FOOD SAFETY

Further Action Needed to Implement Foodborne Illness Prevention Law and Assess Its Results

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Steve D. Morris at MorrisS@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Since 2015, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued nine rules (regulations) that establish a framework for preventing foodborne illness under the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) enacted in 2011. Separately, FDA has completed most but not all requirements that GAO identified in the law.

The nine rules are significant because they help clarify the specific actions that industry must take at different points in the global supply chain to prevent contamination of human and animal food. For example, one rule sets standards for businesses that grow, harvest, pack, or hold fruits and vegetables. Another rule addresses hazards that could cause illness, death, or economic disruption of the U.S. food supply.

In addition to issuing the rules, FDA has completed 41 of 46 requirements GAO identified in FSMA. For example, FDA has issued guides that are intended to describe in plain language what businesses need to do to comply with rules, and conducted various studies FSMA required. The requirements FDA has not completed are to

· issue guidance on hazard analysis and preventive controls for human food;

· issue guidance to protect against the intentional adulteration, or tampering, of food;

· report on the progress of implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network;

· publish updated good agricultural practices for fruits and vegetables; and

· establish a system to improve FDA’s capacity to track and trace food that is in the U.S.

FDA officials cited competing priorities and an October 2024 agency reorganization as reasons for not fully completing these requirements. In March 2025, FDA officials told GAO they intend to establish the system FSMA requires to help track and trace food by July 2028. However, they did not provide specific time frames for completing the other requirements. Doing so, and then taking action to complete them, would help ensure that industry and others have the information they need to effectively implement FSMA’s preventive framework.

FDA’s efforts to assess how the nine rules are helping to prevent foodborne illness have largely focused on monitoring industry compliance with three rules. This includes overseeing hazards that could affect food safety. However, FDA has not developed a performance management process to guide the agency’s efforts to assess the results of the nine rules.

Key practices for federal performance management emphasize the need for agencies to define what they are trying to achieve, collect relevant information, and use that information to assess how well they are performing and identify how they could improve. FDA officials said the agency prioritized implementing the rules over assessing the results. But developing a performance management process would better position FDA to assess the results of the rules, with the ultimate goal of helping prevent foodborne illness.

Why GAO Did This Study

Each year, foodborne illnesses sicken millions of Americans and cause thousands of deaths. In 2011, Congress enacted FSMA, which shifted the focus of FDA’s food safety program from reacting to, to preventing those illnesses. FDA helps ensure the safety of 80 percent of the U.S. food supply, including fruits and vegetables, processed foods, dairy products, and most seafood.

GAO was asked to review FDA’s efforts to implement FSMA’s preventive framework. This report examines the extent to which FDA has (1) issued rules and completed requirements included in selected sections of FSMA and (2) assessed how the rules are contributing to preventing foodborne illness.

GAO focused on sections of FSMA that provide a foundation for creating a modern, risk-based framework for food safety. GAO compared FDA’s efforts with requirements in FSMA and key practices for federal performance management, which GAO developed based on federal laws, guidance, and past GAO work. GAO also interviewed agency officials and 17 selected stakeholders, representing industry associations, consumer advocacy groups, and state and local regulators.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations, including that FDA take steps to complete requirements included in FSMA, such as issuing guidance, and develop and implement a performance management process to assess whether FDA’s rules have helped prevent foodborne illness. The Department of Health and Human Services concurred with the recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FSMA |

FDA Food Safety Modernization Act |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 7, 2026

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

United States Senate

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Unites States Senate

Each year, foodborne illnesses sicken tens of millions of Americans and cause thousands of deaths. In late 2024, two separate Escherichia (E.) coli outbreaks were linked respectively to the consumption of onions and organic carrots.[1] These outbreaks sickened over 100 individuals across 24 states and resulted in at least two deaths.[2] The year before, 566 children, across 44 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were identified with elevated blood lead levels after consuming cinnamon apple puree and applesauce pouches.[3] Some of the tested samples contained 200 times more lead than is allowed in food. We have long reported on federal efforts to safeguard the nation’s food supply, and we designated improving federal oversight of food safety as a high-risk area in 2007.[4]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is responsible for the safety of almost 80 percent of the U.S. food supply, including fruits, vegetables, processed foods, dairy products, and most seafood.[5] FDA historically focused on reacting to foodborne illnesses after they occur. That changed in 2011 when Congress enacted the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).[6] According to FDA, FSMA marked a historic turning point by requiring that FDA focus on prevention of, rather than reaction to, foodborne illness. FSMA did so, in part, by requiring that FDA promulgate new rules (also called regulations) that together provide a framework for preventing foodborne illness.

Since FSMA’s enactment, we have reported on FDA’s progress in implementing various parts of the law, including challenges it has faced in doing so.[7] In a 2024 report, we found that, although FDA had taken steps to help prepare for compliance with and enforcement of a FSMA-mandated rule to help identify the source of outbreaks of foodborne illness, FDA had not finalized or documented an implementation plan for the rule.[8] Most recently, in a January 2025 report, we found that FDA had not met FSMA’s mandated targets for conducting either domestic or foreign food safety inspections.[9] Among other things, we recommended that FDA develop and implement a performance management process for assessing the results of the agency’s food safety inspection efforts under FSMA because it has not met FSMA’s mandated targets for these inspections since fiscal year 2018.[10] For a list of reports we have issued on FSMA and other selected food safety topics, see the Related Products section at the end of this report.

You asked us to examine issues related to FDA’s efforts to implement and assess FSMA’s preventive framework. Specifically, this report examines the extent to which FDA has (1) issued rules and completed requirements included in selected sections of FSMA and (2) assessed how the rules are contributing to preventing foodborne illness.

In conducting this review, we focused on eight sections of FSMA that FDA has indicated provide a foundation for creating a modern, risk-based framework for food safety:

· Section 103: Hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls,

· Section 105: Standards for produce safety,

· Section 106: Protection against intentional adulteration,

· Section 111: Sanitary transportation of food,

· Section 202: Laboratory accreditation for analyses of foods,

· Section 204: Enhancing tracking and tracing of food and recordkeeping,

· Section 301: Foreign supplier verification program, and

· Section 307: Accreditation of third-party auditors.

To address our first objective, we reviewed the eight sections of FSMA listed above and identified requirements the law specified for the Secretary of HHS to complete.[11] We also reviewed the rules FDA has issued for FSMA under the sections, pertinent FDA documents related to the rules, and our prior work on FSMA. In addition, we interviewed knowledgeable FDA officials to discuss the rules and FDA’s efforts to address the requirements we identified.

In addition for this objective, we interviewed representatives from a non-generalizable selection of 17 stakeholder groups to gather their perspectives on FDA’s implementation of the rules and the agency’s efforts to address FSMA’s requirements.[12] We identified potential stakeholder groups to interview by reviewing our prior reports on FSMA, requesting FDA to identify key stakeholders and also groups that submitted comments to FDA through the Federal Register, and by reviewing a list of organizations with membership in a recently formed coalition focused on the governance of FDA’s Human Foods Program called the FDA Foods Coalition.[13] The final set of 17 stakeholder groups were selected such that there would be at least two knowledgeable group perspectives provided for each of the eight sections of FSMA included in the scope of our review.

To assess the extent to which FDA has completed FSMA’s requirements, we analyzed evidence collected during our document reviews and interviews with agency officials regarding FDA’s efforts toward completing requirements and compared it with the requirements as specified in the law. We considered a requirement “fully completed” if FDA provided evidence that it addressed all of the requirement. We considered a requirement “partially completed” if FDA provided evidence that it addressed some, but not all, of the requirement. Lastly, we considered a requirement “not completed” if FDA did not provide evidence that it addressed any of the requirement. For the purposes of our report, we determined whether FDA completed each of the requirements we identified, based on available evidence, and whether FDA met FSMA’s deadlines for completing each of the requirements. We did not seek to determine the quality of FDA’s actions.

To address our second objective, we reviewed and analyzed each of the rules, data and information on food safety from the FDA-Track website—a publicly available tool for sharing key program performance information—and FDA documents related to assessing the results of the rules, such as FDA’s framework and process for developing the rules’ performance measures. As part of our work, we obtained and analyzed information available on the FDA-Track website regarding domestic and foreign food facilities’ compliance with an FDA requirement to have a written food safety plan for fiscal years 2018 through 2024. We obtained these data for the purpose of including them as illustrative of the type of performance information FDA reports on FSMA.

To ensure the sufficiency and appropriateness of these data, we assessed the data’s reliability in February 2025 by, among other steps, reviewing FDA documentation, performing a spot check of compliance percentages for certain years to ensure data were free from obvious errors and sufficiently accurate, and interviewing knowledgeable agency officials to discuss any limitations or caveats of the data and to ensure the data were complete and accurate. We determined that the data and information were sufficiently reliable to include as an example of the type of performance information FDA publicly reports on FSMA.

In addition, we compared FDA’s efforts to implement and assess the results of the nine rules with GAO’s three-step performance management process, including additional key practices and associated actions, for each step. GAO developed this process to help federal leaders develop and use evidence to effectively manage and assess the results of federal activities, such as FDA’s efforts to assess its progress towards the goal of reducing the risk of foodborne illnesses. We describe the three-step process and practices in our 2023 evidence-based policy making report: setting goals, collecting information and measuring performance, and using performance information.[14]

For both our objectives, we interviewed knowledgeable FDA officials from FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Center for Veterinary Medicine, Division of Enterprise Risk Management, Office of Food Policy and Response, Intergovernmental Affairs, and Office of Regulatory Affairs.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FSMA

Signed into law on January 4, 2011, FSMA represented the largest expansion and overhaul of U.S. food safety authorities since the 1930s with the aim of improving food safety by shifting the focus from responding to foodborne illness to preventing it, according to FDA documents. The law did so by providing FDA with new and expanded food safety authorities and responsibilities to ensure compliance with food safety standards and trace foodborne illness outbreaks in the nation’s food distribution channels. It also expanded FDA’s authority to suspend the registration of a food facility if FDA determines the facility’s food poses a reasonable probability of causing serious adverse health consequences or death to humans or animals.[15]

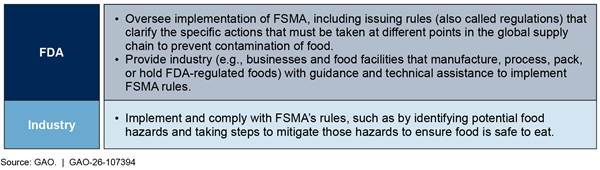

Under FSMA, FDA is responsible for setting food safety standards and conducting oversight of businesses and food facilities (hereafter industry) that grow, harvest, manufacture, process, pack, hold, or import FDA-regulated foods. Industry bears the primary responsibility for implementing and maintaining food safety practices under FSMA.[16] For the purpose of this report, we reviewed various requirements of industry under FSMA. For example, FSMA requires industry to be responsible for identifying potential food hazards in its facilities, such as contaminated food processing equipment that has been inadequately cleaned, which can act as a breeding ground for harmful bacteria. FSMA also requires industry to mitigate those hazards to ensure food is safe to eat. Figure 1 provides an overview of FDA’s and industry’s key responsibilities under FSMA.

Figure 1: Key Responsibilities of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Industry Under the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA)

According to FDA’s Foods and Veterinary Medicine Strategic Plan for fiscal years 2016–2025, FDA intends to accomplish several food safety goals, including incorporating FSMA’s preventive framework and placing a priority on implementing rules, as part of its implementation of FSMA.[17] The primary goal of FDA’s food safety activities, as outlined in the plan, is to protect American consumers and animals from foreseeable hazards. According to this plan, FDA’s intended outcome for establishing FSMA’s preventive framework is to reduce the incidence of illnesses and death attributed to preventable contamination of FDA-regulated foods, including by establishing and gaining high rates of compliance from industry with FSMA’s rules. As part of FDA’s implementation of rules, the agency set staggered compliance dates to give industry time to prepare.[18]

FDA Reorganization

Many offices within FDA have been involved in implementing FSMA. Prior to October 2024, the agency’s Office of Food Policy and Response, Center for Food Safety, and Applied Nutrition and the Center for Veterinary Medicine were primarily responsible for implementing the law and overseeing FDA’s programs that promote human health by preventing foodborne illness and fostering good nutrition. In October 2024, FDA implemented a reorganization that impacted these offices and many parts of the agency. As part of this reorganization, FDA created a new unified Human Foods Program dedicated to preventing foodborne illness, reducing diet-related chronic disease, and ensuring the safety of chemicals in food. Figure 2 shows the organizational structure of the Human Foods Program.

As part of this reorganization, FDA established the Office of Microbiological Food Safety, which works to advance strategies to prevent pathogen-related foodborne illness in close collaboration with other regulatory agencies, states, industry, and other stakeholders. FDA also created a performance evaluation office, known as the Office of Strategic Programs, to manage activities related to risk management and performance measurement to support strategic planning and performance management across the Human Foods Program and evaluate FDA’s progress.

Responsibility for overseeing programs related to animal food and feed remained organized under the Center for Veterinary Medicine. Both the Center for Veterinary Medicine and FDA’s Human Foods Program are organized under the FDA Commissioner.

FDA Has Issued Nine Rules Establishing a Framework for Preventing Foodborne Illness Under FSMA and Has Completed Most but Not All Key Requirements

FDA Issued Nine Rules to Provide the Framework for Preventing Foodborne Illness

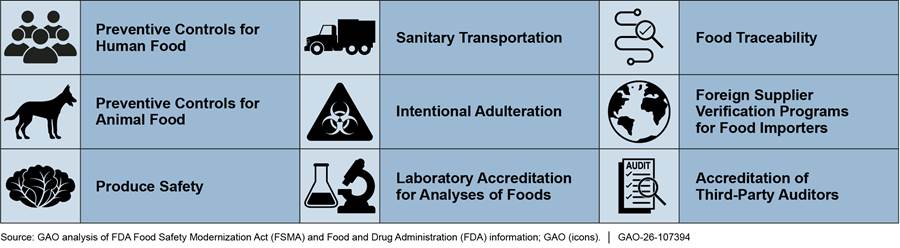

Since September 2015, FDA issued a total of nine rules that create risk-based standards and provide oversight at various points in the supply chain.[19] Widely referred to as the nine foundational rules, these rules constitute the framework for preventing foodborne illness under FSMA. They help FDA implement the eight sections of FSMA discussed above and clarify the specific actions that must be taken at different points in the global supply chain to prevent contamination of both human and animal food (see fig. 3).[20]

Note: In this figure, we refer to the rules using FDA’s terms.

According to FDA officials, by shifting FDA’s focus from reacting to foodborne illness to prevention, the rules help FDA implement FSMA by improving the agency’s capacity to prevent, detect and respond to food safety problems, including those associated with imported food.

Of the nine rules, FDA issued five aimed at improving capacity to prevent food safety problems:

· Preventive Controls for Human Food.[21] Issued in September 2015, this rule updates FDA’s long-standing good manufacturing practice requirements, which were last revised in 1986—25 years before FSMA’s enactment.[22] FDA also added requirements for domestic and foreign facilities to establish and implement hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls, including written food safety plans.[23] Among other things, these requirements are intended to ensure that employees have the combination of education, training, and experience necessary to manufacture, process, pack, or hold food that is clean and safe.

· Preventive Controls for Animal Food.[24] Issued in September 2015, this rule establishes, for the first time, good manufacturing practice requirements for animal food.[25] FDA also added requirements that certain domestic and foreign animal food facilities establish and implement hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls. The rule, among other things, directs the management of an animal food facility to take reasonable measures and precautions to ensure that all persons working in direct contact with animal food, animal food-contact surfaces, and animal food-packaging materials conform to hygienic practices to the extent necessary to protect against the contamination of animal food.

· Produce Safety.[26] Issued in November 2015, this rule establishes science-based minimum standards that apply to businesses that grow, harvest, pack, or hold certain fruits and vegetables, including those that will be imported or offered for import.[27] Among other things, the rule establishes standards for agricultural water quality, employee health and hygiene, the use of biological soil amendments such as compost and manure, and equipment, tools, and buildings, which have been sources of produce contamination.

· Sanitary Transportation.[28] Issued in April 2016, this rule establishes requirements for persons engaged in transporting food to use sanitary transportation practices to ensure the safety of the food they transport for humans and animals. The rule applies to shippers, receivers, loaders, and carriers who transport food in the U.S. by motor vehicle or rail. It establishes requirements to ensure that food is properly refrigerated during transportation and that vehicles and transportation equipment are suitable and adequately cleanable for their intended use, among other things.

· Intentional Adulteration.[29] Issued in May 2016, this rule requires domestic and foreign food facilities to address hazards that may be introduced with the intention to cause wide-scale harm to public health. Those hazards include acts of terrorism targeting the food supply, which while not likely to occur, could cause illness, death, or economic disruption of the food supply.

Of the nine rules, FDA issued two to support improving its capacity to detect and respond to food safety problems:

· Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods.[30] Issued in December 2021, this rule establishes a program to recognize bodies that will accredit laboratories to test food in certain circumstances, such as to support admitting foods detained at the border or removing foods from an import alert.[31] According to the rule, the program is intended to improve the accuracy and reliability of the testing of food by establishing uniform standards and enhancing FDA’s oversight of laboratories that participate in the program.

· Food Traceability.[32] Issued in November 2022, this rule establishes new recordkeeping requirements, beyond those existing before November 2022, for persons who manufacture, process, pack, or hold foods included on FDA’s Food Traceability List.[33] The rule applies to domestic and foreign persons who manufacture, process, pack or hold food for consumption in the U.S., along the entire food supply chain, with some exemptions. For example, the rule applies only to foods regulated by FDA. The additional recordkeeping requirements are intended to allow for faster identification and removal of potentially contaminated food from the market.

Of the nine rules, FDA issued two to directly improve the safety of imported food:

· Foreign Supplier Verification Programs for Food Importers.[34] Issued in November 2015, this rule requires importers to verify that the food they import for humans and animals meets U.S. safety standards. For example, it requires importers to verify that the food they import is produced in compliance with the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Food, and Produce Safety rules; is not adulterated; and is appropriately labeled with respect to food allergens. Hereafter we refer to this rule as the Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rule.

· Accreditation of Third-Party Auditors.[35] Issued in November 2015, this rule establishes a voluntary program for the accreditation of third-party certification bodies, also known as third-party auditors, to conduct food safety audits of foreign entities and issue certifications of foreign facilities and the foods they produce for humans and animals. These certifications are required to participate in FDA’s Voluntary Qualified Importer Program and may be required for foods that FDA determines are subject to certification as a condition for importing food into the U.S.[36]

FDA Has Completed Most but Not All Key Requirements in the Law

According to our analysis, FDA has fully completed 41 of the 46 key requirements we identified.[37] For example, FDA has issued multiple guidance documents, including guides that are intended to describe in plain language what businesses need to do to comply with rules, and conducted various studies FSMA required. See appendix I for further information on the key requirements we determined FDA has completed.

FDA has partially completed three of the remaining key requirements and not completed two. These remaining requirements are important because, in conjunction with the rules, they clarify actions that must be taken to help prevent foodborne illness under FSMA. Specifically, these requirements are to (1) issue guidance on hazard analysis and preventive controls for human food, (2) issue guidance to protect against the intentional adulteration of food, (3) report on the progress of implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network, (4) publish updated agricultural practices for fruits and vegetables, and (5) establish a system to improve FDA’s capacity to track and trace food that is in the U.S. or offered for import.

Table 1 summarizes the three key requirements we determined FDA has partially completed, the due date, and the status of FDA’s efforts to implement the requirements, as of May 2025.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services |

Status |

|

Not specified |

Issue a guidance document related to the regulations promulgated with respect to the hazard analysis and preventive controls. (Section 103: Hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls) |

FDA promulgated regulations for human food separate from animal food. FDA issued draft chapters of the required guidance for human food between August 2016 and January 2024, but not all chapters have been issued and none have been finalized. FDA officials said they continue to work on the guidance but do not have a time frame for finalizing it. FDA issued the required final guidance for animal food in July 2022. |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

Issue guidance documents related to protection against the intentional adulteration of food, including mitigation strategies or measures to guard against such adulteration. (Section 106: Protection against intentional adulteration) |

FDA issued a draft of the required guidance in March 2019 but has not finalized it. FDA officials said they are in the process of updating the guidance but do not have a time frame for finalizing it. |

|

180 days after enactment (i.e., by July 2011), and biennially thereafter |

Submit to the relevant committees of Congress, and make publicly available on the internet web site of the Department of Health and Human Services, a report on the progress in implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network.a (Section 202: Laboratory accreditation for analyses of foods) |

FDA published the required reports through 2019 but not in 2021 or 2023. FDA officials said the agency plans to issue the next report in 2025 but could not provide more details or documentation of this effort. |

Source: GAO analysis of FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: We use the term “key” to refer to requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to complete in the sections of FSMA included in our review. HHS’s FDA is responsible for completing these requirements.

aThe Food Emergency Response Laboratory Network integrates food-testing laboratories at the local, state, and federal levels into a network that is able to respond to emergencies involving biological, chemical, or radiological contamination of food.

Fully completing these requirements would necessitate that FDA take additional action. For example, multiple chapters of the draft guidance documents that FDA has issued in response to FSMA’s section 103 and 106 are incomplete or marked “coming soon.” As of May 2025, FDA did not have time frames for finalizing either guidance document, according to agency officials.

Table 2 summarizes the two key requirements we determined FDA has not completed, the due date, and the status of FDA’s efforts to implement the requirements, as of May 2025.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services |

Status |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

Publish updated good agricultural practices and guidance for the safe production and harvesting of fresh produce. (Section 105: Standards for produce safety) |

FDA has not begun work to update its good agricultural practices and FDA officials said the agency does not have a time frame for beginning the work. |

|

Not specified |

Establish within FDA a product tracing system to receive information that improves capacity to effectively and rapidly track and trace food that is in the U.S. or offered for import. (Section 204: Enhancing tracking and tracing of food and recordkeeping) |

FDA began developing the system in 2024 and FDA officials said they expect to have it complete by July 2028. |

Source: GAO analysis of FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: We use the term “key” to refer to requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to complete in the sections of FSMA included in our review. HHS’s FDA is responsible for completing these requirements.

With respect to the two key requirements FDA has not completed:

· Section 105 of FSMA required FDA to publish updated good agricultural practices for fruits and vegetables. FDA’s good agricultural practices and guidance are important because they help farmers reduce the risk of contaminating food, and FSMA required that FDA update them no later than 1 year after its enactment (i.e., by January 2012). FDA missed this deadline and has not updated them. Consequently, FDA’s current good agricultural practices are more than 25 years old.[38] FDA officials told us that, in implementing FSMA, the agency prioritized finalizing guidance for the Produce Safety rule above updating its good agricultural practices. However, as of May 2025, agency officials also told us FDA had not established a time frame for beginning work to update its good agricultural practices to reflect FSMA’s focus on preventing foodborne illness.

· Section 204 of FSMA required FDA to establish a product tracing system to enhance the agency’s existing foodborne outbreak response processes. As we previously reported, this system is important because it is intended to allow FDA to analyze food traceability data more effectively and rapidly.[39] FDA began developing this system in 2024, and agency officials told us work is currently underway to develop the system. In March 2025, agency officials told us they anticipated its development would be complete by the time industry was required to comply with the Food Traceability rule in January 2026.[40] However, FDA subsequently announced it intended to extend the compliance date for the rule by 30 months—to July 2028.[41] In May 2025, FDA officials told us they expected the system will be complete by July 2028 and noted that extending the compliance date will provide the agency with opportunities to test the system with industry.

According to FDA officials, competing priorities have delayed or prevented them from fully completing, the five key requirements discussed above. Agency officials described FSMA’s implementation as a significant undertaking and said FDA prioritized implementing the nine foundational rules among FSMA’s many requirements. FDA officials also noted the challenge of simultaneously supporting FDA’s response to large-scale events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, expanding consumer access to infant formula products, and implementing FDA’s recent reorganization.

During our interviews with representatives from 17 selected stakeholder groups (which we refer to as “stakeholders”) representing industry associations, consumer advocacy organizations, and nonfederal regulatory organizations, stakeholders noted the significance of issuing the nine foundational rules discussed above.[42] For example, three stakeholders said rules FDA has issued have helped position industry to identify hazards that could affect food safety. When we asked stakeholders for their views on FDA’s actions to address the requirements, however, 12 stakeholders told us that FDA took too long to issue rules or complete certain requirements. In addition, 13 stakeholders told us more guidance is needed to ensure that industry and others understand the rules and can implement them. For example, one stakeholder told us a lack of guidance disincentivizes investments in food safety because businesses may be hesitant to invest in technology or training if FDA’s requirements are unclear. According to another stakeholder, guidance such as best practices is needed to help ensure that farmers understand FDA’s current thinking on how to reduce the risk of contaminating food so they can implement FSMA’s preventive framework.

Stakeholders also noted the importance of completing certain FSMA requirements. For example, according to one stakeholder, establishing the product tracing system required under FSMA’s section 204 is vital for improving FDA’s capacity to detect and respond to food safety problems. According to another, the reports FDA has issued in the past under FSMA’s section 202 have been helpful but would benefit from more discussion of FDA’s responses to food-related emergencies and advances that have been made, such as the use of whole genome sequencing to establish the size and breadth of outbreaks.[43] However, FDA has not issued a report since 2019—more than 5 years ago.

We recognize that issuing the nine foundational rules and completing many of FSMA’s requirements was a significant undertaking, and we have previously reported that the rulemaking process requires resources and can take years.[44] However, FDA still has not completed five of the key requirements that help implement the law’s preventive framework and does not have time frames for completing three of them. Project management standards state that organizations should estimate the duration of activities and create a schedule with milestones and time frames (or timelines) to execute them.[45] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[46] This includes communicating with external parties such as Congress and stakeholders so they can help the organization achieve its objectives.

Establishing time frames for completing the FSMA requirements discussed above could better ensure success as FDA continues to implement FSMA’s preventive framework. For those requirements for which FDA is in the early stages of completing or has not yet begun, establishing both milestones and timelines for doing so would also better position FDA to track its progress, identify potential risks, and make adjustments as needed Completing the requirements would help address stakeholder concerns that industry and others may not have the information they need to effectively implement the rules and FSMA’s preventive framework. If FDA is unable to complete certain requirements as planned, such as publishing a report on the progress in implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network in 2025, informing Congress and stakeholders of when it expects to do so would and provide additional accountability and support congressional oversight.

Opportunities Exist to Better Assess the Results of FDA’s FSMA Rules

FDA Collected and Reported Information Largely on Industry Compliance for Some Rules

FDA’s efforts to assess how its rules under FSMA are helping to prevent foodborne illness have largely focused on monitoring industry compliance with three of the nine FSMA rules––the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Food, and Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rules. This information helps FDA monitor and track implementation of these rules. Specifically, officials told us FDA has used its FDA-Track website to collect and report information on industry compliance and other aspects of these three rules. FDA-Track is a publicly available tool with dashboards that FDA uses to share key program performance information.[47]

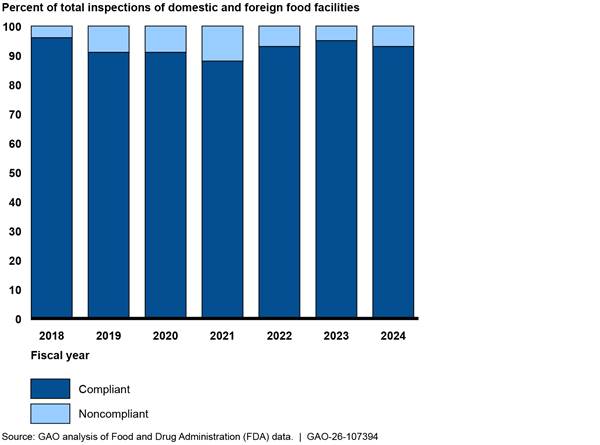

According to the FDA-Track website, FDA also uses the dashboards to monitor progress toward achieving key outputs over time.[48] For example, for the Preventive Controls for Human Food rule, FDA reports information on industry compliance with several of the rule’s requirements, such as the requirement to have a written food safety plan. Under this rule, food facilities are required to implement a written food safety plan to help, in part, evaluate hazards that could affect food safety and specify what actions a food facility will take to correct identified problems. Accordingly, FDA monitors the number of inspections in which facilities have written food safety plans. For example, FDA reported relatively high levels of compliance with this requirement in fiscal years 2018 through 2024 through FDA-Track (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Food Facilities’ Compliance with FDA Requirement to Have a Written Food Safety Plan for Human Food, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

FDA reported similar information for the Preventive Controls for Animal Food rule. For the Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rule, FDA reports information on the number of recalls of imported food and the results of inspections.[49] For example, FDA reported there were nearly 70 recalls attributed to imported human food during fiscal year 2024.

FDA Missed Opportunities to Assess the Results of the Nine Rules and Their Contribution to Preventing Foodborne Illness

FDA missed opportunities to assess the results of the nine rules and their contribution to preventing foodborne illness. While FSMA does not require FDA to conduct an evaluation of its efforts to implement and assess the results of the rules, our prior work has emphasized the need for agencies to define what they are trying to achieve, collect relevant information, and use that information to determine how well they are performing and identify what they could do to improve results. Since 1990, a series of federal laws and executive actions have established requirements for agencies to build and use different types of evidence to understand and improve results. Evidence can include performance information, program evaluations, statistical data, and other research and analysis. We have previously reported that planning practices required at the federal agency level under the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 can serve as leading practices for planning at lower levels within agencies such as individual programs or initiatives.[50] These practices and associated Office of Management and Budget guidance, together with practices we have identified, provide a framework of leading practices to plan for results, build evidence, and use evidence to assess results.[51]

FDA’s use of FDA-Track to report and monitor industry compliance with the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Food, and Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rules has helped FDA assess implementation of the rules, according to FDA officials. However, these efforts do not constitute a performance management process, which FDA has made intermittent efforts to develop since 2016. FDA has not analyzed the results of FSMA’s nine rules, such as whether the Preventive Controls for Human Food rule is contributing to preventing foodborne illness, partly because FDA had not taken sufficient steps to establish a formal, systematic performance management process to measure the results of each of the rules. FDA officials said that efforts the agency had initiated in the past to measure the results of the rules have been challenging to complete due to competing priorities. For example, FDA officials told us that in 2016 the agency began identifying data and information needed to develop performance measures for some of the rules. However, that effort was not completed due to competing priorities—such as addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020—as well as the agency’s focus on issuing the rules and addressing the law’s numerous requirements, according to agency officials.

In October 2024, following the creation of a new unified Human Foods Program, FDA announced on its website that the agency planned to develop a performance management framework using data reported in FDA-Track to guide FDA’s efforts to monitor FSMA’s implementation. According to FDA, this framework would leverage the existing information FDA reports for the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Food, and Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rules, while also enabling the agency to begin developing measures for the other six rules, starting with the Produce Safety rule. To develop this framework, FDA created the Office of Strategic Programs, focused on strategic planning, performance, and evaluation of the Human Foods Program.

However, FDA officials told us that key staff from the Office of Strategic Programs were included in workforce reductions HHS announced in March 2025 involving FDA.[52] As of May 2025, FDA officials said that while the office no longer existed, developing a performance management framework to guide FDA’s efforts to monitor FSMA’s implementation remained a priority. However, they also said they could not provide a draft or a time frame for developing this framework.

We have previously distilled the following steps of a performance management process from decades of reviews: setting goals to identify results to achieve, collecting information to measure performance, and using that information to assess results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving those goals.[53] We developed this three-step process to help decision-makers at agencies assess the results of activities and support Congress’s oversight of federal efforts such as FDA’s implementation of FSMA.

Under the first step, our prior work shows that agencies should set clear goals. These goals should communicate both long-term outcomes (e.g., strategic goals) and near-term measurable results (e.g., performance goals). Under step two, our prior work shows that agencies should collect performance information—a type of evidence—to determine how well they are achieving their goals and objectives.[54] Finally, under step three, our prior work shows that agencies should regularly use that information to identify what they could do to improve results, which may be done on a monthly or quarterly basis. In table 3 we compare FDA’s reporting and monitoring efforts with the three steps we previously identified.

Table 3: Comparison of FDA Actions to Assess the Results of Its FSMA Rules with GAO’s Three-Step Performance Management Process

|

Step |

FDA action |

Example |

Opportunity |

|

Set goals to identify results to achievea |

Established broad, long-term outcomes for each of the nine rules. |

In 2015, FDA finalized the Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rule to ensure the safety of imported food. FDA developed a long-term outcome for that rule, which is to reduce the risk of illness or injury attributed to imported foods. |

Set performance goals for all nine rules. |

|

Collect information to measure performance |

Collected information on the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Foods, and Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rules. Documented a process to measure performance for all the rules, including for developing performance measures for the Preventive Controls for Human Food, Preventive Controls for Animal Foods, and Foreign Supplier Verification Programs rules. |

From 2018 to 2024, FDA collected information on industry compliance with several of the Preventive Controls for Human Food rule’s requirements, such as the requirement for industry to have a written food safety plan. In 2016, FDA documented a process called Prioritizing FSMA Results to identify data needed to establish performance measures for the rules. However, FDA did not complete implementation of this effort. |

Collect performance information on six of the rules and complete implementation of an effort to measure performance of all the rules. This effort would include developing performance measures for six of the rules. |

|

Use that information to assess results and inform decisions |

Used some performance information on an ad hoc basis to learn about and monitor implementation of the Produce Safety rule. |

In 2024, FDA amended the Produce Safety rule by using qualitative data, such as stakeholder feedback.b |

Regularly use performance information to assess progress toward goals and inform decisions. |

Source: GAO analysis of FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: GAO compared FDA’s actions to assess the results of its rules with the three-step performance management process characterized in GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

aAccording to our prior work, goals should cover two time frames: long-term outcomes and near-term results. Long-term outcomes are generally known as strategic goals or strategic objectives (e.g., prevent foodborne illness). Near-term results are generally known as performance goals with quantitative targets and time frames against which performance can be measured (e.g., reduce foodborne pathogens by 20 percent by 2030).

bFDA issued an amendment to the Produce Safety rule in 2024 known as the Pre-Harvest Agricultural Water rule.

In addition, we have developed additional practices to elaborate on the performance management process and help agencies take practical steps to implement the three steps.[55] For example, under the second step, collecting information and measuring performance, our prior work shows that FDA could take steps to develop other types of evidence to better assess results. This could involve creating an evidence-building plan, which could describe the data, methods, and analytical approaches—or evidence—that would be used to identify new information FDA would need to assess progress towards achieving goals for each of the nine rules.[56]

FDA could then use that plan to prioritize how and when to fulfill the agency’s information needs beyond collecting information on industry compliance. As part of this, FDA could also identify and assess existing sources of health data, such as outbreak illnesses and hospitalizations, for their usefulness and reliability for assessing trends related to foodborne illnesses, for example. If FDA develops an evidence-building plan, the information that FDA collects and reviews on a regular basis could allow the agency to draw conclusions in advance of assessing outcomes (e.g., provide an early warning system that allows for corrections, when necessary, if goals are at risk of not being met).

FDA officials stated that the agency was aware of the three-step performance management process, but has not used it for assessing the nine rules. In May 2025, FDA officials told us that a key resource that could assist with efforts to identify and collect information about the nine rules was included in the workforce reductions HHS announced earlier in March. However, FDA’s Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Risk Management and HHS’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation may be able to provide assistance in assessing the results of the rules, contingent on competing priorities and availability of resources, according to FDA officials.[57] Developing and implementing a performance management process would better position FDA to understand how well the rules are working and take corrective actions, as needed, with the ultimate goal of helping prevent foodborne illness.

Conclusions

Foodborne illnesses sicken tens of millions of Americans each year, and FSMA’s enactment in 2011 marked a historic turning point by shifting FDA’s food-safety focus from reacting to preventing foodborne illness, according to FDA. FDA has taken important steps to implement most requirements in FSMA and monitor implementation of some of the nine rules the agency established under FSMA. However, FDA has not fully implemented certain sections of the law focused on preventing foodborne illness, such as issuing updated guidelines to help farmers reduce the risk of contaminating food, or established time frames to complete requirements. Without FDA doing so, businesses, farmers, and other stakeholders may not have the information they need to effectively implement FSMA’s preventive framework for reducing foodborne illness.

FDA has reported some performance information for a few rules and amended one based on stakeholder feedback and informal reviews. However, FDA has not established a performance management process so that the results of each rule can be measured, consistent with leading practices. As FDA completes its performance management framework, developing and implementing a performance management process that helps put the framework into practice would enable FDA to better assess whether the rules are achieving their intended results. Given the agency’s competing priorities, developing and implementing a performance management process would better position FDA to understand how well the rules are working and take corrective actions, as needed, with the ultimate goal of helping prevent foodborne illness.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following seven recommendations to FDA:

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program establishes a time frame for finalizing the agency’s guidance for hazard analysis and preventive controls for human food and issues the guidance as required by FSMA’s section 103. (Recommendation 1)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program establishes a time frame for finalizing the agency’s guidance to protect against the intentional adulteration of food and issues the guidance as required by FSMA’s section 106. (Recommendation 2)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program publishes a report in 2025 on the progress in implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network, as required by FSMA’s section 202. If FDA does not expect to publish a report in 2025, it should inform Congress and stakeholders, in a timely manner, of when it expects to publish the report. (Recommendation 3)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program establishes milestones and timelines for publishing future reports on the progress in implementing a national food emergency response laboratory network and publishes the reports as required by FSMA’s section 202. (Recommendation 4)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program establishes milestones and timelines for updating the agency’s good agricultural practices for fruits and vegetables and publishes them as required by FSMA’s section 105. (Recommendation 5)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure that the Human Foods Program develops a plan with milestones and timelines for establishing a product tracing system to enhance FDA’s existing foodborne outbreak response processes, and establishes the system as required by FSMA’s section 204. (Recommendation 6)

The Commissioner of FDA should ensure the Human Foods Program and Center for Veterinary Medicine develops and implements a performance management process to assess the results of FDA’s rules and their contribution to the prevention of foodborne illness. This process should include setting goals to identify results to achieve, collecting information to measure performance, and using that information to assess results and inform decisions for each rule. (Recommendation 7)

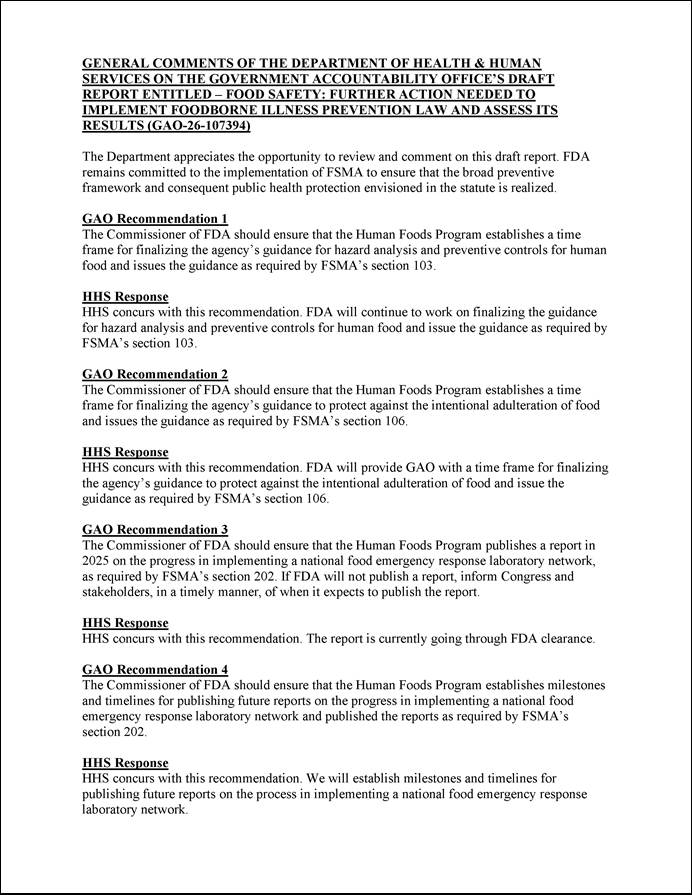

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, HHS concurred with our recommendations and identified steps it would take to address them. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at MorrisS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Steve D. Morris

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

Appendix

I: Key FDA Food Safety Modernization Act Requirements That

FDA Has Completed, as of May 2025

The FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), signed into law on January 4, 2011, sets forth specific requirements for the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to complete.[58] This includes requirements to conduct studies and issue guidance and regulations. Within HHS, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for completing these requirements.

We determined that FDA has fully completed 41 of the 46 key requirements we identified under FSMA.[59] We considered a requirement “fully completed” if FDA provided evidence that it addressed all of the requirement. For the purposes of our report, we determined whether FDA completed each of the requirements we identified, based on available evidence, and whether FDA met FSMA’s deadlines for completing requirements. We did not seek to determine the quality of FDA’s actions.

FSMA includes over 40 sections, and table 4 lists the eight sections included in our review.

|

Section |

Description |

|

103 |

Hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls |

|

105 |

Standards for produce safety |

|

106 |

Protection against intentional adulteration |

|

111 |

Sanitary transportation of food |

|

202 |

Laboratory accreditation for analyses of foods |

|

204 |

Enhancing tracking and tracing of food and recordkeeping |

|

301 |

Foreign supplier verification program |

|

307 |

Accreditation of third-party auditors |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). | GAO‑26‑107394

Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls

Section 103 of FSMA requires the Secretary of HHS to take certain actions to establish hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls. We determined that Section 103 includes eight requirements that the Secretary is to complete, and these requirements apply to facilities that produce both human and animal food. Table 5 summarizes the seven requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

Table 5: Seven Completed Requirements for FSMA’s Section 103, Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

In consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture, conduct a study on the food processing sector regulated by FDA. The study should determine the · distribution of food production by type and size of operation, including the monetary value of food sold; · proportion of food produced by each type and size of operation; · number and types of food facilities collocated on farms, including the number and proportion by commodity and by manufacturing or processing activity; · incidence of foodborne illness originating from each size and type of operation and the type of food facilities for which no reported or known hazard exists; and · effect on foodborne illness risk associated with commingling, processing, transporting, and storing food and raw agricultural commodities, including differences in risk based on the scale and duration of these activities. |

August 2015 for both human and animal food |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Submit to Congress a report that describes the results of the study conducted. |

August 2015 for both human and animal food |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Promulgate regulations · in coordination with the Secretary of Homeland Security, establish science-based minimum standards for conducting a hazard analysis, documenting hazards, implementing preventive controls, and documenting the implementation of the preventive controls; and · to define the terms small business and very small business, taking the study into consideration. In defining these terms, the Secretary should also consider harvestable acres, income, the number of employees, and the volume of food harvested. |

September 2015 for both human and animal food |

|

9 months after enactment (i.e., by October 2011) |

Publish a notice of proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register to promulgate regulations with respect to activities that constitute · on-farm packing or holding of food that is not grown, raised, or consumed on such farm or another farm under the same ownership; and · on-farm manufacturing or processing of food that is not consumed on that farm or on another farm under common ownership. |

January 2013 for human food and October 2013 for animal food |

|

9 months after the close of the comment period for the proposed rulemaking (i.e., by August 2014 for human food and by November 2014 for animal food) |

Adopt final rules with respect to · activities that constitute on-farm packing or holding of food that is not grown, raised, or consumed on such farm or another farm under the same ownership; · activities that constitute on-farm manufacturing or processing of food that is not consumed on that farm or on another farm under common ownership; and · the requirements, as added by this act, from which the Secretary may issue exemptions or modifications of the requirements for certain types of facilities. |

September 2015 for both human and animal food |

|

180 days after the issuance of the regulations (i.e., by March 2016 for both human and animal food) |

Issue a small entity compliance policy guide setting forth in plain language the requirements to assist small entities with complying with the hazard analysis and other required activities. |

October 2016 for both human and animal food |

|

180 days after enactment |

Update the Fish and Fisheries Products Hazards and Control Guidance to take into account advances in technology that have occurred since the Secretary’s previous publication of this guidance. |

June 2022 for human fooda |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

aWe determined that this requirement applied to human food but not animal food.

Note: Section 103 includes eight requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services is to complete. We determined that one of the eight requirements was not fully completed because FDA needed to take additional action.

Standards for Produce Safety

Section 105 of FSMA requires the Secretary of HHS to take certain actions to establish standards for produce safety. Table 6 summarizes the five requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

In coordination with the Secretary of Agriculture and representatives of State departments of agriculture, and in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security, publish a notice of proposed rulemaking to establish science-based minimum standards for the safe production and harvesting fruits and vegetables for which the Secretary has determined that standards minimize the risk of serious adverse health consequences or death. |

January 2013 |

|

During the comment period of the proposed rule (i.e., by November 2013) |

During the comment period on the notice of proposed rulemaking, conduct no less than three public meetings in diverse geographical areas of the U.S. to provide persons in different regions an opportunity to comment. |

March 2013 |

|

1 year after the close of the comment period for the proposed rulemaking (i.e., by May 2014) |

Adopt a final regulation to provide for minimum science-based standards for fruits and vegetables, including specific mixes or categories of fruits or vegetables, based on known safety risks, which may include a history of foodborne illness outbreaks. |

November 2015 |

|

Not specified |

Conduct no fewer than three public meetings in diverse geographical areas of the U.S. as part of an effort to conduct education and outreach regarding the guidance. |

December 2018 |

|

180 days after the issuance of the regulations (i.e., by May 2016) |

Issue a small entity compliance policy guide setting forth in plain language the requirements to assist small entities in complying with standards for safe production and harvesting and other required activities. |

September 2017 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: Section 105 includes six requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services is to complete. We determined one of the six requirements was not fully completed because FDA needed to take additional action.

Protection Against Intentional Adulteration

Section 106 of FSMA requires the Secretary of HHS to take certain actions to establish standards to protect against intentional adulteration. Table 7 summarizes the three requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

Table 7: Three Completed Requirements for FSMA’s Section 106, Protection Against Intentional Adulteration

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

Not specified |

Conduct a vulnerability assessment of the food system. The assessment should · consider Department of Homeland Security biological, chemical, radiological, or other terrorism risk assessments; · consider the best available understanding of uncertainties, risks, costs, and benefits associated with guarding against intentional adulteration of food at vulnerable points; and · determine the types of science-based mitigation strategies or measures that are necessary to protect against the intentional adulteration of food. |

April 2013 |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Promulgate regulations in coordination with the Secretary of Homeland Security and in consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture, to protect against the intentional adulteration of food subject to this act. |

May 2016 |

|

Not specified |

Periodically review and, as appropriate, update the regulations and guidance documents. |

February 2020 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: Section 106 includes four requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services is to complete. We determined one of the four requirements was not fully completed because FDA needed to take additional action.

Sanitary Transportation of Food

Section 111 of FSMA requires the Secretary of HHS to take certain actions to establish standards for the sanitary transportation of food. Table 8 summarizes the two requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Promulgate regulations to require shippers, carriers by motor vehicle or rail vehicle, receivers, and other persons engaged in the transportation of food to use sanitary transportation practices prescribed by the Secretary to ensure that food is not transported under conditions that may render the food adulterated. |

April 2016 |

|

Not specified |

Acting through the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, conduct a study of the transportation of food for consumption in the U.S., including transportation by air, that includes an examination of the unique needs of rural and frontier areas with regard to the delivery of safe food. |

August 2017 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods

Section 202 of FSMA requires the Secretary to take certain actions to establish standards for the laboratory accreditation for analyses of foods. Table 10 summarizes the five requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

Table 9: Five Completed Requirements for FSMA’s Section 202, Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

2 years after enactment (i.e., by January 2013) |

Establish a program for the testing of food by accredited laboratories. |

December 2021 |

|

2 years after enactment (i.e., by January 2013) |

Establish · a publicly available registry of accreditation bodies recognized by the Secretary and laboratories accredited by a recognized accreditation body, including the name of, contact information for, and other information deemed appropriate by the Secretary about such bodies and laboratories; and · require, as a condition of recognition or accreditation, as appropriate, that recognized accreditation bodies and accredited laboratories report to the Secretary any changes that would affect the recognition of such accreditation body or the accreditation of such laboratory. |

December 2021 |

|

Not specified |

Work with the recognized accreditation bodies as appropriate, to increase the number of qualified laboratories that are eligible to perform testing beyond the number so qualified on the date of enactment. |

June 2024 |

|

Not specified |

Develop model standards that a laboratory shall meet to be accredited by a recognized accreditation body for a specified sampling or analytical testing methodology and included in the registry. |

December 2021 |

|

Not specified |

· Periodically and in no case less than once every 5 years, reevaluate the recognized accreditation bodies to assess whether they meet the criteria for recognition. · Promptly revoke the recognition of any accreditation body found not to be in compliance with the requirements of this act, specifying, as appropriate, any terms and conditions necessary to continue to perform testing. |

December 2021 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: Section 202 includes six requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services is to complete. We determined one of the six requirements was not fully completed because FDA needed to take additional action.

Enhancing Tracking and Tracing of Food and Recordkeeping

Section 204 of FSMA requires the Secretary to take certain actions to establish standards for enhancing tracking and tracing of food and recordkeeping. Table 10 summarizes the nine requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

Table 10: Nine Completed Requirements for FSMA’s Section 204, Enhancing Tracking and Tracing of Food and Recordkeeping

|

Not later than…. |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

270 days after enactment (i.e., by October 2011) |

Establish pilot projects in coordination with the food industry to · explore and evaluate methods to rapidly and effectively identify recipients of food to prevent or mitigate a foodborne illness outbreak and · address credible threats of serious adverse health consequences or death to humans or animals as a result of such food being adulterated. |

August 2012a |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Report to Congress on the findings of the pilot projects together with recommendations for improving the tracking and tracing of food. |

November 2016 |

|

Not specified |

In coordination with the Secretary of Agriculture and multiple representatives of State departments of health and agriculture, assess · the costs and benefits associated with the adoption and use of several product tracing technologies, including technologies used in the pilot projects; · the feasibility of such technologies for different sectors of the food industry, including small businesses; and · whether such technologies are compatible with the requirements of this act. |

August 2012 |

|

Not specified |

To the extent practicable · evaluate domestic and international product tracing practices in commercial use; · consider international efforts, including an assessment of whether product tracing requirements developed are compatible with global tracing systems; and · consult with a diverse and broad range of experts and stakeholders, including representatives of the food industry, agricultural producers, and nongovernmental organizations that represent the interests of consumers. |

August 2012 |

|

2 years after enactment (i.e., by January 2013) |

Publish a notice of proposed rulemaking to establish recordkeeping requirements for facilities that manufacture, process, pack, or hold foods that the Secretary designates as high-risk foods. |

September 2020 |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

Designate high-risk foods for which additional recordkeeping requirements are appropriate and necessary to protect the public health. |

November 2022 |

|

At the time of promulgation of a final rule (i.e., by November 2022) |

Publish, at the time the Secretary promulgates the final rules, the list of the foods designated as high-risk foods on the internet website of FDA. |

November 2022 |

|

Not specified |

During the comment period in the notice of proposed rulemaking, conduct no less than three public meetings in diverse geographical areas of the U.S. to provide persons in different regions an opportunity to comment. |

December 2020 |

|

180 days after promulgation of a final rule (i.e., by May 2023) |

Issue a small entity compliance guide setting forth in plain language the requirements of the regulations in order to assist small entities, including farms and small businesses, in complying with the recordkeeping requirements. |

May 2023 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Note: Section 204 includes 10 requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services is to complete. We determined one of the 10 requirements was not fully completed because FDA needed to take additional action.

aIn September 2011, FDA tasked the Institute of Food Technologists to perform the pilot projects Section 204 of FSMA requires. The Institute of Food Technologists submitted the final report for the pilot projects to FDA in August 2012. See Institute of Food Technologists, McEntire, J., Pilot Projects for Improving Product Tracing along the Food Supply System – Final Report (Chicago, IL: August 2012).

Foreign Supplier Verification Program

Section 301 of FSMA requires the Secretary to take certain actions to establish a foreign supplier verification program. Table 11 summarizes the four requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

Issue guidance to assist importers in developing foreign supplier verification programs. |

January 2023 |

|

1 year after enactment (i.e., by January 2012) |

Promulgate regulations to provide for the content of the foreign supplier verification program. |

November 2015 |

|

Not specified |

Establish, by notice published in the Federal Register, an exemption for articles of food imported · in small quantities for research and evaluation purposes or · for personal consumption, provided that such foods are not intended for retail sale and are not sold or distributed to the public. |

November 2015 |

|

Not specified |

Publish and maintain on the internet website of FDA a current list of participating importers that includes their name, location, and other information deemed necessary by the Secretary. |

September 2018 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

Accreditation of Third-Party Auditors

Section 307 of FSMA requires the Secretary to take certain actions to establish standards for the accreditation of third-party auditors. Table 12 summarizes the six requirements we determined the Secretary has completed, the due date, and the date completed.

|

Not later than… |

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall… |

Date completed |

|

2 years after enactment (i.e., by January 2013) |

Establish a system for the recognition of accreditation bodies that accredit third-party auditors to certify that eligible entities meet applicable requirements. |

November 2015 |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Develop model standards, including requirements for regulatory audit reports, with each recognized accreditation body ensuring that third-party auditors and audit agents of such auditors meet such standards in order to qualify such third-party auditors as accredited. In developing the model standards, look to standards in place on the date of the enactment of this section for guidance, to avoid unnecessary duplication of efforts and costs. |

February 2022 |

|

18 months after enactment (i.e., by July 2012) |

Promulgate regulations to ensure that there are protections against conflicts of interest between an accredited third-party auditor and the eligible entity to be certified by such auditor or audited by such audit agent. Such regulations shall include · requiring that audits be unannounced; · a structure to decrease the potential for conflicts of interest, including timing and public disclosure, for fees paid by eligible entities; and · appropriate limits on financial affiliations between an accredited third-party auditor and any person that owns or operates an eligible entity to be certified. |

November 2015 |

|

Not specified |

Establish by regulation a reimbursement (user fee) program by which the Secretary assesses fees and requires accredited third-party auditors and audit agents to reimburse FDA for the work performed to establish and administer the system. |

December 2016 |

|

Not specified |

Periodically, or at least once every 4 years, · reevaluate the accreditation bodies and · evaluate the performance of each accredited third-party auditor. |

July 2020 |

|

Not specified |

Establish a publicly available registry of accreditation bodies and of accredited third-party auditors, including their name, contact information, and other information deemed necessary by the Secretary. |

January 2018 |

Source: GAO analysis of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information. | GAO‑26‑107394

GAO Contact

Steve D. Morris, MorrisS@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Nkenge Gibson (Assistant Director), Wesley A. Johnson (Analyst in Charge), Adrian Apodaca, Kevin Bray, Rebecca Conway, Hayden Huang, Mae Jones, Benjamin T. Licht, Norma-Jean Simon, Amber Sinclair, and Rajneesh Verma made key contributions to this report.

Food Safety: Status of Foodborne Illness in the U.S. GAO‑25‑107606. Washington, D.C.: February 3, 2025.

Food Safety: USDA Should Take Additional Actions to Strengthen Oversight of Meat and Poultry. GAO‑25‑107613. Washington, D.C.: January 22, 2025.