which they would use instead of rearrest data. However, it is too soon to tell if they will be able to collect and use these reconviction data.

Further, in September 2024, DOJ published the first validation report for BOP’s needs assessment system, SPARC-13. The report found that some of the initial needs assessments BOP used did not measure the needs they were intended to measure, and most incarcerated people are not participating in programs to address their identified needs.

To address these findings, the SPARC-13 validation report made 10 recommendations to improve SPARC-13 and the risk and needs assessment system more generally. The recommendations focused on: (1) potential improvements to SPARC-13 to more accurately reflect the needs of the incarcerated population, (2) better aligning needs assessments with available programming, (3) additional training to facilitate the use of risk-need-responsivity principles and skills, and (4) combining PATTERN and SPARC-13 into one unified system.[61] See appendix IV for a description of each of these recommendations. In January 2025, BOP officials stated they were in the process of reviewing and evaluating the feasibility of implementing these recommendations.

DOJ and BOP Are Evaluating and Offering Programs but Data Inaccuracies Limit Monitoring

DOJ and BOP have taken steps to evaluate BOP’s evidence-based recidivism reduction programs to ensure they are effective at reducing recidivism, as required by the FSA.[62] Additionally, BOP officials said they offer evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities (programs and activities) that address all 13 needs. However, we found that few incarcerated people were able to complete programs or activities. Further, BOP does not have accurate data on programs and activities, such as participation and waitlist data, to determine if each facility offers sufficient programs and activities for its incarcerated population. Lastly, BOP Central Office does not collect, and is not monitoring, standardized bureau-wide data that are readily accessible on whether incarcerated people have work assignments.

DOJ and BOP Are in the Process of Evaluating BOP’s Programs

As required by the FSA, DOJ and BOP have taken steps to evaluate BOP’s evidence-based recidivism reduction programs to ensure they are effective at reducing recidivism.[63] Specifically, DOJ is required to evaluate these programs on an ongoing basis to determine which are the most effective at reducing recidivism, among other requirements.[64] BOP has taken the lead on this requirement and developed a plan to evaluate these programs over time—some of which BOP has, or plans to, contract external entities to complete.

As of September 2025, BOP has completed evaluations for two of its 48 evidence-based recidivism reduction programs—the Federal Prisons Industries and the Anger Management program.[65] BOP has initiated or contracted evaluations for 17 additional programs that are underway—including two programs for which it completed initial retrospective evaluations.[66] BOP officials stated they continue to initiate evaluations and that these would be long-term efforts. According to BOP, plans for future evaluations are dependent upon the availability of resources and funding.[67]

|

Anger Management Program Evaluation BOP’s evaluation of its Anger Management Program reported a small impact on recidivism rates. For this evaluation, BOP contracted with an external entity to evaluate its Anger Management Program, and the contractor issued the evaluation report in August 2024. The evaluation concluded, among other things, that incarcerated people who completed the program and were reincarcerated generally returned to the prison system 1 year and 8 months after release. This was longer than those who did not complete the program—they generally returned to the prison system 1 year and 5 months after release. The report did not state whether this difference was statistically significant. In addition, overall, incarcerated people reported to the researchers that the program was helpful. However, BOP staff and incarcerated people said that areas of improvement included the need for more resources (including staffing and classroom space), people’s access to the program earlier in their sentences, shorter waitlist time, and fewer disruptions during programming. Source: Texas Christian University Report. Federal Bureau of Prisons Anger Management Program Evaluations. (Aug. 27, 2024). | GAO‑26‑107268 |

As we reported in 2023, BOP developed an evaluation plan for the programs that it provides to the incarcerated population.[68] We identified limitations with its plan and recommended that BOP include clear milestones and quantifiable goals that align with FSA requirements in its plan. Specifically, the FSA requires the Attorney General to conduct ongoing research and data analysis on which evidence-based recidivism reduction programs are the most effective at reducing recidivism, and the type, amount, and intensity of programming that most effectively reduces the risk of recidivism.[69] In response to this recommendation, BOP updated its plan to include milestone dates. However, BOP has not documented how it will determine which programs are the most effective at reducing recidivism or the type, amount, and intensity of programming that most effectively reduces the risk of recidivism. We will continue to monitor BOP’s progress in evaluating its programs according to FSA requirements.

In addition, in 2022, BOP contracted with an external entity to evaluate whether the programs and activities it offers qualified as either evidence-based recidivism reduction programs or productive activities. Specifically, the contractor was tasked with reviewing the 38 programs and 50 activities in BOP’s 2022 Approved Programs Guide.[70] To do this, the contractor conducted a literature review.

The contractor issued a report on its findings that contained several recommendations to BOP, such as increasing program availability and conducting regularly scheduled program evaluations, which we also previously recommended.[71] For a list of the contractor’s recommendations, see appendix V. In January 2025, BOP officials said that they generally concurred with many of the recommendations in principle, but implementation will depend on resource availability, operational feasibility, and alignment with statutory requirements under the FSA.

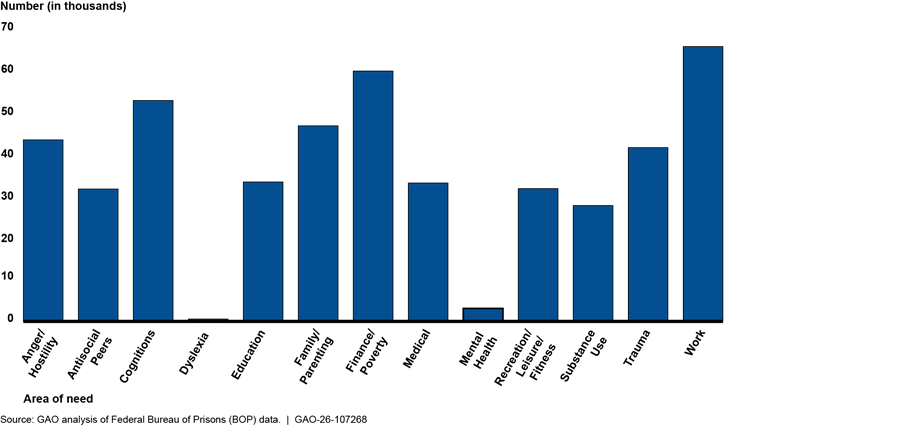

BOP Is Taking Steps to Monitor if It Offers Sufficient Programs and Activities

BOP reports offering programs and activities to meet incarcerated people’s needs and is taking steps to monitor if it is offering sufficient programs and activities to meet these needs. Our analysis of program data showed that people incarcerated in a BOP facility on December 31, 2024, had on average nearly five needs per person.[72] Specifically, work and finance/poverty were the most common needs, as shown in figure 10.[73]

Figure 10: Number of People Incarcerated at a BOP Facility with Each Criminogenic Need, as of December 31, 2024

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for all sentenced and incarcerated people in a designated BOP facility as of March 30, 2024, who were still incarcerated on December 31, 2024 (98,254 people). These data represent their needs as of December 31, 2024. However, not all incarcerated people had each of their needs assessed by this date, so the total for each need may vary. Criminogenic needs are characteristics of a person that directly relate to their likelihood to commit another crime.

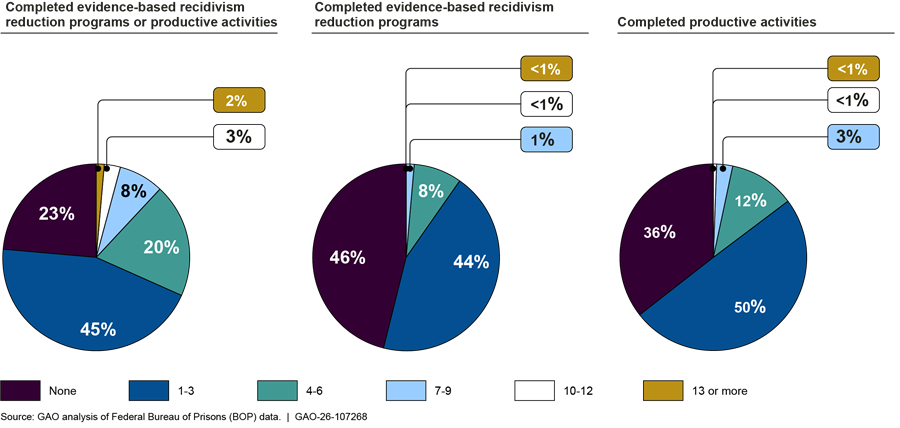

BOP officials stated that all their facilities offer evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities for all 13 areas of need to help incarcerated people address their needs. However, we found that over 23 percent (32,684) of incarcerated people did not complete any programs or activities from 2022 through 2024—including programs that may help to address their needs.[74] Further, we found that 44 percent completed one to three evidence-based recidivism reduction programs, and almost 50 percent of people completed one to three productive activities, from 2022 to 2024, as shown in figure 11.

Figure 11: Percentage of Incarcerated People at a BOP Facility that Completed Evidence-Based Recidivism Reduction Programs or Productive Activities, 2022 through 2024

Note: For this figure, we analyzed data for all sentenced and incarcerated people in a designated BOP facility as of March 30, 2024 (139,896 total people). The analyzed data comprise all programs and productive activities completed by these individuals from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2024.

Additionally, according to a 2023 National Institute of Justice report evaluating the FSA needs assessments, most people in a BOP facility were not enrolled in a program or activity that addressed their identified needs.[75] The report stated there were generally low levels of program participation, noting that an average of 95 percent of people were not participating in programming to address an identified need.[76] The report identified various reasons why this may be the case, including that some programs are meant to be offered closer to the incarcerated person’s release. Due to these reasons, the report stated that these findings are preliminary and should be considered provisional until more detailed analyses can be performed. BOP officials stated the report’s data appear to show a single snapshot of program participants on a given day rather than over a quarter or year which would better illustrate programming efforts. They stated that their data show a higher percentage of the incarcerated population is actively participating in one or more programs.

|

Incarcerated People’s Perspectives on Addressing Needs Some of the 16 incarcerated people we interviewed said they have been able to address most of their needs while incarcerated. However, others said they have not been able to address needs and provided some reasons. For example, three people said they were unable to address some of their identified needs due to long waitlists for the necessary programs. Another person said that there have been lockdowns at the facility, and they have been unable to complete the needed programs as a result. Source: Interviews with Incarcerated People. | GAO‑26‑107268 |

According to BOP officials, staff at each facility determine which programs and activities to offer and at what frequency. Specifically, department supervisors and other facility staff said they choose the programs they offer at their respective facilities from those listed in BOP’s FSA Approved Programs Guide.[77] When asked about the programs and activities that each facility offered at the time of our visit, staff at the four BOP facilities we visited said their facility was offering at least one program or activity to address each of the 13 needs. Staff at three of these facilities further elaborated that they always offer at least one program or activity to address each of the 13 needs. However, some BOP staff and incarcerated people stated that they believe their facilities do not offer enough programs, identifying various challenges such as limited programming space, insufficient staff to teach programs, and lockdowns. We reported on similar concerns in 2023.[78]

· BOP staff at three of the four facilities we visited said that the lack of physical space has hindered their ability to offer programs and activities. At one facility we visited, staff said they use alternative areas to hold class due to limited program space. This included using the chapel, meeting rooms, the visitation area, or the former restricted housing space. Although this facility was using alternative spaces for programs, officials said that they were also using funding from the FSA to build a new programming building. Figure 12 provides photographs of spaces used to hold programs—including a dedicated program space and a staff meeting room used for programs.

· BOP staff at all four facilities we visited said that there were insufficient staff to teach programs and activities.[79] They stated that additional staff would help the facilities to increase their program offerings. Additionally, BOP union staff stated that BOP struggles to offer sufficient programs across all facilities due to insufficient staff across BOP. Union officials previously shared similar concerns, as we reported in 2023, noting that BOP augmented staff up to two or three times a week, which took their time away from their normal duties.[80]

· BOP staff at one facility we visited said that lockdowns affect an incarcerated person’s ability to participate in programs because the facility temporarily stops or postpones classes and activities during lockdowns. The duration of lockdowns varies based on the event, and according to these staff, lockdowns can postpone programming for weeks or months until programming can safely continue.[81] Typically, during lockdowns, all incarcerated people are required to remain in their cells for the majority of the day.

Further, these challenges, described above, have contributed to long waitlists for programs and activities across facilities. BOP officials and incarcerated people said that long waitlists limit the ability of incarcerated people to participate in programs. We reviewed the case files of 16 incarcerated people. We found that 10 of these people were on a waitlist longer than 2 years for at least one program. One incarcerated person we spoke with said they had been on a waitlist for over 2 years for a program that would address one of their identified needs, and BOP staff were unable to tell them when they would be able to enroll in the program. Additionally, some incarcerated people we spoke with mentioned that being on waitlists for lengthy periods affected their ability to address their needs. According to BOP officials, some people may be on waitlists for lengthy periods because some programs are intended to be offered closer to a person’s release.

A shortage of programs and activities and long waitlists will not affect whether a person earns FSA time credits because incarcerated people earn these credits based on their earning status. However, a lack of programming may affect BOP’s ability to help incarcerated people address their needs and reduce their recidivism risk—a goal of the FSA. People can earn FSA time credits and be released early without completing or participating in any programs or activities.

In 2023, we recommended that BOP develop a mechanism to monitor if it is offering a sufficient amount of programs and activities.[82] In response to that recommendation, BOP officials said they planned to develop an FSA Reporting Dashboard to monitor FSA programming metrics, such as program participation by need. BOP Central Office officials said that the facility’s executive staff are to use this dashboard to help determine if they have a sufficient amount of programs to address the highest number of needs per facility. In January 2026, according to BOP officials, the bureau deployed the FSA dashboard.

Inaccurate Data Limit BOP’s Ability to Monitor Its Program Offerings

While BOP has worked towards deploying the FSA dashboard so it may monitor its program offerings, it has not taken steps to ensure it is collecting and maintaining accurate program data to inform the dashboard. BOP policy requires BOP staff to ensure that program data in SENTRY are accurate and up to date for each incarcerated person.[83] BOP officials stated that they created standardized codes in 2020 for most FSA program data in SENTRY, and staff are to use these codes to enter and track program data—such as who participates in, declines, completes, fails, or is placed on a waitlist for the program.[84] For example, BOP policy states that if a person refuses or declines to participate in a program or activity based on their need, staff should enter the program decline code into SENTRY.[85] Further, Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government state that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results.[86]

Further, from our analysis, we found that data on program completions were generally accurate; however, other program data were not accurate, such as data on program participation and who declines to participate or is placed on a waitlist.

For example, we found multiple inaccuracies in the program participation data.

· Across all but one of BOP’s facilities, we found 97 programs and activities that had only one incarcerated person participating as of March 30, 2024, including the Residential Drug Abuse Program. BOP Central Office officials told us that although some programs may run with just one participant, this is not a common practice. Officials said that those programs that had only one person participating were likely incorrect and could be “leftover” codes from a person’s former facility. They said only staff at the former facility could change these codes, and if they forgot to do so before transferring, these incorrect codes follow the person to their next facility.

· Our review of 16 incarcerated people’s case files showed that some incarcerated people participated in a program for a few days even though the program should take several months to complete. For example, one person was waitlisted for a program for over 200 days, participated in the program for 1 day, and completed the program the day they got off the waitlist. According to BOP officials at this facility, this program generally lasts 6 to 9 months. Therefore, it is likely the data in the system were inaccurate.

We also found instances in which data were inaccurate because staff did not consistently use the codes in SENTRY.

· At one facility, staff told us they generally did not enter data into SENTRY when an incarcerated person declines a recommended program. They stated they were told by management staff at their facility that participation in programs is voluntary, and they did not want the person to stop earning FSA time credits as a result. In contrast, staff at other facilities stated that they enter information into SENTRY when a person declines a program but only after they have discussed the implications of declining the program. Specifically, they require that the incarcerated person sign a paper indicating they understood they would not earn time credits as a result. Further, although this process was documented in a facility-specific memorandum, staff said that different departments have been given conflicting instructions on how and when to enter information into SENTRY when a person declines a program. According to staff from one of these facilities, they received an email from BOP Central Office that stated determining when an incarcerated person declines a program is subjective. Rather than using the decline code and the incarcerated person losing FSA time credits, staff can reenroll them on the bottom of the waitlist.

· Some department staff at the facilities we visited stated that their department directed them to use paper sign-up sheets for program waitlists, so they did not enter that information into SENTRY. In contrast, other department staff at these facilities noted that they enter waitlist information into SENTRY.

BOP Central Office officials said they rely on staff at the facilities to oversee the data entry process and that guidance on using standardized program codes in SENTRY is available to staff. Further, BOP officials acknowledged that while completion data are reliable, some programming data may not be reliable. While BOP officials said in July 2025 that they created new codes to help to mitigate data errors related to decline codes, BOP has not taken steps to ensure that all program data are accurate.

Without taking steps to ensure it is collecting and maintaining accurate program data, BOP cannot determine if it offers sufficient programming in its facilities to help meet the needs of incarcerated people. In particular, the FSA dashboard that BOP deployed in January 2026 to monitor this will not accurately reflect program information, such as program participation rates or waitlist times. Additionally, if staff are not consistently documenting when people decline programs, then some incarcerated people could be earning FSA time credits even though they refused to participate in a recommended program to address one of their needs.

BOP Central Office Does Not Have Bureau-wide Data That Are Readily Accessible to Monitor Work Assignments

BOP Central Office does not have bureau-wide data that are readily accessible to monitor work assignments of people incarcerated at BOP facilities. BOP policy states that each incarcerated person who is physically and mentally able should be assigned a work assignment.[87] One of these work assignments—the Federal Prison Industries—is an evidence-based recidivism reduction program that might help a person address their work need.

According to BOP officials, a person may be exempt from working for various allowable reasons, such as being in disciplinary segregation or for medical conditions. However, BOP officials and incarcerated people shared other reasons why incarcerated people may not work. For example, some staff from the facilities we visited said they do not have enough work assignments for each incarcerated person who is mentally and physically able to work. In another example, staff said that some people simply do not want to work and therefore do not apply for a work assignment. Some incarcerated people we spoke with said they were on a waitlist to work or waiting to hear back from the job they applied for. Other incarcerated people said that their facility did not have enough jobs or that they did not want to work.[88]

In our analysis of BOP data and case files, we identified various instances in which incarcerated people appeared to not have work assignments. For example:

· In our review of BOP’s work assignment data for people incarcerated in a BOP facility as of December 31, 2024, we found that about 22 percent (22,085 of 98,254 people) had a work assignment code that would likely indicate they are not working.[89] Specifically, they had a work assignment code in SENTRY that included some variation or spelling of “unassigned” or “idle,” which would likely indicate that they are not working.[90] We identified over 300 unique variations of these codes.

· We also found during our review of the 16 incarcerated people’s case files that five people had “unassigned” as their work assignment in SENTRY. For one person, we were able to identify an allowable reason that they were not working. However, we did not identify any information in the other four people’s case files that would explain why they may not have been working.

BOP Central Office officials stated that they do not know how many people are not working across the bureau who should be working. This is because BOP does not have standardized bureau-wide data that are readily accessible on whether incarcerated people have a work assignment, including if they have an allowable reason for not working. While BOP does collect some data, officials stated that they could not confirm which data codes meant that a person did not have a work assignment—including those with variations of “unassigned” or “idle.” According to these officials, facility staff create work assignment codes at each facility, and facility staff would have to identify the meaning of these codes. Further, these officials said that facility staff could check medical databases for medical conditions that may allow a person to not work.

According to BOP Central Office officials, they also do not monitor how many incarcerated people have a work assignment, including whether they have an allowable reason for not working. These officials said they rely on the facility to monitor work assignment data. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management is to use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, such as collecting relevant data.[91] In addition, these standards state that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results.[92]