AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL WORKFORCE

FAA Should Establish Goals and Better Assess Its Hiring Processes

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Chairman of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: Andrew Von Ah at VonAha@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) air traffic controllers help ensure the safety of U.S. air travel. However, lapses in appropriations in the 2010s, and the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in reduced controller hiring and increased attrition. In response, FAA has increased hiring every year since 2021. Nevertheless, at the end of fiscal year 2025, FAA employed 13,164 controllers, about 6 percent fewer than in 2015. Between fiscal years 2015 and 2024, total flights using the air traffic control system increased by about 10 percent to 30.8 million.

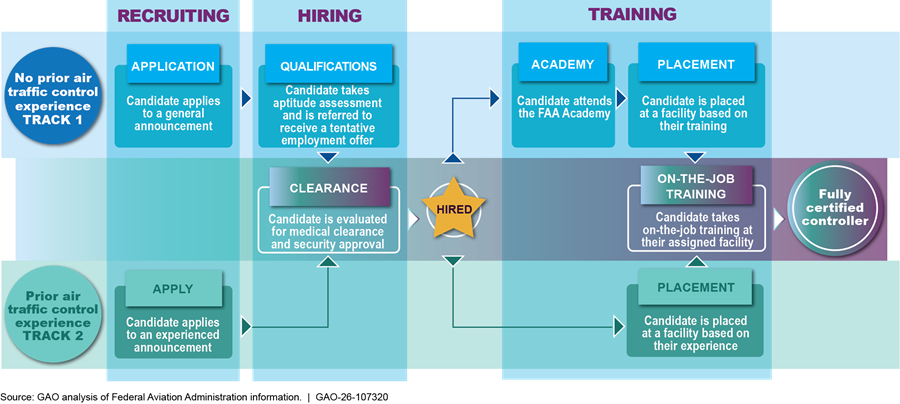

FAA uses a standardized process to hire controllers that begins with evaluating applicants’ performance on an aptitude test or their prior experience as an air traffic controller. Applicants must also meet medical and security standards and succeed at multiple types of training.

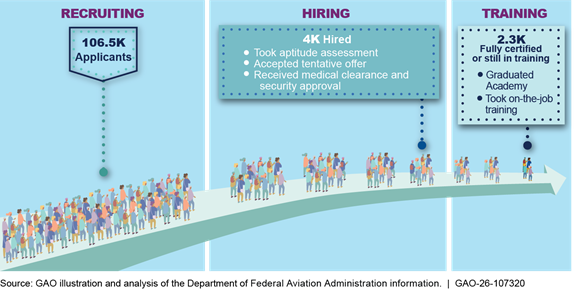

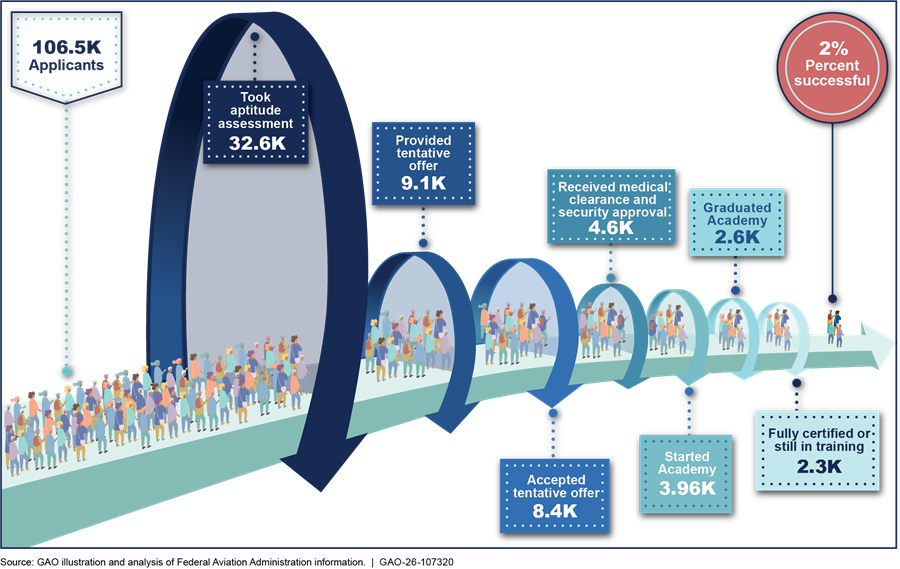

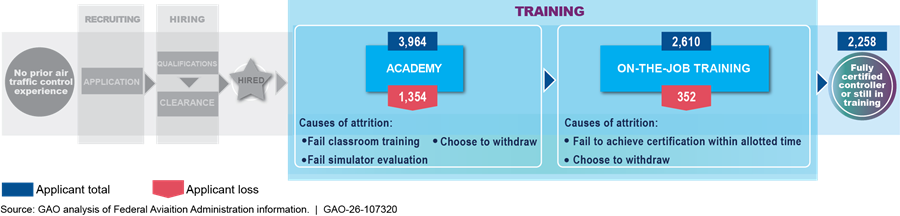

However, FAA’s processes for hiring and training controllers result in substantial attrition (see fig.). This occurs due to a limited portion of the population having the required aptitude, and the length and complexity of the processes—which can take 2-6 years. Specifically, the medical clearance process can take some applicants 2 years to complete. In response to these challenges, FAA has taken steps to accelerate the process, including adding resources to the medical clearance process and streamlining application review.

Attrition Across the FAA’s Processes for Hiring Air Traffic Controllers Without Prior Experience, Fiscal Years 2017-2022

GAO also found that FAA does not consistently assess its processes to recruit, hire, and train air traffic controllers. Specifically, FAA does not have performance goals for these processes and their resulting impact. Such goals help ensure accountability for achieving specific and measurable results. GAO also found that while FAA is taking steps to improve its collection of data on recruiting, hiring, and training, it does not consistently use these data to assess the results of its efforts and inform decision-making. Doing so could help FAA understand the performance of its processes, make the changes that would have the greatest effect on controller staffing, and keep otherwise qualified applicants on the track to becoming certified controllers.

Why GAO Did This Study

FAA, within the Department of Transportation, manages over 80,000 flights daily. FAA air traffic controllers perform this essential job that requires highly specialized skills and training. Over the last 10 years, FAA has faced staffing shortages at critical facilities.

GAO was asked to review FAA’s processes for hiring air traffic controllers. This report (1) describes the size and composition of the air traffic control workforce and changes since fiscal year 2015; (2) describes the processes FAA uses to recruit, hire, and train new controllers; (3) examines the steps FAA has taken to address challenges associated with recruiting, hiring, and training controllers; and (4) evaluates how FAA has assessed its efforts to hire air traffic controllers.

To address these objectives, GAO used FAA data to develop a dataset covering individuals from application through certification and used the data to analyze attrition in the controller hiring process. GAO also reviewed FAA documentation; visited the FAA training academy in Oklahoma City and air traffic control facilities near Chicago; Seattle; and Washington, D.C.; interviewed FAA officials and aviation industry stakeholders; and compared FAA’s efforts to assess its hiring processes with leading practices for evidence-based decision-making.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including that FAA (1) establish and document measurable goals for its processes to recruit, hire, and train controllers; and (2) analyze the information it collects to inform decisions about improving those processes. FAA agreed with the recommendations.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chairman,

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is responsible for operating the U.S. air traffic control system safely and efficiently by managing more than 80,000 flights each day in the world’s busiest airspace.[1] Currently, more than 13,000 FAA air traffic controllers perform the essential job of safely directing these flights in a challenging environment that requires highly specialized skills and training.[2] Over the last 10 years, FAA’s overall controller workforce has declined by 6 percent, while air traffic has increased by about 10 percent. This has resulted in staffing shortages at critical facilities. During the fall 2025 lapse in appropriations this became a major issue when controller absences reportedly increased, leading to significantly reduced flight schedules, delays, and cancellations.[3]

These shortages—also faced by air navigation service providers in other countries—have resulted in flight delays and cancellations and have raised questions from lawmakers, airlines, and FAA employee groups about the agency’s efforts to fully staff the air traffic control system. Further, some lawmakers and industry stakeholders have asked questions about whether staffing shortages could impact safety and increase the risk to the travelling public.

You asked us to review FAA’s processes for hiring air traffic controllers. This report

· describes the size and composition of the air traffic control workforce and the extent to which these characteristics have changed since fiscal year 2015;

· describes the processes FAA uses to recruit, hire, and train new air traffic controllers;

· examines the steps FAA has taken to address challenges associated with recruiting, hiring, and training air traffic controllers; and

· evaluates how FAA has assessed its efforts to hire air traffic controllers.

To describe the composition and size of the air traffic control workforce, we analyzed FAA human resources data and training data on performance at the FAA Academy and on-the-job training; we combined these data into a single merged dataset covering individuals from application through ultimate certification as an air traffic controller to identify the number of individuals that completed each step in the hiring and training processes.[4] This dataset covered applicants in fiscal years 2017 through 2024. We analyzed separate FAA data on the composition of the controller workforce for fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024.

To describe the processes FAA uses to recruit, hire, and train new air traffic controllers, we reviewed FAA documents, including its Human Resources Policy Manual and National Training Order, and interviewed officials from FAA’s Office of Human Resources and the Air Traffic Organization. To describe the challenges FAA faces in recruiting, hiring, and training new air traffic controllers and examine the steps it has taken to address them, we reviewed documentation and interviewed agency officials and aviation industry stakeholders, including organizations that represent controllers, equipment manufacturers, and airlines. We also visited the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and three air traffic control facilities near Chicago; Seattle; and Washington, D.C., to interview local officials about the processes FAA uses to train new air traffic controllers and the challenges they face. We compared FAA’s efforts to improve its communication with applicants to the applicable provisions of its 2022-2026 Strategic Plan and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government related to external communication.

To evaluate how FAA has assessed its efforts to achieve a fully staffed air traffic controller workforce, we reviewed FAA documents describing how it has assessed its recruiting, hiring, and training processes and compared its efforts with practices that can help federal organizations make evidence-informed decisions. For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FAA’s air traffic controllers play an important role in ensuring safety. They are responsible for ensuring that aircraft maintain a safe distance from one another and that each aircraft is on the proper course to its destination.

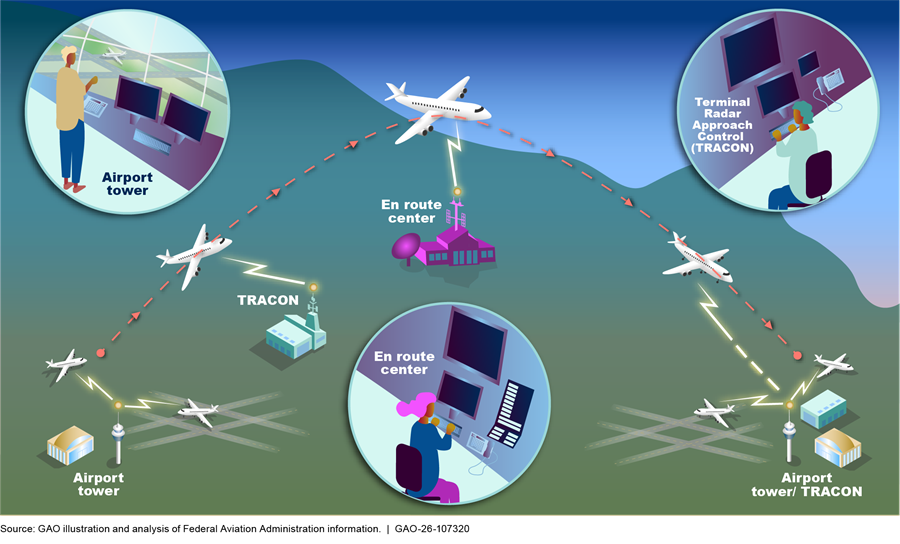

Air traffic controllers direct traffic from one of the 313 FAA-operated facilities, which are, in general, divided into three different types:

· Airport towers. Controllers at these facilities use visual reference to direct the flow of aircraft before landing, on the ground, and after takeoff; they do so from the vantage point of a cab on top of a tower located at an airport. FAA operates towers at 263 airports across the country.[5]

· Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON). Controllers at these facilities use radar to direct traffic arriving and departing from airports. Because these facilities use radar, rather than visual observation, to monitor air traffic, they are often in a dark room co-located with an airport tower. In busier areas with multiple airports, such as the New York area, these facilities may be located in a standalone facility. When a TRACON and a tower are at the same location, controllers are generally certified to work in both facilities. Because of this overlap, towers and TRACONs are collectively referred to as terminal facilities. FAA operates 146 TRACONs, of which 25 are standalone facilities, and 121 are combined with towers.

· Air Route Traffic Control Centers (en route center). Controllers at these facilities use radar to direct traffic outside or above a tower or TRACON airspace and over parts of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This traffic generally includes flights cruising at high altitudes and flights arriving to, or departing from, smaller airports without terminal facilities. These facilities resemble TRACON facilities, generally being dark rooms where controllers use monitors to track flights but use different specialized equipment for tracking aircraft over larger areas. FAA operates 21 en route centers. See figure 1 for the types of FAA-operated air traffic control facilities.

At each facility, controllers manage and direct one area, or aspect, of air traffic. For example, in a tower, one controller may be responsible for directing the movement of aircraft on the ground until they reach the runways, while others are responsible for directing aircraft taking off and landing from the active runways. In an en route center, different controllers may be responsible for different geographic sectors of the center’s airspace.

Control of an aircraft passes from one controller to another as the plane moves to its destination. Commercial flights generally pass from the control of a tower, to a TRACON, to an en route center—and then possibly one or more other centers, depending on the flight path—back to a TRACON, and finally to the destination tower.[6] At these facilities, equipment technicians, instructors, meteorologists, and other personnel perform essential tasks to support the certified air traffic controllers that direct traffic.[7]

FAA uses a staffing standard model to set a target staffing level for each air traffic control facility. This model—which FAA has used, with periodic updates, since the 1970s—uses an algorithm that relates to the estimated traffic levels at each facility and estimated controller workload and availability. FAA sets a yearly controller hiring target that it publishes in its annual Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan.

FAA hires new employees, referred to as “trainees” via two separate tracks:

· Track 1 is for applicants who have limited or no prior experience working as a controller and requires applicants to pass an aptitude assessment, obtain medical clearance and security approval, attend a 4-to-6-month training course at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, and continue with on-the-job training at a facility. This track also includes individuals that attended a Collegiate Training Initiative (CTI) program, a 2- or 4-year college program with an air traffic control curriculum.

· Track 2 is a more streamlined process to hire candidates who have previously worked as an air traffic controller. These applicants have worked either at a Department of Defense facility, a contract tower,[8] or served a prior term at an FAA facility. FAA does not require these candidates to take an aptitude assessment or attend the academy; they begin on-the-job training at a facility after they obtain their medical and security clearances. While FAA does not require Track 2 candidates to take an aptitude assessment as part of the hiring process before they begin on-the-job training, all controllers must pass a written knowledge exam to obtain their air traffic control tower operator certificate.[9]

FAA’s Workforce of Over 13,000 Air Traffic Controllers Is 6 Percent Smaller Than in 2015, with More Trainees Without Prior Exposure to Air Traffic Control

FAA’s Overall Air Traffic Controller Workforce Has Declined Since Fiscal Year 2015

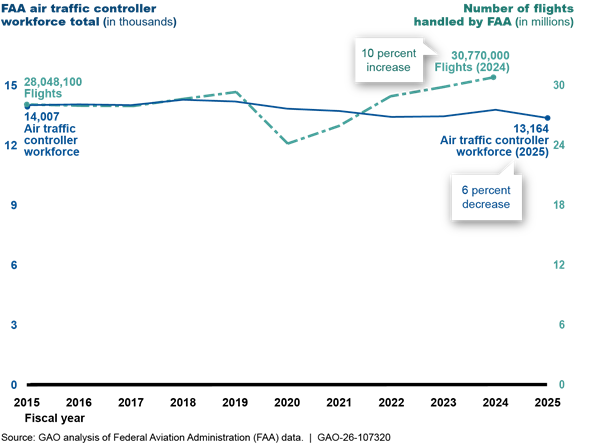

FAA employed fewer air traffic controllers overall in fiscal year 2025 than it did in fiscal year 2015, even though the number of flights increased through 2024, according to our review of FAA workforce data (see fig. 2). Specifically, FAA employed 14,007 controllers at the end of fiscal year 2015 and 13,164 at the end of fiscal year 2025, a decrease of about 6 percent.[10] Between fiscal years 2015 and 2024, the most recent data available, FAA’s estimate of the total number of flights using the air traffic control system increased about 10 percent, from 28.1 million flights to 30.8 million flights, including a rapid increase from the low in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2: Number of Air Traffic Controllers, Fiscal Years 2015-2025 and Flights Handled by FAA, Fiscal Years 2015-2024

Notes: The controller workforce total includes all

controllers currently at air traffic control facilities, including those in training.

It excludes students at the FAA Academy.

Number of flights is an estimate that includes flights under Instrument Flight

Rules and Visual Flight Rules that interacted with the air traffic control

system, as reported by FAA.

In addition to the decline in the number of total controllers, FAA has also faced challenges in providing adequate staffing at critical facilities. In 2023, the Department of Transportation’s Office of the Inspector General found that 20 of 26 critical facilities had staffing levels below 85 percent of FAA’s desired level.[11] In June 2025, the Transportation Research Board published a study recommending that FAA make improvements to its existing staffing model to make it more responsive to the actual conditions faced by individual facilities. The report also recommended that FAA make a concerted effort to staff its critical facilities at the levels its model recommends, including by using increased incentives for already certified controllers to transfer to those facilities.[12] In July 2025, FAA stated that it is considering the report’s recommendations and how they may be addressed in its future staffing models.[13]

Recruiting, hiring, and training new controllers from application to full certification is a continuous, multiyear process. According to FAA, any disruptions to this process can have significant, long-term impacts on controller staffing levels. FAA officials and stakeholders we spoke with identified several major disruptions that have impacted planned hiring levels and overall controller staffing:

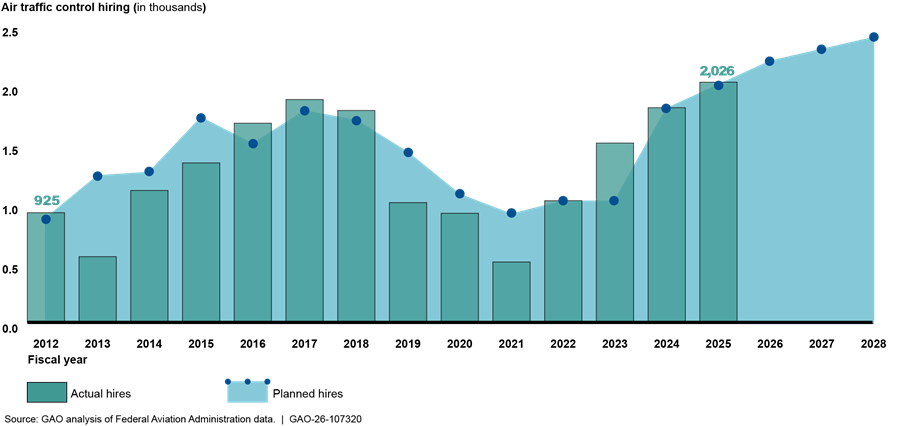

· Previous sequester and lapse in appropriations. Fiscal events since 2013 have substantially impacted FAA’s hiring and training of air traffic controllers. First, in March 2013, a government-wide discretionary sequester occurred, and FAA instituted a hiring freeze. In May 2013, a statute allowed FAA to transfer funds from other accounts to prevent reduced operations and staffing. FAA officials said that this statute provided the agency sufficient flexibilities to avoid furloughs and unnecessary pauses in hiring safety-critical employees. Nevertheless, sequestration still resulted in significantly reduced controller hiring in that year compared with the agency’s planned hiring targets. According to FAA’s Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plans, in fiscal years 2013 through 2015, FAA hired about 1,200 fewer controllers than it had originally planned. Subsequently, the 35-day lapse in appropriations from December 21, 2018, to January 25, 2019, stopped all hiring and training activities. This resulted in FAA missing the fiscal year 2019 hiring target it published in the 2018 Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan by about 400 controllers and delaying training for already hired trainees (see fig. 3). During the additional 43-day lapse in appropriations from October 1, 2025, to November 12, 2025, FAA officials told us that FAA classified air traffic controller hiring and on-the-job training as excepted activities and as a result they continued. Further, they said that FAA had sufficient prior-year funding to continue training at the FAA Academy for the entire duration of the lapse in appropriations.

· Reduced hiring and training during the COVID-19 pandemic. FAA’s hiring pipeline was interrupted as it suspended training at the FAA Academy for 4 months in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and then resumed training at significantly reduced rates during 2021 and 2022. For example, FAA hired around 500 new controllers in fiscal year 2021, as compared with an original goal of 910 (see fig. 3). In addition, during the pandemic, FAA prioritized staffing and safety protocols that minimized the number of staff in facilities to ensure continuity of operations over developmental controller training. This meant that on-the-job training at many facilities stopped or slowed down, resulting in delayed certification for most trainee controllers.

Figure 3: Hiring of FAA Air Traffic Controller Trainees Versus Planned Hiring, by Fiscal Years 2012-2028

Note: This figure depicts planned controller hiring as

published in the Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan from the year prior. For

example, the 2020 planned hiring figure is the number published in 2019. The

planned figures for 2026 through 2028 are those published in 2025.

· Unexpected workforce and traffic trends. Compounding these external difficulties, FAA also faced unexpected workforce and traffic trends after 2018 that its staffing models were unable to anticipate. For example, FAA planned for significantly reduced hiring in fiscal year 2019 after the number of controllers increased in fiscal year 2018. However, it instead lost 330 more controllers than expected to attrition between fiscal years 2019 and 2024, according to FAA’s Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plans. Further, according to stakeholders, it was difficult to predict how fast air traffic would increase after the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in FAA not sufficiently increasing the capacity of its training programs until 2023, well after it experienced increased demand for air traffic control services.

Recently FAA Has Hired More Trainees Without Prior Exposure to Air Traffic Control Than in Past Years

FAA has increased hiring of air traffic controller trainees to a large extent every year since 2021 (see fig. 3). As a result, the number of trainees FAA hired annually has returned to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels. Specifically, FAA hired 2,026 total trainee controllers in fiscal year 2025, which is about 100 more trainees than it hired in fiscal year 2017, and a substantial increase from the 500 it hired in fiscal year 2021.

According to FAA officials, while the agency attempts to hire as many controllers with prior experience as possible via the Track 2 pathway, in recent years fewer individuals with the required experience have been available to hire. According to our analysis of FAA data, the percentage of trainee controllers hired via Track 2 has decreased from 37 percent in fiscal year 2019 to 20 percent in fiscal year 2023 (the most recent full year of Track 2 hiring data available). This reflects a corresponding decline in applications from individuals with prior experience as air traffic controllers. FAA officials said that this is due to fewer controllers leaving military and civilian Department of Defense positions.

FAA has also hired a smaller proportion of trainees with previous exposure to the air traffic control profession by having attended a CTI program. Specifically, according to our analysis of FAA data, for Track 1 applicants in fiscal year 2019, about 25 percent of the trainee controllers FAA hired reported attending a CTI program. However, in fiscal year 2023, that figure had dropped to around 15 percent, reflecting a corresponding decline in applications from individuals who attended these programs. FAA officials said that some of this decline in the percentage of CTI graduates hired was due to Congress removing a previous limit on the number of trainees it could hire from the general public.[14]

With these decreases in the number of prospective controllers with prior experience or a CTI education, FAA has needed to hire more trainee controllers via Track 1 that are brand new to the profession. To do this, FAA has had to broaden its recruiting pipeline to include more members of the general public and relatively fewer individuals with previous exposure to air traffic control from collegiate programs or the military.

Despite the changes in the makeup of the applicant pool, our analysis of FAA’s hiring and training data shows that the demographic composition of the agency’s overall controller workforce did not change substantially from fiscal years 2017 to 2023. For example, in 2023, 76 percent of the total controller workforce identified as “White” and 15 percent as female, compared with 80 percent and 16 percent for those same groups in 2017. Over the same period, the proportion of controllers identifying as “Black or African American” remained the same, at 6 percent, while the proportion of controller identifying as “Two or More Races” increased from 7 percent to 11 percent.

FAA Uses Standardized Processes to Recruit, Hire, and Train Air Traffic Controllers

FAA uses a process based on an applicant’s score on a standardized aptitude assessment (Track 1) or prior experience as an air traffic controller (Track 2) to select new air traffic controllers. An overview of the two processes FAA uses to recruit, hire, and train these new controllers is depicted in figure 4. As the figure shows, Track 1 applicants must pass a skills assessment test, and applicants from both tracks must attend classroom training.

Recruiting

When FAA determines a need for air traffic control hiring, it recruits by posting Track 1 and 2 vacancy announcements to USAJobs.gov. FAA advertises the announcement on its website, through social media, and through outreach to CTI schools. Typically, FAA posts one or two Track 1 announcements each year that are open for a limited number of days. On average, the agency receives around 18,500 Track 1 applications to each posting, according to our analysis of application data for fiscal years 2015 through 2023. FAA also posts a single Track 2 announcement each year that it leaves open continuously. FAA received 623 Track 2 applications in fiscal year 2023, a decline of around 71 percent since 2019. Because FAA provides initial air traffic control training for Track 1 applicants, officials told us they can increase the number of controllers produced by the Track 1 process by choosing to hire more applicants. Conversely, the officials told us that, while they have some ability to influence the number of Track 2 applications, they do not control the number of people with the necessary experience to apply to the Track 2 process because those people receive their initial controller training elsewhere.

Hiring

FAA screens applications to determine whether applicants are qualified. The qualifications for each hiring track are summarized in table 1.

Table 1: Selected FAA Hiring Qualifications for Air Traffic Controllers With Limited or No Prior Experience (Track 1) Versus Experience (Track 2)

|

Hiring process step |

Track 1 (limited or no experience) |

Track 2 (experienced) |

|

Basic qualification |

U.S. citizen Fluent in English |

U.S. citizen Fluent in English |

|

Maximum age to apply |

30 |

35 |

|

Required air traffic control experience |

None |

52 or more consecutive weeks, which may be from work at a military air traffic control facility or an FAA Contract Tower |

|

Other requirements |

One year of work experience, a bachelor’s degree, or a combination of work experience and education |

Prior air traffic control experience must be within the last 5 years |

Source: GAO representation of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) information. | GAO‑26‑107320

FAA invites Track 1 applicants who meet the qualifications to take an aptitude assessment that, according to FAA, is designed to predict success as an air traffic controller. Specifically, FAA assesses Track 1 candidates through the Air Traffic Control Specialist Skills Assessment Battery (ATSA), a set of tests that measure cognitive abilities and personal abilities, including mathematical ability, decision-making, spatial comprehension, memory, planning, and other abilities. FAA places candidates into qualification bands based on their scores and generally selects all candidates who receive a Well Qualified or above on the ATSA to move forward in the process and receive a tentative offer.[15] FAA officials told us they seek to hire all Track 2 candidates that meet the qualifications, and the agency typically extends tentative Track 2 offers to all candidates with sufficient experience.

Once Track 1 and 2 candidates receive and accept their tentative offers, FAA uses a standardized series of steps for both Track 1 and Track 2 candidates to assess whether they meet the medical and security standards to be air traffic controllers. FAA officials told us that Track 2 candidates are more likely to have prior medical or security evaluations, such as from military service, and may be able to bypass some steps. See table 2 for a summary of the steps involved in the medical clearance and security approval processes.

|

Medical |

Security |

|

· Written medical history · Physical examination, including color vision test and electrocardiogram · Drug test · Psychological screening using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) · Further psychological evaluation, if necessary, based on results of the MMPI-2 |

· Fingerprinting · Background Investigation (including implications of drug test results) |

Source: GAO representation of Federal Aviation Administration information. | GAO‑26‑107320

Medical. FAA evaluates candidates for any health issues that could pose a hazard in the conduct of air traffic control duties, such as hearing loss or convulsive disorders. To identify any disqualifying psychological conditions, FAA evaluates candidates using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2). Candidates who do not meet the MMPI-2 criteria must undergo a further psychological evaluation.[16] FAA officials told us that mental health issues and substance abuse are the most common reasons for medical disqualifications.

Security. FAA evaluates candidates for the required level of character and conduct to work as an air traffic controller.[17] FAA examines a candidate’s criminal record and credit report and checks for, among other things, indications of alcohol abuse, drug use, or workplace misconduct. FAA officials told us that most applicants are eligible to receive a waiver, allowing them to be hired and start training before the full background investigation is complete. These officials told us that the most common reasons for applicants being disqualified on security reasons are financial issues and recent cannabis use.

According to FAA officials, the amount of time it takes for candidates to receive their medical clearance and security hiring approval can vary significantly based on candidate responsiveness and individual circumstances. FAA sends applicants who receive both medical clearance and security approval a final offer. Applicants who accept the final offer are formally hired and become trainee controllers.

Training

FAA officials told us they assign Track 1 applicants who accept a final offer to the next available academy class. All academy students take a 19-day classroom course that covers the fundamentals of flight, weather, and air traffic procedures, among other topics. Students who score 70 percent or higher on a test at the end of this introductory course go on to take one of three courses, which can take 37 to 66 days to complete, depending on the course. FAA officials told us they assign a majority of Track 1 hires to en route academy courses. See table 3 for a summary of the different academy courses.

|

Course Title |

Percentage of total students enrolled, fiscal year 2024 |

Length (days) |

Course elements |

Prepares students for work at |

|

En route |

59 |

59 |

Academics Classroom exercises En route radar simulation |

En route centers |

|

Tower |

38 |

37 |

Academics Tabletop exercises Tower simulation |

Terminal facilities |

|

Ten, Eleven, Twelve Radar Assessmenta |

3 |

66 |

Academics Terminal radar simulation Terminal radar approach control simulation |

New York Terminal Radar Approach Control facility (course is specialized for one specific facility) |

Source: GAO representation of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) information. | GAO‑25‑107320

aFAA assigns air traffic control facilities a

level based on their complexity. The Ten, Eleven, and Twelve in this course

title refers to the highest-level facilities. At present, according to FAA

officials, this course is only used for trainees whom FAA will assign to the

New York Terminal Radar Approach Control facility.

Students who score a 70 percent or higher overall grade graduate, and FAA assigns them to a facility of the same type as the academy course they took. Officials told us that they generally assign Track 2 hires, who most often do not attend the academy, to terminal facilities because most of these individuals have prior experience at that type of facility.

When trainees arrive at their assigned facilities, they take on-the-job training that is specific to the facility and its airspace, generally involving classroom and simulator exercises. Then trainees begin live training, which involves working a controller position under the supervision of an experienced controller. As trainees demonstrate mastery of specific positions, they are certified to work those positions without supervision. Once a trainee is certified on all the positions at a facility, they are considered a fully certified controller.[18]

FAA Faces Challenges Recruiting, Hiring, and Training New Controllers and Has Taken Steps to Improve Its Processes

Stakeholders and FAA Officials Identified a Need for More Qualified Applicants; FAA Has Taken Steps to Increase Recruitment

FAA officials and industry stakeholders told us that recruiting more people to apply for controller positions is important to addressing staffing challenges. However, stakeholders and FAA officials told us that there is continued limited awareness of the air traffic controlling profession outside of people already connected to the aviation industry, and FAA’s recruiting efforts may not be reaching enough qualified candidates to apply for Track 1 positions (see fig. 5).

FAA officials told us that, in response, they have taken steps to recruit more

people to apply for Track 1 controller positions:

· Expanding use of social media. FAA officials told us they have expanded their use of social media advertising to recruit applicants who are not familiar with the air traffic control profession. For example, between March 2024 and March 2025, FAA made 213 social media posts across different platforms, which were seen by about 8.5 million people.

· Providing more information to potential applicants. FAA officials told us that in 2024 they hosted two live help sessions for potential Track 1 applicants. These sessions were held both in person and virtually, to help prospective controllers fill out the application correctly. Officials said about 500 people attended in person, and about 1,000 attended online. According to FAA, applicants who attended these events were more likely to pass the initial screening step.

According to officials, FAA has also made the following changes to make it easier to apply, once recruited:

· Extending application windows. In 2023, FAA adjusted the hiring announcement for Track 2 applicants to keep it open all year, instead of during limited periods. The intent of this change is to make the process more accessible to current non-FAA controllers and to accommodate individuals leaving military service throughout the year.

·

Modifying required work experience. For the hiring

announcement conducted in fall 2024, FAA changed the work experience

requirement for Track 1 applicants to be a college degree, or 1 year of general

work experience, as opposed to a college degree, or 3 years of general work

experience. FAA officials told us that most work experience that applicants

have is not relevant to air traffic controlling and that a longer work

experience requirement may have been eliminating people who have the aptitude

to be successful controllers. In addition, they said that this change may allow

them to build ties with high schools to promote air traffic controlling as a

vocational pathway.

Stakeholders and FAA Officials Identified Attrition During Hiring and Training as a Challenge

FAA officials and industry stakeholders identified attrition during the controller hiring and training processes as a challenge to improving staffing of the air traffic control system. This is particularly true for Track 1 applicants who, as described above, must complete more steps before being hired. According to FAA officials, it can take 2 to 6 years for Track 1 applicants to go from applying to being fully certified. Our analysis of FAA’s data found that, of the applicants we were able to follow through the hiring and training processes, about 4 percent of those who applied for a Track 1 hiring announcement between fiscal years 2017 and 2022 completed all of the hiring steps and began training at the FAA Academy.[19] For an overview of how many applicants leave the process at different stages, see figure 6.

Figure 6: Analysis of Applicants for Air Traffic Controller Positions in Fiscal Years 2017-2022 That Completed Key Steps in the Hiring and Training Processes

Note: The Air Traffic Control Specialist Skills Assessment Battery is a series of tests that FAA uses to sort candidates into hiring qualification bands. The tests are designed to measure cognitive abilities and personal abilities, including mathematical ability, decision-making, spatial comprehension, memory, planning, and other abilities.

Hiring

After individuals apply for an air traffic control position, FAA’s processes for hiring controllers result in substantial attrition of potentially qualified applicants. According to our analysis of FAA application and training data, of the applicants we were able to track through the hiring and training processes, most left the hiring process at the ATSA stage, either because they did not take the test or because they did not meet the minimum score requirements. For the candidates in our analysis whom FAA invited to take the ATSA between fiscal years 2017 and 2022, about 62 percent did not take the ATSA, and 32 percent who did take the test were removed from the process based on their score (see figure 7).

While FAA officials told us that the rates of attrition are substantial because only a limited portion of the population has the skills and aptitude needed to perform the job, we found that attrition is also notable even for stages that do not involve an applicant’s qualifications or aptitude. According to our analysis of FAA data, between fiscal years 2017 and 2022, about 7 percent of Track 1 applicants who scored sufficiently high on the ATSA to receive a tentative offer did not accept the offer. Similarly, about 14 percent of Track 1 applicants who received a final offer—which means they completed all the requirements necessary to receive a medical clearance and security approval—did not accept the offer. FAA officials and stakeholders told us that this attrition can result from the length of the hiring process. For example, candidates may have found another job, or their life circumstances may have changed to make relocating on short notice to work in air traffic control difficult.

In addition to the length of the process, stakeholders also told us that some parts of the hiring process are difficult for applicants to navigate. For example, the hiring process requires applicants to schedule a series of in-person appointments for medical screenings, fingerprinting, and other requirements. According to the FAA Academy students with whom we spoke, they are sometimes asked to provide detailed information on short notice, with little warning.

FAA officials, FAA Academy students, and two out of five industry stakeholders identified the medical clearance process as a challenge. They told us this process is both the most substantial cause of delay in the entire air traffic controller hiring process and a substantial source of applicant attrition. For example, FAA officials told us that the percentage of applicants that need a further psychological evaluation has increased in recent years. These officials attributed the increase to the American public’s changing mental health. In recent years, these evaluations have taken on average more than 2 years to process. FAA officials told us that a substantial proportion of candidates are waiting to clear this hurdle.

The delays in the medical clearance process have created a backlog, which FAA is working to address. According to FAA data, of the about 2,600 candidates in the pipeline as of August 2024, about 1,200 of them were in the further psychological evaluation process. FAA officials told us that they increased the rate at which they were processing evaluations by streamlining the review process and adding more staff to support the reviews. By June 2025, about 1,000 candidates were awaiting a further psychological evaluation, even though the total number of candidates in the pipeline had increased to around 4,600.

Training

A large portion of air traffic control trainees also leave the process during training. Our analysis of FAA’s data found that between fiscal years 2017 and 2022, about 43 percent of Track 1 applicants who started training at the academy were no longer controllers or in training as of 2024 (see figure 8).

FAA officials told us that trainees may fail to complete training or decide that they are not well suited for the profession. For example, FAA officials and three out of seven stakeholders said that trainee controllers may struggle and leave the program when they are assigned to conduct on-the-job training at facilities in locations where they do not have personal support networks. This can lead to them failing to complete training, or resigning. According to FAA, losing trainees at this step is costly for the agency because it has already invested substantial resources in evaluating and training candidates.

In addition, FAA officials told us that training capacity limitations may prevent applicants from moving forward on schedule. FAA officials and four out of five industry stakeholders told us that FAA has had difficulties ensuring that its academy and facilities have sufficient training capacity, generally with regard to instructors and simulators.[20] FAA officials told us these capacity limitations reduce the number of controllers that can be successfully trained at one time and cause training to take longer to complete. A stakeholder told us that training delays can also cause dissatisfaction in trainees, as pay increases are tied to progress toward certification.

FAA Has Modified Its Processes for Hiring and Training to Address Attrition

In May 2025, FAA announced a “Brand New Air Traffic Control System” initiative to coincide with its efforts to increase hiring of new air traffic controllers, which it described as a “Supercharge.” Officials described several changes to individual aspects of the processes to shorten the process and reduce candidate attrition during hiring and training. According to officials, FAA generally focused these changes on the Track 1 processes because these are the source of most of its new controller hires.

Hiring

FAA officials told us that they have taken steps to address attrition during the hiring process, both by shortening the process and by making it easier for candidates.

· Continuous processing. For its spring 2025 Track 1 announcement, FAA changed how it processes applicants overall, leading to a continuous flow of applicants through the hiring process rather than sequential processing of the entire group of applicants from a hiring announcement. FAA officials told us that this has allowed some candidates to move through the process much faster than in the past.

· Increased automation. FAA has automated some of the qualification checks, such as prior work experience, that were previously done by hand as part of a 6-to-8-week process.

· Hosting preemployment processing events. Starting in 2023, FAA began hosting preemployment processing events. These allow applicants to complete many of the in-person hiring process steps, such as fingerprinting, at one time and place, with FAA staff on hand to assist, making the process more efficient. FAA officials said that this helps applicants avoid having to schedule multiple visits to complete these steps.

· More scheduling flexibility. FAA officials told us they have taken steps to encourage more applicants to take the ATSA by providing more flexibility with regard to scheduling the test and following up with applicants. FAA is also refreshing the ATSA to ensure its air traffic control preemployment test remains a valuable tool for selecting candidates likely to succeed. Officials told us they plan to have the new test ready in 2026.[21]

· Medical clearance process. FAA has made progress toward reducing the medical clearance backlog by increasing the rate at which it reimburses providers for these assessments to better match market rates and increase provider participation, streamlining their internal process for reviewing these assessments, and adding additional staff to assist with scheduling. FAA officials stated that the wait time for these evaluations remains a problem and that they continue to work to reduce it further.

· Specialization flexibility. FAA officials told us that some Track 1 applicants who receive a final offer inform FAA that they are declining the offer because they are dissatisfied with their assigned academy class—either en route or terminal. In June 2025, FAA implemented a policy that allows those applicants a limited opportunity to place in the other track, should an academy seat become available.

Training

FAA officials at the academy and facilities told us that in most cases they have sufficient resources to train the rate of trainees they currently receive but that substantially increasing the number of trainees all at once, as is called for in the current Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan, could strain their resources. For example, FAA officials told us that some parts of the academy training process must be overseen by current controllers. These officials noted that, given current staffing shortages, facilities may be reluctant to give up experienced personnel to train at the academy.

To reduce pressure on academy training capacity, FAA has developed, and is in the process of implementing, the Enhanced-Collegiate Training Initiative program. This program allows students who complete an FAA-approved air traffic control curriculum as part of a college degree, if hired by FAA, to be placed directly at a facility and begin on-the-job training without attending the academy. FAA approved the first school to offer this program in October 2024 and, as of September 2025, has approved a total of nine schools.[22] FAA officials told us that they only expect to receive a small number of students from this program initially but, over a number of years, they expect the program to help provide substantial numbers of new trainees directly to facilities to meet FAA hiring goals.

To help alleviate the issue with too many trainees being placed in locations where they do not have personal support networks, in June 2024 FAA changed its training process by expanding the list of facilities that academy graduates can choose from when selecting their first assignment. FAA officials told us that it is too soon to see if this change improves trainee retention but that trainers at facilities have reported that it has improved trainee morale and engagement. FAA has taken similar steps regarding Track 2 applicants by expanding the list of facilities offered to them and using on-the-spot hiring authority to create opportunities for experienced controllers with local experience to apply directly to specific facilities.[23]

FAA Could Improve Communication With Applicants

While FAA is taking steps to reduce applicant attrition, issues related to communication with applicants during the hiring process may affect its ability to hire qualified applicants. Both students at the academy and FAA human resources officials told us that limitations in how FAA communicates with applicants cause unnecessary difficulties during the hiring process. Students that we spoke with said that is often challenging to determine their application status when applying for air traffic controller positions. They further explained that applicants are asked to provide information, such as extensive medical histories that may be difficult to collect quickly, within several days after an extended period with no updates from FAA. FAA officials said that limitations in the tools available to them to track information on applicants results in a substantial burden on FAA human resources staff. The officials stated that the staff spend about 2 hours every workday responding to applicant queries, many of which could be answered more efficiently through an automated system.

FAA officials told us that applicants seeking detailed status updates and information on next steps during the hiring process must contact human resources staff directly. However, the students we spoke with told us that they often had difficulty finding the right person to contact at FAA due to changes in staff and different people being responsible for different parts of the process. They also said that human resources staff they contacted often could not provide detailed, timely information, such as current contact information for medical providers for essential parts of the screening process. Many of the students said they found more useful information about how to navigate the hiring process on third-party social media than from official sources. FAA officials told us that the information immediately available to human resources staff about candidates is limited and, in many cases, the staff must contact another FAA office to respond to detailed questions. The officials stated that key information on applicants being stored in different databases creates difficulties for human resources staff, especially in the context of efforts to increase controller hiring.

FAA’s 2022-2026 strategic plan states that FAA will restructure its recruiting and hiring process by, among other things, engaging in effective internal and external communication related to hiring.[24] In addition, internal control principles state that the agency should communicate quality information externally to achieve its objectives, which includes hiring qualified candidates. The agency should maintain open, two-way reporting lines to facilitate this communication and should consider factors, including availability—making sure the information is readily available to the audience when needed—and cost—the resources used to communicate the information—in selecting appropriate methods of communication.[25]

FAA officials told us they do not provide applicants with a way to check their own status because FAA is not able to easily track this information across the different data systems it uses in the hiring process. Officials told us that they are seeking to address this issue by developing a “dashboard” where applicants can check their own status in the hiring process, which they told us they intend to have available in fiscal year 2026. However, as of April 2025, FAA did not have an estimated start time for tasks such as creating an external applicant status portal and determining dashboard requirements. In the interim, FAA officials told us that they will use applicant Social Security numbers as a common identifier between different systems.[26] According to FAA, this will make it faster for human resources staff to find information applicants need, though applicants will still need to work with FAA to check their status. As a result, this interim solution does not address applicant concerns about their difficulty in finding the correct point of contact or FAA human resources staff having outdated information.

Absent a system that efficiently communicates accurate, timely information to applicants about their status, applicants may not have the information they need to complete the steps necessary to advance through the hiring process, and otherwise qualified applicants may become frustrated and leave the process entirely due to the lengthy wait times and complex processes. In addition, responding to applicant questions takes FAA human resources staff away from processing other applications. According to FAA officials, this impacts FAA’s overall ability to process applications in a timely manner, which may add unnecessarily to the length of the hiring process and limit the number of candidates it can hire. By implementing a system, such as a unified dashboard that allows applicants to access the quality information they need, FAA could both address applicant complaints about the hiring process and allow its human resources personnel to focus on core functions, such as processing controller applications.

FAA Does Not Fully or Consistently Assess Its Efforts to Recruit, Hire, and Train New Air Traffic Controllers

While FAA has made changes to hire more controllers, it does not fully or consistently assess these efforts to inform its overall hiring process. Our prior work has shown that performance management activities help an organization define what it is trying to achieve, determine how well it is performing, identify what it could do to improve results, and foster a culture of continuous improvement.[27] We found that while FAA has some broad performance goals, it does not define goals for its key efforts and, therefore, cannot fully or consistently evaluate them. Nor has it consistently used the information it does collect on recruiting, hiring, and training controllers to assess its efforts and inform its decision-making.

FAA Lacks Performance Goals for Recruiting, Hiring, and Training Air Traffic Controllers

Our prior work has identified defining measurable performance goals that specify an organization’s objectives as an important step for assessing the performance of all agency activities.[28] FAA has set a quantifiable performance goal for only one of its processes: the number of new controllers it hires each year. FAA states this goal in its annual Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan based on its goals for the number of controllers that should be staffed at each facility, as determined by its two staffing models and FAA’s estimation of that year’s controller retirements and other attrition.[29]

FAA has not set performance goals for other areas, such as the following:

· average time to provide on-the-job training: Prior to 2025, FAA published in the Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan a goal for the average amount of time for on-the-job training of new controllers at facilities based on each facility’s traffic level. FAA, however, did not include this goal in the version of the Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan published in July 2025;

· recruiting. According to FAA officials, the agency does not have an overall goal for how many potential qualified potential applicants it needs to recruit to ensure it has adequate controller staffing. For example, officials said that while FAA has an overall hiring goal, it has not set performance goals for how many recruited applicants begin the hiring process by signing up for, and taking, the ATSA test. This type of goal could help ensure that enough applicants pass the test and can be hired; and

· attrition during the hiring process. FAA has not set an overall performance goal related to its primary challenge—attrition during the hiring process. FAA officials stressed to us the importance of limiting attrition because each candidate that leaves without becoming a certified controller requires FAA to start over, expending additional resources and, potentially, years of time. In addition, officials said that when certain parts of the process become overloaded with applicants, wait times can increase, which slows down the entire process.

FAA officials told us that, in lieu of these kinds of performance goals, it is the agency’s practice to rely on historical trends in applications, attrition rates, and time frames at each key step in the hiring process. However, relying on past results, rather than setting performance goals for its key steps, is not a performance-based approach. For example, officials said that, based on past results, they expect 10-12 percent of Track 1 applicants to eventually attend the FAA Academy. However, our analysis of FAA data found that for the records we included in our analysis, these trends were not reliable for making predictions, because they varied substantially in recent years. For example:

· The percentage of Track 1 applicants from a given year that eventually attended the FAA Academy varied from a high of about 7 percent for 2019 applicants to a low of around 2 percent for 2022 applicants.

· The number of applications varied by year, ranging from a low of around 7,000 in 2018 to a high of around 60,000 in 2022 before returning to around 13,000 in 2023 and 2024.[30]

By not setting performance goals for key steps in its processes for recruiting, hiring, and training air traffic controllers, FAA does not know how well these processes are performing and whether they should be improved. For example, our analysis of FAA data found that while many applicants that cleared the initial psychological evaluation without requiring a further psychological evaluation were able to complete the process within 1 or 2 months, the average time to complete the medical clearance step for all applicants varied from 4 to 8 months between 2017 and 2022; however, FAA did not make major changes to the process until 2024. Without a goal for the amount of time the medical clearance steps should take, and efforts to manage the agency’s performance toward achieving the goal, FAA may have missed opportunities to improve that process sooner and prevent some unnecessary attrition.

Moreover, without aspirational performance goals for key steps, FAA cannot focus on what it is trying to achieve at various key steps in the process. Our prior work has shown that goals guide an organization’s activities and allow assessing performance by comparing planned and actual results.[31] By striving for measurable performance goals for key steps, rather than relying on historical trends, FAA can provide an expectation and framework for future focus and improvement.

FAA Collects Data on Controller Applicants and Trainees but Does Not Consistently Use It to Assess Its Efforts and Inform Its Decision-Making

While FAA collects data on applicants and trainees, it has not consistently used the data to measure its performance and inform decision-making about how to optimize its processes for hiring controllers. This is inconsistent with key practices we have identified in our prior work, which describe using evidence collected to measure progress against organizational goals to inform management decisions on a continuous basis.[32] Evidence can be used to, among other things, identify priorities, allocate resources, identify issues and corrective actions, and coordinate efforts across organizational levels.

FAA operates three data systems that track information about controller applicants and trainees:

· the Automated Vacancy Information Access Tool for Online Referral that tracks information from application through the screening and clearance steps;

· the Federal Personnel and Payroll System that FAA uses to, among other things, track applicant employment status from the FAA Academy; and

· the National Training Database that tracks on-the-job training.[33]

However, these three data systems do not communicate with one another and lack a common identifier that would allow FAA to reliably track individuals across each of these systems. As a result, officials said that FAA has not been able to use the information it has to evaluate its processes, from recruiting prospective controllers; to processing applications; through hiring and tracking performance at the FAA academy and on-the-job training; and ultimately, certification as a controller. FAA officials told us that they have considered analyzing qualifications such as ATSA scores and CTI school attendance compared with controller certification, but they have been unable to do so because of these limitations.

According to FAA officials, the agency may alleviate this issue by using the same common identifier (Social Security numbers) that they use across their databases to provide applicants with status updates. They said that this effort may allow them to use the evidence they already collect—for example, on ATSA scores and key process dates—to conduct some assessments of various aspects of the controller hiring process. However, FAA did not provide any specific plans to conduct these assessments. Using its data to comprehensively evaluate the performance of FAA’s process to recruit, hire, and train new controllers against its goals could help FAA make decisions about what changes would have the greatest impact on improving controller staffing.

For example, our analyses compiling existing data from across FAA’s three databases provide an example of information that could help FAA to assess and improve its efforts to hire additional controllers by better understanding the attrition it faces.[34] We calculated attrition rates for individuals in our analysis that received a tentative offer and who applied between fiscal years 2017 and 2022 at key steps in FAA’s hiring and training processes based on their ATSA scores and whether they attended a CTI school.[35] We found that individuals we included in our analysis who scored above an 85 on the ATSA became certified controllers or were still in training in 2022 at higher rates (29 percent) than those who scored below 85 (9 percent for those scoring from 80 to 84.9).

This is also true of individuals in our analysis who attended a CTI school, 41 percent of whom were still in training or certified in 2022, as opposed to 22 percent of those who did not (see table 4). As discussed above, CTI graduates tend to have more previous exposure to the air traffic control profession than applicants from the general public and may have a greater understanding of the hiring and training process, which could lead to lower attrition rates at certain steps. Understanding where and how these differences manifest themselves could help FAA improve attrition rates for qualified applicants from the general public which, as discussed above, is the largest group of applicants for the Track 1 hiring process.

In addition, we analyzed qualified applicants from different demographic groups who received an offer and found that different groups left the process at different rates. Specifically, we found that 88 percent of male applicants we included in our analysis who had completed the security and medical screening steps began training at the FAA academy, as opposed to 78 percent of female applicants. At the same step, we found that 72 percent of candidates we included in our analysis who had passed the required screenings and identified as “Black or African American” began training at the FAA academy, while 89 percent of candidates who identified as “White” did so (see app. II for more information). Better understanding these discrepancies through analysis of its existing data could help FAA develop actions to keep otherwise qualified applicants on the path to becoming certified controllers (see table 4).

Table 4: Analysis of Key Steps in the Air Traffic Controller Hiring Process, Fiscal Years 2017-2022, by Test Score and Attendance at a Collegiate Training Initiative Program

|

Applicant characteristic |

Tentative offer provided |

Tentative offer accepted |

Completed medical and security screening |

Started at FAA Training Academy |

Completed FAA Training Academy |

Achieved certification or still in on-the-job traininga |

Percent of individuals that received tentative offer that achieved certification |

|

Number of Individuals (percent attrition at that step) |

|||||||

|

Total |

9,107 |

8,442 (-7%) |

4,619 (-45%) |

3,964 (-13%) |

2,610 (-34%) |

2,258 (-14%) |

25% |

|

Air Traffic Skills Assessment score rangeb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

70-79.9 |

238 |

219 (-8%) |

56 (-75%) |

46 (-18%) |

25 (-46%) |

18 (-28%) |

8% |

|

80-84.9 |

1,555 |

1,455 (-6%) |

563 (-61%) |

307 (-45%) |

176 (-42%) |

137 (-23%) |

9% |

|

85-89.9 |

2,873 |

2,617 (-9%) |

1,470 (-44%) |

1,305 (-11%) |

834 (-36%) |

734 (-12%) |

26% |

|

90-94.9 |

2,223 |

2,078 (-7%) |

1,279 (-38%) |

1,159 (-9%) |

757 (-35%) |

653 (-14%) |

29% |

|

95.0-99.9 |

1,204 |

1,118 (-7%) |

675 (-40%) |

621 (-8%) |

440 (-29%) |

381 (-14%) |

32% |

|

100 |

998 |

940 (-6%) |

572 (-39%) |

522 (-9%) |

371 (-29%) |

332 (-10%) |

33% |

|

Attended Collegiate Training Initiative schoolc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

1,436 |

1,384 (-4%) |

1,006 (-27%) |

914 (-10%) |

695 (-24%) |

593 (-15%) |

41% |

|

No |

7,671 |

7,058 (-8%) |

3,613 (-49%) |

3,050 (-16%) |

1,915 (-37%) |

1,665 (-13%) |

22% |

Source: GAO Analysis of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) data. | GAO‑26‑107320

Notes: This table includes only individuals hired through FAA’s process for hiring individuals without previous experience as an air traffic controller, known as the “Track 1” process.

We excluded from our analysis 233 records because we determined the records were not reliable. For example, we could not identify matching training and application records in many cases. We also identified 338 other records that were missing information about the applicant’s medical clearance, security approval, or both. However, these records included information about qualifications and training, so we included them in our analysis. Because of these discrepancies, these results should be viewed as an illustrative example and not an exact accounting of each individual who applied for an air traffic control position in those years.

aIncludes all trainees who had achieved certification or had on-the-job training still in progress as of September 30, 2023, and all trainees who began on-the-job training between October 1, 2023, and June 15, 2024.

bScores on the Air Traffic Skills Assessment test administered by FAA to measure the aptitude of applicants to air traffic control positions that do not have at least 1 year of air traffic control experience. During this time, FAA used different score thresholds to define the applicant qualification bands.

cApplicants who reported on their application that they had attended a Collegiate Training Initiative school (CTI). CTI graduates tend to have more previous exposure to the air traffic control profession than applicants from the general public and may have a greater understanding of the hiring and training process, which could lead to lower attrition rates at certain steps.

Conclusions

Hiring enough air traffic controllers is essential for aviation safety; however, it is also a complex, time-consuming, and resource-intensive effort for both FAA and applicants. The events of the past decade—including the COVID-19 pandemic—made it even more difficult to hire and retain controllers. Nevertheless, FAA has taken steps to address both the challenges it faces in recruiting applicants and the attrition it experiences during the long hiring and training processes. However, FAA has not set plans for the key developments needed to improve its communication with applicants, and applicants remain unable to check for themselves where they are in the hiring process and, crucially, what they need to do next. Further, FAA collects a range of data on applicants and trainees but does not have specific plans to use the data to measure and assess results. Analyzing the performance of the key steps in its hiring and training processes would help FAA more fully understand why many applicants and trainees do not complete the process and become certified controllers. Finally, without measurable goals, FAA cannot use the data it collects to determine where to invest resources to make the process more efficient and help ensure that as many qualified controllers as possible complete the process. As FAA works to “supercharge” its hiring to tackle its staffing shortfalls, setting goals and measuring progress toward achieving them will be especially important to understand which parts of its processes are working and which could be further improved.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to FAA:

The Administrator of FAA should ensure that FAA develops a system, such as its planned dashboard for applicants, that provides applicants with the ability to efficiently access information related to their application, including the ability to check their application status and obtain the information they need to complete their next steps. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of FAA should establish and document measurable goals for its processes to recruit, hire, and train air traffic controllers. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of FAA should use the information FAA collects across its databases to assess its processes for recruiting, hiring, and training air traffic controllers and inform decisions about any needed improvements. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this product to the Department of Transportation for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, the Department of Transportation concurred with our recommendations and stated it will provide a detailed response to each recommendation within 180 days of the report’s issuance. The department also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions concerning this report, please contact me at VonAha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Sincerely,

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure

This report (1) describes the size and composition of the air traffic control workforce and the extent to which these characteristics have changed since fiscal year 2015; (2) describes the processes the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) uses to recruit, hire, and train new air traffic controllers; (3) examines the steps FAA has taken to address challenges associated with recruiting, hiring, and training air traffic controllers; and (4) evaluates how FAA has assessed its efforts to achieve a fully staffed air traffic controller workforce.

To obtain information for all objectives, we reviewed laws, regulations, and presidential memorandums covering air traffic control and the hiring of new controllers. We also obtained data from FAA on air traffic control applicants and trainees from 2014 through 2024. FAA provided information on applicants from its Automated Vacancy Information Access Tool for Online Referral, which it uses to track individuals from application through preemployment screening. For information on training, FAA provided lists of entrants, graduates, and separations from the FAA Academy from the Federal Personnel and Payroll System that it uses to track the status of its employees. For information on on-the-job training, FAA provided information on duty station and training progress from the National Training Database that it uses to track initial training for air traffic controllers. We assessed the reliability of these data by reviewing documentation; interviewing FAA officials; electronically testing the data by, for example, examining missing values and outliers; and verifying the accuracy of potentially erroneous data with officials. We concluded that the data were reliable for the purposes of describing the number of individuals who completed the various steps in the controller hiring and training processes and describing some of those individuals’ qualifications. These qualifications include attendance at a Collegiate Training Initiative (CTI) program and score on the Air Traffic Control Specialist Skills Assessment Battery (ATSA) and demographic characteristics, including race and gender.

The information FAA provided from the three datasets was not linked in a way that allowed us to measure an individual’s progress through the hiring and training process from application through certification as an air traffic controller. Due to the absence of a comprehensive dataset, we compiled a merged dataset that enabled us to track individual applicants in order to describe the composition of FAA’s controller workforce and to evaluate how FAA assesses its efforts to recruit, hire, and train new controllers. Because FAA gets a large majority of its new trainees from the pathway for applicants without previous experience as an air traffic controller (Track 1), we focused our efforts to compile a single dataset on this group of applicants. In addition, FAA made substantial changes to its hiring process between 2014 and 2016, so we limited our efforts to merge the datasets to applicants who applied in fiscal years 2017 through 2024. This group represented 132,152 applications. Because the training process for air traffic controllers can take several years to complete, we limited our analysis to individuals who applied between 2017 and 2022, regardless of when they completed their training. This final group represented 106,533 applications.

To link these datasets together, we matched FAA records from the Federal Personnel and Payroll System and FAA’s National Training Database using a unique identifier, the Employee Common Identifier, that FAA uses for employees after they have begun work at the agency. Merging these datasets created a single record of an employee’s status through the training process, including the date at which they began training at the FAA Academy; the date they either completed the academy or separated from FAA before completion; the date they began on-the-job training and the facility where they did so; the date they completed on-the-job training; and, for those employees who did not complete on-the-job training, the reasons why they did not complete it. This step created training records for 5,650 individuals who began training at the FAA Academy after FAA posted the 2017 hiring announcement until the end of the dataset in 2024.

To merge the training record with data on an individual’s initial application from FAA’s Automated Vacancy Information Access Tool for Online Referral dataset, we used the employee’s name as a matching instrument. Because many individuals applied for air traffic control positions multiple times, we matched training records to application records to create a single record of each attempt for employment as an air traffic controller. Because many applicants had similar names, we only automatically matched records that had exact name matches from complete training records to complete application records. We reviewed the remaining training records manually to identify the correct application record to match them to based on name spellings, punctuation, name changes, and other factors. Merging these datasets created a single record of an individual’s attempt to become employed as an air traffic controller, including, along with the training information described above, the vacancy announcement they applied to, the CTI school they attended (if any), the date FAA approved them to take the ATSA and the score they received, the date FAA provided them with a tentative offer, and the date they received medical clearance and security approval.

To ensure that each training record matched correctly to the corresponding application record, we checked key dates, applicant names, and overall record completeness. We examined any potentially mismatched records to determine whether they were correctly matched to the appropriate application record. In all instances where we matched records by hand, a GAO analyst reviewed the records to ensure that the records were correct, including the applicant’s name, the steps the application records indicated the applicant had completed, and the order of the dates in the different records. To ensure accuracy, a second GAO analyst reviewed the first analyst’s coding records, and then the two analysts reconciled any discrepancies.

After completing these steps, we excluded 1,453 records of individuals who began training at the FAA Academy after July 2017 but who applied outside of the years 2017 through 2022. In addition, we excluded 215 records of individuals who began training at the FAA Academy during our time frame that we could not match to an application record, and 18 records for other reasons, such as an individual having starting training more than once. This left us with 3,964 records that included training information. In addition, we found five records that were missing a medical clearance date, 54 records that were missing a security approval date, and 279 records that were missing both dates. We included these 338 records in our analysis because they included complete information about the rest of the hiring and training processes. Due to these limitations, this merged dataset should be viewed as an illustrative example and not an exact accounting of every individual who applied for an air traffic control vacancy.

To describe the size of the air traffic control workforce since 2015, we reviewed each of FAA’s annual Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plans published between 2016 and 2025 to obtain the total number of controllers FAA employed on the last day of fiscal years 2015 through 2024. To describe the number of flights handled by the air traffic control system in those years, we reviewed data FAA published in Air Traffic by the Numbers in May 2025 containing data up through the end of fiscal year 2024. For the number of flights, we totaled the number of Instrument Flight Rules and Visual Flight Rules flights handled by the air traffic control system in each year.