NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES

Ginnie Mae and FHFA Could Enhance Financial Monitoring

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional addressees.

For more information, contact: Jill Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Over the past decade, housing finance increasingly relied on nonbank mortgage companies (nondepository institutions specializing in mortgage lending). Nonbanks now originate and service most loans in the over $9 trillion in securities guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, a government-owned corporation, and by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are under Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) conservatorship. From 2014 to 2024, the share of such loans serviced by nonbanks grew from 27 percent to 66 percent. But nonbanks have certain risks, such as reliance on short-term credit that may become unavailable during economic downturns. The failure of a large nonbank—or multiple smaller ones—could disrupt mortgage markets and increase federal fiscal exposure.

Ginnie Mae and FHFA have processes to assess the financial condition of nonbanks, but opportunities exist to enhance their processes.

· Financial data. Both agencies analyze nonbanks’ self-reported financial data to support their nonbank monitoring. However, GAO found that FHFA does not have written procedures to assess the reliability of these data, reducing assurance that its analytical results are dependable.

· Watch lists. Both agencies produce watch lists of nonbanks that pose relatively higher risks, based partly on financial data. But, based on GAO’s analysis, both agencies’ processes do not fully assess key risks of certain short-term credit lines. As a result, the agencies may not be fully considering information material to watch list determinations.

· Scenario analyses. Both agencies analyze the effect of changing economic conditions on nonbank financial health. To help manage its counterparty risk from nonbanks, Ginnie Mae performs a detailed analysis and uses a comprehensive economic stress scenario. But Ginnie Mae’s focus on a single adverse scenario does not reflect a fuller range of possible outcomes—potentially diminishing its ability to prepare for how different scenarios could affect its portfolio and financial exposure.

Why GAO Did This Study

Nonbank mortgage companies generally do not have a federal regulator overseeing their safety and soundness. But Ginnie Mae and FHFA, which support the stability of markets for mortgage-backed securities, play a role in monitoring these entities.

Since 2013, GAO has designated the federal role in housing finance as a high-risk area. This report examines the (1) role of nonbanks in the mortgage market since 2014, including their benefits and risks; and (2) extent to which Ginnie Mae and FHFA designed processes to assess the financial condition of nonbank mortgage companies.

GAO reviewed Ginnie Mae and FHFA policies, procedures, and analysis of nonbanks. GAO analyzed industry and government data on mortgage loans originated or serviced by nonbanks in 2014–2024. GAO also interviewed FHFA, Ginnie Mae, and Financial Stability Oversight Council officials, as well as researchers and subject matter experts from industry and consumer groups.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations: for FHFA to develop procedures to assess the reliability of nonbank data it uses for monitoring, FHFA and Ginnie Mae to improve their processes for assessing risks of nonbank use of short-term credit lines, and Ginnie Mae to consider additional nonbank stress scenarios. FHFA and Ginnie Mae agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

Abbreviations

enterprises government-sponsored enterprises

FHFA Federal Housing Finance Agency

FSOC Financial Stability Oversight Council

HMDA Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

MBFRF Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form

MBS mortgage-backed security

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 10, 2026

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Nonbank mortgage companies—nondepository institutions specializing in mortgage lending—have critical functions in the housing finance system.[1] After the 2007–2009 financial crisis, nonbanks increasingly took the place of banks in originating and servicing mortgage loans, including those packaged into federally backed securities. These securities are guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, a government-owned corporation, and by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored enterprises (enterprises) under Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) conservatorships.[2]

Financial monitoring of nonbanks has become increasingly important because of nonbanks’ expanding market role and financial vulnerabilities. As we previously reported, nonbanks have fewer financial resources than banks on which to draw and depend on short-term funding that may become unreliable during economic downturns.[3] The failure of a large nonbank or multiple nonbanks could significantly disrupt the availability and servicing of mortgage loans and increase federal fiscal exposures. A May 2024 report by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) said that in a stress scenario, nonbanks also could pose risks to the stability of the broader financial system.[4]

Nonbanks generally do not have a federal regulator comprehensively overseeing their safety and soundness. However, to help manage the risks of guarantee programs for agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), Ginnie Mae and FHFA monitor the financial condition of nonbanks.[5] In January 2025, we reported on coordination between Ginnie Mae and FHFA in monitoring nonbanks.[6]

Since 2013, we have designated resolving the federal role in housing finance as a high-risk area because of the government’s large fiscal exposure and because objectives for the future federal role remain unestablished.[7] We prepared this report at the initiative of the Comptroller General.

This report examines (1) how the role of nonbanks in the housing finance system evolved from 2014 to 2024 and their benefits and risks for the system, and (2) the extent to which Ginnie Mae and FHFA developed selected processes for assessing the financial condition of nonbanks approved to participate in agency MBS programs.

For the first objective, we analyzed Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) and Inside Mortgage Finance data to identify trends in nonbank mortgage origination and servicing, respectively, from 2014 to 2024.[8] We also reviewed prior GAO reports, agency reports, and academic literature on these topics.

For the second objective, we reviewed Ginnie Mae and FHFA documents related to processes for assessing the reliability of nonbanks’ financial data, developing watch lists of nonbanks that pose relatively higher risks, and analyzing the financial condition of nonbanks under stress scenarios. We selected these processes because they are relevant to both agencies and because of their importance for identifying nonbanks that pose a higher default risk or may struggle under adverse economic conditions.[9] Documents we reviewed included procedures, reports, and model development documentation. We compared the agencies’ processes to agency policies, nonbank risks identified by FSOC, and practices and principles from federal banking regulators and major credit rating agencies, where applicable.

For both objectives, we interviewed officials from FHFA, Ginnie Mae, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and FSOC (chaired by the Department of the Treasury). We also interviewed representatives from the Mortgage Bankers Association (a leading industry group), the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (which coordinates states’ supervision of nonbank mortgage companies), a consumer advocacy group, and a major credit rating agency, as well as former senior FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials. We selected these stakeholders because they had published work on nonbank mortgage companies since 2020. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Mortgage Lending and Servicing

In the primary mortgage market, lenders originate mortgage loans to borrowers to purchase housing. After origination, loans must be serviced until paid off or foreclosed. Lenders engage mortgage servicers to perform various functions, including collecting payments from the borrower and remitting them to the lender, sending borrowers monthly account statements and tax documents, and responding to customer service inquiries.

Lenders hold mortgage loans in their portfolios or sell them to institutions in the secondary market to transfer risk or to increase liquidity. Secondary market institutions, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, can hold the loans in their portfolios or pool them into MBS that are sold to investors. The right to service a mortgage loan becomes a distinct asset—a mortgage servicing right—when contractually separated from the loan as the loan is sold or securitized.

Nonbank Oversight and Monitoring

State regulators are the primary regulators of nonbanks.[10] States have authority to examine, investigate, and take enforcement action against nonbanks that are chartered or licensed to operate in their respective jurisdictions.[11] States coordinate nonbank supervision through the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, whose members are state banking and financial regulators from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. In 2021, the Conference approved model prudential standards for nonbank mortgage servicers.[12] As of October 2025, 15 states had wholly or partially adopted these or comparable standards.[13]

Nonbanks generally do not have a federal regulator comprehensively overseeing their safety and soundness.[14] However, a number of federal agencies and the enterprises play a role in monitoring nonbanks.

· Ginnie Mae is a government-owned corporation in the Department of Housing and Urban Development that provides an explicit federal guarantee of the timely payment of principal and interest on MBS backed by mortgages insured or guaranteed by federal agencies. Ginnie Mae operates a program through which approved financial institutions (issuers) pool and securitize eligible loans and issue Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS.

Ginnie Mae is not an independent regulatory agency but sets capital, liquidity, and other eligibility requirements for issuers in its MBS program and has guaranty agreements with these issuers. For example, in 2022, Ginnie Mae updated its minimum financial eligibility requirements for issuers, including a risk-based capital ratio for nonbanks. If an issuer defaults on its obligations under Ginnie Mae’s MBS program—for instance, by failing to make timely payment of principal and interest to MBS investors—Ginnie Mae can take several actions.[15] These include extinguishing the issuer’s legal or other right to the pooled loans in the Ginnie Mae MBS for which the issuer has responsibility. Ginnie Mae also can seize the issuer’s Ginnie Mae MBS portfolio and service it itself or permit its transfer to another issuer. According to Ginnie Mae officials, the agency has authority to govern the manner in which participants operate in its programs but lacks express authority to regulate those institutions, including nonbanks. Ginnie Mae’s Office of Enterprise Risk has responsibilities for monitoring and managing the agency’s risks, including development of risk-management procedures.

· Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchase mortgage loans that meet certain criteria and hold the loans in their portfolios or pool them as collateral for MBS sold to investors. In exchange for a fee, the enterprises guarantee the timely payment of principal and interest on MBS they issue.

The enterprises each set capital, liquidity, and other eligibility requirements for the financial institutions that participate in their MBS programs (known as seller/servicers) and have processes to approve and monitor compliance with these and other requirements.[16] If a seller/servicer fails to comply with eligibility or other program requirements, the enterprises can take several mitigating actions up to and including suspending or terminating the seller/servicer’s participation in enterprise programs and requiring the transfer of the related enterprise MBS portfolios to another approved seller/servicer.

· FHFA is the financial regulator for the enterprises and placed the enterprises into conservatorships in September 2008 because of substantial deterioration in their financial condition. As both conservator and regulator of the enterprises, FHFA has authorities that can help manage risks associated with the enterprises’ nonbank counterparties. For example, in recent years, FHFA issued Advisory Bulletins to the enterprises on valuation of mortgage servicing rights, managing counterparty risk, and oversight of third-party service providers. Since 2021, FHFA has used its conservatorship authority to conduct on-site reviews of several nonbanks to inform its oversight of the enterprises.[17] FHFA’s Counterparty Risk and Policy Branch in the Division of Enterprise Regulation has responsibilities for monitoring the financial condition of nonbank seller/servicers.

Other federal entities monitor or oversee various aspects of nonbanks. For example, in March 2020, FSOC established a nonbank mortgage servicing task force in response to concerns about the financial condition of nonbanks during the COVID-19 pandemic. The task force, whose participants included Ginnie Mae and FHFA, facilitated interagency coordination and monitored the nonbank market and risks nonbanks pose to U.S. financial stability. Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has supervisory and enforcement authority over nonbanks with respect to federal consumer financial protection laws.[18] Finally, federal agencies that insure or guarantee home loans, such as the Federal Housing Administration, conduct some oversight of nonbanks that participate in their programs, such as reviewing and approving lenders and setting financial eligibility requirements.[19]

Housing Finance System Increasingly Has Relied on Nonbanks

Since 2014, Nonbanks’ Share of Loans in Agency MBS Has Increased Significantly

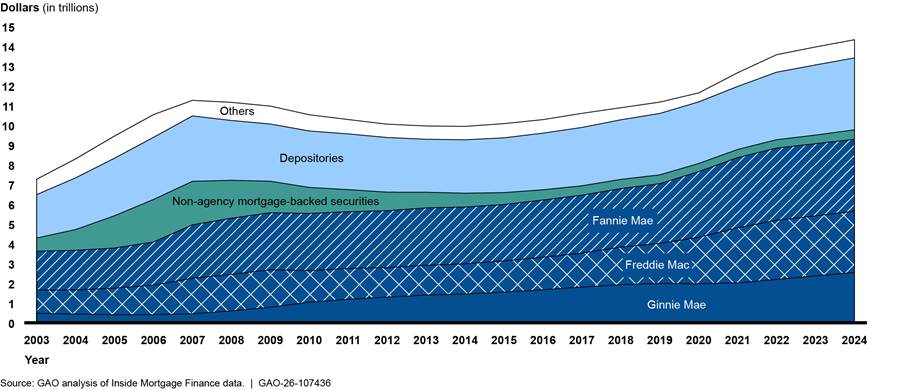

Since the 2007–2009 financial crisis, the federal government has supported an increasing share of the single-family mortgage market through enterprise and Ginnie Mae MBS—collectively referred to as agency MBS (see fig. 1). Immediately before the crisis, loans in nonagency MBS accounted for about 20 percent of mortgage servicing outstanding (by dollar value) and loans in agency MBS accounted for about 40 percent.[20] In 2024, loans in agency MBS accounted for about 65 percent ($9.3 trillion) of mortgage servicing outstanding and nonagency MBS for about 3 percent.

After the 2007–2009 financial crisis, banks retreated from the mortgage market, partly because of changes in capital requirements that made it more expensive for banks to hold mortgages and financial and reputational costs from mortgage-related litigation. Experts we interviewed also noted that banks historically have not dominated mortgage lending and that banks’ participation was historically high immediately after the financial crisis.[21] The experts noted that they did not anticipate banks returning to a dominant role in the mortgage market. In their absence, nonbank mortgage companies took on a greater role.

Nonbanks have originated and serviced a growing share of mortgage loans in the agency MBS market.

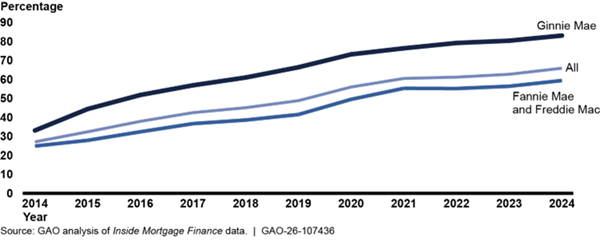

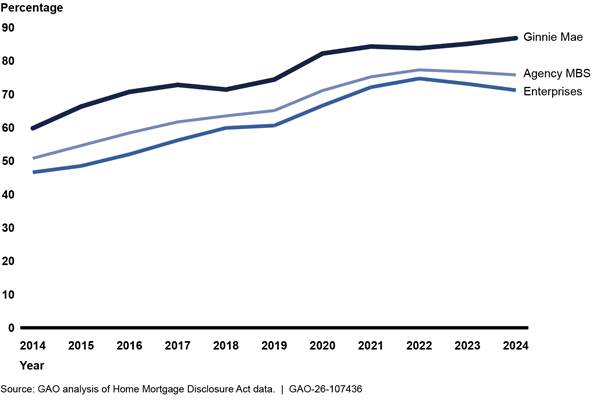

· Origination. Overall, the share of loans (by dollar value) in agency MBS originated by nonbanks rose from 51 percent in 2014 to 76 percent in 2024, according to HMDA data (see fig. 2). In 2024, nonbanks originated 71 percent of loans in enterprise MBS and 87 percent of loans in Ginnie Mae MBS.

Figure 2: Percentage of Loans in Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) Originated by Nonbanks, by Dollar Value, 2014–2024

Notes: Agency MBS comprise loans in Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS.

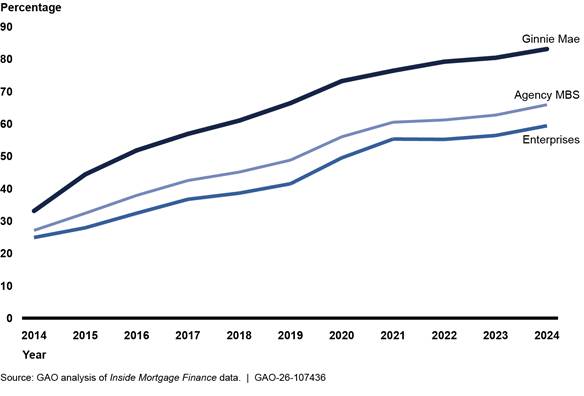

· Servicing. Overall, the share of loans in agency MBS serviced by nonbanks rose from 27 percent in 2014 to 66 percent in 2024, according to Inside Mortgage Finance data (see fig. 3). In 2024, nonbanks serviced 59 percent of loans in enterprise MBS and 83 percent of loans in Ginnie Mae MBS.

Figure 3: Percentage of Loans in Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) Serviced by Nonbanks, by Dollar Value, 2014–2024

Note: Agency MBS consist of both Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS.

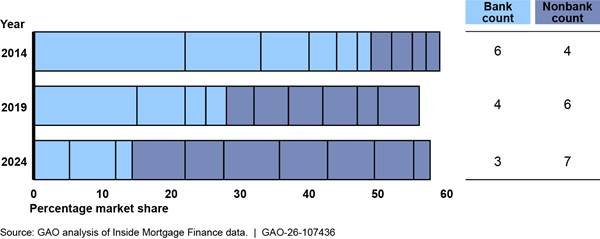

Since 2014, the enterprises’ and Ginnie Mae’s largest counterparties have shifted from banks to nonbanks. Over this period, the top 10 servicers of loans in agency MBS have serviced about 60 percent of the total unpaid principal balance of these loans. However, the number of nonbanks in the top 10 grew from four in 2014 to seven in 2024 (see fig. 4). Banks are supervised by federal banking regulators that provide an additional layer of oversight and tools to address financial risks. In contrast, nonbanks generally do not have a federal regulator comprehensively overseeing their safety and soundness.

Figure 4: Market Share and Institution Type of Top 10 Servicers of Loans in Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) in 2014, 2019, and 2024

Note: Each bar section represents a top 10 servicer of loans in agency MBS and its market share.

Nonbanks Can Quickly Adapt to Market Changes but Face Liquidity Risks

Nonbanks provide some benefits to mortgage markets and consumers, according to our prior work, FSOC, and experts we interviewed.[22]

· Technology. Nonbanks’ adoption of new technology has made it quicker and easier for some borrowers to get a mortgage loan, according to the FSOC report. For example, a 2018 study noted the rise of mortgage lenders employing technologies that allowed borrowers to complete an application entirely online and that all such companies were nonbanks.[23]

· Increased market liquidity. Nonbank servicers have contributed to liquidity in the mortgage market since the financial crisis by bringing in new market participants, such as new investors and funding sources (such as private equity), according to our prior work and the FSOC report.[24] However, these new sources may have less long-term commitment to the mortgage market and could exit the market during an economic downturn.

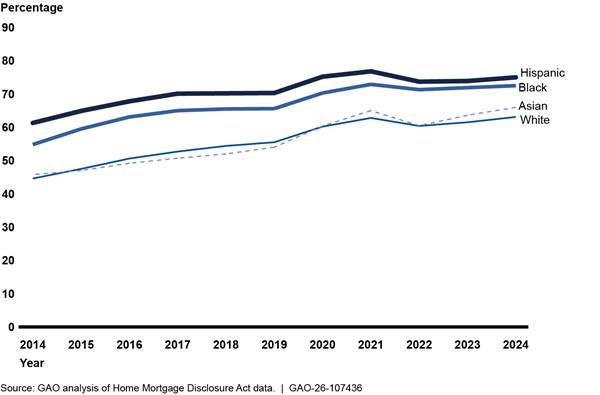

· Underserved borrowers. Our analysis of HMDA data shows that nonbanks have played a particularly large role among historically underserved and lower-income homebuyers. For example, in 2024, nonbanks originated over 70 percent of the mortgage loans to Black and Hispanic borrowers, compared with about 65 percent of the mortgage loans to White and Asian borrowers (see fig. 5).

Note: Hispanic borrowers can be of any race.

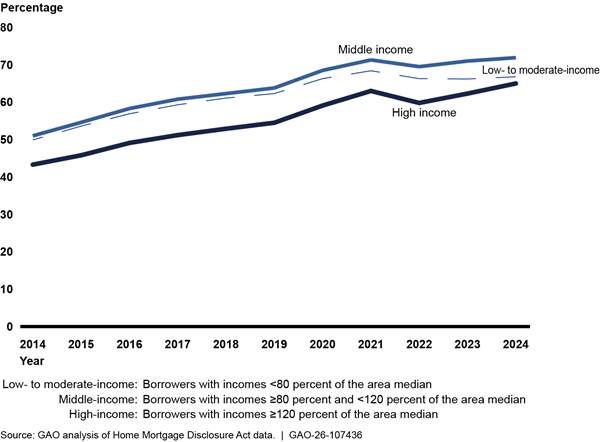

In addition, nonbanks have served higher proportions of low- to moderate-income borrowers and middle-income borrowers (see fig. 6).[25] In 2024, nonbanks originated 67 percent and 72 percent of mortgage loans to these groups, respectively, compared to 65 percent of mortgage loans to high-income borrowers.

However, nonbanks have vulnerabilities relating to liquidity, asset concentration, and leverage.

· Liquidity. Nonbanks may face liquidity challenges under stress conditions. They have fewer resources than banks on which to draw and do not have access to the liquidity facilities that the Federal Reserve System or Federal Home Loan Bank System make available to member banks.[26] Additionally, many nonbanks rely on short-term warehouse lines of credit for financing their operations.[27] During difficult economic conditions, these creditors may tighten loan terms or face strong incentives to cancel loans and seize collateral as permitted.

Furthermore, nonbank servicers may need to advance principal and interest payments to MBS investors even when borrowers are not making those payments. We previously reported that enterprise servicers must advance payments for a limited time, while Ginnie Mae issuers must advance payments until final credit resolution (for example, until the loan performs again or is foreclosed).[28] Servicers also may have to satisfy property tax and insurance obligations for the delinquent borrower. Thus, in times of economic stress, nonbank servicers could face liquidity strains if borrower delinquencies rose.

· Asset concentration. Nonbank mortgage companies typically have their assets concentrated in mortgage-related assets, making their financial stability particularly vulnerable to changes in the mortgage market. Mortgage servicing rights are a primary asset of many nonbanks, but their value can fluctuate and be sensitive to changes in mortgage delinquency rates and interest rates. In addition, the FSOC report found that when demand for mortgages declined in 2022 and 2023, about 30 percent of nonbanks were profitable. In contrast, banks are typically involved in multiple lines of business and thus are less likely to be affected by one particular market.

· Leverage. Finally, the FSOC report also found that some nonbanks are highly leveraged—have high levels of debt relative to tangible assets—which could negatively affect their financial stability. The report cited Ginnie Mae data showing that 35 percent of the over 550 nonbanks that reported financial data to Ginnie Mae and the enterprises had high levels of debt, according to measures used by Moody’s Ratings (a credit rating agency). In addition, the report cited data showing that of the 11 large nonbanks for which Moody’s provides a corporate credit rating, Moody’s consistently rated the debt of the companies as speculative grade, indicating higher credit risk.

FSOC found that these risks have grown as nonbanks’ size and market share increased in the past 10 years. The report also found nonbanks are increasingly interconnected by working with the same warehouse lenders or subservicers.[29] As a result, financial stress at one nonbank could affect others. For example, financial concerns about one nonbank could lead a warehouse lender to tighten credit for similar companies.

The failure of a large nonbank or multiple nonbanks could harm borrowers through disorderly servicing transfers and disruption of origination channels. For example, we reported in March 2016 that some borrowers experienced harm when mortgage servicing rights were transferred to certain nonbanks, including losing their homes to foreclosure.[30] These transfer errors could particularly affect borrowers in loss-mitigation proceedings (such as temporary pauses or reductions in loan payments). The FSOC report noted that no servicing transfers have ever occurred at the scale of the current largest nonbank portfolios.

Nonbank failures also could expose Ginnie Mae and the enterprises to potential financial losses or operational risks. For example, if a large nonbank servicer whose portfolio cannot be easily absorbed by other servicers were to fail, Ginnie Mae and the enterprises could have to service the portfolio themselves or through a contracted subservicer. This could strain agency operations and expose them to losses and associated costs, particularly if the portfolio contained a high percentage of defaulted loans. For example, in 2022, a Ginnie Mae nonbank reverse mortgage issuer failed, and Ginnie Mae took over servicing its portfolio. Ginnie Mae reported that managing this $21 billion portfolio had stretched staff capacity and increased Ginnie Mae’s balance sheet by over 50 percent.

Agencies Have Opportunities to Improve Processes for Assessing Financial Condition of Nonbanks

Ginnie Mae and FHFA have processes to assess the financial condition of nonbanks. However, opportunities exist to improve reliability checks of nonbanks’ financial data, assessment of a key nonbank liquidity risk, and consideration of nonbank stress scenarios.

Agencies Use Nonbank Financial Data to Inform Monitoring, but FHFA’s Data Reliability Checks Are Limited

Nonbanks Submit Financial Data for Monitoring Purposes

Ginnie Mae and FHFA use data from the Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form (MBFRF)—an electronic reporting system—to monitor the financial condition of nonbanks.[31] Ginnie Mae and the enterprises require their approved nonbank issuers and seller/servicers, respectively, to submit unaudited financial data quarterly (monthly for certain large nonbanks) through the web-based form.[32] The reporting process is managed by a consortium composed of Ginnie Mae, the enterprises, and the Mortgage Bankers Association. MBFRF includes over 1,500 fields for nonbanks to self-report their financial data, including information on assets, equity and liabilities, income, expenses, loan originations, and debt facilities. The form also includes automated controls to prevent users from submitting data with certain types of errors or warn them of potential errors.

Both agencies have identified reliability issues in the data. FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials said they sometimes see errors in MBFRF submissions like financial information entered in the wrong denomination (for instance, as a whole number when the form calls for data in thousands) and required fields left blank.

The consortium has undertaken initiatives to improve MBFRF data quality. For example, beginning in 2020, form filers were required to have their chief executive officer or chief financial officer (or equivalent) certify the accuracy of the data submissions. FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials said MBFRF data quality improved after this requirement went into effect but noted that errors still occurred.

Ginnie Mae Has Processes to Check Data Reliability and Correct Issues

To manage potential data reliability issues in MBFRF data, Ginnie Mae developed a data quality enhancement framework for issuers. The framework calls for Ginnie Mae to review MBFRF data submissions each quarter using automated validations, most of which involve groups of MBFRF fields. The validations generally determine whether the values in those fields are logically consistent, align with previously reported data, and produce reasonable financial ratios. Ginnie Mae flags data that do not pass the validations for potential follow-up. We found that, in the third quarter of 2024, 75 percent of issuers’ MBFRF submissions had at least one flag and 9 percent had three or more flags.

Ginnie Mae officials said that each quarter, they contact issuers that receive flags in priority areas to request clarification or resubmissions.[33] In addition, the officials said they check the reliability of MBFRF data by cross checking it with other sources, such as annual audited financial statements.

FHFA Does Not Have Procedures to Assess Data Quality

FHFA analyzes MBFRF data to develop its nonbank watch lists and other nonbank financial analyses.[34] However, FHFA’s process to assess the quality of the MBFRF data is limited. FHFA officials said that they do not conduct specific data reliability checks of the data. Instead, they said staff identify errors in the course of performing calculations for analytical products. For example, they may identify financial ratios that are obviously unreasonable because the calculations are based on missing values or on data in the wrong denomination. FHFA officials said they address the errors by removing the nonbank from their analysis or by correcting errors they can easily diagnose.

However, the MBFRF data can contain other types of errors. We identified a number of seller/servicers on FHFA’s nonbank watch list for the first quarter of 2024 that also were Ginnie Mae issuers. According to Ginnie Mae’s review of MBFRF data, most of these nonbanks had at least one data flag in their submissions, indicating potential issues with the consistency and reasonableness of the data. The flagged items included variables FHFA uses to help determine its watch list. FHFA officials said they had not discussed Ginnie Mae’s data checks with Ginnie Mae officials.[35]

FHFA does not have written procedures to assess the reliability of MBFRF data or address any known data errors. This is inconsistent with the agency’s operating procedures for work products involving risk monitoring and financial analysis. The operating procedures state analysts are to ensure that the facts and financial data used to support the analyses are accurate and from a reliable source.[36]

FHFA officials described FHFA as a user, but not an owner, of the MBFRF data and noted that this role limits their ability to improve the data. The officials also said the enterprises are responsible for ensuring the reliability of the data through their work with the MBFRF consortium and that FHFA has limited resources to assess the data. Additionally, they said they find few data errors and that the errors are concentrated among the smallest servicers.[37]

However, these factors do not eliminate the need for or prevent the adoption of procedures to assess the reliability of the MBFRF data. FHFA’s detection of few errors may partially reflect the limited scope of its existing data assessments. Additionally, conducting risk-based assessments—for example, focusing on the most consequential data elements—could help mitigate resource constraints. Without procedures on how to assess MBFRF data quality and to treat potentially unreliable data, FHFA lacks reasonable assurance that its nonbank financial monitoring tools are producing dependable results.

Agencies’ Nonbank Watch Lists Have Not Fully Addressed a Key Liquidity Risk

Agencies’ Watch Lists Cover Important Categories of Financial Metrics

Ginnie Mae and FHFA have processes to regularly assess selected financial metrics to assign scores to nonbanks, and the agencies use these scores to create watch lists—formal compilations of entities that pose relatively higher financial or operational risks.[38]

Each agency’s scoring process broadly aligns with aspects of rating systems used by federal banking regulators to assess the strength of depository institutions and by credit rating agencies to assess the creditworthiness of nonbanks.[39] The processes also include financial metrics relevant to certain nonbank vulnerabilities previously discussed: liquidity challenges, concentration in mortgage assets, and high leverage.

Despite these similarities, the agencies develop and use their watch lists in somewhat different ways that reflect their specific roles and operations.

· Ginnie Mae. In addition to selected financial metrics, Ginnie Mae considers credit rating agency ratings of the issuers and qualitative assessments by Ginnie Mae analysts to determine the issuer scores that underlie the watch list. The qualitative assessments include manual credit reviews of certain issuers that consider supplemental financial or qualitative information. These reviews can result in changes to issuer scores and watch list placement. According to Ginnie Mae policy, issuers on the watch list may be subject to enhanced monitoring and management tools. (See app. II for information on the types of tools Ginnie Mae may use for nonbanks on its watch list).

· FHFA. FHFA bases its watch list determinations on scores produced by an algorithm that uses selected financial metrics and on the amount of funds potentially at risk (exposure) if a nonbank were to default.[40] FHFA officials responsible for managing the watch list process said they do not make scoring adjustments based on analyst judgment or qualitative factors. FHFA officials said the watch list helps them oversee the enterprises by providing perspectives on the enterprises’ nonbank risks that are independent of the enterprises’ own risk analyses.

Ginnie Mae’s Qualitative Assessments of Nonbanks’ Credit Lines Were Not Consistent

As part of the issuer scoring process, Ginnie Mae analysts are to assess nonbanks’ warehouse credit lines through manual credit reviews. Ginnie Mae officials said they use this more qualitative approach because establishing meaningful quantitative thresholds for warehouse lending risk (drawing the line between more and less risky) would be difficult. They also said they were not aware of published research to support such thresholds. Representatives from a major credit rating agency with whom we spoke expressed similar views.

Although the manual review process avoids these technical challenges, Ginnie Mae’s process does not provide reasonable assurance that analysts consistently consider all key components of warehouse lending risk. Based on FSOC’s 2024 report, research literature, and an interview with a major credit rating agency, we identified five key risk components: diversification, utilization, maturity, covenant violations, and committed amount (see sidebar).

|

Components of Warehouse Lending Risk Diversification refers to the number of warehouse credit lines a nonbank has. More warehouse lines may indicate greater ability to fund operations and less reliance on a specific lender. Utilization refers to the amount of available warehouse credit used. Higher usage can indicate limited liquidity because less warehouse credit remains available. Maturity indicates the warehouse credit line’s expiration date. Multiple lines expiring within a short time frame could strain a nonbank’s liquidity. Covenant violations are violations of certain financial condition and collateral requirements that warehouse lenders placed on nonbanks. Such violations may indicate that a nonbank is at risk of losing warehouse funding. Committed amount refers to the amount of funding that can be altered only when the credit line expires or a nonbank is not compliant with lending covenants. In contrast, a lender may reprice or restructure an uncommitted warehouse credit line at any time (for example, by raising interest rates, changing types of acceptable collateral, or curtailing or canceling). Committed credit lines can therefore be more stable sources of financing. Source: GAO analysis of federal, industry, and academic publications. | GAO‑26‑107436 |

Ginnie Mae analysts performed credit reviews but did not always demonstrate consideration of certain warehouse lending risks. Among the reviews performed for a sample of 10 nonbank issuers in the fourth quarter of 2024, more than half did not mention the amount of committed warehouse lines, and some did not mention whether there were any covenant violations.[41] Both pieces of information are part of nonbanks’ required MBFRF data submissions.

Ginnie Mae does not have guidance requiring analysts to review and consider all five warehouse lending risks in issuer credit risk reviews. Without a more consistent and comprehensive approach to reviewing issuers’ warehouse credit lines, Ginnie Mae may overlook factors that could affect issuer risk scores and watch list placement. In turn, this could result in some higher-risk nonbanks not being subject to enhanced Ginnie Mae monitoring or corrective actions

FHFA’s Watch List Process Has Not Considered All Components of Warehouse Lending Risk

FHFA assesses nonbanks’ warehouse lending risk through the liquidity portion of its risk score algorithm but does not include all five key risk components we identified (see sidebar above). Although the algorithm has metrics for warehouse line diversification and utilization, it does not include metrics for the number of covenant violations, committed amount, or warehouse line maturity.

FHFA officials said they based these aspects of the algorithm and associated scoring thresholds on internal enterprise white papers and on past professional experience in monitoring nonbanks. They said the two components they include are early warning indicators of potential liquidity problems and that adding additional components could be cumbersome and likely would not change the risk scores significantly.

However, without testing these assumptions, FHFA may be omitting indicators that could help it evaluate counterparty risks to the enterprises. Although incorporating the other three risk components of warehouse lending into FHFA’s scoring approach could pose challenges, further assessment could help determine the potential feasibility and utility of doing so.

Agencies Examine a Limited Range of Scenarios to Analyze Potential Stresses on Nonbanks

Ginnie Mae and FHFA Perform Scenario Analyses to Assess Potential Economic Risks

Ginnie Mae and FHFA both conduct analyses to assess the potential effect of different economic scenarios on the financial health of nonbanks. Scenario analysis assesses potential future outcomes resulting from plausible and possibly adverse events. One type of a scenario analysis is a stress test, which assesses how a company would perform under an extreme scenario, usually with a severe impact. Many financial institutions and regulators use stress tests as a risk-management tool.

Ginnie Mae routinely conducts stress tests of all its active issuers, including nonbanks. The results provide early indications of potential programmatic noncompliance by issuers.

FHFA analyzes a judgmental selection of the largest 15–20 nonbank enterprise seller/servicers every quarter. FHFA’s scenario analysis helps the agency understand the relationship between the value of mortgage servicing rights and nonbank capital, as well as which nonbanks might become insolvent under stress conditions.

Ginnie Mae’s Stress Testing Framework Does Not Consider Use of Additional Scenarios

To help manage its counterparty risk, Ginnie Mae performs detailed stress tests involving projections of many economic variables, but the agency’s stress testing framework does not consider a variety of severe scenarios. Ginnie Mae’s stress test projects issuers’ financial performance over eight quarters under two scenarios—expected and stressed—developed by a major economics research and analytics firm. The expected scenario is based on current conditions and the forecaster’s views of where the economy is headed. The stressed scenario simulates a protracted recession.[42]

But relying on a single stress scenario does not fully align with federal banking regulators’ stress testing principles, which call for using enough scenarios to explore the range of potential outcomes.[43] Similarly, the International Monetary Fund’s stress testing principles note that future stress periods are uncertain and could be represented by a range of stress factors, each with a different likelihood of occurrence.[44]

Ginnie Mae officials said they only pursue stress scenarios with predictive value and that inform the agency’s monitoring strategy, program requirements, or capital adequacy and resource planning. They said they occasionally developed custom stress scenarios for specific situations, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, consideration of alternative scenarios is not part of Ginnie Mae’s regular stress testing framework.

One potentially consequential scenario is stagflation.[45] In October 2024, a former president of Ginnie Mae said a scenario that poses substantial financial risk for nonbanks is not a severe recession, but a mild recession in which mortgage delinquencies rise but interest rates do not decrease.[46] Federal Reserve researchers with whom we spoke echoed this view, noting that stagflation would be particularly stressful for nonbanks because it would disrupt the hedge between the mortgage servicing and origination sides of their business. In a traditional recession, higher unemployment increases borrower delinquencies and reduces the value of mortgage servicing, but falling interest rates support ongoing mortgage originations. In a stagflation scenario, delinquencies also rise but interest rates remain high (to curb inflation) and likely would decrease originations.[47]

Ginnie Mae’s focus on a single stress scenario does not reflect a fuller range of potential outcomes that could result from stagflation or other types of economic stresses. Without consideration of additional possible scenarios, Ginnie Mae may not be thoroughly assessing all relevant risks to its issuers and its portfolio and whether a scenario may warrant a mitigation plan.

FHFA’s Scenario Analysis Focuses on Mortgage Servicing Rights

FHFA’s scenario analysis focuses on the potential effect of changes in the value of nonbanks’ mortgage servicing rights—a key asset for many nonbanks. FHFA analyzes how a set of pre-determined declines in the value of mortgage servicing rights would affect a nonbank’s capital. FHFA also calculates how severe a decline in the value of mortgage servicing rights would be needed to bring a nonbank out of compliance with enterprise capital requirements.[48] FHFA officials said they analyze changes in the value of mortgage servicing rights because these assets generally constitute a significant portion of nonbanks’ balance sheets and their value can change rapidly.[49]

Although FHFA does not conduct broader scenario analyses of its nonbank seller/servicers, nonbank seller/servicers have started submitting stress tests to the enterprises under FHFA’s direction. In 2022, FHFA announced updated minimum financial eligibility requirements for enterprise seller/servicers, including development of capital and liquidity plans. As part of these plans, large nonbanks (those servicing at least $50 billion in unpaid mortgage principal) must perform annual liquidity stress tests, including an assessment of mortgage servicing rights values, in an adverse scenario.

Nonbanks provided the enterprises the results of their first stress tests in April 2024, according to FHFA officials. FHFA officials said nonbanks were allowed to use their own stress assumptions for those tests but that, for future tests, the enterprises will develop common assumptions for all participating nonbanks to use.

Conclusions

The critical role of nonbanks in the housing finance system and the serious potential consequences of nonbank failures underscore the importance of effective federal monitoring of these companies. Ginnie Mae and FHFA have developed monitoring processes to help manage the risks of federally backed MBS programs, but opportunities remain for improvement.

· FHFA could strengthen assessment of the MBFRF data it uses to analyze the financial condition of nonbanks. By developing procedures for assessing the reliability of the data and treating potentially unreliable data, FHFA would have greater assurance that its analyses produce dependable monitoring information.

· Both agencies could enhance how they evaluate warehouse lending risks. By developing more comprehensive and explicit guidance for reviewing all risk components, Ginnie Mae could more consistently assess risks in its manual credit reviews. By assessing ways to incorporate additional components of warehouse lending risk into its risk score algorithm, FHFA could enhance its assessment of counterparty risk to the enterprises. For both agencies, better evaluation of warehouse lending risk could improve the effectiveness of their watch lists.

· Ginnie Mae’s stress testing framework does not capture the range of stresses nonbanks and Ginnie Mae could face. Formally considering alternative scenarios could enhance Ginnie Mae’s planning for stress events beyond the protracted recession scenario it currently uses.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of four recommendations—two to FHFA and two to Ginnie Mae. Specifically:

The Director of FHFA should ensure that the Counterparty Risk and Policy Branch develops procedures for assessing the reliability of MBFRF data used for monitoring activities and for treating potentially unreliable data. (Recommendation 1)

The President of Ginnie Mae should ensure that the Office of Enterprise Risk develops guidance requiring analysts to consistently review key components of warehouse lending risk, including the committed funding amount, as part of the manual credit review process. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of FHFA should ensure that the Counterparty Risk and Policy Branch assesses the feasibility and utility of incorporating all key components of warehouse lending risk in its risk scoring process. (Recommendation 3)

The President of Ginnie Mae should ensure that the Office of Enterprise Risk incorporates consideration of alternative economic scenarios into Ginnie Mae’s stress testing framework. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided FHFA, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Department of the Treasury a draft of this report for their review and comment. FHFA and Ginnie Mae (Department of Housing and Urban Development) provided comment letters reprinted in appendixes III and IV, respectively.

FHFA agreed with our recommendations and said it will take actions to address them by September 30, 2026. Ginnie Mae also agreed with our recommendations and said it is in the process of implementing them. In addition, Ginnie Mae and FSOC (Treasury) provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the Secretary of the Treasury, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Jill Naamane at NaamaneJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Sincerely,

Jill Naamane

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

This report examines (1) how the role of nonbanks in the housing finance system evolved from 2014 to 2024 and their benefits and risks for the system, and (2) the extent to which Ginnie Mae and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) developed selected processes for assessing the financial condition of nonbanks approved to participate in agency mortgage-backed security (MBS) programs.

For the first objective, we analyzed Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) and Inside Mortgage Finance data to identify trends in nonbank mortgage origination and servicing, respectively.

· HMDA requires covered mortgage lenders to collect and report mortgage lending data to allow regulators and others to identify possible discriminatory lending patterns and enforce fair lending laws. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau compiles and publishes the data. We also used the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s HMDA lender file—a supplementary dataset that matches financial institution subsidiaries to their parent institution—to help distinguish between bank and nonbank lenders.[50] In this report, we define nonbank mortgage companies as those that engage primarily in activities related to home mortgage loans, including origination and servicing, but do not take deposits. We defined banks as financial institutions that take deposits.

We analyzed HMDA data on residential single-family (one-to-four family) home purchase loans originated from 2014 through 2024.[51] Specifically, we analyzed trends in (1) the dollar volume of bank and nonbank originations, (2) the number of nonbank originations by borrower race or ethnicity, and (3) the number of nonbank originations by income. For analysis of race and ethnicity, we classified borrowers first by ethnicity (Hispanic borrowers of any race) and then by race for non-Hispanic borrowers.[52] We classified borrowers by income using the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s estimated area median family incomes for the loan origination location.[53] For our analysis, we defined low- to moderate-income borrowers to have reported incomes less than 80 percent of the area median, middle-income borrowers to have reported incomes greater than or equal to 80 percent and less than 120 percent of the area median, and high-income borrowers to have reported incomes greater than or equal to 120 percent of the area median.

To assess the reliability of the HMDA data, we reviewed related documentation, tested for outliers and errors, and reviewed data reliability assessments of HMDA data from prior GAO work. For the lender file, we tested the consistency of the lender type designations with information on lenders’ websites and interviewed the file’s developer. We determined the HMDA data and HMDA lender file were sufficiently reliable to describe trends in nonbank mortgage origination and the characteristics of nonbank borrowers.

· Inside Mortgage Finance provides news and statistics about the residential mortgage business. We used data from this source to analyze 2014–2024 trends in the dollar volume of (1) single-family mortgage servicing outstanding by market segment, (2) loans in agency MBS serviced by nonbanks, and (3) the 10 largest servicers of agency MBS.[54] We assessed the reliability of these data by interviewing representatives from Inside Mortgage Finance, reviewing the data for outliers and errors, comparing the data to other sources, and reviewing reliability assessments of similar Inside Mortgage Finance data from prior GAO work. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable to describe trends in the composition of the mortgage servicing market and the role of nonbanks in agency MBS servicing.

To identify the benefits and risks of nonbanks to the housing finance system, we reviewed studies from federal agencies, academia, and public policy research organizations. These included the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s (FSOC) May 2024 report on nonbank mortgage servicing and prior GAO reports.[55] We identified federal studies by searching agency websites. We identified academic studies and other public policy research using Google Scholar and searching for key terms like “nonbank” and “independent mortgage bank.” We focused on material published from 2016 (the year of our last report specifically about nonbanks) through April 2024 and examined summary-level information to identify studies relevant to our work.

For our second objective, we focused on three processes Ginnie Mae and FHFA use to evaluate the financial condition of nonbanks: (1) assessing the reliability of data used for nonbank monitoring and analysis; (2) establishing and maintaining watch lists; and (3) conducting scenario analyses. We selected these processes because they are relevant to both agencies and because of their importance for identifying nonbanks that pose a higher default risk or that may struggle under adverse economic conditions.[56]

· Data reliability. We reviewed documents governing nonbanks’ submission of financial data, including the data dictionary for the Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form. We also reviewed Ginnie Mae and FHFA documents related to their reliability assessments of these data and information on the results of their assessments. We compared their assessment processes against relevant agency criteria, including Ginnie Mae’s Model Risk Management Policy and FHFA’s Operating Procedures Bulletin for Non-Examination Supervisory Work Products. Additionally, because FHFA’s assessment process was the more limited of the two, we determined whether Ginnie Mae had identified potential errors in data submitted by Ginnie Mae nonbank issuers that were also enterprise seller/servicers.[57] Specifically, we determined how many seller/servicers on FHFA’s watch list for the first quarter of 2024 (developed using the Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form data) Ginnie Mae had flagged for potential data errors in the same period. Our report omits certain details of this analysis because Ginnie Mae determined the information was sensitive and required protection from public disclosure.

· Watch lists. We reviewed procedures for each agency’s watch list process. We also reviewed documentation on the financial metrics and related scoring processes each agency uses to make watch list determinations. We assessed the extent to which Ginnie Mae’s and FHFA’s financial metrics aligned with key aspects of risk-rating systems used by federal banking regulators and credit rating agencies, as well as key nonbank vulnerabilities identified in the first objective.

Because nonbanks’ reliance on warehouse lines of credit is a significant risk factor, we also assessed the extent to which each agency’s watch list process considered five components of warehouse lending risk we identified from FSOC’s May 2024 report, a research paper on nonbank vulnerabilities to liquidity pressures, and an interview with representatives from Moody’s Ratings (a major credit rating agency that rates a number of nonbanks).[58]

We also determined whether Ginnie Mae analysts demonstrated consideration of all five components as part of their manual credit reviews. Specifically, we assessed manual reviews of a sample of 10 nonbank issuers in the fourth quarter of 2024. Our report omits certain details of this analysis because Ginnie Mae determined the information was sensitive and required protection from public disclosure. Because FHFA considers warehouse lending risk as part of its risk score algorithm, we determined whether the algorithm included all five components.

· Scenario analyses. We reviewed documents from each agency pertaining to their analysis of nonbanks under economic stress scenarios. For Ginnie Mae, we reviewed documentation on the agency’s stress testing framework. This included information on the economic model, economic scenarios, and procedures. We also compared Ginnie Mae’s stress testing scenarios against stress testing principles from federal banking regulators and the International Monetary Fund.[59] For FHFA, we reviewed the agency’s procedures for and results of analyses simulating a decline in the value of nonbanks’ mortgage servicing rights. Because FHFA’s scenario analyses are not broad-based stress tests, we reviewed FHFA’s implementation of the procedures but did not assess the procedures against stress testing principles.

For both objectives, we interviewed officials from Ginnie Mae, FHFA, FSOC, and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. We also interviewed representatives from the Mortgage Bankers Association (a leading industry group), Conference of State Bank Supervisors (which coordinates states’ supervision of nonbank mortgage companies), National Consumer Law Center, and Moody’s Ratings, as well as two former senior FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials. We selected these stakeholders because they had published work on nonbanks since 2020.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Ginnie Mae’s tools for addressing capital or liquidity challenges of issuers on its watch list include the following:[60]

· Enhanced monitoring and management. Ginnie Mae may consider placing an issuer into enhanced monitoring and management status if the issuer is at risk of default, extinguishment, and termination due to capital, operational, or compliance challenges.

· Special situation issuer. If an issuer under an enhanced monitoring and management plan does not properly complete the tasks and requirements in the plan, Ginnie Mae may designate it as a special situation issuer. This designation subjects the issuer to additional compliance or risk considerations, such as nonstandard communication protocols or enhanced monitoring.

· Unilateral notifications. Ginnie Mae uses unilateral notifications to impose enhanced liquidity and capital requirements on issuers experiencing financial hardship. Ginnie Mae issued such notifications in 2020–2024, according to agency officials.

GAO Contact

Jill Naamane, naamanej@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Steven Westley (Assistant Director), Miranda Berry (Analyst in Charge), Christopher Lee, Marc Molino, Yann Panassie, Vincent Patierno, and Barbara Roesmann made significant contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Nonbank financial institutions offer consumers financial products or services but do not take deposits. In this report, we generally use nonbanks to refer to nonbank mortgage companies (those that engage primarily in activities related to home mortgage loans, including origination and servicing) and focus on loans for single-family homes.

[2]Ginnie Mae is a component of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are congressionally chartered, for-profit, shareholder-owned corporations that have been under FHFA conservatorships since 2008.

[3]GAO, Nonbank Mortgage Servicers: Existing Regulatory Oversight Could Be Strengthened, GAO‑16‑278 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016); and Housing Finance System: Future Reforms Should Consider Past Plans and Vulnerabilities Highlighted by Pandemic, GAO‑22‑104284 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2022).

[4]Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024 (Washington, D.C.: May 10, 2024).

[5]MBS with enterprise or Ginnie Mae guarantees are collectively known as agency MBS. The enterprises guarantee the timely payment of interest and principal on MBS they issue. While the enterprises are in conservatorship, the federal government assumes the responsibility for losses they incur. Ginnie Mae provides an explicit federal guarantee of the timely payment of principal and interest to security holders of MBS backed by loans insured or guaranteed by federal agencies.

[6]GAO, Nonbank Mortgage Companies: Greater Ginnie Mae Involvement in Interagency Exercises Could Enhance Crisis Planning, GAO‑25‑107862 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 31, 2025). We recommended that Ginnie Mae develop processes for participating in interagency coordination exercises and for incorporating lessons learned into its strategy for managing nonbank failures. Ginnie Mae neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendation and had not implemented it as of December 2025.

[7]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[8]We assessed the reliability of these data by reviewing related documentation, interviewing officials, and testing for outliers and errors. We determined these data were sufficiently reliable to describe trends in mortgages originated and serviced by nonbanks, as well as the characteristics of nonbank borrowers. The 2024 data were the most recent available at the time of our review.

[9]Both agencies have other processes or tools to assess the financial risks of nonbanks. For example, Ginnie Mae has a tool that allows financial institutions (including nonbanks) that participate in the agency’s MBS program to measure their operational and default performance relative to their peers.

[10]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Mortgage Companies – State Authorities (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 1, 2024).

[11]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Mortgage Companies – State Authorities. Examples of state enforcement actions include revoking a nonbank’s license and issuing cease and desist orders.

[12]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Final Model State Regulatory Prudential Standards for Nonbank Mortgage Servicers (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2021).

[13]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Nonbank Mortgage Servicer Prudential Standards; accessed December 17, 2025, at https://www.csbs.org/nonbank-mortgage-servicer-prudential-standards.

[14]FSOC has the authority to subject a nonbank financial company to federal prudential supervision if FSOC determines that material financial distress at the company could pose a threat to the nation’s financial stability. 12 U.S.C. § 5323; 12 C.F.R. pt. 1310. In its December 2025 annual report, FSOC stated that no nonbank financial companies were subject to this designation as of the date of the report. See Financial Stability Oversight Council, 2025 Annual Report (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2025).

[15]Ginnie Mae can declare an issuer in default for certain specified causes and exercise remedies, in accordance with governing statutes, regulations, and contracts. See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 1721(g)(1); 24 C.F.R. § 320.15; Ginnie Mae MBS Guide (5500.3, Rev. 1), ch. 23. Other examples of defaults include impending insolvency, unauthorized use of custodial funds, and submission of false reports.

[16]“Seller/servicer” is the enterprises’ term for institutions approved to sell loans to the enterprises, service enterprise loans, or both.

[17]Federal Housing Finance Agency, Office of the Inspector General, DER Provided Effective Oversight of the Enterprises’ Nonbank Seller/Servicers Risk Management But Needs to Develop Policies and Procedures for Two Supervisory Activities, AUD-2024-003 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2024).

[18]See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 5514.

[19]The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service also have mortgage insurance or guarantee programs.

[20]Nonagency MBS refer to MBS issued by private institutions (primarily investment banks) backed by mortgages that are not federally insured or guaranteed and do not conform to the enterprises’ requirements.

[21]For example, savings and loan associations played a leading role in residential mortgage lending for multiple decades. See George G. Kaufman, “The Incredible Shrinking S&L Industry,” Chicago Fed Letter, no. 40 (Chicago, Ill.: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, December 1990).

[22]GAO‑16‑278; and Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024.

[23]Andreas Fuster, Matthew Plosser, et al., The Role of Technology in Mortgage Lending, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report No. 836 (New York, N.Y.: February 2018).

[24]GAO‑16‑278; and Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024.

[25]Low- to moderate-income borrowers are those with incomes less than 80 percent of the area median. We defined middle-income borrowers as those with incomes greater than or equal to 80 percent and less than 120 percent of the area median, and high-income borrowers as those with incomes greater than or equal to 120 percent of the area median.

[26]See, e.g., 12 C.F.R. § 201.4(a)-(c) and pt. 1266, subpt. A. See also Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024, 44; Federal Housing Finance Agency, FHLBank System at 100: Focusing on the Future (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 7, 2023), 63.

[27]Warehouse lending is a process by which lenders extend lines of credit to nonbanks to fund mortgage loans until the loans can be securitized. Warehouse lenders can adjust the terms or cancel lines if nonbanks violate any of the covenants of the contract, including maintaining certain levels of net worth and profitability. You Suk Kim, et al., “Liquidity Crises in the Mortgage Market,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2018-016 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 7, 2018).

[28]GAO, Housing Finance System: Future Reforms Should Consider Past Plans and Vulnerabilities Highlighted by Pandemic, GAO‑22‑104284 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2022).

[29]Subservicers perform servicing and loan administration activities (such as payment collection) on behalf of the servicer but do not hold mortgage servicing rights.

[31]Ginnie Mae uses call report data to monitor the financial condition of issuers that are depository institutions.

[32]Ginnie Mae and the enterprises also require issuers and seller/servicers to submit annual audited financial statements.

[33]According to Ginnie Mae officials, the quarterly outreach focuses on priority areas to help make the process manageable. The priority areas may vary from quarter to quarter.

[34]Watch lists are formal compilations that identify nonbanks with relatively higher risks.

[35]Our report omits details on the number of nonbanks and specific variables included in this analysis because Ginnie Mae determined the information was sensitive and required protection from public disclosure. This report uses broader narrative descriptions in lieu of such information.

[36]The procedures are specifically for nonexamination supervisory work products, meaning those not related to FHFA’s examinations of regulated entities such as the enterprises.

[37]For example, in the third quarter of 2024, FHFA removed 16 nonbanks from a population of over 600 seller/servicers because of data errors.

[38]Ginnie Mae includes all of its issuers (banks and nonbanks) in its watch list process, whereas FHFA limits its process to nonbanks. In addition, Ginnie Mae may place issuers on its watch list because of compliance or operational issues, while FHFA’s watch list is based solely on financial metrics.

[39]Federal banking regulators use the Uniform Financial Institutions Rating System, also known as CAMELS. The banking regulators rate an institution on each CAMELS component (capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk).

[40]An algorithm is a set of rules a computer follows to compute an outcome.

[41]Our report omits details on the characteristics and number of nonbanks for which different risks were not mentioned because Ginnie Mae determined the information was sensitive and required protection from public disclosure. This report uses broader narrative descriptions in lieu of such information.

[42]Both scenarios use projections of economic variables such as house prices, unemployment rates, and interest rates.

[43]Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Guidance on Stress Testing for Banking Organizations with Total Consolidated Assets of More Than $10 Billion, SR Letter 12-7 (May 14, 2012).

[44]International Monetary Fund, Macrofinancial Stress Testing—Principles and Practices (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 22, 2012).

[45]Stagflation is an economic cycle characterized by slow growth and a high unemployment rate accompanied by inflation.

[46]Monica Hogan, “Ginnie Working to Help Nonbanks With Liquidity,” Inside Mortgage Finance (Oct. 17, 2024).

[47]Past periods of stagflation have differed in depth and duration. Thus, the range of potential outcomes from a stagflation scenario may also vary. See Azhar Iqbal and Nicole Cervi, “Characterizing Stagflation into Mild, Moderate and Severe Episodes: A New Approach,” World Economics Journal, vol. 25, no. 1 (January–March 2024).

[48]This type of analysis is sometimes called a reverse stress test because it assumes a negative outcome and identifies scenarios that would lead to that outcome.

[49]The 2024 FSOC report found that mortgage servicing rights are typically about 10–30 percent of nonbanks’ assets.

[50]This file was developed by economist Robert Avery, currently a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and formerly an official at FHFA and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

[51]We limited the data to first-lien-secured and site-built loans and excluded open-end line of credit loans and loans primarily intended for a business or commercial purpose to ensure consistency across all years of analysis. We excluded loans of $20 million or more (in current dollars) from our analysis because we determined that these outlier loan amounts were likely to exhibit higher rates of errors.

[52]Specifically, we classified borrowers first based on the ethnicity identified in each origination record, and then by race for non-Hispanic borrowers based on the first (of up to five) race fields in each origination record (White, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander). In our analysis of trends by race and ethnicity, we excluded a small subset of origination records for which ethnicity was missing or race was missing for non-Hispanic borrowers.

[53]The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council calculates median family income by either metropolitan statistical area/metropolitan division or statewide nonmetropolitan statistical area. In our analysis of trends by income, we excluded a small subset of origination records for which area median family income was missing or reported borrower annual income was negative, close to zero, or missing.

[54]Agency MBS are guaranteed by Ginnie Mae or by the government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

[55]Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024 (Washington, D.C.: May 10, 2024). Also see GAO, Nonbank Mortgage Servicers: Existing Regulatory Oversight Could Be Strengthened, GAO‑16‑278 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016); Ginnie Mae: Risk Management and Staffing-Related Challenges Need to Be Addressed, GAO‑19‑191 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 3, 2019); and Housing Finance System: Future Reforms Should Consider Past Plans and Vulnerabilities Highlighted by Pandemic, GAO‑22‑104284 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2022).

[56]Both agencies have other processes or tools to assess the financial risks of nonbanks.

[57]“Issuer” is Ginnie Mae’s term for approved institutions that pool and securitize eligible loans and issue Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS. “Seller/servicer” is the enterprises’ term for institutions approved to sell loans to the enterprises, service enterprise loans, or both. The enterprises are under FHFA conservatorships.

[58]Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing 2024; and You Suk Kim, et al., “Liquidity Crises in the Mortgage Market,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2018-016 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 7, 2018).

[59]Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Guidance on Stress Testing for Banking Organizations with Total Consolidated Assets of More Than $10 Billion, SR Letter 12-7 (May 14, 2012); and International Monetary Fund, Macrofinancial Stress Testing—Principles and Practices (Aug. 22, 2012). We did not compare FHFA’s scenario analysis to these criteria because FHFA’s scenario analysis is not a full stress test.

[60]According to Ginnie Mae officials, the agency’s ability to monitor nonbanks is limited by its lack of express authority to regulate those institutions. GAO, Nonbank Mortgage Companies: Greater Ginnie Mae Involvement in Interagency Exercises Could Enhance Crisis Planning, GAO-25-107862 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 31, 2025), 18.