FEDERAL TELEWORK

Social Security Administration Needs a Plan to Maintain a Workforce with the Skills Needed to Provide Timely Service

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Dawn G. Locke, LockeD@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Telework use decreased following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic emergency and the President’s January 2025 Return to In-Person Work memorandum among three federal agencies GAO reviewed: the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs (CA).

Officials at all three agencies told us telework likely had some effect on operations. For instance, SSA and CA had staff who had left or considered leaving for other organizations with more telework availability. They told us that other factors, such as a lack of qualified applicants and increased workloads, led to recruiting challenges.

Officials at SSA told us telework was an important recruitment tool. GAO found, however, that SSA is at risk of skills gaps in key occupations, in part because its employees are seeking greater telework flexibility elsewhere. These risks come at a time when SSA is seeking to substantially reduce the size of its workforce. GAO previously reported that it is critical for agencies to carefully consider how to strategically downsize their workforces and maintain the staff resources to carry out their missions before implementing workforce reduction strategies (GAO-18-427). Agency officials said SSA has a human capital plan it can update to help guide staffing decisions, but has not done so because they are focused on responding to administration workforce priorities such as implementing skills-based hiring. However, without developing or updating a human capital plan, SSA may lack the information needed to ensure it has the mission-critical staff necessary to provide timely public service.

Officials at all three agencies also told us factors other than telework contributed to problems in providing key customer services at times during fiscal years 2019 through 2024. For example,

· BIA attributed delays in providing probate services to Tribes and their citizens to factors such as staffing shortages and funding issues.

· SSA officials cited a learning curve related to a new disability case processing system and a substantial increase in the volume of submitted medical evidence as contributors to delays in processing disability claims.

· CA reported an unexpectedly large volume of applications and high rates of attrition that contributed to substantial delays in 2023 passport processing.

However, none of the agencies had evaluated their telework programs to determine their effects on its performance and identify problems, a key practice for successful telework programs. Officials said they had not done so because they were unsure how to or were not required to conduct such evaluations.

GAO determined that it was not practical for BIA and CA to evaluate their telework programs now because their staff can no longer use regular telework. Since some of SSA’s program offices continue to regularly use telework, it remains important for the agency to evaluate its telework program to identify any problems or issues and make appropriate adjustments.

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal agencies have used telework to help accomplish their missions, maintain continuity of operations during emergencies, and recruit and retain employees.

GAO was asked to review telework use at BIA, SSA, and CA. This report (1) summarizes how often the agencies’ staff teleworked from July 2019 through May 2025, and how the agencies’ telework programs changed following the President’s issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum in January 2025; (2) describes the effects telework’s use had on the agencies’ operations and customer service; and (3) assesses the extent to which the agencies followed selected key practices for successful telework programs.

For this report, GAO collected and analyzed the agencies’ telework data from July 2019 through May 2025. GAO reviewed and summarized agencies’ plans to change telework use before and after January 2025. GAO analyzed agency performance information, and compared agencies’ activities with selected key telework practices identified in GAO-21-238T. GAO also conducted interviews and 11 discussion groups with agency staff.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that SSA (1) update its human capital plan to ensure the agency can identify and retain mission-critical staff, given recent changes in SSA’s telework posture and efforts to reshape the organization, and (2) evaluate its telework program to identify problems or issues with the program and make appropriate adjustments and assess the effects of telework on agency performance. SSA did not agree or disagree with the recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BIA |

Bureau of Indian Affairs |

|

CA |

Bureau of Consular Affairs |

|

DDS |

Disability Determination Services |

|

DI |

Disability Insurance |

|

NPIC |

National Passport Information Center |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately. GAO.

January 23, 2026

Congressional Requesters

Telework has been an important tool federal agencies have used to help accomplish their missions and to maintain continuity of operations during emergencies, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic and severe weather.[1] As employees became more accustomed to working from home, agencies offered telework as a recruiting and retention incentive. However, expanded telework use also exacerbated some challenges for agencies, such as projecting real property needs to ensure they effectively use available space.

In November 2024, we reported that there was substantial variation in telework use among selected agencies that provided customer-facing services to the public.[2] We found that telework helped those agencies recruit staff and significantly increased applicant interest, but sometimes contributed to staffing gaps when employees left the agency for more telework opportunities at other agencies or in the private sector.

In January 2025, the President issued a memorandum directing agencies to require employees to work in person on a full-time basis.[3] According to an Office of Personnel Management (OPM) memorandum, “Virtually unrestricted telework has led to poorer government services and made it more difficult to supervise and train government workers.”[4] The memorandum added that, “Fairness requires that federal office employees show up to the worksite each day like most other American workers.” The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and OPM subsequently released related guidance to implement the memorandum.[5] The guidance exempted military and Foreign Service spouses working remotely from the return to office requirement.[6] Agencies were directed to describe how they will determine exceptions to the in-office requirement for a disability, certain medical conditions, and “other compelling reasons.”[7] In December 2025, OPM issued a revised telework and remote work guide that reaffirmed the guidance.[8]

You asked us to review telework use at federal agencies, specifically at the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of State. This report (1) summarizes how often BIA, SSA, and State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs (CA) staff teleworked from July 2019 through May 2025, and how the agencies’ telework programs changed following the President’s issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum in January 2025; (2) describes the effect telework’s use had on operations and customer service; and (3) assesses the extent to which the agencies followed selected key practices for successful telework programs.

For our first objective, we collected and analyzed telework data and related documents from the agencies from July 2019 through May 2025 using a structured data collection instrument. We also reviewed and summarized agencies’ plans to change telework use before and after the President’s January 2025 issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum and subsequent OMB and OPM guidance.

We focused our review on the use of telework rather than the use of remote work.[9] However, when agencies provided their respective breakdowns of the percentage of employees who teleworked during specific numbers of days per pay period in December 2024, they also included data on the percentage of employees who worked remotely.

For our second objective, we reviewed documentation and agencies’ responses to questions to determine how they changed their operations from July 2019 through January 2025 to accommodate the use of telework, and the effects of telework policies and use on recruiting, hiring, retention, employee engagement, and training. We reviewed our previously issued reports that discussed operational (e.g., recruiting, retention, employee engagement) and customer service challenges at each agency, and interviewed agency officials about how they were addressing related open recommendations.

We also met with agency officials to understand the effects of telework use on operations and performance among program and local offices that provide or support the following high impact services at our selected agencies:[10]

· inquiring about a probate order (BIA),

· receiving trust assets (BIA),

· applying for a replacement Social Security card (SSA),

· applying for Social Security retirement benefits (SSA),

· applying for adult disability benefits (SSA), and

· applying for a U.S. passport (CA).

Specifically, from August 2024 through January 2025 before the President issued the Return to In-Person Work memorandum, we conducted five supervisory discussion groups and six discussion groups with non-supervisory staff during site visits in two regional areas—Alaska and south Florida. We selected these locations in part to observe how members of the public from various regions and communities interacted with federal employees when seeking in-person services.[11] Findings from these discussion groups are not generalizable to other staff from selected agencies we reviewed, or federal employees government-wide. However, these findings provide illustrative examples of how the use of telework affected operations and customer service.

We reviewed agency performance and accomplishment reports and interviewed agency officials to determine what factors may have contributed to the changes in results for selected performance measures applicable to the selected high impact services from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. In addition, we interviewed nine stakeholder groups from August through November 2024, such as employee unions and organizations serving federally-recognized Tribes and Alaska Natives, people with disabilities, and SSA managers. We identified these groups based on research of organizations that have interacted with populations that our selected agencies serve.

For our third objective, we compared agency actions before the President issued the Return to In-Person Work memorandum in January 2025 to four selected key practices for successfully implementing telework programs.[12] These key practices related to telework program evaluation or employee performance management, such as establishing telework eligibility, managing employee performance, tracking and collecting data, and evaluating telework programs. We selected these four key practices because we determined they were most relevant to agencies that have established telework programs and have used telework for several years, such as those in our review. See appendix I for more information about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

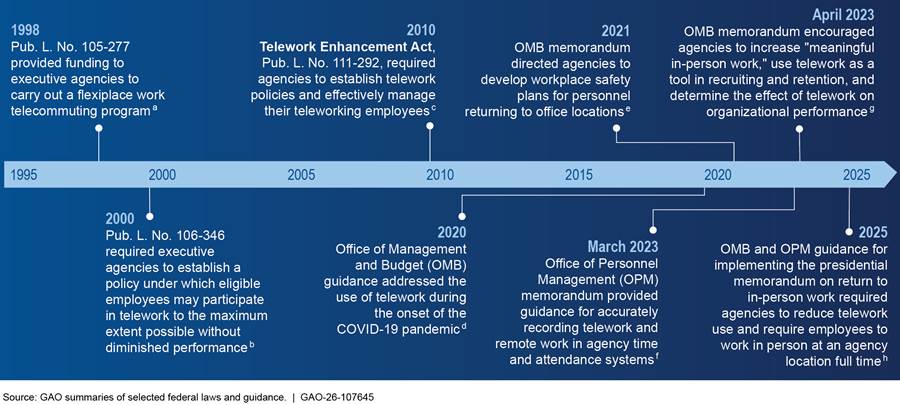

Since 1998, multiple federal laws, as well as agency guidance, have addressed telework in the federal government, as shown in figure 1.[13]

Figure 1: Timeline of Selected Federal Laws and Guidance Influencing Telework Use in the Federal Government, 1998-2025

aPub. L. No. 105-277, tit. VI, § 630, 112 Stat. 2681-522-23 (1998). Flexiplace is the concept of working at locations other than a traditional government office.

bPub. L. No. 106-346, app., tit. III, § 359, 114 Stat. 1356, 1356A-36 (2000).

cPub. L. No. 111-292, 124 Stat. 3165 (2010).

dOMB guidance guiding the use of telework during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic include Office of Management and Budget, Aligning Federal Agency Operations with the National Guidelines for Opening Up America Again, OMB M-20-23 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2020); Harnessing Technology to Support Mission Continuity, OMB M-20-19 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 22, 2020); Federal Agency Operational Alignment to Slow the Spread of Coronavirus COVID-19, OMB M-20-16 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 17, 2020); Updated Guidance for the National Capital Region on Telework Flexibilities in Response to Coronavirus, OMB M-20-15 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 15, 2020); and Updated Guidance on Telework Flexibilities in Response to Coronavirus, OMB M-20-13 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2020).

eOffice of Management and Budget, COVID-19 Safe Federal Workplace: Agency Model Safety Principles, OMB M-21-15 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 24, 2021).

fOffice of Personnel Management, Remote/Telework Enhancements to Enterprise Human Resources Integration Data Files (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 7, 2023).

gOffice of Management and Budget, Measuring, Monitoring, and Improving Organizational Health and Organizational Performance in the Context of Evolving Agency Work Environments, OMB M-23-15 (Apr. 13, 2023).

hOffice of Management and Budget and Office of Personnel Management, Agency Return to Office Implementation Plans (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2025).

On January 20, 2025, the President issued a memorandum on the return to in-person work that directed all agencies to “take all necessary steps to” terminate remote work arrangements and require employees to work in person at an agency location on a full-time basis, with exemptions granted by department and agency heads.[14] As previously noted, OPM said that the use of “virtually unrestricted telework” adversely affected government services and worker supervision and training.[15] Subsequent guidance from OPM clarified that the memorandum applied to both remote workers and teleworkers.[16] Additional guidance from OMB and OPM directed agencies to revise their policies to bring them into compliance with the memorandum, and to provide timelines for the return of all eligible employees to in-person work.[17]

In February 2025, OPM issued a memorandum stating that agencies should not interpret or apply collective bargaining agreement provisions “that purport to restrict the agency’s right to determine overall levels of telework” to prevent compliance with the President’s Return to In-Person Work memorandum.[18]

In July 2025, OPM issued a memorandum encouraging agencies to allow telework for religious practices, so employees can, for example, avoid commuting to work on days when they observe time-specific religious practices during breaks in the workday.[19] The memorandum states that telework is often a low-cost solution that typically does not impose substantial operational burdens when used on a limited basis, such as for a religious accommodation.

As previously discussed, we also compared agency actions before the President issued the January 2025 Return to In-Person Work memorandum to selected key practices for successfully implementing telework programs. These practices are based on our prior work, OMB guidance, and the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010.[20] See table 1.

|

Employees are approved for telework on an equitable basis |

Federal telework policies should outline eligibility criteria that apply to all employees to help, in part, ensure the suitability of both the tasks and the employee for telework. |

|

Same performance standards to evaluate both teleworkers and non-teleworkers |

The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 requires agencies to ensure that teleworkers and non-teleworkers are treated the same for the purposes of performance appraisals, among other management activities.a |

|

Processes, procedures, and/or a tracking system to collect data to evaluate the telework program |

Federal agencies should have a tracking system that provides accurate participation rates and other information about teleworkers and the program, such as a formal head count of routine and situational teleworkers. Agencies should also develop processes and procedures to collect quality data about their telework programs. |

|

Program evaluation that identifies problems or issues with the telework program and makes appropriate adjustments |

Federal agencies should develop program evaluation tools and use such tools from the very inception of the telework program to identify and correct problems. Evaluations can be used, for example, to identify the effects of telework on organizational or individual performance, or customer service. |

Source: GAO analysis of prior GAO work, Office of Management and Budget guidance, and the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010. | GAO‑26‑107645

Note: We selected these practices because we determined they were most relevant to agencies that have established telework programs and have used telework for several years, such as those in our review.

a5 U.S.C. § 6503(a)(3).

Report Definitions

This report describes agencies’ “return to office” plans, operations, and customer service. See table 2 for definitions of these terms.

|

“Return to Office” Plans |

“Return to office” plans in this context refers to directives, guidance, and other information that outlines agency requirements for returning all eligible employees to in-person work after the President issued the Return to In-Person Work memorandum in January 2025, and determining which categories of employees would be granted exemptions from these requirements. |

|

Agency Operations

|

Agency operations in this context refers to day-to-day activities and processes that selected agencies undertook as they used telework. This includes determining: · the effects of offering telework on agency recruiting, hiring, retention, employee engagement, and training; and · changes the selected agencies made to policies, processes, and use of new technology to integrate telework in their day-to-day activities. |

|

Customer Service

|

Customer service in this context refers to agencies’ individual interactions with the public. This report examines whether telework and other factors may have contributed to changes in customer service outcomes. |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documents and interviews with agency officials. | GAO‑26‑107645

Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs

Table 3: Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs Telework Implementation and Performance at a Glance

|

Highlights Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) ended routine telework in response to the President’s January 2025 memorandum after several years of decreasing use. BIA officials said that limited telework use was one of several factors that may have contributed to staffing challenges. · Agency Operations: BIA officials said telework reductions beginning in April 2024 could exacerbate recruiting problems primarily driven by other factors. · Customer Service: BIA officials said factors other than telework led to a substantial backlog in carrying out their probate responsibilities. BIA had taken steps to implement key telework practices, but had not evaluated its telework program to determine its effects and identify problems. |

Source: GAO analysis of BIA information and interviews with BIA officials. | GAO‑26‑107645

Bureau of Indian Affairs Background and High-Risk Human Capital Areas

The Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs provides a wide variety of direct services, or funding to Tribes to provide such services, to 575 federally recognized Tribes, serving approximately 2.5 million individuals. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is a component of Indian Affairs responsible for carrying out several of Indian Affairs’ missions, including the administration and management of trust assets and justice services, among others. For example, BIA assists tribal governments and individuals with managing, protecting, and developing their trust lands and natural resources. This assistance includes providing real estate services, land titles and record assistance, and probate (i.e., asset distribution) services for certain assets of deceased individuals.

Since 2017, our High-Risk List has included improving federal management of programs that serve Tribes and their members, including programs related to assets held in trust. We reported that BIA has made progress in these areas, but more work is needed. Our 2025 High-Risk update stated that BIA must develop and implement an action plan to address the root causes of management weaknesses—such as slow processing times and staffing limitations—and monitor agency actions to ensure sustained progress in these areas.[21]

BIA Ended Routine Telework in Response to the President’s January 2025 Memorandum After Several Years of Decreasing Use

Interior revised its telework policy and required staff with telework arrangements to report for full-time in-person work by March 4, 2025, in response to the President’s Return to In-Person Work memorandum and subsequent guidance from OMB and OPM.[22] Under the revised telework policy, routine telework is available only in limited circumstances, such as for a disability, medical conditions, or other compelling reasons.

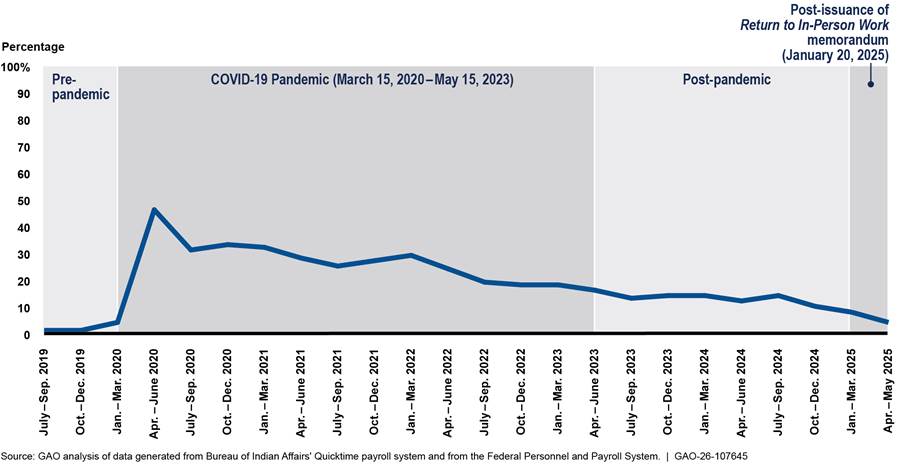

Telework use at BIA decreased after the implementation of this policy. From January through May 2025, telework use at BIA decreased from 8 percent to 5 percent of total work hours. Situational telework was still permitted under Interior’s updated policy, which likely accounted for the agency’s ongoing but decreased use of telework since January 2025. As figure 2 shows, the decrease in telework use in 2025 is part of a broader decline in use that started in 2020 after telework levels peaked during the pandemic.

Figure 2: Percentage of Hours Worked in Telework Status at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, July 2019-May 2025

Notes: The start date of the COVID-19 pandemic period in this graphic is March 15, 2020, when the Office of Management and Budget issued guidance to federal agencies in the National Capital Region stating that they should provide maximum telework flexibilities to employees. The end date is May 15, 2023, the effective date of termination of maximum telework as part of the federal government’s operating status, in accordance with the Office of Personnel Management’s guidance.

As figure 2 shows, BIA staff rarely teleworked before the pandemic. However, BIA leveraged telework during the pandemic to ensure continuity of operations. In July 2021, after the pandemic began, Interior, of which BIA is a component, issued a telework policy stating that employees could telework up to 8 days per pay period (usually 80 percent of an employee’s work hours). In spring 2024, Interior took steps to reduce telework use among its components by generally limiting telework to no more than 50 percent of hours per pay period (usually 5 days).

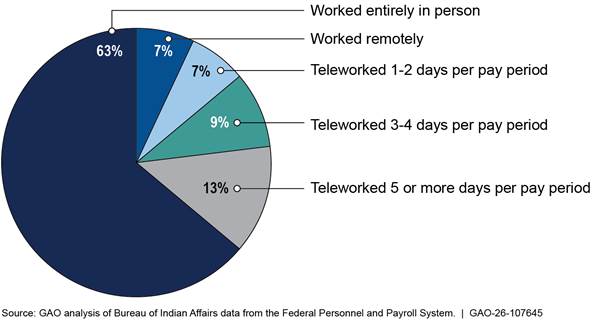

Despite the availability of telework for up to half of their work hours, BIA staff spent most of their time working in person at a BIA office in 2024. As shown in figure 3, during a 2-week pay period in December 2024—before the release of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum—we found that 63 percent of staff did not telework. Of those employees who did, a majority teleworked 4 or fewer days during the pay period.

Figure 3: Status of Telework, Remote Work, and In-Person Work at the Bureau of Indian Affairs During 2024 Pay Period 24 (December 1-14, 2024)

Notes: Telework data from individual employees rounded to the nearest whole employee. The data are not generalizable to all pay periods or illustrative to time spent teleworking across time. For the purposes of this report, remote work is a work arrangement where a federal employee performs work from an alternate worksite (generally the person’s residence) and is not expected to report to an agency location on a regular and recurring basis. It is distinct from telework, where workers are expected to report to an agency location regularly and have regularly scheduled days where they work from an alternate worksite.

We found that BIA staff’s limited telework use was due to in-person requirements and employee preference. According to Interior’s 2021 telework policy, positions that required an in-person presence were not telework eligible. Examples of such positions included law enforcement, social services, and irrigation services.

Among BIA staff with whom we met, even those who could telework regularly told us that they chose to telework fewer days than allowed because (1) their customers preferred to meet face to face, (2) certain tasks required that they be present at the office, and (3) they enjoyed camaraderie with coworkers.

On the occasions where they did telework, staff said that telework was particularly useful when they were feeling sick but felt well enough to continue working, or when weather prevented commuting to the office. Some staff also said that they teleworked when completing focus-intensive work, as they could work more effectively at home without distractions that came from being in the office.

Telework use at BIA also varied by office. During the pandemic, BIA field offices could adjust their telework use based on transmission rates in their area and the needs of the individuals and Tribes they served.

BIA Officials Said That Limited Telework Use Was One of Several Factors That May Have Contributed to Staffing Challenges

Agency Operations: BIA officials said telework reductions beginning in April 2024 could exacerbate recruiting problems primarily driven by other factors

Recruiting. BIA officials told us they were concerned that reductions in telework stemming from Interior’s April 2024 telework policy change could exacerbate long-standing staffing challenges by making it more difficult to recruit and retain employees. They cited fewer applications for job openings as a possible indicator. Specifically, BIA received an average of 16 applications per job announcement during fiscal year 2024, but then received 12 applications per announcement from October 2024 through January 2025.[23]

They told us, however, that the longest-standing reasons the agency struggled to recruit staff include (1) the lack of qualified applicants interested in working in remote and rural areas, and (2) a high workload relative to similar positions at other agencies. They added that, recently, a lack of affordable housing in some areas where the agency operates has contributed to recruitment and retention challenges. Such factors are not unique to BIA. We previously reported that other federal agencies had difficulty hiring in areas with a high cost of living or in remote areas with low populations.[24]

In November 2024, we reported that Indian Affairs faced challenges with recruiting due to budget uncertainty and lack of human resources training.[25] These challenges, along with retention challenges among certain staff, contributed to understaffing at BIA regional offices, which reduced the agency’s ability to disburse funding to tribal entities, according to an Interior official and representatives from a national tribal organization.

For these and other reasons, we recommended, and Indian Affairs agreed, that it needed to take six actions to address workforce capacity challenges that have affected the agency’s ability to provide key services. Those actions include:

· tracking employee vacancy data across Indian Affairs in a systematic and centralized manner;

· identifying skills, knowledge, and competency gaps in mission-critical occupations across Indian Affairs; and

· developing consolidated written guidance that clarifies what hiring authorities, recruitment incentives, and workforce flexibilities can be leveraged for recruitment and retention purposes.

The recommendations remain open as of September 2025. These actions remain necessary to ensure the agency can recruit and retain mission critical staff, given that (1) it can no longer offer routine telework as an incentive, and (2) it has a growing backlog of probate cases, a key BIA service we discuss in more depth later.

Employee engagement. We found BIA employee engagement—as identified in the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey—increased in all but one year from 2019 through 2024, while telework use during these years varied.[26] BIA officials were not certain if telework contributed to increased employee engagement, but supervisors we met with told us that telework availability helped improve staff’s morale by providing them with better work-life balance.

Virtual communication technology. BIA officials said that the agency expanded the availability of video conferences, digital files, electronic signatures, and other technologies, some of which was necessary for the continuity of operations during the pandemic. BIA officials told us these technologies helped staff work more efficiently, provided additional customer service options, and made it possible for staff to more easily telework because they could access documents and meet virtually with colleagues from home.

BIA officials told us these technologies also helped improve customer service by making agency staff more readily available to communicate with tribal members, particularly those living in remote areas. A leader of an organization representing tribal members agreed, saying that virtual meetings may be easier than in-person meetings for BIA customers who live in remote areas and cannot easily travel to an agency office.

However, BIA officials and leaders from organizations representing tribal members told us that virtual communications were not appropriate in all cases. One BIA official told us that despite the availability of virtual technology, they opted for in-person customer interactions because face-to-face meetings were an important cultural norm for the Tribes they served. Furthermore, leaders from organizations representing tribal members told us that using virtual communications technologies may be difficult for those who live in remote areas with poor or nonexistent internet access.

Customer Service: BIA officials said other factors besides telework led to a substantial backlog in carrying out their probate responsibilities

|

The Department of the Interior is responsible for probating certain trust and restricted fee assets so they can be transferred to the appropriate recipients once a tribal member dies. Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is responsible for gathering information about the assets and other relevant information—such as death certificates and wills—for the probate process. BIA then provides this information to Interior’s Office of Hearings and Appeals, which then evaluates the information and issues a probate order indicating how the deceased individual’s assets should be distributed. BIA and Interior’s Bureau of Trust Funds Administration then distribute assets to the appropriate recipients. Once this process is complete, a probate case is considered closed. BIA has identified probate services as a high priority area for customer service improvement. The bureau reported that it had a backlog of over 32,000 probate cases at the beginning of fiscal year 2024 and, according to BIA officials, has had a probate backlog since at least 2011. |

Source: GAO analysis of Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) documents and information from BIA officials. | GAO‑26‑107645

BIA officials told us that other long-term and persistent challenges, rather than the agency’s limited telework use, contributed to difficulties with the timely processing of probate cases. They said, for example

· BIA depends on a decedent’s family to gather required documents, such as death certificates, marriage licenses, and adoption decrees. According to agency officials, it can take decedents several months to complete this step once the probate case is opened.

· A shortage of judges in Interior’s Office of Hearings and Appeals leads to delays in the probate process.

BIA officials also said that pandemic-related circumstances contributed to the backlog, specifically:

· higher than normal rates of death among tribal members, and

· temporary closures of some BIA offices during the early pandemic, as the agency assessed the safety of staff interacting with the public and with physical documents. These closures made it difficult for some BIA customers to deliver probate-related documents, delaying the agency’s ability to gather the information necessary to process the case. BIA has since reopened the offices.

To address the probate backlog and improve service to those involved in the probate process, BIA officials said they are exploring ways for interested parties of a probate case to submit documents to the agency online.

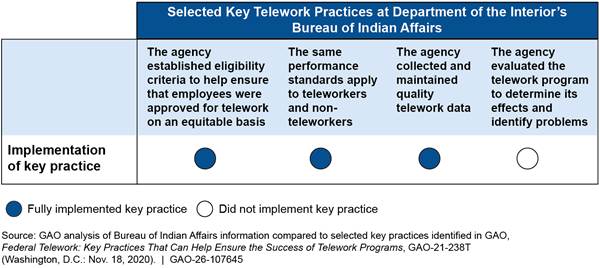

BIA Had Taken Steps to Implement Key Telework Practices, but Had Not Evaluated Its Telework Program to Determine Its Effects and Identify Problems

BIA fully addressed key practices for establishing telework eligibility criteria on an equitable basis and ensuring that the same performance standards were used to evaluate both teleworkers and non-teleworkers. It also had processes and procedures to collect quality telework data. See figure 4. Appendix II includes information on how BIA fully addressed these practices.

Figure 4: Bureau of Indian Affairs Telework Program Alignment with Selected Key Practices for Implementation of Successful Federal Telework Programs

Note: We selected the key practices listed in the table because we determined they were most relevant to agencies that have established telework programs and have used telework for several years, such as those in our review.

However, BIA officials told us that neither BIA nor Interior had evaluated the effects of telework. They said this was because they did not know what areas to evaluate. A key practice for successfully implementing a telework program is to evaluate the program to identify problems or issues with the program and to make appropriate adjustments.[27] Without such evaluations, BIA lacked information agency officials needed to identify and address problems with the telework program, and more fully leverage any benefits at the time.

However, circumstances changed during our review, resulting in substantially lower levels of regular telework use as of April and May 2025 compared to before the January 2025 issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum. Therefore, we determined it is not practical for BIA to evaluate its telework program given its current use.

Social Security Administration

|

Highlights Social Security Administration (SSA) substantially reduced routine telework in response to the President’s January 2025 memorandum after several years during which most agency staff teleworked frequently. SSA managers and staff said telework was an important retention tool, but the agency lacks a plan for identifying and retaining mission-critical staff. · Agency Operations: SSA data and interviews show that the agency was at risk of losing staff to other organizations that offered more telework before return-to-office requirements beginning in January 2025. · Customer Service: SSA officials cited other factors besides telework as contributing to increased claims processing time and walk-in customer wait times. SSA has taken steps to implement key telework practices, but has not evaluated its telework program to determine its effects and identify problems. |

Source: GAO analysis of SSA information and interviews with SSA officials. | GAO‑26‑107645

Social Security Administration Background and High-Risk Human Capital Areas

The Social Security Administration (SSA) provides financial assistance to eligible individuals through its major benefit programs such as Old-Age and Survivors Insurance, Supplemental Security Income, and the Disability Insurance (DI) program.[28] Besides administering retirement and disability benefits, SSA maintains workers’ earnings records and supports Medicare and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

DI provides benefits to individuals who have qualifying disabilities, and their eligible family members. Individuals are generally considered to have a disability if (1) they cannot perform work that they did before and cannot adjust to other work because of their medical condition(s), and (2) their disability has lasted or is expected to last at least 1 year or is expected to result in death.[29]

In addition to administering this and other benefit programs, SSA issues Social Security numbers, which are used to monitor SSA benefits as well as for many non-Social Security purposes. Most original Social Security cards are issued at birth. SSA also issues original cards for applicants who do not obtain them at birth, as well as replacement cards.

SSA customers may access the agency’s services in several ways, including: (1) in person at SSA field offices, (2) by phone with field office staff, and (3) online. See table 6 for primary service delivery channels for selected SSA services.

Table 6: Primary Service Delivery Channels for Some Commonly Used Social Security Administration Services

|

|

In person at Social Security Administration facility |

By phone with field office staff |

Online |

|

Benefits applications and appeals |

|

|

|

|

Apply for Disability Insurance benefits |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Appeal a benefit decision |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Social Security cards |

|

|

|

|

Obtain a replacement Social Security card |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Source: GAO analysis of Social Security Administration information. | GAO‑26‑107645

SSA has long had major staffing shortages that have affected its ability to meet its mission and predate the expansion of telework due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Improving and Modernizing Federal Disability Programs has been on our High-Risk list since 2003 in part because SSA experienced challenges achieving its desired number of staff for both initial disability claims and appeals. More recently,

· we recommended in November 2022 that SSA develop a plan for managing anticipated increases in disability workloads due to COVID-19-related illnesses and other factors such as staff attrition in key areas.[30] As of June 2025, this recommendation remains open; and

· in our 2023 High-Risk update, we reported that SSA lacked a detailed plan to address workload management issues caused in part by significant challenges hiring and retaining staff since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[31] In the 2025 update, we also reported that SSA had developed a plan, but the plan lacked timelines for completing related actions as well as metrics for monitoring progress on achieving its goals.[32]

Similarly, in November 2024, the SSA Inspector General reported that attrition at the agency contributed to a net decline in staffing. As a result, it stated that SSA needs to “develop and implement human capital and operating plans that address its human capital risks, including how ‘the agency’ will better compete for the talent it needs, retain the employees it has, and eliminate service delays and backlogged workloads with various staffing levels.”[33]

SSA Substantially Reduced Routine Telework in Response to the President’s January 2025 Memorandum After Several Years During Which Most Agency Staff Teleworked Frequently

In January 2025, SSA suspended the agency’s previous telework program in response to a Presidential Memorandum and accompanying guidance from OMB and OPM.[34] SSA notified employees that, subject to certain exceptions, they were expected to report to the office for full-time in-person work by March 2025. Some exceptions, for example, included the Office of Hearings Operations and Office of Financial Policy and Program Integrity, which continued to allow their employees to regularly telework.

Consequently, telework hours as a proportion of total SSA work hours decreased from 35 percent in January-March 2025 to 13 percent in April-May 2025. Situational telework is still permitted under SSA’s updated policy, which likely accounted for some of its ongoing but decreased use of telework since January 2025, according to agency policy documents.

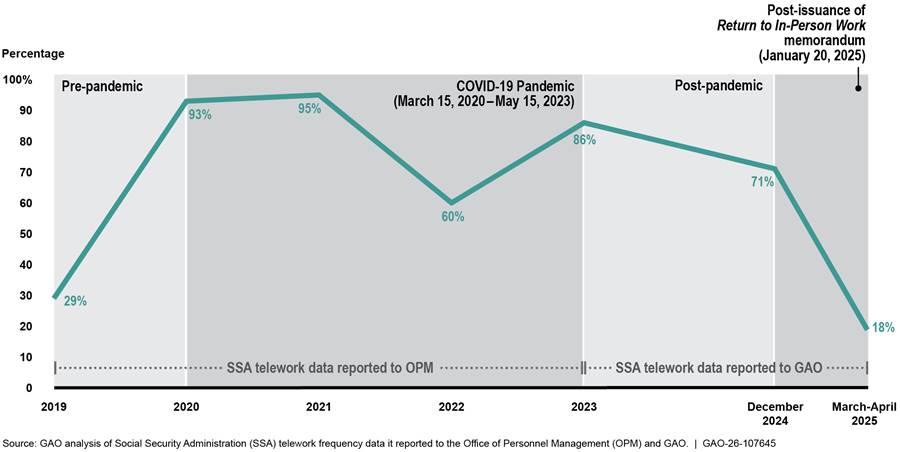

Agency data reported to OPM showed that nearly 30 percent of SSA staff, including field offices, regularly teleworked prior to the pandemic (i.e., teleworked 3 or more days per 2-week pay period). The data also showed that most SSA staff regularly teleworked for several years during and after the pandemic through the end of 2024.[35] See figure 5.

Figure 5: Percentage of Social Security Administration Employees Teleworking 3 or More Days per Pay Period, by Fiscal Year

Notes: SSA employees began returning to the office for in-person work starting in March 2022, which accounted for a decrease in telework in fiscal year 2022 compared to fiscal year 2021. SSA officials said they could not pinpoint specific cause as to why telework use increased between fiscal years 2022 and 2023 without conducting an analysis. The start date of the COVID-19 pandemic period in this graphic is March 15, 2020, when the Office of Management and Budget issued guidance to federal agencies in the National Capital Region stating that they should provide maximum telework flexibilities to employees. The end date is May 15, 2023, the effective date of the termination of maximum telework as part of the federal government’s operating status, in accordance with the OPM guidance.

According to data from SSA, telework use began to decline in mid-2024. SSA staff worked 39 to 42 percent of their hours in telework status in the second half of 2024, down from 50 to 55 percent of hours they teleworked during the first half of the year.[36]

SSA officials attributed part of the midyear decline in telework use to a policy change in April 2024 that required certain staff—around 10,000 employees—to work at an office location more often. In an email, the then-Commissioner explained the need for the change, stating, “Our return to a greater onsite presence not only gives us more opportunity for collaboration, engagement, and innovation, but it also brings us into alignment with other federal agencies across government, (which) have been increasing their own onsite presence.”

According to the email, employees who were to increase their in-office presence included

· Commissioner’s office staff who could telework up to once per week (or up to 2 days per pay period), and

· regional office and area director staff who could telework up to 2 days per week (or up to 4 days per pay period).

Other SSA positions, comprising around 83 percent of SSA’s workforce in 2024, were not affected by the April 2024 policy change. For example,

· field office employees providing in-person customer service could continue to telework up to 2 days per week (or up to 4 days per pay period), and

· teleservice center employees and claims processors who did not have public-facing responsibilities could continue to telework up to 4 days a week (or up to 8 days per pay period).

SSA officials added that the agency’s telework policy prioritized customer service and allowed managers to reduce, suspend, or cancel scheduled telework in cases where customers needed more in-person service. Field office staff we met with told us that it was not unusual for their supervisors to require that they come into an office location on their scheduled telework days to ensure adequate coverage.

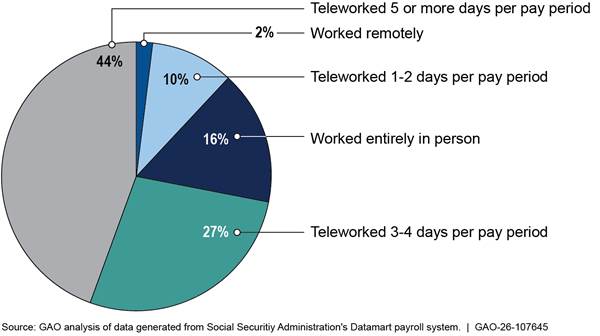

We found that, as recently as December 2024, 71 percent of SSA staff teleworked at least 3 days per pay period. See figure 6.

Figure 6: Status of Telework, Remote Work, and In-Person Work at the Social Security Administration During 2024 Pay Period 24 (December 1-14, 2024)

Notes: Telework data from individual employees rounded to the nearest whole employee. The data are not generalizable to all pay periods or illustrative to time spent teleworking across time. For the purposes of this report, remote work is a work arrangement where a federal employee performs work from an alternate worksite (generally the person’s residence) and is not expected to report to an agency location on a regular and recurring basis. It is distinct from telework, where workers are expected to report to an agency location regularly and have regularly scheduled days where they work from an alternate worksite.

SSA Managers and Staff Said Telework Was an Important Retention Tool, but the Agency Lacks a Plan for Identifying and Retaining Mission-Critical Staff

Agency Operations: SSA data and interviews show that the agency was at risk of losing staff to other organizations that offered more telework before return-to-office requirements beginning in January 2025

Recruitment. SSA has long had difficulty hiring staff as workload demands increased.

In fiscal year 2023, SSA received direct hiring authority from OPM for its frontline, direct service positions. Doing so allowed the agency to hire any qualified applicant where there is a severe shortage of candidates or when there is a critical hiring need without regard to certain hiring rules and procedures. SSA reported that the direct hiring authority helped the agency hire over 7,800 employees in fiscal year 2023, for a net addition of around 3,150 additional employees when factoring in attrition.

Further, SSA officials told us that the availability of telework was key for their related recruiting efforts. They cited their review of fiscal year 2023 new hire survey results, which found more than half of new employees indicated that telework was a very important factor in applying for and accepting a position with the agency.[37]

These results are in line with group interviews we conducted from August 2024 through January 2025 with front-line staff who told us that telework availability was important in their decision to work at SSA. Staff in the south Florida area told us that telework was particularly attractive for prospective candidates given substantial traffic and related commuting time issues. Managers at the time told us candidates routinely expected telework availability, which can be a factor in their decision to take a job with the agency.

Retention. We found that SSA is at risk of losing many staff in the near term, in part because SSA employees are seeking greater telework flexibility. In 2024, around 37 percent of SSA respondents to the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey indicated they planned to leave the organization within a year. Specifically,

· 21 percent planned to leave to take another job in the federal government;

· 6 percent planned to retire;

· 6 percent planned to leave for other reasons; and

· 4 percent planned to take a job outside the federal government.

However, among those survey respondents stating that they planned to leave in the next year, almost half indicated that their respective work units’ telework or remote work options influenced their intent to leave the organization. SSA officials told us these staff were likely considering leaving for more telework or remote work opportunities, citing employee exit survey results and anecdotal discussions with managers. SSA field office staff agreed, and noted certain types of employees would be most likely to leave the agency for better telework options, specifically:

· newer employees, because they have experience working effectively in a hybrid environment and expect to be able to work from home regularly; and

· retirement-eligible employees, who had continued working in part because telework helps them avoid stressful commutes.

As a result, SSA was at risk of skills gaps in key occupations.[38] Skills gaps, if not effectively managed, could exacerbate long-standing problems the agency has had with service delays and backlogged workloads, especially in managing disability claims.[39]

These risks come at a time when SSA is seeking to substantially reduce the size of its workforce. In February 2025, SSA announced that it was seeking to improve efficiency and cut costs by reducing its agency head count to 50,000 employees.[40] This would be a reduction of around 7,000 employees. SSA is also undertaking initiatives that could affect its need for staff. For example, in November 2025, the SSA Commissioner announced that the agency was undertaking efforts to improve its phone, online, and in-person services through expanded use of technology.

We previously reported that it is critical for agencies to carefully consider how to strategically downsize their workforces and maintain the staff resources to carry out their missions before implementing workforce reduction strategies.[41] It is important that SSA take this step and develop a clear human capital plan that addresses its human capital risks, including substantially lower staffing levels, increasing workloads, and other previously-discussed risks to employee retention in mission-critical occupations.[42]

SSA officials said the agency has a human capital plan it can update to help guide staffing decisions, but has not done so because relevant staff are focused on changing its recruiting and hiring practices in response to administration and OPM new workforce priorities such as implementing skills-based hiring “to ensure candidates are selected based on their merit and competence.”[43] However, without a plan that helps the agency manage its mission needs while addressing attrition and planned workforce reductions, SSA lacks information on how many and what types of employees it will need to hire and retain to address mission priorities—including the disability backlog—and how it will strategically use its workforce to best provide timely services to the millions of Americans who seek its assistance each year. As a result, it may lack the information needed to ensure it has the mission-critical staff necessary to provide timely service to the public.

Employee engagement. Employee engagement—an employee’s satisfaction, commitment and willingness to put in discretionary effort—declined at SSA from 2021 through 2023 and improved in 2024, while most SSA staff regularly teleworked during the four-year period.[44] According to SSA, employee perception of workload contributed to lower engagement scores prior to 2024. However, field office staff, including some who chose not to telework regularly, told us they considered telework availability to be an important benefit.

Training. With the increased use of telework in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, SSA transitioned to virtual training for employees until staff began returning to the office in March 2022. SSA staff told us that since that time, they took training at an office location and had in-person access to mentors to assist with on-the-job training. SSA did not allow new employees to telework until they met minimum competency requirements through various training in their respective areas of expertise, a process that usually took 6 to 8 months to complete.

Virtual communication technology. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, SSA introduced initiatives and tools to help staff access information remotely and enhance customer service delivery. As a result, SSA staff were better positioned to work from home than prior to the pandemic.

For example, SSA scheduled telephone appointments that staff could take while working from home and expanded virtual services to provide customers with options to conduct transactions by video with SSA staff. According to SSA officials, in March 2024 the agency also eliminated the requirement for wet signatures on medical forms for disability claims, allowing individuals to affirm their identity and complete their initial claims interview over the phone with SSA staff. With increased availability of virtual services, SSA staff told us they could perform additional tasks while teleworking, such as responding to customer inquiries and processing online claims applications.

Customer Service: SSA officials cited other factors besides telework as contributing to increased claims processing time and walk-in customer wait times

Initial disability claims. As mentioned above, SSA has had long-standing struggles issuing timely disability decisions. This seemed to be exacerbated by the pandemic. The agency reported that the number of days to complete an initial disability claim increased each year from fiscal year 2019—before the COVID-19 pandemic—through fiscal year 2024. In fiscal year 2024, it took 231 days on average for SSA field offices to complete their processes for determining that claimants met nonmedical eligibility requirements for benefits, nearly double the number of days it took in fiscal year 2019 (120 days).[45]

Disability Determination Services (DDS) offices—state offices under contract with SSA that review initial claims received from SSA field offices and make medical eligibility determinations for disability claims—experienced high rates of attrition during and following the pandemic.[46] We previously reported that closures and staffing reductions at DDS state offices contributed to disability processing backlogs.[47] In response to the pandemic, in July 2020, almost all DDS offices reported their staff teleworked off-site.[48] DDS employees have since left to work for federal agencies that had similar work, but with higher pay and more telework options than what state offices offered them, according to SSA’s Major Management and Performance Challenges report for fiscal year 2024.[49]

SSA officials told us other factors, rather than telework, contributed to challenges in processing disability claims. These factors included

· a learning curve associated with the rollout of a new disability case processing system,

· a substantial increase in the volume of medical evidence provided by customers, and

· fewer medical providers willing or able to provide consultative exams following the pandemic. These exams helped SSA customers obtain medical evidence of their disability.

According to a SSA report, in 2024 the agency undertook a variety of initiatives—including increasing the competitiveness of DDS pay, streamlining training, and reducing the time it takes to onboard new hires—to help DDS offices recruit and retain employees and improve efficiency. As of May 2025, the agency had begun to reduce the number of disability claimants waiting for a decision. In a June 2025 statement to Congress, the SSA Commissioner said that the agency was creating and aligning new centralized divisions for making disability determinations, and staffing them with reassigned employees to assist states with the largest backlogs and wait times.[50] In addition, the Commissioner said that the agency was enhancing its Disability Case Processing System used by states. Further, as of November 2025, according to the Commissioner, the agency decreased initial claim average processing times by 13 percent—from 240 to 209 days—compared to January 2025.

SSA officials expected processing times, which remained high, to decline once the agency had cleared the oldest cases that came in during a pandemic-era spike in claims. However, we previously reported that without continued improvements to processing times, disability claimants will continue to face long wait times for SSA decisions on benefits that could be critical to their financial and physical well-being.[51]

Social Security card replacement. According to agency officials, an increasing percentage of card replacement requests through the agency’s my Social Security portal has contributed to SSA efficiency while in a telework posture. From March 17, 2020, until April 7, 2022, SSA offices were closed to the public in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and customers were encouraged to use online services for card replacement requests. The internet option is fully automated and does not require staff intervention, allowing customers to complete their requests without visiting a field office or interacting with an employee. As shown in table 7, while most replacement cards continued to be processed at a field office location, requests via the online portal became an increasingly popular option from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024, with internet-based requests rising by 68 percent over this period. Notably, even after field offices reopened to the public in April 2022, the number of internet applications remained higher than prepandemic levels, indicating a sustained shift in customer preference and agency operations.

|

Enumeration method |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Percentage change from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 |

|

Field office |

10,758,722 |

6,048,334 |

3,768,581 |

6,979,666 |

8,626,597 |

8,175,501 |

-24% |

|

Internet |

1,345,321 |

2,014,493 |

3,140,972 |

3,003,949 |

2,311,381 |

2,256,717 |

68% |

|

Total |

12,104,043 |

8,062,827 |

6,909,553 |

9,983,615 |

10,937,978 |

10,432,218 |

-14% |

Source: GAO analysis of Social Security Administration data. | GAO‑26‑107645

Field office services. SSA officials told us that in 2024, the agency began requiring appointments for in-person services at field offices. Agency officials said this change made scheduling telework easier because foot traffic was more predictable. However, they also said staffing shortages continued to cause longer than desired wait times.

We observed some instances of issues stemming from staffing problems during our site visits in August 2024 and January 2025.

· In Alaska, SSA officials told us that customers had longer wait times than in the past because there were more eligible recipients for service while the office had substantially fewer staff. One office had fewer than 10 staff in 2024 compared with around 50 in 2007, according to a SSA official. Another field office in Alaska did not open on the day we visited because the two employees who were supposed to be there were both on sick leave.

· In south Florida, some customers without appointments had wait times of more than an hour, according to SSA officials. Agency officials told us they continue to accept walk-in customers, especially people experiencing homelessness, those with disabilities, and other people needing specialized or immediate attention. The officials stated as of January 17, 2025, that they had the discretion to cancel telework days for staff when other staff that were scheduled to be in the office called out sick so that they would have enough coverage for both appointments and walk-in traffic.

SSA Has Taken Steps to Implement Key Telework Practices, but Has Not Evaluated Its Telework Program to Determine Its Effects and Identify Problems

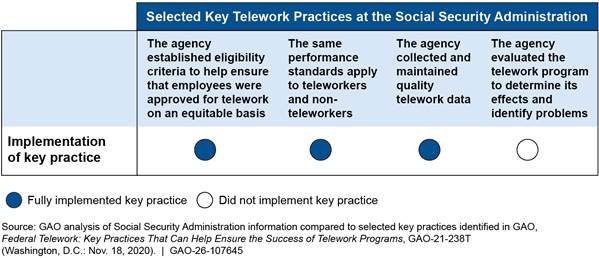

We found that SSA has taken steps to implement key practices for successful telework programs. The agency established telework eligibility criteria on an equitable basis, and ensured that the same performance standards were used to evaluate both teleworkers and non-teleworkers. SSA also started collecting and maintaining quality telework data beginning in fiscal year 2024. See figure 7. Appendix II includes information on how SSA fully addressed these practices.

Figure 7: Social Security Administration Telework Program Alignment with Selected Key Practices for Implementation of Successful Federal Telework Programs

Note: We selected the key practices listed in the table because we determined they were most relevant to agencies that have established telework programs and have used telework for several years, such as those in our review.

SSA had not taken steps to fully evaluate its telework program to understand its effects and identify problems, which is a key practice for implementing a successful telework program.[52] SSA officials told us the agency had not evaluated telework’s effects, in part, because they believed it would have been costly and complicated. However, we reported in November 2024 that the Veterans Benefits Administration had determined feasible ways to evaluate its telework program, including

· determining if the agency’s telework program complied with applicable laws, regulations, and policies, and whether internal controls were adequate for managing the program; and

· identifying new and existing performance measures that could be affected by telework—such as the number of cases closed, claims processed, applicants for job announcements, employee engagement scores, and quit rates—and setting targets for each measure.[53]

Without evaluating the telework program, SSA lacks the information needed to identify any problems or issues with the program and make appropriate adjustments.

Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs

Table 8: Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs Telework Implementation and Performance at a Glance

|

Highlights Bureau of Consular Affairs (CA) staff rarely teleworked before and after the President’s January 2025 memorandum that required most employees to work at an office location. Telework likely did not affect passport processing times. · Agency operations: CA officials said the agency lost staff to other agencies with more telework. · Customer service: Other factors besides telework contributed to substantial passport processing time increases in 2020 and 2023. CA had taken steps to implement key telework practices, but had not evaluated its telework program to determine its effects and identify problems. |

Source: GAO analysis of State information and interviews with Department of State and CA officials. | GAO‑26‑107645

Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs Background

Part of the mission of the Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs (CA) is to protect the lives and serve the interests of U.S. citizens abroad. It does so, in part, by providing passport services to help enable citizens to travel to foreign territories and providing access to U.S. consular services and assistance while abroad.

According to State officials, as of April 2025, 175.9 million Americans—or 51.5 percent of the U.S. population—held a valid U.S. passport. As of May 2025, according to CA officials, U.S. citizens can apply for their passports at one of the 27 public-facing domestic passport agencies and centers or at one of the 7,400 public-facing passport acceptance facilities located throughout the U.S. They can also apply for new or renewed passports through the mail or apply for routine passport renewals online. CA measures its success in providing passport services by tracking the time needed to process both routine and expedited passport requests.

CA Staff Rarely Teleworked Before and After the President’s January 2025 Memorandum That Required Most Employees to Work at an Office Location

OMB and OPM directed agencies to revise their telework policies following the President’s Return to In-Person Work memorandum, and to provide timelines for the return of all eligible employees to in-person work.[54]

In response, State sent OMB and OPM an implementation plan to return employees to offices. The plan states that all regularly scheduled telework was to be canceled by February 28, 2025, except for those employees with specified exemptions to include reasonable accommodations, some spouses of military service and Foreign Service members who are overseas, and other legal requirements such as settlement agreements. State generally required all staff with telework arrangements to report for full-time in-person work by March 1, 2025.

State’s “return to office” implementation plan stated the agency planned to review collective bargaining agreement language on telework to determine if any provisions are unenforceable for conflicting with management’s statutory rights under the Federal Service Labor-Management Relations Statute. State officials told us they subsequently determined that the agency was not prohibited from requiring staff to return to the office full time. They also said they notified three unions of the “return to office” implementation plan in February 2025.

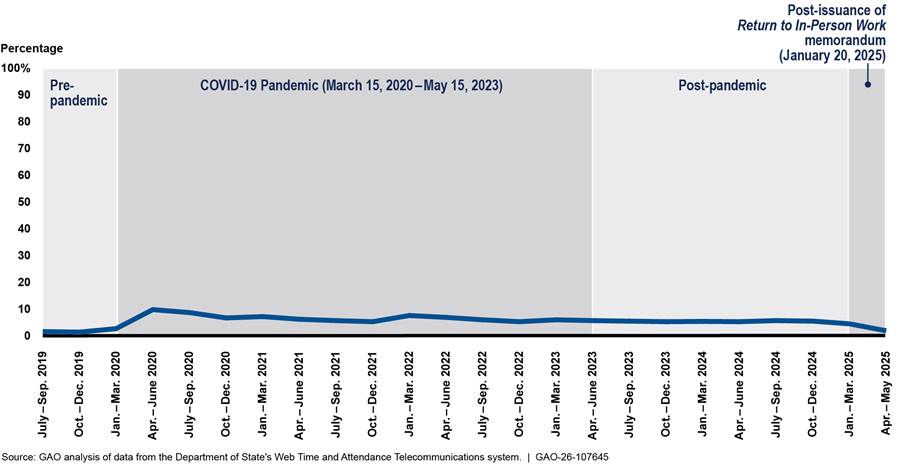

However, CA staff—including staff providing passport-related and other services—did not frequently telework before the Return to In-Person Work memorandum. CA’s telework use ranged from 5 to 7 percent of total work hours from October 2020 through December 2024, before decreasing to 2 percent of total work hours in April-May 2025. Prior to the pandemic in December 2019, telework hours at CA were 1 percent of total work hours. CA’s telework use peaked at 10 percent of total work hours during the period of April through June 2020, after federal agencies were required to maximize telework use due to the pandemic. See figure 8.

Figure 8: Percentage of Hours Worked in Telework Status at the Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs, July 2019-May 2025

Notes: The start date of the COVID-19 pandemic period in this graphic is March 15, 2020, when the Office of Management and Budget issued guidance to federal agencies in the National Capital Region stating that they should provide maximum telework flexibilities to employees. The end date is May 15, 2023, the effective date of termination of maximum telework as part of the federal government’s operating status, in accordance with the Office of Personnel Management’s guidance. The Department of State’s Comptroller and Global Financial Services did not have data on hours teleworked during 2020 pay period 21 (October 11-24, 2020) and 2021 pay period 4 (February 14-27, 2021).

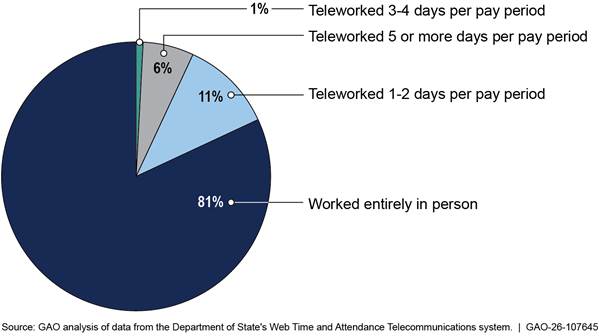

We found that during a pay period in December 2024, before the issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum, 81 percent of CA staff did not telework. Of those employees who did, most teleworked 1-2 days per pay period. See figure 9.

Figure 9: Status of Telework and In-Person Work at Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs During 2024 Pay Period 24 (December 1-14, 2024)

Notes: Telework data from individual employees rounded to the nearest whole employee. The data are not generalizable to all pay periods or illustrative to time spent teleworking across time.

CA passport specialists had more telework restrictions than other CA staff. In January 2025—before agency employees were required to work in person at office locations full time—telework was limited to 1 day per month for passport specialists, according to CA officials. These specialists needed to be at processing centers to meet with customers and handle physical documents that were not available virtually. According to CA officials, the specialists typically spent their monthly telework day catching up on training and administrative requirements.

CA officials we spoke with said that program managers supervising passport processing centers were able to telework more often because they did not routinely meet with the public and could securely access agency tools and electronic files from their homes. Managers we spoke with at one passport processing center told us they coordinated to ensure there was sufficient in-person supervision of processing specialists on days when a manager was scheduled to telework.

Because most CA staff were not regular teleworkers, return-to-office requirements did not significantly change where they did their work. We found the percentage of CA staff who worked entirely in person increased from 81 percent in December 2024 to 94 percent by March 2025. Of those employees still teleworking in March and April of 2025, most did so 1 or 2 days per pay period. Situational telework is still permitted, according to State’s return to office implementation plan.

Telework Likely Did Not Affect Passport Processing Times

Agency Operations: CA officials said the agency lost staff to other agencies with more telework

Recruiting and retention. CA officials told us that telework was not a high priority for passport specialist candidates considering work with the agency, given that the job description was clear that most work needed to be done in an office location. However, in January 2025—before the President’s issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum—they told us that telework availability was important to employee retention at CA. Managers at one CA location told us at that time that their office experienced significant turnover in recent years because CA employees found work at other area federal agencies that provided more telework opportunities.

A 2022 State employee survey found that telework, remote work, and other workplace flexibilities were very important or important to 89 percent of civil service respondents, which included passport specialists. Similarly, a lack of workplace flexibilities—especially telework and remote work—were among the top write-in answers to a question on the factors that would cause a respondent to leave State.

Employee engagement. Before the President’s January 2025 issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum, CA officials told us that even the limited amount of telework available to employees had some benefit. CA officials we spoke with said that, based on their observations, telework use likely contributed to improved employee satisfaction and engagement. They added that because teleworking allowed passport specialists to catch up on training and administrative requirements from home, their productivity increased as they could focus on their core duties when in the office. In 2024, State’s Foreign Affairs Manual also said that telework enhanced morale.[55]

Use of technology to facilitate processing of renewal applications while teleworking. Before the January 2025 issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum, CA officials noted that State’s Online Passport Renewal initiative could have facilitated telework by enabling passport specialists to process and adjudicate renewal applications from home, including during office emergencies or other circumstances when staff must telework situationally.

Customer Service: Other factors besides telework contributed to substantial passport processing time increases in 2020 and 2023

We found that regularly scheduled telework likely did not affect passport processing times. As previously discussed, passport specialists were eligible to telework only 1 day per month. In addition, contractors who produced the physical passports did not telework.

We identified other factors that caused spikes in processing times in 2020 and 2023, respectively.

· The processing of passports in June 2020 took 2 to 3 times longer than in June 2019.[56] State officials told us that they reduced staff’s physical presence at passport agencies for health and safety reasons. Because the passport adjudication process was paper based and had to be done at an office location, teleworking staff were not able to process passport applications.

· The processing of passports took 2 to 4 weeks longer on average in May-July 2023 than in May-July 2022.[57] We previously found that an unexpectedly large volume of applications, high rates of staff attrition related to overtime requirements, technology problems, and other issues unrelated to telework compounded the delay of passport processing and led to a substantial backlog. State implemented short-term measures to mitigate the backlog in fiscal year 2023, such as requiring overtime and mandating that other CA staff adjudicate applications.

· The time spent processing passports decreased substantially in fiscal year 2024 to a monthly average of 2.7 weeks for routine applications (compared to 8.2 weeks in fiscal year 2023) and 1.2 weeks for expedited applications (compared to 4.7 weeks in fiscal year 2023). CA officials credited several factors for the shorter average processing times, including more staff, fewer applications, and fewer requests for expedited processing. The officials stated the agency also streamlined the passport adjudication process, which they said reduced time-consuming follow-up with customers.

In March 2025, we reported that State is developing long-term plans, laid out in a Transformation Roadmap, for projects to modernize passport processing. According to State officials, the Transformation Roadmap identified, as of November 2024, more than 83 related projects. We recommended that State (1) define milestones and (2) determine the resources needed to successfully implement the Roadmap.[58] State agreed. Taking such actions would better position State to reduce the likelihood of future delays in passport processing and their negative effects on U.S. travelers and the travel industry. In July 2025, we reported that State’s centralized customer service call center, the National Passport Information Center (NPIC)—which answers general questions about passports and provides passport application assistance—has taken steps to address factors that affected call volume needs since a fiscal year 2023 call surge.[59] These included increasing NPIC’s call agent staffing levels, adding approximately 7,000 phone lines, and providing training to improve call agents’ skills.

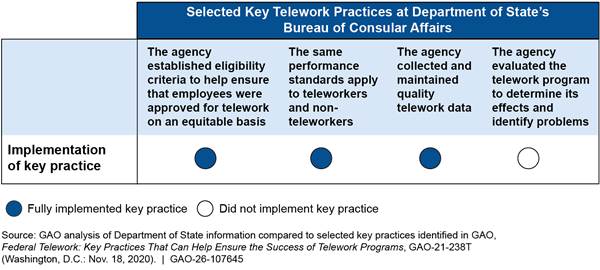

CA Had Taken Steps to Implement Key Telework Practices, but Had Not Evaluated Its Telework Program to Determine Its Effects and Identify Problems

State and CA fully addressed key practices for establishing telework eligibility criteria on an equitable basis and ensuring the same performance standards were used to evaluate both teleworkers and non-teleworkers. It also had processes and procedures to collect quality telework data. See figure 10. Appendix II includes information on how CA fully addressed these practices.

Figure 10: Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs Telework Program Alignment with Selected Key Practices for Implementation of Successful Federal Telework Programs

Note: We selected the key practices listed in the table because we determined they were most relevant to agencies that have established telework programs and have used telework for several years, such as those in our review.

However, State officials told us they had not conducted any agencywide or bureau-specific assessment of State or CA’s telework program, nor had they evaluated the effects of telework prior to the general elimination of routine telework in March 2025. A key practice for successfully implementing a telework program is to evaluate the program to identify problems or issues and to make appropriate adjustments.[60] Officials told us they have not been required to assess State or CA telework programs. Without telework evaluations, State and CA lacked information agency officials needed to identify and address problems with the telework program, and more fully leverage any benefits.

As we discussed earlier, CA’s telework use declined since the January 2025 issuance of the Return to In-Person Work memorandum. Almost all CA staff worked in person by March and April of 2025, resulting in lower levels of telework compared to before the memorandum’s issuance. Therefore, we determined it is not practical for State to evaluate its telework program given its current use and given the administration’s current telework policy.

Conclusions

BIA, SSA, and CA shared some common characteristics in their telework programs. Each had

· decreasing use of telework following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic,

· staff recruitment challenges and employees who had left or considered leaving for other organizations with more telework availability, and

· declining performance in some key customer services, where factors other than telework use primarily contributed to these declines.

There are unique circumstances at each agency, however, that influence how they need to address telework-related challenges.

BIA, for example, can address long-standing recruiting and retention challenges—which may have been exacerbated by limited telework availability—by addressing the recommendations we made in November 2024.[61] These actions remain necessary to ensure the agency can improve its workforce capacity given that it can no longer offer routine telework as an incentive, and has a growing backlog in processing probate cases. We determined it is not practical or useful for BIA to evaluate its telework program at this time given its current use is negligible.

SSA needs an updated human capital plan that guides actions the agency can take to identify and retain mission-critical staff. This plan is particularly important because regular telework is no longer available to most SSA staff, and agency decision-makers are also considering major reforms to reduce costs in part through workforce reductions. Without such a plan, SSA is at serious risk of skills gaps in mission critical occupations, which will affect the agency’s ability to deliver services to people seeking disability benefits, among others.