HUMANITARIAN PAROLE

DHS Identified Fraud Risks in Parole Processes for Noncitizens and Should Assess Lessons Learned

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Rebecca Gambler at Gamblerr@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

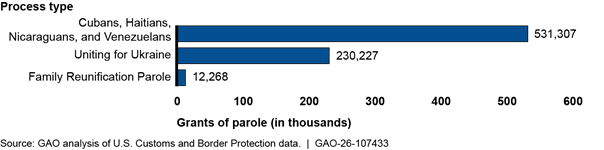

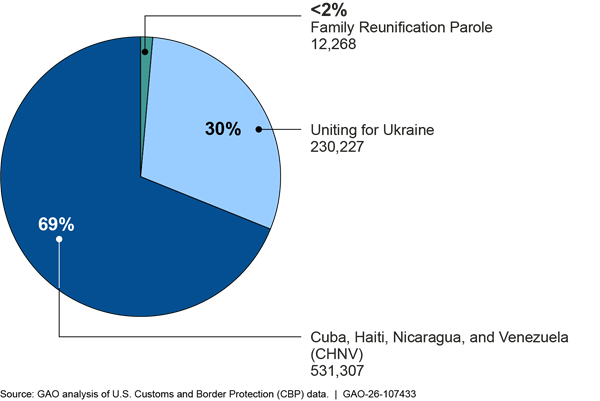

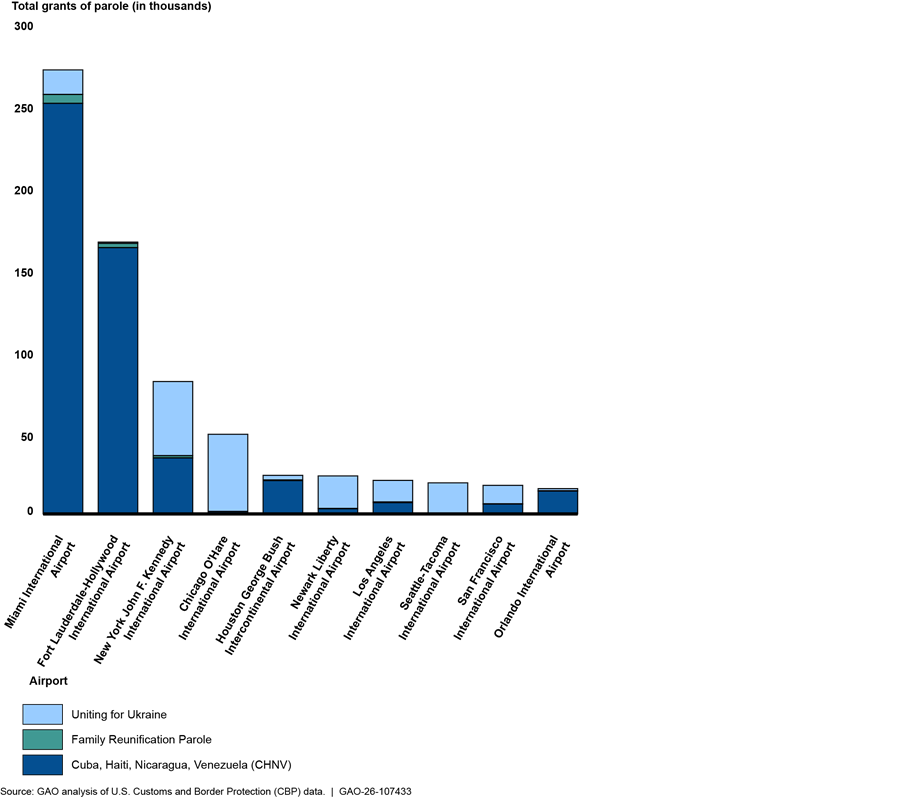

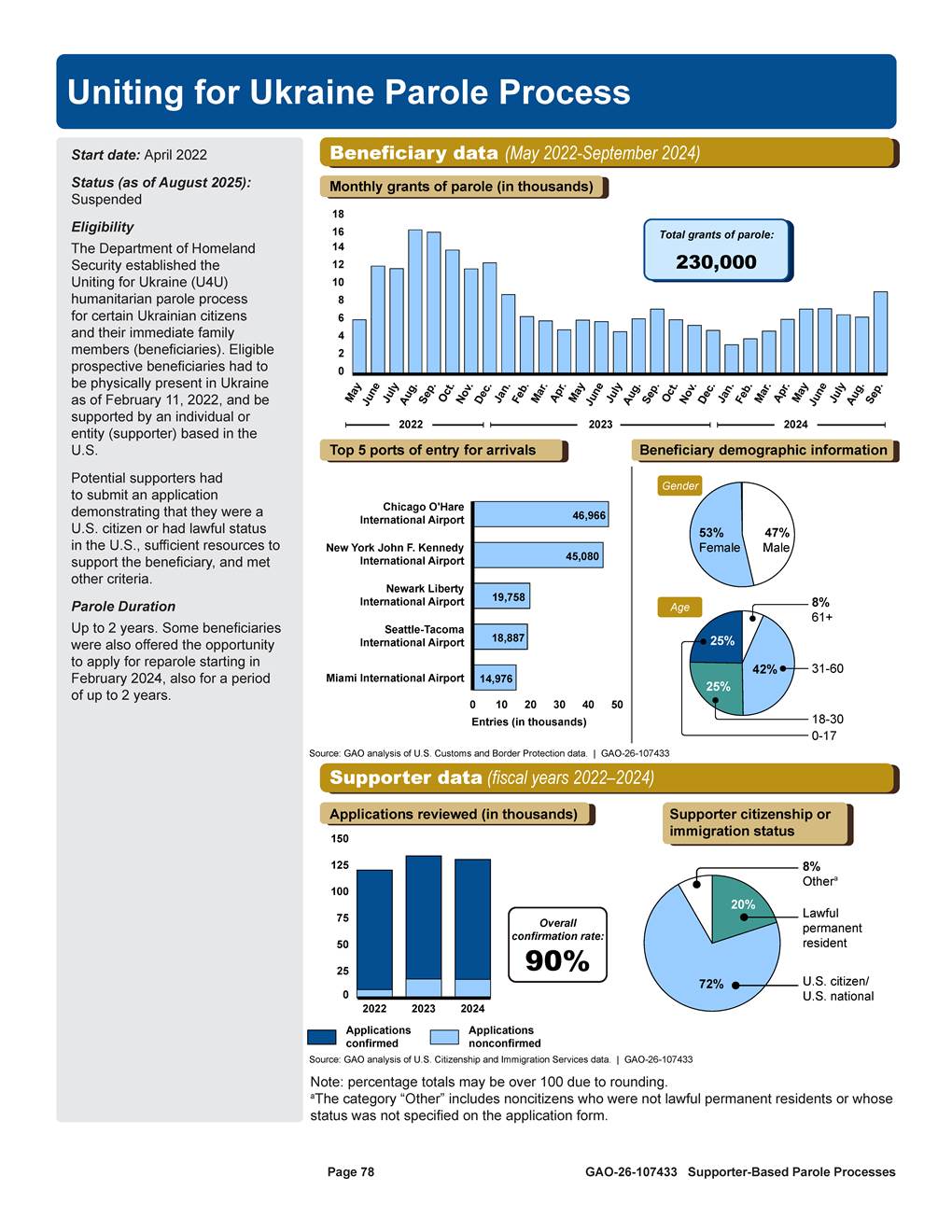

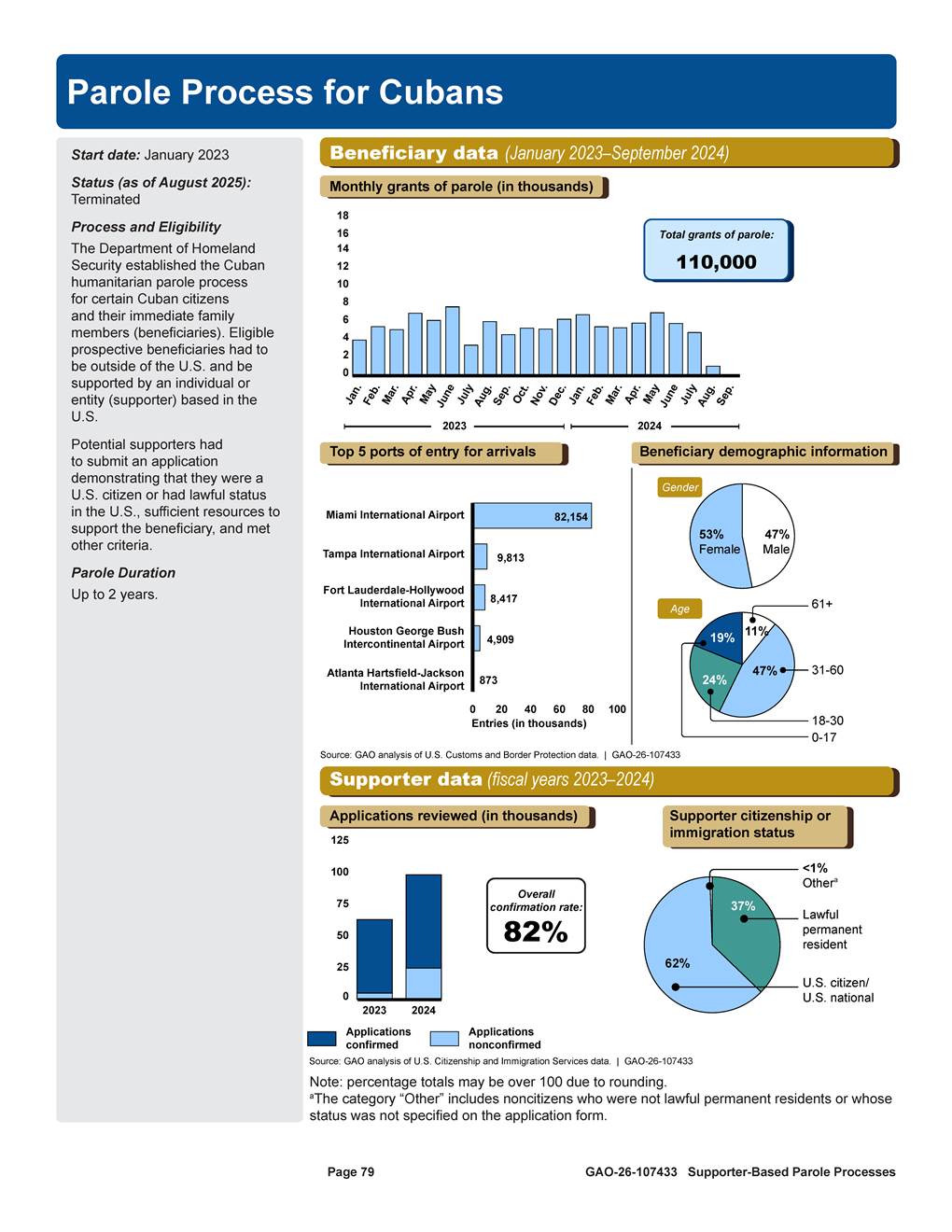

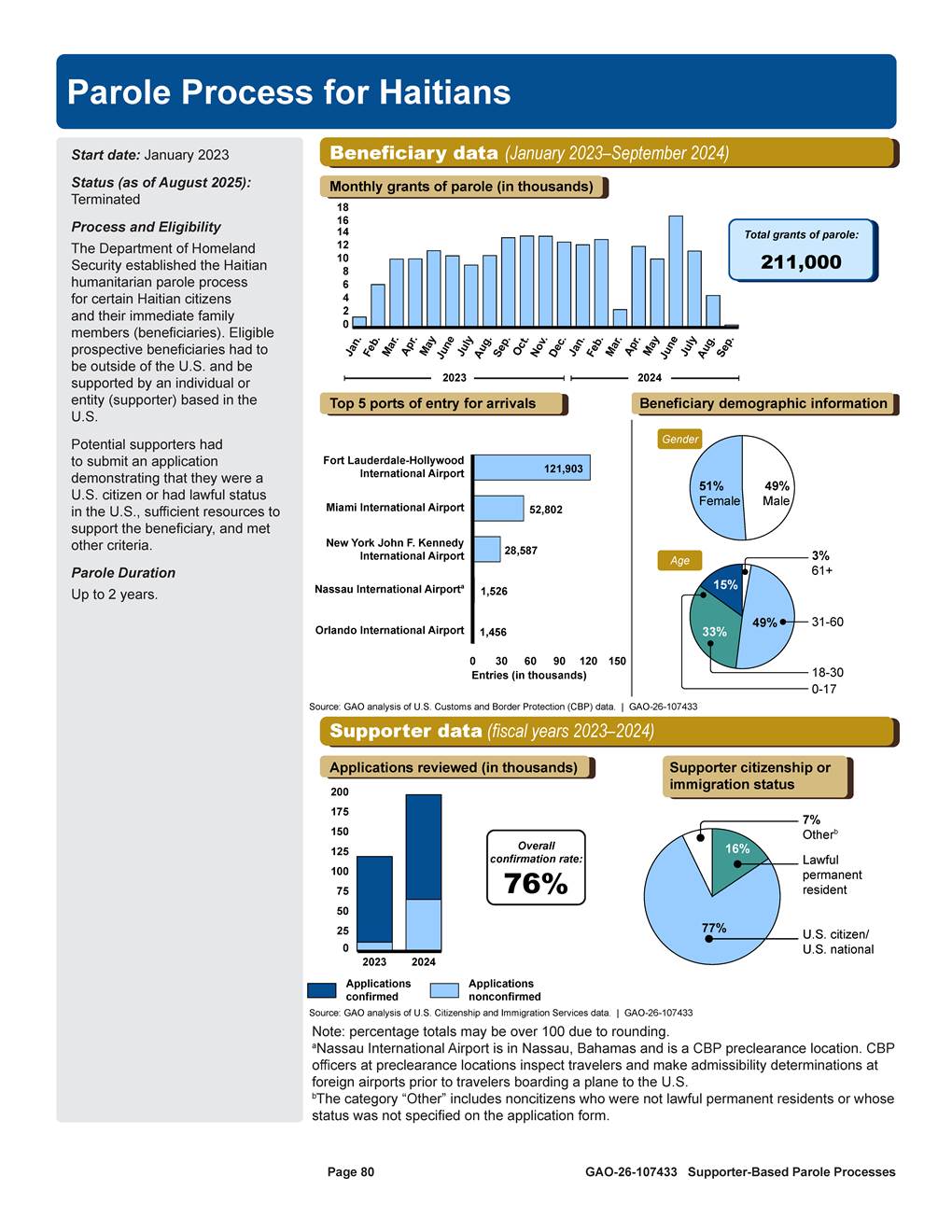

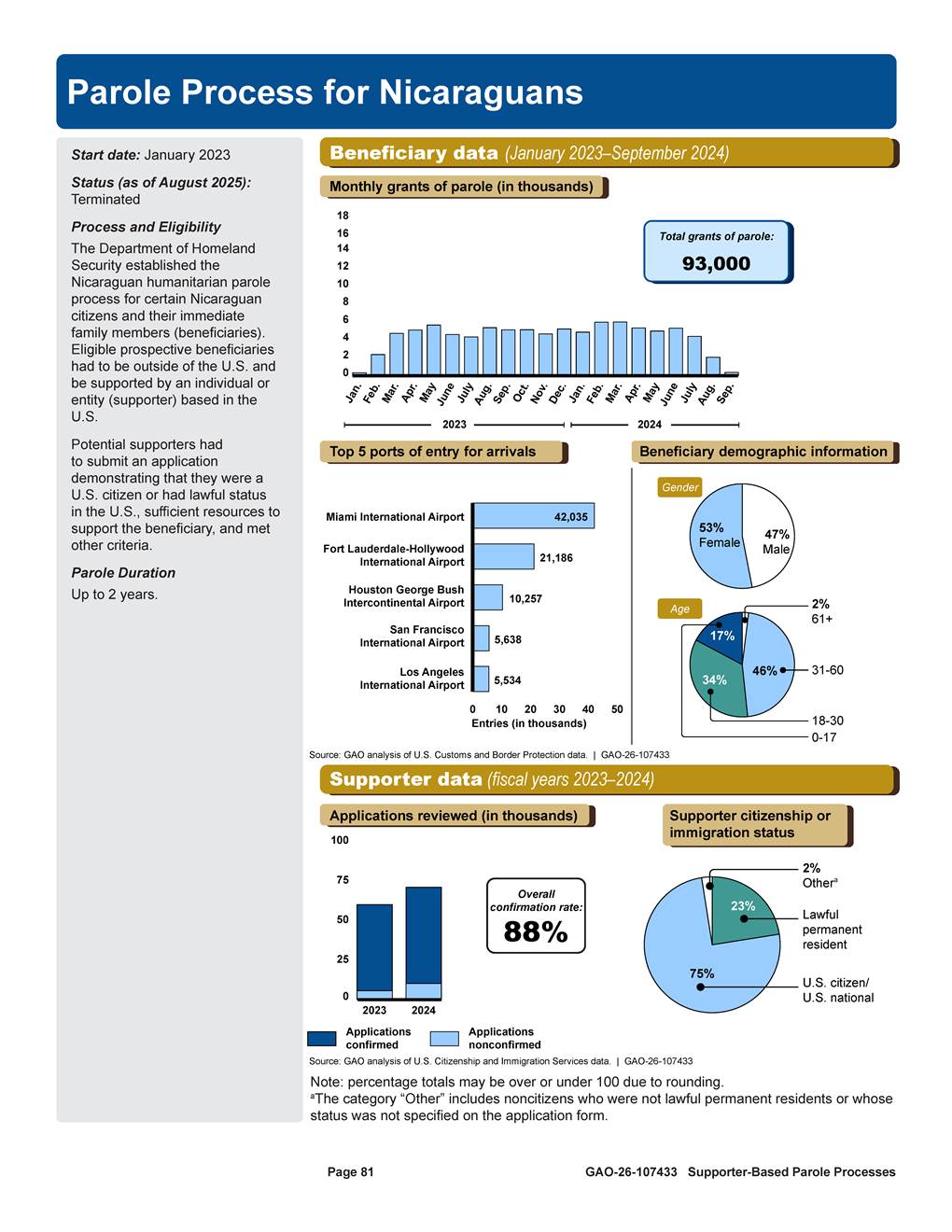

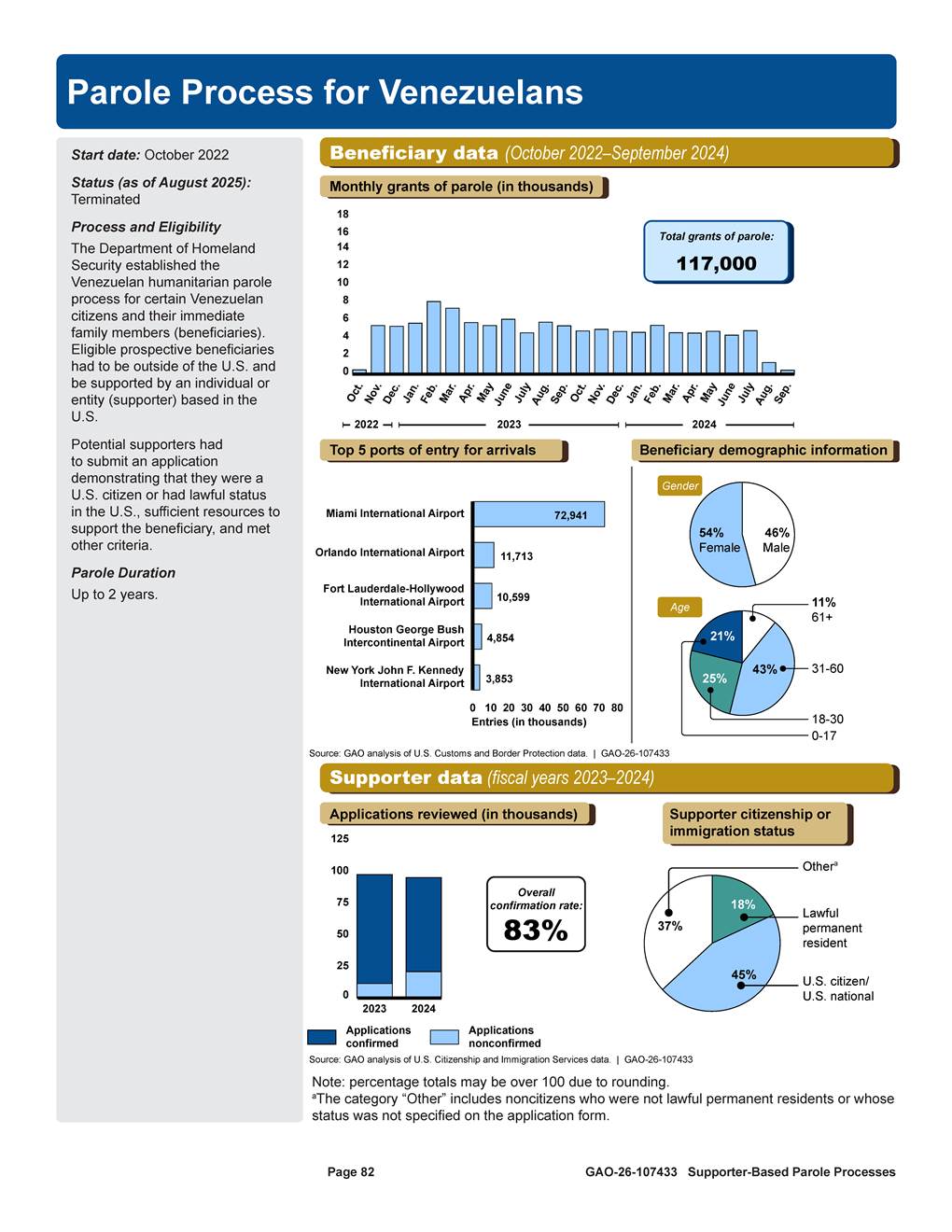

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began granting parole—temporary permission to stay in the U.S.—to certain eligible noncitizens through its supporter-based parole processes in May 2022. From that time through September 2024, DHS granted parole to about 774,000 noncitizens across three supporter-based processes: Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV), Uniting for Ukraine (U4U), and family reunification parole (see figure).

Grants of Supporter-Based Parole, May 2022–September 2024

Shortly after U4U began, the DHS components responsible for implementing the parole processes—U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—identified fraud risks and other vulnerabilities. Subsequently, a July 2024 USCIS review found that fraud indicators were widespread in U4U and CHNV. USCIS attributed these risks to insufficient internal controls in its supporter vetting process—for example, not having automated processes to prevent or detect possible fraudulent activity. DHS has since suspended or terminated the processes. However, USCIS has not developed an internal control plan for new or changed programs in the future. Such a plan could include basic antifraud controls and mechanisms to help proactively identify and mitigate fraud risks.

In addition, DHS faced other challenges implementing the parole processes, including limited staffing and resources, inconsistent review of the reasons for beneficiaries requesting parole, and supporters not upholding their commitments to beneficiaries. DHS agencies began taking some corrective actions, but DHS has not assessed lessons learned from the parole processes that it could apply to other efforts, such as lessons related to the use of temporarily assigned staff. By assessing and applying lessons learned from the parole processes, even if the processes have ended, DHS could improve other areas of its operations and thus be better positioned to avoid similar challenges in the future.

Prior to January 2025, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which is responsible for enforcing U.S. immigration laws, did not have enforcement guidance focused specifically on parole beneficiaries, according to ICE officials. After January 2025, in alignment with new presidential administration executive orders and DHS policies, ICE instructed its officers to review each noncitizen case they encounter and determine whether any noncitizen’s parole status should be terminated. As of May 2025, ICE officials said that ICE did not have any nationwide enforcement efforts for paroled noncitizens and that its field offices determined any such actions on a case-by-case basis.

Why GAO Did This Study

In 2022 and 2023, DHS introduced new processes for humanitarian parole in response to increases in noncitizens arriving at the southwest border. The processes allowed eligible noncitizens from certain countries to travel to the U.S. to seek a grant of parole. To be eligible, noncitizens had to have a U.S.-based supporter apply to financially support them. DHS briefly suspended some of the processes in summer 2024 before restarting them. Then, in January 2025, following an executive order, DHS suspended all of the processes.

GAO was asked to review DHS’s administration and oversight of these parole processes. This report addresses (1) what DHS data show about supporter-based parole processes; (2) challenges that existed, and the extent to which DHS addressed them; and (3) DHS’s approach for taking enforcement actions against parole beneficiaries, as appropriate. GAO analyzed USCIS, CBP, and ICE documents and data on the parole processes from 2022 to 2025. GAO also (1) visited four U.S. airports where large numbers of noncitizens seeking parole arrived and (2) interviewed USCIS, CBP, and ICE officials from headquarters and field offices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including one to USCIS to develop an internal control plan that can be applied to a new or changed program, and two to DHS to assess and apply lessons learned from the parole processes. DHS concurred with the first recommendation and disagreed with the two to assess and apply lessons learned, noting terminating the processes sufficiently addresses the challenges. GAO believes these recommendations remain valid and could help improve other areas of DHS operations beyond parole.

Abbreviations

CBP U.S. Customs and Border Protection

CHNV process for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans

DHS Department of Homeland Security

FDNS Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate

ICE U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

NTC National Targeting Center

TPS temporary protected status

U4U Uniting for Ukraine

USCIS U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 11, 2025

Congressional Requesters

According to the Department of State, 20 million people in the western hemisphere were displaced as of 2023 due to violence, persecution, and other humanitarian crises. These events contributed to increases in encounters by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) at the southwest border as individuals have sought entry into the U.S.[1] In fiscal year 2022, DHS reported about 2.4 million encounters with noncitizens at the southwest land border, a 37 percent increase from fiscal year 2021.[2] In fiscal year 2024, DHS reported about 2.1 million encounters with noncitizens at the southwest border, although encounters declined to about 444,000 in fiscal year 2025.

To address these humanitarian crises and the challenges posed by the number of encounters, in fiscal year 2022 DHS began to introduce new processes for humanitarian parole. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 provides the Secretary of Homeland Security with the authority, under the Immigration and Nationality Act, to parole noncitizens, on a case-by-case basis, into the U.S. temporarily for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.[3] Pursuant to this authority, DHS may set the duration of the parole and DHS officials may terminate parole.[4] The Secretary of Homeland Security has delegated parole authority to three agencies in the department: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

In 2022 and 2023, DHS implemented three different supporter-based processes for humanitarian parole: Uniting for Ukraine (U4U); Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV); and an updated family reunification parole process.[5] One aspect of these processes was that they required eligible noncitizens (prospective beneficiaries) to have a U.S.-based supporter who agreed to financially support them for the duration of their parole period. We refer to these processes as supporter-based parole processes throughout this report.

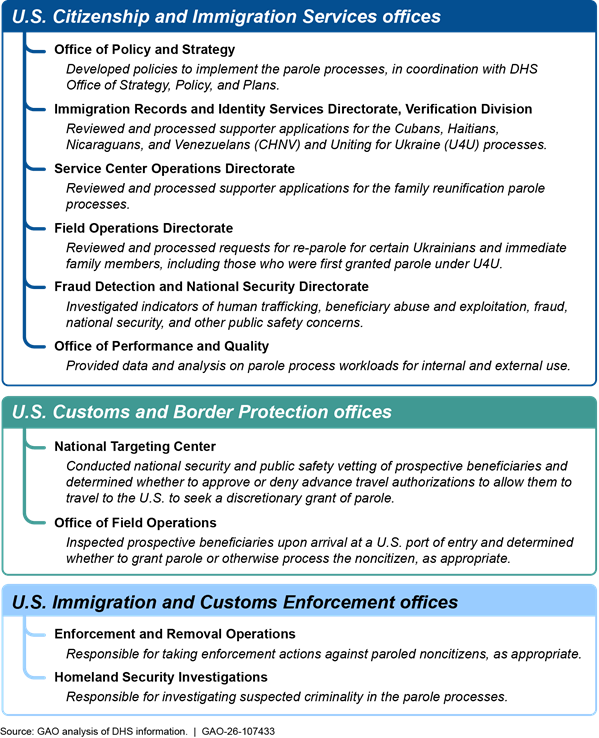

USCIS was responsible for reviewing supporter applications to determine whether they included sufficient evidence that the supporter had the means to financially support the prospective beneficiary and met other requirements (known as a confirmation). CBP was responsible for vetting eligible prospective beneficiaries, determining whether to authorize them to travel to the U.S., and considering them for a discretionary grant of parole upon their arrival.[6]

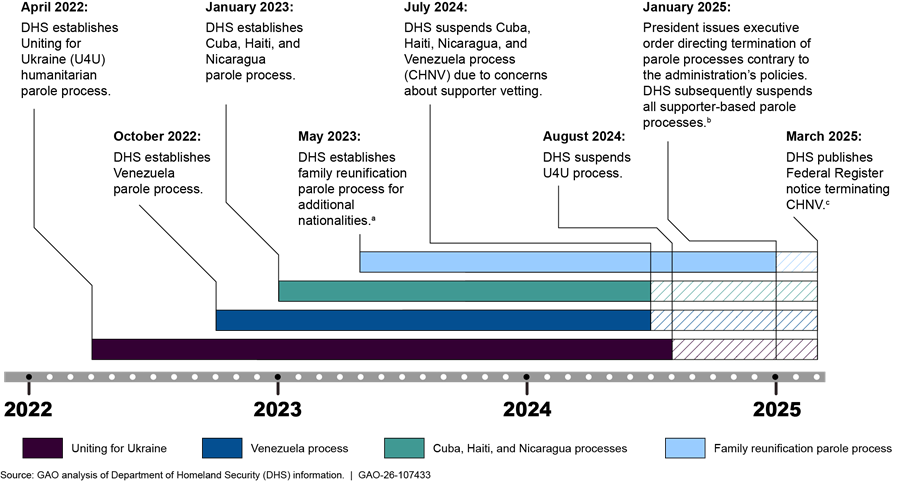

In July 2024, DHS suspended the CHNV and U4U processes after identifying issues related to supporter vetting, including security and fraud risks. On January 20, 2025, the President issued an executive order directing the termination of categorical parole processes if they were contrary to the policies of the administration.[7] Following this executive order, USCIS suspended the family reunification parole process and DHS terminated CHNV in March 2025.[8]

You asked us to review DHS’s administration and oversight of the supporter-based parole processes. This report examines DHS’s use of these processes since their inception in 2022. Specifically, this report addresses (1) what DHS data show about supporter-based parole processes; (2) challenges that existed in DHS’s implementation of the parole processes, and the extent to which DHS addressed them; and (3) DHS’s approach for taking enforcement actions against supporter-based parole beneficiaries, as appropriate.

To describe what DHS data show about supporter-based parole processes, we analyzed USCIS and CBP data from April 2022, when DHS initiated the first process, through January 2025, when DHS suspended the processes.[9] From USCIS, we obtained and analyzed data on supporter applications, including supporter demographic information, and USCIS decisions regarding these applications.[10] In addition, we obtained USCIS summary data on approvals of immigration benefits for which beneficiaries applied, such as employment authorization, lawful permanent resident status, and reparole.[11] From CBP, we analyzed record-level and summary data on grants of parole for the supporter-based processes.

To assess the reliability of USCIS and CBP data, we performed electronic tests; reviewed agency documentation, such as user guides and data dictionaries; and interviewed agency officials. We used this information to ensure we were interpreting and tabulating the data appropriately, and to rectify missing, duplicate, or erroneous data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting the characteristics and outcomes of supporter-based parole applications from 2022 to 2025.

To examine the challenges that existed in DHS’s implementation of the parole processes, and the extent to which DHS addressed them, we analyzed USCIS and CBP directives, memorandums, guidance, and training materials for implementing U4U, CHNV, and family reunification parole. We also reviewed USCIS and CBP internal assessments of these policies and procedures, including those related to the challenges components faced, recommendations developed, and actions taken to address the findings of these assessments. We assessed the information we obtained against leading practices for combating fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[12]

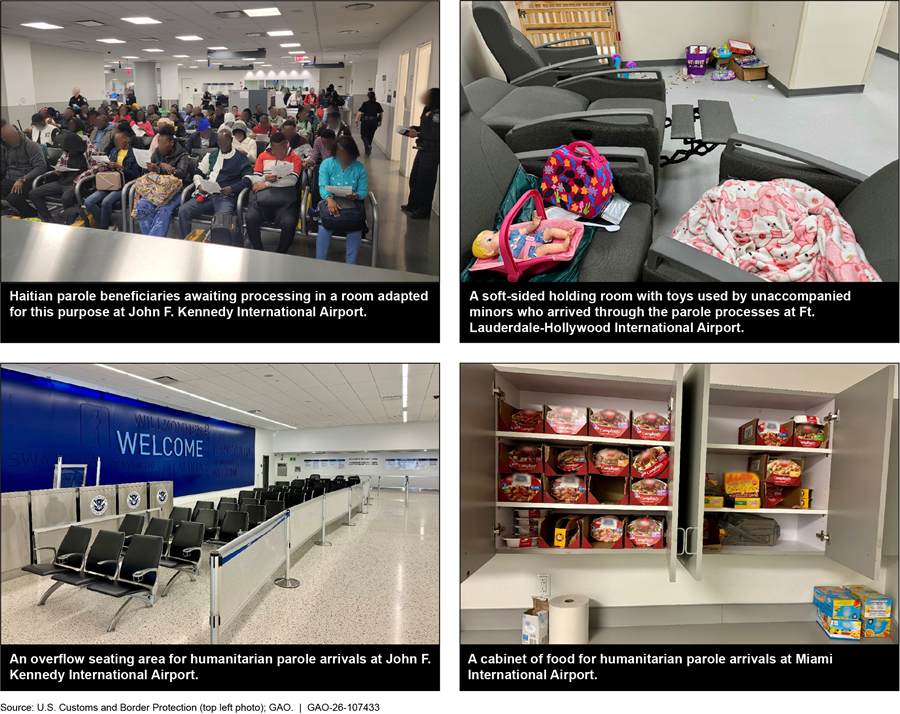

In addition, we interviewed USCIS and CBP headquarters and field office officials responsible for managing and implementing the parole processes. For example, we interviewed all USCIS staff permanently assigned to review U4U and CHNV supporter applications, as well as a nongeneralizable selection of eight USCIS staff temporarily assigned to review such applications (known as detailees) in calendar year 2024.[13] We also conducted site visits and interviewed CBP officers and supervisors at four airports to understand how CBP processed parole arrivals at ports of entry and any challenges experienced.[14] We assessed the information we obtained from USCIS and CBP regarding its implementation of parole processes, challenges, and actions taken to address such challenges against key practices for program management.[15]

To describe DHS’s approach for taking enforcement actions against supporter-based parole beneficiaries, we reviewed DHS and ICE policies governing immigration enforcement priorities. We also met with officials at ICE headquarters offices and field offices to understand ICE’s approach to taking enforcement actions against parole beneficiaries in accordance with DHS policies, including how its approach has changed over time.

For additional details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DHS’s Humanitarian Parole Authority

In the immigration context, parole provides official permission for a noncitizen to enter and stay temporarily in the U.S. under certain conditions. Pursuant to the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended, the Secretary of Homeland Security has discretionary authority to parole into the U.S. “any alien applying for admission . . . on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.”[16] Over time, DHS has generally interpreted “humanitarian” parole as related to urgent medical, family, and related needs, and “significant public benefit” parole as limited to individuals of interest for law enforcement purposes, such as witnesses to judicial proceedings.[17] We refer generally to the exercise of this parole authority as “humanitarian parole” throughout this report.

Humanitarian parole does not constitute an admission to the U.S., and DHS considers paroled noncitizens to be applicants for admission during their stay.[18] Parole is not an immigration status, and since it grants beneficiaries an authorized period of stay in the U.S., it is temporary in nature. However, a paroled noncitizen may apply for any immigration status for which they may otherwise be eligible while present in the U.S., which may allow them to stay in the U.S. pursuant to such lawful status.[19] Paroled noncitizens may apply for employment authorization, which allows them to work lawfully in the U.S. during their period of parole.[20] At the end of a noncitizen’s parole, they are generally to depart the U.S.[21] After the period of parole ends or parole is terminated, a paroled noncitizen may be placed in removal proceedings and ordered removed as appropriate.

Since the enactment of the parole authority, the federal government has used it in various ways. For example, prior administrations have paroled groups of noncitizens in response to emergent humanitarian situations. In the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. paroled in hundreds of thousands of Cuban and Southeast Asian refugees following the Cuban Revolution and the Vietnam War.[22] More recent administrations used parole for children orphaned by the 2010 Haiti earthquake and for relatives of current and former military servicemembers starting in 2010. Additionally, during and after the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, the U.S. granted parole to about 77,000 Afghan nationals under an effort called Operation Allies Welcome.

In recent years DHS granted parole to some noncitizens arriving at the southwest border who were found to be inadmissible, in some cases releasing them into the U.S. with a charging document known as a notice to appear, which when filed by DHS with the immigration courts, initiates full removal proceedings in immigration court.[23] These include noncitizens who made appointments to present themselves for inspection at ports of entry using the mobile application formerly known as CBP One.[24]

Establishment of Supporter-Based Parole Processes

From 2022 through 2024, DHS established and operated three different supporter-based parole processes, as shown in figure 1.

aThe family reunification parole process was established for Cubans in 2007 and for Haitians in 2015. In May 2023, DHS announced that it had updated the process and expanded it to include additional eligible individuals from Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. It codified the changes to the process in July and August of 2023. DHS further expanded the process to include eligible individuals from Ecuador in October 2023.

bExec. Order No. 14165, Securing Our Borders, 90 Fed. Reg. 8,467 (Jan. 30, 2025).

cDHS, Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, 90 Fed. Reg. 13,611 (Mar. 25, 2025). As of June 2025, U4U and family reunification parole remained suspended.

U4U. In April 2022, DHS established a new parole process to allow Ukrainians displaced by the war with Russia and their immediate family members to come to the U.S. for a period of up to 2 years. In the Federal Register notice implementing the process, DHS noted that Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had caused more than 5 million people to flee Ukraine for neighboring countries and resulted in shortages of food and medical supplies.[25] At the same time, DHS was experiencing an increased number of Ukrainians arriving at the southwest border, peaking at about 1,300 Ukrainian encounters per day in April 2022, according to a DHS report. DHS stated that it intended for the new parole process to provide an orderly pathway for Ukrainians to enter the U.S., thus deterring some from arriving at the southwest border.

One aspect of this process was DHS’s requirement that the noncitizen (the prospective beneficiary) have a supporter in the U.S. who agreed to receive them and provide for their basic needs for the duration of their parole period.[26] The supporter was to submit to USCIS an application to support the beneficiary, which if confirmed could ultimately allow the prospective beneficiary to receive advance travel authorization to travel to the U.S. and seek parole by CBP at a port of entry. We further discuss the steps and eligibility criteria for this and other parole processes later in this report.

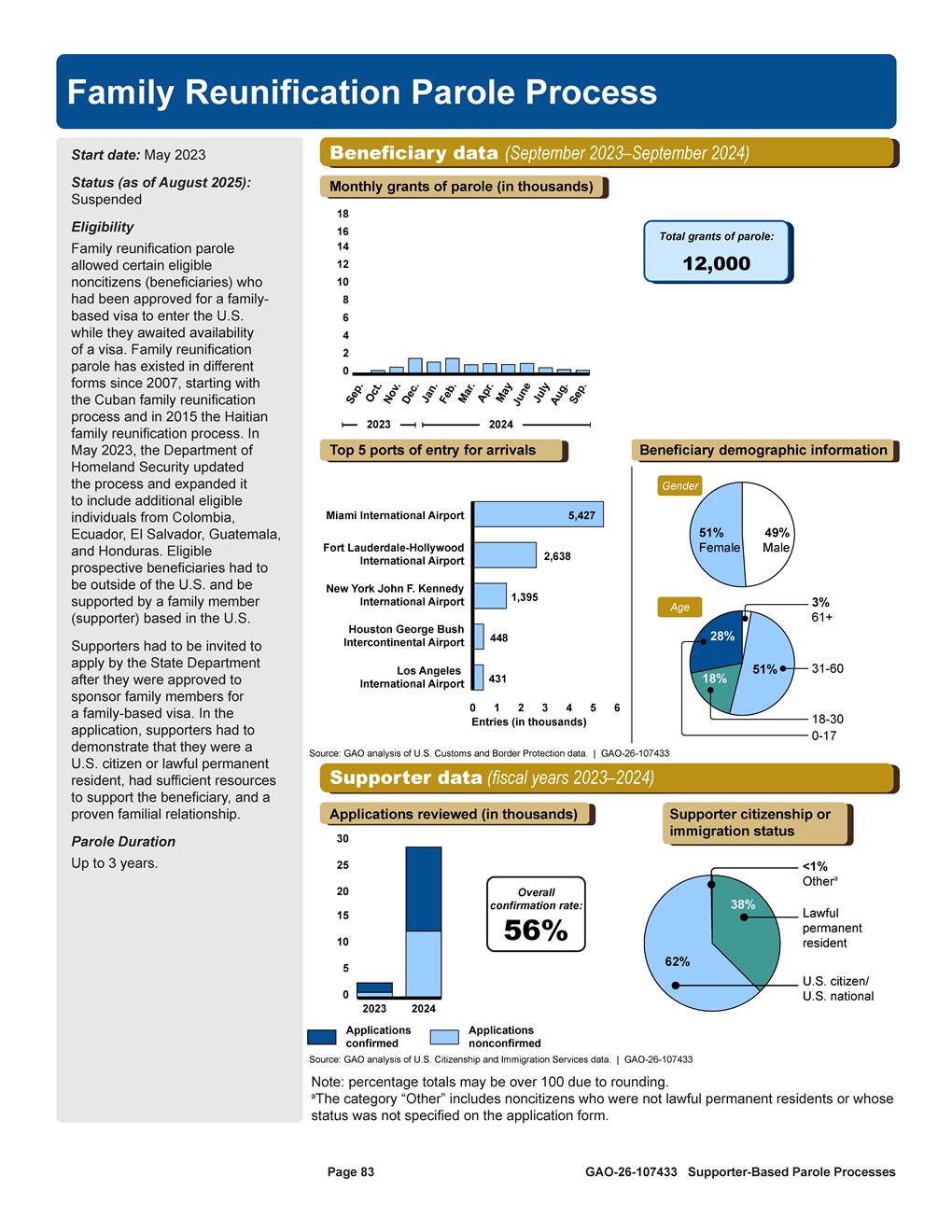

CHNV. In October 2022, DHS announced in a Federal Register notice that it was implementing a new parole process for Venezuelans using U4U as a model.[27] When establishing the process, DHS noted that, like Ukraine, Venezuela was experiencing a humanitarian crisis, in which repression, instability, and violence were pushing millions to leave the country. According to the Federal Register notice announcing the process, DHS had encountered a rising number of Venezuelans at the southwest border—for example, 33,000 encounters in September 2022, compared to a monthly average of 127 in fiscal years 2014 through 2019.

The Venezuelan process, like U4U, required a U.S.-based supporter to apply to support a Venezuelan beneficiary and agree to provide financial support for the parole period of up to 2 years. However, unlike Ukrainians, Venezuelans approved for an advance travel authorization were required to fly to an interior port of entry in the U.S. to request parole from CBP.[28] In addition, the Venezuelan process was initially capped at 24,000 total travel authorizations, while U4U had no such cap. DHS stated in the notice that the purpose of the Venezuelan process was to enhance border security by reducing the levels of Venezuelans arriving at the southwest border, while establishing an orderly pathway to lawfully enter the U.S.[29]

In January 2023, DHS announced additional parole processes for Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans and their immediate family members through Federal Register notices.[30] These new processes were modeled on the Venezuelan process and were functionally the same as that process, and together the four became known as the CHNV process. At the same time, DHS established a combined monthly limit of 30,000 advance travel authorizations for CHNV beneficiaries. Like U4U, the parole period for CHNV beneficiaries was up to 2 years. DHS’s stated purpose in the Federal Register notices for creating the CHNV process was similar to its rationale for creating U4U and the Venezuela process. Specifically, the countries involved were experiencing deteriorating humanitarian conditions, were among the top origin countries of noncitizens encountered at the southwest border, and posed challenges in DHS’s ability to remove and return their nationals without a lawful basis to enter or stay in the U.S.

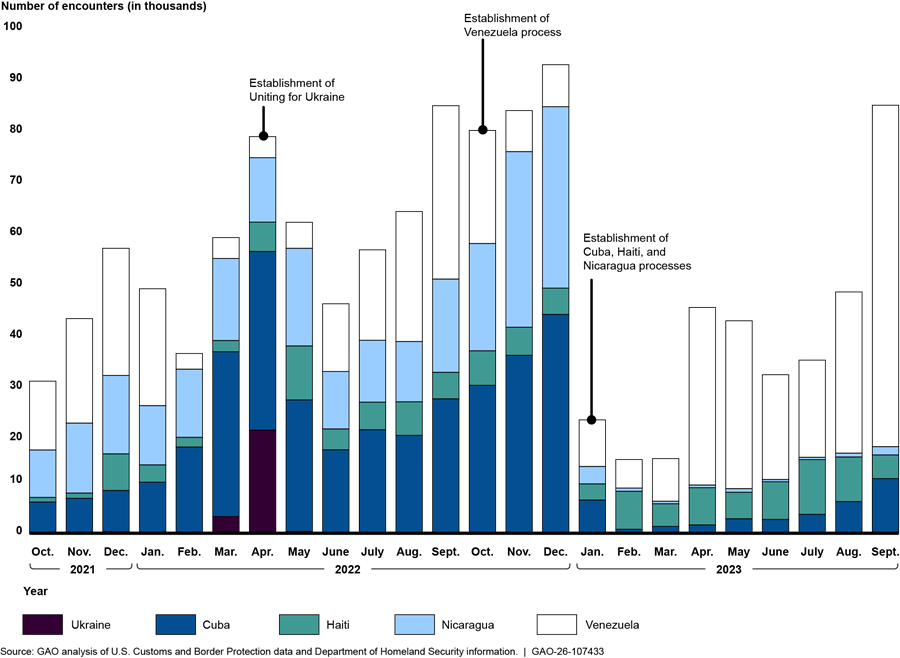

Figure 2 shows the numbers of nationals of U4U and CHNV countries encountered at the southwest border from October 2021 through September 2023, according to DHS data.

Figure 2: Southwest Border Encounters of Ukrainians, Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, October 2021–September 2023

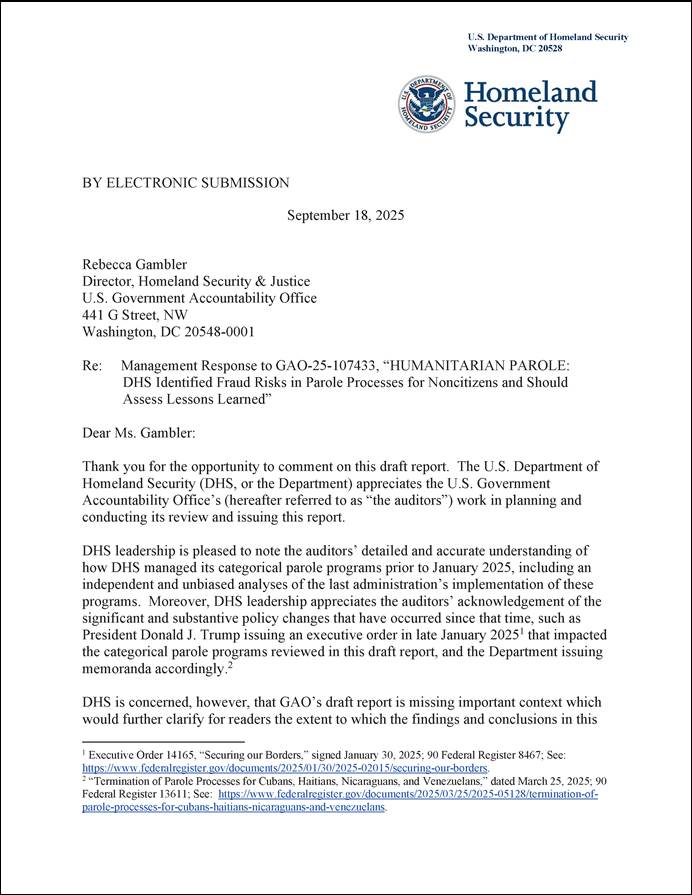

Family reunification parole. In addition to the new processes outlined above, in 2023 DHS updated and expanded its process for family reunification parole. This type of parole allowed certain eligible noncitizens who had been approved for a family-based visa to enter the U.S. while they awaited availability of a visa.[31] First established for Cubans in 2007 and Haitians in 2015, the family reunification parole process began when the State Department sent invitations to individuals who had filed immigrant visa petitions on behalf of family members outside of the U.S., allowing them to apply to USCIS for parole for their relatives. If approved for parole, the noncitizen family member would be allowed to live in the U.S. while waiting to receive a visa.

In 2023, DHS expanded the family reunification parole process to also include nationals of Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In addition, DHS incorporated elements of the CHNV process, such as requiring the beneficiary to be approved for an advance travel authorization to travel to the U.S. and request parole at a port of entry. Under the updated family reunification parole process, USCIS required the original petitioner to also serve as the supporter for the beneficiary. Each beneficiary was required to complete a medical exam while abroad by a panel physician—a doctor approved by the U.S. embassy—and attest to receiving medical clearance. The parole period for family reunification parole was up to 3 years. If an individual’s visa had not yet become available at the end of the parole period, they could request reparole.

Agency Roles and Responsibilities

Within DHS, three components had roles and responsibilities in administering the supporter-based parole processes: USCIS, CBP, and ICE. Various offices within the three components had specific responsibilities related to the supporter-based parole processes, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Offices’ Roles and Responsibilities Related to Supporter-Based Parole Processes

Steps in the Supporter-Based Parole Processes

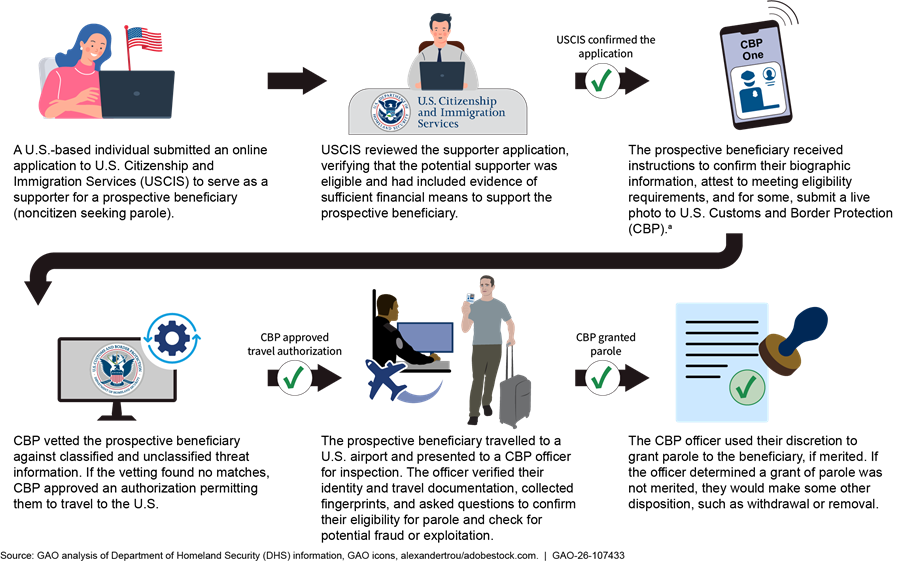

Figure 4 outlines the general steps in the supporter-based processes, starting with the supporter submitting an application to initiate the process and ending with the beneficiary receiving a grant of parole at a U.S. port of entry.

Note: The steps in the family reunification parole process differed from the steps in the Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV) and Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) processes in several ways. For example, family reunification parole beneficiaries were required to complete a medical exam by a panel physician—a doctor approved by the U.S. embassy—while abroad and submit the information electronically before USCIS transmitted beneficiary information to CBP for further vetting. This requirement did not exist for CHNV and U4U beneficiaries. In addition, only U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents who had previously applied and been approved for a family-based visa on behalf of the prospective beneficiary could serve as the supporter for family reunification parole, and only after receiving an invitation to apply.

aProspective beneficiaries under U4U did not use the CBP One application to submit a live photo or other information directly to CBP. Instead, these noncitizens confirmed their information in their USCIS account and USCIS then transmitted the information to CBP to complete the travel authorization process.

As shown in figure 4, there were generally six steps in DHS’s supporter-based parole processes.

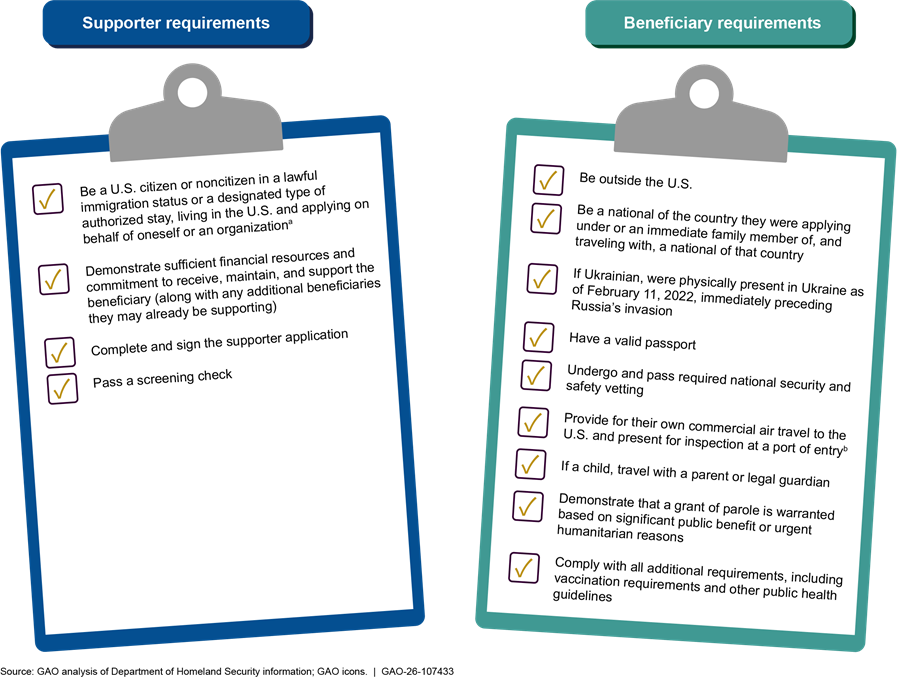

1. Potential supporter submitted an application to USCIS. A U.S.-based individual who committed to providing financial support to a beneficiary submitted a supporter application—Form I-134A, Online Request to be a Supporter and Declaration of Financial Support—to USCIS to initiate the process. The supporter application was entirely online and required the potential supporter to provide biographic information on themselves and the beneficiary, as well as evidence that they met eligibility requirements, as shown in figure 5. Supporters were allowed to support multiple beneficiaries, such as a family unit. However, they were required to submit a separate application for each beneficiary (including children). Supporters could submit applications on behalf of themselves or an organization. For family reunification parole, only the U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident who had previously applied and been approved for a family-based visa on behalf of the beneficiary could serve as the supporter, and only after receiving an invitation to apply.

2. USCIS reviewed the supporter application. USCIS screened the potential supporter and reviewed the application to ensure that they met the eligibility requirements, as shown in figure 5. If USCIS determined the potential supporter met all requirements, USCIS confirmed the application to move it to the next step.[32]

Figure 5: Eligibility Requirements for Supporters and Beneficiaries in the Supporter-Based Parole Processes

aThere were additional requirements for family reunification parole. For example, only the U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident who had previously applied and been approved for a family-based visa on behalf of the beneficiary could serve as the supporter, and only after receiving an invitation to apply. Further, prospective beneficiaries were required to complete a medical exam while abroad prior to completing their attestations.

bUniting for Ukraine beneficiaries were allowed to travel to the U.S. through a land border port of entry, whereas beneficiaries under the Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans and family reunification parole processes were required to travel by air to a U.S. airport.

3. Prospective beneficiary received instructions on next steps. Upon confirmation of their supporter, the prospective beneficiary received an email with instructions to create an online account to review and confirm their biographic information submitted to USCIS. In addition, this step required the noncitizens to attest to meeting the eligibility requirements, as shown in figure 5. After completing these attestations, prospective beneficiaries under CHNV and family reunification parole received instructions on accessing the CBP One mobile application, which they would then use to enter basic biographic information, scan their passport, and submit a live photo of themselves (a “selfie”) to CBP.[33]

4. CBP conducted beneficiary vetting and issued a travel authorization. CBP data systems processed beneficiary information for the purposes of conducting national security and public safety vetting. Specifically, CBP used an automated process to vet the biographic and biometric information against DHS and other federal databases for national security, border security, public health, and safety concerns. In addition, the National Vetting Center—a technology platform within CBP—vetted the biographic information against classified information on national security threats using support from other national security agencies. If the prospective beneficiary passed this vetting, CBP approved an advance travel authorization for them to travel to the U.S. and seek parole at a port of entry. The travel authorization was generally valid for 90 days. If the prospective beneficiary did not pass the vetting, CBP denied the request and the prospective beneficiary would not be allowed to travel.

5. The prospective beneficiary traveled to the U.S. and presented for inspection. Prospective beneficiaries were responsible for securing their own commercial air travel to the U.S. Upon arrival at a U.S. airport, prospective beneficiaries were individually inspected by a CBP officer and considered for parole. As part of the inspection, the noncitizens underwent additional screening and vetting. This included fingerprint biometric vetting and questioning to verify their eligibility for the parole process and identify any indicators of fraud, exploitation, or security concerns.

6. CBP granted parole or some other disposition. CBP granted parole if the beneficiary passed CBP screening and vetting and the officer determined that they merited parole, allowing the individual to stay in the U.S. for up to 2 years (U4U and CHNV) or up to 3 years (family reunification parole).[34] If CBP determined that the noncitizen posed a national security or public safety threat or otherwise did not warrant a grant of parole, CBP processed them for return to their country or removal proceedings.[35]

Suspension and Termination of Parole Processes

In summer 2024, DHS suspended the CHNV and U4U processes after identifying issues related to supporter vetting, including security and fraud risks. DHS later implemented additional vetting procedures and continued to approve some advance travel authorizations and grant parole for small numbers of noncitizens with a focus on cases already in process. For example, under CHNV, about 50 noncitizens were granted parole in November 2024 and 20 in December 2024, according to CBP documentation.[36]

In January 2025, the President issued an executive order directing DHS to terminate all categorical uses of parole that were contrary to the administration’s policies, specifically naming the CHNV processes.[37] In March 2025, DHS issued a notice in the Federal Register announcing that it was terminating the CHNV processes and terminating parole for beneficiaries already in the U.S. under CHNV, stating that all active grants of parole would expire 30 days from the date of the notice.[38] In April 2025, a federal district court issued a preliminary injunction that stayed several aspects of the Federal Register notice that sought to terminate parole, thereby keeping these provisions from taking effect.[39] In May 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court granted DHS’s application to stay the district court’s April injunction, and in doing so allowed the Federal Register notice to take effect, pending further litigation.[40]

Fraud Risk Framework

Executive branch agency managers who implement programs and activities, such as the supporter-based parole processes, are responsible for managing fraud risks and implementing practices for combating those risks. The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating the likelihood and effects of fraud.

In 2015, we issued A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework), a comprehensive set of leading practices that serves as a guide for combating fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[41] GAO created this framework to help federal program managers strategically manage their fraud risks. The framework describes leading practices for:

1. Committing to combating fraud by establishing an organizational structure and culture that are conducive to fraud risk management,

2. Assessing fraud risks by conducting regular fraud risk assessments and determining a fraud risk profile,

3. Designing and implementing antifraud activities to prevent and detect potential fraud, and

4. Monitoring and evaluating antifraud activities to help ensure they are effectively preventing, detecting, and responding to potential fraud.

In 2022, we reviewed USCIS’s agency-wide fraud detection operations for the immigration benefits it adjudicates.[42] We found that USCIS did not have a process for regularly conducting fraud risk assessments, as the Fraud Risk Framework calls for. In addition, we found that although USCIS had documented some of its antifraud activities, it had not developed an agency-wide antifraud strategy nor evaluated the effectiveness of its antifraud activities. We concluded that by taking a more strategic and risk-based approach to managing fraud risks, USCIS could better ensure its antifraud efforts are effective and efficient.

We made six recommendations to USCIS, including that it develop and implement processes for (1) regularly conducting fraud risk assessments, (2) documenting fraud risk profiles, (3) developing and regularly updating an antifraud strategy, and (4) evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of antifraud activities. USCIS agreed and has taken some steps to address our recommendations, such as developing a draft framework for how it plans to conduct fraud risk assessments and develop fraud risk profiles. As of June 2025, these four recommendations remained open.[43]

Our work has also found that programs created or expanded in response to emergencies may be at increased risk for fraud.[44] Building on this work as well as the Fraud Risk Framework, in 2023 we issued A Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs to help federal agencies better manage improper payment risk during emergencies.[45] According to this framework, when the federal government provides emergency assistance, the risk of improper payments—such as fraudulent payments—may be higher because the need to provide such assistance quickly can detract from the planning and implementation of effective controls. The framework provides principles and leading practices for program managers to better plan for and take a strategic approach to managing improper payments in emergency assistance programs—before and during emergency situations. Although the framework is focused on financial assistance programs, many of the guiding principles and practices can be similarly applied to programs that provide a non-financial benefit, such as obtaining entry into the U.S. through parole.

DHS Granted Supporter-Based Humanitarian Parole to About 774,000 Beneficiaries from May 2022 Through September 2024

CBP Granted Supporter-Based Parole to About 774,000 Beneficiaries

Our analysis of CBP data found that CBP granted parole to about 774,000 noncitizen beneficiaries from May 2022 when noncitizens began arriving under the supporter-based parole processes through September 2024. Of these beneficiaries, 69 percent were granted parole through CHNV, 30 percent through U4U, and just under 2 percent through family reunification parole, as shown in figure 6.[46]

Figure 6: CBP Grants of Parole Under the CHNV, Uniting for Ukraine, and Family Reunification Parole Processes, May 2022–September 2024

Note: The percentage total is over 100 due to rounding.

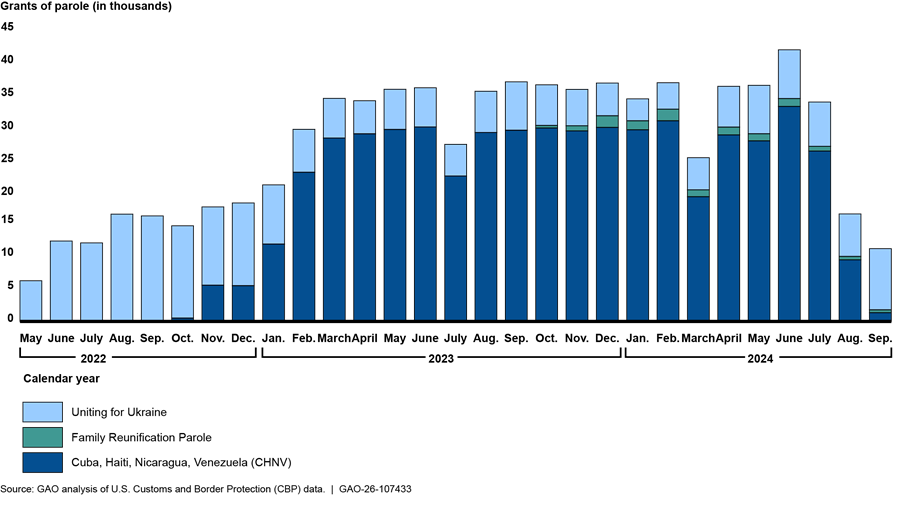

As shown in figure 7, the relative number of paroles CBP granted each month varied over time as DHS introduced new parole processes. For example, noncitizen arrivals to the U.S. through U4U began in May 2022, resulting in about 6,000 grants of parole that month. However, starting in January 2023, CHNV beneficiaries made up the largest number of grants of parole each month through August 2024. From January 2023 through August 2024, CBP granted humanitarian parole to about 26,000 beneficiaries per month through the CHNV process.[47] After August 2024, CBP substantially decreased its grants of parole after it suspended the issuance of travel authorizations in summer 2024.

Figure 7: Monthly CBP Grants of Parole Under the CHNV, Uniting for Ukraine, and Family Reunification Parole Processes, May 2022–September 2024

With respect to individual countries, across all three parole processes, beneficiaries from Ukraine made up the largest group (30 percent), followed by Haiti (28 percent), Venezuela (15 percent), Cuba (15 percent), and Nicaragua (12 percent).[48] For additional data on the humanitarian parole processes for each country, see appendix II.

Prior to traveling to the U.S. to request a grant of parole, prospective beneficiaries were required to undergo vetting and receive travel authorization from CBP. From April 2022 through September 2024, CBP received about 917,000 advance travel authorization requests under U4U, CHNV, and family reunification parole. Of these travel authorization requests, CBP approved 91 percent (about 833,500) and cancelled or denied 7 percent (about 61,000).[49]

Prospective beneficiaries with approved advance travel authorizations could fly to a U.S. port of entry to request parole from CBP. From May 2022 through September 2024, the approximately 774,000 noncitizens who were granted parole through CHNV, U4U, and family reunification parole arrived at U.S. airports across the country.[50] However, 88 percent of beneficiaries (nearly 685,000 individuals) arrived at 10 U.S. airports, as shown in figure 8. In particular, two south Florida airports—Miami International Airport and Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport—accounted for over half of all parole beneficiary arrivals and grants of parole (about 436,000 individuals).[51]

Figure 8: Top 10 Arrival Airports for CBP Grants of Parole Under the CHNV, Uniting for Ukraine, and Family Reunification Parole Processes, May 2022–September 2024

Based on our review of CBP data, CBP officers generally collected the intended address of the noncitizens and entered the information into CBP data systems. Our analysis of these data found that the distribution of beneficiaries’ arrival location generally aligned with their intended address. For example, 40 percent of all humanitarian parole beneficiaries—about 300,000 beneficiaries—indicated Florida as their intended state of residence.[52]

According to CBP officers we spoke to at four selected U.S. airports, CBP officers denied parole to a small number of noncitizens under the supporter-based processes and granted parole to most noncitizens who arrived at U.S. airports with a valid travel authorization.[53] Our review of a selection of CBP data also found that most noncitizens who arrived at two high-volume airports with a valid travel authorization were granted parole. Specifically, in calendar year 2023, CBP granted humanitarian parole to about 99 percent of arrivals at the two Florida airports that accounted for over half of all humanitarian parole arrivals that year.[54] Those who were not granted parole under the supporter-based parole processes were either denied entry to the U.S. or were permitted to enter the U.S. with a disposition other than humanitarian parole, such as being issued a notice to appear for removal proceedings before the immigration courts. See the text box for examples of arrivals who were denied entry into the U.S. or were permitted into the country with a disposition other than humanitarian parole.

|

Examples of How CBP Processed Arriving Noncitizens it Denied Humanitarian Parole at U.S. Airports According to CBP officials, CBP granted humanitarian parole to most noncitizens who arrived at U.S. airports with a valid advance travel authorization under the Uniting for Ukraine (U4U); Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, Venezuela (CHNV); and family reunification parole processes. However, CBP denied humanitarian parole to a small percentage of arriving noncitizens. In some cases, the individual was given the opportunity to withdraw their application for admission to the U.S. and board a plane back to their country of origin. In other cases, CBP placed the noncitizen in expedited removal or allowed them to enter the country with a disposition outside of humanitarian parole. In expedited removal proceedings, the government can order noncitizens removed from the U.S. without further hearings before an immigration judge unless they indicate an intention to apply for asylum, a fear of persecution or torture, or a fear of return to their home country. The following are examples of such cases. Withdrawal In 2024 a Venezuelan adult admitted under oath to CBP officers that he had paid an individual $15,000 to file supporter applications for him and his two children. The individual withdrew his application—and the application for his children—for humanitarian parole. CBP officers at two ports we visited told us that when they encountered individuals with potentially fraudulent cases, they would first offer them the option to withdraw the application prior to taking other steps, such as referring them to U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for possible enforcement action, such as detention and removal. Port Parole In 2023, a Venezuelan adult arrived at a port of entry with an expired advance travel authorization (humanitarian parole travel authorizations were generally valid for 90 days after approval). The individual’s travel authorization had been expired for about a week. CBP officers conferred with CBP’s National Targeting Center, which is responsible for vetting parole applicants, and ultimately granted humanitarian parole to the individual under the port’s discretion to grant parole rather than through CHNV. Specifically, CBP officers had the discretion to grant humanitarian parole at ports of entry (referred to as a “port parole”). In such port parole cases, CBP officers generally set the parole period to 2 years. Notice to Appear In 2024 an adult from Nicaragua admitted under oath to CBP officers that he did not know his supporter and that his sister had paid the supporter $5,500 to submit an application to support him. CBP officers referred the individual to ICE for detention and removal. However, the individual claimed fear of returning to Nicaragua, and ICE did not have detention space available to hold the individual for a credible fear interview with an asylum officer. As such, CBP released the individual into the U.S. with a notice to appear in immigration court at a later date. Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) information. | GAO‑26‑107433 |

Across the supporter-based parole processes, certain characteristics of beneficiaries were relatively similar. For example, the age breakdown of beneficiaries was similar across the parole processes. In total, the largest share of beneficiaries were adults aged 18 to 60 (73 percent). About 20 percent of beneficiaries were minors (aged 0 to 17 at the time of arrival), and around 7 percent were older than 60. The gender breakdown of beneficiaries was nearly equal, with about 53 percent female arrivals and 47 male arrivals. In addition, over 99 percent of beneficiaries were citizens of the 10 countries eligible for parole. Less than 1 percent were citizens of other countries. According to the rules of these parole processes, humanitarian parole was available to nationals of the eligible countries (such as Cuba and Nicaragua) as well as their immediate family members of any nationality.[55]

USCIS Confirmed More Than 1 Million Supporter Applications

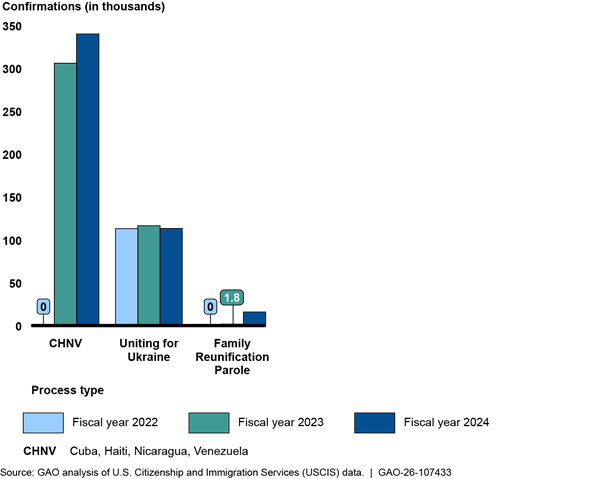

From April 2022 through September 2024, USCIS confirmed over 1 million supporter applications, as shown in figure 9. Of these confirmations, 64 percent were associated with the CHNV parole process, 34 percent with U4U, and 2 percent with family reunification parole.

|

Why Are There More Supporter Confirmations Than Grants of Parole to Beneficiaries? Based on our analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data through September 2024, there were about 230,000 more confirmed supporter applications than grants of parole. Several factors may have contributed to this difference. For example, according to USCIS officials, prospective beneficiaries had to take additional steps after USCIS confirmed a supporter’s application—such as sign an attestation—before they were able to request authorization to travel to the U.S., and some did not take these steps. Additionally, CBP did not authorize all prospective beneficiaries to travel to the U.S. For example, CBP denied or cancelled about 61,000 requests. For instance, if CBP initially approved a prospective beneficiary’s travel authorization but subsequently identified derogatory or other disqualifying information, it was to cancel the travel authorization. Further, of the over 800,000 CBP-approved travel authorizations, about seven percent of prospective beneficiaries never traveled to the U.S. Source: GAO analysis of USCIS and CBP information. | GAO‑26‑107443 |

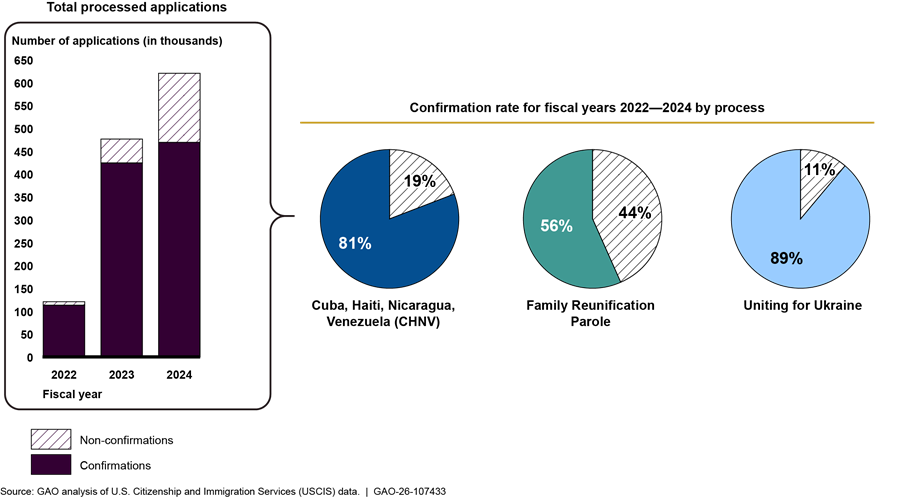

Out of about 1.2 million supporter applications USCIS reviewed across the processes from April 2022 through September 2024, USCIS did not confirm about 210,000 supporter applications—a nonconfirmation rate of about 17 percent.[56] As shown in figure 10, USCIS confirmed supporter applications at a lower rate over time. Specifically, in fiscal year 2022, USCIS’s confirmation rate was about 95 percent. In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, the confirmation rate was about 90 and 75 percent, respectively. Additionally, USCIS’s confirmation rate varied across processes, as shown in figure 10. For example, U4U had the highest confirmation rate (almost 90 percent), while family reunification parole had the lowest (about 55 percent).[57]

Figure 10: USCIS Supporter Confirmations and Nonconfirmations by Fiscal Year and Humanitarian Parole Process, April 2022–September 2024

Across all supporter-based humanitarian parole processes, supporter applicants who self-reported being U.S. citizens, U.S. nationals, and lawful permanent residents accounted for most applications confirmed by USCIS.[58] Specifically, 68 percent of all confirmed applications were submitted by those reporting to be U.S. citizens and nationals, and 22 percent were submitted by lawful permanent residents. The remaining 11 percent of confirmed applications were submitted by noncitizens who were not lawful permanent residents or whose status was not specified on the application form.[59]

Most Parole Beneficiaries Received Employment Authorization and Some Have Adjusted Their Immigration Status

Upon receipt of a grant of parole, beneficiaries were permitted to apply for employment authorization and any other immigration benefits for which they were eligible. According to USCIS records, most humanitarian parole beneficiaries applied for, and received, federal government authorization to work in the U.S. Specifically, as of March 2025, USCIS had issued over 800,000 employment authorization documents to beneficiaries of CHNV and U4U.[60]

In addition, as of March 2025, some humanitarian parole beneficiaries had applied for, and received, lawful immigration status from USCIS, as shown in table 1.[61] Such lawful immigration status included the following:

· Temporary protected status (TPS). This form of humanitarian protection provides eligible noncitizens who are from designated countries and residing in the U.S. temporary protection from removal and allows them to work in the country.[62]

· Asylum. This provides humanitarian protection to noncitizens who demonstrate that they are unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.[63]

· Adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident. The Immigration and Nationality Act and certain other federal laws provide different ways to adjust the immigration status to that of a lawful permanent resident.[64] This is often informally referred to as applying for a green card. Family-based immigration and adjustment of status under the Cuban Adjustment Act fall within this category.[65]

Table 1: USCIS Approvals of Applications for Other Immigration Status Made by Humanitarian Parole Beneficiaries, as of March 2025

|

Country |

Temporary Protected Status (TPS)a |

Adjustment of status to lawful permanent residentb |

|

Cuba |

0 |

14,180 |

|

Haiti |

62,436 |

1025 |

|

Nicaragua |

30c |

283 |

|

Ukraine |

85,105 |

4,209 |

|

Venezuela |

33,955 |

463 |

|

Total |

181,526 |

20,160 |

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). | GAO‑26‑107433

Notes: USCIS also approved 70 applications for asylum. Asylum provides humanitarian protection to noncitizens who demonstrate that they are unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. 8 U.S.C. § 1158.

In February 2025, USCIS placed an administrative hold on all benefit requests filed by beneficiaries of the supporter-based parole processes, pending further screening and vetting by USCIS. This memorandum was stayed by a district court in May 2025. See Doe v. Noem, No. 25-CV-10495 (D. Mass. May 28, 2025) (order granting in part plaintiffs’ emergency motion for preliminary injunction and stay of administrative action).

aTPS provides eligible foreign nationals who are from designated countries and residing in the U.S. temporary humanitarian protection from removal. Countries may be designated for TPS because of temporary conditions in the country, such as armed conflict, that prevent nationals from returning in safety.

bThe Immigration and Nationality Act and certain other federal laws provide many different ways to adjust status to that of a lawful permanent resident. See, for example, 8 U.S.C. § 1154. Family-based immigration falls within this category.

cNicaraguan parole beneficiaries were not eligible for TPS. However, according to USCIS officials, individuals may have received parole through a process for one country and been granted TPS as a citizen of another country. For example, in one case, a Venezuelan citizen who had been living in Nicaragua was granted parole under the Nicaraguan process. This individual subsequently applied for TPS as a Venezuelan citizen after entry to the U.S.

Some paroled noncitizens were also able to remain in the U.S. after their initial period of parole had ended by obtaining reparole.[66] In February 2024, USCIS began accepting reparole applications for certain Ukrainians and their immediate family members originally paroled into the U.S. on or after February 11, 2022, including those paroled under U4U. Family reunification parole beneficiaries were also eligible to apply for a new period of parole through USCIS.[67] DHS did not establish a reparole process for CHNV beneficiaries. As of March 2025, USCIS had processed 75 percent (about 87,500) of the approximately 117,000 reparole applications U4U beneficiaries had submitted.[68] USCIS approved more than 99 percent (about 87,200) of the processed applications, granting such beneficiaries a new period of parole, and denied less than 1 percent (about 250).

DHS Identified Fraud Risks and Other Challenges in Supporter-Based Parole Processes but Has Not Assessed Lessons Learned

DHS Identified Security and Fraud Risks Early in Parole Processes but Has Not Developed a Plan for Internal Controls

USCIS and CBP began identifying fraud risks and other vulnerabilities in the U4U process shortly after it was initiated in April 2022 and identified risks in the CHNV process once implementation began.[69] Subsequently, a USCIS review determined that fraud indicators were widespread in CHNV and U4U, and DHS suspended the processes. These risks were the result of insufficient internal controls in the supporter vetting process, such as activities to verify supporter information, according to USCIS and CBP documentation. DHS has since terminated CHNV and suspended the other processes after briefly restarting them with additional vetting measures in place. However, it has not developed a plan it could use in the future to help proactively mitigate fraud risk and other risks in new or changed programs.

DHS’s Rapid Implementation of the Processes Raised Early Concerns

DHS developed and implemented the U4U process in a period of about 2 months in early 2022, according to USCIS officials. DHS developed the process quickly to respond to the emerging humanitarian crisis in Ukraine following Russia’s invasion, these officials said, leveraging electronic tools to help bring displaced Ukrainians seeking safety to the U.S. in a timely manner. Specifically, USCIS officials said that DHS had learned from its previous experience administering parole for Afghans under Operation Allies Welcome in 2021, which the officials described as time consuming. In developing U4U, DHS aimed to process individuals more quickly. To do so, it adapted CBP’s advance travel authorization process and created an online supporter application, officials said.[70] DHS’s Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans led the department’s initial development of U4U and worked with CBP and USCIS to implement it, according to DHS and USCIS officials.

Officials with USCIS’s Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS), the agency’s antifraud entity, told us that while USCIS was developing U4U, FDNS did not have the opportunity to identify potential risks in the process and suggest ways to mitigate them. Shortly after U4U’s establishment in April 2022, FDNS became aware of suspected human trafficking cases associated with the process and FDNS’s role in the parole processes expanded. For example, in June 2022, FDNS established a dedicated email inbox to receive referrals from the Department of Health and Human Services involving human trafficking reports from Ukrainian beneficiaries and developed a set of questions that human trafficking hotline staffers could use for potential Ukrainian victims.[71]

After DHS implemented the processes for Venezuela and the other CHNV countries beginning in the fall of 2022, FDNS began receiving referrals of potential fraud from CBP and from within USCIS related to the processes. For example, CBP referred fraud schemes that officials encountered at ports of entry, such as non-Ukrainians using fraudulent travel documents and fake marriage arrangements to try to enter the U.S. under U4U. Additionally, CBP officers at one south Florida airport determined that some Haitian beneficiaries traveling with children had been scammed by some Haitian officials to purchase a fraudulent guardianship document. Within USCIS, a team responsible for validating supporter and beneficiary A-numbers noticed that some CHNV applications appeared to be fraudulent.[72] In February 2023, this team referred to FDNS a group of suspicious supporter applications, including some with missing or unverifiable proof of identity, nonexistent addresses and phone numbers, and documentation that appeared to be altered.

In response to these incidents, FDNS officials investigated the referrals, made recommendations to nonconfirm supporter applications where appropriate, and shared information about fraud schemes and trends to help USCIS reviewers identify potential fraud. For example, FDNS created a tip sheet for USCIS reviewers to help them identify fraud indicators in supporter applications. FDNS also referred cases with suspected criminal activity, such as potential human trafficking, to ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations. FDNS officials said that several investigations remained ongoing as of June 2025.

DHS Identified Widespread Indicators of Fraud Among Supporters

In 2024, USCIS and CBP took additional actions to identify and assess fraud risks in the U4U and CHNV processes, determining that fraud indicators were widespread in the CHNV and U4U processes. Both agencies began taking action to mitigate the risks they identified.

USCIS. In early 2024, FDNS officials became increasingly concerned about the prevalence of fraud in CHNV and U4U, these officials said. In response, FDNS analyzed all 2.6 million supporter applications that USCIS had received, including those already processed (confirmed and nonconfirmed), to identify broader trends and vulnerabilities that made the processes susceptible to fraud.

|

Example Fraud Indicator: Counterfeit or Altered Documents Using U.S. Citizen Identities Individuals who filed fraudulent supporter applications sometimes used information and altered documents that belonged to real U.S. citizens or fabricated identities altogether, according to analysis by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ (USCIS) Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS). Some fraudulent documents showed clear indications that they had been altered. FDNS found that filers submitted more than 3,000 forms with images of fraudulent U.S. passports. In some cases, filers used the identities of unwitting U.S. citizens and altered document images to include different photos, according to FDNS documentation. Notable examples include a passport image with a photo of journalist Connie Chung and a driver’s license with a photo of actor Cote de Pablo. In addition, USCIS determined that some filers were using Social Security numbers and other biographical information associated with deceased individuals. For example, FDNS identified multiple applications using a Social Security number that had belonged to Elvis Presley along with other fake biographical data. As of July 2024, more than 1,400 beneficiaries had arrived in the U.S. whose supporter information was associated with a deceased individual, FDNS found. According to FDNS, prior to its involvement, USCIS reviewers generally confirmed these supporter applications because they did not have the ability to verify information about U.S. citizen supporters who did not have a prior USCIS filing history. Source: GAO analysis of USCIS documentation. | GAO 26 107433 |

FDNS officials told us the analysis found that fraud indicators were widespread in CHNV and U4U supporter applications. FDNS’s analysis identified several fraud indicators among the applications, such as supporter information belonging to deceased individuals, counterfeit or altered documents, clearly irrelevant evidence (see fig. 11), and thousands of applications with at least one piece of fictitious supporter information. FDNS also found that applications included Social Security numbers, phone numbers, physical addresses, and email addresses that had been used hundreds of times.

|

Example Fraud Indicator: Shell Applications Used to Scam Potential Parole Beneficiaries Some filers under Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) and Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV) submitted supporter applications with fraudulent and incomplete information solely for the purpose of exacting a fee from the prospective beneficiaries—rather than to establish their ability to serve as supporters. Paying filers to submit a supporter application was prevalent across the U4U and CHNV processes, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ (USCIS) Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS). These “shell applications” lacked key evidence and were unlikely to be confirmed by USCIS reviewers. For example, some shell applications contained clearly irrelevant documents as evidence of employment and financial means (see fig. 11). To confirm a supporter application, USCIS required that the application include evidence that the supporter had sufficient financial means to provide for the beneficiary. In addition, hundreds of applications contained fictitious supporter information or nonsensical text in response to narrative questions. In other cases, applications appeared legitimate enough for USCIS reviewers to confirm them and the beneficiaries eventually received authorization to travel to the U.S., according to an FDNS report. For example, FDNS reported that one Ukrainian beneficiary paid about $5,000 to a filer for an application that USCIS later confirmed. In addition, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers at some ports of entry told us they had encountered prospective beneficiaries who said they had paid their supporter to file the application, in which case the officers would not grant them parole due to the likelihood of fraud. USCIS officials told us that because there was no statutory provision prohibiting the payment of fees to the supporter in exchange for submitting the form, USCIS lacked the authority to take enforcement action against supporters who solicited or accepted fees. Source: GAO analysis of USCIS and CBP information. | GAO 26 107433 |

FDNS officials also identified some fraud indicators among family reunification parole supporter applications. For example, some confirmed applications were associated with petitioners who had died, FDNS officials said. For family reunification parole, USCIS required the individual who filed the supporter application to be the same person who filed the original petition for the beneficiary’s family-based immigrant visa (to whom the Department of State sent the parole invitation). However, some invitations to apply were sent to deceased petitioners, FDNS found. These invitations resulted in 728 supporter applications filed under the names of deceased individuals—of which USCIS confirmed half. FDNS officials told us there may be reasons other than fraudulent activity why someone might apply under a deceased petitioner’s name. For example, if the original petitioner passed away, a family member may have filed under their name because the visa applicant still wanted to come to the U.S. and the family member did not realize they were not permitted to file the application.

CBP. Separately, starting in July 2024, CBP’s National Targeting Center (NTC) conducted its own review of confirmed CHNV supporter information and found instances of supporters with a criminal history. NTC first reviewed a subset of supporters of Venezuelan beneficiaries by vetting their information against information on national security and public safety threats (derogatory holdings).[73] NTC found that about 25 percent of the supporters were potential matches against this information. Upon manual review, about 18 percent of the supporter subset were found to be true matches, meaning that CBP likely would have found the beneficiary not eligible for parole had the information about the supporter been known during the review process, according to NTC.

In light of these vulnerabilities, NTC suspended its automated process to vet beneficiaries and approve advance travel authorizations for CHNV in July 2024 and for U4U in August 2024. USCIS then suspended its review of new supporter applications, effectively pausing these two supporter-based parole processes at that time.[74]

After pausing the travel authorization process, NTC expanded its vetting efforts to include the supporters of CHNV beneficiaries who had approved travel authorizations but had not yet arrived in the U.S. NTC also began working with officials from FDNS on these vetting efforts. Using CBP derogatory holdings, NTC and FDNS jointly vetted supporter information associated with about 29,000 “travel ready” beneficiaries. Of these, they found that about 5,300 had supporters that matched against derogatory information, and 2,800 had supporters who were ineligible. In total, NTC canceled travel authorization for about 8,100 beneficiaries, about 28 percent of the “travel ready” population. Matches identified a range of illicit activity by supporters, such as illegal narcotics, money laundering, and assault, according to NTC documentation (see text box for examples). Where they encountered evidence of criminality or ineligibility to be a supporter, NTC and FDNS officials took enforcement steps as appropriate, such as canceling travel authorization for beneficiaries who had not yet traveled or referring cases to law enforcement agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation or ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations.

|

Example Security Risk: Prior Criminality Found Among Confirmed Supporters When the National Targeting Center (NTC) reviewed information on a subset of confirmed supporters of Venezuelan prospective beneficiaries against derogatory holdings, they found that about 25 percent had matches that required manual review and 18 percent resulted in true matches. According to NTC documentation, the vetting identified potential or confirmed criminal activity among the supporters that may have made the prospective beneficiaries ineligible for a grant of parole. NTC expanded its vetting to include supporters of prospective beneficiaries in the Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV) process who had approved travel authorizations but had not arrived in the U.S. The vetting resulted in similar findings of potential or confirmed criminal activity, for example · some supporters had links to investigations related to illegal narcotics and money laundering activity; · some supporters had criminal records, including felony arrests for assault and battery, robbery, arrest for conspiracy to sell cocaine, suspected involvement in a transnational criminal organization, and smuggling; · one supporter—who had applied to support a minor child—had a warrant, arrest, or conviction involving an attempt to procure online child sexual exploitation materials on two occasions; and · another supporter, a U.S. citizen, was wanted for murder and assault with a firearm by Haitian authorities. NTC and the Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS) reviewed each case and determined what actions to take based on a risk assessment, such as canceling the travel authorization for the beneficiary or making a referral to an appropriate law enforcement agency. In other cases, NTC and FDNS determined that the matches did not present a significant enough risk to warrant canceling the travel authorization or nonconfirming the supporter, such as one supporter who had been charged with loitering. Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and U.S. Customs and Border Protection information. | GAO 26 107433 |

USCIS Has Not Developed an Internal Control Plan to Address Future Vulnerabilities

|

What Are Internal Control Activities and Why Are They Important? Internal control activities are actions program managers establish through policies and procedures to achieve objectives and respond to risks. Control activities serve a range of purposes, one of which is to prevent, detect, and respond to fraud risks. Effective managers design antifraud control activities that are tailored to known fraud risks in the program. Examples may include fraud-awareness training for staff or automated data-analytic techniques to prevent fraudulent applications from being approved. Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107433 |

USCIS and CBP assessments attributed the risks they identified in the parole processes to insufficient internal control activities in the supporter application process. While DHS has terminated the CHNV processes and suspended the other parole processes, USCIS has not developed an internal control plan that it could leverage for new or changed programs in the future to quickly implement control activities to help prevent fraud before it occurs, according to USCIS officials.

Agencies are to use internal control activities to prevent fraud in their programs. However, a July 2024 USCIS report found that there was “little to no barrier to entry” to file the supporter application, contributing to the fraud risks and potential exploitation that had occurred. The report noted that because the application initially lacked a filing fee and did not require the potential supporter to submit biometrics—examples of potential control activities—preparers could easily file multiple applications.[75] This was an aspect of the process that some fraud schemes may have exploited. Additionally, antifraud control activities include automated features in data systems to prevent and detect fraudulent activity. However, according to USCIS’s report, its case management system lacked such functionality, for example allowing some applicants to create multiple USCIS accounts with slightly different biographic information or swap in different beneficiaries after the application was confirmed. The system also lacked the ability to efficiently prevent duplicate applications, instead requiring reviewers to manually search for duplicates from the same or different accounts, according to USCIS’s report.

Additionally, limitations in USCIS access to information to review supporter information contributed to the vulnerabilities, the USCIS report found. These included limited access to databases to fully vet supporter criminal history and verify the identities of U.S. citizens. For example, USCIS conducted automated checks of all potential supporters against the National Crime Information Center database upon application submission.[76] This check queried the supporter’s information against active criminal wants and warrants at the time the application was submitted, but did not provide the full criminal arrest history, criminal convictions and dispositions, or other information needed to assess the supporter’s suitability, according to the USCIS report. The report noted that USCIS lacked access to full criminal history record information, although CBP had access to this information.[77] As a result, USCIS confirmed some supporters despite the supporters having a criminal history, as the NTC vetting showed. Further, the two systems USCIS used to verify supporter information were not capable of verifying U.S. passport information—meaning the systems were not strong resources for verifying the identities of U.S. citizens without a history of interacting with USCIS, the USCIS report found.

GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework emphasizes the importance of designing and implementing appropriate internal control activities to manage fraud risks in federal programs, particularly for new programs.[78] Specifically, the Framework states that as a first step, program managers should conduct a fraud risk assessment to assess where fraud may occur in the program and the likelihood and impact of fraud risks. Next, managers should design and implement specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud. Although the Framework applies to all programs, it highlights the importance of taking these steps for new programs or programs that have experienced significant change, as changes may introduce new fraud risks. In addition, effective program managers focus more on activities that prevent rather than detect fraud, to avoid having to address fraud once it is already happening—which can be costly and inefficient.

Another leading practice for program management is to develop an internal control plan that can be immediately implemented or quickly tailored to fit the circumstances of a future emergency or emergent situation.[79] Because the need to act quickly during such situations can increase the risk of fraud, having an internal control plan in place ahead of time can help ensure that program managers consider any fraud risks associated with new programs. Such plans should include potential control activities and may also contain components such as identifying risks specific to the new program and controls to address these risks. In addition, preexisting internal control plans can help program managers quickly adapt when an existing program’s requirements change suddenly or unexpectedly.

As a result of the lack of sufficient internal controls in the CHNV and U4U processes, some individuals perpetrated scams that exploited prospective beneficiaries and stole the identities of U.S. citizens, as described above. In addition, USCIS confirmed some supporters despite them not being eligible, for example those with fictitious biographical information or prior criminal activity.

In its July 2024 report, USCIS made several recommendations to improve internal controls in the CHNV and U4U processes, which—had they been implemented earlier on—may have helped mitigate the fraud risks, USCIS officials said. The report included 41 recommendations to improve various aspects of the processes. Examples were recommendations to collect biometrics and a filing fee from supporter applicants. Other recommendations included improving verification of U.S. citizen identities, such as through passport verification databases; implementing address validation to detect nonexistent addresses; nonconfirming groups of applications that included nonexistent Social Security numbers or those belonging to deceased individuals; and incorporating expanded criminal history checks. In late summer and fall 2024, USCIS began implementing several of the recommended measures, such as adding a biometrics collection and fee requirement and additional supporter vetting.

Although DHS terminated CHNV and suspended the other supporter-based parole processes, USCIS could still benefit from having an internal control plan in place for future situations, including emergent circumstances, that may introduce new or increased fraud risks.[80] Such a plan could help USCIS quickly identify and implement ways to mitigate these risks earlier in the development of a new program, such as a process for reviewing a new immigration benefit form, or a change to an existing program.

A preexisting internal control plan might include basic antifraud controls and other steps to ensure managers are considering fraud risks before implementing a new program or changing an existing program. For example, a USCIS internal control plan might include a mechanism for the appropriate USCIS office to consult key stakeholders early in the development process, such as FDNS or CBP, to identify potential sources of fraud risk prior to implementing the change. Additionally, in developing an internal control plan, USCIS could leverage the recommendations USCIS already made for CHNV and U4U, such as recommendations to collect biometrics and a filing fee from applicants to mitigate fraud risk. The plan could also include a mechanism for identifying and obtaining access to any additional data sources needed to support internal controls, such as criminal history information—whether directly or through information-sharing agreements with other DHS components. Program managers could then use the plan to identify and consider adapting such recommendations and other controls earlier in the implementation of a new program to prevent fraud before it occurs.

DHS Faced Additional Challenges in Implementing the Processes, Such as Resource Limitations and Fragmentation

In addition to the fraud risks and security concerns USCIS and CBP identified, we found that DHS faced several other challenges in implementing the supporter-based parole processes. These included staffing and resourcing challenges, inconsistent review of the reasons for beneficiaries requesting parole, fragmentation of roles and responsibilities across DHS offices and components, and supporters not upholding their commitments to beneficiaries. We discuss steps USCIS and CBP took toward addressing these challenges later in the report.

Staffing and Resourcing Challenges

Applicant interest in the supporter-based parole processes outpaced DHS’s ability to process applications in an efficient, effective manner using the resources it had, according to USCIS and CBP documentation and officials. Given limited staff resources, as well as the 30,000 limit on CHNV approvals each month, USCIS had a backlog of more than 2 million pending supporter applications as of November 2024. The high volume of applications and numbers of arriving beneficiaries placed resource strains on USCIS and CBP, drew staff away from other missions, and would have been unsustainable over the long term, according to USCIS and CBP officials.

USCIS. To review supporter applications for the CHNV and U4U processes, USCIS relied on detailees—staff from across the agency who served temporary assignments in the USCIS office responsible for reviewing supporter applications. USCIS officials told us that because the supporter application process did not confer an immigration benefit, applications did not require review by immigration services officers—USCIS staff specifically trained to make adjudication decisions regarding noncitizens applying for benefits. In particular, immigration officers and asylum officers were not allowed to serve as detailees because they were needed to support other USCIS benefit processing priorities, USCIS officials said.

Instead, USCIS recruited detailee staff in a variety of positions from other offices and trained them to review CHNV and U4U supporter applications. Generally, between 40 and 45 detailees served at one time, overseen by about seven permanent staff, officials told us. They received about a week of formal training, hands-on assistance from more experienced staff, and guidance and tip sheets to help them learn how to review supporter applications, according to USCIS officials. Detailees generally served in the role for 2 to 6 months before returning to their regular duties.

However, the detailee staffing model presented challenges to USCIS ensuring thorough reviews of supporter applications, according to USCIS officials and reports. Detailees had varying degrees of prior experience reviewing immigration benefit forms and many faced a steep learning curve, USCIS officials and detailees said.[81] Although detailees we spoke with generally said the training they received was sufficient, five out of eight indicated that additional training or experience in particular areas would have been helpful, such as on verifying immigration statuses and identifying fraud indicators. USCIS officials who oversaw the work of detailees said they had identified several issues with the quality of their application reviews, such as making incorrect decisions based on missed duplicate applications or lack of thoroughly reviewing immigration status or financial documentation.[82] In addition, USCIS expected detailees to complete between three and five case reviews per hour—and would ask them to leave the detail if they could not, according to USCIS detailees. Three detailees told us that the workload was intense and two said they felt that USCIS was prioritizing review quantity over quality.

In addition, USCIS officials who oversaw the work of detailees said that by the time detailees had fully learned and become comfortable with reviewing applications, their detail was about to end, and they would return to their regular work—taking their training and knowledge with them. This resulted in disruption and inefficiencies when officials needed to start over with a new cohort of detailees. Further, as more cohorts came and went over time, the quality of detailees’ work declined, according to the July 2024 USCIS report. This staffing model would be unsustainable over the long term, the report said.