STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES:

Assistive Technology Challenges and Resources in Selected School Districts and Schools

Report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Education and Workforce, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Education and Workforce, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Jacqueline M. Nowicki, nowickij@gao.gov

What GAO Found

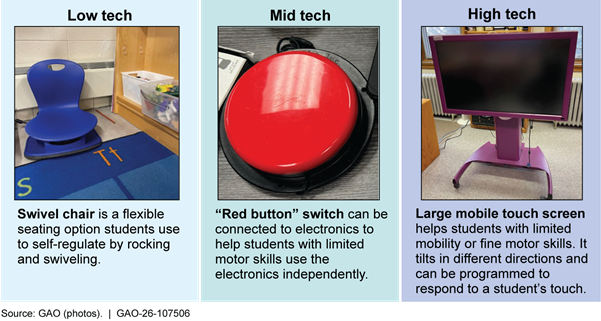

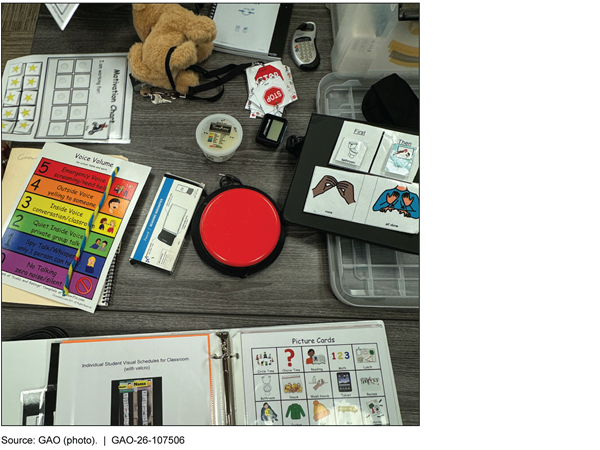

Assistive technology—such as pencil grips, calculators, and screen readers—can help students with disabilities more fully participate at school. Staff from the eight school districts that GAO visited provided examples of assistive technology that students use in the classroom (see figure). Limited knowledge about assistive technology was a key challenge, according to staff from all eight school districts GAO visited. For example, staff in many school districts said that teachers often only think of high-tech devices and may not consider simpler low-tech devices that could meet students’ individual needs. In addition, rapidly changing technology can make it difficult for school district and school staff to keep abreast of current assistive technology options. School district staff also described how broad challenges pertaining to public education adversely affected their ability to provide assistive technology to students with disabilities. These included insufficient time and opportunities for training, staffing issues (e.g., shortages and high turnover), technology issues, and funding constraints.

The eight school districts GAO visited sometimes formed assistive technology teams and used external resources, which helped mitigate some of the challenges described above. Specifically, four districts had assistive technology teams that helped improve coordination and increase staff knowledge about assistive technology, according to school district officials. The teams—generally comprised of district special education staff—help school staff develop standardized processes to identify the best assistive technology for students’ needs, document assistive technology use in students’ individualized education programs, and acquire assistive technology. In addition, district officials in all eight school districts said that they used federal, state, or regional resources to train school staff or provide assistive technology to students. These included external training, expert consultations, libraries that loan assistive technology, and guidance such as Education’s 2024 Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices and Services.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that all children with disabilities receive a free appropriate public education. Under IDEA, assistive technology must be considered for students receiving special education services. Little is known about how this requirement is implemented locally.

GAO was asked to review how schools make decisions about providing assistive technology to students with disabilities. This report describes (1) the assistive technology selected school districts provide to students and the challenges they face doing so, and (2) strategies and resources selected school districts use to provide assistive technology to students and mitigate challenges.

GAO visited four states—Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wyoming— selected for variation in factors such as percentage of students with disabilities and presence of state-level assistive technology initiatives. GAO interviewed staff from state and regional education agencies, eight school districts, and eight schools. GAO selected districts for variation in factors such as urbanicity and assistive technology initiatives. In addition, GAO interviewed officials and reviewed documents from the U.S. Department of Education (Education), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and both departments’ relevant technical assistance centers. GAO also conducted a web-based survey of all 93 Parent Centers—family technical assistance centers funded by Education—and received a response rate of 88 percent. We provided a draft of this report to Education and HHS for review and comment. Education provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. HHS did not provide any comments on the report.

Abbreviations

|

AT Act |

Assistive Technology Act of 2004 |

|

CITES |

Center on Inclusive Technology

and Education |

|

Education |

U.S. Department of Education |

|

FAPE HHS |

Free Appropriate Public Education U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

|

IDEA |

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act |

|

IEP |

Individualized Education Program |

|

Section 504 |

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 30, 2025

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

Dear Representative Scott:

Assistive technology can help students with disabilities participate more fully in school, improve their educational outcomes, and develop essential skills and abilities. Assistive technology includes any item, piece of equipment, or system that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of a student with a disability.[1] For example, highlighting pens and tape can help students who have difficulty focusing more easily find important points in their books. A computer with a specialized communication application can help students who have difficulty speaking participate at school.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that all children with disabilities receive a free appropriate public education (FAPE) that includes special education and related services that are designed to meet their unique needs.[2] During the 2022–23 school year, 7.5 million students ages 3 to 21—or 15 percent of all public school students—received special education services under IDEA.[3] Under IDEA, assistive technology must be considered for students receiving special education services. However, little is known about how this requirement is implemented locally. In January 2024, the U.S. Department of Education (Education) published guidance to dispel misconceptions about assistive technology, signaling that there may be confusion about what assistive technology is and what IDEA requires.

You asked us to review how schools make decisions about providing assistive technology to students with disabilities, the challenges schools face, and what federal guidance exists. This report addresses (1) what assistive technology selected school districts provide to students and the challenges school districts report and (2) the strategies and resources that selected school districts use to provide assistive technology to students and mitigate challenges.

To address both objectives, we visited four states—Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wyoming. We selected states that reflect variation in geographic region, number and percentage of students with disabilities, percentage of English learners with disabilities, per-pupil IDEA funding, the presence of state-level assistive technology initiatives, and state population. Within each state, we visited and interviewed staff from two school districts, including one school per district, for a total of eight school districts and eight schools.[4] In each district, we interviewed district officials and school staff such as special education teachers, general education teachers, administrators, and related service providers (e.g., speech-language pathologists, school psychologists, and occupational therapists).[5] We also interviewed officials from regional educational service agencies that support the districts we selected in Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Texas.[6] In all four states, we interviewed officials from the state education agency and the state’s Assistive Technology Act of 2004 (AT Act) Program and reviewed state guidance and resources related to assistive technology.[7]

We asked interviewees how school districts provide assistive technology to students with disabilities; any challenges staff, students, or families report regarding assistive technology; and what strategies they use to mitigate those challenges. We also asked interviewees about the resources they use to learn about assistive technology and provide it to students. We analyzed the information from these interviews to identify themes. While not generalizable to all states, our site visits provide examples of how school districts provide assistive technology.

To further understand what resources selected school districts use to provide assistive technology to students, we interviewed officials from Education and obtained input from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Both departments support states and districts in providing assistive technology to students. We also reviewed guidance and other documents from Education, as well as federal laws and regulations. In addition, we interviewed representatives from three organizations that have received federal grants to provide technical assistance related to assistive technology.[8] We also spoke with representatives from two nonprofit organizations that support students with disabilities and their families.

To obtain perspectives from families of children with disabilities on accessing assistive technology, we conducted a web-based survey of all 93 Parent Centers across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. Parent Centers, which are funded by Education, provide training and other services to help parents of children with disabilities improve their child’s educational experience. The survey asked Parent Center officials about any challenges they have heard about from families related to assistive technology access and any resources they find useful.[9] We sent the survey to Parent Centers in August 2024 and closed the survey in September 2024.[10] We obtained 82 completed or partially completed surveys from the 93 Parent Centers—a response rate of 88 percent. There is at least one Parent Center in each state. We did not receive complete responses from Parent Centers in three states. In addition, some survey respondents did not answer all questions. We took steps to ensure that our survey collected accurate and consistent information, including pre-testing the survey with selected Parent Centers and making revisions, as appropriate.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Students with disabilities are a diverse group with a wide range of abilities and needs. Examples of disabilities recognized under IDEA include intellectual disabilities and hearing, vision, and speech impairments.[11] Students eligible for special education services under IDEA must have an individualized education program (IEP).[12] An IEP is a written plan developed by a team of school staff, parents, and (when appropriate) the student. It includes components like a statement of the student’s present levels of academic achievement and functional performance, measurable annual goals, and the services and supports needed to attain those goals.

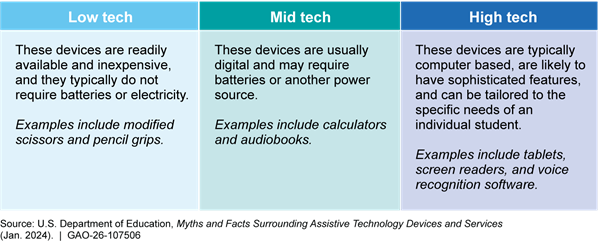

For every student who has an IEP, the student’s IEP team must consider whether the student needs assistive technology devices and services.[13] If the IEP team determines that the student needs assistive technology to receive FAPE, it must be provided to the student at no cost to the parent.[14]

Assistive Technology Devices and Services

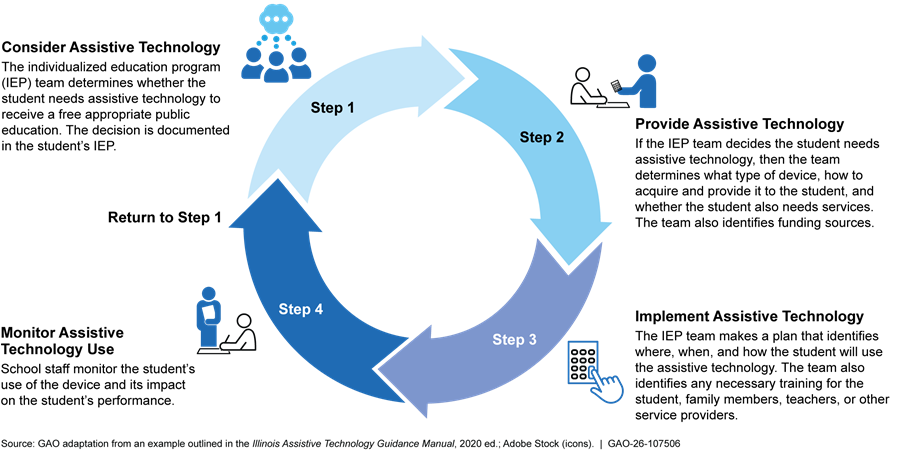

A wide range of assistive technology devices are available, as shown in figure 1.

In addition to assistive technology devices, assistive technology services are typically coordinated by the school district. Under IDEA, these services include:

· evaluating the needs of a student with a disability;

· purchasing, leasing, or otherwise acquiring an assistive technology device;

· selecting, designing, fitting, customizing, adapting, applying, maintaining, repairing, or replacing assistive technology devices;

· providing training or technical assistance to a student or, if appropriate, their family; and

· providing training or technical assistance to professionals or other individuals who provide services to students with disabilities.[15]

School Districts’ Role in Providing Assistive Technology Devices and Services

Various school district staff are involved in providing students with the right assistive technology to meet their needs (see text box).

|

School District Staff Involved in Supporting Students Who Use Assistive Technology · School administrators, such as principals, oversee schools’ special education services, which can include assistive technology. · Special education teachers generally teach in separate special education classrooms or provide instruction alongside teachers in general education classes. They assess students’ learning needs and help develop and implement individualized education programs (IEPs), which can include assistive technology devices and services. They also collaborate with other school district staff and students’ families. · Special education paraeducators (termed “paraprofessionals” in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) assist students with disabilities in one-on-one, small group, and large classroom settings. · General education teachers may support students who use assistive technology devices in a general education setting. · Related service providers, including speech-language pathologists, physical or occupational therapists, school counselors, and school psychologists, provide specialized support and may also assess students’ learning needs and develop and implement IEPs. |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑26‑107506

IDEA requires IEP teams to consider whether a student needs assistive technology devices or services each time the team develops, reviews, or revises a student’s IEP. Further, the IEP team must review a student’s IEP periodically, but not less than once a year, and revise the IEP as appropriate.[16] Figure 2 illustrates how an IEP team might consider, provide, implement, and monitor a student’s use of assistive technology.

Federal Role in Providing Assistive Technology Devices and Services

While most funds and resources for K–12 education come from state and local sources, the federal government also supports states and school districts. Education awards and administers IDEA grants, which funded approximately $14.6 billion in IDEA Part B grants to states in fiscal year 2024. Funding under IDEA Part B helps offset state and local costs associated with providing FAPE. States distribute the vast majority of funds to school districts, which use them to pay for various expenses, including assistive technology devices and services outlined in students’ IEPs. States may set aside IDEA funds for state-level activities which includes assistive technology.[17]

Education also funds technical assistance centers that support educators and families in providing assistive technology to students. For example, the Center on Inclusive Technology and Education Systems (CITES) provides school districts, educators, and families with evidence-based practices and technical assistance to help them use assistive technology. In addition, Education funds 93 Parent Centers (at least one per state), which provide training, information, and other services to the parents of children with disabilities to help improve educational outcomes for their children.

In 2024, Education disseminated a letter and associated guidance about assistive technology for a wide range of individuals including parents, educators, district administrators, and officials at state education agencies.[18] This included a document entitled Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices and Services. According to the document, this information was published to increase understanding about IDEA requirements, dispel misconceptions, and provide examples of how assistive technology devices and services can help children with disabilities.

In addition to Education’s resources, HHS funds programs under the AT Act across all 50 states, four U.S. territories, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.[19] HHS distributes funding through state grants to enhance awareness of, create access to, and increase the use of assistive technology among people with disabilities. These programs provide a variety of direct services on assistive technology (e.g., device loans, repurposing, and training) to individuals of any age, including school-age children.

Selected School Districts Provide Various Assistive Technology to Students but Cited Challenges, Including Limited Staff Knowledge

School District Staff Described a Range of Low- to High-Tech Assistive Technology Devices That Students Use

In the eight school districts we visited, staff—including teachers and related service providers—provided examples of the low- to high-tech assistive technology devices that students with disabilities use in the classroom.

· Low-tech devices. These include:

· Communication cards and visual aids. Staff from one school district said that students use communication cards with images of activities (e.g., snack, bathroom, or break). Students can express what they would like to do by pointing to an image. Staff from this school district said they also use visual schedules (e.g., “first you do this, then you…”), which can help students regulate their behavior by sharing what activities come next.

· Physical supports, such as swivel stools, elevated writing surfaces, and pencil grips. Special education staff from one school said pencil grips are common assistive technology devices used by their students. One special education teacher said four of her 10 students either use a pencil grip or a mechanical pencil for their occupational therapy needs.

· Mid-tech devices. These include:

· Auditory supports, such as microphones for teachers or headsets for students. Staff from one school said teachers use microphones to help students with low hearing. The microphone transmits directly to a hearing aid for one student but can also be amplified to the whole classroom.

· Adaptive switches. Staff from a few school districts described how students use adaptive switches such as battery-operated buttons in the classroom.[20] For example, a related service provider from one school described how a teacher connected classroom electronics, such as the paper shredder and lights, to adaptive switches, which can help students with limited motor skills use them independently.

· High-tech devices. These include:

· Applications on tablets or laptops. Staff from nearly all eight school districts noted that their districts provided all students with tablets or laptops. For students with disabilities, assistive technology sometimes includes specialized apps or features on these devices. For example, staff from one school described students using apps on their devices to have things read aloud.

· Specialized communication devices. Staff from one school district described a student with cerebral palsy who used a communication device they controlled with their eyes to communicate with the staff and their peers. This student previously used a keyboard to communicate but had lost mobility and was no longer able to type.

Figure 3 below depicts some of the devices we observed in a few school districts.

Figure 3: Examples of Low-, Mid-, and High-Tech Assistive Technology Devices Used in Selected School Districts GAO Visited

Staff from all eight school districts stressed the importance of documenting assistive technology in IEPs when provided to students who are served under IDEA. Doing so helps ensure that students continue receiving the assistive technology if they transition to other classrooms or schools. Staff from half of the school districts we visited said that they use general language when writing about assistive technology in IEPs, which can allow for flexibility, for example, in case the assistive technology that the student normally uses breaks or is left at home. This approach enables staff to provide a different device or type of assistive technology so that the student can still work toward their IEP objectives. In addition, certain students receive special education or related aids and services, which can include assistive technology, under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504). See the text box for more information on assistive technology for students under Section 504.

|

Assistive Technology Under Section 504 Students may receive assistive technology under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504). Section 504 plans, while not required, are often created to help schools and school districts meet the requirements of Section 504. In general, a Section 504 plan identifies the regular or special education and related aids and services a student with a disability needs, as well as the appropriate setting in which to receive those services. These plans help ensure that the individual educational needs of the student with a disability are met as adequately as the needs of their peers without disabilities. While Section 504 does not explicitly reference assistive technology as a required consideration, officials from the U.S. Department of Education (Education) said that a student with a disability under Section 504 may need assistive technology to have equal access to the school’s program or activity. They said in this case, the student is entitled to receive the assistive technology. Staff from five of the eight school districts we visited told us that assistive technology is less commonly provided to students under Section 504 plans than it is under individualized education programs (IEPs) for students served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In a few school districts, staff explained that Section 504 plans often provide other accommodations, such as giving students extended time to complete tests. According to officials from Education, students with IEPs and Section 504 plans may both need assistive technology, but the scope and funding associated with IEPs and Section 504 plans are different. Education officials said that if an IEP team or Section 504 team determines that a student needs assistive technology, then the school district must provide it to the student at no cost to the parent. |

Source: GAO analysis of Education guidance and interviews with Education officials, as well as selected district and school staff. | GAO‑26‑107506

Staff from many school districts noted that assistive technology can also support students as they transition out of K–12 education. For example, staff from one school district described how a student presented to the entire high school about how a note-taking device, which digitizes notes and allows for audio recordings, was critical to their education. According to these staff, this tool helped the student go to college. See the textbox for other examples of how assistive technology has helped students in school.

|

Examples from School Staff About How Assistive Technology Helps Students · Once the student got the eye gaze technology and figured out how to use it, he really blossomed. Last year, he was one of the district’s valedictorians and was the class speaker at graduation. Now he is at a 4-year college. He really would not have been able to participate like that in his activities and it would have been very isolating for him without the assistive technology serving as his voice. He will probably be writing the legislation and advocating for assistive technology someday. Without the right device, that could not have happened. –School district official · In sixth grade, one of our students was only able to communicate verbally by saying “yes” or “no” and otherwise relied on a communication device. Through special education support and continued use of the communication device, the student—now an eighth grader—expresses more words verbally and uses more facial expressions. The student has become an active member of the dance team and more social with her peers –Special education teacher at a middle school · One of the older students I work with is in learning support classes and has a first grade reading level. However, the student is good with hands-on projects and wants to attend trade school. Implementing a software application that takes pictures and reads aloud to the student has been life changing. It will hopefully enable the student to go to trade school. –Related service provider at a middle school · Certain students in the middle school get a visual schedule that has a picture of the teacher on it next to the room number, time, and subject. These visual schedules have helped avoid a lot of meltdowns in the hallway because the students know where to go and once they get there they can focus on the content. –School district officials |

Source: GAO analysis of interviews from eight selected school districts. | GAO‑26‑107506

Note: Some descriptions above were slightly modified for clarity and brevity.

School District Staff Identified Challenges Related to Staff, Student, and Family Knowledge About Assistive Technology

Staff from all eight selected school districts identified limited knowledge about assistive technology as a challenge that sometimes affects their ability to provide assistive technology to students with disabilities.[21] For example, they described:

· Limited awareness of available assistive technology. Staff from all eight school districts we visited cited cases in which they or their colleagues were unaware of the range of assistive technology that could assist students with disabilities. For example, staff from one school district said they are only aware of the assistive technology they use and want to learn more about other possible devices and how they could serve students. In many school districts we visited, staff said that teachers often only think of high-tech devices and may not consider low-tech devices to be assistive technology. This may result in students not having simple solutions that could meet their individual needs. Officials from the four state education agencies we interviewed also said limited awareness about the range or types of available assistive technology is a challenge for educators in their state.

We also heard from related service providers in many districts that they are unaware of some assistive technology options or how to use them, which is particularly challenging because they often lead assistive technology implementation in schools. For example, in one school district, a speech-language pathologist told us that they and their colleagues are expected to be experts on communication devices but have varying experiences using it. Another speech-language pathologist said she had only taken one class on communication devices in graduate school and did not feel adequately trained. Officials from one state’s AT Act Program said that graduate programs for related service providers may not effectively train them on assistive technology.

Rapidly changing technology can exacerbate challenges school district and school staff face in learning about available assistive technology. For example, staff from one school said they wanted to know if there was new or updated software that could better help a student who is non-speaking, but staff did not have time to learn about new devices. This limited knowledge of changing assistive technology may result in staff relying only on the assistive technology that they are aware of, regardless of whether it is the best option for a particular student.

· Negative attitudes. Staff from many of the eight school districts said some of their colleagues are unwilling to learn how to use assistive technology devices or believe assistive technology unfairly benefits students with disabilities. Special education teachers from one school said this can sometimes result in other school staff not ensuring students use assistive technology even if it is in their IEP. For example, staff from one school district described needing to convince colleagues responsible for student testing that assistive technology was not an unfair advantage, but rather a way to level the playing field. Officials from CITES said that some educators think assistive technology is “cheating.” For example, these officials expressed concerns about high denial rates for students requesting text-to-speech accommodations. Specifically, they cited educators’, administrators’, and families’ mindsets, compounded by misconceptions and a lack of training and coaching on the importance of this assistive technology and how to use it.

Special education teachers from one school said that broad misconceptions about students with disabilities can result in delays in students receiving the assistive technology they need. For example, these teachers described several students who in their view could have been in general education classes but instead remained in special education classes and did not communicate until a later age because they did not receive assistive technology until in high school. Misconceptions such as these run the risk of interfering with a student’s access to FAPE.

Staff from many school districts also discussed how students themselves sometimes have limited awareness about assistive technology or attitudes that hinder its use. For example, school staff described an instance in which a student had been using a talk-to-text computer application in a noisy room and had not realized that bringing the microphone closer to their mouth would capture the audio better. See the text box for examples of students’ use of assistive technology, according to school staff.

|

Examples from School Staff About Students’ Use of Assistive Technology · One challenge is that students have assistive technology but don’t use it. This may be because they’re embarrassed to, for example, be the only one in the class using headphones. Students who don’t want to use their assistive technology in class also won’t use it on state assessments or tests like the SAT or ACT. This is frustrating for educators. We always want what’s best for students, but can only “lead the horse to water,” not force the students to use the resources they’re given. –General education teacher at a high school · Students do not like to feel singled out by using assistive technology, such as when wearing headphones to use text-to-speech functions. To overcome this challenge, the teachers have tried to get all students headphones so that a student who needs headphones as assistive technology does not feel as stigmatized using them. –Special education teacher at a middle school · In the last 5 to 10 years, the district’s approach to technology has shifted tremendously by getting all students access to tablets. Ten years ago, when a student needed assistive technology, that student may have been the only one in the classroom using a computer [creating a stigma]. There are still children who do not want to use assistive technology that makes them look different, but that is less of an issue now with technology embedded into the classroom for all students. –Related service provider at a middle school |

Source: GAO analysis of interviews from eight selected school districts. | GAO‑26‑107506

Note: Some descriptions were slightly modified for clarity and brevity.

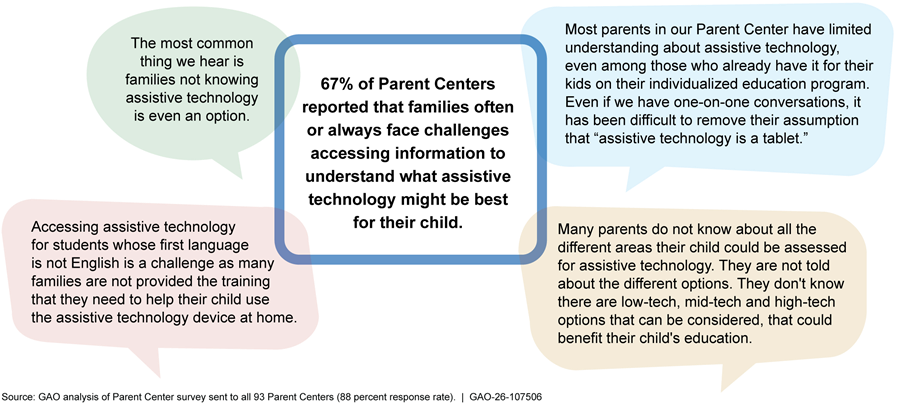

Families of students with disabilities may also have limited knowledge about assistive technology, according to staff from nearly all of the school districts we visited and two-thirds of the Parent Centers that responded to our survey. For example, staff from one school said families are often interested in getting a device for their child and assume the child will know how to use it on their own. However, in some instances, families are not sufficiently trained on how to use a device, and as a result the child does not use the device at home. Parent Centers—technical assistance centers funded by Education—shared similar observations (see fig. 4). For example, 67 percent of Parent Centers that responded to our survey indicated that when discussing assistive technology, families always or often reported challenges accessing information about what assistive technology may be best for their child.

Note: Some descriptions were slightly modified for clarity and brevity.

Staff from All Eight School Districts Described How Broader Challenges, such as Staffing Issues, Make Providing Assistive Technology More Difficult

Staff from all eight selected school districts described how broad challenges pertaining to public education adversely affect their ability to provide assistive technology to students with disabilities. These include (1) insufficient time and opportunities for training, (2) staffing issues, (3) technology issues, and (4) funding constraints.

Insufficient Time and Opportunities for Training

Staff from nearly all school districts—including teachers and related service providers—said that they had little to no time for training on assistive technology.[22] For example, in a few districts, related service providers said they do not have enough time for such training. One speech-language pathologist we spoke with said their heavy workload does not leave enough time for training during contracted hours. Instead, they typically participate in trainings during their personal time. In another school district, a speech-language pathologist told us that they have to prioritize training on other areas of speech they consider more critical for their job. When they need to provide assistive technology to students, the speech-language pathologist said they are “flying by the seat of one’s pants.”

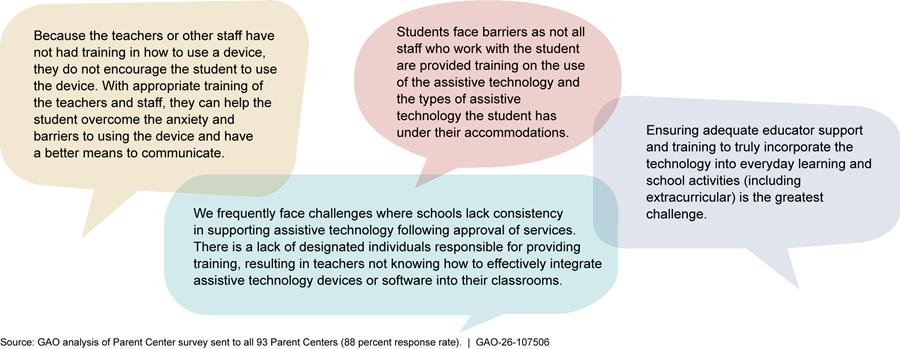

In addition to insufficient time for training, we heard from staff in all eight school districts that opportunities for training on assistive technology are rare or nonexistent, particularly for general education teachers. For example, in one school district, general education teachers and paraeducators said they often did not receive assistive technology training but that it could better help them support students who use assistive technology. Officials from CITES also identified limited training on assistive technology as a primary challenge, noting that there are few educators or families with the appropriate training and coaching on assistive technology.

Students’ and families’ limited knowledge about assistive technology may be partly due to special education teachers or related service providers having limited time to provide such training. For example, staff from one school district said because teachers do not have enough time to train students on how to use devices, the teachers have asked students to train other students on how to use assistive technology. Without receiving sufficient training, students may not use their devices.

Parent Center staff who responded to our survey also described challenges related to school staff not having the necessary assistive technology training (see fig. 5).

Note: Some descriptions were slightly modified for clarity and brevity.

Staffing Issues

Staff from nearly all of the eight school districts and all four state education agencies we spoke with said that staffing issues, such as shortages, turnover, or difficulty hiring qualified staff, contributed to challenges providing assistive technology.[23] For example, staff who take on additional responsibilities to fill staffing gaps may have less time to learn about assistive technology, including the range of available devices and any new devices. Staff from one school district also said that high turnover results in having to constantly train new staff on assistive technology.

Staffing issues, particularly the availability of related service providers, could mean that districts have limited expertise on assistive technology. For example, staff from one school we visited said that there were not enough occupational therapists in the school district. As a result, the occupational therapist that serves their school was unable to visit for several weeks to identify necessary assistive technology for a student with a sensory processing issue, delaying the student’s access to needed assistive technology.

Technology Issues

Staff from all eight school districts described broader technology challenges that affect their ability to provide assistive technology to students. These include ensuring that assistive technology devices are compatible with other school district technology, providing replacements when devices break, ensuring devices are charged and usable, and keeping devices and software up to date. For example, staff from one school district said they constantly replace tablets because they break frequently, which is costly. Staff from another school district said the district’s tablets are outdated and incompatible with current assistive technology software applications.

Staff from all eight school districts said that it can be challenging to ensure students have access to up-to-date or functioning devices. For example, staff from one school described how a student who is nonspeaking did not have access to their communication device for about 2 months after the school year began. The student was required to turn the device in before summer break, and it was not returned to them promptly at the beginning of the school year. The staff from this school said that students can regress when they must go long periods without their devices and routines. See the text box for additional examples school staff provided of the educational or emotional effects when students do not have access to their assistive technology.

|

Examples from School Staff About How Technology Disruptions Affect Students · Sometimes technology stops working, and staff rely on the information technology department to fix it. That can mean that a student does not have access to or cannot fully use their assistive technology for a few days which can lead to lost learning time. Even small disruptions can have big effects on a student being engaged in the learning. –School district officials · The laptops the school uses are not great – it is common that buttons are broken, or voice commands do not work. Sometimes it can take days to get them fixed. When a device is sent out to be fixed, the student is provided with a loaner device, which sometimes do not have the same features. Students get really frustrated when they do not have access to their assistive technology. There have been instances where students get so frustrated they hit the tablet or throw it. –General education teachers and paraprofessionals from a high school · When students cannot communicate, they get frustrated and act out. For example, one teacher had a laptop thrown at their head. When technology does not work, the teachers try to use picture communication techniques, but if the student is used to communicating in a different way, then that does not always work. –Special education teachers from an elementary school |

Source: GAO analysis of interviews from eight selected school districts. | GAO‑26‑107506

Note: Some descriptions above were slightly modified for clarity and brevity.

Funding Constraints

School districts must provide assistive technology to students when it is in their IEP, but AT Act Program officials from all four states we visited and staff from nearly all school districts described challenges accessing sufficient funding for assistive technology. These challenges can affect school districts’ ability to provide the most appropriate assistive technology for students’ individual needs. For example, staff from one district said that when they are unable to provide high-tech devices, they sometimes use low-tech devices instead (e.g., picture schedules, communication boards). This may only partially meet the student’s needs. Staff from this school district also said they struggle to keep software applications up to date because the school district must repurchase the license every year. In another school district, staff said that certain devices can cost $20,000–$40,000. They said that sometimes the devices are paid for by a family’s insurance, but if not, the district will figure out a way to obtain the device, which is not “a drop in the bucket” for them. In two school districts we visited, staff said they had recently begun using Medicaid to pay for some assistive technology after learning about this funding source.[24] We also learned that teachers sometimes order their own low-tech assistive technology from an online retailer or use crowd-sourcing donation websites.

Selected School Districts Sometimes Formed Assistive Technology Teams and Used External Resources, Helping to Mitigate Challenges

School Districts That Formed Assistive Technology Teams Found They Improved Coordination

Four of the eight school districts we visited established assistive technology teams, which officials said helped improve coordination and collaboration and build knowledge and capacity related to assistive technology.[25] The teams generally comprised district-level special education staff (e.g., assistive technology coordinators or special education directors) and related service providers (e.g., speech-language pathologists and occupational therapists). All four assistive technology teams we spoke with provided a range of services to support schools, such as (1) developing standardized processes for identifying and obtaining assistive technology; (2) providing training, resources and consultations; and (3) coordinating with information technology (IT) departments.

Developing Standardized Assistive Technology Processes

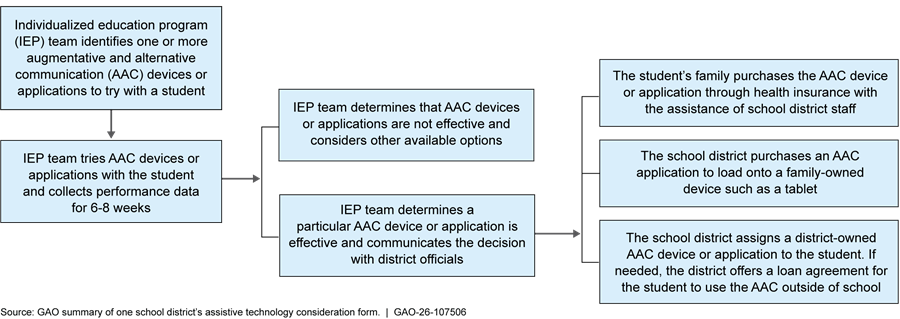

Assistive technology teams in all four districts helped develop or expand school districts’ standardized assistive technology processes, including how to identify the best assistive technology for students’ needs, document assistive technology use in students’ IEPs, and acquire assistive technology. For example, the assistive technology team in one school district developed a consideration form. When school staff fill out this form, they receive an automated list of relevant assistive technology to help them consider and identify devices that will meet students’ needs and that contains links to resources. The assistive technology team can then assist school staff with acquiring devices and ensuring that teachers and students know how to use them. Another district’s assistive technology team created a flowchart laying out the process for school staff to use when considering assistive technology for students with communication needs (see fig. 6 for a summary of that flowchart).

Note: AAC devices provide a means of communication for students who are unable to speak or have difficulty with speech and language skills. AAC devices range from low-tech options such as writing or pointing to symbols to high-tech options such as a computer with applications a person uses to generate speech.

These types of processes can help mitigate the challenges of staffing issues and limited knowledge by helping school staff learn about and provide assistive technology to students. For example, officials from one school district said standardized processes helped some teachers build the knowledge necessary to identify assistive technology for students. Officials from another district said their assistive technology team helped the school district build sustainable assistive technology processes that could help maintain assistive technology services when there is staff turnover.

Of the four school districts we visited that did not have assistive technology teams, one had assistive technology standardized processes such as a guide for considering assistive technology. Officials in this rural school district emphasized the importance of developing such processes because the school district had limited staff with many responsibilities. In the other three districts, officials told us that school staff—such as related service providers and IEP teams—typically considered and implemented assistive technology for students. In one of these three districts, officials noted that standardized processes were needed, and in another district officials said they were planning to develop tools to help staff consider assistive technology needs.

Providing Training, Resources, and Consultations

All four assistive technology teams we spoke with provided training, resources or consultations to school staff. Two assistive technology teams said they provide training to help school staff learn about standardized assistive technology processes. For example, one assistive technology team said they use a “teach, model, coach, review” approach to train school staff on assistive technology processes. This means that they (1) teach school staff strategies to provide assistive technology, (2) model those strategies, (3) coach school staff through potential scenarios, and (4) make plans to review progress with them. The other assistive technology team said they presented at school staff meetings to ensure the staff were aware of these processes.

In addition, assistive technology teams created resources, including internal websites or tools. The internal websites compiled process documents and other information, such as catalogs of available assistive technology devices and guides on how to use specific devices. One team also created and periodically updated toolboxes containing low-tech devices for each school in the district (see fig. 7). School staff could try these devices with students before considering higher-tech devices.

Three assistive technology teams said they consulted with school staff about individual students or how to navigate assistive technology processes. For example, one team noted that school staff know students’ needs best but may not know what assistive technology could address those needs. In those instances, school staff consult with the assistive technology team to learn what devices are available in the school district. The assistive technology team might also help school staff use data to monitor whether chosen devices were effective for students.

Coordinating with IT Departments

In three school districts, assistive technology teams coordinated with their IT departments to address technology challenges. For example, special education staff from one school district told us their assistive technology team worked with the district’s IT department to improve how the district buys and manages assistive technology devices. To do so, the special education and IT departments clarified their roles and responsibilities related to assistive technology. Then, the IT department began managing all high-tech devices in the school district, and special education staff were given the ability to install specialized assistive technology applications on those devices. Prior to this collaboration, the two departments owned and managed separate inventories of high-tech devices, so it was difficult for special education staff to install specialized applications for the students who needed them. In addition, the two departments worked together to make it simpler to purchase assistive technology.

All Eight School Districts We Visited Used Federal, State, or Regional Resources, such as External Training, Expert Consultation, and Lending Libraries

District officials from all eight school districts we visited said they used assistive technology resources from federal, state, or regional sources to train school staff or provide assistive technology to students. This helped to mitigate the challenge of limited staff knowledge about assistive technology. For example, district officials reported using resources from federally funded organizations, such as:

· Assistive Technology Act (AT Act) Programs,

· Parent Training and Information Centers,

· CITES, and

· the IRIS Center.[26]

In addition, district officials said they used resources from their state departments of education and sometimes from regional educational service agencies. While the structure of these agencies varies, regional educational service agencies provided specialized services, such as special education training to school districts within a certain geographic area.

District officials frequently described using the following external resources: (1) training for school staff, (2) expert consultations on how to use assistive technology, and (3) assistive technology lending libraries to borrow devices for students. School districts varied in how they accessed these resources. For example, officials from one district said they used lending library resources from their state’s AT Act Program and training from the state department of education. Officials from another district said they used training, consultations, and the lending library from their regional educational service agency.

External Training and Expert Consultations

District officials we spoke with frequently cited leveraging external training and expert consultations to support students’ use of assistive technology. Officials from nearly all districts we visited said they received assistive technology training from external sources such as state departments of education or regional educational service agencies. For example, three states we visited offered training to school staff on topics such as the definition and importance of assistive technology and how to use specific devices. All four states also maintained digital resources for schools and districts, including guidance documents and recorded trainings. School districts used trainings from external sources when they did not have their own assistive technology training. Officials from a few districts we visited also reported consulting with external assistive technology experts to help address individual student cases. For example, officials from one district said the school district did not have the expertise to determine how to purchase and use high-tech communication devices. When necessary, they brought in experts from a regional educational service agency to do so. Officials from another district said they consulted with their state’s AT Act Program when they had questions, such as about text-to-speech devices. Leveraging external training and expert consultations on assistive technology can help mitigate staffing issues and limited knowledge among district staff by building awareness of assistive technology within school districts and instructing school staff on specific devices.

Lending Libraries

Staff from nearly all eight school districts we visited said their school district used assistive technology lending libraries to try out assistive technology devices with students. Lending libraries in the states we visited were housed in regional educational service agencies, state departments of education, or federally funded AT Act Programs. They typically loaned assistive technology devices for up to 6 weeks. According to officials from a few districts, when a school district borrowed an assistive technology device for a student to try, the school district collected data on its effectiveness. This data can be used to determine whether a similar device should be purchased for the student.

Using lending libraries sometimes helped school districts mitigate issues with limited funding, but district officials still reported challenges. For example, a related service provider from one district said the lending library was helpful when considering expensive, high-tech devices. The provider could have students try these high-tech devices and collect data showing which devices were most effective at helping students meet their individual IEP goals before the school district invests a large sum of money in assistive technology that may not be a good fit for a student. Despite this, district officials said they sometimes still had to purchase lower-cost assistive technology alternatives due to limited funding.

Other Resources

Officials from the districts we visited shared other examples of external resources they used to learn about and provide assistive technology to students.

· CITES and other federally funded centers. Half of the school districts we visited used resources from CITES, such as incorporating aspects of the CITES framework or using CITES resources to stay informed on current technology.[27] In addition, district officials reported using resources from other federally funded organizations, such as the IRIS Center, National Instructional Materials Access Center, and Parent Training and Information Centers.

· Assistive technology conferences. Staff from half of the school districts we visited noted that assistive technology conferences can be helpful resources. For example, assistive technology team members from one district attended two annual conferences and shared the information they learned with the rest of the team.

· Information-sharing groups. Officials from a few districts described groups that gather to share information. For example, related service providers from one district participated in an assistive technology community of practice that invited speakers to share assistive technology-related activities from other school districts and states. Officials from two other districts found monthly assistive technology speaker sessions hosted by their state’s AT Act program to be helpful sources of information about assistive technology.

· Assistive technology device vendors. Officials from a few districts we visited said they partnered with private vendors for discounts or training on assistive technology devices. For example, officials from one district said vendors sometimes provided free trial periods with assistive technology devices (i.e., the district may use a device for free for 6 months).

· University programs. Officials from one of the districts described a program with a nearby university in which graduate students provided support to the school district as it related to communication devices. As part of the program, graduate students were trained on communication devices and then assigned to work with individual families that signed up for the program.

|

Selected States’ Use of Assistive Technology Resources Similar to school districts, officials from the four state departments of education we interviewed told us they used assistive technology resources—such as guidance documents, webinars, and conferences—from external sources. Since school districts used resources from the state departments of education, the information state departments obtained could then be passed on to school districts. For example, officials from three of the four departments said they developed training or other resources for school districts based on the U.S. Department of Education’s 2024 Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices and Services guidance. Officials from one of those departments said that including federal guidance in their training gave credibility to the training content. Officials from the fourth department said they directly shared the guidance with school districts in their state because it provided an easily understandable summary of assistive technology requirements. Department officials also described consulting other organizations to learn about assistive technology or ensure department guidance was accurate. For example, officials from one department said they consulted other agencies in their state to learn about available assistive technology and to consider guidance that would be helpful to school districts. Officials from another department described having disability-related organizations review the department’s assistive technology documents for accuracy. In addition, officials from two departments said they are part of a community of practice focused on assistive technology for education professionals. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from four state education agencies and the U.S. Department of Education. | GAO‑26‑107506

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to Education and HHS for review and comment. Education provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. HHS did not provide any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Education, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at nowickij@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Sincerely,

Jacqueline M. Nowicki, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

GAO Contact

Jacqueline M. Nowicki, nowickij@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Barbara Steel (Assistant Director), Liz Spurgeon (Analyst in Charge), Alexia Lipman, Ian Pearson, and Jessica L. Yutzy made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Brittni Milam, David Forgosh, James Rebbe, Jocelyn Kuo, Mimi Nguyen, Rebecca Sero, and Stacia Odenwald.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]20 U.S.C. § 1401(1)(A).

[2]20 U.S.C. §§ 1401(9), 1412(a)(1)(A).

[3]U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, Condition of Education (2024).

[4]We selected school districts to reflect variation in urbanicity, percentage of students with disabilities, and the presence of known assistive technology initiatives as identified by state officials or representatives from national organizations. Within each state, we initially selected one school district based on recommendations from state or national organizations. We selected the second school district based on proximity to the initial district and to ensure that our selected districts across all four states reflected variation in the aforementioned characteristics. We then selected schools that provided a variety of grade levels (e.g., elementary school, middle school).

[5]In this report, “district officials” refers to staff only at the district-level (e.g., Directors of Special Education). “Staff from school districts” includes school staff (e.g., teachers) and district officials.

[6]Most states have regional educational service agencies that coordinate professional development, use of funds, and information sharing across school districts within regions of their states. These agencies also assist schools in providing specialized education services. District officials we spoke with in Minnesota, Texas, and Pennsylvania referenced using resources from regional educational service agencies, so we met with staff from one regional education service agency within each of those states.

[7]The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funds programs under the AT Act across all 50 states, four U.S. territories, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

[8]We spoke with representatives from two Education-funded organizations—the Center on Inclusive Technology and Education Systems (CITES) and the Center for Parent Information and Resources—as well as one HHS-funded organization—the National Assistive Technology Act Technical Assistance and Training Center.

[9]Specifically, we asked about how often Parent Centers discussed assistive technology with families, how frequently parents reported various challenges related to assistive technology to Parent Centers, how access to assistive technology varied among students with disabilities, what information sources Parent Centers found helpful in assisting families with assistive technology, and whether there are additional resources that Parent Centers would find helpful to assist families with assistive technology.

[10]Due to a technical error, one Parent Center survey was collected in August 2025.

[11]20 U.S.C. § 1401(3).

[12]20 U.S.C. § 1414(d).

[13]34 C.F.R. § 300.324(a)(2)(v), (b)(2).

[14]20 U.S.C. § 1412(a)(1)(A).

[15]20 U.S.C. § 1401(2).

[16]34 C.F.R. § 300.324(b)(1)(i).

[17]34 C.F.R. § 300.704(b)(4)(iv).

[18]See U.S. Department of Education, Dear Colleague Letter on the Provision of Assistive Technology Devices and Services for Children with Disabilities Under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 22, 2024), and U.S. Department of Education, Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices and Services (Jan. 2024).

[19]In addition to the AT Act Programs, HHS administers Medicaid, which finances health care for certain individuals with low incomes or high medical expenses. HHS also administers the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which does so for certain uninsured children whose household incomes are too high for Medicaid eligibility but may be too low to afford private insurance. Both are federal-state programs. In some states, Medicaid or CHIP may be used to pay for individualized services required under a student’s IEP if they are Medicaid-covered services, including assistive technology.

[20]Throughout this report, we use the following qualifiers to quantify responses: “a few” refers to responses from two or three school districts, “half” refers to responses from four school districts, “many” refers to responses from five or six school districts, and “nearly all” refers to responses from seven school districts.

[21]We did not examine states’ or school districts’ compliance with IDEA and FAPE as part of this review.

[22]For more information on challenges related to insufficient training or professional development time in special education, see GAO, Special Education: Education Needs School- and District-Level Data to Fully Assess Resources Available to Students with Disabilities, GAO‑24‑106264 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2024).

[23]We have previously reported on staffing shortages in K–12 education. See GAO, K‑12 Education: Education Should Assess Its Efforts to Address Teacher Shortages, GAO‑23‑105180 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 27, 2022); GAO‑24‑106264; and GAO, STEM Education: Selected Federal Initiatives, Challenges, and Approaches to Supporting Rural Populations, GAO‑25‑107371 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2025).

[24]Medicaid program eligibility and coverage varies by state and sometimes allows school districts to bill Medicaid directly. We heard from staff in a few districts that having Medicaid or other insurance pay for assistive technology can be beneficial because, for example, it allows the student or family to own the device and have the device covered if it breaks. In contrast, staff from one district said that when the district purchases assistive technology, the district owns the device. If the student leaves the district, the device may not follow the student.

[25]Three of the districts with assistive technology teams were recommended to us by state officials as being leaders in assistive technology. The fourth recommended district did not have such a team but instead had standardized AT processes in place.

[26]The IRIS Center develops and disseminates online resources about evidence-based instructional and behavioral practices to support all students, including those with disabilities.

[27]The CITES framework provides evidence-based guidance to establish assistive technology and other inclusive technology practices in five areas: leadership, infrastructure, teaching, learning, and assessment. Center on Inclusive Technology & Education Systems, CITES Framework Overview & Essential Questions (2024).