DEFENSE RESEARCH AND ENGINEERING

Action Needed to Improve Management and Oversight of Technology Investments

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact Shelby S. Oakley at oakleys@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) seeks to outpace foreign adversaries’ capabilities by quickly adopting innovative technologies. The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) helps DOD reach that goal.

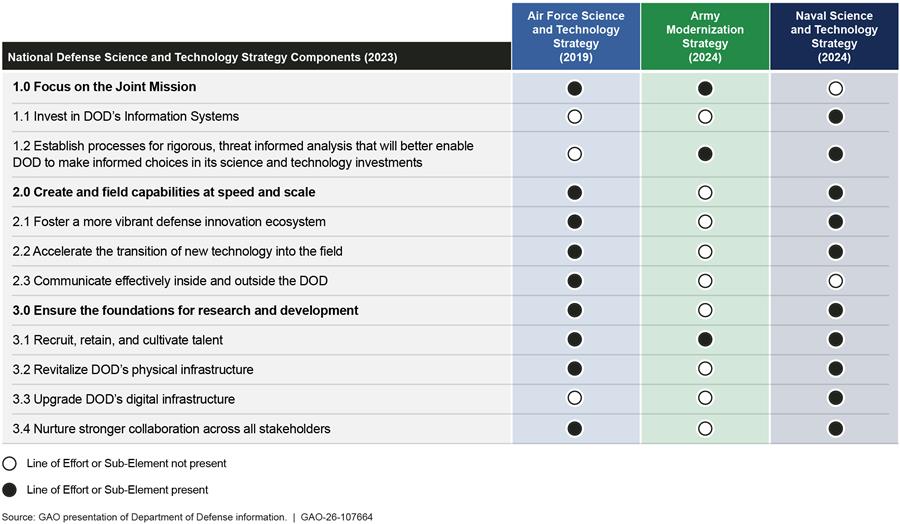

OUSD(R&E) is generally implementing processes and programs, consistent with its authorities to manage and oversee innovation-related investments. For example, it developed a National Defense Science & Technology Strategy in accordance with the 2022 National Defense Strategy. The military departments have department-focused strategies, but the extent to which those strategies are updated and aligned with DOD’s strategy varies. Consequently, DOD risks the military departments pursuing technologies that do not match its vision.

Further, OUSD(R&E) faces several challenges ensuring that the military departments are well-positioned to quickly deliver technologies to the warfighter. For example, OUSD(R&E):

· has not, according to officials, issued guidance for the development of Critical Technology Area roadmaps, including identifying stakeholders who should be involved or identifying the content to include in those roadmaps.

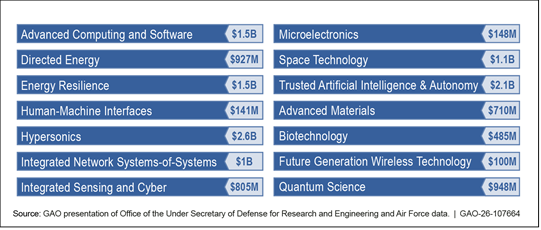

· has not determined how the military departments should balance investments in critical technologies between the joint force and military department priorities. This is because it has not provided guidance to the military departments on the amount of investment in each critical technology area to align with corresponding roadmaps, despite military department investments in those critical technologies, as shown below.

· is limited in its ability to influence military departments’ budgets to ensure they align with DOD-wide priorities through the annual budgeting process. This is because OUSD(R&E) does not have statutory authority to certify the military departments’ budget. Having this authority would better position DOD to ensure priorities align.

Without addressing these challenges, OUSD(R&E) risks being unable to effectively execute its responsiblities to manage and oversee technology efforts.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD requested nearly $180 billion in the President’s Fiscal Year 2026 budget for managing, overseeing, and improving technology. Members of Congress have raised questions about OUSD(R&E)’s ability to oversee this technology as a counter to the rising threat of adversaries such as China and Russia.

The House report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review how OUSD(R&E) manages, oversees, and improves DOD’s innovation investments and outcomes. This report evaluates (1) the extent to which OUSD(R&E) has taken steps to implement its authorities, and (2) the extent to which these authorities position it to effectively manage these investments.

GAO reviewed DOD documentation and data as well as selected legislative provisions. GAO also interviewed officials from OUSD(R&E) and the military departments.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider granting OUSD(R&E) budget certification authority. GAO is also making three recommendations to DOD, including that it direct each military department to develop science and technology strategies that align with OUSD(R&E)’s DOD-wide science and technology strategy to the maximum extent practicable; issue guidance for developing Critical Technology Area roadmaps; and provide guidance to the military departments on the amount of investment in each critical technology area needed to ensure alignment to the maximum extent practicable with corresponding roadmaps. DOD agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

Abbreviations

APFIT Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies

ASD(CT) Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies

CPM Capability Portfolio Management

CTA critical technology area

DIA Defense Innovation Acceleration

DOD Department of Defense

JROC Joint Requirements Oversight Council

NDAA National Defense Authorization Act

NDS National Defense Strategy

OUSD(A&S) Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment

OUSD(R&E) Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering

POM program objective memorandum

PPBE planning, programming, budgeting, and execution

RDER Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve

RPP Rapid Prototyping Program

RDT&E Research, Development, Test and Evaluation

S&T science and technology

TMTR Technology Modernization Transition Review

TTAG Transition Tracking Action Group

USD(A&S) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment

USD(AT&L) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics

USD(Comptroller) Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)

USD(R&E) Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 5, 2026

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense (DOD) seeks to outpace foreign adversaries’ capabilities by quickly adopting innovative technologies. The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) has responsibility for managing, overseeing, and improving technology development efforts across DOD to help reach that goal. In the President’s fiscal year 2026 budget submission, DOD requested nearly $180 billion for research, development, test and evaluation (RDT&E) activities aimed, in part, at developing technologies that meet both the short-term and long-term needs of current and future warfighters. This request included more than $20 billion for science and technology (S&T) activities and more than $40 billion for advanced component development and prototyping efforts, funding for which OUSD(R&E) is responsible for providing management and oversight.[1]

Members of Congress have raised questions about OUSD(R&E)’s ability to manage and oversee the Department’s efforts to mature and quickly field critical technologies needed by the warfighter to counter the rising threat of adversaries such as China and Russia. The House Report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review the functions of OUSD(R&E) and recommend any policy and statutory changes needed to better position OUSD(R&E) to manage, oversee, and improve DOD’s innovation investments and outcomes.[2] This report specifically addresses (1) the extent to which OUSD(R&E) implemented the authorities granted to it under statute and in policy for managing, overseeing, and improving innovation-related investments across DOD, including joint efforts; and (2) the extent to which these authorities position OUSD(R&E) to effectively manage these investments.[3]

To determine the extent to which OUSD(R&E) implemented its authorities related to technology development and technology transition, we identified and reviewed the statutory authorities granted to OUSD(R&E) for those purposes, including in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Years 2017, 2020, 2021, and 2022.[4] We also reviewed DOD Directive 5137.02, which details the roles and responsibilities of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. Specifically, we reviewed selected roles and responsibilities related to technology development and technology transition. However, we did not review or assess OUSD(R&E)’s authorities that did not directly address these areas, such as workforce management or international cooperation. We subsequently reviewed and assessed how those authorities were implemented, including those authorities supporting joint efforts. Specifically, we assessed OUSD(R&E)’s implementation of authorities and responsibilities to:

· issue a National Defense Science and Technology (S&T) Strategy;

· identify critical technologies and develop related roadmaps[5]; and

· manage rapid prototyping efforts.

We also reviewed and assessed DOD and military department documents related to technology development and transition. For example, at the DOD-level, this included:

· The 2023 National Defense Science and Technology Strategy;

· DOD Directive 7045.20, Capability Portfolio Management;

· Transition Tracking Action Group Charter and Transition Tracking Action Group Implementation Plan; and

· Various DOD Memoranda.

At the military department-level, this included:

· The 2019 Air Force Science and Technology Strategy;

· The 2024 Army Modernization Strategy;

· The 2024 Naval Science and Technology Strategy;

· Air Force Policy Directive 61-1, Management of the Science and Technology Enterprise;

· Army Regulation 70-1, Army Operation of the Adaptive Acquisition Framework; and

· SECNAV Instruction 5400.15D, Department of the Navy Research and Development, Acquisition, Associated Life-Cycle Management, and Sustainment Responsibilities and Accountability.

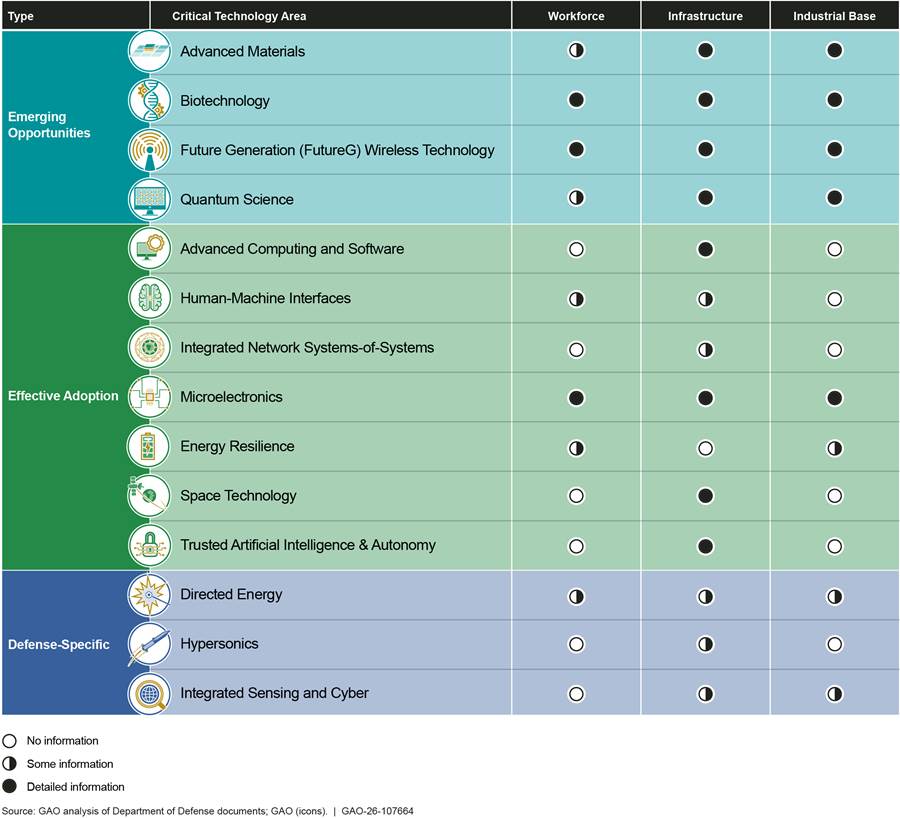

We also reviewed the 14 Critical Technology Area roadmaps to determine the extent to which these roadmaps included information related to three topics: workforce, infrastructure, and the industrial base. Although the statute requiring OUSD(R&E) to develop these roadmaps does not require information about these topics to be included, we selected them because the senior officials responsible for the critical technologies are required to conduct annual assessments on these topics in support of the roadmaps. We subsequently determined the extent to which the roadmap contained information about each topic.

For each topic, a roadmap was considered to have detailed information if it mentioned three or more of the following:

· Workforce: current workforce size or characteristics, skill gaps in the current workforce, activities to address skill gaps, such as academic or industry partnerships, recruitment, retention, or near-, mid-, and far-term goals.

· Infrastructure: laboratory facilities, software factories, testing capabilities, standards and protocols, legacy software and system, cloud computing resources, tools used to collect and analyze data or otherwise support digital engineering, electromagnetic spectrum, near-, mid-, and far-term goals.

· Industrial base: supply chain, strengths or weaknesses of domestic industry, comparison to international peers, specific potential investments, patents and intellectual property, near-, mid-, and far-term goals.

For each topic, a roadmap was considered to have some information if it mentioned one or two of the above. For example, a roadmap would be considered to have some information about workforce if recruitment was mentioned but nothing else was included.

A roadmap was considered to have no information about a topic if it was listed as an issue to be addressed in the future or in other documents; key words listed above for the topic did not appear in the roadmap; or the topic appeared in the roadmap with no additional information. For example, a roadmap would be considered to have no information about infrastructure if the word “infrastructure” appeared on a page without additional text or information.

To determine the extent to which these authorities position OUSD(R&E) to effectively manage these investments, we met with OUSD(R&E) officials to discuss any challenges they have encountered in implementing the above authorities and responsibilities. We discussed the extent to which these challenges were the result of insufficient authority found in statute or policy. We also reviewed and assessed existing statute and policy governing OUSD(R&E) and discussed these topics with OUSD(R&E) officials.

Finally, for both objectives, we met with officials from OUSD(R&E) and the military departments to discuss OUSD(R&E)’s efforts to manage, oversee, and improve innovation-related investments within DOD. We also discussed how OUSD(R&E) and the military departments collaborate on technology development and transition efforts, including those for the joint force. From OUSD(R&E), this included officials from the following:

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies;

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Mission Capabilities;

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Science & Technology;

· Office of Developmental Test, Evaluation & Assessment;

· Office of Systems Engineering & Architecture; and

· Transition Tracking Action Group (TTAG).

From the military departments, this included officials from the following:

· Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Science, Technology, and Engineering;

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisitions, Logistics, and Technology; and

· Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation.

We also met with several Principal Directors from OUSD(R&E), who manage and oversee department-wide activities for their respective CTAs, to discuss their experiences developing CTA roadmaps. Finally, we met with officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) to discuss OUSD(R&E)’s role in the DOD budgeting process, among other topics.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering

In February 2018, DOD’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD(AT&L)) was dissolved and its duties were divided among two newly established offices—OUSD(R&E) and the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)).[6] The conference report accompanying the law containing this provision highlighted the need to elevate the mission of advancing technology and innovation within DOD and foster distinct technology and acquisition cultures to better deliver superior technological capabilities to the warfighter. Further, congressional conferees noted that they expected that OUSD(R&E) would take risks, press the technology envelope, test and experiment, and have the latitude to fail, as appropriate.[7]

OUSD(R&E)’s initial duties and responsibilities identified by Congress included:

· Serving as DOD’s Chief Technology Officer with the mission of advancing technology and innovation for the warfighter;

· Establishing policies on, and supervising, all defense research and engineering, technology development, technology transition, prototyping, experimentation, and developmental testing activities and programs, including the allocation of resources for defense research and engineering, and unifying defense research and engineering efforts across DOD; and

· Serving as the principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense on all research, engineering, and technology development activities and programs in DOD.[8]

Congress further clarified and provided additional roles and responsibilities for OUSD(R&E) in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2020, such as requiring OUSD(R&E) to administer DOD’s manufacturing technology program. It also removed language giving OUSD(R&E) authority for establishing policies and supervising the allocation of resources for defense research and engineering.[9] Table 1 provides a summary of selected legislative provisions passed by Congress since 2019 affecting OUSD(R&E)’s roles and responsibilities.

Table 1: Selected Legislative Provisions Affecting the Roles and Responsibilities of OUSD(R&E) Since 2019

|

National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) |

Section and title of provision |

Description of legislative provision |

|

William M. (Mac) Thornberry NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 |

Section 217. Designation of senior officials for critical technology areas supportive of the National Defense Strategy |

The Under Secretary of Defense for Research & Engineering shall (1) identify technology areas that the Under Secretary considers critical for the support of the National Defense Strategy; and (2) for each such technology area, designate a senior official of the Department of Defense to coordinate research and engineering activities in that area. |

|

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 |

Section 211. Codification of National Defense Science and Technology Strategy |

The Secretary of Defense shall develop a strategy (1) to articulate the science and technology priorities, goals, and investments of the Department of Defense; (2) to make recommendations on the future of the defense research and engineering enterprise and its continued success in an era of strategic competition; and (3) to establish an integrated approach to the identification, prioritization, development, and fielding of emerging capabilities and technologies. Not later than February 1 of the year following each fiscal year in which the National Defense Strategy is submitted, the Secretary of Defense shall submit…a report that includes an updated version of the strategy. |

|

Section 834. Pilot Program to Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies |

Subject to availability of appropriations, the Secretary of Defense shall establish a competitive, merit-based pilot program to accelerate the procurement and fielding of innovative technologies by, with respect to such technologies (1) reducing acquisition or life-cycle costs; (2) addressing technical risks; (3) improving the timeliness and thoroughness of test and evaluation outcomes; and (4) rapidly implementing such technologies to directly support defense missions.a |

|

|

Section 903. Enhanced Role of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering on the Joint Requirements Oversight Council |

Amends title 10, section 181 of U.S. Code to designate the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering as the Chief Technical Advisor to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council. The Under Secretary shall provide assistance in evaluating the technical feasibility of requirements under development; and shall identify options for expanding or generating new requirements based on opportunities provided by new or emerging technologies. |

Source: GAO analysis of William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283 (2021) and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-81 (2021). | GAO‑26‑107664

aSections 211 and 834 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 are directed at the Secretary of Defense. However, these responsibilities have been delegated to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)).

DOD Directive 5137.02, issued in 2020, details many of OUSD(R&E)’s authorities. It specifies dozens of key functions and responsibilities and defines the authorities of OUSD(R&E) and its relationships with other senior DOD officials.[10] The responsibilities include managing the DOD science and technology portfolio to address near- and far-term capability gaps against emerging threats; and ensuring that DOD technical infrastructure, scientific and engineering capabilities, and associated resources align with DOD priorities. Additionally, the directive states that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering is also responsible for identifying and defining DOD’s modernization priorities, leading prototyping initiatives, and developing and publishing an overarching DOD-wide science and technology strategy.

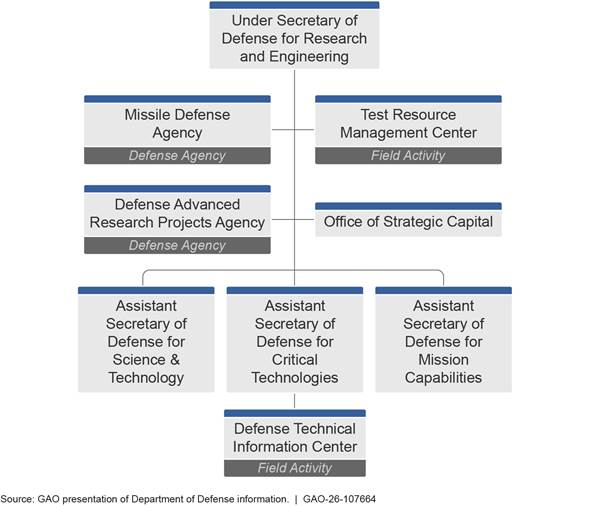

Organizational Structure of OUSD(R&E)

OUSD(R&E) has undergone several organizational changes since being established in 2018. Most recently, in July 2023, DOD announced the establishment of three new Assistant Secretary of Defense positions within OUSD(R&E)—Assistant Secretary of Defense for Science & Technology; Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies; and Assistant Secretary of Defense for Mission Capabilities. These three Assistant Secretaries of Defense replaced the previous Deputy Chief Technology Officer positions.

The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering also oversees two defense agencies—the Missile Defense Agency and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—and two field activities—the Test Resource Management Center and the Defense Technical Information Center as well as the Office of Strategic Capital. Figure 1 illustrates the organizational structure of OUSD(R&E), as of December 2025.

Figure 1: Organizational Structure of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E))

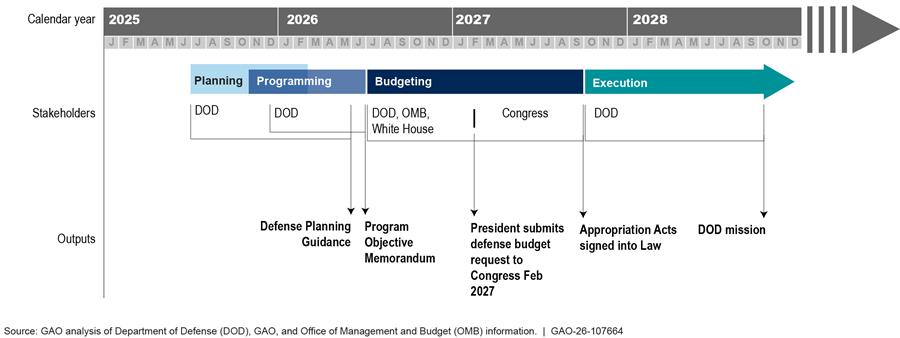

Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Overview

Technology development investments, like every other good and service DOD acquires, follow DOD’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) process.[11] The PPBE process for technology development investments includes the following stages:

· Planning. DOD leadership, in guidance and planning documents, identifies strategic priorities, weapon system requirements, and adversarial threats. Collectively, these serve as DOD’s broad requirements for technology development.

· Programming. Research and engineering organizations consider those requirements and propose technology development projects to address them. Proposed projects and associated costs are documented in Program Objective Memorandums (POM). Each organization, such as the military departments’ laboratories or warfare centers, is tasked with determining which projects to propose in the POM while maintaining balance across investment portfolios; as well as maintaining an appropriate mix of funding, based on budget activity, for incremental or disruptive technology efforts. POM documents are reviewed by senior officials across DOD, such as the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, who have a role in prioritizing technology development investments.

· Budgeting. Each research and engineering organization’s POM is used to formulate its respective organization’s Budget Estimate Submission, which outlines the total funding needed, including how much it will need by budget activity. After the President’s budget is submitted, Congress enacts an appropriation, and the President signs it into law. Once funds are appropriated, each research and engineering organization is provided funding for the approved projects.

· Execution. Research and engineering organizations carry out funded projects.

Figure 2 illustrates the notional time frame for DOD’s PPBE process.

Figure 2: Notional Time Frame for the Department of Defense’s (DOD) Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Process

Previously, we reported that it can take almost 2 years from the time a project is proposed in the POM to the time it is funded. DOD officials have expressed the need for greater flexibility with initiating new projects because the pace of technology development can be rapid and planning for technology development spending 2 years in advance can hinder innovation. However, as we previously reported, the PPBE process provides Congress with the information it needs to maintain oversight.[12]

Several officials and organizations within DOD are involved in the PPBE process. These include:

· The USD(Comptroller)—the principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense for budgetary and fiscal matters—serves as DOD’s chief financial officer and administers the budget and execution phases of the PPBE process. The powers and duties of this office include financial management, accounting policy and systems, budget formulation and execution, and contract and audit administration.

· Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy—responsible for acquisition, technology, and logistics—generally oversee or have responsibilities related to R&D. The powers and duties include establishing policies and providing oversight for the military departments’ research, engineering, technology development, and acquisition activities.

· Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy—responsible for financial management—serve as comptrollers of the military departments. The powers and duties of these offices generally include RDT&E budget formulation, the presentation and defense of the budget through the congressional appropriation process, budget execution and analysis, reprogramming actions, and appropriation fund control/distribution.

· Further, other stakeholders have equity in the PPBE process, such as—USD(Policy), the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation, and the military department laboratories and warfare centers.

OUSD(R&E) Is Generally Implementing Programs and Processes Consistent with Its Authorities to Manage and Oversee Technology Investments

In response to its statutory and policy authorities, OUSD(R&E) enacted programs and processes to manage and oversee technology investments. For example, the office developed and released a National Defense Science and Technology Strategy. Additionally, the military departments developed their own science and technology strategies, but these strategies do not fully align with DOD’s strategy. OUSD(R&E) also designated senior officials who oversee critical technology areas (CTA); and it initiated processes for conducting technology reviews and collecting technology transition data. OUSD(R&E) is also administering several prototyping programs, meant to quickly deliver technologies to the warfighter.

OUSD(R&E) Issued a National Defense Science and Technology Strategy, but Military Departments’ Science and Technology Strategies Do Not Fully Align with That Strategy

OUSD(R&E) issued the 2023 National Defense S&T Strategy following the release of the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS), as required by statute.[13] In a February 2022 memorandum, the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering wrote that the National Defense S&T Strategy would be anchored by three strategic pillars—mission focus, foundation building, and succeeding through teamwork. These pillars were subsequently translated into three strategic lines of effort to establish the ways to sharpen DOD’s competitive edge: (1) focus on the Joint Mission; (2) create and field capabilities at speed and scale; and (3) ensure the foundation for research and development.[14]

The 2023 National Defense S&T Strategy states that these strategic lines of effort are needed to solve increasingly complex security challenges that involve science and technology, such as countering cyberattacks, defending against advanced offensive technologies, and addressing biological threats. Further, the National Defense S&T Strategy states that it is meant to align new mechanisms for supporting research and development with more effective pathways for acquisition and sustainment.

The Air Force, Army, and Navy have also issued their own department-level S&T strategies, although the requirements for developing and updating those strategies vary (see table 2).

|

Military department |

Policy or statute |

Requirement |

Year of current Science and Technology Strategy |

|

|||||||

|

Air Force |

Department of the Air Force Policy Directive 61-1 Management of the Science and Technology Enterprise |

“The Department of the Air Force will conduct research and development and manage the science and technology enterprise to meet the 2018 National Defense Strategy requirement to provide transformational strategic capabilities driven by scientific and technological advances. The Secretary of the Air Force will set the overall strategic direction for the Department of the Air Force Science and Technology Program through the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and the Chief of Space Operations and approve the Department’s science and technology strategy.” The directive does not require the Air Force’s science and technology strategy to be updated on a regular basis. |

2019 |

|

|||||||

|

Military department |

Policy or statute |

Requirement |

Year of current Science and Technology Strategy |

||||||||

|

Army |

Sec. 1061 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018; and Army Regulation 70-1 Army Operation of the Adaptive Acquisition Framework |

“The Secretary of the Army shall develop a modernization strategy for the total Army.” “The strategy required...shall include the following: (1) a comprehensive description of the future total Army...; (2) mechanisms for identifying programs of the Army that may be unnecessary, or do not perform according to expectations, in achieving the future total Army; (3) a comprehensive description of the manner in which the future total Army intends to fight and win as part of a joint force engaged in combat across all operational domains; (4) a comprehensive description of the mechanisms required by the future total Army to maintain command, control, and communications and sustainment; (5) a description of the combat vehicle modernization priorities of the Army over the next 5 and 10 years; the extent to which such priorities can be supported at current funding levels within a relevant time period; the extent to which additional funds are required to support such priorities; how the Army is balancing and resourcing such priorities with efforts to rebuild and sustain readiness and increase force structure capacity over this same time period; and how the Army is balancing its near-term modernization efforts with an accelerated long-term strategy for acquiring next generation combat vehicle capabilities.” “Not later than April 30, 2018, the Secretary shall submit to the congressional defense committees the strategy required.” The statute did not require the Army to update its modernization strategy on a regular basis, though the Army did so in 2021 and 2024. “The Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisition, Logistics and Technology) (ASA(ALT)) ...designates the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Technology (DASA(R&T)) as the Army Science and Technology Executive. On behalf of the ASA(ALT), the Army Science and Technology Executive...Develops an overarching Army S&T Strategy, informed by the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7 Threat-Based Strategy.” |

2024 |

|

|||||||

|

Military department |

Policy or statute |

Requirement |

Year of current Science and Technology Strategy |

||||||||

|

Navy |

SECNAV Instruction 5400.15D Department of the Navy Research and Development, Acquisition, Associated Life-Cycle Management, and Sustainment Responsibilities and Accountability |

“The Chief of Naval Research shall coordinate with the Naval Research, Development, Test & Evaluation Corporate Board, composed of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, and additional 4-Star equivalents for overall guidance in shaping the investment science and technology portfolio and validating the science and technology investment and execution strategy.” The instruction does not require the Navy’s science and technology strategy to be updated on a regular basis. |

2024 |

|

|||||||

Source: GAO presentation of military department information and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-91, 1061 (2017). | GAO 26 107664

Note: Section 1061 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 required the Army to develop a modernization strategy. However, this statutory requirement did not explicitly require the Army to consider science and technology issues as part of that modernization strategy, nor did it require the Army to issue updates to the modernization strategy. Army officials, however, stated that the Army’s longer-term outlook for science and technology is the Army Modernization Strategy.

Although there is a requirement for the Army to develop a science and technology strategy, as referenced in the table above, a senior Army official stated that this strategy is currently used internally to support the Army’s Program Objective Memorandum as part of the annual budgeting process. The Army Modernization Strategy, however, represents the Army’s science and technology outlook over a longer time period.

There is no requirement in policy or statute for the Army to update its modernization strategy, nor is there a requirement in policy or statute for the Air Force or Navy to update their department-level strategies even though Congress requires DOD to update the National Defense S&T Strategy following any update to the NDS.[15] Instead, updates to these strategies are at the discretion of military department senior leadership. Air Force officials stated the Air Force S&T strategy is updated when directed by leadership, or if there are changes to national security threats. However, the Air Force has not updated the strategy since 2019, even though we have observed changes in presidential administrations and their national security priorities, as well as new and emerging conflicts and national security threats. Similarly, Army officials stated that, due to recent changes with DOD leadership, they do not know when their existing modernization strategy will be updated.

Further, there is no requirement, in policy or statute, for the military departments to align their department-level strategies to the National Defense S&T Strategy. Our analysis found several areas where the military departments’ S&T strategies do not align with DOD’s overarching S&T strategy even though the National Defense S&T Strategy states the defense research and engineering enterprise needs to work together to solve national security challenges. For example:

· The Army’s 2024 Modernization Strategy does not address the need to create and field capabilities at speed and scale or discuss how to ensure the foundations for research and development, such as investing in physical or digital infrastructure. Our analysis found that the Army’s Modernization Strategy generally did not align with the 2023 National Defense S&T Strategy. We recognize that Congress did not specifically require the Army to address S&T issues in its modernization strategy; nonetheless, the Army maintains that its modernization strategy serves as its S&T strategy.

· While our analysis found that the 2024 Naval S&T Strategy generally aligned with the 2023 National Defense S&T Strategy, it does not reference the joint force despite the National Defense S&T Strategy stating that any future fight will be a joint fight. The National Defense S&T Strategy further noted that the joint mission—a specific line of effort in the strategy—is a collaborative mission that requires all of DOD, including the combatant commands and the military departments, to come together. Navy officials stated that they put a greater focus on specific areas of need for the Navy and incorporated Secretary of Navy strategy guidance and Marine Corps planning documents when developing the Naval S&T Strategy.

Figure 3 provides additional detail on the extent to which the military departments’ S&T strategies align with the National Defense S&T Strategy.

Figure 3: Alignment of Military Departments’ S&T Strategies to the 2023 National Defense S&T Strategy Lines of Effort and Related Sub-Elements

Note: Army officials stated that the Army’s longer-term outlook for science and technology (S&T) is the Army Modernization Strategy.

We found in our prior work that defining common outcomes is a leading practice for successful interagency collaboration. Key considerations for this practice include identifying crosscutting challenges or opportunities; clearly defining short- and long-term outcomes; and reassessing and updating outcomes, as needed.[16] Additionally, our prior work has also found the importance of straightforward linkages and alignment in strategic plans. Straightforward linkages provide direct alignment between both strategic goals and strategies and an agency’s ability to achieve those goals. Aligned strategies, however, can increase interagency collaboration by helping agencies develop mutually reinforcing plans that help determine actions to implement said strategies.[17] Further, DOD has also noted the importance of developing and issuing strategic plans to help shape policy and investments in other DOD-wide strategies such as space and manufacturing technology.

Updating and aligning the military departments’ S&T strategies to the maximum extent practicable with the National Defense S&T Strategy would allow the military departments and OUSD(R&E) to ensure a common vision for technology development across DOD. Without a requirement to develop and issue military department science and technology strategies that align with the National Defense S&T Strategy, and subsequently updating those strategies as needed, the military departments risk pursuing technologies that do not match the objectives of the NDS.

OUSD(R&E) Has Processes for Identifying Technology Needs of the Joint Force

OUSD(R&E) identifies the technology needs of the entire DOD, including those of the Air Force, Army, and Navy, through various means including by developing Critical Technology Area roadmaps, Technology Modernization Transition Reviews, and other data collection efforts, and by serving as the Chief Technical Advisor to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council.

Critical Technology Area Roadmaps

OUSD(R&E) has the responsibility for identifying and defining DOD’s modernization priorities and developing department-wide road maps for research and engineering investments in these areas.[18] In 2021, Congress required that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering identify technology areas that they considered critical for the support of the NDS. The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering was required to (1) designate a senior official to coordinate research and engineering activities and develop research and technology development road maps for each CTA; and (2) annually report to the congressional defense committees on the progress of these CTAs.[19] In a February 2022 memorandum, the Under Secretary announced the 14 CTAs.[20] According to the Under Secretary, these CTAs are vital to maintaining national security, support the NDS, and address the needs of the joint force. Eleven of these technologies had previously been identified by the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering as modernization efforts (see fig. 4).[21]

Figure 4: Critical Technology Areas Identified by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E))

Note: Emerging opportunities are considered technology areas of early-stage development; effective adoption technology areas are those technologies where there is vibrant existing commercial activity; and defense-specific technologies are areas where the Department of Defense must take the lead in the research and development to ensure leap-ahead capabilities development.

In the February 2022 memorandum, the Under Secretary noted that the CTAs were vital to maintaining the United States’ national security and represent the approaches required to advance technologies crucial to meeting the NDS. The memorandum also stated that by focusing efforts and investments into these 14 CTAs, DOD would accelerate transitioning key capabilities to the military departments and combatant commands. Finally, the memorandum stated that as DOD’s technology strategy evolved and technologies changed, OUSD(R&E) would update its critical technology priorities.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies (ASD(CT)) generally manages OUSD(R&E)’s CTAs and the corresponding CTA roadmap process.[22] According to a senior OUSD(R&E) official, OUSD(R&E) wants to align annual updates to the CTA roadmaps with the release of the President’s Budget submission. In doing so, decision-makers will have better insight into investments in the CTAs.

Technology Transition and Data Collection

The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, in their role as DOD’s Chief Technology Officer and principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense on all research, engineering, and technology development activities and programs in the department, also conducts and chairs Technology Modernization Transition Reviews (TMTR). TMTRs are a part of DOD’s Capability Portfolio Management (CPM) process. The objective of the CPM process, which also includes the OUSD(A&S) and the Joint Staff, is to align investments, requirements, interoperability, designs, and acquisitions of related capabilities across DOD.[23]

OUSD(R&E) officials stated that TMTRs essentially serve as technology inventories to help OUSD(R&E), OUSD(A&S), and the Joint Staff identify the technologies they have and those needed to fulfill capability gaps.[24] DOD intends for the reviews to enable the department to innovate, develop, and field modernized capabilities with timeliness and affordability as a priority. According to an OUSD(R&E) official, TMTRs and the CTA roadmaps complement each other, and both are needed to have the full picture of which technologies are needed for achieving a specific mission. TMTRs are mission-focused—they leverage mission engineering analysis to inform decisions via capabilities and technologies needed for a specific mission. The CTA roadmaps are technology driven—they contain a set of development efforts around a specific technology.

OUSD(R&E) is also collecting data on technology transitions via TTAG. TTAG was formally established in February 2024 to enable DOD to track CTAs and other Department Priority Technology Areas, as well as technology transitions across the research and engineering life cycle.[25] According to its charter, TTAG develops and supports the implementation of policies for advanced data analytics to track technology transitions. A senior OUSD(R&E) official overseeing TTAG stated that developing the process for tracking technology transitions was difficult because technology transition has generally only been defined as integrating technology into a DOD acquisition program. To address this challenge, the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, and the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy jointly signed a memorandum in August 2022 stating that technology transition can occur in multiple ways, to also include fielding a new capability, such as a new air defense system; transferring a technology from DOD into use in industry; or transferring technology from DOD into use at another government agency.[26] As of August 2025, OUSD(R&E) reported that TTAG efforts were ongoing.

Joint Requirements Oversight Council Chief Technical Advisor

The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering currently serves as the Chief Technical Advisor to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC). The JROC is responsible for identifying and assessing joint military capabilities and validating joint military requirements. In this role, the Under Secretary assists in evaluating the technical feasibility of requirements under development and identifies options for expanding or generating new requirements, based on opportunities provided by new or emerging technologies. The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 noted that the Under Secretary should support efforts to include more technical rigor and realism in the development and approval of requirements, so that acquisition programs are not initiated in a manner that leads to technical failures or excessive costs.[27]

In the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022, Congress directed DOD to (1) enter into an agreement with an outside organization to conduct a study of enhancements to the Under Secretary’s role on the JROC, and (2) provide the congressional defense committees a report on the Secretary of Defense’s recommendations that addressed the extent to which adjustments to the role of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering on the JROC were warranted.[28] Further, Congress mandated the results of the study no later than December 31, 2022, and the report on the recommendations no later than March 1, 2023. However, as of August 2025, DOD had not completed the study.[29]

According to an OUSD(R&E) official, for DOD’s Capability Portfolio Management process to be successful, the Under Secretary needs an enhanced role on the JROC. This official noted that OUSD(R&E) and the Joint Staff, for example, have complementary missions—OUSD(R&E) is responsible for bringing technology forward to meet the capability gaps identified by the Joint Staff. This official further noted that, as an advisor, the Under Secretary can provide technical advice on issues before the JROC but lacks the authority to compel the JROC to act on that advice.[30]

OUSD(R&E) Administers Technology-Focused Programs for the Joint Force Through Its Prototyping Efforts

To execute its role in overseeing cross-cutting demonstration, developmental prototyping, and experimentation activities, OUSD(R&E) administers various programs meant to address the technology needs for the joint force. These programs—Defense Innovation Acceleration (DIA); Rapid Prototyping Program (RPP); and Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve (RDER)—received approximately $427.5 million in funding in fiscal year 2023 and $361.4 million in funding in fiscal year 2024. Table 3 provides additional details on funding levels and project transition rates, which OUSD(R&E) defines as a prototype capability that is transferred to a military department program of record. A prototype capability that failed to meet technical objectives or inform a military department program is defined as “No transition.”

Dollars in millions

|

Program name |

Fiscal Year 2023 funding |

Fiscal Year 2023 transition rate |

Fiscal Year 2024 funding |

Fiscal Year 2024 transition rate |

|

Defense Innovation Acceleration (DIA) |

$293.5 |

13 of 15 projects (87%) |

$261.7 |

6 of 7 projects (86%) |

|

Rapid Prototyping Program (RPP) |

$109.2 |

10 of 12 projects (83%) |

$76.2 |

5 of 7 projects (71%) |

|

Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve (RDER) |

$24.8 |

19 of 23 projects (83%) |

$23.5 |

N/A |

|

Total |

$427.5 |

42 of 50 projects (84%) |

$361.4 |

11 of 14 projects (79%) |

Legend: N/A = not applicable

Source: GAO Presentation of Department of Defense data. | GAO‑26‑107664

Note: The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) defines project transition as a prototype capability that is transferred to a military department program of record. “No Transition” is defined as a prototype capability that failed to meet technical objectives or inform a military department program. OUSD(R&E) attributes lower project count for the DIA program in fiscal year 2024 to consolidation of several other prototyping programs in May 2023. Transition data for RDER projects in fiscal year 2024 was not available as those projects—which can last up to 24 months—have yet to transition, according to OUSD(R&E).

Defense Innovation Acceleration Program

DIA was established in 2023 following the cancelation of the Joint Capability Technology Demonstration program and subsequent reorganization of the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Prototyping and Experimentation, which oversees prototyping programs within OUSD(R&E). DIA is intended to streamline and accelerate DOD’s approach to prototyping and develop prototypes that address joint warfighting and combatant command needs, mature engineering technologies, and reduce technical risk. DIA consolidated several existing prototyping efforts into one budget line item. DIA projects are executed in partnership with the military departments, which typically provide at least 50 percent of project funding. DIA projects are 12-to-36-month efforts, which are typically funded between $1 million to $5 million per year. According to the Defense Innovation Acceleration Program Guide, good DIA projects, when successfully executed, deliver “leap-ahead” capability that enable technological surprise.[31]

Rapid Prototyping Program

The RPP was created in 2017 and supports the rapid development of prototypes required in 12-to-24 months to address urgent needs identified by the Joint Staff or combatant commands. RPP projects demonstrate a specific capability that is not addressed by a single military department. According to OUSD(R&E)’s Rapid Prototyping and Experimentation Program Guide, capability delivery is the desired outcome of all RPP projects, whether it is a prototype delivered to a program of record, a capability delivered to the joint warfighter, or a capability delivered as a significant component of a broader mission thread.[32]

Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve Program

The RDER program, which is focused on joint interoperability, was created in 2021. In 2025, DOD proposed to cancel the RDER program. RDER projects were intended to close joint warfighting gaps using iterative cycles of design and validation over 12-to-24-month cycles. The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering intended for RDER to draw on the strengths of iterative feedback loops between warfighters and engineers throughout the testing and experimentation phase.[33] According to the Under Secretary, the ability to quickly adopt emerging technologies is accelerated through rapid prototyping and fast iterations of development between technology developers and the user community. In doing so, capability could be fielded 2 or more years faster by providing multiple venues for joint experimentation and subsequently transitioning new technology into programs of record.

Although project proposals for RDER could be submitted from stakeholders across DOD, OUSD(R&E) officials told us the military departments were largely responsible for submitting proposals. OUSD(R&E) provided funding to the military departments, which then managed the technology development effort. Military department officials expressed concerns with both how OUSD(R&E) selected submitted project proposals and the funding structure of RDER. Navy officials, for example, expressed frustration that OUSD(R&E) selected RDER projects that did not always align with Navy priorities. Further, Army officials stated that they were initially led to believe that the funding for RDER projects was in addition to their RDT&E funding—essentially, “free money” as they described it. However, in fiscal year 2024, officials said OUSD(R&E) made it clear that any funding it provided the military departments for RDER projects would be offset by other cuts to the military departments’ RDT&E funding.

In the President’s Budget submission for fiscal year 2026, released in June 2025, DOD proposed canceling the RDER program. An OUSD(R&E) official stated that the program is no longer a priority for DOD senior leadership. Although no new projects will be initiated because of the program’s cancelation, OUSD(R&E) would continue to fund existing projects to completion. This official also stated that experimentation campaigns remained a priority for DOD; however, it is unknown if DOD will resurrect the RDER program in the future or replace it with something similar.

Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies Program

OUSD(R&E) also manages the Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies (APFIT) program. APFIT was created in fiscal year 2022 and provides procurement funding for innovative projects that have completed development and are ready to transition into operational use. APFIT funds are used to bridge potential funding gaps while projects wait for the PPBE process to catch up. It enables companies to immediately begin building production capacity and delivery of low-rate initial production units. Funding is available to small businesses or nontraditional companies with $500 million or less in defense contracts. The APFIT program, for example, has funded small companies to scale up deliveries of mine detection sensors for uncrewed underwater vehicles and uncrewed surface vehicles.

OUSD(R&E) Faces Challenges Managing and Overseeing Military Department Technology Efforts

OUSD(R&E) faces challenges in managing and overseeing military department technology development efforts. For example, it has yet to ensure that CTA roadmaps consistently provide sufficient information for military departments to invest in technologies for the joint fight. Further, it lacks statutory authority to confirm that the military departments’ technology investments, as expressed in their annual budget submissions, align with OUSD(R&E) priorities.

OUSD(R&E)’s CTA Roadmaps Lack Consistent Information to Guide Military Departments’ Technology Investments

We found that OUSD(R&E) has yet to ensure CTA roadmaps consistently provide sufficient information for military departments to invest in technologies for the joint fight because OUSD(R&E) has not developed formal guidance for those roadmaps.

As previously stated, OUSD(R&E) is responsible for identifying critical technology areas and designating officials to develop CTA roadmaps and submitting a report to the congressional defense committees on the progress being made in these areas annually. These roadmaps serve as a tool both to communicate investment priorities to the military departments and assess whether their proposed budgets will support those priorities. Generally, the roadmaps contain near-, mid-, and far-term objectives for DOD to achieve technological superiority in each area. There are no statutory requirements for the content of the roadmaps. The senior official responsible for each CTA is required to conduct annual assessments to support the roadmaps on the following areas: workforce, infrastructure, and the industrial base.[34]

We found that the extent to which the 14 CTA roadmaps contain information about workforce, infrastructure, and industrial base issues varied widely. For example:

· Workforce. Three of the 14 roadmaps contain information about workforce issues in detail. For example, the Quantum Science roadmap describes the current size and composition of the workforce in this area, including how it is distributed among the military departments and between government and contractors. The roadmap states that the size of the workforce is small compared with the number of quantum science efforts in DOD.

· Infrastructure. Eight of the 14 roadmaps contain information about infrastructure in detail. For example, the Microelectronics roadmap specifies near-, mid-, and far-term goals for developing infrastructure. The roadmap describes the Microelectronics Commons, a network of innovation facilities intended to make prototypes of research concepts ready for adoption in acquisition programs and the commercial sector. The roadmap also sets goals to develop the Commons over the next 10 years to establish innovation hubs to foster a pipeline of talent and accelerate prototyping of artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and 5G technology capabilities, among others.

· Industrial base. Five of the 14 roadmaps contain information about industrial base issues in detail. For example, the FutureG roadmap describes the industrial base for wireless technology as underdeveloped in the United States. It states that because of greater investment by China, as well as commercial consolidation, DOD should invest in open networks that can be supported by multiple vendors.

Figure 5 below shows the extent to which the CTA roadmaps contain information about workforce, infrastructure, and industrial base issues.

Figure 5: Variation Across Critical Technology Area Roadmaps’ Information Regarding Workforce, Infrastructure, and Industrial Base

Note: Emerging opportunities are considered technology areas of early-stage development; effective adoption technology areas are those technologies where there is vibrant existing commercial activity; and defense-specific technologies are areas where the Department of Defense must take the lead in the research and development to ensure leap-ahead capabilities development. The Office of the Under Secretary for Research and Engineering is responsible for designating senior officials to develop research and technology development roadmaps for each critical technology area. Although there are no statutory requirements for the content of the roadmaps, the senior official responsible for each Critical Technology Area is required to conduct annual assessments to support the roadmaps on the following areas: workforce, infrastructure, and the industrial base.

The roadmaps also vary in the level of detail about the CTAs themselves. For example, the Quantum Science roadmap describes potential applications of quantum science in detail. Conversely, the Human-Machine Interfaces roadmap lays out a basic introduction to the concept of that technology and brief descriptions of its potential applications. Finally, Principal Directors with whom we met described different processes, schedules, and levels of stakeholder involvement for developing their roadmaps.[35] For example, the Integrated Network Systems-of-Systems Principal Director engaged with industry as part of Integrated Network Systems-of- Systems CTA roadmap development. The Directed Energy Principal Director engaged with the Hypersonics Principal Director to address issues related to defensive capabilities and discuss how to incorporate those into the Directed Energy roadmap.

OUSD(R&E) officials told us the roadmaps vary, in part, because OUSD(R&E), through the ASD(CT), has not developed formal guidance for the CTA Principal Directors—the senior officials designated to coordinate research and engineering activities and develop research and technology development roadmaps for each CTA—to use in developing the roadmaps. ASD(CT) officials told us they are planning to make the roadmaps more standardized in the future. Currently, officials said Principal Directors are responsible for using their subject matter expertise to determine which stakeholders to involve and whether the roadmap is complete.

DOD Directive 5137.02 states that OUSD(R&E) is responsible for identifying and defining DOD’s modernization priorities and establishing timelines for delivery of desired future capabilities for those priorities.[36] In addition, the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 requires the senior officials, in this case the Principal Directors, responsible for each CTA:

· to continuously update the CTA roadmaps to ensure the effective and efficient development of new capabilities and operational use of appropriate technologies; and

· to advise the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering on efforts that are duplicative, not coordinated appropriately between DOD organizations, or not aligned to the Department’s mission and capabilities.[37]

By not issuing guidance for roadmap development, OUSD(R&E) lacks reasonable assurances that the military departments are focusing on and investing in technologies considered critical to meeting the NDS and maintaining technological superiority against its adversaries. Specifically, by not identifying stakeholders, including those from the military departments, to involve in developing the CTA roadmaps, OUSD(R&E) risks having incomplete information about the technology development efforts being pursued by the military departments. Further, by not identifying the content that the CTA roadmaps should contain, OUSD(R&E) risks the roadmaps not being useful to decision-makers to ensure military department efforts align to OUSD(R&E) priorities.

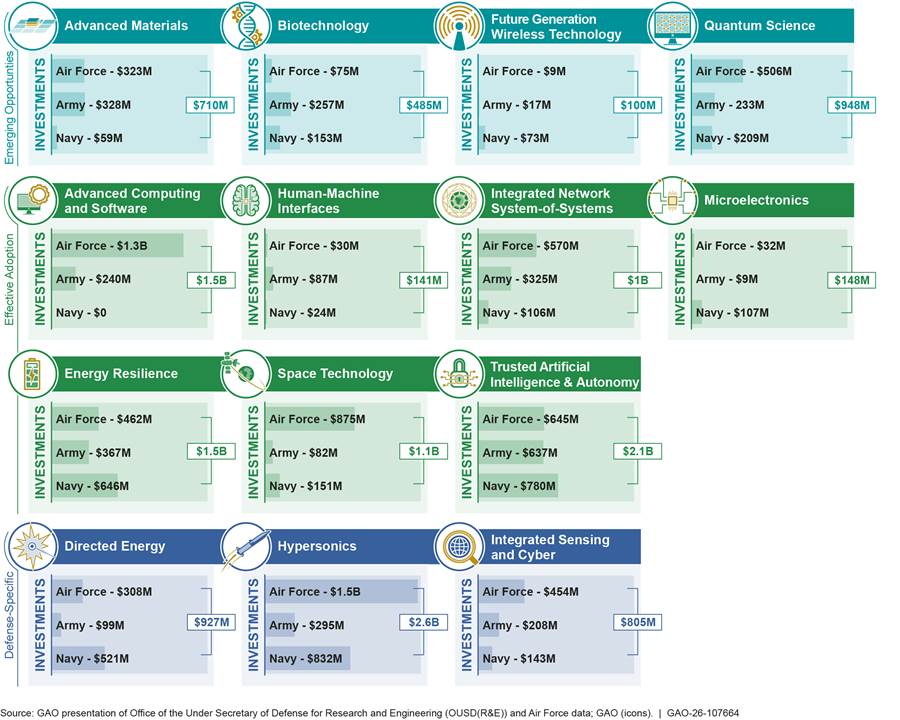

OUSD(R&E) officials expressed concern that the military departments are more focused on service-specific priorities rather than those benefiting the joint force, such as directed energy. Yet data provided by OUSD(R&E) show the military departments are investing in the CTAs. However, the level of investment in each of the CTAs varies (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: Military Department S&T Investments for Fiscal Year 2025 in OUSD(R&E) Critical Technology Areas

Dollars in millions

Note: The Department of Defense (DOD) funds technology and product development activities under its research, development, test and evaluation budget, which DOD groups into seven budget activity categories. The first three budget activity categories generally represent science and technology activities to advance research and develop technology. Military department subtotals in each CTA may not sum to the total due to rounding.

Military department officials stated they provide data to OUSD(R&E) on the amount of money each are investing by CTA. However, OUSD(R&E) officials acknowledged they have not provided guidance for roadmap development to the military departments. For example, this would include not identifying the level of military department investments that OUSD(R&E) would consider necessary to ensure alignment to the maximum extent practicable with each CTA.

DOD Directive 5137.02 states that OUSD(R&E) is responsible for developing department-wide roadmaps for research and engineering investments in priority areas.[38] Further, the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 requires the senior officials responsible for each CTA:

· to advise the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering on whether military department budgets are consistent with the roadmaps; and

· to assess military department budgets for risks to achieving the research and technology development goals of the National Defense Strategy.[39]

Without directing the level of investment needed in each CTA, OUSD(R&E) lacks reasonable assurance that sufficient investments are being made towards progress in any given CTA to ensure timely delivery of future capabilities. Further, OUSD(R&E) risks insufficient investments being made in the technologies it has identified as being critical to countering the threats of our adversaries. As noted earlier in this report, OUSD(R&E) wants to align annual updates to the CTA roadmaps with the release of the President’s Budget submission. In doing so, decision-makers could have better insight into investments in the CTAs.

OUSD(R&E) Relies on Military Departments to Provide Information on Technology Efforts

To fulfill its statutory requirements to manage and oversee DOD’s technology development efforts, OUSD(R&E) relies on information provided by the military departments. This information includes technology development efforts as part of the CTA roadmap development process, discussed above, as well as information to support TMTRs and the TTAG effort. DOD Directive 5137.02 states that the heads of DOD Components—which would include the military departments—coordinate with OUSD(R&E) on matters under the DOD Component heads’ purview related to the responsibilities, functions, and authorities assigned to OUSD(R&E).[40]

However, officials from OUSD(R&E) stated that they do not always receive timely, accurate, and complete information from the military departments, and that the military departments can be slow to respond to requests for data. For example, an OUSD(R&E) official stated they estimate that the data collection efforts they conduct only capture about 70 to 80 percent of the ongoing technology development projects within the military departments.

OUSD(R&E) officials told us there are multiple reasons why the military departments are slow to respond or do not provide data to OUSD(R&E). For example, they said that:

· There are concerns about how the data will be used; a lack of understanding or awareness regarding the value of providing the data; and unfamiliarity with the data collection effort.

· There are challenges in getting the military departments to tag data in a way that was useful to assess its reliability.[41]

· The military departments do not appear to have complete visibility into their own technology portfolios.

Further, a senior OUSD(R&E) official also stated that the combatant commands are also increasingly investing in their own science and technology efforts, which the military departments and OUSD(R&E) would not necessarily have visibility into.

To overcome issues with incomplete or inaccurate data, some CTA Principal Directors told us that they rely on their own informal professional networks and outreach efforts to obtain information as they develop their CTA roadmaps. This information supplements what they receive from the military departments. While the use of informal networks can be helpful to fill gaps, depending on such networks can be unreliable—as the ability to obtain useful data depends on who is in a Principal Director’s network at any given time.

An OUSD(R&E) official shared that OUSD(R&E) has also recently initiated a pilot program, using an existing DOD advanced analytics platform to extract investment data by CTA from each of the military departments RDT&E budget submissions. This official is involved with the pilot program and stated that, over time, the goal is to position OUSD(R&E) to be able to collect and analyze this data itself, rather than relying on the military departments to provide the data. However, this official described the pilot program as being in its early stages, and one challenge that needs to be resolved is how best to categorize technology development efforts that cross two or more CTAs. This official was able to provide initial data for the military departments’ fiscal year 2025 investments.

Military department officials stated they respond to data collection efforts from OUSD(R&E). While Navy officials acknowledged that the volume of data requests makes it difficult to provide timely data back to OUSD(R&E), Air Force officials do not believe the issue is a lack of responsiveness from the military departments. Instead, Air Force officials said OUSD(R&E) receives so much data from the military departments that it lacks the resources to properly analyze what the military departments are doing. A USD(Comptroller) official expressed a similar opinion, stating that, with a budget as large as DOD’s, organizations need to prioritize where to focus their time and resources on where the military departments want to make investments.

Statute Does Not Provide OUSD(R&E) with Authority to Provide Input on Military Departments’ Technology Investments

OUSD(R&E) is limited in its ability to influence military department RDT&E budgets to ensure they align with department-wide priorities, despite OUSD(R&E)’s statutory authority to supervise DOD’s technology development efforts.[42] There have been several instances, OUSD(R&E) officials stated, of one or more combatant commands requesting a technology that was ready for transition but was not included in a military department budget, preventing available capabilities from reaching the joint force. For example, OUSD(R&E) officials cited the Joint Fires Network as an effort that has lacked investment by the military departments. Specifically, it was unclear which military department would take the lead in developing the Joint Fires Network prototype, requiring OUSD(R&E) to spearhead the effort. OUSD(R&E) officials commented that the process for developing the prototype would have been streamlined if they had the authority to direct the transition.[43]

In addition, OUSD(R&E) officials stated that they lack the ability to prevent unnecessary duplication. For example, OUSD(R&E) had limited means to consolidate the military departments’ investments in Alternative and Assured Positioning, Navigation, and Timing. OUSD(R&E) officials told us that, despite congressional interest in consolidating those efforts, OUSD(R&E) lacked the authority to direct military departments’ technology investments. Officials stated that, in these instances, they must rely on the power of persuasion.

The Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering participates in the Deputy’s Management Action Group review of military department RDT&E budgets.[44] However, OUSD(R&E) officials stated they do not receive detailed and timely budget documentation from the military departments because the military departments are not required to do so. More specifically, OUSD(R&E) officials said that they only receive top-line budget information and generally have less than 2 weeks to review the military departments’ RDT&E budget submissions. OUSD(R&E) officials told us this limited time is not sufficient to review and assess the military departments’ technology investments.

OUSD(R&E) is limited in its ability to influence military department technology investments because it does not have statutory authority to review and provide meaningful input to the military departments’ investments. OUSD(R&E) officials stated that their authority is insufficient to execute the office’s responsibility to oversee DOD’s technology development efforts.

Congress has recognized the need for certain DOD organizations to have a greater role in reviewing military department budget submissions, such as the military departments’ test and evaluation, cybersecurity, and information technology budgets. As a result, Congress granted budget certification authority to the Test Resource Management Center, the Principal Cyber Advisors, and the Chief Information Officer to enable these organizations to have sufficient authority to review and assess military department budget submissions.

Budget certification authority generally enables a DOD organization to certify that a military department’s proposed budget is adequate and provide that certification to an appropriate official, such as the Secretary of Defense as part of the annual budgeting process. The military departments are required to submit their proposed budget for certain activities to the corresponding certifier—i.e., the Test Resource Management Center—early in the budget process; for example, by January 31 of each year prior to release of the President’s Budget submission. Then the certifier issues a report providing their comments on the proposed budget and certification as to whether the budget is adequate. If the certifier does not certify the proposed budget as adequate, the military departments or the Secretary of Defense must report to Congress on what actions they will take to address those concerns.[45]

Military department officials expressed reservations about OUSD(R&E) having budget certification authority like that of other DOD organizations. For example, Army officials stated that it would introduce additional layers of oversight that could potentially delay the budget approval process. Further, they noted that their RDT&E budget is already subject to multiple reviews with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, including forums where OUSD(R&E) can provide input. Navy officials stated that budget certification authority would likely result in a significant increase in workload of limited value, due to additional data calls and reviews. They further stated that development of the budget is a rigorous 11-month process, consisting of multiple reviews by senior Navy leadership.

OUSD(R&E) is required in statute to supervise research and engineering efforts across the Department.[46] OUSD(R&E) officials stated that budget certification authority would be the least intrusive option that allows them sufficient time and authority to assess how the military departments’ technology investments align with DOD’s science and technology strategy and enable OUSD(R&E) to accomplish its mission. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that federal entities should have the level of authority they need to fulfill their responsibilities.[47]

Without proper authority and time to review and assess RDT&E budget submissions as part of the budget process, DOD risks the military departments not investing in technologies that warfighters need both for the current and future fight, especially to support the joint force. In addition, having a complete understanding of the full breadth of technology efforts undertaken by the military departments will enable OUSD(R&E) to provide effective management and oversight of these efforts as well as enable it to provide information to Congress as part of the budgeting process.

Conclusions

DOD strives to outpace technologically advanced adversaries such as China and Russia. Yet, OUSD(R&E) struggles to manage and oversee the department’s innovative technology efforts and investments in them. DOD can accelerate these efforts if it acts to correct these issues.

For example, several areas of the military departments’ S&T strategies do not align with DOD’s overarching S&T strategy. Additionally, OUSD(R&E) has yet to ensure that Critical Technology Area roadmaps consistently provide sufficient information for military departments to invest in technologies for the joint fight. Consequently, the effect of these issues is that the military departments risk pursuing technologies that do not match the objectives of the National Defense Strategy.

Further, OUSD(R&E) is also hamstrung by the existing budget process and lack of authority to certify military department budgets. As a result, OUSD(R&E)’s ability to influence the technologies in which the military departments ultimately invest is limited. Having such authority would better position DOD to ensure military departments’ technology efforts align with department-wide priorities. Without addressing these challenges, however, OUSD(R&E) risks being unable to effectively execute its responsibilities to manage, oversee, and improve technology development efforts across DOD.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider providing OUSD(R&E) with budget certification authority for research, development, test and evaluation activities. This would require (1) the secretary of each military department and the head of each defense agency to transmit their department’s or agency’s proposed budget for research, development, test and evaluation activities for a fiscal year and for the period covered by a future-years defense program to the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering by January 31 of the year preceding the proposed budget’s fiscal year; (2) the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering to review each proposed budget and determine whether it is adequate; and (3) an appropriate DOD official to report to the congressional defense committees on each proposed budget that the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering determines to not be adequate. (Matter for Consideration 1)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should direct the Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy to each develop and issue a science and technology strategy that aligns with the National Defense Science and Technology Strategy to the maximum extent practicable, and to update their strategies as needed to ensure continued alignment. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering issues guidance for the development of the Critical Technology Area roadmaps. This guidance should identify stakeholders—including from the military departments—to involve when the roadmaps are developed, as well as identify the content to include in the roadmaps. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should direct the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering to provide annual guidance to the Secretaries of the Air Force, Army, and Navy on the amount of military department investment that OUSD(R&E) considers necessary to ensure alignment to the maximum extent practicable with each Critical Technology Area roadmap. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment in September 2025. We received written comments in January 2026, which are reproduced in appendix I and summarized below. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In its written comments, DOD concurred with our recommendations.

In addition, DOD provided comments on the Matter for Congressional Consideration for Congress to provide OUSD(R&E) with budget certification authority. In its written comments, DOD stated that the Departments of Army, Air Force, and Navy disagreed, noting that such authority would lead to delays, restricted autonomy, and increased workload.

However, as we state in the report, OUSD(R&E) is limited in its ability to influence military department RDT&E budgets to ensure they align with department-wide priorities—a key role it is intended to play. Additionally, Congress has recognized the need for certain DOD organizations to have a greater role in reviewing military department budget submissions. Budget certification authority is a mechanism for OUSD(R&E) to have a complete understanding of the full breadth of technology efforts undertaken by the military departments. Therefore, we stand by our matter for Congressional consideration that providing OUSD(R&E) such authority would enhance management and oversight of these efforts and provide information to Congress as part of the budgeting process.