COAST GUARD

Actions Needed to Improve Maritime Interdictions

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Heather MacLeod at MacLeodH@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The Coast Guard, a multi-mission military service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), uses its resources—including assets such as vessels and aircraft—to conduct its drug and migrant interdiction missions. Given limited resources, the Coast Guard made tradeoffs to address a significant increase in maritime migration levels that began in 2021. Specifically, it redirected assets to migrant interdiction that it had originally allocated to other missions, such as drug interdiction. This impacted its ability to conduct those other missions.

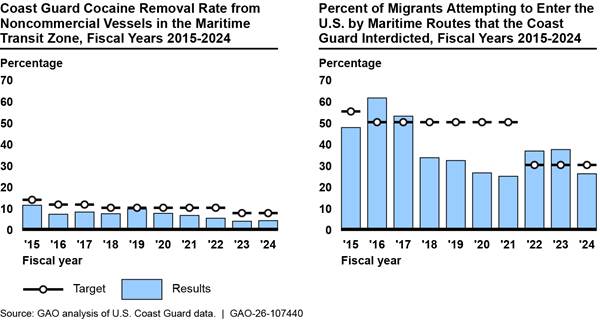

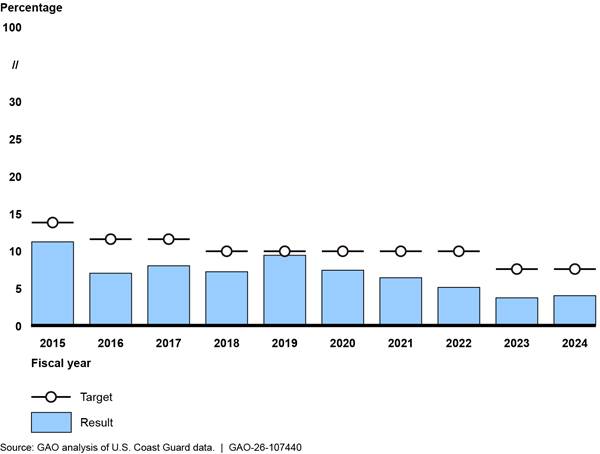

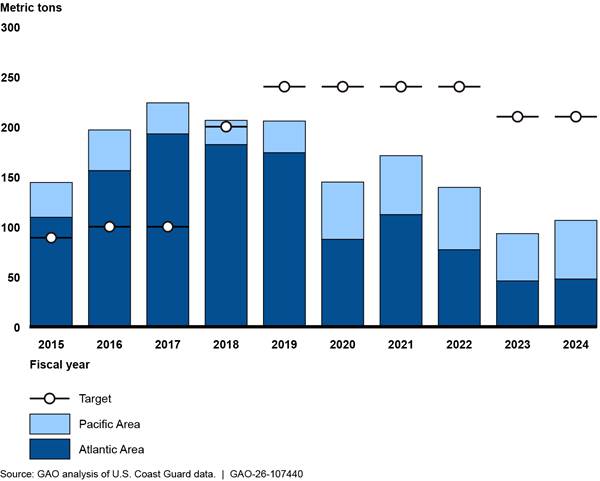

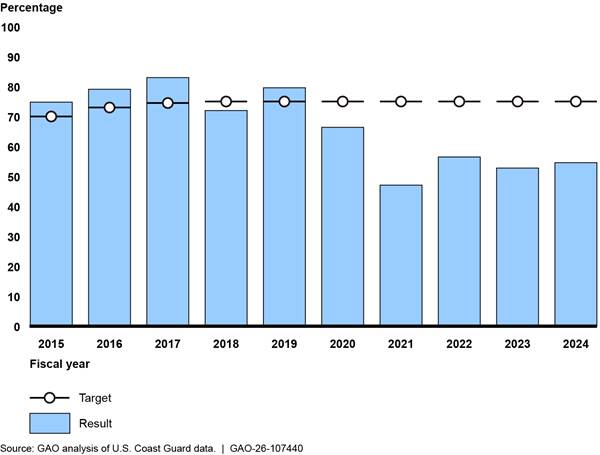

The Coast Guard did not meet its primary drug interdiction performance target in fiscal years 2015 through 2024, and did not meet its primary migrant interdiction target for 6 years during the same period. See figures below. Coast Guard officials said neither primary measure effectively assesses its efforts. Thus, it began to implement new drug interdiction measures in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 to better assess its performance. As of July 2025, the Coast Guard had identified which would be its new primary drug interdiction measures. In addition, the Coast Guard is in the initial stages of developing new migrant interdiction performance measures, but as of July 2025 had not yet implemented them. Doing so would better position the Coast Guard to provide decision makers with relevant information to make future resource decisions.

The DHS Operation Vigilant Sentry task force provides a key coordination mechanism for the Coast Guard and about 10 federal partners responsible for maritime migrant interdiction. The Coast Guard and its federal partners generally followed seven of GAO’s eight leading collaboration practices identified in prior work. However, the task force did not fully share information on lessons learned. By implementing a process to identify and address lessons learned from events and sharing related reports with relevant federal partners, the task force would better address areas for improvement. This process could also help better manage fragmentation by ensuring all partners operate with similar information to support the migrant interdiction mission.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Coast Guard is the lead federal maritime agency responsible for interdicting illicit drug traffic and enforcing U.S. immigration laws and policies at sea. In fiscal years 2022 and 2023, it responded to the highest maritime migration levels in over 30 years. It has been conducting a migrant interdiction surge operation since August 2022. As of November 2025, the surge operation was ongoing.

GAO was asked to review the Coast Guard’s drug and migrant interdiction missions. This report examines, among other things: (1) the extent the Coast Guard met its drug and migrant interdiction mission performance targets in fiscal years 2015–2024, (2) how its maritime migration surge operation in fiscal years 2022–2024 affected its ability to perform its other statutory missions, and (3) the extent it coordinated with federal partners to conduct maritime migrant interdiction.

GAO analyzed Coast Guard drug and migrant interdiction performance data, and reviewed relevant policies and documentation. GAO also conducted in-person site visits to Miami, Florida and San Diego, California and interviewed Coast Guard officials and DHS partner agencies to discuss drug and migrant interdiction operations and related coordination efforts.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to DHS to (1) implement new migrant interdiction performance measures for the Coast Guard and (2) implement a process for the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force to identify lessons learned from events and share related reports with all relevant federal partners. DHS concurred with both recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

CHNV |

Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans |

|

DHS |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

|

JIATF |

Joint Interagency Task Force |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

USCIS |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 13, 2026

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

Beginning in 2021, unstable conditions and socioeconomic challenges occurring simultaneously in Haiti and Cuba helped drive the highest maritime migration to the U.S. in over 30 years, according to the Coast Guard. From fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024, almost 70,000 migrants attempted to travel across the Caribbean Sea and Florida Straits, often in unseaworthy or overloaded vessels, to reach the U.S.[1] In response, in August 2022, the Coast Guard, in collaboration with a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) task force, initiated a migrant interdiction surge operation—a high-intensity effort launched on short notice.[2] As of November 2025, the 3-year long surge operation was still ongoing.

The Coast Guard, a multi-mission military service within DHS, is the lead federal maritime agency responsible for interdicting illicit drug traffic and enforcing U.S. immigration laws and policies at sea.[3] According to the Coast Guard, its presence—vessels, aircraft, and specialized forces—serves as an enforcement mechanism and deterrent to illicit activity that contributes to instability throughout the Western Hemisphere.[4] In fiscal year 2024, the Coast Guard estimated spending approximately $2.6 billion for its drug interdiction and migrant interdiction missions—about 26 percent of its total estimated operating expenses across its 11 statutory missions.[5]

The U.S. government has identified the trafficking and smuggling of illicit drugs by transnational and domestic criminal organizations as a significant threat to the public, law enforcement, and national security. We have previously reported on longstanding challenges that have hindered the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its drug interdiction and other statutory mission demands. These challenges include (1) declining availability and readiness of its vessels and aircraft, (2) acquisition-associated delays in replacing them, and (3) workforce shortages and retention challenges.[6] We have previously reported that the Coast Guard’s challenge of balancing its varied mission priorities has grown as it is called on to do more with its limited resources.

Given challenges the federal government faces in responding to drug misuse, in March 2021, we added national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse to our High-Risk List. We identified several challenges in the federal government’s response to drug misuse, such as the need for more effective implementation and monitoring, and related ongoing efforts to address the issue, including drug interdiction.[7]

You asked us to review Coast Guard’s efforts for its drug interdiction and migrant interdiction missions. This report examines (1) trends in resources the Coast Guard deployed for its 11 statutory missions in fiscal years 2015 through 2024, (2) the extent the Coast Guard met its annual drug and migrant interdiction mission performance targets in fiscal years 2015 through 2024, (3) how the Coast Guard’s maritime migration surge operation during fiscal years 2022 through 2024 affected its ability to perform its other statutory missions, and (4) the extent the Coast Guard and key federal partners coordinated to conduct maritime migrant interdiction.

To determine the trends in resources the Coast Guard deployed for its 11 statutory missions in fiscal years 2015 through 2024, we analyzed Coast Guard aircraft and vessel operational hour data for each of its statutory missions during this time.[8] To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation, conducted electronic testing of the data, and interviewed program officials. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to report Coast Guard aircraft and vessel operational hours by statutory mission. To determine the Coast Guard’s estimated operating expenses, we analyzed the service’s Mission Cost Model operating expense estimates for its 11 statutory missions.[9] To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation and written responses from relevant officials. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to estimate Coast Guard’s operating expenses across its 11 statutory missions.

To assess the extent the Coast Guard met its annual drug and migrant interdiction mission performance targets, we identified the performance measures Coast Guard used for its drug and migrant interdiction missions during fiscal years 2015 through 2024. We analyzed Coast Guard interdiction performance data and compared these results against the respective performance targets for each year from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation and interviewed Coast Guard program officials and determined the data were sufficiently reliable to report on the Coast Guard’s performance over that time period.

We assessed the Coast Guard’s migrant interdiction performance measures against Coast Guard’s criteria in its Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control, which states that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives and that while performance measures need not be perfect, they must be sufficient for their intended use.[10]

We interviewed Coast Guard headquarters officials to better understand how the Coast Guard determines its performance targets and uses the results of these measures. We also discussed any factors that affected the service’s ability to meet those targets.

To address how the maritime migration surge operation affected the Coast Guard’s ability to perform its other statutory missions, we analyzed Coast Guard data on its drug and migrant interdictions from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation, interviewed program officials, and conducted electronic testing of the data. We found all 10 years of drug interdiction case data to be sufficiently reliable to report on drug seizures from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024. However, we determined that while migrant interdiction case data in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 were sufficiently reliable, there were a high amount of missing case numbers prior to that, in fiscal years 2015 through 2019.[11] For this reason, we found those data to be unreliable and limited our reporting of migrant interdiction outcomes to fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

We also reviewed Coast Guard documentation, including planning and performance documents, such as Strategic Planning Directions and Operational Performance Assessment Reports. These documents provide information on Coast Guard asset commitments, mission performance, and related challenges.

Finally, we interviewed Coast Guard headquarters officials from the Office of Maritime Law Enforcement Policy, and field officials from its two area commands (Pacific and Atlantic) and five of its nine districts, to discuss how the ongoing maritime migration surge operation affected other Coast Guard missions and operations.[12]

We also conducted site visits to Coast Guard locations in Miami, Florida, and San Diego, California. We selected these locations due to the volume of maritime migration in those areas, and their involvement in the maritime migration surge operation in the Caribbean and South Florida Straits. During these site visits, we toured Coast Guard facilities and met with officials at the district, sector, and air station level who had conducted drug interdiction and migrant interdiction operations. While the information obtained from our site visits is not generalizable, it provided valuable insights about the challenges the Coast Guard faced in meeting its drug and migrant interdiction mission demands, particularly during the maritime migration surge operation.

To address the extent the Coast Guard and key federal partners coordinated to conduct maritime migrant interdiction, we assessed DHS’s maritime migration coordination efforts against leading practices for interagency collaboration we identified in our prior work.[13] Specifically, we reviewed DHS, Joint Task Force-Maritime, and Coast Guard documentation to identify the use of leading collaboration practices in written guidance and agreements.[14] This documentation included operation-specific plans and reports, such as the DHS Operation Vigilant Sentry Base Plan. These documents include information that describes methods and mechanisms for interagency collaboration and information sharing procedures for responding to mass maritime migration in the Caribbean Sea and Florida Straits. The documentation also included national- and field-level policies and procedures—such as local Regional Coordinating Mechanism charters.

Further, to assess the Coast Guard’s and the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force’s collaborative efforts, we interviewed officials from the Coast Guard, CBP, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and Joint Interagency Task Force-South (JIATF-South). We also interviewed Operation Vigilant Sentry task force officials responsible for leading maritime migration coordination efforts. Finally, during our site visits to Miami, Florida, and San Diego, California, we interviewed officials from the Coast Guard, as well as CBP’s Air and Marine Operations and Border Patrol, about their collaboration efforts using the DHS Regional Coordinating Mechanisms. The Regional Coordinating Mechanisms serve as a primary method for interagency collaboration.[15] While the information we obtained from these interviews and site visits is not generalizable, it provided valuable insights into their collaboration practices.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The Coast Guard’s field structure is organized under two area commands, the Atlantic and Pacific Area Commands. These two area commands oversee nine districts across the U.S., which, in turn, collectively oversee 36 sectors.[16] Each Coast Guard area, district, and sector is responsible for managing its assets—aircraft, cutters, and boats—and accomplishing missions within its area of responsibility. The Coast Guard operates a total fleet of about 200 fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft, almost 250 cutters, and more than 1,600 boats.[17]

Drug Interdiction Mission

Coast Guard’s aim for the drug interdiction mission is to stem the flow of illicit drugs into the U.S. According to the Coast Guard, this mission supports national and international strategies to deter and disrupt the market for illegal drugs, dismantle transnational organized crime and drug trafficking organizations, and prevent transnational threats from reaching the U.S.

The Coast Guard is a major contributor of vessels and aircraft deployed to disrupt the flow of illicit drugs, including those smuggled from South America to the U.S. through the Western Hemisphere transit zone—a 6 million square mile area of smuggling routes that includes the eastern Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, as shown in figure 1.

Cocaine interdiction is a U.S. National Drug Control Strategy priority, and according to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, most of the cocaine being smuggled in the maritime environment is by noncommercial maritime vessels through the transit zone. Drug traffickers use go-fast boats, fishing vessels, submersible vessels, noncommercial aircraft, and other types of conveyances to smuggle cocaine from the source zone to Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean en route to the United States.

The Coast Guard primarily conducts its drug interdiction operations in collaboration with JIATF-South, which is under the Department of Defense’s U.S. Southern Command.[18] The Department of Defense is tasked with detecting and monitoring aerial and maritime transit of illegal drugs into the U.S.[19] JIATF-South oversees detection and monitoring operations of drug smuggling specifically in the transit zone. It relies on resources, such as vessels and surveillance aircraft, from the Department of Defense (Navy); DHS components (including the Coast Guard and CBP Air and Marine Operations); and partner nations including Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. According to JIATF-South and Coast Guard officials, JIATF-South uses these assets, in conjunction with available intelligence, to identify the maritime trafficking of illicit drugs far from U.S. shores and close to the source zone countries in South America. It does so to increase the chance that interdictions include larger load sizes and to cause greater disruption to illicit drug smuggling organizations.

Once JIATF-South detects a smuggling event, it passes this information and control of the assets to law enforcement authorities, such as the Coast Guard, to interdict the smuggling vessel, as shown in figure 2. Specifically, Coast Guard Deployable Specialized Forces include Law Enforcement Detachment Teams. These teams consist of specially trained personnel who deploy aboard Navy and allied nation vessels—and sometimes augment existing law enforcement teams on Coast Guard cutters—to conduct maritime law enforcement operations. The teams have the authority to board target vessels and take custody of suspected drug smugglers.[20]

Migrant Interdiction Mission

Coast Guard’s aim for the migrant interdiction mission is to stem the flow of unlawful migration and human smuggling activities via maritime routes. It has three main objectives: (1) deter migrants and transnational smugglers from attempting to enter the U.S. through maritime routes; (2) detect and interdict migrants and smugglers far from the U.S. border; and (3) expand Coast Guard participation in multi-agency and bi-national border security initiatives.[21]

In its Atlantic Area Command, the Coast Guard primarily conducts its migrant interdiction mission within the DHS-led Operation Vigilant Sentry task force, which comprises about 10 federal departments and agencies.[22] This task force provides a coordination mechanism to enhance and unify DHS efforts. It includes various federal, state, and local agencies that each contribute assets and resources to the task force’s operations. DHS uses the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force to coordinate the deployment of joint aircraft, vessels, and personnel to deter mass migration events and respond to other maritime migration incidents in the Caribbean corridor of the U.S.

The task force began surging Coast Guard assets to the Caribbean in August 2022 in response to historically high levels of maritime migration from Cuba and Haiti. As of November 2025, the surge operation was ongoing.

Coast Guard Operational Hours and Estimated Expenses Varied During Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024

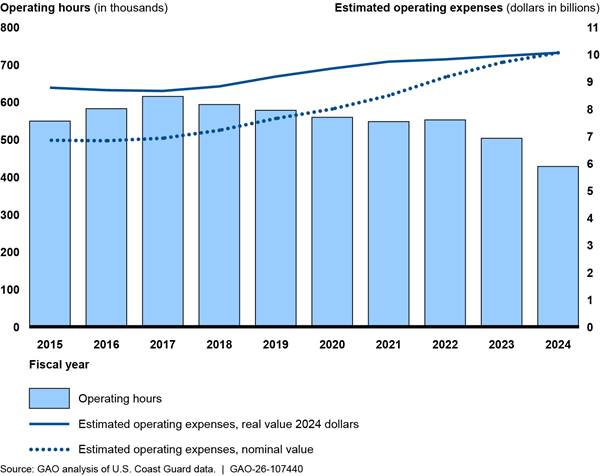

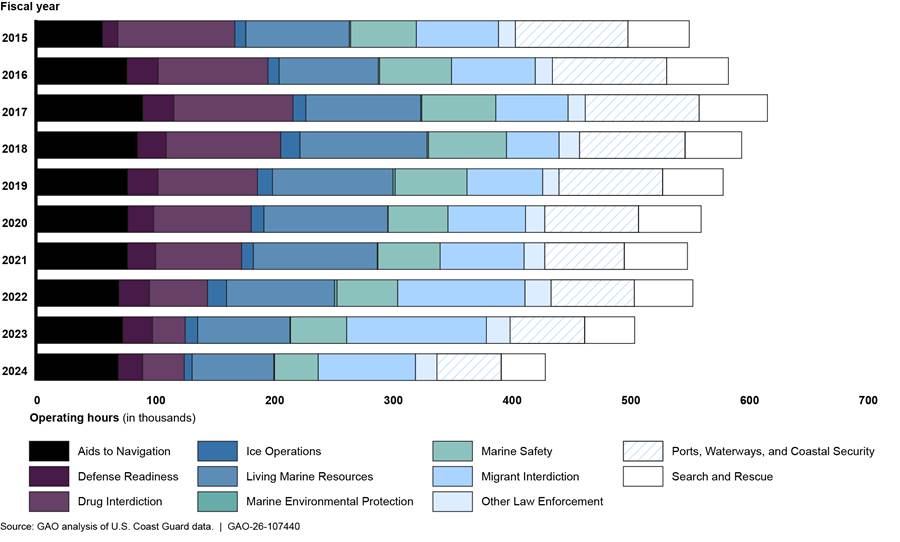

Coast Guard’s use of vessels and aircraft (operational hours) and estimated operating expenses for each of its 11 statutory missions varied from fiscal year 2015 through 2024. Overall, the total number of operational hours generally decreased and the total estimated operating expenses generally increased since fiscal year 2017, as shown in figure 4.[23]

Figure 4: Coast Guard Vessel and Aircraft Operational Hours and Estimated Operating Expenses, Fiscal Years 2015-2024

Note: Coast Guard operational hours include the use of aircraft, cutters, and boats for its 11 statutory missions. See 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). They do not include the time personnel may spend on missions without using vessels or aircraft. We do not include hours expended for support activities or for training. According to the Coast Guard, the service estimates its operating expenses for each mission by (1) multiplying operations and maintenance costs for supporting a vessel or aircraft by the operational hours and (2) using survey data to estimate additional personnel costs for nonvessel or aircraft-based operations.

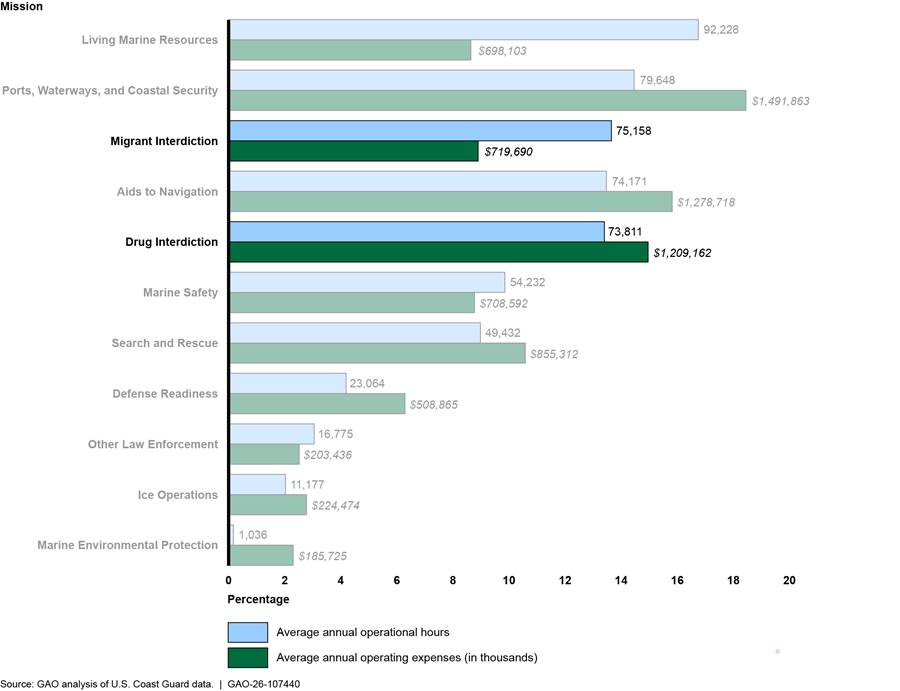

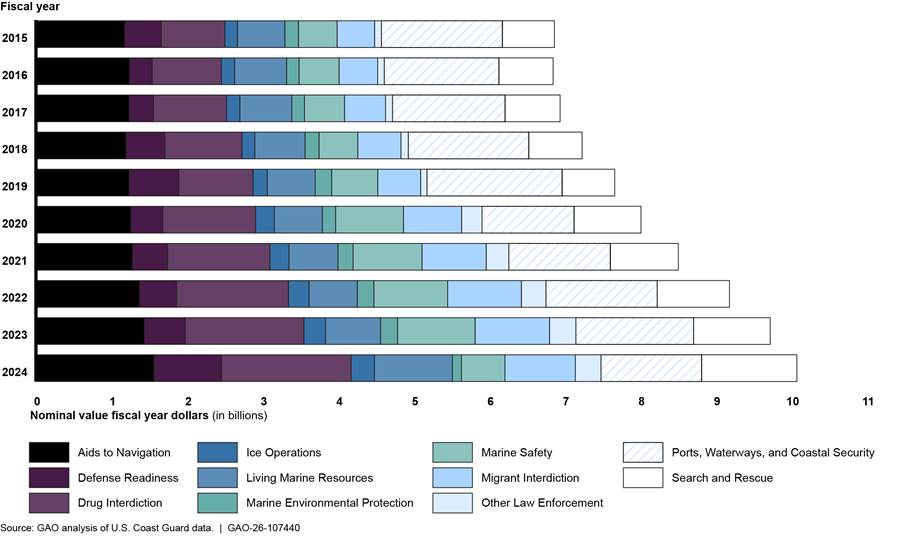

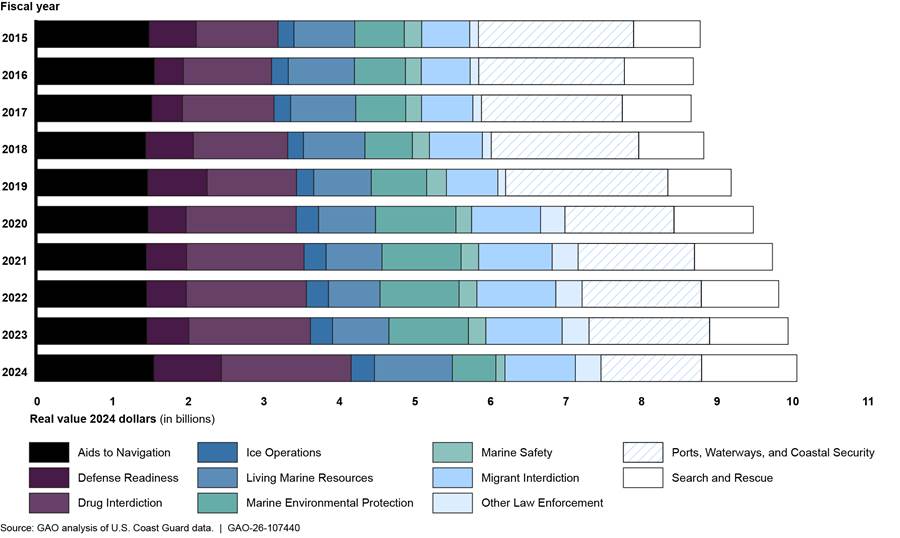

Coast Guard data show that on average, in fiscal years 2015 through 2024, vessel and aircraft operational hours for its drug and migrant interdiction missions accounted for 27 percent of the Coast Guard’s annual operational hours.[24] In addition, 24 percent of the Coast Guard’s total estimated operating expenses for its statutory missions was for drug interdiction (15 percent) and migrant interdiction (9 percent)—averaging more than $1.9 billion combined annually, as shown in figure 5.[25]

Figure 5: Coast Guard Average Annual Vessel and Aircraft Operational Hours and Average Annual Estimated Operating Expenses, by Statutory Mission, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: Coast Guard operational hours include the use of aircraft, cutters, and boats for its 11 statutory missions. See 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). They do not include the time personnel may spend on missions without using vessels or aircraft. We do not include hours expended for support activities or for training. According to the Coast Guard, the service estimates its operating expenses for each mission by (1) multiplying operations and maintenance costs for supporting a vessel or aircraft by the operational hours and (2) using survey data to estimate additional personnel costs for nonvessel or aircraft-based operations.

Coast Guard Generally Did Not Meet its Interdiction Targets and Has Not Implemented Effective Migrant Interdiction Performance Measures

The Coast Guard did not meet the target for its primary drug interdiction performance measure in any of the 10 years from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024, due in part to longstanding asset and personnel challenges. The Coast Guard also did not meet the target for its primary migrant interdiction measure in 6 of 10 years during that same period. Coast Guard officials stated that these performance measures do not effectively assess its drug and migrant interdiction efforts. As a result, the Coast Guard has implemented new drug interdiction measures that officials said effectively measure its efforts in this area. As of July 2025, Coast Guard officials said the service was in the initial stages of developing new migrant interdiction performance measures and that the new measures had not yet been approved by the Coast Guard or DHS.

Coast Guard Did Not Meet Its Primary Drug Interdiction Performance Target for 10 Years

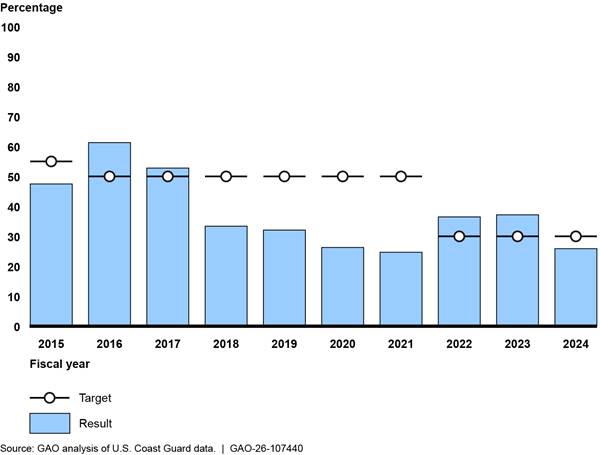

The Coast Guard did not meet the target for its primary drug interdiction mission performance measure—the removal rate for cocaine from noncommercial vessels in the maritime transit zone—during fiscal years 2015 through 2024.[26] According to the Coast Guard, the service lowered the target three times to make it more attainable. However, according to Coast Guard data, the service still did not meet the target, as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6: Coast Guard Cocaine Removal Rate from Noncommercial Vessels in the Maritime Transit Zone, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: The removal rate for cocaine from noncommercial vessels in the maritime transit zone performance measure assesses the percentage of cocaine directly seized or observed being jettisoned, scuttled, or destroyed as a result of Coast Guard actions, relative to the total known flow of cocaine through the transit zone using noncommercial maritime vessels. The Coast Guard and other federal agencies use the Consolidated Counterdrug Database to capture all known and suspected drug movement, allowing them to calculate the total known flow of cocaine. The database is the U.S. government’s authoritative database for illicit drug movement in the Western Hemisphere. During quarterly interagency conferences, database partners develop and reconcile information about the quantity of cocaine seized during drug interdiction operations.

This measure compares the amount of cocaine removed as a result of Coast Guard actions to the total known flow of cocaine through the transit zone.[27] The Coast Guard has another longstanding performance measure for drug interdiction—the metric tons of cocaine removed from noncommercial vessels in the maritime transit zone. According to the Coast Guard, its Office of Maritime Law Enforcement Policy regularly reviews drug interdiction performance and recommends new targets. Officials told us they use historical performance data, anticipated asset availability, and estimated cocaine flow through the transit zone, among other factors, to set targets that Coast Guard considers both attainable and optimistic.[28]

Several longstanding challenges have hindered the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its drug interdiction performance measures and other mission demands. As we have previously reported, these challenges include (1) declining availability of vessels and aircraft, (2) acquisition-associated delays in replacing them, and (3) workforce challenges.[29]

Vessel and Aircraft Availability Challenges

The Coast Guard’s vessels and aircraft have faced availability challenges and have been in a state of decline for decades. For example, in June 2025 we reported that the operational availability of its Medium Endurance Cutters, which Coast Guard relies on for its drug interdiction mission, declined during fiscal years 2020 through 2024.[30] We also reported that the Coast Guard was experiencing increasing cutter maintenance challenges, and that those increasing challenges, such as equipment failure and resulting unplanned maintenance, have led to cutters missing patrol obligations. For example, Coast Guard operational reporting documents stated that unplanned maintenance, among other things, had significantly reduced the capacity of Medium Endurance Cutters to conduct missions for the Atlantic Area Command.

The Coast Guard’s asset readiness challenges are not limited to its cutters. In April 2024, we reported that the Coast Guard’s aircraft generally did not meet the Coast Guard’s 71 percent availability target during fiscal years 2018 through 2022.[31] Coast Guard officials attributed the aircraft fleet generally not meeting availability targets to maintenance and repair challenges.

Acquisition Program Challenges

We also found that the Coast Guard’s declining asset availability is exacerbated by persistent challenges it faces managing its planned $40 billion acquisition programs to modernize its vessels and aircraft. Headquarters officials told us that they would not be able to increase mission activity without acquiring more assets, but acquisition delays have been a longstanding challenge for the service. Furthermore, according to officials, the acquisition process is lengthy, as it can take several years from initial request to final delivery of an asset.

Our prior work has found that these persistent challenges include capability gaps from schedule delays, and affordability concerns and difficult tradeoff decisions. Specifically, delays experienced by the Coast Guard’s highest priority program—the Offshore Patrol Cutters—will exacerbate capability gaps.[32] The Coast Guard testified in July 2024 that Offshore Patrol Cutters—which will replace Medium Endurance Cutters—are to be essential assets for JIATF-South and the service’s drug interdiction mission.[33] However, in May 2024, we reported that the Coast Guard had delayed delivery of the first Offshore Patrol Cutter by 4 years, from fiscal year 2021 to 2025.[34] Given the delays, the Coast Guard has projected a reduction in asset availability—or a reduction in the number of cutters available for operations—through 2039.[35]

Workforce Challenges

Our prior work has also shown that staffing shortfalls and poor workforce planning have affected the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its mission needs, including for drug interdiction. In May 2025, we reported that while the service had exceeded its annual recruitment target in fiscal year 2024, it fell short of its goals for fiscal years 2019 through 2023.[36] Even with the increase in recruiting, we reported in April 2025 that the service remained approximately 2,600 service members, or 8.5 percent of its total enlisted workforce, short of its enlisted workforce target at the end of fiscal year 2024.[37] As a result, the Coast Guard was operating below the workforce level it deemed necessary to meet its operational demands.

Further, in June 2025, we reported that cutter crew and support position vacancy rates increased from fiscal year 2017 through fiscal year 2024, according to Coast Guard data.[38] Multiple Coast Guard officials told us that due to cutter personnel shortages, cutters often deploy without a full crew, leaving the remaining crew to take on the responsibilities of missing staff. We also previously reported on Coast Guard resource shortfalls and incomplete workforce planning for various units the service relies on to support its drug interdiction mission, including its aviation workforce. For example, the Coast Guard had not assessed and determined necessary staffing levels and skills for a large portion of its aviation workforce, including all 25 of its air stations and its major aircraft repair facility.[39]

In addition, according to Coast Guard officials, the maritime migration surge operation the Coast Guard began in fiscal year 2022 significantly exacerbated its inability to meet its drug interdiction mission. This is because it redirected assets from the drug interdiction mission to the migrant interdiction mission. According to Coast Guard officials, the migrant interdiction mission is in part a life-saving mission and, therefore, a higher-priority mission. In addition, Coast Guard officials told us that other factors that affected the service’s ability to meet its primary drug interdiction performance target included prioritizing other statutory mission operations, such as search and rescue, and transnational criminal organizations changing their tactics to evade detection.

According to Coast Guard officials, neither of their longstanding drug interdiction performance measures effectively capture the service’s drug interdiction efforts. Thus, officials told us they had developed and implemented new additional measures that more effectively assess these efforts. In fiscal years 2021 and 2022, the Coast Guard began using four new drug interdiction performance measures.[40] These new measures focus on the Coast Guard’s use of its assets, rather than on the amount of drug removals. According to the Coast Guard, these measures assess how effectively the Coast Guard uses the assets actively conducting drug interdictions and, therefore, reflect information that more accurately measure its efforts.

Coast Guard officials told us in July 2025 that the service has identified its preferred primary measures—with updated targets—for use internally and to report externally. Officials said the service incorporated these changes into its fiscal year 2026–2027 Strategic Planning Direction, which as of July 2025 was pending DHS approval.

Coast Guard Has Not Yet Implemented Performance Measures that Effectively Assess its Migrant Interdiction Efforts

The Coast Guard did not meet the target for its primary migrant interdiction mission performance measure—percent of migrants attempting to enter the U.S. by maritime routes interdicted by the Coast Guard—during 6 of 10 years from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024.[41] The measure compares the number of migrants the service interdicts to total known maritime migrant flow.[42] According to Coast Guard officials, the service lowered the target during that period to make it more attainable. As a result, according to Coast Guard data, it met the target in fiscal years 2016 and 2017 and 2022 and 2023, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Percent of Migrants Attempting to Enter the U.S. by Maritime Routes that the Coast Guard Interdicted, Fiscal Years 2015-2024

Note: The percent of migrants attempting to enter the U.S. by maritime routes interdicted by the Coast Guard performance measure compares the number of migrants the service interdicts to the total known maritime migrant flow. According to DHS, known maritime migrant flow is the number of migrants the U.S. government was able to physically identify or estimate based on visible evidence. It includes migrants who were interdicted at sea or apprehended on land, deterred or disrupted from reaching the U.S., detected but got away, and who were either presumed or confirmed to have lost their lives.

According to Coast Guard officials, the service was unable to consistently meet this target for a variety of reasons. In particular, the Coast Guard uses the same types of assets for both its drug interdiction and migrant interdiction missions. Thus, the factors discussed above related to declining asset availability, acquisition delays, and workforce challenges that affected Coast Guard’s ability to meet its drug interdiction performance targets similarly affected its ability to meet its migrant interdiction performance targets.

While the Coast Guard did not meet the measure in 6 of the last 10 years, it surpassed the target in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, when known maritime migrant flow was markedly higher. According to Coast Guard data, known maritime migration levels increased from an annual average of over 8,200 migrants from fiscal year 2015 through 2021 to approximately 34,000 migrants each year in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 (a 311 percent increase). To address this increase, the Coast Guard shifted resources, particularly its vessels and aircraft, from other statutory missions to conduct migrant interdiction. With these additional assets, according to Coast Guard data, the service was able to interdict about 37 percent of migrants in both fiscal years 2022 and 2023—the highest percentage since fiscal year 2017, when known maritime migrant flow was significantly lower.

Despite increasing its migrant interdiction deployments, the Coast Guard did not meet its migrant interdiction performance target in fiscal year 2024. According to Coast Guard’s fiscal year 2024 performance report, one factor that affected its performance was an increase in partner nation and other federal government agency efforts to interdict migrants.[43] As a result, there was a decrease in the percentage of migrants the Coast Guard interdicted itself. According to Coast Guard asset operational hour data, the service spent less time conducting the migrant interdiction mission in fiscal year 2024 than in each of the previous 2 years.[44]

While acknowledging factors affecting its operations, Coast Guard headquarters officials told us that their Coast Guard-only interdiction measure is not effective for assessing its migrant interdiction mission performance. They said this was because factors outside of the Coast Guard’s control impact its ability to meet the target. For example, Coast Guard officials said that when the Coast Guard detects but is unable to interdict a migrant vessel and requests assistance from another agency—such as CBP Air and Marine Operations—it “counts against” the Coast Guard. In this scenario, the number of known migrants increases, but the Coast Guard’s interdiction percentage does not increase because CBP receives credit for the interdiction. Therefore, the Coast Guard does not make progress towards meeting its performance measure, despite Coast Guard action that ultimately results in a successful interdiction.

Coast Guard officials agreed that there would be benefits to establishing new migrant interdiction performance measures but had not previously done so. In July 2025, Coast Guard officials told us that its Office of Maritime Law Enforcement Policy was in the initial stages of developing new migrant interdiction performance measures that are intended to more effectively assess its mission performance. Officials also said these new measures were in the first stages of internal Coast Guard review, after which the service will submit the measures to DHS for approval.

Our prior work has found that performance measures should provide managers and other stakeholders timely, action-oriented information in a format that helps them make decisions that improve program performance.[45] Moreover, Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control states that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives and that while performance measures need not be perfect, they must be sufficient for their intended use.[46]

By implementing migrant interdiction mission performance measures that effectively measure its efforts, the Coast Guard would have better assurance that it is providing both Coast Guard and DHS decision makers with relevant information to assess its performance and make future resource decisions.

Coast Guard Focus on Migrant Interdiction Since August 2022 Impacted its Operations for Other Missions

Coast Guard Redirected Resources from Other Missions to Address Maritime Migration

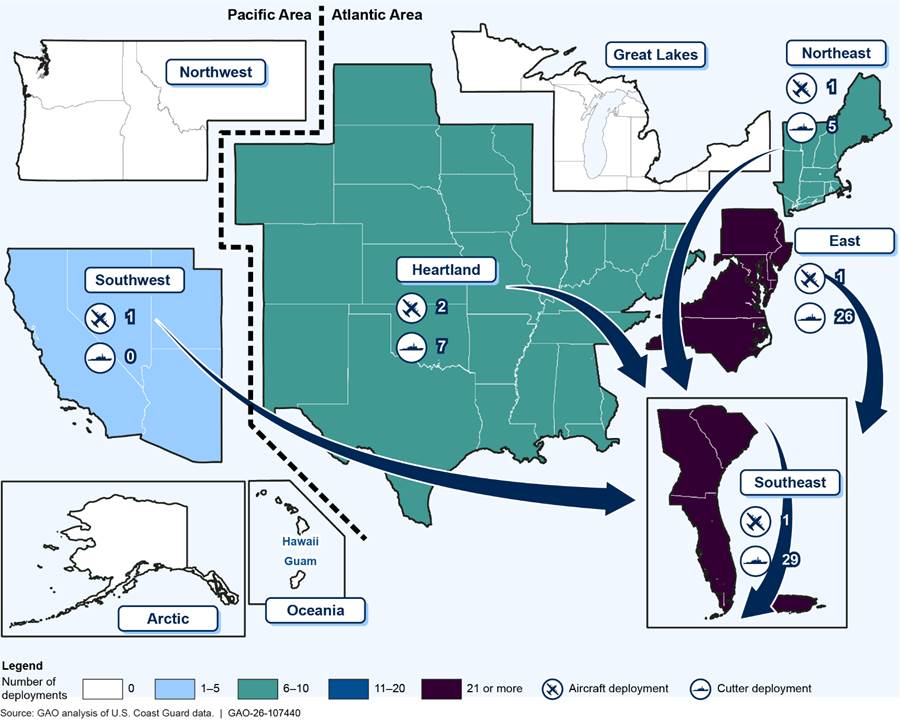

The Coast Guard redirected aircraft and vessels from its other statutory missions to address high maritime migration levels. According to Coast Guard data, from August 2022 through September 2024, the service deployed 80 cutters to conduct Operation Vigilant Sentry operations in its Southeast District.[47] Of those, 13 were regularly scheduled for migrant interdiction, 38 were re-directed from other missions, and 29 were a mix of both. The Coast Guard redirected cutters from its Northeast, East, and Heartland Districts; its Atlantic Area Command; and seven different sectors in the eastern U.S. to its Southeast District.[48] It also redirected cutters within its Southeast district. In addition, it sent aircraft from its Northeast and Heartland Districts, and both Atlantic and Pacific Area commands, to its Southeast District.[49] Although Coast Guard redirected cutters and aircraft from across the country, it redirected most of these assets from locations within its East District or Southeast District, as shown in figure 8.

Figure 8: Coast Guard Redirected Cutter and Aircraft Deployments for Maritime Migrant Interdiction in the Southeast District, Fiscal Years 2022–2024

Note: The numbers in the legend represent the number of cutter and aircraft deployments redirected from each district to the migrant interdiction mission in the Southeast District since August 2022, based on the asset’s homeport or home air station location. For example, Coast Guard redirected 7 cutters and 2 aircraft from homeports or home air stations located in its Heartland District to conduct migrant interdiction under Operation Vigilant Sentry in its Southeast District. In addition, the Coast Guard redirected cutters already located in its Southeast District to conduct migrant interdiction.

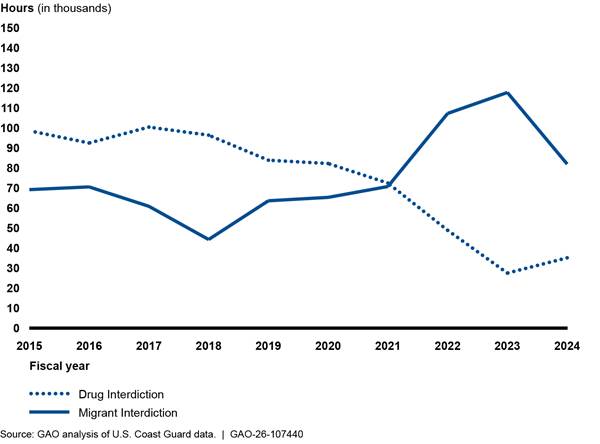

According to Coast Guard officials, the drug interdiction mission sustained the most significant impacts from redirecting many of its resources to migrant interdiction. As shown in figure 9, during fiscal years 2021 through 2023, the Coast Guard increased its operational hours for aircraft and vessels by 66 percent for the migrant interdiction mission, while decreasing its hours for drug interdiction by 62 percent. Since fiscal year 2022, migrant interdiction operational hours have surpassed drug interdiction, flipping the trend in fiscal years 2015 through 2021.

Figure 9: Coast Guard Drug and Migrant Interdiction Vessel and Aircraft Operational Hours, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: Coast Guard operational hours include the use of aircraft, cutters, and boats for its 11 statutory missions. See 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). They do not include the time personnel may spend on missions without using vessels or aircraft. We do not include hours expended for support activities or for training.

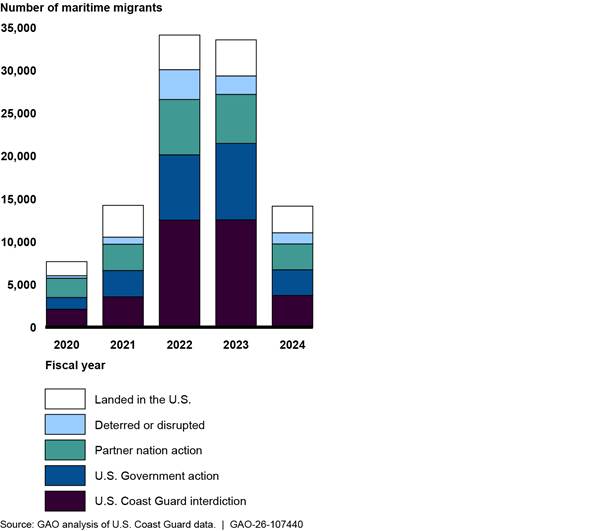

By redirecting assets and surging them to Operation Vigilant Sentry, the Coast Guard interdicted a higher number of migrants. According to Coast Guard data, the service interdicted approximately 12,500 of 34,000 migrants, or about 37 percent of known maritime migrant flow, in each of fiscal years 2022 and 2023. This was six times the number of interdictions in fiscal year 2020. The migrants whom the Coast Guard did not interdict were interdicted or apprehended by other federal agencies (such as CBP Air and Marine Operations), interdicted or apprehended by international partners, or landed in the U.S., among other outcomes, as shown in figure 10.[50]

Note: According to Coast Guard documentation, an interdiction occurs at sea, while an apprehension occurs on land. Partner nation action and U.S. government action include both interdictions and apprehensions. The U.S. government category includes actions taken by agencies such as CBP’s Air and Marine Operations. It also includes Coast Guard apprehensions but does not include Coast Guard interdictions. The deterred or disrupted category tracks migrants that turn back to their starting point and did not attempt to reach the U.S. The landed category counts those migrants who successfully reached and landed in the U.S. Two other categories not shown are for migrants who lost their lives or who were presumed to have lost their lives. From fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024 approximately 20 to 160 migrants were either presumed or confirmed to have lost their lives annually.

According to Coast Guard data, known maritime migrant flow decreased from fiscal year 2023 (about 34,000 migrants) to fiscal year 2024 (about 14,000 migrants), which DHS officials partly attributed to changes in U.S. immigration policies.[51] According to Coast Guard and Operation Vigilant Sentry task force officials and Coast Guard documentation, U.S. immigration policy and perceptions of U.S. immigration policy have affected maritime migration flows.[52]

Coast Guard Resource Tradeoffs Reduced its Ability to Conduct Drug Interdiction and Other Missions

The Coast Guard’s redirection of resources to the migrant interdiction mission led the service to make tradeoffs that reduced its ability to conduct several of its statutory missions—including drug interdiction, aids to navigation, and living marine resources—and affected its personnel.[53]

Drug Interdiction

The Coast Guard’s redirection of assets exacerbated longstanding challenges and reduced the ability of the service to meet JIATF-South drug interdiction mission demands. Both the number of seizures and amount of drugs the Coast Guard seized annually decreased considerably during the migrant surge, after varying over time. For example, in fiscal year 2021, the Coast Guard made 218 drug seizures, while in fiscal year 2023, during the height of known maritime migrant flow, it conducted almost half as many, or 112 seizures.[54]

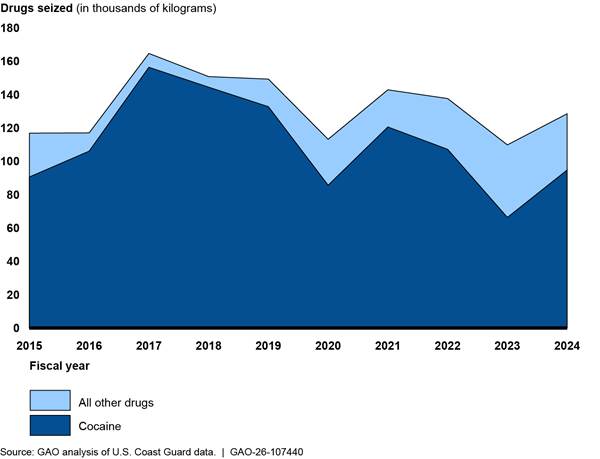

While the Coast Guard’s primary performance measure focuses on cocaine, which is the majority of what is seized in the maritime environment, the service collects data on all drugs it interdicts.[55] As shown in figure 11, the amount of drugs it seized dropped from fiscal year 2021 to fiscal year 2023, from approximately 143,000 kilograms (143 metric tons) to approximately 110,000 kilograms (110 metric tons)—the fewest going back to fiscal year 2015. That amount rebounded in fiscal year 2024 to 128,000 kilograms (128 metric tons).

Note: According to the Coast Guard, drug seizure data reflect only those drugs that are physically seized and brought onboard a Coast Guard cutter. Coast Guard’s longstanding performance measures track removals, a category that also includes drugs that are observed being jettisoned, scuttled, or destroyed as a result of Coast Guard actions but are never recovered. Most of the non-cocaine drug seizures were marijuana. The Coast Guard also seized heroin, methamphetamines, and small amounts of fentanyl, among other drugs.

The Coast Guard is the lead federal agency for maritime drug interdiction in the transit zone and its operations with JIATF-South are a key element of the Coast Guard’s counterdrug efforts. However, partly due to its redirection of resources away from the drug interdiction mission, the service was unable to meet its asset commitments to JIATF-South. For example:

· According to JIATF-South data, the Coast Guard provided half of JIATF-South requested cutter support in fiscal year 2023. In comparison, in fiscal year 2021, before the maritime migration surge operation began, the Coast Guard had provided 96 percent of requested cutter support to the task force.

· According to a Coast Guard performance report, the Atlantic Area provided 45 percent (315 of 700 hours) of its planned C-130 marine patrol aircraft deployments to JIATF-South in fiscal year 2023, despite lowering the target by 40 percent from the year before, fiscal year 2022.

According to JIATF-South officials, partner nations, such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, partially filled the gap left by the Coast Guard reducing its contributions to JIATF-South. For example, JIATF-South officials told us that partner nations contributed more vessels for Coast Guard Law Enforcement Detachment Team deployments. According to JIATF-South data, in fiscal year 2021 partner nations accounted for 54 percent of drug interdictions. In fiscal year 2023, it was 67 percent.

Living Marine Resources and Other Missions

The Coast Guard living marine resources statutory mission was also considerably impacted by the redirection of assets to migrant interdiction.[56] According to the Coast Guard, this mission focuses on the conservation and management of marine life and their environment.[57] In fiscal year 2023, the Coast Guard redirected all planned major cutter living marine resources patrols, which include the boarding of commercial fishing vessels to ensure compliance with relevant laws and regulations, in its Northeast, East, and Heartland Districts to migrant interdiction.[58]

According to the Coast Guard, the service did this to ensure that days lost to Medium Endurance Cutter maintenance issues did not prevent required migrant interdiction deployments. As a result of the asset redirection, during fiscal years 2021 through 2024 the Coast Guard decreased its asset operational hours for its living marine resources mission by 34 percent. Furthermore, Coast Guard did not meet three of its four performance measures for the mission from fiscal year 2022 through 2024.

The Coast Guard’s reduction in operational hours for living marine resources affected efforts in its other missions. According to a Coast Guard fiscal year 2024 performance report, this reduction led to a drop in proficiency for vessel boarding teams. Furthermore, because the living marine resources mission provides readiness for other statutory missions—such as its other law enforcement mission and search and rescue—those missions were affected as well.[59] According to East District officials, its deployment of Fast Response Cutters for migrant interdiction forced the district to scale back living marine resources mission activities—its main mission—due to more limited cutter availability. Those officials also told us the cutter deployments may have affected the district’s ability to effectively do search and rescue in its area of responsibility.

According to Coast Guard officials, the aids to navigation statutory mission was also affected, but to a lesser extent.[60] According to the Coast Guard, this mission focuses on maintaining safe and navigable waterways by providing buoys, lights, and other aids to coordinate the movement of vessels.[61] Between August 2022 and September 2024, the service redirected buoy tenders from four districts, according to Coast Guard data. Officials told us these cutters served as holding platforms for large numbers of interdicted migrants.[62] As a result, those buoy tenders were unavailable to service navigation aids in their home districts. According to a Coast Guard report from fiscal year 2023, balancing scheduled maintenance, Operation Vigilant Sentry deployments, and the priority of meeting standards for navigational aid availability and maintenance was a consistent challenge throughout the year.

Personnel

The maritime migration surge operation impacted the well-being of Coast Guard crews, amplified staffing shortages, and affected training schedules, according to Coast Guard officials. Specifically, according to the Coast Guard, by the end of fiscal year 2024, the service had deployed more than 2,800 personnel to support Operation Vigilant Sentry. Of those, about 1,900 were active duty and the rest were reserve staff. Almost 800 were medical personnel.

According to Coast Guard officials, cutter crews worked harder for longer hours under increased stress due to the life-saving nature of the migrant interdiction mission. According to Southwest District officials, when personnel deployed for Operation Vigilant Sentry returned to the district, they required time off to rest before they could resume their normal work. In response to the strain on cutter crews, Coast Guard officials told us the service created Resiliency Support Teams and increased chaplain services on cutters doing migrant interdiction to help address or prevent crew member mental distress.[63]

Coast Guard documentation noted that its East District personnel deployments to Operation Vigilant Sentry amplified base staffing and qualification shortfalls, and that there was a drop in underway hours dedicated to boat crew training. In addition, according to East District officials, the Coast Guard had to give crews on reallocated cutters time for non-compliant vessel tactic training, which reduced the cutter’s underway hours. Furthermore, according to Coast Guard officials, while cutters held migrants onboard, the crews were unable to do some of their normal responsibilities, including completing required training.

Cutter crews were not the only personnel affected. Officials at a Southeast District air station told us that the air station was conducting daily patrol flights, which were significantly longer than those it conducted before the surge operation. Officials also told us that meeting the migrant interdiction mission and maintaining readiness to conduct other statutory missions, such as search and rescue, strained the air station work force, including those maintaining the aircraft for frequent migrant interdiction patrol flights. In addition, according to air station officials, flight crews reduced training and proficiency flights to conduct migration interdiction patrol flights.

DHS Task Force Facilitates Maritime Migration Coordination but Lacks a Process to Address Lessons Learned and Share Information

The DHS Operation Vigilant Sentry task force provides a key coordination mechanism for Coast Guard and its federal partners involved in conducting maritime migrant interdiction. In prior work, we identified eight leading practices that have been shown to enhance and sustain federal agency coordination.[64] Through this task force, Coast Guard and its federal partners generally followed seven of the eight leading collaboration practices and partially followed the remaining practice. Table 1 shows our assessment of the Coast Guard and Operation Vigilant Sentry task force coordination of migrant interdiction efforts compared against the eight practices.

Table 1: Coast Guard and Operation Vigilant Sentry Task Force Migrant Interdiction Coordination Efforts Compared Against Leading Practices for Interagency Collaboration

|

Leading Collaboration Practices & Examples of Key Considerations |

Examples of Collaboration Efforts |

The Extent Efforts Followed Leading Practices |

|

Define Common Outcomes · Have the short- and long-term outcomes been clearly defined? |

Coast Guard and the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force operated with clearly defined short- and long-term goals and outcomes for migrant interdictions.a For example, the Operation Vigilant Sentry Base Plan—the task force’s standing migrant interdiction operation—states that the efficient processing and removal of interdicted migrants from cutters and ships is essential to operational success.b As such, the task force assessed key variables—migrant flow, capacity aboard cutters, and repatriation status—on a weekly basis to ensure its ability to sustain surge operations in the short term. In addition, DHS developed an agency-wide annual performance measure to assess migrant interdiction effectiveness for all DHS agencies involved in migrant interdiction.c This joint measure, separate from Coast Guard’s measure of its own efforts, demonstrates that Coast Guard and its federal partners have clearly defined long-term collective outcomes. |

● |

|

Ensure Accountability · What are the ways to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward the short- and long-term outcomes? |

Coast Guard and the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force established ways to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward short- and long-term outcomes. For example, the task force developed Maritime Migration Leadership Briefs to assess Operation Vigilant Sentry’s interdiction outcomes, which tracked several key variables, including migrant flow, capacity aboard cutters, and repatriation status.d It then used these briefs to communicate with DHS and Joint Task Force-Maritime’s leadership on a weekly basis about its progress toward the short-term outcome of efficiently repatriating interdicted migrants to ensure its continued ability to sustain the surge operation. Coast Guard also monitored and communicated progress toward long-term outcomes, such as its contribution to the joint DHS performance measure on migrant interdiction effectiveness in its Annual Performance Reports.c |

● |

|

Bridge Organizational Culture · Have participating agencies established compatible policies, procedures, and other means to operate across agency boundaries? |

Key DHS guidance documents, such as the Maritime Migration Contingency Plan and the Maritime Operations Coordination Plan, establish compatible means for how Coast Guard and its partner agencies are to operate together.e,f For example, these documents set forth methods for how U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Coast Guard communicate and coordinate to identify and apprehend migrants during joint operations. CBP officials we interviewed explained that CBP typically identified and interdicted migrant vessels, then transferred interdicted migrants to a Coast Guard cutter for processing and repatriation. |

● |

|

Identify and Sustain Leadership · Has a lead agency or individual been identified? · How will leadership be sustained over the long term? |

Coast Guard is the executive agent, or lead responsible component, of the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force, Joint Task Force-Maritime, and multiple Regional Coordinating Mechanisms. The Commander of the Southeast Coast Guard District also serves as the Director of the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force, which provides long-term leadership continuity. |

● |

|

Clarify Roles and Responsibilities · Have the roles and responsibilities of the participants been clarified? |

Key guidance documents, such as the Operation Vigilant Sentry Base Plan and the DHS Maritime Migration Contingency Plan, have clearly defined roles and responsibilities for all agencies that conduct migrant interdiction operations.b,e For example, the DHS Maritime Migration Contingency Plan describes CBP’s role to conduct air and maritime surveillance and coordinate interdiction operations with the Coast Guard.e CBP officials we met with also told us that it had primary responsibility for conducting air surveillance. |

● |

|

Include Relevant Participants · Have all relevant participants been included? · Do the participants have the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to contribute? |

The Operation Vigilant Sentry task force consists of federal, state, and local agencies that have the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to conduct maritime migrant interdiction operations. These include Coast Guard, CBP, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Secret Service, and Transportation Security Administration, among others. |

● |

|

Develop and Update Written Guidance and Agreements · If appropriate, have agreements regarding the collaboration been documented? |

Coast Guard and the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force have developed written guidance for conducting joint interdiction operations, such as the DHS Operation Vigilant Sentry Base Plan and the Maritime Operations Coordination Plan.b,f Coast Guard has also established multiple charter agreements by region with relevant federal partners under the Regional Coordinating Mechanisms. These documents describe how partner agencies, including CBP, ICE, and USCIS are to collaborate during interdiction operations. For example, they describe how CBP and Coast Guard are to collaborate with USCIS for screening and processing of interdicted migrants. |

● |

|

Leverage Resources and Information · How will the collaboration be resourced through staffing? · How will the collaboration be resourced through funding? If interagency funding is needed, is it permitted? · Are methods, tools, or technologies to share relevant data and information being used? |

Coast Guard and the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force efforts partially followed this practice. The agencies that comprise the Regional Coordinating Mechanisms each provided staff, equipment, vehicles, aircraft, or vessels and any associated funding to support joint operations. However, the task force did not fully leverage methods, tools, and technologies to share relevant information among the partner agencies. For example, the task force relied on Coast Guard’s process for developing after action reports, and the Coast Guard does not have a formal process to share its after action reports with relevant partners, which include lessons learned. |

◐ |

● = Generally followed ◐ = Partially followed ○ = Not followed

Source: GAO analysis of Coast Guard information. | GAO‑26‑107440

Note: “Generally followed” means evidence showed that Coast Guard or the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force took steps that generally aligned with the applicable considerations within a practice; “Partially followed” means evidence showed that Coast Guard or the task force took steps that aligned with some of the applicable considerations within a practice, but not all; and “Not followed” means evidence showed that Coast Guard or the task force did not take any steps that aligned with the applicable considerations within a practice.

aThe Operation Vigilant Sentry task force was formerly known as the Homeland Security Task Force-Southeast. In May 2025, DHS changed this task force name to eliminate potential confusion with the establishment of new Homeland Security Task Forces in all 50 states, pursuant to Executive Order 14159, “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” See Exec. Order No. 14,159, § 6, 90 Fed. Reg. 8,443 (Jan. 20, 2025). The Operation Vigilant Sentry task force reports to Joint Task Force-Maritime, which provides oversight, coordination and support. Joint Task Force-Maritime was formerly known as Joint Task Force-East. DHS officials told us they changed this task force name to clarify the task force mission and scope, which covers all U.S. maritime borders and will support the Homeland Security Task Forces operating in all 50 states, not solely those in the East.

bHomeland Security Task Force-Southeast, DHS Operations Plan Vigilant Sentry, (Miami, FL: Jun. 7, 2019).

cU.S. Department of Homeland Security, Annual Performance Report Fiscal Year 2023-2025, (Springfield, VA: Mar. 11, 2024).

dJoint Task Force – East, JTF-E OVS Risk Assessment Model, (Portsmouth, VA: Mar. 1, 2024).

eU.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS Southern Border and Approaches Maritime Migration Contingency Plan, (Aug. 16, 2016).

fU.S. Department of Homeland Security, Maritime Operations Coordination Plan, (Oct. 20, 2022).

While Coast Guard and its federal partners generally followed seven of the eight leading collaboration practices, they partially followed the eighth practice—leveraging resources and information. The Operation Vigilant Sentry task force leveraged resources across partner agencies to facilitate coordination of migrant interdictions. Specifically, the task force agencies each provided staff, equipment, vehicles, aircraft, or vessels, and any associated funding to support joint migrant interdiction operations. However, the task force did not fully leverage methods, tools, and technologies to share relevant information among the partner agencies. Rather, it relied on Coast Guard’s established process for identifying lessons learned and Coast Guard does not have a formal process to share this information with its federal partners.

Specifically, the Coast Guard has after action and corrective action programs in place to identify and address lessons learned from real-world events and exercises to help improve future operations.[65] As the executive agent, or lead responsible component of the task force, the Coast Guard used these programs to develop an after action report that identified key lessons learned following the first full year of the Operation Vigilant Sentry maritime migration surge operation. Coast Guard identified lessons learned applicable to itself and partner agencies in the task force and made some accompanying recommendations.

However, Coast Guard officials told us that because it does not have the authority to direct other agencies to complete recommended corrective actions, it documented some recommendations as information-only and was not tracking their implementation. Moreover, the Coast Guard does not have a formal process to share its after action reports with federal partners, but it allows the reporting unit discretion to determine whether to share the report with certain partners as it deems relevant. For example, Coast Guard officials told us they had shared its after action report with partner agencies. However, officials could not provide documentation that they did so, and a key DHS partner agency told us it had not received a copy.

In addition, because the Coast Guard leads this effort, other partner agencies have limited involvement in developing recommendations and tracking their completion, according to Coast Guard officials. For example, partner agencies do not have access to the Coast Guard system used to track the implementation of corrective actions. Coast Guard officials told us the existing process benefits the Coast Guard but has limited utility for its partner agencies.

The Operation Vigilant Sentry task force would be better positioned than the Coast Guard to share relevant information and follow up on lessons learned across multiple DHS components. However, the task force has not developed a corrective action system or process to identify and address lessons learned from Operation Vigilant Sentry for all task force federal agencies. DHS task force officials said that because the task force is minimally staffed, it does not have a permanent position to dedicate to planning activities or collecting lessons learned.

Task force officials told us that in July 2025, in response to our inquiry, they placed the report on the Homeland Security Information Network—a shared DHS information system available to all DHS partner agencies. However, the task force does not have a formal process to consistently share after action reports with relevant federal partners. As a result, other federal agencies may operate with different or limited information, which can lead to a fragmented federal approach to migrant interdiction operations.

According to our prior work on addressing fragmentation, overlap, and duplication, fragmentation occurs when more than one agency (or more than one organization within an agency) is involved in the same broad area of national interest and opportunities exist to improve customer service. Agencies may be able to achieve greater efficiency and effectiveness by reducing or better managing such fragmentation.[66] Leading collaboration practices we identified state that when collaborating entities work to leverage resources and information, such as by sharing relevant data and information, they can successfully address crosscutting challenges or opportunities. While resources can sometimes be limited, collaborating agencies should look for opportunities to address needs by assessing the resources and capacities that each agency can contribute to the collaborative effort.[67]

By implementing a process to identify and address lessons learned from real-world events and exercises, the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force would have better assurance that identified areas for improvement are addressed by all relevant federal partner agencies. Moreover, by sharing after action reports on its real-world events and exercises with its federal partners, the task force would better leverage methods to share relevant information with its federal partner agencies and could better manage fragmentation. This would ensure that all federal partner agencies have input into the process and operate with similar information to support a whole of government approach to migrant interdiction.

Conclusions

Although Coast Guard generally intends surge operations to be short in duration, it has sustained the ongoing maritime migration surge operation for over 3 years. To meet this demand, the Coast Guard made resource tradeoffs and redirected vessels, aircraft, and personnel. The maritime migration surge operation exacerbated Coast Guard’s longstanding asset and personnel challenges.

The Coast Guard does not have migrant interdiction performance measures that effectively assess its migrant interdiction efforts. As of July 2025, the service was in the initial stages of developing new measures. However, Coast Guard had not yet approved the new measures or sent them to DHS for approval. By implementing performance measures that effectively measure its efforts, the Coast Guard would have better assurance that it is providing both Coast Guard and DHS decision makers with relevant information to assess its performance and make future resource decisions.

The Coast Guard and DHS’s Operation Vigilant Sentry task force have generally coordinated their maritime migration interdiction activities, consistent with leading collaboration practices. However, the task force relied on Coast Guard’s established process for identifying lessons learned and sharing information with its federal partners. According to the Coast Guard, it does not have the authority to direct other agencies to complete recommended corrective actions; nor does it have a formal mechanism to share its after action reports with federal partners. Thus, those partners may operate with different or limited information, which can lead to a fragmented federal approach to migrant interdiction.

The Operation Vigilant Sentry task force would be better positioned than Coast Guard to share relevant information and follow up on lessons learned across multiple DHS components. By implementing a process to identify and address lessons learned following real-world events and exercises, and sharing those reports with its federal partners, the task force could ensure that all DHS components improve information sharing and better manage fragmentation among its federal partners.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DHS:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Commandant of the Coast Guard implements performance measures for the migrant interdiction mission that effectively measure the service’s efforts. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force implements a process to identify and address lessons learned following real-world events and exercises with all relevant federal partner agencies, and shares relevant information with those partners. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and the Coast Guard for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix IV, DHS concurred with both recommendations and described the Coast Guard’s planned actions to address them. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Specifically, in response to recommendation 1, DHS stated that when proposed changes are approved, the Coast Guard will implement performance measures that effectively measure and report on its efforts.

In response to recommendation 2, DHS stated that the Coast Guard will work with the Operation Vigilant Sentry task force to consider how best to establish a process that identifies and addresses lessons learned following real-world events and exercises with relevant federal partner agencies, and to share information with those partners, as appropriate.

The actions described, if fully implemented, would address our recommendations.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional Committees, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is also available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at MacLeodH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last pageof this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Heather MacLeod

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Coast Guard has organized its 11 statutory missions under six different mission programs, including Maritime Law Enforcement, as shown in table 2.[68] According to the Coast Guard, missions under its Maritime Law Enforcement program protect the U.S.’s maritime borders from encroachment; defend the Nation’s maritime sovereignty from illicit activity; facilitate legitimate use of the waterways; and suppress violations of federal law on, under, and over the high seas and waters subject to U.S. jurisdiction.

|

Mission program |

Statutory mission |

Select mission activities |

|

Maritime security operations |

Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security (response activities) |

Protect people and property in the marine transportation system by preventing, disrupting, and responding to terrorist attacks, sabotage, espionage, or subversive acts |

|

Maritime law enforcement |

Migrant Interdiction |

Enforce U.S. immigration laws and international conventions against human smuggling through at-sea interdiction and rapid repatriation of maritime migrants |

|

|

Drug Interdiction |

Disrupt the maritime flow of illegal drugs through at-sea interdiction and seizure of smuggling vessels carrying contraband |

|

|

Living Marine Resources |

Enforce laws and regulations in the inland, coastal, and offshore areas to support conservation and management of living marine resources and their environments; and enforce compliance with international agreements to deter illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing activity |

|

|

Other Law Enforcement |

Protect U.S. natural resources in the maritime domain, such as fish stocks, against illegal incursions by foreign fishing vessels |

|

Maritime prevention |

Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security (prevention activities) |

Protect people and property in the marine transportation system by preventing, disrupting, and responding to terrorist attacks, sabotage, espionage, or subversive acts |

|

|

Marine Safety |

Promote safety at sea and the prevention of maritime accidents through regulations, inspections, and investigations |

|

|

Marine Environmental Protection (prevention activities) |

Reduce the risk of harm to the maritime environment by developing and enforcing regulations to prevent oil and hazardous substance spills in the marine environment, prevent the introduction of invasive species into the maritime environment, and prevent unauthorized ocean dumping |

|

Maritime response |

Search and Rescue |

Search for, and provide aid to, those who are in distress to minimize the loss of life, injury, and property damage or loss at sea |

|

|

Marine Environmental Protection (response activities) |

Reduce the harm to the maritime environment by responding to oil and hazardous substance spills |

|

Defense operations |

Defense Readiness |

Ensure Coast Guard assets are capable and equipped to deploy and conduct joint operations in support of the policies and objectives of the U.S. government |

|

Marine transportation system management |

Aids to Navigation |

Maintain a safe and efficient navigable waterways system by providing more than 50,000 buoys, beacons, lights, and other aids to coordinate the safe movement of vessels, support domestic commerce, and facilitate international trade |

|

|

Ice Operations |

Facilitate commercial navigation and commerce in the inland and coastal areas of the U.S., prevent flooding caused by ice, enable search and rescue in icebound areas, and provide access to ice-covered and ice-diminished waters in the polar regions |

Source: GAO presentation of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO‑26‑107440

Appendix II: Trends in the Coast Guard’s Operational Hours and Estimated Expenses by Statutory Mission

Vessel and aircraft operational hours and estimated operating expenses for each of Coast Guard’s 11 statutory missions varied from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024.[69] The total number of operational hours has generally decreased since fiscal year 2017, as shown in figure 14.

Figure 14: Coast Guard Vessel and Aircraft Operational Hours, by Statutory Mission, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: The Coast Guard has 11 statutory missions. 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). Coast Guard operational hours include the use of aircraft, cutters, and boats for its 11 statutory missions. They do not include the time personnel may spend on missions without using vessels or aircraft. We do not include hours expended for support activities or for training.

The nominal, or then-year, value of Coast Guard’s estimated operating expenses for its 11 statutory missions increased from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2024, as shown in figure 15.

Figure 15: Estimated Operating Expenses for the Coast Guard’s 11 Statutory Missions, Nominal, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: The Coast Guard has 11 statutory missions. 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). According to the Coast Guard, the service estimates its operating expenses for each mission by (1) multiplying operations and maintenance costs for supporting a vessel or aircraft by the operational hours and (2) using survey data to estimate additional personnel costs for nonvessel or aircraft-based operations.

The real value, adjusted for inflation in 2024 dollars, of the Coast Guard’s estimated operating expenses remained relatively the same from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2017 and then increased each subsequent year from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2024, as shown in figure 16.

Figure 16: Estimated Operating Expenses for the Coast Guard’s 11 Statutory Missions, Adjusted for Inflation, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: The Coast Guard has 11 statutory missions. 6 U.S.C. § 468(a). According to the Coast Guard, the service estimates its operating expenses for each mission by (1) multiplying operations and maintenance costs for supporting a vessel or aircraft by the operational hours and (2) using survey data to estimate additional personnel costs for nonvessel or aircraft-based operations. Real values are values adjusted for inflation and presented in 2024 dollars using the U.S. Gross Domestic Product Price Index from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

For each of its 11 statutory missions the Coast Guard uses performance measures to assess and communicate agency performance.[70] According to Coast Guard documentation, to measure mission performance the service uses three types of measures:

· Strategic: Goals used to communicate achievement of missions and are publicly reported in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Annual Performance Report.

· Management: Goals used to gauge program results and tie to resource requests that are reported to Congress and publicly available through the DHS Congressional Budget Justification, along with the strategic goals.

· Operational: Additional DHS component measures not reported by DHS but used internally by components to inform management of operations and activities.

Drug Interdiction Mission