INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT

DOD Needs to Address Security Risks of Publicly Accessible Information

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Joe Kirschbaum at KirschbaumJ@gao.gov or Marisol Cruz Cain at CruzCainM@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

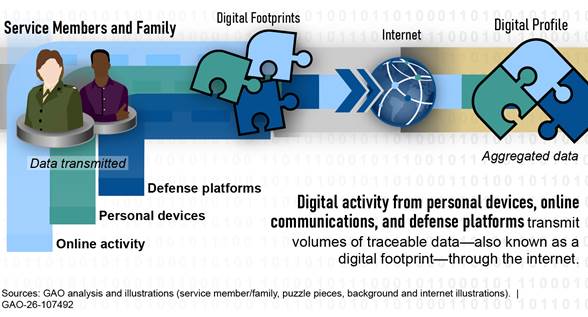

Digital activity from personal and government devices, online communications, and defense platforms such as ships and aircraft can generate volumes of traceable data, known as digital footprints. When these digital footprints are aggregated into a digital profile, they can threaten Department of Defense (DOD) personnel and their families, operations, and ultimately national security.

GAO determined that three of five offices under the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) have issued policies and guidance on the risks associated with the public accessibility of DOD’s digital information. However, the policies and guidance are narrowly focused, do not include all stakeholders, and do not include all relevant security areas. As a cross-functional governance body that includes stakeholders across DOD, the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee is well-positioned to lead a department-wide collaborative assessment of policies and guidance on digital footprint and profile risks. Without such an assessment, DOD will have difficulty in determining whether risks are being sufficiently managed within the boundaries of their legal authorities. Also, DOD will face ever-increasing threats to personnel privacy and safety, mission success, and national security.

GAO also determined that 10 DOD components were not fully addressing two areas essential to reducing the risk of digital threats—training and security assessments.

· Nine of ten components’ training materials did not consistently train personnel on risks of digital information in the public across all relevant security areas.

· Eight of ten components did not conduct assessments of threats across the required security areas of force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, and operations security. Instead, most components focused assessment efforts solely on operations security.

Why GAO Did This Study

Massive amounts of traceable data about military personnel and operations now exist due to the digital revolution. Public accessibility of this data enables malicious actors to exploit critical information and jeopardize DOD’s mission and the safety of its personnel.

Senate Report 118-58 and House Report 118-301 include provisions that GAO assess DOD’s efforts to mitigate national security risks and assess DOD components’ efforts to protect the digital footprint of DOD personnel. This report assesses the extent to which (1) OSD has taken action to reduce risks to DOD personnel and operations and (2) DOD components have conducted training and assessments to reduce risk to DOD personnel and operations. The report also describes security risks of publicly accessible data about DOD personnel and operations.

GAO focused on actions taken by five OSD offices and 10 select DOD components with security responsibilities—the five services and five other cognizant components such as U.S. Cyber Command and Space Force. GAO reviewed policies and documentation from these offices and components, and interviewed agency officials regarding actions taken to reduce information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations to DOD to assess its policies and guidance; collaborate to reduce risks; provide training on the digital environment and its associated risks across security areas; and complete required security assessments. DOD concurred with 11 of 12 recommendations and partially concurred with one. GAO maintains that all recommendations are warranted.GAO developed the notional threat scenarios below to exemplify how publicly accessible information about DOD operations and its personnel introduces risks across multiple security areas.

Risk to Personnel and Their Families

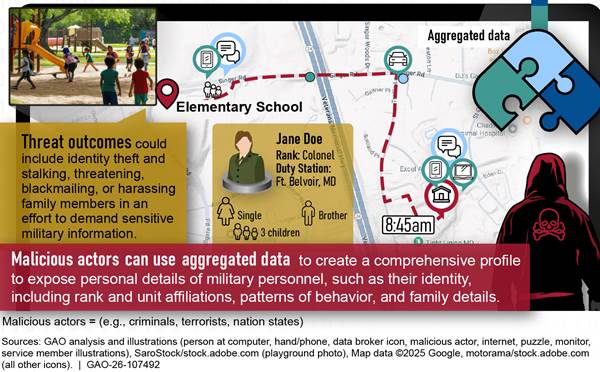

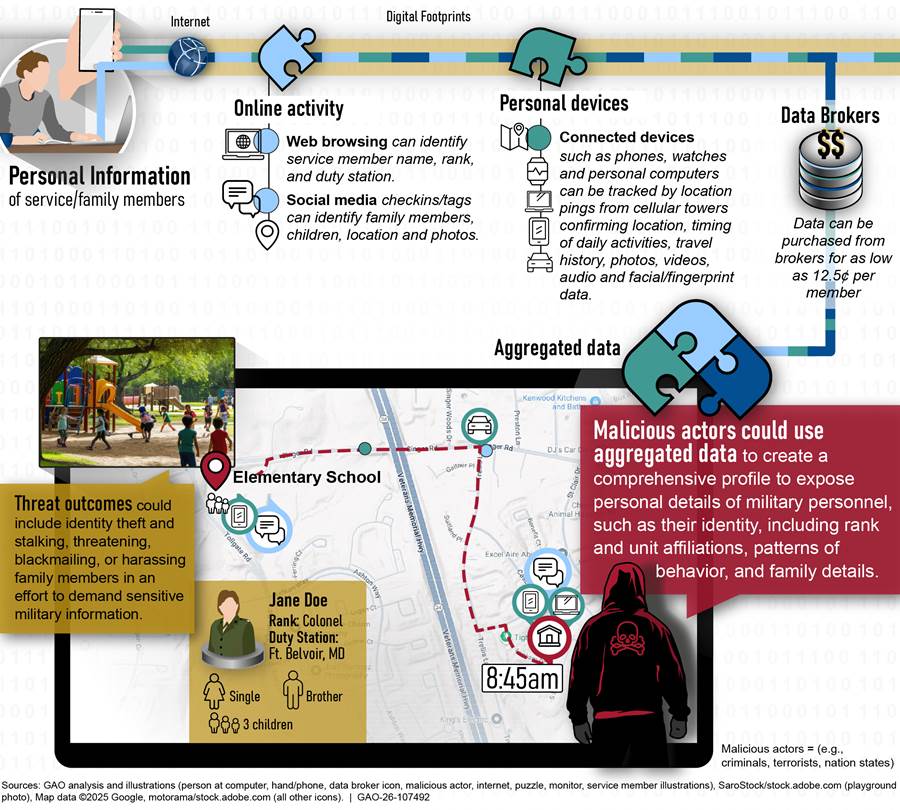

This scenario illustrates how a malicious actor could use digital information purchased from data brokers or collected from the web to identify and harm DOD personnel and their families.

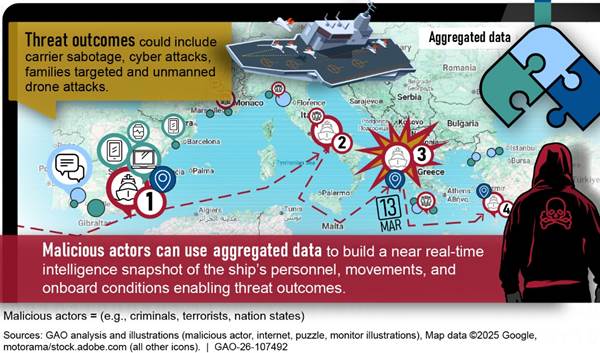

Risk to Operations

This scenario illustrates how a malicious actor could use digital information—including DOD press releases, news sources, online activity, social media posts, and ship coordinates—to project the route of a vessel and disrupt naval carrier operations. When aggregated, this information could enable targeting the vessel with uncrewed systems or sabotaging the ship while in port.

Figure: Digital Footprints Can Be Aggregated to

Disrupt Aircraft Carrier Operations

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

OPSE operations security

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

October 7, 2025

Congressional Committees

Today’s digital communication has transformed the once-popular military slogan “loose lips sink ships” into “loose tweets sink fleets.” The message that careless speech can undermine national security remains especially applicable in the age when we are compelled to have a digital identity. Massive amounts of traceable data about military personnel now exist due to the proliferation of personal and government devices and the resulting widespread availability of digital information. In addition, defense platforms (e.g., weapon platforms, connected devices, sensors, training facilities, test ranges, and business systems) depending on wireless technology can generate tremendous amounts of data.

Advances in technology have made the accessibility to this information easier and more efficient. Specifically, data generated by personnel and defense platforms—also known as digital footprints—can be gained through public websites, stolen and posted on the dark web, or acquired and sold by data brokers from anywhere in the world.[1] These digital footprints, when aggregated into a digital profile, can threaten military operations; the privacy and personal safety of service members, civilian employees, contractors, and family members; and ultimately our national security.

Over the years, congressional testimonies, reports, and news articles have identified concerns about the risks of information about national security personnel and operations in the public sphere. For example, in January 2025, the nominee for Director of the Central Intelligence Agency told the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that remote surveillance (also known as ubiquitous technical surveillance) is presenting unprecedented challenges to the Central Intelligence Agency’s ability to collect human intelligence.[2] In the last few years, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued an unclassified report and fact sheet highlighting the risks associated with commercially available information—that is, any data or other information bought or sold by a company for commercial purposes.[3]

Reports published by the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence highlight risks and vulnerabilities related to commercially available data.[4] In 2022, a Yale fellow testified about the risk posed to individuals in national security positions or in the military from data acquired on the open data market.[5] Similarly, a 2023 Duke University research study found that data brokers—companies that collect and resell information on individuals—pose a national security risk by compiling large, detailed datasets on U.S. military personnel and subsequently selling that data on the open market.[6] The study noted that adversaries with access to these datasets could use this information for coercion, reputational damage, and blackmail.

We have previously issued reports on risks and threats to national security attributed to emerging technology in the information environment (including 5G wireless technologies), Internet of Things devices (e.g., wearable fitness devices and smartphones), and technology tracking military aircraft.[7] For example, in 2017, we reported on challenges DOD faced due to Internet of Things technologies, security risks, and associated policy gaps.[8] In 2018, we reported how DOD and the Federal Aviation Administration had identified security and mission risks stemming from information broadcasted by Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast Out technology, among other things.[9] In 2022, we reported how the modern escalation in the volume and interconnectedness of data had changed the landscape of information and national security.[10] DOD took actions to address our recommendations in these reports, such as signing a memorandum of agreement with the Federal Aviation Administration to jointly address aircraft position reporting.

A Senate report accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 and the conference report accompanying the Act include provisions that we review and assess DOD’s efforts to mitigate the national security risks and threats stemming from the digital footprint of DOD personnel; and assess DOD components’ efforts to protect personal information of its personnel from exploitation by foreign adversaries, respectively.[11] This report (1) describes the security, privacy, and safety risks of publicly accessible data about DOD personnel and operations; and assesses the extent to which (2) the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) has taken action to reduce associated risks to DOD personnel and operations; and (3) DOD components have conducted training and assessments to reduce risks to DOD personnel and operations.

The scope of this review includes digital data that can be generated by and transmitted from disparate sources, such as personal and government devices; DOD personnel working in an official capacity (such as a military unit’s public affairs employee); and defense platforms that transmit information outside the DOD information network.

For the first objective, we reviewed literature that discussed the security implications of digital footprints, remote technical surveillance, and misuse of publicly accessible information. We interviewed officials from the DOD organizations listed below to gain an understanding of their technical responsibility for managing digital footprint data and to identify the risks and threats to DOD’s personnel and operations when digital data about DOD and its personnel become publicly accessible. We also conducted our own investigation to determine the accessibility of sensitive DOD-related information and assess associated risks to DOD’s personnel and operations stemming from the aggregation of publicly accessible digital data. We developed and examined notional threat scenarios that depict potential consequences stemming from the exploitation of publicly accessible digital data. We developed these scenarios based on analyses of literature research, interviews, and our own investigation. Officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security reviewed the scenarios and provided input on their plausibility and potential impact.

For both the second and third objectives, we identified common OSD and DOD component security responsibilities that could reduce risks generated from digital profiles. We reviewed DOD guidance for six select security disciplines and security-related functions (hereafter referred to in this report as “security areas”): counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, operations security (OPSEC), and critical program information protection (program protection). We excluded six security areas—cybersecurity, industrial security, information security, personnel security, physical security, and special access programs—because those security areas are primarily focused on protecting information within DOD’s network, while the scope of our review was focused on information that is publicly accessible.

For the second objective, we focused on five OSD offices. These include four OSD offices that oversee the security areas within the scope of our review: Offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, the DOD Chief Information Officer, and the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. We also included the Office of the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs since it is responsible for releasing DOD information to the public. To evaluate OSD’s actions, we requested and obtained current policies and guidance that OSD officials identified as relevant to the digital profile threat. We reviewed each document provided to assess whether it discussed the digital profile threat and its associated risks, and established any best practices to reduce risk (e.g., countermeasures or mitigations). We also interviewed officials from the Offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, and the DOD Chief Information Officer to discuss their efforts to coordinate and collaborate across other security areas.

For the third objective, we focused on a non-generalizable sample of 10 DOD components: all five military services, U.S. Cyber Command, U.S. Special Operations Command, National Security Agency, Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, and Defense Intelligence Agency.[12] In assessing these components’ efforts, we collected a non-generalizable sample of training and awareness documents and the most recent security assessments from select DOD components with security responsibilities. We reviewed these documents to assess whether they addressed security risks related to the digital profile. We also interviewed officials from the components to discuss ongoing actions to address and reduce risks relating to information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. Further details on our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to October 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Development of DOD and Personnel Digital Profiles

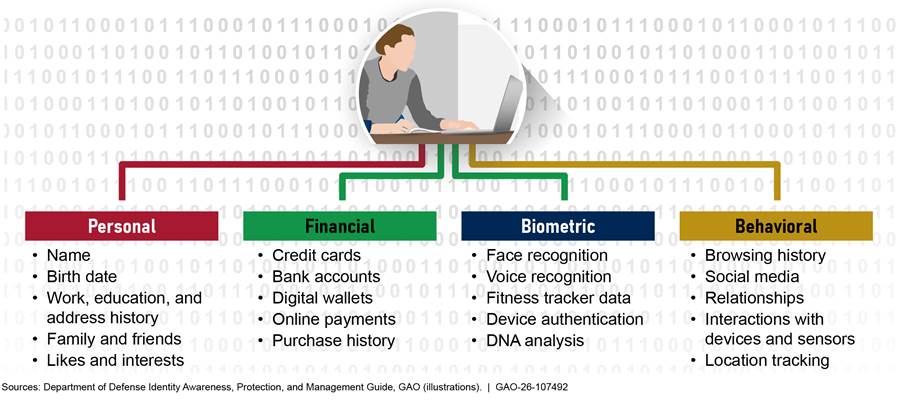

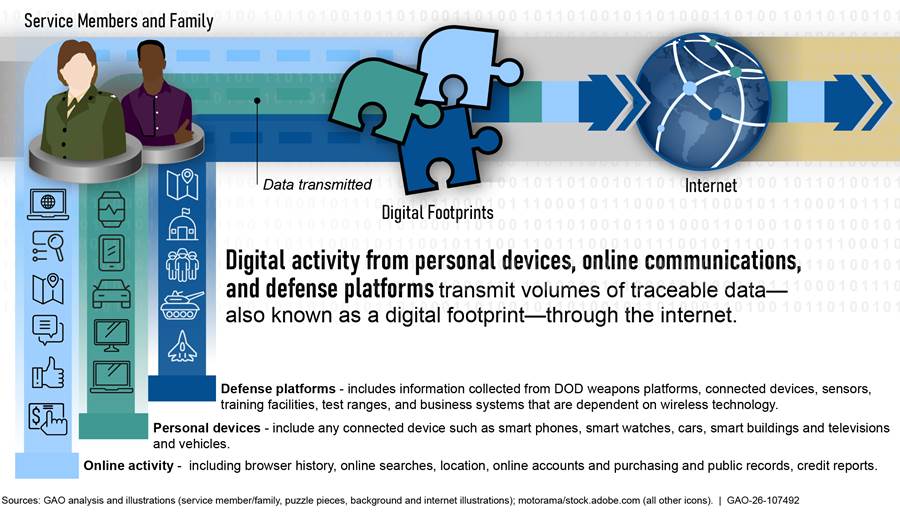

Throughout the day, people—including DOD service members, civilian employees, contractors, and family members— knowingly or unknowingly leave behind sensitive information through digital activity (see fig. 1).

Digital activity from military personnel using personal and government devices (e.g., computers, tablets, and phones) and interacting online with websites, search engines, applications, and software programs generate volumes of traceable data about them and potentially those in proximity. In addition, defense platforms (e.g., weapon platforms, connected devices, sensors, training facilities, test ranges, and business systems) depending on wireless technology can generate data. For example, ships, aircraft, and ground vehicles are equipped with technology that communicates traffic details such as routes, position, and speed. All this digital activity generates volumes of traceable data—also known as a digital footprint.

Digital footprints can be knowingly or unknowingly collected through a variety of technologies and transmitted through the internet. These technologies include cookies and permissions that track online behavior; telemetry technology that monitors precise locations (i.e., geolocation); sensing technology (e.g., Internet of Things sensors and wearables) that collect data from various environments and movements; and advertising technology that track and leverage geolocation data to create highly targeted, location-based advertising. Figure 2 depicts the typical data flow, beginning with the range of digital activities where digital footprints are generated and transmitted through the internet.

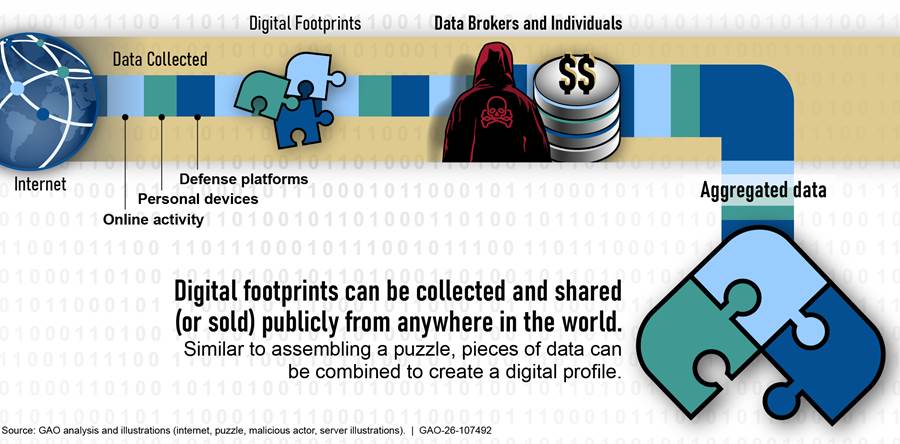

Once transmitted through the internet, digital footprints can be collected and shared (or sold) publicly from anywhere in the world. While a single footprint may seem insignificant (because that single data point is not considered sensitive or classified), when tied to other sources, multiple footprints can create a digital profile. This aggregation of information, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant, over time develops a detailed profile and can reveal potentially sensitive or classified information (i.e., actions, interests, and vulnerabilities) that was not initially apparent, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Digital Footprints Are Collected from the Internet and Can Be Aggregated into a Digital Profile

Emerging technological capabilities (such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data mining) have the potential to advance the continued aggregation and analysis of data on individuals’ personal and professional lives. These technologies enhance the speed, accuracy, and ability to predict behavior across large data sets, but they also introduce a number of risks to DOD. Those risks include counterintelligence, force protection, safety and security of family members, insider threat, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection.

DOD Responsibilities Relating to the Digital Profile

DOD has senior-levels officials within OSD that oversee various security areas:

· Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security establishes and oversees the implementation of policies and procedures for the conduct of DOD counterintelligence, insider threat, OPSEC, and program protection.[13]

· Under Secretary of Defense for Policy establishes and oversees the implementation of policies and procedures for DOD mission assurance and anti-terrorism, which includes force protection.[14]

· Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering establishes policies for development and approval of systems engineering plans and program protection plans, among other things. [15]

· Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs acts as the sole authority for releasing to news media representatives official DOD information and visual information materials, including press releases. DOD guidance states that information will be withheld only when disclosure would adversely affect national security, threaten the safety or privacy of service members, or if otherwise authorized by statute or regulation.[16]

· DOD Chief Information Officer develops the department’s cybersecurity policy and guidance.[17]

DOD components are responsible for implementing DOD issuances to protect information, personnel, equipment, and operations. More specifically:

· Military departments and DOD components conduct OPSEC assessments; delegate responsibilities for mission assurance assessments; and assess appropriate classification of critical program information. Additionally, military departments and DOD components are to provide training to educate their personnel.[18]

· Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency establishes security education, training, certification, and professional development programs.[19]

Defense Security Enterprise

The Defense Security Enterprise is a system of organizations, infrastructures, and measures (including policies, processes, procedures, and products) intended to safeguard DOD personnel, information, operations, resources, technologies, and facilities against harm, loss, or hostile acts and influences. This system comprises personnel, physical, industrial, information, and operations security, as well as special access program security policy, critical program protection, and security training. The Defense Security Enterprise framework must align with and be informed by other DOD security-related functions such as counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, and mission assurance.[20]

|

Counterintelligence: Information gathered and activities conducted to identify, deceive, exploit, disrupt, or protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage, or assassinations conducted for or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations or persons or their agents, or international terrorist organizations or activities. Force protection: Preventive measures taken to mitigate hostile actions against Department of Defense (DOD) personnel (including family members), resources, facilities, and critical information. Insider threat: A threat presented by a person who has, or once had, authorized access to information, a facility, a network, a person, or a resource of DOD and knowingly or unknowingly commits an act in contravention of law or policy that resulted in or might result in harm through the loss or degradation of government or company information, resources, or capabilities, or a destructive act, which may include physical harm to oneself or another. Mission assurance: A process to protect or ensure the continued function and resilience of capabilities and assets, including personnel, equipment, facilities, networks, information and information systems, infrastructure, and supply chains critical to the execution of DOD mission-essential functions in any operating environment or condition. Operations security: An activity that identifies and controls critical information and indicators of friendly force actions. Critical program information protection: U.S. capability elements that contribute to the warfighters’ technical advantage, which if compromised, undermines U.S. military preeminence. U.S. capability elements may include software algorithms and specific hardware residing on the system, its training equipment, or maintenance support equipment. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documents. | GAO‑26‑107492

DOD has established policies, procedures, and guidance to help defend mission-critical security areas—such as DOD Directive 5200.43, Management of the Defense Security Enterprise.[21] Among other things, this directive establishes the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee. This committee is to provide interdisciplinary perspectives to strengthen the department’s security posture through strategic administration and policy coordination. Specifically, is to advise the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security on security and training; provide recommendations on key policy decisions and on opportunities for standardization and improved effectiveness and efficiency; and facilitate coordination of policies across security areas, among other things.[22]

This cross-functional governance body is chaired by the Defense Security Executive—the official under the authority, direction, and control of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. The committee includes stakeholders from across the department— the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, DOD Chief Information Officer, and DOD General Counsel.

Public Accessibility of Digital Data Poses Security, Privacy, and Safety Risks to DOD Personnel and Operations

Malicious Actors Can Exploit Data Through Various Digital Activities

DOD officials and documents identify the public accessibility of digital data as a real and growing threat that poses risks to personnel privacy and safety, mission success, and national security. According to officials from the OSD offices and the select DOD components we interviewed, digital footprint data or an aggregated digital profile poses risks to the privacy and safety of service members and their family members.[23] For example, in June 2021, a senior DOD official testified that digital footprints could pose a risk to new recruits who may later serve in sensitive or covert roles by exposing their identities, thus compromising broader counterintelligence and surveillance efforts.[24] Similarly, a National Security Agency official told us that the digital footprint and the potential for an aggregated digital profile creates vulnerability in the “cog of the machine.” The official expressed that if the cog (i.e., personnel) is vulnerable, the mission will also be vulnerable.

According to DOD guidance, this risk can be attributed to the rapid advancement and global use of communications systems and information technology, easily obtainable technical collection tools, and growing use of the internet and various social and mass media outlets.[25] While DOD can provide guidance on how to limit the amount and type of information that is transmitted to the public (as discussed later in the report), DOD has limited control over the extent to which others—including data brokers and malicious actors—collect, use, and exploit this information.

· Data brokers collect, aggregate, and sell personal information on individuals to third parties for the purposes of marketing, advertising, law enforcement, enterprise security, criminal justice, and recruitment, among other areas. According to a U.S. Cyber Command briefing, the activities of third-party data brokers have real-world implications for foreign intelligence gathering, targeted phishing attacks of military personnel, stalking, and harassment, among other things. In April 2023, a Duke University researcher testified that data brokers threatened U.S. national security and noted that their research team was able to purchase personally identifiable information on military service members from data brokers for as low as 12.5 cents per member.[26] The threat of a malicious actor exploiting these data poses privacy, security, and safety risks to DOD personnel—including family members. In January 2025, the Department of Justice issued a final rule to implement an executive order that prohibits and restricts certain data transactions of bulk sensitive personal data and government-related data with certain countries or persons due to national security risks.[27] According to officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, this order will not, however, restrict the collection or sale of data domestically or internationally to foreign entities not associated with countries of concern.

· Malicious actors (e.g., adversaries, such as hostile nation-states and terrorists or criminals) can leverage digital profile data over time as intelligence to establish patterns or better understand military intent and capabilities.[28] For example, DOD’s joint doctrine on OPSEC describes how an adversary can quickly search multiple sources (e.g., social networking sites, geotags, website data) and derive indicators necessary to counter a mission or operation.[29] Similarly, a 2011 Defense Intelligence Agency report described how a military enthusiast used social media to share and discuss military personnel movements and operational locations, which revealed details of U.S. military air operations in Libya. This information could be exploited by an adversary.

Notional Threat Scenarios Illustrate Risks Stemming from Public Accessibility of Digital Data

We developed notional threat scenarios that exemplify how the public accessibility of information about DOD operations and its personnel introduces risks across multiple security areas. We discuss risks in four areas—operations, military capabilities, personnel and their families, and leadership—along with illustrative information graphics.[30] Officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security agreed that our scenarios were both realistic and plausible, and that the aggregation of digital footprints could have significant security implications. They told us they have, in fact, seen family members targeted during deployments and acknowledged its adverse impact on mission. Further, they stated that digital profiles as presented in our scenarios have significant security implications for DOD’s mission and the physical safety of service members and their families.

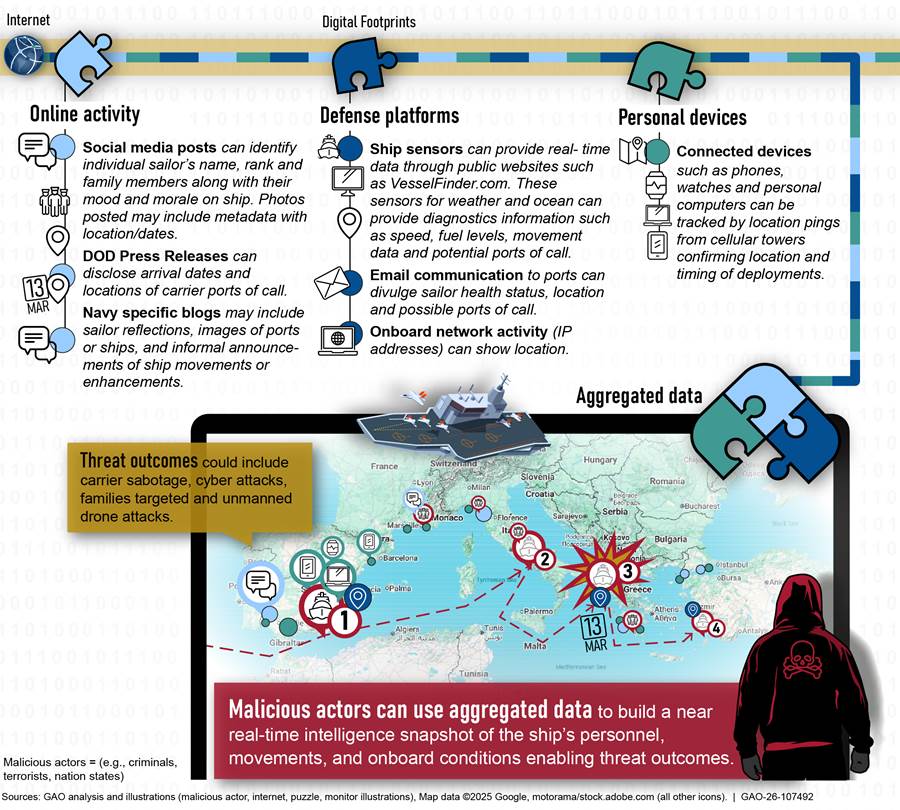

Risk to Operations

The first notional threat scenario, as shown in figure 4, illustrates how aggregated information—including DOD press releases, news sources, online activity, social media posts, and ship coordinates—could be used by malicious actors to disrupt naval carrier operations.

For example, a news article may publicly announce an aircraft carrier’s deployment and include the number of personnel aboard, the vessel’s capabilities, and the recent installation of commercial Wi-Fi for sailors. A subsequent press release issued by the Navy’s public affairs office may confirm the aircraft carrier’s arrival to and departure from scheduled ports. Such announcements could be supplemented by publicly accessible tracking data. Our investigators found real-time tracking information in online forums and posted coordinates from online fleet and marine tracking websites. We also found social networking support groups created by family members of deployed sailors sharing details about communications (i.e., photos and messages); several family members shared photos and posts about visiting the port and seeing their sailors during the holiday season. Further, a private social media group was identified in which the aircraft carrier’s public affairs team published petty officer promotions, including ranks and photos; information about aircraft assignments and strike groups; and the composition of squadrons.

Digital footprints, when aggregated, can form a comprehensive profile that adversaries may exploit to disrupt carrier operations and target personnel and their families through social engineering. For example, malicious actors could link sailors to their immediate family members from social media posts. Once this relationship is established, the malicious actor could begin compiling additional photos and information that may provide deeper insights, such as the exact location based on the geolocation or metadata, that may lead to a personal residence and behavioral patterns (e.g., the number of times or frequency of performing a particular activity).

This type of information creates the potential for blackmail or coercive tactics. For example, individuals may be stalked, threatened, or harassed in exchange for military information. Additionally, a malicious actor could use information on the ship’s movements from official press releases in combination with a real-time ship tracking website to project the route of the vessel. This could enable the vessel to be targeted by uncrewed systems or sabotaged while docked. This type of profiling introduces risks across multiple security and privacy areas, including force protection, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection.

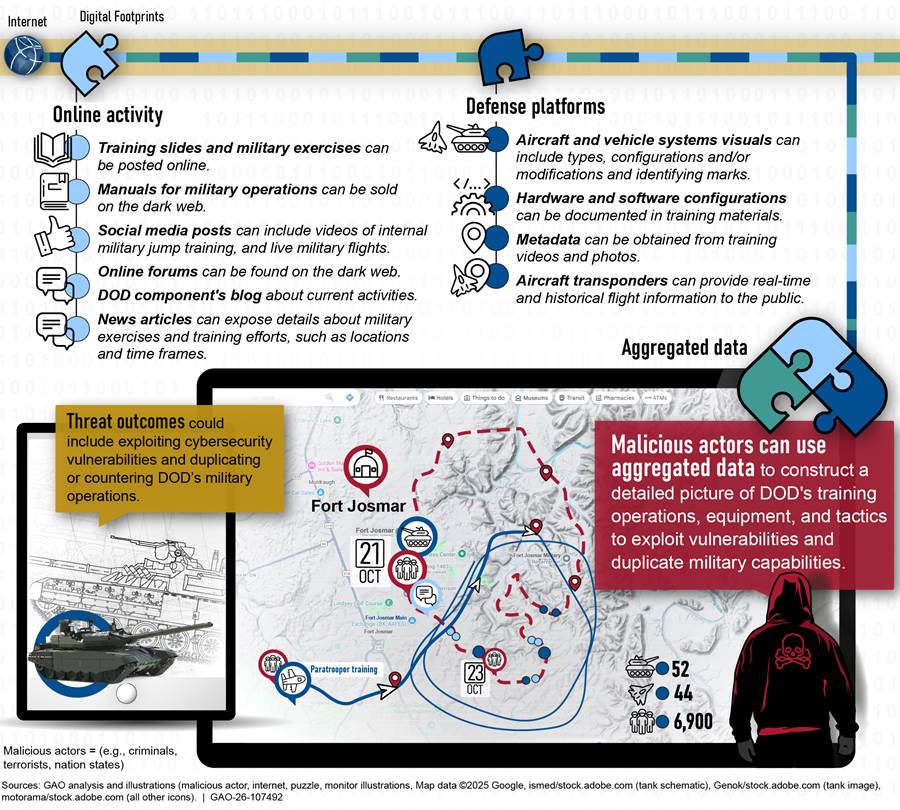

Risk to Military Capabilities

The second notional threat scenario, as shown in figure 5, illustrates how aggregated information could expose DOD-related training materials and military capabilities.

Figure 5: Notional Digital Profile Threat Scenario Exposing DOD-Related Training Materials and Military Capabilities

Sensitive information about military personnel and operations can be found online across multiple social media sites, news articles, and online forums on the surface and dark web. In 2018, cybersecurity researchers identified hacker information on the dark web for sale that included sensitive military data: course books and military personnel related to a piece of military equipment, military manuals on tank platoon operations, and improvised explosive device training. Furthermore, our investigators found photos of a military facility’s training slides posted in an online military forum. The training slides included information about a prior international military exercise that revealed strategic partnerships. Additionally, a social media post depicted posts and videos of an internal military jump training, including live military flights, internal views of military aircraft, as well as equipment used by paratroopers. Based on the photos of the equipment, the applicable user manuals could be purchased from the dark web.

These digital footprints, when aggregated, create a comprehensive profile that a malicious actor could exploit to undermine DOD military operations. For example, a malicious actor could leverage information about military equipment (including hardware and software systems) from training materials, internal aircraft layouts, and photos from training exercises. Specifically, photos may reveal equipment or aircraft modifications, and the accompanying manual may provide detailed instructions on how to apply the modification or perform maintenance. A malicious actor could use this information to clone products, duplicate military capabilities, or identify and exploit vulnerabilities. Similarly, photos of the paratrooper in the international military exercise may reveal unique markings that could be critical indicators of overall combined military planning and operations. This type of profiling introduces risks across multiple security and privacy areas, including force protection, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection.

Risk to Personnel and Their Families

As referenced previously, according to a 2023 Duke research study, personally identifiable information on military service members from data brokers could be purchased for as low as 12.5 cents per member. These data may include information such as names, ranks, unit affiliations, and family details to identify individuals involved in sensitive operations.[31] Our investigation found that data brokers were selling alleged personal details (e.g., title, name, personal emails, and phone numbers) of service members across surface, deep, and dark web platforms.

|

Surface web is the portion of the internet that is easily accessible and searchable. Examples include social media platforms, online forums and blogs, business websites, and public databases. Deep web is the portion of the internet that is accessible but not easily searchable. These websites cannot be indexed by search engines. Examples include databases, academic journals, login-protected websites, private networks, and personal social media accounts. Dark web is the portion of the internet that is hidden. The dark web can only be accessed using specialized software and is not searchable. It is where the internet’s illegal activities reside. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑26‑107492

The third notional threat scenario, as shown in figure 6, illustrates how aggregated information purchased from data brokers or collected from the web could be used to identify and harm DOD personnel and their families.

For example, our investigators found a DOD public affairs office’s press release that identified and pictured a service member who completed urban sniper training. Using this identifier, the service member’s data could be purchased on the dark web and include identifiable contact information, demographic details, rank, and unit affiliation. With contact information, additional research could be conducted to identify family associations, such as the names of parents, siblings, spouses, and even children. Using an identifier contained in a DOD public affairs office’s press release, our investigators identified photos of family members and the service member’s date of birth.

These digital footprints, when aggregated, create a comprehensive profile that adversaries could exploit to harm DOD personnel and their families. Specifically, a malicious actor could use this information to stalk, threaten, and harass the service member or their family members to obtain sensitive military information. Beyond that, a malicious actor could use information about school locations and after-school activities to target the service member’s child when they are most vulnerable, using details about the family to gain trust and potentially abduct the child. This level of surveillance of a loved one could be leveraged to exploit that service member, undermine their credibility among subordinates, and gather additional intelligence to disrupt military operations. This type of profiling introduces risks across multiple security and privacy areas, including force protection, insider threat, and OPSEC.

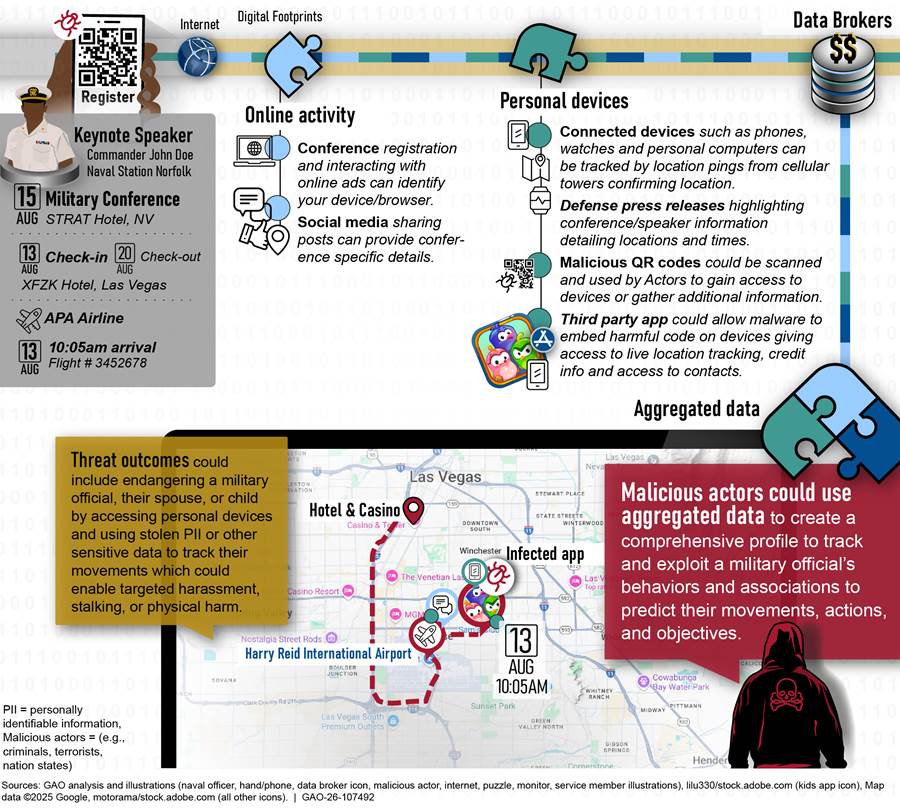

Risk to Leadership

The fourth notional threat scenario illustrates how aggregated information could be used to reveal a military official’s daily routines and relationships to predict their future actions and endanger military leadership. This scenario centers around a military conference. It highlights how various digital footprints, such as travel details, the presence of family members, interactions with other military personnel, public announcements, and the use of mobile applications, can be used to form a comprehensive digital profile of the official. (see fig. 7)

For example, a press release issued by the Navy’s public affairs team announces that a military official will serve as the keynote speaker at a high-profile military conference focused on emerging technologies and strategic planning. The release includes their name and title, and the conference location and dates. Upon arrival at the conference venue, the official engages with a socially engineered QR-code for conference registration and uses a digital wallet to pay for parking. Additionally, the official’s spouse confirms arrival to the conference by sharing a photo on social media with their child from the hotel lobby that includes other military panelists in the background. Before the trip, the official downloaded on their phone an unverified third-party mobile gaming application for their child to use during travel and while the official attended the conference. However, the application had extensive permissions and was able to access sensitive information and functions on the official’s phone, including location, credit card, contacts, camera and microphone, SMS messages, storage, and network access.

These digital footprints, when aggregated, create a comprehensive profile that adversaries could exploit to track the senior official’s behaviors and associations to predict their movements, actions, and objectives. Specifically, the press release identifies the official as high-profile. When combined with access permissions from the third-party gaming application, this could reveal the official’s associations and contacts. Further, the official’s daily routine may be known—including behavioral patterns (e.g., routine coffee stops), travel history, routes taken, and time spent in an area.

In addition, the QR code could direct the official to a fraudulent website that could steal personal or financial information or install malware that embeds harmful code on their phone. This can allow a malicious actor to gain unauthorized access and collect the official’s personally identifiable information, nonpublic DOD information not approved for public release, and other sensitive data, all without the official’s consent or knowledge. Further, the spouse’s social media check-in and photo includes geolocation data that reveals the real-time location of the family. A malicious actor could use this combined pool of information to inflict physical harm on the official or the spouse and child to gain further intelligence. This type of profiling introduces risks across multiple security and privacy areas, including counterintelligence, insider threat, mission assurance, and OPSEC.

OSD Has Not Fully Taken Action to Reduce Risks of Publicly Accessible Digital Data

As presented in our scenarios above, digital profile risks could compromise critical information, jeopardize the mission and safety of DOD personnel, and ultimately undermine DOD’s ability to achieve its overall mission to defend and protect the United States—including its operational and tactical goals. DOD guidance generally requires OSD offices to manage the six select security areas by issuing policy and guidance; and coordinating and collaborating with each other on security matters. However, OSD has not consistently issued policies and guidance to address the digital profile threat. Furthermore, OSD has limited coordination and collaboration across the existing security areas—specifically, counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection—to reduce risks from the digital profile.

OSD Has Issued Policies and Guidance to Address Digital Profile Risks to Varying Degrees

DOD guidance generally requires OSD offices to develop policies and prescribe guidance that implement procedures, integrate strategies, and provide oversight of security areas.

Three of the five OSD offices we reviewed issued policies or guidance to address the risks of information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible to varying degrees. Specifically, the Offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, DOD Chief Information Officer, and Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs have issued policies or guidance focused on two types of digital profile threats—digital ecosystems (i.e., applications, websites, or devices with data collection capabilities) and social networking.

· Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security issued a policy providing digital personal protection and protective intelligence measures as necessary if potential access and exploitation of accessible information threaten the security of an official designated as high-risk personnel and the performance of their official duties.[32]

· DOD Chief Information Officer issued a policy prohibiting military personnel, civilian employees, and contractors from using personal email or other nonofficial accounts to exchange official information.[33]

· Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs issued a policy providing core principles and guidance on social media use, along with guidance for social media records management.[34]

However, gaps remain in how DOD’s policies and guidance address security risks associated with the public accessibility of digital information about DOD and its personnel. Specifically, these policies and guidance are narrowly focused (i.e., do not fully address the range of potential risks from digital information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible), do not include all relevant stakeholders, and do not include all relevant security areas.

· Policies and guidance are narrowly focused. Some existing policies and guidance are narrowly focused and thereby do not fully address the range of potential risks from digital information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. For example, DOD Instruction 8170.01, Online Information Management and Electronic Messaging, issued by DOD Chief Information Officer, establishes policy and procedures for online information management and electronic messaging.[35] However, the instruction does not establish a policy or instruct its components or personnel to implement any security procedures that address the risk from digital ecosystems (i.e., applications, websites, or devices with data collection capabilities); threats to identity; or defense platforms.

Similarly, the DOD Chief Information Officer issued a memorandum that prohibits the use of personal email accounts, messaging systems, or other nonpublic DOD information systems in conducting official business involving controlled unclassified information.[36] The memorandum provides direction on the requirements and proper safeguards for the use of mobile applications on unclassified government-owned devices (e.g., smartphones or tablets). However, the memorandum does not address the use of personal email accounts or messaging systems on personal devices in conducting unofficial business involving unclassified information—such as official travel hotel reservations, military travel orders, or social media—which could present comparable risks, if aggregated. As discussed earlier in this report, digital activity from personal and government devices (e.g., computers, tablets, and phones) and online communications generate volumes of traceable data about the military personnel and potentially about those in proximity. In addition, defense platforms depending on wireless technology can generate data, such as traffic details that provide routes, position, and speed.

· Policies do not include all relevant stakeholders. Existing policies related to the use of social media do not include or acknowledge the involvement of stakeholders responsible for privacy, safety, and security risks. Specifically, DOD Instruction 5400.17, Official Use of Social Media for Public Affairs Purposes, issued by the Office of the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, does not mention the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security.[37] However, the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security’s office is responsible for establishing and overseeing the implementation of policies and procedures for the conduct of OPSEC, among other things. According to DOD Directive 5205.02E, DOD Operations Security (OPSEC) Program, the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs is responsible for developing policy and guidance to ensure OPSEC is incorporated into Public Affairs’s process for releasing information.[38] As the authority on the release of information, Public Affairs is often the first line of defense in identifying the aggregation of risks when reviewing information for public release. However, an OPSEC program manager would determine how to reduce the risk of aggregation, thus creating the need for coordination and collaboration.

· Policies and guidance do not include all relevant security areas. Two OSD offices that have policy and oversight responsibilities associated with security areas had not issued policy or guidance addressing security risks associated with the public accessibility of digital information about DOD and its personnel. Specifically, the Offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (responsible for force protection and mission assurance) and the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (responsible for program protection) do not have any policies or guidance that identify actions DOD personnel should take to reduce risks associated with the public accessibility of digital information.

OSD Has Coordinated on Policies and Guidance but Not Fully Collaborated to Address Digital Profile Risks

DOD guidance generally requires OSD offices to coordinate on policy and guidance development and to collaborate with each other on security matters through working groups or security forums.

According to officials from the OSD offices, the five OSD offices we reviewed coordinated with one another when they developed and issued policies and guidance addressing the digital profile threat. For example, the Offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security and DOD Chief Information Officer coordinated to issue guidance on the use of geolocation-capable devices, applications, and services. According to OSD officials, they coordinated on the policy and guidance by sending draft copies to other OSD and DOD components for review.

However, OSD offices have not collaborated to address risks associated with the digital profile—such as through working groups. When we spoke to OSD officials about efforts to reduce risks associated with the digital profile, they often deferred responsibility to other organizations and cited a lack of equity in the issue. For example, a mission assurance official from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy did not understand how digital footprints could pose some vulnerability that could rise to the level of mission failure. The official thus deferred responsibility to the Office of the DOD Chief Information Officer. However, as shown earlier in the report, publicly accessible data that are aggregated can identify mission assurance-related risks. When we discussed this topic with an official from the Office of the DOD Chief Information Officer, the official in turn deferred responsibility to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. OSD officials acknowledged the need for a coherent risk management approach for the digital environment but stated that the department has deferred risk mitigation of the digital profile threat to the unit level—such as to a commanding officer preparing for a ship’s departure.

OSD Needs to Leverage the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee to Reduce Risks

OSD officials acknowledged that the policies and guidance related to the digital profile threat do not fully address the range of potential risks of digital information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. The officials stated they believe the department has limited authority to issue policy that controls the actions of DOD personnel and contractors outside of an operational area. The officials also acknowledged that while they had coordinated to review existing policies and guidance, they had not collaborated to address digital profile risks because they did not believe the digital profile threat and its associated risks aligned with the Secretary of Defense’s priorities that were established in January 2025. The priorities focus on reviving the warrior ethos, restoring trust in the military, rebuilding military capabilities, and reestablishing deterrence by defending the homeland. However, OSD officials had not taken needed action to reduce risks of digital information before these priorities were established.

Recognizing that uncertainty can exist with evolving security risks, we asked OSD officials whether the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee had performed any review or assessment of existing security policies and guidance to identify gaps associated with risks in the digital environment. According to an official from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, the executive committee meets quarterly but has not discussed the digital profile as a risk. Instead, the executive committee has been mostly focused on Trusted Workforce, an initiative to modernize U.S. government personnel vetting processes.

As discussed earlier in the report, the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee—a cross-functional governance body that includes stakeholders from across the department, including the General Counsel—is responsible for providing recommendations to the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security on key policy decisions and on opportunities for standardization and improved effectiveness and efficiency; and for facilitating cross-functional security policy coordination.[39] Specifically, the executive committee can commission reviews and in-depth studies of security issues and make recommendations for developing or improving policies, processes, procedures, and products to address pervasive, enduring, or emerging security challenges, such as those associated with risks in the digital environment.

In addition to conducting in-depth studies of security issues and making recommendations for developing or improving policies, the Defense Security Enterprise Strategy states that the executive committee should collaborate across traditional organizational boundaries to establish and measure Defense Security Enterprise strategic direction and provide cross-discipline perspectives to strengthen the department’s security posture.[40] The strategy also states,

In the face of evolving challenges, the Defense Security Enterprise must establish and implement a robust security framework to enable cooperation and collaboration across the enterprise. The Defense Security Enterprise must improve and elevate the security culture within the department and posture to maintain strategic and operational dominance against dynamic threats.

As a cross-functional governance body that includes stakeholders from across the department, including the General Counsel, the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee is well-positioned to lead an assessment with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs and OSD officials who oversee security areas that could be impacted by digital profiles. Until DOD leverages the Defense Security Enterprise’s Executive Committee to assess DOD’s existing security policies and guidance on the digital profile threat and recommend any appropriate updates to policy and guidance, the department will have difficulty in determining whether risks are being sufficiently managed within the boundaries of their legal authorities.

DOD Components’ Actions for Reducing Risks of Public Accessibility of Digital Data Are Inconsistent

Most of the 10 DOD components we selected for our review raise awareness of and administer training on the digital profile and its associated risks.[41] However, this training does not consistently cover threats associated with digital profiles in security areas other than OPSEC. Furthermore, DOD components we reviewed have not consistently conducted assessments associated with the risks.

Most DOD Components Raise Awareness of Digital Profile Risks Through Multiple Efforts

In addition to formal training, seven of the 10 select components we reviewed provided examples of efforts to raise awareness about the digital profile and its associated risks, although awareness efforts are not required. In reviewing these examples, we found 59 percent (33 of 56) of the examples incorporated digital profile content by acknowledging the risks of digital information in the public, highlighting methods to counter digital profile risks, or a combination of the two. These awareness campaigns used posters, emails, and smart cards, among other things, as communication channels. For example, DOD issued an Identity Awareness, Protection, and Management Guide to help readers understand how to keep their identities private and secure online.[42] This collection of smart cards provide the tools, recommendations, and series of steps for implementing settings that maximize an individual’s security in a variety of digital sources, such as Facebook, fitness trackers, online dating services, and smartphones (see fig. 8).

Additionally, DOD components have taken the following actions to understand and inform others about security risks associated with digital data in the public:

· Identity management programs. Some DOD components have begun creating identity management programs that protect the identities of certain personnel. For example, officials in an Army Counterintelligence Command told us the command has restructured their OPSEC and counterintelligence offices into a singular identity management program to enhance collaboration across teams as they manage risks posed by the digital profile threat.

· Research efforts. The Army Threat Systems Management Office has performed threat experiments that relate to the digital footprint. An official from this office told us these experiments led to the creation of teams assessing digital profiles for critical installations, missions, and programs/technologies. Specifically, the Threat Systems Management Office provides digital profiling services for Army units by request. The official described how a threat OPSEC team is using public information, commercial information, and data analysis tools to understand the digital signatures and profiles of Army units and programs. Similarly, the official stated the office’s supply chain team focuses on reducing risk and vulnerabilities posed by public or commercial supply chain information that a malicious actor may target or collect for future exploitation.

· Family readiness efforts. DOD officials acknowledge the role of families in supporting OPSEC. As discussed earlier in our scenarios, malicious actors can target families to obtain sensitive military information about service members. For this reason, the military services have established family readiness groups, which are responsible for hosting outreach events and providing resources to educate families on OPSEC and the security implications of their digital activities. For example, the Marine Corps, U.S. Special Operations Command, and Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency have developed guidance and training that incorporate best practices for identity management to educate family members on practicing good social media habits and on protecting themselves against threats to their identity.

Most DOD Components Administer Training on Digital Profile Risks Primarily Related to Operations Security

DOD guidance requires DOD components to develop and administer training on OPSEC, counterintelligence, and insider threat. DOD guidance on mission assurance, anti-terrorism/force protection and program protection also address training for certain personnel or under certain circumstances.[43]

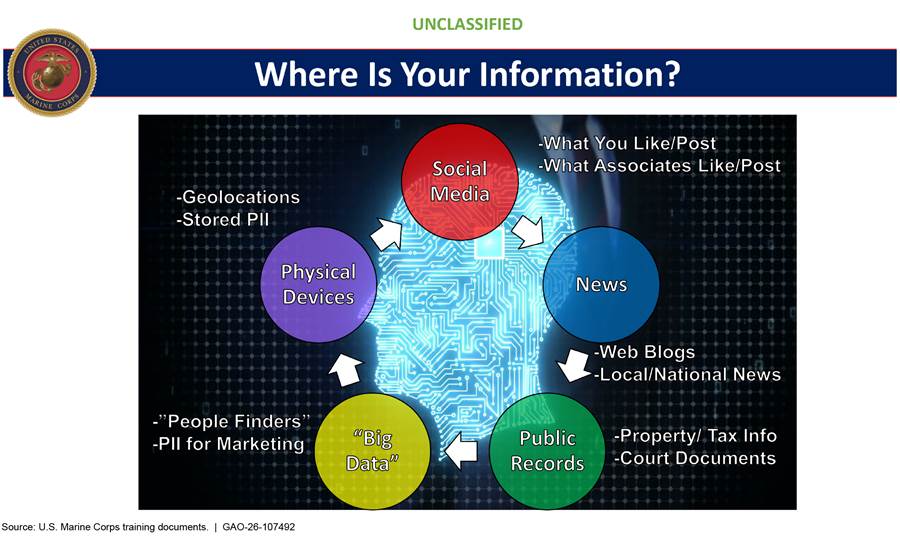

Nine of the 10 select components provided evidence of the security training they offered to personnel in the areas of counterintelligence, force protection, mission assurance, and OPSEC. Specifically, 67 percent (24 of 36) of training documents provided to us included content on the digital profile; its associated risks, such as digital ecosystems (i.e., applications, websites, or devices with data collection capabilities), social networking services, social engineering scams, and information collected from defense platforms; and best practices for countering risks. For example:

· The Marine Corps’s OPSEC training highlights the various places and ways by which a service member’s information can exist, including public records, personal devices, and social networking sites, among other things (see fig. 9).

· U.S. Special Operations Command provides a digital force protection training course to help personnel manage their online identities and personas, among other things. This course provides guidance on securing personal communications and devices, including local, network, email, and mobile phone security (see fig. 10).

· The Defense Information Systems Agency offers a cyber awareness course to DOD personnel.[44] This DOD-wide training provides an overview of current cybersecurity threats and best practices to keep information and information systems secure at home and at work. The training also identifies best practices for protecting personally identifiable information, among other things.

· The Defense Intelligence Agency’s Joint Counterintelligence Training Academy offers a course on understanding remote surveillance (also known as ubiquitous technical surveillance) and how the five pathways of collection (see text box) integrate to pose a threat to intelligence activities. This course is available to DOD counterintelligence personnel.

|

Ubiquitous technical surveillance is the collection and long-term storage of data in order to analyze and connect individuals with other people, activities, and organizations. Ubiquitous technical surveillance is organized into five pathways of collection: · Online (e.g., internet searches and websites) · Electronic (e.g., Bluetooth connections, GPS information, and smart devices) · Financial (e.g., banking applications and tap to pay) · Visual-physical (e.g., CCTV cameras and smart doorbell) · Travel (e.g., flight itineraries and GPS location searches) |

Source: International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development. | GAO‑26‑107492

· The Army Threat Systems Management Office offers a course on the protection of critical information, such as sensitive technology, installation and infrastructure, operations, and missions. This course is available to DOD program protection personnel, signature management professionals, and OPSEC practitioners.

· The Center for Development of Security Excellence offers seven security training courses that specifically address topics relevant to the digital profile threat to DOD personnel and contractors through a variety of learning formats, including self-paced internet learning and instructor-led learning (in person or virtually).

While most components we reviewed administer training, this training does not consistently cover threats associated with digital profiles in security areas other than OPSEC. Specifically, 80 percent (19 of 24) of training documents that addressed the digital profile represented OPSEC, based on our analysis of the evidence of security training provided by nine of the 10 select components. The other 20 percent represented counterintelligence and force protection. For example, DOD’s Level I Antiterrorism/Force Protection training discusses the risks presented by the public accessibility of digital information—including information intentionally shared—which could unintentionally provide valuable information to a terrorist planning an attack.[45] DOD components did not provide training examples that addressed the digital profile for insider threat or program protection.

DOD components are relying primarily on OPSEC training to address digital profile risks because OSD officials responsible for other security areas have not recognized the digital profile as a threat. Specifically, the OSD officials with security responsibilities stated that it was not their responsibility to reduce risk associated with the digital profile. As a result, OSD officials responsible for security areas other than OPSEC have not ensured that training had been updated to inform and educate the DOD workforce about these risks. As discussed earlier in this report, digital profiling introduces risks beyond OPSEC and has implications across the security areas, including counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, and program protection. OSD officials agreed and told us that DOD components cannot rely solely on OPSEC to reduce risks presented by the public accessibility of digital information.

DOD Directive 5200.43, Management of the Defense Security Enterprise requires the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee to advise the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security, as the Defense Senior Security Official, on security policy and training.[46] In addition, the committee is responsible for providing recommendations on key policy decisions and on opportunities for standardization and improved effectiveness and efficiency; and facilitating cross-functional security policy coordination.

However, the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee has not reviewed and assessed digital profile training to ensure that it is sufficiently represented in all security areas: counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection. By reviewing and assessing digital profile training across the security areas, the executive committee would be well-positioned to make any appropriate recommendations for improvement. Officials from the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security agreed the executive committee could be leveraged to support and facilitate accomplishing this type of review.

In 2018, the then-Director of National Intelligence acknowledged that education and awareness programs are the most important weapons in the cyber battlefield when it comes to personal devices and accounts.[47] Similarly, an official from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security emphasized that training and awareness programs likely will have a more effective impact than issuing policies. Until DOD takes action to ensure its personnel and contractors are trained on threats in the digital environment and associated risks of digital information in the public across all relevant security areas, DOD components will not fully understand the associated risks affecting personnel DOD-wide. Thereby, decreasing their ability to effectively reduce security and safety risks across the department.

However, one component—U.S. Cyber Command—did not provide evidence of having offered security training to its personnel in any of the security areas–counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection. According to a U.S. Cyber Command official, the command provides training and educational programs so that its personnel understand their role in OPSEC, are aware of any current intelligence threats, know the command’s critical information and indicators, and understand how to implement directed OPSEC measures and countermeasures. However, U.S. Cyber Command officials were unable to provide us evidence of this training or how it addresses risks associated with digital profiles. Until U.S. Cyber Command can demonstrate that it provides training to its workforce on threats in the digital environment and associated risks of digital information in the public across security areas, the command increases security, privacy, and safety risks.

Half of DOD Components Have Conducted Required Assessments of Security Risks

DOD guidance for four of the six security areas requires DOD components to conduct assessments: force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, and OPSEC.[48] These assessments enable DOD components to identify current or potential risks and vulnerabilities that would decrease the efficacy of that area’s mission. For example, according to DOD, a mission assurance assessment should examine, among other things, security risks related to infrastructure devices.[49] Similarly, DOD’s Manual 5205.02-M, Operations Security (OPSEC) Program Manual, states that an OPSEC assessment should examine the actual practices and procedures of an activity to determine if critical information may be inadvertently disclosed through the performance of normal organizational functions.[50]

Two of 10 components that we reviewed—the Marine Corps and U.S. Special Operations Command—conducted required assessments in all four areas. Both components provided evidence that they had conducted assessments that highlight risks associated with each of the four security areas—force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, and OPSEC. For example:

· U.S. Special Operations Command’s OPSEC team conducted an assessment in November 2024 that included activities to analyze publicly accessible information on helicopter technology production. This information could be used by adversaries to understand critical information about equipment capabilities.

· Marine Corps’s counterintelligence team assessed Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort in October 2024 and included activities to evaluate the organization’s ability to detect, deter, and deny insider threats, as well as threats to force protection and mission assurance. The assessment identified public affairs and social media as critical issues.

However, of the remaining eight components we reviewed, three components—Army, Air Force, and Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency—had conducted required assessments solely in the OPSEC area. For example:

· Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency’s OPSEC office conducted an OPSEC assessment of its headquarters from May 3 to July 23, 2021, to provide an overall evaluation of the organization’s OPSEC posture. The assessment recognized open-source intelligence as a general OPSEC threat. Specifically, the assessment stated that open-source intelligence can provide information on the organization’s dynamics, technical processes, and research activities.

· Department of the Air Force OPSEC Support Team conducted an external assessment, between October 2020 and January 2023, that included activities to analyze publicly accessible deployment information that could lead to forewarning a malicious actor of a pending deployment, among other things. The assessment included recommendations to protect future aircraft deployments.

DOD officials agreed that focusing assessment efforts solely on OPSEC overlooks the security risks of the public accessibility of digital data about DOD and its personnel posed to personnel privacy and safety, and national security. Furthermore, these components were unable to provide us evidence that they had completed the required security assessments in the remaining three areas—force protection, insider threat, and mission assurance.

In addition, of the remaining five components we reviewed, three components—U.S. Cyber Command, Defense Intelligence Agency, and National Security Agency—were unable to demonstrate that they conducted the required assessments. The remaining two components—Navy and Space Force—did not complete any of the four required assessments. Specifically, the Navy and Space Force told us they had not completed required assessments because of resource limitations. Although staffing and other resources may be constrained in these components, these assessments are required by DOD policy.

As previously discussed in this report, the aggregation of digital information can be used to determine behavioral patterns for targeting purposes. Although Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security officials did not believe the risks associated with digital footprints and ultimately digital profiles are unique to DOD, they acknowledged and agreed the potential risks posed by a malicious actor attempting to determine behavioral patterns for targeting purposes are greater for the department. Without conducting the required assessments in the four required security areas, DOD components increase the risk of not detecting vulnerabilities that malicious actors may exploit. For example, the components might not discover critical information—such as mission plans, geotagged photographs, and personnel data—that can be used by malicious actors for intelligence collection and exploitation is publicly accessible. These risks could compromise critical information, jeopardize the mission and safety of DOD personnel, and ultimately undermine DOD’s ability to achieve its overall mission to defend and protect the United States—including its operational and tactical goals.

Conclusions

In the age of digital dependency, the proliferation of devices, the prevalence of digital information, and a communications-oriented culture have led to individuals having a digital identity. The digital activity of DOD’s service members, contractors, and family members—from websites visited to emails sent to photos posted on social media—can generate volumes of traceable data that can threaten their privacy and safety, and ultimately our national security. These digital footprints represent a piece of a larger puzzle that, when tied to other sources, can create a digital profile and adversely affect military functions and missions.

DOD has identified the public accessibility of digital data as a real and growing threat to personnel privacy and safety, mission success, and national security. These risks could compromise critical information, jeopardize the mission and safety of DOD personnel, and ultimately undermine DOD’s ability to achieve its overall mission to defend and protect the United States—including its operational and tactical goals. While the department has taken actions related to a wide field of traditional security areas, its actions to reduce safety, security, privacy, and operational risks posed by the digital profile are limited. DOD could better safeguard information and indicators that malicious actors can weaponize to adversely affect operations or the privacy, safety, and security of personnel by assessing existing policies and guidance; collaborating to address security risks; administering training across all relevant security areas; and conducting required assessments of security risks. By implementing these actions, DOD could reduce risks and be better positioned in achieving its goal to protect its personnel, units, and operations and to carry out its missions effectively.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 12 recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee assesses existing departmental security policies and guidance to identify gaps associated with risks in the digital environment; and makes recommendations on updating policy and guidance to reduce the risks of digital information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. In conducting this assessment, the executive committee should include all OSD offices that oversee security areas and the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee improves collaboration across the department to reduce the risks of information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. Collaboration should include all OSD offices that oversee security areas and the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee reviews and assesses security training to ensure that digital profile issues are considered in all security areas—counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, OPSEC, and program protection—and makes any appropriate recommendations for action to improve the representation of digital profile threats in security training across the department. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that U.S. Cyber Command provides security training to its workforce on threats in the security areas of counterintelligence, insider threat, and OPSEC. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that the Air Force is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Army should ensure that the Army is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the U.S. Cyber Command is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, OPSEC, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Defense Intelligence Agency is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, OPSEC, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the National Security Agency is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, OPSEC, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Navy is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, OPSEC, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 11)

The Secretary of the Air Force should ensure that Space Force is conducting required assessments in the security areas of force protection, insider threat, OPSEC, and mission assurance. (Recommendation 12)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for their review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, DOD stated that it concurred with 11 of the 12 recommendations and partially concurred with the remaining one.

For the 11 recommendations with which it concurred, DOD identified initial actions to address them. Specifically, DOD plans to:

· Leverage the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee to (1) facilitate collaboration across the Department to mitigate the risks related to DOD information becoming publicly accessible; and (2) review and assess applicable security training to ensure relevance and effectiveness. (Recommendations 2 and 3); and

· Ensure the DOD components are conducting appropriate security assessments and training. (Recommendations 4 through 12)

By implementing these actions, DOD could reduce risks and be better positioned in achieving its goal to protect its personnel, units, and operations and to carry out its missions effectively. We will continue to monitor the agency’s efforts in implementing our recommendations.

DOD partially concurred with our remaining recommendation. This recommendation calls for the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee to assess existing departmental security policies and guidance to identify gaps associated with risks in the digital environment and make recommendations on updating policy and guidance to reduce the risks of digital information about DOD and its personnel being publicly accessible. In conducting this assessment, the executive committee should include all OSD offices that oversee security areas and the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs.

In its written comments, DOD stated the existing policies are aimed at safeguarding official DOD data and communications within the scope of the department’s operational control. However, DOD stated the department’s authority is limited when it comes to the personal activities of DOD personnel managing their personal information and online presence outside the scope of their official duties, from non-DOD controlled locations, using non-DOD devices and applications, or with non-DOD information.

We recognize that there is a spectrum of who releases information—ranging from information that DOD intentionally releases (e.g., an official DOD press release) to information that a spouse posts on their personal social media account. However, as we depicted in our scenarios, a malicious actor does not care who releases the data. Rather, malicious actors leverage any available data to facilitate their ability to do harm to personnel, equipment, missions, and readiness. That is why we did not limit our recommendation to just policy, but also included improvements to training and awareness campaigns. These efforts could foster a culture change among DOD personnel (and their families) regarding how they share information during their personal activities.