TRANSFORMING AVIATION

FAA Planning Efforts Should Address

How Drones Will Communicate with and Avoid Other Aircraft

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: collinsd@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is working to further enable drone operations such as drone delivery. Currently, drone operators must obtain a waiver or exemption from FAA to fly beyond their visual line of sight and show, among other things, how they will detect and avoid other aircraft. Existing technologies that can be used for that purpose include those that use GPS, sensors, or radar. Specifically, drones can use Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) to detect and avoid manned aircraft that use ADS-B to broadcast their position information using GPS. Camera or acoustic sensors, or ground radar, can also be used to detect aircraft that are not broadcasting. FAA-approved waivers have mostly relied on ADS-B, which drone stakeholders said is more effective than sensors or radar. Some stakeholders said that using other technologies with ADS-B could be a safer option but presents challenges such as increased weight, affecting safety.

FAA envisions a future National Airspace System (NAS) that is information-centric, where all airspace users, including drones, share location information electronically. According to FAA, limitations with existing technologies require the development of a new technology that, unlike ADS-B, enables two-way communication between drones and other aircraft. FAA officials said it intends to develop performance-based standards and safety requirements for industry to use in developing that technology. In August 2025, FAA proposed new regulations that would require drones flying beyond visual line of sight of the operator to detect and avoid other aircraft. However, FAA has not identified specific actions such as clear roles or technical milestones timelines, which could help FAA and industry move toward two-way communication between drones and other aircraft. Congress tasked FAA with the responsibility to develop an information-centric NAS and develop an integrated plan for the future NAS by May 2027. Developing specific actions could build upon FAA’s drone integration efforts and help ensure safety for all airspace users in the future NAS.

Why GAO Did This Study

Drones are the fastest-growing segment of U.S. aviation, according to FAA. In 2025, FAA forecasted that the commercial drone fleet would exceed one million by the end of 2025 and grow to 1.18 million by 2029. Operators are starting to use drones for activities including package delivery and public safety. With increasing drone activity, there are growing concerns about potential collisions between drones and other aircraft.

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 requires GAO to review technologies for drones to detect and avoid manned aircraft at low altitudes. This report examines technologies available for drones to detect and avoid manned aircraft, stakeholder perspectives on these technologies; and FAA’s plans for drone operations in an information-centric NAS.

GAO reviewed FAA documents related to integrating drones into the national airspace, including documents related to detect and avoid technology. GAO interviewed FAA and 24 stakeholders from industry and government. GAO focused on small drones (defined as those weighing less than 55 pounds) because they fly at low altitude and provisions for this review in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 specified that GAO focus on low-altitude airspace.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to FAA to develop and begin implementing specific actions, including establishing clear federal and nonfederal roles and technical milestones, to ensure that drones can communicate with and detect and avoid other aircraft within an information-centric NAS. The Department of Transportation concurred with this recommendation.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ACAS |

Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

|

ADS-B |

automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast |

|

AGL |

above ground level |

|

ATC |

air traffic control |

|

BVLOS |

beyond visual line of sight |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

|

FCC |

Federal Communications Commission |

|

FL |

flight level |

|

NAS |

National Airspace System |

|

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

NEXTGEN |

Next Generation Air Traffic Modernization |

|

NPRM |

notice of proposed rulemaking |

|

NTSB |

National Transportation Safety Board |

|

MSL |

mean sea level |

|

RTCA |

Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics |

|

TABS |

Traffic Awareness Beacon System |

|

TSO |

technical standard order |

|

UAS |

unmanned aircraft system |

|

UTM |

UAS traffic management |

|

VFR |

Visual Flight Rules |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 4, 2026

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

Drones are the fastest growing segment of U.S. aviation, according to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). In 2025, FAA forecasted that the commercial drone fleet (those operated in connection with business, research, or educational purposes) would exceed 1 million by the end of 2025 and grow to 1.18 million by 2029. For the same period, FAA forecasted that the recreational fleet (those operated for personal interest and enjoyment) would increase from 1.87 million to 1.93 million. The projected growth in the commercial drone fleet is driven, in part, by interest among companies and other organizations in using drones for advanced and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations, such as package delivery.[1] Public safety organizations are also interested in increasing drone use for operations such as disaster management, law enforcement surveillance, and hazmat situations. With increasing commercial and public safety drone activity, there are growing concerns among some aviation stakeholders about the potential for collisions between such drones and other aircraft flying in the same airspace.

FAA generally requires manned aircraft to have automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) equipment when operating in specified volumes of controlled airspace.[2] This technology broadcasts information about an aircraft’s GPS location, altitude, groundspeed, and other position data, making the aircraft “electronically conspicuous”—or detectable—to other aircraft in the vicinity if those aircraft are also equipped with such technology.[3] Certain aircraft are not required to have this technology, such as those not originally certificated with an electrical system (e.g., gliders and balloons), or those exclusively operating at low altitudes outside of the airspace in which this technology is required (e.g., crop dusters and some helicopters). In addition, FAA generally prohibits or otherwise limits certain drones from using this technology to broadcast their location.[4] Drone operators can, however, use other detect and avoid technologies that include the transmission and reception of broadcast position data, designed to help prevent conflicts of low-altitude air traffic. In August 2025, FAA proposed performance-based regulations to enable the design and operation of drones at low altitudes that are flying BVLOS.[5] According to FAA, this proposed rule is necessary to support the integration of drones into the national airspace.

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 includes a provision for us to review technologies[6] for drones to detect and avoid manned aircraft operating at low altitudes.[7] Our report examines:

1. the technologies that exist for drones to detect and avoid low-altitude aircraft that may or may not broadcast position data;

2. views of selected aviation stakeholders on the effectiveness of existing drone technologies to detect and avoid other low-altitude air traffic; and

3. efforts that FAA has underway related to drone detect and avoid technology and actions that could be taken to inform future planning activities.

For these objectives, we reviewed agency documents related to drone detect and avoid technologies, electronic conspicuity, and ongoing efforts. Specifically, we reviewed current FAA regulations on relevant technologies and equipage requirements for the different classifications of airspace and our prior work on FAA’s efforts to integrate drones into the national airspace. We interviewed 25 aviation stakeholders to discuss available detect and avoid technologies in drone operations and electronic conspicuity, their experiences using these technologies, and FAA initiatives related to these efforts. We selected these stakeholders based on our prior work, provisions for this review in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024,[8] reviews of relevant literature, and involvement in the BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee.[9] See appendix II for a list of stakeholders we interviewed. We focused on small drones because they fly at low altitude and provisions for this review in the FAA Reauthorization of 2024 specified that we focus on low altitude airspace.[10] In addition, discussions with stakeholders indicated smaller drones have a greater risk of collision because they are harder to see. We also interviewed officials from the Department of Transportation (DOT) and FAA.

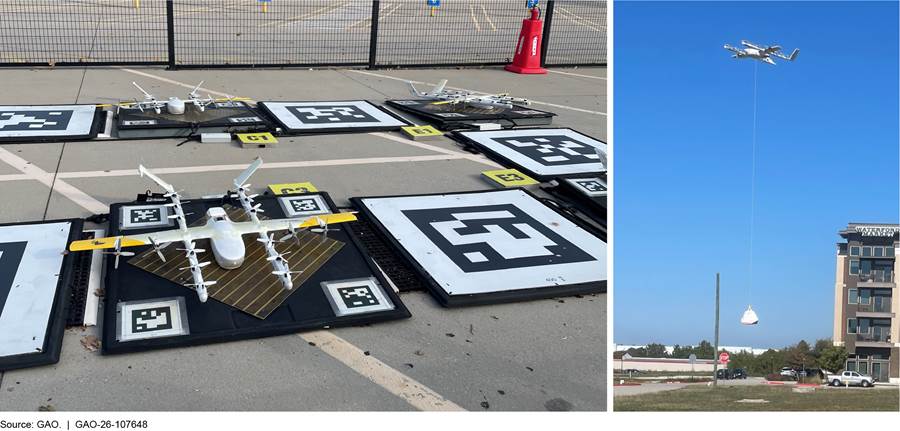

We also conducted a site visit to the “North Texas Operational Evaluation,” the location of a collaborative effort between the drone industry and federal agencies in the Dallas-Fort Worth area to develop and test drone traffic management services. During the site visit we met with representatives from a company that is using drones for deliveries and a local law enforcement entity that uses drones for public safety. We discussed their respective drone operations, FAA’s involvement in the commercial drone industry’s efforts to facilitate BVLOS operations, and drone integration in the national airspace.

For the first objective, we interviewed relevant aviation organizations described above and conducted a literature search to identify technologies available for drone detection and avoidance and electronic conspicuity. We also interviewed relevant FAA officials about their process for assessing waiver applications that drone operators must submit to fly BVLOS under current FAA regulations. In addition, we reviewed FAA approved waiver application data to identify the technologies drone operators use to fly BVLOS. We reviewed our prior work related to drone integration and the waiver process.[11] We interviewed FAA officials regarding their ongoing BVLOS rulemaking efforts and testing of electronic conspicuity devices. In addition, we interviewed FAA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and DOT officials to discuss ongoing research on technologies that can be used in future drone operations and reviewed their waiver findings.

For the second objective, we analyzed stakeholder comments from our interviews to identify common themes expressed by general aviation, drone, avionics manufacturers, and research stakeholders on the ability of these technologies to help drones avoid manned aircraft. Not all stakeholders we interviewed had opinions on all topics discussed.[12] Because we selected a nongeneralizable sample of stakeholders, their responses cannot be generalized to all general aviation, drone, and research stakeholders. We also reviewed documents from general aviation stakeholders, such as relevant studies on how operators use technologies for drone detection and avoidance and electronic conspicuity and letters to FAA on concerns related to drones flying BVLOS and their ability to use technology to detect manned aircraft.

For the third objective, we reviewed FAA’s planning documents for the future of the National Airspace System (NAS) to identify the agency’s plans related to detect and avoid technology for drones and electronic conspicuity in the NAS. These documents included FAA’s Charting Aviation’s Future: Operations in an Info-Centric National Airspace System and other related documents.[13] We also reviewed requirements in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 for FAA to develop an integrated plan, including a roadmap, for the future state of the NAS by May 2027.[14] In addition, we reviewed a June 2025 executive order on requirements to publish an updated roadmap to integrate drones into the national airspace.[15] We also reviewed FAA’s August 2025 notice of proposed rulemaking, Normalizing Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Operations.[16] We compared FAA’s efforts related to detect and avoid technology for drones, electronic conspicuity, and the future information-centric NAS to the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government principle related to, among other things, responding to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[17]

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to February 2026, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

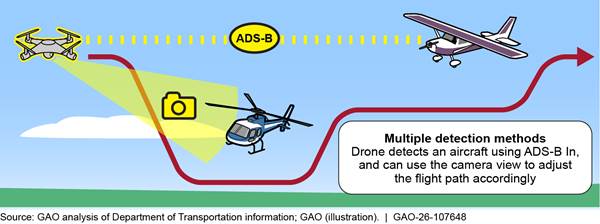

The commercial and public safety use of drones can provide significant social and economic benefits. As shown in figure 1, drone operations are used in various areas such as public safety, agriculture, and package delivery. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, drones were used for a broad range of tasks where social-distancing measures were in place including contactless distribution of personal protective equipment and delivery of testing and medical supplies to hospitals. While conducting these operations, drones may encounter manned aircraft, introducing the potential for a mid-air collision.[18]

Anyone flying a drone is responsible for following applicable provisions in, for example, statutes, guidelines, regulations, notices, and special flight rules. According to FAA, its current small drone operational regulations in Part 107 cover a broad spectrum of commercial and government uses. These Part 107 regulations require such drones to yield the right of way to all other aircraft. According to stakeholders we interviewed, these other aircraft may include helicopters, small planes, gliders, and crop dusters that frequently operate at altitudes below 500 feet, in the same airspace as drones. Drones are subject to many types of airspace restrictions, including near stadiums during certain sporting events, airports, security sensitive areas, and in the Washington, D.C. area, among others. FAA regulations currently require that drones must be operated within the visual line of sight of the operator such that the operator knows of the drone’s location, altitude, and direction of flight. In addition, the operator is required to observe the airspace for other air traffic or hazards to determine that the drone does not endanger the life or property of another.[19] However, FAA has the authority to issue a waiver of these regulations if it finds that a proposed drone operation can be safely conducted under the terms of that certificate of waiver.[20]

As more Part 107 non-recreational operators are interested in pursuing advanced operations,[21] the operators have the option to apply for a Part 107 waiver to be able to fly BVLOS for some operations.[22] As part of this Part 107 waiver process, operators must provide details on how they would detect and avoid other aircraft when flying BVLOS. In August 2025, FAA proposed new regulations for drone operators flying BVLOS and sought comments by October 6, 2025. The proposed rule is intended to provide a predictable and clear pathway for safe, routine, and scalable drone operations that include, among other things, package delivery, agriculture, and aerial surveying.

FAA’s mission is to ensure the safety and efficiency of the NAS. At the time of our review, the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration Office, Flight Standards Services, and Aircraft Certification Service within FAA’s Office of Aviation Safety had key responsibilities related to drone detect and avoid technologies. In addition, FAA works with various state and local government organizations, research groups, and drone industry stakeholders on research related to this area.

FAA is collaborating with industry and government partners to develop a traffic management system for unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). The UAS traffic management (UTM) ecosystem involves developing a framework of interconnected systems for managing multiple drone operations. Under UTM, FAA would first establish rules for operating drones, and drone industry operators would then coordinate the execution of flights with third party service suppliers that help operators manage risk.[23]

Various Technologies Exist for Drones to Detect and Avoid Aircraft Using GPS, Cameras, Acoustic Sensors, and Radar

Drone operators might use a range of existing technologies to detect and avoid low-altitude aircraft.[24] Specifically, nearly all stakeholders we spoke to identified ADS-B, cameras, and acoustic sensors, or ground radar as technologies available for drone operators to detect and avoid aircraft. While the available technologies can be used to detect other aircraft, they require the drone operator to manually avoid the aircraft based on the information provided from the technology. Some drones also have software that can take the input from a sensor and autonomously maneuver the drone away from another aircraft. As mentioned above, drones conducting more advanced operations may need to use detect and avoid technology that can detect other aircraft to be approved for a BVLOS waiver.

ADS-B. ADS-B is an advanced surveillance technology that enables air traffic controllers and aircraft operators, including general aviation aircraft or drone pilots, to get precise aircraft location data from GPS. Manned aircraft equipped with ADS-B Out broadcast location information, and other aircraft, including drones, can use ADS-B In technology to receive this location information.

· ADS-B Out. If an aircraft is equipped with this technology, it can broadcast information about its GPS location, altitude, velocity, and related data to other aircraft, such as drones. Any receiver in range can listen to the signal and obtain the transmission. This technology, which broadcasts once or more per second, offers more frequent tracking of aircraft compared to radar, which sweeps for position information every 5 to 12 seconds. While federal regulations generally require that aircraft equip with ADS-B Out and transmit in certain classes of airspace,[25] other federal regulations generally prohibit or otherwise limit certain drones from using ADS-B Out.[26] According to FAA officials, one of the reasons for this is because the projected numbers of drone operations have the potential to saturate available ADS-B frequencies, which can affect ADS-B capabilities for manned aircraft and create congestion for ADS-B ground receivers.(For specific details on ADS-B requirements, see appendix I.)

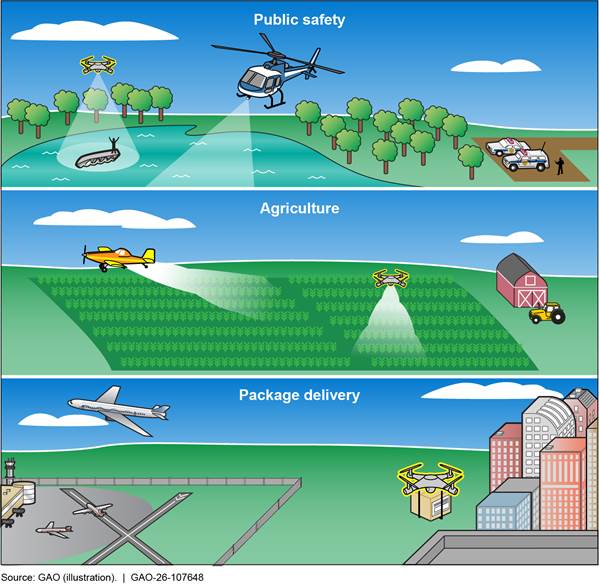

· ADS-B In. If a drone is equipped with this technology, a drone operator can immediately obtain an aircraft’s position information, altitude, and velocity broadcasted by that aircraft’s ADS-B Out. The drone can obtain this information using a receiver located on the drone or on the ground. For example, one commercial drone operator we met with has an operations center where staff monitor nearby aircraft using ADS-B In. As shown in figure 2, the drone operator can then direct their drones to avoid the aircraft detected by ADS-B In.

Figure 2: Drone Operators May Use Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) In Information to Avoid Manned Aircraft

However, some aircraft may be authorized by FAA to operate without broadcasting their position data. For example, even within controlled airspace, FAA may authorize aircraft performing sensitive government missions for national defense, homeland security, intelligence, or law enforcement purposes to operate while not broadcasting their ADS-B Out position data under certain specified conditions.[27] In addition, section 1046 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 prohibits FAA from requiring ADS-B Out equipment on some military aircraft, such as fighter and bomber aircrafts.[28]

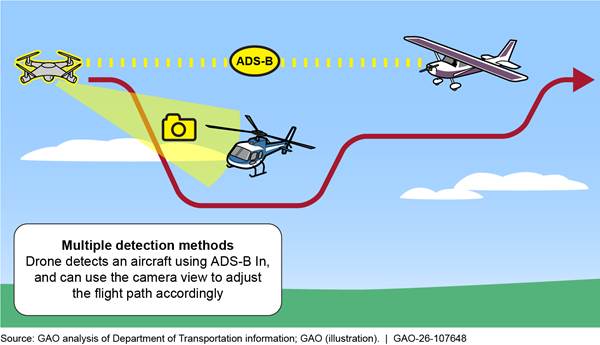

To ensure safety for both those broadcasting and not broadcasting position data, general aviation stakeholders we spoke to said in the current environment, it would be safest for drones to employ ADS-B plus another technology such as an acoustic sensor, camera, or ground-based radar.[29] The idea behind ADS-B “Plus” is that drone operators would use ADS-B In to detect aircraft that are broadcasting position data and use the additional technology to detect aircraft not broadcasting position data.

Some of the technologies drone operators can use to detect and avoid aircraft that may or may not be broadcasting position data are discussed below. As of December 2025, FAA had approved over 1000 waivers for BVLOS operations to companies, public safety organizations, and individuals. According to our analysis of BVLOS waiver applications, all the available technologies, including acoustic, camera, and radar technologies, have been approved by FAA for use by at least one drone operator or public safety organization. Most of the waivers, however, are for using ADS-B In as detect and avoid technology.

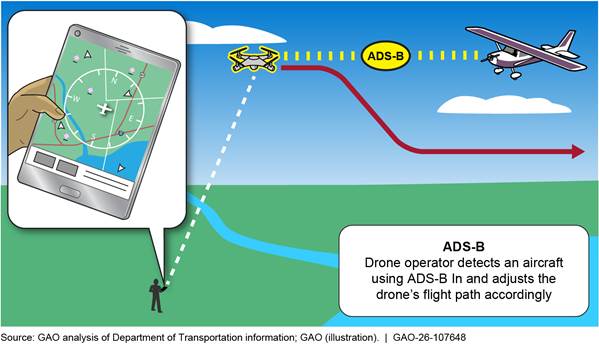

Cameras. Cameras can provide drones with a 360-degree view to detect other aircraft in the drone’s vicinity (see fig. 3). The cameras can be installed on the drone itself or mounted on a tripod on the ground. Some systems use multiple cameras aimed at different angles to provide wide-area coverage. According to an avionics manufacturer we interviewed, the use of cameras can be more effective than a visual observer at detecting aircraft that may be difficult to see visually.

Figure 3: Drone Using Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) In and a Camera to Detect Aircraft

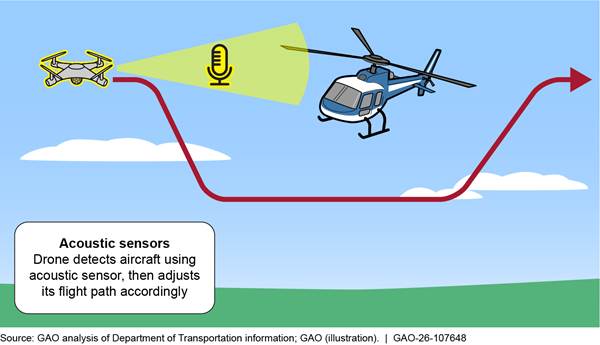

Acoustic sensors. This technology uses high sensitivity microphones coupled with audio analysis applications to detect, track, and identify sounds produced by aircraft, aircraft engines, and propellers (see fig. 4). The spinning of different types of propellers produces unique acoustic patterns, which makes it possible to create a library of the acoustic signatures to identify different types of aircraft and determine the general direction of the sound source. Acoustic sensors are best used in quiet and remote locations, according to stakeholders. One company we met with received FAA approval to use a combination of ADS-B In and acoustic sensors as a means for detect and avoid. This company’s drones have a detect and avoid system that can autonomously avoid other aircraft once the aircraft is detected by either ADS-B or acoustic sensors.

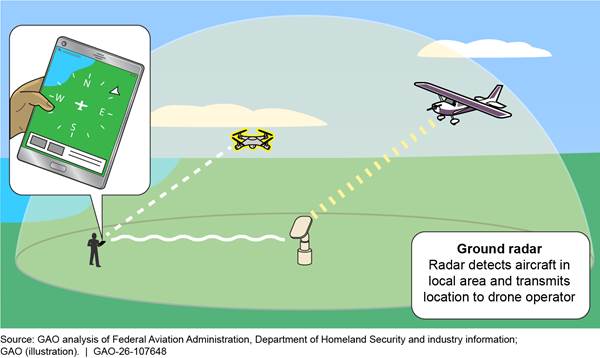

Ground-based radar. This technology operates by transmitting a radio signal of known frequency and power in a focused direction and then detecting the signal reflected from the target. Drone operators can detect other aircraft in the area by using aircraft traffic information from ground radars shown on a screen and maneuver the drone away from the aircraft (see fig. 5). Another stakeholder we interviewed received FAA approval to use a combination of ADS-B In and ground-based radar for detect and avoid activities.

Though not currently in use, according to FAA officials we interviewed, FAA has developed minimum performance standards for an electronic conspicuity technology called the Traffic Awareness Beacon System (TABS). Manned aircraft that are exempt from equipping with ADS-B Out are permitted to use TABS to broadcast the aircraft’s position information.[30] In concept, drones equipped with ADS-B In could detect aircraft that are equipped with TABS. However, according to FAA at the time of our work, no manufacturer has produced it in part due to costs associated with developing the technology.

In addition, Remote ID is a technology that drones currently use to broadcast their position information to other entities using radio signals, such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. FAA officials said Remote ID can be used by law enforcement to detect a drone and find its operator information, if needed, but it was not designed for manned aircraft to detect drones. One research stakeholder said operators could theoretically detect a drone when in range of the Remote ID signal, and the operator could maneuver to avoid it. The stakeholder studied the feasibility of using Remote ID broadcasts to enable manned aircraft to detect and avoid drones. The study found that Remote ID beacons mounted on drones vary greatly in their range and have different performance levels. For example, one beacon can have sufficient range for the manned aircraft to detect and avoid a drone, while another beacon that still meets FAA standards will only pick up a fraction of the range.

Drone stakeholders we interviewed for our June 2024 report on Remote ID technology also told us that a broadcast-based signal is not sufficient for providing real-time, networked data about a drone’s location and status, which is needed for advanced drone operations. At that time, FAA officials told us that at a future date FAA may begin assessing short- and long-term options for providing real-time data that could enable advanced operations, but there were no plans to do so. We recommended that FAA identify a path forward for how to provide real-time, networked data about the location and status of drones. This could include identifying and assessing short-term and long-term options and clarifying FAA offices’ roles and responsibilities. FAA agreed with our recommendation and, as of June 2025, was taking actions to address it.[31] This recommendation did not, however, address the ability of drones to detect and avoid other aircraft, including those that do not transmit location data.

Selected Stakeholders Identified Benefits and Challenges with Existing Detect and Avoid Technology Options

Drone stakeholders generally said that ADS-B In is currently the most effective technology for drones to detect and avoid aircraft that are broadcasting their position data. Drone stakeholders we spoke with said ADS-B In can detect aircraft at a far enough range to allow drone operators to avoid a collision. For example, one drone stakeholder said their drones can detect manned aircraft with ADS-B Out a few miles away, enabling them to adjust their flight path before they get too close to the manned aircraft. ADS-B In also receives information on the velocity and location of the aircraft, which drone stakeholders said can be helpful for the operator in deciding what avoidance maneuver to take.

Although general aviation stakeholders said ADS-B Out equipage can help drone operators detect and avoid other aircraft, there are challenges in getting all aircraft to equip with this technology.[32] General aviation stakeholders noted that they encourage their members to equip with ADS-B Out. However, they also discussed challenges related to equipping more aircraft with ADS-B Out. For example, one such stakeholder said pilots are concerned that FAA or law enforcement could use ADS-B Out to monitor violations of noise ordinances.[33]

In addition to these challenges, general aviation stakeholders noted that aircraft without an electrical system, such as gliders or ultralight aircraft, physically cannot install and operate ADS-B Out because they do not have an electrical system on board.[34] In August 2025, FAA proposed changes to the right of way structure in its notice of proposed rulemaking.[35] For example, manned aircraft broadcasting position information using ADS-B Out or electronic conspicuity equipment would have right of way over drones operating under the regulations, but such drones broadcasting their position would have right of way over manned aircraft not broadcasting position information. FAA plans to define new requirements for a portable low-cost electronic conspicuity device that could be used by manned aircraft operators solely to retain right of way over drones. In FAA’s notice of proposed rulemaking, FAA notes that this device would be usable in any manned aircraft without expensive installations or onboard electrical systems and invited comments on the best way to enable this type of technology.

Outside of equipage, some general aviation and research stakeholders and a DOT report noted that the effectiveness of ADS-B In for detecting and avoiding aircraft can be reduced in certain conditions. For example, these stakeholders said ADS-B does not work well at low altitudes where it cannot broadcast around hills. In addition, a November 2024 DOT research project noted limitations with ADS-B, including that data it broadcasts are unencrypted, which raises privacy concerns, and that saturation of the broadcast frequency can occur at higher aircraft densities.[36]

In a letter to FAA in 2023, general aviation stakeholders stated that they believe all drones should have technology that can detect both ADS-B Out equipped and non-ADS-B Out equipped aircraft. General aviation stakeholders we interviewed said one benefit of the ADS-B “Plus” approach (described above) is that it would be the safest approach to detect and avoid all aircraft, regardless of whether they are broadcasting their position data. FAA officials noted that with ADS-B “Plus,” the ability to use a second technology (e.g., camera or acoustic sensor or ground radar) can help in the event that one technology is unavailable or fails. For example, if an individual aircraft’s ADS-B fails, the operator could still detect aircraft in the area using another technology. Or if there is a broader problem, such as GPS spoofing or jamming, the other sensors would still be available to detect aircraft, according to FAA officials.

However, drone stakeholders we spoke with cited challenges to drones using such additional technology. For example, one drone stakeholder said adding technology such as acoustic sensors to drones can increase the size and weight of the drone. According to this stakeholder, doing so may reduce safety in the case of potential collisions with manned aircraft because a heavier aircraft is more dangerous in a collision.

Aside from weight and equipage challenges, research stakeholders we spoke with said that cameras and acoustic sensors may not be as effective as ADS-B. For example, acoustic sensors can pick up background noise such as wind or highway traffic. Camera sensors, according to one stakeholder, have difficulty differentiating aircraft from birds and may be impacted by clouds. In addition, another stakeholder indicated that ground radars can have a short range and cannot be moved easily, which would require operators to operate in one specific area. However, one public safety drone operator said that a benefit of ground-based radars over cameras or acoustic sensors is radar’s ability to operate 24 hours per day. In addition, the operator said that the technology works better at night than camera sensors.

FAA Has Ongoing Detect and Avoid Efforts, But Plans Include Few Details on How Drones Will Operate Within a Future Information-Centric NAS

FAA Is Developing Regulations That May Include Requirements for Drone Detect and Avoid Technology

FAA’s primary effort for advanced drone operations that could affect drone detect and avoid technology is an ongoing BVLOS rulemaking process that started in 2021. According to FAA, the purpose of the BVLOS rulemaking is to develop performance-based regulatory requirements to allow for safe, scalable, and economically viable drone BVLOS operations in the NAS. The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, enacted on May 16, 2024, required the FAA Administrator to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) no later than four months after the date of enactment (September 16, 2024) and a final rule on BVLOS operations for drones no later than 16 months after publishing the NPRM.[37]

To inform its rulemaking, FAA established a BVLOS advisory rulemaking committee, which published a final report in March 2022 with several recommendations for FAA to consider in the rulemaking process.[38] For example, the committee proposed mandating detect and avoid equipage for drones conducting BVLOS operations.[39] The recommendations to FAA also included modifications to right of way rules in acknowledgement that not all aircraft broadcast location information. Specifically, the committee recommended that such non-equipped manned aircraft would be required to yield the right of way to drones, and equipped aircraft would have right of way over non-equipped aircraft, regardless of whether the aircraft was manned or unmanned.[40] FAA told us that this recommendation does not account for limitations of (1) low-altitude aircraft that are not ADS-B equipped and (2) aircraft engaged in law enforcement or national defense missions authorized to operate with ADS-B Out disabled. FAA stated that the ability of these aircraft to give way presents a challenge to the effectiveness of the rulemaking committee’s recommendation.

In addition to the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 requirement for FAA to issue a proposed rule by September 2024 and then a final BVLOS rule 16 months after the publication of the NPRM, a June 2025 executive order required FAA to issue a proposed rule “enabling routine Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations for UAS for commercial and public safety purposes” by July 6, 2025.[41] To address these requirements, FAA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM), Normalizing Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Operations, on August 7, 2025, seeking comments by October 6, 2025. Until there is a final rule, according to FAA officials, FAA will continue its current approach of accepting and reviewing drone operators’ applications for waivers or exemptions to operate BVLOS.

FAA told us that the NPRM promotes, among other things, the use of electronic conspicuity by mandating Remote ID and detect and avoid technologies, which the agency stated will enhance safety, enable large-scale BVLOS operations, and ensure the integration of drones into the NAS. The NPRM proposes requirements for drone operators to be able to determine the geographic location and altitude of each unmanned aircraft at all times during flight operations and to maintain records of this information.

FAA and Industry Are Continuing to Research Other Technologies and Conduct Operational Evaluations

FAA, the DOT Highly Automated Systems Safety Center of Excellence, and others are researching additional technologies that could be used in the future to help detect and avoid aircraft at low altitudes and make more aircraft electronically visible (i.e., “conspicuous”).[42] For example:

· Portable ADS-B devices. The FAA Technical Center led some initial testing in 2024 to inform the BVLOS rulemaking.[43] FAA tested portable ADS-B devices in May and June 2024 since FAA did not want to impose an undue cost burden on crewed aircraft without electrical systems, according to an FAA whitepaper on this rulemaking. According to FAA officials, they anticipated portable devices could be made available at lower cost and potentially used either by general aviation operators who are not required, and have chosen not, to equip their aircraft with ADS-B Out or in aircraft without an electrical system. These officials said that if used, technologies designed to transmit an ADS-B signal could potentially make more aircraft that fly in low-altitude, uncontrolled airspace electronically conspicuous. FAA officials told us the FAA Technical Center and industry have tested prototype portable ADS-B devices that are lower weight and lower cost than those currently used. The officials noted that a final BVLOS rule intended to enable electronic conspicuity will promote additional industry technology solutions.

Most stakeholders we spoke with, and the advisory rulemaking committee report, were supportive of a low-cost, portable ADS-B device that would aid in detection and avoidance of these aircraft at low-altitude. FAA officials cautioned, however, that the devices are not currently approved for general use across all types of aircraft because portable devices are not installed in the aircraft. Additionally, some general aviation pilots also do not want to equip with ADS-B due to privacy concerns and because they can be tracked with ADS-B. In addition, these devices, according to FAA, do not meet the requirements for use in controlled airspace, and would require approval from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for use.

In August 2025, DOT provided us with a report on the results of the 2024 testing of portable ADS-B devices. According to the report, three major compounding factors will impact the signal strength of a position reporting device when it is operated within an aircraft cockpit: (1) location of the mounting point within the aircraft; (2) orientation in which the transmitting device is mounted; and (3) aircraft structure and configuration. The report notes that any one of these factors will cause a varying level of signal loss, but together, they can have a multiplicative effect.

· Cellular networks. DOT officials said the department developed a test and evaluation program to determine whether using cellular network technologies can, among other things, enable electronic conspicuity for all airspace users to ensure safe deconfliction of air traffic to meet the demands for scalable operations. Specifically, DOT provided information explaining that the department’s Highly Autonomous Systems Safety Center of Excellence (HASS COE) was to review, assess, and validate the capabilities of existing and emerging telecommunications technologies to future-proof visibility of aircraft positions, both manned and unmanned, beyond current ADS-B capabilities. DOT added that this review was intended to ensure airspace safety while enabling the integration of unmanned aircraft systems into the national airspace system. This would include, according to DOT, a government-led, industry-driven nationwide test of current and emerging cellular technologies. Further, DOT said that leveraging cellular networks could enable more widespread, lower cost, and more secure electronic sensing systems than other developing technology or methods could provide. According to a November 2024 white paper issued by HASS COE, FAA had previously entered into cooperative testing agreements with multiple operators to determine base level capabilities of the cellular networks at six different locations to support aviation safety needs.[44]

· Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS). The system, currently in use, provides pilots of air carriers, large aircraft, and others, with air traffic position information and recommends maneuvers to avoid nearby aircraft, according to FAA guidance.[45] FAA officials said this technology could be used in BVLOS drone operations in the future, but adaption for such usage is in the early stages. FAA has funded the research and development of different ACAS systems for different types of aircraft, including the MITRE Corporation and MIT Lincoln Laboratory’s development of ACAS for small drones (those up to 55 pounds).[46] According to FAA’s May 2023 Request for Comment on BVLOS for drones, one proposal to achieve detection and avoidance between drones would be to use industry developed minimum performance standards for ACAS for small drones and leverage some form of drone-to-drone communications method.[47] FAA sought comment on the communications method that should be used with this type of ACAS, whether specific communication methods should be required, and whether a requirement would sufficiently manage the risk of collision between drones.

Additionally, FAA envisions using vehicle-to-vehicle communication links, generally referred to as aircraft-to-everything, as an input to ACAS. According to a MITRE report funded by FAA, the drone industry deemed aircraft-to-everything as critical in supporting BVLOS operations because it would enable the exchange of surveillance and safety data for the purpose of situational awareness, traffic management, and detection and avoidance. While FAA has worked with organizations and industry to research aircraft-to-everything in supporting drone integration, officials said they do not have a long-term plan for the technology. Rather, they said it is up to the industry to determine its needs for the technology.

Aside from technology development, FAA is collaborating with NASA to establish and implement a framework to research, develop, and test drone-to-drone traffic management concepts and capabilities with industry stakeholders. For example, the two agencies are working with the drone industry in North Texas to collect and evaluate operational data on drone traffic management to inform large-scale drone operations nationwide. In North Texas, we observed companies conducting drone operations, often under BVLOS waivers, and collecting data on these operations. For example, operators are conducting business operations such as package delivery under the operational evaluation framework. According to FAA, activities at this site mark the first near-term implementation of BVLOS operations and leverage traffic management services for strategic coordination. Additionally, DOT officials told us that conformance monitoring—which ensures that all drones operate within their deconflicted zones, maintain communication with others, and consistently remain aware of their location and intended operations—is a key function of drone traffic management and could allow for strategically separated drones in the future.

FAA also noted that the activities in North Texas provide the data required to expand BVLOS implementation and inform its rulemaking efforts. Further, the BVLOS NPRM states FAA has learned through data collection and observation of the UTM Key Site Operational Evaluation that industry can effectively self govern many aspects of standing up and running a UTM system. According to the NPRM, this was a result of industry committing to adhere to an interoperability standard for UTM at the site. Figure 6 depicts a drone preparing for a package delivery in North Texas.

FAA Envisions a Future National Airspace with Location Information Shared by All Users, but Planning Related to the Inclusion of Drones Remains in the Early Stages

FAA officials emphasized the importance of electronic conspicuity of all aircraft in relation to the agency’s vision for the future of the NAS. This vision, part of what FAA refers to as an information-centric NAS, calls for responding to the future needs of airspace users by implementing services beyond air traffic to include drone traffic management and advanced air mobility services.[48] FAA’s vision, discussed below, is for all airspace users to have the ability to share aircraft location information electronically to address the future increase and diversity of air traffic and to ensure safety and efficiency. FAA emphasized that an all-electronically conspicuous NAS would be necessary for the safety of the future information-centric NAS.[49]

As of July 2025, FAA had developed high-level planning documents related to the future information-centric NAS, which forecast initial system and technology capabilities to be operational by approximately 2035. According to these documents, which are summarized below, a broad group of stakeholders will play key roles in developing the future technology—to include technology that will enable all airspace users to share some location position information—consistent with the broad vision FAA has articulated. More specifically:

· Charting Aviation’s Future: Operations in an Info-Centric NAS.[50] This document sets forth FAA’s vision for the information-centric NAS as building upon its Next Generation Air Traffic Modernization (NextGen) program and other related efforts.[51] According to the document, the future NAS must support changes in airspace operations, such as drones delivering small packages on a large scale and highly automated urban air mobility services transporting people and cargo in congested areas. The document also indicates the need for all airspace users to share some position information within the information-centric NAS by working with industry as methods and standards are developed for drone traffic management. It notes that “this vision document is to start the conversation on who will be responsible for what in an info-centric, coordinated aviation future,” and that each role will need to be clearly established to move forward toward integrated operations.

· FAA’s Initial Concept of Operations for the Info-Centric National Airspace System: In this document, FAA states the agency’s expectation for stakeholders to use the document as a framework to develop more specific details regarding services, solutions, and capabilities as well as research and development planning for an information-centric NAS.[52] The agency also envisions that the document will facilitate alignment, consistency, interoperability, and technology integration across the NAS. Reiterating the expectation for all aircraft to share some level of position and operational intent data, the document states that an “integrated information environment” will serve as the information exchange to provide all users with a common situational awareness of nearby operations.

· NAS Enterprise Architecture Roadmaps: These documents are intended to communicate strategic improvements to the NAS over time and the supporting research and capital investment activities that enable them in areas such as infrastructure, services, and data integration.[53] The roadmaps, which were updated in May 2025, include general timelines for some activities. For example, one timeline indicates a time frame for drone detect and avoid that will occur from 2024 through 2030. The roadmap includes brief descriptions of four milestones in 2025 and 2026. Based on available information, these efforts are limited to work underway by FAA, RTCA, and other stakeholders to develop minimum performance standards for detect and avoid equipment and command and control links. The roadmap does not identify milestones beyond 2026 and does not include additional information on how detect and avoid for all drones will be achieved in the agency’s time frame or what any additional efforts would entail.

In discussing how drones could be incorporated into the information-centric NAS, FAA officials said that limitations with current detect and avoid technologies that rely on ADS-B would require the development of some other electronic conspicuity technology for drones to communicate with, and detect and avoid, other aircraft.[54] Because drones can only receive ADS-B data with ADS-B In and are generally prohibited from using ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode, drones cannot directly communicate with other aircraft using this technology. Also, as previously discussed, other existing technologies that can detect manned aircraft have limitations.

Further, DOT officials provided information in December 2025 stating that the ADS-B system was not designed to accommodate the sheer number of drones entering the airspace, leading to potential signal issues. These issues include:

· Signal congestion: FAA has expressed concern that a proliferation of ADS-B Out transmitters on drones could saturate the frequencies, negatively affecting the safety of manned aircraft. This concern is a primary reason for the ADS-B Out prohibition on small UAS.

· Cooperative only: ADS-B is a “cooperative” system, meaning it can only detect other aircraft that are also broadcasting an ADS-B signal. It provides no information on aircraft without this equipment, such as smaller general aviation planes or military aircraft that have their systems turned off for various reasons.

· Data integrity risks: ADS-B relies on GPS data, and as noted previously, these data can be spoofed, jammed, or experience dropouts. Without independent, non-cooperative sensors, drones relying solely on ADS-B for collision avoidance could be vulnerable to false or missing information.

Due to these limitations, DOT officials said that ADS-B alone is not a reliable “detect-and-avoid” solution for safe drone integration.

To address the challenges posed by existing technologies and ensure the inclusion of drones in the information-centric NAS, FAA officials told us that they intend, in the future, to focus on developing performance-based standards and safety requirements that can be used to integrate new technologies. Those technologies, consistent with FAA’s high-level planning documents, would enable all NAS users, including drones, to electronically communicate with, and detect and avoid other, aircraft. These actions would represent a positive step; however FAA has not yet identified (1) specific actions the agency intends to take or (2) technical milestones that would need to be reached in a timely manner to inform and support initial capabilities of the information-centric NAS. During our review, FAA officials said that they have had limited resources available to undertake this effort and have instead focused available resources on the BVLOS rulemaking and approving waivers for BVLOS operations.[55]

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should, among other things, identify and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[56] These standards also state that management should design specific actions to respond to risks. FAA faces risks to achieving its goal of an information-centric NAS that would include increased numbers of drones performing advanced operations without drones having the capability to share their location data and detect other aircraft. Identifying and responding to these risks could also help FAA achieve its safety mission given that the safety of the future information-centric NAS, according to FAA, would require all aircraft to be electronically conspicuous.

Furthermore, Congress has also identified the importance of progressing toward an information-centric NAS and has directed FAA to begin planning for its development. Specifically, the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 required FAA to establish an airspace modernization office that would, among other things, be responsible for developing an information-centric NAS as well as developing and periodically updating an integrated plan for the future state of the NAS by May 2027.[57] In this plan, FAA is required to include a roadmap for creating and implementing the integrated plan that identifies obstacles and the activities to overcome them, federal and nonfederal roles, costs, technical milestones that will be used to evaluate the activities, technology gaps, and a description of the operational concepts to meet the system performance requirements for all system users.

While the statutory language requiring the plan contains some broadly phrased requirements, it could serve as a guide for FAA to address risks and uncertainty regarding how drones will be capable of communicating with, and detecting and avoiding, other aircraft in an information-centric NAS. For example, determining federal and nonfederal roles for collaborating would be particularly useful given that FAA envisions a broad group of stakeholders using its Concept of Operations to achieve new capabilities and services, such as detection and avoidance, that will be part of an information-centric NAS. Ensuring that stakeholders’ roles are clear and that they are brought into the process early would also be important given that some stakeholders have raised privacy concerns related to existing technology that shares their aircraft location data, as mentioned earlier.[58] In addition, addressing costs would be beneficial given that FAA cited limited resources as a reason the agency has not begun developing standards for how drones will communicate with and detect and avoid other aircraft. Further, it would be important for FAA to identify milestones for enabling development of the technology and tracking progress and to determine how FAA and industry will collaborate to resolve any obstacles.

Taking action in the near term would also align with and inform requirements in the President’s June 2025 executive order on drones. This order, among other things, requires that the Secretary of Transportation, acting through the Administrator of the FAA, to publish an updated roadmap for the integration of drones into the NAS by February 2026. Lastly, FAA’s work in this area, with industry, could better position the agency to determine how to eventually achieve electronic conspicuity for all airspace users in the future NAS, which FAA said should be the ultimate goal of these efforts.

Conclusions

FAA is charged with ensuring the safety of the NAS, a responsibility that will likely become more complicated, in part, as advanced drone operations increase. Existing technologies are limited in their ability to enable drones to communicate with and detect and avoid other aircraft. Congress has tasked FAA with the responsibility to develop an information-centric NAS, where FAA envisions all airspace users being connected through an integrated system, with each user having the capability to share location information electronically with one another. Congress also required FAA to develop and periodically update an integrated plan for the future state of the NAS, including a roadmap for creating and implementing the plan, by May 2027. In addition, a June 2025 executive order requires FAA to publish a roadmap for the integration of civilian UAS into the NAS by February 2026. In August 2025, FAA proposed new rules that would require drones flying beyond visual line of sight of the operator to detect and avoid other aircraft. To build upon FAA’s drone integration efforts, developing specific actions to address how drones will communicate with and detect and avoid other aircraft within an information-centric NAS would align with, and could serve to inform, the planning requirements set forth by Congress and the executive order. Specific actions intended, for example, to determine federal and nonfederal roles, resource needs, and milestones could clarify FAA’s plans for this operational aspect of the future NAS and how the agency will ensure safe operations for all airspace users.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to FAA:

The Administrator of FAA should develop and begin implementing specific actions, including but not limited to establishing clear federal and nonfederal roles, estimated costs, and technical milestones, to ensure that drones will be capable of communicating with and detecting and avoiding other aircraft within an information-centric NAS. (Recommendation 1)

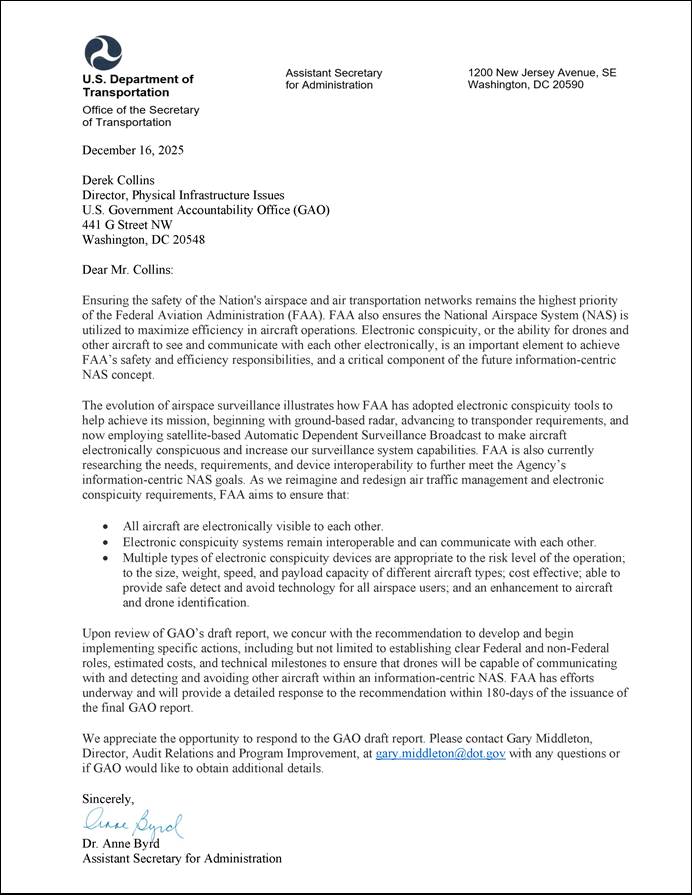

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOT, NASA, and NTSB for review and comment. DOT provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendix III. DOT concurred with our recommendation. DOT also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate. DOT’s technical comments provided additional clarification on ADS-B and ongoing research efforts. DOT also recognized that (1) drones and other aircraft need to be able to see and communicate with each other electronically for FAA to effectively fulfill its safety and efficiency responsibilities and (2) this ability is a critical component of the information-centric NAS.

NASA and NTSB provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate. Among its technical comments, NASA suggested expanding the recommendation to encourage FAA to engage more broadly with other federal agencies on national needs for drone operations in the NAS. NASA also had suggestions for how the federal role should be determined in an information-centric NAS. While NASA’s suggestions and perspective would be useful for FAA to consider going forward, we did not incorporate them in this report, given the scope of our review. NTSB’s technical comments related to data on mid-air collisions.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation; the Administrators of FAA and NASA; the Chairwoman of NTSB; and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at CollinsD@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Derrick Collins

Director, Physical Infrastructure

Airspace Classifications

· Controlled airspace is a term that covers the different classifications of airspace and defined dimensions within which air traffic control service is provided to Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) and Visual Flight Rules (VFR) operators in accordance with the airspace classification.[59]

· Class A. Class A airspace generally covers the airspace from 18,000 feet mean sea level (MSL) up to and including flight level (FL) 600 (a flying altitude of 60,000 feet MSL), including the airspace overlying the waters within 12 nautical miles off the coast of the 48 contiguous states and Alaska; and designated offshore airspace areas beyond 12 nautical miles off the coast of the 48 contiguous states and Alaska in international airspace within which the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) applies domestic air traffic control (ATC) procedures.

· Class B. Class B airspace generally covers airspace from the surface to 10,000 feet MSL surrounding the busiest airports in terms of civil aviation operations conducted under IFR or passenger enplanements.[60]

o The Mode C Veil is airspace within 30 nautical miles of airports listed in Appendix D, Section 1 of 14 CFR part 91 (generally primary airports within Class B airspace areas, such as Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and Los Angeles International Airport), from the surface upward to 10,000 feet MSL.[61]

· Class C. Class C airspace generally covers airspace from the surface to 4,000 feet above the airport elevation (charted in MSL) surrounding those airports that have an operational control tower, are serviced by a radar approach control, and that have a certain number of IFR operations or passenger enplanements.

· Class D. Class D airspace generally covers airspace from the surface to 2,500 feet above the airport elevation (charted in MSL) surrounding those airports that have an operational control tower.

· Class E. Class E airspace generally covers airspace that is designated to serve a variety of terminal or en route purposes, such as the surface area designated for an airport where a control tower is not in operation, an extension area to Class C, Class D, or Class E surface areas to contain instrument approach procedures, or transition areas extending upward from 700 feet above ground level (AGL) or 1,200 feet AGL to the overlying controlled airspace designated for transitioning aircraft to/from the terminal area or en route environments. Class E airspace extends upward from 14,500 feet MSL to, but not including, 18,000 feet MSL overlying the 48 contiguous states, the District of Columbia (D.C.) and Alaska, including the waters within 12 nautical miles from the coast of the 48 contiguous states and Alaska, and the airspace above FL 600. Class G airspace is uncontrolled airspace that has not been designated as Class A, Class B, Class C, Class D, or Class E airspace.[62]

Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B Out) Equipment and Use Requirements

· ADS-B Out equipment is required within:

· Class A, B, and C airspace areas;[63]

· The Mode C Veil from the surface to 10,000 feet MSL;

· Above the ceiling and within the lateral boundaries of a Class B or Class C airspace area designated for an airport upward to 10,000 feet MSL;

· Class E airspace within the 48 contiguous states and D.C. at and above 10,000 feet MSL, excluding the airspace at and below 2,500 feet above the surface; and

· Class E airspace at and above 3,000 feet MSL over the Gulf of Mexico from the coastline of the U.S. out to 12 nautical miles.[64]

· To fly in airspace in which ADS-B Out is required, such equipment must be installed in the aircraft, operated in transmit mode at all times, and meet certain performance requirements as outlined in ADS-B regulations, including certain FAA technical standard orders (TSO) and Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA) minimum operational performance standards.[65]

· However, there are exceptions for certain types of aircraft.

· Aircraft Without Electrical Systems. Any aircraft that was not originally certificated with an engine-driven electrical system, or that has not subsequently been certified with such a system installed, including balloons and gliders, may conduct operations without ADS-B Out in the following airspaces in which ADS-B Out equipment would otherwise be required:

· Class E airspace within the 48 contiguous states and D.C. at and above 10,000 feet MSL; and

· The Mode C Veil if those operations are conducted:

o Outside any Class B or Class C airspace area; and

o Below the altitude of the ceiling of a Class B or Class C airspace area designated for an airport, or 10,000 feet MSL, whichever is lower.[66]

· Security Sensitive Aircraft. Aircraft authorized by FAA that are performing a sensitive government mission for national defense, homeland security, intelligence, or law enforcement purposes are not required to operate ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode when transmitting would compromise the operations security of the mission or pose a safety risk to the aircraft, crew, or people and property in the air or on the ground.[67]

· Safe Execution of ATC Functions. Aircraft directed to not transmit ADS-B Out by ATC when transmitting would jeopardize the safe execution of ATC functions.[68]

· Drones. Unless otherwise authorized by FAA, drones that fly under 14 CFR part 107 may not be operated with ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode.[69] Drones that fly under 14 CFR part 91 may not be operated with ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode unless the operation is conducted under a flight plan and the person operating that drone maintains two-way communication with ATC or the use of ADS-B Out is otherwise authorized by FAA.[70]

|

Category |

Stakeholder |

|

General Aviation |

Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association |

|

|

Vertical Aviation International |

|

|

Experimental Aircraft Association |

|

|

National Agricultural Aviation Association |

|

Drone Operators |

Wing |

|

|

Zipline |

|

|

Skydio |

|

|

Commercial Drone Alliance |

|

|

Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International |

|

|

Academy of Model Aeronautics |

|

Avionics Manufacturers |

UAvionix |

|

|

General Aviation Manufacturers Association |

|

|

FLARM (Flight Alarm) |

|

Research Organizations |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Lab |

|

|

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership |

|

|

Qualcomm |

|

|

MITRE |

|

Standards and Government Organizations |

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) |

|

|

European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

|

|

National Association of State Aviation Officials |

|

|

National Transportation Safety Board |

|

|

Department of Transportation/Federal Aviation Administration |

|

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

|

Irving Police Department, Irving, Texas |

|

|

North Central Texas Council of Governments |

|

|

|

Source: GAO | GAO‑26‑107648

GAO Contact

Derrick Collins, collinsd@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, David Sausville (Assistant Director), Alex Jeszeck (Analyst-in-Charge), Tommy Baril, Dwayne Curry, Geoffrey Hamilton, Richard Hung, Delwen Jones, Aaron Kaminsky, Alicia Loucks, Camilla Ma, Rebecca Morrow, Josh Ormond, and Kelly Rubin made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]BVLOS refers to drone operations where the pilot can no longer visually see the drone.

[2]14 C.F.R. § 91.225. Controlled airspace is a term that covers the different classifications of airspace and defined dimensions within which air traffic control service is provided to Instrument Flight Rules and Visual Flight Rules operators in accordance with the airspace classification. For more information about the different airspace classifications, see appendix I.

[3]ADS-B Out broadcasts information about an aircraft’s GPS location, altitude, velocity, and related data to other aircraft, such as drones, once or more per second. Electronic conspicuity in aviation refers to technology that broadcasts aircraft position information (e.g., location, altitude, and speed) to air traffic controllers and other pilots. Detect and avoid technology is designed to allow drones to prevent collisions with other aircraft in flight. Some detect and avoid technologies rely on other aircraft being electronically conspicuous (e.g., by transmitting a broadcast signal with ADS-B Out) so that the drones can receive an electronic signal, thereby providing them with the capability to detect and avoid these aircraft.

[4]Unless otherwise authorized by FAA, drones that fly under 14 CFR part 107 may not be operated with ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode. 14 C.F.R. § 107.53. Drones that fly under 14 C.F.R. part 91 may not be operated with ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode unless the operation is conducted under a flight plan and the person operating that drone maintains two-way communication with air traffic control (ATC) or the use of ADS-B Out is otherwise authorized by FAA. 14 C.F.R. § 91.225(h)(2). For more information about these requirements, see appendix I.

[5]90 Fed. Reg. 38212 (Aug. 7, 2025).

[6]The provision specifies for us to review technologies and methods. We refer to technologies throughout the report and include the methods by which those technologies are used.

[7]FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-63, § 906, 135 Stat. 1025, 1342.

[8]The GAO review provision in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 includes that GAO consult with representatives of drone manufacturers and operators, general aviation operators, helicopter operators, and agricultural aircraft operators, as well as state and local government officials.

[9]The BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee was made up of representatives from aviation associations, the aviation industry, public interest groups, advocacy groups, and interested members of the public. FAA tasked the committee in June 2021 to provide advice and recommendations concerning a full range of aviation-related issues.

[10]A small unmanned aircraft system (UAS) is defined to consist of a small unmanned aircraft and its associated elements—including the control station and the associated communication links—that are required for safe and efficient operation in the national airspace system. 14 C.F.R. § 107.3. For the purposes of this report, we use the term “drone” to refer to small unmanned aircraft, which are defined as weighing less than 55 pounds on takeoff, including everything that is on board or otherwise attached to the aircraft. 14 C.F.R. § 107.3.

[11]GAO, Drones: FAA Should Improve Its Approach to Integrating Drones into the National Airspace System, GAO‑23‑105189 (Washington, DC: Jan. 26, 2023) and GAO, Unmanned Aircraft Systems: FAA Could Strengthen Its Implementation of a Drone Traffic Management System by Improving Communication and Measuring Performance, GAO‑21‑165 (Washington, DC: Jan. 28, 2021).

[12]When we discuss the statements made by stakeholders in the report, we defined modifiers (e.g., “some”) to quantify stakeholders’ views as follows: “nearly all” stakeholders represents 20 to 24 stakeholders, “most” stakeholders represents 12 to 19 stakeholders, “some” stakeholders represents five to 11 stakeholders, and “a few” stakeholders represents two to four stakeholders.

[13]Federal Aviation Administration, Charting Aviation’s Future: Operations in an Info-Centric National Airspace System, (Washington, D.C.: September 2022); Initial Concept of Operations for an Info-Centric National Airspace System, (Washington, D.C.: December 2022); and NAS Enterprise Architecture Infrastructure Roadmaps v. 19.2 (May 2025).

[14]FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, Pub. L No. 118-63, § 207, 22, 138 Stat. 1025, 1046. The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 requires the integrated plan to include a roadmap for creating and implementing the integrated plan.

[15]The June 2025 executive order provides that it is the policy of the United States to ensure continued American leadership in the development, commercialization, and export of UAS by, among other things, accelerating the safe integration of UAS into the National Airspace System through timely, risk-based rulemaking that enables routine advanced operations. Exec. Order No. 14307, Unleashing American Drone Dominance, 90 Fed. Reg. 24727 (June 6, 2025).

[16]90 Fed. Reg. 38212 (Aug. 7, 2025).

[17]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[18]According to National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) officials we spoke with in October 2024, there had been 37 domestic drone incident investigations since 2006. In September 2025 NTSB officials told us of those, five were determined to have been due to a mid-air collision between a manned aircraft and a drone.

[19]14 C.F.R. § 107.31.

[20]In some instances, FAA has the authority to issue a waiver from certain regulations restricting the operation of drones if it finds that a proposed drone operation can be safely conducted under the terms of that certificate of waiver. See, e.g., 14 C.F.R. §§ 107.200, 107.205. For example, FAA may waive 14 C.F.R. § 107.39, which restricts the operation of drones over human beings in certain circumstances. The June 2025 executive order requires FAA to initiate the deployment of AI tools to assist in and expedite the review of UAS waiver applications under 14 C.F.R. Part 107. Exec. Order No. 14307, 90 Fed. Reg. 24727 (June 6, 2025). This order requires, for example, that such AI tools are to support performance- and risk-based evaluation of proposed operations.

[21]With respect to advanced operations, FAA provides that “[m]any drone operations can be conducted under the Small UAS Rule (14 C.F.R. Part 107), or as a recreational flight with the guidelines of a modeler community-based organization. However, more complex operations may need additional certification or approval.” FAA provided examples of advanced operations to include aircraft certification, operational approvals for emergency situations, dispensing chemicals and agricultural products, and package delivery by drone.

[22]FAA regulations at 14 C.F.R. Part 107 allow for the operation of small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in the National Airspace System and, according to FAA, cover almost all non-recreational UAS operations. According to FAA Advisory Circular 91-57C, what constitutes a recreational operation is a situation-specific determination but may not include activities such as flights for any compensation, monetary or otherwise, and flights related to or in furtherance of a business. Public safety operators may also operate UAS under the general operating and flight rules at 14 C.F.R. Part 91, and recreational users may fly under the requirements of 49 U.S.C. § 44809, which provides an exception for limited recreational operations of UAS.

[24]According to FAA officials, within detect and avoid technology, there are both cooperative and non-cooperative surveillance methods. Cooperative surveillance includes methods of detecting an aircraft that is broadcasting its position via its broadcast signal. Non-cooperative surveillance involves methods of detecting an aircraft that is not broadcasting its position.

[25]Drones are limited in their ability to fly near airports since they cannot operate in most controlled airspace without prior authorization, and operators are expressly prohibited from operating in a manner that interferes with airport operations and traffic patterns. 14 C.F.R. §§ 107.41, 107.43; see also 18 U.S.C. § 39B (making it a criminal offense to knowingly operate an unauthorized unmanned aircraft in specified areas that are in close proximity to airports). According to information provided by FAA, for flights near airports in controlled airspace, drone operators must receive an airspace authorization prior to the operation, which comes with altitude limitations and may include other operational provisions. For flights near airports in uncontrolled airspace that remain under 400 feet above the ground, prior authorization is not required; however, when flying in these areas, drone operators must be aware of and avoid traffic patterns and takeoff and landing areas.

[26]See 14 C.F.R. §§ 107.53, 91.225(h)(2).

[27]Pursuant to 14 C.F.R. § 91.225(f), aircraft authorized by FAA and performing a sensitive government mission for national defense, homeland security, intelligence, or law enforcement purposes are not required to operate ADS-B Out equipment in transmit mode when transmitting would compromise the operation’s mission security or pose a safety risk to the aircraft, crew, or people and property in the air or on the ground. With respect to 14 C.F.R. § 91.225(f), some pending legislation in the 119th Session of Congress would, for example, require that the term “sensitive government mission” be “narrowly construed and shall not include routine flights, non-classified flights, proficiency flights, or flights of Federal officials below the rank of Cabinet Member or the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.” Rotorcraft Operations Transparency and Oversight Reform Act, S 2503, 119th Cong. (2025). See also, e.g., Rotorcraft Operations Transparency and Oversight Reform Act, H.R. 6222, 119th Cong. (2025); Safe Operations of Shared Airspace Act of 2025, S. 1985, 119th Cong. (2025).