SERVICE MEMBER ABSENCES

Actions Needed to Improve Response Process

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Kristy E. Williams at WilliamsK@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Army, Navy, and Air Force have issued guidance to help facilitate command efforts to locate a service member who is deemed absent from their assigned duty location. However, the Marine Corps has not developed such guidance, as GAO recommended in 2022.

GAO analyzed Army, Navy, and Air Force guidance and identified the following gaps that could hinder efforts to locate absent service members and mitigate related risks.

· Response time frames. Service guidance outlines response time frames with varying levels of specificity, resulting in different interpretations among officials regarding how quickly certain actions should be initiated. For example, Army guidance includes detailed time frames for actions such as alerting law enforcement, whereas Navy and Air Force guidance does not.

· Mental health. Army, Navy, and Air Force officials GAO interviewed commonly observed a link between service member absences and mental health and said that locating service members often intersects with efforts to prevent self-harm. However, guidance inconsistently addresses the interconnected nature of mental health issues and service member absences, and how such considerations should inform the command’s response.

· Safety. Army, Navy, and Air Force officials identified potential safety issues that may arise while searching for an absent service member, especially if the service member is experiencing a mental health crisis or has access to a firearm. However, guidance does not address these safety issues, potentially subjecting the absent service member or those trying to locate them to unnecessary risk.

By addressing these gaps in guidance, the services can better position themselves to help prevent harm and save lives.

Some services’ guidance for commanders and the military criminal investigative organizations (MCIO) lacks clarity on whether and when to classify an absence as voluntary or involuntary, which can significantly affect the urgency and comprehensiveness of search efforts. For example, Army guidance for commanders requires them to presume the service member is potentially in danger and to presume the absence is most likely involuntary after 48 hours unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. However, Department of Defense (DOD)-wide guidance does not have a similar provision, nor do the other military services’ guidance. In another example, Air Force MCIO guidance requires investigators to treat all absences as involuntary in the first instance, while guidance for the Army and Navy MCIOs does not. By revising guidance, commands and MCIOs will have a more consistent approach to absences and further their goal of quickly and safely locating absent service members.

Why GAO Did This Study

When a service member is absent from their unit, it may not be immediately clear if the absence is voluntary—that is, deliberate on the part of the service member—or involuntary, meaning the service member may be in danger. A timely and well-coordinated response to a service member’s absence is critical to establishing the facts and helping to ensure their safe return, if possible.

House Report 118-125 includes a provision for GAO to review policies and procedures related to missing and absent service members. This report builds on GAO’s 2022 report on this topic and examines the extent to which DOD and the military services have clarified guidance for responding to incidents of absent service members, among other issues.

GAO reviewed DOD guidance on responding to service member absences. GAO also visited a nongeneralizable sample of eight military installations, two per military service; reviewed the processes for responding to service member absences; and interviewed officials responsible for responding to such absences.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations, including that DOD update guidance for responding to service member absences to initially treat service member absences as involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. DOD concurred with these recommendations.

Abbreviations

ASD(M&RA) Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve

Affairs

CID Army Criminal Investigation Division

DOD Department of Defense

DUSTWUN duty status-whereabouts unknown

MCIO military criminal investigative organization

NCIS Naval Criminal Investigative Service

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

OSI Air Force Office of Special Investigations

OUSD(P&R) Office of the Under

Secretary of Defense for Personnel

and Readiness

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 12, 2026

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

A service member may be unexpectedly absent from their unit for a variety of reasons, ranging from making a deliberate decision to abandon their military duties to having a mental health crisis, being ill or injured, or foul play. A timely and well-coordinated response to a service member’s absence is critical to establishing the facts and helping to ensure the service member’s safe return, if possible. After a series of high-profile incidents involving service members who went missing in a nonhostile setting (i.e., not within a conflict zone or as a result of terrorist activity) and were later found deceased, the Army commissioned independent and internal reviews that found weaknesses in its procedures for responding to such absences.[1] In response to these findings, the Army issued a new policy in 2020 outlining a series of steps commanders must take when a soldier goes missing to help determine if the absence was “voluntary,” meaning an intentional unauthorized absence or desertion, or “involuntary,” meaning one that is unintentional and possibly resulting from an accident or foul play.[2]

The Navy and the Air Force updated their policies in 2021.[3] However, we reported in 2022 that the Marine Corps had not developed policy in this area and recommended that it do so.[4] Our 2022 report also found that the military services did not regularly report information on the number of absences to the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and we recommended that OSD establish such a requirement. The Department of Defense (DOD) concurred with both recommendations, but as of February 3, 2026, had not implemented them.

House Report 118-125 accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to review policies and procedures with regards to missing and absent service members.[5] This report builds on our 2022 review and examines the extent to which OSD and the military services (1) have clarified guidance for responding to incidents of absent service members; and (2) maintain data on cases of absent service members from fiscal years 2015 through 2024.

For our first objective, we analyzed DOD and service-level policies on responding to incidents of missing and absent service members and interviewed relevant officials concerning their implementation.[6] We assessed the military services’ procedures for responding to absences against DOD policies and federal internal control standards.[7] To provide context for these issues, we conducted a series of eight site visits, two per military service, and interviewed a variety of officials at these locations concerning their role in responding to incidents of missing and absent service members.

For our second objective, we obtained and analyzed data on absences for fiscal years 2015 through 2024, including involuntary absence data from DOD’s central repository and voluntary absence data from each service’s personal information system or law enforcement system, as applicable. We assessed the reliability of absence data by interviewing knowledgeable officials, reviewing the data for obvious errors or outliers, and reviewing related documentation. We found the involuntary absence data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing how many service members were reported as involuntarily absent within this system.

For voluntary absences, we found the desertion data reported by the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force to be reliable for reporting the number of cases documented in the respective systems for each service. We could not determine the reliability of the desertion data from the Army’s legacy personnel system because they are incomplete. We are reporting the minimum number of desertions recorded in the Army’s system based on our analysis. We are reporting these numbers because they represent the best available data for this time period. We were also unable to include Army data for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 because the Army was unable to provide these data. We determined that the Army’s desertion data from its law enforcement system were incomplete and unreliable. We found unauthorized absence data for the Marine Corps and Air Force to be reliable for reporting the number of cases documented in the respective systems for each service. We determined that Army unauthorized absence data were not sufficiently reliable to report because they are incomplete, as discussed in this report. Further, we are not able to report on unauthorized absences in the Navy because Navy officials stated that they do not centrally collect such data. We also assessed the extent of the military services’ data on service member absences against DOD policies and federal internal control standards.[8] Appendix I provides additional details about our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Involuntary and Voluntary Absences

Involuntary service member absences are unintentional on the part of the service member and can result from an accident or foul play. DOD considers service members who are involuntarily absent to be casualties.[9] DOD casualty policy identifies two types of involuntary absences that can occur in nonhostile settings:

· Duty status-whereabouts unknown (DUSTWUN). This transitory status is used when a commander suspects a service member’s absence is involuntary but does not feel sufficient evidence currently exists to determine whether the service member is missing or deceased.

· Missing. This status is used when a service member is absent from their duty location for seemingly involuntary circumstances, and their location is unknown.[10]

Voluntary absences are intentional on the part of the service member. DOD policy identifies two types of voluntary absences:

· Absence Without Leave/Unauthorized Absence. This duty status occurs when service members are absent without authority or without leave from the unit, organization, or other place of duty where they are required to be.[11] The two terms refer to the same type of absence, with absence without leave used within the Army and Air Force and unauthorized absence used within the Navy and Marine Corps. An unauthorized absence is an offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[12]

· Desertion. This duty status occurs when a service member intends to be permanently absent from military service. For example, DOD policy states that an absent service member is to be classified as a deserter when the service member has been absent for 30 consecutive days; if the facts and circumstances of the absence, regardless of its length, show that the service member may have committed the offense of desertion; or if the service member, while in a foreign country, requests or accepts asylum or a residence permit from that country. Desertion is an offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.[13]

Roles and Responsibilities for Responding to Service Member Absences

Various DOD personnel and organizations have roles and responsibilities related to involuntary and voluntary service member absences. Specifically, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (OUSD(P&R)) provides overall policy guidance for all military service programs designed to deter and reduce absenteeism and desertion.[14] In addition, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs (ASD(M&RA)), as principal advisor to USD(P&R) on all matters related to manpower and reserve affairs, serves as the focal point for casualty matters and develops policy for, and provides oversight of, casualty and mortuary affairs programs.[15]

Several offices within the military services are responsible for developing policies and overseeing activities related to the reporting of and response to involuntary and voluntary absences. These include the Army’s Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel and the Army Human Resources Command; the Navy’s Office of the Chief of Naval Personnel and the Navy Personnel Command; the Marine Corps’ Office of the Deputy Commandant for Manpower and Reserve Affairs and Office of the Deputy Commandant for Plans, Policies, and Operations; and the Air Force’s Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Manpower, Personnel, and Services and the Air Force Personnel Center. Each of the policy and personnel offices has oversight of their respective service’s casualty and mortuary affairs program, while each service’s human resources or personnel center maintains and updates data on a service member’s duty and casualty status, such as those determined to be an unauthorized absence, deserter, or missing.

When an absence occurs, there are a variety of entities that, depending on the facts and circumstances of the situation, may be involved in responding to a service member’s absence. The relevant stakeholders may include:

· the service member’s command, which is responsible for initiating a search for the service member;

· each service’s military criminal investigative organization (MCIO), including the Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID), Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI), which investigate certain types of absences to help determine if foul play or desertion are factors;[16]

· the Navy Absentee Collection and Information Center and Marine Corps Absentee Collection Center, which are responsible for apprehension of deserters in their respective services;

· service military police or law enforcement organizations, which have responsibility for investigating certain unauthorized absences and for coordinating with civilian law enforcement;

· service casualty offices, which notify and assist family members when the service has determined the service member is a casualty, to include those who are designated as DUSTWUN or missing; and

· service personnel or human resource organizations, which are responsible for updating and maintaining official records reflecting the service member’s duty and casualty status.

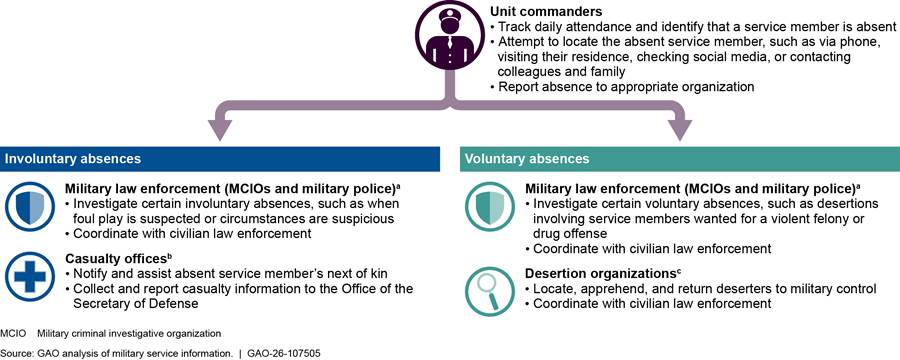

Figure 1 shows the key personnel and organizations within the military services that are involved in responding to service member absences, including unit commanders, military law enforcement, casualty offices, and desertion organizations.

aThe MCIOs investigate violent crimes and other serious offenses, which can include service member absences. There are three MCIOs—the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (which performs criminal investigations for both the Navy and the Marine Corps), and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations. We use the term military police to refer to installation law enforcement, which may be involved in the initial investigation of a service member absence.

bThe military services’ casualty offices include the Army Casualty and Mortuary Affairs Operations Division; Navy Casualty (PERS-00C); the Air Force Personnel Center Casualty Matters Division; and the Marine Corps Marine and Family Programs Division.

cThe Navy and the Marine Corps have dedicated desertion offices—the Navy Absentee Collection and Information Center and the Marine Corps Absentee Collection Center, respectively—for locating and returning deserters. In contrast, the Army relies on its military police, and the Air Force relies on the Office of Special Investigations for these functions.

Most Services Have Guidance for Responding to Absences but Face Gaps

The Army, Navy, and Air Force have issued guidance for locating absent service members. The Marine Corps continues to lack such guidance, but stated it is working to develop it. However, we identified gaps in service guidance that pose challenges to efforts to locate absent service members. In addition, the services differ in how they distinguish between voluntary and involuntary absences at both the command level and within the MCIOs.

Most Military Services Have Issued Guidance for Locating Absent Service Members; Marine Corps Is in the Process of Doing So

The Army, the Navy, and the Air Force have issued guidance to facilitate a command’s efforts to locate a service member who is deemed “absent” from their assigned duty location. Army and Navy guidance articulate a series of similar steps for commanders to follow when attempting to locate an absent service member.[17] This includes actions such as checking the service member’s residence, inquiring with local hospitals, and contacting their spouse or friends to determine their last known location. Air Force guidance is designed to aid commanders in determining whether the absence is voluntary or involuntary and includes prompts for commanders to inquire about potential marital issues, the absence or presence of personal belongings, and whether the service member had been engaged in recreational activities— such as hiking or swimming—prior to their absence being reported.[18]

During our visits to six installations across the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force, officials described similar steps that they take to identify and respond to an absence. For example, officials from commands at each location we visited stated that they track attendance at daily morning physical training, formation, or in other regular check-ins. Once an absence is confirmed, officials outlined a series of progressive steps to contact the service member, including phone calls or texts, sending a command representative to their residence, contacting known friends and family, and reviewing the service member’s social media for clues as to their location.

Officials at the two Marine Corps locations we visited outlined daily steps they take to account for personnel and locate them similar to those at the Army, Navy, and Air Force locations that we visited. However, the Marine Corps does not have guidance that outlines a formalized process for locating a service member who is deemed absent, including procedures for unit commanders to use to determine whether a service member’s absence is involuntary or voluntary. We previously recommended that the Marine Corps develop such guidance, and the Marine Corps stated that it is working to implement this recommendation.[19] By taking such action, the Marine Corps can provide commanders with a documented framework to guide their response process and further the goal of returning service members safely if at all possible.

Gaps in Service Guidance Pose Challenges to Response Efforts

Although the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force have developed guidance for locating absent service members, we identified several gaps related to (1) response time frames, (2) mental health concerns, and (3) potential safety issues that could undermine the effectiveness of service efforts to respond to such incidents and mitigate associated risks.

Designating response time frames. DOD guidance requires the military services to report voluntary and involuntary absences and to apprehend deserters and absentees as promptly as possible.[20] Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force officials we interviewed commonly recognized the importance of attempting to locate an absent service member in a timely manner. However, the guidance provided by each service outlines response time frames with varying levels of specificity, resulting in different interpretations among officials regarding how quickly certain actions should be initiated.

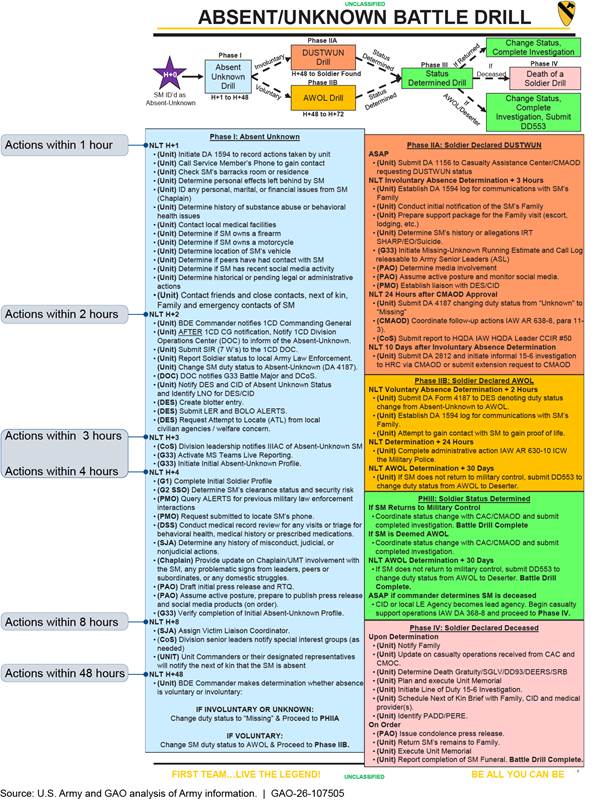

For example, Army-wide guidance requires commands to report an absence to Army law enforcement within 3 hours of its discovery and to notify the next of kin within 8 hours.[21] Installation-level guidance that we obtained during our review specifies further hour-by-hour actions that personnel are expected to adhere to when attempting to locate an absent service member. Specifically, guidance at the two locations we visited specified that within the first hour of an absence, commanders will attempt to contact the absent service member, check their barracks or residence, and communicate with friends and close contacts, among other steps. In the second hour, they are directed to notify various command officials and to coordinate with law enforcement. These steps continue through the following hours and days. Figure 2 shows an example of absent service member response actions at one of the Army locations we visited, along with the time frame for such response actions.

Figure 2: Example of an Army Installation Drill for Absent Service Member Response and Hourly Time Frame for Response Actions

The Army instituted its service-wide guidance in 2020 in response to the Report of the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee, which found that the Army lacked protocols for the critical first 24 hours of a soldier’s absence. Officials at the installations we visited highlighted the specificity of the Army’s process and that it helps to ensure continuity in practice across changes in unit leadership.

In contrast, Navy and Air Force guidance does not identify when response personnel should initiate specific tasks associated with locating an absent service member. For example, Navy guidance states that commanders should visit the absent service member’s residence, contact law enforcement, and check the absent service member’s social media for clues as to their whereabouts within 24 hours of an absence, whereas Air Force guidance does not provide any time frames for similar actions.[22] Navy and Air Force officials we spoke with told us that, although they do not have set timelines for specific actions, they recognize that it is important to promptly initiate and carry out efforts to locate an absent service member. For example, most officials stated that they would attempt to contact the service member by phone and send someone to visit their residence within a few hours of becoming aware of the absence.

However, during our site visits, we found that the absence of more specific time frames has led to differing interpretations among Navy and Air Force officials regarding what constitutes a timely response. For example, some officials stated that they would alert the appropriate higher-level command of an absence within a few hours, while others stated they would wait until the end of the day, the following day, or even longer if non-duty days (such as a weekend) intervened. Similarly, some officials said they would contact installation law enforcement within a few hours of being unable to locate a service member, while others preferred to wait until the following day to give the service member an opportunity to return to duty without escalating the issue. Other officials cited a desire to exhaust all efforts to locate an individual before involving law enforcement. MCIO agents at one location we visited noted with concern that commanders may wait for several days of an absence to pass before contacting them. In addition, some officials stated that they would respond with less urgency to the absence of a service member with a history of tardiness or truancy, potentially delaying the response.

Addressing mental health. DOD policy acknowledges the relationship between effective suicide prevention and putting time and space between someone at risk of suicide and the means to commit suicide. It further notes that DOD personnel will take rapid action to ensure care for and to reduce the risk associated with service members who are thought to be a danger to themselves or others.[23] Separately, the Report of the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee noted in its assessment of Army practice that the course of action taken in the initial response process was crucial in the case of a service member at risk of self-harm.

However, Army, Navy, and Air Force guidance does not consistently address the interconnected nature of mental health issues with service member absences and how considerations of mental health should inform their response. For example, Navy guidance states that commanders should inquire with counseling services or chaplains to try and determine the cause of the absence, but it does not explain how any input obtained should inform efforts to locate the service member.[24] Army and Air Force guidance does not directly address the role that mental health may play in a service member’s absence and how it should guide their response.[25] We identified installation-level guidance at two Army sites we visited that contained some information on efforts to locate absent service members who may have mental health issues. However, this guidance is specific to these installations and is not necessarily a standard practice at all Army installations.

Army, Navy, and Air Force officials we met with commonly observed a link between service member absences and mental health and said that locating absent service members often intersects with efforts to prevent self-harm and suicide. Officials at several locations cited examples of the search for an absent service member becoming a mental health crisis management incident. For example, officials at one installation cited the case of an absent service member in which command officials arrived at the residence during their attempt at self-harm. Further, an official at one Army location observed that a majority of service member absences they investigated over the past year involved suicidal ideations. Others noted the importance of having a deep understanding of their service members, including whether they are being actively monitored by the command for mental health issues or drug and alcohol abuse.

Nevertheless, in the absence of relevant guidance, the service officials we spoke with did not share a consistent perspective on how mental health considerations should inform the strategies used to locate absent personnel. For example, some officials said they would respond more rapidly or take extra safety precautions if the absent service member had a known mental health issue, such as a greater willingness to initiate the legal process for a mobile phone “ping” to geolocate the individual, while others said they would use relevant resources, such as social workers or chaplains. However, while Navy guidance states that commanders should inquire with counseling services or chaplains, such precautions are otherwise not standardized or recommended in the services’ guidance. Moreover, we spoke with a senior MCIO official who expressed concern that commands are not adequately equipped to manage mental health crises, and that more explicit guidance on this subject is necessary to help them execute their responsibilities.

Anticipating safety issues. DOD policy states that when a service member is exhibiting dangerous behavior, the first priority of the commander or supervisor is to ensure that precautions are taken to protect the safety of the service member and others.[26] However, Army, Navy, and Air Force guidance does not identify and address potential safety issues that may arise in a search for an absent service member, potentially subjecting the absent service member or those attempting to locate them to unnecessary risk.[27]

Army, Navy, and Air Force officials at many of the installations we visited described a range of potential safety issues that may arise while searching for an absent service member. Some officials cited safety concerns that may arise during the command-managed search—particularly those that can occur while attempting to contact a service member at their residence. Specifically, some officials told us that an individual sent to check on an absent service member could be placing themselves in physical danger, especially if the service member is experiencing a mental health crisis and has access to a firearm. For example, a law enforcement official at one location described an instance in which an attempt to contact an absent service member at their home was complicated by threats that the service member had previously made against the command.

Officials described various ways they may try to mitigate such issues. For example, the checklist at one Army location we visited includes an assessment of the presence of firearms at the absent service member’s residence, while officials at multiple locations noted a practice of involving installation security or local law enforcement in checks at barracks or residences. However, such precautions are not standardized or recommended in Army, Navy, or Air Force guidance. In addition, these were not universally recognized mitigation strategies. For example, some officials stated that local law enforcement should not be involved unless there was a known safety issue.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that organizations should define objectives clearly to enable the identification of risks and define risk tolerances. Specifically, organizations should define objectives in specific terms so they are understood at all levels of the entity, including clearly defining what is to be achieved, who is to achieve it, how it is to be achieved, and time frames for achievement.[28] Command personnel employ potentially consequential differences in how they locate an absent service member because the military services’ guidance does not clearly specify how the timing of actions in the initial response process, mental health concerns, and possible safety issues should inform these efforts.

In September 2025, the Air Force provided draft guidance concerning the command response to service member absences. The draft guidance included additional information building upon its current guidance in various respects, including greater clarity on the timeline for responding to a service member’s absence. This revision, when implemented, will support improvements in the Air Force’s response to service member absences. However, this guidance has not been finalized and issued.[29] Moreover, as previously noted, while the Marine Corps stated it is working to develop guidance, it has not yet done so and therefore has not specified how these elements should be addressed when attempting to locate absent service members.

Various service officials expressed concern with developing guidance that is too rigid as they want to preserve commanders’ independence to manage their personnel and to provide them with the flexibility to adjust their response as dictated by the needs of each case. Further, some officials said that overly prescriptive guidance can result in response personnel becoming fixated on the need to address individual provisions rather than exploring out-of-the-box solutions.

We recognize the authority of commanders and the importance of being able to adapt response efforts to the unique circumstances and dynamic nature of individual cases. However, additional guidance is not at odds with these preferences. Rather, it would enhance commanders’ ability to ensure greater consistency, efficiency, and safety in the response process. Further, as the Report of the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee highlighted, clear formal guidance for the command-led response process during the first 24 hours following an absence can help to prevent harm and save lives.

Services Vary in How They Distinguish Between Voluntary and Involuntary Absences

The military services differ in how they determine whether and when a service member’s absence is voluntary or involuntary, a critical distinction that influences the strategies to locate them. During our site visits, command officials and agents with each service’s MCIO frequently emphasized that their main priority is to ensure the safety of the individual and to confirm that they are not at risk of self-harm or external threats while attempting to locate a missing service member. However, existing guidance and policies for commanders and MCIOs lack clarity on whether and when to categorize an absence as voluntary or involuntary, which can significantly affect the urgency and comprehensiveness of search efforts.

Commanders. In response to the findings of the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee, the Army issued guidance in 2020 that requires commanders to place absent service members in a new duty status unique to the Army—referred to as “absent unknown”—and initiate a series of investigative steps that effectively assumes the service member may be in danger. Further, the commander must determine if the absence is voluntary or involuntary within 48 hours and may only determine that the absence is voluntary if supported by the preponderance of evidence gathered during this time period.[30] In other words, the absence is effectively assumed to be involuntary unless there is significant evidence to suggest otherwise.

The Committee highlighted that the lack of established protocols led Army units at Fort Hood to assume that absences were voluntary, which may have resulted in delayed or inadequate responses. The new guidance includes specific time frames that are designed to address risks and the safe recovery of the missing service member. The Navy and Air Force have guidance on responding to service member absences, but the guidance does not require commanders to presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger. The guidance also does not require commanders to establish the presumption that such absences are most likely involuntary after a specified time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. As previously noted, the Marine Corps does not have guidance on responding to service member absences but stated it is developing such guidance.

The OUSD(P&R) provides overall policy guidance for all military service programs designed to deter and reduce absenteeism and desertion.[31] In addition, the ASD(M&RA), as principal advisor to USD(P&R) on all matters related to manpower and reserve affairs, serves as the focal point for casualty matters and develops policy for, and provides oversight of, casualty and mortuary affairs programs.[32] The timing of when each service determines whether an absence is voluntary or involuntary varies because DOD policy does not require the services to issue guidance that commanders should initially presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger and that commanders should presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. By revising DOD-wide policy to require the military services to issue such guidance, OUSD(P&R) will provide the military services with a consistent basis on which to structure their individual approaches to locating absent service members.

In addition, DOD guidance requires that when reasonable, casualty procedures be uniform across the military departments.[33] It will therefore be important for the military services to update their respective guidance to align with any such revised DOD-wide policy to help ensure that all commanders promptly employ the necessary resources and personnel to maximize their ability to safely locate an absent service member.

MCIOs. MCIOs can play a significant role in a command’s efforts to locate a missing service member. For example, MCIO officials told us that they can assist with cellphone “pings” to geolocate an absent service member. However, as outlined in MCIO guidance, the MCIOs generally do not investigate voluntary unauthorized absences.[34] Therefore, if an absence is initially viewed as an unauthorized absence, commands might not contact an MCIO, and criminal investigators might not investigate the circumstances of the absence. Consequently, a command’s initial classification of an absence as likely voluntary or involuntary can influence the speed at which an MCIO may become involved in the case.

Current service-specific guidance includes different interpretations of how the MCIOs initially treat service member absences. Specifically, the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI) manual on criminal investigations requires investigators to treat absences as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise.[35] According to OSI agents at one Air Force location we visited, this approach is preferred as it enables them to investigate absences as soon as possible and can withdraw from a case when it becomes evident that the absence is voluntary. Conversely, Army Criminal Investigative Division (CID) and Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) guidance does not specify that all absences should initially be treated as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise, which has resulted in varied approaches to categorizing service member absences.[36] Specifically:

· Though not required in CID guidance, CID agents at both Army locations we visited told us it is their practice to become involved in a service member’s absence as soon as possible, adding that they can always remove themselves if it becomes clear the absence is voluntary.

· NCIS agents at the Navy and Marine Corps sites we visited consistently expressed a cautious view of their jurisdiction and when to initiate an investigation. For example, some agents said they would not become involved unless there was clear evidence of a crime, while others viewed the process of searching for an absent service member to primarily be the responsibility of the supervising command.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that organizations should implement control activities through policies, including periodically reviewing policies and procedures for continued relevance and effectiveness in achieving their objectives.[37] MCIO agents at the installations we visited told us that safely locating an absent service member is their highest priority and that swift action is key when absences may involve self-harm or external threats. However, CID and NCIS may be unintentionally undermining their ability to effectively address this priority because they have not reviewed their approach to categorizing absences. Specifically, they have not assessed the merits and challenges of clarifying in guidance that all absences should initially be treated as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise.

A senior Army CID official said that their investigative manual is under revision and was confident that, once it is finalized, it would provide greater clarity on CID’s ability to become involved in service member absences. However, the official could not confirm whether it would require CID to initially treat an absence as involuntary, as is currently the practice of the Air Force OSI. A senior NCIS official stated that it would be feasible to clarify their guidance on when they can become involved in service member absences. However, they reiterated that it is important for commands to continue to have primary responsibility for initiating efforts to locate absent service members—after which they can seek assistance from NCIS. The official said that this approach enables NCIS to judiciously manage its limited resources.

We recognize that neither CID nor NCIS is required to revise their approach to initially treat a service member absence as involuntary. However, doing so could aid in suicide prevention, which is a key DOD goal. As discussed in this report, officials we met during our site visits commonly observed a link between service member absences and mental health and said that locating absent service members often intersects with efforts to prevent self-harm and suicide. Finally, it would further the shared goal of all parties involved to leverage every possible resource in the hope of safely and promptly locating absent service members, particularly if OSD and the services similarly update guidance for commanders to presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary, as we are recommending. Without a review of their current approach that assesses the merits and potential challenges of initially treating all service member absences as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise, CID and NCIS may compromise their ability to support DOD’s overarching goal of quickly and safely locating absent service members.

The Military Services’ Data Do Not Fully Capture Service Member Absences

The Services Collect Data on Involuntary Absences, but the Navy’s “Missing” Data Are Not Comparable to the Other Services

In accordance with DOD policy, the military services collect and maintain data on involuntary absences, which includes two casualty status categories: (1) duty status-whereabouts unknown (DUSTWUN), and (2) missing.[38] While we found that the DUSTWUN data from the services are typically consistent, the Navy’s data on “missing” service members cannot be directly compared to those from the other services.

From fiscal year 2015 through 2024, the services recorded a total of 295 service members as being involuntarily absent in a nonhostile setting—ranging from a high of 53 in 2017 to a low of 17 in 2022. Table 1 provides additional information on the number of involuntary absences recorded by each military service annually from fiscal years 2015 through 2024.

Table 1: Total Involuntary Absences in a Nonhostile Setting, by Military Service, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

|

Fiscal year |

Army |

Navy |

Marine Corps |

Air Forcea |

Total |

|

2015 |

6 |

4 |

17 |

6 |

33 |

|

2016 |

9 |

4 |

14 |

9 |

36 |

|

2017 |

8 |

23 |

20 |

2 |

53 |

|

2018 |

1 |

15 |

6 |

9 |

31 |

|

2019 |

4 |

3 |

7 |

5 |

19 |

|

2020 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

5 |

23 |

|

2021 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

7 |

31 |

|

2022 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

17 |

|

2023 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

4 |

18 |

|

2024 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

13 |

34 |

|

Total |

54 |

76 |

99 |

66 |

295 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense information. | GAO‑26‑107505

aSpace Force involuntary absence data are included as part of the Air Force’s data. There was one nonhostile involuntary absence within the Space Force between the service’s creation in 2020 and fiscal year 2024.

Our analysis determined that approximately 93 percent (274) of all involuntary absences recorded in fiscal years 2015 through 2024 resulted in a declaration of death. Of these cases, accidents accounted for the majority of fatalities at approximately 78 percent, followed by suicides at around 10 percent. The Navy and the Marine Corps recorded the highest number of involuntary absences during fiscal years 2015 through 2024—primarily due to a small number of events that occurred in specific years. For example, in fiscal year 2017, 17 of the 23 involuntary absences recorded by the Navy stemmed from two separate collisions involving the USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain, while 15 of the 20 involuntary absences recorded by the Marine Corps resulted from a single aircraft accident.

From fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the services recorded 293 of the 295 instances of involuntary absences in the “DUSTWUN” category, while two cases were classified as “missing.” While each service is able to organize its involuntary absence data into these two categories, comparisons are limited due to different service definitions for what constitutes a “missing” service member. Specifically, Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force policies define “missing” as those service members who are involuntarily absent due to either hostile or nonhostile action.[39] This aligns with current DOD policy, which indicates that the “missing” casualty status can be applied to involuntary absences in both hostile and nonhostile settings.[40]

In contrast, the Navy’s policy limits its definition of “missing” to only those involuntary absences directly resulting from or associated with hostile actions.[41] According to Navy officials, service members who are deemed involuntarily absent in a nonhostile setting will be held in a “DUSTWUN” status until they are either located or administratively declared deceased.

DOD policy requires the services to adopt consistent definitions for casualty statuses and to establish uniform casualty procedures to help ensure that there is an accurate record of deceased or “missing” personnel.[42] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, including defining the identified information requirements at the relevant level and requisite specificity.[43]

However, the Navy’s data on “missing” service members cannot be directly compared to those of the other services because it has not adopted a definition of “missing” that aligns with the definition established in DOD-wide policy. Navy officials acknowledged that their definition of “missing” differs from that of the other military services, but they were not aware of any issues stemming from this differentiation.

We recognize that any issues posed by the Navy’s differing “missing” definition may not be apparent when these data are viewed in isolation. However, this inconsistent definition produces an inaccurate picture of “missing” incidents across DOD. By adopting a definition of “missing” that aligns with the one established in DOD policy and used by the other military services, the Navy will help to ensure that DOD has a reliable understanding and consistent tracking of the number of missing service members across the department.

Service Data on Voluntary Absences Vary in Completeness and Reliability

The military services also collect data on voluntary absences, which include unauthorized absence and desertion cases.[44] However, the completeness and reliability of these data for fiscal years 2015 through 2024 varies because some services have incomplete data on unauthorized absences and others have multiple, inconsistent sources of data on desertions.[45]

Some Services’ Data on Instances of Unauthorized Absence Are Incomplete

The services’ data on instances of unauthorized absence from fiscal years 2015 through 2024 reflect varying levels of completeness, which limits the extent of the data we are able to report for this time period. Specifically, our analysis determined that Marine Corps and Air Force data on instances of unauthorized absence are generally complete, whereas the Army’s and Navy’s data are not.

· Marine Corps. The Marine Corps recorded 2,680 instances of unauthorized absence from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, ranging from a high of 346 in 2016 to a low of 194 in 2021.[46] Our analysis of Marine Corps data shows that approximately 65 percent (1,745) of all reported unauthorized absence cases during the 10-year period of our review ended with the service member being returned to military control.[47] Additionally, of the total reported unauthorized absence cases, approximately 5 percent (127) were female service members and approximately 95 percent (2,553) were male service members. Table 2 provides additional information on the number of service members in an unauthorized absence status and those returned to military control recorded by the Marine Corps during this time period.

Table 2: Marine Corps Unauthorized Absence Cases and Number Returned to Military Control, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

|

Fiscal year |

Unauthorized absence cases |

Returned to military control |

|

2015 |

345 |

199 |

|

2016 |

346 |

214 |

|

2017 |

290 |

181 |

|

2018 |

343 |

205 |

|

2019 |

229 |

153 |

|

2020 |

214 |

137 |

|

2021 |

194 |

143 |

|

2022 |

218 |

128 |

|

2023 |

224 |

146 |

|

2024 |

277 |

239 |

|

Total |

2680 |

1745 (65%) |

Source: GAO analysis of Marine Corps information. | GAO‑26‑107505

· Air Force. The Air Force recorded 405 instances of unauthorized absences from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, ranging from a high of 56 in 2023 to a low of 31 in 2016 and 2018.[48] Our analysis of Air Force data shows that approximately 83 percent (338) of all unauthorized absence cases recorded during the 10-year period of our review ended with the service member being returned to military control, while a total of 67 unauthorized absence cases resulted in the service member being designated a deserter. Additionally, of the total reported unauthorized absence cases, approximately 20 percent (80) were female service members while approximately 80 percent (325) were male service members. Table 3 provides additional information on the number of unauthorized absence cases and those returned to military control case status recorded by the Air Force during this time period.

Table 3: Air Force Unauthorized Absences and Those Returned to Military Control, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

|

Fiscal year |

Unauthorized absence cases |

Returned to military control |

|

|

2015 |

51 |

42 |

|

|

2016 |

31 |

27 |

|

|

2017 |

33 |

30 |

|

|

2018 |

31 |

27 |

|

|

2019 |

34 |

24 |

|

|

2020 |

42 |

35 |

|

|

2021 |

34 |

27 |

|

|

2022 |

55 |

48 |

|

|

2023 |

56 |

48 |

|

|

2024 |

38 |

30 |

|

|

Total |

405 |

338 (83%) |

Source: GAO analysis of Air Force information. | GAO‑26‑107505

Note: Of the unauthorized absence cases in this table, 67 resulted in the service member subsequently deserting. The remainder returned to military control.

We are currently unable to report instances of unauthorized absence within the Army and Navy for fiscal years 2015 through 2024 because our analysis determined that these data are incomplete.

· Army. Headquarters officials told us they did not have a complete accounting of unauthorized absences because their legacy personnel system only stored these data for 130 days after an individual separated from the Army.[49] These officials said that after this 130-day period, the data are automatically removed from the system. However, Army officials said that they are in the process of fielding a new personnel and pay system that will allow them to permanently store voluntary absence data, including instances of unauthorized absence.[50] Army headquarters officials said that they began transitioning to this new system in December 2022 and expect it to be fully operational by the end of 2025.

· Navy. Officials told us that they currently do not have a service-wide system or process for collecting and maintaining data on unauthorized absences. Rather, the extent to which such data are collected and maintained is at the discretion of individual commands. Navy officials told us that they are developing a new personnel and pay system that will enable them to collect and maintain service-wide unauthorized absence data and estimated that it will reach initial operating capability in 2027.

We are not making recommendations to the Army and Navy on this issue as they are in the process of developing systems that officials expect will address the shortfalls we found.

Some Services Have Multiple, Inconsistent Sources of Data on Desertions

The services record data on service member desertions, but these data are maintained in varying data systems. Based on our analysis of available data, the military services recorded approximately 3,257 service member desertions from fiscal years 2015 through 2024. However, as discussed below, we were unable to determine the reliability of Army data for fiscal years 2015 through 2022 because they were incomplete. We are reporting the minimum number of desertions recorded in the Army’s system based on our analysis. We were also unable to include Army data for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 because the Army was unable to provide these data. See appendix I for further details. The percentage of deserters who returned to military control varied from 65 percent in the Navy to 99 percent in the Air Force, as shown in table 4. The vast majority of deserters were males, with the percentage of female deserters varying, including 7 percent in the Army, 16 percent in the Navy, 3 percent in the Marine Corps, and 18 percent in the Air Force.

Table 4: Number of Desertions Recorded by the Military Services and Those Returned to Military Control, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

|

Fiscal year |

Desertion cases |

Returned to military control |

Desertion cases |

Returned to military control |

Desertion cases |

Returned to military control |

Desertion cases |

Returned to military control |

|

|

Armya |

Marine Corps |

Air Force |

Navy |

||||

|

2015 |

162 |

114 |

112 |

77 |

21 |

21 |

22 |

10 |

|

2016 |

164 |

128 |

104 |

82 |

11 |

11 |

104 |

76 |

|

2017 |

186 |

170 |

101 |

81 |

7 |

7 |

68 |

44 |

|

2018 |

246 |

223 |

103 |

96 |

12 |

12 |

79 |

60 |

|

2019 |

221 |

252 |

80 |

90 |

17 |

16 |

65 |

46 |

|

2020 |

169 |

139 |

74 |

63 |

14 |

14 |

80 |

42 |

|

2021 |

100 |

166 |

47 |

27 |

13 |

13 |

152 |

80 |

|

2022 |

29 |

61 |

58 |

93 |

13 |

13 |

163 |

111 |

|

2023b |

- |

- |

70 |

68 |

18 |

18 |

104 |

75 |

|

2024c |

- |

- |

150 |

91 |

11 |

11 |

107 |

71 |

|

Total |

1277 |

1253 (98%) |

899 |

768 (85%) |

137 |

133 (99%) |

944 |

615 (65%) |

Source: GAO analysis of military service information. | GAO‑26‑107505

Note: The Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force desertion data shown in this table were taken from each respective service’s personnel systems. The Navy desertion data shown in this table were taken from its law enforcement system since the Navy does not currently have a personnel system that tracks desertion data.

aWe were unable to determine the reliability of the desertion data provided by the Army because they are incomplete. Army officials said the data they provided for our analysis represent the minimum number of desertions and instances of return to military control recorded in the Army’s system. We are reporting these numbers because they represent the best available data for this period of time.

bWe were unable to acquire Army desertion data for fiscal year 2023 because the Army was unable to provide these data.

cWe were unable to acquire Army desertion data for fiscal year 2024 because the Army was unable to provide these data.

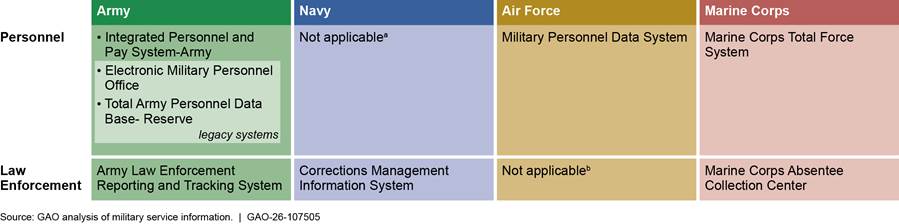

The military services record data on service member desertions using various data systems. Figure 3 shows information systems used by the military services to collect voluntary absence data.

aNavy officials said they are currently developing a new personnel system that will track voluntary absences, including desertions.

bAir Force officials said that the Office of Special Investigations system is not intended to be a complete record.

However, the data in these different systems do not always align. For example,

· Army policy identifies its personnel system as the system of record for Army personnel accounting, which should be used to record desertions.[51] However, Army officials said that the desertion data in its legacy personnel database are incomplete, and that the new personnel system still has not been fully implemented. We were unable to determine the reliability of the desertion data provided by the Army from its legacy personnel system because they are incomplete. The data from this system included in this report are the minimum number of desertions and instances of return to military control recorded in the system based on our analysis. We are reporting these numbers because they represent the best available data for fiscal years 2015 through 2022. Army policy also requires that all desertions be recorded in the Army’s law enforcement system.[52] However, we determined that the desertion data found in the Army’s law enforcement system are incomplete and unreliable. See appendix I for further details on our assessment of data from the Army’s legacy personnel database and law enforcement system.

Separate from the challenges with the completeness and reliability of these data, this dual approach has resulted in two sources of desertion data, which is problematic because the data in these systems do not align. Specifically, for fiscal years 2015 through 2022, the Army’s personnel system recorded approximately 1,277 desertions, while the Army’s law enforcement database recorded approximately 3,580 desertions for the same time period.[53] Officials from the Army’s Human Resources Command told us that they do not reconcile desertion numbers between the personnel system, which they manage, and the law enforcement system, which is jointly managed by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division and the Office of the Provost Marshal General. Additionally, Army law enforcement officials said that the data discrepancies are expected, given that the purpose of their system is to aid investigations and not represent a complete record of the case.

· The Marine Corps maintains data on desertions both in its personnel system as well as in a database maintained by its Absentee Collection Center, but these data do not align. Specifically, the Marine Corps personnel system recorded 899 desertions from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, while the Marine Corps Absentee Collection Center recorded 662 desertions over the same time period.[54] Officials from the Marine Corps Absentee Collection Center stated that there is no process to reconcile data between the personnel system and their database. These officials also said that some desertions are either reported inaccurately, not reported in a timely manner, or not reported at all, further contributing to the discrepancies between the two systems.

· While the Navy currently has a single source of data for desertions, it may face similar challenges as the Army and Marine Corps once its new personnel system is operational. Navy officials told us that they currently rely on the Corrections Management Information System for data on desertions. However, once the new personnel system is operational, it will serve as an additional source for these data.

· The Air Force also collects some data on desertions in a law enforcement system, but OSI officials stated that their database exists to assist them in investigations and is not intended to be a complete record of voluntary absences in the Air Force.

The OUSD(P&R) provides overall policy guidance for all military service programs designed to deter and reduce absenteeism and desertion.[55] In addition, the ASD(M&RA), as principal advisor to USD(P&R) on all matters related to manpower and reserve affairs, serves as the focal point for casualty matters and develops policy for, and provides oversight of, casualty and mortuary affairs programs.[56] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that organizations should use quality information to achieve their objectives and design their information systems and related control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. Specifically, organizations should evaluate information processing objectives to meet the defined information requirements to include completeness, accuracy, and validity. It also states that organizations should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks and implement them through policies.[57]

While the services are collecting data on service member desertions, in some cases via their personnel systems as well as their law enforcement systems, OUSD(P&R) has not specified which system is the authoritative source for reporting these data. In 2022, we reported on inconsistencies in the services’ desertion data, noting that the full extent of voluntary absences was unknown due to data that were incomplete or unreliable. We also reported that the military services did not regularly report data on voluntary absences to OSD. At the time, we recommended that DOD provide guidance to the services detailing a process for collecting and reporting such data. In July 2025, an official with OUSD(P&R) told us that DOD was working to address these recommendations, but as of February 2026 these recommendations remain open.

Moving forward, the department will be unable to confirm whether these data are reliable because it has not addressed the challenge of overlapping and inconsistent sources of data on desertions, such as by designating either each service’s personnel system or law enforcement system as the authoritative source for such information. While this action alone is not sufficient to ensure the reliability of data in these systems, it would be an important step toward a more complete and accurate picture of the number, rate, and outcome of such incidents.

Conclusions

A service member may be unexpectedly absent from their unit for a variety of reasons, ranging from making a deliberate decision to abandon their military duties to having a mental health crisis, being ill or injured, or foul play. A timely and well-coordinated response to a service member’s absence between unit commanders and law enforcement is critical to establishing the facts and helping to ensure the service member’s safe return, if possible.

However, four key challenges exist to DOD’s efforts to ensure a well-coordinated response. First, several gaps in service guidance related to (1) response time frames, (2) mental health concerns, and (3) potential safety issues could undermine the effectiveness of service efforts to respond to such incidents and mitigate associated risks. Second, existing guidance and policies for commanders and MCIOs lack clarity on whether to categorize an absence as voluntary or involuntary, which can significantly affect the urgency and comprehensiveness of search efforts. Third, the Navy’s data on “missing” service members cannot be directly compared to those from the other services, despite consistent definitions in DOD policy. Lastly, although the military services record data on service member desertions, they do so using various data systems, and the data within these systems do not always align. By addressing these issues, DOD and the services would be better positioned to prevent harm and save lives and have a reliable and consistent understanding of the number, rate, and outcome of incidents.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 12 recommendations, including two to the Secretary of Defense, two to the Secretary of the Army, six to the Secretary of the Navy, and two to the Secretary of the Air Force.

The Secretary of the Army should update guidance for responding to service member absences to ensure that it fully addresses the role of mental health issues and potential safety concerns that may arise during the response process. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Chief of Naval Operations updates guidance for responding to service member absences to ensure that it designates time frames for the response process as well as recognizing the role of mental health issues and potential safety concerns that may arise during the response process. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Commandant of the Marine Corps develops guidance on responding to service member absences that includes designated time frames for the response process and addresses the role of mental health issues and potential safety concerns that may arise during the response process. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Air Force should update guidance for responding to service member absences to ensure that it designates time frames for the response process and addresses the role of mental health issues and potential safety concerns that may arise during the response process. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness issues policy requiring the military services to issue guidance that commanders should presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger and should presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Chief of Naval Operations updates guidance to be consistent with and implement DOD’s revision to DOD-wide guidance, once completed, requiring that commanders should presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger and that the commander should presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Commandant of the Marine Corps develops guidance on responding to service member absences that is consistent with and implements the revised DOD-wide guidance, once completed, requiring that commanders should presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger and that the commander should presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of the Air Force should update guidance to be consistent with and implement DOD’s revision to DOD-wide guidance, once completed, requiring that commanders should presume a service member’s absence indicates that they are potentially in danger and that the commander should presume absences are most likely involuntary after a specific time period unless available information indicates the absence should be considered voluntary. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of the Army should ensure that the Director of the Criminal Investigative Division assesses the merits and potential challenges of initially treating all service member absences as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise; and as necessary, revises guidance to require such treatment. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Director of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service assesses the merits and potential challenges of initially treating all service member absences as involuntary until there is sufficient evidence to determine otherwise; and as necessary, revises guidance to require such treatment. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Chief of Naval Operations adopts a definition for the “missing” casualty status that aligns with the definitions established in Department of Defense policy and used by the other military services. (Recommendation 11)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness identifies either each service’s personnel system or law enforcement system as the authoritative source for collecting and reporting data on desertions from each of the services. (Recommendation 12)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of the report to DOD for review and comment. DOD, in its written comments (reproduced in appendix II), concurred with all 12 of our recommendations, including one concur with comment. We also received technical comments from DOD, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In its overall comments, DOD highlighted concerns regarding our characterization of guidance concerning DOD’s oversight of voluntary and involuntary absences. We have clarified the relevant sections to more precisely outline the responsibilities of the OUSD(P&R) and the ASD(M&RA).

In concurring with recommendations 2, 6, 10, and 11 concerning the Navy and Marine Corps, DOD stated that our recommendations should be revised to include the Chief of Naval Operations in addition to the Secretary of the Navy. We have made this revision for recommendations 2, 6, and 11. We did not make this revision for recommendation 10 because we believe the Director of NCIS is the appropriate official with responsibility to direct changes to NCIS’s approach to service member absences under Navy policy. DOD’s request to revise recommendation 10 also erroneously included information related to recommendation 11. However, in its response to recommendation 10, DOD made clear its concurrence with the intent of our recommendation and stated that the Navy will conduct an assessment and revise guidance as necessary.

In concurring with comment on recommendation 12, DOD stated it will consult with the military departments on how best to implement this recommendation consistent with their needs. We look forward to reviewing DOD’s efforts to implement this recommendation in the future.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Army, the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of the Air Force, the Chief of Naval Operations, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at williamsk@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Kristy E. Williams

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

This report builds on our 2022 review and assesses the extent to which the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the military services (1) have clarified guidance for responding to incidents of absent service members; and (2) maintain data on cases of absent service members from fiscal years 2015 through 2024.[58] Our review included the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, and the Air Force (including the Space Force).

Site Visits to Selected Military Installations

To provide context for our review, we conducted a series of eight site visits, two per military service, and interviewed officials at these locations concerning their role in responding to incidents of absent service members. Specifically, we visited Fort Hood, Texas and Fort Bliss, Texas (Army); Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia and Naval Base San Diego, California (Navy); Camp Lejeune, North Carolina and Camp Pendleton, California (Marine Corps); and Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Virginia and Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, Texas (Air Force). We selected these locations based on the fact that they are each among the largest installations for each service based on active-duty population.

At each installation, we interviewed officials generally responsible in some aspect for the response to a service member’s absence as applicable to that service or installation, including installation command staff, command staff of local major units or forces, installation security offices, judge advocates, casualty affairs representatives, and agents with local offices of each military department’s military criminal investigative organization (MCIO), as applicable and appropriate.

Because we did not select locations using a statistically representative sampling method, the comments provided during our interviews by officials are nongeneralizable and therefore cannot be projected across the Department of Defense (DOD) or a service, or any other installations. While the information obtained was not generalizable, it provided perspectives from officials who implement policies for managing absent service members on a routine basis.

Methods Used to Assess Development of Processes for Responding to Incidents of Absent Service Members

To assess the extent to which OSD and the military services have clarified guidance for responding to incidents of absent service members, we reviewed DOD and service-level guidance on responding to incidents of absent service members, including procedures at the unit level and within each service’s MCIO, and interviewed relevant officials concerning their implementation.[59] In addition, we assessed the extent to which commanders consistently approach key aspects of their response to absences by interviewing relevant officials as part of our site visits and by analyzing service guidance. Further, we assessed the services’ approach to distinguishing between voluntary and involuntary absences both by commanders and the MCIOs by reviewing service guidance and interviewing knowledgeable officials.

We compared the information obtained from our review of service guidance, documentation, and interviews to DOD guidance on self-harm and mental health, DOD guidance on roles and responsibilities, and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[60] We determined that the risk assessment and control activities components of internal control were relevant to this objective. Specifically, we identified the underlying principles that agencies should define objectives clearly to enable the identification of risks and define risk tolerances, and implement control activities through policies as relevant to this objective.

Methods Used to Assess Involuntary and Voluntary Absence Data

To assess the extent to which OSD and the military services maintain data on cases of absent service members from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, we obtained and analyzed data from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps on involuntary and voluntary absences during this time period, to the extent they were available. We selected data from this 10-year period to analyze any trends over time and because they were the most recent data available at the time of our review. However, we were unable to report data on voluntary absences in the Navy because Navy officials told us that they currently do not have a service-wide system or process for collecting and maintaining data on unauthorized absences. Rather, the extent to which such data are collected and maintained is at the discretion of individual commands. In addition, we were unable to acquire data from the Army’s personnel system for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 because the Army was unable to provide these data.

For involuntary absences, we analyzed data from DOD’s casualty information system—the Defense Casualty Information Processing System (DCIPS). The military services are required by DOD policy to report involuntary absence data to OSD through this system.[61] We analyzed the data to identify how many service members were reported as involuntarily absent in nonhostile settings in each military service in each fiscal year and across all 10 fiscal years and whether the absent service members were returned to military control. For voluntary absences, we analyzed data from each service’s relevant personnel and law enforcement information systems to identify how many service members were reported in an Absence Without Leave/Unauthorized Absence (AWOL/UA) or desertion status in each military service in each fiscal year across all 10 fiscal years.[62] Our scope included service members placed in an unauthorized absence or deserter status while on active duty. Service officials noted that reservists serving on active duty at the time of an authorized absence or desertion may be included, and data from the Marine Corps Absentee Collection Center included both active and reserve personnel. We determined that absence data from the Air Force’s law enforcement system were not intended to be comprehensive, and therefore did not obtain or analyze such data.