CIVILIAN TELEWORK AND REMOTE WORK

DOD Should Evaluate Programs in Relation to Department Goals

Report to Congressional Committees

GAO-26-107601

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Alissa H. Czyz, CzyzA@gao.gov

What GAO Found

Since 2020, the Department of Defense’s (DOD) telework and remote work policies have changed to reflect federal guidance on the use of these flexibilities by federal employees. In January 2025, DOD directed the return to in-person work for all employees in compliance with a presidential memorandum requiring all executive branch employees to work in-person on a full-time basis, with limited exceptions. According to officials, as of July 2025, about 8 percent (62,000 of 780,000) of DOD employees had not returned to in-person work, with 6 percent (45,000) of those due to deferred resignation status or other exemptions and another 2 percent (17,000) due to reasonable accommodations.

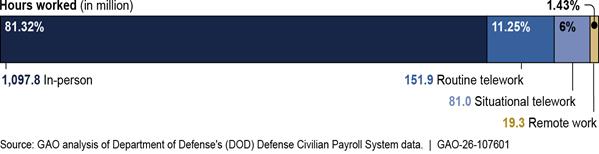

DOD data for pay periods ending in calendar year 2024 shows that most work was conducted in person.

GAO reviewed data for 13 selected dates from December 2021 through February 2025 and found that, although between 65 and 68 percent of DOD civilian employee positions were eligible for telework or remote work, data on actual employee eligibility were incomplete. Therefore, data on the number of teleworkers and remote workers DOD previously reported are likely inaccurate. For example, in May 2024, DOD publicly reported it had 61,549 remote employees. One month later in June 2024, DOD told GAO that it had 35,558 remote employees. The Office of Personnel Management and DOD policy require the collection of data about position and employee eligibility for telework and remote work, but DOD officials told GAO there is no formal process in place to ensure eligibility data are accurate, timely, or complete. Without formal processes for collecting data on employee eligibility, DOD lacks visibility into the use of these flexibilities and may not be able to ensure compliance with DOD policy to collect accurate and reliable data on use of these flexibilities.

DOD has not formally evaluated the effects of telework and remote work programs in relation to its agency goals, but officials reported perceived benefits and challenges. For example, officials told GAO their use of these flexibilities maintained or improved mission productivity and efficiency and supported employee recruitment and retention. Conversely, officials said that telework reduced opportunities for collaboration and information sharing and decreased morale and retention of employees ineligible for telework or remote work. Without clear and specific requirements for the formal evaluation of telework and remote work programs, DOD cannot determine if these programs help meet agency goals, including those related to recruitment and retention.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD’s use of telework and remote work flexibilities has evolved since the department first issued its policy over a decade ago, with peak usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2025, the President issued a memorandum directing all agencies to require employees to return to in-person work on a full-time basis, essentially ending widespread use of these flexibilities at DOD, with limited exceptions as approved by the Secretary of Defense.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for GAO to review the status of DOD’s telework and remote work programs. This report (1) describes DOD policies since 2020; and assesses the extent to which DOD (2) collected data on civilian employee telework and remote work eligibility from December 2021 through February 2025 and used these programs in 2024, and (3) has evaluated the effects of using telework and remote work in meeting agency goals.

GAO reviewed federal and DOD telework and remote work policies; analyzed data on DOD employee telework and remote work eligibility and use; and interviewed officials from DOD and from 19 DOD components.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DOD (1) develop formal processes to ensure data on civilian employee eligibility for telework and remote work are accurate, timely, and complete; and (2) establish clear and specific requirements for evaluating the effects of telework and remote work in relation to the department’s goals. DOD concurred with both recommendations and outlined actions it plans to take towards their implementation.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ADA |

Americans with Disabilities Act |

|

DCPAS |

Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service |

|

DCPDS |

Defense Civilian Personnel Data System |

|

DCPS |

Defense Civilian Pay System |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

GS |

General Schedule |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

OSD |

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 8, 2026

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) use of telework and remote work has evolved significantly since the department issued policy implementing these flexibilities for eligible employees in 2010.[1] In early 2020, DOD accelerated its adoption of both telework and remote work to ensure continuity of operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the pandemic subsided, federal policy encouraged agencies, including DOD, to resume in-person work while still leveraging telework and remote work to better meet human capital needs and improve mission delivery.[2] More recently, in January 2025, the President issued a memorandum directing all agencies to require employees to work in-person at an agency office on a full-time basis.[3] In response, the Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum directing the return to in-person work for all DOD employees, with limited exceptions.[4]

We have previously reported on the use of telework and remote work by federal agencies, including DOD. Since 2003, we have identified key practices federal agencies should implement to help ensure successful telework programs, ranging from technology and training practices to program planning and evaluation.[5] In June 2025, we found that a lack of federal guidance hindered the ability of 24 selected federal agencies to evaluate the effects of remote work. We recommended that the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) issue guidance for agencies to assess benefits and costs when offering remote work positions, including the effects of remote work on the mission and outcomes of the agency, employee recruitment and retention, and operational costs.[6] OPM partially concurred with this recommendation and described plans to implement it.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for us to review the status of DOD’s telework and remote work programs.[7] This report (1) describes how DOD telework and remote work policies have changed since 2020; (2) assesses the extent to which DOD has collected data on civilian employee telework and remote work eligibility from December 2021 through February 2025, and used these programs in calendar year 2024; and (3) assesses the extent to which DOD has evaluated the effects of telework and remote work programs in meeting its agency goals.

To address our first objective, we reviewed federal and DOD telework and remote work policies issued since 2020. We also interviewed officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) to discuss these policies and determine related status of DOD’s efforts to address January 2025 return to in-person work requirements. To address our second objective, we analyzed DOD civilian personnel data to determine employee telework and remote work eligibility for 13 selected dates between December 2021 and February 2025. We also analyzed DOD civilian personnel time and attendance data to determine the extent of telework and remote work hours used for pay periods ending in 2024. We reviewed the data against DOD requirements for collecting telework and remote work eligibility and use data.[8] We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of determining total eligible positions and telework and remote hours worked for DOD employees. However, data were limited for determining the number of DOD employees eligible for telework or remote work, which we discuss further in this report.

To address our third objective, we met with OSD officials to discuss departmental efforts to evaluate telework and remote work prior to the January 2025 executive branch and DOD policy changes. We also identified 19 DOD component agencies with significant use of telework and remote work or responsibilities related to policy development and training. We reviewed documents and interviewed officials from these components to identify the extent to which they have evaluated the effects of telework and remote work in relation to OPM and DOD evaluation requirements.[9] We analyzed component documents and interviews to identify themes and perspectives. We characterize component perspectives using the following modifiers: “most” represents officials from 14 or more components, “more than half” represents 10 to 13 components, “several” represents officials from four to nine components, and “some” represents officials from one to three components. For more detailed information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Telework and Remote Work Authorities

The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 defines telework and establishes requirements for federal telework programs.[10] The Act defines telework as a work flexibility arrangement under which an employee performs the duties and responsibilities of such employee’s position and other authorized activities from an approved worksite other than the location from which the employee would otherwise work. It also requires each executive agency to establish and implement a policy under which employees are authorized to telework. The Act specifically identifies the following categories for reporting telework participation: 3 or more days per pay period; 1 or 2 days per pay period; once per month; and occasional, episodic, or short-term basis (i.e., situational telework such as ad-hoc or unscheduled telework). OPM’s 2021 guidance establishes additional guidance for agencies by defining two broad types of telework:

· routine telework, in which telework occurs as part of an ongoing, regular schedule; and

· situational telework, which is approved on a case-by-case basis and the hours are not worked as part of an approved, ongoing, or regular telework schedule.[11] OPM’s 2021 guidance also states that federal agencies have discretion to define types of arrangements and parameters for participation within their telework policies and telework agreements.

Remote work is another type of work flexibility arrangement that permits employees under a written remote work agreement to perform their work at an alternative worksite, such as their home. However, unlike telework, employees are not expected to report to an agency worksite on a regular and recurring basis.[12] Additionally, teleworkers receive the locality pay associated with the agency worksite to which they report when not teleworking; remote workers receive locality pay associated with their alternative worksite.[13]

The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 also requires OPM to annually report to Congress on the extent of telework participation and utilization across the federal government.[14] To meet this requirement, OPM collects, analyzes, and consolidates both telework and remote work data from executive agencies—including DOD—in the annual Status of Telework in the Federal Government Report to Congress. The Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service (DCPAS) is responsible for coordinating data collection across all DOD components for the annual submission to OPM. OPM’s most recent report to Congress, issued in December 2024, included data on the use of telework and remote work for fiscal year 2023.[15]

DOD Roles and Responsibilities for Telework and Remote Work

Various DOD officials and entities have responsibilities for the implementation and oversight of telework and remote work flexibilities (see table 1).

Table 1: Department of Defense (DOD) Officials and Entities Responsible for Telework and Remote Work Implementation and Oversight

|

DOD office |

Roles and responsibilities |

|

Secretary of Defense |

Establishes the department’s telework and remote work posture and permissions, including by authorizing telework and remote work exemptions for certain employees and individuals (e.g., spouses of service members, personnel with medical needs). |

|

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs |

Develops DOD civilian and military personnel telework and remote work policy. |

|

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Civilian Personnel Policy |

Designates the DOD Telework Managing Officer, assists with developing civilian personnel policy, and confers on telework policies with the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security and the DOD Chief Information Officer. |

|

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Personnel Policy |

Helps create military personnel policy and oversees its implementation, application, and execution by DOD components. |

|

Director, Department of Defense Human Resources Activity |

Supports the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Personnel Policy and the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Civilian Personnel Policy in executing their duties and responsibilities for DOD telework and remote work. The office also prepares DOD-wide employee reports on telework eligibility and participation rates and works with the telework managing officer to assess progress made towards DOD goals relating to telework and remote work. |

|

Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security |

Creates telework and remote work policies for information and operations security, foreign intelligence risks, and use of classified devices. |

|

DOD Chief Information Officer |

Provides guidance for information technology and data security and manages the assessment and approval of technologies for telework and remote work. |

|

DOD Telework Managing Officer |

Creates and implements policies for telework and remote work, advises the DOD Chief Human Capital Officer and DOD leadership, and assesses the compliance of DOD’s telework and remote work initiatives. |

|

Secretaries of the military departments, principal staff assistants of Office of the Secretary of Defense components, defense agencies, and DOD field activities |

Create, implement, oversee, operate, and evaluate telework and remote work programs according to the Telework Enhancement Act; assign telework and remote work implementation authority; and approve exemptions that meet DOD or Office of Personnel Management criteria. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD information. | GAO‑26‑107601

DOD Policies Have Evolved Since 2020 to Reflect Federal Guidance on the Use of Telework and Remote Work

Since 2020, DOD telework and remote work policies have evolved to reflect federal guidance directing agencies to expand and, more recently, to reduce the use of telework and remote work by federal employees. The DOD telework policy that was in place in January 2020 applied to both civilians and service members and encouraged use to the broadest extent possible by eligible employees on a routine or situational basis. During the COVID-19 pandemic, use of telework and remote work continued to expand until mid-2021, when federal guidance directed agencies to begin planning for the return of employees to the office while also allowing agencies to pilot the expansion of remote work where appropriate for certain positions and activities. In January 2025, a presidential memorandum directed federal agencies to take steps to terminate remote work agreements and require most employees to return to work in person on a full-time basis. DOD has taken steps to implement this requirement, and nearly all civilian employees had returned to full-time in-person work by June 2025.

Since 2020, DOD Policy Has Reflected the Federal Government’s Expansion and Reduction of Telework and Remote Work

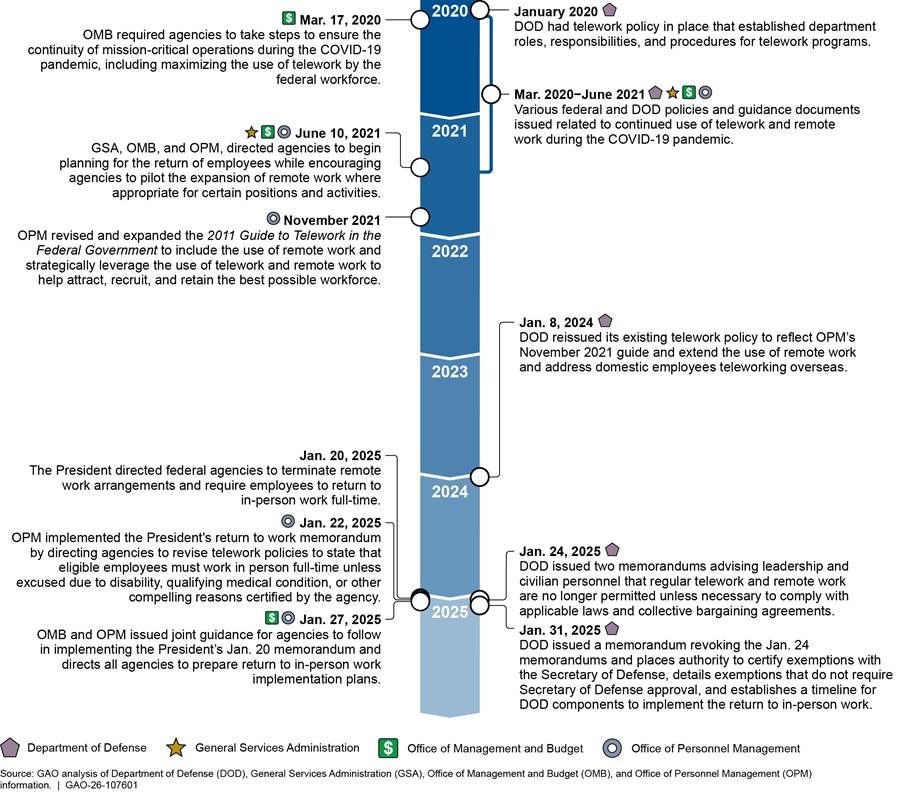

Since 2020, DOD telework and remote work policies have evolved to reflect changing federal guidance. Figure 1 shows a timeline of key federal and related DOD telework and remote work policies since 2020. Below the figure, we present key information on selected DOD and federal policies issued during this period.

· January 2020. The DOD telework policy that was in place in January 2020 outlined departmental roles, responsibilities, and procedures for telework programs.[16] This policy applied to both civilians and service members and stated that telework is a workplace flexibility—not a right or entitlement—and should be authorized for the maximum number of positions possible without diminished individual or organizational performance and used to the broadest extent possible by eligible employees on a routine or situational basis.

· March 2020. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued guidance requiring agencies to take steps to ensure the continuity of mission-critical operations during the COVID-19 pandemic, including maximizing the use of telework by the federal workforce.[17] The guidance called for telework to be optimized to preserve mission-critical workforce requirements and for federal agencies to promptly change their operations and services to reduce in-person interactions.

· March 2020−June 2021. OMB, OPM, and DOD issued a series of COVID-19 related guidance documents to support a maximum telework posture to maintain operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. These policies permitted eligible DOD employees to telework full-time or to the maximum extent possible.

· June 2021. OMB, OPM, and the General Services Administration (GSA) issued joint guidance directing agencies to begin planning for the return of employees to the office, while also allowing agencies to pilot the expansion of remote work where appropriate for certain positions and activities.[18] The guidance stated it intended to facilitate—not impede—the continuation of workforce flexibilities and required agencies to develop and submit to OMB a phased plan for employees to return to the office that included agency plans for continued use of telework and remote work.

· November 2021. OPM issued a revised version of its 2011 Guide to Telework in the Federal Government.[19] The revised guide addressed the continued evolution of telework following the COVID-19 pandemic, expanded existing guidance to address remote work, and encouraged agencies to strategically leverage these flexibilities to recruit and retain the best possible workforce. It also provided agencies resources—such as guidance on data collection and monitoring and labor relations considerations—to assist them in using these flexibilities to meet mission-critical needs while also balancing the demands of a changing workforce. The guide further emphasized the need for agencies to review and broaden telework eligibility, align data reporting procedures with OPM standards, and evaluate any cost savings related to telework initiatives.[20]

· January 2024. DOD canceled and reissued its 2012 telework policy, extending the policy to address use of remote work and domestic employees teleworking overseas.[21] The revised policy, which applied to both civilians and service members, reflected OPM’s 2021 Guide to Telework and Remote Work in the Federal Government and delineated department roles, responsibilities, and procedures for implementing telework and remote work programs. The policy stated that telework and remote work should occur to the broadest extent possible by eligible employees or service members. It also outlined goals for the use of telework and remote work, such as promoting workforce efficiency, emergency preparedness, maximum mission readiness, and quality of life; improving recruitment and retention; and reducing agency costs.

· January 20, 2025. The President issued a memorandum directing federal agencies to take steps to terminate remote work agreements and require employees to return to work in-person on a full-time basis, while allowing department and agency heads to make exemptions they deem necessary.[22]

· January 22, 2025. The Acting Director of OPM issued a memorandum implementing the President’s January 20, 2025, memorandum by directing agencies to revise telework policies to state that eligible employees must work full-time in-person unless excused due to disability, qualifying medical condition, or other compelling reasons certified by the agency head and employee supervisor.[23] The memorandum further recommended that agencies set a target date of approximately 30 days for full compliance with the presidential memorandum, subject to any exclusions granted by the agency and any collective bargaining obligations, and to advise OPM of the date that the agency would be in full compliance with the new telework policy.

· January 24, 2025. The Acting Secretary of Defense issued two memorandums advising DOD leadership and civilian personnel that, effective immediately, routine telework and remote work arrangements were not permitted unless necessary to comply with applicable laws and collective bargaining agreements that were in effect on January 22, 2025.[24] This guidance gave the secretaries of the military departments and principal staff assistants of Office of the Secretary of Defense components, defense agencies, and DOD field activities the authority to certify compelling reasons for permitting regular telework and remote work arrangements. According to the guidance, certification is not required for employee disability or qualifying medical conditions handled through the reasonable accommodation process. Situational telework may be authorized for weather-related emergencies, office closures, and other situations where telework serves a compelling agency need.[25]

· January 27, 2025. OMB and OPM issued joint guidance directing all agencies to prepare plans to implement the presidential memorandum by February 7, 2025.[26] Implementation plans were to include timelines and major milestones for implementation, steps the agency would take to determine permanent worksites for employees currently teleworking full-time, and plans for moving those employees to those sites. The plans were also to include risks, barriers, or resource constraints that would prevent the expeditious return of all eligible employees to in-person work (e.g., availability of suitable office space); a plan to overcome those barriers; and the agency’s criteria for determining “other compelling reasons” for exemptions from return-to-office where categorical or indefinite exemptions may be granted.

· January 31, 2025. The Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum stating that with limited exceptions, exemptions to permit routine telework and remote work are to be approved by the Secretary of Defense.[27] The memorandum also outlined exceptions to this policy by specifying exemptions that do not require Secretary of Defense approval. These include exemptions for employees with an approved deferred resignation request, employees for whom telework or remote work is a reasonable accommodation pursuant to applicable law, or employees who are approved for remote work to accompany their service member spouse to an assignment not in the vicinity of their worksite.[28] According to the memorandum, the Secretary also does not need to approve exemptions for employees when the DOD component head has determined there is not suitable office space, and for whom applicable law and collective bargaining obligations require an exemption. The Secretary’s memorandum established a timeline for different types of DOD employees to return to in-person work. Specifically, senior executives and highly qualified experts were to return within 7 days; senior professionals, GS-15, and their equivalents were to return within 21 days; and all other non-exempt employees were to return as soon as possible, and not later than 4 months from the date of the memorandum.[29]

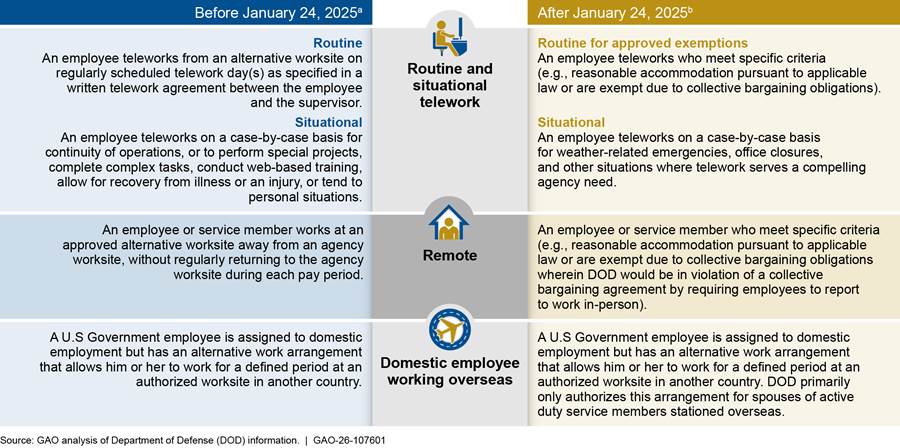

Figure 2 provides a comparison of the types of telework and remote work arrangements available to DOD employees before and after January 2025.

aDOD Instruction 1035.01, Telework and Remote Work Policy (Jan. 8, 2024).

bOn January 24, 2025, the Acting Secretary of Defense issued guidance prohibiting the use of routine telework and remote work arrangements in compliance with the January 20, 2025 presidential memorandum, “Return to In-Person Work.” Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Implementation of Presidential Memorandum, “Return to In-Person Work,” (Jan. 24, 2025).

DOD Has Taken Steps to Implement Return to In-Person Work

According to officials, DOD submitted its return to office implementation plan to OPM in February 2025. The plan stated that DOD was updating its telework policy in accordance with the President’s and the Secretary’s January memorandums, and that it planned to be in full compliance with these memorandums by June 2, 2025. The plan identified approximately 20,000 civilian employees that had been authorized to work remotely outside of their local commuting area and provided cost estimates for relocating these employees to official duty locations. The plan also identified risks, barriers, and resource constraints that may affect DOD’s ability to implement the presidential memorandum. For example, the plan stated that the return to in-person work may pose risks to DOD’s recruitment and retention efforts as well as military and family readiness. It also stated that a lack of facilities and infrastructure, along with cost and resource implications, may affect implementation.

The plan also included a final implementation date of June 2, 2025 for employees to return full-time to in-person work. DOD officials told us that as of July 31, 2025, approximately 8 percent of DOD civilian employees (62,000 out of 780,000) had not returned to full-time in-person work.[30] Of those, about 6 percent of civilian employees (45,000 of 780,000) had not returned due to deferred resignation, military spouse exemption, domestic employee teleworking overseas status, or a temporary exemption due to office space limitations. About 2 percent (17,000 of 780,000) had not returned due to reasonable accommodations.

DOD Did Not Collect Complete Data on Civilian Telework and Remote Work Eligibility, but GAO’s Analysis Shows Most Employees’ Work Was Performed in Person in 2024

From December 2021 through February 2025, DOD data showed that between 65 and 68 percent of its civilian employee positions were classified as eligible for telework or remote work. However, data on employee eligibility for telework and remote work during this period were incomplete.[31] About 81 percent of DOD civilians’ work was performed in-person in calendar year 2024, with telework and remote work usage varying across DOD components and occupations, according to our analysis of employee time and attendance data.

Most DOD Civilian Positions Were Eligible for Telework or Remote Work Between December 2021 and February 2025, but Employee Eligibility Data Are Incomplete

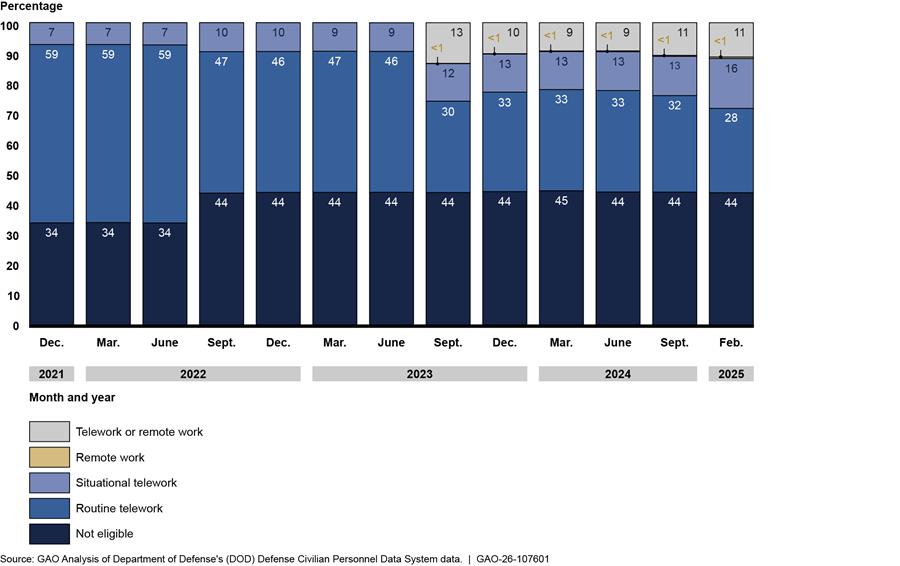

From December 2021 through February 2025, DOD data showed that between 65 and 68 percent of its civilian positions were designated as eligible for telework or remote work. However, data on actual employee eligibility for telework and remote work during this period are incomplete. DOD civilian employee personnel records are captured in the Defense Civilian Personnel Data System (DCPDS).[32] We examined data in DCPDS for 13 selected dates during the period from December 2021 through February 2025. Within DCPDS, eligible position data reflect that the DOD component has determined that the duties of the position can be performed under a telework or remote work arrangement; eligible employee data reflect the type of telework or remote work arrangement for which the employee has been approved, if any.

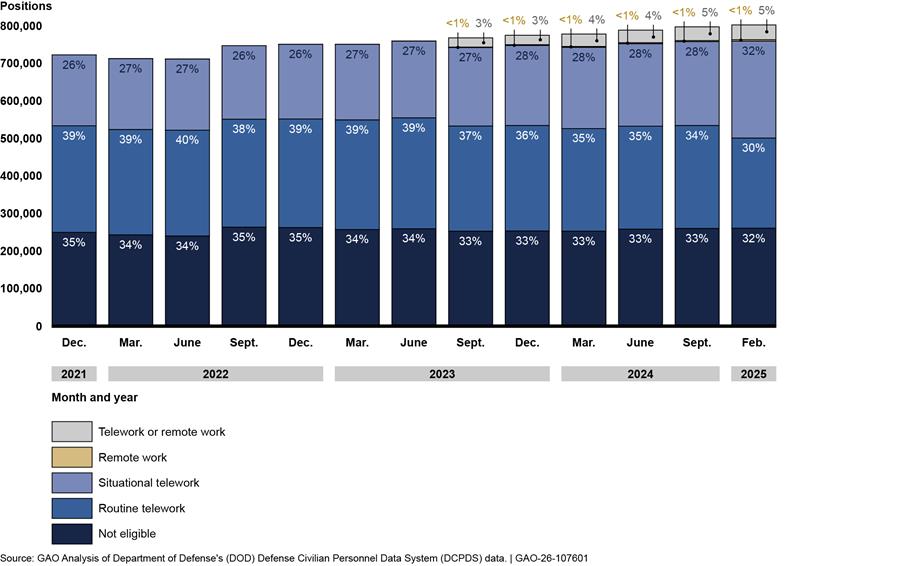

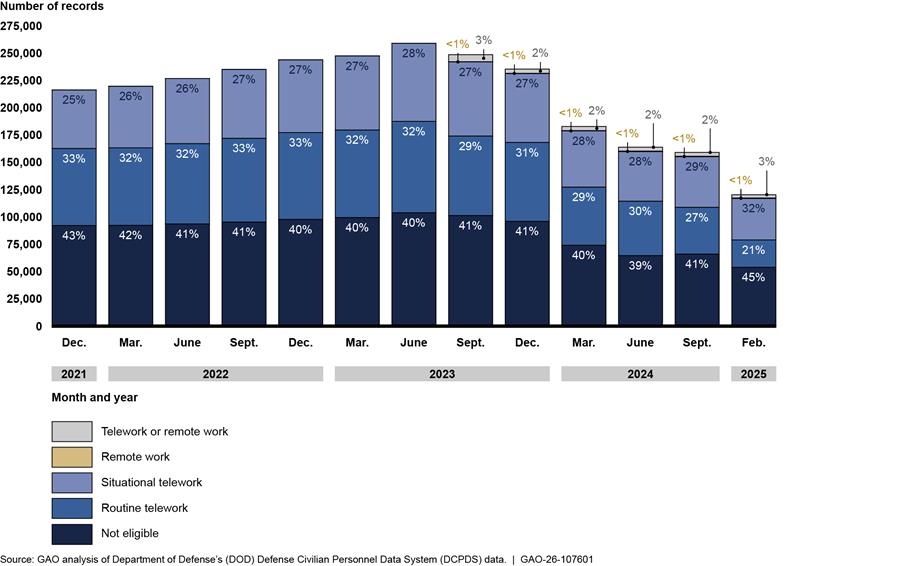

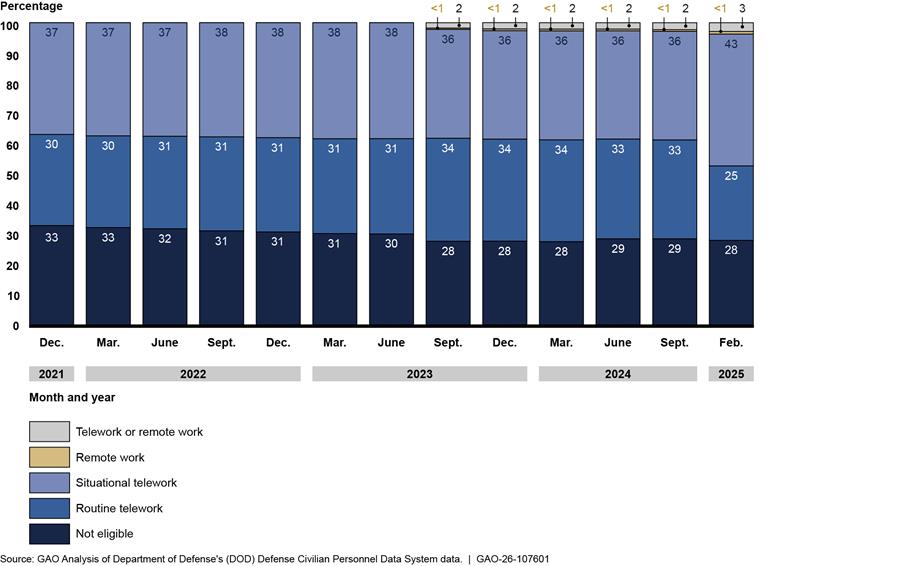

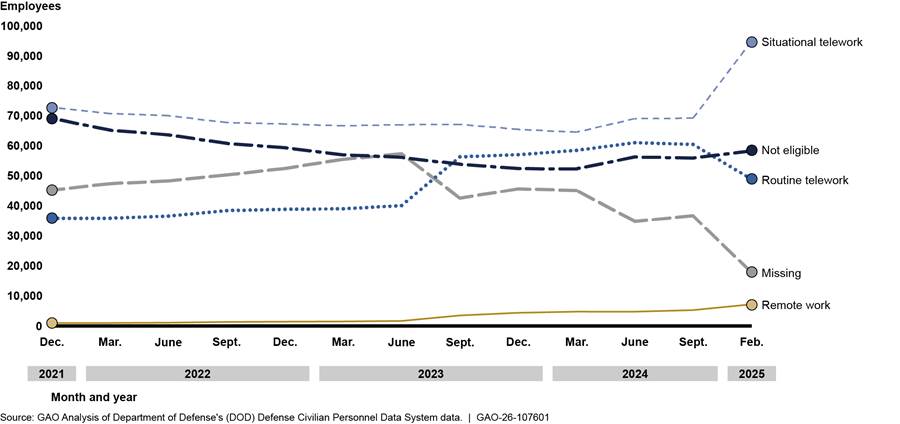

For the 13 selected dates from December 2021 through February 2025, we found that, on average, 276,651 (37 percent) of civilian employee positions in DCPDS were coded as eligible for routine telework, and another 206,169 (27 percent) positions were coded as eligible for situational telework.[33] Additionally, on average, for selected dates from September 2023 to February 2025, we found that 2,367 (0.3 percent) of positions were coded as eligible for remote work only, and 31,842 (4 percent) were positions coded as eligible for either telework or remote work.[34] Prior to September 2023, DOD was not required to track data for remote positions and generally had less than 100 positions designated with these codes.[35] Figure 3 shows positions by eligibility type for selected dates between December 2021 and February 2025.

Figure 3: DOD Civilian Positions by Type of Telework and Remote Work Eligibility for Selected Dates, December 2021 Through February 2025

Note: Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an agency worksite and enter into an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official worksite is an approved alternative workspace.

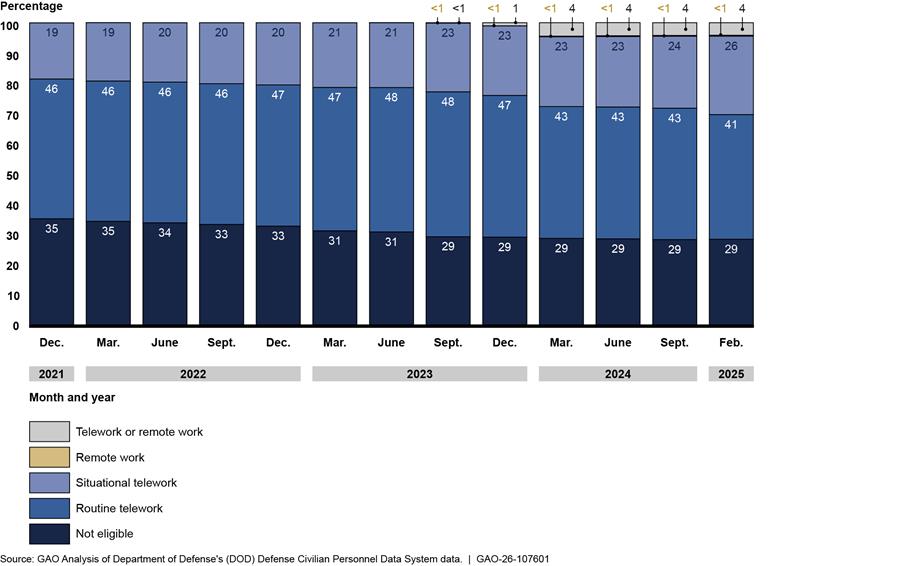

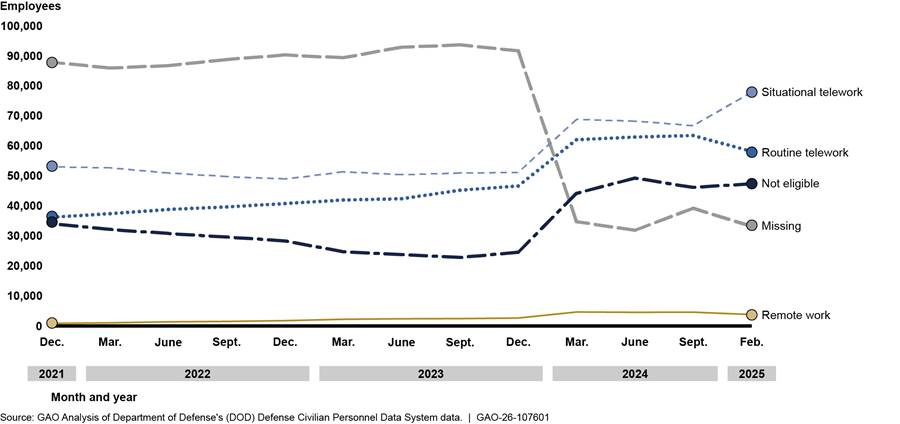

While data for position eligibility in DCPDS from December 2021 through February 2025 were generally complete for the dates we analyzed, we found that data for the individual employee eligibility were incomplete. Specifically, 15 percent of the records we reviewed from February 2025 were missing employee eligibility data. As a result, the number of DOD civilian employees in DCPDS that were eligible for telework or remote work during this time is unknown.

We found that the missing employee eligibility data varied by the type of position eligibility. For example, in February 2025, employee eligibility data were missing for 24,863 (about 21 percent) of the positions eligible for routine telework; 37,548 (about 32 percent) of the positions eligible for situational telework; 335 (about 0.3 percent) of the positions eligible for remote work; and 3,044 (about 3 percent) of the positions eligible for either telework or remote work. Figure 4 shows the number and percentage of missing employee eligibility data, by position eligibility type, for selected dates since December 2021.

Figure 4: DOD Records with Missing Telework and Remote Work Civilian Employee Eligibility Data by Position Eligibility Type for Selected Dates, December 2021 Through February 2025

Note: Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an agency worksite and enter into an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official worksite is an approved alternative workspace.

With missing data on employee eligibility, it is likely DOD publicly reported data on DOD civilian telework and remote work inaccurately. For example, OMB reported DOD data indicating that in May 2024, DOD had 61,549 remote employees.[36] By contrast, DOD told us that in June 2024, a month later, the department had 35,558 remote employees.[37] Furthermore, through our review of the data and conversations with DOD officials, we found that the 35,558 employees are based on positions coded as “eligible for remote work only” and “eligible for telework and remote work,” and not eligible employees. Of the 35,558 remote employees, we found about 10,000 employees in these positions were designated as eligible for remote work. Of the remainder, DOD designated about 21,000 employees as being eligible for regular or situational telework, but it was missing eligibility data for about 4,000 employees. For additional information on position and employee telework and remote work eligibility, see appendix II.

OPM and DOD policy require the collection of data about which civilian positions and which civilian employees are eligible for telework and remote work. Specifically, OPM policy issued in March 2023 specified the type of telework and remote work eligibility data agencies are required to collect, such as the number of positions and personnel eligible for telework.[38] Subsequently, in July 2023, DOD issued guidance implementing the OPM policy and notified DOD component human resource offices that DCPDS had been updated to support the OPM policy. DOD also directed components to ensure that new and existing telework and remote work eligibility codes were appropriately assigned to each of their employees.[39] Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, including relevant timely data from reliable sources that are reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represent what they purport to represent.[40] Furthermore, our best practices for assessing the reliability of data include documentation of data entry and processing policies that can be helpful to agencies.[41]

The July 2023 DOD guidance noted that OPM expected that all agencies would implement these updates by September 1, 2023. In July 2024, a DOD official told us they anticipated that updated designations for all personnel would be complete by the end of 2024. While there was a decline in missing data that coincides with changes to policy—and more recently, due to DOD’s efforts to revise employee eligibility for telework and remote work—DCPAS officials told us there is no formal process in place to ensure eligibility data are accurate, timely, or complete. Officials told us the procedures for maintaining eligibility data are decentralized and the responsibility for maintaining these data is generally managed by local human resource officials or supervisors and is usually conducted when an employee experiences a formal personnel change. Given that the steps required in reviewing and updating employee records is time consuming, and due to resource constraints and competing priorities, it can be challenging to ensure that these data are accurate, timely, and complete.

Without formal processes to help ensure accurate, timely, and complete data on employee eligibility for telework and remote work, DOD will continue to lack visibility into how many employees are approved for these arrangements under its new telework and remote work posture. Moreover, in the absence of such formal processes, DOD may not be able to ensure that employees are using these programs in compliance with both current and future DOD policy governing telework use and eligibility, and it cannot ensure that data reported to OPM are accurate and complete.

In 2024, Most Work by DOD Civilian Employees Was Performed In-Person, but Telework and Remote Work Usage Varied Across DOD Components and Occupations

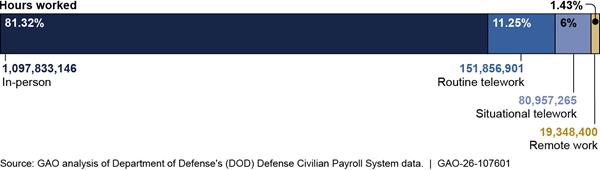

Our analysis of DOD civilian personnel time and attendance data for 2024 shows that most work performed by DOD civilian employees was recorded as conducted in-person.[42] Specifically, DOD civilians reported working about 1.1 billion hours (81 percent) in-office out of 1.3 billion total hours.[43] Figure 5 shows the percentage of DOD civilian employee hours recorded by work arrangement in calendar year 2024.

Figure 5: Percentage of DOD Civilian Employee Hours Recorded by Work Arrangement for Pay Periods Ending in Calendar Year 2024

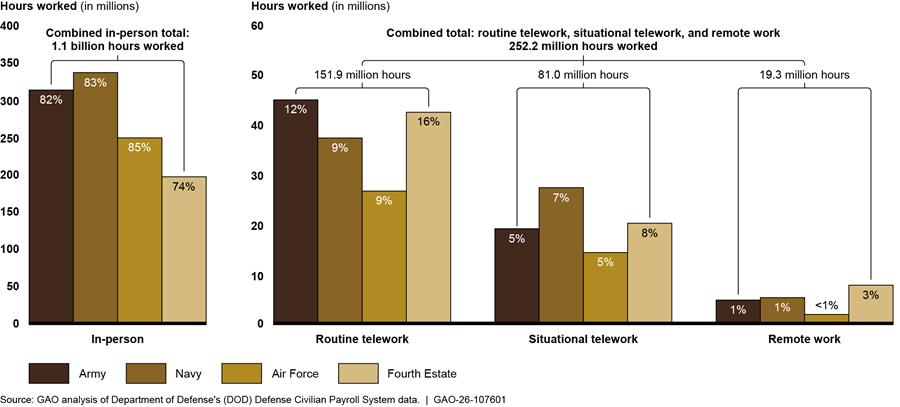

We also found that employees’ use of telework and remote work in 2024 varied among four major DOD components: the Departments of the Army, Air Force, and Navy—and the DOD agencies and offices collectively referred to as “DOD’s Fourth Estate.”[44] See figure 6 for civilian work hours by type of work and DOD component.

Figure 6: Civilian Work Hours by Type of Work and DOD Component for Pay Periods Ending in Calendar Year 2024

Note: Percentages shown represent percent of each DOD component’s total work hours for pay periods ending in calendar year 2024.

We found that DOD civilians’ use of telework and remote work was concentrated in a small number of civilian occupations, with the most significant use by employees in mission critical occupations (see table 2).[45] Specifically, for the three pay periods in 2024 we analyzed, 73 percent of all telework hours reported were performed by personnel in 20 of the 585 DOD occupations reported. Of these 20 occupations, DOD has designated 13 as mission critical, including two that are also identified by OPM as government wide high-risk occupations—contracting and human resources management.[46]

Table 2: DOD Civilian Employee Telework Hours for Three Selected 2024 Pay Periods, by Occupation and as a Percentage of All DOD Telework Hours

|

Occupational seriesa |

Total telework hours |

Percent of all DOD telework hours |

|

Contracting (1102)b |

3,117,850 |

11.06 |

|

Information Technology Management (2210) |

2,515,322 |

8.92 |

|

Management and Program Analyst (0343) |

2,238,006 |

7.94 |

|

Financial Administration and Program (0501) |

1,460,370 |

5.18 |

|

Logistics Management (0346) |

1,420,827 |

5.04 |

|

Miscellaneous Administration and Program Series (0301) |

1,388,190 |

4.93 |

|

General Engineering (0801) |

1,081,556 |

3.84 |

|

Human Resources Management (0201)b |

942,666 |

3.34 |

|

Auditing (0511) |

749,864 |

2.66 |

|

General Business and Industry (1101) |

708,795 |

2.51 |

|

Electronics Engineering (0855) |

642,938 |

2.28 |

|

Mechanical Engineering (0830) |

596,819 |

2.12 |

|

Computer Science (1550) |

576,100 |

2.04 |

|

Accounting (0510) |

574,939 |

2.04 |

|

Security Administration (0080) |

481,473 |

1.71 |

|

Budget Analysis (0560) |

454,815 |

1.61 |

|

Program Management (0340) |

446,727 |

1.58 |

|

Quality Assurance (1910) |

417,946 |

1.48 |

|

Accounting Technician (0525) |

396,049 |

1.41 |

|

Inventory Management (2010) |

394,626 |

1.40 |

|

All Other Occupations |

7,579,155 |

26.89 |

|

Total telework hours reported |

28,185,035 |

100.00 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense’s (DOD) Defense Civilian Payroll System for pay periods ending March 23, June 15, and September 21, 2024. I GAO‑26‑107601

Note: Excludes hours from employees with multiple occupational series per pay period (about 0.7 percent of total telework hours) because the data did not allow us to distinguish which hours were worked for which position.

aOccupations in bold indicate DOD mission critical occupations. DOD defines mission critical occupations as those “having the potential to put a strategic program or goal at risk of failure related to human capital deficiencies.”

bOffice of Personnel Management (OPM) government-wide high-risk occupation, based on OPM’s risk-based model for identifying government-wide occupations with mission-critical skills gaps.

Similarly, for the same three selected pay periods, 86 percent of all remote work hours were performed by personnel in 20 occupations, nine of which DOD identified as mission critical occupations, according to our analysis (see table 3). About a third of all remote work in 2024 was performed by employees in contracting and human resources management high-risk occupations.

Table 3: DOD Civilian Employee Remote Work Hours for Three Selected 2024 Pay Periods, by Occupation and as a Percentage of all DOD Remote Work Hours

|

Occupational seriesa |

Total remote work hours |

Percent of all DOD remote work hours |

|

Human Resources Management (0201)b |

417,472 |

18.65 |

|

Contracting (1102)b |

300,442 |

13.42 |

|

Management and Program Analyst (0343) |

208,177 |

9.30 |

|

Information Technology Management (2210) |

192,774 |

8.61 |

|

General Investigation (1810) |

185,237 |

8.28 |

|

Financial Administration and Program (0501) |

157,693 |

7.05 |

|

Miscellaneous Administration and Program (0301) |

79,459 |

3.55 |

|

Accounting (0510) |

61,566 |

2.75 |

|

Human Resources Assistance (0203) |

46,427 |

2.07 |

|

Budget Analysis (0560) |

44,216 |

1.98 |

|

General Business and Industry (1101) |

33,809 |

1.51 |

|

Logistics Management (0346) |

29,960 |

1.34 |

|

Operations Research (1515) |

28,537 |

1.28 |

|

Program Management (0340) |

26,332 |

1.18 |

|

General Engineering (0801) |

26,090 |

1.17 |

|

Computer Science (1550) |

25,760 |

1.15 |

|

Accounting Technician (0525) |

23,778 |

1.06 |

|

General Attorney (0905) |

20,028 |

0.89 |

|

Electronics Engineering (0855) |

14,545 |

0.65 |

|

General Inspection, Investigation, Enforcement, and Compliance (1801) |

12,898 |

0.58 |

|

All other occupations |

302,876 |

13.53 |

|

Total remote work hours reported |

2,238,073 |

100.00 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense’s (DOD) Defense Civilian Payroll System for pay periods ending March 23, June 15, and September 21, 2024. I GAO‑26‑107601

Note: Excludes hours from employees with multiple occupational series per pay period (about 0.6 percent of total remote work hours) because the data did not allow us to distinguish which hours were worked for which position.

aOccupations in bold indicate DOD mission critical occupations. DOD defines mission critical occupations as those “having the potential to put a strategic program or goal at risk of failure related to human capital deficiencies.”

bOffice of Personnel Management (OPM) government-wide high-risk occupation, based on OPM’s risk-based model to identify government-wide occupations with mission-critical skills gaps.

For additional information on DOD civilian employees’ use of telework and remote work, see appendix II.

DOD Has Not Formally Evaluated the Effects of Telework and Remote Work Programs, but Selected Components Reported Perceived Benefits and Challenges

DOD has not formally evaluated the effects of telework and remote work in relation to its agency goals. However, selected DOD components reported informally evaluating limited aspects of telework and remote work programs, along with perceived benefits and challenges related to the use of telework and remote work. DOD has used telework and remote work, in part, to support various agency goals related to mission productivity and efficiency, workforce management, and operational costs. For example, DOD’s telework and remote work policy prior to January 2025 encouraged the use of telework and remote work flexibilities to support recruiting and retaining employees, reducing business costs, and increasing work-life balance.[47] Since January 2025, DOD’s policy focuses on implementing the goals of the presidential memorandum and maximizing in-person camaraderie and collaboration, promoting the use of telework only when necessary to support agency needs and mission execution.[48]

DOD officials told us they have not conducted formal evaluations of their employees’ use of telework and remote work in relation to prior or current agency goals. However, most component officials reported having informally evaluated limited aspects of telework and remote work, such as perceptions of the impact of telework on productivity and retention. For example, a 2021 Navy leadership survey gathered information about the effects of telework on mission productivity. Separately, Air Force civilian surveys from 2022 through 2024 included questions on the influence of telework and remote work on employees’ decisions to remain in their positions.[49] Officials from all three military departments also said they used results from the OPM Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, which included similar questions, as a metric to assess the effects of telework and remote work.[50]

Telework program managers, labor and employee relations staff, and other human capital officials from the 19 military department and Fourth Estate components we met with also reported perceived benefits and challenges associated with the use of telework and remote work in the areas of (1) mission productivity and efficiency, (2) workforce management, and (3) operational costs.[51] We met with these officials prior to the full implementation of the return to in-person work presidential memorandum; therefore, their perspectives do not reflect challenges and benefits associated with employees’ return to full-time, in-person work.

Mission productivity and efficiency. Officials from all 19 components told us their use of telework and remote work maintained, and in some cases improved, mission productivity and efficiency. For example, officials from several components stated that telework and remote work increased their ability to service clients and partners around the world by expanding available communication and collaboration tools and extending personnel availability outside of normal facility operating hours.[52] Officials from several components also told us telework and remote work increased the time personnel spent working by reducing their use of full day leave and providing them flexibility to work partial days from home when they had personal obligations during the workday or situational disruptions like inclement weather or facility repairs. For example, officials from one component told us that in 2020, Hurricane Sally reduced their physical footprint to such an extent that they were only able to continue operations because of the ability to telework.

Officials from most of the components we met with also told us that telework and remote work expanded access to training, with some reporting increased attendance and improved employee development. For example, officials from one component said that the fill rate for virtual courses was 76 percent, whereas the in-person training fill rate was 59 percent. Similarly, officials from another component told us the availability of virtual training contributed to higher rates of training completion.

Conversely, officials cited challenges of telework and remote work related to mission productivity and efficiency. For example, officials from some components stated that telework reduced opportunities for informal collaboration and information sharing. Additionally, an official from one component reported increased difficulty reaching teleworking employees compared to those working onsite, while officials from another component said some teleworking employees were unreachable or were clearly away from their assigned duty station during calls. Officials from another component said the expansion of telework required additional training and resources on how to lead and work in a virtual environment, avoid burnout, and maintain interpersonal skills.

Workforce management. Officials from most components we reviewed told us they used telework and remote work to support workforce management efforts, such as recruitment and retention. For example, officials from some components told us that retirement eligible employees stayed longer than planned due to the option to telework or work remotely. Similarly, officials from one component reported that telework and remote work contributed to increased staffing levels, decreased turnover, and a reduced need to re-announce open positions. Officials from another component told us telework and remote work allowed them to fill mission critical IT personnel contracting jobs located in less desirable geographic areas or areas with limited talent pools. Similarly, officials from one component said they received 1,000 applicants for a hard-to-fill position after re-categorizing it as a remote position due to initially receiving only 30 local applicants, all of whom were unqualified. Likewise, officials from one OSD office told us they were able to maintain 27 mission critical positions by offering remote work and telework.

In contrast, officials from some components reported workforce management challenges stemming from the use of telework and remote work. These included decreased morale and retention of employees ineligible for telework—such as those conducting classified work or occupations requiring onsite availability. As a result, officials from more than half of the components told us they lost personnel to organizations offering more telework or remote work flexibilities. For example, one official said their component saw an increase in attrition rates, particularly in hard-to-fill positions like IT, when employees began to return to their worksites at the conclusion of the pandemic.

Operational costs. Officials from most components told us they believe the use of telework and remote work affects operational costs, although they did not provide us with specific cost data. For example, officials cited examples of cost savings related to the reductions in office space; reduced travel costs associated with in-person training; and the ability to hire remote personnel in areas with lower locality pay rates than the rates in the components’ physical locations. Additionally, officials from one component said use of telework and remote work decreased costs by promoting process efficiencies through technological advancements and reducing transit and commuter program subsidies.

However, officials told us there may also be costs associated with telework and remote work, such as higher locality pay rates for remote workers, travel costs for remote employees to conduct work at components’ physical locations, and shipping costs to send remote employees equipment. For example, officials from one component said they hired a remote employee in a city with locality pay rate $10,000 higher than the component’s local pay rate. Additionally, an OSD official said an increase in use of telework and remote work by DOD civilians can increase defense contractor costs to provide full time support for on-site needs previously performed by those DOD civilians, such as managing facility and classified space access.

The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 states that OPM shall assist federal agencies in establishing appropriate qualitative and quantitative evaluation measures and teleworking goals,[53] and OPM guidance states that agencies should evaluate the effects of telework for both the individual teleworker and the agency in general.[54] Similarly, our key practices for telework state that policies should establish measurable program goals and develop and use evaluation tools from the inception of telework programs to identify and address problems or issues.[55] It is DOD’s policy that as part of its strategic human capital planning, the department analyzes and monitors the strategic environment, workforce trends, staffing and competency assessments, and gap analyses to verify that recruitment, retention, and development initiatives address current and future mission requirements.[56] DOD’s 2024 telework and remote work policy requires an annual evaluation of progress toward telework and remote work goals, such as goals related to emergency preparedness, recruitment, retention, and program participation.

Some component officials told us it is difficult to isolate use of telework and remote work—in both expanded and limited capacities—from other factors when assessing their effect on agency goals, while others stated they consider the requirement to evaluate these programs to be met through DOD’s annual data submission to OPM for the Status of Telework in the Federal Government report to Congress. However, although DOD’s annual data submissions include anecdotal information on the perceived effects of telework and remote work, they do not reflect the formal evaluation of the use of these arrangements in relation to agency goals.

DOD officials told us they agreed with the need to evaluate the future effects of telework and remote work programs and are updating the department’s telework and remote work policy, but added they were unsure whether the revised policy will establish requirements for evaluating how telework and remote work programs affect agency goals.[57] Without clear and specific requirements for the formal evaluation of telework and remote work programs, DOD cannot determine if these programs are helping it meet agency goals, such as goals related to recruitment and retention.[58]

Conclusions

DOD’s use of telework and remote work has evolved significantly since the department first issued policy implementing these flexibilities over a decade ago. This evolution began with promoting the use of telework and remote work to meet agency goals through widespread implementation of flexibilities in response to the pandemic, and later extended to reducing use of these flexibilities to meet executive branch requirements. Regardless of the goals or requirements DOD aims to achieve, data on how these flexibilities are being used and the effects of their use are key to determining if they are meeting their intended objectives.

DOD has collected some data on telework and remote work position eligibility and use but does not have formal processes to ensure accurate, timely, and complete data on employee eligibility. Without such processes, DOD has a limited understanding of how many employees are approved for these arrangements and cannot be assured that its use of these flexibilities complies with its policy.

Additionally, in the absence of clear and specific requirements for formally evaluating telework and remote work programs, DOD cannot determine the extent to which these programs are helping to meet established agency goals.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness requires DOD components to develop formal processes to ensure data on civilian employee eligibility for telework and remote work are accurate, timely, and complete. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, in revising DOD’s telework and remote work guidance, establishes clear and specific requirements for evaluating the effects of telework and remote work programs in relation to the department’s goals. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment., DOD provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix III. DOD agreed with our recommendations and outlined actions it plans to take for their implementation.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretary of Defense; the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness; the Secretaries of the Army, Air Force, and Navy; and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at CzyzA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Alissa H. Czyz

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chair

The Honorable Christopher Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report (1) describes how Department of Defense (DOD) telework and remote work policies have changed since 2020, (2) assesses the extent to which DOD collected data on civilian employee telework and remote work eligibility from December 2021 through February 2025, and used these programs in calendar year 2024, and (3) assesses the extent to which DOD has evaluated the effects of using telework and remote work in meeting its agency goals.

Review of DOD Telework and Remote Work Polices Since 2020

To describe how DOD telework and remote work policies have changed since 2020, we reviewed relevant federal policies from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) implementing telework and remote work since 2020. We also reviewed DOD telework and remote work policies and guidance issued during this time, including policies related to the expansion and reduction of telework and remote work issued during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. To describe the status of DOD’s implementation of the January 20, 2025, we reviewed the “Return to In-Person Work” presidential memorandum.

We also reviewed OPM, OMB, and DOD guidance implementing the memorandum. Additionally, we interviewed officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, and the Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service (DCPAS) to discuss how telework and remote work policies have changed since 2020 and what steps DOD has taken to implement the “Return to In-Person Work” presidential memorandum.

Analysis of DOD Data on Employee Telework and Remote Work Eligibility

To assess the extent to which DOD collected data on civilian employee telework and remote work eligibility from December 2021 through February 2025, we analyzed civilian position and employee eligibility data. Specifically, we reviewed data for all DOD civilian employees included in the Defense Civilian Personnel Data System (DCPDS) for 13 selected dates from December 2021 through February 2025.[59] Dates were selected to reflect DOD’s use of telework and remote work following the issuance of the June 2021 federal post-pandemic re-entry guidance, but prior to the implementation of the January 2025 return to in-person work requirement. We selected data for pay periods 7, 13, 20, and 26. These 12 dates represented the last full pay period before the end of each fiscal quarter from the first quarter of fiscal year 2022 through the last quarter of fiscal year 2024. We also requested data for the end of February 2025 to capture eligibility before the June 2, 2025 implementation deadline for return to in-person work. The data included employee identifier, major component, subcomponent, position eligibility for telework or remote work, and the employee’s eligibility for telework or remote work, among other data elements.

The data in DCPDS represents DOD appropriated fund, non-appropriated fund, and local national civilians. This included data for about 751,000 DOD civilians on average, per pay period, for the dates in the scope of our review. Civilians from certain intelligence agencies are not included in DCPDS data.

We evaluated the documentation and data we collected against DOD and OPM data collection requirements, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, and our best practices for assessing the reliability of data.[60] Specifically we assessed the data against internal control standards related to use of quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, including use of relevant timely data from reliable sources that are reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represent what they purport to represent.

To assess the reliability of the DCPDS data, we reviewed documentation associated with its collection, structure, and data elements and conducted electronic testing of the data for missing values, obvious errors, and outliers. We also interviewed DCPAS officials who were knowledgeable about the management and uses of the data. We found that an individual employee may have more than one position recorded in DCPDS; however, we determined these records—ranging from 11 records in March 2022, to 109 records in February 2025—would not materially affect our analyses. We determined these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting the extent to which DOD has collected data on civilian personnel position and employee eligibility for the dates in the scope of our review. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of determining total eligible positions of DOD employees. However, data were limited for determining the number of DOD employees eligible for telework or remote work.

Analysis of DOD Data on Use of Telework and Remote Work

To assess the DOD civilian use of telework, we collected Defense Civilian Payroll System (DCPS) time and attendance data for all pay periods ending in calendar year 2024—from January 13, 2024, through December 28, 2024—the most recent, complete calendar year at the time of our review.[61] Data we collected represents approximately 850,000 employees throughout calendar year 2024.

We analyzed DCPS information for hours worked; we did not analyze information on use of leave, holiday hours, or other non-work hours. Time and attendance data, including whether work was conducted during telework or remote work, are self-reported by employees and validated by supervisors. For hours where use of telework or remote work was not reported, we considered these hours as in-person. Using these data, we determined the total number hours worked for pay periods ending in calendar year 2024, and the number of hours worked remotely or through telework.

To determine the DOD civilian use of telework by occupation, we analyzed occupational series codes in DCPS time and attendance records for three selected pay periods ending March 23, 2024; June 15, 2024; and September 21, 2024. We selected these three pay periods because they coincided with the three 2024 pay period end dates of DCPDS data we collected and reflect DOD’s use telework and remote work prior to the implementation of the return to in-person work Presidential Memorandum. As a result, data we present represents use of telework and remote work by occupation for these selected dates only and is not generalizable to use of telework and remote work by occupation for other time periods. Using these data, we calculated the total number of hours worked by telework and remote work type for each occupation across these three pay periods.

To assess the reliability of the DCPS data, we reviewed documentation associated with its collection, structure, and data elements and conducted electronic testing of the data for missing values, obvious errors and outliers. We also interviewed Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) officials who were knowledgeable about the management and uses of the data. We determined these data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our review.

Analysis of DOD’s Evaluation of Employee Use of Telework and Remote Work

To assess the extent to which DOD has evaluated its use of telework and remote work in relation to its agency goals, we reviewed documents and conducted interviews with DOD officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) and a nongeneralizable selection of 14 military department components and five Fourth Estate components. Component officials included telework program managers, labor and employee relations staff, and other human capital officials. We discussed component officials’ perceptions of benefits and challenges associated with telework and remote work. We met with these officials prior to the full implementation of the return to in-person work presidential memorandum; therefore, their perspectives do not reflect challenges and benefits associated with employees’ return to full-time, in-person work.

To select a sample of components from the Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, we reviewed data on the number of employees by each military department component that teleworked or worked remotely as of June 30, 2024. Using these data, we included the two components from each military department with the largest proportion of telework and the two with a significant number of remote work employees. In addition, to address DOD’s efforts to evaluate use of telework and remote work we also included headquarters organizations for each of the five military services in our selection (if they had not already been identified). Finally, to address the effect of telework and remote work on training and staff development, we included components responsible for training and education in our selection. This resulted in the identification of 14 military department components.

· Department of the Army. U.S Army Corps of Engineers; U.S. Army Futures Command; U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command; U.S. Army Civilian Human Resources Agency; and Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command.

· Department of the Navy. Naval Sea Systems Command; Headquarters United States Marine Corps; Naval Information Warfare Systems Command; Secretary of the Navy; and Naval Education and Training Command.

· Department of the Air Force. Air Force Materiel Command; Air Force Education & Training Command; Headquarters Air Force; and the Office of Chief of Space Operations.

To select a nongeneralizable sample of components from the Fourth Estate, we reviewed Defense Civilian Personnel Data System data on personnel telework and remote work eligibility as of September 2024. Using these data, we identified Fourth Estate components with 1,000 or more telework eligible personnel and selected the (1) top three components with the highest proportion of personnel approved for routine telework and (2) top three components with the highest proportion of personnel approved for remote work—two of which were the same. To address the use of telework and remote work among intelligence organizations, we also included a defense intelligence agency identified by DCPAS officials as an organization familiar with the use of telework and remote work. This resulted in the identification of five Fourth Estate components—Defense Logistics Agency; Defense Finance Accounting Service; Defense Contract Management Agency; Defense Human Resource Activity; and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

We evaluated the testimonial evidence we collected to identify the steps components have taken to evaluate the effects of the use of telework and to determine if these steps align with established federal requirements and guidance established in the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010,[62] OPM telework policy,[63] DOD strategic human capital planning guidance,[64] and our key practices for telework.[65]

To characterize component officials’ perceptions on the benefits and challenges related to use of telework and remote work, we asked officials about their component’s experiences with telework and remote work, including any supporting documentation. We reviewed the results of our interviews and related documents to identify the recurring experiences and examples raised during the interviews. Two analysts reviewed the experiences and developed three themes or categories. We then grouped these experiences and examples into one of three categories:(1) effect on mission productivity and efficiency, (2) effect on workforce management, or (3) effect on operational costs. We used sequential content analysis to identify the examples from each interview that fell into each of these categories. One analyst reviewed the materials and assigned experiences to the categories and a second analyst reviewed the results. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

We tallied these examples and reported on them using general terms to quantify users’ views. Any quantities other than “all” or “none” were defined as follows: “most” represents officials from 14 or more components, “more than half” represents 10 to 13 components, “several” represents officials from four to nine components, and “some” represents officials from one to three components. Because the sample was nongeneralizable, documentary and testimonial evidence on the benefits and challenges of using telework and remote work are not generalizable to components outside our sample. Additionally, because we collected and analyzed information that officials told us spontaneously and did not ask all officials the same questions about all possible experiences, the number of officials who experienced one of the categories may be underestimates of all officials who actually experienced them.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

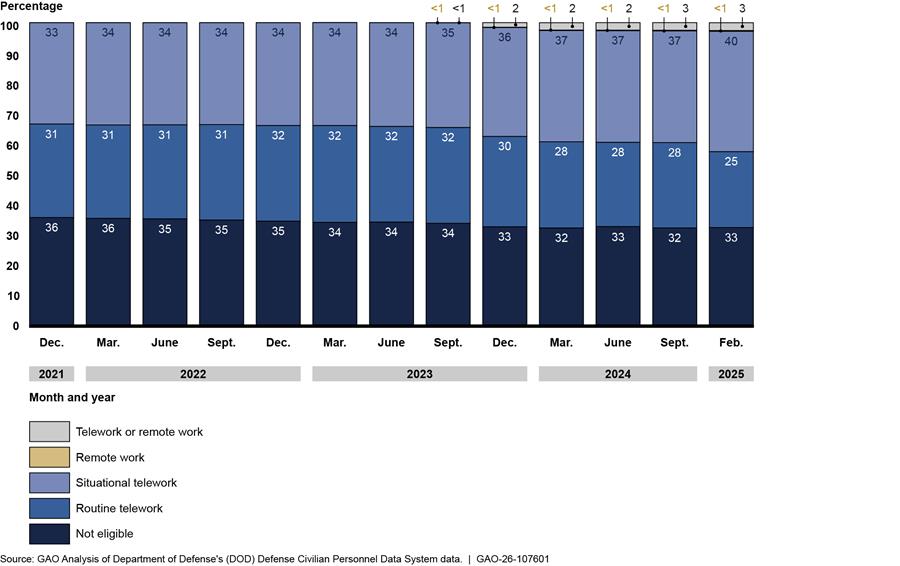

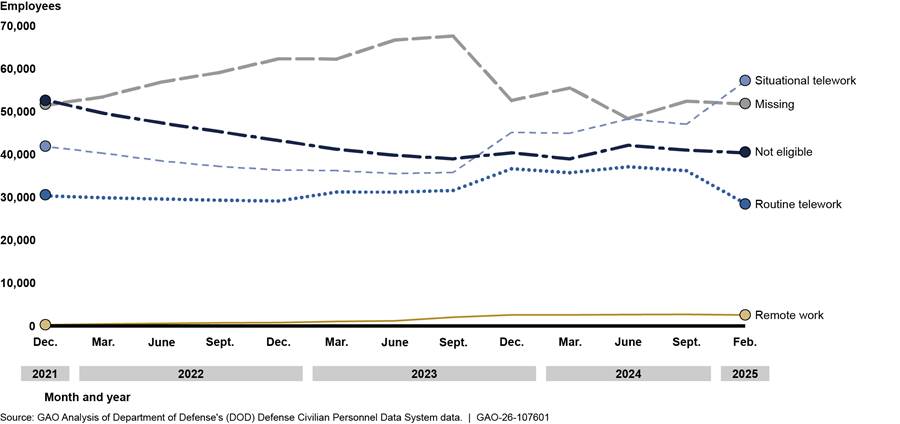

Data on Department of Defense (DOD) telework and remote work eligibility and use vary across the departments of the Army, Navy, Air Force and the Fourth Estate.[66] Figures 7 through 10 present data on position eligibility for the Fourth Estate and each military department for selected dates since December 2021. Figures 11-14 present data on employee eligibility for the Fourth Estate and each military department for selected dates since December 2021. Figure 15 and tables 4 through 6 present data on use of telework by each military department and the Fourth Estate.

Figure 7: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Fourth Estate Entities During Selected Dates from December 2021–February 2025

Note: Defense agencies along with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Joint Staff, the DOD field activities, and all other organizational entities in DOD that are not in the military departments or the combatant commands are sometimes referred to collectively as the “DOD Fourth Estate.”

Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an official duty station and enter an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official duty station is an approved alternative workspace.

Figure 8: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Army During Selected Dates from December 2021–February 2025

Note: Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an official duty station and enter an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official duty station is an approved alternative workspace.

Figure 9: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Navy During Selected Dates from December 2021–February 2025

Note: Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an official duty station and enter an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official duty station is an approved alternative workspace.

Figure 10: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Air Force During Selected Dates from December 2021–February 2025

Note: Positions designated as eligible for telework or remote work are positions where the employee in the position can either be assigned to an official duty station and enter an approved telework arrangement or is eligible to be approved as a remote employee whose official duty station is an approved alternative workspace.

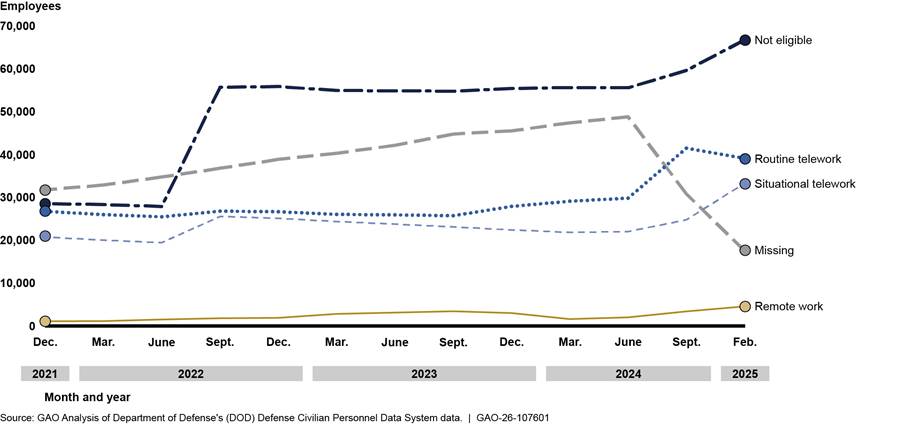

Figures 11 through 14 show employee eligibility—including missing eligibility data—for the Fourth Estate and the departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

Figure 11: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Fourth Estate Entities For Selected Dates from December 2021 through February 2025

Note: Defense agencies along with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Joint Staff, the DOD field activities, and all other organizational entities in DOD that are not in the military departments or the combatant commands are sometimes referred to collectively as the “DOD Fourth Estate.”

Figure 12: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Army For Selected Dates from December 2021 through February 2025

Figure 13: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Navy For Selected Dates from December 2021 through February 2025

Figure 14: DOD Workplace Flexibilities: Position Eligibility for Department of the Air Force For Selected Dates from December 2021 through February 2025

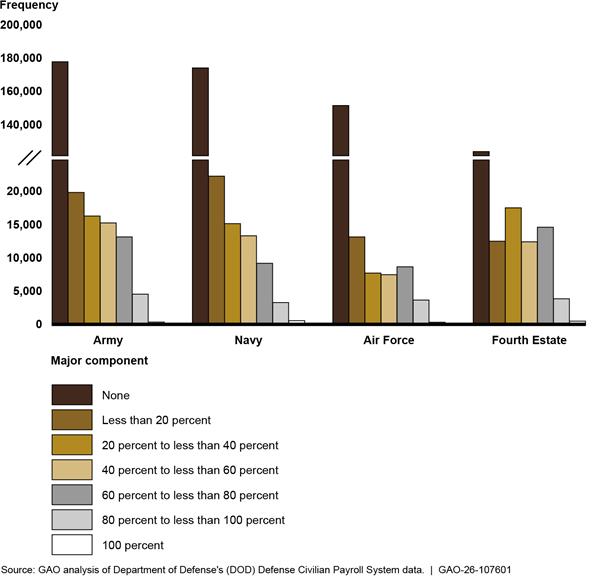

For pay periods ending in calendar year 2024, most civilians (about 627,000) did not participate in routine telework. Of the employees that did participate in routine telework:

· about 67,700 used telework less than 20 percent of the time;

· about 56,600 used it 20 to less than 40 percent of the time;

· about 48,400 used it 40 to less than 60 percent of the time;

· about 45,500 used it 60 to less than 80 percent of the time;

· about 15,300 used it 80 to less than 100 percent of the time; and

· about 1,700 used it 100 percent of the time.

For frequency of use by major component, see figure 15.

Figure 15: Frequency of Use of Routine Telework by DOD Major Component, for Pay Periods Ending in Calendar Year 2024

Note: Defense agencies along with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Joint Staff, the DOD field activities, and all other organizational entities in DOD that are not in the military departments or the combatant commands are sometimes referred to collectively as the “DOD Fourth Estate.”

For pay periods ending in calendar year 2024, Department of the Navy civilians conducted work in-person about 83 percent of the time. The use of telework and remote work varied by Department of the Navy subcomponents, with civilians working for the Commander, Naval Information Warfare Systems Command conducting the least work in-person (about 55 percent of total work hours), and U.S. Pacific Fleet civilians conducting the most work in-person (about 98 percent of the total work hours) (see table 4).

Table 4: Department of Navy: Use of Telework and Remote Work, by Percent of Total Work Hours, for Pay Periods Ending in Calendar Year 2024

|

Component |

In-person |

Routine |

Situational |

Remote |

|

Commander, Naval Information Warfare Systems Command |

54.80% |

26.27% |

13.96% |

4.97% |

|

Naval Supply Systems Command |

61.33 |

23.47 |

14.19 |

1.01 |

|

Office of Naval Research |

63.61 |

21.02 |

7.38 |

7.98 |

|

Secretary of the Navy Offices |

65.79 |

15.55 |

11.67 |

6.98 |

|

Naval Sea Systems Command |

72.17 |

13.02 |

13.65 |

1.16 |

|

Naval Education and Training Command |

76.87 |

13.90 |

9.11 |

0.13 |

|

Strategic Systems Programs |

77.86 |

10.54 |

10.91 |

0.69 |

|

Naval Medical Command |

77.88 |

10.30 |

10.25 |

1.57 |

|

Naval Air Systems Command |

77.98 |

12.84 |

7.22 |

1.96 |

|

Immediate Office of the Chief of Naval Operations |

79.45 |

8.41 |

9.05 |

3.09 |

|

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command |

79.53 |

14.63 |

4.53 |

1.31 |

|

Navy Reserve Force |

79.73 |

7.01 |

12.46 |

0.80 |

|

Bureau of Naval Personnel |

81.29 |

7.40 |

10.16 |

1.14 |

|

Naval Intelligence Command |

86.54 |

2.09 |

11.07 |

0.30 |

|

U.S. Marine Corps |

89.97 |

3.78 |

5.81 |

0.44 |

|

Naval Special Warfare Command |

90.01 |

2.34 |

5.44 |

2.21 |

|

Naval Systems Management Activity |

93.12 |

1.01 |

5.62 |

0.26 |

|

Commander, Navy Installations |

93.90 |

3.36 |

1.56 |

1.18 |

|

United States Fleet Forces Command |

96.11 |

1.91 |

1.93 |

0.05 |

|

U.S. Pacific Fleet |

97.58 |