FEDERAL AWARDS

Selected Programs Did Not Fully Include Identified Practices to Enhance Oversight and Fraud Prevention

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: M. Hannah Padilla at padillah@gao.gov..

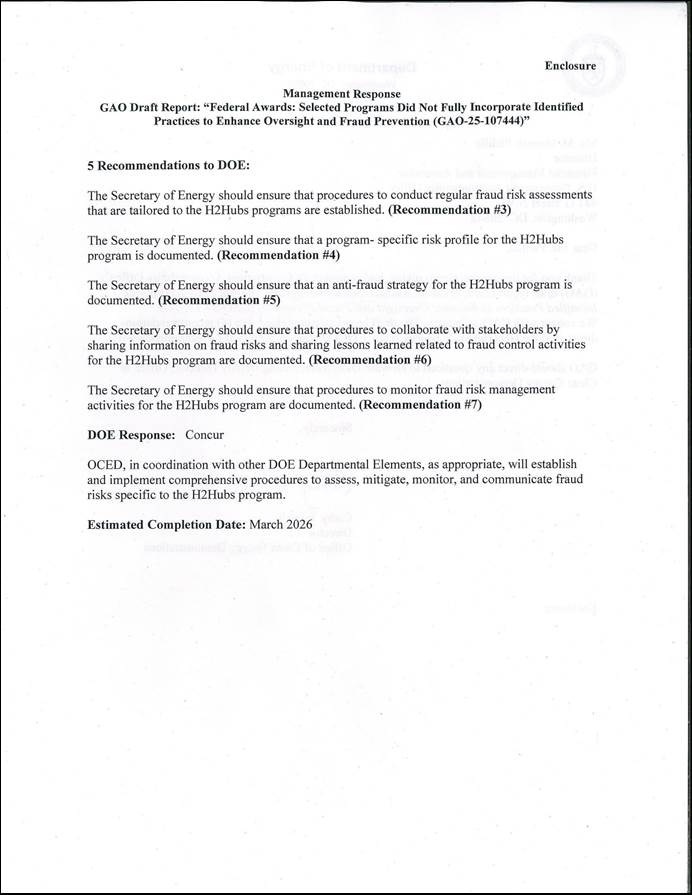

What GAO Found

GAO identified nine requirements and leading practices to oversee and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in awards, including grants, contracts, and loans. As shown in the table, the Federal Communications Commission’s Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries had documented procedures for all nine. GAO found that the other four selected programs—the Department of Commerce’s CHIPS for America Fund, Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (now repealed), Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Center Program, and Department of Energy’s Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs—did not always incorporate these requirements and leading practices in their documented policies and procedures.

GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Selected Requirements and Leading Practices for Selected Programs

|

Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries |

CHIPS for America Fund |

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

Health Center Program |

Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs |

|

|

1. Dedicated entity to lead fraud management activities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Senior Management Council to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Maintain agencywide and program-specific risk profiles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Assess program specific risks, including fraud |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Determine risk responses and document an antifraud strategy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Implement specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the antifraud strategy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the Fraud Risk Framework |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. Evaluate audits, including recovery audits and single audits |

|

|

|

|

|

![]() Fully

met

Fully

met ![]() Partially met

Partially met ![]() Not met

Not met

Source: GAO. | GAO-26-107444

aGAO identified leading practices and requirements from key guidance

documents that it deemed most relevant for oversight of awards.

bThis program was statutorily repealed. Pub. L. No. 119-21, § 60002,

139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4, 2025).

Until agencies establish, document, and implement procedures to fully address these requirements and leading practices, the programs will continue to face increased risks of fraud, waste, and abuse.

Why GAO Did This Study

Proactively managing payment integrity risks is especially important for programs on which agencies expect to spend a large amount of funds. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, and CHIPS and Science Act provided the five agencies in GAO’s review about $227 billion to support their federal programs, including those administering awards of federal financial assistance such as grants.

GAO was asked to review agencies’ oversight of federal awards to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. This report examines (1) what requirements and leading practices agencies can use to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse of federal awards and (2) the extent to which selected programs had policies and procedures that included these to oversee federal awards to help address financial payment and fraud risks.

GAO identified legal requirements and leading practices based on guidance documents for overseeing federal award programs and preventing fraud, waste, and abuse in federal awards. GAO selected five programs based on funding, among other factors, and evaluated whether agencies established policies and procedures for the five selected programs that included those requirements and leading practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations to four of the selected agencies to include the identified requirements and leading practices in their policies and procedures. All agencies except Commerce concurred with the recommendations, as discussed in the report.

Abbreviations

|

ACP |

Affordable Connectivity Program |

|

ASFR |

Assistant Secretary for Financial Resources |

|

C.F.R. |

Code of Federal Regulations |

|

CHCF |

Community Health Center Fund |

|

CHIPS Act |

CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 |

|

CHIPS for America |

Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America |

|

CHIPS |

CHIPS for America Fund |

|

CPO |

CHIPS Program Office |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

E-Rate |

Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries |

|

FCC |

Federal Communications Commission |

|

Fraud Risk Framework |

GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs |

|

GGRF |

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

|

H2Hubs |

Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HRSA |

Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

OCED |

Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations |

|

OIG |

office of inspector general |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PHSA |

Public Health Service Act |

|

R&D |

research and development |

|

SMC |

Senior Management Council |

|

USAC |

Universal Service Administrative Company |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 4, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Effective stewardship of taxpayer funds is a critical responsibility of the federal government. The federal government spends trillions of dollars each year addressing public needs, distributing the funds through payments made directly to and through partners, such as those at the state and local levels.

Managers of federal programs maintain the primary responsibility for enhancing payment integrity. Legislation, guidance the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued, and new internal control standards have increasingly focused on the need for program managers to take a strategic approach to managing payment integrity risks, including the risk of fraud related to federal awards. Proactively managing payment integrity risks can help facilitate a program’s mission and strategic goals by helping to ensure that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

Proactively managing payment integrity risks is especially important in programs for which agencies expect to spend large amounts of federal funds. Recently enacted statutes—such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA),[1] the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA),[2] and the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS Act)[3]—provided significant funding to agencies for federal awards (e.g., grants),[4] which federal agencies are responsible for administering. Among these agencies were the Department of Energy (DOE), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Commerce, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These agencies received approximately $227 billion in appropriations from the IIJA, IRA, and CHIPS Act.[5] Additionally, federal awarding agencies, such as FCC and HHS, receive billions of dollars in appropriations of federal funding each year for their long-standing award programs.

We previously found that some agencies had significant shortcomings in their application of fundamental internal controls and financial and fraud risk management practices. The requirement to distribute funds quickly in 2020 and 2021 to provide COVID-19 relief exacerbated these shortcomings. As a result, billions of dollars were at risk for improper payments, including those from fraud, providing limited assurance that programs effectively met their objectives.[6] For example, we reported on significant shortcomings in fraud risk management at FCC[7] and the Department of Labor.[8] We made 10 recommendations to these two agencies to help address the shortcomings we identified.

You asked us to review agencies’ oversight of federal awards to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. This report (1) identifies what practices agencies can use to oversee or prevent fraud, waste, or abuse in federal awards and (2) examines the extent to which selected programs had policies and procedures that included these identified practices to oversee federal awards to help address financial payment and fraud risks.

To address our first objective, we reviewed relevant applicable legal authorities and guidance and identified legal requirements and leading practices for oversight of awards to external entities and actions agencies could implement in overseeing federal award programs and preventing fraud, waste, and abuse in federal awards. These legal requirements and leading practices were (1) GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework),[9] (2) OMB Circular A-123,[10] (3) OMB’s Transmittal of Appendix C to OMB Circular A-123,[11] and (4) OMB guidance reprinted in Title 2 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) covering audits of nonfederal entities expending federal awards.[12]

From these four documents, we aimed to identify up to two legal requirements or leading practices for each of the five components of internal control: control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring. We primarily used OMB Circular A-123 as criteria for identifying these legal requirements or leading practices because this guidance defines management’s responsibilities for internal control. OMB Circular A-123 highlighted components of our Fraud Risk Framework that we used to identify leading practices, and it also described requirements from OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C and 2 C.F.R. part 200 that we used in selecting our requirements and leading practices. While the nine selected requirements and leading practices are not a complete list of required practices to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse, they are key requirements and leading practices and are specifically aligned with internal control components.

To address our second objective, we selected five programs, one from each of the following agencies: DOE, EPA, Commerce, FCC, and HHS.[13] We selected the programs based on funding amount, program area, and the complexity of the program.[14] We reviewed the design of the monitoring of federal awards for these selected programs by examining the agencies’ policies, procedures, and other relevant documentation and evaluating whether they included the requirements and leading practices identified in our first objective. For instance, where the agency was able to provide evidence showing that it is implementing the requirements and leading practices but did not document doing so in its policies and procedures, we considered that requirement or leading practice to be partially met with respect to our objective. For additional details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Fraud Risk Management

The objective of fraud risk management is to help ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating both fraud likelihood and effects. Although the occurrence of fraud indicates there is a fraud risk, a fraud risk may exist even if actual fraud has not yet occurred or been identified. Effectively managing fraud risk helps to ensure that federal programs fulfill their intended purpose, spend funds effectively, and safeguard assets. Federal program managers maintain the primary responsibility for enhancing program integrity. Our past work, including our Fraud Risk Framework, has found a need for program managers to take a strategic approach to managing risks, including fraud.

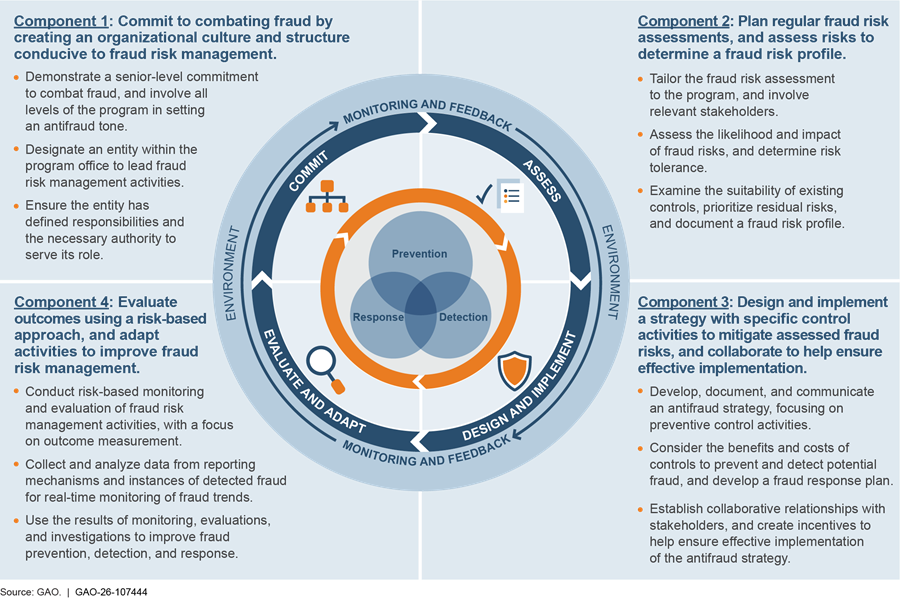

Agencies administering federal funds are responsible for being good stewards of federal resources. To aid program managers in managing fraud risks, our Fraud Risk Framework identifies leading practices and conceptualizes these practices, describing leading practices within four components: commit, assess, design and implement, and evaluate and adapt.[15] (See figure 1.)

In October 2022, OMB issued a Controller Alert requiring agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices.[16] The alert reminds agencies that they should do this as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks—including those that do not rise to the level of enterprise-wide risks.

In addition, OMB Circular A-123 provides guidance to federal managers to improve accountability and effectiveness of federal programs and mission-support operations by implementing enterprise risk management practices and by establishing, maintaining, and assessing internal control effectiveness.[17] Since 1981, OMB Circular A-123 has been at the center of federal requirements to improve accountability in federal programs and operations.

OMB also develops guidance for executive branch agencies on estimating and reporting improper payments. OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C aims to ensure that federal agencies focus on identifying, assessing, prioritizing, and responding to payment integrity risks to prevent improper payments in the most appropriate manner.[18] Agencies are responsible for consulting this OMB guidance and complying with the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 in assessing their programs’ payment integrity and, where necessary, reporting on results and implementing corrective actions.

Further, 2 C.F.R. reprints OMB’s guidance for uniform administrative requirements, cost principles, and audit requirements for grant-awarding agencies and individual federal awarding agencies’ applicable agency-specific federal award regulations.[19] OMB’s guidance in this C.F.R. title applies to federal agencies that make federal awards to nonfederal entities.

For background information on the selected programs, see appendix II.

We Identified Nine Requirements and Leading Practices for Federal Award Oversight and Prevention of Fraud, Waste, or Abuse

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government call for programs and agencies to design and document internal control systems. It organizes specific principles under the five components of internal control, a process that management should use to help an entity achieve its objectives. These five components are (1) control environment, (2) risk assessment, (3) control activities, (4) information and communication, and (5) monitoring.[20]

We identified nine requirements and leading practices from four key guidance documents that would better position agencies to oversee and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in awards, including grants, contracts, and loans.[21] These nine are not a complete list of required practices, but we selected them with the aim of including up to two requirements or leading practices per component of internal control. We used the five components of internal control[22] as a point of reference for selecting and organizing requirements and leading practices from other sources, such as our Fraud Risk Framework. We selected at least one requirement or leading practice, for each component of internal control, that we deemed most significant for oversight of awards to external entities and actionable for agencies to implement. We summarize these practices in table 1.

Table 1: Selected Requirements and Leading Practices GAO Identified to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

|

Leading practice or requirement |

Source |

Requirement or leading practice |

|

Control environment |

|

|

|

10. Create a structure with a dedicated entity to lead fraud management activities |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

11. Have a Senior Management Council to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control |

OMB Circular A-123 |

Requirement |

|

Risk assessment |

|

|

|

12. Maintain agencywide and program-specific risk profiles |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

13. Assess program-specific risks, including fraud and improper payments |

OMB Circular A-123, OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

Control activities |

|

|

|

14. Determine risk responses and document an antifraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

15. Design and implement specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

Information and communication |

|

|

|

Establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the antifraud strategy |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

Monitoring |

|

|

|

16. Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the fraud risk framework |

OMB Circular A-123, Fraud Risk Framework |

Requirement, leading practice |

|

17. Undergo and evaluate audits, including recovery audits and single audits |

OMB Circular A-123, OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C, 2 C.F.R. 200, subpart F |

Requirement |

C.F.R. = Code of Federal Regulations; Fraud Risk Framework = GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (GAO‑15‑593SP); OMB = Office of Management and Budget.

Source: GAO analysis of GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework, OMB Circular A-123, OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C, and 2 C.F.R. 200, subpart F. | GAO‑26‑107444

Note: The practices that we identified from GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework are leading practices, and the practices from OMB Circular A-123, OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C, and OMB’s single audit guidance (at 2 C.F.R. part 200, subpart F) are requirements for executive agencies.

The design of these relevant requirements and leading practices, which are organized under the five internal control components, better position agencies to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, entities must document these internal control components.

Control Environment

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, the control environment component is the foundation for an internal control system, providing the discipline and structure, which affect the overall quality of internal control. The oversight body and management establish and maintain an environment throughout the entity that sets a positive attitude toward internal control. The following leading practice and requirement relate to the control environment:

· Dedicated antifraud entity. Our Fraud Risk Framework states that one leading practice to combat fraud, related to creating an organizational culture and structure conducive to fraud risk management, is to create a structure with a dedicated entity to lead fraud management activities. Specifically, the antifraud entity—which, at management’s discretion, can be program specific or agencywide—manages the fraud risk-assessment process and coordinates antifraud initiatives.

· Senior Management Council (SMC). Additionally, OMB Circular A-123 states that agencies must have an SMC to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control. The SMC must be involved in identifying and ensuring the correction of systemic material weaknesses relating to specific programs. Additionally, the SMC generally determines the program-related significant deficiencies that are material weaknesses to the agency as a whole.

Risk Assessment

The risk assessment component serves to assess the risks facing an entity as it seeks to achieve its objectives, which provides the basis for developing appropriate risk responses. Once an entity establishes an effective control environment, management assesses the risks the entity faces from both external and internal sources. The following requirements and leading practices relate to risk assessment:

· Program-specific risk assessment. Our Fraud Risk Framework and OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C call for agencies to plan regular fraud risk assessments that are program specific, including those related to fraud and improper payments. An effective antifraud entity tailors the approach for carrying out fraud risk assessments to the program.

·

Risk profile. OMB Circular A-123 states that an agency

must maintain an agencywide risk profile that includes an evaluation of fraud

risks and uses a risk-based approach to design and implement control activities

to mitigate identified material fraud risks. In addition, our Fraud Risk

Framework states that agencies should identify and assess risks to determine a

program’s fraud risk profile.

Control Activities

The control activities component consists of the actions management establishes through policies and procedures to achieve objectives and respond to risks in the internal control system, which includes the entity’s information system.[23] Management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks and should also implement these control activities through policies. The following leading practices relate to control activities:

· Antifraud strategy. Our Fraud Risk Framework states that one leading practice is to determine risk responses and document an antifraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile. Specifically, managers should develop, document, and communicate to employees and stakeholders what the antifraud strategy—which can be agencywide or program specific—should be. It should describe the program’s existing and new control activities for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud and for monitoring and evaluation. Key elements of an antifraud strategy include the establishment of roles and responsibilities, activities to manage fraud risks, timing of fraud management activities, links to external and internal residual fraud risks, and processes for communicating the strategy.

·

Specific control activities. Additionally, our Fraud Risk

Framework notes that another leading practice is to design and implement

specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud. These control

activities generally include policies, procedures, and techniques, and

mechanisms such as data analytics activities, fraud awareness initiatives,

reporting mechanisms, and employee integrity activities to prevent and detect

potential fraud.

Information and Communication

The information and communication component focuses on the quality information that management and personnel communicate and use to support the internal control system. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, effective information and communication are vital for an entity to achieve its objectives. Specifically, entity management needs access to relevant and reliable communication related to internal and external events. The following leading practice relates to information and communication:

·

Collaboration. Our Fraud Risk Framework describes the

leading practice of establishing collaborative relationships with stakeholders

and creating incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the

antifraud strategy. Federal managers who effectively manage fraud risks

collaborate and communicate with these internal stakeholders, such as other

offices within the agency, including legal and ethics offices and offices

responsible for other risk management activities—and external stakeholders,

such as other federal agencies, private-sector partners, state and local

governments, law enforcement entities, and contractors. They communicate with

these stakeholders to share information on fraud risks and emerging fraud

schemes as well as lessons learned related to fraud control activities.

Monitoring

The monitoring component involves the activities that management establishes and operates to assess the quality of performance over time and promptly resolve the findings of audits and other reviews. Because internal control is a dynamic process that must be adapted continually to the risks and changes an entity faces, monitoring of the internal control system is essential in helping internal control remain aligned with changing objectives, environments, laws, resources, and risks. Internal control monitoring assesses the quality of performance over time and promptly resolves the findings of audits and other reviews. The following leading practice and requirements relate to monitoring:

· Risk-based monitoring. Our Fraud Risk Framework states that one leading practice is to conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the Fraud Risk Framework. Managers monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of preventive activities, including fraud risk assessments, the antifraud strategy, and controls to detect fraud and response efforts. Monitoring and evaluation activities can include unannounced examinations, site visits, covert testing, and surveys of stakeholders responsible for fraud controls. In addition, effective managers of fraud risks collect and analyze data, including data from reporting mechanisms and instances of detected fraud, for real-time monitoring of fraud trends and identification of potential control deficiencies.

·

Audits. Federal guidance requires agencies to undergo and

evaluate audits, including recovery audits and single audits. Specifically, OMB

Circular A-123 Appendix C states that all programs that expend $1 million or

more annually should be considered for recovery audits and must conduct them if

they would be cost-effective.[24]

Additionally, OMB’s single audit guidance states that awarding agencies are

responsible for issuing a management decision in response to audit findings

within six months of the acceptance of the single audit report by the Federal

Audit Clearinghouse, which includes a description of planned corrective actions

to address single audit findings.[25]

Identifying and managing single audit findings in a timely manner could reduce

the risk of fraud, waste, or abuse of federal resources.

Agencies Generally Did Not Fully Establish Policies and Procedures to Help Address Fraud Risks for Selected Programs

In our evaluation of selected programs, we found that most agencies did not fully establish policies and procedures to help prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in federal awards for our selected programs. Four of the five selected programs did not include all nine requirements and leading practices in their policies and procedures. One selected program, FCC’s Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries (E-Rate), included all nine requirements and leading practices in its policies and procedures.[26]

Most Agencies Designed a Control Environment for Their Selected Programs with Identified Requirements and Practices; One Did Not

In our evaluation of the design of selected programs’ control environments, we found that while most of the selected programs had policies and procedures that included the selected requirements and leading practices in their control environment design, one did not. These include our leading practice of creating a structure with a dedicated entity to lead fraud risk management activities and OMB requirements for establishing an SMC (see table 2).

Table 2: GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Control Environment Related to Selected Practices to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

|

Selected requirements and leading practices (source) |

CHIPS |

H2Hubs |

GGRFa |

E-Rate |

Health Center Program |

|

Create a structure with a dedicated anti-fraud entity to lead fraud management activities (Fraud Risk Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Have a Senior Management Council to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control (OMB Circular A-123) |

|

|

|

|

|

![]() Agencies had documented procedures in

place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies had documented procedures in

place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

CHIPS: CHIPS for America Fund

E-Rate: Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries

Fraud Risk Framework: GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Programs

GGRF: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

H2Hubs: Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program

OMB: Office of Management and Budget

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107444

aDuring the time period in which we conducted this engagement, Congress repealed EPA’s GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. VI, § 60002, 139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4, 2025).

All five selected programs created a structure with a dedicated entity to lead fraud management activities. For example, DOE’s Senior Assessment Team charter states that it functions as an advisory committee responsible for providing oversight for DOE’s Fraud Risk Management Framework to comply with governing statutory, regulatory, and departmental guidance while mitigating fraud risks. Its duties include leading the development and implementation of DOE’s Fraud Risk Management Framework and developing DOE’s Antifraud Strategy.

Four of the selected programs had an SMC to assess and monitor any deficiencies in internal control. For example, HHS’s Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) uses the Enterprise Governance Board as the executive review and advisory body responsible for making recommendations on division-wide areas of strategic importance, including programs like the Health Center Program. The board’s scope includes strategic management, ensuring coordination of activities across HRSA, and operations issues. In addition, the board is responsible for overseeing and monitoring progress on resolving any internal control deficiencies identified.

However, EPA did not establish an SMC. According to OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, agencies must have a SMC to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control.[27] This council should be responsible for overseeing the timely implementation of corrective actions related to material weaknesses. Such a council is also useful in determining when an entity has taken sufficient action to declare that it has corrected a significant deficiency or material weakness.

EPA has not established an agency-wide SMC that assesses and monitors deficiencies in internal control. In April 2025, EPA officials told us that the Executive Leadership Committee oversees enterprise risk management activities but does not focus on fraud risk management activities. In addition, EPA officials stated that they are developing fraud risk management structures, as EPA has not administered programs of this size that have received a large amount of funding from the IRA (which appropriated funding for the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) that Congress recently repealed) and the IIJA. According to EPA officials, as of April 2025 they are discussing improvements to the governance structure with the intentions to implement changes in the future. They added that they are in the process of developing a schedule to document EPA’s governance structure but do not have a timeline for when they will complete this documentation.

Although Congress repealed the GGRF, by establishing an SMC, EPA will be better positioned to effectively assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control, which will better position the agency to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in other EPA programs.

Two Agencies Did Not Fully Follow Risk Assessment Requirements and Leading Practices for Selected Programs

In our evaluation of the design of selected programs’ risk assessment, we found that while three of the programs fully included our selected requirements and leading practices in their risk assessment design, two did not. (See table 3.)

Table 3: GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Risk Assessment Related to Selected Practices to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

|

Selected requirements and leading practices (source) |

CHIPSa |

H2Hubs |

GGRFb |

E-Rate |

Health Center Program |

|

Maintain agencywide and program-specific risk profiles (OMB Circular A 123, Fraud Risk Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assess program specific risks, including fraud (Fraud Risk Framework) and improper payments (OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C) |

|

|

|

|

|

![]() Agencies

had documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies

had documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

CHIPS: CHIPS for America Fund

E-Rate: Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries

Fraud Risk Framework: GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Programs

GGRF: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

H2Hubs: Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program

OMB: Office of Management and Budget

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107444

aFor CHIPS, our review was based on the CHIPS Program Office’s preaward risk documentation.

bDuring the time period in which we conducted this engagement, Congress repealed EPA’s GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. VI, § 60002, 139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4, 2025).

Three out of the five selected programs fully followed OMB requirements to

maintain an agencywide risk profile and our identified leading practice to

maintain a program-specific risk profile. For example, the Universal Service

Administrative Company (USAC), which administers E-Rate under FCC oversight and

direction, documented both an entity-level risk profile, which includes

consideration of fraud risk as well as an E-Rate program-specific fraud risk

profile. The risk profiles included a score for each area of risk to identify

its severity.

In addition, three out of the five selected programs fully assessed program-specific risks, including our identified leading practice of assessing fraud risks and OMB requirements to assess improper payment risks. For example, USAC has a fraud risk management policy stating that it will conduct program fraud risk assessments biannually or when program changes necessitate.

DOE and HHS Have Not Planned Regular Fraud Risk Assessments for Their Respective Selected Programs

According to our Fraud Risk Framework, agencies should plan regular fraud risk assessments that are tailored to each program.[28] This includes planning to conduct fraud risk assessments at regular intervals and when there are changes in a program or its operating environment. In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that documentation is a necessary part of an effective internal control system.[29] It also states that management develops and maintains documentation of its internal control system.

Two selected programs did not include or document effective processes for conducting periodic fraud risk assessments in their policies and procedures.

· H2Hubs. DOE has not documented a fraud risk assessment tailored to the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program (H2Hubs) and has not documented in its policies and procedures how often risk assessments would take place. In April 2025, DOE officials stated that the department discussed program risks for H2Hubs but did not provide us with formal documentation of risk assessment plans. DOE officials stated that they believed that a project-level fraud risk policy would be an inefficient use of resources at this time, as H2Hubs has only recently issued awards. In addition, DOE officials noted that it is difficult to determine fraud risk when the agency is still determining the details of the program. DOE stated that it will identify and investigate these risks in fiscal years 2025 and 2026.

· Health Center Program. HHS conducted fraud risk assessments for the Health Center Program but did not have policies in place documenting the frequency with which these program-specific fraud risk assessments should occur. HHS has drafted fraud risk management guidance (which it has not yet finalized) that encourages but does not require divisions to assess fraud risks on an annual basis. In April 2025, HHS officials stated that the department initiated drafting its Fraud Risk Implementation Plan in spring 2018 and plans to finalize this guidance in 2025. Officials stated that HHS prioritized actively conducting this work—identifying risks and addressing them across programs—over formal documentation of the processes in the earlier stages of the program’s efforts to address fraud risks. They stated that the staff responsible for leading fraud risk management activities have competing priorities, as they are also responsible for implementation of the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019.[30]

By planning and documenting regular fraud risk assessments that are tailored to the program, agencies will be in a better position to develop a specific approach for addressing fraud risks and respond to program needs.

DOE and HHS Did Not Create Fraud Risk Profiles for Their Respective Selected Programs

According to OMB Circular A-123, agencies must maintain a risk profile.[31] The primary purpose of a risk profile is to provide a thoughtful analysis of the risks an agency faces toward achieving its strategic objectives arising from its activities and operations and to identify appropriate options for addressing significant risks.

In addition, our Fraud Risk Framework states that agencies should identify and assess risks to determine the program’s fraud risk profile.[32] This includes identifying inherent fraud risks, assessing the likelihood and effect of fraud risks, determining fraud risk tolerance, and examining the suitability of existing fraud controls and prioritizing residual fraud risks. As previously discussed, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that documentation is a necessary part of an effective internal control system.[33]

Two selected programs did not create fraud risk profiles.

· H2Hubs. Although the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) documented a department-wide risk profile, it has not documented a fraud risk profile for H2Hubs. In April 2025, DOE officials stated that the department discussed program risks for H2Hubs but did not provide us with formal documentation of a fraud risk profile. DOE officials stated they that believed that a project-level fraud risk policy would be an inefficient use of resources at this time, as H2Hubs has only recently issued awards. In addition, DOE officials noted that it is difficult to determine fraud risk when the agency is still determining the details of the program. DOE stated that it will identify and investigate these risks in fiscal years 2025 and 2026.

· Health Center Program. HHS was unable to provide us with either an agencywide risk profile or risk profile specific to the Health Center Program. In April 2025, HHS officials told us that the department is working on helping its bureaus develop program-specific fraud risk profiles in the upcoming fiscal year; it then plans to develop an agencywide fraud risk profile. They also stated that HHS prioritized actively conducting the work—identifying risks and addressing them across programs—over formal documentation of the processes in the earlier stages of the program’s efforts to address fraud risks. They stated that the staff responsible for leading fraud risk management activities have competing priorities, as they are also responsible for implementation of the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019.

By creating agencywide and program-specific fraud risk profiles, DOE and HHS will be in a better position to determine which specific control activities to design and implement for risk mitigation.

Three Selected Programs Fully Included Identified Practices Related to Control Activities in Their Policies and Procedures

In our evaluation of the design of the five selected programs’ control activities, we found that while three had policies and procedures that included the selected requirements and leading practices, two did not. (See table 4.)

Table 4: GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Control Activities Related to Selected Practices to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud

|

Selected requirements and leading practices (source) |

CHIPSa |

H2Hubsb |

GGRFc |

E-Rate |

Health Center Programd |

|

Determine risk responses and document an antifraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile (Fraud Risk Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Design and implement specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud (Fraud Risk Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

![]() Agencies

had documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies

had documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

CHIPS: CHIPS for America Fund

E-Rate: Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries

Fraud Risk Framework: GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Programs

GGRF: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

H2Hubs: Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107444

aFor CHIPS, our review was based on the CHIPS Program Office’s preaward risk documentation.

bFor H2Hubs, we identified documented control activities, such as invoice reviews, to help prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse. However, until H2Hubs determines risk responses and documents an antifraud strategy, it is unclear whether these control activities will address all the fraud risks associated with the program.

cDuring the time period in which we conducted this engagement, Congress repealed EPA’s GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. VI, § 60002, 139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4, 2025).

dFor the Health Center Program, HHS has drafted a fraud risk management implementation plan. However, the guidance is not yet final. We identified documented control activities, such as site visits, financial assessments, and specialized reviews of moderate and high-risk organizations to help prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse.

Three selected programs documented an antifraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile. For example, USAC developed an entity-wide antifraud strategy, based on assessed risks, that covers E-Rate. This antifraud strategy details USAC’s implementation of the four components of our Fraud Risk Framework. Specifically, USAC’s antifraud strategy requires (1) USAC’s leadership to commit to creating an antifraud culture; (2) USAC to assess fraud risks through risk assessments, audits, and internal control reviews; (3) USAC to design and implement antifraud controls; and (4) USAC to monitor and perform evaluations to ascertain fraud risk management and detection activities.

In addition, EPA guidance states that agency senior leaders conduct strategic reviews to assess progress toward agency objectives. During these reviews, officials look at risk assessments and identified fraud risks and use this information to complete a summary of findings template that documents accomplishments, challenges, risks, and opportunities. EPA had also identified high-level risks and mitigation strategies for the recently repealed Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

All five selected programs designed and implemented specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud. For example, OCED guidance details requirements to conduct prepayment and postpayment reviews on invoices that award recipients submit. Prepayment reviews involve reviewing invoices for cost allowability and reasonableness; postpayment reviews involve obtaining recipient invoice and cost and transaction details and identifying risks of potential fraud, waste, abuse, or mismanagement. Such reviews of invoice documentation can (1) help reduce the risk of improper payments, including fraud, and (2) identify issues and concerns earlier than audit report findings.

DOE and HHS Did Not Document an Antifraud Strategy for Their Respective Selected Programs

Our Fraud Risk Framework states that agencies should determine risk responses and document and implement an antifraud strategy based on the fraud risk profile. This includes using the fraud risk profile to help decide how to allocate resources to respond to residual fraud risks. It also includes developing, documenting, and communicating an antifraud strategy to employees and stakeholders that describes the program’s activities for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud as well as monitoring and evaluation. The antifraud strategy can help programs establish roles and responsibilities; describe the program’s activities for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud; create timelines for implementing fraud risk management activities; and communicate fraud risk management activities to employees and stakeholders.

Two selected programs did not document an antifraud strategy.

· H2Hubs. DOE did not document an antifraud strategy for H2Hubs. In April 2025, DOE officials told us that although they do not have an antifraud strategy in place specific to H2Hubs, the agency has policies in place to prevent fraud. DOE officials stated that they believed that at this time a project-level fraud risk policy would be an inefficient use of resources as the program has only recently issued awards. One DOE official also noted that as H2Hubs is a new program, officials did not know how to implement our nine identified requirements and leading practices. However, our Fraud Risk Framework states that the purpose of proactively managing fraud risks is to facilitate, not hinder, the program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

In addition, DOE officials stated that awardees are responsible for writing and implementing policies and procedures related to fraud, waste, and abuse. However, our Fraud Risk Framework states that managers of federal programs maintain the primary responsibility for enhancing program integrity.

· Health Center Program. HHS did not document an antifraud strategy for the Health Center Program. In April 2025, HHS officials told us that HHS plans on working with its divisions to identify and map fraud risks. HHS officials noted that HHS initiated drafting its Fraud Risk Implementation Plan in spring 2018 and plans on finalizing this guidance in 2025. However, the draft guidance does not discuss the control activities HHS has in place to address fraud risks. HHS officials also stated that they prioritized actively conducting the work—identifying risks and addressing them across programs—over formal documentation of the processes in the earlier stages of the program’s efforts to address fraud risks. They stated that the staff responsible for leading fraud risk management activities have competing priorities, as they are also responsible for implementation of the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019.

By designing and documenting an antifraud strategy, agencies will be better positioned to effectively design a response to analyzed risks.

Most Selected Programs Included the Identified Leading Practice to Communicate Information in Their Policies and Procedures

In our evaluation of the design of selected programs’ information communication, we found that most (four of the five) selected programs included our selected criteria in their design of information communication, and one did not. (See table 5.)

Table 5: GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Information Communication Related to Selected Practices to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud

|

Selected requirements and leading practices (source) |

CHIPS |

H2Hubs |

GGRFa |

E-Rate |

Health Center Program |

|

Establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the antifraud strategy (Fraud Risk Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

Agencies had documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

Agencies had examples of selected

criteria implementation, but did not have documented procedures in place

related to the selected criteria.

CHIPS: CHIPS for America Fund

E-Rate: Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries

Fraud Risk Framework: GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Programs

GGRF: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

H2Hubs: Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107444

aDuring the time period in which we conducted

this engagement, Congress repealed EPA’s GGRF and rescinded the unobligated

funding. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. VI, § 60002, 139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4,

2025).

Four selected programs included policies and procedures for our identified leading practice to establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the antifraud strategy. For example, EPA’s fraud risk management guidance encourages program offices to convene key stakeholders to help identify fraud risks. In addition, EPA leveraged interagency expertise to develop its award agreements for the recently repealed GGRF, and hosted public webinars with key stakeholder groups, receiving input from states, local governments, and Tribal governments. According to the EPA, the GGRF office also hosted grantee meetings and a grantee file-sharing platform to provide information about implementing the GGRF, such as materials from grant management workshops, frequently asked questions, and guidance documents.

However, DOE did not document collaborative relationships with stakeholders for H2Hubs. Our Fraud Risk Framework states that agencies should establish collaborative relationships with internal and external stakeholders to share information on fraud risks and share lessons learned related to fraud control activities. Internal stakeholders include other offices within the agency, such as legal and ethics offices and offices responsible for other risk management activities, while external stakeholders can include other federal agencies, private-sector partners, state and local governments, law enforcement entities, and contractors.

Managers who effectively manage fraud risks collaborate and communicate with these internal and external stakeholders to share information on fraud risks and emerging fraud schemes, as well as lessons learned related to fraud control activities. Managers can do this through task forces, working groups, or communities of practice.

DOE did not provide evidence of establishing collaborative relationships with stakeholders and creating incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the antifraud strategy for H2Hubs. In April 2025, DOE officials told us that they believe local communities are invested in H2Hubs projects and willing to communicate any problems that arise. However, they did not provide evidence of this occurring in any formal or documented way. DOE officials stated that, at this time, they believed that a project-level fraud risk policy for H2Hubs would be an inefficient use of resources as DOE has only recently issued awards. One DOE official also noted that, as H2Hubs is a new program, they did not know how to implement our nine key criteria. However, our Fraud Risk Framework states that the purpose of proactively managing fraud risks is to facilitate, not hinder, the program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

In addition, DOE officials stated that awardees are responsible for writing and implementing policies and procedures related to fraud, waste, and abuse. However, our Fraud Risk Framework states that managers of federal programs maintain the primary responsibility for enhancing program integrity.

By documenting procedures for establishing collaborative relationships with stakeholders, DOE will be better positioned to effectively share information on fraud risks and share lessons learned that can be used to improve the design and implementation of fraud risk management activities. Empowering stakeholders with such information can help reduce the risk of fraud.

Four Selected Programs Did Not Fully Establish Procedures Related to Selected Requirements and Leading Practices to Monitor Fraud Risk

In our evaluation of the design of selected programs’ monitoring, we found that while one of the selected programs included both of our identified requirements and leading practices in its design of monitoring activities, four did not. (See table 6.)

Table 6: GAO Assessment of Agencies’ Design of Monitoring Related to Selected Practices to Oversee Federal Awards and Prevent Fraud, Waste, and Abuse

|

Selected requirements and leading practices (source) |

CHIPS |

H2Hubs |

GGRFa |

E-Rate |

Health Center Program |

|

Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the Fraud Risk Framework (Fraud Framework) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergo and evaluate audits (OMB Circular A-123), including recovery audits (OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C) and single audits (2 C.F.R. part 200, subpart F) |

|

|

|

|

|

Agencies had documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies

did not have documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies

did not have documented procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

![]() Agencies

had examples of selected criteria implementation, but did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

Agencies

had examples of selected criteria implementation, but did not have documented

procedures in place related to the selected criteria.

C.F.R.: Code of Federal Regulations

CHIPS: CHIPS for America Fund

E-Rate: Universal Service Program for Schools and Libraries

Fraud Risk Framework: GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal

Programs

GGRF: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

H2Hubs: Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program

OMB: Office of Management and Budget

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107444

aDuring the time period in which we conducted this engagement, Congress repealed EPA’s GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding. See Pub. L. No. 119-21, tit. VI, § 60002, 139 Stat. 72, 154 (July 4, 2025).

Two out of the five selected programs fully followed our identified leading practice of establishing procedures to conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the Fraud Risk Framework. For example, USAC’s fraud control plan states that USAC performs monitoring activities that include selecting, developing, and performing ongoing evaluations to ascertain whether each of the fraud risk management principles is functioning.

Four out of the five selected programs established procedures to follow OMB requirements to undergo and evaluate audits, including OMB requirements to conduct recovery audits and OMB’s Uniform Guidance requirements related to single audits. For example, DOE’s policies state that payment reporting sites shall review their different types of programs and activities and prioritize conducting payment recovery audits on categories with a higher potential for overpayments and recoveries. DOE’s policies also state that auditors will conduct recovery audits in accordance with guidance in OMB Circular A-123, Appendix C, Requirements for Payment Integrity Improvement. Additionally, National Institute of Standards and Technology guidance requires that management decision letters be issued within 6 months following the Federal Audit Clearinghouse’s acceptance of the single audit report. These letters must include a timetable for corrective action to address single audit findings, as well as the status of the corrective action plan.

DOE, EPA, and HHS Did Not Have Procedures to Fully Monitor Fraud Risk Management Activities for Selected Programs

According to our Fraud Risk Framework, agencies should conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the fraud risk framework.[34] This includes monitoring the effectiveness of preventive activities, including fraud risk assessments, the antifraud strategy, controls to detect fraud, and fraud response efforts. Monitoring activities, because of their ongoing nature, can serve as an early warning system for managers to help identify and promptly resolve issues through corrective actions and ensure compliance with existing statutes, regulations, and standards. Evaluations, like monitoring activities, are reviews that focus on the program’s progress toward achieving the objectives of fraud risk management. However, evaluations differ from monitoring activities in that they are individual systematic studies conducted periodically or on an ad hoc basis and are typically more in-depth examinations to assess the performance of activities and identify areas of improvement. Four selected programs did not establish effective processes for monitoring fraud risk management activities.H2Hubs. DOE officials were unable to provide evidence that they monitor fraud risk management activities for H2Hubs, including all components of the fraud risk framework. In April 2025, DOE officials told us that they will measure the project, technical, financial, and fraud risks annually and identify lessons learned and changes made. However, DOE has not provided documentation showing this is the case. DOE officials stated that they believe developing a project-level fraud risk management policy would be an inefficient use of resources as they have only recently issued awards. DOE official also noted that, as H2Hubs is a new program, they did not know how to implement our nine key criteria. However, our Fraud Risk Framework states that the purpose of proactively managing fraud risks is to facilitate, not hinder, the program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

· GGRF. EPA provided documentation describing its procedures to monitor some components of the fraud risk framework for the recently repealed GGRF. EPA included monitoring activities in its draft fraud risk management guidance, which included some, but not all, of the monitoring components. In April 2025, EPA officials told us that, based on prior years, EPA programs do not typically have much fraud. Because of this, EPA’s fraud risk monitoring efforts were more proactive in nature, focusing on the vetting and ensuring compliance of grantee applicants and award recipients, according to EPA officials. As discussed in Appendix II, in July 2025, Congress repealed the GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding.

· Health Center Program. HHS officials did not provide evidence that they monitor fraud risk management activities for the Health Center Program, including all components of the fraud risk framework. HHS developed draft fraud risk management guidance that includes monitoring fraud risk management activities. However, this guidance is not yet final. In April 2025, HHS officials told us that they initiated drafting their Fraud Risk Implementation Plan in spring 2018 and plan on finalizing this guidance in 2025. They also stated that HHS prioritized actively conducting the work—identifying risks and addressing them across programs—over formal documentation of the processes in the earlier stages of the program’s efforts to address fraud risks. They also stated that the staff responsible for leading fraud risk management activities have competing priorities, as they are also responsible for implementation of the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019.

By establishing procedures for conducting risk-based monitoring and evaluating all components of the Fraud Risk Framework, agencies will be in a better position to provide assurance that they are effectively preventing, detecting, and responding to potential fraud.

Commerce Did Not Evaluate the CHIPS Program for Recovery Audits

According to the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 and OMB Circular A-123 Appendix C, all programs that expend $1 million or more annually should be considered for recovery audits. Recovery audits are reviews of accounting and financial records, supporting documentation, and other pertinent information that are specifically designed to identify overpayments. For a variety of reasons, some in both private industry and government agencies process payments incorrectly. For instance, vendors make pricing errors on their invoices, forget to include discounts they advertised to the general public, neglect to offer allowances and rebates, or miscalculate freight charges. Overpayments result when vendors do not catch these mistakes.[35]

Commerce officials were unable to provide evidence showing that they consider programs expending $1 million or more annually for recovery audits. Commerce officials told us that their understanding was that recovery audits occurred after fraud was identified, such as through improper payment activities. As such, Commerce does not proactively consider its programs for recovery audits. Commerce officials told us that they have not identified any overpayments in the CHIPS program. In addition, they told us that CPO’s Risk Office is actively developing and honing its compliance and monitoring framework, which will include formal consideration of recovery audit applicability as CHIPS disbursements increase and sufficient payment activity is available for meaningful evaluation. By considering the use of recovery audits, Commerce will be better positioned to effectively identify and recover overpayments within the CHIPS program.

Conclusions

Proactively managing fraud risk is critical to facilitate program missions and strategic goals as it ensures that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes. This is especially important in programs that have received substantial funding. For example, recent legislation provided the five agencies in our review approximately $227 billion to support their federal programs, including those that administer awards of federal financial assistance, such as grants.[36] Given the nature of federal programs and related spending, this amount is inherently at risk for fraud. Following requirements and leading practices from OMB and GAO can help agencies prevent fraud, waste, and abuse to effectively steward taxpayer dollars. Documenting how policies and procedures reflect these requirements and leading practices is necessary for agencies to demonstrate effective design and implementation of an internal control system.

Except for FCC, the selected agencies we reviewed have not fully designed and documented their policies and procedures related to nine requirements and leading practices that we identified for preventing fraud, waste, and abuse. For example, Commerce has not yet included one of the nine identified requirements and leading practices in its policies and procedures, such as evaluating audits. Further, DOE has not yet included five of the nine identified requirements and leading practices in its policies and procedures, such as assessing program-specific fraud risks. In addition, EPA did not included two of the nine identified requirements and leading practices in its policies and procedures for the now repealed GGRF. One of these identified requirements, having an SMC to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control, still applies to EPA as an agency-wide requirement. Also, HHS has not yet included four of the nine identified requirements and leading practices in its policies and procedures, such as maintaining a fraud risk profile. Until these agencies design and implement these identified requirements and leading practices, they will continue to face an increased risk of fraud, waste, and abuse in the selected programs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making 12 recommendations, one to Commerce, five to DOE, one to EPA, and five to HHS. Specifically:

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that consideration of the use of recovery audits of potential overpayments for the CHIPS for America Fund is documented. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that procedures to conduct regular fraud risk assessments that are tailored to H2Hubs are established. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that a program-specific risk profile for H2Hubs is documented. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that an antifraud strategy for H2Hubs is documented. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that procedures to collaborate with stakeholders by sharing information on fraud risks and sharing lessons learned related to fraud control activities for H2Hubs are documented. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that procedures to monitor fraud risk management activities for H2Hubs are documented. (Recommendation 6)

The Administrator of EPA should ensure that a Senior Management Council to assess and monitor deficiencies in internal control is established. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that HHS’s policies documenting how often HHS programs should conduct fraud risk assessments are finalized. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that an agencywide risk profile for HHS is documented. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that a program-specific risk profile for the Health Center Program is documented. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that an antifraud strategy for the Health Center Program is documented. (Recommendation 11)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that procedures to monitor fraud risk management activities for the Health Center Program are documented. (Recommendation 12)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOE, EPA, Commerce, FCC, and HHS for review and comment. We received written comments from DOE, EPA, Commerce, and HHS, which are reproduced in appendixes III to VI, respectively, and summarized below. We also received technical comments from EPA, Commerce, and HHS, which we incorporated as appropriate. FCC officials informed us that they had no comments on the report.

In its written comments, DOE concurred with the five recommendations made to it and described actions to implement them. DOE stated that OCED, in coordination with other DOE departmental elements as appropriate, will establish and implement comprehensive procedures to assess, mitigate, monitor, and communicate fraud risks specific to the H2Hubs program.

In its written comments, EPA concurred with the recommendation made to it and described actions to implement the recommendation. EPA described its recent establishment of a Risk Management Council as the principal governance body responsible for providing executive-level oversight and strategic direction for the Enterprise Risk Management Program. Our report originally included a second recommendation on incorporating all components of the fraud risk framework into EPA’s procedures to monitor fraud risk management activities for the GGRF. However, as discussed in Appendix II, in July 2025 Congress repealed the GGRF and rescinded the unobligated funding. Because of this, we concluded that the recommendation was no longer applicable and removed it from the report.

In its written comments, Commerce stated that it did not concur with the draft report’s two recommendations. For the first recommendation regarding the use of internal and external evaluation to monitor the effectiveness of internal control and enterprise risk management systems, Commerce stated in its letter that it had fully met the recommendation. Commerce provided us with documentation of procedures showing that it uses internal and external evaluation to monitor the effectiveness of internal control and enterprise risk management systems. After reviewing the documentation, we determined that Commerce documented its use of internal and external evaluations to monitor the effectiveness of internal control and enterprise risk management systems. Thus, we modified the report and removed that recommendation.

For the second recommendation regarding consideration of the use of recovery audits of potential overpayments, Commerce stated in its letter that it periodically considers whether the agency should perform recovery audits across the agency, and noted that it has not identified any areas department-wide or otherwise where it might be cost effective to conduct recovery audits. However, Commerce did not provide evidence showing that it documents this periodic consideration in its policies and procedures. As we discuss in the report, documentation is a necessary part of an effective internal control system. By documenting periodic consideration of the use of recovery audits, Commerce will be better positioned to effectively identify and recover overpayments within the CHIPS program.

In its written comments, HHS concurred with the five recommendations made to it and described actions to implement them. HHS stated that it would finalize its fraud risk management guidance and take steps to document an agency-wide fraud risk profile in fiscal year 2026. In addition, HHS noted that it is currently in the process of finalizing its Health Center Program risk profile, antifraud strategy, and procedures to monitor fraud risk management activities.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Energy, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov/

If you or your staffs have any questions about this report, please contact me at padillah@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

M. Hannah Padilla

Director, Financial Management and Assurance

List of Requesters

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gus M. Bilirakis

Chairman

Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Richard Hudson

Chairman

Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Robert E. “Bob” Latta

Chairman

Subcommittee on Energy

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gary Palmer

Chairman

Subcommittee on Environment

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable H. Morgan Griffith

Chairman

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Joyce, M.D.

Chairman

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Earl L. “Buddy” Carter

House of Representatives

This report (1) identifies what practices agencies can use to oversee or prevent fraud, waste, or abuse in federal awards and (2) examines the extent to which selected programs had policies and procedures that included these requirements and leading practices to oversee federal awards to help address financial payment and fraud risks.

For our first objective, we identified sources of information, including laws, regulations, and guidance describing requirements and leading practices to oversee and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in federal awards. We identified four guidance documents describing requirements and leading practices to oversee and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in awards, including grants, contracts, and loans:

1. GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework);[37]

2. Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control;[38]

3. OMB’s Transmittal of Appendix C to OMB Circular A-123, Requirements for Payment Integrity Improvement;[39] and

4. OMB’s Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, reprinted in Title 2, U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.), part 200.[40]