DOD SYSTEMS MODERNIZATION

Further Action Needed to Improve Travel and Other Business Systems

Report to Congressional Requesters

Revised on February 9, 2026, to include a digital signature in DOD’s comment letter reproduced on page 73.

January 2026

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Vijay A. D'Souza at dsouzav@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

In May 2023, the Department of Defense (DOD) discontinued

its MyTravel initiative and directed all users to return to the previous

Defense Travel System (DTS). Based on information from DOD, the department’s

abandonment of MyTravel was due to four primary factors: lack of a central

leadership authority and advocate for change; insufficient program management

practices; inadequate outreach to understand evolving stakeholder needs; and

inconsistent inclusion of key users in gathering and tracking program requirements.

While DOD is reinvesting in DTS to add key capabilities, the department has not

yet fully addressed applicable leading practices related to the primary factors

of MyTravel's abandonment (see figure). These practices include statutory

department-specific business system requirements. Overall, DOD fully addressed

12 practices, partially addressed six, and did not address four. Of particular

concern are the three program management and five requirements management

practices that are not yet fully addressed. Until it fully implements these

practices, DOD risks shortcomings in managing the program and in ensuring that

users are involved in requirements gathering and tracking.

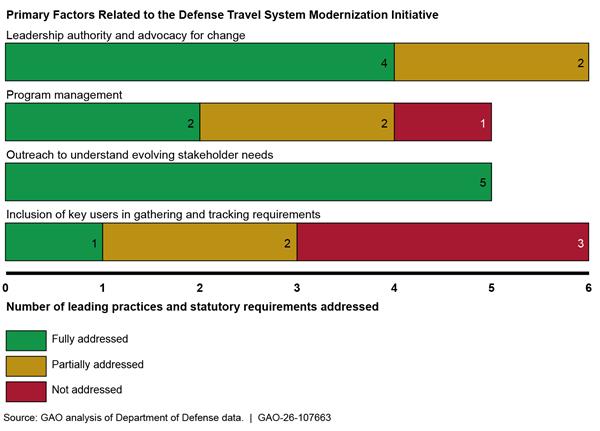

Assessment of DOD’s Defense Travel System Against Selected Leading Practices and Statutory Elements Related to the MyTravel System’s Abandonment

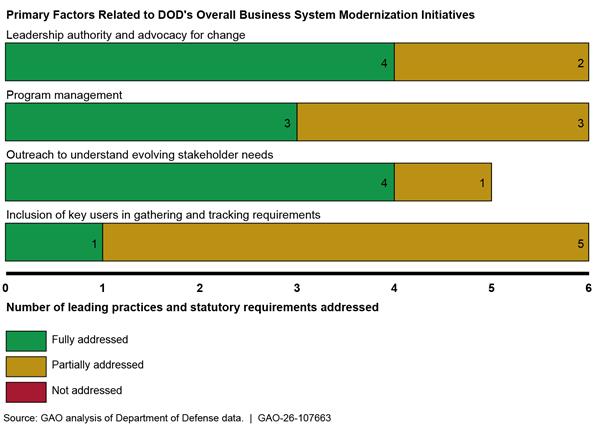

Regarding overall system modernization, DOD has department-wide improvements underway. However, its policies and guidance for managing and directing these efforts do not fully address 11 of 23 leading practices and statutory requirements related to the above four factors. For example, the department has established a framework to monitor progress of selected programs but has not established a permanent leadership structure for the efforts or taken steps to ensure that programs fully align with department-wide goals and priorities. Without fully implementing these leading practices and statutory requirements, DOD can experience coordination issues and inconsistent execution in planning and making improvements to its business systems modernization efforts.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD relies on its travel system to support mission-critical operations. DOD has faced multiple challenges in its many attempts to modernize this system, most recently through the abandoned MyTravel initiative. Similar challenges have kept DOD’s business systems modernization on GAO’s High-Risk List since 1995.

GAO was asked to review the DTS modernization program and DOD’s overall business system modernization. This report examines (1) primary factors that caused DOD’s abandonment of MyTravel, (2) the extent to which DOD is following applicable leading practices in modernizing DTS, and (3) the extent to which DOD is following selected practices in its overall business systems modernization.

To conduct this review, GAO analyzed DOD documentation related to MyTravel and identified leading practices for system modernization. GAO analyzed DOD efforts to modernize its travel system, as well as documentation related to departmentwide business system modernization efforts, against the leading practices. GAO also interviewed relevant DOD officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 13 recommendations to DOD, including to identify leadership roles for the DTS modernization and department-wide Defense Business Council, and to document details for the tracing and prioritization of requirements. The department concurred with 11 recommendations. Although partially concurring with the remaining two, DOD provided information on steps it had underway or planned to implement all 13 recommendations. GAO will continue to monitor the department’s actions to address these recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BEA |

business enterprise architecture |

|

BSM |

Business Systems Modernization |

|

CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

|

DBC |

Defense Business Council |

|

DHRA |

Defense Human Resources Activity |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DTM |

Defense Travel Modernization |

|

DTMO |

Defense Travel Management Office |

|

DTS |

Defense Travel System |

|

IT |

information technology |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2026

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Nancy Mace

Chairwoman

Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and

Government Innovation

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense (DOD) is the largest U.S. government department and one of the most complex organizations in the world. DOD employs 2.1 million military service members and approximately 780,000 civilian employees at approximately 4,600 sites. In fiscal year 2022, DOD employees booked over 3.2 million trips using the department’s internal travel systems. In Fiscal Years 2016 through 2018, DOD spent an average of $6.1 billion annually on payments for travel made through Defense Travel System (DTS), the department’s primary system to process travel payments.

In 2018, DOD announced an effort to replace DTS with a new commercial solution, known as MyTravel. The department mandated the use of MyTravel for selected DOD organizations in October 2022. However, in May 2023, DOD abandoned its effort and instructed components to revert to the Defense Travel System.[1] In July 2023, we testified that DOD has faced issues in managing DTS and that DOD’s decision to abandon the MyTravel modernization raised concerns about its ability to implement reforms effectively.[2]

The challenges DOD experienced on its travel system are consistent with those experienced on other business systems modernization efforts over the last three decades.[3] While DOD’s capacity for modernizing its business systems has improved over time, significant challenges remain. As a result of the challenges it has faced, DOD’s business systems modernization efforts have been on GAO’s High-Risk List since 1995.

Given the importance of this modernization and DOD’s past challenges in this area, you asked us to review the DTS modernization program and DOD’s overall business system modernization efforts. Our specific objectives were to determine (1) the primary factors that caused DOD to abandon its migration to the MyTravel system and related leading practices and statutory requirements; (2) DOD’s plans to modernize its travel system and to what extent it is following selected leading practices and statutory requirements in modernizing this system; and (3) to what extent DOD is following selected leading practices and statutory requirements for overall improvement of its business system modernization efforts.

To address the first objective, we reviewed and summarized documentation supporting DOD’s decisions to abandon MyTravel, such as memoranda, department-wide communications, external congressional and executive reports, documentation of decision reviews, and a lessons learned report. We used this information to identify and describe four primary factors that caused DOD to end implementation of MyTravel, and to revert to DTS. We used a two-analyst process in which a first analyst created a mapping of causal relationships between events to justify the groupings for each primary factor, and a second analyst then independently verified all sources and corroborated the logic used for the groupings. We further validated the primary factor results through interviews and discussion with relevant officials within DOD, including in the Defense Manpower Data Center, Defense Services Support Center, Defense Travel Management Office, and the Office of the Chief Information Officer.

Next, we identified leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to the four primary factors through review of past GAO work and DOD policies, in consultation with internal stakeholders. We then chose criteria from each of these sources and grouped them based on applicability to the four primary factors listed above. We used criteria from five main sources, including requirements in the Fiscal Year 2005 National Defense Authorization Act, which was later amended, as codified in 10 U.S.C. § 2222;[4] past GAO work in the areas of stakeholder involvement, interagency collaboration, and systems modernization; and the Capability Maturity Model.[5] We then chose 23 practices and requirements from each of these sources and grouped them based on applicability to the four primary factors listed above. We validated our selection and organization of these leading practices with applicable internal stakeholders.

For the second objective, we reviewed DOD documentation to determine the status of DOD’s plans to modernize its travel system, including current system state documentation, an acquisition strategy, and a DOD presentation on planned future work for the travel system. To determine the extent to which DOD is following leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to modernizing the DTS system, we identified actions DOD has taken or is planning to take to modernize DTS by reviewing documentation such as a business case analysis, project schedule, and maintenance release plan. We compared these actions to modernize DTS against 22 of the 23 leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to factors underlying the abandonment of the MyTravel system discussed above.[6]

To address the third objective, we compiled a list of policy and procedure related actions DOD has taken or is planning to take to improve its department-wide business system modernization initiatives by reviewing current DOD directives, guidance, strategies, framework, and playbooks. We then compared these policy and procedure actions against all 23 selected leading practices and statutory requirements to determine the extent to which improvements DOD is making to its business system modernization efforts are following them. We selected leading practices and statutory requirements based on their applicability to the MyTravel system’s abandonment, due to historical similarities between these practices and requirements and issues encountered on other DOD business systems modernization (BSM) efforts. In our prior work, each of the four primary factors have been relevant to analyses of department-wide weakness in other DOD business systems modernization efforts. DOD has experienced issues in several recent attempted modernizations of its business systems.[7]

In addition to comparing DOD’s department-wide actions to these 23 leading practices and statutory requirements, we also evaluated improvements to DOD’s BSM efforts against leading practices for agency reform identified in our prior work.[8] We have previously used these reform practices to evaluate DOD’s efforts to modernize its travel system as well as other department-wide reform efforts at DOD.[9]

As part of our second and third objectives, we determined, based on the documents and data provided, the extent to which DOD had fully addressed, partially addressed, or not addressed the leading practices and statutory requirements.

· We considered a leading practice or statutory requirement to be fully addressed when evidence provided by DOD addressed all tasks or activities associated with a specific leading practice or statutory requirement.

· We considered a leading practice or statutory requirement to be partially addressed when evidence provided by DOD addressed some, but not all, tasks or activities associated with a specific leading practice or statutory requirement.

· We considered a leading practice or statutory requirement to be not addressed when evidence provided by DOD did not address any tasks or activities associated with a specific leading practice or statutory requirement.

For all three objectives, we interviewed officials in DOD’s Office of the Secretary of Defense and Office of the Chief Information Officer. For example, we interviewed officials to gain further context on travel system status and history, and specifics on DOD actions to improve its efforts to modernize its business systems. For additional detail on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see Appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

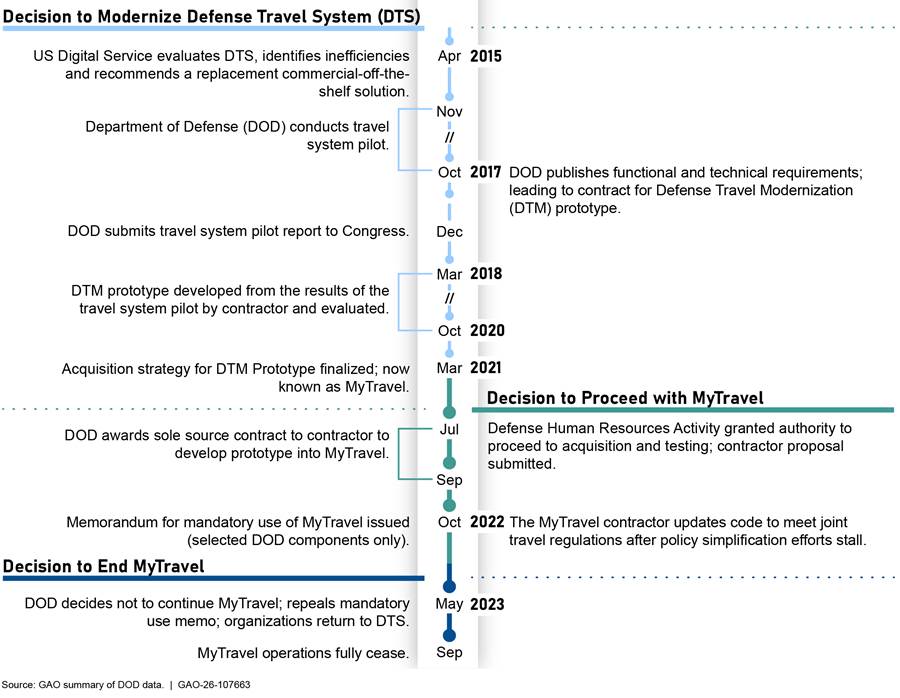

DOD implemented the Defense Travel System (DTS) in the mid-1990s in response to recommendations to provide improved travel capabilities for all DOD employees. Over the next several decades, DTS experienced functional flaws such as improperly displaying flight information, allowing unauthorized premium-class travel, and the processing of improper travel payments.[10] Based on these issues, DOD took steps to modernize its travel system.

Decision to Modernize DOD Travel System

In 2015, DOD began to consider replacing DTS through use of commercial off-the-shelf software. Specifically, in April of that year, the organization then known as the United States Digital Service evaluated the DOD travel process and recommended that DOD pursue a commercial-off-the-shelf solution to improve DTS.[11] According to the Digital Service, use of a commercial-off-the-shelf solution provided advantages such as use of streamlined industry practices and scalability for both system complexity and number of users.[12]

Based on the results of the Digital Service study, the Defense Manpower Data Center conducted a pilot from November 2015 through October 2017 to evaluate the effectiveness of a commercial-off-the-shelf product for defense travel.[13] The Office of the Secretary of Defense submitted a report on the pilot’s progress to Congress in December 2017. The report concluded that the pilot had produced enough information to proceed further with the travel system modernization. It also noted that the pilot suffered from changes to the scope of the project and delays in its execution. According to the report, these changes were due in part to the turnover of DOD executive leadership responsible for the pilot’s oversight.

Following the completion of the pilot, in 2018, DOD awarded a contract to develop a Defense Travel Modernization (DTM) prototype. According to DOD documentation, the purpose of this prototype was to further explore the technical capabilities of the commercial travel services product developed in the pilot.[14] DOD intended the prototype program to identify the requirements needed to provide an effective and efficient travel and travel expensing service. The prototype used a simplified version of the rule set governing DOD business travel.

Decision to Proceed with MyTravel

In October 2020, the Defense Human Resources Activity (DHRA) was granted authority to proceed with acquisition and testing of the DTM prototype. DHRA awarded a contract to continue implementation of the DTM prototype, now referred to as MyTravel.[15] DHRA determined that a competitive process was not necessary for this contract, based on its designation as a highly specialized service, where competition would lead to unnecessary costs or delays on the part of the government.

DOD published an acquisition strategy in March 2021 based on the feasibility findings of the initial pilot and the prototype.[16] This strategy outlined an acquisition approach, program schedule, risk management, and other aspects of the acquisition of MyTravel.

In October 2022, the Under Secretary of Defense issued a mandatory use memorandum, which directed travelers in organizations where MyTravel had previously been implemented to use it for all travel functions it currently supported. This memorandum also directed all organizations that had not yet integrated their Enterprise Resource Planning systems with MyTravel to do so.[17] The mandatory use memorandum did not apply to DOD’s military departments, which were the primary users of defense travel, due to their financial management systems not yet being integrated with MyTravel.[18]

Decision to End MyTravel

DOD continued the implementation of MyTravel through the first half of 2023. However, in May 2023, the Under Secretary of Defense Personnel and Readiness chose not to exercise the next contract option for the MyTravel product, which ended the MyTravel implementation. This decision, documented in a May 2023 memorandum issued by the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, repealed the mandatory use memorandum and DOD organizations using MyTravel at the time were directed to revert to DTS. The memorandum also recommended that DOD organizations stop any planned financial systems integrations with MyTravel. Figure 1 highlights key decisions made on the travel system, and related issues.

Over time, several different DOD entities had key roles in the implementation and oversight of DTS and MyTravel. See Table 1 for a list of these entities and their travel system-related responsibilities.

|

Entity |

Responsibilities |

|

Cross-Functional Team for Travel |

Reviews existing policy, service delivery approaches, and technology within DOD with respect to travel. Published functional, lifecycle, and technical requirements that informed the development of the prototype system which later became MyTravel. Please see Figure 1 for more details. |

|

Defense Human Resources Activity (DHRA) |

Established the Defense Travel Modernization Working Group to bring together key stakeholders across the Department’s travel enterprise. It formally established both the Defense Travel Advisory Panel and the Defense Travel Governance Board and managed the acquisition, testing, and deployment phase for the prototype system which later became MyTravel. |

|

Defense Manpower Data Center |

Collects and maintains an archive of databases on DOD manpower, personnel, and training. Among other things, the center conducted a travel pilot program to evaluate the effectiveness of a replacement for the Defense Travel System (DTS) system. |

|

Defense Travel Advisory Panel |

Integrates policy, financial, travel programs, and systems personnel to advise and approve changes to the Defense Commercial Travel Enterprise. Co-chaired by the Defense Travel Management Office and Defense Manpower Data Center, the Defense Travel Advisory Panel’s role is to ensure that proposed changes to the travel system are reviewed across DOD. |

|

Defense Travel Governance Board |

Established to provide a formal governance structure for DOD’s travel system and oversight for the DTS modernization effort. Chaired by DHRA’s Director of the Defense Support Services Center. |

|

Defense Travel Management Office (DTMO) |

Serves as the central authority for commercial travel within the DOD, responsible for enterprise programs, automated travel systems, and commercial travel policy. DTMO provided policy guidance for development of the pilot system that would eventually become MyTravel, and co-chairs the Defense Travel Advisory Panel, which advises DOD on changes to its travel enterprise. |

|

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness |

Develops policies, plans, and programs to support DOD services and agencies during both wartime and peacetime operations. Among other things, this office notified congressional defense committees of the department’s intent to conduct a travel pilot program and later submitted a report on its results to Congress. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑26‑107663

As discussed in more detail later in this report, DOD is planning further work to improve DTS. In particular, DOD plans to invest additional resources in a multi-year modernization of DTS. According to an official in DOD’s Defense Human Resources Activity, this modernization will improve system functionality and close longstanding capability gaps.

Modernization of DOD Business Systems Is a High-Risk Area

DOD business systems include financial systems as well as systems that support other business functions, such as logistics and health care. DOD spends billions of dollars each year to acquire modernized systems, including ones that address key areas such as personnel, financial management, health care, and logistics. For example, for fiscal year 2025, the department requested approximately $64.1 billion for its total IT and cyber activities, including $47.8 billion for its unclassified IT investments. This request also included investments in major IT and other business programs which are intended to help the department sustain its key business operations.[19]

DOD has taken steps to improve its business system investment management process by addressing some associated recommendations. For example, it has established more stable management roles and responsibilities and developed a roadmap with specific actions and associated milestones to help the department to improve management of its portfolio of defense business systems.[20] While DOD’s capacity for modernizing its business systems has improved over time, significant challenges remain.

Since 1995, the modernization of DOD business systems has remained on GAO’s High-Risk List.[21] GAO’s latest High-Risk report, issued in February 2025, highlighted three steps DOD should take to address challenges it faces in improving management of its business systems acquisitions. Specifically, DOD should:

· improve business systems acquisition management to achieve better cost, schedule, and performance outcomes;

· manage DOD’s portfolio of business system investments more effectively and efficiently; and

· leverage DOD’s federated business enterprise architecture to help it identify and address potential duplication and overlap.[22]

Prior Work Highlights Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements Relevant to Improving Business System Modernizations

GAO has developed leading practices relevant to the modernization of business systems such as MyTravel. Appendix II contains a full list of these leading practice criteria and their sources. These leading practices include:

· Enhancing interagency collaboration.[23] These practices define optimal approaches for collaboration among entities by (1) defining common outcomes; (2) ensuring accountability; (3) bridging organizational cultures; (4) identifying and sustaining leadership; (5) clarifying roles and responsibilities; (6) including relevant participants; (7) leveraging resources and information; and (8) developing and updating written guidance and agreements.

· Implementing agency reform.[24] These practices provide a framework agencies can use to assess the development and implementation of agency reforms to improve their operational efficiency, and include the following four categories: (1) goals and outcomes for the reforms; (2) applying a process for developing the reforms; (3) effectively implementing the reforms; and (4) strategically managing and aligning the federal workforce for the reforms.

· Using Agile development practices to involve stakeholders in key decisions.[25] These practices help entities assess an organization’s readiness to adopt Agile and evaluate its current use of Agile methods, and include: (1) ensuring repeatable processes are in place, (2) fostering an organizational culture that supports Agile methods (3) eliciting and prioritizing requirements effectively, (4) balancing customer and user needs with project constraints, (5) ensuring metrics align with organization-wide goals and objectives, (6) establishing management commitment, and (7) committing to data-driven decision-making.

· Modernizing legacy systems.[26] These practices focus on evaluating whether agencies have adequately planned how they will update or replace aging systems, including: (1) establishing clear milestones to track progress toward modernization goals, (2) providing a detailed description of the work required to modernize the system, and (3) documenting what will happen to the legacy system once the modernization is complete.

· Managing and tracing requirements.[27] These practices help ensure effective requirements management in the context of system modernizations, including (1) validating requirements to confirm they accurately reflect user and mission needs, and (2) managing requirements with bidirectional traceability to maintain consistency and accountability throughout the lifecycle.

In addition to these leading practices, statute requires DOD to enact practices to better ensure success in the development of individual defense business systems. Specifically, the Ronald W. Reagan National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2005 enacted requirements for initial approval and annual certification of business systems, which were later amended, as codified in 10 U.S.C. § 2222.[28] In particular, DOD is required to annually review and certify compliance for covered defense business systems with the following statutory requirements:[29]

1. compliance with the agency’s enterprise architecture;

2. engineering each system to be as streamlined and efficient as practicable, such that the implementation of the system will maximize the elimination of unique software requirements and unique interfaces;

3. assurance of valid requirements; and

4. development of acquisition strategies should be designed to eliminate or reduce the need to tailor commercial-off-the-shelf systems to meet unique requirements or incorporate unique interfaces to the maximum amount practicable.

GAO Has Recommended Actions to Improve DOD Business Systems, Including Its Travel System

Prior GAO reports have outlined actions DOD could take to improve modernization of its business systems. For example:

· In March 2023, we reported that DOD had not updated certification guidance for business systems to comply with statutory requirements. These requirements include establishing oversight processes, using and communicating quality information, sustaining leadership commitment, and managing risk.[30] We made nine recommendations that DOD update this certification guidance to address statutory requirements for, among other things, alignment with DOD’s business enterprise architecture, the promotion and use of valid, achievable requirements, and reduction of the need to tailor commercial-off-the-shelf solutions. As of August 2025, DOD had not demonstrated that its updated certification guidance fully addressed these statutory requirements. DOD had partially addressed six of our recommendations but had not addressed three others.

· In June 2025, we reported that 14 of 24 DOD IT business programs reported cost and/or schedule changes since January 2023 and programs reported mixed progress in meeting performance targets.[31] We made one recommendation to DOD; it has not yet been implemented. Specifically, we recommended that the agency ensures that IT business programs identify and report results data on performance metrics in each of several categories, such as customer satisfaction, strategic and business results, financial performance, and innovation.

GAO has also made recommendations to DOD to improve its travel system. For example:

· In January 2006, we reported that the DTS system was experiencing functional flaws such as improperly displaying flight information and allowing unauthorized premium-class travel.[32] We made 10 recommendations to DOD, including that DOD take steps to streamline its travel management practices. DOD implemented eight of our recommendations, but did not take steps to monitor the number and cost of processing travel vouchers outside of DTS or to simplify the display of airfares in DTS. DOD officials told us that they had not developed the means, nor did they plan to develop the means, to ascertain the number of vouchers that are processed outside of DTS. They also told us that the department did not plan to make any additional changes to the manner in which flights were displayed to the traveler.

· In August 2019, we reported that DOD could do more to reduce improper payments in its defense travel program.[33] We issued five recommendations, including that DOD consider data on improper payment rates in its remediation approach, define terminology, and consider cost effectiveness in deciding how to address improper payments. DOD has implemented all five recommendations.

Further, in July 2023, we testified that DOD’s decision to abandon the MyTravel modernization raised concerns about its ability to implement reforms effectively. To address these persistent travel system challenges, we reiterated the importance of past GAO recommendations that could assist DOD in transforming its business operations and assess reform efforts. Among other things, these recommendations include improving policy compliance monitoring, providing stronger oversight of acquisition programs, modernizing DOD’s business enterprise architecture, and adopting sustainable reform strategies. We also listed several leading practices for reform that DOD could use to improve its business systems modernization outcomes.

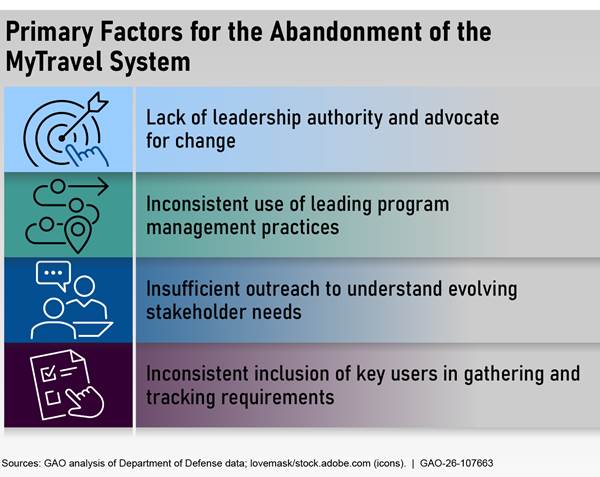

Key Factors Led to Abandonment of the MyTravel System; Leading Practices and Requirements Could Have Helped Mitigate Them

Four primary factors led DOD in May 2023 to abandon development of the MyTravel system and direct its components to revert to using DTS: (1) lack of leadership authority and advocate for change; (2) inconsistent use of leading program management practices; (3) insufficient outreach to understand evolving stakeholder needs; and (4) inconsistent inclusion of key users in gathering and tracking requirements. Implementation of selected leading practices identified in our prior work and by others, as well as specific DOD statutory requirements, could have helped mitigate these factors.

Four Primary Factors Led to the MyTravel System Abandonment

Our assessment of DOD documentation, including an assessment of lessons learned and congressional hearing transcripts, identified four primary factors that led to the abandonment of MyTravel. These factors are listed in figure 2.

DOD Lacked Sufficient Leadership Authority to Prioritize Aspects of Its Modernization

The transition to MyTravel lacked sufficient leadership authority to coordinate implementation efforts, prioritize the most central risks to the system, and more quickly identify potential issues that would prevent the MyTravel modernization effort from achieving its desired outcomes. According to DOD lessons learned documentation, the MyTravel implementation did not have a central decision-making body that could have assisted DOD in recognizing the need for and coordinating of a mitigation plan when faced with an unexpected lack of resources.[34] This body could also have taken steps such as encouraging the utilization of MyTravel over DTS when both systems were live and limiting changes made to DTS while MyTravel implementation was ongoing to promote use of the latter.[35]

According to DOD’s lessons learned document, the transition to MyTravel also did not have an official or organization with sufficient authority to advocate for changes to outdated travel regulations, such as in determining incidental allowances for traveler lodging. DOD’s MyTravel lessons learned document also stated that the timeline establishing planned use by DOD services of MyTravel was further extended due to the department not updating travel regulations.

DOD Did Not Fully Incorporate Program Management Practices in Managing its Modernization

According to DOD’s lessons learned document, the implementation of MyTravel lacked definite project planning milestones for when the DTS system would be sunset. This uncertainty, combined with unexpectedly long lead times DOD took in adding new features requested by users, made it difficult for users to justify switching over from DTS until the later stages of MyTravel, causing lower utilization. The modernization effort also lacked flexibility to adjust to changes or issues in development as they arose, stemming from its decision to use a firm-fixed price contract for MyTravel and to develop it as a commercial off-the-shelf product that was not easily customizable.[36]

Regarding change management, according to DOD’s lessons learned document, DOD did not take steps to manage impacts to users when making changes to functional elements of MyTravel. Specifically, the technical elements of MyTravel were not coordinated over time with functional features, and there was no path for risk escalation when the two diverged. For example, legacy features previously present in DTS were dropped in MyTravel, and DOD did not track the impact of not having these features on the number of MyTravel end users.

DOD Did Not Consistently Perform Outreach to Understand Evolving Stakeholder Needs

During the MyTravel implementation, DOD did not perform sufficient outreach to understand the functions most important to stakeholders. For example, DOD struggled to account for a change in prioritization by the military services stakeholders. Specifically, DOD organizations using MyTravel had to make manual adjustments to financial transactions as their enterprise planning systems could not automate those adjustments.[37] The use of these manual adjustments impacted services’ ability to achieve an unmodified audit opinion.[38] Additionally, outreach to end users to promote and market the use of MyTravel was insufficient due to individual components being responsible for MyTravel’s promotion, rather than a central, DOD-wide campaign.[39]

Further, DOD did not adequately consider impacts to stakeholders when revising elements of MyTravel. According to officials, DOD did not recognize the importance of buy-in from the services on the overall success of MyTravel. There also was no clear understanding of how to support the complex integration of MyTravel into the DOD services’ financial management systems or provide time to accommodate the temporary loss of key features such as support for long-term temporary duty travel.

DOD Did Not Fully Include Key Users in Requirements Gathering and Tracking

After stakeholder needs were established, insufficient contact with military services during the system requirements setting process played a role in DOD’s decision to abandon its migration to the MyTravel system. According to DOD’s MyTravel lessons learned document, the department did not fully include services in requirements gathering until after MyTravel went into production. For instance, DOD did not get input from Army officials on key feature and interface requirements for MyTravel until after the system was operational. According to DHRA officials, a key reason for this was that implementation of MyTravel lacked a milestone to ensure that services’ needs were captured in requirements as part of a minimum viable capability release. As a result, there were persistent capability gaps between DTS and MyTravel that reduced the motivation for services to switch to the new system.

Leading Practices Relate to Primary Factors for MyTravel Abandonment

Selected leading practices and statutory requirements, if implemented, could have helped to mitigate the primary factors leading to MyTravel’s abandonment. Table 2 lists 23 selected leading practices identified in our prior work and by others, as well as statutory requirements, that are relevant to elements of each of the four primary factors. These leading practices are also listed according to their source in Appendix II.

Table 2: Selected Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements Relevant to the Factors That Led DOD to Abandon MyTravel

|

Primary factor for abandonment of the MyTravel system |

Leading practice |

|

Lack of sufficient leadership authority and advocate for change |

Establish management commitment. |

|

Commit to data-driven decision making. |

|

|

Organization culture supports Agile methods. |

|

|

Identify and sustain leadership. |

|

|

Define common outcomes. |

|

|

Ensure accountability. |

|

|

Inconsistent use of leading program management practices |

Comply with the agency’s enterprise architecture. |

|

Describe the work necessary to modernize the system. |

|

|

Include milestones for completing the modernization in system modernization plans. |

|

|

Ensure metrics align with organization-wide goals and objectives. |

|

|

Ensure repeatable processes are in place. |

|

|

Include details regarding the disposition of existing legacy system. |

|

|

Insufficient outreach to understand evolving stakeholder needs |

Clarify roles and responsibilities. |

|

Bridge organizational cultures. |

|

|

Include relevant participants. |

|

|

Leverage resources and information. |

|

|

Develop and update written guidance and agreements. |

|

|

Inconsistent inclusion of key users in gathering and tracking requirements |

Have an acquisition strategy designed to eliminate or reduce the need to tailor commercial-off-the-shelf systems to meet unique requirements or interfaces. |

|

Elicit and prioritize requirements. |

|

|

Streamline and minimize unique requirements and interfaces. |

|

|

Balance customer and user needs when coordinating implementation of requirements. |

|

|

Validate requirements. |

|

|

Manage requirements and ensure bidirectional traceability. |

Sources: GAO analysis of leading practices and statutory requirements against Department of Defense (DOD) information. | GAO‑26‑107663

Note: Information is from Defense Business Systems (10 U.S.C. § 2222(g)); ISACA, Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI), Version 3.0 (Schaumburg, IL: April 2023); and GAO, Agile Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Adoption and Implementation, GAO‑24‑105506 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 15, 2023); Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023); and Information Technology: Agencies Need to Develop Modernization Plans for Critical Legacy Systems, GAO‑19‑471 (Washington, D.C.: June 11, 2019). CMMI Model Copyright © 2023 ISACA. All rights reserved.

Note: For more information on the sources of leading practices and statutory requirements, see Appendix II.

Examples of cases where implementation of specific leading practices or statutory requirements could have been beneficial during MyTravel’s implementation include:

· Regarding leadership authority, as stated above, DOD could have demonstrated stronger management commitment by encouraging use of MyTravel over DTS when the former had completed development. Further, travel system leadership could have defined common outcomes by advocating for changes that it judged as necessary to travel regulations. According to DOD’s MyTravel lessons learned document, the removal of these changes resulted in delays to the timeline for implementing MyTravel.

· Regarding program management, DOD could have followed leading practices in this area by specifying more definite milestones for sunsetting the DTS legacy system. Further, DOD could have better ensured repeatable processes were in place by taking steps to regularly compare that planned technical elements of MyTravel were coordinated with functional requirements needed by end users.

· Regarding outreach to understand evolving stakeholder needs, DOD could have given responsibility for the promotion and marketing of the MyTravel system to one department-wide official. Further, by developing and updating written guidance and agreements, DOD could have formalized and specified commitments by military services to using MyTravel.

· Regarding requirements management, DOD could have more quickly resolved capability gaps between DTS and MyTravel to increase the motivation for military services to switch to the new system. Further, by adding a milestone review to ensure that services’ needs were captured in requirements, DOD could have received formal input from services earlier in the MyTravel development process, allowing for additional time to incorporate that input.

DOD Has Developed Plans to Modernize DTS but Has Not Fully Incorporated Selected Leading Practices

Since abandoning MyTravel in 2023, DOD has taken steps to modernize the Defense Travel System, the travel system in use prior to and during the attempted MyTravel transition. In particular, DOD plans to use ongoing updates and invest additional resources to begin a six-year modernization of DTS. According to DHRA officials, this reinvestment will build on continuous updates made to DTS, while also addressing key capability gaps.

Although it is progressing with plans to improve DTS, DOD is not fully following leading practices and statutory requirements. For example, DOD has not fully documented key modernization milestones, aligned performance metrics with organizational goals, or demonstrated compliance with its enterprise architecture by ensuring new system components integrate with existing DOD IT infrastructure.

DOD Plans to Modernize DTS to Address Key Capability Gaps

Following its decision to end MyTravel operations, DOD convened a working group in November 2023 to determine the best path forward for its defense travel modernization initiative.[40] The working group considered several options, prioritizing factors such as cost efficiency, familiarity among staff with the platforms planned for use, system usability, and integration with the system’s existing payment infrastructure. The working group determined that a phased reinvestment strategy for DTS would best satisfy requirements and provide the needed operational benefits.[41] Based on the working group’s analysis, DOD chose the option to reinvest more resources in DTS, rather than to build a new system.

To further support this decision, the DHRA office performed a business case analysis that identified the specific capability need and an analysis of solutions that would meet that need in line with DOD requirements. The business case analysis, finalized in November 2024, evaluated viable travel system options and confirmed that continued reinvestment in DTS was the best option. This recommendation reinforced the initial findings of the working group from November 2023.

As part of this effort, DOD plans to build on ongoing DTS sustainment activities while also addressing key capability gaps in financial, technical, and functional areas. According to officials from the Defense Support Services Center, though DTS currently remains in a sustainment phase, DOD is planning for broader reinvestment in it.[42] DOD has used Agile development principles to make enhancements to DTS prior to the use of MyTravel, and, according to DHRA officials, intends to continue these Agile processes in the future.

Officials also stated that the department’s goal in aligning current sustainment activities with planned modernization efforts is to allow DOD to improve system functionality and close longstanding capability gaps. DOD aims to do so without launching an entirely new, separate modernization program or delaying crucial improvements by waiting for new programs to advance through their various development phases. According to officials from the Defense Support Services Center, enhancing DTS would allow it to fold enhancement costs directly into existing budgets, providing a better focus on critical needs like improved usability, payment integration, enhanced reporting, and mobile capabilities.

As part of its reinvestment strategy for DTS, DOD is building on policy updates it made previously to align with changing travel regulations, financial management systems, and cybersecurity standards. For example, DOD implemented updates to accommodate changes to department-wide joint travel regulations, new federal financial reporting rules, and integration with evolving industry practices, such as ensuring access to a broader range of commercial airline bookings through the system.[43]

DOD also introduced automated tools within DTS to reduce improper payments and improve compliance with legislative requirements, such as those in the Payment Integrity Information Act.[44] A representative from the Defense Support Services Center noted that the adjustments to DTS were made to ensure compliance with laws and regulations.

DOD has outlined a six-year plan for making its improvements to DTS, which is scheduled to begin in Fiscal Year 2027. DOD’s reinvestment plan prioritizes addressing gaps identified by a department-wide working group. It includes enhancements such as streamlined travel approval processes, cloud infrastructure assessments, improved data reporting, and features like automated trip planning assistance and the ability to remove inactive users from workflows.

Ongoing Efforts to Modernize DOD’s Travel System Do Not Fully Follow Selected Leading Practices

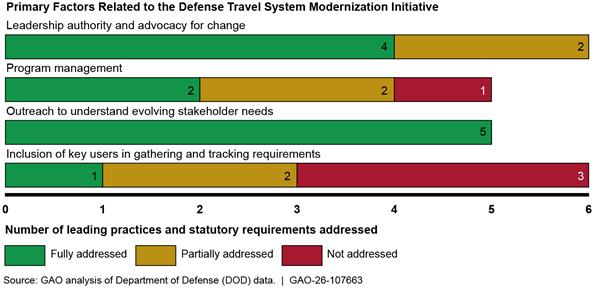

DOD has taken steps to address leading practices and statutory requirements to modernize its travel system, but efforts to address remaining practices and requirements remain incomplete. Specifically, of 22 leading practices or statutory requirements relevant to the primary factors for abandonment of the MyTravel system, DOD fully addressed 12, partially addressed six and has not addressed four. Figure 3 shows the extent to which DOD has incorporated 22 applicable leading practices and statutory requirements in its modernization of DTS.[45]

Figure 3: Assessment of the Extent to Which Modernization of the Defense Travel System Incorporated Selected Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements

DOD Lacks Sufficient Leadership Authority to Prioritize Aspects of the DTS Modernization

Establishing sufficient and effective leadership authority includes six leading practices: (1) establishing management commitment, (2) supporting the development and use of data-driven decision-making, (3) fostering an organizational culture that promotes modern practices, specifically Agile development, (4) defining short- and long-term common outcomes to address challenges, (5) ensuring accountability through clear performance measures, and (6) identification and sustainment of leadership.[46] DOD has fully addressed four and partially addressed two of these practices. Table 3 provides details on how DOD has addressed the six practices with respect to the DTS modernization.

Table 3: Assessment of Defense Travel System (DTS) Modernization Practices Relevant to Leadership Authority

|

Leading practice |

Assessment |

Description of assessment |

|

Establish management commitment. |

● |

The Department of Defense (DOD) established management commitment to the Defense Travel System (DTS) modernization by committing to a multi-year plan for making improvements to DTS that builds on previous travel system policy updates to align with changing travel regulations, financial management systems, and cybersecurity standards. DOD delegated overall responsibility for the DTS implementation to the Defense Travel Modernization Office (DTMO). To facilitate travel system improvements, DOD implemented updates to accommodate changes to department-wide joint travel regulations, new federal financial reporting rules, and integration with evolving industry practices. DOD also allocated resources to the performance of a business case analysis that identified specific travel system capability needs and analyzed a range of potential solutions to meet those needs. |

|

Commit to data-driven decision making. |

● |

DOD has committed to data-driven decision making on the DTS modernization. For instance, the contract governing system sustainment calls for the tracking of metrics in areas such as availability, disaster recovery, and software quality. DOD also produces year-long trend analyses for these metrics. DOD also has produced a document outlining, at a high-level, goals for the modernization of DTS, including documentation of the content of five planned software updates, timing for when each update will occur, and which part of the system each update affects. |

|

Organization culture supports Agile methods. |

◐ |

DOD has emphasized usage of Agile practices for its systems modernizations, including for business systems modernizations such as DTS. DOD has integrated Agile practices into both its training and acquisition strategies. DOD policy and guidance promotes the use of Agile practices as part of the development of DTS, and DOD has committed to using certain Agile practices as part of the DTS modernization. However, the DTS program office is not required to document their commitment to using Agile practices. |

|

Identify and sustain leadership. |

◐ |

DOD has identified key leadership entities and assigned them roles in overseeing functional, technical, and financial aspects of DTS modernization. However, the formal documentation designating the DTMO as the leadership authority for the modernization effort has not yet been finalized. |

|

Defining common outcomes. |

● |

DOD has defined common modernization outcomes through formal governance structures. Specifically, in implementing a business case analysis for DTS, DOD has identified crosscutting challenges and opportunities across functional, technical, and financial domains, and outlined short-term outcomes like system releases and incremental efficiency improvements, alongside its long-term DTS modernization goals. |

|

Ensuring accountability. |

● |

DOD has demonstrated the development of mechanisms to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward short- and long-term modernization outcomes. Among other things, DOD has established processes for management to monitor progress through regular performance reports, which include information on release quality and deployment schedules. It has also developed a business case analysis methodology to track long-term progress and to monitor the resolution of functional, technical, and financial gaps, system efficiency, and potential cost savings. Officials in the DTMO participate in weekly meetings to identify and monitor any delays or issues. |

Legend:

● = DOD fully addressed the leading practice.

◐ = DOD partially addressed the leading practice.

○ = DOD did not address the leading practice.

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107663

As mentioned above, DOD has fully addressed four and partially addressed two of the six leading practices in this area. Specifically:

· DOD has taken steps to promote an organizational culture that supports Agile development for its business systems modernization efforts, for example by integrating Agile practices into both its training and acquisition strategies. In addition, DOD policy and guidance promotes the use of Agile practices for DTS and other business systems.

However, DOD policy does not require owners of business systems such as DTS to document their commitment to using Agile practices. According to DOD policy governing use of Agile software practices, such a documented commitment is unnecessary for DTS because it delivers anticipated value, meets requirements, and successfully iterates based on customer feedback.[47] The policy also states that DTS would require written documentation of its use of Agile practices were it to no longer meet these criteria. However, DOD did not provide documentary evidence to support the ways in which DTS met these requirements. Without documenting the extent of its commitment to Agile practices, DOD risks that it will not be using modern practices in the DTS modernization effort.

· DOD has taken steps to identify entities with leadership responsibilities for the DTS modernization, such as the Defense Travel Management Office (DTMO), Defense Human Resources Activity (DHRA), and Defense Manpower Data Center. DOD has identified DTMO as the overall leader of the modernization.

However, DOD has not documented leadership authority roles for the DTS modernization. According to an official in DOD’s Defense Human Resources Activity, delays in filling the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness position have prevented the department from assigning permanent leadership authority for the DTS modernization. Without doing so, DOD’s ability to establish effective leadership authority over the DTS modernization will be limited.

DOD Inconsistently Incorporates Leading Practices for Program Management in Its DTS Modernization

Effective program management is essential to successful modernization of large-scale systems like DTS because it ensures that programs are meeting cost, schedule, and performance goals and that risks are being managed efficiently. The applicable statute calls for DOD business systems to comply with the agency’s business enterprise architecture.[48] Additionally, effective program management incorporates the following four leading practices: describing the work necessary to modernize the legacy system; creating milestones to complete modernization; ensuring that metrics align with organization-wide goals and objectives; and ensuring repeatable processes are in place that support consistent and effective program oversight.[49]

DOD has fully addressed two, partially addressed two and not addressed one of the five leading practices and statutory requirements in this area. Table 4 shows the extent to which each of these practices and statutory requirements has been addressed by DOD’s DTS modernization efforts.

Table 4: Assessment of Defense Travel System (DTS) Modernization Against Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements Relevant to Program Management

|

Leading practice |

Assessment |

Description of assessment |

|

Comply with the agency’s enterprise architecture. |

○ |

The Department of Defense (DOD) has not demonstrated that the DTS modernization effort complies with a department-wide requirement to align modernizations with DOD’s enterprise architecture. Specifically, while DOD reported in its most recent annual certification results that it was in compliance with the department-wide enterprise architecture for the DTS system, related documentation did not contain details on the steps DOD took to achieve system-level compliance for DTS, or rationale for why it considered the requirement met.a |

|

Describe the work necessary to modernize the system. |

● |

DOD has defined the work necessary to modernize DTS. In particular, DOD entities with responsibility for performing this work, including the Office of the Chief Information Officer, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, and Defense Manpower Data Center, identified capability gaps and ways to track them to closure, and produced essential planning artifacts such as an implementation timeline, a maintenance release plan, and summaries of requirements gaps. |

|

Create milestones to complete the modernization. |

◐ |

DOD created a notional timeline that includes milestones for the planned functional, technical, and financial enhancements recommended by the Defense Travel Modernization Working Group that are planned to be included in DTS. However, these milestones lack specific dates and are not integrated into the overall implementation timeline. |

|

Ensure that metrics align with organization-wide goals and objectives. |

◐ |

DOD demonstrated its use of metrics to track its performance in achieving improvements to DTS. For example, monthly quality status reports including, among other things, information on any significant deficiencies noted and year-long trend analyses. However, these metrics are not directly linked to the goals or milestones in DOD’s high-level outline for the DTS modernization. |

|

Ensure repeatable processes are in place. |

● |

DOD has put in place repeatable processes for DTS modernization, using daily reviews and regular updates for management oversight. For example, the contract that provides technical support services for the sustainment and maintenance of DTS requires use of Agile development methodologies, continuous integration of software additions and changes, use of daily standup meetings, and regular updates to the Defense Manpower Data Center on the modernization’s progress. The DTS Program Management Office also conducts monthly sprint reviews focusing on areas such as security scans and defect fixes. |

Legend:

● = DOD fully addressed the leading practice.

◐ = DOD partially addressed the leading practice.

○ = DOD did not address the leading practice.

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107663

aIn July 2015, we recommended that DOD take additional action to improve management of its business enterprise architecture activities. Since then, DOD has initiated and restarted multiple efforts to improve its business enterprise architecture. See GAO, DOD Business Systems Modernization: Additional Action Needed to Achieve Intended Outcomes, GAO‑15‑627 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 16, 2015).

As mentioned above, DOD has partially addressed two and has not addressed one of the five leading practices and statutory requirements in this area. Specifically:

· DOD has not yet taken steps to ensure that its actions to improve DTS are in compliance with the department’s enterprise architecture. Although statute requires that all covered defense business systems—including DTS—are or will be in compliance with the department’s enterprise architecture,[50] DOD did not provide evidence specific to DTS demonstrating that this requirement has been met.

Officials in DOD’s Office of the Chief Information Officer stated that, while DOD produces department-wide reports that aggregate relevant information, this information is compiled into a spreadsheet that is not easily disaggregated to show compliance for an individual system such as DTS. However, high-level compliance assertions with DOD’s enterprise architecture are required for each individual system.[51] Without demonstrating the steps it took to achieve system-level compliance for DTS, or rationale for why it has achieved compliance, DOD risks less certainty in ensuring alignment between the DTS modernization and department goals and priorities.

· Although DOD established several interim milestone dates for completing its planned improvements to DTS, these dates are not reflected or tracked on the overarching implementation timeline. Additionally, DOD has not developed a well-defined schedule to complete the DTS modernization.

According to leadership from the Defense Travel Management Office and the program management team supporting the modernization effort, the department’s current notional timeline is a guideline for potential capability gap implementation and will be updated as the budget and funding dependencies are resolved. However, without integrating milestones into the overall implementation timeline or having a definitive completion schedule, DOD risks not meeting program schedule goals.

· The department has created metrics that align with and prioritize organization-wide goals and objectives by tracking the content of specific activities over the course of a release and showing DTS work progress through a cumulative flow diagram. However, these metrics are not clearly traceable to evolving organizational goals and priorities for the modernization.

DTS program management officials stated that metrics delivered to the customer are higher-level and focused on overall program functionality, such as progress to date or overall timeline. These metrics are different from internal team metrics geared towards internal performance measurements such as internal test results and time to complete subtasks. However, if metrics are not tailored to convey developers’ progress and achievements to internal and external customers, it can impede feedback and communication between both entities.

DOD Performed Outreach to Determine Stakeholder Needs on Its DTS Modernization

Effective stakeholder outreach is essential to successfully modernizing large-scale systems like DTS in cases where stakeholder priorities and system dependencies shift over time. Effective stakeholder outreach to understand evolving stakeholder needs incorporates the following five leading practices for interagency collaboration: (1) clarifying roles and responsibilities, (2) bridging organizational cultures, (3) including relevant participants, (4) leveraging resources, and (5) establishing written guidance to institutionalize best practices.

DOD has fully addressed these leading practices in its approach to DTS modernization.[52] Table 5 shows the extent to which each of these practices is addressed with regards to DOD’s efforts to improve DTS.

Table 5: Assessment of Defense Travel System (DTS) Modernization Against Leading Practices Relevant to Stakeholder Outreach

|

Leading practice |

Assessment |

Description of assessment |

|

Clarify roles and responsibilities. |

● |

The Department of Defense (DOD) has clarified roles and responsibilities for the modernization of DTS by establishing formal governance bodies, such as the Defense Travel Advisory Panel and Defense Travel Governance Board, to oversee system improvements and ensure alignment with enterprise-wide objectives. |

|

Bridge organizational cultures. |

● |

DOD has bridged organizational cultures by institutionalizing formal strategies that promote cross-agency cooperation and trust. These efforts include standing up the Defense Travel Advisory Panel and the Defense Travel Modernization Working Group, and adopting the Defense Travel Advisory Panel Charter, which outlines decision-making roles, voting procedures, and engagement protocols to support collaborative operations. |

|

Include relevant participants. |

● |

DOD has demonstrated its inclusion of relevant stakeholders in modernization activities. For example, DOD coordinates with contracting officers, as well as the Defense Manpower Data Center, which is responsible for analyzing the allocation of manpower and personnel with respect to mission needs, at weekly sustainment meetings. DOD has set up a variety of recurring meetings with DTS program participants to foster regular communication on status details for ongoing efforts. Mechanisms for stakeholder feedback are also incorporated into system development activities. |

|

Leverage resources and information. |

● |

DOD has leveraged resources to improve stakeholder outreach on its DTS improvements by assigning dedicated product owners, project managers, and development staff to incorporate user feedback into system improvements. |

|

Develop and update written guidance and agreements. |

● |

DOD has established written guidance to improve outreach to stakeholders, such as the components for which DTS will be implemented and their end users, by creating an updated business case analysis and a formal communication plan so that stakeholders are informed and engaged. |

Legend:

● = DOD fully addressed the leading practice.

◐ = DOD partially addressed the leading practice.

○ = DOD did not address the leading practice.

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107663

DOD has taken action to coordinate with stakeholders during the DTS modernization. Collectively, its efforts promote consistent coordination and enhance the likelihood of DOD achieving its DTS modernization goals. For instance, the department has clarified responsibilities by developing formal documentation that outlines roles, voting procedures, and dispute resolution processes; bridged organizational cultures through the adoption of cross-agency collaboration strategies; and increased the inclusion of relevant stakeholder participants by integrating user group feedback into system development.

DOD Has Not Consistently Included Key Users in Gathering and Tracking Requirements Over Time on the DTS Modernization

For successful system modernization, effective requirements management is critical for ensuring that new solutions meet user needs and expectations and to reduce the risks of cost overruns and project failures. Effective requirements management incorporates implementation of the following leading practices: (1) eliciting and prioritizing requirements; (2) balancing customer and user needs; and (3) managing requirements and ensuring bidirectional traceability.[53] Additionally, statute calls for DOD business systems to (4) have an acquisition strategy designed to eliminate or reduce the need to tailor commercial-off-the-shelf systems to meet unique requirements or interfaces, (5) streamline and minimize unique requirements and interfaces, and (6) validate requirements.[54]

DOD has fully addressed one, partially addressed two and not addressed three of these six leading practices and statutory requirements. Table 6 provides details on the extent to which DOD has implemented these leading practices or statutory requirements as part of the DTS modernization.

Table 6: Assessment of Defense Travel System (DTS) Modernization Against Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements Relevant to Requirements Management

|

Leading practice |

Assessment |

Description of assessment |

|

Elicit and prioritize requirements. |

◐ |

DOD has taken steps to elicit and refine requirements for DTS, for example through use of focus groups, regular meetings, and problem reporting processes to foster communications across stakeholders, as part of updating system features such as travel lodging options and user reimbursement calculations. However, DOD has not demonstrated a consistent process for receiving stakeholder feedback on new requirements. DOD also could not demonstrate how user feedback is systematically evaluated and converted into actionable non-functional requirements, in areas such as security and privacy. |

|

Balance customer and user needs when coordinating implementation of requirements. |

◐ |

DOD makes decisions on which system updates to prioritize based on factors such as impact on end users and level of urgency for which the update is needed. A review team made up of government and contractor staff convenes regularly to review and rank these items, and meeting notes show what was discussed and decided. However, DOD did not document the specific factors that the review team considered to determine their relative value. Insufficient consideration of the relative value of work performed is often an indication that a product owner is not prioritizing requirements throughout development and could be developing functionality that is not immediately necessary. |

|

Manage requirements and ensure bidirectional traceability. |

● |

DOD has produced artifacts that demonstrate structured processes for tracking system requirements changes and aligning them with project goals. For example, DOD manages system requirements changes by tracking the lifecycle of proposed system modifications. This system includes key details on the initiation, content, and approval of each change that enable DOD to monitor its status and progression through implementation. Additionally, the DTS change management plan outlines formal processes for controlling changes, ensuring they trace back to modernization objectives. Program documentation, such as a project schedule and documented lessons learned, further incorporate requirement tracking activities into planning and implementation. |

|

Have an acquisition strategy designed to eliminate or reduce the need to tailor commercial off-the-shelf systems to meet unique requirements or interfaces. |

○ |

DOD reported compliance with three statutory requirements for the DTS system: to consider an acquisition strategy that reduced the need to tailor commercial off-the-shelf systems to meet unique requirements or interfaces, to streamline and minimize unique requirements, and to validate system requirements. However, for each of these three requirements, DOD documentation did not include details on the steps it took to achieve system-level compliance for DTS, or rationale for why it considered the requirements met. A DOD official noted challenges in capturing and demonstrating the prioritization of non-functional requirements and acknowledged that aspects of their requirements refinement process are not fully documented. |

|

Streamline and minimize unique requirements and interfaces. |

○ |

|

|

Validate requirements. |

○ |

Legend:

● = DOD fully addressed the leading practice.

◐ = DOD partially addressed the leading practice.

○ = DOD did not address the leading practice.

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. | GAO‑26‑107663

As mentioned above, DOD has partially addressed two and not addressed three of the six leading practices and statutory requirements in this area. Specifically:

· DOD gathered input on stakeholder requirements through focus groups, monthly meetings, and travel system feedback sessions, and relies on coordination with DTMO and the DTS program management office to adjust implementation priorities as needed. However, the department has not demonstrated a consistent process for eliciting stakeholder feedback on new requirements. For example, DOD documentation does not include information on how insights from focus groups were translated into formal requirements or prioritized for development. DOD documentation also does not include information on ways in which user feedback is systematically evaluated and converted into actionable requirements, including for non-functional requirements, such as security and privacy requirements.

An official in the Defense Manpower Data Center noted challenges in capturing and demonstrating the prioritization of non-functional requirements and acknowledged that aspects of their requirements refinement process are not fully documented. Unless DOD takes steps to more completely capture all requirements, it risks its solutions not meet user and stakeholder expectations.

· DOD has taken steps to balance customer and user needs by documenting its requirements valuation and prioritization process—including through meeting minutes that list issue summaries, user impact, workarounds, and resulting prioritization decisions. However, DOD documentation does not sufficiently explain how the team consistently measures or compares the relative value of different work items. This gap means that, though urgent needs may be addressed, there is no clear indication that the product owner uses a value-based framework to ensure the most beneficial user needs are prioritized and reflected in the functionality it develops.

Officials in the DTS program management office attributed this deficiency to the lack of a defined, consistent mechanism for comparing and determining the relative value of different project tasks. Without developing a more consistent framework for determining the relevant value of project task elements, DOD risks prioritizing less-valuable user needs as part of its modernization of DTS.

· DOD annual certification results report that DTS is in compliance with statutory requirements for developing an acquisition strategy that minimizes customization of systems, eliminating outdated or duplicative requirements, and validating system requirements. However, DOD documentation does not detail how compliance was assessed, or the steps DOD took to achieve compliance.

Officials in DOD’s Defense Support Services Center attributed these gaps to a reliance on aggregated reporting that obscures compliance details for individual systems like DTS. Without documenting details of how it demonstrated compliance with these requirements, DOD faces uncertainty in setting up a process to ensure continued compliance for future business system modernization efforts.

DOD Has Not Fully Addressed Selected Leading Practices in Its Overall Business Systems Modernization

As mentioned previously, DOD has initiated a variety of efforts to improve its ability to modernize its business systems in response to long-standing challenges. DOD has also continued to make progress on ongoing improvement efforts, as previously reported by GAO.

Similar to its travel system modernization, DOD business system modernization activities could benefit from the incorporation of selected leading practices. DOD has fully addressed 12 of 23 selected leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to establishing sufficient department-wide priority and leadership, incorporating leading program management practices, performing sufficient outreach to and collaboration with key stakeholders, and managing and tracing user and stakeholder requirements. However, DOD did not fully address 11 other selected practices and requirements.

GAO has also identified leading practices for conducting agency reforms that are applicable to DOD’s business systems modernization efforts. DOD policies and guidance fully addressed two and partially addressed two of four leading practices for conducting agency reforms. Specifically, DOD policies and guidance generally address goals and outcomes of department reforms, and a process for developing these reforms, but DOD has not completed key documentation related to implementing reforms of its business systems modernization efforts.

DOD Has Several Efforts Underway to Modernize Its Business Systems

DOD has initiated several new efforts to improve the management of its business systems in response to long-standing challenges. These efforts, overseen by the Defense Business Council (DBC) and requiring approval from the Chief Information Officer (CIO), include the following:[55]

· creation of a new DOD “high-risk” designation for business systems that requires special approvals to continue to the next phase of development;[56]

· an update to key policy documentation, such as DOD’s instruction for business systems requirements and acquisition, and two policies for IT portfolio management;

· development of a new strategy for improvement of IT department-wide, including development of joint capabilities, modernization of IT networks, optimization of governance processes, and improvement and enhancement of the cyber workforce;

· creation of a “playbook”, or ready-made step-by-step implementation guidance, for software development, security, and operations; and

· creation of a dashboard showing department-wide certification status for business systems.

DOD has also continued to make progress in implementing further business system improvements as we have previously reported, such as

· developing and updating a policy framework for adaptive acquisition of business systems in June 2022;[57]

· making updates and enhancements to a certification guide to be used for each new defense business system in October 2024;[58] and

· planning to complete a business enterprise architecture guidebook, which is intended to strategically align DOD’s business strategy, processes, and its individual modernization efforts to achieve department-wide goals. The Defense Business Council also plays a key role in overseeing this strategic alignment.

DOD Has Not Fully Addressed Selected Leading Practices Relevant to Modernizing Its Business Systems

As stated above, shortfalls in central decision-making, program management, stakeholder outreach, and requirements gathering were primary factors in the abandonment of DOD’s MyTravel modernization. Our prior work established that DOD has experienced longstanding issues relating to each of these factors in conducting its business systems modernization efforts.[59]

The department has fully addressed 12 and partially addressed 11 of 23 selected leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to the four primary factors in improving its department-wide business system modernization efforts. For example, DOD has issued policy guidance to establish a central decision-making authority among stakeholders, but policies did not require the establishment of metrics that align with organization-wide goals and objectives. Figure 4 shows the extent to which DOD has addressed these selected leading practices and statutory requirements relevant to its efforts to modernize its business systems.

Figure 4: Extent to Which Department of Defense (DOD) Policies and Guidance Incorporate Selected Leading Practices and Statutory Requirements