COAST GUARD OVERSIGHT

Actions Needed to Strengthen Collaboration on Investigations

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Heather MacLeod at MacLeodH@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) have some overlapping authorities to investigate complaints regarding the Coast Guard. From October 2018 through May 2024, CGIS investigated at least 4,951 such complaints, and DHS OIG investigated 70 such complaints. CGIS is an independent investigative body within the Coast Guard that primarily conducts criminal investigations related to Coast Guard personnel, assets, and operations. DHS OIG investigates complaints of alleged criminal, civil, and administrative misconduct involving Coast Guard employees, contractors, and programs, among others.

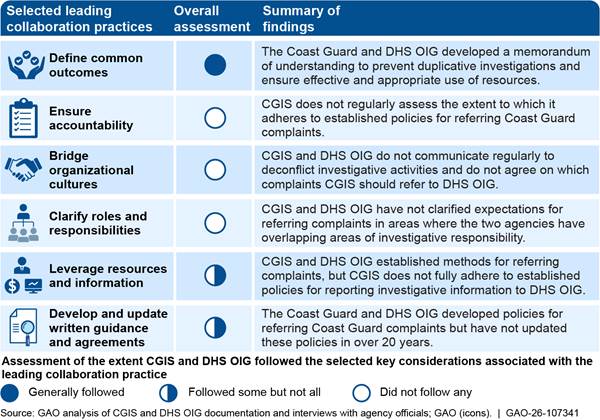

CGIS and DHS OIG identified the need to prevent duplicative investigations, but the two agencies have not fully followed five out of six selected leading practices for collaboration. For example, the agencies have different perspectives on which complaints CGIS should refer to DHS OIG. Fully following these five practices to improve collaboration, consistent with their statutory responsibilities, would better position the agencies to deconflict their investigative activities and ensure effective and appropriate allocation of resources.

Why GAO Did This Study

CGIS and DHS OIG play critical roles in overseeing the Coast Guard—a multi-mission maritime military service within DHS that employs more than 51,000 personnel.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to assess the oversight of Coast Guard activities. This report examines the extent that (1) DHS OIG has processes in place to ensure timely and effective oversight of Coast Guard activities and (2) CGIS and DHS OIG coordinate on complaints, among other things.

GAO evaluated CGIS’s and DHS OIG’s processes for referring Coast Guard complaints to one another against GAO-identified leading practices for collaboration. GAO analyzed CGIS and DHS OIG investigative data, reviewed the 2003 memorandum of understanding and CGIS standard operating procedures, and interviewed CGIS and DHS OIG officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations to the Coast Guard and three recommendations to DHS OIG to, among other things, improve collaboration between CGIS and the OIG. DHS concurred with each of the four recommendations to the Coast Guard. DHS OIG neither agreed nor disagreed with the three recommendations and expressed concern with several aspects of the report. GAO maintains that its findings are accurate and its recommendations remain warranted.

Abbreviations

CGIS Coast Guard Investigative Service

DHS Department of Homeland Security

MOU Memorandum of understanding

OIG Office of Inspector General

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 21, 2026

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. Coast Guard—a multi-mission, maritime military service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) with over 51,000 personnel—is responsible for ensuring the safety, security, and stewardship of more than 100,000 miles of U.S. coastline and inland waterways. Coast Guard responsibilities include detecting and interdicting contraband and illegal drug traffic; enforcing U.S. immigration laws and policies at sea; and enforcing our nation’s laws and regulations related to fisheries and marine protected areas, among other missions.[1] To ensure that it can fulfill its missions and that its personnel operate within standards of conduct, the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) conduct oversight and investigations. CGIS is an independent investigative body within the Coast Guard that primarily conducts criminal investigations related to Coast Guard personnel, assets, and operations. DHS OIG serves as an independent and objective oversight body to prevent and detect fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement in DHS programs and operations—including those of the Coast Guard.[2]

DHS OIG plays a critical role in enhancing Coast Guard accountability by providing information to decision-makers and the public. In June 2021, however, we reported that DHS OIG had not followed several professional standards for federal OIGs and key practices for effective management.[3] We made 21 recommendations to DHS OIG to address management and operational weaknesses. As of August 2025, DHS OIG had implemented about half of these recommendations.[4] Appendix I provides details on the status of these recommendations.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to assess the oversight of Coast Guard activities.[5] This report (1) examines the extent to which DHS OIG has processes in place to ensure timely and effective oversight of Coast Guard activities, and (2) describes the number and types of investigations CGIS and DHS OIG conducted and assesses the extent to which they coordinate on complaints regarding the Coast Guard.[6]

To evaluate the extent to which DHS OIG has processes in place to ensure timely and effective oversight of Coast Guard activities, we assessed DHS OIG’s operations and processes as of August 2025 against selected elements of five standards formulated and adopted by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency in its Quality Standards for Federal Offices of Inspector General (federal quality standards for OIGs).[7] Those standards provide the framework for each OIG to conduct official duties in a professional manner. We selected the standards and associated elements that were relevant to timely and effective oversight. DHS OIG’s Coast Guard oversight work follows the same processes and procedures as its oversight work for other DHS components, and therefore we assessed the OIG’s overarching processes and procedures. Specifically, we assessed DHS OIG’s processes and procedures against the following selected standards and elements:

1. Receiving and reviewing complaints: establish policies and procedures for processing and documenting complaints; ensure high-priority matters receive timely attention; and evaluate complaints against guidance when deciding whether to open an investigation.

2. Planning and coordinating: coordinate oversight activities internally and maintain a risk-based work planning approach.

3. Managing human capital: ensure that staff meet continuing professional education requirements; utilize staff members who possess requisite skills; and assess staff members’ skills and determine the extent to which they collectively possess the professional competence to perform assigned work.

4. Maintaining quality assurance: participate in external quality assurance reviews and maintain a quality assurance program.

5. Communicating results of OIG activities: OIG reports should be timely.

To complete our assessment against these standards, we analyzed documents such as DHS OIG directives, guidance, and internal reports. We also interviewed officials from DHS OIG program offices and mission support offices to obtain information on policy and procedure topics relevant to their respective functions.

In addition, for the first objective, we obtained and analyzed DHS OIG data on its oversight projects and recommendations the OIG made to the Coast Guard.[8] Specifically, we analyzed OIG project data for unclassified projects that resulted in a published report or were ongoing from fiscal years 2019 through 2024—the five most recent fiscal years for which complete data were available at the time of our analysis. We analyzed data elements related to time frames for completing projects and the DHS components under review to determine whether the OIG was meeting its timeliness benchmarks. We also analyzed data on OIG recommendations to the Coast Guard from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. We analyzed data elements on whether the Coast Guard had addressed each recommendation and time frames for addressing closed recommendations.

To assess the reliability of DHS OIG’s project and recommendation data, we analyzed documentation about the data and data system, including a data dictionary and user guides. We also interviewed relevant DHS OIG officials and reviewed written responses to understand internal controls and any known data limitations. We performed electronic testing and manual reviews for obvious errors in accuracy and completeness. When our electronic testing or manual reviews of the data identified potential concerns, such as missing data or potential data entry errors, we consulted with DHS OIG officials and made corrections to the data, as needed, based on information officials provided. After taking these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable to analyze the status of DHS OIG recommendations to the Coast Guard and that some of the data were sufficiently reliable to assess DHS OIG’s timeliness for completing projects. We excluded from our analysis data elements that were not sufficiently reliable.

To describe the number and types of investigations CGIS and DHS OIG conducted on Coast Guard activities, we obtained and analyzed CGIS and DHS OIG investigative data from October 1, 2018, (beginning of fiscal year 2019) through May 31, 2024, the most recent available data at the time of our analysis. To assess the reliability of CGIS’s and DHS OIG’s investigative data, we analyzed documentation about the data and case management systems, including privacy impact assessments, data dictionaries, and user guides. We also interviewed relevant CGIS and DHS OIG officials to understand which internal controls were in place and any known data limitations. We performed electronic testing and manual reviews for obvious errors in accuracy and completeness. When our electronic testing or manual reviews of the data identified potential concerns, such as missing data or potential data entry errors, we consulted with CGIS and DHS OIG officials and made corrections to the data, as needed, based on information officials provided. After taking these steps, we determined that some of the CGIS and DHS OIG investigative data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing the number and types of investigations the agencies conducted. We excluded from our analysis data elements that were not sufficiently reliable.

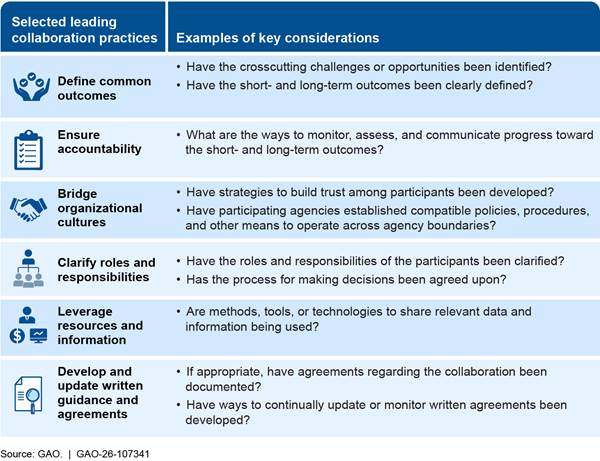

To evaluate the extent to which CGIS and DHS OIG collaborate on Coast Guard complaints, we assessed the agencies’ collaborative efforts against six of eight leading practices for collaboration identified in our prior work: (1) define common outcomes; (2) ensure accountability; (3) bridge organizational cultures; (4) clarify roles and responsibilities; (5) leverage resources and information; and (6) develop and update written guidance and agreements.[9] We also determined that the information and communication component of internal control was significant to this evaluation, along with the underlying principle that management should communicate relevant and quality information with appropriate external parties regarding matters impacting the functioning of the internal control system.[10]

We reviewed documentation related to CGIS and DHS OIG roles and responsibilities for retaining and referring Coast Guard complaints, including a 2003 memorandum of understanding between the Coast Guard and the OIG, DHS-wide directives, and each agency’s internal guidance for adhering to the memorandum and DHS directives. Further, we interviewed CGIS and DHS OIG officials to obtain information on policy and procedures topics relevant to their respective investigative functions.

For more details on our scope and methodology, see appendix II.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. These standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

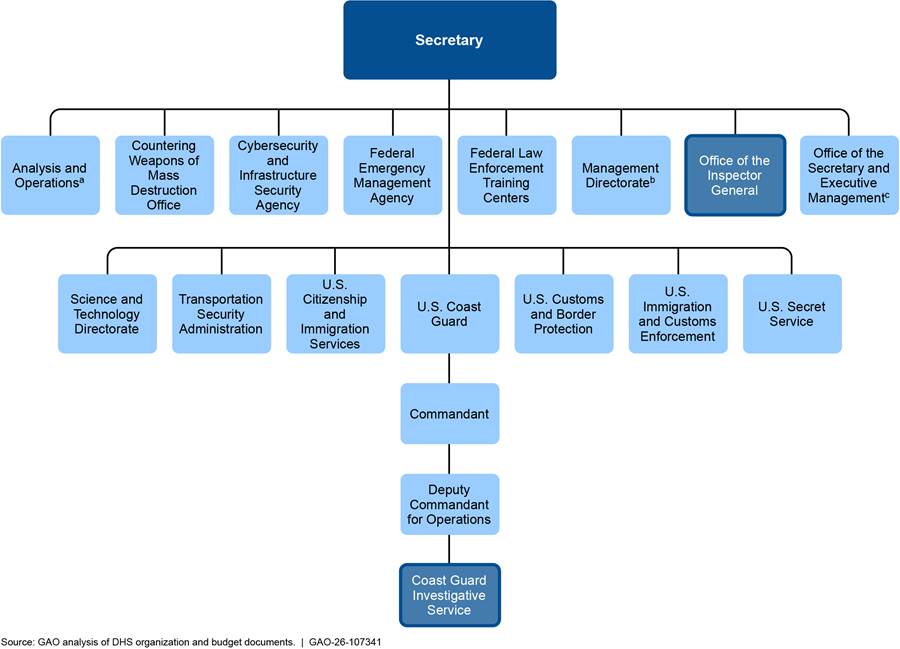

DHS Organizational Structure

The CGIS Director leads CGIS as the senior federal criminal investigative executive within the Coast Guard, and the DHS Inspector General leads the OIG. CGIS is organized as an independent investigative body under the Coast Guard’s Deputy Commandant for Operations, as shown in figure 1. The DHS Inspector General serves under the general supervision of the Secretary of Homeland Security, as shown in figure 1, with a dual reporting responsibility to the Secretary of Homeland Security and to Congress.[11]

Note: The Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and the DHS Office of Inspector General have some overlapping authorities to investigate complaints regarding the Coast Guard. CGIS is one example of a component internal investigative office within DHS components—like Offices of Professional Responsibility—with the authority to investigate allegations of internal misconduct.

aAnalysis and Operations includes the Office of Intelligence and Analysis and the Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness.

bThe Management Directorate includes the Immediate Office of the Under Secretary for Management, the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer, Office of the Chief Procurement Officer, Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management, Office of the Chief Readiness Support Officer, Office of the Chief Security Officer, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Office of the Chief Information Officer, Office of Biometric Identity Management, and the Federal Protective Service.

cThe Office of the Secretary and Executive Management includes the Office of the Secretary; Office of Partnership and Engagement; Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans; Office of Public Affairs; Office of Legislative Affairs; Office of the General Counsel; Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; Privacy Office; Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman; Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman; and the Office of Health Security.

DHS OIG Roles and Responsibilities

DHS OIG conducts and supervises audits, inspections, evaluations, and investigations of DHS programs and operations, including those of the Coast Guard. The OIG may make recommendations to the department and its components for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of those programs and operations.

DHS OIG includes three offices (program offices) whose primary mission is to directly conduct oversight of DHS components, programs, and activities, as shown in table 1. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that each OIG is to conduct its work in compliance with applicable professional standards, also shown in table 1.

Table 1: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Program Offices and Professional Standards for OIG Work

|

DHS OIG Program Office |

Type of OIG Work |

Professional Standard |

|

Office of Auditsa |

Plans, conducts, and reports the results of performance audits, attestation engagements, financial audits, grants audits, and evaluations across DHS and its components. |

Audits are to comply with Government Auditing Standards. These standards provide a framework for conducting high-quality projects and contain requirements and guidance dealing with ethics, independence, professional judgement and competence, quality control, conducting the project, and reporting, among others. |

|

Office of Inspections and Evaluations |

Plans, conducts, and reports the results of inspections, evaluations, and reviews that assess the design and implementation of DHS operations, programs, and policies to determine their efficiency, effectiveness, impact, and sustainability. |

Inspections and evaluations are to comply with the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency’s Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluationb or other appropriate professional standards.c |

|

Office of Investigations |

Investigates allegations of criminal, civil, and administrative misconduct involving DHS employees, contractors, grantees, and programs. Investigations may result in criminal prosecutions, fines, civil monetary penalties, administrative actions, and personnel actions. |

Investigations are to comply with the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency’s Quality Standards for Investigations, consistent with applicable Department of Justice guidelines and case law. |

Source: GAO analysis of professional standards and DHS OIG documentation. | GAO‑26‑107341

aThe Office of Audits also conducts work according to the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency’s Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluation.

bAccording to the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, the inspection and evaluation standards are flexible and not overly prescriptive by design. The standards are meant to be interpreted through the professional judgment of inspectors as they make decisions involved in conducting inspection or evaluation work.

cOfficials from the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency told us that other appropriate professional standards could include an OIG policy or other internal standard to describe the specific steps under which the work was planned and completed.

In addition to these three program offices, DHS OIG’s Office of Integrity manages the OIG’s quality control and quality assurance program, which evaluates the OIG’s work against internal policies and procedures and external professional standards.[12] Within the Office of Integrity, the Investigations Quality Assurance Division conducts inspections of OIG investigative offices and DHS component internal affairs offices—including CGIS—to assess compliance with agency policies and applicable investigative guidelines. For example, in June 2017, DHS OIG inspected CGIS’s organizational management and investigative work.[13] As a result, DHS OIG made 32 recommendations.[14] In July 2025, DHS OIG initiated an ongoing inspection of CGIS.

In DHS OIG’s work, the Coast Guard could be the primary component under review or be included as one of multiple DHS components under review. For example, the Coast Guard was the primary component under review when DHS OIG evaluated the extent to which the Coast Guard had been interdicting vessels suspected of drug trafficking.[15] The Coast Guard has also been included as one of multiple DHS components for department-wide reviews, such as when DHS OIG evaluated the extent to which DHS complied with National Instant Criminal Background Check System requirements.[16]

CGIS Roles and Responsibilities

CGIS is responsible for conducting criminal investigations into complaints of felony violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (e.g., sexual assault and harassment, homicide, desertion, fraud, misappropriation of government property, and illegal activities related to narcotics).[17] It is also responsible for investigating crimes on the high seas and within the Special Maritime and Territorial Jurisdiction of the United States (e.g., migrant and drug smuggling, violations of environmental laws, and terrorism).[18] In addition, Coast Guard commands may request that CGIS assist with administrative investigations (e.g., alleged misconduct that does not rise to the level of a felony violation).[19]

CGIS and DHS OIG Complaint Intake Processes

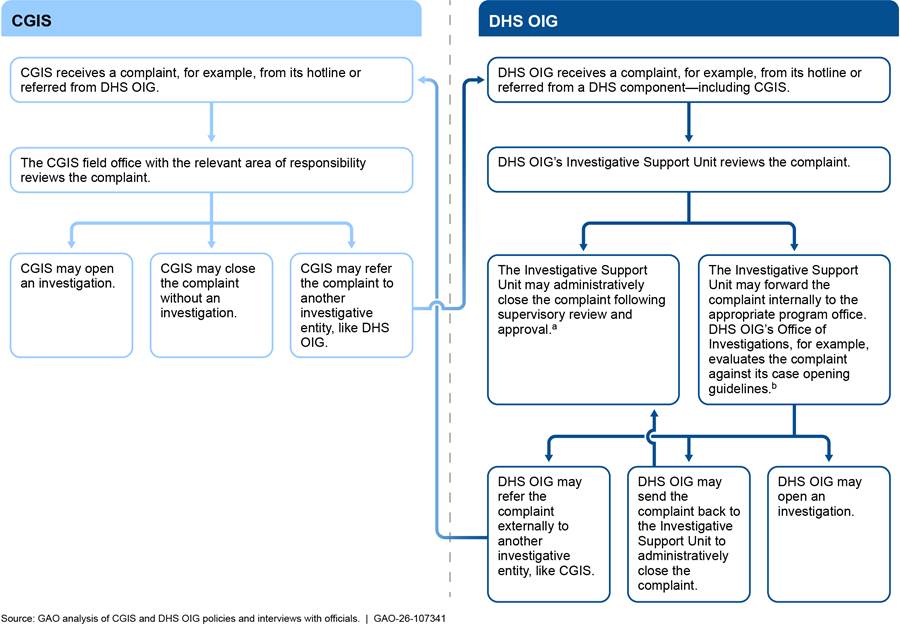

CGIS and DHS OIG both operate complaint hotlines to facilitate reporting criminal allegations involving Coast Guard personnel, programs, and operations, including allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse. In addition to these web-based and mobile hotlines, CGIS and DHS OIG can receive complaints in other ways, such as in-person and via email. As part of its complaint intake process—as shown in figure 2—CGIS reviews complaints to identify which to refer to DHS OIG.[20]

In May 2023, DHS OIG developed case opening guidelines to review complaints, identify those that align with its investigative priorities (e.g., complaints alleging misconduct related to high-value fraud and criminal corruption), and decide whether to open an investigation. According to DHS OIG officials, if a complaint does not align with the OIG’s investigative priorities, the OIG may refer the complaint externally, including to CGIS, as shown in figure 2. DHS OIG may also forward a complaint internally. For example, DHS OIG may forward a complaint to its Whistleblower Protection Division, which investigates complaints of alleged whistleblower retaliation made by any DHS employee, former employee, contractor, subcontractor, grantee, applicant, or member of the Coast Guard.[21]

Figure 2: Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Complaint Intake Process

aDHS OIG officials told us that the OIG can administratively close complaints under limited circumstances, including duplicate complaints, when the complaint will be assumed under an existing investigation, and when the information provided is nonsensical.

bDHS OIG implemented case opening guidelines in May 2023 to review complaints, identify complaints that align with the OIG’s investigative priorities, and decide whether to open an investigation.

Leading Collaboration Practices

In prior work, we have identified eight leading practices to help agencies collaborate and coordinate their efforts, as well as key considerations for collaborating entities to use when incorporating the leading practices.[22] For this review, we selected six of the eight collaboration leading practices as relevant to CGIS and DHS OIG investigative activities, as shown in figure 3.[23] These leading practices are relevant because CGIS and DHS OIG have overlapping authorities to investigate certain Coast Guard complaints.

DHS OIG Has Taken Steps to More Fully Follow Federal Quality Standards and is Not Meeting Its Timeliness Goals for Coast Guard Oversight

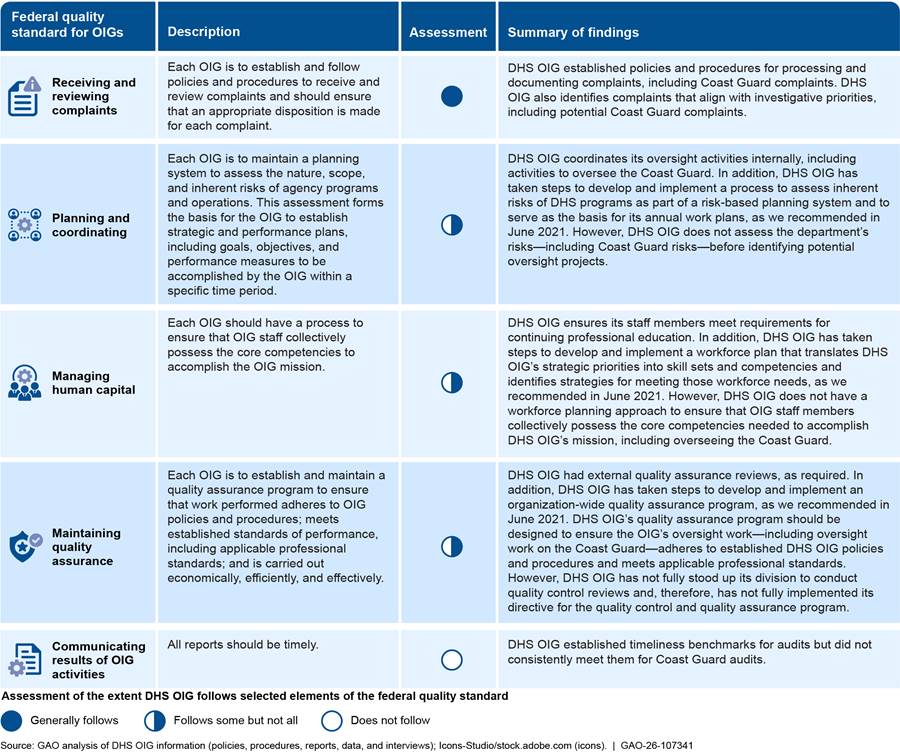

Federal quality standards for OIGs are designed to guide OIGs’ conduct and help ensure timely and effective operations—like Coast Guard oversight activities. DHS OIG generally follows selected elements of one federal quality standard, pertaining to receiving and reviewing complaints. In addition, DHS OIG has taken steps to address management and operational weaknesses that we identified in June 2021 related to federal quality standards for OIGs.[24] However, DHS OIG follows some or does not follow selected elements of the four remaining federal quality standards, related to (1) planning and coordinating, (2) managing human capital, (3) maintaining quality assurance, and (4) communicating results of OIG activities. Figure 4 depicts the extent to which DHS OIG follows the five federal quality standards regarding its Coast Guard oversight activities and reflects examples where the OIG has addressed our June 2021 recommendations.

Figure 4: GAO Assessment of the Extent to Which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Follows Selected Federal Quality Standards for OIGs

Note: We evaluated DHS OIG’s policies and procedures against these five of nine federal quality standards for OIGs as they are most relevant to effective and timely oversight of Coast Guard activities. In June 2021, we reported that DHS OIG had not followed six federal quality standards for federal OIGs and key practices for effective management. We made 21 recommendations—three of which are included in this figure—to DHS OIG to address management and operational weaknesses. GAO, DHS Office of Inspector General: Actions Needed to Address Long-Standing Management Weaknesses, GAO‑21‑316 (Washington, D.C.: June 3, 2021).

Following is our assessment of the extent to which DHS OIG follows elements of federal quality standards for OIGs. These standards apply to all of the OIG’s oversight work, including its oversight of Coast Guard activities.

DHS OIG Receives and Reviews Complaints to Identify Those that Align with Investigative Priorities

DHS OIG generally follows selected elements of the federal quality standard for receiving and reviewing complaints. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that each OIG shall establish policies and procedures for processing complaints, documenting each complaint, and ensuring that urgent and high-priority matters receive timely attention. In addition, federal quality standards for investigations state that each complaint must be evaluated against guidance for disposition decisions (e.g., whether DHS OIG opened an investigation).

Establish Policies and Procedures. DHS OIG’s special agent handbook includes policies and procedures for processing and documenting complaints, including Coast Guard complaints. We reviewed the handbook and determined that it reflects steps for managing DHS OIG’s complaint hotline and forwarding complaints to the office that covers the relevant areas of responsibility. In addition, DHS OIG documents each complaint in its electronic case management system. The case management system assigns a unique reference number to each complaint. The system enables DHS OIG to track key information, including when the OIG refers a complaint externally—like to CGIS—as well as the OIG’s disposition decisions.

Guidance for Opening Priority Complaints. In addition to the special agent handbook, DHS OIG developed case opening guidelines to review complaints, identify complaints that align with the OIG’s investigative priorities—including potential Coast Guard complaints—and make a disposition decision. DHS OIG officials told us that the case opening guidelines help them to take timely, appropriate action on complaints that align with the OIG’s investigative priorities. According to the case opening guidelines, investigative priorities include complaints alleging misconduct related to major fraud (e.g., contract or grant value over $2 million), criminal corruption, civil rights violations, and national security.

According to DHS OIG officials, they first started using the case opening guidelines in May 2023. DHS OIG had a performance metric for fiscal year 2024 to open 80 percent of all investigations under the case opening guidelines. According to DHS OIG, it met that goal and opened 97 percent of its investigations under the guidelines.

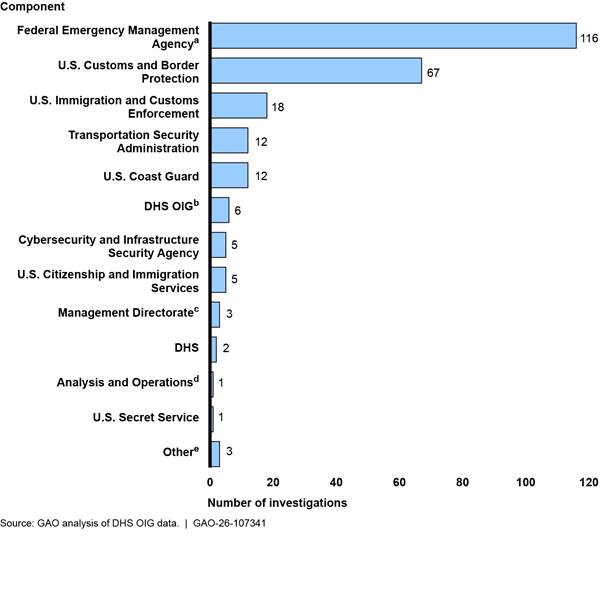

Our analysis of DHS OIG data shows that from October 1, 2023—the beginning of fiscal year 2024, which was the first full fiscal year in which DHS OIG used the case opening guidelines—through May 31, 2024, DHS OIG initiated 251 investigations, as shown in figure 5.[25] Of these 251 investigations, DHS OIG initiated 12 Coast Guard investigations. DHS OIG opened six of these 12 Coast Guard investigations under the case opening guidelines related to financial crimes, including alleged fraud, corruption, and bribery. The remaining six Coast Guard investigations were related to allegations of whistleblower retaliation.[26]

Figure 5: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Investigations Initiated by Component, October 1, 2023–May 31, 2024

aAccording to DHS OIG officials, the number of investigations they initiated on the Federal Emergency Management Agency were related to that agency’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as major disaster and emergency declarations.

bDHS OIG’s Special Investigations Division investigates complaints related to alleged misconduct by DHS OIG employees, among other complaints.

cThe Management Directorate includes the Federal Protective Service, the Office of Biometric Identity Management, and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, among other offices.

dAnalysis and Operations includes the Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness and the Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

eOther investigations include, for example, investigative activities related to former DHS personnel or DHS OIG investigative support to another agency.

DHS OIG Follows Some Standards for Coordinating Its Work and Implementing a Risk-Based Work Planning Approach

DHS OIG follows some selected elements of the federal quality standard for planning and coordinating its work. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that OIG staff are to coordinate their activities internally to assure effective and efficient use of available resources. Federal quality standards for OIGs also state that each OIG shall maintain a work planning approach that starts with an assessment of the nature, scope, and inherent risks (i.e., weaknesses in areas that involve substantial resources and provide critical services to the public) of programs, operations, and management challenges of the agency for which the OIG provides oversight. This risk assessment is to inform the OIG’s annual work plan that identifies and prioritizes its oversight work.

After assessing risks of agency (e.g., DHS) programs and operations, federal quality standards for OIGs direct OIGs to develop a methodology and process for prioritizing agency programs and operations as potential subjects for audit, inspection, evaluation, and investigation. OIGs are then to use an annual planning process to identify oversight activities. The work plan should include considerations of prior oversight work and the department’s efforts to address recommendations. The work plan should also document the OIG’s determination for how it chose among competing needs. DHS OIG posts its annual work plans on its website.[27]

Risks associated with Coast Guard programs and operations include cybersecurity risks. For example, the U.S. Maritime Transportation System is an essential element of the nation’s critical infrastructure, handling more than $5.4 trillion in goods and services annually.[28] The Coast Guard is responsible for assessing risks to this system, establishing and implementing programs for addressing those risks, and facilitating the exchange of threat information with system owners and operators. In July 2024, DHS OIG reported that the Coast Guard should take additional steps to secure the Maritime Transportation System against cyberattacks, such as completing and publishing cybersecurity-specific regulations.[29] Additionally, information security has been on our High-Risk List since 1997, and we expanded this area to include the protection of critical cyber infrastructure in 2003.[30] We have previously reported that the Coast Guard could take further action to mitigate cybersecurity risks.[31]

Internal Coordination. According to DHS OIG policies and officials, leaders from the OIG’s program offices meet monthly to discuss proposed oversight projects and planned work, including Coast Guard projects. DHS OIG officials told us that they use these monthly engagement planning meetings to deconflict projects and share information related to congressional requests, emerging risks, and hotline complaints. Specifically, officials discuss any indicators of potential systemic issues from hotline complaints—such as allegations of misconduct related to civil rights and civil liberties, serious mismanagement, and dangers to public health and safety. During the monthly engagement planning meetings, program office officials review these complaints and decide whether to pursue further oversight on the potential systemic issues.

Work Planning Approach. In response to our June 2021 recommendation, DHS OIG has taken steps to implement a work planning approach that, consistent with federal quality standards for OIGs, would assess DHS’s programmatic and operational risks—including Coast Guard risks.[32] DHS OIG created an internal dashboard tool, which they demonstrated to us in October 2022, that includes information connected to risk, such as budgetary information and past OIG work. As of January 2025, DHS OIG officials told us that staff were using the information to plan individual project proposals, which are then assigned a risk value using a rubric. The principal deputy inspector general and chief of staff then review project proposals quarterly and determine which ones should move forward to the Inspector General for approval. Our analysis of DHS OIG data shows that a majority (about 59 percent) of the OIG’s oversight projects from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 resulted from this internal process.[33]

DHS OIG rates the risks associated with oversight projects already proposed rather than assessing risks across DHS first to identify potential oversight projects. As a result, DHS OIG’s internal process for proposing projects does not provide DHS OIG leadership and staff with a holistic view of the department’s programs, operations, management challenges, budget trends, and inherent risks (e.g., risk of fraud, waste, and abuse) to identify what types of projects to propose.[34] Thus, while DHS OIG may be selecting the highest risk projects from among available proposals, it does not have assurance that the proposals developed appropriately reflect DHS’s holistic risks. For example, DHS OIG has not assessed whether Coast Guard programs involve more or less risk relative to other programs at DHS. To follow standards for a risk-based work planning approach, as we recommended in June 2021, DHS OIG will need to assess risks across DHS programs and use that information to identify areas for audit, inspection, and evaluation. Conducting such risk assessments, as we recommended in June 2021, would better position DHS OIG to prioritize high-risk projects.

DHS OIG’s work planning approach determines its oversight work, including the extent of its Coast Guard oversight. During fiscal years 2019 through 2024, DHS OIG conducted fewer oversight projects on the Coast Guard compared to some other DHS components, as shown in table 2.[35] Table 2 shows the number of DHS OIG oversight projects per component and the size of each component in terms of full-time equivalent positions and budget, which are elements included in OIG’s dashboard for considering potential risks for project proposals.

Table 2: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Oversight Projects by Primary Component, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

|

DHS Primary Component |

Number of DHS OIG Projects |

Fiscal Year 2024 Number of Full-Time Equivalent Positions |

Fiscal Year 2024 Budget (in millions)a |

|

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

123 |

63,610 |

$24,603 |

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

110 |

14,702 |

$48,623b |

|

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

86 |

20,917 |

$10,293 |

|

Transportation Security Administration |

26 |

56,193 |

$11,073 |

|

U.S. Coast Guard |

22 |

51,622c |

$13,632 |

|

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

20 |

3,222 |

$2,895 |

|

U.S. Secret Service |

14 |

8,163 |

$3,413 |

|

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

13 |

22,100 |

$6,571 |

|

Analysis and Operationsd |

10 |

946 |

$369 |

|

Management Directoratee |

9 |

3,903 |

$4,202 |

|

Office of the Secretary and Executive Managementf |

5 |

948 |

$391 |

|

Science and Technology Directorate |

5 |

544 |

$826 |

|

Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers |

4 |

1,085 |

$548 |

|

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office |

2 |

252 |

$370 |

Source: GAO analysis of DHS OIG data and Office of Management and Budget information. | GAO‑26‑107341

Note: We analyzed DHS OIG’s data on completed and ongoing oversight projects. A project may be an audit, evaluation, or inspection, and may include more than one primary DHS component. An ongoing project is one that the DHS Inspector General approved to initiate but for which DHS OIG has not yet issued a final report. Investigations are not projects and therefore not reflected in the table above. DHS OIG also had 85 projects for which DHS was listed as the primary component, which included: (1) projects on programs and activities for which the department—and not an individual component—is responsible; (2) projects evaluating the extent to which at least one component adhered to department-wide policies; and (3) department-wide projects that include more than one component. For example, the Coast Guard was included in 27 DHS projects. According to DHS OIG officials, factors contributing to the scale of oversight of DHS components from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024 included the increase in the number of individuals entering the United States between ports of entry, the 2019 cyberattack against the federal government and private sector involving the SolarWinds network management software company, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s response during the COVID-19 pandemic.

aBudget data are rounded numbers as of fiscal year 2024. The budget information reflects the total budget authority as reported by the Office of Management and Budget in the 2026 President’s Budget Appendix. See Office of Management and Budget, Technical Supplement to the 2026 Budget, Appendix (Washington, D.C.). Total budget authority does not include all budgetary resources, such as carryover funds from a prior fiscal year. See Office of Management and Budget, Circular No. A-11: Preparation Submission, and Execution of the Budget (Washington, D.C.: July 25, 2024).

bThe Federal Emergency Management Agency’s budget includes about $36 billion from the Disaster Relief Fund—the primary source of federal disaster assistance for tribal, state, and territorial governments, as well individuals and households, when a major disaster is declared.

cCoast Guard full-time equivalent positions include military and civilian personnel.

dThese numbers include the Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness and the Office of Intelligence and Analysis.

eThese numbers include the Federal Protective Service, the Office of Biometric Identity Management, and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, among other offices.

fThese numbers include the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans and the Privacy Office.

DHS OIG Follows Some Standards for Managing Human Capital and Assessing Collective Competence

DHS OIG follows some selected elements of the federal quality standard for managing human capital. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that OIGs are to ensure that staff meet the requirements for continuing professional education included in the applicable professional standards. These quality standards also state that OIG management is responsible for deciding the methods by which identified needs can be met by using staff members who possess the requisite skills. Further, federal quality standards for OIGs state that each OIG is to assess staff members’ skills and determine the extent to which staff members collectively possess the professional competence (e.g., technical knowledge and experience) to perform assigned work.

Continuing Professional Education. DHS OIG program offices have processes in place to track the extent to which staff are meeting both internal and external requirements for training and continuing professional education, which are designed to ensure that OIG personnel collectively possess the skills and abilities to perform assigned tasks, including Coast Guard oversight. For example, the Office of Audits has a Quality Management and Training Division that is responsible for documenting completed training and conducting semiannual reviews to ensure staff are on target to meet requirements in compliance with government auditing standards.[36] The Office of Inspections and Evaluations has a training coordinator who is responsible for documenting completed training and tracks staff progress toward meeting requirements in compliance with applicable federal professional standards.[37] According to DHS OIG officials, the Office of Investigations has a training unit that is responsible for tracking investigators’ progress toward meeting requirements in compliance with applicable professional standards.[38]

Requisite Skills. DHS OIG officials document aspects of competence for each staff member before assigning them to oversight work, including Coast Guard projects. For example, the Office of Audits certifies whether staff have met continuing professional education requirements, and office management assesses staff members’ education and experience. The Office of Inspections and Evaluations also certifies whether staff have met continuing professional education requirements.

OIG program offices also identify whether internal staff may have specialized skills necessary for oversight work. For example, the Office of Audits may collaborate with the Office of Innovation’s Cybersecurity Risk Assessment Division to provide information technology security expertise and testing services to support DHS OIG audits.[39]

Collective Competence. In response to our June 2021 recommendation, DHS OIG has taken steps to implement a workforce plan that, consistent with federal quality standards for OIGs, ensures staff members collectively possess needed skills.[40] After issuing its strategic plan for fiscal years 2022 through 2026, DHS OIG contracted with an external organization that provided the OIG with support and guidance in the development of a workforce plan. As of January 2025, DHS OIG surveyed its Senior Executive Service personnel and identified two areas for additional development—communication and leadership. DHS OIG officials told us that they plan to identify relevant training to support that development.

However, DHS OIG does not have a workforce planning approach to systematically define current and future workforce needs. In August 2025, DHS OIG officials told us that they were in the process of developing a workforce planning process and associated workforce plan. To follow standards for assessing collective competence, as we recommended in June 2021, DHS OIG will need to (1) identify the skills needed to achieve its goals, (2) assess the extent to which DHS OIG staff possess those identified skills, and (3) identify strategies for meeting those workforce needs. A holistic assessment of the skills of its workforce could help DHS OIG understand any gaps between the skills its staff has and those the OIG requires to successfully complete its work, including Coast Guard oversight.

DHS OIG Follows Some Standards for Implementing a Quality Assurance Program

DHS OIG follows some selected elements of the federal quality standard for maintaining quality assurance. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that OIGs shall participate in external quality assurance review programs. According to these quality standards, external quality assurance reviews provide OIGs with added assurance regarding their adherence to prescribed standards, regulations, and legislation through an assessment of OIG operations, like Coast Guard oversight. These standards also state that OIGs shall establish and maintain a quality assurance program to ensure that work performed meets established standards of performance, including applicable professional standards.

External Quality Reviews. Independent organizations not affiliated with DHS OIG conducted four external quality assurance reviews—known as peer reviews—of DHS OIG activities from November 23, 2020, through March 14, 2024. DHS OIG received a pass rating for the two peer reviews of its audit activities.[41] According to the two peer reviews of DHS OIG’s inspection and evaluation activities, DHS OIG’s internal policies and procedures, as well as selected reports, generally met applicable federal professional standards.[42]

Quality Assurance. In response to our June 2021 recommendation, DHS OIG issued a directive in September 2023 establishing the OIG’s quality control and quality assurance program. This is an important step toward establishing and maintaining a quality assurance program that, consistent with federal quality standards for OIGs, ensures that work performed—like Coast Guard oversight—adheres to OIG policies and procedures and meets applicable professional standards.[43]

DHS OIG has taken some actions in line with the new quality assurance program directive. For example, in January 2025, the Office of Integrity issued a report for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 summarizing completed and ongoing quality control and quality assurance program activities. According to the report, the Office of Integrity reviewed the extent to which the Office of Audits and the Office of Inspections and Evaluations followed up on their recommendations to DHS and its components in a timely manner, among other quality-related activities.[44]

However, the Office of Integrity has not fully implemented its quality control and quality assurance program directive. For example, according to the directive, the Office of Integrity is to establish a Quality Control Review Division that, among other things, will conduct random quality control reviews of ongoing audit, inspection, and evaluation projects to ensure sufficiency of evidence and internal controls were followed.

According to its 2025 report summarizing completed and planned quality control and quality assurance program activities for fiscal years 2023 and 2024, the Office of Integrity is planning to complete standing up this Quality Control Review Division. In August 2025, DHS OIG officials told us that the time frame for completion is unknown and dependent on available resources. To follow standards for implementing a quality assurance program, as we recommended in June 2021, the Office of Integrity will need to fully implement its quality assurance and quality control directive. Fully standing up and maintaining its quality assurance program would help DHS OIG ensure its audit, inspection, evaluation, and investigation work on the Coast Guard is reliable.

DHS OIG Implemented Timeliness Benchmarks for Audits but Does Not Follow the Standard for Timely Reports

DHS OIG does not follow a selected element of the federal quality standard for communicating results of OIG activities. Federal quality standards for OIGs state that all OIG reports should be timely. Manuals for DHS OIG’s Office of Audits and Office of Inspections and Evaluations also state that reporting should be timely.

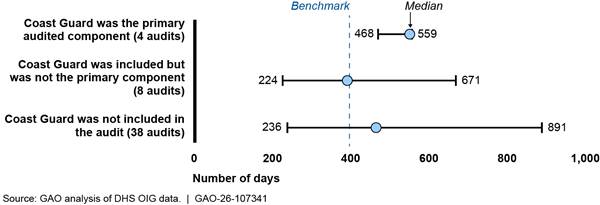

In August 2021, in response to one of our June 2021 recommendations, DHS OIG established new timeliness benchmarks for audits.[45] For example, DHS OIG established the benchmark to complete audits within 397 days (from initiation to product issuance). However, DHS OIG did not consistently meet its benchmark, based on our analysis of DHS OIG’s data on completed oversight projects from August 2021 through September 2024 (end of fiscal year 2024).[46]

Our analysis of DHS OIG data shows that the OIG did not meet its 397-day benchmark for any of the four audits for which the Coast Guard was the primary component under review from August 1, 2021, (when DHS OIG established the benchmark) through September 30, 2024, (end of fiscal year 2024), as shown in figure 6.[47] DHS OIG also did not meet its 397-day benchmark for half of the audits (four of eight audits) for which the Coast Guard was included but was not the primary DHS component under review. Further, DHS OIG did not meet this benchmark for about two-thirds of audits (26 out of 38 audits) that did not include the Coast Guard. Figure 6 also shows the range and median number of days in which DHS OIG completed these audits.

Figure 6: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Time Frames for Completing Audits by Level of Coast Guard Inclusion, August 2021 – September 2024

Note: We analyzed DHS OIG’s data on completed audits from August 2021 through September 2024 (end of fiscal year 2024). In August 2021, DHS OIG established a timeliness benchmark to complete audits within 397 days.

DHS OIG also established timeliness benchmarks for interim steps within the audit process, including for reviews of draft and final reports.

· Our analysis of DHS OIG data shows that the OIG did not consistently meet its benchmark to review draft reports within 23 days. Specifically, DHS OIG did not meet its draft report review benchmark for three out of four of its Coast Guard-focused audits and half of the audits (four of eight audits) that included the Coast Guard. DHS OIG also did not meet its draft review benchmark for a majority (20 of 33 audits) of the audits that did not include the Coast Guard.

· Our analysis of the DHS OIG data shows that the OIG generally met its timeliness benchmark to review final reports within 19 days. Specifically, DHS OIG met its final report review benchmark for all four Coast Guard-focused audits and for six of eight other audits that included the Coast Guard. DHS OIG also met its final review benchmark for most of the audits (25 of 30 audits) that did not include the Coast Guard.

In its own reported January 2024 assessment of timeliness benchmarks, DHS OIG found that, on average, it did not meet its benchmarks for planning and fieldwork for all audits that initiated on or after October 1, 2021, (i.e., those audits that initiated in fiscal years 2022 through 2023, the first two full fiscal years since DHS OIG had implemented the benchmarks). In this assessment, DHS OIG attributed not meeting its timeliness benchmarks to two external factors, specifically (1) delays in receiving components’ comments and (2) delays in obtaining DHS components’ data. In June 2025, DHS OIG officials cited these same factors as the reasons for not meeting timeliness benchmarks.

DHS Components’ Comments. Although DHS generally missed the deadline for providing agency comments to DHS OIG within 30 days, our analysis of DHS OIG data found that the delays were minimal in relation to overall audit time frames.[48] Of the 34 audits for which DHS OIG did not meet its overall timeliness benchmark, the median number of days by which the OIG missed the benchmark was 139 days. DHS OIG’s data also show that if DHS components had met the deadline to provide comments for these 34 audits, DHS OIG would have met the overall timeliness benchmark for two of those audits. It would not have met the overall benchmark for the remaining 32 audits.

· DHS and the Coast Guard did not meet the deadline to provide comments for all four audits for which it was the primary component under review, missing the deadline by a range of two to six days. However, DHS OIG did not meet its overall timeliness benchmark for completing these Coast Guard audits by a range of 71 days to 162 days.

· DHS and its components did not meet the deadline to provide comments for five of eight audits that included the Coast Guard. Of these five audits, DHS and its components missed the deadline by a range of three to 25 days. DHS OIG met its overall timeliness benchmark for two of these five audits but did not meet its overall benchmark for completing the other three audits by a range of 43 to 274 days.

· DHS and its components did not meet the deadline to provide comments for most audits (30 of 38 audits) that did not include the Coast Guard. Of these 30 audits, DHS and its components missed the deadline by a range of one to 39 days. DHS OIG met its overall timeliness benchmark for eight of these 30 audits but did not meet its overall benchmark for completing the other 22 audits by a range of three to 494 days.

DHS Components’ Data. According to DHS OIG officials, the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, authorizes DHS OIG to have direct access to DHS data systems. However, they have faced challenges in obtaining direct access to components’ data systems. Specifically, DHS OIG officials told us that some DHS components will immediately deny their request for direct access, while other components may take 90 days or longer to deny their request. The officials said that if a DHS component denies the OIG’s request for direct access, then DHS OIG will request data extracts so that its audit, inspection, or evaluation team may continue their oversight work. OIG officials also told us that when they previously made concurrent requests for direct access to a system and for data extracts from that system, DHS provided the data extracts but denied the requests for direct access.

In its semiannual report to Congress covering April 2024 through September 2024, DHS OIG reported that its requests for direct, “read-only” access to databases and data extracts were both denied and delayed.[49] For example, according to this report, the Coast Guard denied DHS OIG direct access to two data systems due to sensitivity concerns and then subsequently provided the OIG with data extracts.[50] DHS OIG reported that it received the data extracts 88 calendar days after it first requested direct access to the Coast Guard’s systems.

DHS OIG officials told us that they address DHS data access challenges by (1) meeting regularly with department and component data personnel to discuss access challenges and try to negotiate access to data systems, (2) notifying the Secretary of Homeland Security, and (3) reporting on the challenges in the OIG’s semiannual reports to Congress. As part of the Secretary of Homeland Security’s transmittal of the semiannual report covering April 2024 through September 2024, the Secretary stated that in response to the OIG’s requests for direct access to data systems, the department and its components may seek information on the relevance of the data to the scope and objectives of the OIG’s oversight work. The Secretary also noted the department’s responsibility for safeguarding sensitive information and preventing improper disclosure. DHS OIG officials similarly told us two reasons the department and its components provide for denying the OIG’s request for direct access are that the data systems may include (1) data that are not relevant to the scope of the OIG’s oversight project and (2) sensitive data—raising concerns about privacy and security. DHS OIG officials told us that they routinely explain to DHS officials how the OIG protects sensitive information.

DHS OIG officials told us that although they track requests for direct access to data systems and requests for data extracts—including any denials and delays to such requests—they have not assessed the extent to which these data access challenges have affected meeting the OIG’s timeliness benchmarks. By assessing the extent to which data access challenges affect oversight project time frames, DHS OIG could use the results of that assessment to identify an approach to address those challenges.

In its annual performance report for fiscal year 2024, DHS OIG reported that it met its performance target to issue 50 percent of all audits, inspections, and evaluations within established time frames. According to its strategic implementation plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2026, DHS OIG has a performance target to increase this target over time. Its strategic implementation plan sets a goal of issuing 57 percent of all audits, inspections, and evaluations within established time frames by fiscal year 2026. Identifying an approach for addressing denials and delays to requests for direct access to data systems and requests for data extracts could better position the OIG to complete oversight projects in a timely manner.

CGIS and DHS OIG Investigate Coast Guard Complaints but Do Not Collaborate Effectively

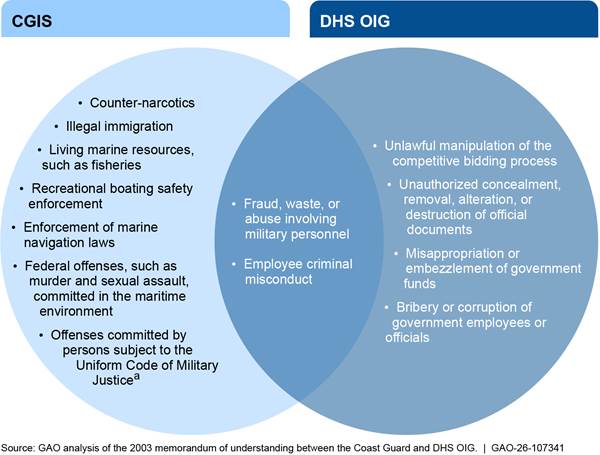

CGIS and DHS OIG have overlapping authorities to investigate certain Coast Guard complaints, such as those involving criminal conduct within the Coast Guard. CGIS primarily conducts criminal investigations of the Coast Guard, including alleged violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[51] DHS OIG investigates misconduct involving the Coast Guard, including criminal allegations of fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement.[52] From October 2018 through May 2024, CGIS received and investigated more Coast Guard complaints than DHS OIG. CGIS and DHS OIG identified the need to prevent duplicative investigations, but the two agencies have not fully followed five out of six selected leading practices for collaboration.[53] For example, the agencies have not established clear roles and responsibilities for CGIS to refer Coast Guard complaints to DHS OIG, and they have not updated their written agreement for complaint referrals in over 20 years.

CGIS and DHS OIG Received and Investigated Coast Guard Complaints

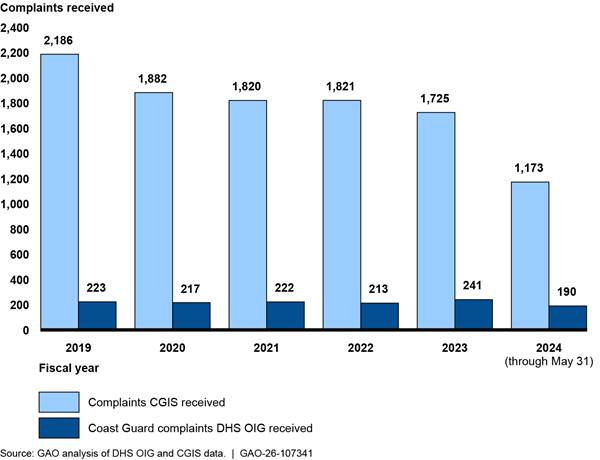

CGIS and DHS OIG Received Coast Guard Complaints

CGIS received more Coast Guard complaints than DHS OIG from October 2018 through May 2024, as shown in figure 7.[54] Specifically, based on its data, CGIS received 10,607 complaints. In contrast, DHS OIG received 1,306 Coast Guard complaints, which was less than 1 percent of the total number of complaints (163,265 complaints) it received across all DHS components during that time.

Figure 7: Coast Guard Complaints Received by the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG), October 2018 – May 2024

Note: The Coast Guard is one of 14 DHS components for which DHS OIG receives complaints. A complaint includes at least one allegation of criminal, civil, or administrative misconduct involving Coast Guard employees, contractors, grantees, or programs.

CGIS and DHS OIG process complaints differently in their case management systems. In CGIS’s case management system, complaints remain open while CGIS is either reviewing or investigating the complaint, according to CGIS officials. Therefore, an open complaint could indicate an ongoing investigation. In contrast, DHS OIG closes a complaint in its case management system when administratively closing the complaint, referring it to another investigative entity, or opening an investigation on that complaint.

CGIS and DHS OIG have closed most of the complaints they received from October 2018 through May 2024.

· According to its data, CGIS closed about 93 percent (9,854 complaints) of the 10,607 complaints it received from October 2018 through May 2024. Of the 753 complaints that remained open, CGIS received a majority of them (404 complaints) more recently (since October 1, 2023).[55] Because of the way CGIS tracks complaints in its case management system, a closed complaint indicates all work to address the complaint has been completed but does not indicate whether an investigation occurred.

· According to its data, DHS OIG closed almost all (1,302 of 1,306) of the Coast Guard complaints it received from October 2018 through May 2024.[56] DHS OIG officials told us because of the way DHS OIG tracks complaints and investigations in its case management system, some of these closed complaints have been opened for investigation. Therefore, a closed complaint does not indicate that the complaint has been fully addressed.

CGIS and DHS OIG Investigated Coast Guard Complaints

Based on its data, CGIS investigated at least 4,951 Coast Guard complaints from October 2018 through May 2024. After CGIS completes an investigation, if it substantiated the alleged criminal offense, CGIS can refer such complaints for additional action, such as discipline (e.g., written or verbal reprimand, suspension, or discharge) or legal adjudication. Therefore, referring a complaint for additional action indicates that CGIS investigated that complaint.[57] Of the 9,854 complaints that CGIS received and closed, CGIS referred about half (4,951 complaints) for additional action to responsible entities. Specifically, CGIS referred 1,545 complaints of alleged crimes under the Uniform Code of Military Justice to the appropriate convening authority.[58] CGIS also referred 3,406 complaints to the relevant U.S. Attorney’s Office.[59]

Comparatively, DHS OIG data show that it opened investigations for 70 Coast Guard complaints from October 2018 through May 2024, about half of which (32 investigations) remained open as of May 31, 2024.[60] Of the 32 investigations that remained open, almost half (14 investigations) were opened more recently (since October 1, 2023).

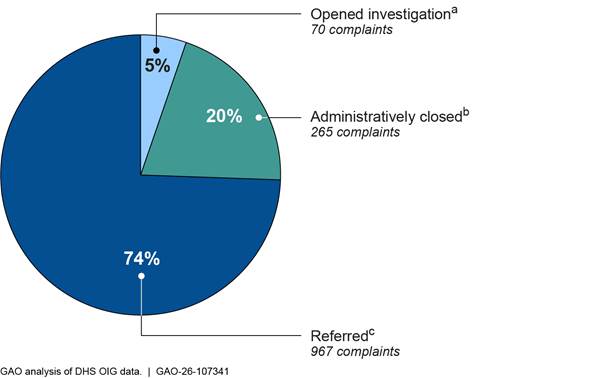

Unlike CGIS, DHS OIG’s case management system tracks the disposition decisions for each complaint (i.e., referred to other investigative entities, administratively closed, or opened for investigation). Based on its data, DHS OIG referred about 74 percent (967 out of 1,302) of the closed Coast Guard complaints to other investigative entities, as shown in figure 8. Of the 967 Coast Guard complaints that DHS OIG referred to other investigative entities, the OIG referred at least 97 percent (940 complaints) to the Coast Guard, including to CGIS.[61] DHS OIG officials told us that the data do not distinguish between referring complaints to Coast Guard leadership and referring complaints to CGIS. As a result, we could not analyze the number of Coast Guard complaints that DHS OIG referred only to CGIS.

Figure 8: Closed Coast Guard Complaints by Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Disposition Decision, October 2018 – May 2024

aDHS OIG implemented case opening guidelines in May 2023 to review complaints, identify complaints that align with the OIG’s investigative priorities, and decide whether to open an investigation.

bDHS OIG officials told us that the OIG can administratively close complaints under limited circumstances, including duplicate complaints, when the complaint will be assumed under an existing investigation, when the information provided is nonsensical, or when the Office of Investigations refers a complaint to another program office within DHS OIG (e.g., Office of Audits) for a different type of oversight (e.g., audit rather than investigation).

cDHS OIG may refer some complaints to DHS components’ internal investigative offices, including the Coast Guard Investigative Service.

CGIS and DHS OIG Investigated Coast Guard Complaints Related to Alleged Criminal Offenses

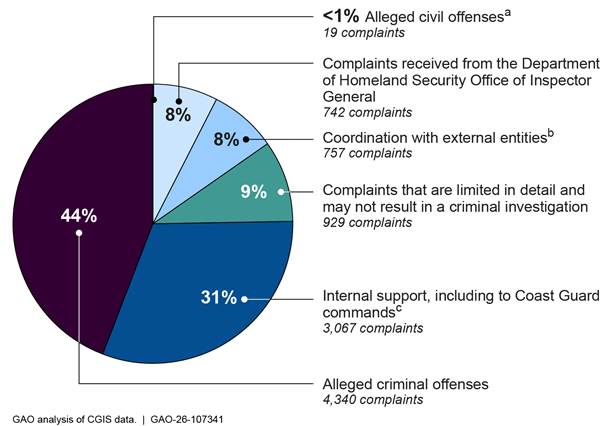

Our analysis of CGIS data shows that of the complaints that CGIS received from October 2018 through May 2024 and subsequently closed (as of July 1, 2024), at least 44 percent (4,340 of 9,854 complaints) involved alleged criminal offenses. Examples of criminal offenses CGIS investigated included offenses related to controlled substances, assault, and special victims (e.g., children and victims of human trafficking). Other types of complaints include CGIS’s support to Coast Guard’s Counterintelligence Service (e.g., identifying and addressing the operations of foreign intelligence entities and of non-state actors attempting to attain information about Coast Guard operations) or alleged cybersecurity incidents. These other types of complaints could also involve alleged criminal offenses because the relevant CGIS data field that indicates complaint type, including whether the complaint involved an alleged criminal offense, has other options that could also involve alleged criminal offenses. For example, the data field records whether a complaint was received from DHS OIG, and such complaints may involve an alleged criminal or civil offense. Figure 9 shows the distribution of complaint types as reflected in this data field, including CGIS support to Coast Guard commands and alleged suspicious activity.

Figure 9: Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) Closed Complaints by Type, Received October 2018 – May 2024

Note: Of the 10,607 complaints that CGIS received from October 1, 2018, through May 1, 2024, CGIS closed 9,854 of them by July 1, 2024—the status at the time of our request. Closed complaints include those that CGIS received and closed without an investigation, as well as those closed after an investigation.

aThis complaint type includes investigative activities related to the enforcement of regulatory compliance and to the gathering of evidence in support of a lawsuit.

bThis complaint type includes CGIS coordination (e.g., sharing law enforcement information) with external entities, including other federal, state, local, tribal, military, and foreign law enforcement and criminal investigative agencies.

cThis complaint type includes (1) CGIS support to Coast Guard commands (e.g., conducting interviews in support of administrative investigations); (2) CGIS support to Coast Guard’s Counterintelligence Service (e.g., identifying and addressing the operations of foreign intelligence entities and of non-state actors attempting to attain information about Coast Guard operations); and (3) alleged cybersecurity incidents.

Fiscal year 2021 is the first full fiscal year in which DHS OIG began consistently tracking the nature of the offense in its investigative data. Our analysis of DHS OIG data shows that DHS OIG investigated 45 Coast Guard complaints (containing 65 alleged offenses) from October 1, 2020 (beginning of fiscal year 2021) through May 31, 2024. Of these 45 Coast Guard complaints, 24 complaints were related to alleged whistleblower retaliation. In addition, about half of offenses associated with the 45 Coast Guard complaints that DHS OIG investigated were related to alleged criminal offenses.[62]

· Of the 65 offenses under investigation for the 45 Coast Guard complaints, 36 offenses (about 55 percent) were alleged criminal offenses.

· About half of those 36 criminal offenses were related to fraud (17 offenses), and the other half were related to criminal offenses that DHS OIG officials told us are less common, such as aiding and abetting or conspiracy to commit an offense. The remaining 29 non-criminal offenses included non-criminal sexual harassment, obstruction of process, and personnel actions.[63]

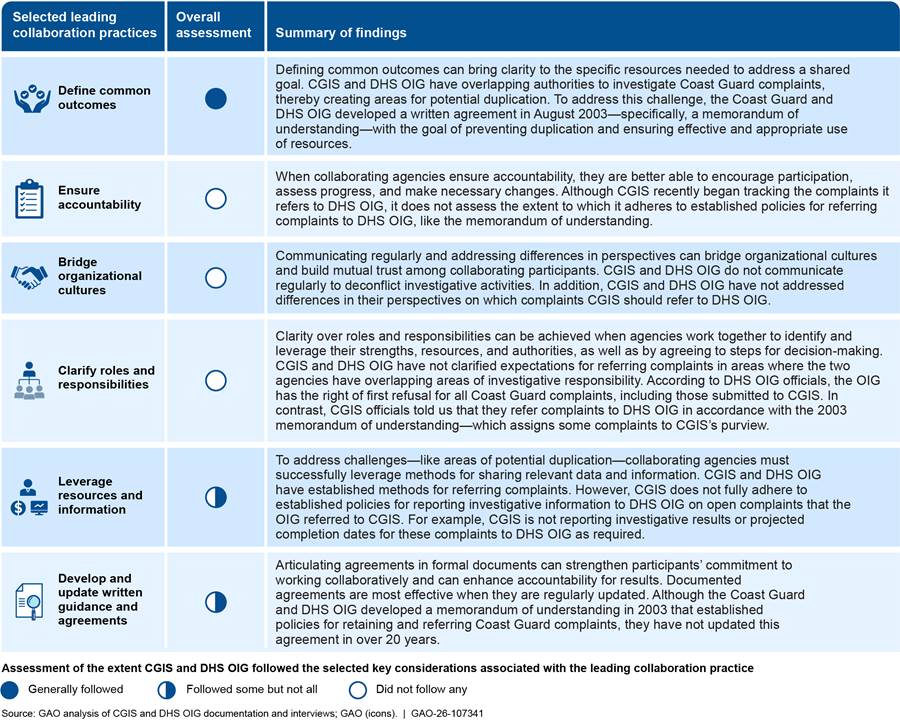

CGIS and DHS OIG Have Not Fully Followed Five of Six Selected Leading Practices for Collaboration

Our leading practices for interagency collaboration and key considerations for implementing the practices can provide valuable insight and guidance to improve collaboration between agencies.[64] CGIS and DHS OIG generally followed the leading practice for defining common outcomes, but they partially followed or did not follow the other five selected leading practices, as shown in figure 10.[65] CGIS and DHS OIG both have authority to investigate alleged criminal misconduct within the Coast Guard. Our prior work has emphasized the importance of following leading practices for collaboration to address areas of potential fragmentation, overlap, and duplication.[66]

Figure 10: Extent to Which the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) Have Followed Selected Leading Practices for Collaboration

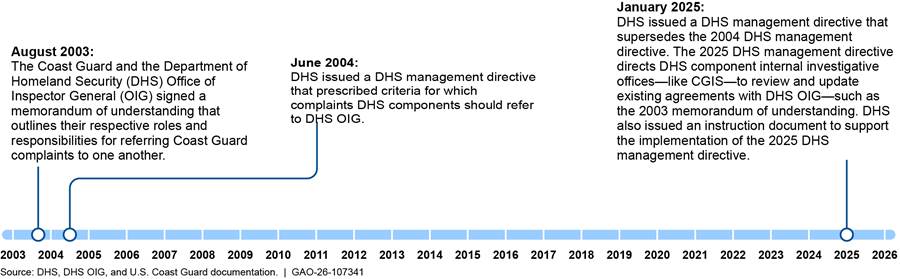

Define Common Outcomes. CGIS and DHS OIG generally followed this leading practice by identifying common outcomes for receiving, retaining, and referring Coast Guard complaints. According to our leading practices for collaboration, defining common outcomes can bring clarity to the specific resources needed to address a shared goal. In August 2003, the Coast Guard and DHS OIG signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that outlines their respective roles and responsibilities for referring Coast Guard complaints to one another. CGIS implements the 2003 MOU for the Coast Guard. According to the 2003 MOU, the purpose of the agreement is to help the Coast Guard and DHS OIG achieve common outcomes for preventing duplicative Coast Guard investigations and ensuring the most effective and appropriate use of Coast Guard and DHS OIG resources when addressing Coast Guard complaints. As discussed later, however, the 2003 MOU has not been updated.

Ensure Accountability. CGIS did not follow the leading practice for ensuring accountability and assessing progress toward common outcomes. According to our leading practices for collaboration, when collaborating entities ensure accountability, they are better able to encourage participation, assess progress, and make necessary changes. We have reported that having a way to track and monitor progress towards outcomes, like preventing duplicative investigations, is a key consideration in assessing a collaborative mechanism.[67] We have also reported that, if agencies do not use performance information and other types of evidence to assess progress toward outcomes, they may be at risk of failing to achieve their outcomes.[68]

Prior to July 2025, CGIS had not implemented policies and procedures for tracking the complaints it refers to DHS OIG and thus was not doing so consistently. In October 2024, CGIS notified its staff that they were required to begin tracking all complaints referred to DHS OIG in CGIS’s case management system, among other requirements. In July 2025, CGIS implemented standard operating procedures that institutionalized, in policy, a requirement to track referrals to DHS OIG.[69]

Although CGIS recently began tracking referrals to DHS OIG, CGIS does not assess the extent to which it adheres to the 2003 MOU for referring complaints to DHS OIG. According to the July 2025 standard operating procedures, CGIS supervisors (e.g., Assistant Directors and Special Agents in Charge) are to ensure that CGIS staff are aware of the 2003 MOU’s requirements for referring complaints to DHS OIG and ensure compliance with those requirements. However, the standard operating procedures do not include requirements for CGIS to assess whether its staff are consistently, appropriately, and completely doing so. In addition, CGIS officials told us that they do not regularly conduct such an assessment.

DHS OIG officials expressed concern that, based on the number of complaints they receive from CGIS, they believe CGIS is not referring all the complaints that DHS OIG would expect to receive from CGIS. These officials noted that not receiving complaints limits their visibility into serious allegations, which—according to DHS OIG officials—is central to the OIG’s independence as an oversight body.

By developing and implementing a process to regularly assess the extent to which CGIS is adhering to established policies for referring complaints to DHS OIG—like the 2003 MOU—CGIS and DHS OIG would be better positioned to achieve their common outcomes for preventing duplicative investigations and using resources effectively and appropriately. By identifying corrective action, as needed, based on the results of such assessments, CGIS would be better positioned to ensure compliance with referral requirements.

Bridge Organizational Cultures. CGIS and DHS OIG did not follow the leading practice for bridging organizational cultures. According to our leading practices for collaboration, building trust among collaborating agencies that are not co-located—like CGIS and DHS OIG—requires more frequent communication. We have also reported that addressing differences in perspectives can create the mutual trust among collaborating participants that is critical to enhance and sustain the collaborative effort.[70] As participants engage in trust-building activities—like communicating regularly and addressing differences in perspective—they often become better equipped to effectively work together, identify new opportunities, and find innovative solutions to shared problems. Further, according to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should communicate with, and obtain relevant and quality information from, appropriate external parties to achieve objectives.[71]

In addition, DHS issued a management directive in January 2025 that established requirements for DHS components to collaborate with DHS OIG on complaint referrals. DHS also issued an instruction that corresponds with the 2025 management directive. This instruction directs DHS OIG and DHS components’ internal investigative offices, like CGIS, to hold quarterly meetings to ensure continued collaboration on complaint referrals and operational deconfliction.[72] Such regular meetings would support the leading practice to bridge organizational cultures and align with internal control standards for communication.

In April 2025, CGIS and DHS OIG officials told us they do not have regularly scheduled meetings to collaborate on complaint referrals or deconflict investigative activities. CGIS officials told us that their communication with DHS OIG is limited to the OIG’s decisions on whether to open investigations on complaints that CGIS has referred to it. As a result, the two agencies do not communicate about Coast Guard investigative activities until CGIS refers a complaint to DHS OIG. DHS OIG officials told us that they prefer to deconflict investigative activities by reviewing all the complaints that CGIS receives and deciding whether to open investigations or refer them back to CGIS.

However, CGIS and DHS OIG do not agree on which complaints CGIS should refer to DHS OIG. In June 2025, DHS OIG officials told us that they interpret the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, as giving DHS OIG the right of first refusal on all DHS complaints—that is, the right to initially review all complaints, including those submitted to CGIS.[73] DHS OIG officials also told us that they currently do not follow the 2003 MOU because it does not give them the right of first refusal. In contrast, CGIS officials told us that they follow the 2003 MOU and thus do not refer all complaints to DHS OIG. CGIS and DHS OIG have not addressed these differences in their perspectives on which complaints CGIS should refer to DHS OIG.

Given these differences in perspectives, establishing regular communication, in accordance with leading practices, could provide an opportunity for deconfliction and coordination on complaint referrals. Regular communication could also better position CGIS and DHS OIG to understand and resolve differences in perspective, prevent duplicative investigations in areas where their responsibilities overlap, and collaborate effectively. By establishing regular communication for deconflicting investigative activities, CGIS and DHS OIG would be able to stay informed of one another’s efforts to investigate the Coast Guard, allocate resources appropriately, and build mutual trust.

Clarify Roles and Responsibilities. CGIS and DHS OIG did not follow the leading practice for having clear roles and responsibilities for referring Coast Guard complaints. According to our leading practices for collaboration, clarifying roles and responsibilities between agencies can be achieved when agencies work together to identify and leverage their strengths, resources, and authorities, as well as agreeing to steps for decision-making.

As we previously mentioned, CGIS and DHS OIG do not agree on which Coast Guard complaints, if any, CGIS may retain without first referring the complaint to DHS OIG. DHS OIG’s position is that CGIS should refer every complaint it receives to the OIG, but CGIS officials told us that they refer complaints to DHS OIG in accordance with the 2003 MOU.[74]

However, we identified sections of the 2003 MOU about referring complaints that were unclear, and CGIS officials also told us they believe these sections are unclear:

· One section of the 2003 MOU specifies that CGIS should refer (1) complaints of wrongful conduct in areas of OIG investigative responsibilities and (2) all complaints of fraud, waste, mismanagement, or abuse. DHS OIG officials also told us that the 2003 MOU does not clearly describe the OIG’s investigative authority. It states that DHS OIG is responsible for criminal, civil, and administrative investigations relating to DHS programs and operations as specified in the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended.[75] This section of the 2003 MOU also lists examples—such as bribery or corruption of government employees or officials—that would generally fall within the type of activity that CGIS should refer to DHS OIG, but it states that this list is not intended to be exhaustive. Therefore, while the examples provide guidance on some types of complaints CGIS should refer, it does not provide a comprehensive list.

· Another section of the 2003 MOU says that DHS OIG shall lead investigations involving allegations of (1) fraud, waste, or abuse committed by Coast Guard civilian employees, members of the Coast Guard Auxiliary, or non-affiliated civilians and (2) alleged criminal misconduct of senior civilian employees (General Schedule grade 15 or comparable), members of the Senior Executive Service, political appointees, and military personnel above the rank of Captain.[76] That same section notes that CGIS may investigate any suspected incident of fraud, waste, or abuse involving military personnel, provided that only military personnel are involved in such crimes and any victims are subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Therefore, it is not always clear when CGIS should refer complaints involving senior military personnel to DHS OIG.

CGIS officials explained that the 2003 MOU’s provisions regarding alleged criminal misconduct by Coast Guard senior officials could be interpreted in different ways. For example:

· According to CGIS officials, any violation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice could be considered criminal misconduct. Thus, one possible interpretation of the 2003 MOU is that CGIS is to refer any alleged violation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice by a senior official to DHS OIG.

· However, the 2003 MOU also places complaints related to the Uniform Code of Military Justice under CGIS’s purview. Another possible interpretation, then, is that CGIS may retain complaints alleging violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice by a senior official.