HIGH RISK RESEARCH

HHS Should Publicly Share More Information on How Risk Is Assessed and Mitigated

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-26-107348

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Mary Denigan-Macauley at DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Research that involves modifying pathogens that have the potential to cause a pandemic—sometimes referred to as “gain-of-function research of concern”—has been a topic of debate. Based on GAO’s review of literature and other sources, this research has advanced scientific knowledge of how pathogens infect humans and transmit and cause disease. However, there is no broad agreement on the extent to which this research has directly led to the development of vaccines and therapeutics, such as for COVID-19. There was broad consensus that gain-of-function research of concern can pose biosafety and biosecurity risks. This is because this research can involve enhancing the transmissibility or virulence of pathogens that have the potential to cause widespread and uncontrollable disease, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality if they were to be accidentally or deliberately released from a lab.

As part of its effort to lead the federal public health and medical response to potential biological threats and emerging infectious diseases, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides funding for, and conducts research on, pathogens of varying risk level. GAO found that HHS procedures for reviewing research—including research that can be considered gain-of-function research of concern—generally include identifying and assessing the risks of the pathogen and the proposed experiment and assessing the adequacy and appropriateness of proposed risk mitigation strategies. If risks cannot be mitigated, HHS agencies can decide not to fund or conduct the research. However, GAO also found that HHS does not always share key information on these risk reviews with the public. For example, HHS reports to federal stakeholders about the number of research projects involving certain higher risk pathogens and the related risks and associated mitigation measures but does not report more widely. Some HHS officials told GAO they supported sharing general information about their risk reviews with the public. HHS has also reported that transparency helps to ensure public trust in federally funded scientific research. Sharing such information would help provide greater assurance to the public, science community, and Congress that HHS has procedures to manage risks.

Why GAO Did This Study

Recently introduced legislation and executive actions have aimed to restrict or ban federal departments and agencies, like HHS, from conducting or funding gain-of-function research of concern.

GAO was asked to review the outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern and related risk mitigation strategies. This report (1) describes findings from literature and reports that discuss outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern and (2) examines HHS’s procedures for reviewing risk and risk mitigation strategies for research involving pathogens.

GAO identified outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern by reviewing literature and other sources published from 2019 to 2024. GAO reviewed HHS procedures for reviewing risks and risk mitigation strategies and federal policies and guidance for the oversight of higher-risk pathogen research and interviewed HHS officials. GAO also interviewed eight biosafety and biosecurity experts selected because they authored relevant articles and had experience with gain-of-function research of concern.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that HHS ensure that key information on its risk reviews of research involving pathogens are publicly shared, as appropriate, with researchers, Congress, and the public, including steps taken to mitigate risk. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendation, but noted it will work in the future to ensure public transparency about the scope of research involving higher-risk pathogens and actions taken to mitigate risks.

Abbreviations

ASPR Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

FDA Food and Drug Administration

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NIH National Institutes of Health

NSABB National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity

OSTP Office of Science and Technology Policy

SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 20, 2026

Congressional Requesters

Over the years, questions have been raised about the risks and benefits of life science research on pathogens that have the potential to cause a pandemic, as well as federal efforts to oversee this research.[1] The terms used to describe this research—sometimes referred to as “gain-of-function research of concern”—have varied over the years and debate remains over these terms and definitions.[2] For the purposes of our review, we consider gain-of-function research of concern to be any research that imparts new traits, removes existing traits, or enhances existing traits in a microorganism that could increase the risk of morbidity or mortality in humans.[3]

Congress has considered legislation that would restrict or ban federal agencies from conducting or funding gain-of-function research of concern. For example, in February 2025, a bill was introduced in the Senate that would ban federal research grants to academic and research institutions that conduct gain-of-function research that increases the ability of certain pathogens, such as an influenza virus and coronavirus, to infect, transmit, and cause disease.[4] In March 2025, two other bills were introduced in the Senate and the House that would create an independent oversight board to review and approve federal funding for proposed high-risk life sciences research.[5]

Additionally, in May 2025, the White House issued an Executive Order directing the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to strengthen oversight, accountability, and enforcement mechanisms for federal funding of dangerous gain-of-function research, such as research that enhances the ability of an infectious agent to transmit and cause disease.[6] The Executive Order also directs OSTP to establish guidance on suspending federal funding for this research until at least the new OSTP policy is completed. In accordance with the Executive Order, in June 2025 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suspended funding for projects involving this research until the new OSTP policy is implemented.[7]

As part of its efforts to lead the federal public health and medical response to potential biological threats and emerging infectious diseases, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its component agencies fund and conduct research on pathogens of varying risk level, which may include research that could be considered gain-of-function research of concern. These component agencies include NIH, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

HHS and its component agencies are responsible for reviewing proposals, including assessing the risks associated with the research described in these proposals and assessing the proposed strategies to mitigate those risks. For example, HHS has a department-level review process for assessing the risks, benefits, and the researchers’ capacity to ensure biosafety for funding proposals that involve enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.[8] This includes research proposals to enhance the transmissibility or virulence of pathogens that already have the likely potential to cause wide and uncontrollable disease, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality in human populations.

In 2023, we made several recommendations to HHS to improve the oversight of research involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.[9] Specifically, we recommended that HHS develop standard terms to help ensure consistency in its departmental review process for identifying research proposals that may create, transfer, or use enhanced potential pandemic pathogens. Further, we recommended that HHS share more information about its review process with the public, including information on the composition and expertise of those involved in the review process and how the evaluation criteria are applied. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with these recommendations. We also reiterated a prior recommendation about the need for a single federal entity charged with conducting government-wide evaluations of high-containment laboratories to determine the aggregate risks associated with research involving dangerous pathogens, including privately funded research involving pathogens with pandemic potential. As of December 2025, these recommendations had not been implemented.

Over the past decade, we have made 58 recommendations to HHS and other federal departments to strengthen biosafety and biosecurity of pathogen research.[10] As of December 2025, all but nine had been implemented.[11]

You asked us to review the outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern and related risk mitigation strategies. This report:

1) describes findings from literature and reports that discuss the reported outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern; and

2) examines HHS’s procedures for reviewing risk and risk mitigation strategies for research involving pathogens.

In the first objective, we focused on research that imparts new traits, removes existing traits, or enhances existing traits in a microorganism that could increase the risk of morbidity or mortality in humans. We use the term gain-of-function research of concern to refer to this research because Congress, the media, and others frequently use this phrase in reference to this research. We developed our definition based on a review of research and policy articles as well as federal reports and policies on the oversight of higher-risk pathogen research.[12] We refer to research, experiments, and studies as gain-of-function research of concern in instances where the literature and reports did not explicitly use this term. To identify gain-of-function research of concern from these sources, we reviewed the descriptions or context of the research, experiments, and studies referenced and determined that they met our definition of gain-of-function research of concern.

To describe the reported outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern, we conducted a search in several bibliographic databases of peer-reviewed scientific journals for literature that discussed the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. Of the sources we identified as part of our literature search, we determined that 11 contained information pertinent to our review: seven commentaries, two research articles, one e-book, and one news update. We also reviewed seven federal, international, and policy-related reports and policies, hereinafter referred to as biosecurity reports. We included in our scope literature and biosecurity reports published from 2019 to 2024. We chose this period to include sources published 1 year prior to and 1 year after the COVID-19 pandemic. We reviewed one federal biosecurity report published outside this period (in 2016) because the report summarized the results of an independent study on the risks and benefits associated with gain-of-function studies commissioned by NIH. We also reviewed an Executive Order published in 2025 because the order provided a framework for overseeing gain-of-function research of concern.

To supplement information from our literature review, we spoke with a nongeneralizable selection of eight biosafety, biosecurity, and biomedical experts who collectively provided a range of perspectives on the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. Four of these experts were selected because they authored articles we identified through our literature search. We selected the other four experts because they (1) had experience identifying and examining the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern, and (2) provided a range of perspectives on the risks and benefits of this research.

For the second objective, we focused our review on agencies’ procedures for all pathogen research. We used terms specified in federal policies and guidance in referring to higher risk research on pathogens. We did this to ensure our review included HHS’s procedures for all research on pathogens that could be considered gain-of-function research of concern.

To examine HHS’s procedures for reviewing risk and risk mitigation strategies for research involving pathogens, we reviewed HHS and agency-specific policies, guidance, and other documents related to the review of research that agencies fund (extramural) and conduct (intramural). This included guidance and forms for assessing risk and risk mitigation strategies for higher risk research on pathogens. We focused our review on the four agencies within HHS that fund or conduct pathogen research: ASPR, CDC, FDA, and NIH. In addition, we focused on agencies’ procedures for all pathogen research because gain-of-function research of concern can involve pathogens and experiments that are overseen by multiple federal policies and guidance. We also focused on agencies’ procedures before an extramural grant or contract is awarded and before an intramural project is approved and the research begins.

We reviewed federal policies and guidance on the oversight of higher-risk pathogen research, such as the 2017 Recommended Policy Guidance for Departmental Development of Review Mechanisms for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight, and the 2017 HHS Framework for Guiding Funding Decisions about Proposed Research Involving Enhanced Potential Pandemic Pathogens. Additionally, we interviewed officials from ASPR, CDC, FDA, and NIH about how they assess risk for extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens.

We assessed HHS agencies’ procedures against guidance on conducting risk assessments in U.S. biosafety guidance Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories as well as Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[13]

In addition, we reviewed publicly available information on how HHS and agencies review risk for research involving pathogens, including the outcomes of these reviews and steps taken to mitigate risks. We also reviewed agency data on the number of projects involving higher risk research on pathogens that agencies supported from 2017 (when HHS established its policy for the oversight of research involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens) through 2024 (most recently available data). We compared this information to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and a relevant element of GAO’s key elements of effective oversight—transparency.[14] According to this element, the organization conducting oversight should provide access to key information, as applicable, to those most affected by operations. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Gain-of-Function Research on Pathogens

Gain-of-function research is a broad area of scientific research in which researchers introduce genetic alterations in an organism to create a new or enhanced trait in the organism. Conversely, in loss-of-function research, genetic alterations result in a loss or diminished trait in an organism. Both types of genetic changes often occur naturally. (see text box)

|

Risks Posed by Pathogen Changes in Nature Pathogens undergo natural alterations in the wild outside any human manipulation. For example, influenza (flu) viruses are continually changing over time as they replicate—infect people and make copies of themselves. These changes are an important reason why people can get the flu multiple times over the course of their lives. Such naturally occurring changes can confer advantages to pathogens that may increase their virulence and ability to cause disease. Some changes that allow pathogens to infect a new host can increase the risk of a pandemic. For example, the avian influenza virus (bird flu) is a virus that occurs naturally among wild aquatic birds and can spread to other birds and animals, including farmed poultry. Prior to 1997, known human infections with the bird flu were linked to an intermediate host animal, such as a pig. However, in 1997, a natural genetic mutation in a strain of the bird flu, H5N1, led to a deadly outbreak in Hong Kong. H5N1 was confirmed to have passed directly to humans from exposure to birds at live poultry markets without an intermediate host and with no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Diseases in animals that can transmit to humans but have little or no known ability to spread between humans are easier to control or eradicate through measures such as livestock culls. A total depopulation of all poultry markets and chicken farms during the 1997 Hong Kong outbreak prevented further spread of the virus between birds and to humans. This outbreak incident demonstrated how naturally occurring virus strains can become more transmissible to humans and cause more severe disease. Source: GAO presentation of information from research articles and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. | GAO 26 107348 |

Scientists can introduce genetic changes to pathogens via gain-of-function approaches to better understand how pathogens transmit, infect, and cause disease. The idea is that by improving the understanding of human-pathogen interactions, this research can predict pathogen changes that may occur naturally and further public health preparedness.

A subset of gain-of-function research is gain-of-function research of concern. In 2016, the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB)—a federal advisory committee that advises on issues related to biosafety and biosecurity oversight of biomedical research—proposed using the term gain-of-function research of concern to describe a small subset of gain-of-function research on pathogens that posed risks potentially significant enough to warrant additional federal oversight.[15] Specifically, the term was used to describe gain-of-function research that had the potential to generate pathogens with pandemic potential in humans by exhibiting high rates of transmissibility and virulence. NSABB developed this term as part of the U.S. government’s process to evaluate the risks and benefits of this research and to develop policies to govern its funding and oversight. This process began in the fall of 2014 when the U.S. government paused funding for a specific type of gain-of-function research that was anticipated to enhance the transmissibility or pathogenicity of influenza viruses, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses.[16]

Federal Laws, Regulations, Policies, and Guidance for Pathogen Research

The United States has biosafety, biocontainment, and biosecurity laws, regulations, policies, and guidance in place to identify and mitigate risks associated with pathogen research and to protect laboratory workers, public health, agriculture, the environment, and national security. These mechanisms include federal laws, regulations, policies, and guidance that may apply to higher risk research involving pathogens, specifically research on certain pathogens that pose higher risk to human, animal, or plant health. They include:

· Federal laws and regulations governing the possession, use, and transfer of select agents and toxins.

o Certain biological agents and toxins are designated as “select agents and toxins” because they have the potential to pose a severe threat to public, animal, or plant health and safety. For example, some potential pandemic pathogens, such as SARS-associated coronavirus, are select agents.

o The Federal Select Agent Program—jointly managed by HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture—oversees laboratories’ handling of these select agents and toxins.[17]

· Federal policies and guidance for agencies conducting and managing federally funded life science research, including biosafety and biosecurity practices involving pathogen research. That guidance includes:

o United States Government Policies for the Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern. These policies establish procedures for federal and institutional review and oversight of a subset of life science research—involving certain experiments with specified agents and toxins—to identify dual use research of concern and mitigate risks where appropriate.[18] Dual use research of concern can be generally described as life science research that is reasonably anticipated to generate information, products, or technologies that could be misapplied, posing a significant threat to public health and safety or national security.[19] For example, these policies provide guidance for the review of research that enhances the harmful consequences of certain pathogens, like the Ebola virus, for the potential of being dual use research of concern.

o Recommended Policy Guidance for Departmental Development of Review Mechanisms for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight. In 2017, OSTP published recommended guidance for federal departments and agencies in establishing a department-level pre-funding review mechanism for federally funded research that is anticipated to create, transfer, or use enhanced pathogens with pandemic potential.[20]

o Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. NIH, in conjunction with CDC, publishes Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, an advisory document recommending best practices for the safe conduct of work in biomedical and clinical laboratories from a biosafety perspective.[21] This document has become the overarching guidance for the practice of biosafety in the United States—the mechanism for addressing the safe handling and containment of infectious pathogens and hazardous biological materials.

o NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines). These guidelines detail safety practices and containment procedures for basic and clinical research involving manipulated or laboratory-created nucleic acid molecules (i.e., genetic building blocks), and cells, organisms, and viruses containing such molecules.[22] They also provide guidance for researchers and institutions for assessing the level of risk of research involving biological agents known to infect humans and the appropriate containment conditions for the experiment.

Pathogen Research at HHS

HHS is the federal department most directly involved in leading public health preparedness and response research. This includes research on known and emerging pathogens that could pose a public health threat as well as research that supports the development of medical countermeasures to help mitigate these threats. See figure 1.

Within HHS, component agencies such as CDC, FDA, and NIH conduct their own research—known as intramural research—to identify and prepare for public health threats. These agencies, along with ASPR, also review, provide guidance, and fund research conducted by others—known as extramural research—that may involve topics related to public health risks and support the development of medical countermeasures. See figure 2. Extramural research is typically conducted at universities, medical schools, private biotechnology companies, and other research institutions.

Figure 2: Areas of Pathogen Research at Select Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Agencies

The HHS Grants Policy Statement outlines general processes for awarding discretionary grants, including grants for extramural research.[23] Funding agencies, including CDC, FDA, and NIH, must notify the public of the availability of funding and solicit applications for financial awards. Applications undergo a merit and pre-award risk review by agencies prior to approval for funding.[24] In general, grant applications are first reviewed for scientific and technical merit by merit or peer reviewers (i.e., subject matter experts who are to provide an objective and unbiased evaluation of proposals). These reviewers can be non-federal or HHS personnel. Merit or peer reviewers evaluate grant applications based on criteria provided by funding agencies. Based on these reviews and other considerations, agency officials determine whether to approve funding. Agencies issue notices of award to approved applicants that specify the award amounts, performance periods, and any terms and conditions of the awards.

Other HHS agencies, such as ASPR, award contracts or use other transaction agreements to support extramural research. Similar to HHS’s grant award processes, ASPR publicly solicits research proposals that support the development of medical countermeasures. A technical evaluation panel, which can include non-federal or HHS subject matter experts, evaluates the proposal based on the criteria provided in the solicitation. ASPR then determines whether to award the contract.

Gain-of-Function Research of Concern Has Advanced Our Understanding of Pathogens, but Can Pose Biosafety and Biosecurity Risks

Literature Discussed How Research Has Advanced Scientific Knowledge, but Disagreed Over Its Effect on Developing Pandemic Prevention Measures

Understanding of Pathogens

Our review of literature published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and biosecurity reports found that one outcome of gain-of-function research of concern has been the advancement of scientific knowledge of pathogens.[25] Six sources we reviewed cited examples of how gain-of-function research of concern has yielded important information about how pathogens infect humans and other mammals, as well as transmit and cause disease. Specifically:

· Five of these sources discussed how two studies published in 2012 showed that the H5N1 avian influenza virus, also known as bird flu, could transmit between mammals via respiratory droplets using ferrets as a model.[26] In these studies, researchers genetically modified the H5N1 virus so that it became capable of airborne transmission in ferrets.[27] Ferrets are a common model for human respiratory diseases because of similarities between human and ferret respiratory systems. We considered the two studies referenced by these sources to be gain-of-function research of concern because they involved research that imparted new traits to the H5N1 virus that could increase the virus’s risk of causing morbidity or mortality in humans.[28]

Two sources suggested that this discovery was significant for understanding how the pathogen transmits and causes disease because it identified the types of mutations that could allow H5N1—which occasionally infects people but does not transmit efficiently from person-to-person—to naturally evolve into an airborne virus capable of spreading more easily among people. Airborne viruses have greater potential to cause a pandemic because they are more easily spread, potentially affecting numerous people across multiple countries.

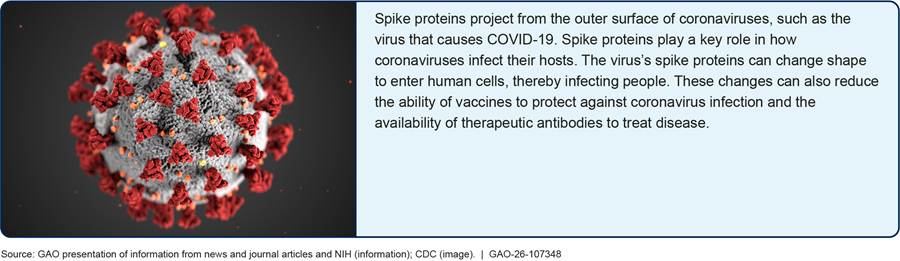

· Two sources discussed how a study published in 2013 and a study published in 2015 contributed to the discovery that certain coronaviruses from horseshoe bats can infect human cells.[29] Specifically, in the 2013 study, researchers isolated a coronavirus from a horseshoe bat that showed the capability to infect human cells through viral features called spike proteins (see figure 3).[30] In the 2015 study, researchers used reverse genetics to create a chimeric (see textbox below) mouse-adapted SARS virus that was able to infect and replicate in human airway cells using these spike proteins to enter these cells.[31] We considered the 2015 study to be gain-of-function research of concern because it involved research that imparted new traits to a coronavirus that could increase the virus’s risk of causing morbidity or mortality in humans.[32]

One source suggested that this discovery was significant at the time because it raised the possibility that coronaviruses circulating in bats had the potential to cross species and infect humans. Moreover, the studies showed these coronaviruses were similar to SARS in that they had the capability to cause severe disease and thus had the potential to pose a global threat to public health.[33]

|

Virus Chimeras A chimera is an organism or tissue that contains DNA from at least two different types of organisms. A chimeric virus combines genetic material or other structural components from different viruses. Chimeric viruses that contain the backbone and replication machinery of a select agent virus, or contain genes from different select agent viruses, may be regulated by the Federal Select Agent Program. The Federal Select Agent Program oversees the possession, use, and transfer of select agents and toxins, which have the potential to pose a severe threat to public, animal, or plant health and safety. In November 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services added specific Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses—SARS-CoV/SARS-CoV-2 chimeras resulting from any deliberate manipulation of SARS-CoV-2 to incorporate nucleic acids coding for SARS-CoV virulence factors—to the select agent list. Additionally, research on chimeric viruses must comply with the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines). These guidelines detail safety practices and containment procedures for basic and clinical research involving manipulated or laboratory-created nucleic acid molecules (i.e., genetic building blocks), and cells, organisms, and viruses containing such molecules. The guidelines require institutions receiving NIH funding to review and approve containment procedures and safety practices before such research is initiated. Source: GAO presentation of information from the Federal Select Agent Program, NIH, and other sources. | GAO 26 107348 |

One biosecurity report we reviewed stated that some of the knowledge gained from gain-of-function research of concern is unique to that method; in other words, it cannot be achieved by alternative, non-gain-of-function approaches.[34] Another report noted that it may take time to realize the benefits or usefulness of the knowledge obtained from this research.[35]

Seven of the eight experts we spoke with said that gain-of-function research of concern has advanced scientific knowledge of pathogens. However, one of these experts said that this research has led to only incremental advances in scientific knowledge.

Development of Pandemic Prevention Measures

While the advancement of scientific knowledge of pathogens was generally identified as an outcome of gain-of-function research of concern by the sources we reviewed, we found that the literature we reviewed disagreed about the extent to which the development of pandemic prevention measures has been an outcome of this research.

According to some sources we reviewed, gain-of-function research of concern can be viewed as broadly contributing to a body of research on a pathogen and how it causes disease. Findings from these studies are used at a later date to inform the development of a vaccine or therapeutic.

For example, one source published in mBio in 2021 discussed how pathogen research published since 2015—which we considered to be gain-of-function research of concern—led to the development of self-disseminating vaccines aimed at protecting against emerging strains of animal viruses before they could infect humans.[36] Self-disseminating vaccines are designed to spread through animal host populations without the need for direct inoculation of every animal. To illustrate, a study published in 2016 discussed experiments that created self-disseminating vaccines for eradicating Ebola virus infections in African wildlife.[37] These wildlife infections have the potential to spread to humans. The referenced experiments did not increase the likelihood that the Ebola virus would spread from animals to humans; however, we considered them to be gain-of-function research of concern because they involved research that imparted new traits—increased infectivity—to zoonotic pathogens that have been known to cause infections in humans, thereby increasing the risk of these pathogens causing morbidity or mortality in humans. The source published in mBio identified this research as an example of pandemic research that posed dual-use risk.[38]

|

Pandemic Preparedness for Avian Influenza According to the World Health Organization, avian influenza subtype A (bird flu) normally spreads in birds, but can also infect humans. Human infections are primarily acquired through direct contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments. While avian influenza viruses do not currently transmit easily from person to person, the ongoing circulation of these viruses in poultry is concerning, as these viruses can cause mild to severe illness and death. These viruses also have the potential to mutate to become more contagious. In the United States, efforts are ongoing to control the spread of the H5N1 strain of the bird flu, including its spread to dairy cattle. The strain shows adaptations for mammal-to-mammal spread, and researchers are analyzing the virus to identify genetic changes that might allow it to spread more easily to and between people. Since 2024, there have been 41 confirmed human cases of the bird flu linked to exposure to commercial dairy herds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as of December 2025. Pandemic preparedness involves close surveillance of this situation to monitor isolated outbreaks for new mutations, particularly for mutations that may increase the virus’s ability for respiratory transmission. Identification of these traits may allow for quick action to contain an outbreak before it becomes a pandemic.

Source: GAO analysis of the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites and research articles. (data); Erik_AJV/stock.adobe.com (image). | GAO‑26‑107348 |

More generally, a different source stated that gain-of-function research of concern can advance pandemic preparedness and the development of vaccines and antivirals.[39] Two other sources discussed perspectives on how gain-of-function research on viruses and other microbes can help determine which aspects of these viruses and microbes might be a suitable target for medical countermeasures and how they could become resistant to these countermeasures.[40] One source suggested that this research could help with pandemic forecasting by predicting the mutations that could plausibly arise within a virus and how these mutations could lead to changes in the virus’s ability to infect and transmit between humans.

In contrast, some sources argued that gain-of-function research of concern can only lead to the development of medical countermeasures and pandemic prevention measures if the original research was directly used to develop them. For example, two sources stated that previous gain-of-function studies on coronaviruses and the bird flu have not immediately or directly led to the development of medical countermeasures or pandemic prevention measures for specific viruses. These sources suggested that this research has limited, or no ability, to inform vaccine development for specific viruses, detect virus transmission, or predict outbreaks of disease. Specifically:

· One source published in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology in 2022 stated that gain-of-function experiments on coronaviruses have limited practical value because they do not immediately or directly contribute to clinical research that would ensure a vaccine or therapeutic is safe and effective, particularly against a specific virus strain.[41] The source also suggested that there was no evidence that these studies helped predict specific epidemic strains of the virus or helped with the selection of vaccine strains to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

· Another source published in mBio in 2023 argued that, more broadly, gain-of-function research of concern does not yield any immediately applicable benefits, and previous gain-of-function studies on the bird flu and coronaviruses in horseshoe bats did not directly lead to the development of an FDA-approved medical countermeasure.[42]

The experts we interviewed also had differing views about the outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern. Four of eight experts we spoke with said gain-of-function research of concern helped lead to the development of vaccines and therapeutics for specific viruses, such as COVID-19. For example, one of these experts told us that this research was used to quickly generate SARS-CoV-2 in a cell culture to test whether a COVID-19 vaccine was effective. In contrast, four experts disagreed. One of these experts told us that the information obtained from gain-of-function research of concern experiments has no practical benefit and is not used to develop medical countermeasures. The expert stated that medical countermeasures are developed in response to disease threats detected in nature, rather than those created in a laboratory. The expert noted that, even if a gain-of-function study identifies a dangerous pathogen mutation, it is unknown whether that strain will occur in nature and whether medical countermeasures will be needed to combat it.

Research Can Pose Biosafety and Biosecurity Risks

Despite different perspectives on the outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern, we found that there was broad consensus among the sources we reviewed that this research can pose biosafety and biosecurity risks.[43] Moreover, these risks are exacerbated by pathogens that have been altered to transmit more easily or to increase disease severity, potentially causing widespread and uncontrollable disease and posing significant consequences for the public and global health if released accidently or deliberately. One biosecurity report specifically noted the potential for a loss of public trust if a laboratory accident involving a modified pathogen were to occur or if this research were intentionally misused to cause harm.[44] We have previously reported on the inherent risks across all types of research involving dangerous pathogens and the need for strengthened oversight of such research.[45]

The sources we reviewed cited a variety of hypothetical biosafety and biosecurity risks that gain-of-function research of concern can pose. For example, biosafety risks could include laboratory-acquired infections or the accidental release or personal exposure of a modified pathogen outside of laboratory containment. Biosecurity risks could include the theft or release of a modified pathogen by a malevolent actor; or the theft or misuse of information obtained from gain-of-function research of concern experiments to create a biological weapon.

Additionally, two sources highlighted the risks posed by publishing information from gain-of-function research on pathogens. For example, the source published in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology in 2022 suggested that gain-of-function techniques used in experiments in 2001 to create a mousepox strain capable of defeating vaccines and pre-existing immunity raised concerns that similar modifications could be made to the human smallpox virus.[46] Of particular concern was the possibility that terrorists could apply these techniques to create more virulent forms of smallpox, including vaccine-resistant strains.[47] The source published in mBio in 2021 suggested that malicious actors could replicate the gain-of-function techniques used to alter strains of SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 pandemic to create a biological weapon.[48]

Similarly, seven of the eight experts we interviewed told us that gain-of-function research of concern can pose biosafety and biosecurity risks. In contrast, one expert said that scientists cannot predict the risks of gain-of-function research of concern, and the risks of this research are overstated because of a lack of trust in scientists and public health officials.

None of the sources we reviewed identified any incidents, illnesses, outbreaks, or pandemics that had definitively resulted from gain-of-function research of concern. For example, one biosecurity report from the American Society for Microbiology stated that there have been no known instances of laboratory-acquired infections from this research.[49] One source raised questions, however. Specifically, a source published in mBio in 2023 raised the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic could have resulted from a laboratory accident involving this research.[50] The source also noted that other explanations for the origins of the pandemic were also plausible, such as a natural spillover from wild animals to humans. A 2024 report published by the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic raised the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted from a laboratory or research-related accident involving gain-of-function research of concern.[51]

Likewise, seven of the eight experts did not identify any incidents, illnesses, outbreaks, or pandemics that had definitively resulted from gain-of-function research of concern. However, one expert said that, based on the available evidence, the COVID-19 pandemic was caused by gain-of-function research of concern “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Another of the experts raised the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic could have resulted from a laboratory accident but noted that other explanations for the origins of the pandemic were also plausible.

We have previously reported that determining the likely origin of pandemics is challenging.[52]

HHS Procedures Include Assessing Pathogen and Experiment Risks; Key Information on Risk Reviews Is Not Always Shared Publicly

HHS Procedures Include Assessing Pathogen and Experiment Risks as Well as the Adequacy of Risk Mitigation Strategies

In general, HHS agencies have procedures for reviewing risk and risk mitigation strategies for extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens, including research that can be considered gain-of-function research of concern. These procedures include (1) identifying and reviewing risk; (2) assessing proposed risk mitigation strategies; and (3) addressing concerns related to risk and risk mitigation strategies. Who reviews for risk and related processes can vary depending on the type of pathogen research, including whether it involves extramural research or intramural projects. Overall, agencies’ procedures are consistent with risk assessment principles described in U.S. biosafety guidance, Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (6th edition).[53] According to this guidance, the risk assessment process should include identifying and assessing the risks of work involving hazardous biological agents, such as infectious pathogens, and determining the appropriate risk mitigation measures.

Identifying and Reviewing Risks

Agencies’ procedures for identifying and reviewing pathogen and experiment risks can include determining the characteristics of a pathogen and whether the proposed extramural research or intramural project involves biohazards and higher risk pathogens, such as select agents or toxins. It also can include evaluating the potential effects of the experiment on the pathogen, such as experiments that have the potential to increase a pathogen’s transmissibility or virulence. In some instances, agencies’ procedures include weighing the risks of the proposed research or project against its benefits. For example,

· For proposed extramural research, NIH guidance instructs peer reviewers to identify potential biohazards—biological organisms or their products, such as toxins, that pose a threat to human health—and other hazards, such as recombinant DNA that are known to pose a particularly significant risk to research personnel or the environment. According to NIH guidance, following peer review, if a proposal is recommended for funding, NIH program staff use a checklist to identify any risk or safety issues, such as whether the proposal involves select agents.

· At ASPR, based on our review of agency guidance and information from ASPR officials, a technical evaluation panel, comprised of subject matter experts, considers several factors in assessing risk for extramural research involving pathogens. Specifically, ASPR officials told us the panel determines whether proposed research involves wild-type pathogens (i.e., naturally occurring variants that have not been genetically modified). These officials added that the panel assesses whether proposed experiments have the potential to increase the transmissibility or virulence of a pathogen. In addition to risk, the panel assesses the potential benefits of the proposed research, namely whether the experiments are likely to advance a candidate vaccine or therapeutic toward FDA approval.

· According to agency documents and interviews with agency officials, FDA center and office managers review and approve intramural research projects involving pathogen research. FDA officials told us that as part of this process, the agency’s managers assess risk and risk mitigation strategies for proposed intramural projects, and, if approved, assess this information periodically, including annual reports. These officials added that, in weighing the risks of proposed research, FDA managers consider the potential positive effect the research can have toward the agency’s mission.

Agency risk assessments are, in part, guided by federal regulations, policies, and guidance for the oversight of higher-risk pathogen research. These include the NIH Guidelines, regulations, policies, and guidance on select agents and toxins, dual use research of concern, and research on enhanced potential pandemic pathogens. These federal regulations, policies, and guidance specify criteria and actions that agencies must apply and undertake for the review of this research, both as federal agencies awarding funds for extramural research and as institutions conducting intramural research. In general, agency institutional biosafety committees and institutional review entities are responsible for determining whether an intramural project involves higher-risk pathogen research (see textbox). These committees and entities, as well as researchers, are also responsible for conducting risk assessments for these projects.

|

Institutional Biosafety Committees and Institutional Review Entities Institutional biosafety committees are established under the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines) to provide local review and oversight of nearly all forms of research using manipulated or laboratory-created nucleic acid molecules (i.e., genetic building blocks), and cells, organisms, and viruses containing such molecules. Institutions that receive funding from NIH for research involving recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules must establish an institutional biosafety committee. These institutions can include federal agencies, including NIH. Some institutions have chosen to assign their institutional biosafety committees the responsibility of reviewing a variety of other research involving biological materials (e.g., infectious agents) and other potentially hazardous agents. Institutional review entities are established under the 2014 United States Government Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern to provide review and oversight of dual use research of concern—generally described as life science research that is reasonably anticipated to generate information, products, or technologies that could be misapplied, posing a significant threat to public health and safety or national security. Institutions that receive federal funding to conduct or sponsor life sciences research and research involving the 15 agents and toxins specified by the 2014 policy must establish an institutional review entity. Institutions have the option of using all or a subset of their institutional biosafety committees to fulfill the role and requirements of these entities. Source: GAO analysis of NIH information and U.S. Government, United States Government Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (Washington, D.C.: September 24, 2014). | GAO‑26‑107348 |

For example,

· We found, through our review of agency documents and interviews with agency officials, that CDC, FDA, and NIH institutional biosafety committees and institutional review entities use checklists and forms to evaluate select aspects of intramural research projects. Specifically, committees and entities evaluate whether the project includes the pathogens and experimental effects described in the NIH Guidelines and federal policies for dual use research of concern and enhanced potential pandemic pathogens. In the case of CDC and NIH, these evaluations also include a discussion with researchers about their research. The entities also determine whether intramural research potentially involves enhanced potential pandemic pathogens, and, if so, refer these projects for department-level review.[54]

· According to NIH standard operating procedures, a review committee at NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—a component of NIH—assesses risk for extramural research proposals involving potential pandemic pathogens that the institute considers funding. As part of this assessment, the committee determines whether these proposals require department-level review and identifies options that researchers and institutions may pursue moving forward. These options include pursuing department-level review; modifying or removing the work subject to department-level review; and submitting a new proposal.[55]

· If proposed research or a project involves the possession, use, or transfer of a select agent or toxin, agencies’ procedures specify that researchers must register information about their work in accordance with Federal Select Agent Program regulations.[56] CDC, FDA, and NIH officials told us that they coordinate with the Federal Select Agent Program for research involving select agents. NIH officials also told us that such coordination ensures that a researcher’s registration is complete.[57]

Assessing Risk Mitigation Strategies

Agencies’ procedures also include assessing the adequacy and appropriateness of an extramural research proposal’s or intramural project’s risk mitigation strategies. For example,

· For extramural research proposals, NIH guidance instructs peer reviewers to consider several factors in assessing whether the risk mitigation strategies are appropriate and adequate for any identified biohazards and select agents in the proposed research. These factors include whether personnel handling hazardous materials are properly trained, proposed protocols address safety concerns, and proposed containment facilities and procedures are adequate. According to NIH guidance, program staff communicate any biohazard or biosafety concerns identified during review to management, and work with management to resolve any concerns.

· CDC, FDA, and NIH institutional biosafety committees use criteria described in NIH Guidelines and other agency guidance to assess risk mitigation strategies for intramural research involving pathogens, based on our review of agency guidance and information from agency officials. For example, these committees review whether the researcher has identified the required containment level for the pathogen and whether their facilities, laboratory practices, and personnel training align with the NIH Guidelines and Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories.

· If the CDC, FDA, and NIH institutional review entity determines that an intramural project meets the criteria for dual use research of concern or research potentially involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens, the institutional review entity requires the researcher to develop a risk mitigation plan, as outlined in federal policy, based on our review of agency guidance and interviews with agency officials.[58] For example, FDA officials told us that the agency’s institutional review entity works with the researcher to develop a risk mitigation plan. Such a plan can include modifying the design or conduct of the research, applying specific or enhanced biosecurity or biosafety measures, and conducting experiments to determine the efficacy of medical countermeasures. Risk mitigation plans for projects potentially involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens are reviewed at the department-level.[59]

Addressing Concerns Related to Risk or Risk Mitigation Strategies

Additionally, agencies’ procedures include actions that reviewers and agency officials must take and options they can consider to address risk or safety concerns, or if they determine that the risk mitigation strategies for the proposed research or project are inadequate. These steps can include modifying the proposed research or project, enhancing risk mitigation strategies, and not recommending the research for funding or not approving the project. For example,

· If ASPR’s technical evaluation panel determines that an extramural research proposal involves gain-of-function research or research that involves the manipulation of pathogens resulting in potential gain-of-function research, the agency will not fund the proposal, according to ASPR guidance. ASPR officials told us the agency does not fund this type of research.

· For extramural research proposals, NIH guidance states that issues with risk mitigation strategies identified by peer reviewers, such as inappropriate or inadequate plans for the safe handling of biohazards, can have an adverse effect on how the proposed research is considered for funding. Additionally, if there are concerns that the proposed research could endanger the public, peer reviewers can consider recommending that NIH deny funding for the proposed research.

· CDC, FDA, and NIH institutional biosafety committees and institutional review entities can take several steps if they identify a risk-related concern, to include modifying the proposal, based on our review of agency documentation and interviews with agency officials. For example, FDA’s committee can recommend the researcher address the concern and resubmit their application for secondary review. Agency officials told us that the committees and entities will not approve a proposal until all concerns are addressed.

· For extramural research proposals, a research institution’s institutional biosafety committee or institutional review entity must review and approve the proposed research prior to agency review, according to federal policies and guidance. NIH officials told us the agency would not fund the proposal if the committee or entity did not approve the proposal.

HHS Agencies Share Some Information About Risk Reviews on Pathogen Research but Other Key Details Are Not Made Public

HHS agencies publicly share some information about their procedures for reviewing risks and risk mitigation strategies for pathogen research. Specifically, HHS provides some information publicly on the outcomes of risk reviews and the number of experiments and research projects agencies approved and funded for certain research involving select agents and toxins and enhanced potential pandemic pathogens. HHS also provides some information publicly on steps taken to mitigate risks for research involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.

|

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Transparency Requirements for Institutions’ Institutional Biosafety Committees In June 2025, NIH outlined expectations that institutions that receive agency funding for research involving recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules (i.e., genetic building blocks) must post meeting minutes from their institutional biosafety committee meetings taking place on, or after, June 1, 2025. These meeting minutes must be posted on an institution’s publicly accessible website immediately after approval. According to NIH, this effort is aimed at enhancing transparency in biosafety oversight, as these meeting minutes serve as a record of the committee’s decision-making rationale, including risk assessments. Additionally, NIH began publicly posting the rosters of all active institutional biosafety committees registered with the agency. Source: GAO analysis of NIH information. | GAO‑26‑107348 |

For example,

· the Federal Select Agent Program’s annual report—published by CDC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture—includes the total number of restricted experiments involving select agents and toxins reviewed by the program and how many were approved or denied.[60] The report is available as part of the program’s commitment to transparency, according to the program’s website.

· ASPR—which coordinates department-level review of research projects involving enhanced potential pandemic pathogens—provides similar information on its website about the projects that have undergone department-level review since 2018. For example, as of July 2025, ASPR’s site states that NIH referred four projects for department-level review, three of which were modified or had elements removed to make them acceptable for HHS funding. The fourth project was not funded. The site generally describes how risk and risk mitigation plans were considered for these projects. For example, the site states that the department-level review group evaluated risk-benefit analyses and risk mitigation plans for these projects. For two of the four projects, the group recommended changes to increase the potential benefits of the research while decreasing risks; however, it determined that that there were no feasible, less risky alternative methods to address the same research question than those proposed by the researchers.

HHS’s sharing of partial information is positive and helps the public understand how risks are reviewed and mitigated; however, these efforts do not fully align with a key element of effective oversight—transparency. This is because HHS agencies have not publicly shared and regularly updated additional key information they have on the outcomes of risk reviews, risk mitigation steps, and the number of proposals and projects HHS agencies supported.

Documents we reviewed and agency officials we interviewed indicated that the agencies already share this key information they collect with other federal stakeholders, but not with the public. For example, as required, in a December 2024 report to the to the Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism, HHS agencies reported on outcomes of reviews that identified risks associated with extramural and intramural projects involving dual use research of concern that the agencies supported.[61] The December 2024 report also identified risk mitigation measures already in place or proposed for these projects.

Separately, NIH officials told us that, on a yearly basis, the agency supported approximately 200 to 300 proposals and projects involving the specified select agents and toxins subject to dual use research of concern policies from December 2017 to June 2024.[62] FDA officials told us that the agency did not deny funding or approval for any extramural research or intramural projects involving pathogens due to research risks. In addition, ASPR and FDA officials said that, as of December 2024, these agencies have not funded any research involving dual use research of concern or enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.

FDA officials told us that they do not publicly share this information because the agency is not required to do so. In addition, ASPR and NIH officials noted that agencies’ websites had some information about their risk review procedures, such as review criteria and considerations for peer review of extramural research at NIH. However, ASPR and CDC officials told us that they supported publicly sharing general information about their risk reviews and identified additional information agencies could share with the public. This information included aggregate data on the number of extramural proposals and intramural projects involving pathogens that agencies reviewed and the number of proposals and projects not funded or not approved due to risk considerations. CDC officials suggested that the complexity and potential security risks associated with the research, such as proprietary or private information, should be considered in deciding what information is shared publicly on risk reviews.

In our past work, we have identified key elements of effective oversight in areas where low-probability adverse events can have significant and far-reaching effects, including work in life science research.[63] One such key element—transparency—states that organizations conducting oversight, such as HHS, should provide key information to those most affected by operations, in this case those seeking to conduct research and the public.[64] Providing information on the outcomes of risk reviews, steps taken to mitigate risk, and the total number of research projects involving higher-risk pathogen research that HHS agencies supported, while taking into consideration security risks associated with the research, would be consistent with this key element. Additionally, federal internal control standards state that management should provide quality information to external parties so that they can help the organization achieve its objectives and address related risks.[65] In August 2025, HHS issued a report to OSTP, titled Implementing Gold Standard Science, that stated that transparency is an important tenet of science that is trustworthy and accountable to the scientific community and the public, and helps to ensure public trust in federally funded scientific research. NIH and FDA also issued program directives on the agencies’ implementation of this tenet, including steps to ensure transparency in agency funded research.[66] Further, an HHS official emphasized the importance of transparency on HHS-funded research. In March 2025, NIH Director Dr. Jayanta Bhattacharya testified to Congress during his confirmation hearing that NIH’s operations should be transparent.[67]

Publicly sharing and regularly updating key information about HHS agencies’ risk reviews for extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens, including the outcomes of these reviews, would enhance public trust by providing greater assurance to the public, Congress, and the scientific community that HHS has procedures to manage risks. We acknowledge the sensitivity and complexity of these risk reviews. Those most involved in the review process—HHS and component agencies—are best positioned to identify key information, as appropriate, that could be shared with the public. Improving transparency while balancing risk also would help provide greater assurance that HHS funding agencies adequately review risk and take steps to mitigate risk for extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens. Further, increasing transparency on risk reviews will better align with the May 2025 Executive Order that directs OSTP to strengthen oversight; increase accountability through enforcement, audits, and improved public transparency; and clearly define the scope of covered research while ensuring the United States remains the global leader in biotechnology, biological countermeasures, and health research.[68]

Conclusions

HHS is the leading federal department responsible for research on pathogens that could pose a public health threat. This includes research that modifies pathogens that have the potential to cause a pandemic—sometimes referred to as gain-of-function research of concern. Pathogen research can play a key role in improving the understanding of pathogen changes that may occur naturally and further public health preparedness. However, this research is not without risks, including the possibility of laboratory accidents and the deliberate misuse of dangerous pathogens or related research information.

Thus, it is crucial that HHS and its funding agencies thoroughly consider issues of risk during their review of research proposals involving pathogens. Our review shows that HHS agencies have procedures for assessing risk and risk mitigation strategies for proposed extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens. However, HHS could help provide greater assurance of the quality of its oversight by publicly sharing, as appropriate, and regularly updating, key information with researchers, Congress, and the public on its risk reviews for this research. This includes the outcomes of risk reviews, steps HHS funding agencies and researchers took to mitigate risk, and the total number of proposals and projects involving higher-risk pathogen research that agencies support.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should work with HHS funding agencies to ensure that key information on the agencies’ risk reviews of extramural research and intramural projects involving pathogens are publicly shared with researchers, Congress, and the public, as appropriate. Such information should be regularly updated and include the outcomes of risk reviews, steps HHS funding agencies and researchers took to mitigate risk, and the total number of research projects involving higher-risk pathogen research that agencies support. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate. HHS also provided general comments reprinted in appendix II.

HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendation, but noted the department is committed to reviewing projects involving higher-risk pathogens to understand and mitigate any risks posed by such research. HHS further noted that as of the date of its response, all “dangerous gain-of-function research” was suspended, per the May 2025 Executive Order, until the United States Government Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential, which was issued by OSTP in May 2024, is revised or replaced. Upon establishment of the requisite policy, HHS stated that it will apply the proper reviews and ensure public transparency about the scope of the research and actions taken to mitigate such risks.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary for Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact me at DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Mary Denigan-Macauley

Director, Health Care

List of Requesters

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable H. Morgan Griffith

Chairman

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Joyce, M.D.

Chairman

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Earl L. “Buddy” Carter

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gary Palmer

House of Representatives

This report (1) describes findings from literature and reports that discuss the reported outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern; and (2) examines the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) procedures for reviewing risk and risk mitigation strategies for research involving pathogens. We focused our review on HHS because the department leads the federal public health and medical response to potential biological threats and emerging infectious diseases, and associated research. Within HHS, we included the four agencies that fund or conduct research on pathogens: the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In the first objective, we focused on research that imparts new traits, removes existing traits, or enhances existing traits in a microorganism that could increase risk of morbidity or mortality in humans. We use the term gain-of-function research of concern to refer to this research because Congress, the media, and others frequently use this phrase in reference to this research. Our definition includes research that could directly increase the risk of morbidity or mortality in humans, such as research that adds, removes, or enhances a pathogen trait that could result in increased virulence or transmissibility in humans. It also includes research that could indirectly increase the risk of morbidity or mortality in humans, such as research that adds, removes, or enhances a pathogen trait that reduces animal or agricultural production, thereby harming economic output and the food supply. We developed this definition based on a review of research and policy articles as well as federal reports and policies on the oversight of higher risk research on pathogens.[69] We developed this definition to include pathogen research broader in scope than the research defined in these federal policies because these policies and definitions have changed over time. Other terms sometimes used to refer to such research include gain-of-function research, high-consequence research, and research on potential pandemic pathogens and enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.

To describe the reported outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern, we conducted a search in several bibliographic databases of peer-reviewed scientific journals for literature that discussed the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. These databases included Embase, MEDLINE, SciSearch, and Scopus. Our search included terms such as “gain-of-function research of concern,” “gain-of-function,” and “modified pathogen.” We included in our scope literature published from 2019 to 2024. We chose this period to include sources published 1 year prior to and 1 year after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of the 18 sources we identified as part of our literature search, we reviewed the full text of 14 sources based on a review of source titles and abstracts, if available, for information on the outcomes, risks, and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. Of these 14 sources, 11 contained information pertinent to our review: seven commentaries, two research articles, one e-book, and one news update.[70]

We also conducted a review of federal, international, and policy-related reports and policies, hereinafter referred to as biosecurity reports. We included in our scope biosecurity reports published from 2019 to 2024. We chose this period to include reports published 1 year prior to and 1 year after the COVID-19 pandemic. We selected biosecurity reports for inclusion in our review that met at least one of the following criteria: (1) discussed in detail the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern; (2) provided a framework for weighing the risks and benefits of this research; or (3) provided a framework for overseeing this research. We selected and reviewed a total of seven biosecurity reports, one of which was published outside the scope of our review (in 2016). For example, we reviewed: the 2022 National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan for Countering Biological Threats, Enhancing Pandemic Preparedness, and Achieving Global Health Security; 2022 World Health Organization Global Guidance Framework for the Responsible Use of the Life Sciences; and 2023 National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) report Proposed Biosecurity Oversight Framework for the Future of Science.[71] We also reviewed one NSABB report published in 2016 because the report summarized the results of an independent study, commissioned by NIH, on the risks and benefits of certain gain-of-function studies.[72] In addition, we reviewed an Executive Order published in 2025 because the order provided a framework for overseeing gain-of-function research of concern.[73]

For this objective, we refer to research, experiments, and studies as gain-of-function research of concern in instances where the literature and biosecurity reports did not explicitly use this term. For instance, some sources referred to gain-of-function research or experiments, gain-of-function research with pathogens of pandemic potential, research on potential pandemic pathogens, or research on enhanced potential pandemic pathogens. In other instances, sources detailed the specific techniques used to alter a pathogen in a particular experiment or study. To identify gain-of-function research of concern from these sources, we reviewed the descriptions or context of the research, experiments, and studies referenced and determined that they met our definition of gain-of-function research of concern. To identify outcomes, we identified any known and specific biomedical, research, public health, or national security-related result from this research. We considered outcomes that resulted directly from this research, such as a reported laboratory incident or the advancement of scientific knowledge on a particular pathogen, and those generated over time, such as a reported pandemic prevention or medical countermeasure to fight a specific disease.

To supplement information from our literature review, we interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of eight biosafety, biosecurity, and biomedical experts. We used a semi-structured interview format that included open-ended questions about the risks, benefits, and outcomes of gain-of-function research of concern and methods to identify and evaluate the risks and benefits of this research. Together, this nongeneralizable selection of eight experts collectively provided a range of perspectives on the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern.

To select these eight experts, we initially identified 31 experts that met at least one of the following criteria: (1) experts identified in our prior work; (2) current members of NSABB—a federal advisory committee that advises on issues related to biosafety and biosecurity oversight of biomedical research—with experience in the fields of infectious diseases and immunology; or (3) experts that published work on the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. Of the 31 experts, we interviewed four who published articles we identified through our literature search.

Of the remaining 27 experts, we interviewed four experts that met the following criteria: (1) had experience identifying and examining the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research of concern, and (2) provided a range of perspectives on the risks and benefits of this research. We reviewed publicly available information, such as biographical sketches, publications, and congressional testimony, to determine experts’ experience and perspectives related to gain-of-function research of concern.

For the first criterion, we determined that 24 of the 27 experts had experience conducting research on viruses or evaluating the risks and benefits of life sciences research, or work experience in the U.S. government in an area related to biosafety and biosecurity. For the second criterion, we determined that 15 of the 24 experts either emphasized the risks or benefits of gain-of-function research of concern. Specifically, we determined that eight of the 15 experts emphasized the risks of gain-of-function research of concern in publicly available information we reviewed. For example, these experts placed a greater emphasis on the biosafety and biosecurity risks of gain-of-function research of concern relative to its benefits; stated that there are limited or no benefits to this research or that the benefits are overstated; and advocated that this research requires additional federal oversight or that the federal government should prohibit or halt this research. We also determined that seven of the 15 experts emphasized the benefits of gain-of-function research of concern in publicly information we reviewed. For example, these experts stressed the importance of and need for gain-of-function research of concern; acknowledged the risks of gain-of-function research of concern but stated that this research is necessary for advancing scientific knowledge and developing medical countermeasures; and stated that alternative approaches do not yield the same benefits compared to gain-of-function research of concern. From the remaining 15 experts, we selected two experts that we determined represented each category of perspectives—emphasize benefits and emphasize risks (four experts total)—and had experience conducting research on potential pandemic pathogens or served on an institutional biosafety committee; and had experience working in the U.S. government related to biosafety and biosecurity.