BUREAU OF PRISONS

Actions Needed to Better Achieve Financial and Other Benefits of Moving Individuals to Halfway Houses on Time

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-26-107353

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Gretta L. Goodwin at GoodwinG@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) does not know how many individuals are currently in prison that could have already transferred to home confinement or a residential reentry center (RRC), also known as a halfway house. BOP officials said they do not know because the dates individuals are eligible to transfer are not readily available. GAO found that some individuals have remained in federal prisons despite being eligible to relocate to home confinement or an RRC. For instance, GAO found that BOP did not apply all the earned time toward placement in RRCs and home confinement for 21,190 of 29,934 individuals reviewed, for reasons such as insufficient RRC capacity and court orders. However, the full scale of this issue is unknown due to the lack of readily available data on eligibility dates. Until BOP maintains and monitors such data, it cannot ensure individuals transfer on time and take corrective action when timely transfers do not occur. As a result, BOP cannot ensure individuals receive the services and have the opportunities available at an RRC or home confinement, such as finding employment and long-term housing and reconnecting with the community. BOP has reported that such services can also help reduce recidivism.

Limited capacity in BOP contracted RRCs and home confinement spaces was a reason that individuals did not transfer on time, according to BOP officials. However, BOP does not know the full extent of this shortage because it has not comprehensively assessed its capacity and related budgetary needs. Without these assessments, BOP cannot ensure it has enough space for incarcerated individuals to transfer on time. BOP could also miss opportunities to increase revenues and decrease costs to the federal government. For instance, BOP said that individuals who have resided in an RRC are less likely to return to prison.

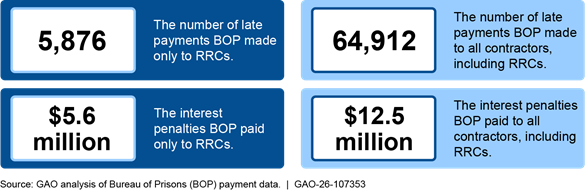

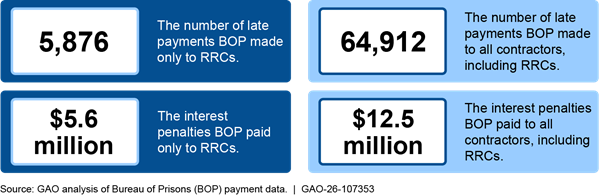

GAO also found that BOP made roughly 65,000 late payments to contractors, including RRCs, from fiscal year 2022 through March 2025. As a result, the agency paid $12.5 million in interest penalties as part of $2.8 billion in payments to contractors. In addition, GAO found that BOP paid RRCs late about 70 percent of the time, from fiscal years 2023 through 2024. RRC staff said they face hardships due to the late payments—needing private loans to pay staff. One RRC representative said late payments have made some RRCs reluctant to bid for new BOP contracts, which can further complicate BOP’s plans to expand capacity. By implementing a corrective action plan to address its late payments, BOP could save federal funds and better position itself to expand RRC capacity.

Why GAO Did This Study

BOP contracts with roughly 150 RRCs across the U.S. to help incarcerated individuals reenter their communities upon completion of their sentences. RRCs facilitate reentry services (e.g., employment services, drug treatment, and classroom education) to individuals who reside in RRCs or who are on home confinement. RRCs can help individuals rebuild ties to their community and reduce the likelihood that they will commit future crimes.

GAO was asked to review BOP’s use of RRCs. This report examines, among other things, how many individuals in BOP custody are eligible to transfer to RRCs and home confinement; the extent BOP knows its RRC capacity needs across the U.S.; and the extent BOP has paid RRCs and other contractors on time.

GAO reviewed relevant federal laws, BOP policies and documents, and BOP data on RRCs, including payments to contractors. In addition, GAO selected seven RRCs and three BOP field offices and interviewed residents and staff. GAO selected locations based on criteria such as geographic dispersion and the size of RRCs within an area. GAO also interviewed BOP officials responsible for residential reentry management and oversight.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations to BOP, including to maintain and monitor readily available data on RRC and home confinement eligibility dates, assess its RRC and home confinement capacity and budgetary needs, and implement a corrective action plan to address the causes of late payments. BOP concurred with our recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BOP |

Federal Bureau of Prisons |

|

RRC |

Residential Reentry Center |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 11, 2026

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Lisa Blunt Rochester

United States Senate

The Honorable Jon Ossoff

United States Senate

The Honorable Bobby Scott

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Rutherford

House of Representatives

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), a component within the Department of Justice, is responsible for the care and custody of roughly 155,000 incarcerated individuals.[1] The vast majority of these individuals are expected to complete their sentences and reenter their communities. To help individuals prepare to reenter their communities, BOP may transfer individuals to prerelease custody towards the end of their sentences. Transfers to prerelease custody involve moving an individual from a BOP prison facility to a residential reentry center (RRC)—also known as a halfway house—or home confinement.[2]

RRCs aim to help individuals prepare to reenter their communities by helping them find employment and housing, receive drug treatment, and attend job training, among other programs and services, while residing in a structured living environment. BOP contracts with RRCs to oversee both individuals residing in the RRC and individuals on home confinement. Generally, individuals on home confinement receive access to an RRC’s programs and services while residing at an approved location (e.g., a family member’s home) and under electronic location monitoring.[3] Roughly 12,000 individuals in BOP custody (8 percent of the total BOP population) resided in an RRC or on home confinement as of May 1, 2025, according to BOP officials.

Under the First Step Act of 2018 (First Step Act), certain incarcerated individuals may earn time credits, which may allow an individual to reduce the amount of time they spend in a BOP prison facility and increase the time they spend in prerelease custody.[4] As a result, eligible individuals may spend a greater percentage of their sentence at an RRC or home confinement than was possible in the past. We previously reported on BOP’s efforts to implement the First Step Act and the bureau’s efforts to assist incarcerated individuals in obtaining identification documents before reentering the community.[5] In addition, due to longstanding staffing and infrastructure challenges, leadership changes, and other challenges, we added Strengthening Management of the Federal Prison System to our high-risk list in 2023.[6]

You asked us to review BOP’s use of RRCs, including the use of RRC beds and RRC-administered home confinement. This report addresses (1) how many incarcerated individuals are eligible to transfer to RRC beds and home confinement, (2) the extent to which BOP has identified its RRC capacity needs across the U.S., (3) challenges BOP faces meeting RRC capacity needs, (4) the extent to which BOP has paid RRCs on time, and (5) the perspectives of selected residents on their experiences at RRCs. Throughout this report, the term RRC capacity includes RRC beds and RRC-administered home confinement.

To address the first four objectives, we evaluated BOP’s RRC policies and practices against relevant criteria, including the First Step Act,[7] the Prompt Payment Act,[8] GAO’s prior work on leading practices for modeling,[9] and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[10]

To address all five objectives, we reviewed relevant documents on BOP’s use, management, and oversight of RRCs, such as relevant bureau policies and guidance, and contracts. We also obtained and analyzed BOP data on RRC facilities, the RRC resident population, RRC capacity and use, and BOP payments to contractors. Specifically, we analyzed data on the RRC resident population from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024, to report on resident demographics and the amount of time residents spent in an RRC. We also analyzed BOP payment data from fiscal year 2022 to March 2025 to determine whether BOP has paid contractors, including RRCs, on time. We assessed the reliability of all relevant data and determined them reliable for our purposes.

We interviewed officials from BOP headquarters offices to better understand how BOP officials manage and oversee prerelease custody, including the associated data systems. We also selected and visited seven RRCs under the jurisdiction of the selected field offices to observe their operations and interview residents and staff. We selected these RRCs based on criteria such as geographic location and male-to-female resident ratio, among others. For each visit, we interviewed officials at the respective field office, as well as RRC representatives and facility staff, to obtain a localized perspective on RRC oversight and operations. Additionally, during our visits, we held nongeneralizable, semi-structured interviews with 37 RRC residents to obtain their perspectives on transferring to and living at an RRC. Further, using criteria such as geographic location, we selected and visited three BOP Residential Reentry Management Branch field offices. See appendix I for additional information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

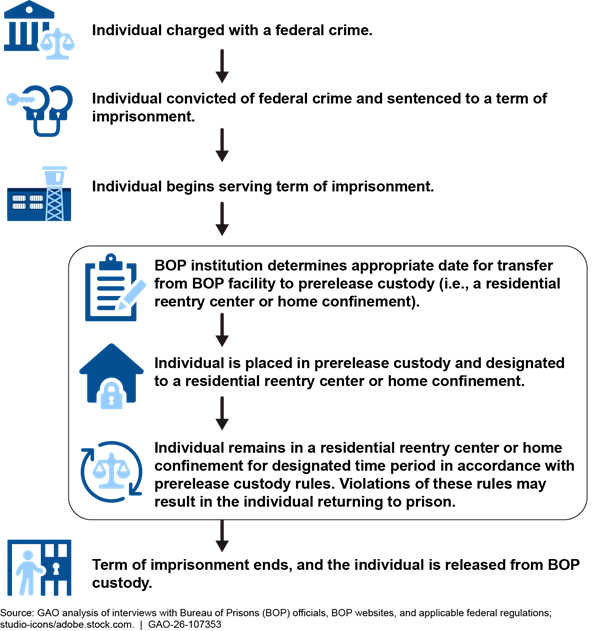

Prerelease custody generally involves placing incarcerated individuals in two supervised environments: RRCs and home confinement.[11] Placement in prerelease custody generally occurs toward the end of an incarcerated individual’s sentence and is intended to help facilitate that individual’s transition back into their community and help lower their risk of reoffending. Figure 1 provides an example of an individual’s path to an RRC or home confinement.

Figure 1: Example of an Individual’s Path to Prelease Custody, Including Residential Reentry Centers and Home Confinement

Note: Individuals living at a Residential Reentry Center or on home confinement are still considered to be under BOP custody.

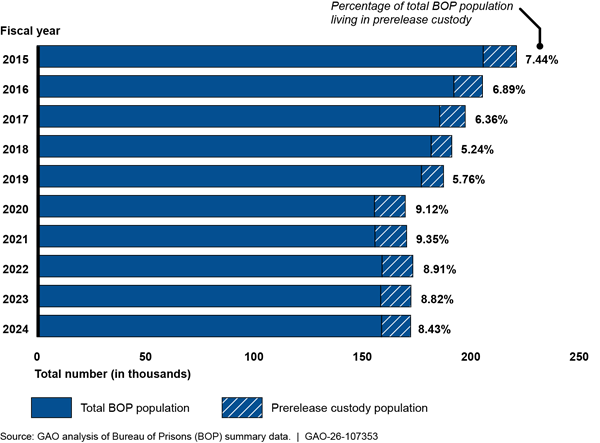

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the total BOP population that was living in prerelease custody on September 30 of fiscal years 2015 through 2024, as reported by BOP. For instance, the figure shows that the percentage of the BOP incarcerated population that was in prerelease custody ranged from a low of 5.24 percent on September 30, 2018, to 9.35 percent on September 30, 2021.

Note: This figure shows the BOP population, reported by BOP, including the percentage of the total in prerelease custody, as of September 30 of each fiscal year. According to BOP officials, policies and practices implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic could have impacted rates of prerelease custody.

Residential Reentry Centers. Individuals nearing the end of their sentence may be eligible to reside in an RRC.[12] Although individuals reside at the RRC, they are still considered to be under BOP custody. As of May 1, 2025, BOP had contracts with 155 RRCs that housed about 8,500 individuals under BOP custody. RRCs are contractually required to provide certain services and programs that help prepare residents for successful reentry into their community, such as employment-related training. In addition, RRC staff may work with companies and organizations to identify employment and other resources and services (e.g., mental health counseling, resume writing courses, and drug treatment) for RRC residents and individuals on home confinement.

RRCs serve men and women, and typically house them in separate, restricted areas. According to BOP, while residing in an RRC, residents are generally expected to obtain gainful employment and adhere to several rules, including adhering to a curfew, not using illegal drugs, and obtaining ‘leave passes’ before departing an RRC. Residents who violate rules may be sent back to a BOP prison facility to complete their sentences. According to BOP officials, after an RRC stay, residents generally transition to home confinement or are released to their communities.

Home Confinement. Individuals in prerelease custody may also spend a portion of their sentence on home confinement. Unlike RRC residents, individuals on home confinement reside at an approved location (e.g., a family member’s home) rather than an RRC.[13] As of May 1, 2025, BOP reported that roughly 3,400 individuals in its custody were on home confinement. BOP considers home confinement its least restrictive form of custody. Generally, according to BOP, individuals deemed suitable for home confinement are low risk for reoffending, have ties to their community, and have a stable support system. Staff who manage RRCs also manage home confinement.[14] For example, if a person is on home confinement in Chicago, then an RRC in the Chicago area may be responsible for the supervision of that individual, including electronic monitoring and in-person visits.

According to BOP’s standard RRC contract template, people on home confinement are also subject to RRC policies and requirements. For example, residents on home confinement must return to the RRC weekly to participate in routine activities and are generally tested for drug and alcohol use in the same manner and frequency as RRC residents. Further, they are required to remain in their home when not involved in approved activities, programming requirements, or employment.[15] RRC staff are contractually required to visit the resident’s home and place of employment at least monthly.

BOP Roles and Responsibilities

BOP’s Reentry Services Division consists of six branches that oversee the bureau’s reentry operations.[16] The Residential Reentry Management Branch, in particular, is responsible for administering contracts for community programs, such as RRCs. The branch includes 22 field offices that are responsible for reentry operations locally, including oversight of RRCs. According to BOP officials, these offices are generally staffed with a manager, contract oversight specialists, and residential reentry specialists. The staff’s primary responsibility is oversight of the RRCs assigned to the field office, including inspecting the centers for compliance with contractual requirements. In addition, BOP officials told us that Residential Reentry Management Branch field office staff manage daily office operations; oversee referrals to prerelease custody; key in movements within prerelease custody (e.g., RRC to home confinement); review discipline and escape reports; address complaints from individuals in prerelease custody; and process individuals for removal from prerelease custody, among numerous other tasks.

BOP is responsible for paying its contractors, including RRCs, for goods and services they provide. BOP’s payments are tracked and processed in the bureau’s Unified Financial Management System. Payment due dates vary by contract but are generally based on the date BOP received the good or service.[17] The Prompt Payment Act generally requires agencies to pay interest penalties if they are late and miss a given payment’s due date.[18]

Time Toward Prerelease Custody

Individuals in the custody of BOP may receive or earn time toward prerelease custody through the First Step Act,[19] the Second Chance Act of 2007 (Second Chance Act),[20] and the Residential Drug Abuse Program. Through these programs, individuals may reduce the time spent in a federal prison and increase their time spent in prerelease custody.

First Step Act of 2018. Under the First Step Act, eligible incarcerated individuals may earn time credits toward prerelease custody (i.e., RRCs and home confinement).[21] Generally, eligible incarcerated individuals may earn time toward prerelease custody when they arrive at their designated BOP facility and do not decline recommended programming, among other requirements. Further, pursuant to the First Step Act, incarcerated individuals can potentially earn 10 or 15 days of time credits for every 30 days of successful participation in evidence-based recidivism reduction programs or productive activities intended to help reduce recidivism.[22] For example, they can participate in drug abuse programs and support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous. The Act also states that the time credits shall be in addition to any other reward or incentives for which an incarcerated individual may be eligible.[23] Further, the Act requires the Director of the Bureau of Prisons to ensure there is sufficient prerelease custody capacity to accommodate all eligible incarcerated individuals.[24]

Second Chance Act of 2007. The Second Chance Act requires the BOP Director to ensure, to the extent practicable, that incarcerated individuals spend a portion of the final months of their terms of imprisonment, not to exceed 12 months, in conditions preparing them for community reentry.[25] To determine whether an individual is appropriate for RRC placement under the Act, BOP assesses them in accordance with five factors, including the nature of their crime and their history and characteristics.[26] In addition, according to BOP, time received under the Second Chance Act can be “stacked” with time credits earned under the First Step Act. According to BOP, this means that time received under both programs can be added together to increase the amount of time individuals could spend in an RRC or home confinement.

Residential Drug Abuse Program. By law, BOP is required to make available appropriate substance abuse treatment for each incarcerated individual that BOP determines has a treatable condition of substance addiction or abuse.[27] Per BOP policy, incarcerated individuals enrolled in BOP’s Residential Drug Abuse Program receive time in prerelease custody as part of their treatment. According to BOP, program enrollees live in a prison unit separate from the general population, participate in half-day programming and half-day work, school, or vocational activities. Further, according to BOP, the program typically lasts 9 months and generally requires enrollees spend an additional 120 days in prerelease custody. According to BOP, if an individual has received 120 or more days in prerelease custody from the First Step Act or Second Chance Act, then they will generally not receive any additional time in prerelease custody due to the Residential Drug Abuse Program.

BOP Does Not Know How Many Incarcerated Individuals are Eligible to Be in an RRC

BOP officials do not know how many individuals are currently in prison that could have already transferred to an RRC or home confinement. BOP officials told us they do not know because the dates incarcerated individuals are eligible to transfer are not readily available. As a result of this data limitation, BOP management cannot actively monitor whether individuals transfer on time and take corrective action when timely transfers do not occur.

Our review found that incarcerated individuals did not always transfer on time to an RRC or home confinement.[28] For example, some individuals did not receive all the First Step Act time credit they had earned, and some individuals were not provided Second Chance Act time because RRC or home confinement space were not available. Below is additional information on these examples:

First Step Act time credits not fully used. The First Step Act allows eligible incarcerated individuals to earn credits toward time in RRCs and home confinement (i.e., prerelease custody).[29] In January 2026, we reported that most individuals who earned time credits toward prerelease custody through the First Step Act were unable to use all the time credits they earned.[30] Specifically, we analyzed BOP data on individuals that had enough time credits to transfer to prerelease custody from March 31, 2024, to December 31, 2024.[31] We found that BOP did not apply all the earned time credits for 71 percent of these individuals (21,190 of 29,934 people). BOP officials reported that a lack of RRC and home confinement capacity was one reason that they did not apply all of a person’s earned time credits. In addition, BOP said there were other reasons. For example, some individuals may be delayed in transferring to RRCs and home confinement because of formal requests for custody from a federal, state, or local jurisdiction upon completion of a person’s current term of imprisonment (i.e., detainers).[32]

Second Chance Act time not fully awarded. BOP officials told us they do not award Second Chance Act time to an incarcerated individual if there is insufficient RRC bed and home confinement space. However, as discussed in greater detail below, the extent that this has occurred is unknown because BOP does not document the date a person could have transferred in a readily available format. BOP officials said they transfer individuals only if five factors are met, one of which is whether BOP has sufficient resources (e.g., RRC bed and home confinement space).[33]

According to BOP officials, they generally do not have sufficient RRC capacity and resources to accommodate all individuals eligible under the Second Chance Act, regardless of whether the individuals meet the other four factors. For instance, in March 2025, BOP advised staff that the maximum amount of time towards prerelease custody under the Second Chance Act would be reduced to 60 days (instead of 365 days, as allowed under the Act). This guidance included an exception for individuals in the Residential Drug Abuse program and female individuals releasing to a specific area. BOP said the changes were due to funding constraints associated with the continuing resolution for fiscal year 2025.[34] In April 2025, BOP reversed this guidance due to concerns about how these limitations could impact the incarcerated population. BOP officials told us that incarcerated individuals could now potentially receive the full 365 days.[35] However, BOP officials stressed that the days will only be provided if sufficient RRC beds and home confinement spaces are available. In the next section of this report, we provide additional information about why BOP does not always have sufficient RRC bed and home confinement spaces.

Although BOP officials acknowledged that there have been individuals in prison who could have transferred to an RRC or home confinement, the bureau does not know the scale of this issue. Specifically, in August 2025, we asked BOP how many individuals were currently in prison that could have already transferred to an RRC or home confinement. BOP officials told us that they could not answer the question because the data is not readily available. BOP officials said the information is not readily available because eligibility dates are documented in the individual records of incarcerated people, rather than a trackable information technology system. Thus, BOP officials said they would have to review the records for each incarcerated individual to identify the population.[36] Such a review could require examining tens of thousands of records.

BOP officials highlighted the complexity of determining a person’s eligibility date. For instance, as an incarcerated individual’s transfer date nears, they may commit an infraction that disqualifies them from an RRC or home confinement, or they may stop participating in recommended programs that provide First Step Act time credit. However, according to bureau officials, BOP staff ultimately determine when an incarcerated individual is eligible to transfer, but do not document this date in a readily available information technology system. In addition, as the data are not readily available, BOP cannot monitor across its prisons whether individuals are transferred on time, and if not, take corrective action.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agencies should design and implement controls to help achieve agencies’ objectives, which, in this case, is to transfer individuals to RRCs and home confinement on time. These standards also state that ongoing monitoring—such as regular oversight—should be performed continually during normal operations and that corrective actions be taken as necessary.[37]

Until BOP maintains and monitors readily available data on when individuals are eligible to transfer, it cannot ensure that individuals have timely transfers from prisons to RRCs and home confinement pursuant to the First Step Act and Second Chance Act. For example, the bureau cannot determine whether individuals currently in prison have past-due eligibility dates and take action to make the transfer as soon as feasible. Additionally, delayed transfers from prisons to RRCs can potentially decrease revenue to the federal government and increase costs, according to BOP officials. For example, incarcerated individuals may secure employment while in an RRC or on home confinement and ultimately earn money and pay taxes. BOP officials also stated that individuals are less likely to return to the federal prison system, after living in and attending programming in an RRC. In addition, based on our review of BOP data, we found that living in an RRC or on home confinement is generally less expensive than living in a federal prison. Specifically, we reviewed BOP’s analysis of the daily cost of living in a federal prison and an RRC. We found that overall, the cost was more expensive at a federal prison; however, sometimes a specific custody level (e.g., low or medium security) in a given fiscal year was less expensive than an RRC, according to BOP data.

Also, without readily available data, the bureau’s ability to plan for future RRC and home confinement needs is limited. For instance, if the bureau does not know the dates that individuals could have transferred to an RRC or home confinement under the Second Chance Act had RRC bed and home confinement space been available, then the bureau will be limited in its ability to determine how much space will be needed in the future.

BOP Does Not Have Enough RRC Capacity to Meet the Current Demand

BOP does not have enough RRC capacity, which includes RRC beds and home confinement spaces, to meet the current demand.[38] As a result, some individuals have stayed in prison who otherwise could have been transferred to an RRC or home confinement if sufficient space were available. As the First Step Act continues to be implemented, there will be an even greater demand for prerelease custody, according to BOP officials. However, BOP does not know the full extent of the shortage it faces because the bureau has not comprehensively assessed its RRC capacity and budgetary needs.

BOP Has a Shortage of RRC Beds and Home Confinement Spaces

Based on our analyses and interviews with BOP staff, we found that BOP does not have enough RRC capacity to meet the current demand. As discussed earlier, we found that BOP did not apply all the earned First Step Act time credits for some incarcerated individuals and was not always able to transfer individuals under the Second Chance Act due to a lack of resources. According to BOP, one reason was a lack of RRC and home confinement capacity.

For example, we found that BOP does not have enough RRC capacity in certain locations of the country. Based on our review of BOP census data, we found that BOP was using 8,169 RRC beds and 4,495 home confinement spaces as of September 30, 2024.[39] This represents 91 percent of total RRC beds and 121 percent of home confinement spaces under contract.[40] Of the 149 RRCs BOP had under contract as of September 30, 2024, 57 (38 percent) were at or above 95 percent capacity. Regarding home confinement, which is also administered by RRC staff, 92 RRCs (62 percent) were at or above 95 percent capacity.

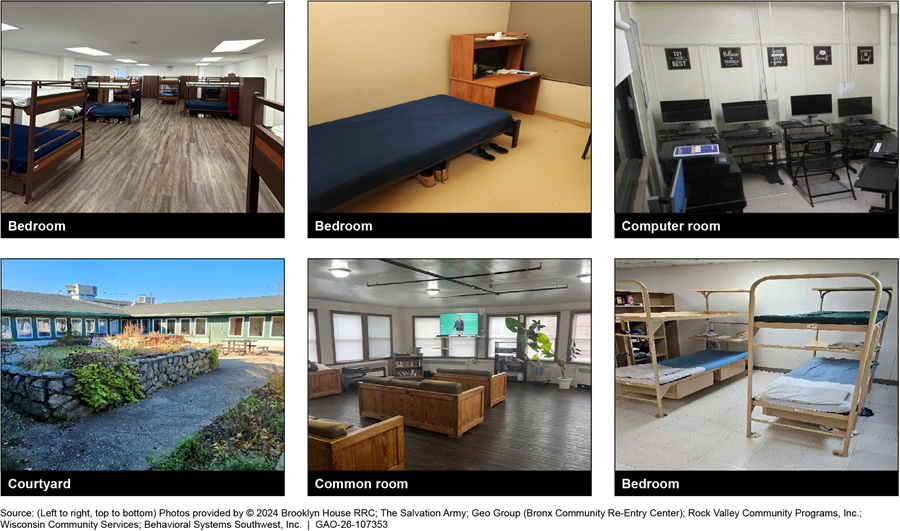

BOP officials said they have continuous discussions about certain areas where RRCs are consistently full and have waiting lists, and where BOP has received complaints that individuals only received their First Step Act time credits and no time pursuant to the Second Chance Act. BOP officials said they could transfer incarcerated individuals to locations that have availability, but that this would not help support the individuals’ transition back to their community. Specifically, according to BOP, placing individuals in prerelease custody outside of their community of return inhibits the goal of reentry, which is to find employment, housing, and other support structures that will facilitate the transition from incarceration to society. Figure 3 below provides examples of rooms and spaces typically found at an RRC.

BOP Does Not Know the Full Extent of the RRC Capacity Shortage

BOP does not know the full extent of its shortage of RRC beds and home confinement spaces because the bureau has not comprehensively assessed its RRC capacity and budgetary needs. Thus, BOP does not have a complete picture about which locations across the U.S. need RRCs, the number of beds and home confinement spaces needed in those locations, and how much money it will cost to meet these needs.

BOP uses its census data and a market analysis to help determine the needs of individual RRCs. However, we found that these actions are limited and not designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of prerelease custody needs. For example:

· According to BOP officials, they can review the bureau’s census data, which describe how many people are currently assigned to RRC beds and home confinement spaces, and the number of available beds and home confinement spaces. However, these data do not include information about how many people should be in an RRC or will be in an RRC in future years. For example, according to BOP officials, the data do not include individuals waiting in a BOP facility for an RRC bed or home confinement space to become available.

· Contracts between BOP and RRCs generally last 5 years, according to BOP officials. When BOP plans to enter a new RRC contract or renew an existing contract, staff perform a market analysis to help forecast the capacity and budgetary needs of the individual contract.[41] However, according to BOP officials, the model is not used to determine (nor is it designed to determine) BOP’s RRC needs across the country. As described in greater detail later in the report, we also found that the model is not consistent with leading practices for models.

The First Step Act, Second Chance Act, and BOP’s Residential Drug Abuse Program provide eligible incarcerated individuals an opportunity for placement in prerelease custody. In addition, the First Step Act requires the Director of the Bureau of Prisons to ensure there is sufficient prerelease custody capacity to accommodate all eligible incarcerated individuals.[42]

However, according to BOP officials, they do not know the extent of their current or future RRC capacity and budgetary needs because they have not conducted an assessment. For example, the bureau has not comprehensively assessed how many individuals will be eligible for prerelease custody and where they plan to release and then determined the RRC locations and space needed to meet that demand. In addition, as BOP has not determined its capacity needs, it has also not assessed the related budgetary needs. Rather, BOP officials told us they generally start with their RRC budget and then they determine how many RRC beds and home confinement spaces can be purchased in the fiscal year.

According to BOP, RRCs help incarcerated individuals gradually rebuild their ties to the community and provide programs that help reduce the likelihood that they will commit crimes in the future. In addition, as a result of the First Step Act, individuals will continue to earn more and more time credits, according to BOP officials. Thus, the shortage could worsen in future years. Without more comprehensively determining RRC capacity and budgetary needs, BOP officials cannot know and plan for the full extent of the bureau’s RRC capacity and budgetary needs. This can limit the bureau’s ability to ensure there is sufficient space for incarcerated individuals to use their earned time credits towards prerelease custody.

In January 2026, after reviewing a draft of this report, BOP reported access to new tools (e.g., a First Step Act time credit calculator) that improve the bureau’s ability to conduct more accurate forecasting. According to BOP officials, these tools, which were unavailable at the outset of GAO’s audit, have better positioned BOP to conduct informed RRC capacity and budgetary planning. For example, BOP officials said they will comprehensively identify BOP’s capacity needs for the fiscal year 2027 budget request. Due to when GAO received this information, we have not yet confirmed BOP’s reporting via documentation. However, officials further noted it is unlikely that forecasting will ever be 100 percent accurate due to a range of factors. For example, BOP said it cannot factor in unknowns, such as whether home confinement will be an appropriate placement option for an incarcerated individual—whether the individual will have viable residences, security concerns, or medical conditions. See additional discussion in appendix III.

BOP Has Not Taken Key Actions to Help Address RRC Capacity Challenges

BOP officials reported several challenges to ensuring sufficient capacity in prerelease custody exists as required by the First Step Act. For example, bureau officials told us that implementing the First Step Act increased demand, and funding constraints have made it difficult to ensure there are enough RRC beds and home confinement spaces. Although BOP has taken some steps to help address capacity challenges, we found that the bureau has not taken two key actions. Specifically, the bureau has not (1) developed a plan to address known capacity challenges, and (2) followed all leading practices we reviewed for developing and assessing models to determine its capacity needs for individual RRC contracts.

BOP Reported Resource and Other Challenges to Ensuring Sufficient RRC Capacity

BOP officials reported challenges to ensuring sufficient RRC bed and home confinement spaces for everyone who is eligible. However, we found that BOP does not currently have a plan to address these challenges. Below are challenges that BOP officials and staff reported:

· Increased demand. The First Step Act increased the number of time credits individuals can have toward RRC stays and home confinement. Several BOP officials told us that, as a result, the demand for RRC beds and home confinement spaces has increased. In addition, this challenge is expected to grow as the demand for prerelease custody increases, according to BOP. Specifically, as the First Step Act continues to be implemented, eligible incarcerated individuals will continue to earn more and more time credits, allowing them to spend a greater percentage of their sentence in RRCs and home confinement.

· Funding constraints. BOP officials said that funding constraints are a significant challenge. Bureau officials told us the constraints make it difficult to (1) generate more RRC availability—such as helping RRCs open new facilities or expand capacity at existing facilities—and (2) use RRC beds and home confinement spaces that already exist. For example, BOP officials said they have continuous discussions about areas where RRCs are consistently full. However, bureau officials told us they lack the funding to expand in these areas. In addition, bureau officials said many facilities can accommodate individuals over and above contracted amounts, but BOP sometimes does not have enough funding to send incarcerated individuals to RRCs that have beds available.

· Staffing challenges. BOP officials told us that expanding the number of RRCs would also require more BOP staff dedicated to RRC oversight. For example, BOP officials said the bureau may need additional staff to help develop and award new RRC contracts, to inspect RRCs, and be available when residents run into issues. Additionally, if there are pervasive issues at an RRC, such as drug use or security concerns, then BOP staff may need to visit the RRC and address the situation, according to BOP officials.

BOP officials also said the First Step Act has led to further strain on staff and resources—thereby hampering expansion efforts. For example, implementation of the Act brought new complexities in managing RRC and home confinement placements. BOP officials said that individuals may have detainers, significant mental and medical health needs, and other case management challenges that require more oversight and considerations than was previously needed. In addition, BOP officials said they have encountered challenges managing time credit issues (e.g., the potential miscalculation of First Step Act time credits) and other credit-related concerns that further strain resources. Further, limited staff availability and budget constraints have made it difficult to travel to existing RRC sites for proper onsite oversight, according to BOP officials.

· Other challenges. BOP officials highlighted other challenges that they face, particularly during expansion efforts. For example, BOP officials told us that both the bureau and potential RRCs can face opposition from local residents who do not want RRCs built near or in their communities. Also, it can be challenging to ensure there are enough supportive services in the area, such as access to jails, U.S. Marshals Service support, and transportation options to assist with RRC operations.[43]

BOP officials have taken some steps to help address these challenges. For instance, BOP officials said that as the budget allows, they have been willing to contract with new RRCs for beds and home confinement spaces. Also, in areas where it would be too expensive or impractical to open an RRC, BOP officials told us they have contracted with day reporting centers.[44] For example, BOP opened a day reporting center in Hawaii on February 1, 2024.

Also, in July 2025, the BOP Director established the First Step Act Task Force to, among other things, help increase the timeliness of home confinement placements under the First Step Act and Second Chance Act. According to BOP, the group will work directly with Residential Reentry Management Branch field offices to identify RRC residents who may be eligible for home confinement and to provide home confinement placement dates to facilitate timely transitions. Additionally, BOP issued two memos, in May 2025 and June 2025, that emphasized the importance of transferring incarcerated people to home confinement, if eligible.[45] BOP officials noted that as this is implemented, there may be an increase in the number of people who are transferred to home confinement, which may result in additional bed spaces that are available in RRCs.

Despite these steps, the aforementioned challenges remain. In addition, the bureau has not developed a holistic plan to address these challenges and ensure it ultimately reaches the needed RRC capacity. The First Step Act requires the BOP Director to ensure there is sufficient prerelease custody capacity to accommodate all eligible individuals.[46] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agencies should monitor program performance and progress, ensure that corrective actions are identified and assigned to the appropriate parties, and ensure that corrective actions are tracked until the desired outcomes are achieved.[47]

By developing and implementing a plan to address its capacity challenges—including timeframes, roles, and responsibilities for doing so—the bureau will be better positioned to ensure availability, including expanding RRC capacity as needed. This can help ensure individuals transfer to RRCs and home confinement on time and receive programming and services that help aid a successful reentry to the community and potentially reduce recidivism. Reaching a sufficient level of prerelease custody capacity could also potentially save the federal government millions of dollars and help ease the staffing crisis currently facing BOP. For instance, the bureau has identified funding and staffing constraints as challenges to transferring individuals to RRCs. As discussed earlier, ensuring individuals transfer to RRCs and home confinement on time could potentially increase revenues and decrease costs to the federal government. In addition, transferring more individuals from prisons to RRCs and home confinement could, over time, help reduce the number of BOP staff required to oversee and support individuals while they are in federal prisons.

BOP’s Market Analysis is Not Consistent with Some Leading Practices for Modeling

When BOP plans to enter a new RRC contract, or renew an existing contract, staff perform a market analysis. According to BOP, this analysis is initiated about 2 years prior to when services are expected to begin because the procurement process for RRCs typically takes approximately 2 years. According to BOP officials, the analysis helps BOP forecast how many RRC beds and home confinement spaces will be required in future years under the contract.[48] Contracts between BOP and RRCs generally last 5 years, according to BOP officials. Thus, the market analysis is central to ensuring there is appropriate RRC capacity over the life of the contract.

However, we found that BOP’s market analysis is inconsistent with two of the three selected leading practices for developing and assessing models that we analyzed. GAO has previously identified elements of an effective model—a model such as BOP’s market analysis—that are generally considered to be leading practices.[49] Specifically, an entity should (1) have a clear written description of model assumptions, limitations, inputs, outputs, and the general type of model, (2) verify the model is running as intended by its developers, and (3) validate that the model is providing results consistent with data external to the model itself.[50]

According to BOP officials, the bureau has a process to verify the market analysis is running as intended—one of the three leading practices we reviewed. Specifically, the local Residential Reentry Management Branch field office staff are to collect and review the analysis and then forward the information for review to Reentry Services Division leadership before submission to BOP contracting officers. However, we found that BOP’s market analysis is not consistent with the other two leading practices we reviewed: description and validation.

· Description. According to BOP officials, the bureau began using a standard template to help staff conduct the market analysis in 2023. However, this template did not include a written description of the assumptions, limitations, inputs, and other descriptions generally consistent with leading practices.

· Validation. BOP officials told us the bureau does not have a process that it uses to validate the accuracy of data and other information gathered in the market analysis, such as sentencing trend data provided by external entities. BOP officials said they monitor the average daily population of RRCs, but BOP does not compare this information to previous market analysis estimates to validate the measures. We found, for example, that 31 RRCs (21 percent) are using 60 percent or less of available home confinement space. This could indicate that the demand for home confinement is lower in some areas than BOP planned for.

BOP officials said that more structured documentation might make the process more transparent and easier to understand for outside observers. However, bureau officials also said that staff know how to do the analysis with the existing process. In addition, BOP officials told us they do not track the accuracy of the market analysis because the information established from it will never be exact. For example, BOP officials said it cannot factor in unknowns, such as legislative changes resulting in sentence reductions or increases in prosecutions; pardons and sentence commutations; and whether incarcerated individuals eligible for home confinement will have viable residences, security concerns, or medical conditions. These factors, according to BOP officials, impact market research predictions and may result in inaccurate estimates. Although forecasting may not be exact, we have found that taking steps to validate a model can increase its accuracy.

By aligning the market analysis with leading practices, BOP can better ensure that staff are producing accurate and reliable estimates over the life of RRC contracts. Taking these steps can help ensure the bureau’s market analysis will yield accurate results on how much RRC capacity is needed. In addition, these steps can also potentially lead to cost savings for the federal government by helping BOP ensure it purchases an appropriate number of RRC beds and home confinement spaces.

BOP Typically Paid RRCs and Other Contractors Late, Resulting in Millions in Interest Penalties

We found that BOP paid RRCs late about 70 percent of the time from fiscal years 2023 through 2024, based on our review of the bureau’s payment data.[51] BOP made roughly 5,900 late payments—worth $1.1 billion total—to RRCs from fiscal year 2022 through March 2025, based on our review of the bureau’s payment data.[52] As a result of these late payments, BOP paid $5.6 million in interest penalties to RRCs. The late payments were 66 days late, on average, but in some cases were almost 1,200 days late. For example, 23 payments were more than 2 years late. The average interest penalty per late payment was roughly $950, though penalty amounts were as high as $20,000 for a single payment.

We also analyzed BOP payments made to all its contractors, including RRCs, and found that the bureau made about 65,000 late payments from fiscal year 2022 through March 2025. These payments totaled $2.8 billion and were, on average, 54 days late. Additionally, 92 payments were between two and three years late and one payment was almost 11 years late.[53] As part of these payments, BOP paid $12.5 million in late payment penalties to its contractors. The average interest penalty per late payment over this period was about $193, and one payment reached as high as $92,000. Figure 4 shows the number and interest penalty costs of BOP’s late payments.

Figure 4: BOP Late Payments to Residential Reentry Centers (RRCs) and Other Contractors, October 2021 - March 2025

RRC staff we interviewed highlighted challenges that stemmed from the late payments. For instance, leadership at one RRC told us they had to secure private loans to ensure staff received their paychecks. Representatives of another RRC said that the late payment interest paid by BOP to the RRC did not cover the interest on the RRC’s bank loans. They added that some RRCs will not renew contracts with BOP due to the late payment issues. BOP officials told us they had also heard about challenges that RRCs faced. For instance, RRCs told BOP they had to borrow funds from other parts of their organization, obtain financing (e.g., a bank loan), and defer needed repair work to pay their bills. Also, at times when RRCs were waiting for payment, some RRCs told BOP they were struggling and would not be able to keep operating without payment.

According to BOP officials, late payments “can be attributed to several factors, many of which are influenced by the complexities of the program and funding processes.” BOP officials pointed to staffing challenges, continuing resolutions, and a transition to a new financial system as potential reasons for the late payments.[54] For instance, BOP officials told us that in 2022, the bureau converted from a legacy payment system to the Unified Financial Management System—the system currently in use.[55] According to BOP officials, the bureau had challenges with the deployment of the new system, such as technical problems and needing to train staff on how to use it, and these problems delayed some payments. BOP officials also told us that these issues were resolved by 2024; however, we found that late payments continued in the first 3 months of 2025.[56]

By regulation, each agency head is responsible for ensuring timely payments and payment of interest penalties where required.[57] Pursuant to the Prompt Payment Act, agencies generally owe interest on payments for goods or services made to businesses after the due date.[58] Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agencies should monitor program performance and progress, ensure that corrective actions are identified and assigned to the appropriate parties on a timely basis, and ensure that corrective actions are tracked until the desired outcomes are achieved.[59]

However, BOP officials told us they have not developed or implemented a corrective action plan—that includes timeframes and identifies individuals responsible for taking actions— to address the root causes of BOP’s late payments. Until BOP develops and implements such a plan, late payments may continue to negatively affect the operations of RRCs and other contractors, RRC residents, and BOP. For instance, should these payments lead to RRCs ending or foregoing bidding for future contracts, BOP may continue to face challenges ensuring sufficient RRC and home confinement capacity. Residents of RRCs that ultimately end their contracts would need to transfer to a new RRC, which may disrupt their transition back to the community. In addition, the millions of dollars BOP spends on interest penalties could be used to address other funding challenges the bureau faces (e.g., funding additional RRC beds).

Selected Residents Reported a Range of Perspectives on RRCs

RRC residents we interviewed reported a range of experiences transferring to and living in an RRC. Overall, 17 of the 37 residents we interviewed told us that their time at an RRC was preparing them to reenter the community, while 13 told us it was not preparing them and seven did not specify whether it was or was not preparing them. More specifically, residents discussed: their experience transferring from BOP facilities (i.e., federal prisons) to an RRC, the benefits and challenges of living at an RRC, and their views on the RRC complaints process. These interviews are not representative of the entire population residing in BOP-contracted RRCs. However, the anecdotal information we learned during these interviews provided valuable insights and illustrative examples about individuals’ experiences. Also, it was not within the scope of our review to independently verify the veracity of the individuals’ statements from our interviews. In accordance with our policy, we have referred information related to certain statements made during these interviews to the Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General, as appropriate.

Below is a summary of the residents’ responses:

Experience Transferring to RRCs

Residents we interviewed shared information about the process of transferring from a BOP facility to an RRC. Below is a summary of the responses:

RRC Location. Twenty-eight of the 37 residents we interviewed told us that the RRC they were transferred to was not in the community where they eventually wanted to live. For example, one resident was told by a case manager that no beds were available at their desired RRC and so the resident was placed at a different RRC. We heard a range of reasons during our interviews why it could be beneficial for a resident to be placed in the area they hope to eventually live. For example, one resident told us that their RRC was far from home and the distance prevented them from seeing family.

Timeliness of Transfers. Nineteen of the 37 residents reported that transfers from BOP facilities to an RRC took place on time and as expected, while 17 residents reported that their transfers experienced a delay.[60] Of those 17 residents, fifteen said their BOP case managers were responsible for the delay and five cited paperwork-related delays.[61] For example, one resident told us they had enough time credits to transfer earlier, but their case manager had not submitted the RRC referral on time. Another resident told us that errors in the paperwork caused the delay. Specifically, they were not released to home confinement on time because their case manager failed to properly document that they had an eligible home to be placed at. Additionally, three residents said they were told that their designated RRC did not have enough beds to receive them on time.

Benefits of Living at an RRC

Residents we interviewed also told us about benefits of living at an RRC. Below are themes we most often heard from residents during these interviews:[62]

Supportive staff. Twenty of the 37 residents we interviewed said they had positive experiences with RRC staff.[63] For example, one resident described RRC staff as respectful and credited staff with helping the resident find employment and housing opportunities. Another resident said that staff were fair to everyone at their RRC. Seven residents described staff as respectful.

Employment opportunities and training. Twenty-two residents reported that they found the employment opportunities and resources available at their RRC, such as resume writing courses, beneficial. For example, one resident said their employment during the RRC stay could help set them up for a long-term career, while another said time at an RRC allowed them to save money. A third resident said they were learning how to use computers and cellular phones and characterized the opportunity as “catching up.” Five residents said their RRC helped them obtain licenses or certifications to work in fields like construction.

Reacclimating to life in the community. Eight residents described how their time at an RRC was helping them adjust to life after prison. For example, one resident said their RRC stay was helping them become more independent, while another said their RRC is a good place for them to “get their life back together.” Two residents cited the opportunity to reconnect with family and friends as a significant benefit of living at an RRC. For example, one resident described how living at an RRC gave the opportunity to reunite with family and rebuild relationships with them. RRC staff from three different RRCs told us that passes to spend time outside the center with their families provided an incentive to residents to work and integrate back into their communities.

Challenges Associated with Living at an RRC

RRC residents also described challenges associated with living at an RRC. Below are themes we most often heard from residents during these interviews.[64]

Application of RRC rules. Residents expressed concerns with overly restrictive rules at some RRCs and with inconsistent enforcement of rules. Eleven of the 37 residents said that rules around commute times were too restrictive given challenges with local transportation options, and two residents said that a bus running late could result in an RRC reporting the residents as having escaped. Additionally, five residents told us that their RRCs did not consistently enforce rules. For example, one resident told us that their RRC only enforced some rules such as where residents are allowed cigarette breaks, and another said that the enforcement of rules was inconsistent and unpredictable.

Poor interactions with staff. Fifteen of the 37 residents we interviewed said they had poor interactions with RRC staff. For example, eight residents described RRC staff as disrespectful, unprofessional, or rude, while one resident said that staff added stress to their life and were not helping prepare them for reentry. A resident reported that staff overstepped their authority, and a different resident said they felt staff were always out to punish residents.

Transportation. We asked residents about transportation to and from RRCs and related challenges. Twenty-one of 37 residents told us they rely primarily on public transportation, while 13 described other options, including family or friends, personal vehicles, rideshare, or vans paid for by Medicaid or operated by the RRC itself.[65] Residents added that their method of transportation may impact their ability to follow their RRC’s rules. For example, 10 residents told us that their transportation may deliver them to their RRC late, which can result in rule violations. Two more residents described their transportation as generally unreliable.

Limited resources. Fourteen residents said their RRCs did not have the resources they were seeking, such as programming and employment opportunities. For example, one resident said there were not many jobs available near the RRC, yet their RRC only assisted with obtaining a selection of locally available jobs. Another resident said they would benefit from additional programming like courses on financial literacy. Seven residents said that they wanted their RRC to provide more mental or physical health care.

Experience with Complaints Process

RRC residents also discussed their experiences with submitting RRC-related complaints to BOP. According to BOP officials, their main method of collecting feedback from RRC residents is through the administrative remedy program. As part of the program, residents complete a complaints form that RRC staff forward to BOP.[66] Twenty of 37 residents we interviewed said they were aware of the steps required to file a complaint with BOP, while 15 told us they were unaware.[67] Additionally, 18 of 37 residents told us they had at least once wanted to file a complaint but decided not to for a variety of reasons.[68] For example, six residents reported a fear of retaliation from RRC staff (e.g., being returned to prison) for filing a complaint, five residents told us that they did not believe the process would successfully lead to the change they sought, and four residents said they did not want to spend the time the process requires.

Additionally, RRC residents have other options to submit concerns or formal complaints, such as:

· BOP requires staff to conduct inspections of RRC facilities multiple times each year. According to BOP officials, BOP staff use a prepared questionnaire to interview residents during these inspections on their experience at the RRC. Residents can discuss concerns or complaints during these interviews. In addition, BOP officials told us that inspection staff can provide residents a voluntary one-page survey that the residents can complete and return anonymously. According to BOP policy, a major RRC is required to have one full inspection each fiscal year, and three interim inspections before the next full inspection.[69] Each of the seven RRCs we visited was considered a major RRC. BOP reported completing the 28 required inspections from December 2023 to January 2025, and we reviewed the related inspection reports to help confirm the completion of the inspections.

· The Statement of Work that BOP includes in all RRC contracts requires that RRCs have a grievance system in place, post the grievance process in a place accessible to all residents, and provide the necessary forms, including BOP’s BP-9 complaint form.[70] As part of the required grievance system, RRCs can have internal processes, such as complaining directly to RRC staff, as an option for residents to submit complaints.

· According to BOP officials, RRCs are required to post contact information for the local BOP field office in the view of residents. Residents may reach out directly at their discretion.

Conclusions

Prerelease custody plays a vital role in preparing incarcerated individuals to successfully return to their communities and in reducing the likelihood of reoffending. Time in prerelease custody helps individuals to find employment and housing and to reacclimate to life outside prison, before being released from BOP custody. However, BOP lacks readily accessible data on how many incarcerated individuals had enough time credits and incentives to transfer to an RRC or home confinement. In addition, BOP faces a shortage of prerelease custody capacity, and the demand is expected to increase as implementation of the First Step Act continues. Until BOP maintains readily available data on eligibility dates, more comprehensively assesses its RRC capacity needs, and develops a plan to address known capacity-related challenges, the bureau cannot ensure that it is meeting the legal requirement to ensure sufficient capacity to accommodate all eligible incarcerated individuals and providing individuals with all the benefits they have earned. This could result in some individuals remaining in prison longer than required, missing opportunities to receive reentry programming and services offered by RRCs.

In addition, updating its market analysis model to align with leading practices will help BOP ensure the accuracy of its analyses, which can, in turn, better ensure sufficient capacity exists for individuals to transfer as soon as they are eligible. As RRCs and home confinement are generally less expensive than the average cost of operating federal prisons, these actions could also potentially save the federal government millions of dollars. Further, BOP has a history of making late payments to RRC contractors. Developing and implementing a corrective action plan to address the causes for these late payments could help BOP avoid unnecessary interest payments. Additionally, avoiding late payments could help BOP maintain the RRC relationships necessary to meet the growing demand for the prerelease custody.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following seven recommendations to BOP:

The BOP Director should maintain readily available data on the dates incarcerated individuals are eligible to transfer to RRCs or home confinement, across the bureau. This includes the eligibility date pursuant to the First Step Act, Second Chance Act, and any other incentives or benefits available to incarcerated individuals regardless of the availability of RRC and home confinement space. (Recommendation 1)

The BOP Director should monitor, across the bureau, whether individuals transfer to RRCs and home confinement on time, and if not, take corrective action. (Recommendation 2)

The BOP Director should more comprehensively assess its RRC capacity needs, including locations and number of RRC spaces. The assessment should consider all time available to incarcerated individuals for prerelease custody, including time under the First Step Act, Second Chance Act, and the Residential Drug Abuse Program. (Recommendation 3)

The BOP Director should, after determining RRC capacity needs, determine the related budgetary needs. (Recommendation 4)

The BOP Director should develop and implement a plan—including timeframes, roles, and responsibilities—for addressing known challenges in reaching a sufficient level of prerelease custody capacity. (Recommendation 5)

The BOP Director should ensure its market analysis for RRC contracts is aligned with leading practices for developing and assessing models. (Recommendation 6)

The BOP Director should develop and implement a corrective action plan that addresses the root causes of BOP’s late payments to contractors. The implementation plan should include timeframes and identify individuals responsible for taking corrective actions. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Justice and BOP for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, BOP concurred with our recommendations and provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and members, Department of Justice, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have questions about this report, please contact me at GoodwinG@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Gretta L. Goodwin

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

The objectives of this report are to examine (1) how many incarcerated individuals are eligible to transfer to residential reentry center (RRC) beds and home confinement, (2) the extent to which the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has identified its RRC capacity needs across the U.S., (3) challenges BOP faces meeting RRC capacity needs, (4) the extent to which BOP has paid RRCs on time, and (5) the perspectives of selected residents on their experiences at RRCs.

To address all five objectives, we reviewed relevant laws, regulations, and BOP documents on the use, management, and oversight of RRCs (e.g., bureau policies and guidance and RRC contracts).

We interviewed officials from BOP headquarters offices to better understand how BOP officials manage and oversee prerelease custody, including the associated data systems. We also interviewed officials at selected BOP Residential Reentry Management Branch field offices, as well as RRC representatives and facility staff, to obtain a localized perspective on RRC oversight and operations. We selected and interviewed officials at three Residential Reentry Management Branch field offices. We conducted in-person interviews with two offices and virtual interviews with one office. We also selected and visited seven RRCs to observe their operations and interview residents and staff. To gather additional insights, we also selected two RRCs for virtual interviews. To select RRCs and Residential Reentry Management Branch field offices, we reviewed BOP’s list of 22 field offices and applied criteria such as geographic location, available resources, and certain demographics. Upon identification of field offices to include in our scope, we reviewed the list of the operational RRCs under each office’s jurisdiction. We applied criteria such as capacity and male-to-female resident ratios to each list, resulting in the selection of two to three RRCs per selected field office. Applying said criteria provided variety across the seven centers we ultimately selected, including among residents and locations (e.g., urban or rural).

To address objectives one through four, we evaluated BOP’s RRC policies and practices against relevant criteria, including the First Step Act of 2018,[71] the Prompt Payment Act,[72] GAO’s prior work on selected leading practices for modeling such as validation,[73] and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[74] Specifically, we assessed BOP’s current RRC capacity level against the First Step Act requirement to ensure sufficient prerelease custody capacity to accommodate all eligible incarcerated individuals.[75] We reviewed our prior work on modeling and internal control standards to assess the sufficiency of BOP’s forecasting model and forecasting approach. We determined that the monitoring component of Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government was significant, along with the underlying principle that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results. Specifically, agencies should monitor program performance and progress.

To assess the timeliness of payments made to contractors, including RRCs, we obtained and analyzed payment data from the Unified Financial Management System from October 2021 to March 2025. We compared data on on-time payments in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 to data on late payments made during the same period. We also analyzed data on late payments from fiscal year 2022 to March 2025. For example, we conducted calculations to identify specific data points, such as the total value of interest penalties paid during the specified period. BOP confirmed that the data set GAO received included all late payments BOP had made from October 2021 to March 2025 and all on-time payments BOP had made from October 2022 to September 2024.[76] To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed the data for errors and missing values and obtained written responses to questions. We also conducted interviews with cognizant officials to ensure the accuracy of our understanding of the payment data. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on the number of late payments made to contractors, including RRCs, and the amount of interest penalties paid to all contractors, including RRCs. To assess BOP’s efforts to address late payments, we reviewed internal control standards. We determined that the monitoring component of Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government was significant, along with the underlying principle that management should remediate identified internal control deficiencies on a timely basis. Specifically, agencies should ensure that corrective actions are identified and assigned to the appropriate parties and ensure that corrective actions are tracked until the desired outcomes are achieved.[77]

To address objective five, we conducted nongeneralizable, semi-structured (voluntary) interviews with 37 RRC residents. We randomly selected individuals residing in RRCs at the time of our site visits to obtain their perspectives on their experiences transferring to and living at an RRC. To identify individuals, we requested RRC rosters for selected locations from BOP and identified individuals with release dates within 6 months of our site visit. We analyzed their responses to identify key themes, as well as illustrative anecdotes, from their experiences at RRCs.

To describe the RRC resident population from fiscal years 2021 to 2024, as presented in appendix II, we obtained and analyzed movement data from BOP’s SENTRY Inmate Management System.[78] The scope of our analysis included individuals who were placed by BOP in an RRC for prerelease custody from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024. For the purposes of our analysis, we considered an individual placed in an RRC if they spent at least one overnight there. We excluded individuals who were never placed in an RRC (e.g., direct to home confinement or community confinement case only). We also excluded movements occurring after an individual’s release from BOP custody (for those who released). If an individual had more than one record indicating release from BOP custody, we selected the release from BOP custody occurring soonest after his or her first RRC stay.

To determine how long individuals in the aforementioned population stayed in the RRC, we totaled all consecutive and nonconsecutive days stayed in an RRC. For those currently in an RRC at the time the data were extracted, we used the date the data were extracted as the end date to calculate the individual’s length of current stay in an RRC. To assess the reliability of SENTRY data used for appendix II, we performed electronic testing for missing values and obvious errors and discussed the data with BOP officials. We also validated the list of RRCs identified in SENTRY using a list of operational RRCs provided by BOP to help us determine when an individual was in an RRC. In addition, our testing identified 812 individuals who had multiple movements with overlapping dates for which BOP officials were unable to provide correct information. We excluded these individuals from our analysis because we were unable to determine which movement and dates were correct. We do not anticipate this having a material impact on our analysis.

We determined the SENTRY data were sufficiently reliable for determining key characteristics about the individuals who entered an RRC, such as the number and demographics, length of stay in an RRC, and resident movements (e.g., releases from BOP custody).

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions on our audit objectives.

The tables below show our analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data on individuals who entered a residential reentry center (RRC), from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024.

Table 1: Gender of Individuals in BOP Custody Who Entered a Residential Reentry Center from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024

|

Gender |

Number of Individuals |

Percent of Total |

|

Male |

69,852 |

89.3% |

|

Female |

8,381 |

10.7% |

|

Total |

78,233 |

100% |

Source: GAO Analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data. | GAO‑26‑107353

Note: Table 1 includes individuals who entered a residential reentry center and stayed for at least one night from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024. The data were current as of July 27, 2024.

Table 2: Race of Individuals in BOP Custody Who Entered a Residential Reentry Center from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024

|

Race |

Number of Individuals |

Percent of Total |

|

White |

41,665 |

53.3% |

|

African American |

33,367 |

42.7% |

|

American Indian |

2,200 |

2.8% |

|

Asian American and Pacific Islander |

1,001 |

1.3% |

|

Total |

78,233 |

100% |

Source: GAO Analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data. | GAO‑26‑107353

Note: Table 2 includes individuals who entered a residential reentry center and stayed for at least one night from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024. The data were current as of July 27, 2024. Percentages in this table do not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

Table 3: Ethnicity of Individuals in BOP Custody Who Entered a Residential Reentry Center from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024

|

Ethnicity |

Number of Individuals |

Percent of Total |

|

Non-Hispanic |

58,988 |

75.4% |

|

Hispanic |

19,245 |

24.6% |

|

Total |

78,233 |

100% |

Source: GAO Analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data. | GAO‑26‑107353

Note: Table 3 includes individuals who entered a residential reentry center for at least one night from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024. The data were current as of July 27, 2024.

Table 4: Total Number of Days in a Residential Reentry Center (RRC) for all Individuals who entered an RRC, from October 1, 2020, through July 26, 2024

|

|

1-30 |

31-90 |

91-180 days |

181 or more days |

Total |

|

Number of Individuals |

13,582 |

29,191 |

24,937 |

10,523 |

78,233 |

|

Percent of Total |

17.4% |

37.3% |

31.9% |

13.5% |

100% |

Source: GAO Analysis of Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) data. | GAO‑26‑107353

Note: A day in an RRC is defined as staying overnight in an RRC facility. The length of stay for individuals currently in an RRC at the time the data were pulled was calculated using the date the data were extracted. The data were current as of July 27, 2024. Percentages in this table do not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

GAO Contact

Gretta L. Goodwin, GoodwinG@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Jeffrey Fiore (Assistant Director), Andrea Bivens and Steve Komadina (Analysts in Charge), Patricia Broadbent, and Eamon Vahidi made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Tracy Abdo, Lauri Barnes, Christine Catanzaro, Billy Commons, Benjamin Crossley, Margaret Delaney, John Karikari, Mariela Martinez, Priyanka Panjwani, Amanda Panko, and Herrica Telus.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using

American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard,

Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,