U.S. POSTAL SERVICE

Action Needed to Fix Unsustainable Business Model

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: David Marroni at MarroniD@gao.gov or Frank Todisco at TodiscoF@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

In 2021, the United States Postal Service (USPS) introduced a 10-year strategy designed to improve its poor financial condition while fulfilling its statutory mandates. USPS has taken many actions to try to increase revenue and reduce expenses since this strategy was introduced, such as increasing prices and redesigning its transportation network and processing operations. As part of its strategy, USPS also requested the federal government to take action. Congress partially fulfilled this request via the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022. This act canceled $57 billion of USPS’s missed payments, among other things.

However, USPS’s financial condition remains poor. While USPS has increased revenue, its total expenses continue to outpace total revenue leading to further losses (see fig.). In addition, USPS’s unfunded liabilities and debt have steadily increased since fiscal year 2022. USPS projects that if it made all its required payments toward its unfunded liabilities in full, it would run out of cash as early as fiscal year 2026. USPS updated its strategic plan in 2024, but this plan did not include financial projections showing how near-term results from the updated plan’s actions could increase revenue or reduce expenses. Without financial projections, USPS does not have targets to show progress or to effectively communicate how its actions will restore USPS’s financial sustainability.

USPS and Congress have a wide range of options to improve USPS’s financial condition. However, USPS’s actions alone will likely not be enough for it to become financially self-sufficient. GAO has previously recommended that Congress consider various options. Although Congress has taken some action, key issues remain unresolved. These include identifying a sustainable path for postal retiree health benefits and determining the level of postal service required, and the extent to which USPS should be financially self-sufficient.

Why GAO Did This Study

USPS has lost money almost every fiscal year since 2007, even though Congress created it to be financially self-sufficient. GAO has long reported that USPS’s business model is unsustainable, due to rising costs and lower mail volume. As a result, USPS’s financial viability has been on GAO’s High Risk list since 2009.

This report examines (1) recent USPS actions to improve its financial condition, (2) USPS’s current financial condition and the extent to which USPS projects its financial information, and (3) options that could improve USPS’s financial condition.

GAO reviewed USPS’s strategic plan, financial reports, reports to Congress, and other reports containing financial information; projected USPS’s retiree health care and pension liabilities; interviewed USPS and other relevant agency officials and stakeholders; assessed the financial information in USPS’s updated strategic plan against GAO’s principles of evidence-based policymaking and surveyed selected stakeholders on potential options to improve USPS’s financial condition. GAO selected stakeholders from its prior work and stakeholders’ public statements on postal issues.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that the Postmaster General should develop publicly available financial projections of revenue and expenses. USPS disagreed with the recommendation. GAO also reiterates that Congress should fully address the level of postal service the nation requires, the extent to which USPS should be self-sustaining, and a sustainable financial path for retiree health benefits.

Abbreviations

CSRS Civil Service Retirement System

DFA Delivering for America

FECA Federal Employees Compensation Act

FEHB Federal Employees Health Benefits

FERS Federal Employees Retirement System

OIG U.S. Postal Service Office of the Inspector General

OPM Office of Personnel Management

PAEA Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act

PRA Postal Reorganization Act

PRC Postal Regulatory Commission

PSRA Postal Service Reform Act of 2022

USPS U.S. Postal Service

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 16, 2025

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The U.S. Postal Service (USPS) has lost money almost every fiscal year since 2007, even though Congress created it to be financially self-sufficient.[1] We have reported that USPS’s business model is unsustainable, due to rising costs and lower mail volume. Accordingly, USPS’s financial viability has been on our High Risk list since 2009.[2] There is a fundamental tension between the level of service Congress expects and what revenue USPS can reasonably be expected to generate.

Both USPS and Congress have taken steps to try to make USPS financially self-sufficient again. USPS introduced the 10-year strategic plan in 2021, designed to restore USPS’s financial self-sufficiency. In addition, Congress passed the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022, which, among other things, provided USPS about $57 billion in noncash financial relief.[3] Despite these efforts, USPS cannot fully fund its current level of services and financial obligations as it continues to lose money—about $31 billion since fiscal year 2021.[4] These losses prevent USPS from addressing its large unfunded liabilities for pensions and retiree health care benefits, putting the taxpayer at increased risk of having to meet these liabilities for USPS.

We performed our work at the initiative of the Comptroller General as USPS financial viability has been on GAO’s High Risk List since 2009. This report examines: (1) recent USPS actions to improve its financial condition, (2) USPS’s current financial condition and the extent to which USPS projects its financial information, and (3) options that could improve USPS’s financial condition.

For all our objectives, we reviewed our prior work and reports from USPS, the USPS Office of the Inspector General (OIG), the Postal Regulatory Commission, and other organizations. We interviewed USPS, OIG, and Postal Regulatory Commission officials, as well as 12 postal stakeholders, including labor unions, an organization representing commercial mailers, a consultant to commercial mailers, and individuals with subject matter expertise.

To determine recent USPS actions to improve its financial condition, we reviewed USPS’s original 10-year strategic plan and most recent update.[5] We also reviewed USPS reports on actions taken under its strategic plan. We completed almost all of our audit work before USPS released its fiscal year 2025 financial results. We have included some financial information from fiscal year 2025 in this report.

To examine USPS’s current financial condition and the extent to which it projects its financial information, we reviewed and analyzed its financial reports, reports to Congress, and other reports that contained financial information. We also reviewed USPS’s revenue and expense projections in its original 10-year strategic plan, and USPS’s projections of its actuarial liabilities and assets for pension and retiree health care benefits, and documentation about these projections. We used Office of Personnel Management (OPM) data to project USPS’s pension and retiree health care liabilities, and USPS data from its annual financial reports to project USPS’s workers’ compensation liabilities. Furthermore, we assessed the extent to which USPS’s most recent updates to its strategic plan were consistent with GAO’s principles of evidence-based policymaking.[6]

To identify options that could improve USPS’s financial condition, we interviewed the stakeholders mentioned above on potential options available to USPS and Congress that could improve USPS’s financial sufficiency, as well as the benefits and challenges for each option. We selected options mentioned either by USPS or by more than one stakeholder and summarized these options. We analyzed USPS and stakeholder comments and utilized standard economic and actuarial principles to identify each selected option’s benefits and challenges. We also compared Congress’s actions against our four open matters concerning USPS to identify progress made on these matters.[7] For additional information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Prior to 1971, when USPS began operations, the Post Office Department was a cabinet-level government agency that received annual appropriations from Congress. The Post Office Department began to experience significant challenges in the 1960s, as inflation and mail volume grew. At that time, Congress made key management decisions, such as establishing wage levels and postage rates. However, the legislative process made it challenging for the Post Office Department to plan and finance operations to adapt to changing economic and demographic conditions. By the mid-1960s, the Post Office Department struggled with outdated equipment, crowded facilities, and underpaid workers, among other issues. On the advice of a Presidential Commission on Postal Organization, Congress and the Nixon administration established USPS as an independent establishment of the executive branch through the Postal Reorganization Act in 1970.[8]

While USPS was created to be financially self-sufficient, it must also meet costly requirements, including its universal service obligation and other mandates that private sector businesses do not have. USPS’s universal service obligation refers to several statutory provisions that require USPS to serve, as nearly as practicable, the entire U.S. population and to generally provide delivery at least 6 days a week.[9] These delivery locations include rural areas, communities, and small towns where post offices are not financially self-sufficient. In addition, USPS must pay to ship goods to remote locations in Alaska by private shipping companies, which cost USPS $133 million in 2022. Since fiscal year 2007, the number of delivery locations has increased while mail volume has decreased almost every year, which has increased the costs of universal service while decreasing revenue.

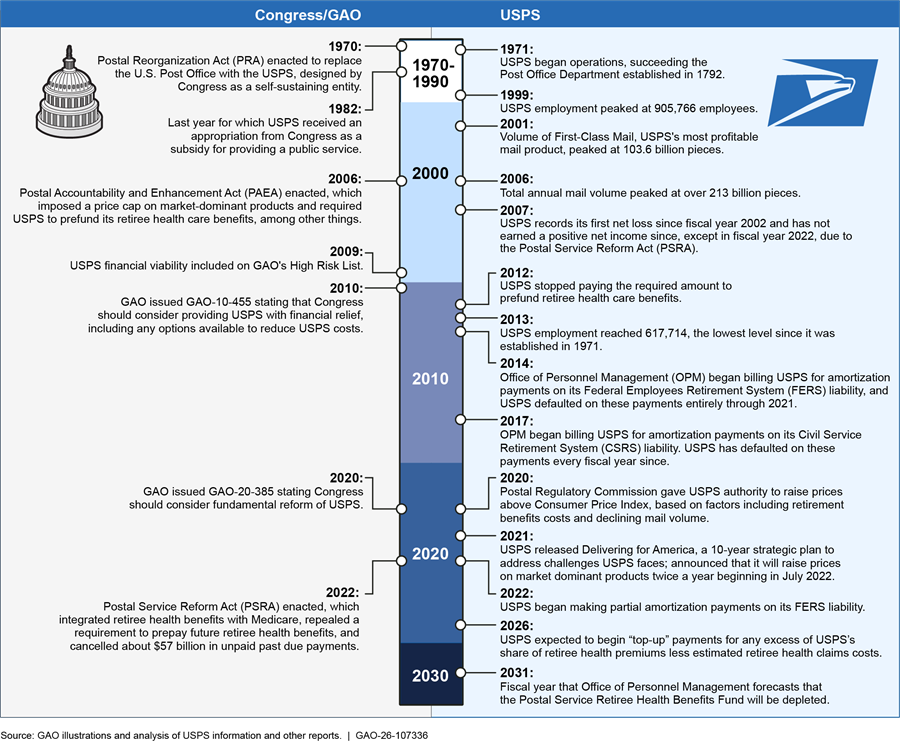

USPS also incurs uncompensated expenses from other mandates. For example, it must provide its employees with various benefits through federal employee benefit programs, including federal pension, employee health care, retiree health care, and workers’ compensation programs. Moreover, in the event of an unresolved labor dispute with its unions regarding a collective-bargaining agreement, USPS is required to accept the results of binding arbitration, and the arbitration board does not have to consider USPS’s financial condition in reaching a decision.[10] Furthermore, USPS faces legal limitations on raising its prices and pursuing alternate sources of revenue. Different legislative acts beginning with the founding of USPS in 1970, established these mandates and limitations and, together with various other factors, they have affected its ability to be financially self-sufficient (see fig. 1).

To help cover its expenses, USPS received an annual appropriation as a public service subsidy through fiscal year 1982. While Congress has not provided this general subsidy since then, it continues to provide relatively small appropriations for certain purposes, such as an annual appropriation to cover revenue forgone for free and reduced-cost mail.[11] Congress has also occasionally provided funding for specific purposes, such as $10 billion from the CARES Act in 2020 to fund operating expenses USPS was unable to fund due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[12] Congress also provided $3 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to purchase zero-emission vehicles and purchase, design, and install associated infrastructure.[13]

From 1971 through 2007, USPS cycled between years of net operating income and net operating losses. During this time, the volume of mail delivered by USPS generally increased each year, peaking at over 213 billion pieces in fiscal year 2006. To reduce expenses associated with increased mail volume and an expanding delivery network in the 1980s and 1990s, USPS increased the efficiency of mail sorting operations by introducing automated letter, flat, and parcel sorting technologies. This helped enable USPS to cover its expenses.

However, mail volumes began declining in fiscal year 2007, due to greater use of electronic means of communication, such as email and mobile phones. Furthermore, USPS officials stated that the recession in 2008 caused a precipitous decline in mail volume. Declining mail volumes have factored significantly into USPS’s deteriorating financial condition, because mail accounts for most of its revenue.

According to USPS, it was unable to raise prices enough to stem revenue losses from declining mail volume, due to price caps on postal products established by the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act in 2006.[14] This act also required USPS to begin making annual prefunding payments for retiree health care benefits, which was an additional weight on an already strained budget.[15]

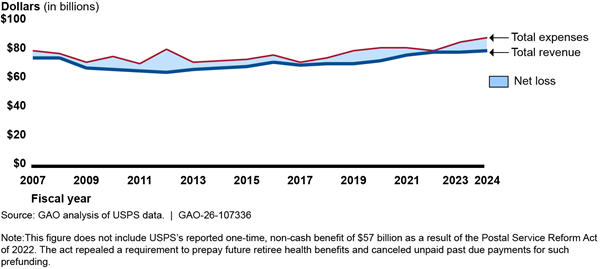

Beginning in fiscal year 2007, USPS recorded consistent net losses as revenue declined while personnel-related expenses, representing the bulk of its expenses, continued to increase. Revenues from postal operations were not sufficient to cover expenses, resulting in annual net losses from fiscal year 2007 through fiscal year 2024 (see fig. 2).

Note: This figure does not include USPS’s reported one-time, noncash benefit of $57 billion as a result of the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022. The act repealed a requirement to prepay future retiree health benefits and canceled unpaid past due payments for such prefunding.

USPS has incurred billions of dollars of net losses each year since 2007, while maintaining enough cash reserves and short-term investments—approximately $14.1 billion at the end of fiscal year 2024—to continue operations.[16] USPS has done this by incurring debt obligations and not making required payments to OPM for retiree health and pension benefits.[17]

USPS’s long-term unfunded liabilities, mostly for retiree health and pension benefits, are a significant financial burden for USPS. As an entity that is intended to be self-sufficient, USPS is supposed to fund these benefits out of its own revenues. However, since 2012, USPS either has not made, or only partially made, its required annual funding payments, contributing to substantial growth in USPS’s unfunded liabilities.[18]

· Pension benefits. Federal law requires USPS to participate in the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) and the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) and contains specific provisions defining its required contribution level to fund these benefits.[19] USPS’s required payments consist of “normal costs,” its share of the cost of FERS benefits attributable to the current year of employees’ service, and “amortization” payments to pay down unfunded FERS and CSRS liabilities over time.[20] See appendix II for more information on USPS’s CSRS obligations and appendix III for more information on its FERS obligations.

· Retiree health benefits. Federal law requires USPS to participate in the Federal Employees Health Benefits program (FEHB), which includes retiree health benefits.[21] Under the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022, USPS now has its own health care program within the FEHB program, and its program is “integrated” with Medicare, in that postal employees are generally required to enroll in Medicare Part B upon retirement to be covered under USPS’s health care program.[22] USPS is responsible for its share of retiree health benefit premiums, which are currently paid out of the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund. Since USPS did not make required prefunding payments from 2012 through 2021 and has not been required to make such payments since 2022, this fund’s balance has been steadily declining. As a result, OPM projects that the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund will be depleted in fiscal year 2031, assuming USPS makes all its required payments to the fund.[23] At that point, if no changes are made, USPS will need to pay its share of retiree health premiums out of its revenue. OPM estimates that these premiums will be about $5.8 billion annually by fiscal year 2031. See appendix IV for more information on USPS’s retiree health benefits obligations.

· Workers’ compensation. Federal law requires USPS to participate in the federal workers’ compensation program (Federal Employees Compensation Act, or FECA program).[24] USPS’s liability for workers’ compensation benefits is an actuarial estimate of the assets that would be needed today to pay for the future benefits associated with all injuries or deaths incurred to date—that is, for all beneficiaries currently on the benefit rolls.[25] This liability is unfunded, as USPS is not required to set aside assets to cover future payments. USPS makes a payment each year to cover the cost of benefits provided to beneficiaries in the past year, plus an administrative fee as determined by the Department of Labor (which administers the program).

According to the OIG, legal limits prevent USPS from adopting certain private industry practices that could further reduce expenses.[26] For example, the OIG reported that the federal workers’ compensation program does not include time limits as to how long a beneficiary is eligible to receive compensation and medical benefits and does not allow USPS to settle workers’ compensation claims.[27] In contrast, the OIG found that 17 states place limitations on the total amount of, or duration of, workers’ compensation disability benefits, and most state organizations can settle claims for future workers’ compensation claims. See appendix V for more information on USPS’s workers’ compensation obligations.

USPS Has Acted to Improve Its Financial Condition, and Congress Has Provided Some Assistance

USPS Has Taken Several Actions to Increase Revenue and Decrease Expenses

In 2021, USPS introduced Delivering for America, its 10-year strategic plan to achieve financial self-sufficiency while continuing to meet its statutory obligations. USPS stated that the plan seeks to modernize its network, meet a changing marketplace, and prompt changes from Congress. Since the introduction of the strategic plan, USPS has taken many actions, including the following:

· Raised prices. The Postal Regulatory Commission gave USPS new pricing authority in November 2020.[28] USPS has raised prices on market-dominant products (such as First-Class Mail) seven times since then, increasing the cost of a First-Class Mail postage stamp by 33 percent.[29] According to USPS, these price increases contributed to an 8.8 percent increase in revenue since fiscal year 2020, from around $73.1 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $79.5 billion in fiscal year 2024.

· Realigned transportation network. USPS aimed to reduce expenses and improve efficiency by implementing new mail transportation strategies. According to USPS, it did not adequately invest in its transportation or processing networks for years prior to 2020 due its poor financial condition. This led to the deterioration of its transportation network, which did not allow the movement of mail and packages in an integrated, precise, and efficient manner. For example, according to USPS, many of its trucks had been leaving facilities less than half full because (1) mail was moved between too many locations and (2) processing schedules were not aligned. USPS is continuing to redesign its transportation operations as part of its strategy to eliminate waste and to efficiently integrate with network operations. At the end of fiscal year 2024, USPS reported that it had saved $535 million in fiscal year 2024 in highway transportation costs, primarily due to its transportation network optimization efforts resulting in the elimination of underutilized transportation trips.

USPS has also moved mail volume from air to ground routes, which contributed to USPS reducing its air transportation expenses by $640 million in fiscal year 2024, according to USPS. As a result of these changes, USPS reported collectively saving over $1 billion annually.[30] USPS has only realigned a portion of its transportation network and plans to roll out further changes on a regional basis over the course of several years.[31]

|

USPS Has Committed Capital Investments to Implement

Its Strategic Plan The U.S. Postal Service (USPS) has planned $40 billion in capital investments over the 10 years of its strategic plan (2021-2031). Thus far, it has already spent $11 billion on capital investments between fiscal years 2021 and 2024. These investments have paid for new facilities, such as the regional processing and distribution center in Atlanta (see photo).

|

· Redesigned mail and package processing operations. USPS redesigned its processing network—its network of facilities to receive, sort, and transport mail between its origin and destination—and began to make significant capital investments in its processing facilities. According to USPS, these changes and capital investments are designed to reduce costs and increase revenues by improving USPS’s operational efficiency. In its legacy network, USPS takes mail through 11 steps in the “middle mile”—from the local post office where the mail originates to the “destination delivery unit,” where it is distributed to carriers for delivery to its ultimate destination. In the redesigned network, the middle mile is reduced to fewer steps.

To accomplish this, USPS stated that it plans to consolidate processing operations into fewer and larger processing, sorting, and delivery centers, organized into 60 regions in a hub and spoke network that covers the nation. According to USPS, as of September 2025, USPS had launched 13 of the planned 60 regional processing and distribution centers that serve as the hubs in its redesigned network. USPS stated that these new facilities within this network are designed with more streamlined layouts, better working environments for employees, and more mechanized package processing systems. As of the end of fiscal year 2025, USPS officials stated that $5.8 billion had been invested in modernizing processing facilities.

USPS also changed service standards for certain First-Class Mail and periodicals; for certain First-Class Mail, it lengthened standards from 1 to 3 days to 1 to 5 days.[32] In 2025, USPS further revised its service standards, which it said would preserve the existing day ranges for First-Class Mail, but some mail and packages would now take longer to deliver.[33]

· Introduced new products. USPS offered new shipping products, with the aim of competing more effectively in the package delivery business and generating more revenue to fund operations. The most prominent new product is Ground Advantage, which USPS introduced in July 2023.[34] USPS credited Ground Advantage with most of its shipping and package revenue and volume growth from fiscal years 2023 through 2024, which was 2 percent and about 3 percent, respectively, across all shipping and package products. Excluding Priority Mail Services, USPS shipping and packages revenue increased by about 25 percent and volume increased by about 10 percent from fiscal year 2023 through 2024.[35] USPS introduced a set of four additional products, known as USPS Connect, in fiscal year 2022. According to USPS, these products leverage ongoing network improvements and other changes to help businesses meet consumer demand for affordable deliveries at different distances within the nation.[36]

· Began making partial payments toward its unfunded pension liability. From 2014 through 2021, USPS did not make its required annual amortization payments to OPM for its two pension programs. Since 2022, USPS has been making partial payments toward its FERS obligation ($500 million of its required $1.6 billion payment in 2022, $600 million of its required $2.1 billion payment in 2023, and $1 billion of its required $2.3 billion payment in 2024).[37] These payments slowed the growth of its unfunded FERS liability but were less than half of the amount due. USPS reported that it missed a total of $27.1 billion in amortization payments from 2014 through the end of fiscal year 2024, when its estimated unfunded FERS liability reached $45.7 billion.

According to USPS officials, USPS has not made any payments toward its unfunded CSRS liability because it cannot make this payment and still meet its statutory obligations to provide postal services.[38] As of the end of fiscal year 2024, USPS has missed $17 billion in CSRS amortization payments assessed beginning in fiscal year 2017. USPS officials also stated that they have prioritized making FERS payments over CSRS, in part because USPS disputes the methodology OPM uses to determine its CSRS payments.

· Converted “pre-career status” employees. USPS stated that a key strategy to creating a stable workforce has been to convert employees from “pre-career status” to “career status.”[39] According to officials, before USPS implemented its strategy to convert employees, the agency had no automatic path to career status. In 2021, we found that USPS pre-career employees had a higher turnover and injury rate than career employees, which negatively affected productivity, efficiency, and service, and incurred expenses.[40] USPS officials also told us that high employee turnover directly affected its ability to stabilize its operations, and its strategy to convert employees allowed it to better align resources with the work. From the end of fiscal year 2020 to the end of fiscal year 2024, USPS reported reducing its total number of employees by less than 1 percent and increasing the number of career employees by about 7.5 percent, while decreasing the number of pre-career employees by about 28 percent.[41] Overall, the percentage of career employees at USPS increased from about 77 to 83 percent between fiscal years 2020 and 2024. During this period, USPS’s total annual compensation and benefits expenses increased by 11 percent, which was less than the cumulative inflation rate for employment expenses of around 18 percent.

· Conducted a voluntary early retirement program. On January 13, 2025, USPS announced an incentive to certain employees who were eligible for optional retirement or voluntary early retirement as of April 30, 2025. USPS officials stated that about 79,000 eligible employees were offered $15,000 each to retire or retire early. This offer was extended to members of two of USPS’s unions, the American Postal Workers Union and the National Postal Mail Handlers Union, which include clerks and mail handlers, among others. USPS officials stated that these employees were at the top of USPS’s wage scale and that the reduction in employees is expected to slow the rate of increase in USPS’s employee compensation and benefit expense but not necessarily decrease it. As of the end of fiscal year 2025, about 10,500 employees had accepted the offer.

USPS has faced setbacks in implementing some of these actions. For example, the OIG found that when USPS launched its first new regional facility and implemented its new surface transportation network for the first time in Richmond, Virginia in October 2023, significant service performance problems emerged that did not abate fully even after the peak holiday mail season concluded.[42] The OIG found similar issues after USPS launched its new regional facility in Atlanta in February 2024; it also found that USPS did not build on lessons learned from the performance problems at the Richmond facility.[43] USPS management told the OIG they had developed plans to address these issues going forward to avoid a repeat of these obstacles when they launch future regional facilities.

USPS has adjusted some of its planned actions after receiving feedback from stakeholders. USPS announced in May 2024 that it was pausing further relocation of certain processing operations until January 2025. In May 2025, USPS officials stated that the pause is still in effect.

In a public letter, the Postmaster General acknowledged confusion and concern on the part of the public and Congress and said that USPS could accommodate a request from Congress to pause implementation and conduct further analysis.[44] USPS officials told us that USPS paused its network modernization efforts to avoid changes during the 2024 election cycle and peak shipping season during the holidays. Furthermore, USPS announced that it would not increase prices for market-dominant products and services in January 2025 and did not plan to do so again before July 2025, 1 year after the last price increase. According to officials, USPS began to implement semi-annual price increases for market-dominant products to minimize the effects of high inflation. However, USPS officials explained, due to Postal Regulatory Commission regulations on rate changes and lower inflation at the time, a January 2025 rate change would not have been advantageous for USPS.[45]

USPS’s Proposals to Change Federal Requirements to Become More Financially Self-Sufficient Have Been Partially Fulfilled

As part of its 2021 strategic plan, USPS sought actions from Congress and other parts of the executive branch to become more financially self-sufficient. Specifically, USPS requested eliminating its required prefunding payments for retiree health benefits, establishing health care plans for only postal workers and retirees, integrating retiree health benefits with Medicare, and reducing its obligation for CSRS pension benefits.

The Postal Service Reform Act of 2022, among other things, eliminated the requirement for USPS to pre-fund its retiree health benefits and canceled $57 billion in payments that USPS had missed since fiscal year 2012. However, USPS still needs to pay for its retiree medical obligations; the elimination of the prefunding requirement means that USPS’s payments will be made over a longer time frame. The act also established postal-only health care plans within the federal employee health benefits program and integrated retiree health benefits with Medicare, generally requiring postal employees to enroll in Medicare Part B upon retirement to be covered by these postal-only health care plans.[46] Consequently, postal retirees in the program who retired beginning in 2025 would have Medicare as their primary payer and the postal health plan as their secondary payer, with certain exceptions.[47] In 2013, we found that postal retirees would have similar levels of coverage under this new integrated plan but that total costs could be higher for some retirees.[48] The integration with Medicare had the effect of reducing USPS’s liability for retiree health care benefits by about $61 billion, or by about 51 percent. USPS estimates that these combined changes (elimination of prefunding, establishment of postal-only health care plans, and integration with Medicare) will result in savings of $40 billion to $50 billion over the next decade.[49]

USPS has also requested that OPM re-allocate the responsibility for CSRS benefits for retirees who worked at the pre-1971 Post Office Department before transitioning to employment with USPS. The USPS OIG and the Postal Regulatory Commission previously opined that the current method allocates too much of the cost of these benefits to USPS, and both have proposed alternative methodologies, while the OPM OIG opined that the current method is appropriate.[50] OPM stated that it did not have the authority to make this change without congressional action and, in 2011, we found the current methodology to be consistent with applicable law.[51] More recently, the Department of Justice has concurred that OPM does not have the authority to make such a change.[52] In its updated strategic plan, USPS has stated that it will ask Congress to do so.

USPS’s Current Financial Condition Is Poor, and It Does Not Have Updated Financial Projections

USPS’s Expenses Have Outgrown Revenue

USPS continues to be in poor financial condition, as its net losses have totaled $118 billion since it last earned a positive net income in fiscal year 2006.[53] Further, USPS has lost about $31 billion since fiscal year 2020, just before USPS released its original strategic plan in March 2021.[54]

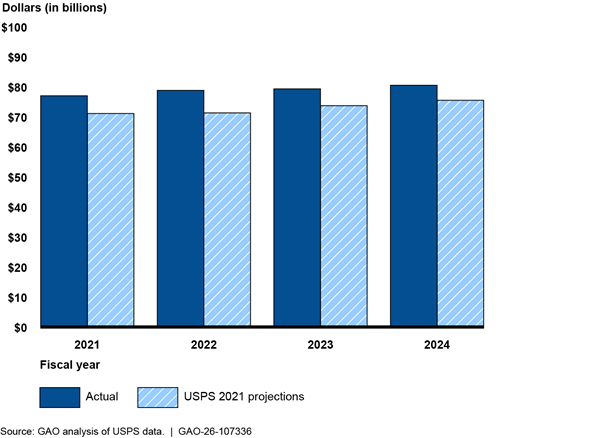

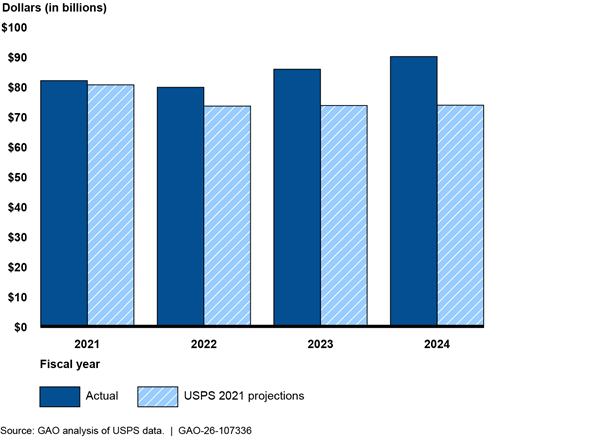

Regarding its revenue, USPS earned about $24 billion (8 percent) more than projected from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 in its original strategic plan (see fig. 3). USPS attributed its higher-than-projected revenues to a combination of higher prices and higher-than-expected mail volume, resulting from the implementation of its strategic plan. USPS increased market-dominant mail prices seven times and increased competitive mail prices four times between November 2020 and July 2024.[55] Additionally, USPS delivered about 16.1 billion more mail pieces than projected for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 and about 500 million more mail pieces than projected for fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

Note: Projected revenue amounts are from USPS’s original strategic plan released in March 2021.

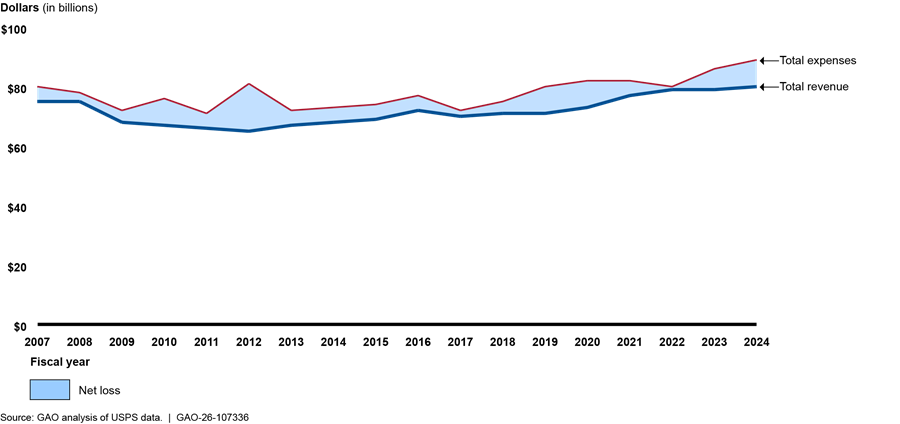

However, while USPS’s revenue exceeded projections, so did its expenses. USPS’s expenses were a total of about $36 billion (11.9 percent) higher than USPS originally projected in its 2021 strategic plan for fiscal years 2021 through 2024 (see fig. 4). USPS attributed these higher-than-expected expenses to, among other things, higher-than-expected inflation and the noncash impact of its workers’ compensation expense.[56]

Note: Projected expense amounts are from USPS’s original strategic plan released in March 2021.

USPS’s total expenses increased by 9.3 percent from about $82.4 billion in fiscal year 2020, the year before USPS’s original strategic plan was introduced, to about $90 billion in fiscal year 2024. As stated above, USPS has taken action to reduce its expenses. For example, USPS reported that its actions to reduce its mail transportation expenses led to a decrease of about $840 million from its fiscal year 2021 expense of about $9.7 billion. However, transportation expenses were about the same level in fiscal year 2024 as in fiscal year 2020, and USPS’s compensation and benefits expenses increased from fiscal years 2020 to 2024 by about $5.3 billion (about 11 percent).

The 9.3 percent increase in USPS’s total expenses from fiscal years 2020 to 2024 does not fully reflect its operational performance in controlling expenses over this period, due to the effect of two components of USPS’s reported expenses.

· First, the noncash components of USPS’s workers’ compensation expense mentioned above are highly variable as they are a result of actuarial and discount (or interest) rate changes and are not directly tied to its operations. These two elements of USPS’s workers’ compensation expense have both decreased and increased USPS’s reported expenses between fiscal years 2020 and 2024. For example, the actuarial revaluation of existing cases and the impact of discount rate changes combined reduced USPS’s fiscal year 2022 expenses by about $3.3 billion but increased its fiscal year 2024 expenses by about $2.5 billion.

· Second, the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022 changed USPS’s reporting of its retiree health benefits expenses in a way that affects the comparability of USPS expense over the period from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2024. USPS’s reported retiree health benefits expenses were reduced from about $5.1 billion in fiscal year 2022 to zero in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 because the Postal Service Reform Act ended USPS’s requirement to prefund retiree health benefits. This effectively deferred retiree health payments to future years and was not reflective of any operating changes.

We calculated an alternative measure of the growth of USPS’s expenses over this 4-year period by removing these two factors. Under this alternative measure, USPS’s expenses increased by 14.9 percent from fiscal years 2020 to 2024 (see table 1 below).

|

|

|

|||||

|

Fiscal year |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Percent increase from fiscal years 2020 to 2024 |

|

USPS’s reported total expensesa (dollars in billions) |

$82.4 |

$82 |

$79.7 |

$85.8 |

$90 |

9.3% |

|

USPS’s total expenses adjusted to exclude workers’ compensation fluctuations and discontinued retiree health prefunding payments |

$76.2 |

$78.8 |

$83 |

$86.4 |

$87.6 |

14.9% |

Source: GAO analysis of USPS information. | GAO‑26‑107336

Note: Totals and differences may not be exact due to rounding.

aUSPS’s total expenses include its operating expenses and its interest expense.

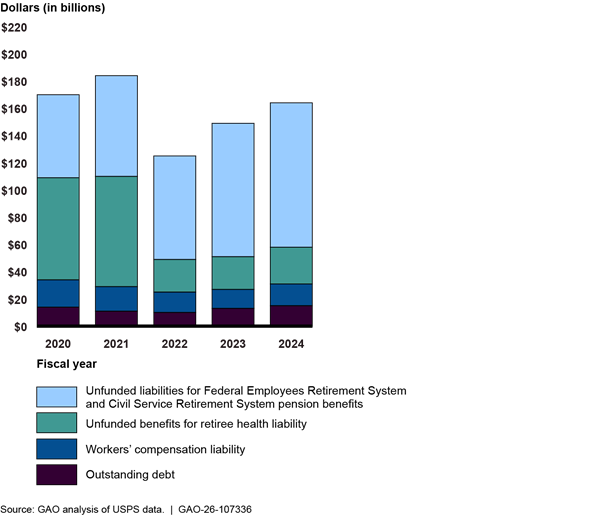

In addition to USPS’s expenses, its unfunded benefit liabilities (which include workers’ compensation, retiree health, and CSRS and FERS pension benefit unfunded liabilities) and debt have long been another source of concern for its financial sustainability. USPS’s unfunded benefit liabilities and debt (about $61.7 billion) were about 82 percent of USPS’s annual revenue at the end of fiscal year 2007, the first fiscal year of USPS’s consecutive years of net losses (except for the noncash income in fiscal year 2022). Since then, this percentage has more than doubled, to about 206 percent of USPS’s revenue (unfunded liabilities and debt of $163.7 billion) as of the end of fiscal year 2024.[57]

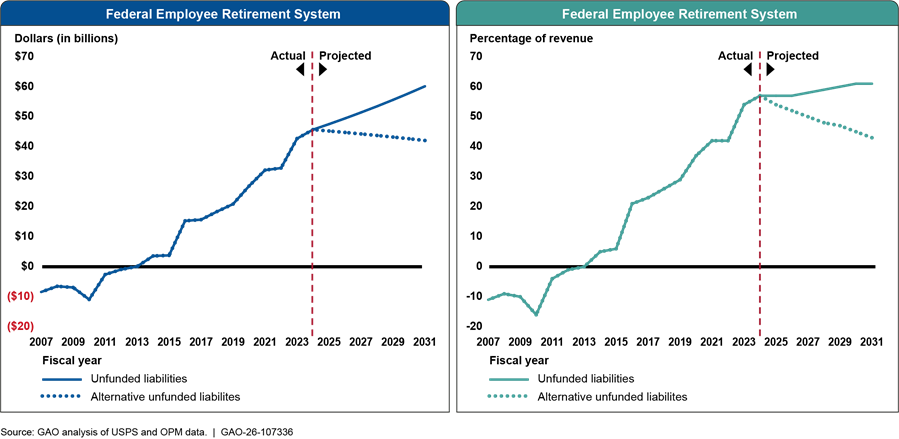

USPS’s FERS unfunded liability grew from $26.9 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $45.7 billion in fiscal year 2024, an increase of about 70 percent, due, in part, to USPS not making about $6.7 billion in required payments toward this unfunded liability.[58] USPS also did not make $12.2 billion in required payments toward its CSRS unfunded liability from fiscal years 2020 to 2024. This led, in part, to this unfunded liability increasing from about $33.8 billion in fiscal year 2020 to about $60.2 billion in fiscal year 2024, an increase of about 78 percent. In addition to its unfunded liabilities, USPS increased its debt to the U.S. Treasury from $14 billion in fiscal year 2020 to its statutory maximum of $15 billion by the end of fiscal year 2024 (see fig.5).

Figure 5: U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) Unfunded Benefit Liabilities and Debt, Fiscal Years 2020-2024

Note: In fiscal year 2022, the Postal Service Reform Act reduced USPS’s retiree health benefits unfunded liability by $61.2 billion by integrating USPS’s retiree health benefits with Medicare, which shifted costs from USPS to Medicare.

In addition to continued annual losses and large unfunded liabilities, there are other indicators of USPS’s poor financial condition, including:

· impact of unfunded pension liabilities on expenses. USPS paid $1 billion of its required $5.5 billion in pension amortization payments in fiscal year 2024.[59] By not making full payments, USPS’s unfunded pension liabilities will most likely continue to grow, increasing the likelihood that its required amortization payments will also grow, negatively impacting USPS’s expenses; and

· future impact of unfunded retiree health care liabilities. As required by federal statute, OPM uses funds from the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund to pay USPS’s share of retiree health care premiums.[60] However, doing so reduces the balance of the fund each fiscal year since USPS is not making payments into the fund. Starting no later than the end of fiscal year 2026, USPS is required to pay the excess, if any, of its share of the retiree premiums over the estimated postal retiree health care net claims costs (i.e. claims cost less the retirees’ share of premiums) for the previous fiscal year.[61] As stated above, OPM projects that the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund will be depleted in fiscal year 2031 when these payments are taken into account. When the funds are exhausted, USPS’s annual expenses will increase to cover its share of retiree health care premiums, at which time OPM projects these premiums to cost about $5.8 billion per year. Needing to pay these premiums annually from USPS’s revenue would counteract its expense reduction efforts.

USPS officials stated that it has not made all of its payments toward its unfunded liabilities because it is in an unsustainable financial position. USPS reported that if it paid all required amortization payments for all its unfunded liabilities, it would not have enough liquidity to cover current and anticipated operating expenses, deal with contingencies, and make needed capital investments. USPS stated that it has prioritized payment toward its unfunded liabilities based on the availability of funds, among other things. While not making some of these payments in full has allowed USPS to preserve its cash liquidity, not making these required payments may make it more difficult for it to pay for these benefits in the future.

USPS Does Not Have Updated Projections of Its Future Financial Condition

While USPS updated its strategic plan in September 2024, it did not develop financial projections for its future financial performance, such as for its future revenue, expenses, or net income, in the updated plan.[62] USPS reported that it did not develop such projections, as it was neither required nor productive to do so.[63] According to USPS, in addition to the large number of assumptions inherent in creating multi-year financial projections, such projections are not a meaningful way to assess its progress in implementing its updated strategic plan. USPS stated that its financial reports have financial metrics, such as controllable income and controllable expenses, which are a better way to evaluate its updated strategic plan’s overall progress toward achieving financial self-sufficiency.[64] In addition, USPS also reported that measures such as its net income are highly dependent on factors outside of its control, such as its pension amortization payments and the noncash components of its workers’ compensation expense.

USPS has made financial projections in the past. In its 2021 strategic plan, USPS projected its revenue, expenses, and net income each fiscal year, from 2021 through 2030, and if all the actions in the plan were implemented. USPS projected that its revenue would equal its expenses in fiscal year 2023 and that it would start earning a positive income in fiscal year 2024. However, as stated above, USPS’s revenue did not equal its expenses in fiscal year 2023 as it had projected in 2021. USPS officials stated that this is due, in part, to the actions outlined in its original strategic plan being only partially implemented and to higher-than-expected inflation.

However, we have found that goals, including financial projections, such as projections of revenue, expenses, and unfunded liabilities, are a key practice that can use evidence to effectively assess results. Goals communicate the results that an organization seeks to achieve and allow assessments of performance by comparing planned and actual results. Goals should include near-term results that have quantitative targets and timeframes against which performance can be measured, such as for revenue earned, expenses incurred, and level of unfunded liabilities each fiscal year. Goals should also be linked to long-term outcomes, such as achieving financial self-sufficiency.[65] One benefit of having quantitative targets with timeframes is that an organization can use them to inform different types of decisions, such as identifying problems, determining corrective actions for those problems, and continuing to implement successful strategies. Without financial projections, USPS does not have targets to show progress against its planned goals or to effectively communicate to policymakers how its actions will help to restore its financial self-sustainability.

Such projections will become even more important, as USPS will soon have additional new expenses. First, starting no later than the end of fiscal year 2026, USPS is required to fund the excess, if any, of its share of retiree premiums over the estimated amount of postal retiree health care net claims cost for the previous fiscal year. OPM estimates that these payments will be about $750 million in fiscal year 2026 and grow to about $1.4 billion in fiscal year 2031. Second, USPS is required to pay for its share of retiree health benefit premiums when the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund is depleted. OPM estimates that this will occur in fiscal year 2031, by which time OPM projects that USPS’s share of retiree premiums will be about $5.8 billion per year.

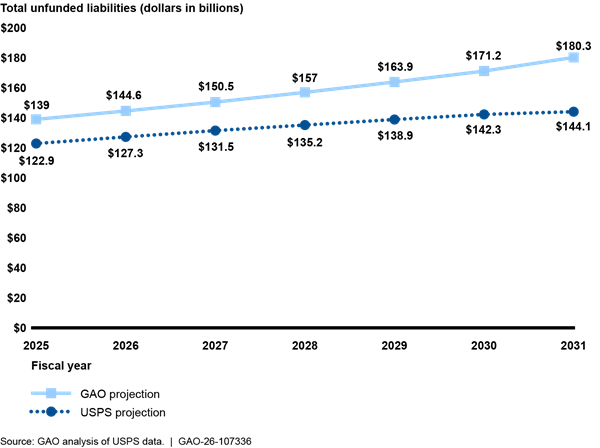

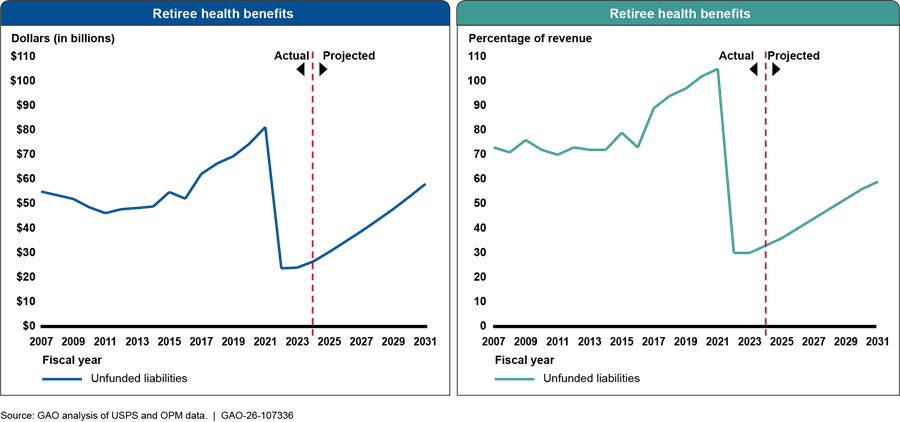

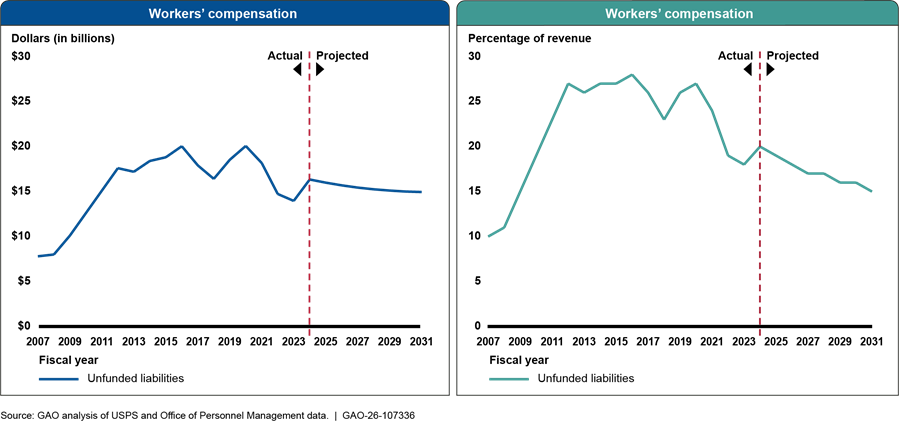

USPS’s Unfunded Benefit Liabilities Will Be Higher than Projected If Current Trends Continue

USPS’s four unfunded benefit liabilities include pensions (FERS and CSRS), retiree health benefits, and workers’ compensation.[66] According to projections USPS sent to us, USPS projects that its pension and retiree health care unfunded benefit liabilities in aggregate will increase about 22 percent from fiscal years 2024 through 2031.[67] However, these projections assume that USPS would make its full required pension amortization payments for both FERS and CSRS starting in 2025, which USPS has not done since OPM started assessing USPS for these payments.[68] Specifically, USPS did not make any payments toward its FERS unfunded liability between fiscal years 2014 to 2021 and for its CSRS unfunded liability between fiscal years 2017 and 2024. USPS started making partial payments toward its FERS unfunded liability in fiscal year 2022.

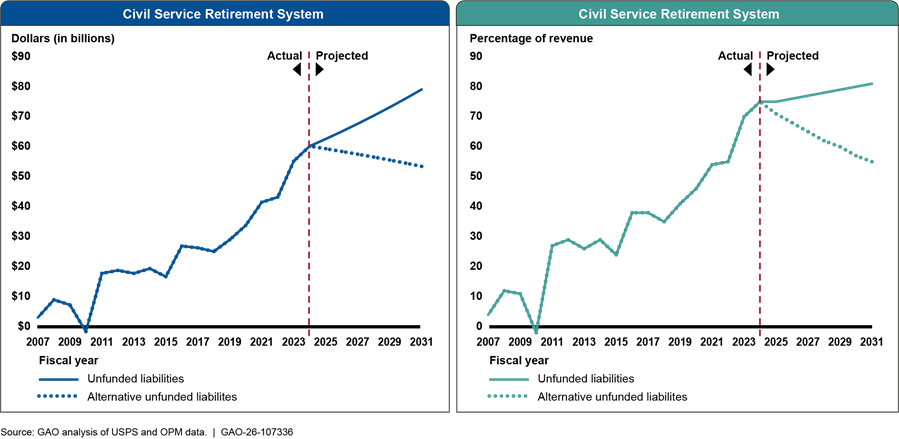

We project that if USPS continues to make payments similar to what it has done since fiscal year 2022, its unfunded liabilities will grow more than USPS projects, all other things being equal (see fig. 6). Based on our analysis of OPM data, we project that USPS’s CSRS unfunded liability will increase by about 27 percent between fiscal years 2024 and 2031, if USPS continues to not make any required payments toward it. Additionally, without an additional funding source for the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund, that unfunded liability is expected to increase by about 91 percent between fiscal years 2024 and 2031 as the fund approaches depletion. If USPS continues to pay a portion of its required payments toward its FERS unfunded liability, that unfunded liability is projected to decrease by about 6 percent between fiscal years 2024 and 2031.[69]

Figure 6: GAO and USPS Projections of U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS’s) Pension and Retiree Health Unfunded Liabilities, Fiscal Years 2025-2031

Note: USPS’s projection assumes that all required amortization payments are made in full, whereas GAO’s projection assumes USPS makes the same level of amortization payments that it has in recent years. USPS’s projection uses the vested accrued liability for retiree health care benefits, whereas GAO’s projection uses the total accrued liability. USPS’s projections provided to us were unpublished.

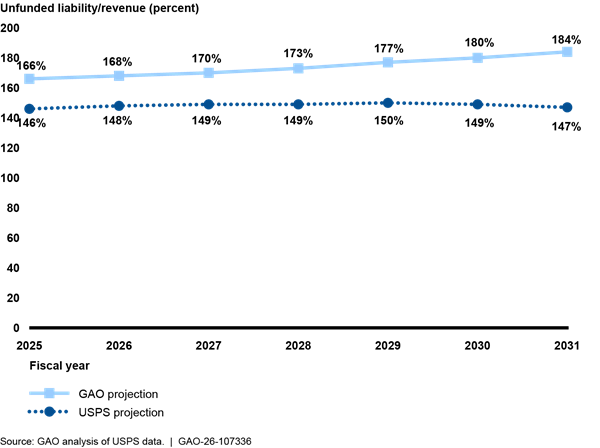

These projections can also be measured against USPS’s projected annual revenue as an estimate of USPS’s capacity to meet these unfunded liabilities. As of the end of fiscal year 2024, these four unfunded benefit liabilities represented about 187 percent of USPS’s fiscal year 2024 revenue. When including its $15 billion debt, they represented about 206 percent of fiscal year 2024 revenue. USPS projects that if it makes all of its required amortization payments in full, its pension and retiree health unfunded liabilities will remain relatively stable, compared with USPS’s projected annual revenue over the fiscal year 2025-2031 period, ranging between 146 percent and 150 percent of USPS’s revenue.[70] However, if USPS’s historical pattern of payments continues, we project that these unfunded liabilities will increase to an estimated 184 percent of its projected fiscal year 2031 revenue (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: GAO and U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) Projections of USPS’s Pension and Retiree Health Care Unfunded Liabilities as a Percentage of Projected Revenue, Fiscal Years 2025-2031

Note: USPS’s revenue projections provided to us for fiscal years 2025 to 2031 do not include interest income. USPS’s projections provided to us were unpublished.

USPS Officials and Stakeholders Said USPS’s Financial Condition Will Continue to Be a Challenge

USPS officials and stakeholders we interviewed said that USPS will continue to face challenges to improving its financial condition and achieving self-sufficiency. USPS stated that it expects overall mail volume to continue its years-long decrease as customers continue their shift toward digital communication. USPS also stated that it competes with private sector package delivery providers, who will continue to divert packages away from USPS, which may cause declines in its package volume. In addition to its projections showing continued annual losses, USPS also stated that it would run out of cash as early as fiscal year 2026 if it made all its required pension amortization payments. Alternatively, USPS reported that it would run out of liquidity in fiscal year 2029 if it continues to make partial pension amortization payments at roughly the same levels as it has in recent years. USPS stated in November 2024 that its liquidity was insufficient to pay all of its obligations, make necessary capital investments, and prepare for unexpected contingencies without putting its ability to fulfill its primary mission at undue risk. USPS further stated that if it does not have sufficient liquidity, it may prioritize its payments to employees, suppliers, and debt before the required payments to fund pension benefits.

The OIG has noted that USPS’s unfunded pension and retiree health care liabilities will put further pressure on USPS’s ability to restore its financial self-sufficiency while making its planned capital investments.[71] In addition, six of the 12 stakeholders we interviewed stated that they did not expect USPS to be able to cover its expenses with its revenue (i.e., “break even”), and two stakeholders stated that it was not clear if USPS could break even or not.

Options Exist to Improve USPS’s Financial Condition, but Congressional Action Is Required to Attain USPS Self-Sufficiency

A Wide Range of Options Exist to Improve USPS’s Financial Condition

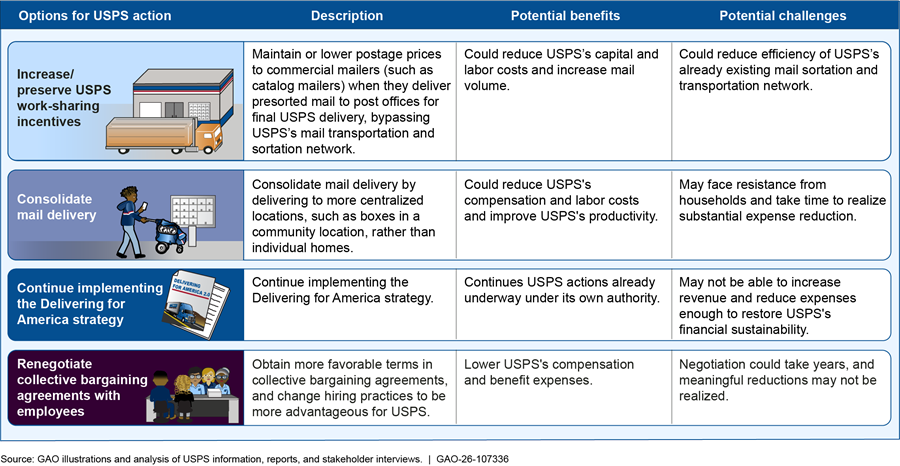

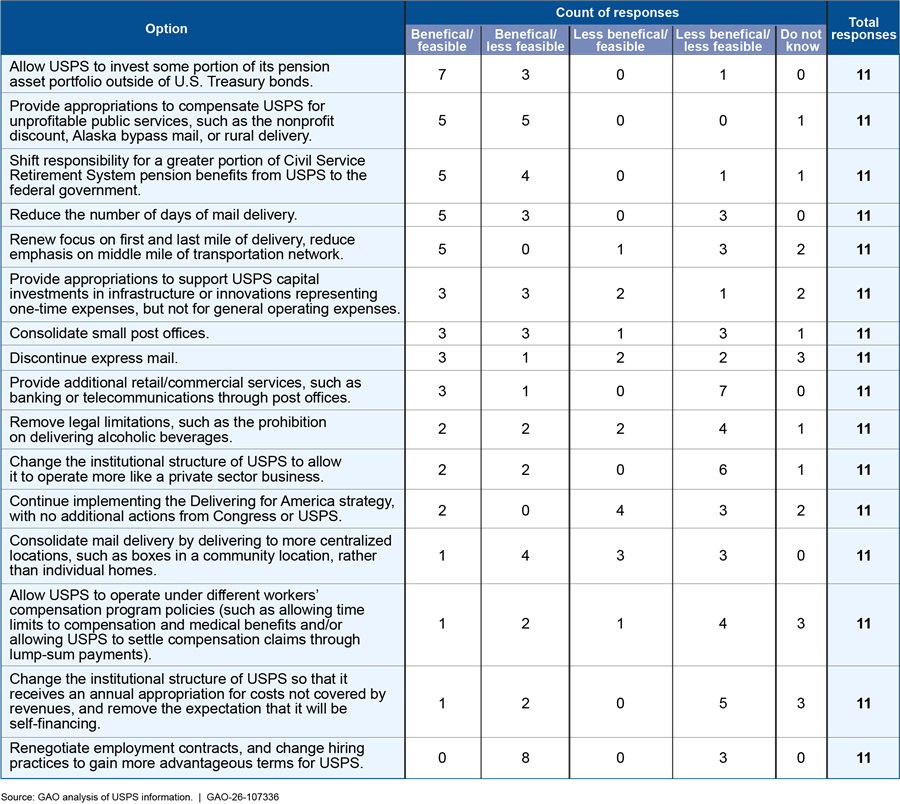

The 12 stakeholders we interviewed identified a wide range of options to improve USPS’s financial condition but did not agree on which options USPS should take. While four stakeholders said that USPS could do more to reduce its labor expenses, no other option mentioned by the stakeholders interviewed was suggested by more than one stakeholder (see fig. 8). In addition, four stakeholders said that there is little or nothing USPS could do on its own to achieve financial self-sufficiency.

Figure 8: Potential U.S. Postal Service (USPS) Options Most Mentioned by Stakeholders to Improve Its Financial Self-Sufficiency

Note: Stakeholders we interviewed included labor unions, an organization representing commercial mailers, a consultant to commercial mailers, and individuals with subject matter expertise. We judgmentally selected these stakeholders from our prior postal work and from their public statements on postal issues, such as comments submitted to the Postal Regulatory Commission on USPS’s strategic plans.

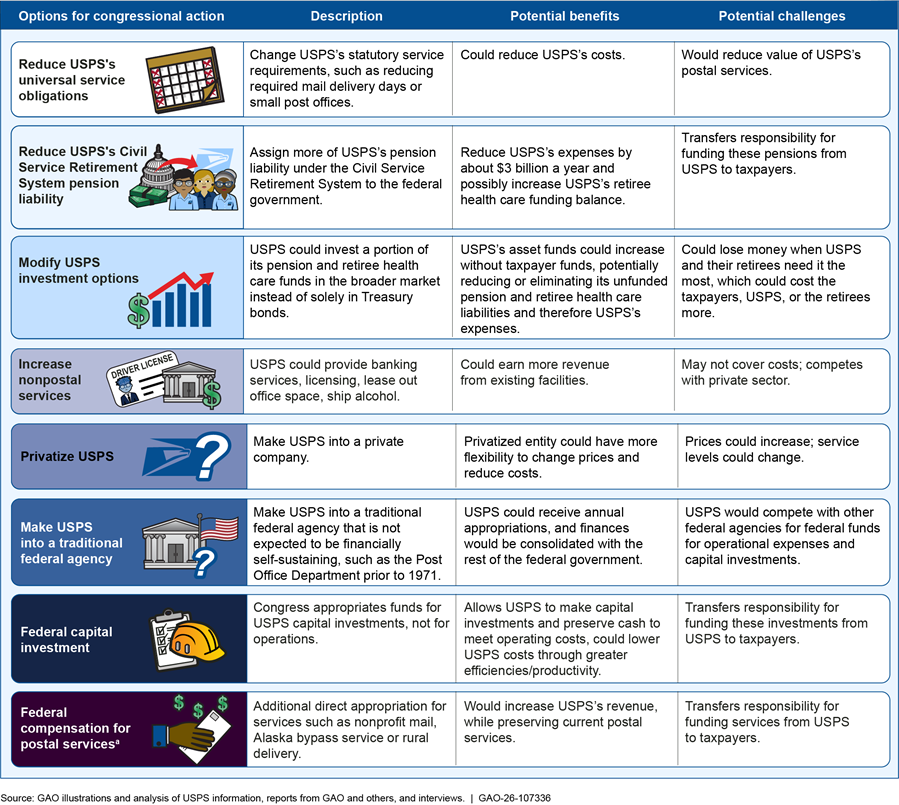

Stakeholders and USPS officials identified several options for congressional action that they believe could help USPS to reduce expenses, increase revenue, and provide funds for USPS operations or capital investments. However, the options could also increase costs to taxpayers or reduce USPS’s level of postal services (see fig. 9).

Figure 9: Potential Congressional Options Most Often Mentioned by Stakeholders to Improve the U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) Financial Self-Sufficiency

Note: Stakeholders we interviewed included labor unions, an organization representing commercial mailers, a consultant to commercial mailers, and individuals with subject matter expertise. We selected these stakeholders from our prior postal work and from their public statements on postal issues, such as comments submitted to the Postal Regulatory Commission on USPS’s strategic plans. See Appendix VI for a full list of options mentioned by stakeholders.

aUSPS’s Alaska by-pass mail service is mail that bypasses USPS facilities to be prepared by third-party shippers for transportation and delivery to rural Alaska by third-party air carriers.

The 12 stakeholders we interviewed described the benefits and feasibility of potential options Congress could take and indicated that some options would be more beneficial or more feasible than others. For example, 10 of the 11 stakeholders who responded to our follow-up questionnaire about these options indicated that allowing USPS to modify investment options for its pension funds would be either moderately or highly beneficial to its financial self-sustainability, and seven stakeholders indicated that this option would be either very or moderately feasible.[72] In contrast, four stakeholders indicated that increasing non-postal services, such as providing banking services, would be either moderately or highly beneficial.[73]

USPS’s Financial Condition Will Not Be Sustainable Without Congressional Action

We have previously reported that actions USPS could take under its own authority are likely to be insufficient to fully address its financial situation.[74] USPS acknowledges that its actions alone will not result in it becoming financially self-sufficient. We have suggested that Congress consider various options in the past. While Congress has taken some action to address the matters we previously identified, some important considerations remain unresolved. Specifically:

· In 2020, we stated that Congress should consider reassessing and determining (1) the level of postal services the nation requires, (2) the extent to which USPS should be financially self-sustaining, and (3) the appropriate institutional structure for USPS.[75] Congress partially addressed the first two issues in the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022 by codifying the requirement that USPS generally deliver mail at least 6 days a week, among other things.[76] However, the act was silent on USPS’s institutional structure. As of November 2025, at least two bills that could partially address USPS’s financial issues have been introduced.[77]

· We reported in 2018 that the financial outlook for the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund was poor, as USPS had not made any payments into it since 2010. Therefore, we stated that Congress should consider passing legislation to put postal retiree health benefits on a more sustainable financial footing. The Postal Service Reform Act of 2022 partially addressed this issue by integrating USPS’s retiree health care plans with Medicare, among other things. However, USPS is still responsible for paying its share of retiree health benefit premiums, which are currently paid out of the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund. OPM estimates that the fund supporting postal retiree health benefits will be depleted in fiscal year 2031. At that point, USPS would be required to pay its share of retiree health care premiums, which OPM estimates to be about $5.8 billion per year.

Conclusions

Recent USPS and congressional actions have reduced some USPS expenses and increased USPS’s revenue, but these actions collectively have not restored USPS’s financial self-sufficiency—putting the current level of postal services and taxpayer funds at risk.

Given the magnitude of the challenges in restoring USPS to financial self-sustainability, we continue to believe that both USPS and congressional action is necessary. While USPS can and should continue to act under its own authority to increase revenue and reduce USPS’s expenses, timely congressional action is also needed to improve USPS’s financial sustainability. However, without current financial projections, USPS is hampered in its ability to communicate to the public and policymakers on progress toward USPS’s objectives and what actions can best help in restoring its financial self-sustainability. It is critical for USPS and Congress to address USPS’s unsustainable business model before it will be responsible for billions in new annual expenses for retiree health care, which is likely in 2031. The sooner actions are taken to improve USPS’s financial health, the less drastic those actions will need to be to address the fundamental tension between the expense of providing the level of postal services Congress expects and the revenue USPS can earn from that level of service. Given the current and potential future state of USPS’s finances, we believe that Congress should act now to consider the matters we previously made. This would include fully addressing the level of postal service the nation requires, the extent to which USPS should be self-sustaining, and a sustainable financial path for retiree health benefits.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to USPS:

The Postmaster General should develop current financial projections out to at least fiscal year 2032, after the assets in the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund are projected to be exhausted, such as for its revenue, expenses, net income, and unfunded liabilities that link USPS’s near-term results to USPS’s desired long-term outcomes, and make them publicly available. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to USPS. USPS provided written responses, which are reproduced in Appendix VII. In its response, USPS disagreed with our recommendation to develop current financial projections out to at least fiscal year 2032 and make them public. As described below, we continue to believe that the recommendation is valid.

USPS stated that the recommendation would not promote solving the Postal Service’s unsustainable business model and that publishing long-term projections does not promote trust with stakeholders. USPS noted that long-term projections are inherently uncertain and stated that such projections can contribute to a misperception of the success of different initiatives. USPS noted that when it did not meet the long-term projections published in its Delivering for America plan in 2021, certain stakeholders opposed the plan, citing USPS’s unmet projections. We acknowledge that falling short of a projection does not necessarily reflect a management failure but could be caused by unanticipated factors beyond management control. We further recognize that publishing long-term projections does not directly address the Postal Service’s unsustainable business model, as meaningful changes to that model are the purview of Congress. Both our past work and this report make it clear that congressional action is needed to fix the unsustainable business model.

While we understand the inherent uncertainty of long-term financial projections, we continue to see their value to USPS, Congress and external stakeholders. Specifically, without long-term financial projections, USPS cannot fully communicate its progress toward financial sustainability, and Congress cannot measure USPS’s progress against its planned goals. While we acknowledge the criticism that USPS faced when it did not meet its long-term projections published in 2021, USPS could mitigate such criticism by producing a range of projected outcomes that demonstrate how potential USPS and congressional actions, as well as market forces such as inflation, could affect USPS’s future financial condition. The range of projected outcomes could encompass varying assumptions with regard to factors, such as inflation, mail volume, or congressional action or inaction. Such a range of projections could help external stakeholders better understand the uncertainty of USPS’s future financial condition, and the illustration of the risks could be an additional spur to action by Congress.

USPS also stated that it already publishes short-term financial projections in its annual Integrated Financial Plan. However, these projections are only for the upcoming fiscal year, and it will likely take several fiscal years of concerted effort from USPS and Congress to achieve financial sustainability for USPS. As a result, we maintain that financial projections that go to at least fiscal year 2032, when the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund is expected to be depleted, would be an important tool to allow USPS and Congress to link results to desired long-term outcomes.

USPS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Postmaster General, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

For any questions about this report, please contact us at marronid@gao.gov or todiscof@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VIII.

David Marroni

Director, Physical Infrastructure

Frank Todisco

Chief Actuary

Mr. Todisco meets the qualification standards of the American Academy of Actuaries to address the actuarial issues contained in this report.

This report examines the U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) current financial condition. Our objectives were to examine: (1) recent USPS actions to improve its financial condition, (2) USPS’s current financial condition and the extent to which USPS projects its financial information, and (3) options that could improve USPS’s financial condition.

To provide information on recent USPS actions to improve its financial condition, we reviewed USPS’s original 10-year strategic plan and its most recent update. We reviewed USPS reports on actions taken under its strategic plan and interviewed USPS officials about these actions. We also reviewed our prior work and reports from USPS, the USPS’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG), the Postal Regulatory Commission, and other organizations. In addition, we conducted a site visit to new and legacy postal facilities in Atlanta, Georgia, to gain a better understanding of the changes USPS is undertaking to its mail transportation and mail processing networks. The new postal facilities included a regional processing and distribution center and a sorting and delivery center, where we observed elements of USPS’s new processing and delivery operations. We also observed processing operations at a legacy processing and distribution center in Atlanta.

To examine USPS’s current financial condition and future projections, we reviewed and summarized its financial reports, original 10-year strategic plan released in 2021, and its most recent update released in 2024, reports to Congress, and other reports that contained financial information. We completed almost all of our audit work before USPS released its fiscal year 2025 financial results. We have included some financial information from fiscal year 2025 in this report. We reviewed USPS’s revenue and expense projections for fiscal years 2025-2030. We also assessed the extent to which USPS’s updated strategic plan is consistent with key practices on using evidence from GAO’s principles of evidence-based policymaking.[78]

We reviewed USPS documentation about their projections through 2032 of their actuarial liabilities and assets for pension and retiree health benefits. We used Office of Personnel Management (OPM) data to make our own projections of USPS’s pension and retiree health care unfunded liabilities. To do so, we reviewed OPM documentation and interviewed OPM officials about the methodology, data, and assumptions used in their actuarial valuations and projections. To project USPS’s unfunded pension liabilities, we used a standard actuarial roll-forward approach, assuming no future actuarial gains or losses from experience or from assumption changes. We varied these pension projections based on different assumptions as to the degree to which USPS makes required amortization payments, based on interactions with USPS officials.

To project USPS’s unfunded liability for retiree health care benefits, we relied on a projection that OPM provided to us of the depletion of the retiree health benefit fund. OPM’s projection included projections of fund assets, premiums and late enrollment penalties paid from the fund, and required top-up payments made into the fund. We projected the normal cost and liability forward, assuming no future actuarial gains or losses from experience or from assumption changes and using OPM’s medical trend rate assumption and USPS’s projection of its future workforce.

We also used data from USPS’s annual financial reports to project USPS’s workers’ compensation liability. We did so using a “macro” type of methodology, using historical aggregate values and relationships to extrapolate into the future. We assumed no future actuarial gains or losses from discount rate changes or from actuarial revaluations. On the basis of historical impacts of discount rate changes on the liability, we estimated the duration of the historical liabilities, normalized them to a common discount rate, and looked at historical benefit payouts as a percentage of the adjusted liabilities. We also made an assumption as to the excess duration of the cost of new cases over the duration of the liability, adjusted the cost of new cases to a common discount rate, and looked at the adjusted historical cost of new cases as a percentage of payroll. We then projected both the cost of new cases and the benefit payouts to roll forward the liability. We also examined the sensitivity of the projection to key assumptions. The methodology was reviewed by a GAO property and casualty actuary.

All of these actuarial projections should not be regarded as predictions and were performed to indicate plausible directions and magnitudes of USPS’s unfunded liabilities should no additional action be taken or requirements change, including the size of its unfunded liabilities relative to its annual revenue, and to provide additional insight into USPS’s future financial condition, including in comparison to historical results.

To identify options that could improve USPS’s financial condition, we reviewed prior reports by us, USPS’s OIG, and others on USPS’s financial condition and its original and updated strategic plans. We also interviewed USPS, OIG, and Postal Regulatory Commission officials as well as 12 postal stakeholders, including labor unions, an organization representing commercial mailers, a consultant to commercial mailers, and individuals with subject matter expertise.

We judgmentally selected the 12 stakeholders from our prior postal work and from their public statements on postal issues, such as comments submitted to the Postal Regulatory Commission on USPS’s strategic plans. We individually interviewed these stakeholders on potential options available to USPS and Congress that could improve USPS’s financial sustainability, as well as the benefits and challenges for each option. We then sent a survey to these stakeholders asking them about the options mentioned in our individual interviews; we received 11 responses. The survey asked them to rank how beneficial each option was to USPS’s financial sustainability and how feasible each option was to implement on a five-point rating scale and for any additional comments on each option. While the views of the stakeholders we interviewed are not generalizable, they provide information and different perspectives on options for USPS.

We analyzed and classified stakeholder responses to our survey based on how beneficial and feasible they ranked the options. We classified their response to each option as either “beneficial” or “feasible” if the stakeholder responded that the option was either “highly” or “moderately” beneficial or feasible and “less beneficial” or “less feasible” if the stakeholder responded that the option was either “slightly” or “not at all” beneficial or feasible. We then created four groups (“Beneficial/Feasible,” “Beneficial/Less Feasible,” “Less Beneficial/Feasible,” and “Less Beneficial/Less Feasible”) by combining our classification of each stakeholders’ response for each option. The introduction to the survey and a summary of the results are presented in appendix VI.

In addition, we relied on our prior work that addressed some of these options. We selected options mentioned either by USPS or by more than one stakeholder and summarized similar options for analysis. We analyzed USPS and stakeholder comments, as well as applied standard economic and actuarial principles to identify each selected option’s benefits and challenges. We compared Congress’s actions against our four open matters concerning USPS to identify progress made on these matters.[79]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The U.S. Postal Service (USPS) participates in the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS), one of two defined-benefit pension plans administered by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).[80] CSRS covers federal employees who first entered a covered position before 1984, including employees of the Post Office Department and USPS. In fiscal year 2024, about 5,000 current USPS employees were covered under CSRS, which is 1 percent of all active USPS employees enrolled in pension benefits.[81] In contrast, a much greater number of postal retirees were covered under CSRS—OPM estimated that at the end of fiscal year 2023, 362,000 postal annuitants, or 51 percent of USPS annuitants and beneficiaries, were covered under CSRS.[82]

CSRS is a “funded” plan, with participating employees required to make contributions into the fund, as well as USPS depending on the plan’s funded position, and with pension benefits paid to retirees from the fund.[83] Pursuant to federal statute, fund assets are invested in interest-bearing U.S. Treasury securities, whose principal and interest are guaranteed.[84] Participating USPS employees contribute 7 percent of their pay into the fund.

USPS’s Funding Requirements for CSRS

USPS is required to make one type of actuarially determined payments into the fund each year, known as an “amortization cost” payment. Amortization cost payments are amounts intended to pay down any unfunded liability over a particular time frame.[85] The unfunded liability is calculated to be any excess of the actuarial accrued liability over the value of fund assets. The actuarial accrued liability is the estimated actuarial present value of the cost of all future pension benefits (in excess of employee contributions) attributable to all service to date of current employees, plus all remaining future benefits payable to current retirees and other former employees (and beneficiaries) entitled to benefits.

As of the end of fiscal year 2024, USPS’s estimated actuarial accrued liability for CSRS was $165.5 billion, while its estimated net fund balance was $105.3 billion, for an estimated unfunded liability of $60.2 billion.[86] USPS’s required 2024 amortization payment toward paying down this unfunded liability was $3.2 billion. USPS did not contribute any of this required payment, citing its need to preserve liquidity and also noting that it disputes OPM’s methodology for determining this required payment (discussed further below). As of the end of fiscal year 2024, USPS has an unpaid balance of $17.0 billion for CSRS amortization payments assessed between fiscal years 2017 to 2024.

USPS’s Unfunded Liability for CSRS

As noted above, USPS unfunded liability for CSRS was $60.2 billion as of the end of fiscal year 2024. This unfunded liability will vary from year, positively or negatively, due to a variety of factors, such as

1. the extent to which actual actuarial experience differs from the actuarial assumptions that were used in determining the unfunded liabilities, including with respect to asset returns, inflation, deaths, and other factors;

2. occasional updates to actuarial assumptions based on revised expectations; and

3. the extent to which USPS makes its required contribution.

We projected USPS’s unfunded CSRS liability to isolate the potential impact of USPS’s CSRS amortization payments. Our projections are based on a simplifying assumption that the impact of actuarial experience and assumption updates (which can both be either positive or negative) will net out to zero. This unfunded liability could either increase or decrease depending on the extent to which USPS makes these amortization payments. If USPS pays the required amortization payment in full, its unfunded liability is projected to gradually decline each fiscal year from 2025 through 2031. If USPS continues to not make any of the amortization payments, this unfunded liability is projected to increase (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) Past and Projected Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) Pension Unfunded Liability, Fiscal Years 2007-2031

Note: Alternative scenario assumes USPS makes amortization payments. Values from fiscal years (FY) 2007 through FY 2024 are actual values, and values from FY 2025 through FY 2031 are projected values. USPS’s actual revenue above includes USPS’s interest income. USPS’s revenue projections provided to us for fiscal years 2025 to 2031 do not include a projection of USPS’s interest income.

USPS projects its required CSRS amortization payments will grow from $3.3 billion in fiscal year 2025 to $3.7 billion in fiscal year 2031. Even if USPS paid this amortization payment in full over the next few fiscal years, it could still have an unfunded liability. This is due, in part, to the past-due amortization payments accumulated from fiscal years 2017 to 2024, an amortization period that goes out until fiscal year 2043, and the actuarial factors mentioned earlier that can cause the liability to change from year to year, such as demographic and economic experience and updates to actuarial assumptions.

USPS’s Accounting Treatment for CSRS Costs

USPS files a 10-K report each year that includes a Statement of Operations and a Balance Sheet determined in accordance with applicable accounting standards. USPS accounts for its CSRS obligations using the rules applicable to multi-employer pension plans under the accounting standards of the Financial Accounting Standards Board.[87] In its Statement of Operations, USPS’s required CSRS contributions (whether or not USPS makes full or partial payments) are treated as an operating expense in determining USPS’s net loss (or income) for the year. On its balance sheet, USPS recognizes a liability for its cumulative missed required payments, which are amounts that USPS owes to the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund. As noted earlier, these missed payments (from fiscal years 2017 through 2024) have accumulated to a liability of about $17 billion out of the total retirement benefit liability of about $27 billion USPS reported on its balance sheet for fiscal year 2024 for the combined accumulated missed payments for CSRS and FERS.

In accordance with multi-employer accounting rules, USPS does not recognize this unfunded actuarial liability on its balance sheet. As noted earlier, this unfunded liability was $60.2 billion at the end of fiscal year 2024. Since only the missed payments of about $17 billion are recognized as a liability on the balance sheet, most of this unfunded actuarial liability ($43.2 billion, equal to $60.2 billion, less $17 billion) is not recognized on USPS’s balance sheet.

Controllable Expenses

USPS regards some of its expenses as “controllable” and some not and reports supplemental results on this basis. USPS regards its required amortization payments as a cost outside its control. From an actuarial perspective, this is a reasonable distinction, as USPS’s required amortization payments do not vary with any aspect of USPS’s current operations and reflect cost for benefits earned in the past.

CSRS Allocation Dispute

USPS began operations on July 1, 1971, succeeding the Post Office Department. For employees who worked at both the Post Office Department and USPS, the responsibility for their pension benefits was split between USPS and the rest of the federal government. The methodology for allocating this responsibility is based on a 1974 statute.[88] Under this methodology, the benefit responsibility of the federal government is based on a pension benefit amount calculated using the employee’s length of service and pay as of June 30, 1971, the last day that the Post Office Department existed. USPS is responsible for the growth in the employee’s pension benefit after July 1, 1971, which grows because of additional years of service, as well as pay increases.