FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANKS

Role During Financial Stress and Members' Borrowing Trends and Outcomes

Report to the Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Jill Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLBank) System consists of 11 federally chartered FHLBanks that support liquidity by making loans to member financial institutions (including banks) in the U.S. As of June 2025, 93 percent of banks (approximately 4,100) were members of an FHLBank, allowing them to obtain liquidity via secured loans. GAO’s analysis found that the FHLBanks generally serve as a reliable and consistent source of funding for banks of all sizes throughout the financial cycle. They can also play a key role in the health of small banks (those with $10 billion or less in assets). This has been the case despite concerns raised in some academic and other literature that FHLBank lending could exacerbate periods of financial stress—for example, by masking problems at troubled member banks or increasing resolution costs when a member bank fails.

· Banks’ FHLBank borrowing trends. From 2015 through June 2025, most U.S. banks were FHLBank members and obtained secured loans at least once. Banks’ total outstanding borrowing (as of quarter-end) ranged from $189 billion to $804 billion during this period. Although most active FHLBank members maintained relatively consistent FHLBank borrowing, a small number of large banks (with more than $10 billion in assets) drove substantial increases in aggregate borrowing at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and during the March 2023 liquidity crisis. For example, large banks were responsible for 97 percent of the increased borrowing in the first quarter of 2023. However, median FHLBank borrowing as a share of median total assets generally stayed within a consistent range from 2015 through June 2025, including for large banks. This suggests that their overall reliance on FHLBank loans during stress periods was largely unchanged.

· Outcomes associated with FHLBank borrowing. GAO’s econometric models, which controlled for bank health, macroeconomic factors, and economic cycles, found that higher FHLBank borrowing by a bank was generally associated with positive outcomes for the bank. From 2015 through 2024, higher FHLBank borrowing was associated with (1) increases in real estate lending and (2) lower likelihood of being flagged as a problem bank or of failing or closing voluntarily. These results were largely driven by small banks, which make up 97 percent of banks in GAO’s analysis.

Why GAO Did This Study

The FHLBank System supports liquidity by making billions of dollars in loans to member banks. Federal banking regulators oversee individual banks’ safety and soundness and promote financial stability. The 12 district Federal Reserve Banks also lend to banks and may act as a lender of last resort. Substantial FHLBank lending to three large banks that failed in 2023 renewed questions about FHLBanks’ lending role and communication with banking regulators and Federal Reserve Banks during times of stress.

GAO was asked to review the role of FHLBanks during financial crises. This report examines (1) banks’ FHLBank borrowing trends from 2015 through June 2025; (2) associations between FHLBank borrowing and outcomes; (3) policy considerations for potential changes to FHLBank lending; and (4) communication among FHLBanks and relevant federal agencies during periods of financial stress.

GAO reviewed literature from 2007 through mid-2024; analyzed bank financial reports, FHLBank membership data, and economic indicators; and examined documentation from the FHLBanks, banking regulators, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency. GAO also held seven discussion groups with a total of 30 academics, researchers, and industry group representatives (selected for their relevant knowledge and diverse views) and interviewed representatives of FHLBanks, federal regulators, and a nongeneralizable sample of 10 member banks (selected to reflect varying asset sizes) that borrowed from FHLBanks during recent periods of financial stress.

· Policymaker considerations for potential changes to FHLBank lending. GAO reviewed suggestions for reform from academic, industry, and government sources, such as involving federal banking regulators in lending decisions and changing how FHLBank loans are priced. In discussion groups, interviews, and written comments, stakeholders noted that while these changes could help address certain concerns, each carried potential unintended consequences for markets, member banks (especially smaller ones), and consumers. GAO found that in some cases, the suggested changes would duplicate existing authorities or practices.

The FHLBanks, Federal Housing Finance Agency (which oversees FHLBanks), and the federal banking regulators have mechanisms to communicate during periods of financial stress. The bank failures and related liquidity stress of March 2023 highlighted challenges to timely coordination between the FHLBanks and the Federal Reserve Banks. Since then, they have taken steps to improve their coordination. These include conducting joint tabletop exercises and ongoing discussions to help shared members reallocate collateral during emergencies. In January 2025, the FHLBank System and the Federal Reserve System also established a joint working group to improve routine interoperability between the two systems. These efforts are ongoing and, in some cases, are in early stages, with expected completion in late 2025 or 2026. Continued commitment to these coordination efforts will be important to ensure readiness for future financial stress, when member banks may need to reallocate collateral to access additional liquidity.

Abbreviations

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve Board |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

FHFA |

Federal Housing Finance Agency |

|

FHLBank |

Federal Home Loan Bank |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

UCC |

Uniform Commercial Code |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2025

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

United States House of Representatives

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in March 2023 renewed questions about the Federal Home Loan Banks’ (FHLBank) role as a liquidity provider during periods of financial stress. In the weeks leading up to their failures, these banks had borrowed large sums via secured loans (known as advances) from their district FHLBanks.[1] That same month, the FHLBank System’s total advances outstanding to all members reached about $1 trillion, exceeding previous financial market disruptions. The bank failures required the two district FHLBanks of which the failed banks were members to coordinate with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Federal Reserve Banks, both of which had relevant responsibilities.

Some observers, including academics and former government officials, have suggested changes related to the FHLBanks’ lending role. These suggestions stem from concerns that the system’s structure may lead to lending that threatens financial stability and increases resolution costs when banks fail. In November 2023, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which supervises the FHLBank System, issued a report on its comprehensive review of the system, including the system’s liquidity role, and FHFA has taken some actions in response to the report’s findings.[2]

We were asked to review the role of the FHLBanks during times of financial stress. This report examines (1) active member banks’ FHLBank borrowing trends since 2015, (2) how FHLBank borrowing was associated with member banks’ outcomes from 2015 through 2024, (3) potential changes to FHLBank lending during financial crises and considerations for policymakers when evaluating these changes, and (4) the extent to which FHLBanks, relevant federal regulators, and the Federal Reserve Banks have mechanisms to support effective communication during periods of financial stress.

To address our first objective, we analyzed FHFA’s FHLBank membership data and data from Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council Reports of Condition and Income (known as Call Reports) for banks from the first quarter of 2015 through the second quarter of 2025.[3] We reviewed banks’ FHLBank borrowing, including by outstanding amount and as a share of their total assets. We generally divided banks into two asset-size categories ($10 billion or less in total assets, and greater than $10 billion in total assets) to compare trends. We also analyzed data on key economic indicators and emergency lending to banks by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve) to describe economic and financial conditions that may have affected FHLBank member borrowing during our period. We assessed the reliability of these data through reviews of relevant documentation and electronic data testing. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing banks’ FHLBank membership, borrowing, and assets, as well as describing economic and financial conditions. We also interviewed executives from a nongeneralizable sample of 10 banks to obtain their perspectives on the role of FHLBank borrowing during recent stress periods. The 10 banks each had FHLBank borrowing in the first quarter of 2020, the first quarter of 2023, or both. See appendix I for more information on our methodology.

To address our second objective, we constructed econometric models that considered the extent to which banks’ FHLBank borrowing levels were associated with their lending levels and certain safety and soundness outcomes from 2015 through 2024. The models controlled for bank health characteristics, certain macroeconomic factors, and economic cycles. We analyzed FHLBank membership data, Call Report data, FDIC data on “problem banks” (those with supervisory ratings below a certain threshold), bank failures, and bank liquidations. We also analyzed data on key economic indicators (such as the unemployment rate and gross domestic product). We assessed the reliability of these data through reviews of relevant documentation, interviews with agency officials, and electronic data testing. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing banks’ FHLBank membership, borrowing, health characteristics, lending, and specific safety and soundness outcomes, as well as describing economic and financial conditions. For more information about our econometric modeling, see appendix II.

To address our third objective, we reviewed literature published from January 2007 (prior to the financial crisis of 2007–2009) through May 2024 (the month we conducted the literature search) that addressed FHLBank lending during times of financial stress. We documented authors’ views about such lending and identified the most frequently cited concerns, as well as any suggestions for changes to FHLBank lending during stress periods. We excluded certain types of changes from further examination (such as changes focused directly on the FHLBanks’ housing mission) and consolidated the remaining suggestions as appropriate into broader categories. This process resulted in eight suggested changes for discussion purposes. We obtained input on the eight suggested changes from 30 discussion group participants (academics, researchers, and representatives of industry and consumer groups, selected for their relevant knowledge and experience and reflecting a range of views on FHLBank lending); representatives of the 11 FHLBanks; and FDIC officials.[4] We performed a content analysis of the input we received to identify key themes related to implementation and potential effects of the suggested changes.

To address our fourth objective, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations about information sharing among the FHLBanks, FHFA, and the federal banking regulators. We also reviewed FHLBank and agency documentation and held interviews with representatives of all 11 FHLBanks and officials from FHFA, FDIC, the Federal Reserve System, the Financial Stability Oversight Council, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). We compared our findings about their communication mechanisms against relevant principles in our internal control standards.[5] In addition, we analyzed FHLBank membership data and Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council data on member banks’ Federal Reserve district membership to determine intersections of membership between FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks. We assessed the reliability of the data by verifying our results with the FHLBanks and the Federal Reserve Board. We determined the data were reliable for the purpose of identifying overlapping membership.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The FHLBank System and Advances

The FHLBank System is a government-sponsored enterprise that includes 11 federally chartered FHLBanks—each a cooperative owned by its members—and a joint Office of Finance that issues debt on behalf of the FHLBanks.[6] The FHLBanks support liquidity in the financial system and promote housing and community development.

As of June 2025, 93 percent of banks (4,104 of the 4,424 banks in our population) were FHLBank members.[7] To qualify for membership, banks must meet certain criteria, including that they must (1) be regulated by the appropriate federal or state banking regulator, (2) purchase or originate home mortgage loans with terms of 5 years or more, and (3) hold at least 10 percent of their assets in residential mortgage loans at the time of application.[8] Members must also purchase and maintain stock in their FHLBank, consistent with that FHLBank’s capital structure plan.[9]

FHLBanks primarily provide funding through secured loans known as advances. These advances offer member institutions a low-cost source of funding to make mortgage loans or manage liquidity risk—that is, the risk of not meeting financial obligations in a timely and cost-efficient manner. FHLBanks offer a variety of advance products, including fixed- and variable-rate advances.[10] Maturities range from overnight to 30 years, although the majority of advances are for 3 years or less.

The process for obtaining an FHLBank advance includes an ongoing assessment of members’ creditworthiness and the pledging of eligible collateral.

· Credit assessment. When an institution applies for FHLBank membership, the FHLBank evaluates its creditworthiness and assigns a credit rating contingent on the pledge of collateral. FHLBanks periodically reassess member creditworthiness based on both the pledged collateral and the member’s financial condition.

· Collateral pledging. To obtain advances, members must pledge eligible collateral (such as certain mortgage loans, securities, cash, or U.S. Treasuries), ensuring the FHLBank is fully collateralized. Required collateral levels incorporate the cost to sell or liquidate the pledged collateral and the risk of a decline in market value. As a result, the pledged amount generally exceeds the amount owed. Members commonly grant the FHLBank a lien on all eligible collateral, which allows them to borrow as needed, according to FHLBank officials. FHLBanks also have a lien upon and hold member stock as additional collateral for all advances.

Because FHLBank members are both FHLBank customers and stockholders, members receive dividends on their shares of capital stock, which can reduce their effective funding costs.

As the FHLBanks’ regulator, FHFA is responsible for ensuring that the FHLBanks operate in a financially safe and sound fashion, remain adequately capitalized and able to raise funds in the capital markets, and operate in a manner consistent with their housing finance mission.

Bank Population

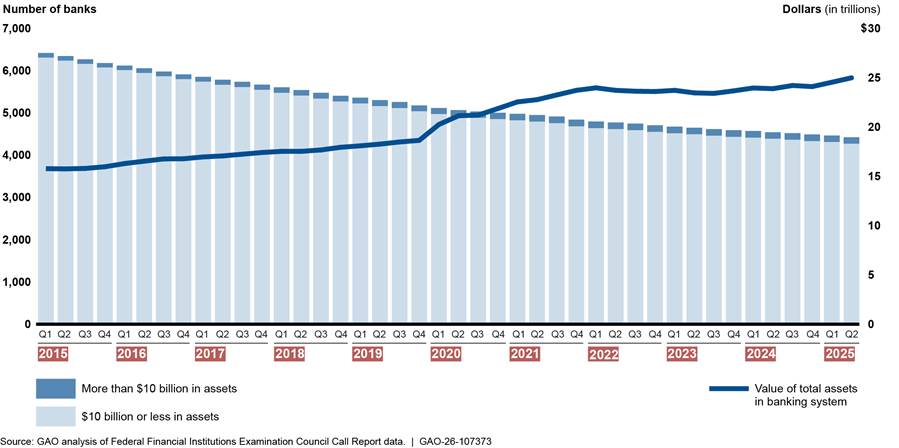

From the first quarter of 2015 through the second quarter of 2025, the number of banks in the United States decreased by 31 percent, from approximately 6,400 to fewer than 4,500 (see fig. 1), continuing a long-term trend.[11] As many small banks (banks with total assets of $10 billion or less) exited the market, the average asset size of remaining banks grew, and total banking system assets expanded significantly. On average, while 97 percent of banks during this period were small, the remaining 3 percent (large banks, with total assets greater than $10 billion) controlled about 84 percent of total system assets.

Figure 1: Number of Banks, by Asset Size, and Total Banking System Assets, First Quarter 2015–Second Quarter 2025

Role of Federal Financial Regulators and Federal Reserve Banks

The federal banking regulators—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FDIC, and OCC—supervise the banks that are members of the FHLBanks and promote safety and soundness.[12] As part of their supervision, the regulators review bank data and documents such as quarterly Call Reports and contingency funding plans, which outline how banks would secure funding during periods of stress. Examination guidance generally directs bank examiners to consider the adequacy of the bank’s funding profile, including its reliance on FHLBank advances, as part of the broader assessment of the bank’s funding profile and its liquidity risk management.

The Federal Reserve Banks also operate the discount window, which offers short-term funding to depository institutions at a rate established by the Federal Reserve Banks, subject to review and determination of the Federal Reserve Board.[13] Although the primary discount window program is specifically intended for healthy borrowers experiencing liquidity needs, discount window use is often stigmatized by the market. Banks therefore sometimes avoid using it for fear that market participants and regulators will view it as a sign of weakness.[14]

The discount window accepts a wide variety of collateral, including much that qualifies for FHLBank advances, though it can apply different haircuts—that is, discounts on the value of collateral.[15] To maximize borrowing capacity, FHLBank members often pledge collateral to the Federal Reserve Banks that is not eligible for securing FHLBank advances (for example, consumer loans). However, in some circumstances—such as urgent or large funding needs—FHLBank members may need to reallocate excess FHLBank collateral (collateral pledged to an FHLBank but not needed for borrowing FHLBank advances) to a Federal Reserve Bank to access the discount window. Similarly, members can reallocate collateral the other way, from the Federal Reserve to an FHLBank, depending on liquidity strategies, collateral haircuts, and other factors. In these cases, coordination among the FHLBank, the Federal Reserve Bank, and the member institution may be necessary.

FDIC, in addition to supervising banks, administers the Deposit Insurance Fund, which insures deposits at FDIC-insured banks and helps cover the cost of resolving failed banks.[16] FDIC may also act as the receiver of closed banks, responsible for liquidating or collecting their assets and settling debts, including any outstanding FHLBank advances.

Recent Periods of Financial Stress

COVID-19 pandemic. In February 2020, the U.S. economy entered a recession in response to the effects of COVID-19.[17] Declaration of the pandemic in March 2020 triggered a sharp contraction of economic activity and a surge in unemployment. The federal government responded with multiple measures, including emergency lending programs for financial institutions and businesses and stimulus payments for individuals.[18]

March 2023 liquidity event. On March 8, 2023, Silvergate Bank, which had experienced a bank run starting in late 2022 due to concerns surrounding its involvement with the digital assets industry, announced its intent to wind down operations and voluntarily liquidate. This action prompted broader market uncertainty, especially at banks with depositors affiliated with the digital assets industry and venture capital. The subsequent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank on March 10 and 12, 2023, respectively, increased the risk of runs, particularly on uninsured deposits, on other large banks. To contain the risk of contagion, federal banking regulators and the Department of the Treasury took emergency measures to protect all depositors of the two failed banks. In addition, the Federal Reserve, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, offered an emergency lending program for eligible banks.[19]

Most Banks Have Maintained Relatively Consistent FHLBank Borrowing Since 2015

Most banks maintained relatively consistent FHLBank borrowing activity from the first quarter of 2015 through the second quarter of 2025. Most banks also maintained consistent reliance on FHLBank advances during this period—keeping their FHLBank borrowing around a consistent percentage of their total assets—including during stress periods. While banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing increased substantially during both the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the March 2023 liquidity stress period, these trends were driven by a small number of large banks, for which increases in borrowing were still a small fraction of their total assets. According to some bank executives, FHLBank advances have certain advantages compared with other liquidity sources, including accessibility, flexibility, cost advantage, and lack of stigma.

A Majority of Banks Have Regularly Borrowed FHLBank Advances Since 2015

From the first quarter of 2015 through the second quarter of 2025, most banks were active FHLBank members that borrowed regularly from their FHLBank, according to our analysis.[20] Of the 6,491 banks that submitted at least one Call Report during this period, more than three-quarters (5,110 banks) were active FHLBank members, borrowing from their FHLBank at least once during the period.[21] Furthermore, most of these active members, 67 percent on average, had outstanding FHLBank borrowing in each quarter.

Executives of banks across a range of asset sizes and regions reported using FHLBank advances regularly, including during periods of stress, to help meet funding needs and manage risk.[22] Executives from eight banks told us they used FHLBank advances to bridge funding gaps and counter deposit outflows related to factors such as taxes, large customer withdrawals, or tourism fluctuations. In addition to funding needs, two banks reported using FHLBank advances to mitigate interest rate risk.[23]

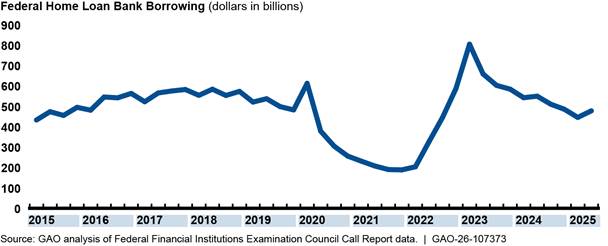

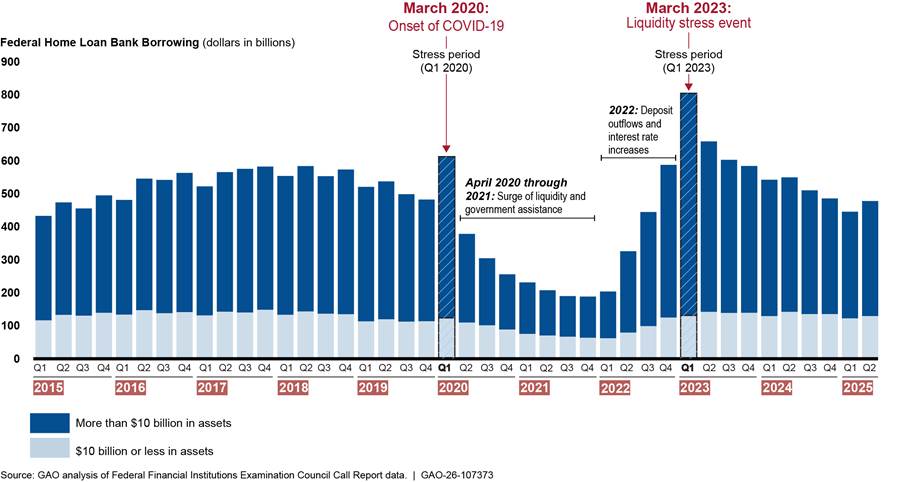

Total outstanding FHLBank borrowing has fluctuated since 2015, reflecting changes in the financial environment and banks’ funding needs (see fig. 2). As discussed below, these fluctuations were driven mainly by a small number of large banks.

Figure 2: Total Outstanding Federal Home Loan Bank Borrowing, by Bank Size, First Quarter 2015–Second Quarter 2025

First quarter 2015–fourth quarter 2019. From the first quarter of 2015 through the last quarter of 2019, the financial environment was relatively stable. Banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing fluctuated modestly between $433 billion and $584 billion, with an average change of 5 percent between quarters. Banks’ domestic deposits (which include funds in checking, savings, and money market accounts held in their domestic offices) and U.S. gross domestic product grew modestly, both by an average of 1 percent each quarter. The effective federal funds rate also did not change by more than half a percentage point from one quarter to the next.[24]

First quarter 2020. The first quarter of 2020 included a recession and the announcement of COVID-19 lockdowns. During this period, banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing grew to $613 billion, a 27 percent increase over the previous quarter.[25] According to our analysis, the greatest advance growth this quarter coincided with the World Health Organization’s declaration of a global pandemic and a steep decline in U.S. stocks. Banks’ outstanding FHLBank borrowing continued to grow every week through the end of March as U.S. gross domestic product decreased and unemployment grew.

Executives we spoke with at seven banks reported increasing FHLBank advances during the first quarter of 2020 due to heightened uncertainty about future economic conditions. One executive said FHLBank advances allowed the bank to fund bank activities and meet risk management needs. For example, bank executives reported using advances to build up surplus cash and liquidity reserves in case the pandemic continued to worsen economic conditions. Executives we spoke with at the remaining three banks either did not borrow from their FHLBank during this period or did not cite specific reasons for doing so.

Second quarter 2020–fourth quarter 2021. Starting in the second quarter of 2020, banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing decreased each quarter by an average of 15 percent, until reaching $189 billion in the last quarter of 2021. During this 21-month period, the financial system continued to experience a liquidity surge due to heightened government intervention through stimulus checks and emergency liquidity lending, as well as low interest rates. For example, the effective federal funds rate dropped to 0.09 percent on April 1, 2020, and remained at 0.1 percent or less through March 16, 2022. Our analysis found that banks generally did not borrow from their FHLBanks and many repaid existing advances during this period. Bank executives attributed this to increased deposits, low interest rates, and support from government programs.

First quarter 2022–fourth quarter 2022. Banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing began increasing again in the first quarter of 2022 as interest rates increased, domestic deposits decreased, and pandemic-related government assistance wound down. After remaining at or below 0.1 percent through the end of the week of March 16, 2022, the effective federal funds rate quadrupled the following week. It continued to increase by half a percentage point or more every 6 to 8 weeks until reaching more than 4 percent by year’s end. FHLBank borrowing also increased every quarter in 2022 by an average of 34 percent over the previous quarter.

First quarter 2023. In the first quarter of 2023, which included the March 2023 bank failures and associated liquidity event, banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing reached $804 billion, the highest level for the period and a 37 percent increase over the previous quarter. Most of this growth occurred immediately following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank on March 10 and 12, according to our analysis. Outstanding FHLBank borrowing by banks with more than $10 billion to $100 billion in assets increased by the greatest amount—approximately three times higher than for smaller and larger banks. By March 31, 2023, banks in this size category were responsible for nearly one-third of outstanding FHLBank borrowing.

We interviewed executives from two banks with more than $10 billion to $100 billion in assets, who both reported increasing FHLBank advances in the first quarter of 2023 due to heightened economic uncertainty or pressure on regional banks to secure funding.[26] For example, one executive reported using FHLBank advances to maintain confidence in the bank’s ability to meet customer needs. An FHFA official also cited increased member test transactions (transactions—typically small—to test a member’s ability to borrow) and regulators’ encouragement to build up liquidity and use the FHLBank System as reasons for increased advance use.

Second quarter 2023–second quarter 2025. Following the March 2023 liquidity stress, banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing decreased by 18 percent to $659 billion in the second quarter of 2023. Starting in March 2023 and continuing through early 2024, the Federal Reserve provided funding to banks through the Bank Term Funding Program, which peaked at more than $167 billion in outstanding loans. Banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing continued to decrease, reaching $478 billion in the second quarter of 2025. While gross domestic product grew by 1 percent, on average, each quarter during this period, the unemployment rate also increased from 3.4 percent in April 2023 to 4.1 percent in June 2025. In the first quarter of 2025, tariff announcements and changes in trade policy created some uncertainty about economic conditions. However, nine of the 10 bank executives we spoke to reported no impact of these events on their banks’ financial condition or FHLBank borrowing activity.

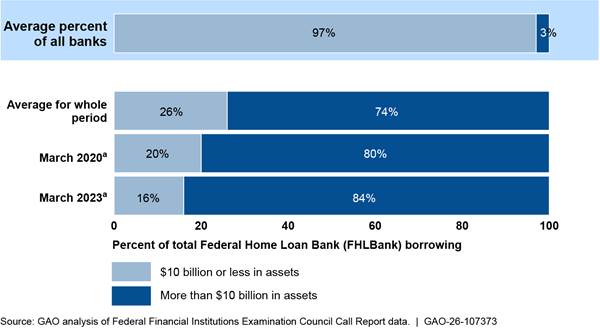

Large Banks Were Responsible for Most FHLBank Borrowing Since 2015

Our analysis of banks’ quarterly Call Report data found that large banks—those with more than $10 billion in total assets—were responsible for a majority of banks’ FHLBank borrowing since 2015, especially during periods of stress. In the second quarter of 2025, fewer than 160 out of the 4,424 banks in our population had more than $10 billion in total assets. Despite representing approximately 3 percent of active FHLBank members, large banks held, on average, nearly 74 percent of all outstanding FHLBank borrowing (see fig. 3).

The concentration of borrowing by large banks was even more pronounced during stress periods. In the first quarter of 2020, at the onset of COVID-19, banks with more than $10 billion in assets held 80 percent of total outstanding FHLBank borrowing—6 percentage points higher than average. During the first quarter of 2023, their share rose to 84 percent, 10 percentage points higher than average.

Figure 3: Banks’ Share of Total Outstanding FHLBank Borrowing, by Bank Size, First Quarter 2015–Second Quarter 2025

aStress period.

Banks with more than $10 billion in assets were also responsible for more than 90 percent of increases in total outstanding FHLBank borrowing during both stress periods. In the first quarter of 2020, banks’ total outstanding FHLBank borrowing increased by $130 billion over the previous quarter, with 92 percent of that increase ($120 billion) attributable to large banks. Similarly, in the first quarter of 2023, total outstanding borrowing grew by $217 billion, of which 97 percent ($211 billion) was attributable to large banks.

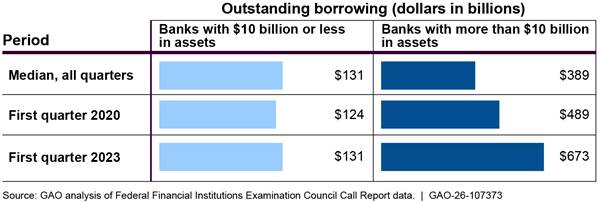

While small banks increased their borrowing during the onset of COVID-19 and March 2023—by about $11 billion and $6 billion, respectively, compared with the previous quarter—their total outstanding FHLBank borrowing during these periods was the same or lower than the median level for the whole period (see fig. 4). By contrast, total outstanding borrowing by banks with more than $10 billion in total assets was above the median level during both stress periods.

Figure 4: Total Outstanding Federal Home Loan Bank Borrowing, by Bank Size, First Quarter 2015–Second Quarter 2025

Banks’ Ratio of FHLBank Borrowing to Total Assets Generally Has Stayed Within a Consistent Range Since 2015

The ratio of a bank’s FHLBank borrowing to its total assets is an indicator of the extent to which the bank relies on FHLBank borrowing, compared with other funding sources, to support operations or manage risk—a higher percentage reflects greater reliance. Since 2015, most active FHLBank members (76 percent) had a ratio of FHLBank borrowing that was 5 percent or less of total assets. Additionally, during this period, most active FHLBank borrowers (62 percent, on average) did not change their ratio compared with the previous quarter. Of the remaining 38 percent that did change their ratio between quarters, most (69 percent) changed it by 2 percentage points or less. This indicates that banks typically do not change their reliance on FHLBank borrowing significantly from one quarter to the next. See sidebar for information on six banks with more than $10 billion to $100 billion in assets that did increase their reliance on FHLBank advances leading up to, and during, the March 2023 liquidity stress.

|

Banks with Increased Reliance on FHLBank Advances Around March 2023 While most banks maintained consistent Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLBank) borrowing activity during recent stress periods, we identified six banks with more than $10 billion to $100 billion in assets that increased their ratio of borrowing to total assets by more than 10 percentage points in 2022 or the first quarter of 2023. Among these six banks was Silvergate Bank, which increased its ratio by 33 percentage points in the last quarter of 2022 and voluntarily liquidated on March 8, 2023. In contrast, the remaining five banks that increased reliance during this period subsequently decreased their outstanding FHLBank borrowing in the second quarter of 2023. We interviewed an executive at one of the six banks, who told us the bank increased reliance on FHLBank advances in March 2023 due to a negative perception of regional banks and increased uncertainty. The executive said FHLBank advances were a secure way to source cash quickly to be able to meet potential challenges. Source: GAO analysis of Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council call report data and an interview. | GAO‑26‑107373 |

Our analysis of Call Report data from the first quarter of 2015 through the second quarter of 2025 found that banks generally maintained a consistent ratio of FHLBank borrowing to total assets to fund their activities, including during periods of stress. Specifically, when examining all quarters except recent stress periods, we found that, at the median, FHLBank borrowing generally made up 0 to 5 percent of total assets, depending on asset size (see table 1). During stress periods—the first quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2023—the median ratio of FHLBank borrowing to total assets remained within the banks’ consistent range.

Table 1: Median Ratio of FHLBank Borrowing to Total Assets, by Bank Size, First Quarter 2015–Second Quarter 2025

Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLBank) borrowing as a percentage of total assets

|

|

Bank asset size |

||||

|

Period |

$1 billion or less |

More than $1 billion to |

More than $10 billion to |

More than $100 billion to |

More than |

|

First quarter 2020 |

1% |

3% |

4% |

3% |

2% |

|

First quarter 2023 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

|

All other quartersa |

0–2 |

0–4 |

0–5 |

0–4 |

0–3 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council Call Report data. | GAO‑26‑107373

aThe “all other quarters” category represents the range of median ratios across all quarters from first quarter 2015 through second quarter 2025, excluding the two stress periods (first quarter 2020 and first quarter 2023).

In addition, we found that many banks had no change in their ratio of FHLBank borrowing during either stress period. Specifically, 61 percent of active FHLBank members maintained their FHLBank borrowing ratio in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the prior quarter, and 48 percent did so in the first quarter of 2023. While more banks changed their FHLBank borrowing ratio in the first quarter of 2023, among those that did, about half increased their ratio and about half decreased it.

We also found that banks that typically rely more heavily on FHLBank borrowing did not increase their reliance on advances during stress periods compared with the rest of the period. While some banks held more than 5 percent of their assets in FHLBank borrowing, their borrowing ratios also stayed within a consistent range during periods of stress.[27]

Banks’ ratios of FHLBank borrowing to total assets remained relatively consistent despite aggregate increases in total FHLBank borrowing. This is because banks also increased their use of other funding sources, including repurchase agreements, federal funds, other borrowing, time deposits, and brokered deposits.[28] Our review found that during recent stress periods, other funding sources increased by a magnitude similar to that of FHLBank borrowing.

Selected Banks Reported That FHLBank Advances Have Advantages over Other Funding Sources

Banks primarily fund their operations through customer deposits, like checking and savings accounts, but may also use other funding sources, including FHLBank advances. According to bank executives we interviewed, when deposits are low, these alternative sources help banks meet funding demands, diversify funding structures, and maintain an appropriate ratio of assets to liabilities.

While banks often use a mix of funding sources, executives from the 10 banks we spoke with told us that FHLBank advances have some advantages over other types of funding, including the following:

· Speed and availability. Executives of nine banks told us they preferred FHLBank advances because of how quickly and easily they can secure funds. Banks can submit a request—specifying the amount, term, and type of advance—through their FHLBank’s website and obtain funds within the same business day. Other funding sources, like brokered time deposits and the discount window, require advance planning and are not immediately available. The executives emphasized the importance of securing funding quickly to manage changes in funding or risk during periods of financial stress.

· Flexible maturity options. Executives of six banks highlighted the broad range of terms available with FHLBank advances, with maturities ranging from overnight to 30 years. In contrast, the discount window offers terms of overnight to 90 days. One bank executive told us their bank was able to restructure some advances to longer maturities when interest rates fell, securing long-term funding at a fixed rate.

· Cost advantages. Executives of seven banks reported that FHLBank advances are competitively priced and come with financial incentives. Two executives noted that FHLBank rates are less affected by market swings than other sources, making them useful in periods of stress. Executives from two banks cited dividends on FHLBank stock as an incentive, sometimes making advances attractive even when their rates exceed those of other funding options. Banks may also use FHLBank advances more frequently to earn higher dividends.

· Lack of stigma. Executives of seven banks told us that in an emergency, they would prefer FHLBank funding because it does not carry the same perceived stigma as borrowing from the discount window. Because most banks use FHLBank advances in normal operations, FHLBank borrowing during periods of stress is not considered a sign of trouble.

While bank executives reported that FHLBank advances have certain advantages, three executives noted the importance of maintaining a diversified mix of funding sources. They highlighted time deposits, brokered deposits, repurchase agreements, and federal funds as other funding sources they may use.

The executives also provided reasons why they may use other funding sources instead of FHLBank advances. Two noted that FHLBanks require loan collateral up front, whereas time deposits and brokered deposits do not, potentially making them easier to access. One executive explained for advances under $1 billion, brokered time deposits are less expensive than FHLBank advances.

For Most Banks, Higher FHLBank Borrowing Was Associated with Positive Outcomes from 2015 Through 2024

Our analysis found that higher FHLBank borrowing was generally associated with positive outcomes for most banks, especially smaller banks with $10 billion or less in assets. For these banks, higher borrowing was associated with more lending and not associated with increased likelihood of certain safety and soundness concerns. In contrast, for large banks with more than $10 billion in assets, we found no evidence of a relationship between FHLBank borrowing and lending, and the relationship between borrowing and risk to safety and soundness is unclear.

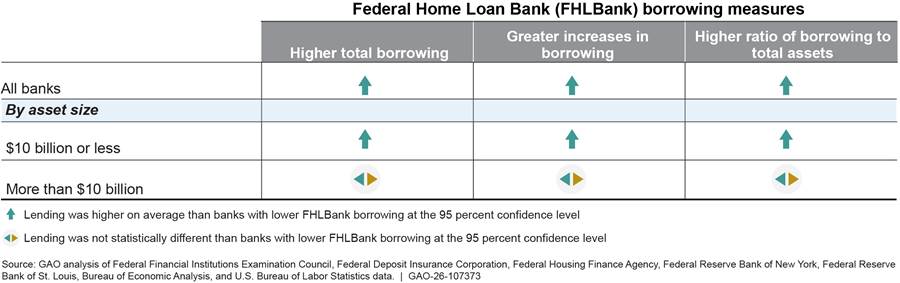

Small Banks with Higher FHLBank Borrowing Lent More on Average Than Those with Lower FHLBank Borrowing

Overall, our econometric models found that banks with higher FHLBank borrowing lent more on average than banks with lower FHLBank borrowing from 2015 through 2024 (see fig. 5).[29] This finding was consistent across all three measures of FHLBank borrowing we analyzed: (1) total FHLBank borrowing each quarter, (2) increase in FHLBank borrowing quarter to quarter, and (3) ratio of FHLBank borrowing to total assets. For example, a 1 percent increase in total FHLBank borrowing each quarter was associated with a 0.009 percent increase in overall lending.[30] The results were driven by banks with $10 billion or less in assets.[31] For large banks (more than $10 billion in assets), we found no evidence of a relationship between FHLBank borrowing and lending.

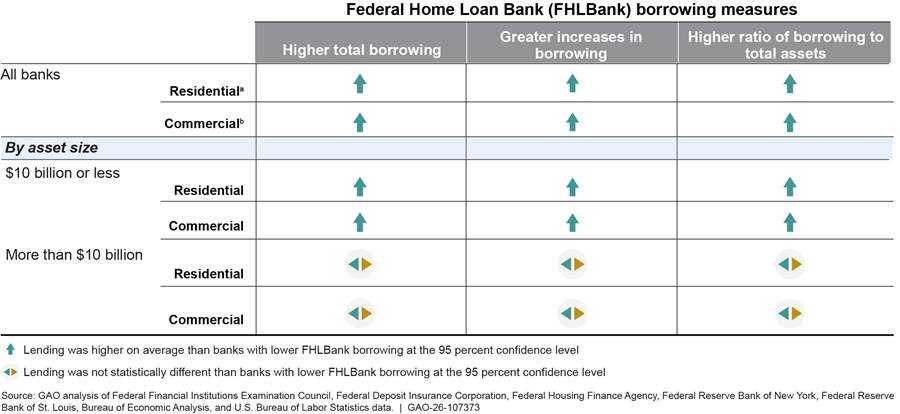

Similarly, banks with higher FHLBank borrowing made more real estate loans on average, according to our analysis (see fig. 6). Specifically, banks with higher FHLBank borrowing across all three measures provided more residential and commercial real estate loans on average than banks with lower FHLBank borrowing.[32] For example, a 1 percent increase in total FHLBank borrowing each quarter was associated with a 0.011 percent increase in residential real estate lending and a 0.01 percent increase in commercial real estate lending. These overall results were driven by banks with assets of $10 billion or less.[33] For banks with more than $10 billion in assets, we generally found no evidence of a relationship between FHLBank borrowing and real estate lending.

aResidential loans are for 1–4 family and multifamily (5 or more) residential properties, including loans for construction of 1–4 family residential properties.

bCommercial loans are for farmland and other nonresidential, nonfarm properties, including loans for construction and land development (excluding 1–4 family residential construction loans).

In contrast, for consumer lending, we found that small banks with greater increases in FHLBank borrowing quarter to quarter made more consumer loans on average than banks with smaller increases (see fig. 7).[34] For these banks, a 1 percent increase in FHLBank borrowing quarter to quarter was associated with a 0.002 percent increase in consumer lending. For banks overall and those with more than $10 billion in assets, we generally found no evidence of a relationship between FHLBank borrowing and consumer lending.

Note: Our analysis of consumer lending included loans for credit cards, automobile loans, and student loans, among other things.

Our findings suggest that FHLBank borrowing may support more loans for housing and community development activities by banks with $10 billion or less in assets. These smaller banks made up 97 percent of the banks in our analysis. However, we did not find the same pattern for banks with more than $10 billion in assets, which were responsible for 74 percent of all FHLBank borrowing on average from 2015 through 2024.

The FHLBanks’ mission is to provide liquidity to their members to support housing finance and community development through all economic cycles. However, because this funding is fungible, it is unclear to what extent FHLBank members are using advances to make loans for housing and community development activities, as opposed to funding other financial assets (e.g., certificates of deposit, federal funds sold, securities).[35]

These findings are generally consistent with research on the relationship between FHLBank borrowing and lending across other periods.[36] For example, one study found that quarter-to-quarter growth in FHLBank borrowing was positively related to growth in total loans, residential real estate loans, commercial real estate loans, and consumer loans from 2000 to 2016.[37]

Small Banks with Higher FHLBank Borrowing Were Generally Less Likely to Have Serious Safety and Soundness Issues

Problem Bank List

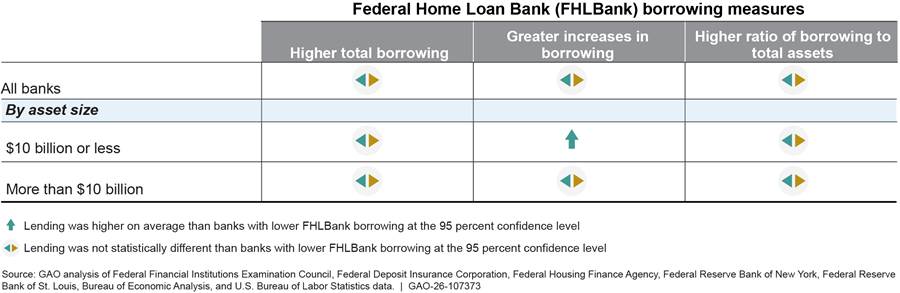

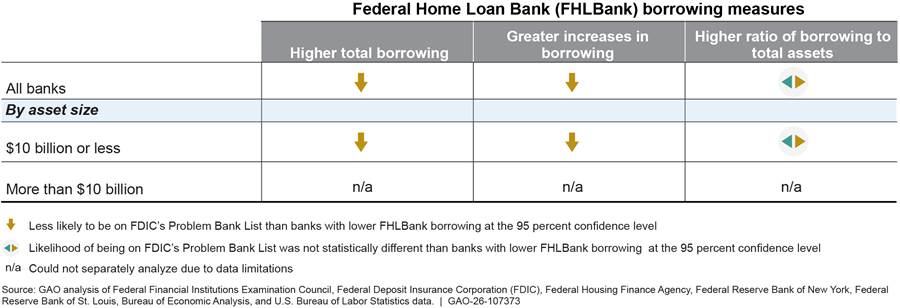

Our analysis found that from 2015 through the third quarter of 2024, banks with higher total FHLBank borrowing or greater increases in borrowing were less likely to appear on FDIC’s Problem Bank List (see fig. 8). Banks are added to the Problem Bank List when their supervisory rating falls below a certain threshold.[38]

Figure 8: Banks’ Likelihood of Appearing on FDIC’s Problem Bank List by FHLBank Borrowing Measure, 2015–Third Quarter 2024

For banks with $10 billion or less in assets, similar to our findings for all banks, we found that those with higher total FHLBank borrowing or larger increases in borrowing were less likely to appear on the Problem Bank List. However, there was no evidence of a relationship between a bank’s ratio of FHLBank borrowing to total assets and its likelihood of being on the list, according to our analysis. We were unable to separately analyze banks with more than $10 billion in assets due to data limitations, such as the low number of such banks of this size appearing on the Problem Bank List from 2015 through the third quarter of 2024.[39]

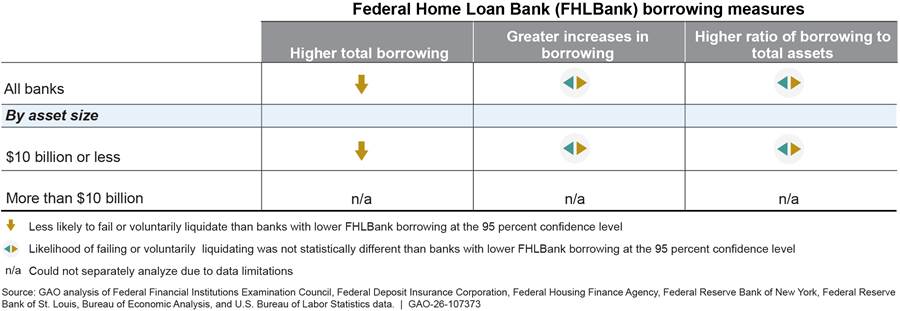

Failure or Liquidation

Overall, our analysis found a statistically significant difference in the likelihood of bank failure or liquidation for one borrowing measure (see fig. 9).[40] Banks with higher total FHLBank borrowing each quarter were less likely to fail or liquidate than banks with lower FHLBank borrowing during the period from 2015 through the third quarter of 2024.

Figure 9: Banks’ Likelihood of Failure or Liquidation by FHLBank Borrowing Measure, 2015–Third Quarter 2024

For banks with $10 billion or less in assets, similar to our findings for all banks, we found that banks with higher total FHLBank borrowing each quarter were less likely to fail or liquidate than those with lower FHLBank borrowing. We were unable to separately analyze banks with more than $10 billion in assets due to data limitations, such as the low number of such banks that failed or liquidated from 2015 through the third quarter of 2024.[41]

Taken together, our findings on the relationship between FHLBank borrowing and the likelihood of being on the Problem Bank List and failing or liquidating suggest that higher FHLBank borrowing is generally not associated with increased likelihood of serious safety and soundness issues in banks with $10 billion or less in assets. One study we reviewed raised concerns that the structure of FHLBank advances (i.e., lack of risk-based pricing) incentivizes banks to take certain types of risks.[42] However, this study and others also suggest that FHLBank borrowing may help banks manage certain types of risk.[43] Officials from FDIC, the Federal Reserve Board, and OCC stated that, generally, they do not see an increase in FHLBank borrowing on its own as an indicator of a safety and soundness concern. FHLBank borrowing is just a portion of banks’ overall funding strategy, according to officials. However, officials said that material increases in FHLBank borrowing or other deviations from a bank’s normal borrowing patterns may indicate a problem.

In our analysis, we found no evidence that higher FHLBank borrowing was associated with an increased likelihood of being on the Problem Bank List, failing, or liquidating. Moreover, in some cases, we found that higher FHLBank borrowing was associated with a reduced likelihood of those outcomes, particularly for smaller banks. For banks with more than $10 billion in assets, we were not able to analyze the relationship between FHLBank borrowing and likelihood of safety and soundness issues due to data limitations.

See appendix II for more information about the estimates of each econometric model.

Potential Changes to FHLBank Lending Raise Key Trade-Offs for Policymakers

Academics, market participants, and observers have noted concerns about FHLBanks’ lending to troubled banks or lending during times of financial stress and have suggested changes to address these concerns.[44] Our discussion group participants identified both potential benefits and drawbacks of the suggested changes. Additional considerations—including the findings in this report—may help inform policymakers to the extent that potential reforms to the FHLBank System are considered.

Commonly Cited Concerns About FHLBank Lending Relate to Perceived Structural Incentives for Risk-Taking

Literature we reviewed cited concerns that the structure of the FHLBank System’s lending could threaten financial stability—such as by promoting potentially risky lending—and increase resolution costs when banks fail.[45] Commonly cited concerns generally relate to the following perceived features of FHLBank lending that observers believe could encourage risk-taking by member banks and FHLBanks:

· Implied guarantee. According to our literature review, because FHLBanks are government-sponsored enterprises, their debt may be perceived to carry an implied guarantee—that is, a perception that the federal government would provide support in the event of a default by the FHLBanks. In turn, it is perceived that the FHLBanks can borrow and lend more cheaply, leading to concerns that they may be promoting greater risk-taking by members.[46]

· Low pricing. FHLBanks generally offer lower pricing than other liquidity sources and have the authority to pay dividends to members. Some literature cited this as a potential incentive for troubled banks to borrow more or for longer periods than they otherwise would, leading to potential financial stability risks. Specifically, low FHLBank pricing can allow banks to delay balance sheet recognition of losses or actions to maintain healthy liquidity reserves, according to some literature.[47] A related argument was that consistently low FHLBank pricing relative to the discount window could make it less likely that banks would turn to the Federal Reserve as their lender of last resort during times of stress—the concern being that the FHLBanks are not functionally equipped to serve as the lender of last resort.[48]

· Cooperative structure. Although the FHLBanks’ cooperative structure is often cited as a protective feature against excessive risk-taking, some literature noted that FHLBanks’ lending to their member-owners presents a conflict of interest.[49] Specifically, FHLBanks might be more willing to lend to risky members—especially large, influential members—because the expected benefit of higher profits (and subsequent higher dividends for members) outweighs the risk of bank default or failure.

· Lien status and prepayment fees in a bank failure. The FHLBanks’ perceived lack of accountability—or “skin in the game”—for potential losses is another area of concern commonly cited in the literature. Specifically, some literature cited the FHLBanks’ “super lien” advantage—their statutory repayment priority over certain claimants, including any receiver or conservator, such as FDIC—as a potential incentive for imprudent lending. This repayment priority can reduce the FHLBanks’ losses when a member bank fails or otherwise cannot repay its advances, according to some literature we reviewed.[50]

In addition, FHFA has noted that FHLBank prepayment fees help protect the FHLBank System’s financial condition but may also increase the cost of failure.[51] If a member bank fails and has outstanding advances involving prepayment fees, any outstanding prepayment fees owed must still be repaid to an FHLBank on top of the outstanding balance on the advances, potentially increasing resolution costs.

· Collateral-based lending. The FHLBanks’ use of overcollateralized lending—and their resulting ability to avoid losses in the event of default—was cited in the literature as making them less likely to account for members’ credit risk. This could lead to riskier lending and threaten financial stability, potentially increasing resolution costs to the Deposit Insurance Fund, according to literature we reviewed.[52]

· Transparency. A less frequently cited concern in the literature was that FHLBank lending is less transparent than the discount window.[53] Different disclosure requirements pertaining to information on FHLBank borrowing and terms (such as interest rates or collateral types and amounts) could encourage troubled banks to continue borrowing rather than seeking funding sources that provide more insight into their condition, according to literature we reviewed. This could limit transparency for markets and regulators—and reduce FHLBank accountability for lending decisions.[54]

In our review, we also identified literature that cited benefits of FHLBank lending during crises.[55] We did not examine these views in detail because our objective was to examine concerns about and suggested changes to such lending. While we present these concerns above to establish the context for authors’ suggested changes, we provide more information about the current relevant laws, regulations, and practices in the next section.

Certain Changes to FHLBank Lending Suggested in Literature Have Trade-Offs, and Some Duplicate Existing Authorities

We analyzed eight suggested changes to FHLBank lending cited in academic and government literature that seek to address concerns about incentives for risk-taking.[56] We grouped these suggestions into four broad areas: (1) increasing the federal banking regulators’ role in lending decisions, (2) increasing FHLBanks’ accountability for lending, (3) limiting FHLBank lending during a crisis, and (4) altering the pricing structure of advances. Our analysis found that each suggestion could have both positive and negative effects, and that in some cases, existing laws or regulations already allow for the intended action or make the change less relevant.

Increasing Federal Banking Regulators’ Role in Lending Decisions

Three suggested changes from the literature seek to increase the banking regulators’ role in FHLBank lending under certain circumstances:

1. Approving advances to member banks under certain conditions

2. Restricting access to FHLBank advances when a bank’s condition deteriorates

3. Imposing costs (such as a capital charge) on banks that rely heavily on FHLBank advances[57]

With respect to the first two suggested changes, FHFA regulations currently allow for certain banking regulator interventions in FHLBank credit decisions. For example, an FHLBank may not make an advance to a member without positive tangible capital unless the member’s primary regulator or insurer requests it. A member bank’s regulator can also prohibit FHLBank advances to a capital-deficient member with positive tangible capital by notifying the FHLBank in writing that a member’s use of FHLBank advances has been prohibited.[58] However, banking regulator officials informed us they generally have not intervened in FHLBank lending decisions.

In addition, FHLBank representatives said FHLBanks review members’ creditworthiness at least quarterly—more frequently for members in troubled condition—and reduce a member’s borrowing capacity or require more collateral when necessary. They stated that certain FHLBanks generally coordinate these actions with the member’s primary regulator.

Further, with respect to the third suggested change, FDIC officials noted that, in general, large banks with a heavy reliance on FHLBank advances pay more for deposit insurance. Specifically, for banks with more than $10 billion in total assets, FDIC uses a scorecard methodology that considers the amount of advances—along with other secured liabilities—in calculating banks’ deposit insurance assessment rates.[59]

Several discussion group participants, FHLBank representatives, and FDIC officials noted some potential negative effects of these suggested changes:[60]

· Liquidity delays. Regulatory approval could delay access to funding and increase the risk to member banks. A few participants noted that these suggestions could particularly affect small banks without access to alternative funding sources, like repurchase agreements.[61]

· Business model disruption. Several participants said members might need to adjust their business models to accommodate delays, which might have serious negative effects during periods of financial stress.

· Less lending capacity. A few participants said restricting liquidity could have other unintended consequences, such as constricting lending.

· Conflicts of interest. Giving the regulators greater authority in FHLBank lending decisions could blur the lines between supervisory and lending roles. FDIC officials noted that banking regulators do not have legal authority or responsibility to make credit decisions for FHLBanks and that such authority could introduce conflicts between FDIC’s interests as insurer and potential receiver.[62]

· Resource concerns. Some discussion group participants and FDIC officials questioned whether regulators have the time, staff, or necessary skills to review a large volume of advance requests in real time.

Discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives also noted potential positive effects of increasing the regulators’ role:

· Improved communication. Regulatory involvement could help surface concerns about a bank’s condition earlier, according to a few participants and FHLBank representatives.

· Greater use of the discount window. A few participants said requiring regulators’ approval or otherwise making advances more difficult to obtain could also prompt more banks under stress to use the discount window, which they believed was the intended lender of last resort.

Increasing FHLBanks’ Accountability for Lending

Two suggested changes were intended to increase FHLBanks’ accountability for lending:

1. Change how FHLBanks are paid following the failure of a member bank with outstanding advances, such as by

a. moving FHLBanks lower in the order of actors repaid by the receiver following a bank failure (i.e., eliminating the FHLBanks’ “super lien” advantage), or

b. requiring the FHLBank to pay a penalty or forfeit prepayment fees associated with the failed banks’ advances.[63]

2. Change FHLBanks’ required disclosure of FHLBank borrowing, such as by requiring FHLBanks to immediately and publicly disclose advances beyond a certain size threshold.[64]

Changing How FHLBanks Are Paid in a Bank Failure Situation

One suggestion to increase accountability for lending is to move FHLBanks lower in the repayment order after a member bank fails, effectively eliminating their perceived “super lien” advantage. However, the advantages of the “super lien” have diminished over time. While this lien once gave the FHLBanks a substantial advantage over other creditors in a receivership situation, changes to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) around 2001 reduced its significance.[65] Before that time, the only way to “perfect” a security interest in collateral (i.e., give a creditor priority interest in the collateral over other creditors) under the UCC, as relevant here, was through possession of collateral promissory notes. But the “super lien” gave FHLBanks priority over an unperfected security interest. That is, the FHLBank was deemed to have priority over another creditor if the creditor did not possess the collateral. The FHLBank did not have to possess the notes to obtain that priority.

Since the UCC changes took effect, however, any creditor, including an FHLBank, can use an alternative mechanism—filing a financing statement—to perfect their security interest in the property securing the advance. Thus, according to FHFA, because all FHLBanks file financing statements to ensure a first priority position, the perceived “super lien” mainly applies to rare situations where no secured creditor, including the FHLBank, has perfected or possessed the collateral before a receivership.

Another suggestion to increase lending accountability is to require FHLBanks to forfeit prepayment fees. This would require changes to FHFA’s advance regulations, FDIC’s receivership regulations, and, according to FHLBank representatives, their advance agreements.[66] FHLBank representatives told us that eliminating these fees would shift both credit and market risk from member institutions to the FHLBanks, as members would be able to restructure or prepay outstanding advances without bearing any associated financial costs. They explained that this risk transfer could undermine the cooperative structure of the FHLBank System and potentially increase borrowing costs for other members, as the FHLBanks would need to absorb and price for the additional risk across their broader membership base.

Some discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives noted potential negative effects of changing how FHLBanks are paid following a bank failure. They said lending practices inconsistent with market norms could lead FHLBanks to mitigate risk by requiring more collateral or reducing longer-term and fixed-rate advances. FHLBank representatives told us this change could particularly affect small banks with limited funding alternatives. These banks might be forced to use other, less reliable funding sources.

A few discussion group participants and FDIC officials also identified potential positive effects. For example, reducing prepayment fees could lower costs to the Deposit Insurance Fund when a failed bank holds FHLBank advances.[67]

Disclosures

Although the suggestion for FHLBanks to require immediate disclosure of advances above a certain threshold is intended to improve transparency and accountability, various reporting requirements already make some advance information public. For example, all FHLBanks and publicly traded member banks must file periodic reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission.[68] Additionally, the FHLBank System’s Office of Finance issues an annual combined financial report that reports the top five advance holders for each FHLBank. Banks also must disclose their total outstanding FHLBank advances in quarterly Call Reports.

Several discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives said implementing a real-time disclosure requirement would raise complex questions. These include how soon disclosure should occur and how to define the reporting threshold. FHLBank representatives noted that FHFA and the banking regulators would have to conduct rulemakings to establish such a requirement.

As with other proposed changes, some discussion group participants, FDIC officials, and FHLBank representatives noted potential positive and negative effects. A few discussion group participants said a disclosure requirement could increase knowledge of a bank’s condition, and one said it could lead to earlier market corrections for troubled banks. However, some participants, FHLBank representatives, and FDIC officials warned that without adequate context, such disclosure could exacerbate stress and increase the risk of bank runs. They further noted that disclosure could stigmatize FHLBank advances and discourage their use, particularly for banks already experiencing stress. This could lead some members to seek alternative funding to avoid reaching the FHLBank disclosure threshold. FHLBank representatives noted that other wholesale funding sources, such as brokered deposits and repurchase agreements, do not carry similar disclosure requirements.

Limiting FHLBank Lending During a Crisis

One suggested change would replace FHLBank lending during crises with Federal Reserve lending.[69] This change could help address concerns about members’ reliance on the FHLBanks and subsequent financial stability risks and higher resolution costs during times of stress.

The Federal Reserve’s discount window is available to eligible banks throughout the financial cycle. In addition, in certain circumstances and subject to other statutory requirements, the Federal Reserve Board has authority to authorize emergency lending programs, as it has done in recent crises.[70]

Stakeholders we interviewed generally cited more drawbacks than benefits to this suggested change. Some discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives questioned how policymakers would define the start and end of a crisis, and some participants questioned whether the Federal Reserve had the time or necessary skills to implement it effectively. Some participants doubted the Federal Reserve’s capacity to fully replace FHLBank lending during a crisis.

However, a few discussion group participants said such a change could promote market clarity by stating that the Federal Reserve would serve as the lender of last resort in a crisis.[71]

Altering the Pricing Structure of Advances

Two suggested changes would modify how FHLBanks price advances:

1. Require FHLBanks to set advance rates (net of dividends) higher than the discount window’s primary credit program rate.

2. Price advances based on individual members’ credit risk.[72]

These changes aim to reduce member reliance on FHLBank funding and encourage use of other, potentially more transparent, funding sources, including the discount window.

Raising FHLBank Advance Rates

FHLBank representatives said that requiring net advance rates above the Federal Reserve’s discount window rate would require FHFA rulemaking or a policy determination justifying higher pricing. Currently, FHFA’s advance regulations restrict FHLBanks from pricing advances below (1) the market rate for similar products with matching terms and maturity, and (2) the administrative and operating costs associated with making the advance.[73] Thus, FHFA would need to conduct a rulemaking to amend its regulations to require that the minimum pricing on advances exceed the rate charged by the Federal Reserve’s discount window.

A few discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives noted potential downsides to this change. They said it would disrupt FHLBanks’ role as routine liquidity providers, potentially reduce the volume of FHLBank advances, or lead to less business and consumer lending by small member banks. It could also increase borrowing costs and reduce funding for FHLBanks’ housing mission, according to FHLBank representatives.[74] A few participants noted that changing pricing alone might not deter member banks’ use of advances because advances offer desirable features, such as a range of maturities and ease of access.

FHLBank representatives and FDIC officials also cautioned that artificially raising net advance rates higher than the discount window could create market distortions. FHLBank representatives said FHLBank advance pricing is market-driven, reflecting private investor demand for FHLBank debt, unlike discount window rates. They also said that benchmarking advance rates to a nonmarket, government-administered rate introduces the appearance of price controls and would undermine the FHLBanks’ ability to compete with market-based alternatives.

Pricing Based on Individual Member Credit Risk

A few discussion group participants and FHLBank representatives noted that FHFA regulations permit FHLBanks to use differential pricing based on a member bank’s individual credit risk or other reasonable criteria as long as it can be applied to all members equally.[75] A few participants and FHLBank representatives noted that FHLBanks account for credit risk in other ways as well, such as requiring physical delivery of collateral, increasing haircuts, or reducing the advances. Additionally, FHFA issued a 2024 advisory bulletin that emphasized the importance of carefully considering members’ credit risk during lending decisions.[76]

A few discussion group participants also noted potential implementation challenges, including the need for additional resources or expertise at FHFA or FHLBanks. Two other participants said that pricing based on members’ credit risk could disadvantage small banks, which may appear riskier due to their asset size. In addition, two participants cautioned it could drive member banks to leave the FHLBank System if it no longer offered advantageous pricing.

Other Considerations Could Help Inform Policy Deliberations on FHLBank Lending

A key consideration for policymakers in weighing changes to FHLBank lending is the FHLBank System’s interconnectedness with other parts of the financial system. According to discussion group participants, FHLBank representatives, and FDIC officials, many of the suggested changes could restrict, increase the cost of, or otherwise limit member banks’ access to routine liquidity. This could particularly affect small banks with fewer funding alternatives. While some changes could push member banks to use the discount window, they also could discourage healthy banks from using FHLBanks under normal conditions. As our analysis shows, many banks rely on the FHLBanks as a funding source, with at least half of all banks having had outstanding FHLBank borrowing over the past decade. In addition, changes to the FHLBanks’ liquidity role could affect investment by the system and its members in housing and community development.[77]

Although some suggested changes aim to address risks tied to large or increasing volumes of FHLBank borrowing, these risks may be overstated. Our trend analysis found that a small number of large banks drove increases in borrowing during recent crises, and their borrowing largely remained within a normal range relative to their total assets.

Similarly, much of the literature we reviewed is focused on the risks of lending to severely troubled banks. However, our econometric analysis, which controlled for bank health characteristics, found that greater FHLBank borrowing was generally associated with more lending and fewer safety and soundness issues, particularly among small banks. These findings suggest that, given the potential for certain suggested changes to have unintended effects for small banks and customers, careful consideration of existing outcome data would be warranted when contemplating changes to FHLBank lending. The takeaway for large banks is less clear. Since we were unable to separately analyze the effects of greater FHLBank borrowing on safety and soundness outcomes (including failure) for large banks, we were unable to determine whether the suggested changes would have notable effects on resolution costs. The banks that failed in 2023 had large FHLBank borrowing and costly resolutions. As we have recently reported and as reviews by FDIC and the Federal Reserve have found, multiple factors played into the banks’ failures.[78] Given the importance of FDIC, Federal Reserve System, and OCC involvement in troubled bank situations, these agencies’ existing practices, authorities, and capacity—as described above—are relevant factors to consider with regard to any potential changes to FHLBank lending.

FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks Have Ongoing Efforts to Improve Coordination

FHLBanks, FHFA, and Banking Regulators Meet Regularly to Discuss Policy and Other Issues

FHLBanks and FHFA meet regularly with federal banking regulators, according to FHLBank representatives and agency officials. All FHLBanks reported meeting at least annually with FDIC, OCC, and Federal Reserve Banks. Additionally, FHFA officials said they hold quarterly meetings with FDIC, the Federal Reserve Board, and OCC.

Participants of these meetings said they cover topics such as membership trends, lending practices, regulatory changes, market trends, and emerging risks. For example, several FHLBanks provided updates on underwriting standards, collateral practices, and products, according to FHLBank representatives. Officials from FHFA and the banking regulators reported discussing similar topics during their quarterly meetings, such as implementation of 2024 guidance on the FHLBanks’ credit risk management practices.[79]

Officials from the three banking regulators said they do not regularly communicate with the FHLBanks about the performance of individual member banks.[80] They said they generally rely on information obtained directly from the member banks they supervise. FHLBank representatives generally agreed, noting that regulators already have access to member borrowing data through the banks themselves or public sources.

However, when banking regulators need to request borrowing information from an FHLBank—for instance, when a bank is in distress—FHLBanks are required by regulation to provide borrowing information to the bank’s primary regulator.[81]

Efforts to Improve Routine and Emergency Coordination Between FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks Are Ongoing

When a bank is at risk, timely coordination between FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks may be critical.[82] In some cases, the bank may need to access the Federal Reserve’s discount window to mitigate liquidity shortfalls. If a bank lacks sufficient unencumbered collateral to pledge to the discount window, it may pledge excess FHLBank collateral to its district Reserve Bank.[83] To do so, the FHLBank and Reserve Banks may need to take steps—such as establishing an intercreditor or subordination agreement—to ensure that the Reserve Bank has a perfected security interest in such collateral.

However, during the March 2023 liquidity crisis, there were challenges to coordination between the two systems. Specifically, certain member banks were not operationally ready to borrow from the discount window, which delayed collateral reallocation. For example, the Federal Reserve found that Silicon Valley Bank had limited collateral pledged to the discount window, had not conducted test transactions, and could not quickly reallocate collateral from the FHLBank of San Francisco.[84] The bank failed before the FHLBank and the Federal Reserve Bank could complete the reallocation.[85]

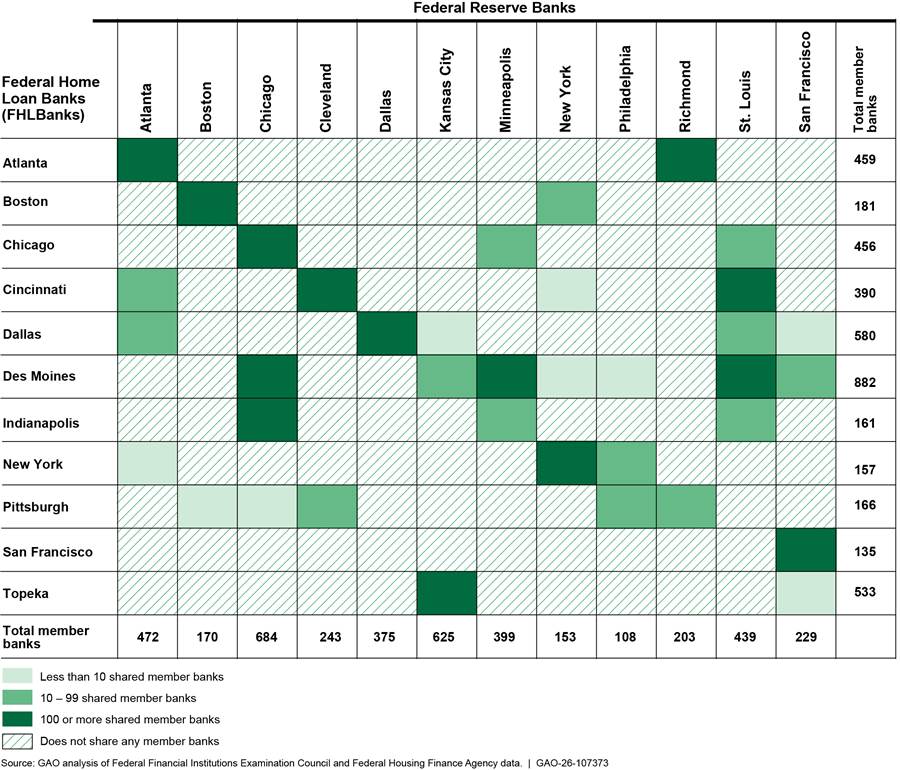

More broadly, coordination is complicated by the complex overlap in membership between the FHLBank and Federal Reserve systems. Thirty-seven unique combinations of FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks share at least one common member bank (see fig. 10). While some institutions share members with only one counterpart, others share with up to seven. The extent of these relationships also varies widely, according to FHFA officials—such as how many members they share (from one shared member to more than 500) or how often they reallocate collateral. In addition, procedures can vary among FHLBanks. For example, one Federal Reserve Bank can share member banks with multiple FHLBanks that each use slightly different subordination agreements, according to Federal Reserve System officials.

Since March 2023, the FHLBanks and Federal Reserve System have initiated two efforts to improve coordination both during periods of stress and during day-to-day operations. First, they have increased engagement between FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks that share members, particularly around the collateral reallocation process. Second, they have established a working group to improve interoperability of the two systems. These efforts are consistent with federal internal control standards on implementing control activities and information and communication, though some efforts are still in early stages.[86] Continued commitment to these coordination efforts will be important to ensure that the FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks are prepared to respond quickly to member liquidity needs during future periods of financial stress.

Increased Engagement Between FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks

After the events of March 2023, the FHLBanks and Federal Reserve Banks began to increase their level of ongoing engagement to address the challenges to the timely reallocation of collateral, according to Federal Reserve System officials and FHLBank representatives. Federal Reserve Board officials said the Board assigned a “lead” Reserve Bank to each FHLBank after March 2023. These lead banks are responsible for coordinating outreach and scheduling meetings, including with other Reserve Banks, such as those that share a small number of members with a given FHLBank.

For the FHLBanks, this increased engagement is in part in response to FHFA’s September 2024 guidance encouraging them to test collateral reallocation processes in conjunction with the Federal Reserve Banks.[87] FHFA officials said they would monitor compliance with this guidance as part of routine supervision and examinations.[88]

FHFA and Federal Reserve Board officials said the structure of their engagement varies depending on the relationship between each FHLBank and the corresponding Reserve Bank. Efforts to improve the collateral reallocation process have included the following:

· Regular meetings between key decision-makers. According to the Federal Reserve Board, the FHLBanks and Reserve Banks have established regular meetings or other communications involving senior executives who would be key decision-makers during emergencies.

· Tabletop exercises. As of July 2025, around 54 percent of all combinations of FHLBanks and Reserve Banks with shared members had conducted tabletop exercises.[89] Additionally, of the 13 combinations of FHLBanks and Reserve Banks that share the most members, 10 have held a tabletop exercise. According to FHLBank representatives, these simulations tested collateral reallocation procedures under hypothetical scenarios involving banks of varying sizes, financial conditions, and readiness to borrow from the discount window. The majority of FHLBanks said they anticipate holding additional exercises going forward, and, as of July 2025, several more exercises were scheduled for later in 2025.