ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

HHS Action Needed to Improve Lifesaving Program

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to Congressional Committees.

For more information, contact: Mary Denigan-Macauley at deniganmacauleym@gao.gov

What GAO Found

Organ transplantation is the leading treatment for patients with severe organ failure, but as of May 2025, more than 100,000 individuals remained on the national waiting list. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has overseen organ allocation services since 1984, using the same contractor to do so, until recently. In 2024, HHS entered into contracts to assess weaknesses in organ allocation services, as part of a modernization initiative. The assessments target issues, including inequitable organ allocation and insufficient investigation of serious events, such as beginning to recover organs before patient death. However, HHS has not yet developed detailed plans for the next initiative phase, including how it will make reforms to address identified weaknesses. Doing so is crucial to improving HHS’s ability to provide organs to critically ill patients.

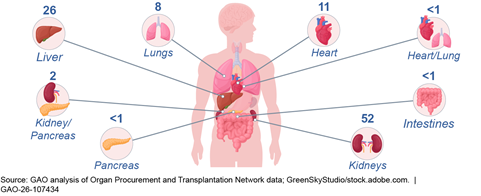

Organ Transplants from Deceased Donors, Percent by Type, 2024

Note: Data show organ transplant types reported by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. In 2024, there were 41,119 organ transplants from deceased donors in the United States.

HHS has not assessed the risks associated with its contractor providing supplementary services outside of its HHS contract, and charging a related monthly fee, to transplant programs. Services include, for example, analytics to help transplant programs manage their waiting lists. In fiscal year 2024, the contractor received about $9.6 million from transplant programs paying the fee. These supplementary services and fee raise several concerns, including whether the services should be provided as part of the contractor’s agreement with HHS and that transplant programs may be paying the fee without realizing it is optional. Assessing the risks associated with this contractor activity, and making changes as appropriate, would better position HHS to ensure it is effectively overseeing its contractor, which has a crucial role in ensuring lifesaving organs are provided to patients effectively and safely.

In 2021, HHS formed a coordination group to improve the organ transplantation system, overseen by two of its agencies. However, the group’s action plan does not include specific, actionable steps with milestone completion dates and measures to gauge success of actions taken. Including these elements, consistent with the group’s charter, would better enable HHS to improve the organ transplantation system through its agencies’ collaborative efforts.

Why GAO Did This Study

Congress and others have raised concerns about systemic issues with organ allocation services, such as the data reliability of the organ matching IT system. In March 2023, HHS announced a modernization initiative to improve organ allocation services.

The Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Act includes a provision for GAO to review the organ transplantation system. This report examines, in part, HHS’s efforts to assess weaknesses in organ allocation services as part of its modernization initiative; the extent to which HHS assesses supplementary services and the fee charged to transplant programs by the contractor; and coordination across HHS.

To conduct this work, GAO reviewed agency and contractor documentation and interviewed officials and representatives from HHS, the contractor, and non-federal groups involved in the organ transplantation system, including providers and patients, among others.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to HHS, including that it develop detailed plans for the next phase of the modernization inititative; assesses risks associated with its contractor’s supplementary services and fee; and that HHS’s coordination group include in its action plan actionable steps with milestones to gauge success of actions taken. HHS agreed with these recommendations.

Abbreviations

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

HIV human immunodeficiency virus

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

OPO organ procurement organization

OPTN Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

OTAG Organ Transplantation Affinity Group

UNOS United Network for Organ Sharing

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2026

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Organ transplantation is the leading form of treatment for patients with severe organ failure. In 2024, there were 41,119 organ transplants from deceased donors across the United States.[1] However, as of May 2025, more than 100,000 individuals remained on the national waiting list to receive an organ.[2] An average of 13 people in the United States die each day waiting for an organ transplant.

Within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) oversees the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The OPTN is a private-public partnership, established in 1984 by the National Organ Transplant Act, to manage the nation’s organ allocation system.[3] The OPTN maintains the national organ transplant waiting list, establishes policies concerning organ allocation, and coordinates the transportation of organs, among other responsibilities. In addition to HRSA, HHS’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also has responsibility for overseeing certain entities involved with organ procurement and transplantation.

A nonprofit entity, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), has until recently been the sole entity under contract with HRSA to administer the OPTN since the program began.[4] The OPTN charges a mandatory monthly patient registration fee to transplant programs based on the number of patients they add to the national waiting list each month—HRSA uses this fee to fund the majority of its contract with UNOS. In addition, UNOS charges a separate, optional monthly fee for supplementary services it provides to transplant programs outside of its OPTN contract, such as analytics to help manage waiting lists and customized data reports. This fee is also based on the number of patients a transplant program adds to the national waiting list each month.

Congress, stakeholder groups, academic experts, and media reports have raised a variety of concerns about systemic OPTN issues, including inequities in access to transplantation, unused organs, data reliability and security issues with the OPTN IT system for organ matching, and lack of transparency and oversight.

In March 2023, HRSA announced its OPTN Modernization Initiative, which includes several actions intended to assess OPTN weaknesses and strengthen accountability and transparency in the OPTN, including the following:

· modernizing the OPTN IT system that matches donors’ organs to individuals on the national organ transplant waiting list, and

· issuing awards to multiple contractors to administer various aspects of the OPTN rather than issuing a single award to one contractor as HRSA had done in the past.

The Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Act includes a provision for us to review the historical financing of the OPTN.[5] This report

1. examines steps HRSA has taken under its OPTN Modernization Initiative to assess weaknesses in the OPTN,

2. examines the extent to which HRSA has completed past annual performance evaluations of UNOS, its long-standing OPTN contractor,

3. examines the extent to which HRSA has assessed the supplementary services provided and the fee charged to transplant programs by UNOS, and

4. examines HRSA and CMS coordinated efforts to improve organ transplantation.

To examine steps HRSA has taken under its OPTN Modernization Initiative to assess weaknesses in the OPTN, we reviewed HRSA and OPTN documentation and information. For example, we examined documentation and information outlining HRSA’s OPTN Modernization Initiative efforts, contracts HRSA awarded under the OPTN Modernization Initiative, and OPTN bylaws and policies. We also reviewed the National Organ Transplant Act, which outlines the OPTN’s responsibilities. To gain information on any weaknesses in the OPTN, we reviewed reports published by national organizations. We conducted a search online to identify reports published within the past 5 years (2019 through 2024). We also reviewed reports referenced in the initial reports our search yielded. In addition, we interviewed HRSA officials and representatives from the OPTN board of directors, UNOS, and six stakeholder associations.[6] We selected these six associations because they represented a variety of stakeholders within the organ transplantation system: organizations that procure organs; transplant surgeons, hospitals, and other providers; histocompatibility laboratory professionals; and transplant patients and their families.[7] During our review, we focused on the organ transplantation system specific to deceased donors, though some of the weaknesses identified could potentially apply to living donors.[8] We also reviewed GAO key practices agencies can use to develop and implement agency reforms.[9]

To examine the extent to which HRSA has completed past annual performance evaluations of UNOS, we searched the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System for all available evaluations of UNOS for the contract starting in April 2019 and ending in March 2024.[10] Federal agencies are generally required to complete annually, and maintain in this system, past performance evaluations for contracts, per the Federal Acquisition Regulation.[11] We also asked HRSA officials for any past performance evaluations of UNOS the agency completed during this time frame. We interviewed HRSA program office and contracting officials to understand their practices for completing the required annual past performance evaluations of UNOS.

To examine the extent to which HRSA has assessed the supplementary services provided and the fee charged to transplant programs by UNOS, we reviewed HRSA, OPTN, and UNOS documentation. We focused our review on the “UNOS fee,” as it is described in UNOS financial statements. This is an optional fee UNOS charges to transplant programs monthly based on the number of patients they register to the national waiting list in a given month.[12] We reviewed HRSA’s contract with UNOS; UNOS financial statements for fiscal years 2022, 2023, and 2024 (the most recent statement available at the time of our review); the OPTN website; and samples of reports UNOS provided transplant programs that paid this fee, as well as documentation related to the OPTN data UNOS used to produce the reports. We reviewed the National Organ Transplant Act to understand the OPTN’s responsibilities outlined in the act. We interviewed or obtained written responses from HRSA and CMS officials, UNOS representatives, and representatives of the OPTN board of directors to learn more about the UNOS fee. In addition, we obtained written responses from two of our selected stakeholder associations, representing transplant professionals and transplant programs, who are familiar with the UNOS fee and the services UNOS provides for the fee. We examined HRSA’s assessment of the services and the fee against federal standards for internal controls, which call for agencies to assess risks facing the agency.[13]

To examine HRSA and CMS coordinated efforts to improve organ transplantation, we reviewed agency documentation to identify agency efforts, including those under their coordination group, the Organ Transplantation Affinity Group (OTAG). For example, we reviewed OTAG’s charter, action plan, and progress update. We also interviewed and obtained written responses from HRSA and CMS officials to understand the steps they have taken to coordinate. In addition, we interviewed representatives from six stakeholder associations identified above, the OPTN board of directors, and UNOS to obtain their perspectives on HRSA’s and CMS’s coordinated efforts to improve organ transplantation. We assessed HRSA and CMS’s coordination efforts against the OTAG charter, which outlines certain required elements of agency coordination. We also assessed the agencies’ efforts against federal standards for internal controls, which call for agencies to document in policies the responsibilities for operational processes and their implementation and effectiveness.[14]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

In 2024, there were 41,119 organ transplants from deceased donors in the United States. According to our analysis of OPTN data, kidneys made up 52 percent of these transplants, followed by livers (26 percent), hearts (11 percent), and lungs (8 percent), among others.[15]

The Organ Transplantation System and Process

The OPTN is composed of several entities involved in the organ transplantation system, including the following:

· Organ procurement organizations (OPO)—nonprofit entities that match organs to recipients using the organ matching IT system maintained by the OPTN. OPOs collect organs from deceased donors and ensure their delivery to transplant programs. In addition, OPOs provide public education about organ donation, work with hospitals to identify potential organ donors, and request consent from the families of deceased donors to procure organs, among other tasks. As of November 4, 2025, there were 55 OPOs, according to the OPTN website. Each OPO serves a donation service area.[16]

· Transplant programs—components within transplant hospitals that provide transplantation of particular types of organs.[17] Transplant programs assess patients for medical need for transplants, register patients on the national waiting list, and perform transplant surgeries, among other responsibilities. A transplant hospital can contain one or more transplant programs.

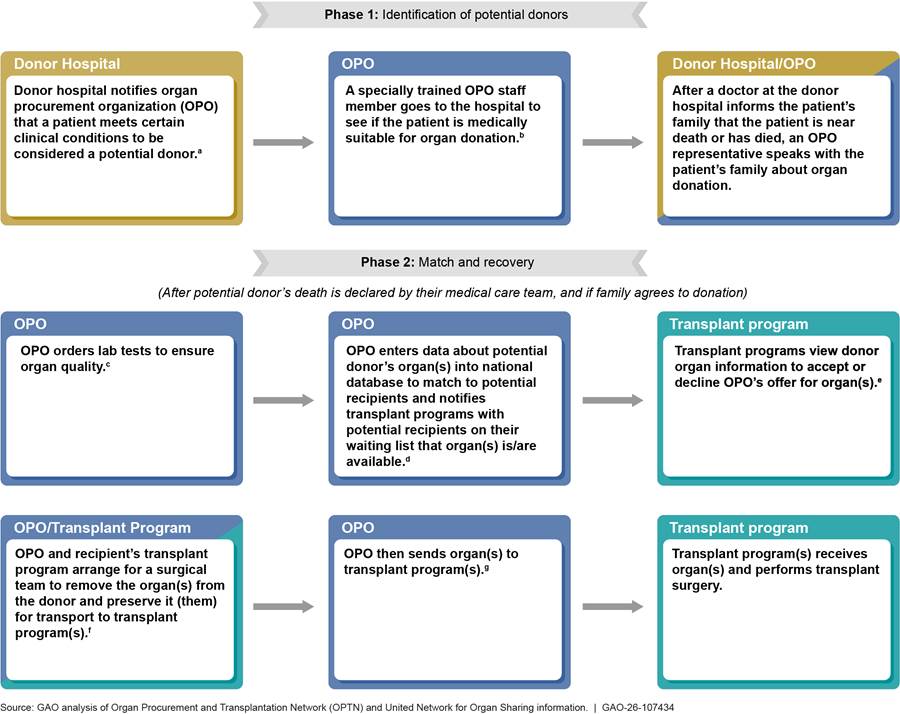

See figure 1 for an illustration of the process for procuring and transplanting organs from deceased donors.

aOPOs are nonprofit entities that match organs to recipients using the organ matching IT system maintained by the OPTN.

bTo determine a patient’s medical suitability, the OPO reviews detailed medical information about the patient’s current medical condition, as well as the patient’s past medical history.

cAn organ would not be viable for transplantation if the patient, for example, had a current or recent cancer diagnosis, or certain bacterial or viral infections.

dTransplant programs are components within transplant hospitals that provide transplantation of a particular type of organ. An OPO enters patient information, such as blood type, and the donor hospital’s zip code into the OPTN’s nationwide data system for organ matching. The system matches organs to potential recipients on the waiting list based on the donor patient and potential recipients’ medical compatibility and national organ-specific allocation criteria. The transplant program with the highest-ranked potential recipient for the organ(s) receives the offer first. The system also notifies transplant programs with lower-ranked potential recipients if the transplant program refuses the first offer.

eThe transplanting surgeon at the receiving transplant program is responsible for ensuring the medical suitability of organs offered for transplant to potential recipients, including whether the deceased donor’s and candidate’s blood types are compatible. According to OPTN Policy 5.6.B, a transplant program generally has 1 hour to access donor information and provisionally accept or refuse the OPO’s offer for an organ. If the transplant program refuses the organ offer or does not respond, the OPO offers the organ to the transplant program of the next highest-ranked match per the waiting list match run. This transplant program has 30 minutes to submit an organ offer acceptance or refusal.

fThe donating patient’s care team is never the same as the surgical team that recovers their organ(s).

gDonated organs require special methods of preservation to keep them viable after they have been removed from deceased patients.

The OPTN

The OPTN is required by the National Organ Transplant Act to carry out several responsibilities essential to the U.S. organ transplantation system.[18] For example, the act requires the OPTN to establish a national list of individuals who need organs and a national system to match organs from donors with individuals on the list. It also requires the OPTN to collect, analyze, and publish data concerning organ donation and transplants, among other responsibilities.

The OPTN final rule, issued in April 1998 and implemented in March 2000, establishes the regulatory framework for the structure and operations of the OPTN:[19]

· The rule outlines OPTN membership composition to include certain entities.[20] According to the OPTN website, as of November 4, 2025, members included all 55 OPOs, 252 hospitals with one or more transplant programs, and 137 histocompatibility laboratories.[21]

· The rule requires the OPTN board of directors to include certain members of the transplant community.[22]

· The rule authorizes the OPTN board of directors to establish any committees necessary to perform the duties of the OPTN. As of December 2025, there were 26 OPTN committees. They focus on topics such as policy development and donations involving specific organs, such as hearts or lungs.

HRSA awarded the first contract to administer the OPTN functions to UNOS in 1986, and until recently, UNOS has been the sole entity under contract with HRSA to administer the OPTN.[23] As the OPTN contractor, UNOS maintains the national waiting list of individuals in need of organ(s) and the IT system that matches organs to individuals on that list, among other responsibilities.

Federal appropriations and transplant program payments are used to cover the cost of the OPTN contract. The federal government generally contributes about 10 percent of the OPTN’s annual operating costs through appropriations, according to OPTN financial statements. According to these statements, the remainder is covered by the OPTN patient registration fee, which is assessed to transplant programs each month based on the number of patients they added to the national waiting list. In fiscal year 2026, the OPTN patient registration fee is $1,036 per patient.[24]

HRSA’s OPTN Modernization Initiative

On March 22, 2023, HRSA announced its Modernization Initiative to strengthen accountability and transparency in the OPTN. As part of the OPTN Modernization Initiative, HRSA intends to build a new organ matching IT system and to administer the OPTN by entering into contracts with multiple contactors rather than one contractor as it had done in the past.

To support the OPTN Modernization Initiative, the appropriation for HRSA for fiscal year 2024 included an increase of $23 million, according to the explanatory statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024.[25]

In addition, as part of the initiative, HRSA sought, and obtained, legislative changes to amend the way that HRSA administers the OPTN. On September 22, 2023, the Securing the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Act provided the Secretary of Health and Human Services with greater flexibility in how awards are made to administer the OPTN.[26] Rather than one contract to support all functions of the OPTN, the amended statute authorizes multiple awards to carry out different functions of the OPTN, among other changes. This change allows the contractor that supports the OPTN board of directors to be different than the contractors that administer the OPTN.[27] Prior to this legislation, the OPTN board of directors and the OPTN contractor’s board (i.e., the UNOS board) were made up of the same individuals.

HRSA and CMS Roles in OPO and Transplant Program Oversight

Both HRSA and CMS monitor OPO and transplant program performance and compliance with certain requirements.[28]

HRSA. HRSA oversees the OPTN which, in turn, is responsible for ensuring OPOs and transplant programs comply with applicable OPTN requirements in the law, the OPTN final rule, OPTN policies, and OPTN bylaws. For example, among their many responsibilities delineated in OPTN policies, OPOs must ensure that donated organs undergo infectious disease testing, and transplant programs must verify the medical suitability between a deceased donor organ and the patient intended to receive it.

If a compliance issue is identified, an OPO or transplant program may address it, in part, by implementing a corrective action plan reviewed by the OPTN. If the OPTN determines it is necessary, it can designate an OPO or transplant program as a “member not in good standing,” place it on probation, or recommend to the Secretary of Health and Human Services appropriate actions, such as termination of participation in the Medicare or Medicaid programs.[29]

CMS. CMS monitors OPOs’ and transplant programs’ performance and compliance with requirements under the conditions for coverage and conditions of participation in Medicare and Medicaid. These conditions are health and safety standards that health care organizations must meet in order to begin and continue participating in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. One of these conditions is that OPOs and transplant hospitals must be OPTN members.[30] CMS may decertify these entities or suspend payment if it finds they are not in compliance with the programs’ requirements.

HRSA Has Contracts to Assess Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Weaknesses, but Lacks Detailed Plans for the Next Phase

In the fall of 2024, HRSA entered into contracts under its OPTN Modernization Initiative to document current practices and assess weaknesses in the OPTN’s ability to execute its responsibilities.[31] In December of 2025, HRSA announced that it had received the results of most of these assessments. However, HRSA has not yet developed detailed plans for the next phase of its OPTN Modernization Initiative, which would help ensure identified weaknesses are addressed.

The contracts are to assess OPTN weaknesses in the following seven areas: 1) organ matching IT system, 2) policy development, 3) organ transportation, 4) organ allocation, 5) OPTN oversight of members and patient safety, 6) communications, and 7) financial management of OPTN operations. HRSA identified these areas by holding listening sessions with transplant patients, their families, and OPO staff, and by obtaining feedback from HRSA officials and UNOS representatives, according to HRSA officials. Our review of reports and interviews with HRSA officials and representatives from six stakeholder associations, UNOS, and the OPTN board of directors provided additional context about the identified weaknesses in the seven OPTN areas:

Organ matching IT system. HRSA awarded two contracts related to improving the OPTN organ matching IT system, as part of its OPTN Modernization Initiative.[32] One contract is to inform HRSA’s strategy for IT modernization and implementation. The other contract was to identify opportunities to improve the current organ matching IT system, including to inform future IT procurement and development work. However, in spring 2025, this contract was reviewed by the U.S. Department of Government Efficiency Service and terminated for convenience, according to HRSA officials.

Some reports we reviewed and representatives from four stakeholder associations we interviewed also noted weaknesses with the organ matching IT system, including a lack of cybersecurity controls and the system being outdated.[33] For example, HRSA’s oversight of UNOS’s compliance with cybersecurity standards was inadequate, according to a December 2024 HHS Office of Inspector General report.[34] The HHS Office of Inspector General concluded in the report that a cybersecurity attacker with a moderate level of sophistication could compromise and cause significant harm to the OPTN organ matching IT system. The HHS Office of Inspector General made four recommendations, which, as of December 2025, HRSA had implemented, according to the Inspector General’s website.[35]

Policy development. HRSA awarded a contract to assess the current OPTN policy development process and to make a prioritized set of recommendations to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the process.[36]

The current OPTN policy development process takes too long, delaying much needed improvements to the organ transplantation system, according to a report we reviewed and representatives from five stakeholder associations we interviewed.[37] For example, we found that the OPTN has made limited progress in implementing continuous distribution—an allocation framework it approved for adoption in 2018 to make organ distribution more equitable, according to the OPTN website.[38] This framework has only been implemented for one type of organ—lungs—and, as of December 2025, HRSA has paused further implementation while the OPTN focused on other priorities, according to HRSA’s website.

Organ transportation. HRSA awarded a contract to assess current organ transplantation logistical challenges and recommend business requirements for improving the logistics of tracking organs, as part of its OPTN Modernization Initiative.[39]

Transportation issues, such as delayed or lost deliveries, resulted in organs that were initially accepted by transplant programs later being declined, placing those organs at risk for non-use, according to an OPTN task force.[40] The task force examined late organ offer declines by transplant programs from April 2024 to May 2024.

Organ allocation. The contract related to organ transportation also tasked the contractor with developing a framework it can use to evaluate the OPTN’s organ allocation policies to ensure organ allocation and distribution are equitable, consistent, and transparent, as part of its OPTN Modernization Initiative.[41]

Some reports we reviewed and representatives from five stakeholder associations we interviewed raised concerns about the OPTN’s organ allocation policies and resulting inequities. For example, some reports and association representatives mentioned how factors used to prioritize individuals on waiting lists can disadvantage certain groups. The OPTN’s organ allocation equity dashboard shows there are disparities in organ distribution based on an individual’s race, sex, geographic location, and other factors.[42] In addition, two of the five stakeholder association representatives mentioned out-of-sequence allocation, which occurs when OPTN members allocate organs to recipients who had not been prioritized by the OPTN organ matching IT system to receive an organ offer.[43] This practice is unfair because patients who were supposed to receive an organ offer are bypassed, according to OPTN documentation and two stakeholder associations we interviewed. In 2024, 19 percent of organ allocations were allocated out of sequence, according to the OPTN website.

OPTN oversight of members and patient safety. HRSA awarded a contract to evaluate and make recommendations to improve OPTN oversight of its members and patient safety complaints as part of HRSA’s OPTN Modernization Initiative.[44] The OPTN establishes performance metrics for OPOs and transplant hospitals and conducts ongoing and periodic reviews and evaluations of each member OPO and transplant program. It also investigates patient safety complaints involving OPTN members. If the OPTN identifies performance issues, it can take steps to address these issues. The contractor’s assessment was to review the OPTN’s processes for monitoring OPOs’ and transplant programs’ performance, investigating patient safety complaints, and taking punitive actions for poor performance, among other things.

Concerns about OPTN oversight of its members’ performance and its investigation of patient safety complaints were raised in some reports we reviewed, by representatives from three stakeholder associations we interviewed, and by Congress.[45] These concerns include insufficient investigation of serious patient safety events and sanctioning of OPTN members once performance problems are identified, and OPOs’ performance measures relying on self-reported data. For example, in July 2025, the House Energy and Commerce Committee held a hearing to examine the OPTN’s response to allegations made by a former employee of an OPO serving Kentucky. The OPTN had initially closed this case without taking any corrective actions. HRSA reopened the case and conducted its own review between December 2024 and February 2025. HRSA’s review found a concerning pattern of risk to certain patients due to staff practices at this OPO.[46]

Prior to September 2025, no OPO had ever been decertified mid-certification cycle regardless of patient safety concerns, according to HHS officials.[47] An HHS press release from September 18, 2025, announced that the department was moving to decertify an OPO after an investigation uncovered years of unsafe practices, poor training, chronic underperformance, understaffing, and paperwork errors. The OPO could appeal this decision, according to HHS officials.

Communications. HRSA awarded a contract to assess HRSA’s and the OPTN’s communications to patients and families, OPTN members, the general public, and others, and to make recommendations to improve OPTN communications.

A wide range of concerns about OPTN communications were raised in some reports we reviewed, by representatives from two stakeholder associations we interviewed, and by Congress. These concerns include a lack of transparency surrounding transplant programs’ organ acceptance decisions, e.g., patients on the transplant waiting list are generally not informed when transplant programs decline organs on their behalf. Concerns raised also included that the OPTN does not share findings from its investigations of patient safety issues, leaving affected parties unsure whether these issues were substantiated and if so, whether they were resolved.

|

HRSA’s new contracts for OPTN operations Separate from the assessment contracts, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has entered into other contracts to support the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network’s (OPTN) operations. For example, · In September 2024, HRSA awarded a contract to support the OPTN board of directors. representatives from three stakeholder · In September 2024, HRSA awarded a contract to support its multiple contractor coordination, as HRSA begins to issue awards to multiple contractors to administer various aspects of the OPTN rather than having one contactor administer the OPTN. Source: GAO summary of information from HRSA and USASpending.gov. | GAO‑26‑107434 |

Financial management of OPTN operations. HRSA awarded a contract to assess and make recommendations related to the financial management of OPTN operations.

The OPTN’s financing is an operational area that needs improvement, according to HRSA officials. These officials said they had concerns related to the transparency of the OPTN patient registration fee, which the OPTN board of directors sets annually and HRSA approves. In recent years, HRSA has denied the OPTN’s requests to increase the OPTN patient registration fee due to these concerns, according to the HRSA officials. Furthermore, in March 2025, HRSA received authority to collect and distribute the OPTN patient registration fee—a new responsibility for HRSA since this fee has historically been collected by UNOS (on behalf of HRSA) to fund the UNOS contract.[48] The financial management contract that HRSA entered into was to include recommendations related to how HRSA can collect the OPTN patient registration fee and distribute it among multiple contractors, according to HRSA officials.

HRSA has taken some actions to improve the OPTN as findings from the assessments have become available, according to HRSA officials and documentation. For example, in July 2025, HRSA directed UNOS to update OPTN data files with more comprehensive data on prospective organ donors to better oversee the care they are provided by OPOs, and to conduct a review of its current OPTN member monitoring processes. HRSA also directed the OPTN to create a workgroup to remediate gaps in policies about allocation practices, including out of sequence allocation, among other actions, according to a September 2025 announcement.

In December 2025, HRSA published reports summarizing the results of most of the assessments.[49] Additionally, the agency announced a next phase of its Modernization Initiative, in which it has contracted with, or will contract with, vendors to administer certain aspects of the OPTN. Specifically, these contracts will support the OPTN in various areas, including data and IT; policy and membership; safety; and communications and collaboration; among others. However, no further details were provided.

Developing detailed plans for the next phase of the Modernization Initiative will be crucial for HRSA to fulfill the goal of the initiative: to strengthen accountability and transparency in the OPTN. Without such plans, identified weaknesses could remain unaddressed and may hinder the OPTN’s ability to effectively provide life-saving organs to patients in need. Furthermore, the plans HRSA develops are likely to be more effective if they take into consideration our leading practices for successful agency reform efforts.[50] These are practices that agencies should consider when making large-scale organizational changes, such as the OPTN Modernization Initiative. These practices indicate that agencies can successfully change if they (1) establish goals and outcomes, (2) follow a process to develop the proposed reforms, (3) develop an implementation plan and team to implement the reforms, and (4) conduct strategic workforce planning that considers workforce needs during and after the reform, among others.

HRSA Began Retroactively Completing Past Performance Evaluations of Its Contractor in March 2025, after Years of No Evaluations

In March 2025, HRSA began to retroactively complete past performance evaluations of UNOS, its long-standing OPTN contractor, after years of not preparing the annual evaluations, as required by the Federal Acquisition Regulation. According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, federal agencies are generally required to prepare annual evaluations of contractor past performance and enter them into the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System—the official source for federal contractor past performance information.[51] This requirement applied to HRSA’s contract with UNOS. Such information is important to record because it may be used to support future contract award decisions.

As of August 2025, HRSA officials had completed one past performance evaluation for UNOS’s 2019 contract and entered it into the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System. However, four evaluations should have been completed.[52] The evaluation HRSA completed assessed UNOS’s performance over the first 18 months of the contract, from April 2019 through September 2020. Following that first performance evaluation, the missing past performance evaluations were for October 2020 through September 2021, October 2021 through September 2022, October 2022 through September 2023, and October 2023 through September 2024.

HRSA contracting officials, who are ultimately responsible for ensuring the past performance evaluations are completed, stated that they discovered the lack of annual performance evaluations in March 2025. These officials were new to their positions as of November 2024. As a result, they did not know and were not able to find documentation indicating why the past performance evaluations had not been completed. However, HRSA program staff told us that they were aware the performance evaluations had not been completed. At that time, they had decided not to complete these evaluations because of the leverage UNOS held as the sole operator of the critical organ matching IT system. They said they were concerned that any negative ratings would risk irreparable disruption to contract renewals and patient services.

The HRSA contracting officials told us they acted to retroactively complete the remaining three of the four required past performance evaluations, once they discovered they had not been completed.[53] The officials stated that they sent the three retroactive past performance evaluations to UNOS for review and comment in April 2025. In August 2025, the contracting officials stated that UNOS had contested the evaluations and HRSA contracting officials were in the process of reviewing UNOS’s position. Once the review process is resolved with UNOS, the contracting officer will finalize the performance evaluations and enter them into the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System.

Additionally, the contracting officials stated that they have taken steps to ensure that past performance evaluations for OPTN contractors are completed in the future. They stated that they met with HRSA program staff to highlight the importance of completing these evaluations and to clarify responsibilities to ensure the evaluations are completed going forward. The contracting officials also established key milestones with associated due dates to ensure timely completion of the next evaluation—due in January 2026—for all involved parties to follow. These officials stated that they believe having the milestone schedule can help ensure that future performance evaluations are completed and entered into the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System in a timely manner.

HRSA’s actions to ensure required past performance evaluations are completed in a timely manner are an important step and could enable HRSA to be better informed when awarding future OPTN contracts. Such informed decisions would ultimately benefit those who depend on the OPTN to ensure organ placement is managed effectively in order to receive life-saving treatment. Ensuring that these past performance evaluations are completed will be especially important given that as part of the OPTN Modernization Initiative, HRSA is in the process of shifting OPTN operations to a multi-contractor model. Under this new model, HRSA contracting officials will be responsible for completing past performance evaluations of multiple contractors.

HRSA Has Not Assessed Risks Associated with Contractor’s Supplementary Services and Fee

HRSA has not assessed risks associated with the supplementary services provided and the fee charged by its OPTN contractor to transplant programs. Specifically, UNOS charges transplant programs a monthly “UNOS fee” for additional services it provides outside of the OPTN contract, such as analytics to help manage waiting lists and customized data reports.[54] UNOS utilizes OPTN data to provide these services.

The UNOS fee, which is optional, is in addition to the mandatory OPTN patient registration fee transplant programs are charged to support HRSA’s contract with UNOS. Like the OPTN patient registration fee, the UNOS fee is charged monthly to transplant programs for each new patient they have registered to the national organ transplant waiting list that month. UNOS received about $9.6 million from the UNOS fee in fiscal year 2024.[55]

However, HRSA has not assessed the risks associated with these supplementary services and the associated fee. These risks are related to the following:

Lack of clarity on whether UNOS’s supplementary services should be provided as part of statutory requirements and the OPTN contract. As part of the UNOS fee, UNOS provides regular reports to transplant programs. These include a quarterly report that analyzes transplantation data so that a transplant program can compare itself to similarly sized programs regionally and nationally to understand and improve performance, and a weekly report that analyzes organ donation and transplantation data to assist transplant programs in understanding organ acceptance behavior.

HRSA officials stated that they do not review the supplementary services UNOS provides transplant programs outside of its OPTN contract. As a result, it is unclear whether these reports fall under existing statutory requirements for the OPTN, such as to “collect, analyze, and publish data concerning organ donation and transplants” and “work actively to increase the supply of donated organs.”[56] These statutory requirements are reflected in the OPTN contract, which requires UNOS to perform functions such as “collecting, analyzing, and publishing organ donation and transplantation data” and “working actively to increase the supply and utilization of donated organs.” If the supplementary services provided by UNOS fall within the scope of existing statutory and contract requirements, then UNOS is charging the supplementary UNOS fee for services that it should already be providing transplant programs.

Limited review of the OPTN data UNOS uses to provide supplementary services. Because HRSA officials do not review the supplementary services UNOS provides transplant programs for its monthly UNOS fee, they do not have insight into the OPTN data that UNOS uses to provide such services, and whether UNOS should credit its contract with HRSA for these data.

The general public, OPTN members, and other entities—including UNOS—may request and use OPTN data and are sometimes charged for certain types of OPTN data requests.[57] For example, a requestor may have to pay for customized or complex data sets based on the level of effort involved in generating the requested data set, and a requestor must pay for any data set involving patient-identifiable information, according to the OPTN website.[58] In its role as the OPTN contractor, UNOS reviews these requests and determines whether the requestor (including itself) should be charged for the data, and if so, how much. If UNOS determines that its use of the data warrants a charge, it must pay the charge as a credit to its contract with HRSA, according to HRSA officials.

HRSA officials told us that they review data requests, including UNOS’s requests, that involve patient-identifiable information to determine if the charge rendered is fair. HRSA officials told us that they rely on UNOS to inform them when such requests are made, but they could not identify a process they used to ensure that UNOS consistently completes such data requests for its own use of these data and properly credits the contract. Additionally, because HRSA does not review all requests for OPTN data that involve a charge, HRSA does not have assurance that UNOS is making appropriate decisions in terms of what to charge others when it comes to customized or complex datasets.

Transplant programs may be paying the supplementary UNOS fee, not realizing it is optional. UNOS sends transplant programs two invoices each month, one for the OPTN patient registration fee on OPTN letterhead and one for the UNOS fee on UNOS letterhead. However, transplant programs may not realize that the UNOS fee is optional—since the OPTN patient registration fee is not— and further may not understand how to opt out of paying the UNOS fee, according to written responses from representatives from a transplant program stakeholder association provided to us in March 2025. Many, if not most, transplant programs are also not aware of what services the UNOS fee covers versus the OPTN patient registration fee, according to association representatives. These representatives were also not aware of a mechanism for transplant programs to opt out of paying the UNOS fee.[59]

HRSA officials told us that they have not taken steps to evaluate the extent to which the supplementary UNOS services and the fee might affect the OPTN program, noting that its contract with UNOS does not expressly prohibit the contractor from providing OPTN members with services beyond those to be provided under the OPTN contract. In August 2025, these HRSA officials commented that the agency’s new authority to collect the OPTN patient registration fee, as enacted by the Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025, may help address some risks associated with the UNOS fee. For example, the distinction between the UNOS fee and OPTN patient registration fee may become clearer to transplant programs, if HRSA collects one fee and UNOS the other. Additionally, in September 2025, HRSA published a patient registration fee user guide, which states that any additional fees, such as the UNOS fee, are optional and at the discretion of the transplant hospital.

Federal internal control standards for risk assessment call for agencies to assess risks facing the agency’s ability to achieve its programs’ objectives—in this case, HRSA’s responsibility to oversee the OPTN contractor—and to develop appropriate risk responses.[60]

By assessing the risks associated with current and future OPTN contractors’ provision of supplementary services and the associated fee, and making changes as appropriate, HRSA will be in a better position to ensure it is effectively managing its contract risks and overseeing its OPTN contractor. This oversight is especially important given the OPTN contractor’s large role in helping ensure that the OPTN is working effectively to provide life-saving organs. It will continue to be important as HRSA moves to a multi-contractor model as part of its OPTN Modernization Initiative.

Coordinated Action Plan Lacks Key Elements but HRSA and CMS Have Taken Actions to Improve Complaint Tracking

HRSA and CMS developed an action plan to help guide their coordinated efforts to improve the organ transplantation system; however, the plan is missing key elements important for measuring and realizing progress. The agencies have taken recent actions to improve coordination in one important area—the sharing of complaint information they each receive and investigate.

HRSA and CMS Have a Coordinated Action Plan, but It Is Missing Key Elements to Measure and Realize Progress

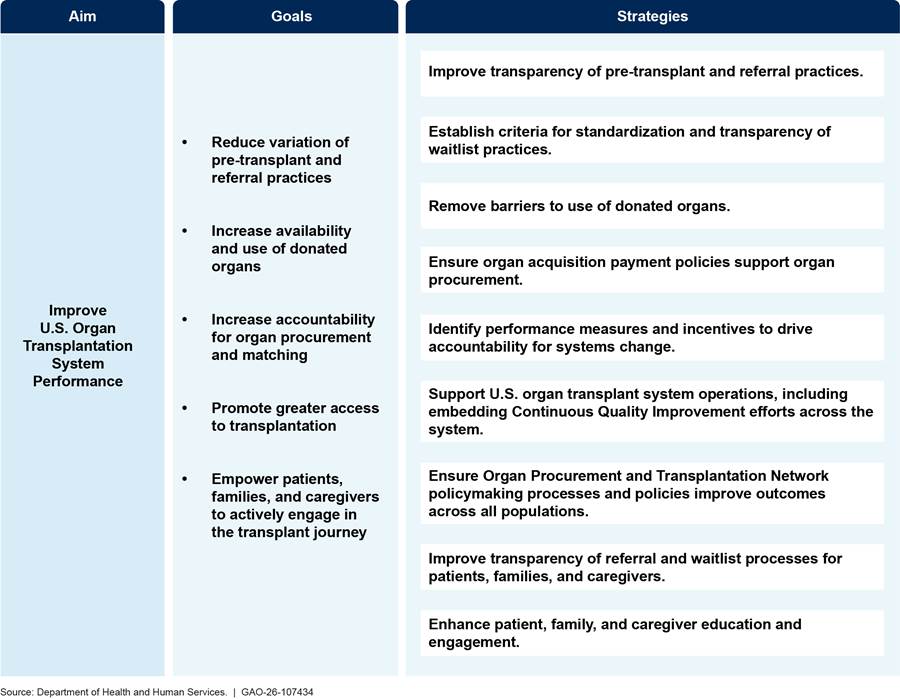

In 2021, the Secretary of Health and Human Services established OTAG, a coordinated effort between HRSA and CMS to improve the organ transplantation system.[61] However, the group’s action plan—OTAG 2023-2028 Action Plan—is missing elements important for measuring and realizing progress toward achieving its stated purpose. Specifically, the action plan does not include specific, actionable steps with milestone completion dates and markers for measuring success of actions taken to achieve goals, elements that should be included in the action plan, according to OTAG’s charter.[62] According to the charter, OTAG is required to develop and annually update, as needed, an action plan that includes goals and objectives, activities related to meeting those goals and objectives, a timeline and/or milestones for those activities, and indicators that will be used to measure success.

OTAG’s action plan was released in September 2023 and subsequently updated in March of 2025. It serves as a road map for HRSA and CMS coordination to improve the performance of the U.S. organ transplantation system by meeting five national goals. Each of the five national goals is supported by strategies that will be implemented by HRSA and CMS, according to agency documentation.[63] (See figure 2 for the OTAG 2023-2028 Action Plan as of December 2025.)

Note: This version of the Organ Transplantation Affinity Group action plan is from March 2025 and was the most current version as of December 2025.

In November 2024, OTAG issued a progress update on the group’s efforts. However, it referenced only one of the five national goals in OTAG’s action plan.[64] The update stated that HRSA had expanded OPTN data collection efforts to improve access to transplantation.[65] It linked this improved data collection effort to supporting OTAG’s national goal to “promote greater access to transplantation.”[66]

The update also mentioned other actions taken by HRSA and CMS individually but did not demonstrate how these efforts have brought them closer to achieving OTAG’s goals and strategies, nor did the update link these actions to coordination between the two agencies. For example, it mentions the establishment of HRSA’s OPTN Modernization Initiative and a new CMS Innovation Center payment model to increase kidney transplants but does not link these efforts to the action plan.[67]

Although the charter directed OTAG to include specific, actionable steps in its action plan, HRSA officials told us that these elements were not included because the agency was working through the details of specific actions to take when OTAG published its action plan in September 2023 and its progress update in November 2024. Additionally, HRSA and CMS officials said that, as of May 2025, they were awaiting discussions with the new administration’s policy officials before making changes to the OTAG action plan.

By including in the OTAG action plan, specific, actionable steps with milestone completion dates and markers for measuring the success of actions taken, HRSA and CMS can help ensure their planned efforts to improve the performance of the organ transplantation system will be successful.

HRSA and CMS Have Taken Recent Actions to Share Complaint Information

In 2025, HRSA and CMS began taking actions to improve the sharing of patient safety and other complaint information they each receive and investigate. Such coordination is important because of the agencies’ intertwined oversight roles of the organ transplantation system. For example, to participate in Medicare or Medicaid, which CMS oversees, OPOs and transplant hospitals must be OPTN members.[68] To be an OPTN member, OPOs and transplant hospitals must abide by OPTN rules and requirements, which HRSA oversees.

HRSA and CMS receive patient safety and other complaints about OPOs and transplant programs from a variety of sources, such as patients, OPO and transplant program staff, and the media, according to HRSA documentation and CMS officials. HRSA and CMS are responsible for investigating complaints based on each agency’s authority, and each agency conducts its own investigations, according to agency officials. Complaints reported to HRSA from 2022 to 2024 included serious patient safety concerns. For example, there was one complaint of the wrong organ being transplanted from an organ donor to a recipient and 11 complaints of suspected or confirmed transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from a donor to a recipient through transplantation, according to data provided to us by HRSA officials.[69]

Initially, HRSA and CMS officials described an informal and ad-hoc approach to sharing complaint information with each other and acknowledged improved coordination was needed, when asked in September of 2024. At that time, they could not provide a complete list of how many and which complaints the agencies shared with one another.

However, in 2025, officials implemented meetings and processes to improve coordination and complaint information sharing. These actions align with federal standards for internal control, which call for agencies to document the responsibilities for operational processes and their implementation and effectiveness.[70] For example, HRSA and CMS implemented the following:

· Biweekly meetings. HRSA and CMS officials instituted biweekly meetings that include discussion of open CMS complaints and open HRSA complaints as standing agenda items.

· Complaint tracker. HRSA and CMS created a tracker to capture certain data elements to track HRSA-CMS coordination on complaints, according to CMS officials. This tracker is used in the biweekly meetings and in ad hoc communications between the agencies, according to agency documentation.

· Standard operation procedure. HRSA and CMS have a draft standard operation procedure that outlines the processes for sharing complaint information between the agencies with concrete steps and assigned roles.

According to the document, it will continue to be refined as HRSA and CMS receive and investigate complaints to inform and implement process improvements. For example, HRSA officials stated that they had developed a new complaint intake process in which HRSA officials are able to see all complaints received by UNOS, not only a subset, as was the case prior. HRSA also established a new patient safety email address that goes directly to HRSA (replacing a former UNOS email address). As of August 2025, HRSA was documenting its new complaint intake process, but officials did not provide time frames for when it would be finalized.

This improved coordination of complaints should result in HRSA and CMS having a fuller picture of potential or actual concerns with an OPO or transplant program, as well as identification of any members with repeated offenses. Ultimately, it should help the agencies ensure that OPOs and transplant programs are meeting both OPTN and CMS requirements, which, in turn, should help ensure that these entities are effectively and safely serving patients.

Conclusions

More than 100,000 people waiting for life-saving organs, as of May 2025, depend on the OPTN to manage the system that procures, allocates, and transplants organs for patients in need. However, systemic OPTN issues may impede its ability to do so effectively. HHS, through its OPTN Modernization Initiative and OTAG effort, has taken some actions to begin to address these issues, including entering into assessment contracts to examine OPTN weaknesses, a positive first step to identifying potential solutions to improving the OPTN. However, further action is needed in three areas.

· HRSA has not developed detailed plans for the next phase of its OPTN Modernization Initiative, including how it will make reforms to the OPTN to address its identified weaknesses. Developing plans that take into consideration GAO’s leading practices for agency reform will better enable HRSA to address OPTN weaknesses that hinder its ability to provide organs to critically ill patients.

· HRSA has not assessed the risks associated with the OPTN contractor providing supplementary services and charging an associated fee to transplant programs. Assessing these risks, and making changes as appropriate, will better position HRSA to ensure it is effectively managing contract risks and overseeing its OPTN contractor. This oversight is especially important given the OPTN contractor’s large role in helping ensure that the OPTN is working effectively to provide life-saving organs. It will continue to be important as HRSA moves to a multi-contractor model as part of its OPTN Modernization Initiative.

· HRSA’s and CMS’s organ transplantation system coordination group, OTAG, lacks specific, actionable steps with milestone completion dates and markers for measuring success of actions taken in its OTAG action plan, despite the requirement to do so per the OTAG charter. The inclusion of specific and actionable steps in the OTAG action plan will better position HRSA and CMS to ensure that OTAG is improving the organ transplantation system through their collaborative efforts.

Without taking these actions, HHS will miss key opportunities to improve the organ transplantation system responsible for providing organs that save the lives of critically ill patients.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services:

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure the Administrator of HRSA develops detailed plans for the next phase of its OPTN Modernization Initiative, including how it will make reforms to the OPTN to address its identified weaknesses. The plans should take into consideration GAO’s key principles for agency reforms. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure the Administrator of HRSA assesses the risks associated with current and future OPTN contractors’ provision of supplementary services and the associated fee and makes changes as appropriate. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure the Administrators of HRSA and CMS take action to ensure that OTAG’s (the agencies’ organ transplantation system coordination group) action plan includes specific, actionable steps with milestone completion dates and markers for measuring success of actions taken, as directed by the OTAG charter. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Secretary for Health and Human Services for review and comment. HHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix I. HHS agreed with our three recommendations, stating that it had taken some initial actions and planned to take additional actions that would address these recommendations. We updated the language in our report to reflect recent agency actions. According to HHS, the OPTN is undergoing significant transformation, and targeted strategies are being developed to enhance transparency, strengthen oversight, and ensure patient safety in organ allocation. Further, HHS stated that it intends to develop dynamic modernization plans guided by GAO’s key principles for agency reform. HHS also stated it recognizes the importance of ensuring there are markers for measuring program progress in the context of available resources and that the coordinating group is positioned to achieve sustainable improvements in the performance and safety of the nation’s organ transplantation system. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Mary Denigan-Macauley

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

Mary Denigan-Macauley at DeniganMacauley@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the individual named above, Deirdre Gleeson Brown (Assistant Director), Mandy Pusey (Analyst-in-Charge), Christina Murphy, and Megha Uberoi made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Jennie Apter, Shannon Brooks, Matthew Crosby, Madeline Quinn Day, Kaitlin Farquharson, Hailey Hubbard, Claire Li, Janet McKelvey, Meghan Perez, Daniel Rathbun, and Roxanna Sun.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]These are national data on single organ transplants reported by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Additionally, in 2024, there were 1,336 multi-organ transplants from deceased donors, according to this data source. Deceased donors include individuals who have donated organs after being declared brain dead, meaning there is an irreversible loss of all brain and brainstem function, as well as individuals who have donated organs after being declared dead based on circulatory death, meaning the heart has stopped beating. In addition to organ transplants from deceased donors, in 2024, there were 7,031 single organ transplants from living donors across the United States. The majority of these were kidney transplants.

[2]The national organ transplant waiting list is a computerized list of candidates who are waiting to be matched with specific deceased donor organs for transplant.

[3]Pub. L. No. 98-507, § 201, 98 Stat. 2339, 2344 (1984) (codified in relevant part, as amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 274). Regulations are codified at 42 C.F.R. pt. 121 (2024).

[4]For example, in September 2024, HRSA awarded a contract to a different entity to support the OPTN board of directors, which previously had been an administrative activity carried out by UNOS.

[5]Pub. L. No. 118-14, § 4, 137 Stat. 69, 70 (2023). As part of this provision, Congress sought information on financing of the OPTN, which we satisfied with an oral briefing.

[6]The Secretary of Health and Human Services held a special election for the OPTN board of directors from May to June 2025, and subsequently a new board was elected. During our review, we interviewed, and obtained written responses from, representatives who were on the OPTN board of directors prior to this election.

[7]These associations are the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations, National Kidney Foundation, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, American Society of Transplantation, American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics, and Association for Multicultural Affairs in Transplantation.

[8]In 2024, there were 7,031 single organ transplants from living donors in the United States, according to data reported by the OPTN.

[9]See GAO, Government Reorganization: Key Questions to Assess Agency Reform Efforts, GAO‑18‑427 (Washington, D.C.: June 13, 2018).

[10]HRSA’s most recent long-term contract with UNOS to administer the OPTN began in April 2019. HRSA exercised option years and utilized contract extensions to continue the contract through March 31, 2026, with the option of extending through Dec. 29, 2026.

[11]The Federal Acquisition Regulation establishes uniform policies and procedures for the acquisition of supplies and services by all executive agencies. Agencies are generally required to prepare performance evaluations of contractor performance for all contracts and orders that exceed the simplified acquisition threshold of $250,000. The Federal Acquisition Regulation states that past performance evaluations must be prepared at least annually and at the time the work under a contract or order is completed. 48 C.F.R. § 42.1502(a). The Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System is an evaluation reporting web system created in 1998 to document and manage federal contractor performance information, including these annual past performance evaluations. See 48 C.F.R. § 42.1502.

[12]UNOS may also charge for services it provides to other entities. Those fees were outside the scope of our review.

[13]According to federal internal control standards for risk assessment, management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives. See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑25‑107721 (Washington, D.C.: May 2025).

[14]According to federal internal control standards for control activities, management should implement control activities through policies and procedures. See GAO‑25‑107721.

[15]These data are according to the organ transplant types the OPTN includes in its reporting of single organ transplants. In addition to those listed, kidney-pancreas transplants made up 2 percent of the total number of organ transplants from deceased donors in 2024, and pancreas, intestine, and heart-lung transplants each made up less than 1 percent, according to OPTN data. OPTN data also includes certain vascularized composite allograft transplants. These are transplants for body parts, such as limbs, that meet certain criteria, including that they contain multiple tissue types. In 2024, of the 41,119 organ transplants, there were four (0.01 percent) vascularized composite allograft transplants from deceased donors. Separate from the 41,119 single organ transplants, the OPTN also reports the number of multi-organ transplants performed. In 2024, there were 1,336 multi-organ transplants from deceased donors.

[16]An OPO’s donation service area is the CMS-designated geographic area an OPO serves. The geographic area must be of sufficient size to ensure maximum effectiveness in the procurement and equitable distribution of organs. 42 C.F.R. § 486.302 (2024).

[17]A transplant hospital is a hospital that furnishes organ transplants and other medical and surgical specialty services required for the care of transplant patients.

[18]Pub. L. No. 98-507, § 201, 98 Stat. at 2344 (codified in relevant part, as amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 274).

[19]63 Fed. Reg. 16,296 (Apr. 2, 1998) (codified at 42 C.F.R. pt. 121 (2024)).

[20]The OPTN is required to admit and retain as members the following entities: all OPOs, transplant hospitals participating in the Medicare or Medicaid programs, and other organizations, institutions, or individuals with an interest in organ donation or transplantation. 42 C.F.R. § 121.3(b) (2024).

[21]OPTN membership also included 21 health and medical professional/scientific organizations; 15 individual members of the general public, such as ethicists and donor family members; and 54 business members, such as medical staffing companies. Histocompatibility laboratories are laboratories that perform testing to determine the compatibility between a donor organ and a potential recipient for transplantation purposes.

[22]The National Organ Transplant Act requires the OPTN to have a board of directors that includes representatives of OPOs, transplant centers, voluntary health associations, and the general public. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(1)(B). The OPTN final rule further specifies that the board must also include transplant coordinators, histocompatibility experts, and non-physician transplant professionals. In addition, approximately 50 percent of the board must be transplant surgeons or physicians and at least 25 percent of the board must be transplant candidates or recipients, organ donors, and their family members, according to the final rule. 42 C.F.R. § 121.3(a) (2024).

[23]HRSA’s most recent long-term contract with UNOS to administer the OPTN began in April 2019. HRSA exercised option years and utilized contract extensions to continue HRSA’s contract with UNOS through March 31, 2026, with the option of extending through Dec. 29, 2026.

[24]The amount of the fee is to be calculated to cover, together with contract funds awarded by HRSA, the reasonable costs of operating the OPTN and is determined by the OPTN with approval from the Secretary of Health and Human Services. 42 C.F.R. § 121.5(c) (2024).

[25]Staff of H.R. Comm. on Appropriations, 118 Cong., Rep. on H.R. 2882/Public Law 118-47 761 (Comm. Print 2024). According to the fiscal year 2026 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees for the Administration for a Healthy America, which included programs administered by HRSA, the enacted amount for organ transplantation for fiscal year 2024 was $54 million, inclusive of the $23 million increase. HRSA was covered by a continuing resolution for the entirety of fiscal year 2025. See Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025, Pub. L. No. 119-4, § 1101(a)(8), 139 Stat. 9, 11.

[26]Pub. L. No. 118-14, 137 Stat. at 69 (codified in relevant part at 42 U.S.C. § 274(a) and (b)).

[27]In July 2024, HRSA announced it had separated the OPTN board of directors from the UNOS board of directors so that the OPTN board may better serve the interests of patients and their families. In May and June 2025, HRSA held a special election for a new OPTN board of directors.

[28]In addition to OPOs and transplant programs, the OPTN and CMS also oversee histocompatibility laboratories.

[29]See 42 C.F.R. § 121.10(c) (2024). The OPTN can place an OPO or transplant program on probation or designate it as a “member not in good standing,” if it has failed to comply with OPTN requirements. A member not in good standing loses its OPTN voting privileges, whereas a member on probation does not. In addition, a member not in good standing cannot participate on the OPTN board of directors or any of the OPTN advisory committees. The OPTN notifies the public when an OPTN member is not in good standing or is placed on probation; however, OPTN members can continue to operate under either of these designations.

[30]Section 1138 of the Social Security Act requires transplant hospitals and OPOs to be members of, and abide by the rules and requirements of, the OPTN as a condition of participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. 42 U.S.C. §1320b-8. See also 42 C.F.R. §§ 482.45(b)(1) (transplant hospitals) and 486.320 (OPOs) (2024).

[31]Some of the contracts to support the OPTN Modernization Initiative were new awards and others were task orders issued under existing awards. We refer to both as “contracts” throughout the report.

[32]The OPTN is required to establish a national list of individuals who need organs and a national system to match organs from donors with individuals on the list. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(2)(A). The current OPTN organ matching IT system, called UNet, is a centralized computer network that links OPOs, transplant hospitals, and histocompatibility labs. Transplant professionals access this web-based transplant platform to list patients for transplant, match patients with available donor organs, and submit required OPTN data.

[33]Cybersecurity controls protect the organ matching IT system from cyberattacks (e.g., phishing). This is important because the IT system contains data on all organ donors, transplant candidates, and recipients, as well as outcomes related to organ transplants.

[34]HHS Office of Inspector General, The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network IT System’s Cybersecurity Controls Were Partially Effective and Improvements Are Needed, A-18-22-03400 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 2, 2024).

[35]The HHS Office of Inspector General recommended that HRSA 1) require UNOS to remediate the 22 vulnerabilities identified during its audit, 2) verify that the vulnerabilities were remediated, 3) require UNOS to improve network monitoring of the OPTN IT system, and 4) implement procedures to help ensure that UNOS is adhering to federally required cybersecurity controls policies and standards on a continuing basis.

[36]The OPTN is required to adopt and use standards of quality for the acquisition and transportation of donated organs. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(2)(E). See also 42 C.F.R. § 121.4 (2024) (requiring the OPTN to adopt policies for the equitable allocation of organs). The OPTN develops policies using a 10-step process, which involves evidence gathering, seeking public comments, and obtaining OPTN board of director approval.

[37]Representatives from the OPTN board of directors we interviewed acknowledged that OPTN policymaking can be slow. They explained that OPTN members must reach consensus before making policy changes, which can cause delays. Additional factors that can cause delays include, for example, the need to reprioritize projects at times due to urgency and resource availability and the requirement for a public comment period, according to the representatives. Two stakeholder association representatives also told us that the infrequency of OPTN board meetings causes delays, among other reasons.

[38]A continuous allocation framework allows multiple factors that contribute to a successful transplant to be considered simultaneously as part of the organ offer process. For example, the potential transplant candidate’s proximity to the donor’s hospital, their medical urgency, and their expected outcome are all factors considered when organs are matched and offered to potential recipients. Under the system without continuous distribution, these factors are considered sequentially. At any point in the process, one of these factors can deprioritize a potential recipient from receiving an organ offer. For example, a potential recipient’s distance from the donor hospital could deprioritize them over another individual who has a less urgent need for the organ.

[39]OPOs are responsible for recovering organs from deceased donors and coordinating their transport to transplant programs. 42 U.S.C. § 273(b)(3)(F). They work directly with donor families and hospitals, and they also collaborate with other entities in the transplant system, such as courier services. The OPTN is required to coordinate, as appropriate, the transportation of organs from OPOs to transplant centers. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(2)(G).

[40]OPTN, “OPTN Expeditious Task Force, Regional Meeting Update,” accessed August 25, 2025.

[41]The OPTN is required to establish medical criteria for allocating organs and assist OPOs in the nationwide distribution of organs equitably among transplant patients. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(2)(B) and (b)(2)(D). See also 42 C.F.R. § 121.8 (2024).

[42]The OPTN monitors trends in the access of patients on the waiting list to deceased donor organs using an Equity in Access dashboard implemented by the OPTN in 2020.

[43]The organ matching IT system matches and ranks potential organ recipients into the order in which they are to receive an organ offer based on certain factors. A transplant program may transplant an organ into any medically suitable candidate if the organ would otherwise be discarded. See 42 C.F.R. § 121.7(f) (2024).

[44]The OPTN is required to establish membership criteria. 42 U.S.C. § 274(b)(2)(B). By accepting membership in the OPTN, each member agrees to comply with applicable OPTN requirements in the law, the OPTN final rule, OPTN policies, and OPTN bylaws. The OPTN is responsible for monitoring its members to ensure they continue to meet the criteria for membership.

[45]See, for example, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations hearing, “Ensuring Patient Safety: Oversight of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplant System,” on July 22, 2025.

[46]HRSA reviewed 351 cases in which organ donation was authorized but not completed at the OPO serving Kentucky. HRSA found that at least 28 patients may not have been deceased at the time organ procurement was initiated, among other serious concerns. HRSA directed the OPTN to develop a 12-month monitoring plan to ensure that the OPO addresses patient safety concerns.

[47]CMS certifies OPOs by assessing their compliance with federal conditions for coverage through regular surveys and outcome-based performance measures. CMS recertifies OPOs every 4 years. See 42 C.F.R. pt. 468 subpt. G (2024).

[48]Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025, Pub. L. No. 119-4, § 1904, 139 Stat. at 32. HRSA’s authority to collect the patient registration fee lasts for the period covered by the act, or until September 30, 2025. This authority was extended through January 30, 2026, by the Continuing Appropriations, Agriculture, Legislative Branch, Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, and Extensions Act, 2026, Pub. L. No. 119-37, div. A, § 101, 139 Stat. 495, 496 (2025).

[49]The findings from one contract, examining strategies for IT modernization and implementation, are due in March 2026.

[51]Under the Federal Acquisition Regulation, federal agencies are generally required to prepare evaluations of contractor performance for all contracts and orders that exceed the simplified acquisition threshold of $250,000. 48 C.F.R. § 42.1502.