RESEARCH SECURITY

Agencies Should Assess Safeguards Against Discrimination

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Hilary M. Benedict at BenedictH@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

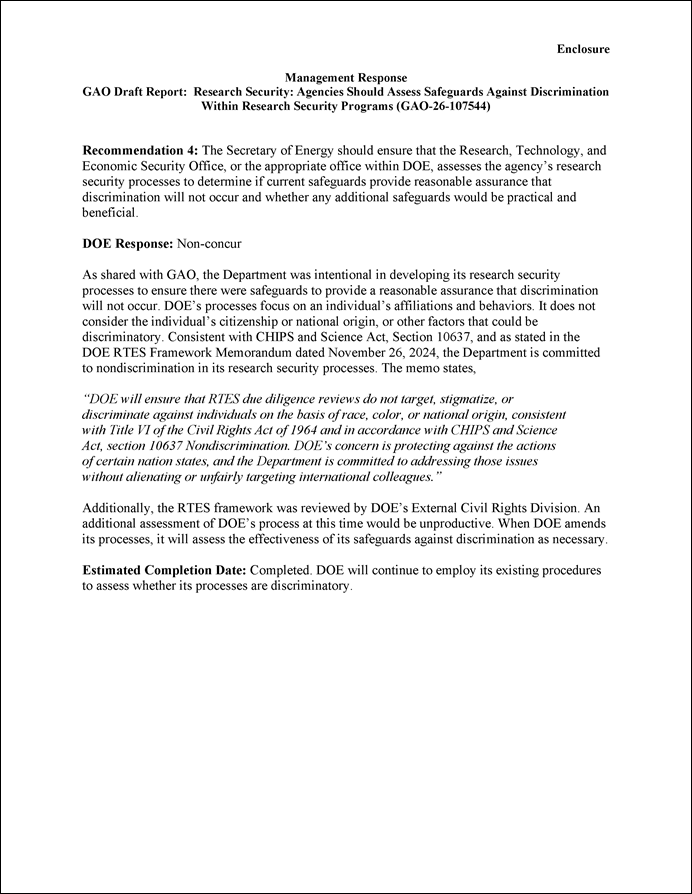

The federal government gives grants to individual scientists and groups of scientists through their respective research institutions, supporting both basic and applied research. Federal funding agencies must have research security policies in place to ensure that such research is free of improper foreign influence. Such influence includes, for example, malign talent recruitment activities by foreign governments or misappropriation of research findings. Agencies are required to carry out research security policies in a manner that does not discriminate against scientists based on their race, ethnicity, or national origin. The Departments of Defense (DOD) and Energy (DOE), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and National Science Foundation (NSF) have applied safeguards to varying degrees in their research security programs to help prevent discrimination.

|

|

Transparent improper foreign influence review processes |

Collection and use of demographic data to assess agency processes |

Multiple levels of review in improper foreign influence reviews |

Training agency staff in non-discrimination in improper foreign influence reviews |

Leadership commitment to non-discrimination in improper foreign influence reviews |

|

Department of Defense |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◒ |

◯ |

|

Department of Energy |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◒ |

● |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◯ |

◯ |

|

National Institutes of Health |

● |

◒ |

● |

◯ |

● |

|

National Science Foundation |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

● |

● |

● = Fully adopted ◒ = Partially adopted or plan in development; ◯ = Not adopted

Source: GAO analysis of selected agencies’ documents and interviews. | GAO-26-107544

While NASA and NSF documented their processes for identifying and addressing improper foreign influence, they have not documented their risk mitigation processes. By clearly documenting risk mitigation processes, agencies can create shared expectations with research institutions and researchers about how these processes are implemented fairly and without discrimination. Additionally, DOD, DOE, NASA, NIH, and NSF have not assessed their research security processes to determine whether the safeguards the agencies have in place provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur. By assessing their current safeguards, agencies can provide greater assurance that discrimination will not occur and may identify additional safeguards appropriate to the agency.

Why GAO Did This Study

As a global leader in scientific research, the U.S. has benefited from recruiting international talent and international collaborations. However, concerns have grown about improper foreign influence in federally funded research.

While agency identification of improper foreign influence is critical to preventing fraud in taxpayer funded research, some stakeholders raised concerns that agencies were discriminating against certain demographic groups when reviewing grants.

GAO was asked to examine whether federal agencies ensure that research security reviews are free from discrimination. This report assesses the extent to which selected agencies have implemented safeguards to prevent discrimination in research security processes.

GAO selected the five agencies that funded the highest amounts of extramural research and reviewed agency documents and published literature. GAO also performed statistical analysis on data obtained from one agency to assess differences among improper foreign influence cases and interviewed agency officials and representatives of universities and civil society organizations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations. NASA and NSF should document their risk mitigation processes. All five agencies should assess their research security processes to determine if their safeguards reasonably ensure nondiscrimination. NASA and NIH agreed, and NSF said it would consider the recommendation. DOE disagreed, noting it designed its process to ensure nondiscrimination. GAO believes that an assessment could yield benefits. DOD did not comment.

Abbreviations

|

DNI |

Director of National Intelligence |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

NSF |

National Science Foundation |

|

NSPM-33 |

National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 |

|

NSTC |

National Science and Technology Council |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OSTP |

Office of Science and Technology Policy |

|

SECURE |

Safeguarding the Entire Community of the U.S. Research Ecosystem |

|

R&D |

research and development |

|

TRUST |

Trusted Research Using Safeguards and Transparency |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 21, 2026

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The Honorable Judy Chu

House of Representatives

The Honorable Grace Meng

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

House of Representatives

As a global leader in scientific research, the U.S. has long fostered and benefited from the recruitment of international talent and international collaborations. According to several studies, contributions from U.S. scientists of diverse backgrounds and from foreign researchers have made the U.S. a science and technology powerhouse.[1] However, there are concerns about foreign entities attempting to improperly influence U.S.-based researchers whose scientific work is funded by federal agencies. For example, the November 2024 Brief Summary of NIH Foreign Interference Cases—published by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Office of Extramural Research within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—showed NIH received allegations of improper foreign influence involving over 600 scientists from 2017 to 2024.[2]

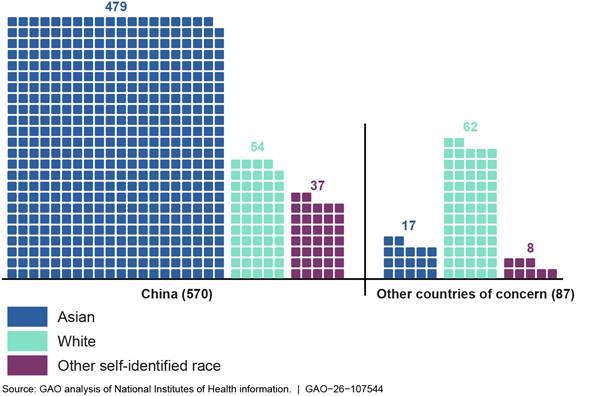

According to White House documents and agency data, China is the primary country of concern behind most cases of improper foreign influence. For example, according to NIH data, China was involved in 570 of the 657 NIH allegations of improper foreign influence as of November 2024. Some Chinese improper foreign influence programs may target ethnically Chinese researchers living in the U.S., potentially increasing the risk to those individuals of improper foreign influence allegations. While efforts to ensure the security of research by countering improper foreign influence are important, universities, civil society organizations, and others have raised concerns that such efforts may unfairly target scientists of Chinese or Asian descent.

You asked us to examine whether federal agencies ensure that research security reviews are free from discrimination. In this report, we assessed the extent to which selected agencies have implemented safeguards to prevent discrimination in research security processes.

For the purposes of this review, we selected the five agencies that funded the highest amounts of extramural research (i.e., research performed at universities, medical centers, and other research institutions)—the Departments of Defense (DOD) and Energy (DOE), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NIH within HHS, and the National Science Foundation (NSF). These five agencies distributed over 94 percent of extramural federal funding for scientific research in fiscal year 2023—the most recent data available at the beginning of our review. To identify safeguards to prevent discrimination and assess agencies’ implementation of these safeguards, we reviewed agency documents and published literature and interviewed agency officials, representatives from universities, and representatives from civil society organizations. We also performed statistical analysis on data obtained from NIH to assess differences among improper foreign influence cases. Appendix I provides further information about our methodology. Appendix II presents details on and findings from our statistical analysis of the NIH data.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The federal government awards grant funding to individual scientists and groups of scientists through their respective research institutions.[3] This federal funding supports both basic and applied research. According to previous GAO work, the grants process begins with the federal agency publishing a call for grant applications, which research institutions, such as colleges and universities, can apply for.[4] This type of federally funded research can be used for basic science such as research attempting to discover the genetic cause of a disease, or for applied research, such as targeted improvements in cybersecurity. Over the decades, the federal government’s funding of research has been central to the development of novel scientific, technological, and medical breakthroughs. For example, a 2018 study found that NIH federal funding for basic sciences contributed to the development of all new drugs approved by the Federal Drug Administration from 2010-2016.[5]

Since 2018, federal research funding agencies have examined numerous cases of improper foreign influence. For the purposes of our review, the term “improper foreign influence” refers to the misappropriation of R&D funding and findings, to the detriment of national and economic security, related violations of research integrity, and foreign government interference. Such activities could include participation in a malign foreign talent recruitment program by a U.S. funded researcher, which could potentially lead to compromised research results that benefit a foreign adversary. “Improper foreign influence risk” refers to the increased likelihood that improper foreign influence will happen on a research project. Such risks could include researchers having financial ties or extensive research collaborations with foreign entities of concern.

Improper foreign influence cases led to some researchers losing their funding, experiencing other administrative outcomes, or receiving criminal convictions. Agency identification of improper foreign influence is critical to preventing fraud, waste, or abuse of taxpayer funded research; however, some reports raised concerns that agencies were discriminating against certain demographic groups during their grant reviews. For example, a published article identified racial discrepancies in grant-funding rates at the NSF.[6]

Several laws and policies require agencies to implement research security policies that are free of discrimination:

· In January 2021, the White House issued National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 (NSPM-33), directing agencies to develop standard research security policies consistent with privacy, civil rights, and civil-liberties laws and policies.[7] The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued NSPM-33 implementation guidance in January 2022 and July 2024.[8]

· The law commonly known as the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 contained agency authorities to conduct risk assessments and research security provisions, including addressing malign foreign talent recruitment program participation, “in a manner that does not target, stigmatize, or discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity or national origin.”[9] The act defines a malign foreign talent recruitment program as a program, position, or activity that offers one of several listed forms of compensation in exchange for an individual’s engaging in one or more listed activities, such as the unauthorized transfer of intellectual property to an entity affiliated with a foreign country, where such program is sponsored by a foreign country of concern or entity located therein or appearing on certain identified lists. In this context, a foreign country of concern refers to China, North Korea, Russia, Iran, or any other country determined to be one by the Secretary of State.[10]

· Additionally, requirements for federal grants and cooperative agreements provide that agencies must manage and administer these awards in a manner ensuring that associated programs are implemented in full accordance with the U.S. Constitution, applicable statutes, and regulations, including provisions prohibiting discrimination.[11] Similarly, regulations for federal contracts require that government business be conducted with complete impartiality and with preferential treatment for none, except as authorized by statute or regulation.[12]

Agencies Have Implemented Safeguards to Prevent Discrimination but Have Not Assessed Their Effectiveness

Our review of relevant laws, regulations, and agency processes identified five safeguards that could help agencies ensure their processes do not target, stigmatize, or discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin. We found that the five agencies in our review have generally implemented some or all of the five safeguards we identified but the agencies have not assessed their effectiveness. While each agency has some safeguards in place, agencies vary as to which safeguards have been implemented and how fully agencies have adopted these safeguards (see table 1).

Table 1: Extent to Which Selected Agencies Have Adopted Safeguards to Prevent Discrimination While Addressing Improper Foreign Influence

|

|

Transparent improper foreign influence review processes |

Collection and use of demographic data to assess agency processes |

Multiple levels of review in improper foreign influence reviews |

Training agency staff in nondiscrimination in improper foreign influence reviews |

Leadership commitment to nondiscrimination in improper foreign influence reviews |

|

Department of Defense |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◒ |

◯ |

|

Department of Energy |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◒ |

● |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

◯ |

◯ |

|

National Institutes of Health |

● |

◒ |

● |

◯ |

● |

|

National Science Foundation |

◒ |

◯ |

● |

● |

● |

● = Fully adopted ◒ = Partially adopted or plan in development; ◯ = Not adopted

Source: GAO analysis of selected agencies’ documents and interviews. | GAO‑26‑107544

Most Agencies Documented Their Research Security Processes, but Gaps Remain

Documentation and transparency can safeguard against discrimination by establishing shared expectations among agencies and stakeholders for how research security policies and processes will be implemented. The five agencies in our scope—DOD, DOE, NASA, NIH, and NSF—vary in their adoption of written processes for identifying, addressing, and mitigating improper foreign influence.

NSPM-33 includes many requirements for agencies related to their processes for identifying, addressing, and mitigating improper foreign influence:

· Identifying improper foreign influence. NSPM-33 states that agencies are required to implement disclosure policies to enable them to identify conflicts of interest and commitment.[13] For example, agencies must require information related to organizational affiliations, other support, and participation in foreign talent recruitment programs in award applications and throughout the award life cycle.[14] Additionally, agencies must cooperate with agency Offices of Inspector General (OIG) and law enforcement to identify disclosures that could evidence improper foreign influence.

· Addressing improper foreign influence. NSPM-33 states that agencies are required to cooperate with agency OIGs and law enforcement to investigate potential violations of disclosure requirements and respond to incidents of improper foreign influence with appropriate and effective consequences. For example, such consequences could include terminating the federal grant or preserving the grant but ensuring the individual with the disclosure violation is removed from the project. Additionally, documentation is a necessary part of an effective internal control system. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should develop and maintain documentation for organizational procedures and document in policies for each unit its responsibility for an operational process.[15] Such written processes could better position agencies to ensure staff understand how to address potential improper foreign influence.

· Mitigating improper foreign influence. Whereas addressing improper foreign influence applies to violations of disclosure requirements or other incidents of improper foreign influence, mitigating the risk of improper foreign influence involves responding to properly disclosed relationships that may pose a threat. NSPM-33 states that agencies should work with OSTP and the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) to communicate to the research enterprise their policies and actions to mitigate improper foreign influence risk. For example, an agency may require a research institution to replace researchers with significant financial interests in Chinese companies that pose a risk that cannot be mitigated.

One agency—NIH—has documented all its research security processes. The remaining four agencies have documented some of their processes, but gaps remain (see table 2). Fully documenting these processes could help safeguard against discrimination by establishing shared expectations among agencies, research institutions, and researchers themselves for how research security policies will be implemented. Such shared expectations could help ensure consistency in actions taken against research institutions or individuals.

Table 2: Extent to Which Selected Agencies Have Transparent Processes for Reviewing Improper Foreign Influence

|

|

Process for identifying improper foreign influence |

Process for addressing improper foreign influence allegations |

Process for mitigating improper foreign influence risk |

|

Department of Defense |

● |

◒ |

● |

|

Department of Energy |

● |

◒ |

● |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

● |

● |

◯ |

|

National Institutes of Health |

● |

● |

● |

|

National Science Foundation |

● |

● |

◒ |

● = Fully adopted ◒ = Partially adopted or plan in development ◯ = Not adopted

Source: GAO analysis of selected agencies’ documents and interviews. | GAO‑26‑107544

Identifying Improper Foreign Influence: Agencies Have Documented Processes

In our review of agency documents, we found that each of the selected agencies requires grant applicants to disclose information both before and after a grant is awarded. NSPM-33 requires agencies to collect information that agency staff could use to identify improper foreign influence. We found that all agencies require grant applicants to provide biographical details for key personnel conducting the research; information on other financial research support; and certification that key personnel are not involved with prohibited organizations. Additionally, NASA has a unique requirement that applicants cannot participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally with either China or any Chinese-owned company on the research project.[16]

NSPM-33 requires agencies to standardize disclosure forms and minimize associated administrative burden to the extent practicable. In pursuit of this goal, the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) Research Subcommittee developed common disclosure forms, which are maintained by NSF. As of August 2025, four of the five agencies have adopted NSTC’s common disclosure forms—DOD, DOE, NASA, and NSF. NIH plans to adopt the forms by January 2026. Stakeholders, including university officials, told us disclosure requirements have become less burdensome and more transparent because of the common disclosure forms and other federal guidance.

Each of the selected agencies also documented additional steps they take to verify the accuracy of information provided in disclosures, detect potential improper foreign influence, and determine improper foreign influence risk. For example, DOE reviews all funding opportunity notices before they are released to assess the risk level of the solicitation and ensure appropriate documentation is requested as part of the solicitation. Using this risk assessment, DOE conducts reviews of research proposals before selection and throughout the life of a project. Similarly, DOD and NSF review research proposals using publicly and commercially available information, at a minimum, to verify the accuracy of disclosures. NASA and NIH conduct reviews of research proposals and ongoing projects when improper foreign influence is suspected or reported, such as by research institutions, whistleblowers, or law enforcement agencies.

Addressing Improper Foreign Influence: DOD and DOE Have Not Fully Documented Their Processes

We found that three of the five selected agencies—NASA, NIH, and NSF—have documented their processes for addressing potential improper foreign influence. As discussed previously, NSPM-33 requires agencies to cooperate with their OIG and law enforcement in the investigation of, and to ensure appropriate and effective consequences for, disclosure violations and other activities that threaten research security and integrity, such as improper foreign influence. Each of these three agencies documents how potential improper foreign influence will be investigated, its consequences, and how the accused research institution can respond to and appeal allegations. Specifically, according to their documented processes, each of these agencies may refer key personnel that intentionally fail to disclose required information to its OIG or law enforcement agencies to investigate whether any criminal or civil laws have been violated. Additionally, each of these agencies’ documented processes list consequences of failure to disclose required information; the consequences could include award termination and suspension or debarment proceedings.[17]

NASA, NIH, and NSF have processes that specify the due process rights for research institutions and their key personnel, to include when and how they are notified, and when and how they can respond to and appeal allegations of improper foreign influence. Agency officials told us research institutions, rather than key personnel, typically respond to allegations because the institutions are the grant applicants and recipients. NIH officials indicated that key personnel could use the agency’s appeals processes without going through their research institution, but that no one has done so. Key personnel have specific due process rights, in addition to those of their institutions, under some circumstances, such as if the personnel are referred for suspension or debarment proceedings.

Stakeholders we spoke to told us that research institutions may prioritize their relationships with funding agencies over defending their key personnel, so as not to risk funding. This can make it challenging for key personnel to appeal adverse decisions that affect them because they rely on their employer to appeal on their behalf. Additionally, while key personnel can use their research institutions’ appeals processes, one stakeholder told us these processes typically lack due process, in part, because individuals are not given enough information to dispute agencies’ accusations against them.[18]

DOD and DOE have not documented their processes for addressing potential improper foreign influence. This is consistent with our prior work on this topic. In December 2020, we found that DOD and DOE did not have documented processes for enforcing their disclosure requirements.[19] We recommended that both agencies document procedures, including roles and responsibilities for addressing and enforcing failures to disclose information. Both agencies concurred with our recommendations; however, neither has fully implemented them as of August 2025. DOE has developed an interim process for addressing failures to disclose significant financial interests, and DOD has a draft department-wide policy for addressing failures to disclose either conflicts of interest or conflicts of commitment. However, neither agency has finalized their interim processes. We believe that doing so would increase transparency and better position both agencies to ensure staff understand how to address potential improper foreign influence.

Mitigating Improper Foreign Influence Risk: NASA and NSF Have Not Fully Documented Their Processes

We found that three of the five selected agencies—DOD, DOE, and NIH—have adopted written processes for mitigating improper foreign influence risk. NSPM-33 emphasizes the importance of communicating agencies’ processes for mitigating improper foreign influence risk to enhance awareness of such risks and strategies for addressing them.[20] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government call for management to develop and maintain documentation for organizational procedures, and document in policies for each unit its responsibility for an operational process. Each of these three agencies developed an improper foreign influence risk profile, which they use to determine whether risk mitigation is required, recommended, or not needed using factors such as (1) affiliation with a malign foreign talent recruitment program, (2) foreign funding, and (3) affiliation with foreign institutions or entities.

These three agencies also have documented mitigation strategies. For example, NIH’s mitigation strategies for managing foreign financial conflicts of interest that increase improper foreign influence risk include publicly disclosing the conflict of interest, modifying the research plan, or reducing or eliminating the financial interest. Similarly, DOE’s mitigation strategies include imposing special terms and conditions on the award or requiring individuals that present improper foreign influence risks to be removed from the project. DOD has a department-wide process documenting how each of its components should mitigate improper foreign influence risk. Additionally, DOD officials told us DOD components are currently developing supplemental risk mitigation processes suited to their missions and risk tolerances.[21]

DOD’s, DOE’s, and NIH’s risk mitigation processes also document due process rights for research institutions and their key personnel, including when and how agencies notify institutions of improper foreign influence risks and when and how institutions and key personnel can appeal adverse decisions. More specifically, each of these agencies’ processes include provisions explaining how and when institutions can appeal mitigation actions taken in response to improper foreign influence risks, such as an agency decision to remove key personnel from a research project.

NSF has not fully documented its written process for mitigating improper foreign influence risk. NSF’s Trusted Research Using Safeguards and Transparency (TRUST) framework, which is in its pilot stage, states that improper foreign influence risk should be mitigated but does not specify risk factors, risk levels, timing of actions to mitigate risk, or due-process rights available to research institutions and their key personnel in response to mitigation actions.[22]

NSF officials told us they plan to document these elements when the TRUST framework is fully implemented, and that the agency currently handles risk mitigation in an ad-hoc manner. For example, NSF officials told us some of the steps the agency can take to mitigate improper foreign influence risk include requiring additional certifications, additional training, travel restrictions, or removal of key personnel from projects. NSF officials told us that they plan to develop a standardized risk mitigation process using pilot results and lessons learned from other agencies and that the agency currently does not have enough information to document specific risk factors, risk levels, risk mitigation strategies, and due process rights. However, documenting an interim risk mitigation process could improve the quality of information collected from the pilot program by increasing transparency and better ensuring staff understand how to mitigate improper foreign influence risk.

NASA has not yet documented its process for mitigating improper foreign influence risk. NASA officials told us they plan to develop such a process but could not provide a timeline for doing so because the office responsible for its development was dissolved in April 2025. NASA officials told us they plan to include risk mitigation in an upcoming set of improper foreign influence policies and procedures. NASA officials told us the agency has been using existing authorities and controls to mitigate improper foreign influence risk. Specifically, NASA officials told us the agency mitigates risk by documenting disclosure requirements and prohibitions against affiliating with entities of concern in their grant policy. However, NASA’s grant policy does not document the agency’s risk assessment criteria, remediation steps, or due process rights for research institutions or their key personnel. Developing and documenting a process with these additional elements for mitigating improper foreign influence risk would increase transparency and better position NASA to ensure staff understand how to consistently mitigate improper foreign influence risk.

NIH Collects Demographic Data That Could Be Used to Assess Potential Discrimination

Demographic data on researchers involved in potential cases of improper foreign influence may provide a safeguard against discrimination by allowing stakeholders to assess how agencies’ research security processes are operating and allow agencies to modify procedures that are not meeting their intended goals. Demographic data alone cannot prove the presence or absence of discrimination, but if the data reveal significant differences in outcomes for researchers of different races, ethnicities, or national origins, this can be a flag for agency officials to investigate what factors led to those differences.

Agencies are not required to collect and analyze demographic data during improper foreign influence reviews; however, we found that one of the five selected agencies—NIH—collects data that can be used to assess potential discrimination in improper foreign influence reviews. NIH collects data that can be used to assess whether researchers of certain demographic groups are more likely to be investigated or to receive consequences for improper foreign influence as compared to researchers of other demographic groups. NIH data related to its improper foreign influence cases include limited demographic data (race and ethnicity, but not national origin). According to NIH officials, they voluntarily collect data on race and ethnicity during researchers’ participation in the NIH peer review processes, and those data do not include national origin.[23]

NIH has used these data to conduct some analyses on differences in race among researchers with allegations of improper foreign influence. For example, in NIH’s Brief Summary of NIH Foreign Interference Cases, the agency indicated that a higher proportion of individuals who self-identified as Asian faced improper foreign influence allegations as compared to any other racial group. Also, the data showed that researchers who identified as Asian constitute the majority of cases reviewed for improper foreign influence and that China was the primary country of concern. However, NIH officials indicated that they have not conducted an in-depth analysis of potential discrimination related to membership in a particular demographic group with these data.

GAO conducted an analysis on NIH’s data that highlights how collecting and assessing demographic data could help provide information about the risks of discrimination (see app. II for additional details). For example, demographic data could provide agencies visibility into whether researchers of certain demographic groups are more likely to be investigated or to receive consequences for improper foreign influence as compared to researchers of other demographic groups. Also, data can provide agencies with information on possible emerging trends in the types of improper foreign influence faced by the agencies, such as which countries are primary causes of improper foreign influence.

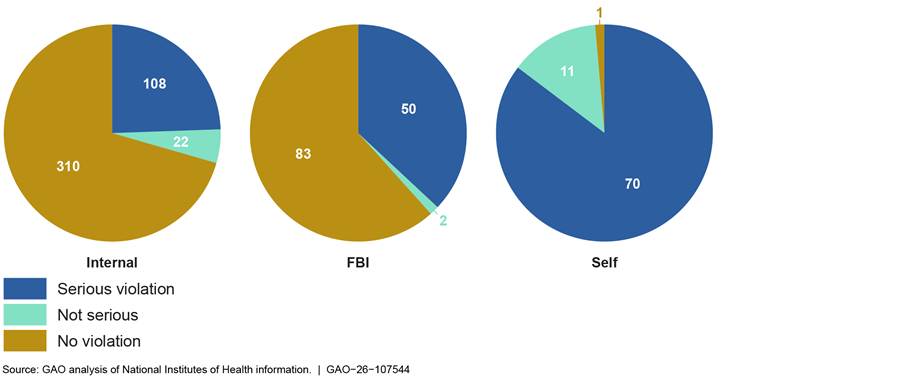

Using multivariate analysis, we assessed whether there were statistically significant differences in allegations of improper foreign influence among different races and among different countries of concern (see fig. 1). We found there were statistically significant differences among countries targeting specific racial groups, showing that cases with China as the country of concern involved Asian researchers more compared to all other countries.[24] Our analysis is comparable to NIH’s conclusion in its Brief Summary of NIH Foreign Interference Cases, which indicated that the high number of Asians represented “is not surprising giving the well-described recruiting efforts on the part of the [Chinese] government and institutions,” as stated in the NIH report.

Figure 1: Number of National Institute of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases by Self-Identified Race and Country of Concern, 2017–2024

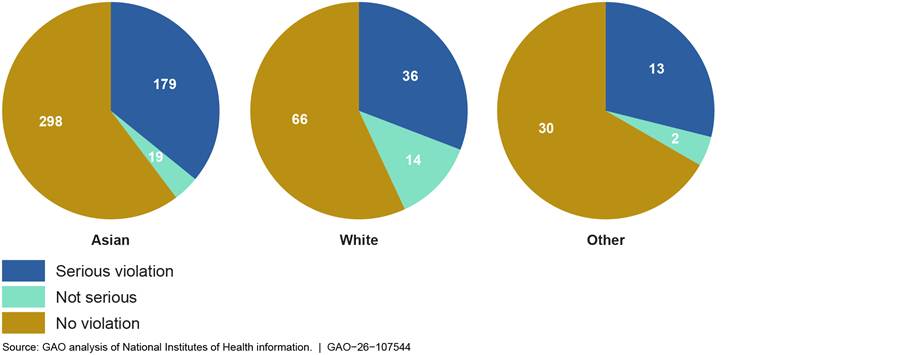

Additionally, we used multivariate analysis to examine outcomes from improper foreign influence cases and found there were no statistically significant differences in the proportions of serious violations across race (see fig. 2).[25] Our analysis shows that while Asians faced a larger portion of improper foreign influence allegations, overall outcomes across races were proportional to each other. Given the absence of a statistically significant difference in the proportion of cases for each race that resulted in a serious violation, these data do not indicate the presence of discrimination in the outcomes of improper foreign influence reviews at NIH.

Figure 2: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases Outcomes by Self-Identified Race, 2017–2024

Note: Serious violations typically result in penalties, not serious violations typically result in an administrative fix, and no violation indicates that NIH did not reach out to the grant recipient.

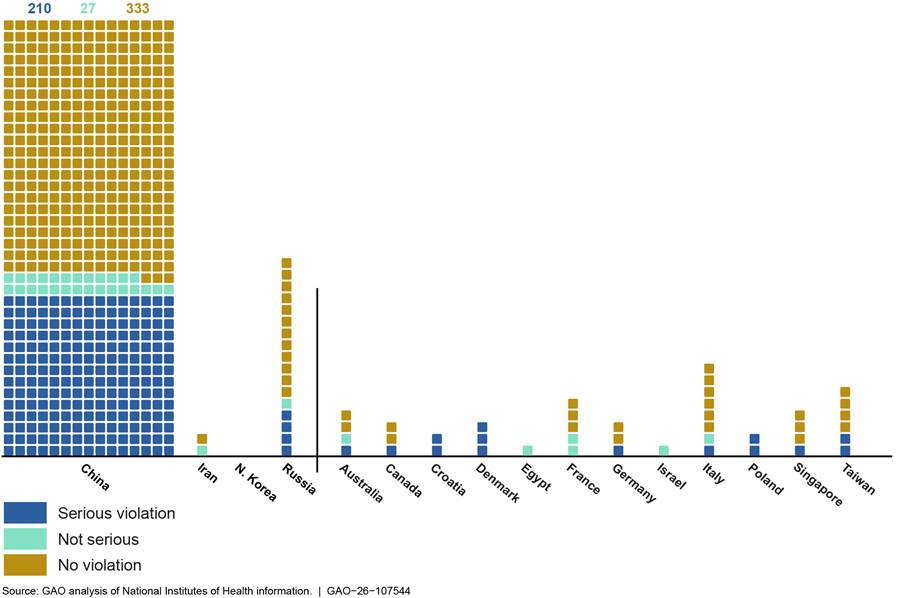

We also used multivariate analysis to examine the proportion of violations across countries (see fig. 3). While we found that the number of cases involving China was statistically significant, we found that the outcomes of those cases were not. That is, cases involving China as the country of concern were no more or less likely to result in violations of NIH’s improper foreign influence policies compared to other countries.

Figure 3: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases Outcomes by Country, 2017-2024

Note: Serious violations typically result in penalties, not serious violations typically result in an administrative fix, and no violation indicates that NIH did not reach out to the grant recipient. The data show the country involved in the alleged improper foreign influence. China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia are foreign countries of concern. 42 U.S.C. § 19,237(2).

We found the four other selected agencies did not collect or could not use the data collected to assess potential discrimination in research security processes. Agencies cited various barriers regarding the collection and usage of demographic data about researchers. Officials from DOD, DOE, NASA, and NSF indicated they do not plan to collect or use demographic data in the future for foreign influence reviews due to either resource constraints, legal concerns, or anticipated concerns that such data use may raise from the research community. In addition, a 2025 executive order may limit the types of analysis agencies may perform even if demographic data are collected.[26]

DOD and DOE cited a lack of resources as a limiting factor for collecting data. The need to collect, store, and conduct data analysis would require agencies to invest in and develop additional systems to handle the data, according to DOD officials. In addition, DOD and NSF officials said they do not have sufficient personnel needed to carry out demographic analysis. In April 2025, NASA’s Office of the Chief Scientist, the office then responsible for improper foreign influence reviews, was eliminated. Agency officials told us that the Science Mission Directorate may take over developing and implementing NASA’s improper foreign influence procedures, but reassignment of this responsibility had not been confirmed at the time of our review and is contingent on the finalization of broader agency reorganization plans, according to agency officials. NASA officials also cited legal requirements as an additional barrier to using demographic data. For example, NASA officials cited legal requirements related to agencies’ collection of information set by the Paperwork Reduction Act and the Privacy Act of 1974.[27] Also, according to NASA officials, the agency requires that a program seeking to collect demographic data must first cite a statute specifically requiring the collection of such demographic data.

DOD, DOE, and NSF officials have cited concerns from the research community about the use of demographic data as another barrier to collecting demographic data. For example, the agencies are concerned about the perception and reaction from the research community if agencies started collecting demographic data. This may include fear that provided demographic data may lead to discrimination or other negative outcomes. The concerns raised by agencies regarding demographic data collection included privacy concerns if data were published (NSF), how agencies would use data in their security reviews (DOD, NSF, and DOE), and how much information scientists would provide given that some demographic information is voluntary (NSF).

While agencies cite various barriers to collecting demographic data, there are requirements under the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 that may result in agencies gaining access to demographic data on certain researchers.[28] The act requires NSF to carry out a survey every 5 years to collect data from award recipients on the demographics of science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and computer science, faculty at different types of higher education institutions that received federal research funding. To the extent practicable, the survey will include data on faculty race, ethnicity, sex, and citizenship status, but not national origin. Once the survey is complete, agencies may have access to additional demographic data to assess potential discrimination in their research security efforts.[29]

Most Agencies Have Implemented Additional Safeguards to Promote Nondiscrimination

Most agencies have implemented the three remaining safeguards, which are multiple levels of review, training of internal staff on nondiscriminatory practices, and agency leadership commitment to nondiscrimination.

Multiple levels of review. Multiple levels of review within an agency’s research security processes can limit the risk of discrimination occurring at any one level. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that managers should consider separation of duties because dividing activities related to authority, custody, and accounting can help address the risk of management override, which circumvents existing control activities.[30] Having multiple stakeholders in a research security review helps ensure no single individual controls all key decisions.

All five agencies involve multiple stakeholders in the investigation and adjudication of improper foreign influence allegations, and this can potentially deter discrimination in agency processes. Specifically:

· DOD policy states that if an initial risk-based security review identifies any risk factor as potentially requiring mitigation, the research proposal will be referred for further review by grant management staff in the relevant DOD component. In addition, DOD requires its components to provide information on any risk mitigations taken and allows research institutions to appeal component decisions to the DOD Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering.

· At DOE, the Research, Technology, and Economic Security Office is responsible for carrying out the due diligence process to identify potential risks related to improper foreign influence, in close coordination with the Office of Intelligence. As part of the due diligence process, if a risk is identified the office develops risk mitigation strategies that are recommended to the cognizant program office. The office also works closely with other DOE offices to develop draft policies and guidance to implement statutory research security requirements and other research security related policies. If the Research, Technology, and Economic Security officials recommend removing an individual from a research proposal, DOE has a formal reconsideration process that allows research institutions to appeal the decision.

· NASA uses existing research misconduct investigation and adjudication procedures to address improper foreign influence allegations.[31] Upon receiving a referral, NASA coordinates internally among its Office of General Counsel, the Office of Procurement’s Grants Policy and Compliance team, the NASA Shared Services Center Grant Officer, the Office of Protective Services including Counterintelligence, and relevant Mission Directorates to assess the allegations. NASA will not take any action to terminate or suspend a recipient’s award until the recipient has exhausted its appeal and reconsideration rights, including judicial review.

· NIH’s due diligence reviews of improper foreign influence allegations are the responsibility of the Office of Extramural Research. If Office of Extramural Research officials determine that an adverse administrative action such as grant termination is necessary, the decision and information provided by the research institution will be reviewed by an NIH Office of Extramural Research group consisting of the Deputy Director for Extramural Research, the Director of the Office of Policy for Extramural Research Administration, the Chief Extramural Research Integrity Official, a representative from the Office of General Counsel, representatives from the Office of Management Assessment, as well as staff responsible for allegation review, management, and compliance. In addition, for some actions such as unilateral grant termination, the research institution can appeal it to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Departmental Appeals Board.

· In NSF’s TRUST pilot, Office of the Chief of Research Security Strategy and Policy staff analyze proposals and other data to flag potential concerns. If necessary, they will ask the research institution for more information and consider whether risk mitigation may be necessary. Then a Research Security Review Team consisting of five to six members from across NSF determines whether a mitigation plan is necessary. According to NSF officials, NSF has not yet developed an appeals process because this is a pilot, but they expect to use NSF’s existing pre-award appeals, post-award dispute resolution, and reconsiderations processes. These appeals processes, laid out in the NSF Proposal & Award Policies & Procedures Guide, allow proposers and awardees to dispute NSF grant decisions.[32]

Training of agency staff. Training in legal rights, responsibilities, and awareness can help deter discrimination in agency processes or grant management. Furthermore, training could also help grant management and research security staff be more aware of the potential for discrimination in their tasks.

One agency requires research security staff to take training that specifically addresses the risks of bias and discrimination, and two agencies are developing such training.

· NSF requires all agency staff and contractors to take training annually that covers NSF’s disclosure policies and the agency’s requirement that key researchers on a grant certify that they are not in a malign foreign talent recruitment program. Grant administrators and program officers must take an additional training on NSF’s proposal and award policies that focuses on building a positive culture of research security and promoting responsible international collaborations, including the risks of discrimination.

· While DOE does not have formal training devoted to the topic of avoiding discrimination, the Research, Technology, and Economic Security Office instructs staff to conduct their reviews and develop policies in a manner that does not target, stigmatize, or discriminate against individuals on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin. The instructions—which include a slide stating that policies must not target, stigmatize, or discriminate against individuals based on race, ethnicity or national origin—emphasize the importance of managing risks to research while maintaining an open, collaborative, world-leading scientific research enterprise. Further, according to DOE officials, the office is developing a formal training program that will include training on conducting equitable evaluations of issues of foreign influence.

· DOD is developing formal research security training that stresses nondiscrimination. As of May 2025, DOD was providing informal training to department staff on how to perform risk reviews, including fact-based due diligence reviews, to avoid discrimination.

· NASA and NIH do not provide training that addresses the potential for discrimination in research security processes.

Agency leadership commitment to nondiscrimination. When this safeguard is in place, the leaders of an agency regularly demonstrate that nondiscrimination is an important agency value. When an agency’s top officials show that nondiscrimination is valued through directives, attitudes, and behavior, they may send a message to staff that discrimination will not be tolerated and could result in penalties. Leadership statements available in multiple platforms such as agency websites, publications, briefings, and press releases communicate the agency’s values to potential grant recipients and the public at large. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should demonstrate a commitment to integrity and ethical values.[33]

Agency leadership in three of the five agencies have made public statements committing to nondiscrimination within their improper foreign influence processes.

· In a November 2024 memo describing DOE’s framework to minimize, mitigate, and manage improper foreign influence risk, DOE’s then–Deputy Secretary said the agency’s reviews would not discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin, in accordance with existing laws, and that DOE was committed to addressing research security concerns without alienating or unfairly targeting international colleagues.[34]

· In an August 2024 public statement affirming NIH’s support of Asian American, Asian immigrant, and Asian research colleagues, NIH’s then–Director said NIH valued Asian researchers and wished to preserve and build relationships with such researchers in the community and that NIH would not discriminate with respect to national origin or identity in its foreign interference processes.[35]

· In the February 2023 Guidelines for Research Security Analytics, the NSF Chief of Research Security Strategy and Policy and current Acting NSF Chief of Staff lauded the value of international collaboration and committed to meeting requirements in NSPM-33 to carry out NSF’s research security processes in an open, transparent, and honest manner.[36]

DOD and NASA have not issued explicit statements on nondiscrimination in their research security processes but have expressed support for international research collaboration in policy.

· In a June 2023 memo, DOD’s then-Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering said that DOD components should develop security reviews of fundamental research project proposals “in a manner that does not discourage international research collaboration.”[37]

· In May 2025, NASA officials told us their leadership regularly affirms the agency’s overall nondiscrimination values, but they have not published a statement on nondiscrimination within the agency’s research security policies because nondiscrimination is part of NASA’s scientific integrity framework and reinforced through NSPM-33 guidance. NASA’s Partnerships website also stated that they are committed to partnering with a wide variety of domestic and international partners to successfully accomplish NASA’s diverse missions.

Agencies Have Not Assessed the Effectiveness of Their Safeguards

Agencies and stakeholders have limited information on the effectiveness of agencies’ efforts to safeguard against discrimination. While each agency has implemented some safeguards for their improper foreign influence processes, agencies generally have not assessed their processes to determine whether the safeguards they have in place provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur. DOD, DOE, NASA, NIH, and NSF have either developed or are developing research security processes to address threats of improper foreign influence and are employing varying safeguards to mitigate or detect potential discrimination during improper foreign influence reviews. However, representatives of civil society groups, universities, and others told us they remain concerned that agencies’ research security processes may discriminate against researchers of Asian descent, particularly people with Chinese heritage.

Under the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, each federal research agency must ensure that its research security policies and activities are carried out in a manner that does not target, stigmatize, or discriminate against individuals on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin, consistent with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[38] Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance.[39] Additionally, NSPM-33 directs agencies to develop standard research security policies consistent with privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties.[40] The Office of Management and Budget Uniform Guidance, as adopted into regulation by each federal agency that awards federal financial assistance, provides that such agencies must manage and administer grants and cooperative agreements in a way that ensures associated programs are implemented in full accordance with the U.S. Constitution, applicable statutes, and regulations, including provisions prohibiting discrimination.[41] Similarly, regulations for federal contracts require that government business be conducted with complete impartiality and with preferential treatment for none, except as authorized by statute or regulation.[42]

However, agencies are not aware of whether their improper foreign influence processes are discriminatory because the agencies have generally not analyzed the processes to determine whether their safeguards identify or prevent discrimination.[43] Such analysis could assess agencies’ research security processes to determine whether their current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and assess whether additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. By assessing the safeguards agencies have implemented, agencies could better ensure that their research security processes do not target, stigmatize, or discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin.

Conclusions

Federal agencies must ensure that research conducted on their behalf is free of improper foreign influence. At the same time, agencies are responsible for carrying out research security programs in a manner that does not discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin. DOD, DOE, NASA, NIH, and NSF have applied safeguards to various degrees in their improper foreign influence reviews to help prevent discrimination.

However, NASA and NSF have not fully documented their processes for risk mitigation of improper foreign influence. By clearly documenting risk mitigation processes, agencies can create shared expectations with research institutions and researchers about how these processes are implemented. Additionally, agencies have not assessed their research security processes to determine whether the safeguards they have in place provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur. By assessing their current safeguards, agencies can provide greater assurance that discrimination will not occur and may identify additional safeguards appropriate to the agency.

Recommendations for Executive Actions

We are making a total of seven recommendations, including two each to NASA and NSF and one each to DOD, DOE, and NIH. Specifically:

The Director of the NSF should ensure that the Office of the Chief of Research Security Strategy and Policy, or the appropriate office within NSF, document an interim risk mitigation process for its TRUST pilot while continuing to develop a final process. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of NASA should ensure that the appropriate office document how its interim process addresses risk assessment criteria, remediation steps, and due process rights for research institutions or individuals as it continues to develop its final research security process. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, or the appropriate office within DOD, assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Research, Technology, and Economic Security Office, or the appropriate office within DOE, assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. (Recommendation 4)

The Administrator of NASA should ensure that the appropriate office assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. (Recommendation 5)

The Director of NIH should ensure that the Office of Extramural Research, or the appropriate office within NIH, assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. (Recommendation 6)

The Director of NSF should ensure that the Office of the Chief of Research Security Strategy and Policy, or the appropriate office within NSF, assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD, DOE, HHS, NASA, and NSF for review and comment. DOE, HHS, NASA, and NSF provided written comments that are reprinted in appendices III, IV, V, and VI, respectively, and summarized below. In addition, DOE, HHS, and NSF provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. DOD did not provide comments on this report.

HHS and NASA concurred with our recommendations. HHS noted that the NIH Office of Management Assessment plans to initiate a review of the agency’s research security processes and NASA noted that its Science Mission Directorate will document and assess the agency’s research security processes. In its comments, NSF noted that it will consider and discuss how to incorporate our recommendations into the second phase of its research security pilot.

In its comments, DOE disagreed with our recommendation to assess the agency’s research security processes to determine whether current safeguards provide reasonable assurance that discrimination will not occur and whether any additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial. DOE noted that the department developed its research security process to ensure that discrimination will not occur and that its current framework was reviewed by DOE’s External Civil Rights Division. DOE also noted that when it amends its processes it will reassess the effectiveness of its safeguards. However, as we noted in the report, agencies, including DOE, are not aware of whether their processes are discriminatory because they have generally not analyzed the processes to determine whether their safeguards identify or prevent discrimination. We continue to believe that by assessing the department’s safeguards, DOE could better ensure that its research security processes do not target, stigmatize, or discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin. Moreover, assessing implementation of its research security framework would provide the department and stakeholders with greater assurance that the research security process is operating as intended and whether additional safeguards would be practical and beneficial.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until one day after the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Energy, the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and the Director of the National Science Foundation. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at BenedictH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Hilary M. Benedict

Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

This report assesses the extent to which selected agencies have implemented safeguards to prevent discrimination in their processes for identifying, addressing, and mitigating improper foreign influence. This appendix provides additional information on how GAO identified these safeguards and reviewed agencies’ implementation of them.

For the purposes of our report, the term “improper foreign influence” refers to the misappropriation of R&D funding and findings to the detriment of national and economic security, related violations of research integrity, and foreign government interference. The term “improper foreign influence risk” refers to the increased likelihood that improper foreign influence will happen on a research project.

For our review, we selected the five agencies that provided the most extramural federal funding for scientific research in fiscal year 2023—the most recent data available at the time of our review: the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Energy (DOE), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the National Science Foundation (NSF).[44]

To identify the five safeguards that could help agencies ensure their processes do not target, stigmatize, or discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin, we reviewed agency processes, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, National Security Presidential Memorandum 33, and other sources.[45] To further enrich our understanding of this topic, we interviewed knowledgeable agency officials responsible for implementing improper foreign influence policies. We also interviewed representatives from a non-generalizable selection of seven universities and seven professional and civil society organizations. We interviewed these representatives about their views on improper foreign influence and discrimination, the efforts of federal agencies and research institutions to ensure discrimination does not occur during improper foreign influence reviews, and the benefits and risks of improper foreign influence reviews. We selected these organizations based on their involvement in research-security-related activities, such as conferences or working groups.

Using these processes, laws, policies, and interviews, we identified five safeguards: (1) documentation and transparency of research security policies and procedures; (2) collection and analysis of data to assess agency procedures; (3) multiple levels of review; (4) training agency staff; and (5) leadership commitment. This list should not be considered exhaustive; other possible safeguards may exist that were not identified by our work.

To assess agency implementation of the five safeguards, we reviewed agency improper foreign influence policies and processes. For each safeguard, we discussed these policies and processes with agency officials, asked clarifying questions, and reviewed their responses. We also took the following steps to assess each safeguard:

· Documentation and transparency of research security policies and procedures. To assess whether agencies had documented and transparent improper foreign influence policies and procedures, we compared agency policies and procedures with internal controls, the 2021 presidential memorandum, and the 2022 Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) implementation guidance on improper foreign influence. Specifically, we identified three types of improper foreign influence processes—identifying improper foreign influence, addressing violations, and mitigating risk—and assessed whether agencies had fully adopted them.

· Collection and analysis of data to assess agency procedures. To determine whether agencies were collecting and analyzing data to assess their processes, we requested demographic data for researchers involved in improper foreign influence reviews. We could not analyze demographic data for four of five agencies—DOD, DOE, NASA, and NSF—because they either do not collect it or were unable to link such data to their improper foreign influence reviews. We analyzed NIH data by comparing it to information previously published by the agency and performed basic tests to identify the usability of the data in differential analysis (see app. II). We determined the data to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

· Multiple levels of review. To assess whether agencies have multiple levels of review, we looked for evidence that agency improper foreign influence adjudication and appeals processes were divided among multiple offices or individuals.

· Training agency staff. To assess whether agencies were providing training to their staff on how to apply improper foreign influence processes in a nondiscriminatory manner, we reviewed agency improper foreign influence training information to determine whether it addressed discrimination.

· Leadership commitment. To assess whether agency leadership had made public commitments to implement improper foreign influence policies and processes in a non-discriminatory manner, we reviewed agency documentation and public-facing websites to determine whether a public commitment had been made and was accessible on an agency website as of August 2025.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Demographic data on researchers involved in potential cases of improper foreign influence can provide a safeguard against discrimination by allowing agencies to assess how their research security processes are operating and allow agencies to respond accordingly.

As of September 2025, National Institutes of Health (NIH) was the only one of the five selected agencies that was collecting data that could be used to assess potential discrimination. Therefore, we analyzed NIH’s data to determine whether collecting and analyzing demographic data could help provide information about the potential existence of discrimination in improper foreign influence reviews. NIH provided us with improper foreign influence data from 2017 to 2024. The data contained 657 allegations of improper foreign influence.[46] For this analysis, we focused on the following data points:

· Demographic data. Includes self-identified race, self-identified ethnicity, and citizenship. For data on race, GAO created an “other” category to incorporate data points regarding race that had a smaller number of data points compared to Asian and White. The other category combines three options for race: “more than 1 race,” “withheld,” and “unknown.”

· Country of concern. The country of concern is the country identified as conducting the alleged improper foreign influence.

· Source of allegation. The source that prompted initial review: Federal Bureau of Investigation, internal from NIH, or self-reported by the research institution.

· Contact versus not contacted. Whether or not the case met the requirements for review and a research institution was contacted by NIH.

· Type of violations (serious, not serious, or no violation). A serious violation is a violation that could not be mitigated and resulted in a penalty. Some examples of serious violations are undisclosed grant support, undisclosed talents award (i.e., compensation received from a malign foreign talent recruitment program), or undisclosed conflict of interest. A not serious violation could be mitigated through an administrative fix. No violation indicates that NIH did not reach out to the grant recipient (no undisclosed foreign affiliation and no serious violation).

· Outcome of violations. Research institutions and NIH have options they can use once a violation has occurred. For example, research institutions have the option of terminating the researcher implicated or barring them from NIH projects, known as internal debarment.[47] NIH has enforcement actions it can take, such as removing a researcher from conducting peer reviews, disallowing costs, withholding of further awards, or wholly or partly suspending the grant. In some cases, NIH can terminate the grant in whole or in part.

Our analysis of the NIH data identified some statistically significant differences and other differences that are not statistically significant. This information is summarized in the report and presented in the figures below. While differences alone are not evidence of discrimination, they could indicate to an agency that further investigation may be appropriate to determine whether discrimination played a role in such a difference.

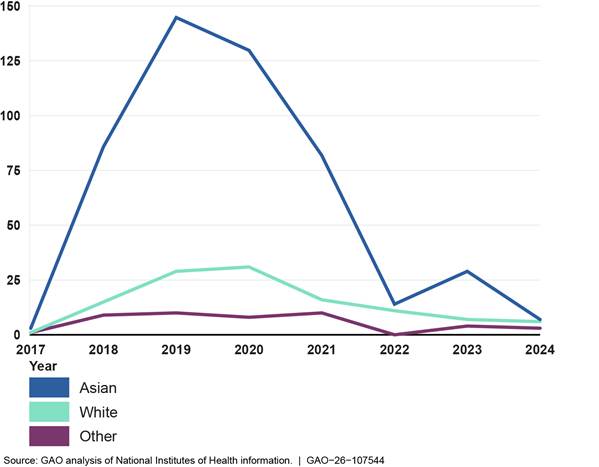

Figure 4 shows that Asians composed the majority of improper foreign influence cases at NIH, using self-identified race. We found that the number of cases peaked in 2019 and has decreased since then, with Asians being the most represented group. Also, in our analysis of the NIH data, we found statistically significant differences in the number of investigations by race (p < .05), after adjusting for citizenship and allegation year.[48] Analysis of these data could show potential differences between races over time and signal the need for an agency to conduct a further evaluation.

Figure 4: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases by Self-Identified Race and Allegation Year, 2017-2024

Note: The differences in self-identified race proportions across allegation years are statistically significant (p < .05). The association with being investigated by the NIH and race (p < .05) is statistically significant.

Figure 5 shows that NIH generally found violations in self-referred allegations, while other sources led to more mixed outcomes. We found the differences in outcomes were statistically significant across the three sources (p < .05). Regarding the source of review, we found that most cases of improper foreign influence were identified by NIH, but cases were also referred to NIH by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and by the research institutions at issue (described in fig. 5 as “self” for the source of review). An analysis of such data could allow an agency to determine whether there was a difference in outcomes by the source of the improper foreign influence allegation.

Figure 5: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases Violations by Source of Review, 2017-2024

Note: Serious violations typically result in termination, not serious violations typically result in an administrative fix, and no violation indicates that NIH did not reach out to the grant recipient. “Self” means the relevant research institution referred the case to the NIH. The association with being investigated by the NIH and source of review (p < .05) is statistically significant.

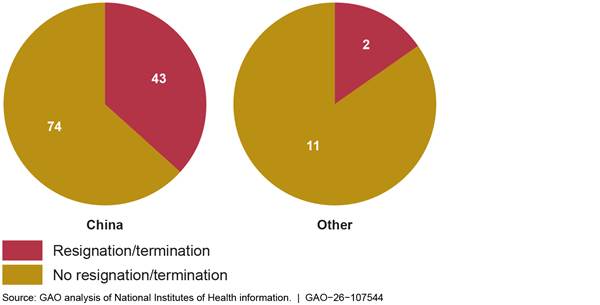

Our analysis found that of the cases that resulted in resignation or termination, China was more often the country of concern than other countries were (see fig. 6). However, although the number of cases with China as the country of concern was larger than all other countries, the difference in the result of the cases is not significantly different (p > .05).[49] Similarly, we did not find a significant difference in race or citizenship of the cases that led to resignation or termination. These data can be used to monitor if more severe consequences arise from cases involving specific countries of concern, races, or other factors.

Figure 6: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases Resulting in Resignation or Termination, by Country of Concern, 2017-2024

Note: Differences in the resignations and terminations by country of concern was not statistically significant.

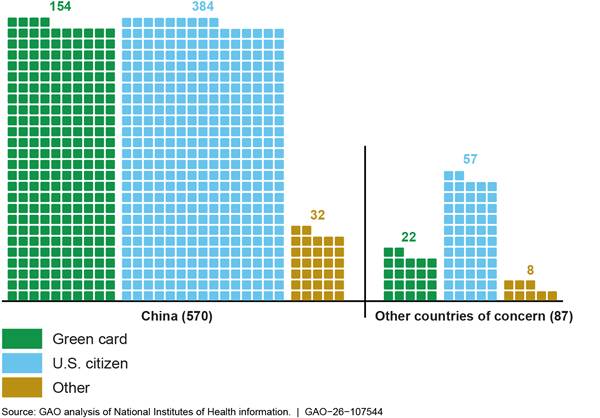

Figure 7 shows that both U.S. citizens and green card holders have been targeted by foreign countries for improper foreign influence. Additionally, we found that significantly more green card holders involved in potential cases of improper foreign influence were from China, compared to other countries of concern (p < .05). These data could be used by an agency to determine whether there may be discrimination against citizens or noncitizens in improper foreign influence cases.

Figure 7: Number of National Institutes of Health Improper Foreign Influence Cases by Country of Concern and by Citizenship or Green Card Status, 2017-2024

Note: The proportion for Green Card holders with China as the country of concern is significantly different from the other citizenship statuses (p < .05). Citizenship status describes (1) non-U.S. citizens with permanent U.S. residency (Green Card) (2) U.S. citizens, and (3) non-U.S. citizens without permanent U.S. residency and unknown status (other).

GAO Contact

Hilary M. Benedict at BenedictH@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Tind Shepper Ryen, Assistant Director; Eliot S. Fletcher, Analyst-in-Charge; Adam Brooks; Jenny Chanley; George Depaoli; Darren Grant; Georgeann Higgins; Mark Kuykendall; Won Lee; and Joe Rando.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See, for example, Sarah M. Rovito, Divyansh Kaushik, and Surya D. Aggarwal, “The impact of international scientists, engineers, and students on U.S. research outputs and global competitiveness,” MIT Science Policy Review, vol. 2 (Aug. 30, 2021); Tina Huang, Zachary Arnold, and Remco Zwetsloot, “Most of America’s “Most Promising” AI Startups Have Immigrant Founders,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology, Georgetown University (Oct. 2020); and James P. Walsh, "The impact of foreign-born scientists and engineers on American nanoscience research." Science and Public Policy 42, no. 1 (2015): 107-120.

[2]NIH, Brief Summary of NIH Foreign Interference Cases (Nov. 30, 2024). Accessed at https://grants.nih.gov/SITES/DEFAULT/FILES/FOREIGN-INTERFERENCE-11-30-24-REPORT.PDF. We use the term “improper foreign influence,” while the NIH Brief Summary uses the term “foreign interference.”

[3]National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 (NSPM-33) directs agencies to take actions to strengthen protections of U.S. government supported R&D against foreign government interference and exploitation. Research security requirements in NSPM-33 apply across the U.S. R&D enterprise, including to support provided to an individual or entity by a federal research agency to carry out R&D activities in the form of a grant, cooperative agreement, contract, or other such award. The White House, Presidential Memorandum on United States Government-Supported Research and Development National Security Policy, National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 14, 2021). In this report, we generally focused on agencies’ grants process except where noted.

[4]GAO, Federal Research Grants: Opportunities Remain for Agencies to Streamline Administrative Requirements, GAO-16-573 (Washington, D.C.: June 22, 2016).

[5]Ekaterina Galkina Cleary, Jennifer M. Beierlein, Navleen Surjit Khanuja, Laura M. McNamee, and Fred D. Ledley. “Contribution of NIH funding to new drug approvals 2010–2016,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 115, no. 10 (2018): 2329-2334.

[6]Christine Yifeng Chen, Sara S. Kahanamoku, Aradhna Tripati, Rosanna A. Alegado, Vernon R. Morris, Karen Andrade, and Justin Hosbey. “Systemic racial disparities in funding rates at the National Science Foundation,” Elife, vol. 11 (2022).

[7]The White House, Presidential Memorandum on United States Government-Supported Research and Development National Security Policy, National Security Presidential Memorandum – 33 (NSPM-33) (Jan. 14, 2021).