BIOSAFETY AND BIOSECURITY

Comparing the U.S. and Selected G20 Members

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional addressees

For more information, contact: Karen L. Howard, PhD, at HowardK@gao.gov

What GAO Found

To understand, prevent, and treat infectious diseases, researchers study biological agents, such as bacteria and viruses. In the U.S., federal agencies have established guidelines to help ensure that U.S. biomedical research labs minimize biosafety and biosecurity risks. Certain principles or “key components” of biosafety and biosecurity may help reduce risks of all biological agents and research. GAO identified 10 key components that describe key steps a U.S. lab should take to mitigate the risks of biological agent research.

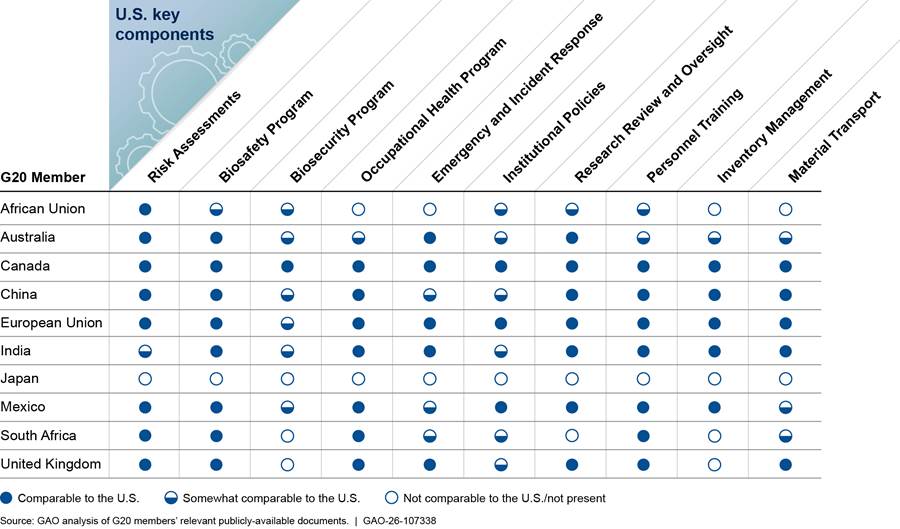

The comparability of the selected Group of Twenty (G20) members’ relevant guidance documents to the 10 U.S. key components varied widely. Nine of the 10 selected G20 members in GAO’s review had documents that were comparable to one or more of the U.S key components for all biological agents and research.

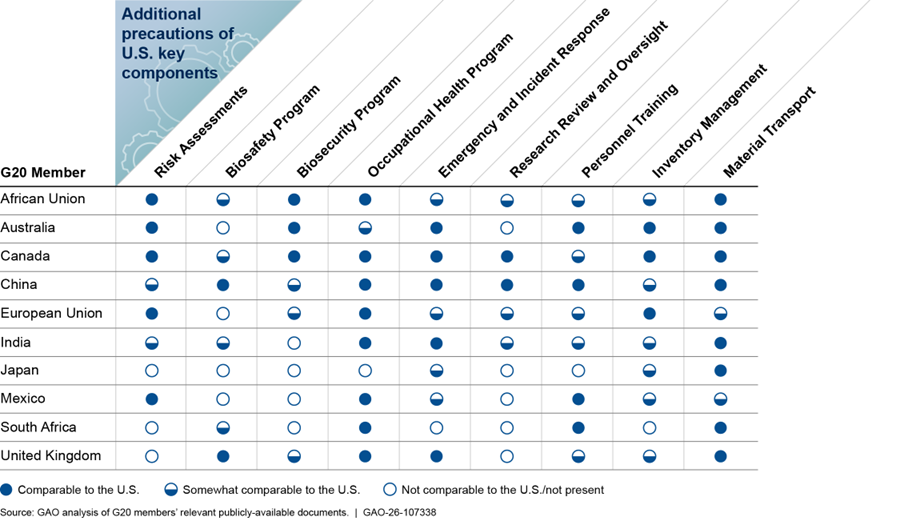

The U.S. key components include additional precautions for specified high-risk agents—such as Ebola virus—and research. Guidance documents from Australia, Canada, and China included comparable language to most of the additional precautions GAO identified for U.S. key components of biosafety and biosecurity.

National guidance documents addressing biosafety and biosecurity are important, but other factors might also influence a G20 member’s biosafety and biosecurity. For example, Australian officials told GAO that state and territory governments play a role in managing biosecurity, such as responding to animal disease outbreaks.

Why GAO Did This Study

Governments use laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines to help achieve goals, such as protecting public health and safety. Biosafety helps protect lab workers, the community, and the environment from accidental exposure to or release of biological agents. Biosecurity helps protect against the loss, theft, deliberate release, or misuse of biological agents.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor federal efforts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. GAO was also asked to compare the biosafety and biosecurity standards of G20 members with U.S. standards. This report examines the extent to which selected G20 members’ publicly available guidance documents reflect (1) selected key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity for all biological agents and research and (2) additional precautions of the U.S. biosafety and biosecurity key components specific to high-risk biological agents and research.

GAO analyzed core U.S. biosafety and biosecurity documents to identify 10 selected key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity for biomedical research labs. For each key component, GAO identified subcomponents or additional precautions for high-risk agents and research.

GAO analyzed selected G20 members’ publicly available guidance documents, such as national laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines. GAO examined whether members’ documents had components that were comparable, somewhat comparable, or not comparable to the 10 U.S. key components. GAO did not evaluate the extent to which each member implements or enforces these documents.

Abbreviations

AU African Union

BSL biosafety level

BMBL Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

DURC dual use research of concern

EU European Union

GMO genetically modified organism

G20 Group of Twenty

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NIH National Institutes of Health

P3CO potential pandemic pathogen care and oversight

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 10, 2026

Congressional Addressees

To understand known and emerging infectious diseases and to develop preventions and treatments against them, researchers study and store biological agents, such as bacteria and viruses.[1] This work helps prevent and treat infectious diseases, but it also poses risks, including accidental exposure to or release of biological agents and their intentional theft or misuse. Incidents involving biological agents could threaten the health of researchers, the community near the incident, or the greater public. Therefore, governments that support research using biological agents have an important role in mitigating the risks that stem from that research by taking steps to help ensure the biosafety and biosecurity of lab research. Biosafety helps protect lab workers, the community, and the environment from accidental exposure to or release of biological agents. Biosecurity helps protect against the loss, theft, deliberate release, or misuse of biological agents.

Governments use laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines to help achieve goals, such as protecting public health and safety. For example, in the U.S., federal statutes, regulations, policies, and guidelines help ensure that U.S. research labs follow practices that minimize biosafety and biosecurity risks, from lower- to high-risk biological agents.[2] Having these in place is an important step for governments toward ensuring biosafety and biosecurity. Other steps include adherence to these documents, a workforce culture of compliance, and enforcement.

Biosafety and biosecurity are important considerations for all biological agents for a variety of reasons. For example, some seemingly low-risk biological agents not known to cause serious disease could naturally evolve or be intentionally modified to do so. In other cases, there may be recently discovered biological agents with little known about their ability to cause disease in humans. Some other biological agents are known to have the potential to pose a severe threat to both human and animal health and are therefore high risk.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor federal efforts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[3] GAO was also asked to compare the biosafety and biosecurity standards of Group of Twenty (G20) members with U.S. standards. This report examines the extent to which selected G20 members’ publicly available guidance documents reflect (1) selected key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity for all biological agents and research and (2) additional precautions of the U.S. biosafety and biosecurity key components specific to high-risk biological agents and research.

We analyzed core U.S. documents to identify 10 selected key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity for biomedical research labs. We identified subcomponents or additional precautions specific to high-risk agents and research of each key component from these documents for comparison.[4] We examined relevant publicly available biosafety and biosecurity guidance documents of the U.S. and 10 selected G20 members.[5] We selected these members using characteristics such as their prevalence of biomedical research and public availability of relevant documents. We compiled and analyzed the 10 G20 members’ relevant publicly available guidance documents, such as national laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines.

We compared the language of these documents to subcomponents or additional precautions of the U.S. key components of biosafety and biosecurity and used subcomponent or additional precaution determinations to assign an overall category of comparable, somewhat comparable, or not comparable/not present for each key component. We did not evaluate the extent to which each member implemented or enforced these documents, nor did we make an evaluation of the strengths or weaknesses of the standards of any member. See appendix I for additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Biosafety and Biosecurity Help Ensure Safe and Secure Handling of Biological Materials

Biosafety is the mechanism for addressing safe handling, containment, and storage of infectious organisms and hazardous biological materials.[6] In the U.S., biosafety guidelines evolved from the research community’s efforts to promote the use of safe practices, safety equipment, and other safeguards that reduce lab infections and protect public health and the environment. Policymakers and researchers continue to refine biosafety practices as new infectious diseases emerge, lab research expands, and emerging technologies introduce new bioterrorism or bioweapon threats.

More recently, policymakers and researchers have developed biosecurity as a related discipline that addresses unauthorized access to and deliberate misuse or release of biological agents and toxins, as well as potential threats to humans, animals, and the environment.[7] Policymakers have revised some biosafety documents to include biosecurity considerations, with modifications such as increasing security to prevent theft, loss, or release of biological materials. (See app. II for selected milestones in the evolution of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity policies.)

The U.S. Tailors Biosafety and Biosecurity to Biological Agent and Research Risks

The U.S. uses multiple federal regulations, policies, and guidance documents to tailor its biosafety and biosecurity precautions and oversight depending on the biological agents being handled and the risks of the specific experiments being conducted. Two guidance documents apply to a broad scope of biological agents and research:

· Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL).[8] Contains comprehensive guidance for biosafety and aspects of biosecurity when working with biological agents, published jointly by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Institutes of Health (NIH). The BMBL is an advisory document that U.S. institutions and labs frequently use as a primary source when developing their own policies, but it is not a regulatory requirement. The BMBL has become the overarching guidance document for the practice of biosafety in the U.S., and it also describes the principles of lab biosecurity. The BMBL provides risk-based recommendations for labs working with a broad range of biological agents.

· NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines).[9] Contains biosafety practices and containment principles for constructing and handling recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules, and cells, organisms, and viruses containing such molecules.[10] Institutions must follow the NIH Guidelines for all recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid research if they receive any NIH funding for such research. We observed significant similarities between the BMBL and NIH Guidelines. However, because the BMBL applies to a broader range of biomedical research labs, we focused on the BMBL for our analyses.

The BMBL defines four primary biosafety levels (BSL) of containment and the standard biosafety and biosecurity measures that should be used at each level to reduce risks when handling a biological agent (see description in table 1). These practices can include facility design features and safety equipment, lab practices and procedures, and personal protective equipment. The BMBL considers factors such as the specific biological agents being handled, potential exposure risks, proposed procedures, and facility capabilities, to help recommend which BSL a researcher should use.[11] As the risks from handling a biological agent increase, higher BSLs specify increasingly stringent safety and security requirements.

|

Biosafety level |

Description |

Sample precaution: safety equipment and standard practices |

|

1 |

Containment appropriate for well-characterized biological agents that are not known to consistently cause disease in healthy adults. |

Lab coats, gloves, eye protection. Work is performed on a lab bench. |

|

2 |

Containment appropriate for moderate-risk biological agents that may cause human disease if accidentally inhaled, swallowed, or exposed to the skin. |

Uses all precautions above, and any procedures that can cause aerosols or splashes are performed in a biological safety cabinet. |

|

3 |

Containment appropriate for biological agents that may be transmitted through the air and cause potentially lethal disease. |

Uses all precautions above, and researchers may be required to wear respirators. All work is performed in a biological safety cabinet. |

|

4 |

Containment appropriate for biological agents that pose a high risk of transmission through the air and may cause life-threatening disease for which no vaccines or treatments are available. |

Uses all precautions above, but researchers may be required to wear a full body protective suit. Labs are airtight and exhaust air is filtered before being released from the lab. |

Source: GAO summary of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories 6th Edition (Bethesda, MD, and Atlanta, GA: revised June 2020) and U.S. HHS, Administration for Strategic Preparedness & Response, Biosafety Level Requirements, https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Pages/Biosafety-Level-Requirements.aspx. Accessed June 18, 2025. | GAO‑26‑107338

Many other countries use a similar system to define different levels of biological containment. Countries that have built or are building BSL-4 labs, or their equivalent, may be of particular interest for comparison, because they either currently have the capacity to work with high-risk biological agents or may have plans to do so. Nineteen countries and one foreign partner (Taiwan) currently have BSL-4 labs, and four countries are planning or constructing BSL-4 labs.[12] Of the 19 countries with operational BSL-4 labs, 13 are G20 members.[13]

In addition to the BMBL and NIH Guidelines, U.S. work on high-risk biological agents is also subject to the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations. These regulations provide requirements for the use and transfer of specific high-risk biological agents that have the potential to pose a severe threat to public health and safety, and animal and plant health or products, subject to legal penalty.[14] HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture are responsible for implementing these regulations using various reporting, inspection, and inventory monitoring requirements.

Policymakers have also developed oversight policies to address the risks that arise from some experiments with biological agents, such as experiments that could change an agent’s ability to spread or cause disease. For example, policies on dual use research of concern (DURC) address life sciences research that can be reasonably anticipated to provide knowledge, information, products, or technologies that could be directly misapplied to pose a significant threat with broad potential consequences to public health and safety, agricultural crops and other plants, animals, the environment, materiel, or national security.[15] In addition, a policy on potential pandemic pathogen care and oversight (P3CO) applies to federally funded research that is anticipated to create, transfer, or use enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.[16]

Ten Key Components of U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity

We identified 10 key components of biosafety and biosecurity that describe key steps a U.S. lab should take to mitigate the risks of biological agent research. The full text of the 10 key components, including the detailed subcomponents that apply to all biological agents and research, are in table 2. 3. Biosecurity Program

|

1. Risk Assessments |

|

|

|

· Before any research project starts, institutions should conduct a risk assessment to identify the hazardous characteristics of an agent or toxin, activities that may result in human exposure, likelihood that exposure will cause an infection, and probable consequences of an infection.a,b · Institutions should use risk assessments to select appropriate mitigations, including the application of biosafety levels and good microbiological practices, safety equipment, and facility safeguards that can help prevent laboratory-associated exposures and infections. · Qualified individuals, such as biosafety professionals or subject matter experts, and institutional review entities, should review risk assessments, and institutions should regularly update risk management strategies to address evolving risks. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

· Institutions should develop and implement a biosafety program that identifies hazards and specifies mitigation strategies to eliminate or reduce the likelihood of exposures and unintentional releases of hazardous materials, including appropriate decontamination methods, good microbiological practices and procedures, and personal protective equipment. · Institutions should develop the biosafety plan in consultation with the facility director and safety professionals, and the plan should be available, accessible, and periodically reviewed and updated as necessary. · Biosafety programs should incorporate various control and containment measures, including infrastructure design, access restrictions, personnel training, containment equipment, and safe methods for managing infectious material. |

||

|

3. Biosecurity Program |

|

|

|

· Institutions should conduct a site-specific risk assessment and analyze the probability and consequences of loss, theft, and potential misuse of materials, technology, or information. Institutions should use this risk assessment to inform their biosecurity program and routinely review and revise the risk assessment and program, including following any laboratory biosecurity-related incident. · Laboratory biosecurity programs should include procedures for personnel vetting, personnel reliability evaluations, violence prevention programs, laboratory biosecurity training, dual use research oversight, cybersecurity standards, material and facility control, and accountability standards. |

||

|

4. Occupational Health Program |

||

|

· Institutions should have an occupational health program that aims to alleviate the risk of adverse health consequences due to potential exposures to biohazards in the workplace. This program should be developed in consultation with individuals with the appropriate clinical expertise and be based on the needs of individual staff and the research risk assessment. |

||

|

5. Emergency and Incident Response |

||

|

· Institutions should have a written plan that describes the biosafety and containment procedures and protocols that personnel should take in the event of an emergency, including exposures and other incidents. Laboratory policies should consider situations that may require emergency responders or public safety personnel to enter the facility in response to an accident, injury, or other safety issue or security threat, and procedures should be developed to minimize the potential exposure of responders to potentially hazardous materials. · Incidents that result in potential exposure to infectious materials should be immediately reported to the occupational health care provider, who should notify the laboratory supervisor and safety staff, if they have not already been notified. · A chain-of-notification should be established in advance of an actual event and should include laboratory and program officials, institution management, and any relevant regulatory or public authorities. |

||

|

6. Institutional Policies |

|

|

|

· Institutions that work with infectious agents and toxins should have an appropriate organizational and governance structure to ensure compliance with biosafety, biocontainment, and laboratory biosecurity regulations, policies, and guidelines, and to communicate risks. · Institutions should establish policies for handling sensitive information, including facility security plans, newly developed technologies or methodologies, and inventories to ensure data integrity, protect information from unauthorized release, and ensure that appropriate levels of confidentiality are preserved. |

||

|

7. Research Review and Oversight |

||

|

· Institutions should have a biological safety professional, subject matter experts, or an institutional biosafety committee or equivalent resource that helps review and oversee research projects and recommends appropriate safeguards to address biosafety and biosecurity risks. |

||

|

8. Personnel Training |

|

|

|

· Institutions should ensure that all laboratory personnel receive adequate training on good microbiological practices, hazard identification, and procedures to ensure safety, minimize exposures, and deal with incidents. |

||

|

9. Inventory Management |

|

|

|

· Institutions should establish material accountability procedures to track the inventory of biological materials and toxins; as well as the storage, use, transfer, and destruction or inactivation of dangerous biological materials prior to transport outside a facility or when no longer needed. |

||

|

10. Material Transport |

|

|

|

· Institutions should develop material transport policies. These should include accountability measures for the movement of materials within and outside an institution, and should address the need for appropriate documentation and material accountability and control procedures for biological materials and toxins in transit between locations. |

||

Source: GAO analysis of selected biosafety and biosecurity recommendations for biomedical and microbiological laboratories, from the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, BMBL 6th Edition (Bethesda, MD, and Atlanta, GA: revised June 2020). cdc.gov/labs/pdf/SF__19_308133-A_BMBL6_00-BOOK-WEB-final-3.pdf. | GAO‑26‑107338

Note: GAO identified these components for the purposes of comparing biosafety and biosecurity documents across selected G20 members. They are not exhaustive, and we have paraphrased them for brevity and for the purpose of comparison. They should not be understood to imply that other elements of biosecurity and biosafety are not similarly important.

aU.S. laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines refer to a variety of entities with responsibilities in the context of biosafety and biosecurity. However, for the purposes of this comparison between the U.S. and selected G20 members, we use the term “institutions” for the broad set of entities including principal investigators, facilities, responsible officials, institutional review entities, and institutional biosafety committees.

bFor the purposes of this report, a biological agent is a microorganism or infectious substance capable of causing specified effects including death or disease in a human and a toxin is the toxic material or product of plants, animals, microorganisms, or infectious substances, as defined at 9 C.F.R. § 121.1 and 42 C.F.R. § 73.1.

Additional Precautions for High-Risk Biological Agents and Research

For nine of the key components, we also identified additional precautions specific to high-risk biological agents covered by the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations, and high-risk research covered by the DURC policies. The additional precautions include provisions that enhance the key components from the BMBL (see table 3).[17] We considered the additional precautions separately from the BMBL key components because the additional precautions apply to a smaller set of high-risk biological agents and research, and because improper handling of high-risk biological agents and research may have more severe consequences.

|

1. Risk Assessments |

|

|

|

¨ For certain types of research using biological agents and toxins that pose specific risks to public health and national security, institutions should identify the risks associated with the potential misuse of information, technologies, or products generated from research, including how information, technologies, or products could be misused.a,b ¨ For certain types of research using biological agents and toxins that pose specific risks to public health and national security, institutions should develop and implement a risk mitigation plan that ensures research is conducted and communicated responsibly. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals or entities must develop and implement a biosafety plan that must be submitted to federal officials for initial registration and renewal of registration.c Institutions must annually review the plan and conduct drills to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness. |

||

|

3. Biosecurity Program |

|

|

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, individuals must undergo a security risk assessment and receive approval from the relevant government officials before being allowed to access any high-risk agent or toxin. · For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals or entities must develop and implement a written security plan that is sufficient to safeguard against unauthorized access, theft, loss, or release.c |

||

|

4. Occupational Health Program |

||

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, all individuals with access to certain high-risk agents and toxins must be enrolled in the institution’s occupational health program. |

||

|

5. Emergency and Incident Response |

||

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals or entities must develop and implement an incident response plan based on a site-specific risk assessment that describes response procedures for the theft, loss, or release of an agent or toxin, security breaches, and other specified natural and human-made events.c · For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals and entities must immediately notify the relevant government agencies of an occupational exposure, theft, loss, or release.c |

||

|

7. Research Review and Oversight |

||

|

¨ Institutions should notify the institutional review entity and federal funding agency for their review and evaluation, if their research using biological agents and toxins may pose specific risks to public health and national security. ¨ For certain types of research using biological agents and toxins that pose specific risks to public health and national security, institutions should provide annual progress reports to the federal funding agency for review and evaluation. · For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, institutions must ensure that annual inspections are conducted for each registered space where high-risk agents or toxins are stored or used, and deficiencies must be documented and corrected. Specified federal entities must be allowed to inspect any site without prior notification. |

||

|

8. Personnel Training |

|

|

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals and entities must provide annual biosafety and biosecurity training in specified areas to anyone with approval to access high-risk agents or toxins.c |

||

|

9. Inventory Management |

|

|

|

· For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals or entities must maintain an accurate, current inventory including specific information for each high-risk agent held in long-term storage, each toxin, and any animals or plants exposed or infected with a high-risk agent or toxin.c · For research involving high-risk agents and toxins, required individuals or entities must conduct inventory audits of all affected high-risk agents and toxins in long-term storage upon physical relocation of a collection, upon the departure or arrival of a principal investigator, or in the event of a theft or loss.c |

||

|

10. Material Transport |

|

|

|

· Generally, institutions may only transfer high-risk agents or toxins to another entity or individual registered to possess, use, or transfer that agent or toxin, and must be authorized by the relevant authorities prior to transfer. |

||

u = GAO high-level summary of selected provisions in the U.S. Government, United States Government Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (March 2012) and U.S. Government, United States Government Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (September 2014). Applies to certain types of federally funded life sciences research on biological agents and toxins that pose specific risks to public health, agriculture, food security, the environment, or national security. See U.S. Government, September 2014 DURC Policy, pp. 7-8.

l = GAO high-level summary of selected requirements in 9 C.F.R. part 121 and 42 C.F.R. part 73 for the possession, use, and transfer of select agents and toxins. There may sometimes be additional requirements or exceptions to these requirements either for a subset of agents or toxins, or in certain situations.

Source: GAO analysis of March 2012 DURC Policy, September 2014 DURC Policy, 9 C.F.R. part 121, and 42 C.F.R. part 73. | GAO‑26‑107338

Notes: GAO identified these components for the purposes of comparing biosafety and biosecurity standards across selected G20 members. They are not exhaustive, and we have paraphrased them for brevity and for the purpose of comparison. They should not be understood to imply that other elements of biosecurity and biosafety are not similarly important.

aU.S. laws, regulations, policies, and guidelines refer to a variety of entities with responsibilities in the context of biosafety and biosecurity. However, for the purposes of this analysis we use the term “institutions” for the broad set of entities including principal investigators, facilities, responsible officials, institutional review entities, and institutional biosafety committees for purpose of comparison between the U.S. and selected G20 members.

bFor the purposes of this report, a biological agent is a microorganism or infectious substance capable of causing specified effects and a toxin is the toxic material or product of plants, animals, microorganisms, or infectious substances, as defined at 9 C.F.R. § 121.1 and 42 C.F.R. § 73.1. A high-risk agent and toxin refers to the list of select agents and toxins found in the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations at 9 C.F.R. part 121 and 42 C.F.R. part 73.

cUnless an exemption exists, an individual or entity that possesses, uses, or transports high-risk agents or toxins must register with the requisite government agency and must comply with the requirements in 9 C.F.R. part 121, 42 C.F.R. part 73.

G20 Members’ Documents for All Biological Agents Varied in Comparability to U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity Key Components

Nine of the 10 selected G20 members had publicly available guidance documents that applied to all biological agents and research and included one or more key components that were comparable to those of the U.S. However, their comparability to the U.S. key components varied widely. Although national guidance documents are important, other factors might influence biosafety and biosecurity practices. For example, a lab might follow more robust practices than specified in national documents.

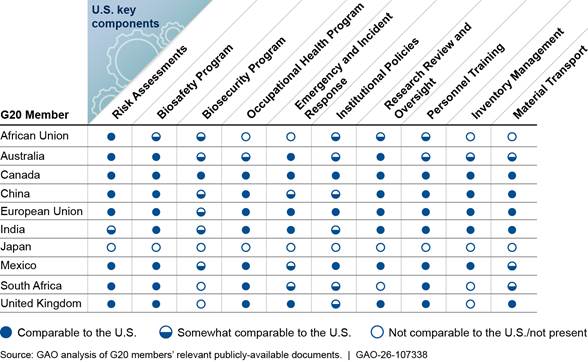

G20 Members’ Documents Included Varying Degrees of Comparability to U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity Key Components for All Agents

We found that the selected G20 members’ guidance documents included language with varying degrees of comparability to the U.S. biosafety and biosecurity key components for all biological agents (see fig. 1). Some key components were more common across all members’ documents than others. For example, nine of the 10 members’ documents included comparable or somewhat comparable language for the Risk Assessment, Biosafety Program, and Personnel Training components. However, we found that documents from three members did not include comparable or somewhat comparable language for the Biosecurity Program component, and documents from four members did not include comparable or somewhat comparable language for the Inventory Management component. Finally, while nine members’ documents included comparable or somewhat comparable language for the Institutional Policies component, five members’ documents did not include comparable or somewhat comparable aspects of the key component related to protecting sensitive information and maintaining research confidentiality.

Figure 1: Extent to Which Group of Twenty (G20) Members’ Publicly Available Documents Contain Language Comparable to Key Components of U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity for All Biological Agents and Research

African Union: Six Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

African Union

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 1 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments 5 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Biosafety Program · Biosecurity Program · Institutional Policies · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training 4 of 10 Not comparable · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Inventory Management · Material Transport Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that the AU’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to six of the 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. For example, for the Biosafety Program key component, the AU’s documents addressed development of a biosafety program based on a risk assessment but did not include specifics on accessibility, review, and updates of the biosafety plan. Additionally, for the Personnel Training component, we identified documents that addressed hazard awareness training for all lab personnel handling biological materials. However, we did not identify training related to other elements, such as good microbiological practices.

Development of other aspects of biosafety and biosecurity in the AU might be underway, convened by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), an AU public health agency. In 2019, Africa CDC launched the Biosafety and Biosecurity Initiative to strengthen biorisk management systems in AU member states. This initiative included a 5-year (2021-2025) strategic plan that focused on coordinating biosafety and biosecurity goals between Africa CDC and AU member states. Officials from Africa CDC told us they are currently developing a follow-up strategic plan. Officials also told us they work with regional and national biosafety and biosecurity associations when developing guidance documents.

The AU is a continental union of 55 member states that, among other goals, aims to accelerate the political integration of the continent and advance its development by promoting research in all fields including science and technology. AU-level biosafety and biosecurity documents provide an opportunity to influence biosafety and biosecurity across its member states.

Australia: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

Australia

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 4 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Research Review and Oversight 6 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Biosecurity Program · Occupational Health Program · Institutional Policies · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that Australia’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. For six of the components, we found Australia’s documents contained language that was somewhat comparable to the U.S. key components because the documents did not include some aspects of the key components. For example, one of Australia’s documents included some text of the Biosecurity Program component, such as development of a biosecurity program to control materials and to restrict access to labs or other facilities where biological agents are handled. However, the document did not address routine review or update of the program. Furthermore, the document lacked key elements of the Biosecurity Program component, such as violence prevention programs and dual use research oversight. Additionally, for the Institutional Policies component, we identified organizational and governance structures for ensuring compliance with biosafety and biosecurity guidelines. However, we did not identify text establishing institutional policies for handling sensitive information and preserving confidentiality.

Differences in the scope of guidance documents between national, state, and territory levels in Australia may explain the lack of detail we found in certain national documents. Australian officials told us that state and territory governments play a role in managing biosecurity (e.g., responding to animal disease outbreaks) under their own legislation.

Canada: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

Canada

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 10 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Biosecurity Program · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Institutional Policies · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that Canada’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research.

China: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

China

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 7 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport 3 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Biosecurity Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Institutional Policies Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that China’s publicly available guidance documents included language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research.[18] We assessed three components as somewhat comparable because the documents did not include some aspects of the key components. For example, for the Biosecurity Program component, we identified text that called for developing and implementing safety and security measures when lab activities involve pathogenic biological agents. However, we did not identify some elements of the Biosecurity Program component, such as personnel vetting, cybersecurity standards, or dual use research oversight. Additionally, for the Institutional Policies component, we identified organizational and governance structures for ensuring compliance with biosafety and biosecurity guidelines. We also identified components establishing institutional policies for handling sensitive information and preserving confidentiality. However, these components did not specify the types of information considered sensitive, such as facility security plans.

European Union: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

European Union

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 9 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Institutional Policies · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport 1 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Biosecurity Program Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that the EU’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. The EU’s documents included one component that we assessed as somewhat comparable because the documents did not include some aspects of the key components. For the Biosecurity Program component, the EU’s documents called for risk assessments and development of a security plan. However, we did not identify certain elements of the Biosecurity Program component, such as violence prevention programs, cybersecurity standards, and dual use research oversight.

The EU is a political and economic union comprised of 27 countries, or member states, that includes among its aims promoting scientific and technological progress. It has varying authorities to influence member states’ laws and policies, including to promote biosafety and biosecurity among its member states, such as through binding directives. EU-level biosafety and biosecurity documents provide an opportunity to influence biosafety and biosecurity across its member states.

India: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

India

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 7 of 10 Comparable · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport 3 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosecurity Program · Institutional Policies Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that India’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. We assessed three components as somewhat comparable because the documents did not include some aspects of the key components. For example, for the Risk Assessment component, India’s documents described the risk assessment process, its connection to the selection of biosafety and containment measures, and oversight from safety personnel. However, the documents did not clearly call for the risk assessment to be conducted before research begins. Further, for the Institutional Policies component, India’s documents included recommendations for institutions to establish policies to govern information handling and distribution. However, the documents did not include detail about what types of information should be considered sensitive, like facility security plans and newly developed technologies.

Japan: No Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

Japan

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 10 of 10 Not comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Biosecurity Program · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Institutional Policies · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management · Material Transport Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that Japan’s publicly available guidance documents did not include any language that was comparable to the 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. While our search identified documents from Japan that addressed biosafety and biosecurity, we found that these documents covered a narrower scope of biological agents than the BMBL. For example, our search identified two documents that we did not include in our analysis because they only applied to research with genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Those documents discussed some research oversight and containment measures, including biosafety levels and facility safeguards for research involving GMOs.[19] Japanese officials told us that these documents do not apply to non-GMO biological agents, but research institutes generally take them into account. However, while we did not identify any documents explicitly addressing biosafety and biosecurity for all biological agents and research, including non-GMO biological agents and research, we did identify guidelines related to high-risk agents and research (see p. 28).

We also identified two biosafety documents published by universities in Japan that were not in the scope of our analysis because they are not government guidance documents but may help mitigate biosafety and biosecurity risks in some research labs.[20] For example, the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University published a Biosafety Manual with information on research project registration and approval, safety equipment, and biological material transport. The University of Tokyo also published an Environment and Safety Guideline that included chapters on biosafety and biological waste handling.

Mexico: 10 Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

Mexico

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 7 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Institutional Policies · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Inventory Management 3 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Biosecurity Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Material Transport Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that Mexico’s publicly available guidance documents included language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to all 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research.[21] We assessed three components as somewhat comparable because the documents did not include some aspects of the key components. For example, for the Biosecurity Program component, Mexico’s documents referenced protecting certain biological materials from theft, misuse, and intentional release, but we did not identify text regarding conducting or reviewing site-specific biosecurity risk assessments. Additionally, for the Material Transport component, Mexico’s documents included accountability measures for the movement of biological materials between institutions but did not address appropriate documentation for those materials during transit.

South Africa: Seven Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

South Africa

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 4 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Personnel Training 3 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Emergency and Incident Response · Institutional Policies · Material Transport 3 of 10 Not comparable · Biosecurity Program · Research Review and Oversight · Inventory Management Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that South Africa’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to seven of the 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. We did not identify any text related to the Biosecurity Program or Inventory Management components and found no comparable text regarding the Research Review and Oversight component.

South Africa’s documents did not include details related to some other key components. For example, for the Emergency and Incident Response component, we identified text addressing development of emergency response plans and notification of occupational health providers and lab supervisors following a potential exposure incident. However, we did not identify text addressing considerations for emergency responders entering a facility, or for notifying regulatory and public authorities following an incident. Additionally, for the Institutional Policies component, we identified text addressing organizational structures to ensure compliance with policies related to health and safety, but we did not identify text calling for organizational structures to ensure compliance with biosecurity guidelines.

United Kingdom: Eight Comparable or Somewhat Comparable Components

|

United Kingdom

Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 7 of 10 Comparable · Risk Assessments · Biosafety Program · Occupational Health Program · Emergency and Incident Response · Research Review and Oversight · Personnel Training · Material Transport 1 of 10 Somewhat comparable · Institutional Policies 2 of 10 Not comparable · Biosecurity Program · Inventory Management Source: GAO (analysis). | GAO‑26‑107338 |

Our analysis found that the United Kingdom’s publicly available guidance documents contained language that was comparable or somewhat comparable to eight of the 10 U.S. key components for all biological agents and research. For the Biosecurity Program component, we did not identify documents that called for developing or implementing biosecurity programs, including those based on site-specific risk assessments. Additionally, for the Inventory Management component, we did not identify documents addressing material accountability procedures for biological materials and toxins, such as processes to track their storage, use, transfer, and destruction. The UK’s documents did not include details for the Institutional Policies component. The UK’s documents addressed having appropriate organizational and governance structures, including for communicating biosafety risks, but did not address the need to establish policies for handling sensitive information or maintaining confidentiality.

Other Factors Might Influence G20 Members’ Biosafety and Biosecurity Practices

National guidance documents addressing biosafety and biosecurity are important, but other factors might also influence biosafety and biosecurity. Examples of these factors include implementation and enforcement of guidance and labs’ workplace culture of biosafety and biosecurity. We did not examine these factors, but it is possible that a G20 member with comparable guidance documents might not apply them in practice or that a member with limited publicly available guidance documents could still have laboratories that follow biosafety and biosecurity practices.

Other nonfederal or nongovernmental institutions might play important roles in providing guidance documents for biosafety and biosecurity, as mentioned above for some G20 members. For example, Australian officials told us that state and territory governments had primary responsibility for responding to animal disease outbreaks and implementing biosecurity measures to contain outbreaks. In other cases, a G20 member’s national documents might focus on providing high-level guidance for institutions, while another entity was responsible for developing more detailed biosafety and biosecurity procedures. For example, we did not identify comparable national biosafety and biosecurity documents for Japan applicable to all biological agents and research but found that two different universities published documents that address biosafety and biosecurity risks in research labs.[22]

Some G20 members’ documents address different risks than U.S. documents address. For example, South Africa and Japan had documents focused on mitigating the risks from creating or releasing genetically modified organisms (GMO), which was not comparable to the broader scope of U.S. documents. Although such documents could help reduce some risks, if a member’s documents exclusively focused on GMOs, the member might not have sufficient guidance or oversight to properly address the risks of certain agents that were not genetically modified and still pose risks.

U.S. Documents Have Additional Precautions for High-Risk Agents and Research, but Few G20 Members’ Documents Were Comparable

U.S. Documents Have Additional Precautions for High-Risk Agents and Research

In the U.S., research using high-risk agents and other defined high-risk research requires additional precautions to help ensure biosafety and biosecurity.[23] This research uses biological agents or lab procedures that pose specific risks to public health and national security. Furthermore, some high-risk agents and research may be used for bioterrorism and biowarfare. Therefore, it is important to take appropriate measures for high-risk agents and research. We describe two categories of such agents and research, and the guidance documents that address additional precautions below.

· High-risk agents, also known as U.S. select agents and toxins. Some specific biological agents and toxins (e.g., Ebola virus, smallpox virus) generally require especially strict precautions for their possession, use, and transfer because they have the potential to pose a severe threat to public health and safety, to animal health, or to animal products. This status is determined by multiple factors, including the ease with which agents are spread, the illness’s severity, and the availability of treatments.[24] In the U.S., these agents and toxins are called select agents and toxins and are subject to additional regulatory oversight of their possession, use, and transfer, due to the risk of deliberate misuse and the potential to cause mass casualties and devastating effects on the economy, critical infrastructure, or public confidence.[25] Additional precautions from the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations include specific reporting, inspection, and inventory monitoring requirements for researchers working with select agents and toxins.

· High-risk research. Additional precautions may also be needed because, based on current understanding, the research may result in dual use research of concern (DURC).[26] In the U.S., the DURC policies call for consistent review and oversight of research within the scope of the policies. Additional precautions based on the DURC policies include specific institutional review to identify risks associated with the misuse of information or technologies generated from research.

Few G20 Members’ Publicly Available Documents Had Comparable Additional Precautions Specific to High-Risk Agents and Research

Three G20 members’ publicly available guidance documents included comparable language to most of the additional precautions we identified for U.S. key components of biosafety and biosecurity. Due to the potential risks of high-risk agents and research, as described above, the distinction between comparable and somewhat comparable language to the additional precautions may be especially important. However, it is possible that some members have additional guidance documents that we did not have access to for these types of agents and research. Some members may not make documents specific to high-risk agents and research publicly available because these documents may be considered sensitive, classified, or proprietary. If that is the case, some members’ documents may have a higher number of additional precautions that are comparable to those of the U.S. than our analysis would indicate.

Guidance documents from three selected G20 members included language that was comparable to at least six out of nine of the U.S. key components for high-risk biological agents and research (see fig. 2). Five members’ documents included language that was a mix of comparable and somewhat comparable to most of the key components. Two members’ documents included language that was not comparable to, or did not contain any language related to, most of the key components.

Figure 2: Extent to Which Group of Twenty (G20) Members’ Publicly Available Documents Include Language Comparable to Additional Precautions of U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity Specific to High-Risk Agents and Research

Reasons for somewhat comparable determinations varied. For example:

· Guidance documents from Australia, Canada, and China included language that was comparable with the additional precautions for six, seven, and six of the nine U.S. key components for high-risk biological agents and research, respectively. However, for the additional precaution of the Biosafety Program key component, Australia’s documents did not include text addressing the development of a biosafety plan for high-risk agents and toxins that is submitted to federal officials for review and approval. Canada’s documents included text addressing the development of a biosafety plan but did not discuss annual review of the plan or conducting drills. For additional precautions of the Biosecurity Program key component, China’s documents discussed development of a security plan to safeguard against unauthorized access, theft, loss, or release of high-risk agents and toxins. However, China’s documents did not address security risk assessments for individuals allowed to access high-risk agents and toxins.

· Guidance documents from the AU, the EU, and India included language that we assessed as somewhat comparable for additional precautions of five key components because the documents did not include specifics. For example, for the additional precaution of the Biosafety Program key component, documents from India and the AU did not address submitting biosafety plans to federal entities when conducting research with high-risk agents. For additional precautions of the Research Review and Oversight key component, these members’ documents did not require progress reports for certain types of high-risk research.

It is possible that some members have additional guidance documents that we did not have access to for high-risk agents and research. However, if G20 members do not provide guidance documents for high-risk agents and research, it could increase biosafety and biosecurity risks, such as nefarious actors gaining access to these biological agents. Further, high-risk agents could be released, accidentally or intentionally, and potentially expose the community if labs do not track materials exposed to high-risk agents (e.g., infected animals and plants) or report lab incidents (e.g., lost infectious agents) in a timely fashion.

Agency Comments, Third-Party Views, and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report for review and comment to State and HHS (including NIH and CDC). The agencies provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. We also provided excerpts of this report to the 10 selected G20 members. Seven provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and the Secretary of State. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Karen L. Howard, PhD, at HowardK@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Karen L. Howard, PhD

Director,

Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Addressees

The Honorable Susan Collins

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Cole

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Andrew Garbarino

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Honorable Raul Ruiz, M.D.

House of Representatives

Objectives

This report examines the extent to which selected Group of Twenty (G20) members’ publicly available guidance documents reflect:

(1) selected key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity for all biological agents and research and

(2) additional precautions of the U.S. biosafety and biosecurity key components specific to high-risk biological agents and research.

Scope and Methodology

Overview

Our review focused on identifying key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity from relevant U.S. guidance documents; identifying publicly available biosafety and biosecurity guidance documents from selected G20 members; and analyzing the extent to which the G20 members’ documents were comparable to the U.S. key components.[27] We also interviewed agency officials and other experts. We compared selected G20 members’ biosafety and biosecurity components to key components of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity to assess whether they were comparable, somewhat comparable, or not comparable. These U.S. key components are selected principles of biosafety and biosecurity that we identified based on U.S. documents that apply to all biological agents and research as well as additional precautions specific to high-risk biological agents and research.[28] The key components, and additional precautions of the key components, paraphrase concepts from U.S. documents to facilitate comparison with G20 members’ documents and are not exhaustive. We did not evaluate the extent to which each member implemented or enforced these documents. In addition, we did not evaluate the relative strengths and weaknesses of each member’s guidance documents and overall approach to biosafety and biosecurity, and our findings should not be read to imply that different approaches to biosafety and biosecurity are either more or less favorable than those of the U.S. After completing our analysis, we offered each selected G20 member an opportunity to review and comment on our results. Additional details on these activities are provided below.

Identifying Relevant, Publicly Available U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity Documents

We searched for relevant U.S. documents on government websites, public databases, legal databases, and in other GAO reports with assistance from GAO research librarians. We identified six key U.S. biosafety and biosecurity documents from these searches:

· Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 6th Edition,[29]

· National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines) April 2024,[30]

· Select Agent and Toxin Regulations (7 C.F.R. part 331, 9 C.F.R. part 121, and 42 C.F.R. part 73),[31]

· 2012 United States Government Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (March 2012 DURC Policy),[32]

· 2014 United States Government Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (September 2014 DURC Policy),[33] and

· 2017 Recommended Policy Guidance for Departmental Development of Review Mechanisms for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (P3CO Policy Guidance).[34]

We selected four of the six key U.S. documents for further analysis: the BMBL, the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations (42 C.F.R. part 73, 9 C.F.R. part 121), the March 2012 DURC Policy, and the September 2014 DURC Policy (DURC policies).[35] We selected the BMBL because it contains recommendations for U.S. biological agent research labs working with all biological agents. We did not select the NIH Guidelines because they apply only to institutions that receive support from NIH for recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid research or research performed directly by NIH.[36] Further, we observed significant overlap in the biosafety and biosecurity guidance in the BMBL and the NIH Guidelines. We also selected the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations and the DURC policies since they specifically apply to high-risk biological agents and research, which we categorized as “additional precautions” in our analyses. We did not include the P3CO Policy Guidance in our analysis of additional precautions for biomedical research labs because it focuses exclusively on federal-level oversight. We shared the key U.S. biosafety and biosecurity documents we identified with agency officials and selected external experts to determine whether there were any documents that we should consider adding to our list.

Identifying Key Components of U.S. Biosafety and Biosecurity

We generated a list of 10 biosafety and biosecurity key components from the BMBL for all biological agents and research, and additional precautions for nine of the key components, based on the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations and DURC policies for high-risk biological agents and research. To facilitate the analyses, we identified subcomponents for each key component based on text elements found within the corresponding key component from the BMBL, the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations, or DURC policies. For example, for the “Risk Assessment” key component we identified three subcomponents with text elements from the BMBL and two additional precautions with text elements from the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations and DURC policies.

Later, we shared the selected U.S. key components, including their additional precautions, with eight experts with in-depth knowledge of the U.S. documents we identified. The eight experts included two of the six external experts mentioned above, plus an additional six experts that we identified using the same methodology as previously noted. We asked the experts to provide feedback on the key components to help ensure they accurately reflected the core aspects of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity. We revised the key components as appropriate based on the experts’ feedback, which did not result in any removal or addition of key components but included relatively minor edits to terminology. When incorporating experts’ feedback, we ensured consistency with the source documents.

Selecting G20 Members for Analysis

The scope of our review focused on identifying and analyzing biosafety and biosecurity components from the most recent publicly available biosafety and biosecurity guidance documents of the U.S. and 10 selected G20 members. These members included the African Union (AU), Australia, Canada, China, the European Union (EU), India, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.[37] We selected these 10 members according to characteristics such as their prevalence of biomedical research based on public reports and public availability of relevant policy documents.[38]

We excluded 10 G20 members from further analysis. We excluded them for one or more of the following reasons: the G20 member is subject to the same guidance documents as other members in our review (e.g., France, Germany, and Italy also observe EU guidance documents); cost and time considerations for translation services for members that did not have publicly available official English versions of their documents; and the priorities of our requesters.

Identifying Relevant, Publicly Available Biosafety and Biosecurity Documents from G20 Members

To identify the most recent, publicly available, national (and international or supranational, in the case of the AU and EU) guidance documents from the selected G20 members, we searched official government websites (e.g., ministries, agencies) that support or oversee biological research laboratories; publications from organizations that work on biosafety or biosecurity (e.g., the Association for Biosafety and Biosecurity); and the World Health Organization’s Joint External Evaluation Tool or the Global Health Security Index country reports.[39]

At our request, the Law Library of Congress (Law Library) conducted a search for publicly available guidance documents from G20 members using biosafety- and biosecurity-related search terms.[40] The Law Library developed and provided a bibliography of G20 members’ biosafety and biosecurity documents.[41] The Law Library also provided a description of how G20 members use the terms “biosafety” and “biosecurity” and how their definitions compare to the U.S. We compared the Law Library bibliography results to our search results to help ensure the completeness of our list of potentially relevant national guidance documents.

To confirm that we correctly identified the 10 selected G20 members’ key biosafety and biosecurity documents, we reached out to relevant officials from the G20 members. We identified and contacted these officials in consultation with the Department of State. If G20 member officials responded, we compared the documents they provided against our previous search results and analyzed any relevant new documents.[42] For those documents where an official English-language translation was not available, we contracted with the Department of State to translate the documents to English.

We then determined whether the selected G20 members’ documents we identified were applicable to similar types of biological agents or research as were covered by U.S. documents. For example, we determined applicability to be similar to the BMBL if the G20 member’s documents generally addressed most or all biological agents and research. However, if a document only applied to a subset of biological agents and research, such as genetically modified organisms, we did not include it in our analysis. We also excluded guidance documents that were in draft form or out of scope, such those pertaining to agricultural crops or hazardous waste. We determined applicability to be similar to the Select Agent and Toxin Regulations or DURC policies if the member’s documents addressed high-risk biological agents and research. Some members’ documents covered the information contained in multiple U.S. documents.

Analyzing the Comparability of G20 Members’ Documents to U.S. Key Components of Biosafety and Biosecurity

We analyzed the biosafety and biosecurity documents from each selected G20 member to determine the extent to which they reflected key components of biosafety and biosecurity that we identified from U.S. documents. For each selected G20 member, an analyst conducted a content analysis of the member’s documents to compare text to the subcomponent or additional precaution text and assigned a comparable, somewhat comparable, or not comparable/not present determination for each subcomponent and additional precaution using the following criteria:

· Comparable. The G20 member’s documents contained all or almost all text elements either as identical or technically equivalent text to the subcomponent or additional precaution.[43]

· Somewhat comparable. The G20 member’s documents contained at least one text element that was identical or technically equivalent to the subcomponent or additional precaution but did not address all parts of the subcomponent or additional precaution.

· Not comparable/not present. The G20 member’s documents either (1) contained text (e.g., a key term) related to the U.S. subcomponent or additional precaution but the details were not relevant or technically equivalent, or (2) did not contain any text related to the subcomponent or additional precaution.

A second analyst reviewed the analysis and comparability determination, and any differences between analysts were discussed and adjudicated. We then reviewed the individual subcomponent and additional precaution determinations to assign an overall component comparability determination based on the following criteria:

· Comparable. All (i.e., one out of one, two out of two) or the majority (i.e., two out of three) of the subcomponent or additional precaution ratings were “comparable.”

· Somewhat comparable. All (i.e., one out of one, two out of two) or the majority (i.e., two out of three) of the subcomponent or additional precaution ratings were “somewhat comparable.” If there were two subcomponents or additional precautions rated “comparable” and “not comparable/not present” then the overall component was rated “somewhat comparable.”

· Not comparable/not present. All (i.e., one out of one, two out of two) or the majority (i.e., two out of three) of the subcomponent or additional precaution ratings were rated “not comparable/not present.”[44]

A legal review of the above analyses was then performed to assess whether the subcomponent and additional precaution determinations were consistent with the language contained in the members’ legal and policy documents as compared to the subcomponent and additional precaution language, and to assess the key component determination resulting from the analysis. We did not verify translations of documents but rather relied on the official English translations we obtained from State or other official sources. We did not review members’ legal systems or analyze information beyond that contained in the members’ relevant guidance documents, nor did we evaluate whether the members’ documents occupied the same position in the structure of the legal system as the U.S. guidance documents. For example, we did not evaluate whether a member’s document containing language discussing an additional precaution that was derived from the U.S. Select Agent and Toxin Regulations was a document with the similar force and effect of a U.S. federal regulation, nor did we differentiate based on requirements versus recommendations in our review.

Interviews with Agency Officials and Other Experts

We interviewed officials from federal agencies primarily responsible for biosafety and biosecurity oversight of U.S. biological agents and research, and federal agencies involved with international biosafety and biosecurity efforts. These included officials from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NIH, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, and Office of Global Affairs; as well as the Department of State’s Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy, and Office of the Special Envoy for Critical and Emerging Technology. In our interviews, we asked officials about their agencies’ roles in the development, oversight, application, or enforcement of U.S. biosafety and biosecurity regulations, policies, and guidelines. We also shared the key U.S. biosafety and biosecurity documents we identified with agency officials to determine whether there were any documents that we should consider adding to our list.

We interviewed six external experts with backgrounds in academia, the private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and global health, regarding U.S. and international biosafety and biosecurity. We identified these six experts through internal GAO subject matter expertise in biosafety and biosecurity, document reviews, prior related GAO interactions, and external expert recommendations. We also asked the experts to identify any governments or international bodies that play a key role in the development or communication of biosafety and biosecurity standards and guidelines.

In addition to these interviews, we obtained written responses to follow-up questions from officials as needed.

Feedback on Results from Selected G20 Members

After completing our analysis, we shared our findings with officials from the 10 selected G20 members to solicit their feedback. We received comments from officials from seven G20 members and incorporated changes as appropriate (see table 3).

|

G20 member |

Member officials provided feedback on documents GAO identified |

Member officials provided feedback on GAO analysis of member’s documents |

|

African Union |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Australia |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Canada |

Yes |

Yes |

|

China |

Yes |

Yes |

|

European Union |

Yes |

Noa |

|

India |

Noa |

Nob |

|

Japan |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mexico |

Nob |

Yes |

|

South Africa |

Nob |

Noc |

|

United Kingdom |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: GAO summary of GAO outreach. | GAO‑26‑107338

aGAO emailed G20 member officials. As of February 2026, GAO had not received a response.

bGAO contacted G20 member via diplomatic note. A diplomatic note is a formal communication between governments. As of February 2026, GAO had not received a response.

cGAO did not contact G20 member officials. In December 2025, State officials told us that it would conflict with U.S. policy toward South Africa to communicate the analysis summary and cover letter to the South African government under the circumstances in effect at that time.