MEDICAL DEVICE RECALLS

HHS and FDA Should Address Limitations in Oversight of Recall Process

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-26-107619, a report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact Mary Denigan-Macauley at deniganmacauleym@gao.gov

Why This Matters

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees recalls of medical devices that may present a risk to the health of users. The ramifications of using recalled devices—such as defective ventilators or pacemakers—include the potential for serious injury or death.

FDA’s oversight of medical products, including devices, has been on GAO’s high-risk list since 2009.

GAO Key Takeaways

From fiscal years 2020 to 2024, FDA oversaw the recall of 3,934 medical devices. All were voluntarily recalled by manufacturers. FDA can mandate a recall, although it rarely does so.

Insufficient staff limit FDA’s ability to conduct oversight activities, according to officials. For example, from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, FDA couldn’t meet its 3-month goal of terminating recalls (meaning FDA determines all reasonable efforts were made by the manufacturer to remove or correct the device) due to resource constraints. Some stakeholders said delays can affect patient care. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) oversees FDA and is currently undergoing reforms. Conducting workforce planning to determine the staffing and skills FDA needs for oversight would help HHS keep unsafe devices from continued use.

According to officials, FDA cannot require manufacturers to adopt its recommendations for how to carry out certain recalls. Some stakeholders said manufacturers and FDA communicating different information can be confusing. FDA officials said it can also result in inefficient use of resources. By working with FDA to assess if additional authorities are needed, and seeking them if beneficial, HHS may be better positioned to address current recall process inefficiencies.

Note: Termination means FDA determines all reasonable efforts were made by the manufacturer to remove or correct the device.

How GAO Did This Study

We reviewed FDA policies and guidance on the recall process and analyzed data from FDA’s Recall Enterprise System. We also interviewed FDA officials and 10 stakeholder groups representing providers, patients, and the medical device industry to get their perspectives on challenges FDA faces in overseeing recalls.

What GAO Recommends

We recommend HHS work with FDA: 1) to conduct workforce planning for device recalls, and 2) assess and seek, if needed, additional authority for manufacturer-initiated recall strategies. HHS concurred with the first recommendation and is taking the second under consideration.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CDRH |

Center for Devices and Radiological Health |

|

CPAP |

continuous positive airway pressure |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

MAUDE |

Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience |

|

OII |

Office of Inspections and Investigations |

|

RES |

Recall Enterprise System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 8, 2025

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

United States Senate

According to the World Health Organization, there are an estimated 2 million medical devices on the world market. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), currently oversees the safety of more than 190,000 distinct medical devices in use in the United States, an increase of about 15,000 since 2016. An integral part of patient care, medical devices include a wide range of products—from surgical masks to implantable pacemakers—intended to prevent, diagnose, cure, treat, or mitigate diseases or other conditions.[1]

If a device is found to be defective or unsafe once in use, the ramifications can be severe, potentially resulting in permanent injury or death to the individual using the device. A recall—the removal or correction of a medical device—is an important process overseen by FDA to ensure the agency’s effectiveness in mitigating serious health consequences associated with defective or unsafe medical devices.[2] There were about 900 recalls initiated by device manufacturers and overseen by FDA in each of the past 5 years, according to FDA’s publicly available data.[3]

Recent media attention and high-profile litigation involving a recalled continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine and other devices have raised questions about FDA’s oversight of recalls, and whether it sufficiently protects patients from harmful medical devices.[4] For example, FDA indicated on its website that it had received over 500 reports of deaths associated with the CPAP machine since 2021 prior to it being removed from the market in 2024. Our past work found similar issues relating to recalls. In 2011, we issued a report that recommended ways in which FDA could enhance its oversight of recalls.[5] The agency has implemented our related recommendations. Despite these efforts, FDA’s oversight of medical products, including devices, has remained on GAO’s High-Risk List since 2009, in part because staffing and workforce challenges have been only partially addressed.[6]

You asked us to review the medical device recall process, including FDA’s actions. In this report, we

1. describe the medical device recall process, and how FDA uses medical device recall data; and

2. examine challenges affecting the medical device recall process, and FDA’s efforts to address them.

To describe the medical device recall process, and how FDA uses medical device recall data, we reviewed FDA procedures and policies—such as a regulatory procedures manual and guidance—that outline the manufacturers’ and FDA’s responsibilities in initiating and conducting medical device recalls. We also reviewed federal laws and regulations and internal agency policies that dictate how the agency initiates, oversees, and resolves medical device recalls. We limited our review to policies and procedures that have been in effect since 2019, because FDA underwent a reorganization that year that included a new approach to guide its oversight of medical devices.

To better understand the landscape of medical device recalls, we analyzed data from FDA’s Recall Enterprise System (RES) on all medical device recall events, hereafter referred to as recalls, initiated between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2024, the most recently available full fiscal year data. Specifically, we analyzed data on the total number of recalls and on several device characteristics, such as the medical specialty of the devices (e.g., cardiovascular or orthopedic), and the method by which the recall was initiated (e.g., voluntarily by the manufacturer or mandated by FDA). After performing data checks on medical device recall observations in RES, we found the data reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. For more information about our data analysis, please see appendix I. Lastly, we interviewed FDA officials who are familiar with the device recall policies and processes, and officials who are responsible for monitoring the recall database. These officials typically worked in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) and the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII).

To examine the challenges affecting the medical device recall process and FDA’s efforts to address them, we interviewed FDA officials responsible for overseeing device recalls and a nongeneralizable selection of 10 stakeholder groups representing providers (including hospitals), patients, the medical device industry, and other subject matter specialists in medical device recalls about their perspectives on challenges FDA faces in the recall process. We selected these stakeholders to represent variation in medical device recall process experiences, organizational or association type, size, and medical expertise. In addition, we conducted a literature review to identify current research (fiscal years 2020 through 2024) that describes any challenges associated with the medical device recall process. We also assessed FDA efforts to address the challenges against selected leading practices identified by GAO for agency reforms and key principles for effective strategic workforce planning.[7]

We also assessed FDA efforts to address the challenges against five key elements of effective oversight identified in our prior work.[8] To ensure the elements could be applied to FDA’s role in the medical device recall process, we conferred with subject matter specialists and reached a general consensus. We did so by selecting and speaking with stakeholders with relevant knowledge and expertise on regulatory bodies. See appendix I for additional details on our scope and methods for this objective.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

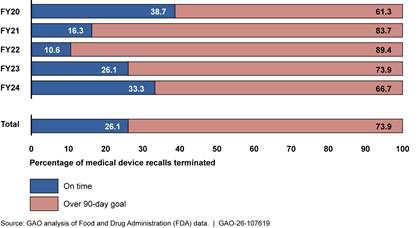

Medical Devices and Recalls

Medical devices encompass a wide range of products—from bandages to ventilators—that pose varying amounts of risk to the user. FDA classifies medical devices into one of three classes based on the level of risk they pose to the user, with class I being the lowest risk, and class III being the highest.[9] Examples of types of devices include those listed in Figure 1.

Once a medical device enters the U.S. market, the agency continues to monitor its safety and effectiveness. This is known as postmarket surveillance.[10] As part of this surveillance, FDA requires device manufacturers, importers, and device user facilities—such as hospitals—to submit reports informing FDA about adverse events that have occurred, such as device-related deaths and serious injuries, or certain device malfunctions.[11] In addition, FDA also encourages health care professionals, patients, and consumers to submit voluntary reports about serious adverse events that may be associated with a medical device.[12] FDA posts redacted versions of these reports on its public online database, the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (known as MAUDE).[13] In addition to monitoring adverse event reports about devices, FDA conducts risk-based inspections of device manufacturing sites to check for compliance with FDA requirements or potential safety problems.[14]

When either the manufacturer or FDA becomes aware of a

defect or a safety concern with a medical device, either party may initiate a

recall. FDA classifies recalls into one of three categories to indicate the

relative degree of health hazard presented by using the device.[15] It is important to note that FDA’s

device classification and recall classification schemes carry opposite

designations. The potential degree of health risk associated with device

classes is designated from class III (high) to class I (low), while the

potential risk associated with recall classes is designated from class I (high)

to class III (low). Table 1 illustrates these recall risk classifications with

examples.

|

Recall Classification |

Degree of Health Hazard from Using Device |

Device Recall Example |

|

Class I (high risk) |

There is a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, the device will cause serious adverse health consequences or death. These are the most serious recalls. |

Blood pumps. Defective blood pump catheters were piercing the wall of the left ventricle in the heart, leading to serious injuries and deaths. |

|

Class II (moderate risk) |

The use of, or exposure to, the device may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences, or the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote. |

Joint replacement devices. Knee, ankle, and hip replacement parts were packaged in defective bags, exposing the devices to oxidation. Oxidation can accelerate device wear or failure and might lead to revision surgery. |

|

Class III (low risk) |

The use of, or exposure to, the device is not likely to cause adverse health consequences. |

Respiratory breathing circuit. The device packaging was printed with the incorrect expiration date. The expiration date printed was actually the date of the manufacture, which was earlier. |

Source: GAO analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documents. | GAO‑26‑107619

FDA Offices Involved in Medical Device Recalls

There are two FDA offices primarily involved in monitoring devices and overseeing various aspects of the recall process: the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) and the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII). The roles and responsibilities the two offices play in device recalls depends on the class of the recall, the phase of the recall, and the recall action required as set out in FDA policies. For example, OII’s Division Recall Coordinators may terminate recalls—which occurs when FDA officials determine that all reasonable efforts have been made to remove or correct a device—of class II or class III recalls unilaterally. However, terminations for class I recalls (the most serious) require concurrence from CDRH officials. This is because class I recalls are riskier and require additional expertise to determine if the risk of the recalled device has been sufficiently addressed.

Both CDRH and OII have responsibilities in addition to their work in overseeing device recalls. For example, CDRH authorizes devices for the market, more broadly facilitates medical device and scientific innovation, and helps communicate information about devices to consumers. In addition to handling aspects of medical device recalls, OII leads all inspection, investigation, and criminal law enforcement activities for any issues related to all FDA product types—devices, food, drugs, biological products, cosmetics, and tobacco.[16]

FDA Reorganizations Affecting Medical Device Recalls

In 2019, CDRH reorganized and developed a new approach to guide its oversight of medical devices—the “Total Product Life Cycle.” This new approach allows the agency to review and monitor medical devices throughout the entire life cycle within a product team rather than by individual stage of the product (e.g., pre-market versus post-market). Another FDA reorganization in October 2024 created a new model for OII’s field operations and a new name. Specifically, FDA moved all domestic compliance branch functions from the Office of Regulatory Affairs and placed them in their respective centers, including CDRH, and changed the name from the Office of Regulatory Affairs to OII to better convey its role. Additionally, according to officials, FDA consolidated medical device recall coordinators into one OII branch with one manager. Prior to OII’s current structure, all medical device program coordinators and investigators were specialized, which had been in place since a 2017 reorganization, according to FDA officials.

Device Manufacturers and FDA Participate in the Multistep Device Recall Process, and FDA Uses Recall Data to Identify Risk and Monitor Performance

The medical device recall process involves several steps, with both FDA and device manufacturers having different responsibilities throughout. In addition to its roles in the recall process, FDA reviews recall data to inform its oversight of device manufacturers and to monitor its performance against agency goals for recall timeliness.

The Medical Device Recall Process Involves Several Steps, with Manufacturers and FDA Each Playing a Role

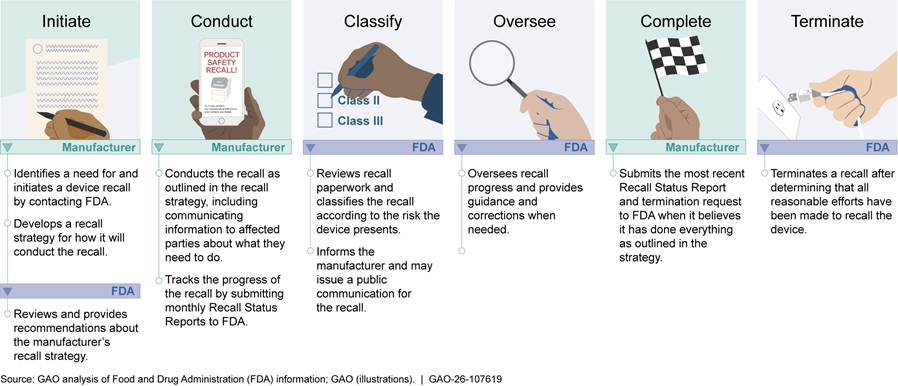

Based on our review of FDA information, the medical device recall process generally consists of the following steps: initiate, conduct, classify, oversee, complete, and terminate. The steps may happen sequentially or at, or around, the same time.

Initiating a Recall

A device manufacturer can voluntarily initiate a recall, which includes manufacturer-identified, FDA-identified, and FDA-requested recalls, or FDA can mandate one. FDA requires manufacturers to submit a report about any correction or removal of a device to FDA within 10 working days of initiating such action if the manufacturer did so to reduce a risk to health posed by the device or to remedy a violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act caused by the device that may present a risk to health.[17] Division Recall Coordinators then enter the information into the agency’s Recall Enterprise System.

There are four ways a device recall can be initiated.

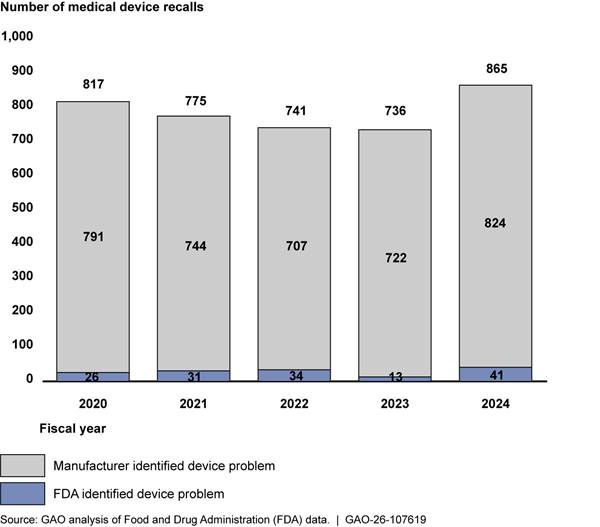

Manufacturer-identified recalls. A manufacturer identifies an issue with a device and then voluntarily initiates a recall.[18] According to our analysis of FDA recall data for fiscal years 2020-2024, manufacturer-initiated recalls for which the manufacturer identified the issue accounted for 96 percent (3,788 out of 3,934) of recalls.

FDA-identified recalls. FDA determines a device violates the law, informs the manufacturer of the violation, and then the manufacturer recalls the device voluntarily.[19] This accounted for 4 percent (145 out of 3,934) of the recalls in our analysis period. See figure 2 below.

Note: During this same time period, there were no instances where FDA had mandated a recall, and one instance where a manufacturer initiated a recall at FDA’s request, which is still considered voluntary.

|

Example of a Recall That the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Requested In 2022, through one of FDA’s inspections of a device manufacturing facility, the agency determined that certain medical devices that a manufacturer was marketing and selling for diagnostic purposes had not been approved by FDA for the U.S. market. In November 2022, FDA sent a warning letter to the manufacturer requesting that it remove the devices from the market and to provide details to FDA about its removal efforts. Then, in August 2023, FDA mailed the manufacturer an official FDA Requested Recall letter, stating that the recall would be categorized as a class II recall (medium-risk). Later that month, the manufacturer initiated a recall by sending recall notices out to users. Source: GAO review of FDA recall information. | GAO‑26‑107619 |

FDA-requested recalls. FDA may request that a manufacturer initiate a recall when the agency determines that a device presents a risk of illness, injury, or gross consumer deception; the manufacturer has not initiated a recall; and agency action is necessary to protect public health and welfare.[20] The manufacturer must agree to the request in order for the recall to be initiated. In the 5 years of data that we examined, we found one instance where FDA requested a manufacturer to initiate a recall. See sidebar for more details.

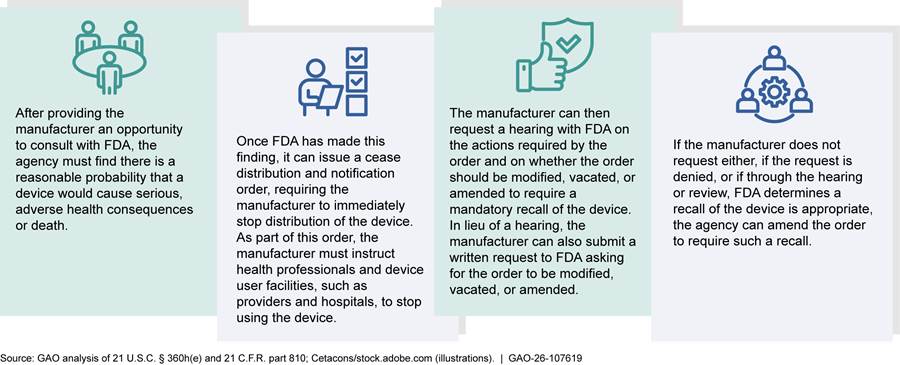

FDA-mandated recalls. FDA has the authority to mandate the recall of a device by the appropriate entity, including manufacturers, importers, distributors, or retailers of the device.[21] Using this authority involves several steps. If FDA finds there is a reasonable probability that a device would cause serious, adverse health consequences or death, it can issue a cease distribution and notification order, which requires the manufacturer to immediately stop distributing the device and to notify health professionals and user facilities they should no longer use the device. The order will provide the manufacturer with an opportunity for a regulatory hearing; after the opportunity for the hearing, FDA can amend the order to require a recall or vacate it.[22] See figure 3.

Figure 3: Selected Steps of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Mandatory Device Recall Process

In almost every instance, the manufacturer voluntarily initiates a recall before FDA has to mandate one. There were no instances of FDA mandating a recall in the 5 years of data that we analyzed (fiscal years 2020-2024). FDA has used its mandatory device recall authority four times since it received it in 1990.[23] Specifically, FDA used the authority to recall a defective wheelchair lift, a ventilating system, a feeding pump, and a disinfecting solution. The agency has not mandated a device recall since 1992.

|

How the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) identifies issues with devices that lead to a recall. FDA officials from both the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII) and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) may discover a medical device issue that a manufacturer has either not discovered or is not acting on. These officials may do so through a risk-based manufacturer site inspection or through reviews of adverse event report data, which could include instances of device-related deaths, serious injuries, or device malfunctions. FDA posts redacted versions of these reports on FDA’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database, a public online system. FDA officials told us that they receive and review 2 to 4 million adverse event reports per year. FDA classifies recalls into one of three categories to indicate the relative degree of health hazard presented by using the device. See examples below. |

|

|

Class II recall initiated in 2024 In 2023, an investigator discovered a problem with a company’s warming blanket to help treat hypothermia patients. The problem was identified through an inspection of a manufacturer’s site. Specifically, FDA discovered that there had been instances of this warming blanket becoming too hot and causing skin burns. FDA also learned that this manufacturer did not report these instances to MAUDE, as they are required to do. Further, the manufacturer did not have proper procedures in place to do so.a FDA issued a warning letter to the manufacturer in March 2024 about these problems. Then, in December 2024, the manufacturer initiated a recall of the device, which FDA classified as Class II (moderate risk) and is ongoing as of July 2025. |

Class I recall initiated in 2022 In 2022, officials from CDRH issued a letter to health care providers about an evaluation of reports for an endotracheal tube made of silicone.b According to the letter, the agency had received adverse event reports of it not ventilating properly, which could cause an airway obstruction in patients’ throats and ventilation failure resulting in death. Two days later, the manufacturer issued a safety notice to its customers and provided updated recommended actions for when airway obstruction is encountered. FDA classified the recall as Class I in September 2022. The manufacturer later added new information about the recall twice in 2024. The first update occurred in January related to the availability of an updated instructions for use, and in July, the company issued another recall notice instructing customers to remove devices and stop use after it had received 77 complaints between March 2020 and May 2024.c As of July 2025, the recall is ongoing. |

Source: GAO review of FDA documents. | GAO‑26‑107619

aIn addition to requiring reporting of certain adverse events, FDA also requires device manufacturers, importers, and device user facilities to develop and maintain written procedures to determine when an event meets the criteria for reporting. See 21 C.F.R. §§ 803.17; 803.20(b).

bAn endotracheal tube is a flexible tube that is placed in the windpipe through the mouth or nose to assist with breathing during surgery or to support people with an airway obstruction.

cAccording to the company’s recall notice, the 77 complaints ranged from hypoventilation, to respiratory arrest, to brain injury, and death.

Lastly, as part of this initiation phase, either the manufacturer or FDA will develop a recall strategy, which is a plan for how the manufacturer will implement the recall. It describes whom the manufacturer will notify, how it will do so, and it will indicate if there is a need for public warning.

The manufacturer is responsible for creating the strategy for recalls it initiates and for recalls that FDA mandates; FDA develops it for recalls it requests.[24] For manufacturer-initiated recalls, FDA officials will review the adequacy of the manufacturer’s proposed strategy and recommend changes as appropriate.[25] This review period may require back-and-forth correspondence with the manufacturer, according to FDA officials. According to officials, FDA does not have the legal authority to require the manufacturer to implement FDA’s recommendations. For mandatory recall strategies, FDA will review the proposed strategy and make any changes it deems necessary.[26]

Conducting a Recall

After the manufacturer initiates the recall, it is to then conduct the recall as outlined in the recall strategy. This involves communicating information about the recall to affected parties in the distribution chain—such as retailers, providers, or patients—and coordinating the removal and retrieval of the device, if applicable, from hospitals, other health care settings, or a patient’s home.

According to FDA policy, it is the manufacturer’s responsibility to determine whether the recall is progressing satisfactorily. The manufacturer is to address the effectiveness of the recall by conducting “effectiveness checks” at the level stipulated in its recall strategy. Effectiveness checks are meant to verify that the affected parties have received the manufacturer’s notification about the recall and are taking appropriate actions.[27] Manufacturers are not required to perform these checks for every recall.[28]

Additionally, FDA requests that manufacturers submit regular “Recall Status Reports” to FDA detailing recall progress.[29] These status reports should include, for example, dates and methods of customer notification; number of customers notified; number of customers that responded; quantity of recalled product returned; number of customers that did not respond; and estimated time frame for completion of the recall.

Classifying a Recall

FDA officials are responsible for classifying recalls, which indicates the product’s relative degree of health hazard. To do this, FDA will conduct a “health hazard” evaluation for devices being recalled or considered for recall. During this evaluation, FDA is to take into account certain factors, such as whether any injuries have already occurred from use of the product and an assessment of how serious the health hazard may be for the populations at risk.[30] FDA may use a precedent evaluation for instances where a device and reason for recall has basically the same defect as a previously classified recalled device.

As previously described, there are three recall classification categories, with class I recalls carrying the most risk and class III carrying the least. OII’s Division Recall Coordinators are responsible for reviewing the recall initiation paperwork and proposing a recommended classification to CDRH officials, according to FDA officials. According to officials, CDRH officials then decide what the classification should be, and upon classification of the recall, the RES will automatically send an email to the manufacturer notifying it of the recall classification.

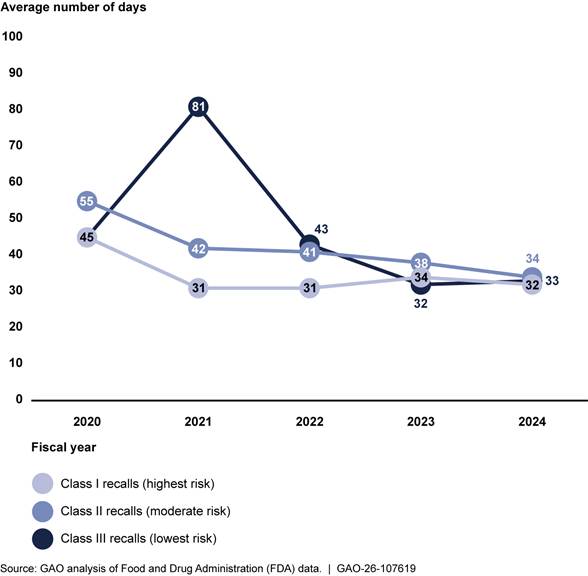

We analyzed FDA data from fiscal years 2020 to 2024 to determine time frames related to the classification process and found variation over the 5-year period in the number of business days between initiation and classification.[31] This variation occurred across all three classification types but generally decreased during this time period. For example, the number of business days between initiation and classification for class I recalls ranged from 45 in 2020 to 32 in 2024. In contrast, class III recalls ranged from a high of 81 business days in 2021 to a low of 33 days in 2024. See figure 4.

Note: We calculated business days using FDA’s methodology. That is, we took the count of days between two dates and subtracted Saturdays, Sundays, and federal holidays.

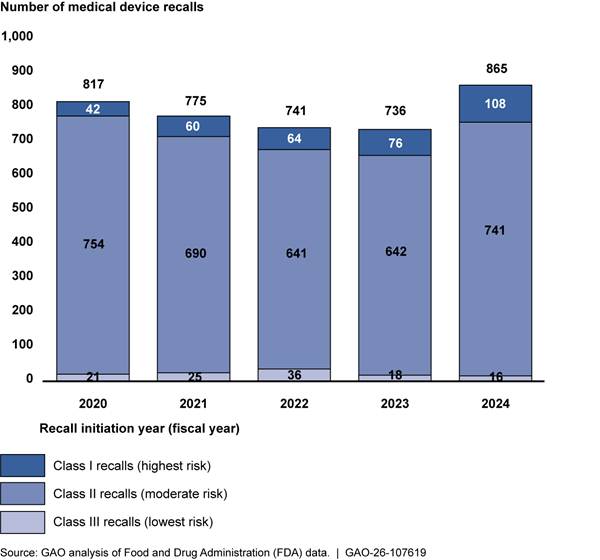

While our analysis of the recall data found that recalls were represented across all classifications and medical specialties, class II recalls and certain specialties represented the majority of recalls. Specifically, of the 5 years of data that we analyzed (fiscal years 2020-2024), class II medical device recalls—moderate risk—accounted for 88 percent of all device recalls (3,468 out of 3,934). Class I recalls (the highest risk) represent about 9 percent for the total time period we analyzed (350 out of 3,934), and class III make up the remaining 3 percent (116 out of 3,934). These percentages are generally consistent when analyzed by year. See figure 5 below.

Our analysis found that seven medical specialty areas accounted for three-fourths (75 percent) of device recalls during this time period, with the highest three being cardiology, orthopedics, and general and plastic surgery (see table 2). The remaining 25 percent of recalls were for devices in 19 other specialty areas (such as dental and neurological devices); no other specialty accounted for more than 6 percent of recalls.

|

Medical specialty area (device examples) |

Number of |

Percentage of all recalls |

Number of class I recalls |

Percentage of all class I recalls |

|

Cardiovascular (heart valves, pacemakers) |

619 |

16 |

84 |

24 |

|

Orthopedic (artificial joints, screws) |

500 |

13 |

2 |

1 |

|

General and plastic surgery (medical staples, breast implants) |

443 |

11 |

16 |

5 |

|

General hospital and personal use (infusion pumps, including implantable programmable pumps) |

428 |

11 |

84 |

24 |

|

Chemistry (test systems, such as those for measuring blood glucose) |

406 |

10 |

8 |

2 |

|

Gastroenterological and urological (catheters) |

275 |

7 |

9 |

3 |

|

Anesthesiology (ventilators) |

261 |

7 |

93 |

27 |

|

All other specialtiesa |

1002 |

25 |

54 |

15 |

|

Total |

3934 |

100 |

350 |

100 |

Source: GAO analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data. | GAO‑26‑107619

aOther specialties (and devices) include, among others, dentistry (tooth implants), and ear nose and throat (endotracheal tubes).

When examining class I recalls, we found that the anesthesiology specialty area had the highest number of class I recalls (93). Anesthesiology medical devices that were recalled included ventilators and epidural kits. These devices, together with those from cardiovascular, and general hospital/personal use—accounted for 75 percent of all class I recalls during this same period.

Overseeing a Recall

FDA oversees the manufacturer’s handling of the recall and provides guidance and correction when needed. Agency policy states that FDA review the Recall Status Reports to assess the progress of the recall. For some recalls, FDA—or a third party with whom FDA contracts—may also conduct what is known as a “recall audit check” to determine if the appropriate parties received notification of the recall and followed the instructions in the notification. This check may be done in the form of phone calls, emails, or in-person visits to parties in the distribution chain to ensure the effectiveness of the recall.

Agency policy states that if FDA discovers issues with the effectiveness of a manufacturer’s recall, it must ensure that the relevant party takes appropriate and timely follow-up action. For example, FDA may discuss the situation with the manufacturer and determine what action the manufacturer intends to take to improve its recall efforts. FDA may also send the manufacturer an “ineffective recall letter.” According to officials, this is sent when the agency determines that the recall is ineffective at removing or correcting the recalled medical device. If FDA does not find the manufacturer’s actions to improve its recall sufficient, the agency may take additional actions such as issuing initial or further public warning, turning the recall into an FDA-requested or mandated recall, or initiating an injunction.[32] Additionally, if the manufacturer does not comply with information requests, FDA may conduct an onsite visit.

Completing and Terminating a Recall

FDA considers a recall complete when the recall action reaches the point at which the manufacturer has taken custody of all outstanding products that could reasonably be expected to be recovered or has completed all product corrections. When the manufacturer believes it has done everything as outlined in the recall strategy and has, therefore, completed the recall, it can submit a termination request to FDA, along with the most current recall status report and a description of the disposition of the recalled device.[33] The recall coordinators within FDA will then change the recall’s status in their system from “ongoing” to “completed.” According to officials, recall coordinators make this change based on the manufacturer’s determination that the recall is completed.

FDA will terminate a recall when it determines that all reasonable efforts have been made to remove or correct the device in accordance with the recall strategy and that proper disposition has been made according to the degree of hazard.[34] To terminate, FDA will review completed recall audit checks when applicable, the manufacturer’s Recall Status Reports, product disposition records, and other reports as appropriate, according to agency guidance. Recall coordinators indicate termination by updating the recall’s status to “terminated” and by issuing a written notification to the manufacturer. In cases where manufacturers are correcting a device, rather than removing it, FDA termination of a recall could result in a device staying on the market but with repairs or modifications made.

As previously mentioned, termination of a class I device recall requires concurrence from CDRH. For class II and III recalls, officials at OII may terminate without CDRH’s approval. According to agency policy, FDA should terminate recalls within 3 months after the manufacturer completes the recall.

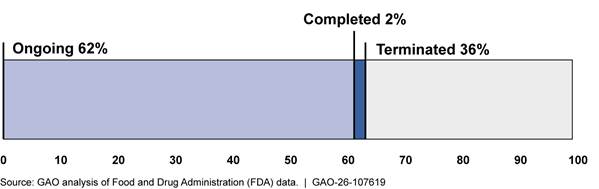

Of the 3,934 recalls initiated from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, we found that 62 percent were ongoing, and the remainder were either completed or terminated (see figure 6). Of the ongoing recalls, 64 percent (1,553 out of 2,433 ongoing recalls) were initiated in fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

Our analysis showed there is variation in the time—number of business days—between the manufacturer’s initiation and FDA’s termination of a recall.[35] According to FDA officials, one reason for this is that manufacturers might not provide all the required information in the early phases, which can result in FDA taking longer to classify the recall. Another reason for the variation, according to FDA officials, is that sometimes identifying and addressing the root cause of the recall takes a long time, extending the total number of days from initiation to termination. Table 3 illustrates this variation below.

|

Class of Recall |

Number of terminated recalls |

Average number of days (median) |

Minimum

number of |

Maximum number of days |

|

Class I |

98 |

632 (610) |

162 |

1210 |

|

Class II |

1252 |

479 (457) |

33 |

1242 |

|

Class III |

58 |

396 (416) |

42 |

1094 |

Source: GAO analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data. | GAO‑26‑107619

Note: We analyzed a total of 3,934 medical device recall events initiated from fiscal years 2020-2024. Of those 3,934 recall events, 1,408 had been terminated at the time of our review. We calculated business days using FDA’s methodology. That is, we took the count of days between two dates and subtracted Saturdays, Sundays, and federal holidays.

Please see figure 7 for a summary of the medical device recall phases.

FDA Uses Device Recall Data to Inform Oversight Activities and Monitor Agency Performance

FDA uses the information it has collected on device recalls to inform its ongoing oversight of device manufacturers, as well as to monitor its performance against agency goals for recall timeliness.[36] Specifically, every year CDRH develops a “Specific Product Risk Assignment,” which is a risk-based plan that helps inform device manufacturing site inspection planning. According to officials, the goal of this effort is to use postmarket data to identify broad quality issues across a device category, including identifying trends in recent recalls for specific product areas. FDA uses results from these analyses to inform selection of which manufacturing sites FDA should inspect.

Additionally, FDA has two efforts that help officials monitor the agency’s performance in meeting its time frame goals for device recalls.

· FDA issues an internal annual “compliance evaluation plan” that serves as a strategic assessment of recalls for numerous products that took place in prior years, broken down by type of recall. Specifically, the plan includes recall data for medical devices, drugs, biological products, and human and animal food products. This plan analyzes and presents data on certain metrics, such as time frames from recall initiation to press release issuance about the recall, and from recall initiation to completion. It also includes information on general trends and outliers, and it offers explanations for such outliers and recommended practices to improve upon these metrics.

· FDA has an internal live monitoring dashboard for medical devices that focuses on a number of performance indicators, and officials told us they consult the dashboard on a monthly basis to help inform the progress of recalls. The performance indicators include, for example, the time it takes FDA to classify a recall, the time it takes to conduct a recall audit check, and the time it takes FDA to terminate a recall. Officials can view the data broken down by recall class. FDA demonstrated how it routinely consults the dashboard to help it oversee the progress of a recall and whether the agency is meeting its goals. For example, officials provided us with a demonstration of how they use the dashboard each month to monitor time frames for certain phases of the recall process.

FDA Is Taking Steps to Address Challenges in the Recall Process but Has Not Assessed Staffing Needs and Legal Authorities

FDA faces several challenges in the medical device recall process, including staff constraints for the large number and scope of medical device recalls, according to officials. FDA is taking steps to address transparency and communication challenges described by stakeholders and the literature we reviewed. However, FDA has not conducted new workforce planning to determine what staffing resources and skills it needs to effectively carry out its responsibilities in light of ongoing departmental reform changes. In addition, FDA has not assessed whether its authority over manufacturer-initiated recalls is sufficient or whether new authorities are needed.

Staff Constraints Limit FDA’s Oversight of Numerous Recalls of Complex Devices

According to FDA officials, the agency faces several challenges in the device recall process. Three challenges affect the agency’s oversight of recalls. The first is the large number of recalls, officials told us. In any given year, there are more device recalls than biologics and drug recalls combined. FDA’s publicly available data show that, in fiscal year 2024, there were 1,017 medical device recalls compared to 333 biologics recalls and 318 drug recalls.[37] FDA OII officials explained that they must process a large volume of medical device recalls with limited time, insufficient staffing levels, and information technology database systems that require extensive manual data entry.

|

Example of Medical Device Complexity Insulin pumps have both hardware and software components. The pump itself is physical hardware, but the software within the pump calculates and delivers doses of insulin based on continuous glucose readings. Given this, a recall for the insulin pump could include a correction to the pump’s software, or it could mean a correction or removal of the physical pump. Source: GAO analysis; romaset/stock.adobe.com (photo). | GAO‑26‑107619 |

The second challenge to its oversight, according to FDA officials, is the scope of medical devices, which is vast, and often includes rapid improvements and continuous enhancements compared to biologics and drugs. According to officials, this means that overseeing medical device recalls can be more complex and more challenging compared to recalls for drugs or biologics.[38] For example, devices include physical products, such as catheters or defibrillators, or nonphysical products, such as predictive or diagnostic software. A single device also can be a combination of both. (See sidebar for a specific example.) As such, a recall may involve a correction or removal of a single device, or one or multiple components of a single device.

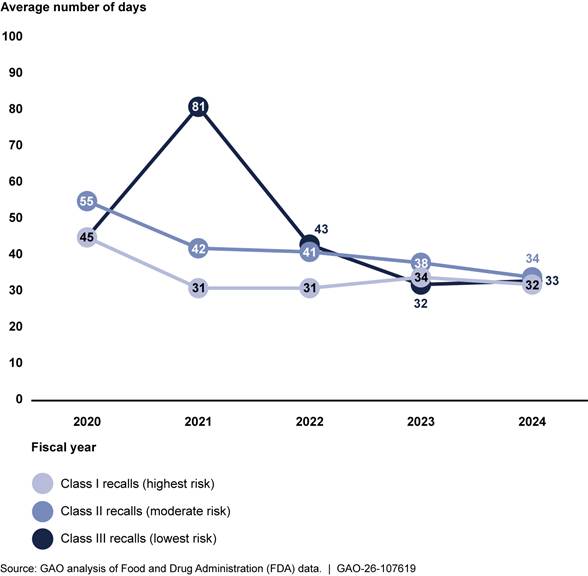

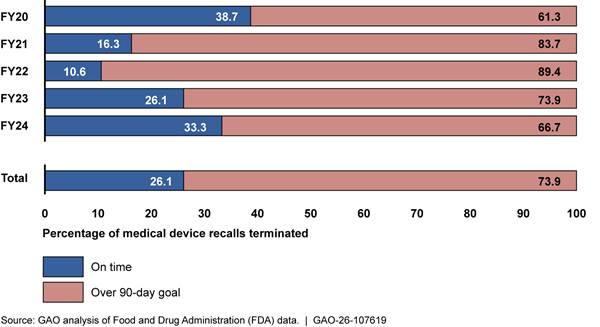

Finally, FDA OII officials told us that they often do not have sufficient staff to conduct necessary medical device recall oversight activities.[39] According to officials, examples of important oversight activities not conducted include reviewing manufacturer Recall Status Reports and conducting in-person recall audit checks. Officials said they often forgo these activities because they must shift staff’s priorities to focus on the highest risk recalls (class I) and on the earlier stages of the recall process (initiation and classification).[40] Furthermore, OII officials stated that the final stage of the recall process, recall termination, is on the “back burner” due to limited resources. This was confirmed by our analysis of FDA data, which found that 74 percent of recalls across fiscal years 2020-2024 exceeded FDA’s policy of terminating a recall within 3 months of receiving the manufacturer’s request to terminate.[41] See figure 8.

Note: We analyzed a total of 3,934 medical device recall events initiated from fiscal years 2020-2024. Of those 3,934 recall events, 1,408 had been terminated at the time of our review. According to agency policy, FDA should terminate recalls within 3 months after the manufacturer completes the recall. Based on confirmation from FDA officials, our analysis measured timeliness as 90 business days, and we used the definition of business days they provided. That is, we took the count of days between two dates and subtracted Saturdays, Sundays, and federal holidays.

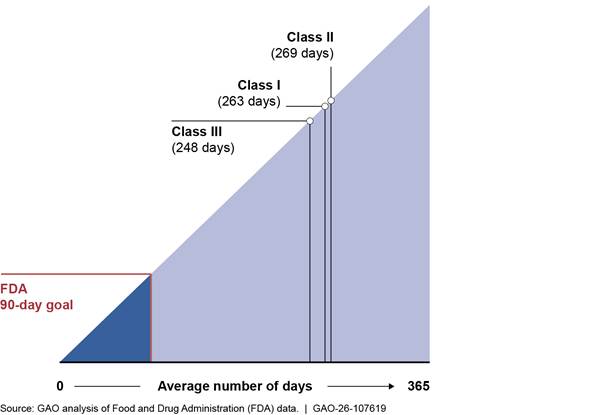

Further, our analyses found that class I recalls—the highest risk class—took an average of 263 business days from completion to termination in this time period (ranging from 11 to 882 days). Class II and III recalls took an average of 269 and 248 days, respectively. Stakeholders from both trade associations and a subject matter specialist said these time frames may cause confusion, and a trade association stakeholder said this confusion could have an effect on patient decisions as it may suggest there is a problem with a device when it has, in fact, been resolved. See figure 9.

Note: We analyzed a total of 3,934 medical device recall events initiated from fiscal years 2020-2024. Of those 3,934 recall events, 1,408 had been terminated at the time of our review. According to agency policy, FDA should terminate recalls within 3 months after the manufacturer completes the recall. Based on confirmation from FDA officials, our analysis measured timeliness as 90 business days, and we used the definition of business days they provided. That is, we took the count of days between two dates and subtracted Saturdays, Sundays, and federal holidays.

Stakeholders from both trade associations we interviewed also mentioned waiting long periods of time—from months to years—between submitting a request to terminate a recall and FDA terminating the recall. Our data analyses confirmed this (see figure 9 above), with the average number of days for class I recalls exceeding the 3-month goal by 173 business days.

These same stakeholders also reported that these protracted timelines may affect patient care and could lead to confusion for providers and the public, as the recall stays open until terminated. This can be confusing and potentially harmful for patients and providers, because if a device has an open recall, patients may seek a less helpful treatment than that device, or a treatment that might not be recommended, according to one of these stakeholders. Additionally, the extended ongoing status could lead the public to think that manufacturers are not attempting to resolve a recall when they are, according to the other stakeholder.

FDA has attempted to resolve staffing issues by reorganizing its staffing structure and hiring additional staff. In October 2024, according to officials, OII moved all medical device recall coordinators under one centralized branch with one manager. Shortly after this reorganization, OII started the process of hiring three additional recall staff, and it also awarded a contract for a fourth additional person to support the recall staff. However, due to a federal hiring freeze that began in early 2025, OII was not able to fill these positions, and the contract for the additional staff person was canceled, according to officials.[42]

FDA acknowledges staffing constraints, but the agency does not have comprehensive information on the number and type of staff that would be sufficient to conduct its oversight of device recalls. We recommended in 2022 that FDA develop and implement an agencywide strategic workforce plan to document human capital goals and strategies, including monitoring and evaluation.[43] FDA implemented this recommendation by completing an agencywide strategic workforce plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027 that included strategic workforce plans for OII and CDRH in alignment with the agencywide plan. However, in early 2025, FDA officials told us that the agency now considers those plans obsolete.

In March 2025, HHS announced a major reorganization that will focus on saving money, streamlining functions, implementing new priorities, and making the agency more responsive and efficient, according to the announcement.[44] According to a fact sheet linked in the announcement about the reorganization, HHS plans to reduce FDA’s workforce.[45] However, FDA officials have not done a new assessment of workforce needs and have not determined the number of staff and the skills needed to meet their current and future oversight needs to effectively manage medical device recalls. Coordination with HHS to develop a new workforce strategy is warranted due to the department’s restructuring efforts in light of the federal hiring freeze.

Leading practices for agency reforms identified in our prior work includes four broad categories of practices to help assess agency reform efforts. One category of these leading practices focuses on agency strategic workforce planning efforts, which are used to determine whether an agency has the needed human capital resources and capacity, including the skills and competencies, in place both during and after the proposed reforms or reorganization.[46] In the context of FDA oversight of device recalls, this means assessing the staffing and skills the agency needs now while reforms are underway and after once they are completed. Further, our prior work on effective strategic workforce planning identifies key principles that should be addressed in this process, including developing strategies that are tailored to address gaps in number, deployment, and alignment of human capital approaches for enabling and sustaining the contributions of all critical skills and competencies.[47]

By working with FDA to conduct such strategic workforce planning, HHS would have better assurance that FDA has the needed resources, capacity, and skills in place to effectively process and oversee recalls, as well as to conduct its routine inspections, as required. This includes the staff needed with the appropriate knowledge and skills to review manufacturers’ Recall Status Reports, conduct in-person recall audit checks, and terminate recalls within the agency’s stated time frame goals. This would ultimately help HHS keep defective or unsafe devices from continued use, as FDA’s termination of a recall indicates all reasonable efforts have been made to remove or correct the device.

FDA Has Made Changes to Increase Transparency, but It Has Not Assessed Whether It Has Sufficient Authority Over Manufacturer-Initiated Recalls

FDA Has Efforts to Address Transparency and Communication Challenges with Stakeholders

Most of the stakeholders we spoke with (nine out of 10) and four of the eight articles we reviewed discussed challenges related to transparency and communication from the agency. Specifically, stakeholders discussed the lack of transparency about the recall classification process, and some stakeholders said FDA’s communication can be inconsistent. For example:

Recall classification process. Stakeholders from two trade associations and a provider organization said that FDA does not currently share information about the factors that led to FDA’s classification decision, calling FDA’s recall classification process a vacuum. They said that having more insight into FDA’s classification process, including having more information about what FDA considers a high-risk problem (and therefore a likely class I recall), would allow manufacturers to better understand from FDA’s perspective what may happen to a patient if the device was used and their options for addressing it. According to FDA officials, while FDA does not provide specific documentation on the classification, the agency is available to speak to manufacturers and answer questions they may have about FDA’s classification decision and rationale behind the decision.

Inconsistent communication. A trade association stakeholder also mentioned that FDA tends to communicate with them at the early stages of the recall process, including when initiating and classifying the recall. However, communication and updates tend to wane in the end stages of a recall, specifically during the recall termination stage. As mentioned above, due to resource limitations, FDA OII officials have stated that they prioritize the beginning stages of the recall process.

Further, four selected articles we reviewed also identified communication challenges in the recall process. These challenges were related to making the public aware of the recall and the importance of updating recall information through the process. For example, one article described the challenges manufacturers and FDA face in contacting consumers affected by medical device recalls, including recall letters being sent to the wrong person. Another article described the need for the manufacturer and FDA to update recall information when new information related to the risk of using the device becomes available. To illustrate, the article described a pacemaker recall, and though device failures increased after the recall was initiated, this information was not communicated directly to consumers. This left users, such as providers and patients, unaware of the increased risk in using the device, which authors of the article believe negatively affected patient outcomes.[48]

FDA officials told us it has efforts intended to help address transparency and communication challenges generally.

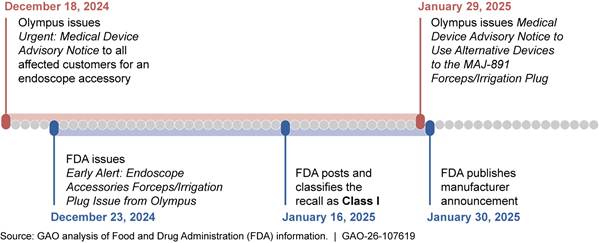

· In November 2024, FDA launched a pilot program aimed at communicating earlier to minimize the time between the FDA’s initial awareness and public notification of potentially high-risk medical device recalls. These “early alerts” are for potentially high-risk device removals or corrections in select medical specialty areas, including cardiovascular devices, which accounted for about one-quarter of all class I device recalls across fiscal years 2020 through 2024. According to FDA officials, this will lead to earlier communication to the public. We have noted multiple examples of these early alerts since FDA began its pilot. In the example below, FDA notified the public about the issue 3 business days after the manufacturer initiated a recall, rather than waiting until the recall was classified. (See figure 10.)

· In 2022, FDA implemented a public enforcement report subscription that allows users of any kind (e.g., the public, manufacturers, advocacy groups) to receive targeted updates on recalls based on key word searches, according to officials. Through this subscription, users can choose to be notified of recalls for specific device categories, such as “CPAP”, device manufacturer, or the reason for a recall. Enforcement reports include specific information about each recall, including initiation and classification dates, links to any available press releases, and model number(s) of affected devices, among other things.

· In June 2022, FDA proposed a 2-year study on risk communication for medical device recalls, which plans to inform FDA on the best practices and evidence-based approaches for communicating recalls to patients and consumers, among other objectives. Thus far, FDA has conducted focus groups, a literature review, and a summary of selected recalls, including attributes of FDA and manufacturer communications.[49] The agency incorporated focus group findings into recall summary template revisions, and it plans to conduct interviews for feedback. Afterward, it will analyze the findings and produce an internal report.

· FDA continuously creates and updates templates and guidance for manufacturers to use to ensure language is clear and consistent, according to FDA officials. FDA’s website contains a webpage that includes several recall resources, including model communication documentation. For example, FDA details a recall notification letter template for manufacturers to use, including elements that are recommended. Examples of such elements include marking the letter “URGENT” for class I and class II recalls, sections on the purpose of the letter, the reason for the voluntary recall, and actions to be taken by the customer/user. The actions section includes elements such as recommended treatment or actions to minimize risks of illness or injury, as well as alternative products that can be used, if applicable.

FDA Has Not Assessed Whether It Needs Authority Over a Manufacturer-Initiated Recall Strategy

As noted earlier, FDA officials said that the agency does not have the legal authority to require manufacturers to adopt the agency’s recommended changes to recall strategies for manufacturer-initiated recalls. According to officials, it can be challenging when manufacturers do not do so. According to some stakeholders, this can cause unnecessary confusion, and according to FDA officials, it can create an inefficient back and forth between FDA and the manufacturer regarding potential changes to a recall strategy. However, FDA has not conducted an assessment to determine what additional authorities may be needed to address these challenges and inefficiencies, according to FDA officials.

FDA has some current tools to address potential disagreement between the agency and the manufacturer. For example, FDA shared a case where the agency believed a press notification to the general public was warranted given the risk of the recall, but the manufacturer did not want to make such an announcement. Officials told us in these cases, FDA may issue its own public safety communication. However, some stakeholders noted that this can lead to confusion about device safety, severity of the recall, or what corrective action should be taken if FDA’s communication differs from that of the manufacturer.

FDA officials also told us there were instances when the agency wanted a manufacturer to conduct additional outreach to patients, but the manufacturer believed communicating with the providers about the recalled device was sufficient. In these cases, FDA officials said they encouraged manufacturers to communicate to the patient level as well. Officials told us that they would like the ability to require manufacturers to tailor their communications to different audiences—for example, to hospitals, providers, patients, or caregivers. Further, FDA officials shared another example when the agency believed that a device removal was a more appropriate recall action than a manufacturer’s proposal to modify instructions for a device. In this case, after discussions with the manufacturer via email and multiple teleconferences, the manufacturer agreed to remove the device.

According to one of our elements of effective oversight—enforcement authority—a regulatory organization, such as FDA, should have clear and sufficient authority to ensure the entities (in this instance, the device manufacturers) it regulates achieve compliance with requirements. FDA could use its mandatory recall authority and change the recall from manufacturer-initiated to mandatory, thereby giving FDA authority over the strategy. However, agency officials told us that using that authority would require them to follow the time- and resource-intensive multistep process that was described earlier in this report. FDA officials told us they have not assessed whether they need additional authorities, including how any potential new authorities would be implemented, over a manufacturer-initiated recall strategy. FDA officials also stated that no request has been submitted to Congress for additional authorities that would allow the agency to mandate changes to manufacturers’ recall strategies for manufacturer-initiated recalls.

FDA officials also said any additional authority would require resource considerations. Officials noted that having additional authorities for recall strategies would be inextricably linked to resources, because without sufficient resources, they may not be able to use additional authorities.

In some instances, resources could be reduced with additional authorities, according to officials. For example, FDA officials believe that having the authority to require manufacturers to issue easier-to-understand recall communications would reduce FDA’s review time of manufacturers’ recall strategies. It could also help eliminate the lengthy back and forth with the manufacturer in some cases, officials said. By working with FDA to assess if the agency would benefit from additional legislative authority over manufacturer-initiated recall strategies, including if such authority would help streamline operations and reduce inefficiencies, and then seeking such authority, if necessary, HHS could be better positioned to ensure that FDA can meet its goal of removing unsafe medical devices from the market.

Conclusions

Effectively managing and overseeing recalls of medical devices through all phases is vitally important to public health. FDA has taken steps to improve the recall process, but the agency continues to have resource and other challenges that keep the oversight of medical products, including devices, on GAO’s high-risk list. HHS is undergoing reforms that have the potential to affect FDA. As HHS undergoes its restructuring, it could benefit from working with FDA to conduct strategic workforce planning for medical device recalls to ensure alignment with HHS workforce priorities. Workforce planning in coordination with HHS could also help ensure that FDA has sufficient workforce capacity now and in the future, including the appropriate skills, to effectively process and oversee recalls, including meeting agency-set time frames, as well as conducting required routine inspections. This would help HHS keep unsafe devices from continued use.

HHS would also benefit from working with FDA during the restructuring to assess if FDA needs additional legislative authority to require manufacturers to implement agency recommendations for manufacturer-initiated recall strategies. Assessing the benefit of such authority could help HHS determine whether it would eliminate the inefficiency resulting from the back and forth with manufacturers about their recall strategies. If such authority is determined to be beneficial, seeking it is a particularly important sequential step in light of the agency’s current workforce limitations and future workforce considerations.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to the Secretary of HHS. Specifically:

As HHS undergoes its restructuring efforts, the Secretary should work with FDA to conduct strategic workforce planning to determine the staffing resources, skills, and capacity that FDA needs to effectively process and oversee medical device recalls—including being able to conduct recall audit checks and terminate recalls within agency goals—and develop strategies for addressing any identified workforce gaps. (Recommendation 1)

As a part of its restructuring efforts, HHS should work with FDA to assess if the agency would benefit from having additional legislative authority that would allow it to require manufacturers to implement agency recommendations for manufacturer-initiated recall strategies. HHS should seek additional authority, if needed. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its written response, reproduced in appendix II, HHS concurred with our first recommendation to work with FDA to conduct strategic workforce planning and address any identified gaps to effectively process and oversee medical device recalls. Regarding the second recommendation to assess, and seek if necessary, additional authority related to manufacturer-initiated recalls, HHS stated that it would take it under consideration as part of its restructuring efforts. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Mary Denigan-Macauley

Director, Health Care

Stakeholder Selection for Interviews About Challenges in the Recall Process

To obtain stakeholder perspectives on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) medical device recall process, including challenges, we selected and interviewed 10 stakeholders to learn about their perspectives on FDA’s medical device recall process. Specifically, we asked them about:

· their perspectives on what aspects of the recall process are working well,

· any challenges they are aware of or encounter in the recall process, and

· any changes they would recommend to the recall process to address the identified challenges.

We conducted a non-generalizable selection of stakeholders that met the following two criteria

1. The organization or individual has knowledge of (or expertise in) the medical device recall process in the U.S., and

2. Represents one of the following perspectives/categories listed below:

a. Medical device industry

b. Provider groups that use medical devices in their practice

c. Patients/consumers

d. Subject matter specialists on the medical device recall landscape, such as medical researchers or working groups within health systems

The stakeholders selected represented the following groups: trade associations (AdvaMed and the Medical Device Manufacturers Association); patients (the National Health Council); hospitals (the American Hospital Association’s Association for Health Care Resource and Materials Management); provider organizations (American College of Cardiology, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology); and subject matter specialists (a researcher and practicing physician that focuses on recalls, the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society, and the Recall Management Interest Group).

The views of our interviewees are not generalizable to the broader population.

Medical Device Recall Data

To identify the numbers and characteristics of voluntary medical device recalls, we obtained information on all recalls initiated and reported to FDA from October 1, 2020, through September 30, 2024. This information consisted of the most recent 5-year period of available data at the time we did our work. The source of this information was FDA’s Recall Enterprise System (RES), the agency’s central repository of recall information. FDA provided key information on each recall, including FDA’s recall event number; the status of the recall at the time FDA provided us with this information (e.g., ongoing or terminated); the reason for the recall; the specific device being recalled; the recall classification level assigned based on FDA’s assessment of risk; dates the recalls were initiated, classified, and terminated; and the medical specialty—area of use—for each device subject to recall (e.g., cardiovascular or orthopedic). We then used this information to determine, among other things, the number of recalls initiated per fiscal year; the number of recalls by recall classification levels; the average number of business days (i.e., excluding weekends and federal holidays) from initiation to termination for recalls that were terminated; and the number and percentage of recalls by medical specialty of the device being recalled.

To assess the reliability of the information from RES, we reviewed FDA’s user guide for the system and interviewed officials responsible for entering and reviewing the data. We also conducted data checks (e.g., number of values missing in a given field, ranges of values). We identified those observations with unique recall event numbers, and we excluded observations that were not medical devices and/or did not have a device classification (class I, class II, or class III).[50] Lastly, we excluded recalls where the classification date, completion date, or termination date were earlier than the initiation date, resulting in 3,934 unique recalls that were included for analyses. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

Evaluation of the Applicability of GAO’s Key Elements of Effective Oversight

This section describes the steps we took to confirm the applicability of five elements of effective oversight that we used to assess FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls. We have used these key elements in the past for assessing the effectiveness of oversight in other areas where low probability adverse events can have significant and far-reaching effects.[51] These elements are as follows:

1. Independence: The organization conducting oversight should be structurally distinct and separate from the entities it oversees.

2. Ability to perform reviews: The organization should have the access and working knowledge necessary to review compliance with requirements.

3. Technical expertise: The organization should have sufficient staff with the expertise to perform sound safety and security assessments.

4. Transparency: The organization should provide access to key information, as applicable, to those most affected by operations.

5. Enforcement authority: The organization should have clear and sufficient authority to require that entities achieve compliance with requirements.

We took several steps to confirm the applicability of these elements for our examination of FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls. First, we selected stakeholders with relevant knowledge and expertise in regulatory bodies. We selected organizations based on a number of factors, including whether the organization has knowledge or expertise in medical device recalls, the safety of medical devices, or the oversight of product recalls or product safety more broadly. We also selected organizations to represent various perspectives, including:

1. International bodies involved in device regulation;

2. U.S. federal government agency, other than FDA, that regulates products;

3. U.S. medical device industry;

4. U.S. patients or consumers; and

5. U.S.-based non-governmental organization that is involved in the regulation of products or devices.

Based on these criteria, we selected and discussed the applicability of the elements with officials and representatives from Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration, Health Canada, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, AdvaMed, the Medical Device Manufacturers Association, the National Health Council, and the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society. We also discussed the applicability of the criteria with officials from the FDA within the Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII) and Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). The officials, representatives, and subject matter specialists generally agreed that the five elements were appropriate elements to evaluate FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls.

Literature Review

We identified and analyzed eight studies (peer-reviewed literature) and reports (governmental or other publications) that we determined were relevant to our work on FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls. Specifically, we identified these studies and reports by searching research databases for relevant peer-reviewed studies. We then analyzed each study or report to identify common themes and illustrative examples on topics related to challenges in FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls.

Identifying studies by searching research databases. In order to inform our research objective on the challenges that affect FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls, and FDA’s efforts to address the challenges, we searched research databases for peer-reviewed literature using the search terms: medical device recall and Food and Drug Administration OR FDA.

We searched various research databases, such as Coronavirus Research Database, Criminology Collection, Education Database, ERIC, Global Newsstream, Health & Medical Collection, Policy Final Index, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, PTSDPubs, Publicly Available Content Database, ProQuest research Library, SciTech Premium Collection, Scopus and Sociology Collection.

Searching these databases identified 99 publications from January 2014 through October 24, 2024. We screened the abstracts of the 99 publications, for their relevance to our objective, and identified 41 for full-text review. We reviewed all 41 peer-reviewed studies and reports that discussed the FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls and included at least one of the following criteria:

1. challenges in the recall process;

2. challenges in FDA’s oversight of the recall process; or

3. proposed efforts or recommendations to address challenges in the recall process.

Twenty studies and reports were selected for inclusion in our analysis.

Analyzing studies and reports. We analyzed the 20 studies and reports, described above, for information on challenges to FDA’s oversight of medical device recalls and recommendations to address these challenges. During our review process, we noted a number of studies were not as relevant to our findings due to the age of the underlying data or information used or exclusively focusing on the premarket process, rather than medical device recalls. Therefore, we narrowed our selection to articles published in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, and we excluded articles that focused exclusively on the premarket process. Further, one publication included information outside our specified time frame, citing evidence that was decades old, was also excluded. We then analyzed the eight remaining studies and reports to identify common themes and illustrative examples on the topics of challenges in the recall process, challenges in FDA’s oversight of the recall process, and proposed efforts or recommendations to address challenges in the recall process.

In extracting information from these studies, we took into account any methodological limitations of those studies that could affect the reliability of that information.

The eight studies included were:

DeRuyter, Matthew T., LeiLani N. Mansy, John W. Krumme, An-Lin Cheng, Jonathan R. Dubin, and Akin Cil. "Risk of Recall for Total Joint Arthroplasty Devices Over 10 Years," The Journal of Arthroplasty vol. 38, no. 8 (2023): 1444–1448, doi.org:10.1016/j.arth.2023.01.068.

Liebel, Teresita C., Tara Daugherty, Alexandra Kirsch, Sharifah A. Omar, and Tara Feuerstein. "Analysis: Using the FDA MAUDE and Medical Device Recall Databases to Design Better Devices," Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology vol. 54, no. 3 (2020): 178–188, doi.org:10.2345/0899-8205-54.3.178.

Mooghali, Maryam, Joseph S. Ross, Kushal T. Kadakia, and Sanket S. Dhruva. "Availability of Unique Device Identifiers for Class I Medical Device Recalls from 2018 to 2022," JAMA Internal Medicine vol. 183, no. 7 (2023a): 735–737, doi.org:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0727.

Morgenthaler, Timothy I., Emily A. Linginfelter, Peter C. Gay, et al. "Rapid Response to Medical Device Recalls: An Organized Patient-Centered Team Effort," Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine vol. 18, no. 2 (2022): 663–667, doi.org:10.5664/jcsm.9748.

See, Claudia, Maryam Mooghali, Sanket S. Dhruva, Joseph S. Ross, Harlan M. Krumholz, and Kushal T. Kadakia. "Class I Recalls of Cardiovascular Devices between 2013 and 2022 : A Cross-Sectional Analysis," Annals of Internal Medicine (2024), doi.org:10.7326/ANNALS-24-00724.

Sengupta, Jay, Katelyn Storey, Susan Casey, et al. "Outcomes Before and After the Recall of a Heart Failure Pacemaker," JAMA Internal Medicine vol. 180, no. 2 (2020): 198–205, doi.org:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5171.

Tennant, Bethany L., Casey Langer Tesfaye, Melanie C. Chansky, et al. "Communicating Medical Device Recalls: A Rapid Review of the Literature," Patient Education and Counseling 123 (2024): 108244, doi.org:10.1016/j.pec.2024.108244.

Wang, Yang, Kai Xu, Yuchen Wang, et al. "Investigation and Analysis of Four Countries' Recalls of Osteosynthesis Implants and Joint Replacement Implants from 2011 to 2021," Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research vol. 17, no. 1 (2022): 443, doi.org:10.1186/s13018-022-03332-w.

GAO Contact

Mary Denigan-Macauley, Director, Health Care, DeniganMacauleyM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Jennel Lockley (Assistant Director), Amy Andresen (Analyst in Charge), John Lalomio, Amy Leone, and Kristeen McLain made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Sam Amrhein, Sonia Chakrabarty, Raghavendra Chegireddy, Joycelyn Cudjoe, Leia Dickerson, Cynthia Khan, and Ethiene Salgado-Rodriguez.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See 21 U.S.C. § 321(h).