EXCESS DEFENSE ARTICLES

DOD Needs to Better Assess the Program

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: James A. Reynolds at reynoldsj@gao.gov

What GAO Found

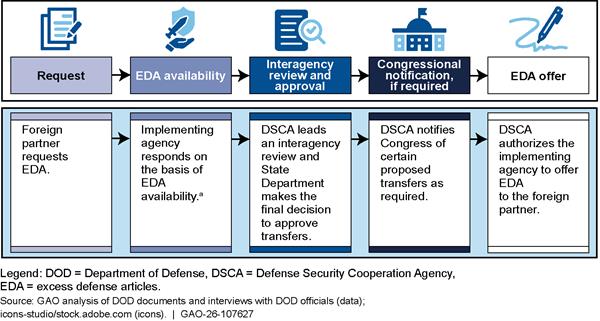

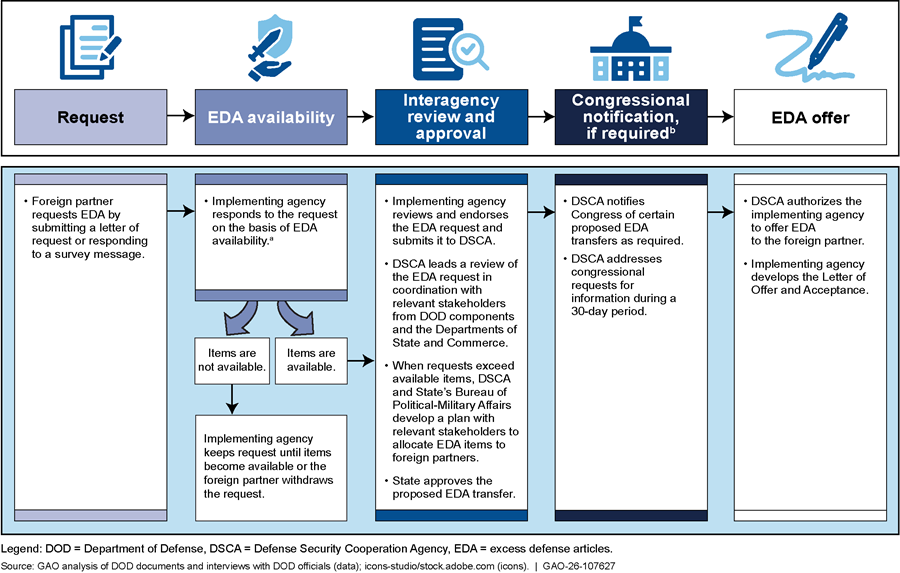

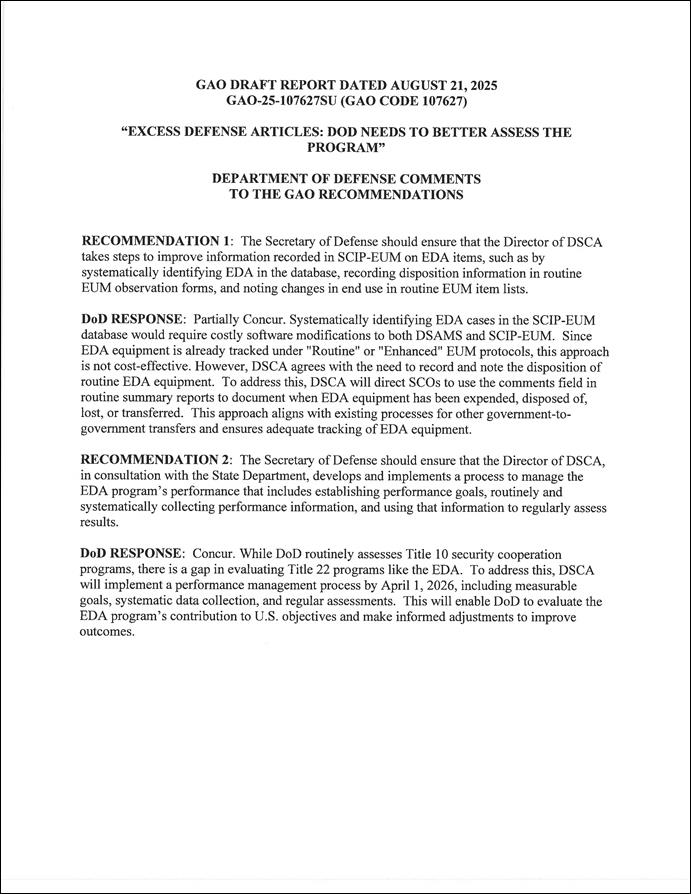

The Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program has a phased approval process. The Department of Defense (DOD) reviews foreign partners’ EDA requests and coordinates with the Departments of Commerce and State. During the process, agency officials consider the proposed transfer’s effect on industry, foreign partner resources, and security cooperation priorities, among other factors.

aImplementing agencies are the military departments and Defense Logistics Agency Disposition Services.

DOD monitors EDA after transfer under its end-use monitoring program. Nearly all EDA are subject to the program’s routine end-use monitoring, which requires DOD officials to observe an item or group of items for each foreign partner at least quarterly. GAO found that DOD generally conducted the quarterly routine checks as required for selected foreign partners. However, DOD does not systematically track key information on EDA after transfer to foreign partners. Specifically, DOD’s end-use monitoring database does not identify items as EDA or have disposition data (i.e., an item’s status, such as demilitarized or expended in combat versus in active use) for routine items. Systematically tracking EDA would provide DOD better information on these items. Such information would allow DOD to make better-informed recommendations on future EDA transfers, because these are based in part on foreign partner abilities to support items.

DOD has not taken key steps to assess the EDA program’s performance. It has not developed performance goals to measure progress toward strategic objectives, such as building foreign partner capabilities. DOD has also not systematically collected performance information to assess the program’s results. For example, DOD officials said foreign partner feedback would be a good source of such information, but they do not routinely collect it. By taking steps to systematically assess the EDA program’s performance, DOD would better determine the extent to which the program helps achieve strategic objectives.

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. government transfers defense articles the armed forces no longer need—EDA—to foreign partners. By providing low-cost access to U.S. military equipment, the EDA program aims to support U.S. allies and partners and further national security objectives.

The House Appropriations Committee Report 118-121 includes a provision for GAO to review the EDA program. GAO’s report examines (1) how DOD administers the program, (2) the extent to which DOD monitors and tracks EDA transferred to foreign partners, and (3) the extent to which DOD assesses the program’s performance.

GAO reviewed relevant DOD policy and guidance. GAO analyzed DOD data on end-use monitoring for five foreign partners selected on the basis of such criteria as the value of EDA approved in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. GAO also interviewed officials from DOD, including from the military departments, security cooperation organizations, and geographic combatant commands; State; and Commerce.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to DOD to (1) improve information recorded on EDA in its database and (2) develop and implement a process to manage the program’s performance. DOD partially concurred with the first recommendation and concurred with the second. Regarding the partial concurrence, DOD stated that systematically identifying EDA in its database would require software modifications that are not cost-effective because EDA are tracked under end-use monitoring protocols. GAO maintains that DOD can take additional cost-effective steps to improve the information on EDA, such as by using the database’s existing features to identify items as EDA.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DLA |

Defense Logistics Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DSCA |

Defense Security Cooperation Agency |

|

EDA |

excess defense articles |

|

EUM |

end-use monitoring |

|

FMS |

foreign military sales |

|

NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

|

SCIP |

Security Cooperation Information Portal |

|

SCO |

security cooperation organization |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 16, 2025

Congressional Committees

Various challenges, including armed conflict and terrorism, undermine the security of the U.S. and its allies. The U.S. government uses security cooperation programs to build the capacity of foreign partners to help address these challenges and further U.S. national security and foreign policy objectives.[1] One such program transfers defense articles no longer needed by the U.S. armed forces—excess defense articles (EDA)—to foreign governments or international organizations at low or no cost. By providing cost-effective access to U.S. military equipment, the EDA program aims to help build U.S. allies’ and partners’ defense capabilities, strengthen coalitions, and enhance interoperability. Department of Defense (DOD) officials said the program also provides military departments a way to dispose of equipment that would otherwise have to be stored at a cost or destroyed. Since 2019, the U.S. has delivered EDA worth more than $900 million to foreign partners worldwide, according to a DOD document.

House Report 118-121 includes a provision for us to report on the EDA program.[2] We examine (1) how DOD administers the EDA program, including identifying available defense articles and recipients and integrating EDA with security cooperation priorities, as appropriate; (2) the extent to which DOD monitors and tracks defense articles transferred to foreign partners through the EDA program; and (3) the extent to which DOD assesses the EDA program’s performance.

To describe how DOD administers the EDA program, we reviewed DOD policies and guidance, such as the Security Assistance Management Manual. We interviewed DOD officials with roles related to the EDA program, including from the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), military departments, security cooperation organizations (SCO) at U.S. embassies, and the geographic combatant commands.[3] We also spoke with officials from the Departments of State and Commerce. We reviewed data reported in DOD’s Security Cooperation Information Portal (SCIP) for proposed EDA transfers approved in fiscal years 2020 through 2024.[4] To determine the reliability of these data, we conducted several validity checks and interviewed DOD officials. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

To assess the extent to which DOD monitors and tracks defense articles transferred through the EDA program, including their disposition (i.e., an item’s status, such as demilitarized or expended in combat), we reviewed applicable guidance documents that outline end-use monitoring (EUM) requirements. We determined the internal control principle related to quality information was significant to this objective.[5] We analyzed DOD data on EUM and examined the extent to which SCOs completed the relevant EUM requirements for a nongeneralizable sample of five foreign partners—Colombia, Greece, Israel, Morocco, and the Philippines. These five foreign partners were among the top recipients of EDA in their respective geographic combatant commands’ areas of responsibility.[6] We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for reporting the extent to which SCOs completed relevant EUM requirements in the five foreign partners after reviewing documentation about the data system and interviewing DOD officials, among other steps.

To assess the extent to which DOD assesses the EDA program’s performance, we reviewed DOD documentation and interviewed DOD officials about relevant efforts. We then compared the information provided to key performance management practices identified in our prior work.[7] For more information about our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DOD’s Disposal Process for Excess Property

The EDA program is one method for military departments to dispose of equipment they no longer need. Each military department determines whether its excess property can be made available for EDA transfers. Before making their excess property available to foreign partners, the military departments determine the equipment is not needed by other military departments, defense agencies, reserve components, or the National Guard, according to DOD guidance.

Each military department has its own processes for determining its excess property. For example, the

· Air Force determines its excess aircraft through strike boards—decision-making forums held at least annually—where it plans divestments;[8]

· Army has a divestiture working group that meets on a semi-annual basis to determine excess major end items—a category of equipment that includes such items as tactical vehicles;[9] and

· Navy determines its excess ships through annual ship disposition reviews where it plans vessels’ retirements from the active fleet.[10]

A military department may choose several ways besides the EDA program to dispose of the equipment it has designated as excess.[11] For example, it may dispose of equipment directly by reusing it (e.g., for spare parts) or transferring it to other DOD components or federal agencies. It may sell the equipment through private-sector contractors to the public or destroy the material. It may also transfer the equipment to the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) Disposition Services, where it is disposed of through a multi-stage process during which the equipment is screened, and, if eligible, reused, transferred, or sold.

Overview of the EDA Program

The EDA program is a security assistance program, a subset of security cooperation.[12] It transfers defense articles no longer needed—and that have been declared excess—by DOD and the U.S. Coast Guard to foreign partners.[13] EDA transfers must be drawn from existing DOD stocks and must not adversely affect U.S. military readiness or the U.S. national technology and industrial base.

EDA is transferred at a reduced cost (through sales) under the Arms Export Control Act, as amended, or at no cost (through grants) under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended.[14]

· Sales. For sales, the price of EDA ranges from 5 to 50 percent of the original acquisition value depending on an item’s condition and age.[15] Foreign partners can purchase EDA if they are eligible to purchase defense articles and services through foreign military sales (FMS), the U.S. government’s program for transferring defense articles, services, and training to foreign governments and international organizations.

· Grants. For grants, the total current value of all EDA transfers cannot exceed $500 million annually.[16] For a foreign partner to be eligible for grant EDA, DOD must notify Congress, with State concurrence, and justify the partner’s eligibility for the fiscal year in which the transfer is proposed. The foreign partner must also enter into an agreement that outlines blanket end-use, security, and retransfer assurances, known as a Section 505 agreement.[17]

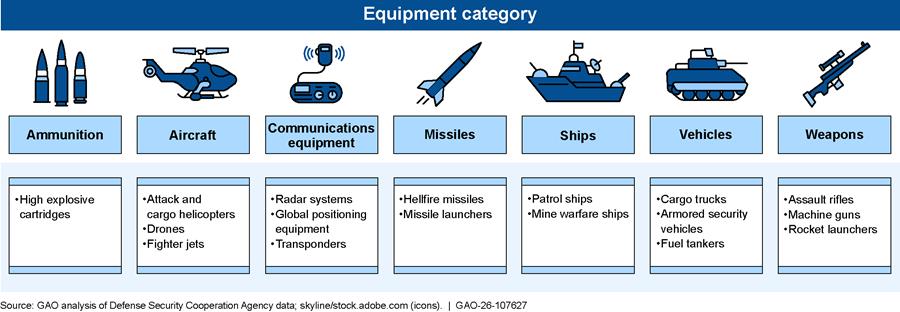

As shown in figure 1, EDA transferred to foreign partners include vessels, vehicles, and aircraft, among other items, such as ammunition, clothing, radios, and spare parts.

Figure 1: Examples of Excess Defense Articles Transferred to Foreign Partners: Vessels, Vehicles, and Aircraft

EDA is transferred on an “as is, where is” basis, meaning the recipient generally pays for packing, crating, handling, and transportation costs, as well as any refurbishment and follow-on support. Foreign partners may purchase these services from the U.S. through the FMS program.[18]

Agency Roles

Several agencies play a role in the EDA program, as shown in table 1. State’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs oversees the program and approves EDA transfers.[19] Within DOD, DSCA administers the EDA program and the military departments and DLA Disposition Services—known as implementing agencies—execute the program. Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security provides input on EDA transfers’ industry impact.

|

Agency |

|

Component |

Roles |

|

|

Department of State |

Bureau of Political-Military Affairs |

Oversees the program, including · determining foreign partner eligibility, · reviewing and approving transfer requests, and · developing plans to allocate EDA to foreign partners when requests exceed available items. |

||

|

Department of Defense (DOD) |

Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) |

Administers the program, including · coordinating interagency review of transfer requests, · notifying Congress of proposed transfers as required, · developing plans to allocate EDA to foreign partners when requests exceed available items, and · authorizing implementing agencies to offer EDA to foreign partners. Provides policy guidance on the program. |

||

|

Military departmentsa (Air Force, Army, Navy) |

Identify and designate defense articles as excess. Prepare survey messages to advise partners of potential EDA. Respond to foreign partners’ requests. Help develop DOD’s position on which foreign partners should receive EDA when requests exceed available items. Submit transfer requests to DSCA for review. Oversee and execute transfers, including · preparing the Letter of Offer and Acceptance and · coordinating foreign partners’ inspections of EDA. |

|||

|

Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) Disposition Servicesa |

Manages the disposal of excess DOD property. Submits transfer requests to DSCA for review. Oversees and executes transfers, including preparing the Letter of Offer and Acceptance. |

|||

|

|

Combatant commands |

Review and endorse transfer requests as needed. Help develop DOD’s position on which foreign partners should receive EDA when requests exceed available items. |

||

|

|

Security cooperation organizations |

Review and provide supporting justification for foreign partners’ requests. Assess foreign partner capabilities to fund follow-on operational, maintenance, and training for EDA. |

||

|

Department of Commerce |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

Reviews proposed transfers to determine whether they will adversely affect industry. |

||

Source: GAO analysis of DOD and State documents and interviews with DOD and State officials. | GAO‑26‑107627

Note: EDA are DOD- and U.S. Coast Guard–owned defense articles that are no longer needed and declared excess.

aThe military departments and DLA Disposition Services are known as implementing agencies and execute EDA transfers. The Navy is the implementing agency for Coast Guard items for the EDA program.

End-Use Monitoring of EDA

In 1996, Congress amended the Arms Export Control Act to require the President to establish a program for monitoring the end use of defense articles and defense services sold, leased, or exported under that act or the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961.[20] The law requires that, to the extent practicable, the program be designed to provide reasonable assurance that recipients are complying with restrictions imposed by the U.S. government on the use, transfers, and security of defense articles and defense services, and that recipients use such articles and services for the purposes for which they are provided.

In response, DOD established the Golden Sentry program to monitor the end use of defense articles and defense services transferred to foreign partners through FMS, including EDA. Golden Sentry is designed to verify that defense articles are used in accordance with the terms and conditions of transfer agreements or other applicable agreements, according to DSCA policy. In 2022, we recommended DOD and State evaluate whether the Golden Sentry program is providing reasonable assurance that defense articles are being used for their intended purpose.[21] This recommendation is not yet implemented.[22]

Monitoring the end use of U.S.-origin defense articles and services is a joint responsibility of the foreign partners and the U.S. government, including the military departments, combatant commands, and SCOs, according to DSCA policy. DSCA administers the program, under which SCOs conduct two levels of EUM: routine and enhanced EUM.

· Routine EUM. DOD requires at least routine EUM for all defense articles and services transferred through government-to-government programs. SCO officials conduct routine EUM in conjunction with other security cooperation functions using any readily available source of information. SCOs are required to conduct at least one routine EUM check per quarter for each foreign partner by observing an item or group of items subject to routine EUM.

· Enhanced EUM. DOD requires enhanced EUM for specifically designated sensitive items, such as certain missiles and night vision devices.[23] There were 19 types of items subject to enhanced EUM according to DSCA policy at the time of our review. In addition to an initial inventory by serial number for all items, enhanced EUM requires SCO officials to annually assess the physical security of the storage facilities and visually inventory 100 percent of all in-country enhanced EUM items to verify compliance with the conditions of transfer agreements.

SCOs are required to report all potential end-use violations of equipment monitored under Golden Sentry to DSCA, State, and the combatant commands. State investigates alleged end-use violations and determines whether to report them to Congress.[24]

Further, the U.S. government requires recipients of U.S.-origin defense articles to obtain written consent from State prior to transfer, disposal, or other changes of end use of its U.S.-origin defense articles, including any destination not previously authorized in the original acquisition. State reviews and approves such requests through its third-party transfer process.

SCOs record EUM information and documents related to end-use changes in SCIP’s EUM database that DOD uses to track government-to-government transfers of defense articles.

DOD Administers the EDA Program Via a Phased Approval Process Weighing Security Cooperation Priorities and Other Factors

As shown in figure 2, DOD has a five-phase process to review and obtain approval for proposed EDA transfers in coordination with State and Commerce. After approval, DOD executes EDA transfers by grant and sale following the process used for FMS.

aImplementing agencies are the military departments (Army, Air Force, and Navy) and Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) Disposition Services. The Navy is the implementing agency for Coast Guard items for the EDA program. The phases depicted do not always apply to EDA transfers executed by DLA Disposition Services.

bCongressional notification is required for proposed EDA transfers that contain significant military equipment or with an original acquisition cost of $7 million or more.

Phase 1: Foreign Partners Request EDA in Several Ways

The EDA program’s approval process begins when the foreign partner requests EDA in the following ways:

· Survey message response. Foreign partners may indicate their interest in acquiring EDA by responding to a survey message—a message periodically issued by the military departments informing partners of excess equipment available for potential transfer. Survey message responses should include the SCO’s justification for the transfer, including an assessment of the foreign partner’s capabilities to fund follow-on operational, maintenance, and training requirements, according to DSCA policy. Air Force and Navy officials said they use survey messages to solicit foreign partner interest in items, such as aircraft and vessels. Army officials said they had used such messages for excess equipment at Army depots. However, these officials said that, in recent years, they have aimed to facilitate EDA transfers before excess equipment is transferred to Army depots and have not issued survey messages. They have done so to keep pace with the Army’s approach for divesting excess equipment.[25]

· Letter of request. Foreign partners may also submit a letter of request for EDA to the implementing agency, which DOD officials said signals a partner’s formal interest in acquiring EDA items. DSCA policy states that foreign partners are encouraged to work with SCOs to prepare such requests to ensure they include details related to the defense article requested, such as the item’s desired condition and whether the partner has purchased the item before. DOD and State officials said the requests may be for a capability or specific item. DOD officials said foreign partners may inquire about EDA availability before submitting a letter of request.

· DLA Disposition Services’ web-based application. Finally, foreign partners may request items directly from DLA Disposition Services’ web-based application that displays available items in its inventory.[26] DLA Disposition Services officials said their inventory includes all excess property received from the military departments, ranging from nuts and bolts to vehicles. Specifically, foreign partners can request items during the first stage of DOD’s disposal screening cycle, where usable property may be reused within DOD or provided to special programs, such as the EDA program.[27]

A foreign partner may request EDA for various reasons. For example, DSCA officials said Greece has used EDA to modernize its armed forces, whereas Israel has primarily used EDA to source supply parts to sustain its capabilities. State officials said that, while some foreign partners prefer the EDA program because of their limited resources, others do not use the program because they prefer to purchase new equipment.

Phase 2: Implementing Agencies Determine Whether They Can Support Requests on the Basis of EDA Availability

After receiving the foreign partner’s request, the implementing agency—a military department or the DLA Disposition Services—decides whether they can support it on the basis of EDA availability. Officials outside of the military department components that execute security cooperation programs determine whether excess equipment is available for proposed EDA transfers, according to DSCA officials. For example, Army Headquarters G-8—the Army’s lead for programming resources—validates proposed EDA transfers to ensure the equipment is excess and no other U.S. government agency needs it, according to Army officials.

DOD officials said implementing agency officials participate in their military departments’ respective disposal processes to identify what items may become excess and potentially available for EDA transfers in the future. For example, Navy officials said they identify potential EDA availability using 5-year decommissioning plans and track foreign partner interest in an “EDA holistic plan.” These officials told us they use the EDA holistic plan as a starting point for transfers when items become available.

The available supply of EDA varies by the three military departments and year. DOD officials said foreign partner requests generally exceed the available supply of Navy and Air Force items, such as vessels and aircraft, whereas the Army has generally had enough supply of some types of items to meet foreign partner requests in recent years. For example, a DSCA official said the Army has been modernizing its vehicle fleet and has therefore been able to support multiple foreign partners’ requests for excess vehicles.

Further, EDA availability can change as the military departments evaluate their needs and future requirements. Military departments can—after determining excess equipment is available to foreign partners but prior to the transfer—decide to retain the equipment for training or as a source for spare parts, according to DSCA documents. For example, Army officials said they reclaimed trucks proposed for transfer because brigades needed them for spare parts. DOD officials told us military departments may also face production delays in replacing their capabilities, so equipment projected to become EDA may not be available when initially expected.

Moreover, DOD officials said transferring equipment under the Presidential Drawdown Authority has affected the supply of excess equipment and, therefore, the items available for potential EDA transfers.[28] Army officials told us that much of their excess equipment was transferred to Ukraine under this authority.[29] For example, SCO officials said heavy equipment transporters offered as EDA to a foreign partner had been put on hold to support other priorities in Ukraine.

If items are unavailable for EDA transfer, the implementing agency keeps the request on hand until the items become available or the foreign partner withdraws the request. If items are available, the implementing agency prepares the proposed transfer package for review.[30]

Phase 3: DSCA Leads Interagency Review, and State Decides Whether to Approve Proposed EDA Transfers

The third phase of the EDA program’s approval process has two parts. First, DSCA leads an interagency review that weighs various factors. Following this, State decides whether to approve the proposed EDA transfer.

DCSA-Led Interagency Review Weighs Security Cooperation Priorities Among Other Factors

The implementing agency endorses the EDA request by submitting the proposed EDA transfer package to DSCA for review. The package includes the foreign partner’s letter of request, as well as the following:

· EDA worksheet, which includes the implementing agency’s justification for the transfer. The justification may address how the transfer supports U.S. interests, the foreign partner or region, and allied operations as applicable, among other information. For example, the Air Force stated how a proposed transfer will help ensure the foreign partner supports North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) air component requirements in its justification. DOD and State officials said that, in addition to in-country officials, implementing agencies are well-positioned to comment on whether the foreign partner can effectively use and support EDA items given their technical expertise and foreign partner engagement.

· Country team assessment, if required.[31] DSCA policy states this assessment presents the coordinated position of senior U.S. embassy leadership in support of a proposed transfer and key information to explain it, such as how the (1) partner intends to use the article and (2) article contributes to both U.S. and partner defense goals.

· Combatant command endorsement, if the transfer introduces a new system or capability to the partner or region. DOD officials said this endorsement helps ensure the transfer supports the combatant command’s priorities and security cooperation goals.

After receiving the package, DSCA leads an interagency review of the proposed EDA transfer by coordinating with relevant DOD components, Commerce, and State. These entities review the package and weigh various factors, including the following:

· U.S. security cooperation priorities. DOD officials said they consider how proposed EDA transfers support U.S. security cooperation priorities in the country or region. For example, SCO officials in Greece said they consider how Greece’s EDA requests support NATO capabilities. As another example, SCO officials in Morocco said they consider how Morocco’s EDA requests support interoperability goals. Officials from six geographic combatant commands said they consider how proposed EDA transfers support their priorities and objectives. For example, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s endorsement for a proposed EDA transfer states how that transfer aligns with the command’s security cooperation plan and objectives for that foreign partner to improve its maritime security.

· Foreign partner resources. DOD and State officials said they consider whether foreign partners can pay the costs associated with the proposed EDA transfer. Since EDA is transferred on an “as is, where is” basis, foreign partners must generally pay the packing, crating, handling, and transportation costs, as well as any repairs or refurbishments. EDA is used equipment and often requires repairs and refurbishments, according to DOD officials. In addition, foreign partners may need to purchase spare parts, tools, manuals, training, and other support for the equipment, separately, if available.

· Foreign partner capabilities. DOD and State officials said they consider whether foreign partners can effectively operate, maintain, and sustain the equipment. DOD officials said foreign partners must have a clear plan for EDA, such as modernizing an existing capability. EDA transfers are most effective when they enable foreign partners to maintain an existing capability or acquire an interim capability until procuring a new system is possible, according to a DSCA document and State officials. As the U.S. transitions from a system, the resources foreign partners need to operate and maintain EDA items may no longer be produced (e.g., spare parts, tools, and other support items). Therefore, DOD guidance states officials should assess whether foreign partners have an existing infrastructure or can develop one to support EDA items. DOD officials also consider whether foreign partners have effectively used EDA items in the past.

· U.S. foreign policy objectives. DSCA officials said they rely on State to determine whether proposed EDA transfers support U.S. foreign policy objectives. State officials said they review such transfers in line with the U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, which guides how U.S. government agencies review and evaluate proposed arms transfers.[32] These officials told us they also consider the transfer’s consistency with other programs, the foreign partner’s needs, and U.S. foreign policy priorities. Moreover, priority for grant EDA is given to NATO allies and to major non-NATO allies on the southern and southeastern flank of NATO, to Taiwan, and to the Philippines.[33]

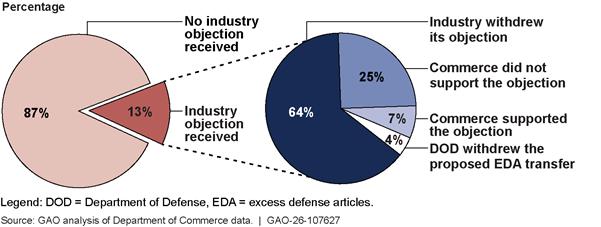

· Industry impact. By law, the President must determine that EDA transfers will not adversely affect the U.S. national technology and industrial base or reduce U.S. industry’s opportunities to sell new or used equipment to the foreign partners to which such articles are transferred. The Director of DSCA has been delegated the authority to make this determination.[34] DSCA sends each proposed transfer to Commerce for its review to ensure the transfer will not have an adverse industry impact. Commerce then solicits industry input. Commerce received industry objections for 13 percent of the proposed EDA transfers it reviewed in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, according to our analysis of Commerce data. Commerce ultimately concurred with nearly all transfers (99 percent) it reviewed during this period after taking steps to address industry objections. Our analysis of Commerce data indicates that, in most cases, industry withdrew its objections. Commerce officials said industry may withdraw objections for various reasons, such as learning of opportunities to offer refurbishment services for the EDA items. DSCA has not moved forward with a proposed transfer without Commerce’s concurrence, according to a DSCA official. See appendix II for more information on Commerce’s review.

The importance of these factors in the interagency review depends on the type of equipment proposed for transfer, specifically whether they are minor or major items, and their availability. According to DOD and State officials:

· Minor items, such as spare and component parts, are typically “first come, first served” when there is sufficient supply to meet foreign partner demand. For example, Air Force officials said they transfer spare parts and engines on such a basis because there is sufficient supply and the foreign partners requesting these items need them to successfully operate the U.S. equipment they already have.

· “Major items”—to include major end items, such as vessels and aircraft, and weapons systems—generally require greater review if multiple foreign partners are interested in acquiring the limited number of available EDA items, among other reasons.[35] In such cases, DOD and State develop a coordinated plan to allocate the limited available items among foreign partners.[36] Using the implementing agency’s recommendations as its starting point, DOD and State consider such criteria as regional balancing and combatant command priorities, according to DSCA policy. DOD officials told us some criteria may be more important than others depending on the equipment and foreign partners involved.

The DOD and State coordinated plan provides senior leaders with recommendations on allocating EDA items. DOD and State officials said senior leaders may revise the plan for reasons ranging from White House directives to specific bilateral considerations. For example, in 2020, senior leaders reviewing such a plan requested replacing one foreign partner with another in the proposed allocation of 13 excess vessels to help strengthen the specific partnership with the other partner and increase the likelihood that partner will buy equipment through FMS, according to a memorandum.

Moreover, DOD and State officials said EDA items that introduce new capabilities require greater consideration. There can be significant challenges in transferring EDA to help foreign partners develop a new capability over the long term, according to a DSCA document. For example, DSCA officials said foreign partners may not have the technical knowledge or experience to operate the EDA items. Therefore, the agency expects more information in the package about foreign partner capabilities and how such transfers support security cooperation priorities, according to a DSCA official.

State Decides Whether to Approve Proposed EDA Transfers

After the DSCA-led interagency review, State makes the final decision on whether to approve proposed EDA transfers. State’s decision-making role helps ensure that transfers support U.S. foreign policy and national security objectives. State has denied or paused proposed EDA transfers for foreign policy reasons, but doing so is not common according to State officials. For example, these officials said they paused a proposed transfer to a foreign partner because of its political environment but later approved it once conditions improved. State officials told us U.S. defense equipment transferred to foreign partners, including EDA, should further U.S. foreign policy objectives and be effectively operated and supported.

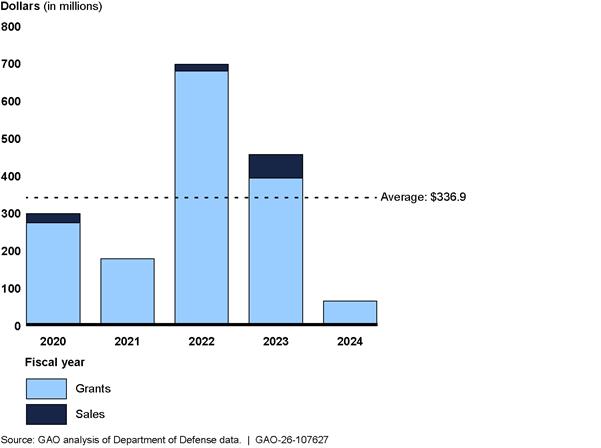

In fiscal years 2020 through 2024, State approved 209 proposed EDA transfers worth a total of $1.68 billion in current value, according to our analysis of DOD data. As shown in figure 3, State approved proposed transfers worth an average of $336.9 million annually in current value, with annual values ranging from $63 million in fiscal year 2024 to $695 million in fiscal year 2022.[37] The annual value of proposed transfers approved varies based on the excess equipment available for EDA transfers, according to DSCA officials. Grants represented about 94 percent of the total current value of proposed transfers approved in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, according to our analysis of DOD data.

Figure 3: Annual Value of Proposed Excess Defense Article (EDA) Transfers Authorized for Foreign Partners, Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: The data depicted represent the current value of proposed EDA transfers that the Department of State approved and Defense Security Cooperation Agency authorized the implementing agency to offer to the foreign partner. Foreign partners decide whether to accept the EDA offer and move forward with the proposed transfer.

Phase 4: DSCA Notifies Congress of Certain Proposed EDA Transfers

The fourth phase of the EDA program’s approval process is notifying Congress of certain proposed transfers. A 30–calendar day congressional notification is required for proposed EDA grants or sales that

· contain significant military equipment—defense articles identified on the U.S. Munitions List and for which special export controls are warranted because of the capacity of such articles for substantial military capability, such as attack helicopters and armored combat ground vehicles—or,[38]

· originally cost $7 million or more to acquire.[39]

DSCA prepares the notification, which according to its policy includes

· the purpose for which the article is being provided to the partner, including whether the article has been previously provided;

· the effect on U.S. military readiness;

· the effect on the U.S. national technology or industrial base and U.S. industry’s opportunities to sell new or used equipment to the partner;

· the current value and original acquisition value of the article; and

· an estimate of packing, crating, handling, and transportation funds needed for transfers, if required.

Congress reviews the notification and might request additional information, according to DSCA policy. DSCA officials said they do not transfer EDA until all congressional requests for additional information are favorably resolved, even if doing so takes longer than 30 days. Such requests are usually for more context on the proposed transfer, according to a DSCA official. If Congress does not object to the proposed transfer prior to the expiration of the 30-day period, it moves forward.

Phase 5: Implementing Agency Offers Proposed EDA Transfers to Foreign Partners

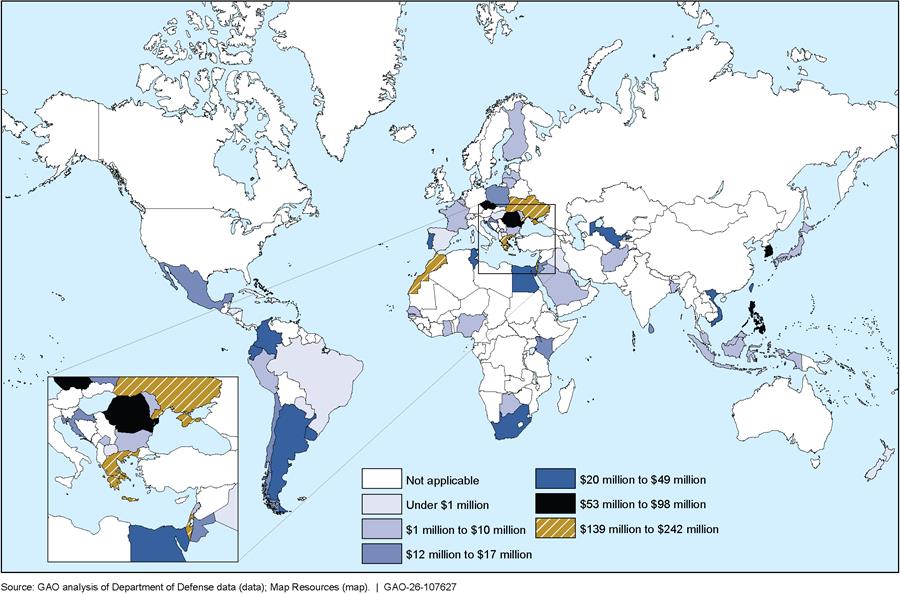

The fifth phase of the EDA program’s approval process is the offer. After obtaining State’s approval and notifying Congress (if required), DSCA authorizes the implementing agency to offer the EDA items to the foreign partner. Greece, Israel, and Morocco are the three foreign partners with the greatest value of EDA offers and represented 40 percent of the total current value of offers authorized in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, according to our analysis of DOD data. See figure 4 for foreign partners that received EDA offers during this period.

Figure 4: Total Value of Proposed Excess Defense Article (EDA) Transfers Authorized for Foreign Partners, Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: The data depicted represent the current value of proposed EDA transfers that the Department of State approved and Defense Security Cooperation Agency authorized the implementing agency to offer to the foreign partner. Foreign partners decide whether to accept the EDA offer and move forward with the proposed transfer. While the data depict proposed EDA transfers to individual North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members, they do not include a proposed EDA transfer, worth $50,000, authorized for NATO itself.

Our analysis of DOD data indicates that on average, it took about 6 months for a proposed EDA transfer to be authorized for offer to the foreign partner after the implementing agency submitted the proposed transfer package to DSCA for review (i.e., Phases 3-5). DSCA officials said transfers take longer than average to approve when there are industry objections or congressional questions, among other reasons.

The foreign partner then decides whether to accept the EDA offer. Foreign partners may decline the offer, deciding that they no longer want the equipment or that refurbishment costs are more than expected, among other reasons, according to DOD and State officials. Foreign partners may also decline EDA after assessing the equipment’s condition through a joint visual inspection. See the sidebar for more information.

|

Joint Visual Inspections Foreign partners are encouraged to inspect excess defense articles (EDA) prior to delivery through a joint visual inspection. Partners conduct such an inspection before or after an EDA transfer has been authorized by submitting a written request to the implementing agency. Partners must cover their own costs to participate in a joint visual inspection. Source: GAO analysis of Defense Security Cooperation Agency policy. | GAO‑26‑107627 |

If the foreign partner accepts the EDA offer, the implementing agency develops the Letter of Offer and Acceptance—the government-to-government agreement to transfer defense articles to foreign partners.[40] Signed agreements are referred to as “cases” and itemize the defense articles and services offered.[41] The implementing agency moves forward with the proposed EDA transfer following the same process used for FMS, from executing the transfer to closing the case.[42]

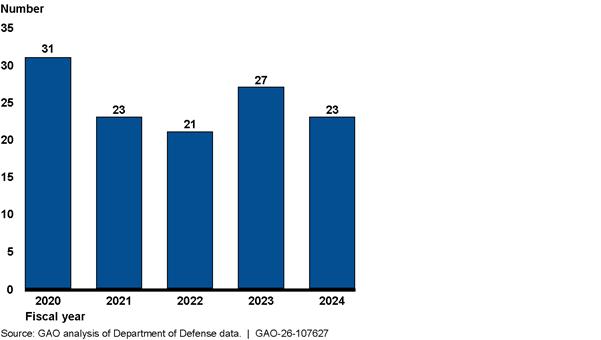

Of the proposed EDA transfers approved, DOD implemented 125 cases with EDA in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, according to our analysis of DOD data.[43] See figure 5 for the annual number of cases with EDA.

Figure 5: Letters of Offer and Acceptance with Excess Defense Articles (EDA) Signed in Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: The data depicted are Letters of Offer and Acceptance—government-to-government agreements—that included EDA that foreign partners signed, and for which they provided any required initial deposits in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Signed agreements are referred to as “cases” and are counted in the first fiscal year of their implementation.

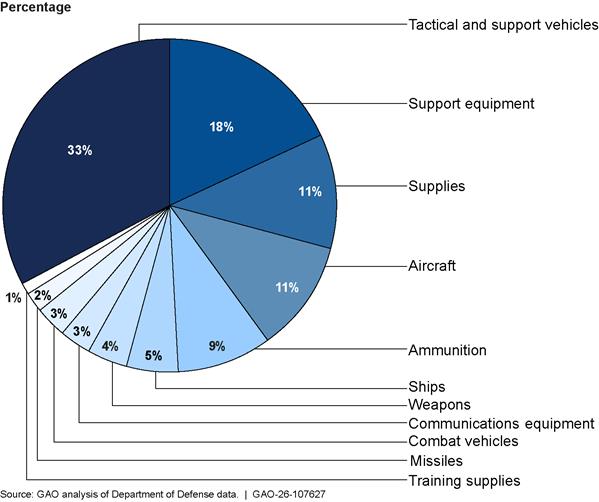

As shown in figure 6, the greatest type of EDA in cases implemented in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 was tactical and support vehicles (33 percent) followed by support equipment (18 percent).

Figure 6: Types of Excess Defense Articles (EDA) in Letters of Offer and Acceptance Signed in Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: The data depicted are equipment categories of EDA itemized in Letters of Offer and Acceptance—government-to-government agreements—that foreign partners signed, and for which they provided any required initial deposits in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Signed agreements are referred to as “cases.”

Our analysis of DOD data also indicates that nearly a quarter (23 percent) of EDA in cases implemented during this period were for significant military equipment.

DOD Conducts Routine Monitoring Checks but Does Not Systematically Track Key Information on EDA After Transfer

DOD Generally Conducts Routine End-Use Monitoring Checks for Selected Foreign Partners

After EDA is transferred to foreign partners, DOD monitors it like any other government-to-government transferred defense article through its Golden Sentry end-use monitoring (EUM) program, which has routine and enhanced levels of monitoring. There are no EUM requirements specific to EDA, according to DSCA officials. These officials told us the vast majority of EDA is subject to routine EUM, and our analysis of DOD data confirmed that 99 percent of EDA included in cases implemented in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 were subject to routine EUM. One case for EDA included a type of communication security equipment that required enhanced EUM, according to our analysis of DOD data.

For routine EUM, SCOs are required to conduct at least one check per quarter for each foreign partner by observing an item or group of items subject to routine EUM. SCOs could observe an EDA item as part of a check, but these quarterly checks do not need to be EDA-specific, according to DSCA officials. Further, these officials told us there is no requirement to observe more than one item or type of equipment to meet the quarterly routine EUM requirement.

SCOs are not funded to conduct routine EUM and, therefore, the Golden Sentry program applies a risk management approach. SCOs conduct routine EUM checks in the course of their other duties and prioritize observing major items, like ships, aircraft, and vehicles, for these checks, according to DSCA policy. In addition, SCOs may use any readily available information source to meet routine EUM check requirements. For example, SCO officials in Greece said they may complete a routine EUM check after seeing U.S. equipment in military parades.

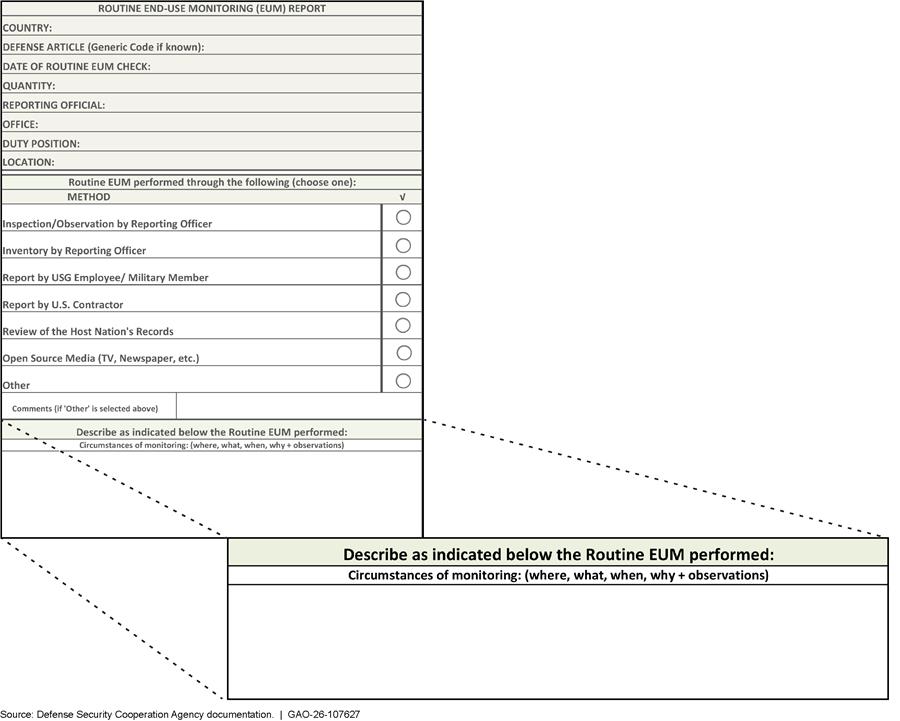

SCOs must document at least one routine EUM check for each foreign partner per quarter by completing an observation form in the SCIP-EUM database. This form records such information as the item observed, whether the item was used as intended, and whether the SCO had issues accessing the item. Officials from the five SCOs we interviewed said they do not collect additional information on EDA during routine EUM checks outside of the information required for the observation form.

As shown in table 2, SCOs generally conducted the quarterly routine EUM checks as required by DSCA policy for our nongeneralizable sample of five foreign partners: Colombia, Greece, Israel, Morocco, and the Philippines. DSCA officials said SCO officials did not complete all the quarterly routine EUM checks in the Philippines in fiscal year 2020 and Colombia in fiscal year 2022 because of extenuating circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and security concerns, including attacks on U.S officials, respectively. Because the SCO did not complete all the checks in the Philippines in fiscal year 2024, DSCA officials told us they plan to conduct a compliance assessment visit by December 2025, which will include training on EUM.

Table 2: Routine End-Use Monitoring Quarterly Checks Completed by Security Cooperation Organizations (SCO) for Selected Foreign Partners, Fiscal Years 2020–2024

|

Foreign partner |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

Colombia |

● |

● |

◑ |

● |

● |

|

Greece |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Israel |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Morocco |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Philippines |

◑ |

● |

● |

● |

◔ |

● = checks completed in all 4 quarters ◕ = checks completed in 3 of 4 quarters (no foreign partners) ◑ = checks completed in 2 of 4 quarters ◔ = checks completed in 1 of 4 quarters

Source: GAO analysis of Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) data. | GAO‑26‑107627

Note: DSCA officials said SCO officials did not complete all the quarterly routine EUM checks in the Philippines in fiscal year 2020 and Colombia in fiscal year 2022 because of extenuating circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and security concerns, respectively. The SCO did not complete all the required checks in the Philippines in fiscal year 2024 and DSCA officials told us they plan to conduct a compliance assessment visit by December 2025. These officials said this visit will include training on EUM and related SCO responsibilities.

DOD Does Not Systematically Track Key Information on EDA After Transfer to Foreign Partners

DOD does not systematically track key information on EDA, including their disposition (i.e., an item’s status, such as deployed, undergoing repair, demilitarized, or expended in combat), after transferring items to foreign partners. The SCIP-EUM database is the sole authoritative repository for all information related to EUM. However, the database does not (1) include all equipment categories, (2) automatically identify items that were transferred under the EDA program, or (3) have disposition data for EDA items that are subject to routine EUM requirements. In addition, while information on disposition is contained in other documents, we found it varies and is not readily accessible.

SCIP-EUM does not include all equipment categories. The SCIP-EUM database does not include all types of items transferred to foreign partners, including items transferred under the EDA program. The database only lists routine EUM items for a subset of equipment categories selected by DSCA that SCOs prioritize for routine EUM checks.[44] See figure 7 for examples of routine EUM items included in the database. As a result, some routine EUM items transferred under the EDA program are not listed in SCIP-EUM. For example, DSCA officials told us the database does not include routine EUM items in the supply category transferred under the EDA program, which represented 11 percent of the cases with EDA implemented in fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Figure 7: Examples of Defense Articles Subject to Routine End-Use Monitoring (EUM) Recorded in the Security Cooperation Information Portal (SCIP)-EUM Database

Note: The data depicted are defense articles subject to routine EUM recorded in SCIP-EUM as of March 2025 for Letters of Offer and Acceptance—government-to-government agreements—that Colombia, Greece, Israel, Morocco, and the Philippines signed, and for which they provided any required initial deposits.

SCIP-EUM does not identify EDA. The SCIP-EUM database does not automatically identify which items were transferred as EDA. The database has a field that identifies how a defense article was acquired, which could identify EDA. However, DSCA officials said this field requires manual entry and, therefore, is not consistently completed. Further, while the SCIP-EUM database imports FMS case information for routine EUM items, such as quantity, it does not include the FMS case field that identifies items as having been transferred through the EDA program. According to DSCA officials, the database does not automatically identify the program through which items are acquired because the authority under which the defense article was transferred does not affect how the article is monitored. The two levels of monitoring—routine and enhanced—depend on the sensitivity of the defense article, not how it was transferred. However, systematically identifying EDA in SCIP-EUM would provide DOD more comprehensive information on the items transferred to foreign partners in its authoritative repository of EUM-related information.

SCIP-EUM does not have disposition data for EDA. The SCIP-EUM database does not have disposition data for EDA items subject to routine EUM requirements. The database has the ability to account for defense articles from their initial shipment to their final disposition. Specifically, SCIP-EUM has a field for the disposition of defense articles, with codes such as deployed, undergoing repair, expended in testing, expended in combat, or demilitarized.[45] However, we found the disposition field was not completed for any of the EDA items in the nongeneralizable sample we reviewed.[46] DSCA officials told us disposition was not completed in SCIP-EUM because all the EDA items in our sample were subject to routine EUM and not subject to the annual serial number inventories required for enhanced EUM. These officials said DOD is only required to track and enter the disposition of enhanced EUM items in the SCIP-EUM database. As discussed above, the vast majority of EDA is subject to routine EUM.

While the disposition field is not completed for routine EUM items in SCIP-EUM, the database contains other documents—routine EUM observation forms and documents on changes in end use—that could provide information on the disposition of EDA. However, we found that the level of disposition information in these documents varied, and the documents were not readily accessible.

Routine EUM observation forms. According to DSCA officials, SCOs can record information on the disposition of the routine EUM items they observe in the narrative response of the routine EUM observation form, but they are not required to do so. DSCA officials said SCO officials determine how much information to include in the form’s “circumstances of monitoring” field shown in figure 8.[47]

We found that 84 percent of routine EUM observation forms recorded in SCIP-EUM for selected foreign partners in the last 5 years included some narrative information on the disposition of items observed, as of March 2025.[48] However, the level of detail of this disposition information varied. For example, for one quarterly check, the SCO restated the physical location of the item recorded elsewhere in the form, whereas in another, the SCO described a foreign partner operating the item during a training exercise.

To access the information on disposition, if recorded, DOD officials could review the individual routine EUM observation forms or a report that summarizes multiple routine EUM observation forms in the SCIP-EUM database.[49] Systematically recording disposition information in the routine EUM observation forms would provide DOD more consistent information on the status of items observed and, thereby, help improve the data entered in SCIP-EUM for officials implementing DOD’s Golden Sentry EUM program.

Documents related to changes in end use. SCIP-EUM contains documents related to changes in end use for defense articles, such as for third-party transfers and demilitarization, under the foreign partner’s historical documents section. SCOs are responsible for uploading third-party transfer authorizations and demilitarization documents to SCIP-EUM in the historical documents section, according to DSCA policy.[50]

SCIP-EUM’s historical documents section is a list of documents that can be organized by foreign partner then filtered by type, such as a third-party transfer authorizations or disposal certificates (which include demilitarization documents). However, these documents are not linked to a specific routine EUM item recorded in the database, according to DSCA officials. Specifically, these officials said the information contained in these documents is not automatically reflected in the list of routine EUM items contained in SCIP-EUM.[51] For example, DOD officials would have to manually search the list of historical documents to find disposal certificates for specific items, including EDA, transferred to a foreign partner. Therefore, the information on changes in end use contained in these historical documents is not readily accessible.

DSCA officials said SCOs could add a comment to an item’s entry in SCIP-EUM’s list of routine EUM items noting a change in end use, such as transferred or demilitarized, but there is no requirement to do so. We found only one comment that described disposition in SCIP-EUM’s list of routine EUM items for selected foreign partners, as of March 2025.[52] Officials from two SCOs we interviewed said they do not generally add comments because the relevant information is recorded elsewhere in SCIP-EUM. However, officials from one SCO said recording comments would provide a centralized location for information.

Further, SCO officials told us that, in general, additional information on the disposition of EDA items would be beneficial. This is consistent with federal internal control standards, which state that management should obtain or generate relevant, quality information and use it to support the functioning of the internal control system.[53] Quality information is appropriate, current, complete, accurate, accessible, verifiable, retained as appropriate, and provided on a timely basis. Further, management should process relevant data obtained or generated from reliable sources into quality information through the entity’s information system.

Officials from one SCO said information on the disposition of EDA would allow them to assess whether a foreign partner has sustained the EDA equipment—which is used and often requires repairs and refurbishment—as needed. This type of information could be useful in the EDA approval process, which considers whether foreign partners can effectively use and support the equipment, among other things. However, officials from four SCOs we interviewed said it would be challenging to seek out and collect additional disposition information for EDA items as a separate requirement in practice because of limited resources and staffing, among other reasons. For example, officials from one SCO told us there are over 480,000 routine EUM items listed in SCIP-EUM for that foreign partner and only one position funded to conduct EUM, where enhanced EUM is the priority.

DSCA officials said that when questions arise on the status of an EDA item, SCOs would be able to refer to their own records outside of the database or collect information on the disposition of EDA. Officials from two SCOs we interviewed told us they review information recorded in SCIP-EUM and then their own records, such as email correspondence and maintenance logs, to address any questions. If necessary, these SCO officials said they also contact the foreign partner to discuss the status of specific items.

By taking steps to more systematically track EDA under existing processes in the SCIP-EUM database, DOD would have better information (i.e., appropriate, complete, and accessible) on these items, including their disposition. Such information on disposition could help inform DOD’s recommendations on future EDA transfers, which are based in part on foreign partner capabilities.

DOD Has Not Taken Key Steps to Assess the EDA Program’s Performance

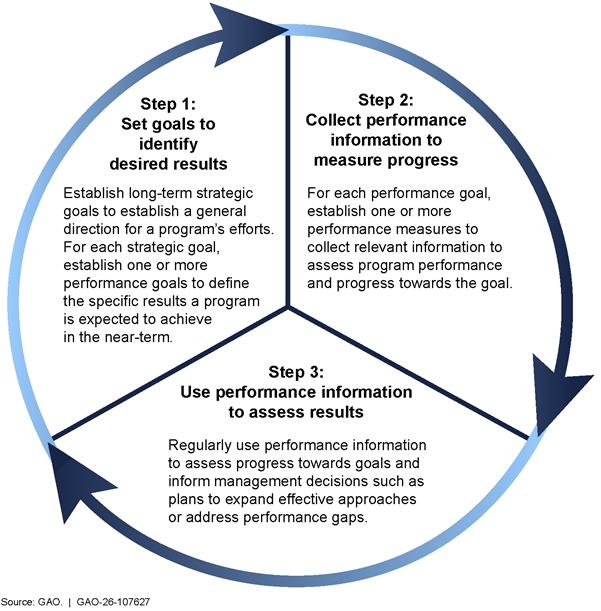

Performance management helps an organization define what it is trying to achieve, determine how well it is performing, and identify what it could do to improve results. Performance management involves measuring the program’s progress towards pre-established goals. As shown in figure 9, we have previously defined performance management as a three-step process by which organizations (1) set goals to identify the results they seek to achieve, (2) collect performance information to measure progress, and (3) use that information to assess results and inform decisions to ensure further progress towards achieving those goals.[54]

Note: GAO has defined performance management as a three-step process that federal agencies can implement to improve their overall performance. See GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

DOD, including its military departments, combatant commands, and SCOs, is responsible for assessing, monitoring, and evaluating the EDA program, according to DSCA officials. DOD has acknowledged the importance of assessing, monitoring, and evaluating its efforts to determine outcomes, identify challenges, make appropriate corrections, and maximize effectiveness of future security cooperation activities in its policies.[55] However, DOD has not taken key steps to assess the EDA program’s performance; specifically, it has not established performance goals or indicators and does not systematically collect performance information to assess results.[56]

DOD Has Strategic Objectives for Security Cooperation but Not Specific Performance Goals for the EDA Program

DOD has established long-term, strategic objectives for its security cooperation efforts, of which the EDA program is one part.[57] Security cooperation aims to advance DOD’s mission of defending the homeland, building security globally, and projecting power while preparing to win decisively against any adversary, according to DSCA policy. The strategic objectives of security cooperation are to build foreign partner capacity, develop and maintain foreign partner relationships, and achieve U.S. priorities and objectives outlined in strategies and plans such as theater security cooperation plans developed by geographic combatant commands, according to DOD officials. Geographic combatant commands have theater security cooperation plans that outline near- and mid-term objectives, as well as desired end states for security cooperation for foreign partners. However, geographic combatant command officials told us these plans do not specifically refer to the EDA program.

Moreover, DOD has not established near-term performance goals for the EDA program to measure progress toward DOD’s strategic objectives. There are no specific, measurable performance goals for the EDA program because it is one of several tools used to achieve strategic objectives related to building foreign partners’ defense capabilities, according to DOD officials.

DOD Does Not Systematically Collect Performance Information to Assess Results and Inform Decisions

In addition to not establishing specific performance goals, DOD has not established specific performance indicators for the EDA program. DOD also does not routinely or systematically collect performance information that could be used to assess results and inform decisions.[58] For example, DSCA officials told us the best indicator for the performance of the EDA program would be to speak with the foreign partner and determine whether they could build or sustain a capability because of an EDA transfer. However, DSCA does not routinely or systematically collect such information.

DOD officials said they may learn about the EDA program’s performance in various, ad hoc ways. For example, DSCA officials said they may discuss EDA transfers with foreign partners during security assistance management reviews, financial management reviews, and program management reviews. These reviews discuss all FMS cases and cover such issues as delivery status, specific weapons systems, and contract awards, according to DSCA officials. While these reviews may involve discussion about specific EDA transfers, they do not cover how the EDA program is performing as a whole for the foreign partner or region, according to a DSCA official.

Additionally, officials from combatant commands, military departments, and SCOs said they may obtain feedback about the EDA program during their foreign partner engagements. In particular, these officials said they learn of the extent to which EDA transfers are achieving intended objectives through such feedback, as well as foreign partner satisfaction. For example

· U.S. Africa Command officials said monthly situational reports cover foreign partners’ challenges and successes with U.S.-provided equipment, including EDA items if appropriate;

· Navy officials said they learn about how a foreign partner operates EDA items through related maintenance and sustainment cases of U.S. equipment for the foreign partner; and

· SCO officials in the Philippines said the foreign partner informs them when the timelines to repair the EDA items are long.

A DSCA official acknowledged it would be beneficial to collect performance information in a systematic way to identify lessons learned and make course corrections as needed when administering the EDA program. For example, this DSCA official said a foreign partner had not provided the funding and crews for three vessels transferred as EDA as expected, which led State to seek additional assurances that the partner would provide the resources needed to sustain the equipment. Foreign partner interest for major items like these vessels generally exceeds the available supply, according to DOD officials, so it is important the equipment is transferred to partners who can effectively use it. Systematically collecting performance information on a regular basis would allow for monitoring and enable DOD to address problems as they arise.

Moreover, DOD officials said they have not conducted any specific assessments of the EDA program’s performance as a whole. While DOD has conducted efforts that may provide insights on aspects of the EDA program, these efforts do not specifically assess the EDA program’s performance or results. In particular:

· DSCA conducts an annual process check that tests a sample of EDA transfers for compliance with relevant requirements, according to a DSCA official. However, this check is focused on the program’s internal controls and does not assess the program’s performance.

· Geographic combatant commanders monitor and evaluate ongoing security cooperation activities, according to DOD policy.[59] However, officials from six geographic combatant commands we interviewed said they have not conducted assessments specific to the EDA program or EDA transfers. For example, U.S. Africa Command officials said that, while they assess, monitor, and evaluate ongoing security cooperation activities within their area of responsibility, these efforts are primarily country-specific and not programmatic.

· DOD officials told us they discuss the extent to which a foreign partner has effectively used EDA items when reviewing proposed EDA transfers to that foreign partner. DSCA officials said the proposed EDA transfer package—specifically, the country team assessment and EDA worksheet—contains information on foreign partners’ past use of similar items. However, these reviews are on a case-by-case basis and do not assess the results of the EDA program as a whole.

DOD has a policy to assess, monitor, and evaluate security cooperation programs and activities.[60] The policy establishes a general framework for assessing, monitoring, and evaluating these efforts and outlines responsibilities for DOD components. However, DSCA officials told us that this policy only applies to security cooperation programs authorized under Title 10 and, therefore, does not cover the EDA program. DSCA officials said they have considered expanding this policy’s application to DOD-administered security assistance programs authorized under Title 22, such as the EDA program. These officials said it is important to assess security cooperation holistically—to include efforts authorized under Titles 10 and 22—to understand the extent to which it helps achieve DOD’s strategic objectives for the foreign partner.

Further, DSCA officials said State should have a role in assessing the extent to which the EDA program is achieving foreign policy objectives. As the EDA program is a security assistance program authorized under Title 22, DSCA administers the program within DOD on behalf of State. State officials said they use the EDA program to develop relationships with U.S. security partners, such as those with limited budgets who cannot purchase new U.S. equipment. Therefore, they have an interest in the EDA program’s performance to ensure the equipment offered meets foreign partners’ needs and builds their capacity, according to State officials.

By taking steps to routinely and systematically measure the EDA program’s performance, DOD would be better able to assess the program’s results and determine the extent to which the program helps achieve security cooperation objectives and develop foreign partner capabilities. Additionally, it would better position DOD and State to regularly communicate the results of EDA to leadership and make timely and better-informed decisions on the program moving forward, such as allocating limited EDA items.

Conclusions

The EDA program is an important security cooperation tool because it provides foreign partners cost-effective access to U.S. equipment to develop their defense capabilities. However, a lack of key information hinders administration and assessment of the EDA program. After transferring EDA to foreign partners, DOD does not systematically track information on EDA in its SCIP-EUM database. The database does not include all equipment categories, identify items as EDA, or have disposition data for EDA subject to routine EUM requirements. Systematically tracking EDA could give DOD better information on these items after transfer, including their disposition. Such information could help inform future decisions on proposed EDA transfers in which foreign partner ability to use and support the equipment is an important consideration.

Moreover, DOD has not taken steps to assess the EDA program’s performance. While DOD has established strategic objectives for security cooperation, it has not developed performance goals or indicators for the EDA program. DOD also has not routinely and systematically collected performance information for the program. Developing and implementing a process that incorporates these key steps to measure the EDA program’s performance would better position DOD to regularly assess the program’s results and determine the extent to which it helps the U.S. achieve security cooperation objectives. Further, it would enable DOD and State to make timely and better-informed decisions about managing the program, including when allocating EDA items in limited supply and high demand among foreign partners.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Director of DSCA takes steps to improve information recorded in SCIP-EUM on EDA items, such as by systematically identifying EDA in the database, recording disposition information in routine EUM observation forms, and noting changes in end use in routine EUM item lists. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Director of DSCA, in consultation with the Department of State, develop and implement a process to manage the EDA program’s performance that includes establishing performance goals, routinely and systematically collecting performance information, and using that information to regularly assess results. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Homeland Security, and State for review and comment. DOD provided written comments that are reprinted in appendix III and summarized below. Commerce provided a technical comment, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Departments of Homeland Security and State did not have any comments on the draft report.

In its written comments, DOD partially concurred with our first recommendation and concurred with our second.

Regarding the partial concurrence, DSCA agreed with the need to record the disposition of EDA items subject to routine EUM. It stated it will direct SCOs to note when EDA items have been expended, disposed, lost, or transferred in the comment fields of SCIP-EUM’s routine summary reports that list foreign partners’ routine EUM items. This step could help DOD more easily access information on the status of EDA items after transfer. However, DSCA stated that systematically identifying EDA in SCIP-EUM would require costly software modifications. According to DSCA, this approach would not be cost-effective because EDA are already tracked under routine or enhanced EUM protocols.

While we understand that EDA are subject to routine or enhanced EUM, the SCIP-EUM database does not identify items that were transferred under the EDA program, as described in the report. We maintain that it is important that DSCA takes steps to improve information on EDA in SCIP-EUM and appreciate DSCA’s attention to cost-effective approaches. Systematically identifying EDA is an example of another step DSCA could take to improve the information recorded in SCIP-EUM—the authoritative repository for all information related to EUM.

The SCIP-EUM database has features that could identify EDA. For example, SCIP-EUM has a field that identifies how a defense article was acquired, which could be used to identify EDA within the database. However, the field requires manual entry and, as noted in the report, is not consistently completed. Identifying EDA through SCIP-EUM’s existing features would provide DOD better information on these items after transfer. For example, it could help SCOs assess whether foreign partners have sustained EDA—which often require refurbishment—as needed. It could also enable SCOs to more easily identify EDA when noting their disposition in routine summary reports, which DSCA stated it will direct SCOs to do. This information could be useful in the EDA approval process, which considers whether foreign partners can effectively support the items.

DOD concurred with our second recommendation to develop and implement a process to manage the EDA program’s performance. DSCA stated it will implement a performance management process that includes measurable goals, systematic data collection, and regular assessments. Such a process, if implemented effectively, could enable DOD to assess the EDA program’s results.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Commerce, Defense, Homeland Security, and State, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at reynoldsj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

James A. Reynolds

Director, International Affairs and Trade

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chair

The Honorable Christopher Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

House Report 118-121 includes a provision for us to report on the excess defense articles (EDA) program.[61] We examine (1) how the Department of Defense (DOD) administers the EDA program, including identifying available defense articles and recipients and integrating EDA with other security cooperation priorities, as appropriate; (2) the extent to which DOD monitors and tracks defense articles transferred to foreign partners through the EDA program; and (3) the extent to which DOD assesses the EDA program’s performance.

To describe how DOD administers the EDA program, we interviewed agency officials that have roles related to the EDA program from DOD, including from the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), military departments, security cooperation organizations (SCO), and geographic combatant commands; the Department of State; and the Department of Commerce.[62] We also reviewed documents such as the following:

· Relevant laws, including sections of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended.

· DOD policies and guidance, including the Security Assistance Management Manual.

· EDA transfer packages and survey messages.

· Commerce’s procedures for reviewing proposed EDA transfers.

To describe characteristics of EDA transfers, we analyzed DOD data on the following.

Approved EDA transfers. DSCA generated a report from the Security Cooperation Information Portal’s (SCIP) EDA Module, which tracks the transfer of EDA to foreign governments and international organizations. The report included such data fields as authority (i.e., grant or sale); country name; and current value for EDA transfers approved in fiscal years 2020 through 2024.[63] We calculated the total number and value of proposed EDA transfers approved during this period, as well as by fiscal year, foreign partner, and authority. We also calculated the average time to approve proposed EDA transfers by comparing the submission and authorization dates.

To determine the reliability of the data provided, we reviewed documentation related to the data; interviewed DSCA officials about the data; and conducted testing for missing data, outliers, and other signs of erroneous information. For example, we identified recent transfers described by Navy officials in interviews that were not included in the report. DSCA officials determined the initial report was not complete and provided us the missing data. After taking these steps, we determined the data provided on EDA transfers approved in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to be sufficiently reliable for reporting the total number and value of EDA transfers and related characteristics, including the authority, foreign partner, and approval timeline.

Implemented cases. DSCA generated a custom report from SCIP, which records foreign military sales (FMS) case information obtained from DOD’s case development system, the military departments’ case execution systems, and DOD’s financial data systems.[64] The report included such data fields as case identifier, line identifier, and implementation date for Letters of Offer and Acceptance with EDA.[65] We calculated the total number of cases with EDA implemented annually in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. We also calculated the total number of EDA case lines implemented in fiscal years 2020 through 2024[66]

· by generic code, which identifies equipment categories; and

· by major defense equipment type, which identifies whether the equipment is significant military equipment or major defense equipment.[67]

To determine the reliability of the data provided, we reviewed documentation related to the data; interviewed DSCA officials about the data; and conducted testing for missing data, outliers, and other signs of erroneous information. For example, we identified several instances where the net line amount had a dash entry. DSCA officials said the dash indicates the EDA case lines were grant transfers and the value is $0.

After taking these steps, we determined the data provided on EDA case lines implemented in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to be sufficiently reliable for reporting the total number of cases with EDA and related characteristics, including equipment type.