SOUTHWEST BORDER

CBP Should Improve Oversight of Medical Care for Individuals in Custody

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-26-107425

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Rebecca Gambler at gamblerr@gao.gov or Travis Masters at masterst@gao.gov

What GAO Found

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), through its components U.S. Border Patrol and Office of Field Operations, detains individuals who unlawfully enter the U.S. at short-term holding facilities. CBP personnel process individuals and determine the next course of action, such as transferring them from custody or removing them from the country. For the past decade, CBP has used contracted medical personnel at facilities along the southwest border to provide health screenings and treatment of basic medical conditions to individuals in custody.

GAO found that CBP developed policies and guidance for providing medical care to individuals in custody but has not consistently implemented them. For example, CBP requires some populations, such as children, pregnant individuals, and adults who indicated they might have an illness or injury, to receive a basic physical exam known as a medical assessment. Although CBP introduced new guidance and improved the percentage of individuals who received medical assessments, GAO found that some individuals still did not receive assessments, as required. For example, 57 percent of adults with a potential illness or injury and 20 percent of pregnant individuals did not receive medical assessments from August 2023 to August 2024, as required. Without an oversight mechanism to ensure that people in custody receive the required medical assessments, CBP may not be aware of medical needs and cannot ensure it takes the appropriate next steps for any necessary medical care.

GAO also found that CBP and contracted medical personnel did not consistently implement additional care requirements for individuals in custody who had serious injuries or illnesses (i.e., those who were medically high-risk). For example, from August 2023 to August 2024, contracted medical personnel did not conduct medical monitoring checks required for medically high-risk adults and children approximately 40 percent of the time. In July 2025, CBP developed new tools to inform its oversight efforts, but did not explain how it will use them to systematically assess whether medically high-risk individuals received their medical monitoring checks on time. Developing and implementing a mechanism to monitor this requirement and others would help CBP better ensure these individuals receive required care, and personnel are monitoring their conditions.

CBP did not consistently provide medical records and prescriptions—referred to as medical summary forms—as required, to individuals with medical issues leaving CBP custody. By not providing the medical summary forms, CBP can create challenges with continuity of care. GAO also found CBP’s oversight reports did not include data from facilities that do not have contracted medical personnel. These facilities send individuals to local hospitals or urgent care facilities for medical care, including medical assessments. Without these data, CBP cannot ensure all individuals in custody received required medical assessments to decrease the risk of adverse medical outcomes.

Moreover, GAO’s analysis showed that CBP did not consistently manage or oversee its medical services contracts. For example:

· CBP did not clearly specify minimum staffing levels it requires of the contractor in the medical services contract. As such, CBP cannot ensure it has sufficient contracted medical personnel to meet its needs for providing medical care at its facilities; and

· CBP has not analyzed the costs and benefits of providing certain types of care through contracted medical personnel versus sending individuals to local hospitals. Performing a cost benefit analysis gives CBP the opportunity to identify potential cost savings.

GAO also identified gaps in CBP’s contract oversight, which could be remedied with a contract administration plan. For example, GAO found that CBP officials with contract oversight duties did not visit CBP facilities to directly observe performance under the medical services contracts until 2024. While CBP received reports from the contractor, it did not have metrics to measure contractor performance. Without a plan that includes roles and responsiblities and performance metrics, CBP is missing opportunities to obtain a more complete and quantifiable understanding of contractor performance.

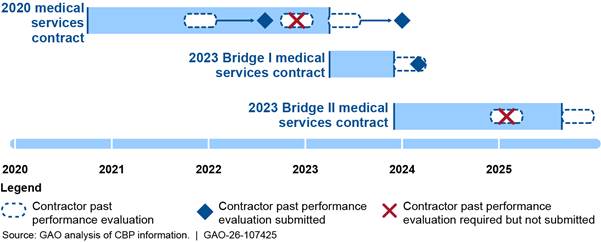

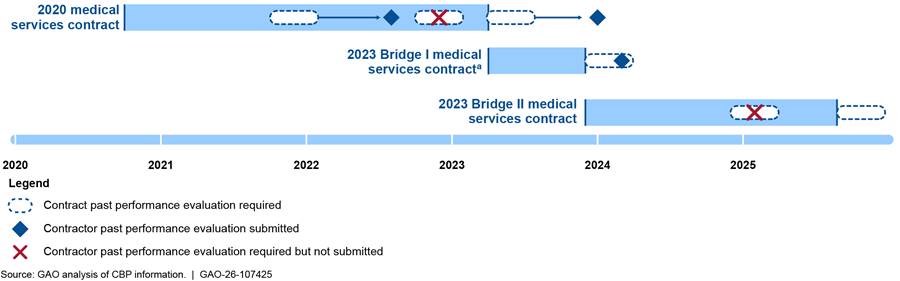

CBP did not always submit contractor past performance evaluations as required. Ensuring that CBP complies with the requirements to submit these evaluations annually and at the end of the performance period would allow CBP to use more current information in its ratings. Such compliance would also better position officials to make informed decisions when awarding future medical services contracts.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Submission of Contractor Past Performance Evaluations for the Medical Services Contracts as of August 2025

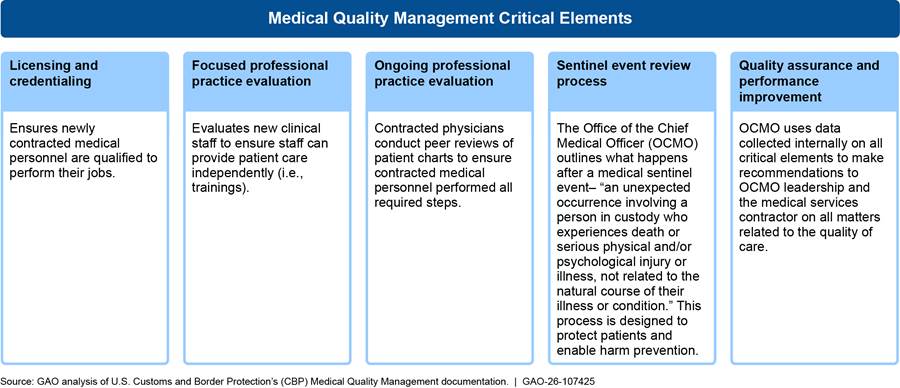

GAO found that CBP met many of its medical quality management program requirements in overseeing the quality of care that contracted medical personnel provide. However, CBP does not have guidance that includes clear responsibilities for the Office of the Chief Medical Officer and did not track corrective actions taken after some medical events. Doing so would help CBP ensure the safety and quality of all medical services provided to individuals in CBP custody.

Why GAO Did This Study

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, CBP encountered about 2 million individuals along the southwest border each year, resulting at times in overcrowding in its facilities. In May 2023, the death of an 8-year-old girl in CBP custody raised concerns about CBP's provision of medical care.

This report focuses on the southwest border and examines the extent to which CBP has (1) developed and implemented policies for providing medical care for individuals in its custody and (2) managed its contracts for medical services and provided oversight of its contractor.

To conduct this audit, GAO reviewed CBP documentation, including medical care guidance and other documentation related to screening and assessing individuals for medical issues. GAO observed CBP and contractor implementation of policies, challenges, and management of medical care at 31 CBP facilities along the southwest border, selected among areas with higher encounters.

Additionally, GAO analyzed data for fiscal years 2021 through 2024 (the most recent available at the time of our review) to assess the extent to which CBP components implemented its medical policies, its guidance, and federal internal control standards. GAO reviewed CBP contract file documentation for the three medical services contracts in this same period. GAO compared documentation of monitoring and performance activities against contract requirements, agency policies, and procurement regulations.

GAO interviewed CBP officials in headquarters and field locations to gain their perspectives on its provision of medical care. GAO also interviewed contracting officials regarding their efforts and responsibilities in managing and overseeing the contractor.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 14 recommendations to CBP, including to:

· Implement an oversight mechanism to ensure individuals get required medical assessments;

· Implement an oversight mechanism for required medical care related to medically high-risk individuals, such as medical monitoring checks;

· Develop and implement a mechanism to ensure that individuals with medical issues have their medical summary forms any time they leave CBP custody;

· Monitor whether individuals at facilities without contracted medical personnel receive medical assessments under CBP guidance;

· Specify the minimum staffing level needs for contracted medical personnel in any future medical services contracts;

· Analyze the costs and benefits of limiting the types of care that contracted medical personnel can provide versus sending individuals to local hospitals and document any resulting cost savings;

· Develop a contract administration plan for any future medical services contracts;

· Comply with the timing requirements in the Federal Acquisiton Regulation to ensure that contractor past performance evaluations for any future medical services contracts are submitted at least annually and also at the end of the period of performance; and

· Update existing guidance to include clear responsibilities and track corrective actions for sentinel events, among other medical quality management actions.

DHS concurred with thirteen recommendations. It did not concur with one recommendation to document the factors CBP personnel should consider when determining whether individuals are at-risk based on serious physical or mental injuries or illnesses for the purpose of expeditious processing under CBP’s standards. GAO maintains that DHS should do so to ensure consistent implementation of CBP’s expedited processing requirement.

Abbreviations

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

COR |

contracting officer’s representative |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

MQM |

Medical Quality Management |

|

OCMO |

Office of the Chief Medical Officer |

|

OFO |

Office of Field Operations |

|

TEDS |

National Standards on

Transport, Escort, Detention, and |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 14, 2026

Congressional Requesters

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) apprehended about 2 million individuals along the southwest border each year, resulting at times in overcrowding in its facilities. In May 2023, the death of an 8-year-old girl while in CBP custody raised concerns about CBP’s provision of medical care.

CBP is responsible for detecting and interdicting individuals unlawfully entering the U.S. CBP personnel detain apprehended individuals at short-term holding facilities (U.S. Border Patrol facilities or ports of entry) to complete processing and determine the next course of action. This can include transferring the individuals to the custody of another agency, removing them from the country, or releasing them. In addition, CBP is responsible for providing medical care for apprehended individuals in its custody. For nearly a decade, CBP has used contracted personnel at its facilities along the southwest border to provide on-site medical services for individuals in custody.

We and others have reported on issues with CBP’s provision of medical care. For example, in July 2020, we identified gaps in CBP’s implementation and oversight of medical care and made recommendations to address those issues.[1] Among other findings, we found that CBP had not provided agents and officers training on recognizing medical distress in children. We recommended CBP develop and implement this training and CBP did so. We also found that CBP did not have reliable information on deaths, serious injuries, and suicide attempts and had not consistently reported deaths of individuals in custody to Congress. We recommended that CBP provide additional guidance on the procedures for reporting deaths in custody and CBP did so. DHS’s Office of Inspector General and Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman have also raised concerns with CBP’s medical services contracts, citing staffing shortages of medical personnel at CBP facilities and inconsistent contractor compliance with contract terms, such as staffing and accuracy of financial invoices.[2]

In light of renewed concerns, you asked us to review CBP’s provision of medical care for individuals in its custody along the southwest border and CBP’s management of its contracts for medical services. This report examines (1) the extent to which CBP has developed and implemented policies for providing medical care for individuals in its custody and (2) the extent to which CBP has managed its contracts for medical services and provided oversight of the contractor.

To address these objectives, we conducted site visits to 31 CBP facilities along the southwest border in Arizona, California, and Texas from June through September 2024. Of these 31 facilities, 28 had contracted medical personnel onsite and three did not. We selected locations from areas with the highest overall volume of encounters and most growth in volume from fiscal year 2023 to fiscal year 2024.[3] During these visits, we observed facility operations and interviewed CBP officials and contractor personnel providing medical services at these facilities. We also interviewed officials with DHS and CBP headquarters, including officials within the U.S. Border Patrol, the Office of Field Operations (OFO), and CBP’s Office of the Chief Medical Officer (OCMO).

To assess the extent to which CBP has developed and implemented medical care policies, we reviewed CBP policies and guidance related to medical care, such as CBP’s 2015 National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS).[4] We also analyzed data from November 2020 through August 2024 from CBP’s electronic medical records system, Border Patrol’s system that records apprehensions and custodial activities, and OFO’s system that records data.[5] We analyzed these data to determine the extent to which CBP provided medical assessments to medically at-risk groups as required by CBP’s medical directives and guidance. We also reviewed the timeliness and frequency of enhanced medical monitoring for medically high-risk individuals in custody, as required under 2023 CBP guidance.

To assess data reliability, we discussed data collection methods with agency officials, conducted electronic testing to identify potential anomalies, and reviewed agency procedures for data quality. Although some records had missing data in certain fields or could not be matched across systems for selected analyses, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of assessing the extent to which individuals received certain medical care, as well as identifying possible trends and patterns in CBP’s provision of medical care. We assessed CBP’s medical care activities against its medical care policies and guidance, such as CBP’s 2019 Enhanced Medical Directive and June 2023 Medical Process Guidance.[6]

To assess CBP’s contract management and oversight, we reviewed contract file documentation for the three medical services contracts, which were awarded to the same contractor and in effect from fiscal years 2021 through 2025. This review included in-depth examinations of contracts and modifications for the 2020 contract (which was in effect in fiscal years 2021 through 2023) and the Bridge I contract, and modifications for the Bridge II contract through December 2024 (the latest modification we had at the time of our analysis). We also examined statements of work issued through July 2025, contracting officer’s representatives’ appointment letters, and acquisition plans. (The Bridge II contract was in effect during our review.) We reviewed contractor past performance evaluations, contractor staffing data, and documentation of CBP oversight activities, such as the Acquisition Management Division’s site visit checklist. We compared CBP’s contract management and oversight duties to DHS guidance, federal internal controls, and Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) provisions related to the contract ceiling price, exercising options, and contract data elements.[7] In addition, we compared CBP’s contractor past performance evaluation documentation for the medical services contracts to relevant FAR provisions and government-wide guidance. We also interviewed DHS and CBP officials responsible for contract administration and oversight of medical services. Appendix I provides more information about our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

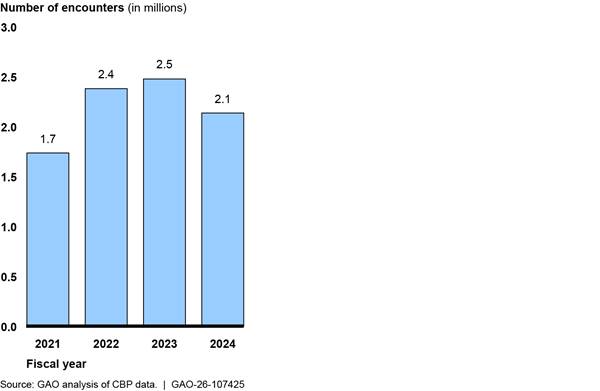

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, CBP experienced fluctuations in the number of individuals it encountered along the southwest border, as shown in figure 1. For example, CBP reported encountering about 1.7 million individuals along the southwest border in fiscal year 2021 and about 2.1 million in fiscal year 2024. For the first 10 months of fiscal year 2025 (through July 2025), the number of encounters along the southwest border decreased to a total of 422,325, according to CBP data.

Figure 1: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Total Encounters Along the Southwest Land Border from Fiscal Years 2021-2024

Note: CBP defines encounters as the sum of (1) noncitizens who are not lawfully in the U.S. whom Border Patrol apprehended; (2) noncitizens encountered at ports of entry whom Office of Field Operations determined to be inadmissible; and (3) noncitizens processed for expulsions as part of CBP’s efforts to aid the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in enforcing its authority under 42 U.S.C. § 265. See 42 U.S.C. § 268(b); 42 C.F.R. § 71.40. Title 42 expulsions began on March 21, 2020, and ended on May 11, 2023. The number of encounters could reflect unique individuals encountered more than once.

In January 2025, the President took several actions on border security and immigration. For example:

· In Proclamation 10888, Guaranteeing the States Protection Against Invasion, the President declared an invasion at the southern border of the U.S., and directed that entry of noncitizens there be suspended. The President also restricted certain noncitizens from invoking provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act, such as those related to asylum, that would permit their continued presence in the U.S.[8]

· In

Executive Order 14165, Securing Our Borders, the President directed the

Secretary of Homeland Security to detain, to the fullest extent permitted by

law, noncitizens apprehended for violations of immigration law until their

successful removal from the U.S. and to terminate the practice sometimes referred

to as “catch and release.”[9]

Under that discretionary practice, CBP exercised its discretion to release or

parole certain noncitizens under certain conditions, including when other

agencies lacked detention space.[10]

According to Border Patrol officials, as of January 20, 2025, only the Border

Patrol’s Deputy Chief of Operations can approve requests for Border Patrol

personnel to release individuals into the U.S. for any reason, including

extreme medical conditions.

CBP Processing and Medical Care for Individuals in Custody

Within CBP, Border Patrol is responsible for patrolling the areas between ports of entry to prevent individuals and goods from entering the U.S. illegally. Border Patrol may apprehend individuals between ports of entry for suspected illegal entry, which is a civil immigration offense and may also be prosecuted criminally. Border Patrol may also encounter and arrest individuals suspected of or known to have committed other criminal activities, such as drug or human trafficking. OFO is responsible for operating U.S. ports of entry. This includes inspecting all people who arrive at a port of entry to determine their citizenship or nationality, immigration status, and admissibility. After determining an individual’s admissibility into the U.S. or while making an apprehension, respectively, OFO and Border Patrol may hold individuals in short-term custody in holding facilities located at ports of entry, Border Patrol stations, and other locations to complete processing and determine the next appropriate course of action.

|

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Health Interview Questions CBP requires contracted medical or CBP personnel to use the CBP health interview form, Form 2500, to ask individuals in custody along the southwest border about their medical history and current medical issues, including any mental health issues or thoughts about hurting themselves. The form includes questions about prescription medications and other drug use; allergies; pregnancy; nursing; illness or injuries; pain; skin rashes; contagious diseases; fever symptoms; cough or breathing symptoms; and nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea symptoms. Source: CBP documentation. | GAO‑26‑107425 |

While processing individuals, contracted medical or CBP personnel conduct verbal health interviews—13 scripted questions to identify potential medical issues. For more information about these questions, see the sidebar.

Contracted medical personnel on-site at CBP facilities may also conduct medical assessments or medical encounters:

· Medical assessments include evaluating an individual’s medical history and current vitals, reviewing any symptoms, and conducting a physical exam. Contracted medical personnel are to record potential medical issues and other information they collect during medical assessments in CBP’s electronic medical records system.

· Medical encounters are evaluations to address a specific medical issue, injury, or illness identified during health interviews, medical assessments, or throughout an individual’s time in custody. During medical encounters, contracted medical personnel record the individual’s diagnoses in CBP’s electronic medical records system, which automatically assigns them a risk designation based on an approved diagnosis list.

CBP policy requires additional care for detained individuals at higher medical risk, as discussed below. See figure 2 for an example of an office at a CBP facility where contracted medical personnel conduct medical assessments or medical encounters.

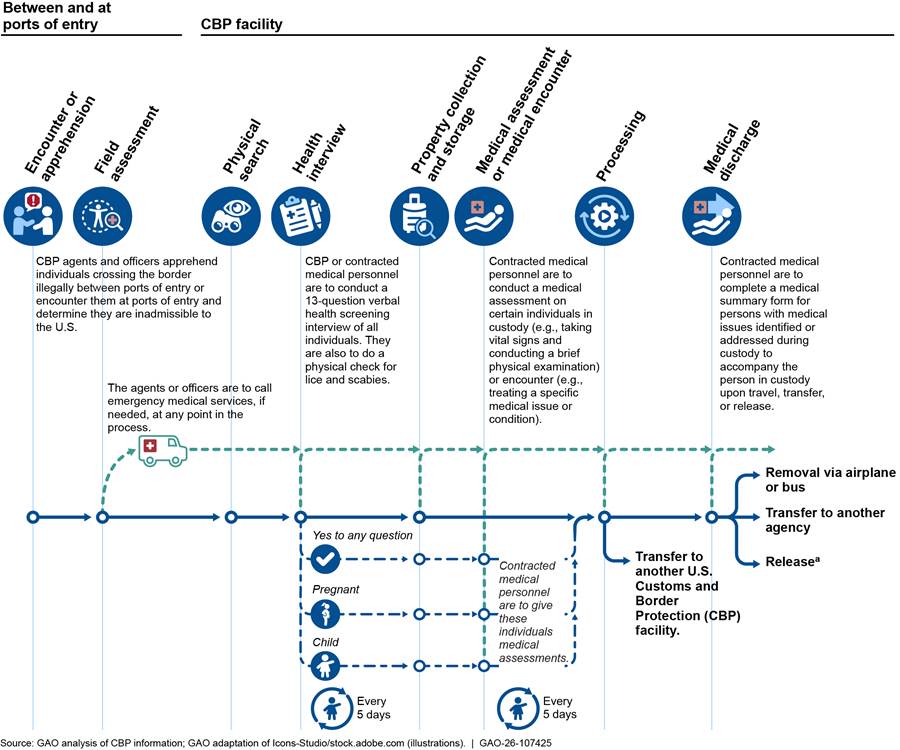

Individuals detained in CBP custody may receive medical care at various points after being encountered at the southwest border. Figure 3 shows the processing steps for individuals Border Patrol apprehended between ports of entry after crossing the southwest border and the processing steps for individuals OFO found inadmissible at ports of entry.

Figure 3: Processing Steps for Individuals Encountered Between Ports of Entry by Border Patrol and at Ports of Entry by Office of Field Operations (OFO)

aIn Executive Order 14165, Securing Our Borders, the President directed the Secretary of Homeland Security to detain, to the fullest extent permitted by law, noncitizens apprehended for violations of immigration law until their successful removal from the United States and to terminate the practice sometimes referred to as “catch and release.” Exec. Order No. 14165, 90 Fed. Reg. 8467 (Jan. 20, 2025). Under that discretionary practice, CBP exercised its discretion to release or parole certain noncitizens under certain conditions, including when other agencies lacked detention space. As of July 2025, CBP officials told us they only release individuals in rare, emergent circumstances. Additionally, under CBP’s 2023 medical process guidance, contracted medical personnel are to conduct medical assessments on all children 12 and under and unaccompanied children every 5th day in custody. At any point in the process, individuals can be transferred to or between CBP facilities. When that happens, individuals may receive health interviews and medical assessments at one or multiple locations.

Medical Services Contracts

CBP has used contracted personnel to provide health screenings, limited onsite diagnoses, and treatment of basic medical conditions at its facilities along the southwest border since 2015. At that time, CBP contracted for medical services at three Border Patrol facilities. CBP expanded the contracts over time, with a peak of 79 facilities along the southwest border in July 2024. In May 2025, CBP reduced the number to 44, which CBP officials attributed, in part, to decreases in the number of individuals along the southwest border.

CBP cumulatively obligated over $1 billion from fiscal year 2016 through August 2025 for its medical services contracts, according to federal procurement data. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the obligation information as of August 2025.[11]

Table 1: Obligations for U.S. Customs and Border Protection Medical Services Contracts in Effect, Fiscal Year 2016–August 2025

|

Contracts |

Total obligations as of August 2025 |

Total period of performance as of August 2025 |

|

|

2015 Medical Services Contract |

$113,399,862.53 |

September 30, 2015–September 29, 2020 |

|

|

2020 Medical Services Contract |

$421,385,258.87 |

September 30, 2020–March 29, 2023 |

|

|

2023 Bridge I Medical Services Contract |

$197,988,653.01 |

March 30, 2023–November 29, 2023 |

|

|

2023 Bridge II Medical Services Contract |

$402,641,997.58 |

November 30, 2023–August 27, 2025a |

|

|

Total |

|

$1,135,415,771.99 |

Not applicable |

Source: GAO summary of federal procurement data. | GAO‑26‑107425

Note: The 2015 contract includes six task orders that were placed under a General Services Administration blanket purchase agreement. The 2020 contract and the two bridge contracts were task orders placed under a federal supply schedule contract established by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Generally, blanket purchase agreements are agreements between agencies and vendors with terms in place for future use to fulfill repetitive needs; funds are obligated when orders are placed. Similarly, federal supply schedules are contracts awarded to multiple vendors that provide similar products and services. For the purpose of this review, we generally refer to the task orders as “contracts” or “medical services contracts.”

aOn May 30, 2025, CBP’s Office of Acquisition added three additional option periods to the 2023 Bridge II contract to extend the period of performance by 90 days from May 30, 2025, through August 27, 2025, and then extended it again through September 27, 2025. In addition, CBP awarded the Bridge III medical services contract on September 28, 2025, after we provided DHS with our draft report for review and comment. Thus, we did not include the Bridge III contract within the scope of our review.

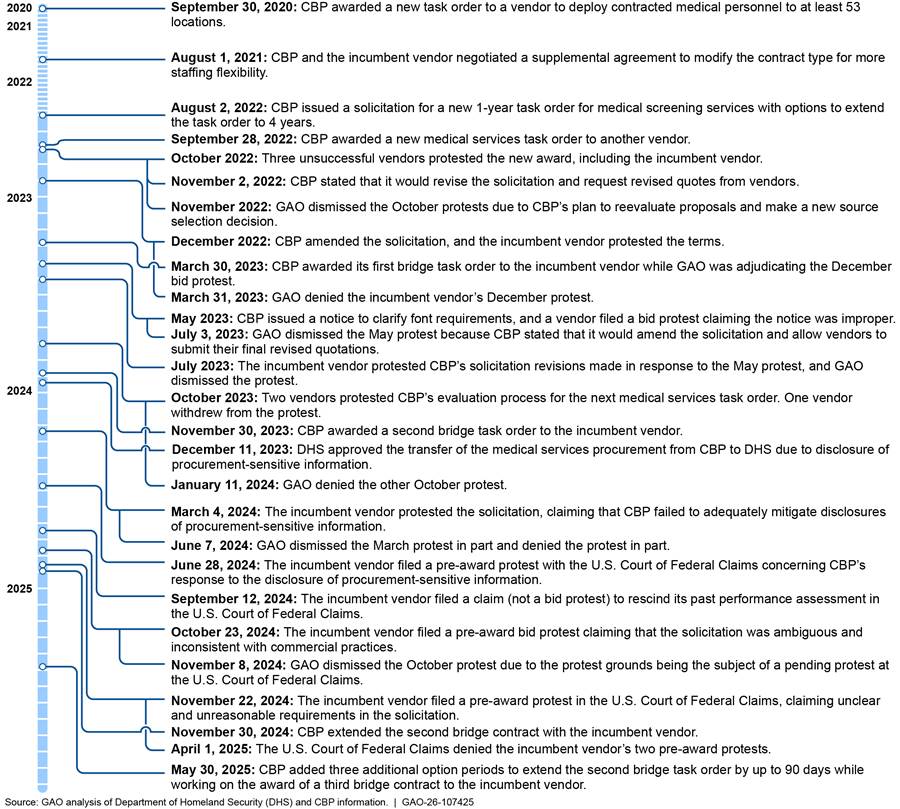

In September 2020, CBP awarded a contract for medical services to Loyal Source Government Services.[12] Starting in March 2023, CBP executed a series of bridge contracts—all awarded to the incumbent contractor—due to a delay in the award of the next contract.[13] One reason for the delays was bid protests. As of May 2025, the incumbent contractor and other prospective vendors had filed more than 10 bid protests related to the procurement of the next medical services contract. CBP took corrective action in response to the protests, including amending the solicitation and requesting revised quotes from vendors. In the interim, CBP has awarded bridge contracts. The Bridge II contract was in effect through August 27, 2025, at the time of our review.[14]

The DHS Office of the Chief Procurement Officer, Office of Procurement Operations, has been in the process of awarding the next medical services contract since December 2023. At that time, CBP’s Head of the Contracting Activity transferred the source selection and contract award responsibility from CBP’s Office of Acquisition to DHS’s Office of the Chief Procurement Officer, Office of Procurement Operations, due to CBP government officials potentially disclosing unauthorized procurement-sensitive information. See figure 4 for a timeline of key events and decisions related to the recent CBP medical services contracts.

Figure 4: Timeline of U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Medical Services Contracts’ Key Procurement Events and Decisions, September 2020 – May 2025

Note: GAO has responsibilities for deciding bid protests, which are separate from its audit activities. 31 U.S.C. § 3552. While there is no government-wide definition for bridge contracts, we have defined it as an extension of an existing contract beyond the period of performance (including base and option years), or an award of a short-term sole-source (noncompeted) contract to the incumbent contractor to avoid a gap in service when an existing contract is set to expire but there is a delay in awarding a follow-on contract.

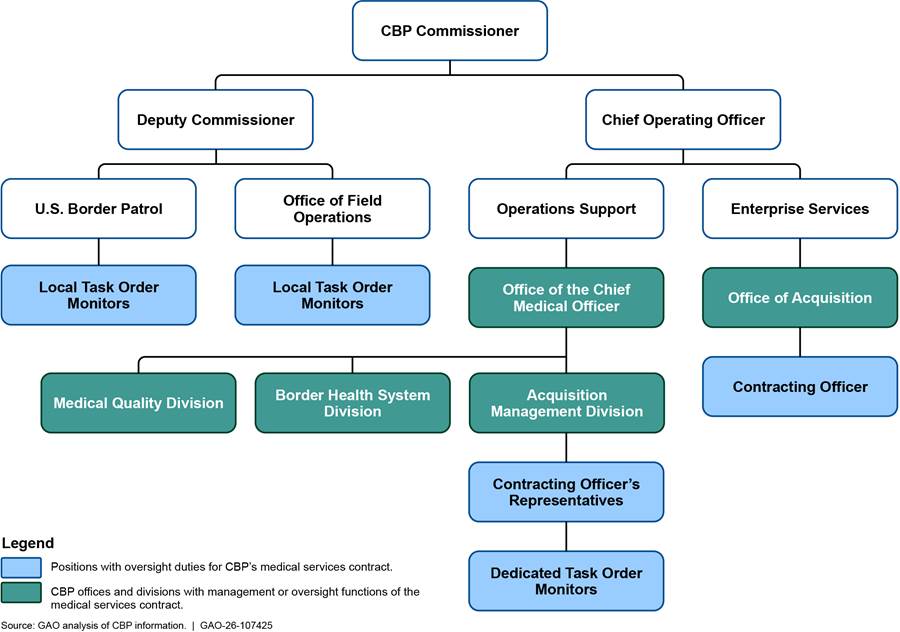

CBP Roles and Responsibilities for Medical Services Management and Oversight

Several CBP offices are responsible for managing and overseeing medical services. CBP’s Office of Acquisition procures goods and services for CBP. Office of Acquisition contracting officers have authority to enter into, administer, and terminate contracts and make related determinations, as well as responsibility to ensure the contractor complies with the contract’s terms and conditions.[15] Contract oversight is largely the responsibility of the contracting officer and the contracting officer’s representatives (COR), if appointed to a particular contract, who assist the contracting officer. Contracting officers may also appoint technical monitors (also referred to as task order monitors) to assist in contract oversight.[16] Task order monitors generally work with CORs.

CBP’s Office of the Chief Medical Officer (OCMO) is responsible for providing medical direction and oversight for CBP’s medical support efforts. Three offices within OCMO play a role in managing CBP’s medical care for individuals in its custody, as shown in figure 5:

· The Border Health System Division is to manage and implement CBP’s policies and guidance related to medical care.

· The Medical Quality Division is to manage and provide oversight of the clinical aspects of medical care, including the contractor’s quality assurance program.

· The Acquisition Management Division is to conduct contractor oversight through CORs and task order monitors. For example, CORs appointed on the medical services contract are to monitor contractor invoices and ensure that background investigation packets are complete.[17]

Figure 5: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Offices and Positions with Management or Oversight of Medical Services

CBP Has Developed Medical Care Policies and Guidance, but Has Not Consistently Implemented Them

CBP has developed policies and guidance for providing medical care to individuals in custody along the southwest border. CBP OCMO took several steps to facilitate the implementation of its 2023 medical care guidance across CBP, such as improving the availability of supervising physicians. However, CBP did not consistently ensure that children, pregnant individuals, or sick or injured adults received medical assessments, as required by its guidance. Further, CBP and contracted medical personnel did not consistently implement requirements for medically high-risk individuals in CBP custody, such as ensuring that these individuals are expeditiously processed and receive additional medical checks. We also found that CBP has limited oversight into medical care provided to individuals at facilities without contracted medical personnel. Furthermore, CBP personnel did not consistently provide individuals their medical records and prescriptions when they left custody, as required by CBP policy.

CBP Developed Policies and Guidance for Providing Medical Care to Individuals in Custody

CBP has developed policies and guidance related to the medical care that CBP and contracted medical personnel are to provide individuals detained in its short-term holding facilities, as shown in Table 2. According to OCMO officials, CBP made several improvements to its medical care guidance for individuals in custody after the death of an 8-year-old girl in CBP custody in May 2023. For example, CBP developed medical process guidance in June 2023 and an addendum with additional medical care and monitoring requirements across CBP in October 2023. This addendum includes risk designations based on individuals’ medical status.

Table 2: Overview of U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Key Policies and Guidance on Medical Care for Individuals in Custody Along the Southwest Border as of August 2025

|

Document and date issued |

Medical process requirements |

|

National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS) (2015) |

· CBP personnel generally should not detain individuals for longer than 72 hours. Personnel are required to monitor detention areas; visually inspect individuals for signs of injury, illness or other physical or mental concerns; report any injury or illness; and ensure medication and medical documentation accompanies individuals in custody when they are transferred. CBP personnel should also document observed or reported injuries or illnesses in the appropriate electronic system of record and provide or seek appropriate medical care in a timely manner. |

|

CBP Directive No. 2210-004 Enhanced Medical Support Efforts (December 2019) |

· CBP or contracted medical personnel must conduct health interviews for all children in custody (17 years old and under) along the southwest border. Additionally, individuals with observed medical issues are to receive a health interview or a medical assessment or be referred to a local health unit. · CBP personnel must ensure that contracted medical personnel conduct a medical assessment for: · Children aged 12 and under, · Adults who responded “yes” to one of the health interview questions asking if they have had medical issues, including individuals who are pregnant, or · Individuals with a known or reported medical concern. |

|

CBP Office of the Chief Medical Officer Medical Process Guidance (June 2023) |

· In addition to the requirements noted above related to health interviews, CBP or contracted medical personnel must document health interview responses for individuals who: · Responded with a “yes” on an initial verbal health interview, including pregnant individuals, or · Have a potential illness, injury, medication requirement, or other medical issue. · All children are to receive a health interview every 5th day in custody. · The above individuals, as well as children aged 13 and above, are also required to receive a medical assessment (which includes checking vitals, reviewing symptoms, and conducting a physical exam) from contracted medical personnel or a local health provider within 24 hours of arrival. Additionally, contracted medical personnel are to conduct medical assessments on all children 12 and under and unaccompanied children every 5th day in custody. · Contracted medical personnel are to conduct medical encounters to evaluate and treat acute medical issues onsite, as appropriate. |

|

CBP Office of the Chief Medical Officer Medical Process Guidance Annex A: Elevated in-Custody Medical Risk (October 2023) |

· When completing a medical assessment or a medical encounter, contracted medical personnel must select a diagnosis in the electronic medical records system, which automatically assigns a risk designation and adds specific care requirements for the individual. CBP developed the following risk designations: · Red—individuals in custody at elevated/high medical risk (e.g., chest pain, heat stroke, abdominal open wound). · Orange—individuals with an acute issue (e.g., an active infection, such as strep or flu) who are receiving treatment. · Yellow—individuals with a well-controlled chronic issue. · Green—individuals with no known medical issues. |

Source: GAO summary of CBP documentation. | GAO‑26‑107425

Note: CBP expanded the medical care requirements in its 2023 guidance, though the new guidance stated it did not replace or supersede the 2019 directive.

CBP Took Various Steps to Implement Aspects of Its Medical Care Guidance

CBP OCMO took several steps to facilitate the implementation of its 2023 medical care guidance. For example, OCMO worked with the medical services contractor to ensure that on-call supervising physicians—pediatric advisors for children or supervising physicians for adults—were available for consultation at all times. Following the death of an 8-year-old girl in May 2023, the DHS Office of Health Security found that the supervising physician contact roster for CBP’s medical services contract was out of date. OCMO officials stated that they requested the medical services contractor resolve this issue by updating the roster. CBP officials stated the contractor subsequently implemented a unified hotline number rather than a roster, where a physician answers calls in a rotating system at all times.[18]

During our 2024 site visits to 28 CBP facilities with contracted medical personnel onsite, personnel at three facilities in Arizona and Texas told us the on-call supervising physicians had sometimes been unavailable in the past. However, they said they had seen consistent improvement in the availability of the physicians to consult on cases for medically high-risk individuals in CBP custody after CBP worked with the contractor to resolve this issue. We requested that the contracted medical personnel call the pediatric advisor or supervising physicians at most of the facilities we visited, and these physicians were available for consultation every time.[19]

Moreover, OCMO and the medical services contractor ensured that CBP locations had requisite medical supplies, as called for in its medical services contract. During our visits to CBP facilities, we observed that the medical supplies contractors needed were available. Contracted medical personnel stated they generally had the medical supplies they needed to provide basic medical care.[20] Figure 6 includes photographs of basic medical supplies (e.g., over-the-counter medications, antiseptics, and bandages) stored at various CBP facilities.

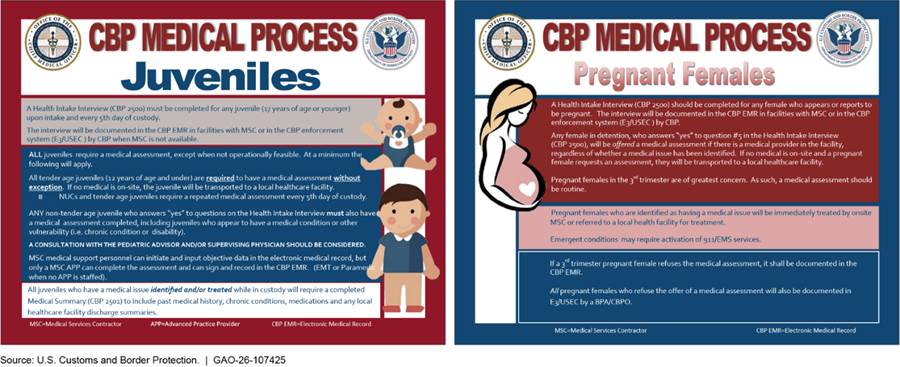

Furthermore, OCMO developed job aids and standard operating procedures to help guide CBP and contracted medical personnel through key steps of the 2023 guidance, as shown in figure 7.

OCMO also began producing internal daily oversight reports related to medical interactions at CBP facilities with contracted medical personnel, such as the number of individuals in custody who received medical assessments and medical encounters. Additionally, OCMO produced monthly reports for DHS’s Office of Health Security with information such as top diagnoses of medically high-risk children and adults. As of March 2025, OCMO’s Border Health System Division was developing a compliance program using data to improve the tracking and monitoring of CBP’s compliance with aspects of its medical care policies and guidance. For example, CBP developed a dashboard to monitor whether children 12 years old and under have received a medical assessment every 5th day they are in custody, as required in CBP’s 2023 medical process guidance.

CBP Did Not Consistently Ensure That Individuals in Custody Received Medical Assessments When Required

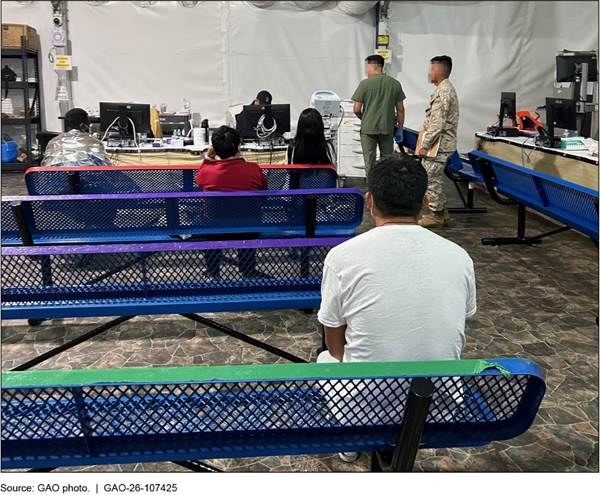

While in CBP custody, certain individuals are required to receive a medical assessment—a basic physical exam and review of symptoms, vitals, and medical history. However, CBP has not ensured that those individuals in custody consistently receive these assessments. Specifically, CBP’s 2019 directive states that Border Patrol agents and OFO officers must ensure a medical provider conducts a medical assessment for (1) all tender-age children, defined as children 12 years old and under, and (2) all individuals who responded “yes” to one of the questions on the initial health interview, including individuals who are pregnant, along the southwest border.[21] CBP’s 2023 medical guidance expanded these requirements by requiring medical assessments for all children (not just tender-age).[22] Additionally, tender-age children and unaccompanied children must receive a medical assessment every 5 days while in custody. Figure 8 shows individuals waiting for a medical assessment at a CBP facility we visited.

Figure 8: Individuals in U.S. Customs and Border Protection Custody Waiting for a Medical Assessment

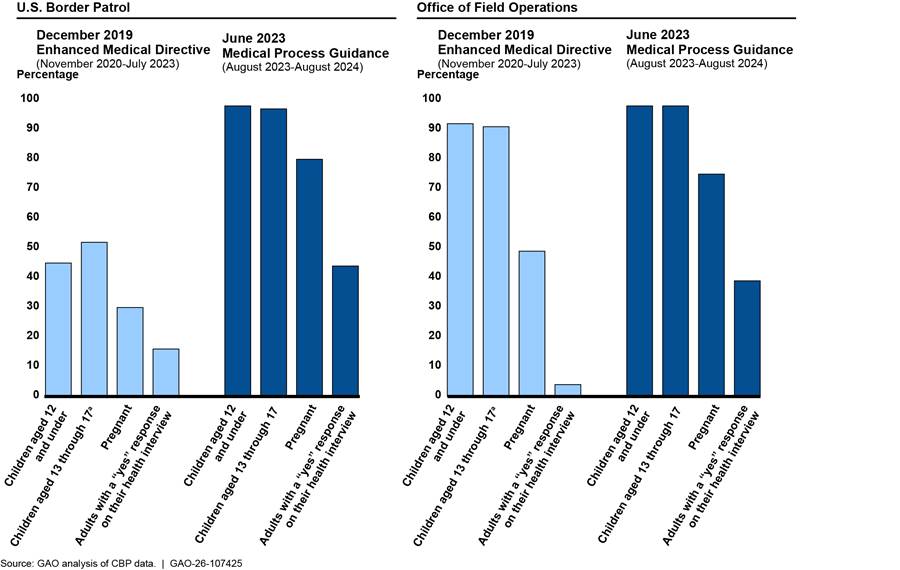

Our analysis of data from CBP’s systems found that some individuals in CBP custody did not receive medical assessments as required under the original medical directive (November 2020–July 2023) and the new medical process guidance (August 2023–August 2024).[23]

November 2020–July 2023. We found that less than 50 percent of each group specified by CBP policy to receive a medical assessment while in Border Patrol custody received that assessment during this time period. In particular, about 45 percent of tender-age children, 30 percent of pregnant individuals, and 16 percent of other adults with a “yes” health interview response received a medical assessment.

In comparison, tender-age children in OFO custody had much higher rates of completed medical assessments (92 percent). However, 49 percent of pregnant individuals and only 4 percent of adults with a “yes” health interview response in OFO custody received medical assessments during this time period.[24] See figure 9 for more information regarding the extent to which individuals received medical assessments while in Border Patrol or OFO custody.

August 2023–August 2024. We found that CBP’s implementation of its medical assessment requirement improved across all covered groups since August 2023, particularly among children. For instance, based on our analysis of CBP data, we found that about 98 percent of children in both Border Patrol and OFO custody received a medical assessment from August 2023 through August 2024.

Additionally, among tender-age children and unaccompanied children who remained in Border Patrol or OFO custody for at least 5 days, more than 97 percent of these children received at least one medical assessment for every 5-day period, as required by CBP’s 2023 medical process guidance.

Despite substantial improvements across all groups since the 2019 directive, we found that CBP did not consistently implement its medical assessment policies for adults with a “yes” health interview response and pregnant individuals, as shown in figure 9.

Figure 9: Percentage of Individuals in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Custody Who Received a Medical Assessment as Required Per CBP Policy and Guidance, November 2020–August 2024

aChildren aged 13 and above were not required to receive a medical assessment under the 2019 directive but were under the 2023 guidance.

One reason that CBP did not consistently implement its medical assessment policy is that contracted medical personnel were sometimes performing medical encounters (evaluations to address acute medical concerns) instead of the required medical assessments. Medical assessments and medical encounters contain many of the same elements, but their purposes are different. According to CBP policy and guidance, medical assessments are required for certain individuals in custody, whereas medical encounters are meant to address an acute medical issue experienced during someone’s time in CBP custody. When individuals receive a medical encounter instead of a medical assessment, they receive some, but not all, of the medical care required by CBP policy and guidance. Notably, medical assessments capture an individual’s medical history while medical encounters do not. As a result, in the event of an emergent medical issue, CBP may not have all the medical information it needs to address the issue effectively.

During our site visits to facilities across Arizona, California, and Texas, contracted medical personnel from 15 of the 28 facilities indicated they performed medical encounters to fulfill the medical assessment requirement or did not understand some of the differences between the two. For example, some contracted medical personnel at sites we visited stated they conduct medical assessments for children and pregnant individuals and conduct medical encounters for any individual who says “yes” to a health interview question. This is not consistent with CBP’s guidance, which states children, pregnant individuals, and individuals with a “yes” to a health interview question are all to receive a medical assessment (a more general examination) and then receive a medical encounter (to address a more specific or acute medical issue), if appropriate.

A senior OCMO official stated that distinguishing between medical assessments and medical encounters is important for medical processing and oversight purposes. This is because OCMO officials use electronic medical records data on medical assessments and medical encounters to assess needs in CBP facilities. For example, a tender-age child with multiple medical assessments has likely been in custody for a longer period, whereas a child with multiple medical encounters is likely ill and could require greater medical attention. As such, it is important for individuals in custody to receive the medical assessments and medical encounters outlined in CBP policy and guidance, according to the OCMO official.

Due to the impact this confusion could have had on the data, we analyzed data from CBP’s systems from August 2023 to August 2024 to determine the extent to which individuals received either a medical assessment, a medical encounter, or both. For this time period, we found 98 percent of children, 96 percent of pregnant individuals, and 86 percent of other adults with a “yes” health interview response received either a medical assessment or a medical encounter (or both), suggesting that contracted medical providers may have performed medical encounters in lieu of medical assessments for some individuals.

Following discussions with us about the issues we identified, in July 2025, CBP officials stated that they re-sent CBP’s medical process guidance to the medical services contractor and planned to meet with the contractor’s leadership to reiterate the differences between medical assessments and medical encounters. Communicating this information to the contractor’s leadership is a positive initial step. By ensuring contracted medical personnel in the field, who are responsible for implementing the guidance, receive these clarifications and understand the difference between medical assessments and medical encounters and operational reasons concerning their different usages, OCMO will be better positioned to monitor and assess medical needs in CBP facilities. By clarifying the differences and reasons through additional training or guidance, CBP will also ensure that individuals in custody receive the medical care required by CBP policy and guidance.

Our analysis of data from CBP’s systems also found that some individuals in CBP custody received neither a medical assessment nor a medical encounter under the 2023 medical process guidance from August 2023 through August 2024. Specifically, 14 percent of adults with a “yes” health interview response received neither a medical assessment nor a medical encounter (more than 5,000 individuals). Additionally, despite the high rates of children and pregnant individuals who received either a medical assessment or a medical encounter, over 9,000 children and pregnant individuals received neither one. See table 3 for more information on the numbers of individuals who did not receive either one.

Table 3: Individuals in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Custody Who Did Not Receive a Medical Assessment or a Medical Encounter from Contracted Medical Personnel, August 2023-August 2024

|

Population |

Percentage who did not receive a medical assessment or a medical encounter |

|

Children under 13 |

2% (5,454 out of 300,490) |

|

Children aged 13 through 17 |

3% (3,650 out of 143,928) |

|

Pregnant individuals |

4% (260 out of 5,969) |

|

Other adults with a “yes” health interview response |

14% (5,632 out of 41,510) |

Source: GAO analysis of CBP data. | GAO‑26‑107425

Note: Contracted medical personnel conduct medical assessments on certain individuals, which include a physical exam and an evaluation of an individual’s medical history, current vitals, and symptoms. Medical encounters are evaluations to address a specific medical issue, injury, or illness identified during health interviews, medical assessments, or throughout an individual’s time in custody. CBP’s June 2023 medical process guidance requires medical assessments for all children and individuals who responded “yes” to one of the questions on the initial health interview, including pregnant individuals. While one of the CBP health interview questions asks if individuals are pregnant, we use “other adults with a ‘yes’ health interview response” to refer to non-pregnant adults with an affirmative response to any other health interview question.

CBP officials stated that some individuals may not have received either a medical assessment or a medical encounter due to administrative oversight. For example, CBP officials stated they may have missed providing a medical assessment or a medical encounter to individuals when there were large numbers of encounters along the southwest border. Additionally, a CBP official stated that there may have been a small number of instances where contracted medical personnel conducted a medical assessment or a medical encounter but did not document it.

Additionally, there may have been brief periods where the electronic medical records system was down, according to officials. Consequently, contracted medical personnel would have to document the assessment or the encounter on paper and may not have subsequently recorded that in the electronic medical records system. They also noted that some individuals may have declined medical service, been referred to a local healthcare facility, or were not in custody long enough to receive medical care.

At the time of our review, OCMO’s oversight reports detailed the number of medical assessments contracted personnel performed, but did not include information on whether individuals who were required to receive medical assessments actually received them. After discussions with us about the issues we identified, in July 2025 CBP developed new tools to help oversee whether these individuals correctly received medical assessments as required. For example, OCMO developed an observation checklist and an onsite assessment tool for its personnel to utilize on visits to CBP facilities, allowing OCMO personnel to record whether they observe contracted medical personnel providing medical assessments as required. OCMO also developed a tool to review medical records for individuals in custody and assess whether they received required medical care, including medical assessments. These new tools should help OCMO collect consistent information during visits and records reviews.

However, OCMO did not explain how it will use these tools to systematically oversee facilities across the southwest border. For example, OCMO did not include a plan for implementing these tools, including how many oversight visits they will conduct, how many medical records they will review, or how they will select facilities and medical records to ensure individuals in custody received medical assessments when required.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government calls for agencies to design control activities, including mechanisms that enforce management’s directives, to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[25] Without an oversight mechanism to ensure individuals receive medical assessments as required by CBP policy and guidance, CBP cannot be assured that it is aware of the medical needs of the children, pregnant individuals, and adults with an injury or illness in its custody, or that contracted medical personnel provided required follow-on medical evaluations for known medical needs.

CBP Did Not Consistently Implement Policies and Guidance for Processing and Monitoring Medically High-Risk Individuals

CBP Did Not Expeditiously Process Some Medically High-Risk Individuals

CBP policy requires personnel to expedite processing for medically high-risk individuals, but CBP did not do so for all such individuals during the period we reviewed. More specifically, CBP’s National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS) states that CBP personnel should generally not detain individuals for longer than 72 hours.[26] TEDS also states that, when operationally feasible, CBP personnel should expeditiously process at-risk individuals to minimize their time in CBP custody. Under TEDS, agents and officers may determine that an individual in custody is at-risk based on an observed or reported serious physical or mental injury or illness.[27]

In May and October 2023, the Acting CBP Commissioner issued memorandums reaffirming that CBP personnel should consider expeditiously processing at-risk or medically fragile individuals. The May 2023 memorandum also stated that CBP personnel should consider releasing at-risk or medically fragile individuals with a Notice to Appear (a charging document to appear in immigration court) to minimize their time in CBP custody.[28]

In May 2025, CBP rescinded these memorandums, stating that they were misaligned with current agency guidance and new immigration enforcement priorities.[29] According to one OCMO official, the rescinded memorandums conflicted with the January 2025 Executive Order restricting the practice of releasing individuals in CBP custody with a Notice to Appear.[30] However, the May 2025 memorandum states that CBP personnel should continue to adhere to TEDS.

During our 2024 site visits to CBP facilities in Arizona, California, and Texas, CBP personnel stated that they generally prioritized processing high-risk individuals, such as individuals with medical conditions, to minimize their time in custody. Our analysis of CBP data from October 2023 through August 2024 supported these statements. We found that CBP held medically high-risk individuals (defined as individuals designated “red” under CBP’s October 2023 medical process guidance addendum) in custody for approximately 48 hours on average, which is less than the 72-hour standard identified in TEDS. CBP also processed medically high-risk individuals on average nearly twice as fast as low-risk individuals in custody.[31]

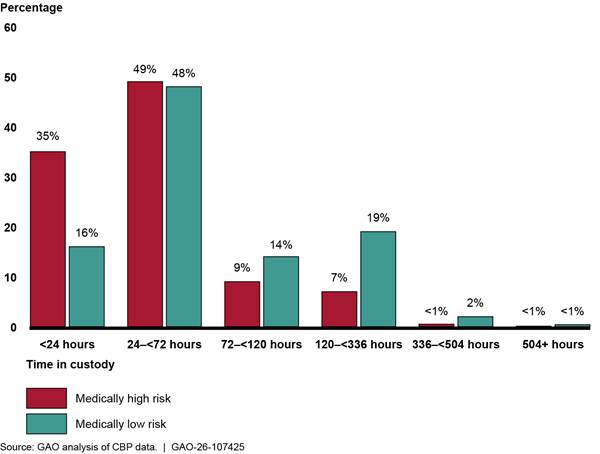

However, of the individuals designated medically high-risk in CBP custody from October 2023 through August 2024, we found that 17 percent were in custody for 72 hours or more (1,123 out of 6,755).[32] For more information about the time medically high-risk and low-risk individuals were in CBP custody, see figure 10.

Figure 10: Time-in-Custody for Individuals Designated Medically High-Risk versus Low-Risk in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Custody, October 2023-August 2024

Note: Contracted medical personnel designate whether an individual presents high in-custody medical risk while in CBP custody based on certain diagnoses including chest pain, heat stroke, or an abdominal open wound, among other things. Therefore, this analysis only includes individuals that saw contracted medical personnel for these risk designations while in CBP custody. We compared individuals who were only designated “red” medical risk, the highest level of risk, throughout their time in custody (6,755 individuals) with individuals who were only designated “green,” the lowest level (58,713 individuals). We did not include individuals whose risk level changed during their time in custody (e.g., individuals who were initially designated red and were later downgraded to lower levels of risk, such as orange, yellow, or green).

To ensure that Border Patrol and OFO personnel are aware of medically at-risk individuals in their facilities, CBP officials stated they linked the electronic medical records system and processing systems in 2024. This linkage means that if a contracted medical provider designates someone as medically high-risk in the electronic medical records system, they are also marked at-risk in the Border Patrol and OFO processing systems.[33]

OCMO and Border Patrol officials stated that some individuals designated medically high-risk may be safe to remain in custody for longer periods of time and therefore do not need to be expeditiously processed. Officials stated that “medically high-risk” is a broad category and encompasses individuals with a wide variety of conditions and injuries. For example, OCMO officials stated that a child with autism would be designated medically high-risk but would not necessarily require expeditious processing if provided appropriate accommodations while in custody. However, CBP has not documented the specific factors Border Patrol and OFO personnel should consider when determining whether medically high-risk individuals should be considered at-risk for the purpose of expeditious processing.

Furthermore, CBP officials stated that other factors outside of CBP’s control affect how quickly they can process individuals in custody. For example, if an individual in custody is considered a national security risk or expressed a fear of returning to their home country, CBP may be required to follow other processes that may lengthen an individual’s time-in-custody, regardless of their medical status. According to one official, an individual being in the hospital may also affect their time-in-custody.

Border Patrol officials also said encounters along the southwest border were high during the period we examined (October 2023 through August 2024). Border Patrol often had to wait for flights to remove individuals or for other agencies like U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to take custody of individuals, resulting in longer times in CBP custody. As such, they stated that Border Patrol agents sometimes made their own determinations about whom to prioritize for processing based on, for instance, the severity of the conditions or injuries that led contracted medical personnel to designate individuals as medically high-risk.

In July 2025, OCMO officials told us they communicate with Border Patrol and OFO on certain medical cases based on the severity of the individual’s medical condition, the availability of support required to manage that condition, and the capabilities of onsite medical care. However, CBP has not documented these factors in policy or guidance, nor communicated them to the CBP personnel responsible for processing individuals.

Medically high-risk individuals are the most vulnerable population within CBP custody, according to CBP guidance. Clearly documenting what factors Border Patrol and OFO personnel should consider when determining whether an individual should be considered at-risk for the purpose of expeditious processing would help ensure personnel are consistently implementing the expedited processing requirement, when it is possible to do so.

Some CBP Locations Did Not Fully Implement Medical Care Requirements for Medically High-Risk Individuals

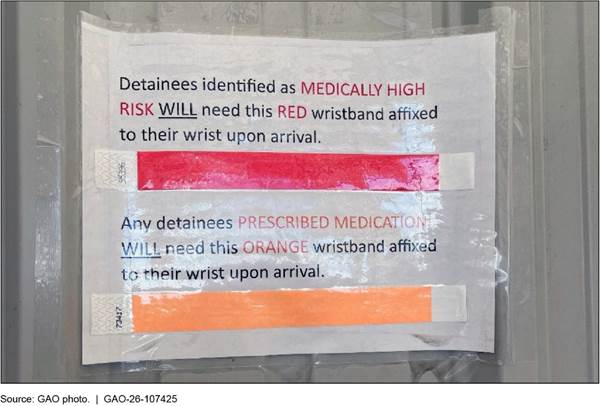

CBP guidance includes additional requirements for caring for medically high-risk individuals while they are in custody, but CBP did not fully implement these requirements across facilities with contracted medical personnel. According to CBP’s medical process guidance, contracted medical personnel should conduct medical monitoring checks at least every 4 hours on medically high-risk individuals and identify these individuals with a red wristband.[34] According to CBP officials, the red wristbands help ensure that medically high-risk individuals are visible to everyone, including both contracted medical personnel and CBP personnel who are observing and monitoring individuals in custody, as shown in figure 11.

Figure 11: A Red Wristband Requirement for Medically High-Risk Individuals in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Custody

Note: Despite the text associated with the orange wristband above, CBP policy does not require wristbands for individuals who require prescribed medication. Some facilities we visited used other colors for this purpose, while other facilities did not use wristbands for this purpose at all.

During our 2024 site visits to CBP facilities in Arizona, California, and Texas, we found that some facilities were following this guidance, while others were not. For example, contracted medical personnel at the facilities we visited generally stated that they performed medical monitoring checks on medically high-risk children every 4 hours. However, contracted medical personnel reported differing intervals for enhanced medical monitoring checks of medically high-risk adults. For instance, at 7 of the 28 facilities with contracted medical personnel that we visited, contracted medical personnel stated that they conduct medical monitoring checks on medically high-risk adults in custody every 4 hours, as required. However, contracted medical personnel at five facilities stated they conduct checks on medically high-risk adults every 8, 12, or 24 hours.[35]

Our analysis of data from CBP’s systems from October 2023 through August 2024 found inconsistent implementation of the additional medical monitoring checks required for adults and children in custody.[36] Specifically, we found medically high-risk children and adults received the required enhanced medical monitoring checks every 4 hours approximately 43 percent of the time.[37] Additionally, about one third of the facilities we visited did not use red wristbands to identify medically high-risk individuals and personnel at several others reported differing understandings of the red wristbands’ meaning. Specifically, we observed personnel from 11 of 28 facilities using red wristbands to identify and monitor high-risk individuals in custody, while personnel at 10 facilities did not. Furthermore, at seven facilities, the contracted medical personnel stated they use red wristbands to identify and monitor high-risk individuals, but Border Patrol agents or OFO officers at those facilities did not know what the bands were for or stated they did not use them (and thus would not be able to more closely monitor these individuals).[38]

OCMO officials stated that CBP personnel may be unfamiliar with the requirements for medically high-risk individuals in custody because it is rare to encounter such individuals at CBP facilities across the southwest border. For instance, one CBP official estimated they had seen no more than 20 medically high-risk individuals in custody across the southwest border per day in March 2025. The CBP officials also stated that it is the contracted medical personnel’s responsibility to diagnose and designate these individuals, put the red wristbands on them, and conduct the appropriate medical monitoring checks. During our site visits, we observed reminders in the electronic medical records system that reminded contracted medical personnel of these requirements.

At the time of our review, OCMO’s oversight mechanisms did not allow it to monitor whether CBP and contracted medical personnel have implemented all of the requirements for medically high-risk individuals in custody. For example, OCMO tracked the total number of medical monitoring checks individuals received but did not monitor whether the frequency of the checks complied with its guidance. For example, it did not monitor if a medically high-risk individual in custody received a medical monitoring check every 4 hours.

As previously mentioned, in July 2025 CBP developed an observation checklist and an onsite assessment tool for OCMO officials’ site visits to CBP facilities. The checklist and tool include checks and questions to assess the extent to which medically high-risk individuals receive required care. For example, the observation checklist requires personnel to observe whether contracted medical personnel are monitoring medically high-risk individuals at appropriate intervals and distributing red wristbands as required. OCMO also developed a medical records review tool, which assesses compliance with various medical care requirements, including whether the individual was assigned an appropriate risk designation and whether contracted medical personnel contacted the supervising physician or pediatric advisor for medically high-risk individuals. Additionally, OCMO developed a dashboard listing the medically high-risk individuals in custody along the southwest border, their diagnoses, and the date and time of their most recent medical monitoring check. This could allow OCMO to identify, on a case-by-case basis, individuals who are overdue for medical monitoring checks at a particular point in time.

Developing the tools and dashboard are positive steps, since they will provide important information to inform OCMO’s oversight efforts. However, OCMO did not explain how it will use the tools and dashboard to systematically oversee medical care for medically high-risk individuals in custody. For example, OCMO did not explain how many oversight visits they will conduct, how many medical records they will review, or how they will select facilities and medical records for review. Furthermore, OCMO did not explain how it will use the dashboard to systematically assess whether medically high-risk individuals received their medical monitoring checks on time.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government call for agencies to design control activities, including mechanisms that enforce management’s directives, to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[39] Developing and implementing an oversight mechanism to ensure contracted medical personnel consistently implement CBP’s additional requirements for medically high-risk individuals, such as the 4-hour medical monitoring checks and red wristbands, would help CBP better ensure these individuals are receiving required care and that personnel are monitoring their medical conditions.

CBP Improved its Ability to Monitor Whether Physicians Were Contacted for Certain Medically At-Risk Individuals

During our review, we found that CBP’s electronic medical records system did not have accurate records regarding whether contracted medical personnel contacted supervising physicians (physicians on-call). However, CBP recently improved the system to allow for better monitoring. CBP’s 2023 medical process guidance states that contracted medical personnel must contact a supervising physician when they determine that an adult in custody is medically high-risk. During our review, contracted medical personnel could not input whether they contacted a supervising physician in the electronic medical records system because the field was automatically populated to “Yes” and the response could not be changed—even if they did not call the physician, according to CBP officials.[40]

CBP officials stated they intentionally locked this field in the system in October 2023 due to concerns that contracted medical personnel were not consistently calling supervising physicians as required. Specifically, officials stated that they decided to lock the field to help contracted medical personnel understand that calling the supervising physician is mandatory. One CBP official indicated the contracted medical personnel could include a note in a free-text field if they did not call the supervising physician.

However, after discussions with us in July 2025, OCMO revised its electronic medical records system to ensure that contracted medical personnel could accurately input whether they called a supervising physician. By allowing contracted medical personnel to accurately input this information, CBP improved its ability to collect quality information and accurately assess whether contracted medical personnel contacted the supervising physician for medically high-risk individuals in CBP custody, as required. This should help improve CBP’s awareness of day-to-day clinical operations and provide CBP greater assurance that supervising physicians provided contracted medical personnel guidance on cases involving serious injury or illness.[41]

CBP Has Limited Oversight into the Medical Care of Individuals at Facilities Without Contracted Medical Personnel

CBP has limited oversight into medical care provided to individuals at facilities without contracted medical personnel. CBP’s 2023 medical process guidance states that if there are no contracted medical personnel at a CBP facility, individuals in custody at that facility who are required to receive a medical assessment may be referred to a local medical provider (e.g., an urgent care facility or a hospital). Additionally, that guidance states individuals with life-threatening or emergent medical needs should be referred to a local medical provider. However, OCMO officials stated that if a CBP facility does not have contracted medical personnel, they generally cannot monitor whether an individual in custody there received a medical assessment. This is because OCMO’s oversight reports—which are based on the electronic medical records system data populated by contracted medical personnel—do not include facilities without contracted medical personnel.

Specifically, OCMO personnel track and monitor daily reports on medical interactions at facilities with contracted medical personnel, such as the number of individuals in custody that received medical assessments, medical encounters, and medical checks. They also monitor data on the number of individuals contracted medical personnel see and refer to local hospitals for serious conditions. However, these reports do not include information on the extent to which individuals at facilities without contracted medical personnel received the medical care required by CBP policy and guidance, such as medical assessments, at local hospitals or urgent care facilities.

As CBP has reduced the number of facilities with contracted medical personnel in 2025, the number of facilities that OCMO does not monitor has grown.[42] One OCMO official stated this has not yet created oversight challenges because the overall number of encounters and individuals in CBP’s custody is low. The official stated that OCMO can check whether specific individuals received an off-site medical assessment or medical encounter by checking whether an individual left CBP’s facility, based on the individual’s records in the Border Patrol or OFO processing systems. However, this would require them to look at specific records of individuals in custody and OCMO officials were not systemically monitoring these records.

CBP officials noted that CBP needs to determine how to ensure individuals in custody at facilities without contracted medical personnel receive required medical care. For example, an OCMO official stated that if encounters along the southwest border rose, they would likely need to consider how to revise their monitoring reports to include care at local medical facilities. OCMO officials stated that they also communicate with CBP components as needed about specific individuals in custody. However, the component outreach is ad hoc and only occurs when the component determines it may need assistance from OCMO. These efforts do not allow OCMO to monitor whether individuals at facilities without contracted medical personnel, such as sick adults or pregnant individuals, received required medical assessments from a local health provider.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state agencies should use quality information to monitor whether they are achieving their objectives.[43] Without including information in its monitoring reports about facilities without contracted medical personnel and individuals who received medical care at local medical facilities, CBP does not have complete, quality information to ensure all individuals in its custody received the medical care required by guidance. Furthermore, without tracking this information, CBP does not have insight into the medical care individuals receive, if any, at facilities without contracted medical personnel CBP-wide.

CBP Did Not Consistently Provide Required Medical Documentation to Individuals Leaving CBP Custody

When individuals leave CBP’s custody, whether through release or transfer to another agency, CBP policy requires that they receive documentation of their medical records and medication needs. However, CBP has not consistently provided such documents to individuals leaving its custody. More specifically, TEDS states that CBP agents and officers must ensure that medical records accompany individuals transferring out of CBP custody.[44] Additionally, CBP policy and guidance require medical documents and prescriptions in the individuals’ property and in CBP’s files to go with individuals with medical issues transferring to an external agency.[45] If CBP releases or transfers individuals out of its custody before they receive their medication, they must also have a written prescription, according to CBP guidance. CBP provides this documentation by completing a medical summary form, which details an individual’s medical disposition, medication, and follow-up care requirements. Under CBP policy, medical summary forms are completed by contracted medical personnel and should accompany individuals who had medical issues identified or addressed while in CBP custody when they leave CBP custody.

However, we found that CBP components were not consistently providing medical summary forms to individuals leaving its custody. For example, in March 2025, a senior OCMO official stated that OCMO had conducted an internal review of CBP’s electronic medical records system data and found that CBP does not routinely provide medical summary forms to individuals who are being released or transferred to an agency other than ICE. CBP did not take further action based on this review and deferred to the components to provide the forms. During our site visits, CBP officials and contracted medical personnel from three CBP facilities also stated that individuals sometimes leave CBP custody before receiving a medical summary form, which would include records of their prescription medications. We also spoke with four nongovernmental organizations that provided services to individuals released from CBP custody along the southwest border in 2024. All four organizations stated they provided services for individuals who did not have any kind of medical records detailing the medical care they received while in CBP custody.

Border Patrol headquarters officials confirmed that individuals in custody who saw medical personnel should have their medical summary forms when they leave CBP custody. However, Border Patrol officials stated that recent changes in CBP’s processing of individuals have made it harder to consistently provide these forms. For example, some individuals who have left CBP custody may return to CBP facilities from the custody of other agencies to be transported to their removal flights. In these instances, Border Patrol officials noted they do not confirm that the individuals have a medical summary form when they leave CBP’s custody for a second time, even though CBP requires it.

A January 2025 OCMO memorandum on medical summary documentation stated that the medical summary form should be considered “the most important part of the medical documentation” to ensure continuity of care and identify medical risks for transporting individuals.[46] Without a medical summary form, individuals may not have the information they need to resume medical treatment or treat issues that were identified in CBP custody upon transfer to another agency, release, or repatriation. Developing a mechanism to ensure that individuals who had medical issues identified or addressed receive their medical summary forms any time they leave CBP custody would also help CBP ensure that other agencies who transport or assume custody of these individuals are aware of their medical needs.

CBP Did Not Consistently Manage or Oversee Its Medical Services Contracts

As previously mentioned, CBP used contracted medical personnel in 44 CBP facilities along the southwest border as of May 2025 (at its peak, CBP used them in 79 facilities as of July 2024), but we identified gaps in how CBP managed its 2020 and two bridge medical services contracts. For example, CBP did not establish clear criteria for sufficient staffing levels in its 2023 Bridge II contract. Additionally, CBP has not analyzed the costs and benefits of its decisions to limit the types of care contracted medical personnel can provide to identify opportunities for potential cost savings. Further, CBP has made missteps in its management of contract costs, option amounts, and contract periods in its three contracts. In addition, CBP has gaps in its oversight of contractor performance. For instance, the agency has not developed a plan for administering the contract and monitoring the medical services contractor’s performance, has not ensured that staff designated as task order monitors for the contract have the appropriate certifications for their role, and has not annually submitted all its contractor past performance evaluations as required. Finally, while CBP met many of the requirements it set for itself in overseeing the quality of care that contracted medical personnel provide, OCMO’s Medical Quality Division did not document some of those activities as required.

CBP Had Gaps in Its Management of Its Bridge II Medical Services Contract

CBP Did Not Specify Clear Criteria for Sufficient Staffing Levels in the CBP Medical Services Contract