OFFSHORE PATROL CUTTER

Coast Guard Should Gain Key Knowledge Before Buying More Ships

Report to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Shelby S. Oakley at oakleys@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Coast Guard urgently needs Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPC) to replace aging cutters that conduct law enforcement and search and rescue operations. The Coast Guard plans to acquire 25 OPCs in stages: stage 1 initially included OPCs 1-4, stage 2 includes OPCs 5-15, and stage 3 will include OPCs 16-25. Construction for stages 1 and 2 is underway by two different shipbuilders. But each shipbuilder’s design remains incomplete, and both have yet to deliver any ships.

The stage 1 shipbuilder made limited progress since GAO last reported on OPC. In 2023, GAO found that construction of OPCs 1-4 began without a stable design, contrary to shipbuilding leading practices. This led to rework, which delayed ship deliveries. The Coast Guard took steps in 2024 to prioritize delivery of OPC 1, such as adding payments at certain milestones, but these steps were largely unsuccessful. As of July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated construction of OPCs 3 and 4 as part of an ongoing review of the current stage 1 contract, and delivery of OPC 1 was expected more than 5 years late.

Offshore Patrol Cutters 1 (left) and 2 (right) Construction Status in December 2024

The stage 2 shipbuilder and Coast Guard incorporated some leading practices while developing the stage 2 design, such as conducting collaborative design reviews that supported timely decisions. But construction of OPC 5 began in August 2024 without a stable design. Starting construction of more stage 2 OPCs before stabilizing the design, as the Coast Guard plans to do, increases the risk that stage 2 will also encounter costly rework and schedule delays.

The OPC program is at risk of not meeting its cost goals, in part, because the program used outdated cost information to establish them. The program is updating this information to account for recent stage 1 cost increases. GAO also found that the program reported an aggregated cost goal for all 25 OPCs instead of by stage. Reporting cost goals by stage would enable decision-makers to hold the program and OPC shipbuilders accountable for their performance.

The program plans to acquire stage 3 ships after testing whether the existing designs meet OPC’s performace goals, which is consistent with Department of Homeland Security (DHS) policy. However, the program is unlikely to have the test results before starting stage 3 procurement activities, such as developing the request for proposals. Incorporating the knowledge gained from testing—as well as other shipbuilding leading practices—into the procurement process for stage 3 could help the Coast Guard make better investment decisions. It could also improve the timeliness of future OPC deliveries.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Coast Guard—a component of DHS—plans to spend over $17 billion to acquire a fleet of 25 OPCs. Since 2020, GAO has found that the Coast Guard is using a high-risk approach to acquire OPCs that involves significant overlap in design and construction.

GAO was asked to review the status of the OPC acquisition program. This report examines the extent to which (1) progress has been made on OPC design and construction; and (2) the OPC program is meeting its cost and performance goals.

GAO analyzed OPC documents and data; compared the status of OPC stage 1 design and construction to what GAO reported in June 2023 (GAO-23-105805); and compared stage 2 design and construction to leading practices for commercial shipbuilding. GAO also conducted site visits to both OPC shipbuilders to observe stage 1 and stage 2 construction progress; and interviewed Coast Guard officials and shipbuilder representatives.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations to the Coast Guard and DHS, including that the program stabilizes design before starting construction of additional stage 2 OPCs; reports cost goals for each OPC stage; and documents a plan for acquiring stage 3 ships that identifies how it will use test results to inform procurement activities and further incorporate shipbuilding leading practices. DHS concurred with two of the four recommendations, and did not concur with the other two. GAO maintains that all four recommendations are warranted.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ADE |

acquisition decision event |

|

|

DCMA |

Defense Contract Management Agency |

|

|

DFARS |

Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement |

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

|

ESG |

Eastern Shipbuilding Group, Inc. |

|

|

EVM |

earned value management |

|

|

HVAC |

heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

|

|

KPP |

key performance parameter |

|

|

MEC |

Medium Endurance Cutter |

|

|

NAVSEA |

Naval Sea Systems Command |

|

|

OPC |

Offshore Patrol Cutter |

|

|

SUPSHIP |

Supervisor of Shipbuilding, Conversion and Repair |

|

|

T-ATS |

towing, salvage, and rescue ships |

|

|

TRL |

technology readiness level |

|

|

VFI |

vendor-furnished information |

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 25, 2025

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Coast Guard—a component within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—plans to spend more than $17 billion to acquire a fleet of 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPC). OPC is one of the Coast Guard’s largest acquisition programs and highest investment priorities. The OPCs will replace the aging fleet of Medium Endurance Cutters (MEC), which have exceeded their 30-year design service lives and are increasingly difficult and costly to maintain. The OPCs will enable the Coast Guard to continue conducting patrols for homeland security, law enforcement, and search and rescue operations. Growing demand for the Coast Guard to support migrant and drug interdiction increases the need for more capable cutters. Accordingly, in July 2025, the Coast Guard received an additional $4.3 billion for procurement of OPCs.[1]

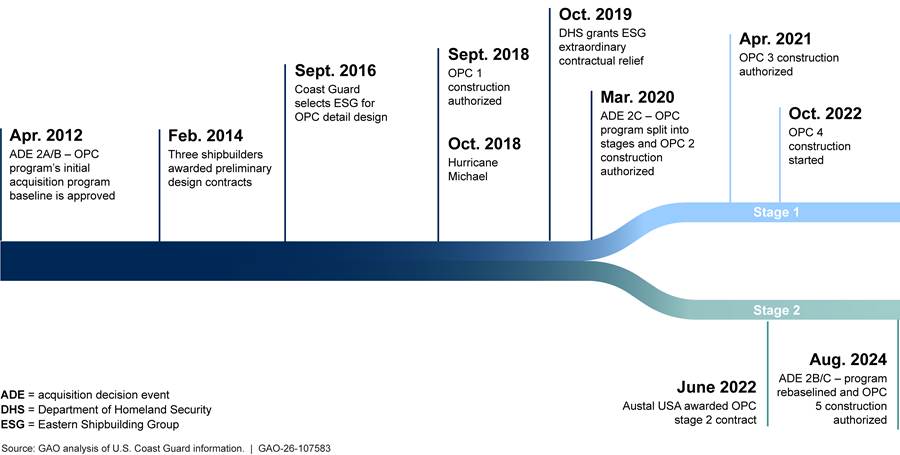

In February 2014, the Coast Guard awarded contracts to three vendors for preliminary and contract design work for the OPC. Among these vendors, the Coast Guard selected Eastern Shipbuilding Group, Inc. (ESG) as OPC’s shipbuilder. To do so, the Coast Guard exercised ESG’s contract option for detail design in September 2016 and an option for construction of the first OPC in September 2018. Following significant damage and disruption to the shipbuilder caused by Hurricane Michael in 2018, DHS granted contractual relief to ESG for the design and construction of up to four OPCs, an effort the Coast Guard refers to as stage 1.[2] DHS also directed the Coast Guard to recompete the requirement for the remaining 21 cutters.[3] In June 2022, the Coast Guard awarded a contract to Austal USA, LLC—hereafter referred to as Austal—for OPC detail design, with options for the construction of up to 11 of the remaining 21 OPCs, an effort known as stage 2. This contract has a potential value of $3.2 billion if all options are exercised. The Coast Guard plans to acquire the remaining OPCs to reach a total of 25 in a future effort referred to as stage 3.

Since October 2020, we have reported that the Coast Guard has employed a high-risk approach of acquiring OPCs that involves significant overlap in technology development, design, and construction activities.[4] For example, we reported that the Coast Guard began construction of all four stage 1 ships without achieving a stable design. This concurrent approach is contrary to shipbuilding leading practices and increases the risk of negative outcomes, such as cost growth and schedule delays, which the Coast Guard has already realized. For example, in June 2023, we found that the program’s total cost to acquire OPCs increased by 41 percent between 2012 and 2022 and that delivery of the first ship slipped by over 1.5 years.[5]

You asked us to review the status of the OPC acquisition program. This report examines the extent to which (1) progress has been made on OPC design and construction; and (2) the OPC program is meeting its schedule, cost, and performance goals.

To assess the progress made on OPC design and construction, we reviewed documentation related to OPC design and construction efforts, such as contracts, design completion rates, and program briefings. We compared the status of OPC stage 1 design and construction with what we reported in June 2023.[6] We compared the status of OPC stage 2 design and construction with leading practices that we previously identified in commercial shipbuilding.[7] To assess whether the program is meeting its schedule, cost, and performance goals, we reviewed relevant documentation, such as integrated master schedules, life-cycle cost estimates, earned value management (EVM) data, the test and evaluation master plan, and risk register. We compared the information in these documents with the latest acquisition program baseline approved by DHS leadership in August 2024.

Additionally, we conducted a site visit to the OPC stage 1 and stage 2 shipyards to tour the facilities, observe OPC construction progress, and interview representatives from ESG and Austal. We interviewed officials from the OPC program office; OPC project resident office that provides on-site oversight at ESG and Austal; the Coast Guard’s OPC ship design team and sponsor; the American Bureau of Shipping (a classification society); the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA); the Navy’s Supervisor of Shipbuilding, Conversion and Repair (SUPSHIP); and DHS’s Test and Evaluation Division. Appendix I presents a detailed description of the objectives, scope, and methodology for our review. Appendix II presents the status of prior recommendations we made to DHS or the Coast Guard regarding the OPC program.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to November 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

OPC Mission, Planned Capabilities Compared with MECs, and Equipment

In January 2008, the Coast Guard established the OPC program’s mission needs. Designed for long-distance transit, extended on-scene presence, and operations with deployable aircraft and small boats, the Coast Guard intends for OPCs to provide the majority of offshore presence for its cutter fleet.[8] Figure 1 is a photograph of the first OPC under construction at the shipbuilder’s yard.

The OPC will perform many of the same missions as the MECs, including search and rescue; interdicting drugs and migrants; and securing ports, waterways, and coastal areas. The Coast Guard’s fleet of MECs includes 12 210-foot and 13 270-foot MECs, all of which have exceeded their design service life of 30 years.[9] Despite multiple recapitalization efforts, both classes of MECs face mission readiness challenges due to age and parts obsolescence. For example, in June 2025, we found that all MECs had declining operational availability during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 due to maintenance issues, such as delays in receiving repair materials.[10]

To address a potential operational capability gap caused by the risk of MECs failing before they are replaced by the OPCs, the Coast Guard started an acquisition program in 2018 to extend the service life of six 270-foot MECs by up to 10 years. This program is expected to cost more than $250 million. The Coast Guard built flexibility into the contracts for this program to extend the service life for additional MECs, if necessary. However, in June 2023, we found that—even with this program—the Coast Guard faced an operational gap because of delays in the OPC delivery schedule.[11]

Once delivered, the Coast Guard expects OPCs to be more capable than the MECs. The Coast Guard established key performance parameters (KPP) that the OPC must meet to achieve full operational capability. Some examples of KPPs are the ability to handle at least 45 days at sea while housing a crew of 104, and the capability of launching small boats and helicopters for operations such as drug and migrant interdiction, search and rescue, and law enforcement activities. Table 1 details examples of key capabilities for the OPC compared with the MECs.

Table 1: Examples of Key Capabilities of the Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) and Medium Endurance Cutters (MEC)

|

Capabilities |

OPC |

210-foot MEC |

270-foot MEC |

|

Operating range |

8,500 NM |

6,100 NM |

8,500 NM |

|

Crew size |

104 |

77 |

100 |

|

Sea keeping for small boat, helicopter operations, and rescue assistancea |

Sea state 5 |

Sea state 4 |

Sea state 4 |

|

Patrol endurance |

45 days underway |

21 days underway |

21 days underway |

NM = nautical miles

Source: GAO presentation of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO‑26‑107583

aSea keeping is the ability of the vessel to withstand varying conditions at sea. Sea state refers to the height, period, and character of waves on the surface of a large body of water. The Coast Guard ranks sea state on a scale from 0 (calm) to 8 (very high). Sea state 4 is moderate at 4-to-8-foot waves and sea state 5 is rough at 8-to-13-foot waves.

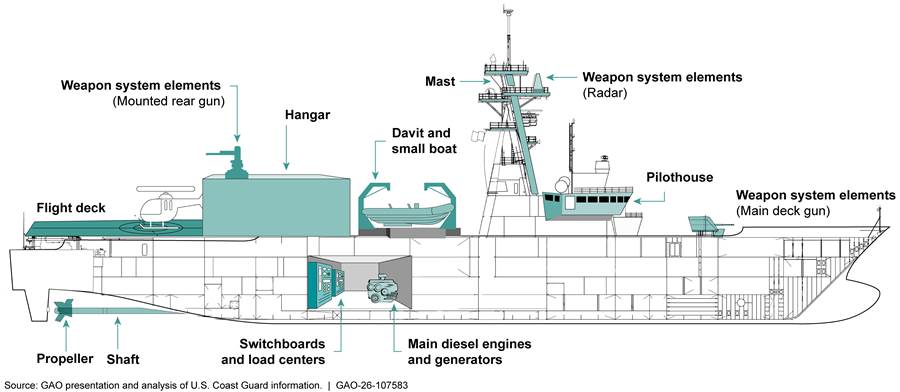

The OPC has key equipment and systems that enable the cutter to perform its various missions. For example:

· Main diesel engines. Main diesel engines provide power for propulsion of the cutter. The OPC will feature two main propulsion diesel engines.

· Power and electrical systems. Power onboard the OPC is provided via ship diesel generators. Switchboards connect the ship’s power generators to the ship’s electrical system, which includes load centers, power panels, and transformers.

· Weapon systems. Weapon systems provide defensive capabilities used in some operations. The OPC will feature Navy weapon and radar systems.

· Flight deck and hangar. The OPC flight deck and hangar are designed to operate one H-60 or H-65 helicopter at a given time.

· Pilothouse. The pilothouse on the OPC holds major navigational equipment, as well as throttle and electrical propulsion controls. The pilothouse also holds major communication equipment and aircraft control systems.

· Propulsion system. The propulsion systems on the OPC include propellers and shafts, among other things. The propeller is the mechanism used to generate thrust to move a ship or boat through the water. The shaft directs the power generated by the engine to the propellers, which then provide thrust for the vessel.

· Davit and small boats. The davit is a crane responsible for deploying and retrieving the cutter’s small boats from their carrying position on the deck of the cutter. The Coast Guard identified the davit as a critical technology for the OPC. The OPC davit technology is novel in that the dual-point electric motor system is integrated with constant tensioning. Other cutters in the Coast Guard fleet—including the MECs—use davits with a hydraulic motor system. According to the OPC program’s KPPs, the davit must be capable of launching and recovering small boats in sea state 5, which refers to rough conditions with 8- to 13-foot waves. Each OPC will have two davits—one located on each side of the deck—and carry three small boats.

Figure 2 depicts selected equipment and systems at their approximate locations on the OPC, which is to have a steel hull with an aluminum superstructure.

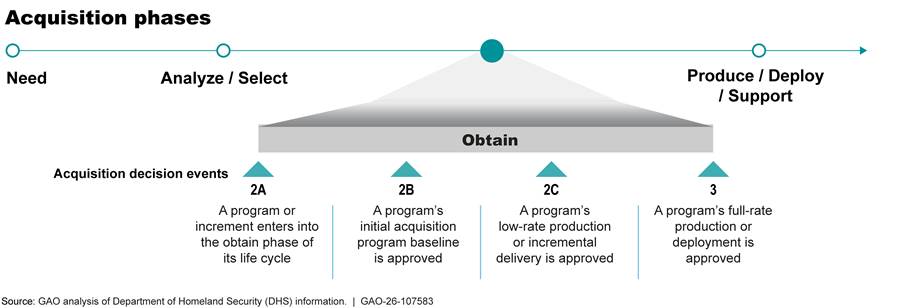

OPC Program’s Acquisition Life-Cycle Framework

The Coast Guard manages and oversees the OPC program using DHS’s acquisition life-cycle framework.[12] DHS’s acquisition policy establishes that a major acquisition program’s decision authority shall review the program at a series of predetermined acquisition decision events (ADE) to assess whether the program is ready to proceed through the acquisition life-cycle phases. The DHS Under Secretary for Management serves as the OPC’s acquisition decision authority, while the Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard serves as the component acquisition executive, or the senior acquisition official within the Coast Guard. Figure 3 depicts DHS’s acquisition life-cycle framework.

DHS acquisition policy also establishes that the acquisition program baseline is the fundamental agreement between program, component, and department-level officials establishing what should be delivered, how it should perform, when it should be delivered, and what it should cost. Specifically, the program baseline establishes a program’s schedule, costs, and KPPs, and covers the entire scope of the program’s life cycle. The acquisition program baseline establishes objective (target) and threshold (maximum acceptable for cost, latest acceptable for schedule, and minimum or maximum acceptable for performance) parameters. We refer to the threshold parameters as a goal.

According to DHS policy, if a program fails to meet any schedule, cost, or performance threshold in the acquisition program baseline approved at or after ADE 2B, it is considered to be in breach. Programs in breach status are required to notify their acquisition decision authority and (1) develop a remediation plan that outlines a time frame for the program to return to its acquisition program baseline parameters, (2) rebaseline—that is, establish new schedule, cost, or performance goals—or (3) have a DHS-led program review that results in recommendations for a revised baseline.

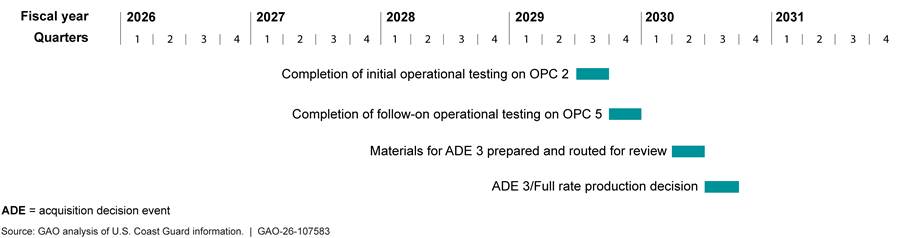

Figure 4 provides an overview of selected ADE and other key events for the OPC program from April 2012 through August 2024.

Figure 4: Selected Major Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) Acquisition Milestones and Key Events, April 2012 Through August 2024

Within the Coast Guard, the OPC program office is responsible for planning and executing the program according to its acquisition program baseline. The office is led by a program manager and includes a project residence office, which comprises personnel located at each OPC shipyard to provide on-site oversight of design and construction activities. Various other stakeholders, including offices from across DHS and the Department of Defense, also provide support to the OPC program in the following key areas:

· Design. The Coast Guard’s ship design team, within the Office of Naval Engineering, is responsible for reviewing and approving design drawings and other artifacts, assessing design maturity, and providing other technical assistance to the OPC program office. The American Bureau of Shipping—a third-party classification society—is responsible for reviewing and approving selected design artifacts and conducting inspections to verify that ships comply with the naval vessel rules outlined in the OPC contracts.

· Cost estimating. The Navy’s Naval Sea Systems Command Cost Engineering and Industrial Analysis Group, known as NAVSEA 05C, assists with developing and updating the OPC cost estimate. DHS’s Cost Analysis Division conducts independent cost assessments of the OPC cost estimate to determine whether the estimate is credible.

· EVM compliance and oversight. DCMA—a defense agency that provides contract administration services to the Department of Defense and other federal agencies—conducts compliance reviews of shipbuilder EVM systems and assists with monitoring EVM data. The Navy’s SUPSHIP conducts routine oversight of selected shipbuilder EVM systems.

· Test and evaluation. The Navy Operational Test and Evaluation Force serves as the program’s independent test agent. In this role, it is responsible for planning, conducting, and reporting on test and evaluation events to determine if systems meet performance requirements. DHS’s Test and Evaluation Division approves major test plans and independently assesses test results prior to ADE 2C and 3.

OPC Shipbuilders and Contract Type

The Coast Guard relies on private shipyards to build the OPC fleet, as described in table 2.

|

|

Stage 1 |

Stage 2 |

Stage 3 |

|

Shipbuilder |

Eastern Shipbuilding Group, Inc. |

Austal USA |

To be determined |

|

Number of planned OPCs |

4 (OPCs 1-4) |

11 (OPCs 5-15) |

10 (OPCs 16-25) |

|

Estimated time frame for detail design and construction |

2016–2028 |

2022–2033 |

To be determined |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO‑26‑107583

ESG—the stage 1 shipbuilder—is an American-based shipbuilder located in Panama City, Florida. Founded in 1976, ESG began building commercial fishing vessels before expanding production to offshore supply vessels, tugs and towboats, ferries, and other types of vessels. OPC was the company’s first shipbuilding contract with the government. In October 2018, as ESG was about to begin construction on OPC 1, Hurricane Michael—a category 5 storm—made landfall in the Panama City, Florida area. The hurricane caused widespread damage to the shipbuilder’s facilities, significant disruption to its workforce, and depletion of its financial working capital. Determining it was no longer able to perform to the terms of the contract, ESG requested both schedule relief and cost relief from the Coast Guard. In October 2019, the Acting Secretary of Homeland Security determined that the OPC is essential to national defense and authorized a maximum amount of $659 million in extraordinary contractual relief pursuant to Public Law 85-804 for detail design and the construction of up to four OPCs.[13] The Acting Secretary based the relief amount, in part, on an analysis that determined it was necessary to restore ESG’s working capital to prevent ESG’s financial insolvency. As of May 2025, the Coast Guard obligated approximately $581 million (88 percent) of the $659 million extraordinary contractual relief.

Austal—the stage 2 shipbuilder—is located in Mobile, Alabama and is a subsidiary of Austal Limited, an international shipbuilding company based in Australia. The company was founded in 1999 and has been a major shipbuilder for the Navy for several years.[14] Known for building aluminum ships, Austal completed a steel shipbuilding facility at its shipyard and began construction of its first steel ship—one of the Navy’s Navajo class of towing, salvage, and rescue ships (T-ATS)—in 2022.[15] In 2024, Austal initiated construction of a new final ship assembly facility, which is expected to be completed and fully operational by summer 2026. This facility is intended to support production of two OPCs at a time.

The OPC stage 1 and 2 contracts are primarily fixed-price incentive (firm-target) type contracts.[16] This type of contract specifies several contract elements including a profit adjustment formula referred to as a share line. In accordance with the share line, the government and the shipbuilder share responsibility for cost overruns (increases) or cost underruns (decreases) compared with the agreed upon target cost. The final negotiated cost is subject to a ceiling price, which is the maximum that may be paid to the contractor, except for any adjustment under other contract clauses. Generally, the share line functions to decrease the shipbuilder’s profit as actual costs exceed the target cost. Likewise, the shipbuilder’s profit increases when actual costs are less than the target cost for the ship. Since the shipbuilder’s profit is linked to actual performance, fixed-price incentive (firm-target) type contracts provide an incentive for the shipbuilder to control costs. The Navy also uses these types of contracts for most of its shipbuilding programs.[17]

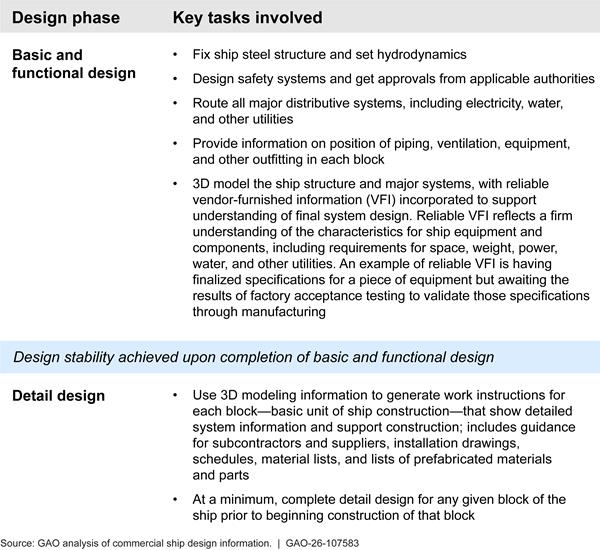

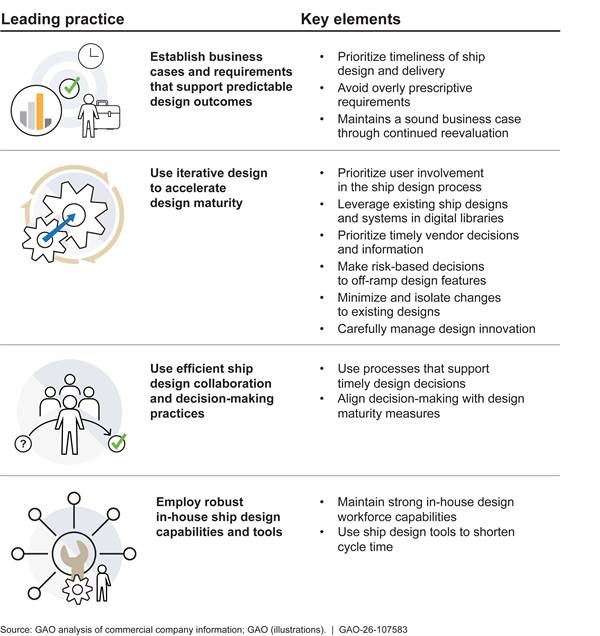

Shipbuilding Leading Practices

Since 2009, we have applied leading practices that we identified in commercial shipbuilding to our work evaluating Coast Guard and Navy shipbuilding.[18] These practices emphasize ensuring high levels of knowledge at key junctures throughout the acquisition process to achieve successful results. For example, shipbuilding leading practices we identified in 2009—and updated in 2024—found that design phases should include specific tasks that ensure increasing degrees of maturity as designs progress. This approach supports timely and predictable outcomes, such as delivering ships on time and on budget. These tasks culminate in design stability, as described in figure 5.

Figure 5: Ship Design Phases and Key Tasks Identified in Prior Work on Leading Commercial Shipbuilding Practices

Note: Ship buyers and builders may use different terms to denote the design phases. However, the tasks completed are the same regardless of terminology.

According to shipbuilding leading practices, lead ship construction should not start until design stability is achieved.[19] For Coast Guard programs, lead ship construction is generally authorized at ADE 2C.[20] In addition to completing basic and functional designs, any critical technologies—hardware and software technologies critical to the fulfillment of the key objectives of an acquisition program—must be matured and proven before a design can be considered stable. Specifically, leading practices that we identified for shipbuilding call for programs to require critical technologies to be matured into actual prototypes and successfully demonstrated in an operational or a realistic environment, commensurate with a technology readiness level (TRL) of 7, before the award of the contract for detail design of a new ship.[21]

We previously determined that the Coast Guard’s design terminology definitions—along with their associated outputs—generally align with our definitions.[22] Table 3 crosswalks these definitions and describes the design phases that typically comprise the development of shipbuilding programs.

|

Shipbuilding leading practices terminology |

Coast Guard terminology |

Description |

|

Basic design |

Preliminary and contract design |

Preliminary and contract design includes establishing the hull form, general arrangements of compartments, and outlining significant ship steel structure. Some routing of major equipment and related major distributive systems, including electricity, water, and other utilities is done. It also ensures the ship will meet the performance specifications, informs overall ship cost, facilitates shipbuilders’ development of acceptable proposals, and identifies major equipment and components that must be purchased in advance. |

|

Functional design |

Functional and transitional design |

Functional design includes providing a further iteration of the basic design through 2D design artifacts showing the size and positioning of structural components, information on the positioning of major piping and other distributive systems and outfitting in each block—or basic building unit for a ship. Transitional design is an iteration of functional design where the specific locations of equipment, components, and distributive systems are further refined. For programs that use computer design tools, transitional design is when 2D design drawings are turned into a 3D design model. |

|

Detail design |

Production design |

Production design includes generating work instructions that show detailed system information and guidance for subcontractors and suppliers to support construction, including installation drawings, schedules, material lists, and lists of prefabricated materials and parts. As part of this, the shipyard requires final technical data for key components prior to developing the work instructions. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO‑26‑107583

Note: The table reflects definitions of design phases based on our shipbuilding leading practices, as well as Coast Guard information. We compiled this table with input from the Coast Guard, but specific definitions may vary depending on the program.

In May 2024, we also identified leading practices for ship design.[23] Specifically, we found that commercial ship buyers and builders use four primary leading practices, supported by 13 key elements, when developing a ship’s design. These practices enable shorter, predictable cycles for designing and delivering new ships, as outlined in figure 6.

OPC Design Remains Incomplete Even Though Construction Is Underway

Construction for stages 1 and 2 is underway, but the OPC design remains incomplete. For stage 1, we found that ESG made limited progress since we last conducted an in-depth review of the program in 2023 and has yet to deliver any ships. Delivery of the lead ship has been further delayed to December 2026 at the earliest. In July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated OPCs 3 and 4 for default and has yet to decide how to complete them. For stage 2, we found that Austal incorporated some key elements of our ship design leading practices but started construction on its lead ship—OPC 5—in August 2024 without a stable design.

Limited Stage 1 Design and Construction Progress Further Delayed Ship Deliveries

ESG made limited progress completing design and construction of stage 1 ships since we last reported on the program in 2023. This limited progress further delayed ship deliveries. The Coast Guard took steps to address ESG’s limited progress on OPC 1 by modifying the contract to include additional payments if ESG meets certain milestones, such as successfully testing the davit. However, these steps were largely unsuccessful, and OPC 1 delivery slipped two more times due to persistent unresolved challenges, such as completing the stage 1 davit. In July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated for default the OPC 3 and 4 portions of the stage 1 contract and estimated that OPC 1 would not be delivered until December 2026 at the earliest.

Stage 1 Design and Construction Progress Has Been Limited

In June 2023, we found that important elements of the stage 1 design were incomplete despite the Coast Guard authorizing construction of all four ships.[24] Based on our review of design documentation, the percentage of completed 2D design drawings increased only 2 percent since our last report—from 91 percent in March 2023 to 93 percent in May 2025. The remaining 7 percent of incomplete drawings have technical or administrative comments that ESG has yet to resolve. As of May 2025, each of these drawings ranged from 50 to 90 percent complete based on the amount of work that would be required to finish them. The incomplete drawings relate to the davit and distributive systems—such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); cabling; and electrical—that run throughout multiple zones of the ship.

Coast Guard officials stated that one of the reasons for the lack of functional design progress was the interrelated nature of the design drawings. Specifically, ESG’s revisions to address open comments from the Coast Guard or American Bureau of Shipping often resulted in new comments or required changes in other related drawings that were previously approved. For example, officials stated that ESG made changes to a design containing cable data for all electrical, electronic, control and communications systems, which necessitated changes in other wiring diagrams to resolve inconsistencies between them. Officials also attributed the lack of progress to ESG not addressing open comments. They stated that ESG has not resubmitted some incomplete drawings since 2021 or 2022.

In some cases, ESG chose to continue construction with the hope that testing would demonstrate that the issues raised in the design comments would not affect performance. For example, ESG representatives told us that some of the open comments on the HVAC design are related to 90-degree angle duct turns, which they said do not meet the Coast Guard’s design specifications. They stated that future testing may show that the HVAC system meets performance requirements, despite the angle of some of the duct turns.

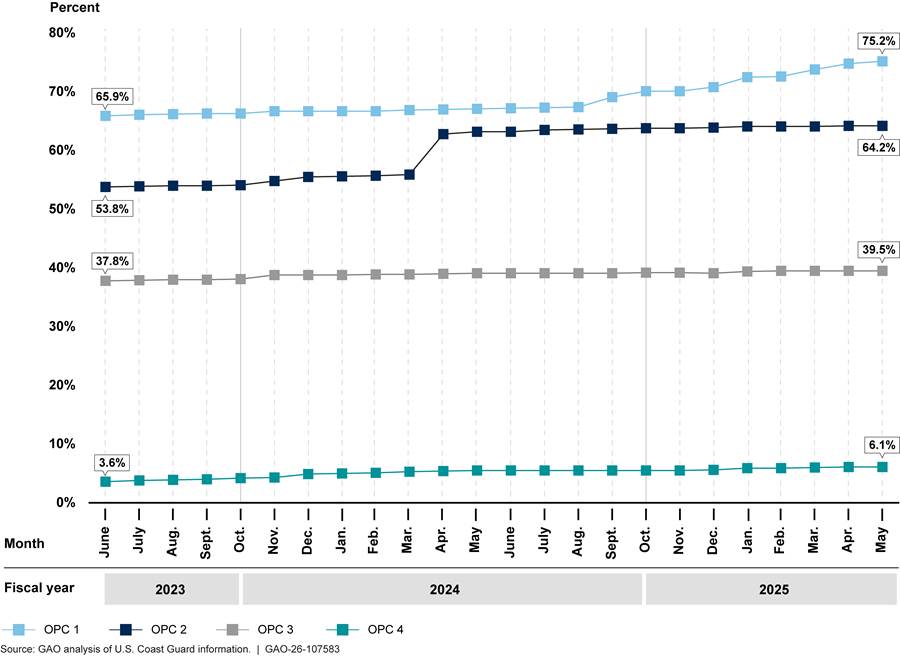

Coast Guard officials stated that this design instability continues to lead to rework, which has made it difficult for ESG to complete construction of stage 1 ships. Figure 7 shows construction progress for all four stage 1 OPCs since we last reported on the program.

Figure 7: Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) Stage 1 Construction Completion Percentage by Ship, June 2023 Through May 2025

Notes: Coast Guard officials stated that the OPC 2 completion percentage increased from March 2024 to April 2024 due to a change in software that resolved data errors.

In July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated for default the OPC 3 and 4 portions of the stage 1 shipbuilder’s contract.

Coast Guard officials explained that ESG had to undo and redo work because it initially completed it out-of-sequence. Officials stated this was, in part, because ESG underestimated the complexity of outfitting systems on the OPC due to its inexperience with government shipbuilding. For example, Coast Guard officials told us that some cutouts that allow for cabling and other distributive systems to transit between compartments on the OPC had to be redone because they were too small or in the wrong location. As a result, in some cases, ESG had to uninstall the cabling and other distributive systems and reinstall them in the proper cutouts. In other cases, cables had to be routed in other areas. For example, when we toured OPC 1 in December 2024, officials showed us a compartment in which cables had been run through spaces originally reserved for future OPC modernization, such as installation of new cables and equipment. Using this space now could make future modernization efforts more challenging.

|

Dense Arrangement of Systems on the Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) OPC is designed to meet survivability and system redundancy requirements. Coast Guard officials stated that these requirements exceed those of commercial ships that the stage 1 shipbuilder, Eastern Shipbuilding Group, is used to building. As a result, systems on the OPC are more densely packed, which reinforces the importance of completing work in the proper sequence. See, for example, cables and pipes installed close together on OPC 1, as of December 2024.

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Coast Guard information; U.S. Coast Guard (photo). | GAO-26-107583 |

We previously reported that installation work of distributive systems can be complex, resource intensive, and high risk.[25] Coast Guard officials told us during our site visit of instances in which ESG had to remove cables after installing them so that hot work, such as welding, could be completed without causing damage or igniting installed equipment. We previously reported that entering construction with unstable designs, including incomplete distributive systems, can disrupt the planned sequence of construction and lead to schedule delays.[26] As of May 2025, the Coast Guard estimated that the cable installation drawing, including cableway locations, was 70 percent complete. Completing installation of cables is a critical step to outfitting the ship.

Another factor limiting ESG’s progress on OPC 1 is that it launched the ship in October 2023 with over one-third of construction remaining.[27] Shipbuilding leading practices indicate that shipbuilders should complete as much design and installation of distributive systems as possible prior to erecting units and again before launching the ship. This is because it is generally less efficient to perform work on a ship after launch and more expensive in the later stages of construction.[28]

Steps to Address Limited Progress Have Been Unsuccessful

In June 2024, the Coast Guard took steps in response to ESG’s limited construction progress on OPC 1 by modifying the stage 1 contract. Specifically, the Coast Guard:

· Increased the share line for cost overruns. The Coast Guard revised the share line for OPC 1 to significantly increase the government’s share of cost overruns. According to an assessment conducted by the program, officials determined that there could have been adverse financial effects on ESG and the government’s receipt of OPC 1 if the share line was not adjusted.

· Increased the price and tied payments to completing milestones. The Coast Guard increased the target and ceiling price for OPC 1 by $77 million. The program funded the price increase by reducing the OPC 4 ceiling price and removing the OPC 4 target profit, together with adding a portion of the remaining Public Law 85-804 funds. The program tied payment of the $77 million to completion of four milestones. Approximately 58 percent of the price increase was tied to three milestones that include successfully testing major equipment, such as the main engine and diesel generator. The remaining 42 percent is tied to the fourth milestone—OPC 1 delivery. The milestones did not have deadlines but, according to Coast Guard documentation, the Coast Guard’s expectation was that the price increase would enable ESG to deliver OPC 1 in May 2025.

· Revised the retentions. The Coast Guard revised the retentions for OPC 1.[29] This change increased the amount of Coast Guard-reserved funding to cover the cost of completing any unfinished work or correcting any defects for which ESG is responsible that are found prior to preliminary acceptance or during the warranty period of any ship. Specifically, the Coast Guard increased the amount from 1.5 percent of the allocated total contract price—which officials estimated to be around $6 million—to approximately $29.5 million, which is 7 percent of the increased target price. According to program documentation, the Coast Guard revised the retention to mitigate risks to the government based on known noncompliance with contract specifications anticipated at delivery of OPC 1.

Program officials stated that they track potential and realized noncompliance issues throughout the construction process, which are regularly communicated to ESG as corrective action requests. As of May 2025, there were 1,200 open corrective action requests for OPC 1. Program officials categorized 243 of these (or 20 percent) as major noncompliance issues. These major noncompliance issues included installation of parts made of noncompliant materials, missing fire insulation, and failing to make compartments watertight. The Coast Guard could use the retained amounts to fix these issues if they remain when ESG delivers OPC 1.

Following the June 2024 contract modifications, ESG took steps to prioritize delivery of OPC 1 by adjusting its workforce. Specifically, it diverted labor from OPCs 2-4 to OPC 1 and started a second shift of workers since Coast Guard officials stated that there are constraints on the number of workers that can physically work inside OPC 1 at the same time. As shown in figure 7 above, construction progress on OPC 1 increased 8 percent from June 2024 to May 2025 while progress on OPCs 2-4 remained stagnant.

|

Status of Outfitting Work on Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPC) When we visited the OPC stage 1 shipbuilder, Eastern Shipbuilding Group (ESG) in December 2024, we observed that most OPC 2 modules were already assembled with minimal outfitting, including cabling. ESG officials stated that they intend to begin installing cables on OPC 2 once further progress on OPC 1 is achieved to reduce out-of-sequence work and rework. The photos below compare outfitting progress in the crew mess on OPC 1 (top) and OPC 2 (bottom), as of December 2024.

Source: GAO analysis of ESG information; U.S. Coast Guard (photos). | GAO-26-107583 |

However, Coast Guard officials stated that ESG’s efforts to increase the workforce on OPC 1 had not met the program’s expectations. For example, they stated that the number of workers on OPC 1 has fluctuated over time. They further stated that this is, in part, because ESG has struggled to hire and retain qualified workers, resulting in the company needing to hire more inexperienced workers. This has affected efficiency. We previously found that these types of workforce challenges are experienced across the shipbuilding industrial base.[30] As a result, ESG has struggled to complete the milestones associated with finishing construction of OPC 1. By November 2024, estimated delivery of the lead ship slipped by 6 months—from May 2025 to November 2025.

In addition, ESG requested more funding from the Coast Guard. In March 2025, ESG submitted a request to the OPC program for further relief under Public Law 85-804 in the form of a $15 million cash infusion by the end of that month. ESG’s request stated that it needed the funds to maintain adequate working capital to ensure that OPC stage 1 remains executable. However, according to Coast Guard records, the program has only $11 million of Public Law 85-804 funds remaining for this purpose. Coast Guard officials told us that, as of May 2025, they were still reviewing ESG’s cash infusion request to determine whether the funding was necessary.

In the meantime, the Coast Guard issued stop work orders on OPC 4 in March 2025 and OPC 3 in May 2025. Officials stated that the Coast Guard issued these orders to minimize costs the government incurred for construction of the ships and give ESG a chance to further prioritize completing construction of OPC 1. In July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated for default the OPC 3 and 4 portions of the stage 1 contract, and officials stated that delivery of OPC 1 had been delayed further.[31] Specifically, ESG estimated that OPC 1 will be delivered in December 2026 at the earliest. The Coast Guard has not yet decided how it will complete construction of OPCs 3 and 4 in light of their termination.

Stage 1 Davit Challenges Continue

ESG continues to experience challenges with the stage 1 davit. We previously reported that ESG and its davit subcontractor encountered significant challenges in maturing the davit, which Coast Guard determined was a TRL 2—the equivalent to a technology concept— in 2020.[32] For example, in June 2023, we found that ESG’s davit subcontractor repeatedly redesigned the davit and developed new manufacturing approaches after identifying issues during developmental testing.[33] This led to delays in approving the davit’s design and completing testing of a prototype.

Since we last reported on the OPC program, the davit subcontractor held a series of prototype testing events because it continued to encounter challenges. For example, Coast Guard officials stated that testing attempted by the subcontractor in March 2024 failed because the davit prototype was unable to complete any of the tests and required constant troubleshooting. The subcontractor retested the prototype in September 2024 and conducted additional factory testing on the second davit for OPC 1 in February 2025.

Based on the recent testing, the Coast Guard’s ship design team reassessed the davit’s maturity level to TRL 5 since basic functionality was demonstrated in a laboratory environment. However, the Coast Guard’s ship design team also issued a memorandum to the OPC program in March 2025 that raised concerns about design issues, missing safety information, and insufficient testing.

· Design issues. Some davit components do not meet contractual requirements. This includes the constant tension motors that enable the davit to lower small boats safely. Coast Guard officials determined that the motors were not suitably rated for OPC launch and recovery efforts. Additionally, the electrical cabinet that houses some of the equipment to power the davit is planned to be installed outside. Officials determined that the cabinet would not properly protect the equipment, which requires a dry, temperature-controlled environment. Absent a controlled environment, risks include damage to equipment and operational failure.

· Missing safety information. The davit subcontractor had yet to provide fail safe and reliability data to the Coast Guard for certain single-point failure components—meaning failure of those components would result in failure of the entire davit—which increases the risk of free fall and personnel injury during davit operations.

· Insufficient testing. The davit subcontractor did not have a plan to perform electromagnetic interference testing and vibration testing, both of which are contractually required. Additionally, the subcontractor had yet to fully test the davit system or components for enough time or distance to verify performance. The ship design team recommended that the program require further testing to determine whether operational restrictions should be placed on the davit.

In April 2025, Coast Guard officials stated that further testing would be conducted on the stage 1 davits once they were installed on OPC 1. For example, they stated that the subcontractor developed a plan to conduct vibration testing and electromagnetic interference testing in June and July 2025, respectively. If further testing demonstrates that the davit technology is not mature enough to support OPC 1 delivery, officials stated that they would proceed with installing a legacy davit system used on other Coast Guard cutters during post-delivery. This would enable OPC 1 to perform the basic function of launching and recovering a small

boat, though not in sea state 5, as identified in the stage 1 contract. In this scenario, ESG would still be responsible for delivering the contractually compliant davit for its stage 1 ships but would have more time to develop it. Additionally, the Coast Guard would have to replace the legacy davit with one that meets the program’s sea state 5 requirement once it becomes available. However, given the continued technical challenges ESG’s subcontractor has encountered developing the stage 1 davit, it is unknown when ESG will be able to deliver a contractually compliant davit.

|

Use of Davit in Sea State 5 In 2010, the Coast Guard conducted a study and determined that sea state 5 small boat operations were a critical and essential characteristic for its medium-range security cutters. The study, which formed the basis of the Offshore Patrol Cutter’s (OPC) key performance parameters, found that nine of the Coast Guard’s 14 operating areas had an average sea state of 5 or greater for at least 50 percent of the year. According to the Coast Guard, there is currently no davit on the market that can launch and recover small boats in sea state 5. Both the 210-foot and 270-foot Medium Endurance Cutters can conduct small boat operations in conditions up to sea state 4, meaning operations are unsafe in a significant percent of key operating areas. A davit that meets the contract specification for small boat operations in sea state 5 will enable the OPCs to conduct these operations more routinely and frequently in assigned operational areas. Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Coast Guard information. | GAO-26-107583 |

As summarized in appendix II, we previously made several recommendations regarding the stage 1 davit, which the Coast Guard has yet to fully address. For example, in June 2023, we made two recommendations related to maturing the stage 1 davit, including that the Coast Guard (1) should develop a davit technology maturation plan prior to builder’s trials that includes a date by which the program will make a go/no-go decision to pursue a technology alternative, and (2) test an integrated prototype of the davit in a realistic environment prior to builder’s trials.[34] DHS concurred with these recommendations, but the Coast Guard has yet to take the actions needed to implement them.

Stage 2 Incorporated Some Leading Ship Design Practices, but Construction Began Without a Stable Design

The Coast Guard and Austal incorporated some leading practices for ship design into OPC stage 2 but began construction of the lead ship—OPC 5—without achieving a stable design. This approach is contrary to shipbuilding leading practices, which emphasize the importance of achieving a stable design before starting construction to reduce cost and schedule risk.

Leading Ship Design Practices Incorporated into Stage 2

The Coast Guard and Austal incorporated some key elements of our leading practices for ship design into OPC stage 2, such as leveraging existing designs, minimizing changes to existing designs, maintaining strong in-house design workforce capabilities, and using processes that support timely design decisions. This approach contributed to developing a substantial amount of the design in less than 2 years after contract award. Specifically, the Coast Guard and Austal took the following actions:

· Leveraged existing ship designs and systems. Leading commercial shipbuilding companies draw heavily from their existing designs to speed design maturity and reduce risk. Use of proven ship designs and vendors for major equipment and systems also minimizes design, cost, and schedule uncertainties. In the OPC stage 2 contract, the Coast Guard required certain elements of the design and major equipment to be the same as stage 1. These included the hull form, propulsion system, main diesel engines and generators, and machinery control system. The Coast Guard also provided other information on the stage 1 design. According to Austal representatives, they assessed this information to determine what other elements of the stage 1 design they could leverage. For example, Austal chose to work with the same subcontractor for integrating the ship’s communications systems.

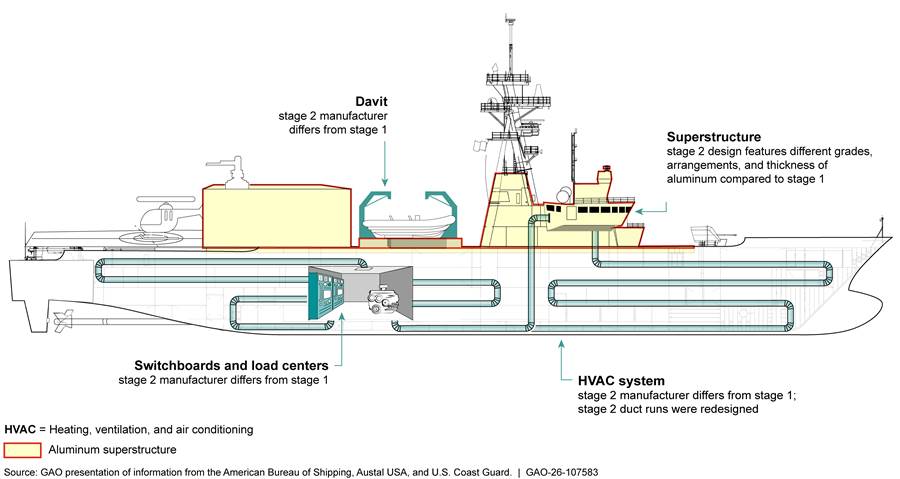

· Minimized changes to existing designs. Commercial shipbuilders minimize changes made to existing ship designs to preserve design maturity and reduce the total work required for new ship designs. For OPC stage 2, Austal focused design changes on where the stage 1 design was incomplete, or where the company anticipated that it could achieve major efficiencies. For example, Austal representatives stated that redesigning the piping systems eliminated 20 percent of needed pipe and 1,000 valves. They also redesigned the ship structure, which reduced the estimated weight by 163 long tons. In addition, Austal selected different manufacturers for certain equipment, including the davit. Coast Guard officials noted that the stage 2 design is functionally the same as stage 1. But there are some differences, as described in figure 8.

· Maintained strong in-house design workforce capabilities. Commercial shipbuilders use their own personnel to perform most of the design work for the ships they build. This allows builders to make decisions that align the ship’s design with the shipyard’s characteristics to create an efficient build strategy. Coast Guard officials said that Austal has strong, in-house design workforce capabilities and, therefore, used fewer subcontractors than ESG. These officials also said that Austal tailored the design to better align it with the shipyard’s manufacturing process and “center-up” build strategy to increase efficiencies.[35]

· Used processes that support timely design decisions. Commercial ship buyers and builders use consistent, effective collaboration to support timely decision-making practices, which hastens design maturity. Consistent with shipbuilding leading practices, Austal developed a 3D model of its OPC design and used this model to conduct regular, collaborative reviews with the Coast Guard throughout the design process. The Coast Guard cited these reviews as a tool to catch design problems early and speed up review times. For example, during one review, the Coast Guard identified a pipe connection issue in the 3D model that would have been difficult to catch in a 2D drawing and likely would have gone unnoticed until the valve was installed. The Coast Guard estimated that identifying the issue in the 3D model avoided at least 64 labor hours to correct the issue later.

Construction of the Stage 2 Lead Ship Started Without a Stable Design

Even though the Coast Guard and Austal incorporated some elements of ship design leading practices, the Coast Guard authorized Austal to begin construction of OPC 5 in August 2024 without achieving a stable design or maturing the davit. As of May 2025, construction of OPC 5 progressed to 9 percent. Delivery was expected in August 2027 but, as of May 2025, Austal reported that delivery of OPC 5 could be delayed by almost 4 months. Coast Guard officials said that Austal attributed the potential delay to a lack of available pipe material and qualified pipe designers. However, Coast Guard officials stated that they do not agree with the delay and are working with Austal on the delivery schedule.

In June 2023, we recommended that the Coast Guard ensure that stage 2 achieves a sufficiently stable design prior to the start of OPC 5 construction by completing 100 percent of basic and functional design, including routing of major distributive systems that affect multiple zones of the ship.[36] This is consistent with our shipbuilding leading practices. As previously discussed, we updated these leading practices in May 2024 to emphasize the importance of completing basic and functional design in a 3D model and that 3D modeling should be supported by reliable vendor-furnished information on the characteristics of ship equipment and components.[37] Additionally, in June 2023, we recommended that the Coast Guard ensure the program or shipbuilder demonstrate an integrated prototype of any critical technologies—which would include the stage 2 davit—in a realistic environment no later than preliminary design review.

DHS did not concur with these recommendations and stated that design would be sufficiently stable when construction of OPC 5 began, in accordance with the Coast Guard’s policy. The Coast Guard has a standard operating procedure that establishes the design maturity parameters shipbuilding programs should achieve before moving into production. We previously identified that the standard operating procedure requires a lower level of design maturity than shipbuilding leading practices and recommended that the Coast Guard make changes to align with these practices.[38] The Coast Guard made some updates, such as requiring shipbuilding programs to complete major portions of distributive systems as part of functional design and to ensure any critical technologies are TRL 7 or higher prior to the start of construction. However, the standard operating procedure still falls short of shipbuilding leading practices. For example, the standard operating procedure requires that shipbuilding programs complete at least 95 percent of functional design and 70 percent of transitional design before construction begins.[39]

The Coast Guard met the design completion metrics in its standard operating procedure at the start of OPC 5 construction. However, we identified areas where the stage 2 design did not align with the standard operating procedure or our shipbuilding leading practices, which increases the risk of rework and schedule delays. Additionally, Austal has continued to mature the stage 2 design after starting construction, but it is not yet stable according to leading practices. Specifically, when construction began in August 2024:

· 2D design drawings of safety and distributive systems were incomplete. At the start of OPC 5 construction, the Coast Guard reported that 2D design was 95 percent complete. The remaining 5 percent were incomplete drawings that had not been submitted by Austal or had technical or administrative comments that had yet to be resolved with the Coast Guard. These included designs of safety systems, such as diagrams for the fire main, flooding detection, and other alarms, as well as major distributive systems, such as HVAC, sewage, and electrical. For example, Coast Guard officials estimated that the design containing cable data for all electrical, electronic, control and communications systems was only 50 percent complete. Additionally, the Coast Guard reported that the American Bureau of Shipping—a third party that verifies the ship complies with the naval vessel rules required in the contract—approved 36 percent of the design drawings at the start of OPC 5 construction. American Bureau of Shipping officials stated that their approvals focused on the design elements needed to support initial construction efforts, such as the primary structure.

As of May 2025, the Coast Guard reported that the percentage of completed 2D drawings increased to 98 percent and American Bureau of Shipping approvals increased to 70 percent. However, designs related to distributive systems, such as HVAC, water, and electrical, remained incomplete more than 9 months after construction began.

· 3D modeling of distributive systems was incomplete and did not include vendor-furnished information. At the start of OPC 5 construction, the Coast Guard reported that the 3D model was 81 percent complete. However, distributive systems including HVAC, electrical, and piping were fully modeled for only 5 of the 20 modules. The 3D model also did not include reliable vendor-furnished information for all major systems as called for by our leading practices. For example, vendor information for the communications systems was incomplete because Austal delayed the critical design review for these systems until after the start of construction. Coast Guard officials explained that the communications integration subcontractor switched one of its vendors leading up to the review and officials needed more time to vet the new vendor’s information.

Since the start of OPC 5 construction, Austal has made progress on the 3D model and the Coast Guard reported that it was 97 percent complete as of May 2025. This included full modeling for 16 of the 20 modules. The remaining four modules were 99 percent complete and waiting on full modeling of distributive systems, including piping and electrical. Additionally, information from the communications integration subcontractor was needed for the electrical system in eight modules. As of May 2025, the critical design review for the communications systems was now planned for August 2025.[40] Continued challenges with the communications systems could lead to construction delays, especially given Austal’s “center-up” build strategy.

· Davit for stage 2 was immature. At the start of OPC 5 construction, the Coast Guard and the American Bureau of Shipping had yet to fully approve the stage 2 davit design. Additionally, the Coast Guard assessed the davit at a TRL 5 (approaching maturity) instead of TRL 7 (mature). Testing of the stage 2 davit was expected in fall 2024 but has been delayed several times and is now planned for October 2025. American Bureau of Shipping officials stated that they had multiple technical comments on the davit design that should be resolved before testing occurs. As of June 2025, these officials estimated that the davit design was 45 percent complete. Coast Guard officials stated that, despite the delays, the testing will occur before the davit needs to be installed for builder’s trials. These trials were originally scheduled for March 2027 but have been delayed to July 2027. Additional delays to—or challenges resulting from—the stage 2 davit testing could delay its installation and other subsequent events, such as trials and delivery.

According to Coast Guard officials, detail design continues throughout the construction phase so that changes can be made, if necessary, while ships are on the production line. While we acknowledge that detail design is an iterative process, this design phase should not involve completing or making major changes to the basic or functional design because doing so contributes to design instability. Our previous work on shipbuilding leading practices found that production outcomes cannot be guaranteed until a stable design is demonstrated. Stabilizing the design of distributive systems that run throughout the ship is particularly important because any changes to these designs may have a reverberating effect across the ship. Fully modeling distributive and other major systems in a 3D model with reliable vendor-furnished information prior to construction minimizes the risk of design changes, which can become more costly and difficult to implement as construction progresses.

Given the importance of OPC and the program’s stated desire to stay on schedule, Coast Guard officials told us in December 2024 that they plan to exercise the option for construction of OPC 6 by August 2025 and OPC 7 by August 2026. However, the functional design may not be complete, and the davit may not reach a sufficient level of technology maturity before these dates. For example, the Coast Guard subsequently exercised the option to construct OPC 6 in August 2025 before the critical design review for the communications systems and testing of the stage 2 davit were complete. Authorizing Austal to begin construction of additional ships before it achieves a sufficiently stable design and successfully demonstrates the davit in a realistic environment increases the risk that stage 2 will encounter costly rework and schedule delays.

OPC Program Faces Challenges Meeting Its Revised Acquisition Goals

The OPC program faces challenges meeting the schedule, cost, and performance goals included in its most recent baseline that DHS leadership approved in August 2024. The thrice revised baseline established a ship delivery goal for OPC 1 but, in July 2025, the program breached this goal. Additionally, program costs have continued to increase, which puts the program’s cost goals at risk and undermines the stage 1 business case. Further, the Coast Guard risks buying more ships in stage 3 before operational testing demonstrates whether the existing OPC designs meet the program’s performance goals.

Program’s Schedule Goals Are No Longer Achievable and Will Need to Be Revised Again

In its August 2024 baseline, the program established ship delivery goals for OPCs 1, 4, 5, and 25 in response to our prior recommendations.[41] However, the Coast Guard did not have quality schedule information from the shipbuilders at the time it set these goals, and the program breached the delivery goal for OPC 1 less than a year later. Ongoing challenges with the shipbuilders’ schedules will hinder the Coast Guard’s ability to set realistic ship delivery goals in its next baseline.

Schedules are an important program management tool. They are also a critical component of EVM, which is used to assess a contractor’s performance against its planned schedule and budget. Both the stage 1 and stage 2 OPC contracts require the shipbuilders to have an acceptable EVM system.[42]

|

Key Management Tool: Earned Value Management (EVM) As described in our Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide (GAO-20-195G), EVM is a project management tool. EVM integrates the technical scope of work with schedule and cost elements, and compares the value of work accomplished in a given period with the value of the work expected in that period. When used properly, EVM can provide objective assessments of project progress, produce early warning signs of impending schedule delays and cost overruns, and provide unbiased estimates of anticipated costs at completion. Source: GAO. | GAO-26-107583 |

Stage 1’s Schedule Remains Deficient

The program revised its schedule goals for stage 1 despite known deficiencies with ESG’s schedule. Subsequently, the program breached its delivery goal for OPC 1—which was December 2025—and will need to develop a plan to remediate the breach, rebaseline, or have a DHS-led program review that results in recommendations for a revised baseline.

In October 2020, we found that ESG’s schedule contained several deficiencies, was overly optimistic, and did not fully incorporate schedule risks.[43] For example, ESG did not complete a schedule risk analysis to determine the probability of delivering the first ship by the contract delivery date until after the program had already revised the delivery dates following Hurricane Michael. We recommended that the Coast Guard update its shipbuilder and government schedules for OPCs 1-4 to fully address deficiencies identified in the shipbuilder’s schedule and fully incorporate schedule risk analysis in accordance with schedule best practices. DHS concurred with this recommendation, but the Coast Guard has yet to address it because ESG is reviewing its schedules for all stage 1 ships—an effort that has been ongoing for more than 18 months.

In July 2023, ESG began reviewing its schedules and costs for OPCs 1-4 after notifying the Coast Guard that it could not meet its revised contract delivery dates. The Coast Guard acknowledged several reasons for the review including large design changes, ESG not leveraging lessons learned, and management practices. ESG paused reporting of some EVM data while it conducted these reviews since the data no longer reflected performance. By the time the OPC program revised its baseline in 2024, ESG had only completed its review for OPC 1 and projected delivery for that ship in May 2025. ESG also completed a schedule risk analysis of its revised OPC 1 schedule. We reviewed this analysis and found it was optimistic and did not include all elements of a comprehensive schedule risk analysis. For example, the analysis did not capture several known risks, such as incomplete design and workforce challenges. As previously mentioned, estimated delivery of OPC 1 has since been delayed twice due to these challenges—from May 2025 to November 2025, and now to December 2026 at the earliest.

In April 2025, Coast Guard officials stated that ESG had revised its schedule for OPC 2 but the reviews of OPCs 3-4 were ongoing.[44] However, these officials stated that they would not approve ESG’s revised schedule for OPC 2 until more progress is achieved on OPC 1. Specifically, the program plans to wait at least until OPC 1 begins builder’s trials. Officials stated that, by waiting, the program would have greater confidence in ESG’s ability to achieve its revised schedule. However, as discussed, ESG has struggled to complete construction of OPC 1 and the Coast Guard terminated for default the portions of the stage 1 contract for construction of OPCs 3 and 4 but has yet to decide how it will complete them.

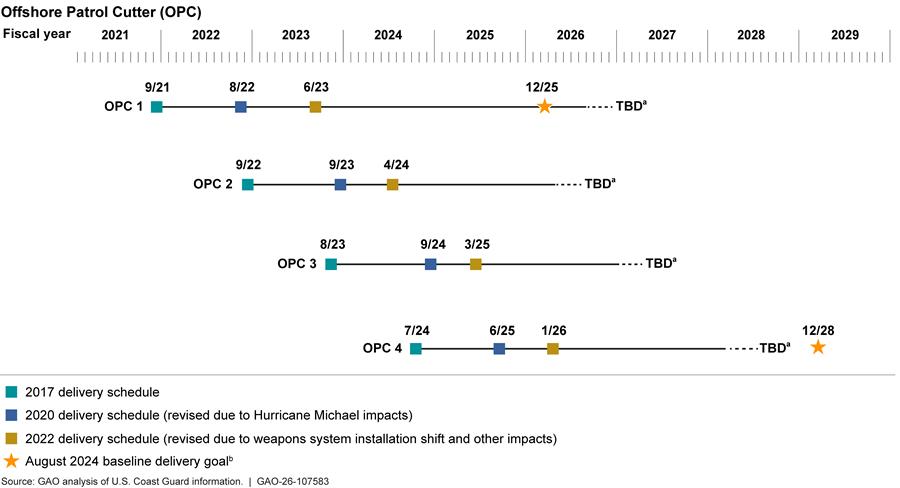

We previously reported that the planned delivery for OPCs 1-4 have been delayed multiple times, as shown in figure 9.[45]

aDelivery of OPCs 1-4 are to be determined (TBD) because, in July 2025, the Coast Guard terminated for default the OPC 3 and 4 portions of its existing contract and stated that delivery of OPC 1 had slipped to December 2026 at the earliest. The Coast Guard has yet to determine how this delay will affect delivery of OPC 2.

bBecause the estimated delivery of OPC 1 exceeds the program’s baseline delivery goal, the program is considered to be in breach. Per the Department of Homeland Security’s acquisition policy, programs in breach must develop a plan to remediate the breach, rebaseline, or have a department-led program review that results in recommendations for a revised baseline. As of July 2025, the Coast Guard’s efforts to address the breach were ongoing.

For example, the program delayed the delivery dates in 2020 to reflect relief granted to ESG following Hurricane Michael. The program also delayed the delivery dates in 2022 to account for its decision to install Navy equipment—including weapons and radar systems—on OPC 1 and OPC 2 during production instead of during the post-delivery period, as initially planned. In June 2023, we found that the program further delayed the delivery dates due to manufacturing issues with propeller shafting segments—the part of the propulsion system that transmits power from the engine to the propellers to generate thrust—which have subsequently been resolved.[46] The additional delays caused by continued design and construction challenges mean that ESG will deliver OPC 1 more than 5 years late if it is able to deliver by December 2026.

Until the Coast Guard implements our recommendation from October 2020 to fully address the deficiencies identified with ESG’s schedule, the program will not have reasonable assurance regarding when ESG can deliver OPC 1 and 2 to inform revising its baseline goals.

Stage 2 Schedule and EVM System Have Deficiencies

The program does not have reasonable assurance that its schedule goals for stage 2—including delivery of OPC 5 by March 2028—are realistic or achievable because the Coast Guard and DCMA identified deficiencies with Austal’s schedule and EVM system. Specifically:

· In February 2024, the Coast Guard sent Austal a letter of concern regarding the timeliness and quality of its schedule and other EVM deliverables required under the stage 2 contract. For example, the letter highlighted that Austal’s schedule did not reflect all work elements or contain contract milestones and discrete tasks from start to completion. In December 2024, Coast Guard officials told us that Austal had yet to provide a schedule that contained this information.

· In August 2024, DCMA completed an evaluation of Austal’s EVM system, which included a review of its schedule data.[47] DCMA found nine significant deficiencies with Austal’s schedule, such as missing milestones, lack of vertical integration with subcontractor schedules, and discrepancies between the schedule and risk register.[48] For example, the risk of completing the communications systems design was open in the OPC program’s risk register but closed in Austal’s schedule. Other risks we identified that could affect the stage 2 schedule include incomplete design and davit immaturity; Austal’s management of potential competing priorities between OPC and its other contracts; Austal’s ability to hire and retain the production workforce needed to support all its contracts; and timely completion of the new final assembly facility to support future OPC production rates.

DCMA also found 21 significant deficiencies with other aspects of the EVM system, some of which could affect Austal’s estimates at completion by making them artificially low.[49] DCMA determined the significant deficiencies that it found materially affect the ability of government officials to rely upon the information produced by Austal’s EVM system.

Coast Guard officials stated that Austal’s scheduling and EVM challenges were primarily due to not dedicating enough resources to these efforts, such as experienced staff. DCMA officials also stated that Austal uses its schedule and EVM system more for cost-tracking rather than program management tools, which is their intended purpose. For example, EVM data can allow programs to monitor cost and schedule progress, understand the estimated resources needed to complete the program, and course correct as needed to reduce the risk of cost overruns and schedule delays.[50]

Improper use of EVM—either due to system deficiencies or inaccurate data—can mask performance issues that have cascading effects. For example, Austal pleaded guilty in August 2024 to resolve an investigation by the Department of Justice into a fraud scheme in which, according to court documents, Austal artificially suppressed the EVM system’s estimates at completion for the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship from around 2013 to 2016 to increase the price of its parent company’s stock.[51] The Department of Justice reported that this falsely overstated Austal’s profitability on the program and its parent company’s earnings in public financial statement filings by over $100 million.

Coast Guard officials stated that they are working with Navy’s SUPSHIP to address the deficiencies DCMA found with Austal’s EVM system. SUPSHIP is responsible for oversight of Austal’s EVM data for Navy contracts and has a process for engaging with contractors on EVM system deficiencies. SUPSHIP initiated its process with Austal in December 2024 by taking the following steps:

· Issuing an initial determination. SUPSHIP issued an initial determination on Austal’s EVM system in December 2024. This determination requested that Austal respond if it disagreed with DCMA’s findings, including its rationale for disagreement. In its response, Austal disagreed with half of DCMA’s findings either because it did not believe a significant deficiency existed or it disagreed with DCMA’s determination that a deficiency was significant.

· Issuing a final determination. Based on Austal’s response to its initial determination, SUPSHIP issued a final determination on Austal’s EVM system in February 2025. This determination concurred with some of Austal’s disagreements but determined that 18 significant EVM deficiencies remained. As a result, SUPSHIP disapproved Austal’s EVM system and began withholding 5 percent of eligible payments under one of the Navy’s contracts.[52] SUPSHIP officials told us that it considered withholding payments under other Navy contracts but determined that doing so was unnecessary. Specifically, they determined that withholding payments under one contract would incentivize Austal to correct the deficiencies in a timely manner. They also stated that withholding payments under additional contracts may adversely affect Austal’s financial position and jeopardize its ability to deliver under its contracts. SUPSHIP’s final determination also included requests for Austal to develop corrective action plans to address the deficiencies with its EVM system.

· Assessing corrective action plans. Austal delivered its corrective action plans for addressing the 18 significant deficiencies to SUPSHIP in March 2025, which SUPSHIP approved in April 2025. SUPSHIP officials told us that Austal has demonstrated a commitment to resolving the deficiencies, but—given the volume and significance of some of the deficiencies—it may take 1-2 years to do so.

As described above, the stage 2 OPC contract includes clauses that allow the Coast Guard to disapprove Austal’s EVM system and withhold a percentage of eligible payments. However, Coast Guard officials stated that they did not plan to take any action under these clauses because they are coordinating with SUPSHIP and SUPSHIP’s process is working. Specifically, SUPSHIP’s determinations have incentivized Austal to develop corrective action plans to address the EVM system deficiencies. According to officials, successful implementation of the corrective action plans will result in system improvements that benefit all government contracts with Austal that have EVM requirements—including the OPC contract.

SUPSHIP and Coast Guard officials told us that they believe their existing coordination on Austal’s efforts to address EVM deficiencies is sufficient and presents a united front to Austal. SUPSHIP officials stated that they plan to invite the Coast Guard to regular meetings with Austal to discuss their corrective action plans and copy the Coast Guard on correspondence with Austal related to the EVM system. However, SUPSHIP officials did not specify what level of input the Coast Guard will have in the meetings or correspondence, and actions taken early on in SUPSHIP’s process did not account for the OPC program. For example, SUPSHIP and Coast Guard officials told us that the Coast Guard participated in the briefing in which SUPSHIP discussed options for withholding contract payments. However, these officials did not consider the OPC contract when SUPSHIP was analyzing options for withholding a portion of contract payments.

The Coast Guard and SUPSHIP do not have an agreement in place that outlines how the two organizations will coordinate as Austal works to improve its EVM system, which has implications for Coast Guard and Navy shipbuilding programs. SUPSHIP officials stated that they have developed agreements at other shipyards in the past and would support developing one with the Coast Guard for Austal. For example, such an agreement could include:

· What roles and responsibilities each organization will have in evaluating Austal’s progress implementing its corrective action plans,

· What steps they will follow for decision-making, such as determining when corrective actions are complete, conditions for increasing or decreasing any amounts withheld on Austal’s OPC or Navy contracts, as well as when to stop withholding any amounts on contract payments, and

· How they will coordinate once Austal addresses all the deficiencies to ensure Austal’s EVM system continues to generate reliable data.

Our prior work on enhancing interagency collaboration found that agencies that articulate their agreements in formal documents can strengthen their commitment to working collaboratively, which can help overcome significant differences when they arise.[53] Such documentation can provide consistency in the long term, especially when leadership changes. By establishing an agreement to guide its coordination, the Coast Guard and SUPSHIP will be better positioned to achieve their common goal of ensuring that Austal improves its EVM system and produces reliable data that the government can use to monitor schedule and cost performance throughout the duration of its contracts.

Continued Cost Increases Put Program’s Cost Goals at Risk and Undermines Stage 1 Business Case

The OPC program’s estimated acquisition costs continued to rise from 2022 to 2023. The Coast Guard used outdated information from the 2023 estimate when it rebaselined its cost goals in 2024. Further, the structure of the cost goals limits decision-makers’ opportunities for oversight. Finally, the underlying business case for stage 1 is no longer sound given continued cost growth. The Coast Guard has initiated a review of stage 1, which is ongoing.

OPC Acquisition Cost Estimate Increased