HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Challenges and Opportunities Associated with Anti-Trafficking Projects in Conflict-Affected Countries

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Chelsa Kenney at kenneyc@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have funded and implemented projects to combat forced labor and sex trafficking, including some projects in countries affected by armed conflict. From fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024, State and USAID obligated about $437 million for anti-trafficking projects. This included funding for projects in conflict-affected countries such as Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia. However, a January 2025 executive order paused U.S. foreign development assistance. In April 2025, State began a reorganization, and in July 2025, the Secretary of State announced that USAID had ceased providing foreign assistance. As a result, during the first two quarters of fiscal year 2025, State had no new obligations and de-obligated $1.4 million and USAID obligated $1 million and de-obligated about $1.1 million from anti-trafficking projects. As of September 2025, some of State’s anti-trafficking programming remained. Agency officials said that, going forward, State planned to focus on producing its required annual Trafficking in Persons Report—a report describing the anti-trafficking efforts of the United States and foreign governments.

Officials from agencies and implementing partner organizations identified challenges affecting anti-trafficking project implementation in conflict-affected countries. They also identified opportunties to strengthen project implementation in any future efforts.

Stakeholders Identified Challenges and Opportunities to Strengthen Implementation of Anti-Trafficking Projects in Conflict-Affected Countries

|

Challenges to Implementation |

Opportunities to Strengthen Implementation |

|

· Prioritization of humanitarian aid over anti-trafficking efforts · Increased vulnerabilities to trafficking in conflict-affected countries · Changing trafficking patterns in conflict-affected countries · Impaired prevention and awareness among vulnerable populations · Interrupted access to conduct protection activities · Limited program management flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances in conflict · Difficulties in coordinating and partnering with local and international stakeholders · Limited local partner capacity to conduct anti-trafficking efforts · Corruption and evidence requirements for prosecuting trafficking cases |

· Continue U.S. policy emphasis on anti-trafficking efforts · Build local partner capacity through training, technology, and best practices · Allow implementing partners greater flexibility to adapt when conflict interrupts planned anti-trafficking activities · Facilitate coordination among international and local anti-trafficking partners · Provide additional funding for anti-trafficking programming |

Source: GAO analysis of discussion group responses. | GAO-26-107406

Note: We held eight discussion groups with a total of 47 stakeholders from December 2024 to March 2025. Stakeholders included U.S. agency officials managing anti-trafficking projects and representatives of organizations implementing projects in Ukraine, Romania, Moldova, and Ethiopia.

Why GAO Did This Study

Human trafficking is a global threat that armed conflict exacerbates. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 prompted widespread concern about trafficking in Ukraine and other conflict-affected countries. This report is one of several engagements GAO initiated in response to a provision in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023.

This report describes State and USAID funding for anti-trafficking projects globally and in four conflict-affected countries—Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia. Among other objectives, this report also describes challenges and opportunities to strengthen implementation of anti-trafficking projects in conflict-affected countries.

GAO analyzed agency documentation and funding data and interviewed and analyzed discussion responses from 47 agency officials and representatives from implementing partner organizations from eight discussion groups held from December 2024 to March 2025.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ADS |

Automated Directives System |

|

CPI |

Common Performance Indicator |

|

FY |

Fiscal year |

|

IJM |

International Justice Mission |

|

ILO |

International Labour Organization |

|

INL |

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs |

|

IOM |

International Organization for Migration |

|

SPSD |

Standardized Program Structure and Definitions |

|

The Act |

Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 |

|

TIP Office |

Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

|

UNODC |

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

USAID |

United States Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2025

Congressional Committees

Armed conflict increases the risk that men, women, and children—particularly those who are displaced—will fall prey to human traffickers while simultaneously making the risks of human trafficking more difficult to combat. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 resulted in the internal displacement of nearly 17 million people within the country. In addition, almost 7 million people had fled Ukraine to other countries as of October 2024, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

In the 5-year period covering fiscal years 2020 through 2024, the U.S. government appropriated $524.8 million for activities to combat trafficking in persons internationally. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. government also appropriated funds in supplemental appropriations aimed at assisting Ukraine and other countries adversely affected by armed conflict in that country for anti-trafficking assistance.[1]

“Human trafficking” and “trafficking in persons” are often used interchangeably to refer to a variety of criminal activities. According to the Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report, the United States recognizes two primary forms of trafficking in persons: forced labor and sex trafficking. The report defines forced labor, sometimes referred to as labor trafficking, as encompassing the range of activities involved when a person uses force, fraud, or coercion to exploit the labor or services of another person. It defines sex trafficking as encompassing the range of activities involved when a trafficker uses force, fraud, or coercion to compel another person to engage in a commercial sex act or causes a child to engage in a commercial sex act. The report also states that in any case where a child under the age of 18 is used for a commercial sex act, it is considered sex trafficking regardless of whether force, fraud, or coercion were used. The movement of a person is not required for forced labor or sex trafficking.[2] We refer to these terms as “trafficking” throughout this report. Similarly, we refer to efforts to combat or counter trafficking as “anti-trafficking” throughout this report.

Trafficking takes place in every region of the world, and its ramifications include:

· gravely damaging its victims both physically and emotionally,

· undermining government authority,

· fueling organized crime, and

· imposing both social and public health costs.

In 2022, United Nations (UN) agencies estimated that 27.6 million people globally were subject to forced labor at any given time, including 6.3 million exploited for commercial sex.[3] In 2024, UNODC found that among officially reported victims, about 40 percent were male and 60 percent were female. About 38 percent of victims were children. However, given the hidden nature of trafficking crimes, officially reported data on the number of identified victims of trafficking from around the world only capture a portion of the estimated totals of all victims of trafficking.[4]

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for GAO to conduct oversight, including audits and investigations, of amounts appropriated in response to the war-related situation in Ukraine.[5] This report:

1. Describes the funding amounts that State and USAID have provided for anti-trafficking efforts in selected countries affected by conflict, including Ukraine, and the projects supported by these funds;[6]

2. Evaluates the extent to which these agencies monitor and report results of these projects and describes how these agencies adapted selected anti-trafficking projects to respond to implementation challenges cause by armed conflict; and

3. Discusses challenges in implementing anti-trafficking projects in selected conflict-affected countries as well as opportunities to address challenges identified by stakeholders.

To describe funding amounts that State and USAID have provided for anti-trafficking efforts in selected countries affected by conflict and the projects supported by these funding amounts, we reviewed State and USAID allocation and obligation funding data for anti-trafficking projects.[7]

To identify countries experiencing armed conflict, we used State’s definition for armed conflict and data from the World Bank and other sources. We also identified countries experiencing substantial challenges from conflict in neighboring countries, including the arrival of large numbers of refugees, as documented by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[8] We analyzed allocation funding data from State’s Office of Foreign Assistance and bilateral and regional award funding data from State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP Office) to identify countries that are both adversely affected by conflict and recipients of substantial U.S. anti-trafficking assistance.

Using that information, we selected Ukraine and Ethiopia for further examination, considering geographic diversity and the types of armed conflict occurring in the countries. We also selected two of Ukraine’s neighboring countries, Moldova and Romania, for further examination because these countries received anti-trafficking funding from State’s TIP Office, had received refugees from Ukraine, and the 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report described trafficking issues related to the conflict in Ukraine in both countries.

In these four selected countries, State and USAID identified 22 anti-trafficking projects that were active at any point from October 1, 2019 (the start of fiscal year (FY) 2020), through March 31, 2024 (the mid-point of FY 2024). From those 22 projects we selected 11 for further review, focusing on those that addressed trafficking problems generated or exacerbated by conflict. We also considered the projects’ implementing partners—such as nongovernmental organizations and international organizations—award amounts, and populations or issues the projects intended to address to ensure we reviewed a diverse selection of projects.

To evaluate the extent to which State and USAID had monitored and reported results of their anti-trafficking projects, we assessed State and USAID documentation, including agency monitoring and evaluation policies, grantee reporting for the 11 selected projects, and documentation of agency oversight and follow-up efforts.[9] We used agency criteria to evaluate whether State and USAID had established general and project-specific indicators and targets for each of the selected projects. We discussed instances where the agency or implementing partner had not established targets for project indicators with agency officials. To describe how State and USAID adapted the selected anti-trafficking projects to address implementation challenges caused by armed conflict, we reviewed project documentation and interviewed agency and implementing partner officials.

To identify the implementation challenges and possible opportunities to mitigate those challenges in implementing anti-trafficking projects in conflict-affected countries, we convened eight discussion groups with 47 total officials from State, USAID, implementing partner organizations, and relevant civil society organizations in Washington, D.C., and the selected countries. From December 2024 through March 2025, we conducted in-person meetings with the discussion groups in the U.S., Moldova, and Romania, and virtual meetings with the groups in Ukraine and Ethiopia. The views participants expressed during the meetings are not generalizable to all agency officials and implementing partners of U.S. programs.

We asked discussion group participants to identify (1) challenges of implementing anti-trafficking projects in conflict-affected countries and (2) possible actions to address those challenges. We conducted the discussion groups using the nominal group technique. Specifically, participants offered ideas as brief phrases or statements in response to our two questions. We asked for one idea from one group participant at a time and listed participants’ ideas so the responses were visible to the entire group. Group participants then discussed each idea in turn for clarification and examples. This process resulted in a list of challenges to implementation and a list of possible actions to strengthen anti-trafficking efforts for each of the eight discussion groups. We used the resulting lists from the discussion groups to develop a content coding structure. Two analysts reviewed the qualitative data independently and applied the coding structure to identify common themes among the challenges and possible actions that the discussion groups identified. When the two analysts reached different conclusions about how to apply the coding structure to the data, they met to reconcile those differences.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000

In 2000, Congress enacted the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (the Act) and has reauthorized it several times, most recently in 2023.[10] As amended, the Act provides a framework for U.S. anti-trafficking efforts. The Act:

· addresses the prevention of trafficking, protection of victims, and prosecution of traffickers;[11]

· defines “severe” forms of trafficking;[12]

· sets minimum standards for assessing foreign government efforts toward eliminating such forms of trafficking;[13]

· requires State to report each year on the extent that foreign governments meet the minimum standards;[14] and

· authorizes the President to provide assistance to foreign countries for programs, projects, and activities designed to meet the standards.[15]

State and USAID Roles and Responsibilities

State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP Office), established pursuant to the Act, is responsible for bilateral and multilateral diplomacy, targeted foreign assistance, and public engagement on trafficking in persons.[16] The TIP Office also prepares and issues the annual Trafficking in Persons Report to Congress, which includes the TIP Office’s assessment of the anti-trafficking efforts of 188 countries and territories, including the United States. The annual report guides State’s engagement with foreign governments and multilateral organizations on human trafficking. Additionally, the TIP Office funded projects to strengthen foreign governments’ ability to prevent human trafficking, protect victims, and prosecute traffickers. State officials said in August 2025 that following State’s reorganization, the TIP Office would focus on meeting its statutory report-writing function. As of September 2025, some of State’s anti-trafficking programming remained ongoing, according to State’s website listing the TIP Office’s projects.

The TIP Office also works with other State entities such as the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration and the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) to coordinate their anti-trafficking efforts.[17] In addition, the TIP Office worked with other agencies such as USAID and the Department of Labor, UN agencies, and other multilateral organizations to prevent and combat human trafficking in the United States and abroad.[18]

At the start of our review in February 2024, USAID administered projects to address trafficking in persons and integrated such projects into broader development efforts. USAID largely managed these projects at the country level, with project goals that aimed to address trafficking challenges specific to a country or region. USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Governance in Washington, D.C., was responsible for coordination and oversight of USAID’s anti-trafficking efforts.

After we began our review, the President issued Executive Order 14169, “Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid” on January 20, 2025.[19] The order called for department and agency heads with responsibility for U.S. foreign development assistance programs to immediately pause new obligations and disbursements of development assistance funds to foreign countries and implementing nongovernmental organizations, international organizations, and contractors pending reviews of such programs for programmatic efficiency and consistency with U.S. foreign policy. In March 2025, USAID and State notified Congress of their intent to undertake a reorganization of foreign assistance programming that would involve realigning certain USAID functions to State by July 1, 2025, and discontinuing the remaining USAID functions. State began the reorganization in April 2025. In July 2025, the Secretary of State announced that USAID had officially ceased to provide foreign development assistance.

Armed Conflict Elevates Trafficking Risks

Armed conflict, whether between two or more countries or between government military forces and other armed groups within a country, can directly and indirectly heighten trafficking risks.[20] Conflict can directly increase the amount of human trafficking when armed groups engage in trafficking. For example, armed groups, including government forces and rebel groups, may coerce residents of conflict areas to perform forced labor in support of military operations or in income-generating activities, such as mining or agriculture. Conflict can also indirectly increase the amount of trafficking as criminal groups or individuals take advantage of potential victims’ increased vulnerability.

Several factors contribute to this increased vulnerability to trafficking, including:

· Deterioration in the rule of law. Safeguards and protections available to individuals in peacetime decrease as impunity among traffickers increases during armed conflict.

· Increased humanitarian assistance needs. Armed conflict results in the loss of livelihoods and the impairment or even elimination of access to essential services and goods.

· Social fragmentation. Community and family support systems break down in the context of armed conflict.

· Forced displacement. UNHCR estimated that more than 123 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced at the end of 2024 due to conflict, violence, human rights violations, and other factors.

Once they reach their destination, migrants, including internally displaced persons and refugees, may remain vulnerable to trafficking due to multiple factors, including language and cultural barriers, lack of support networks, economic and social challenges, and lack of access to basic services. In 2022, UN agencies found forced labor to be three times as prevalent among adult migrant workers as among non-migrants.[21]

|

Defining Terms: Migrants, Internally Displaced Persons, and Refugees Migrants: According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), “migrant” is an umbrella term, not precisely defined under international law, that refers to a person who moves away from his or her usual place of residence, whether within a country or across an international border, whether temporarily or permanently, regardless of legal status. The term can include Internally Displaced Persons and Refugees: Internally Displaced Persons: According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the U.N. refugee agency, an internally displaced person is a person who has been forced or obliged to leave their home, as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, human rights violations, or natural or man-made disasters, but has not crossed into another country. Though remaining within their own countries, such persons may experience economic hardship and social isolation. Refugees: UNHCR defines refugees as people who have been forced to flee their country and seek safety in another country because of feared persecution as a result of who they are, what they believe in or say, or because of armed conflict, violence or serious public disorder. Refugees are entitled to certain legal protections but may experience economic deprivation and social isolation nonetheless. |

Source: U.N. Organizations. | GAO‑26‑107406

Conflict and Trafficking in Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in nearly 17 million residents becoming internally displaced in 2022 (about 40 percent of the country’s population). As of April 2025, more than 3.75 million remained internally displaced in Ukraine, according to UNHCR. Further, according to the UNODC, the invasion resulted in about 6.75 million people fleeing Ukraine by October 2024. Those fleeing Ukraine generally crossed land borders into neighboring countries, including Moldova and Romania.

Human Rights Watch reported more than 470,000 people crossing from Ukraine into Moldova in the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion, while Government of Romania estimated that nearly 500,000 people sought refuge in Romania during the same period. In May 2025, UNHCR reported that Moldova was still hosting more than 131,000 refugees from Ukraine while Romania was still hosting more than 186,000. In contrast, UNCHR estimated that both countries had each been hosting fewer than 20 refugees from Ukraine in 2021, prior to the 2022 invasion (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Internally Displaced Persons Within Ukraine as of April 2025 and Refugees from Ukraine in Moldova and Romania as of May 2025

In the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion, international aid organizations warned that there could be a substantial surge in trafficking in Ukraine and among Ukrainians seeking refuge in other countries. Though data is limited, there does not appear to have been a surge of the magnitude that some had feared.[22] Still, a 2025 UNODC analysis suggests that some increase in trafficking has occurred.[23] Other UN agencies have also expressed concerns about a possible delayed surge as time passes, people remain displaced, savings run out, and host country assistance declines.

State’s 2024 and 2025 Trafficking in Persons Reports for all three countries highlighted sex trafficking and forced labor issues, including online recruitment and elevated risk levels among children, members of minority groups, and, in Ukraine, people living in Russian-occupied parts of the country. The reports also noted the strain that Russia’s invasion had placed on anti-trafficking efforts in all three countries. For example, because of the conflict, Ukraine has experienced reduced capacity in its law enforcement and provision of services for victims of trafficking.

Conflict and Trafficking in Ethiopia

Ethiopia faces overlapping humanitarian crises driven by internal ethnic and political conflict and conflict in neighboring countries. Following decades of regional conflict, a civil war broke out in Ethiopia in 2020. This conflict pitted the Ethiopian federal government, supported by the bordering country of Eritrea and forces from Ethiopia’s Amhara regional state, against forces from the regional state of Tigray. While armed conflict between the federal government and forces from Tigray officially ended in late 2022, other conflict has continued in the country, with the government facing ongoing, ethnically-based insurgencies in both the Amhara and Oromia regions. In June 2025, UNHCR estimated that there were more than 1.9 million internally displaced persons in Ethiopia.[24]

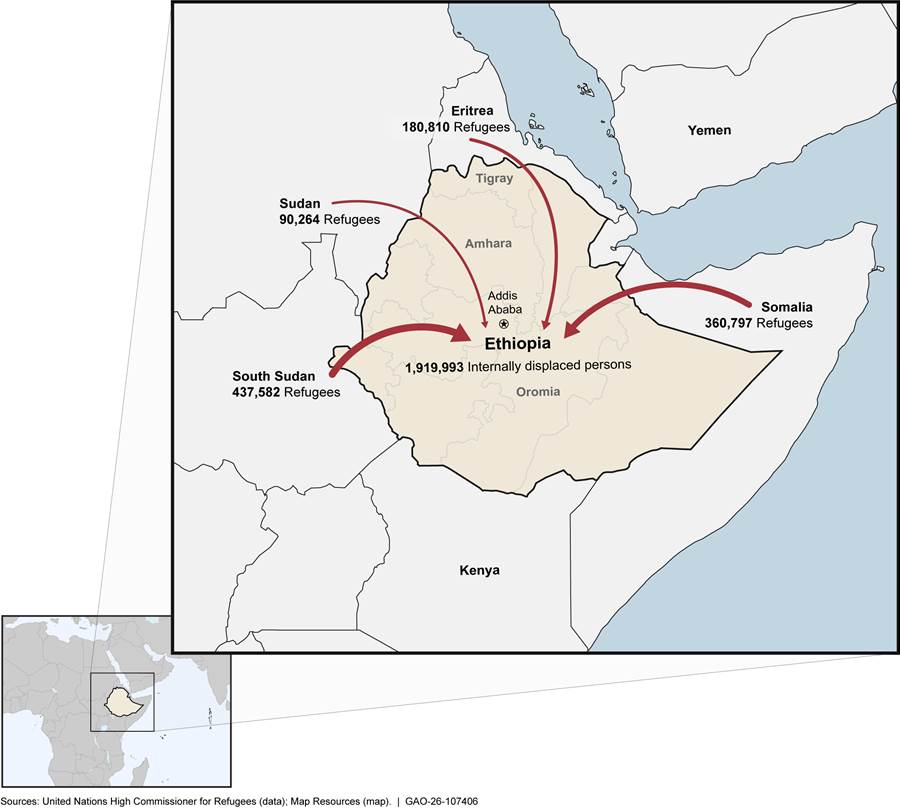

In addition to the ongoing conflict within its own borders, Ethiopia hosts almost 1.1 million refugees from other countries—primarily the neighboring countries of Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan, according to UNHCR. All four of those countries face conflict or other challenges that fuel the displacement. (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Internally Displaced Persons and Refugees from Neighboring Countries in Ethiopia as of June 2025

State’s 2024 and 2025 Trafficking in Persons Reports for Ethiopia highlighted that traffickers exploit domestic and foreign victims within the country. Among other things, State noted (1) the exploitation of women and girls in domestic servitude and sex trafficking, and (2) the exploitation of men and boys for forced labor in several sectors, such as agriculture and construction. The reports stated that traffickers may promise urban work opportunities to exploit children from rural areas, whose parents—facing extreme economic pressure—may encourage them to work.

State observed that the millions of persons displaced within Ethiopia are increasingly vulnerable to trafficking due to a lack of access to justice, education, economic opportunity, and basic needs, such as food, water, and health services. Refugees from other countries in Ethiopia face similar challenges, including lack of economic opportunity and access to basic needs, which leaves them more vulnerable to trafficking.

State and USAID Funded and Implemented Anti-Trafficking Projects, Including in Countries Affected by Armed Conflict

For fiscal years 2020 through 2024, State and USAID together obligated a total of about $437 million for anti-trafficking projects around the world, including at least $38.2 million in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia.[25] Funding for such efforts was limited in fiscal year 2025 during the administration’s review of foreign assistance.[26] For fiscal year 2025, as of August, State had not allocated any new funding and had de-obligated about $1.4 million for anti-trafficking projects. During the same period, USAID allocated less than $1 million, obligated about $1 million, and de-obligated about $1.1 million for anti-trafficking projects. We reviewed 11 anti-trafficking projects that were active during the time of our review in the four selected countries, totaling about $50 million. These projects address issues created or exacerbated by conflict in those countries.

Anti-Trafficking Allocations and Obligations, Worldwide and in Selected Countries

From FY 2020 through FY 2024, State and USAID allocated about $461 million for anti-trafficking projects.[27] State’s TIP Office reported a total allocation of $345 million for these years, with annual amounts increasing from $61 million in fiscal year 2020 to $76 million in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. State also allocated about $16.7 million for anti-trafficking projects managed by INL and State’s regional bureaus from 2020 through 2024. However, as of August 2025, State officials said they had not yet completed its allocation process for FY 2025 and so had not allocated any funding for the TIP Office in that fiscal year.

USAID allocated nearly $99 million from FY 2020 through FY 2024, with annual amounts ranging from $9.2 million to $27.7 million. As of June 2025, USAID had allocated about $700,000 for FY 2025 (see table 1).

Table 1: Department of State and USAID Allocations by Fiscal Year of Appropriation for Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects Worldwide, Fiscal Years 2020–2025Q2, as of August 2025

Dollars in millions

|

Agency |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

Total |

|

State TIP Office |

61.0 |

66.0 |

66.0 |

76.0 |

76.0 |

0.0a |

345.0 |

|

Other State |

2.5 |

3.4 |

6.1 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

0.0a |

16.7 |

|

USAID |

24.8 |

17.7 |

9.2 |

27.7 |

19.5 |

0.7 |

99.7 |

|

Totals |

88.3 |

87.1 |

81.3 |

106.2 |

97.8 |

0.7 |

461.4 |

Legend: TIP Office = State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development

Source: Department of State and USAID data. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. Data for fiscal year 2025 includes only the first two quarters. “Other State” and “USAID” amounts may include funding from Ukraine supplementals.

Data does not include allocations for anti-trafficking in persons activities that are not coded with State’s Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) trafficking in persons code (PS.5). Data also does not include funding that State identified as having multiple SPSD codes.

aAccording to State officials, as of August 2025, State had not completed the allocations process for fiscal year 2025. As such, the amount allocated for State’s anti-trafficking in persons projects is zero as of August 2025.

From FY 2020 through the first two quarters of FY 2025, State obligated about $337 million for anti-trafficking projects. State’s TIP Office oversaw about 93 percent of State’s total obligations for anti-trafficking projects during this period. USAID obligated about $99 million during the same period. For fiscal year 2025, as of August 2025, State had not allocated any new funding and had de-obligated about $1.4 million for anti-trafficking projects. During the same period, USAID allocated less than $1 million, obligated about $1 million, and de-obligated about $1.1 million for anti-trafficking projects (see table 2).

Table 2: Department of State and USAID Obligation Transactions for Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects, Fiscal Years 2020–2025, as of August 2025

Dollars in millions; amounts shown by the fiscal year in which the agencies obligated funding, not the year in which they allocated funding

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

Total |

|

State TIP Office |

44.4 |

58.5 |

66.1 |

68.6 |

77.8 |

-1.3 |

314.1 |

|

State INL |

5.9 |

5.2 |

2.2 |

3.9 |

3.1 |

0.0a |

20.3 |

|

Other State |

0.0 |

1.6 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

2.4 |

|

Subtotal - State |

5.9 |

65.3 |

68.3 |

73.0 |

81.2 |

-1.4 |

336.5 |

|

USAID |

25.1 |

17.7 |

9.2 |

27.7 |

19.5 |

-0.1b |

99.0 |

|

Total |

75.4 |

83.0 |

77.5 |

100.7 |

100.7 |

-1.5 |

435.5 |

Legend: INL = State Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs; TIP Office = State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development

Source: Department of State and USAID data. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. Data for fiscal year 2025 includes only the first two quarters.

An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability of the government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received. An agency incurs an obligation, for example, when it places an order, signs a contract, awards a grant or purchases a service. Negative numbers indicate the agency de-obligated funding.

State officials said that State generally undertakes obligation transactions for projects in the fiscal year following the allocation of funds. Data are shown by the fiscal year in which State obligated the funding, not the year in which it allocated the funding.

Although State allocated $78.3 million for anti-trafficking in persons projects in fiscal year 2024, State officials said that the TIP Office has been prevented from obligating fiscal year 2024 funds during fiscal year 2025. While not finalized as of August 2025, officials said that they expected State would de-obligate additional prior year funding during fiscal year 2025.

According to agency officials, funding for anti-trafficking activities can come from multiple funding accounts that provide funding for other activities. Data presented in the table includes obligations with State’s Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) code for trafficking in persons, PS.5, and represent funds from multiple funding accounts.

Data does not include obligation transactions for anti-trafficking in persons activities that are not coded with the PS.5 SPSD code for trafficking in persons. Data also does not include funding that State identified as having multiple SPSD codes. In addition, for State’s TIP Office 2020 data, officials said that State coded funding at the general Peace and Security category, rather than the more specific PS.5 category for trafficking in persons.

aINL de-obligated about $40,000 from the anti-trafficking SPSD code in 2025.

bData reflects USAID obligations of about $1 million and de-obligations of about $1.1 millions from the anti-trafficking SPSD code.

Of the $435.5 million obligated from FY 2020 through the first two quarters of FY 2025, State obligated about $24.5 million for projects in Ukraine, Romania, Moldova, and Ethiopia. USAID obligated an additional $13.7 million over this period for relevant assistance to Ukraine, bringing the total for both agencies for the period to about $38.2 million. USAID did not obligate any funds for projects in Ethiopia, Moldova, or Romania (see table 3).

Table 3: Department of State and USAID Obligation Transactions for Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia, Fiscal Years 2020–2025Q2

Dollars in millions; amounts shown by the fiscal year in which the agencies obligated funding, not the year in which they allocated funding

|

Country (Agency) |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

Total |

|

Ukraine (State) |

N/A |

0.3 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

2.8 |

|

Moldova (State) |

0.1 |

0.0a |

0.5 |

2.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

2.6 |

|

Romania (State) |

0.8 |

0.0 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

9.5b |

0.0 |

12.6 |

|

Ethiopia (State) |

2.5 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

3.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

6.5 |

|

Subtotal - State |

3.3 |

0.3 |

2.6 |

7.1 |

11.0 |

0.0 |

24.5 |

|

Ukraine (USAID) |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

10.0 |

0.0 |

1.0c |

13.7 |

|

Total |

4.2 |

1.2 |

3.5 |

17.1 |

11.0 |

1.0 |

38.2 |

Legend: N/A = Not available; USAID = United States Agency for International Development

Source: Department of State and USAID data. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. Data for fiscal year 2025 includes only the first two quarters.

An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability of the government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received. An agency incurs an obligation, for example, when it places an order, signs a contract, awards a grant or purchases a service.

State officials said that State generally undertakes obligation transactions for projects in the fiscal year following the allocation of funds. Data are shown by the fiscal year in which State obligated the funding, not the year in which it allocated the funding.

According to agency officials, funding for anti-trafficking activities can come from multiple funding accounts that provide funding for other activities. As a result, data presented in the table includes obligations with State’s Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) code for trafficking in persons, PS.5, and represent funds from multiple funding accounts.

Data does not include obligation transactions for anti-trafficking in persons activities that are not coded with the PS.5 SPSD code for trafficking in persons. Data also does not include funding that State identified as having multiple SPSD codes. For State’s TIP Office 2020 data, officials said that State coded funding at the general Peace and Security category, rather than the more specific category for trafficking in persons.

aIn fiscal year 2021, State obligated $1,000 to a project in Moldova.

bThe 2024 Romania total represents obligation for a Child Protection Compact, using fiscal year 2023 funds, that State announced at the end of fiscal year 2024. Such Compacts are multi-year plans developed by the U.S. and a foreign partner government directed at strengthening capacity to prosecute child traffickers, provide care for victimized children, and prevent child trafficking in all its forms.

cAccording to a USAID official, this amount was obligated pursuant to a bilateral agreement with the government of Ukraine but, as of June 2025, had not been awarded to a specific project. The official told us these funds will likely be de-obligated.

State and USAID Anti-Trafficking Projects in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia

Agencies generally do not aim to conduct anti-trafficking in countries affected by armed conflict, but do sometimes undertake such projects, as they have done in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia. State officials said anti-trafficking projects are designed to address country-specific challenges identified in its annual trafficking in persons report as well as other factors, including the host country’s political will and capacity to address trafficking-related challenges. As such, they explained that the TIP Office generally provided assistance where there was a willing government partner and relative stability. Further, State officials said they generally do not intend to conduct anti-trafficking projects in countries where armed conflict occurs. Nonetheless, sometimes the agencies do undertake anti-trafficking projects in countries affected by armed conflict such as Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia where conditions are stable enough to allow implementing partners to operate and for State to provide monitoring and oversight, according to State officials.

Selected Anti-Trafficking Projects in Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania

The seven State and USAID anti-trafficking projects in Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania we reviewed were ongoing in the second quarter of fiscal year 2024 and addressed issues created or exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For example, one regional State program was initiated in August 2023 to help protect refugees from Ukraine and other vulnerable populations from trafficking. Four of the seven projects were initiated after the 2022 Russian invasion, while the other three were extended or received additional funds to continue operating after the invasion with adjustments to address the invasion’s impact on trafficking risk in these countries. The awarded amount for these seven projects totaled about $32.4 million. Table 4 provides summary information on these projects.

Table 4: Selected Department of State and USAID Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects in Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania

Dollars in millions

|

Bureau or Office |

Implementing partner |

Project Title Project Description |

Award Amount |

|

Ukraine |

|||

|

USAID Europe Bureau |

IOM |

Countering Trafficking in Persons and Ensuring Assistance to Vulnerable Groups in Ukrainea Increase awareness, assist victim rehabilitation, and improve coordination and information on trafficking in Ukraine |

$24.0 |

|

State TIP Office |

IOM |

Addressing Trafficking in Persons and Related Risks in the Ukraine Emergency Responseb Provide assistance to victims of or those vulnerable to trafficking due to the Russian invasion, such as displaced persons |

$2.0 |

|

Moldova |

|||

|

State TIP Office |

IOM |

Strengthening National Efforts to Prevent Trafficking in Persons and Rehabilitate Victims of Trafficking in the Republic of Moldovaa Increase awareness, improve services for victims, strengthen legal framework, and support rehabilitation of victims |

$1.4 |

|

IOM |

Reducing Community-Level Vulnerabilities to TIP in Moldovab Improve local actors’ prevention capacities and increase victim participation in investigations and judicial proceedings |

$1.0 |

|

|

State INL |

IOM |

Addressing Emerging Threats Related to Trafficking in

Persons in Strengthen law enforcement capacity, particularly in addressing the threat of online trafficking and connected crimes |

$1.0 |

|

Romania |

|||

|

State TIP Office |

IJM |

Strengthening Proactive Criminal Justice Response to Trafficking in Personsa Strengthen criminal justice system capacity and quality of social services to victims, train community responders |

$1.5 |

|

IJM |

Regional Response to Trafficking in Persons within the Ukraine Crisisb, c Increase identification of trafficking victims, build capacity of service providers, and improve coordination of investigations |

$1.5 |

|

|

Total |

|

$32.4 |

|

Legend: IJM = International Justice Mission; INL = State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs; IOM = International Organization for Migration; State TIP Office = State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development

Source: Department of State and USAID data. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. All projects above were ongoing in the second quarter of fiscal year 2024.

aProject extended or adjusted its activities in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

bProject initiated after or in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

cProject also provides assistance to Bulgaria.

Selected Anti-Trafficking Projects in Ethiopia

The four anti-trafficking projects we reviewed in Ethiopia that were ongoing as of March 2024 had awarded amounts totaling about $17.5 million. While none of these projects were initiated specifically to address trafficking issues created by conflict, conflict has exacerbated the problems that they address: trafficking among vulnerable populations (such as child domestic workers, internal and transnational migrants, and disabled persons), weaknesses in protecting victims, and difficulties in prosecuting traffickers. For example, one project aimed to strengthen the National Referral Mechanism, a framework for identifying victims of trafficking and improving services for victims of trafficking throughout the country, including in regions that have endured internal conflict. Table 5 provides summary information on these four projects.

Dollars in millions

|

Implementing partner |

Project Title Project Description |

Award Amount |

|

Freedom Fund |

Reducing the Prevalence of Domestic Servitude in Ethiopia Investigate and reduce the prevalence and causes of domestic servitude among women and children |

$11.0 |

|

International Organization for Migration |

Improving the Protection of Victims of Internal and Transnational Trafficking in Ethiopia Strengthen national legal mechanisms and improve services for victims |

$1.9 |

|

U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime |

Enhancing Effective and Victim-Centered Criminal Justice Responses to Trafficking in Persons in Ethiopiaa Strengthen the capacity of victim protection and criminal justice entities |

$1.5 |

|

Population Council |

Forced Begging Among People with Disabilities in Ethiopia Research, design, and implement interventions to combat forced begging, then assess results |

$3.1 |

|

Total |

|

$17.5 |

Legend: TIP Office = State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons

Source: Department of State data. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: Totals may not add up due to rounding. Some elements of each project, such as activities or timelines, had to be adjusted due to internal conflict in Ethiopia. All projects were ongoing in the second quarter of fiscal year 2024.

aProject was terminated in February 2025 as part of the 2025 foreign assistance review. On January 20, 2025, the President issued an Executive Order pausing foreign development assistance for an assessment of programmatic efficiencies and consistency with United States foreign policy. Exec. Order No. 14169, Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid, 90 Fed. Reg. 8619 (Jan. 30, 2025). The project had been scheduled to be completed in June 2025.

State and USAID Generally Monitored and Reported Results and Adjusted Selected Projects for Conflict-Related Challenges

State and USAID generally met their internal requirements for monitoring and reporting for the 11 selected projects we reviewed. To do so, the agencies used several tools to monitor the performance and report project-specific and agency-wide results of their anti-trafficking projects. These tools included monitoring plans with indicators to assess progress toward targets as well as periodic and final progress reports.[28] Agencies also worked with implementing partners to adjust project elements to respond to challenges associated with conflict were identified. For the three selected projects that had reached their expected end date (two State TIP Office and one USAID), we found that the projects generally achieved established targets.

State and USAID Generally Established Required Frameworks for Monitoring and Reporting Results of Selected Projects

At the time of our review, State and USAID had agency-wide criteria on monitoring and reporting results of foreign assistance projects. Both agencies also had project-specific requirements. These requirements included monitoring and reporting at set intervals on projects’ progress and final results compared to targets established for performance indicators. These performance indicators—according to the policies of both agencies—monitor progress and measure actual results compared to expected results. Targets were required to be set for each performance indicator to establish the expected results over the course of each performance period.

More specifically, State had agency-wide guidance on monitoring and reporting the results of its foreign assistance projects. The agency’s Federal Assistance Directive established agency-wide internal guidance, policies, and procedures for State bureaus and offices administering federal financial assistance. The Federal Assistance Directive instructs State’s bureaus and offices to develop monitoring plans, conduct monitoring activities, and report on progress and performance. State generally addressed these requirements by setting targets for both broad, agency-wide indicators—called Common Performance Indicators (CPIs)—and project-specific performance indicators, and by tracking progress toward those targets in monitoring reports.[29]

According to TIP officials, TIP Office program managers work with implementing partners during project development to identify appropriate CPIs from a master list of possible indicators. They then use the CPIs to report on performance for the entire office by aggregating results for all projects.[30] In addition, each of the selected State projects had a signed award containing project-specific monitoring and evaluation criteria. These criteria included requirements for quarterly reporting of project progress through indicator tracking tables and narrative reports.[31] The signed awards also required grantees to submit a final report upon project completion that should describe how the goals and objectives of the project were met or not. Table 6 provides examples of State’s agency-wide and project-specific performance indicators for its anti-trafficking efforts.

Table 6: Examples of Department of State Performance Indicators for Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects

|

Examples of Common Performance Indicators |

Examples of project-specific performance indicators |

|

· Number of trainings conducted · Number of individuals trained · Number of unique trafficking victims receiving one or more type of service |

· Number of consultation meetings with local community leaders organized · Percent increase in number of citizens and refugees who access counseling services for safe migration or trafficking in persons prevention via anti-trafficking hotline after the launch of the awareness raising campaign · Number of Ukrainian refugees contacted for follow-up after self-reporting being at risk of trafficking |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of State documents. | GAO‑26‑107406

Like State, USAID also had agency-wide criteria on monitoring and reporting results. USAID’s Automated Directives System (ADS) outlined policies and procedures that guided the agency’s programs and operations. The ADS directed USAID offices to develop monitoring, evaluation, and learning plans and report on performance progress.[32]

In addition to agency-wide criteria, the signed award for the selected USAID project contained project-specific monitoring and evaluation requirements. For example, the project required grantees to submit semiannual reports, performance monitoring and evaluation plans, and a final report. Table 7 provides examples of USAID’s agency-wide and project-specific performance indicators for the selected anti-trafficking project.

Table 7: Examples of U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Anti-Trafficking in Persons Performance Indicators

|

Examples of standard performance indicators |

Examples of project-specific performance indicators |

|

· Number of service providers that receive training, technical assistance, or capacity building in victim-centered and trauma-informed services for victims of human trafficking · Number of victims of human trafficking receiving services (medical, repatriation, legal, transportation, etc.) · Number of survivors of human trafficking who have gained sustainable livelihoods through State and USAID foreign assistance |

· Percent of covered regions that have institutionalized the developed anti-trafficking educational module · Percent increase in the number of calls due to targeted and nationwide prevention efforts · Number of people covered with hotline services · Number of protection beneficiaries (victims of exploitation, gender-based violence survivors, people most at risk of human trafficking) receiving services (medical, repatriation, transportation, etc.) |

Source: GAO analysis of USAID documents. | GAO‑26‑107406

Both agencies also required the establishment of targets for each agency-wide and project-specific indicator that we found they had generally done. For example, State’s Project and Program Design, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy requires targets be set to indicate the expected change over the course of each period of performance. Offices such as the TIP Office must develop a monitoring plan that documents a baseline, milestones, and target for each indicator. Our review of monitoring documents indicated that eight of 11 selected projects had established targets for all indicators. For the remaining three projects, agencies had established targets for 142 of 145 combined agency-wide and project specific indicators.

Table 8 summarizes the status of agency efforts to design performance indicators and set related targets for selected anti-trafficking projects.

Table 8: Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Project Monitoring and Reporting Requirements for Selected Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects, as of May 2025

|

U.S. Agency |

Project Title |

Monitoring and reporting requirements |

||

|

Monitored and reported progress |

Set indicators |

Set targets for all indicators |

||

|

Ukraine |

||||

|

USAID |

Countering Trafficking in Persons in Ukrainea |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

State TIP Office |

Addressing Trafficking in Persons and Related Risks in the Ukraine Emergency Response |

Yes |

Yes |

Yesb |

|

Moldova |

||||

|

State TIP Office |

Strengthening National Efforts to Prevent Trafficking in Persons and Rehabilitate Victims of Trafficking in the Republic of Moldovaa |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Reducing Community-Level Vulnerabilities to TIP in Moldova |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

|

State INL |

Addressing Emerging Threats Related to Trafficking in Persons in the Republic of Moldova |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Romania |

||||

|

State TIP Office |

Strengthening Proactive Criminal Justice Response to Trafficking in Persons in Romaniaa |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Regional Response to Trafficking in Persons within the Ukraine Crisis |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Ethiopia |

||||

|

State TIP Office |

Reducing the Prevalence of Domestic Servitude in Ethiopia |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Improving the Protection of Victims of Internal and Transnational Trafficking in Ethiopia |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Enhancing Effective and Victim-Centered Criminal Justice responses to Trafficking in Persons in Ethiopiac |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Forced Begging Among People with Disabilities in Ethiopia |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Legend: State TIP Office = State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons; State INL = State’s Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement,

Source: Department of State and USAID documentation. | GAO‑26‑107406

Notes: State’s TIP Office, INL, and USAID’s projects used different documents to monitor results of indicators and targets. The TIP Office tracked progress of project indicators and results in Quarterly reports, Results Monitoring Plans or Logical Frameworks, INL tracked progress in quarterly reports, and USAID tracked progress in Monitoring Evaluation and Learning Plans.

aThese projects have reached their planned end date as of May 1, 2025.

bState officials said that in May 2025, State’s TIP Office and International Organization for Migration in Ukraine set targets for the two performance indicators that had been missing.

cThis project was terminated in February 2025 as part of the 2025 foreign assistance review. On January 20, 2025, the President issued an Executive Order pausing foreign development assistance for an assessment of programmatic efficiencies and consistency with United States foreign policy. Exec. Order No. 14169, Reevaluating and Realigning United State Foreign Aid, 90 Fed. Reg. 8619 (Jan. 30, 2025). The project had been scheduled to be completed in June 2025.

Following our inquiries, State officials addressed the missing targets we identified in the three selected projects in various ways.

· The TIP Office’s Ukraine project supporting the National Toll-free Migrant Advice and Counter-Trafficking Hotline had targets for 15 of its 17 agency-wide indicators. The two indicators without targets were to measure (1) the number of calls received and (2) the number of victims referred to services through that hotline. During our review, State officials said that the TIP Office and IOM Ukraine set targets for the two indicators that were missing targets. This occurred more than halfway through the project’s 4-year timeline. However, they noted that the implementing partner had been reporting on both of these indicators since the inception of the project even though there were no established indicator targets.

· As of March 2025, the TIP Office’s Moldova IOM project on reducing community-level vulnerabilities to trafficking, had targets for 22 of its 24 agency-wide indicators. Two indicators were without targets more than halfway through the project’s 3-year timeline. The project’s activities include trainings in anti-trafficking and migration-related issues for groups including Moldova’s Ministry of Labour and Social Protection. The two indicators without targets tracked how many people took action as a result of those trainings. Actions could include such things as contacting a community leader or signing an anti-trafficking petition. As of July 2025, TIP Office officials said that they and the implementing partner agreed to no longer include those indicators because of the difficulty in measuring the actions taken as a result of the training activities.

· As of March 2025, the TIP Office’s UNODC project in Ethiopia on enhancing a victim-centered criminal justice response to trafficking in persons, had project-specific targets for 33 of its 34 indicators. One indicator did not have a target more than four years into the project and three months before the end of its timeline. The project’s activities included enhancing the Witness Protection Directorate in the country. The indicator without a target tracked developing and supporting legislation in Ethiopia related to the Witness Protection Directorate. State officials said that the implementing partner did not set a target for this indicator because it tracks the creation of a single product. Officials said that it therefore served as a milestone rather than a measurable target. In February 2025, State terminated the project as part of the foreign aid review.

State and USAID Worked with Implementing Partners to Adjust Elements of Selected Projects to Respond to Challenges from Armed Conflict

When armed conflicts broke out or evolved in ways that challenged planned projects, State and USAID worked with the implementing partners of the selected projects to adjust project activities, indicators, and timelines or provide additional funding.

Activities. State and USAID worked with implementing partners to adjust project activities when armed conflict challenged existing projects. For example, according to an implementing partner for a TIP Office project in Ethiopia, they adjusted activities related to police capacity building because the police were forced to focus on security problems and did not have resources to devote to trafficking. As a result, State worked with the implementing partner to refocus planned efforts for law enforcement training to target other criminal justice actors. In another example, in response to the refugee crisis in Moldova associated with the war in Ukraine, the TIP Office worked with an implementing partner to adjust the project’s activities to focus on raising awareness among refugees and migrants coming from Ukraine.

USAID project documentation demonstrated how the agency and its implementing partner adjusted project activities in Ukraine to better reflect the shifting environment that resulted from the conflict with Russia. For example, the implementing partner added awareness-raising activities to combat trafficking among newly internally displaced persons and other conflict-affected populations.

Indicators. State and USAID worked with implementing partners to adjust project performance indicators for project elements affected by armed conflict. For example, State officials and the implementing partner for a TIP Office project in Moldova worked together to adjust a project goal to respond to the refugee crisis caused by the armed conflict in Ukraine, according to project documentation. Because of this development, the implementing partner also adjusted some project indicators and targets. Additionally, USAID officials said that they adjusted project indicators and targets in response to the changing environment for anti-trafficking caused by the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Timeframes. In some instances where armed conflict challenged anti-trafficking projects, State and USAID worked with implementing partners to adjust timeframes for completing the project and associated activities. For example, according to an implementing partner for an anti-trafficking project in Ethiopia, conflict in the country caused project implementation to lag so the project timeline was extended a year. Similarly, the implementing partner for a TIP Office project in Moldova reported that the war in Ukraine and the associated refugee crisis overwhelmed their staff and Moldovan government, which delayed implementation of project activities. The implementing partner said that the TIP Office worked with the implementing partner to extend the timeframe to allow them to meet the project’s goals. According to project documents, USAID likewise extended the timeframe for its anti-trafficking project to respond to critical needs and emerging developments from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Additional funding. State and USAID sometimes provided additional funding to implementing partners to achieve envisioned project objectives when conflict presented challenges. According to an implementing partner operating a TIP Office project, the implementing partner was providing support in Addis Ababa to trafficking survivors from Tigray because the implementing partner would not return survivors to unsafe locations. However, lacking a budget for this support, they received additional funding from the TIP Office to meet the unforeseen expenses. As mentioned previously, when the TIP Office worked with the implementing partner in Moldova to adjust activities and timeframes for a project because of challenges from the war in Ukraine and the associated refugee crisis, the TIP Office also provided additional funding to support those changes to the project. USAID also provided additional funding for its anti-trafficking project in Ukraine in response to the ongoing war. According to project documents, USAID intended this additional funding to support efforts to provide assistance to victims of exploitation, gender-based violence survivors, and other vulnerable groups in addition victims of trafficking.

Three Completed Projects Generally Met Performance Targets

Of the 11 selected anti-trafficking projects we reviewed in depth, the three that had reached their end dates as of May 1, 2025, generally met performance targets.[33] First, State’s project Strengthening Proactive Criminal Justice Response to Trafficking in Persons in Romania, which ended in September 2024, met targets for 22 of their 23 performance indicators. For example, the project met its targets for the number of trainings conducted; people trained; times that trafficking-awareness materials were broadcast or published; and trafficking-related investigations, arrests, and prosecutions initiated as a result of the project’s activities or in coordination with the implementing partners, among others. The one target that was not met was a goal of 15 training recipients taking action—such as contacting a community leader or signing an anti-trafficking petition—as a result of provided training.

Second, the USAID project Countering Trafficking in Persons in Ukraine, which also ended in September 2024, met targets for nine of its 11 performance indicators. For example, the project met its targets for the number of service providers that received training, technical assistance, or capacity building in victim-centered and trauma informed services; the number of protection beneficiaries receiving services; and the number of people covered by trafficking hotline services. However, the project did not meet targets for two of its 11 indicators. These indicators set goals of (1) 500 victims of human trafficking receiving medical, repatriation, legal, transportation, or other services and (2) 70 survivors of human trafficking who have gained sustainable livelihoods through State and USAID foreign assistance. According to officials, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—which began after this project was initiated—presented obstacles to achieving these targets.

Third, State’s project Strengthening National Efforts to Prevent Trafficking in Persons and Rehabilitate Victims of Trafficking in the Republic of Moldova, which ended in January 2024, met 14 of its 15 project-specific performance indicators. For example, the project met its targets for the number of printed handouts distributed at border crossing points and number of individuals accessing a hotline per year. One target was not fully met, which aimed to identify at least 100 unique victims of trafficking annually in a region of Moldova, with at least 20 percent of those victims being migrants and refugees from Ukraine. However, the implementing partner succeeded in identifying 154 victims of trafficking, but only one case involved a Ukrainian citizen during the phase in which this target was active.

Stakeholders Identified Challenges and Opportunities to Strengthen Implementation of Anti-Trafficking Projects in Countries Affected by Armed Conflict

Discussion group participants identified implementation challenges and opportunities to strengthen U.S. anti-trafficking projects in conflict-affected countries. The 47 stakeholders in the eight discussion groups we held from December 2024 to March 2025 consisted of U.S. agency officials managing anti-trafficking projects, embassy officials, and representatives of organizations implementing projects in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia. We analyzed the participants’ responses for common themes. We identified nine challenges to project implementation and five opportunities to strengthen implementation (see table 9).

Table 9: Stakeholders Identified Challenges and Opportunities to Strengthen Implementation of Anti-Trafficking in Persons Projects in Conflict-Affected Countries, December 2024–March 2025

|

Challenges to Implementation |

Opportunities to Strengthen Implementation |

|

· Prioritization of humanitarian aid over anti-trafficking efforts · Increased vulnerabilities to trafficking in conflict-affected countries · Changing trafficking patterns in conflict-affected countries · Impaired prevention and awareness among vulnerable populations · Interrupted access to conduct protection activities · Limited program management flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances in conflict · Difficulties coordinating and partnering with local and international stakeholders · Limited local partner capacity to conduct anti-trafficking efforts · Corruption and evidence requirements for prosecuting trafficking cases |

· Continue U.S. policy emphasis on anti-trafficking efforts · Build local partner capacity through training, technology, and best practices · Allow implementing partners greater flexibility to adapt when conflict interrupts planned anti-trafficking activities · Facilitate coordination among international and local anti-trafficking partners · Provide additional funding for anti-trafficking programming |

Source: GAO analysis of discussion group responses. | GAO‑26‑107406

Note: Stakeholders in GAO discussion groups included U.S. agency officials managing anti-trafficking projects, Embassy officials, and representatives of organizations implementing projects in Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Ethiopia.

Stakeholders Identified Challenges to Implementing Anti-Trafficking Projects in Countries Affected by Armed Conflict

Discussion group participants identified challenges of implementing anti-trafficking projects in conflict-affected countries. We analyzed their responses and identified nine common themes.

Prioritization of humanitarian aid over anti-trafficking efforts. Participants said that, during conflict, anti-trafficking efforts often become secondary to the humanitarian response. For example, during the conflict in Ethiopia, the implementing partner and other organizations prioritized saving lives over longer-term anti-trafficking efforts. Similarly, other participants said that dealing with the immediate problems of the conflict often fully occupies the local authorities and distracts attention from efforts like uncovering trafficking operations and identifying victims of trafficking.

Increased vulnerabilities to trafficking. Participants emphasized the increased vulnerabilities to trafficking from desperate economic conditions and hesitance to report trafficking to local authorities. For example, participants said such conditions in Moldova and Ethiopia, caused in part by the conflict, pushed people to migrate illegally or to pursue opportunities in the informal market, which increased vulnerability to trafficking. Participants also said that victims of trafficking often lack trust in the local authorities and so may not report instances of trafficking.

|

Quote “Conflict complicates the nature and magnitude of trafficking as the instability creates an advantageous environment for traffickers.” Source: GAO discussion group participant. | GAO‑26‑107406 |

Changing trafficking patterns. Participants explained that, in addition to increasing the incidence of trafficking generally, conflict can also change how trafficking occurs. This may mean the objectives and funding allocations for anti-trafficking projects no longer align with needs. For example, participants said that Moldova is shifting from being an origin country to a destination for victims of trafficking, which introduces new problems. Other participants said that fraudulent recruitment and exploitation in Moldova is increasingly occurring online and that this required a shift in thinking and approach to implementing some anti-trafficking projects. Similarly, participants said that the refugee situation in Romania following the start of the conflict in Ukraine was also dynamic and made it difficult to design anti-trafficking programs. For example, refugees fleeing Ukraine were at greater risk of labor trafficking because they did not understand the local work conditions or speak the local language. For Ethiopia, participants said that an implementing partner’s previous anti-trafficking efforts had focused on forced labor, but that conflict has contributed to an increase in forced criminality, which requires a different approach.

|

Quotes “There are times when conflict makes it impossible to conduct [anti-trafficking] work in a specific city or area.” “People cannot move around freely when conflict is occurring, and that restricts operations.” Source: GAO discussion group participants. | GAO-26-107406 |

Impaired prevention and awareness among vulnerable populations. Participants said vulnerable populations in Moldova had limited awareness of the risk of trafficking and that implementing partners experienced difficulties in informing refugees about those risks as they rushed to escape the conflict in Ukraine. Participants said the disruption of government services from the conflict in Ethiopia, such as closing schools, impaired efforts to raise awareness about the risks of trafficking.

|

Quotes “There are times when conflict makes it impossible to conduct [anti-trafficking] work in a specific city or area.” “People cannot move around freely when conflict is occurring, and that restricts operations.” Source: GAO discussion group participants. | GAO-26-107406 |

Interrupted access to conduct protection activities. Security risks limited U.S. agency and implementing partner access to conflict-affected areas and the intended beneficiaries of the anti-trafficking projects. For example, participants said that the lack of security limits the U.S. government’s access and ability to gather information. Similarly, participants said that conflict amplifies concerns about the safety of local staff in Ethiopia and restricts their movement and access to some locations. For example, participants said that an implementing partner in Ethiopia limited its operations in the Amhara region after the offices and homes of its partners were looted following a flare-up of conflict.

|

Quotes “A missile attack could occur while you are conducting an awareness raising session or while you are on the way to meet with a victim [of trafficking]. In both situations, your timeframes have to change because you can’t keep doing that same activity like you planned.” “The labyrinthian approval process slows things down so much that opportunities to take effective action are gone by the time we obtain approval.” Source: GAO discussion group participants. | GAO-26-107406 |

Limited program management flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances in conflict. Participants said that agencies and implementing partners are slow to adapt or modify projects to respond to changing needs created by conflict. For example, participants from a U.S. agency said that launching a project and obligating funds can take longer than a year. According to these participants, modifications to the project timeline and funding is possible, but changing the scope, goals, or objectives of a project is more difficult. They said that a change in project direction would require ending the current project and going through project design and competitive bidding processes to address the new goals and objectives, which typically takes about two years. The participants also said that, should the agency determine to modify an award, the agency may need to notify and receive congressional approval.

Conflict can also create a need for flexibility in completing activities by the originally planned dates. In particular, if an active conflict begins while the implementing partner is conducting anti-trafficking activities, it may become difficult to complete activities on time. For example, participants said that active conflict situations in Ukraine have interrupted project activities and forced implementing partners to change their plans and timeframes. Similarly, participants said that conflict often means that project activities in Ethiopia stop and start repeatedly.

|

Quotes “Law enforcement are often very uninformed on trafficking issues.” “Many first responders have not been trained to recognize and identify the indicators or signs of human trafficking.” Source: GAO discussion group participants. | GAO-26-107406 |

Difficulties coordinating and partnering with local and international stakeholders. Participants said that local organizations in Moldova were overwhelmed, making it difficult to identify local organizations to implement anti-trafficking projects and activities. Likewise, participants said that there was strain on the government in Romania prior to the conflict in Ukraine, and it became even more difficult to coordinate anti-trafficking efforts with them while they managed competing interests.

Conflict also heightened the need for regional and international partnerships. Discussion group participants in Romania said that there was no regional approach to respond to the growing trafficking vulnerabilities at the outset of the conflict in Ukraine. This resulted in disjointed efforts to address pieces of the interrelated trafficking situation stemming from the conflict in Ukraine. Similarly, participants said the complexity of the trafficking issues in Ethiopia requires a holistic approach that includes the government, nongovernmental organizations, private sector stakeholders, and international organizations.

|

Quotes “Law enforcement are often very uninformed on trafficking issues.” “Many first responders have not been trained to recognize and identify the indicators or signs of human trafficking.” Source: GAO discussion group participants. | GAO-26-107406 |

Limited local partner capacity to conduct anti-trafficking efforts. Participants told us that local partners often did not have sufficient resources or trained personnel, which challenges project implementation. For example, participants said that local partners in Moldova did not have the resources to sustain the use of anti-trafficking technology and software. Others said that local partners in Romania have limited capacity to do activities that would make refugees from Ukraine less vulnerable to exploitation such as vetting landlords that house refugees, addressing needs of unaccompanied minors, or integrating refugees and potential victims into society.

Further, discussion group participants said the local partners did not have enough trained personnel to provide services to refugees. For example, participants said that it was difficult to recruit qualified staff to address the surging needs in Moldova. Others said that local partners in Moldova and Ukraine experienced turnover among their staff, which created a need for additional training.

|

Quote “A failed, backlogged justice system can result in the inability to move forward in any anti-trafficking area, but most immediately, it can prevent the identification and prosecution of traffickers.” Source: GAO discussion group participant. | GAO-26-107406 |