GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION

Information on Initial Distributions of New Medicare-Funded Physician Residency Positions

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Leslie V. Gordon at GordonLV@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

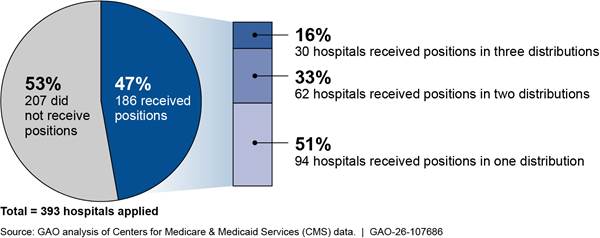

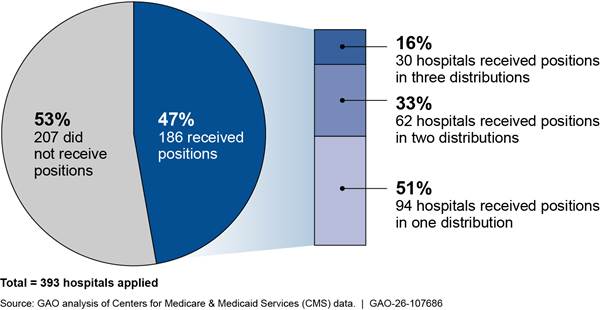

Medicare payments to hospitals to support graduate medical education (GME) for physicians are capped by the number of residents. As of September 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allocated 600 of the 1,000 new Medicare-funded positions to hospitals from three annual distributions. To date, about half of the 393 hospitals that applied received new positions.

Note: Figure represents the 393 hospitals that applied for or received residency positions in at least one of the first three annual distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021.

Hospitals that received positions in the first three distributions were similar to hospitals that applied for and did not receive positions. For example, nearly all were in geographically urban areas and most applied to expand existing residency programs that had been approved to train residents for over 10 years. In addition, about half of hospitals that received positions applied to train more residents in primary care specialties. Further, hospitals that received positions were generally larger in terms of their resident cap and total Medicare GME payments in 2023, compared to other hospitals that applied but did not receive positions.

Selected stakeholders identified benefits of these additional positions, such as expanded training opportunities and increased physician services in their communities. For example, one rural hospital expanded its family medicine program which allowed it to implement a resident mentoring approach; another hospital expanded outpatient training, enabling residents to follow patients in later care, according to representatives.

Selected stakeholders also described how CMS’s decision to distribute positions by prioritizing applications with the highest health care provider shortages may have disadvantaged some hospitals. In addition, stakeholders said funding challenges, such as up-front costs of new residency programs, also affected hospitals’ decisions to apply for new positions.

Why GAO Did This Study

Communities across the U.S., and rural areas in particular, face a growing risk of having too few physicians to meet health care needs. In 2023, Medicare paid about $22 billion to support GME residency positions at over 1,400 hospitals.

Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 requires CMS to distribute 1,000 new Medicare-funded GME residency positions to qualifying hospitals through permanent increases in their resident caps. The law requires CMS to distribute these positions in at least five annual distributions, with the first of these positions being available for use in 2023. The new positions are expected to cost about $1.8 billion over the first 9 years.

The law also includes a provision for GAO to study the implementation of this process. This report describes the number of hospitals that applied for and received additional positions, their characteristics, and benefits and challenges identified by selected stakeholders related to the distribution of these additional positions.

GAO analyzed hospital application data submitted to CMS for the first three annual distributions from 2023 through 2025; Medicare Cost Reports; and residency program data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

GAO also reviewed CMS documentation and public comments on CMS rulemaking and interviewed officials from CMS and the Health Resources and Services Administration. GAO also interviewed 14 stakeholders, including those representing hospitals and physicians, and seven selected hospitals that received new positions under Section 126.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CAA |

Consolidated Appropriations Act |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

DGME |

Direct Graduate Medical Education |

|

FTE |

full-time equivalent |

|

GME |

graduate medical education |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HPSA |

Health Professional Shortage Area |

|

HRSA |

Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

IME |

Indirect Medical Education |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 22, 2025

Congressional Committees

Communities across the United States face a growing risk of having too few physicians to meet their health care needs, with an estimated shortage of about 16 percent (or about 187,000 physicians) by 2037, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).[1] Rural areas are projected to face a physician shortage of nearly 60 percent compared to a 10 percent shortage in urban areas.[2]

While many factors can affect the supply and distribution of physicians, the location where physicians complete their graduate medical education (GME) training—which is required before they can practice medicine independently—is a significant determinant. Research has shown that physicians in training, commonly referred to as medical residents, often go on to practice in the same area where they completed their GME training.[3] However, medical residents are unevenly distributed across the country, with almost all training occurring in hospitals in urban centers, with the highest concentration in the Northeast, according to our 2017 report.[4] As of the 2023-2024 academic year, there were about 163,000 medical residents training in the United States.[5]

The federal government provides financial support for GME training through a number of agencies and programs with the majority of this funding coming from Medicare payments administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), according to an analysis of 2015 data.[6] In 2023, Medicare paid about $22 billion to support GME residency positions at over 1,400 hospitals.[7] Medicare GME payments are intended to partially offset the costs hospitals incur for training residents. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 established a hospital-specific limit on the number of medical resident positions that Medicare will fund—referred to as a hospital’s resident cap—based on the number of residents the hospital was training in 1996.[8] Once set, a hospital’s Medicare resident caps are generally permanent; however, hospitals may choose to train more residents above these caps without additional payments from Medicare. They can also train fewer residents than are eligible for Medicare funding. In May 2021, we reported that 70 percent of hospitals with residency programs trained more residents than their Medicare resident caps in 2018.[9]

Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021 requires CMS to distribute 1,000 additional GME residency positions to qualifying hospitals through permanent increases to their resident caps over at least 5 years, beginning in fiscal year 2023.[10] Hospitals are required to submit applications and meet certain criteria to receive positions. CMS estimated that funding these additional positions will cost $1.8 billion over the first 9 years of the program.[11] As of September 2025, CMS had completed the first three annual distributions.

The CAA, 2021 also includes a provision for us to study the implementation of the distribution of the additional positions under Section 126.[12] In this report, we describe

1. the number of hospitals that applied for and received Section 126 residency positions and the characteristics of these hospitals,

2. benefits of the Section 126 residency positions identified by selected stakeholders, and

3. challenges identified by selected stakeholders related to the application for and the distribution of these additional positions.

For our three objectives, we reviewed relevant statutes, regulations, and guidance, as well as agency documentation of the distribution process used in the first three annual distributions from 2023 through 2025, which were the annual distributions completed at the time of our review. We also interviewed CMS officials responsible for distributing these positions.

To identify the number of hospitals that applied for and received additional positions in the first three annual distributions, we reviewed hospital application data that CMS collected for these distributions. To compare the hospitals that applied for Section 126 residency positions to hospitals that did not apply, we estimated the number of hospitals that may have been eligible for Section 126 distributions. We used 2023 Medicare Cost Reports to identify hospitals that met one or more of the following criteria: Section 126 applicant, teaching hospital, or received a GME payment.

To describe applicant hospitals’ characteristics, such as location (e.g., geographically urban or rural area), GME payments, and residency program specialty, we used 2023 Medicare Cost Reports and other Medicare files, data on residency programs for the 2023-2024 academic year from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and information from HRSA’s Federal Office of Rural Health Policy as of October 2024. We also examined CMS’s application data from the first three distributions to describe additional information for applicant hospitals, such as the reported Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) type, identification number, and score; and the reported eligibility categories to qualify for Section 126.

To assess the reliability of the data we analyzed—that is, data obtained from CMS, HRSA, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education—we obtained and reviewed relevant information and interviewed knowledgeable agency officials about the accuracy of the data. For these data sources, we performed checks to identify and take steps to adjust for missing or incorrect data. Based on these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. (See app. I for further details on our scope and methodology.)

To describe the benefits and challenges identified by selected stakeholders related to residency positions distributed through Section 126, we interviewed or received comments from 14 stakeholders including representatives of hospitals, physicians, the accrediting body for GME programs, and HHS advisory councils. We selected these stakeholders to gather a broad range of perspectives. In addition, we analyzed Section 126 hospital application data and reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of public comments that discussed Section 126 and were part of CMS’s Inpatient Prospective Payment System rulemaking for fiscal years 2022 and 2025. We also interviewed representatives of a nongeneralizable sample of seven hospitals that received Section 126 residency positions in the first two distributions. At the time of our selection, CMS had completed two annual distributions. We selected hospitals based on their geographic designations, census regions, medical specialties specified in their applications, and whether they applied for a new or existing residency program. The information we obtained from these stakeholders and hospitals is not generalizable to the experiences or views of other entities.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

GME Training

After medical school, physicians must complete GME training in a particular medical specialty before they can practice medicine independently. Hospitals offer medical residency programs where recent medical school graduates gain experience caring for patients under the supervision of experienced physicians and program faculty. Hospitals may participate in several residency programs, each of which may focus on a different specialty or emphasis, such as rural care. Hospitals may also partner with participating sites—such as outpatient clinics—and send residents to train at these locations on a rotating basis to help meet their educational needs.

Residents complete initial GME training in medical specialties, such as family medicine, general surgery, or internal medicine. Depending on the specialty, this training lasts for at least 3 to 5 years. Afterwards, some residents choose to complete additional GME training through a subspecialty fellowship program. For example, a physician who completed a 3-year residency in a primary care specialty such as internal medicine may go on to subspecialize in cardiovascular disease to become a cardiologist. These subspecialty GME programs typically range from 1 to 3 years of additional training.

Typically, only hospitals training residents in allopathic and osteopathic medical residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education are eligible to receive Medicare GME payments for training residents.[13] According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, it assesses and monitors compliance with requirements that vary by specialty, but include sufficient

· ratio of faculty to residents;

· patient volume;

· availability of specific clinical experiences, such as training in other specialties;

· leadership from an experienced GME program director; and

· resources to support resident education.

Medicare GME Funding

Medicare partially funds GME training through two types of payments, which are designed to offset Medicare’s share of hospitals’ costs associated with GME training: Direct Graduate Medical Education (DGME) payments and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. DGME payments offset the direct costs of training residents, such as stipends. IME payments offset costs that result from less efficient care provided by residents, such as ordering additional tests as part of their training. Both payments are calculated using formulas based in statute, which take many factors into account, such as Medicare patient volume, number of residents a hospital trains, or ratio of residents to the number of hospital beds.[14] Hospitals do not receive Medicare GME payments until they begin training residents.[15] In addition, they are generally only able to obtain payment for the time residents train in their facilities.[16]

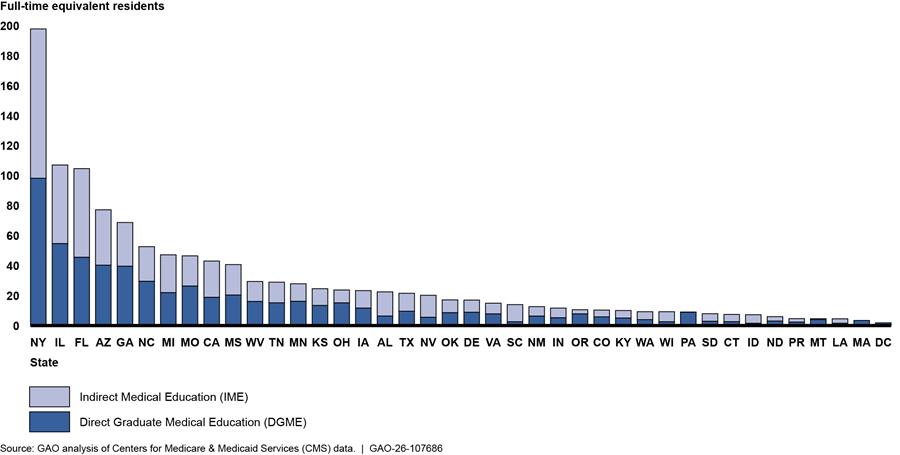

Medicare payments to hospitals are limited by hospital-specific caps set by CMS on the number of DGME and the number of IME full-time equivalent (FTE) medical residents. These Medicare resident caps are generally permanent.[17] However, hospitals may choose to train more residents than are supported by caps. DGME and IME caps are calculated separately, so a hospital may be training over its cap for one payment type and under its cap for the other.[18] In 2023, Medicare funded about 106,460 FTE medical residents by DGME payments and 111,790 FTE medical residents by IME payments.

Hospitals training over their caps may supplement their Medicare GME funding from the following sources to help cover the additional costs:

· Other federal or state programs. Other HHS agencies, such as HRSA, as well as states also provide GME funding through programs, such as the Medicaid program or grant programs.[19] Other sources of federal funding include the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense.

· Clinical revenue. Hospitals may use revenue earned from clinical services to support resident training.

· Philanthropic donations. Some hospitals may receive philanthropic donations to support resident training.

|

Health Resources and Services Administration’s Rural Grants The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provides funding to support the development of new residency programs in rural areas through its Rural Residency Planning and Development program. This program, which began in fiscal year 2019, provides funds to support start-up costs of new rural residency programs and includes a technical assistance center that helps rural hospitals with this process. HRSA has awarded approximately $77 million through 103 grants to develop new residency programs. As of August 2025, 62 programs had achieved accreditation, and the others were working to plan their residency programs and meet accreditation criteria. Source: HRSA. ꟾ GAO‑26‑107686 |

Process for Distributing Section 126 Residency Positions

CMS established a process to distribute Section 126 residency positions through five annual distributions, beginning in 2023. CMS did so based on the requirements outlined in law and in consideration of public comments it received.[20] Under the CAA, 2021 CMS must distribute up to 200 additional GME residency positions per year to hospitals through permanent increases to their resident caps until the 1,000 available positions are allocated. As Medicare GME is financed through two payment types—DGME and IME—to implement this provision and distribute up to 200 GME residency positions per year, CMS allocated 200 FTEs per year for the purpose of increasing the cap on the number of positions Medicare will fund for DGME payments and another 200 FTEs per year for the purpose of increasing the cap on the number of positions Medicare will fund for IME payments. Hospitals receiving these additional FTEs must use them to support an increase in the number of medical residents they train.[21]

Timeline

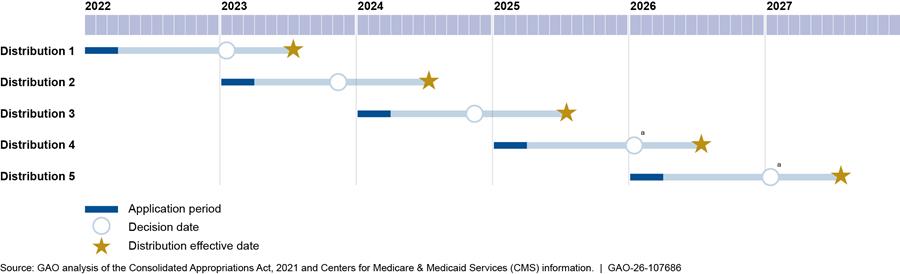

The CAA, 2021 outlines a timeline for the distribution of Section 126 residency positions. To receive positions, hospitals are required to submit an application to CMS. As of November 2025, CMS had distributed positions in three of the five annual distributions and planned to distribute the remaining positions in two more annual distributions. These increases will take effect in 2026 and 2027, respectively. (See fig. 1.)

aSection 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 requires CMS to announce its distribution decisions by January 31 of the year in which the increases take effect.

Hospital Eligibility

Section 126 also requires hospitals to meet at least one of four qualifying categories to receive the positions. Further, it requires CMS to distribute at least 10 percent of the 1,000 total GME residency positions (i.e., 100 GME residency positions or, as implemented, 100 FTEs for DGME and 100 FTEs for IME for the purpose of increasing both DGME and IME caps) to hospitals in each category. The four qualifying categories are as follows:

· Qualifying category one (rural or rural reclassified). In a rural area or treated as being rural.[22]

· Qualifying category two (over cap). Trains more residents than Medicare reimburses—that is, the hospital is training above its established DGME or IME caps.[23]

· Qualifying category three (new medical school or campus). In a state or U.S. territory with a new medical school or branch campus established on or after January 1, 2000.[24]

· Qualifying category four (geographic HPSA). Serves areas designated as a geographic HPSA—areas experiencing a shortage of health care providers. (See text box).

|

Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) Designations HPSAs are used to designate areas experiencing a shortage of providers, such as primary or mental health care providers. An area may have multiple designated HPSAs, such as geographic and population HPSAs. Geographic HPSAs indicate a shortage of providers for an entire group of people within a defined geographic area. In contrast, population HPSAs indicate a shortage of providers for a specific group of people within a defined geographic area, such as low-income populations. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) manages the HPSA designation process. The agency reviews shortage designation applications submitted by state primary care offices and calculates HPSA scores. HPSA scores for primary or mental health care disciplines range from 0-25, and a higher HPSA score indicates a greater shortage. HPSA scores are publicly available and are reviewed annually. HPSA scores are based on multiple factors, but all include: · population-to-provider ratios; · percentage of population below 100 percent of the federal poverty level; and · travel time or distance to receive care outside of the HPSA. An area may have multiple designated HPSAs for different disciplines, but only one HPSA of each discipline may be designated in an area. For example, a HPSA can have one score representing a shortage of primary care providers and another score representing a shortage of mental health providers. HRSA uses HPSA scores to assign National Health Service Corps providers to the areas with greatest need. |

Source: HRSA. ꟾ GAO‑26‑107686

Hospital Applications

As a part of the applications, CMS collects the following information from hospitals: relevant qualifying categories; number and type of residency positions requested; residency program specialty; whether the hospital applied to expand a program already training residents or beginning a new residency program; and information on the program’s accreditation status.[25] To prioritize its distribution of Section 126 residency positions, and separate from meeting a qualifying category, CMS also asks hospitals to indicate that at least 50 percent of residents’ training time over the duration of the residency program would occur at facilities in a geographic or population HPSA as well as any corresponding HPSA identification numbers and scores. For the purpose of prioritizing applications, it is optional for hospitals to provide HPSA information to CMS.

In each annual distribution, hospitals are permitted to apply once, for one specialty or subspecialty program, and can request up to a total of five GME residency positions—that is, five FTEs for DGME and five FTEs for IME—because the CAA, 2021 limits the number of positions a hospital can receive to 25 GME residency positions over the course of all distributions.[26] Hospitals also have to meet other requirements. For example, to qualify as serving a geographic HPSA (qualifying category four), CMS requires hospitals to attest that at least 50 percent of residents’ training time over the duration of the residency program will occur at facilities in the HPSA. Additionally, hospitals have to attest that they will be able to fill any Section 126 residency positions they receive within 5 years. The CAA, 2021 stipulates that CMS should consider the demonstrated likelihood of the hospital filling the positions within 5 years of the date of the increase as part of its distribution process. (See app. II for additional Section 126 requirements, and how CMS implemented them.)

Application Prioritization

To distribute the Section 126 residency positions, CMS decided to prioritize hospital applications with the highest geographic or population HPSA scores, because a higher score indicates a greater shortage of providers. CMS selected this prioritization approach to more fully address health inequities for underserved populations and because the agency anticipated receiving applications for more residency positions than it could distribute, according to agency officials. In its fiscal year 2022 final rule, CMS stated that HPSA scores were publicly available, regularly updated, and widely used.[27]

According to CMS, it reviews qualifying hospitals’ applications in descending order of HPSA score, starting with those that submit the highest HPSA scores. For the first three annual distributions, the lowest scores for hospitals receiving positions ranged from 11 to 15, out of a maximum possible HPSA score of 25.[28] In their review, CMS officials told us they verify certain information submitted by the hospital, such as the hospital’s eligibility in at least one of the four Section 126 categories, and review required attestations. Once the agency has distributed the total number of positions allowed for the year, it does not further review the remaining applications, according to agency officials.

CMS also reviews the number of positions that a hospital requests and, under certain circumstances, distributes fewer positions to the hospital. As CMS approaches the annual distribution’s total allotment of 200 GME residency positions—that is, 200 FTEs for DGME and 200 FTEs for IME—the agency takes other steps to prioritize certain hospitals. Specifically, if multiple hospital applications have the same HPSA score, but there are not enough positions remaining for each hospital to receive the total requested, CMS further prioritizes distributions to hospitals with fewer than 250 beds. If the number of positions requested by these hospitals is still greater than the amount remaining, CMS reduces the number of positions it distributes to each hospital in proportion to the number of positions requested.[29]

Almost Half of Applicant Hospitals Received Positions; Applicant and Recipient Hospitals Were Similar

Almost half of the hospitals that applied for Section 126 residency positions in the first three annual distributions (2023 through 2025) received positions in at least one distribution. Hospitals that received positions were similar to hospitals that applied and did not receive positions: the majority of hospitals receiving positions were urban and most residency programs were accredited for 10 years or more.

Overall Distribution of Section 126 Residency Positions

Almost half (186) of the 393 hospitals that applied for Section 126 residency positions received them in at least one of the first three annual distributions, according to our analysis of CMS data.[30] Of the hospitals that received positions, 92 hospitals (49 percent) received positions in two or more distributions. (See fig. 2.) As of the third distribution, CMS had allocated 600 of the 1000 GME residency positions available through Section 126—that is, 600 FTEs for DGME and 600 FTEs for IME—to these 186 hospitals.

Note: Figure represents the 393 hospitals that applied for or received residency positions in at least one of the first three annual distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021.

In the first three distributions, hospitals submitted a total of 726 applications for additional positions.[31] (See app. III, table 3.) On average, hospitals received fewer than two FTEs for DGME and for IME per annual distribution.[32]

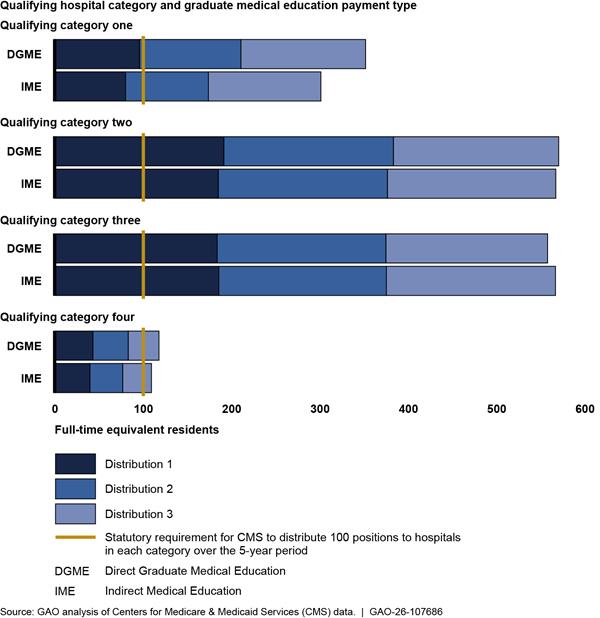

As of the third distribution, CMS reported it had allocated a total of 100 GME residency positions through Section 126—100 FTEs for DGME and 100 FTEs for IME—in each of the four qualifying categories, the minimum amount per category as required by statute across all distributions.[33] (See fig. 3.)

In the first three distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 CMS allocated a total of 600 residency positions—that is, 600 full-time equivalents (FTE) for DGME and 600 FTEs for IME.

Notes: Qualifying category one refers to hospitals in a geographically rural area or treated as rural. Qualifying category two refers to hospitals training more residents than Medicare reimburses—that is, the hospital is training above its established DGME or IME caps. Qualifying category three refers to hospitals in a state or U.S. territory with a new medical school or branch campus established on or after January 1, 2000. Qualifying category four refers to hospitals serving areas designated as a geographic health provider shortage area (HPSA). To determine if the minimum allocation per qualifying category (100 GME residency positions) was achieved, CMS counted a hospital’s FTE allocation in each qualifying category that it met and for both payment types (i.e., DGME and IME). Thus, the FTE counts in this figure are not mutually exclusive. CMS calculated the number of FTEs it allocated for qualifying category four using HPSAs published in November in the year before it distributed the positions.

Hospitals in most states applied for and received Section 126 residency positions. Hospitals in New York, Illinois, and Florida received the most DGME FTEs and IME FTEs, and hospitals in Louisiana, Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia received the fewest.[34] (See fig. 4.)

Notes: Figure depicts 600 GME residency positions—that is, 600 FTEs for Medicare DGME and 600 FTEs for IME—that CMS allocated in the first three annual distributions under Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. State includes the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Hospitals in eight states applied but did not receive positions. There were four states where hospitals did not apply in any distribution. See app. III, table 4, for the number of FTEs that CMS distributed for DGME and IME by state.

The effect of the increase in Section 126 residency position distributions was greater for some states. For example, for DGME, seven states had a 3 percent or greater increase in FTEs above the total number of FTEs reimbursed by Medicare, while the median increase in states was 1 percent, as of 2023.[35]

Characteristics of Hospitals and Residency Programs

Hospitals that received Section 126 residency positions in the first three annual distributions, from 2023 through 2025, were similar to hospitals that applied for and did not receive positions. The majority of hospitals were urban, and most programs were accredited for 10 years or more. Additionally, hospitals that received positions were generally larger than those that did not receive positions in terms of cap size and total GME payments. (See app. III for additional information on these comparisons.)

Hospital Characteristics

Urban or rural. Nearly all (95 percent) of the 186 hospitals that received positions in the first three distributions were in geographically urban areas, while 5 percent were in geographically rural areas.[36] Geographically urban hospitals also were more likely to apply for Section 126 residency positions than geographically rural hospitals. Specifically, among hospitals that may have been eligible for Section 126, 27 percent of geographically urban hospitals applied compared to 8 percent of geographically rural hospitals.[37] Although the proportion of hospitals in geographically urban areas that received positions was similar to those that did not receive positions (46 percent and 54 percent, respectively), nearly all (90 percent) of geographically rural hospitals that applied received positions in at least one distribution.

Some geographically urban hospitals that received positions participate in residency programs where a portion of the residents’ training occurs in rural areas. Specifically, 15 percent of geographically urban hospitals received positions for residency programs with at least one training site in a rural area. For example:

· residents at a geographically urban hospital in New Mexico that received Section 126 positions spend most of their third year of residency training at a rural Indian Health Service site; and

· residents at a geographically urban hospital in Oregon that received Section 126 positions also train at four rural sites during their second and third years of residency training.

Additionally, we found that three geographically urban hospitals that received positions did so for residency programs with a Rural Track Program designation from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which indicates more than half of the residents’ training is conducted in rural areas.[38]

Size and patient mix. Hospitals that received Section 126 residency positions were somewhat larger, as measured by the hospital-specific limit on the number of medical resident positions that Medicare will fund (i.e., cap size), and by Medicare GME payments, compared to hospitals that applied for and did not receive positions. Also, hospitals that received positions had a smaller Medicare patient share and a larger Medicaid patient share compared to hospitals that applied for but did not receive Section 126 residency positions. (See app. III for additional information on these comparisons.)

Residency Program Characteristics

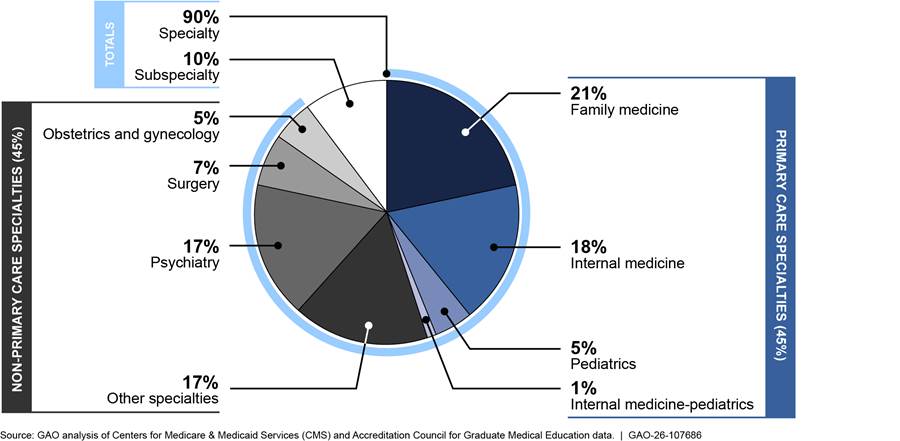

Specialty. Almost half (45 percent) of the 308 applications from hospitals that received positions in the first three annual distributions applied to add residents to programs training in primary care specialties.[39] In addition, we found that few hospitals applied for and received positions for subspecialty programs.[40] Nearly all (90 percent) of the hospitals that received positions applied for positions for specialty programs, which includes non-primary care specialties such as psychiatry, surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. (See fig. 5.) The composition of specialty and subspecialty programs that received positions in the first three distributions of Section 126 was similar to what we found in previous work. For example, in April 2021, we reported that nearly half of residents during the 2019-2020 academic year trained in a specialty program in one of the primary care specialties.[41]

Figure 5: Percentage of Applications from Hospitals That Received Section 126 Residency Positions, by Specialty and Subspecialty Programs, 2023–2025

Notes: Figure represents applications from hospitals that received positions in the first three annual distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. Each year, hospitals could apply for positions in only one specialty or subspecialty residency program. However, hospitals could apply with a different residency program and receive positions in other distributions. Specialty percentages may not add up to totals due to rounding.

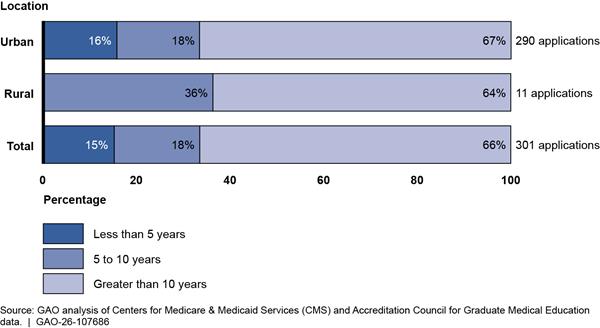

Length of accreditation. Most Section 126 residency positions were distributed to hospitals with existing residency programs. Additionally, almost two-thirds of the residency programs at hospitals that received positions had been accredited for more than 10 years; all geographically rural hospitals that received positions had been accredited for more than 5 years. (See fig. 6).

Figure 6: Residency Program Age for Applications from Hospitals That Received Section 126 Residency Positions, by Urban or Rural Status, 2023–2025

Note: Figure represents applications from hospitals that received residency positions in the first three annual distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. Each year, hospitals could only apply for positions in one specialty or subspecialty residency program. However, hospitals could apply with a different program and receive positions in other distributions. The total number of applications from hospitals that received residency positions is 301 versus 308 (total number that received positions in the three distributions) because we excluded hospitals with missing residency program age data. Percentages do not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Selected Stakeholders Identified Benefits to Training, Workforce, and Funding of Section 126 Medical Residents

Representatives of selected stakeholders, including hospitals that received Section 126 residency positions, described three key benefits of the additional resident positions received through Section 126 funding: enhanced resident training, an expanded physician workforce, and increased funding to sustain medical residency programs.[42]

Training. Representatives of four selected hospitals described how expanding their programs allowed them to enhance their training by offering more opportunities to residents. For example:

· Representatives of one geographically rural hospital told us that expanding their family medicine program from six residents (two per year) to nine residents (three per year) allowed them to integrate a teaching model into their program whereby senior residents mentor more junior residents while still having enough available residents to support patient care. They said their hospital had looked for funding to expand this program for about 11 years.

· Representatives of one geographically urban hospital said the positions they received for their internal medicine program enabled them to provide their residents with a better combination of inpatient and outpatient training experiences. They said the additional outpatient training had made it easier for residents to see the same patients for follow-up care, which is important to their training. They said their program is now sufficiently sized for current patient care needs and the program’s educational priorities.

Workforce size. Representatives of four selected hospitals said the residency positions they received through Section 126 will help them recruit more physicians for their hospitals and, in some cases, expand physician services in their communities. For example, representatives of one hospital said that the population of their southwestern city had grown significantly since Medicare caps were frozen in the 1990s.[43] Hospital leadership, however, had been hesitant to expand training to meet increased community needs because the hospital was already training over its Medicare cap, according to hospital representatives.

Funding. Representatives of two stakeholders and three selected hospitals said that CMS’s distribution process ensures hospitals have a financially sustainable source of funding. For example, representatives of one stakeholder noted that CMS was responsive to stakeholder feedback during rulemaking by distributing up to five positions per hospital in each annual distribution based on the length of the residency program, instead of one position in each annual distribution as the agency originally proposed.[44] Representatives said the approach CMS implemented helps hospitals support residents for the full length of their required training. They said that hospitals often try to support an equal number of residents in each year of a program, which generally means they expand residency programs incrementally over multiple years. For example, a 3-year program, such as family medicine, may expand its program by one resident per year over a 3-year period, thus increasing the program by three total residents in the third year. In this example, the hospital could apply for up to for three positions per annual distribution, which would enable it to obtain Medicare funding for one new resident per year.

Selected Stakeholders Said That CMS Prioritization May Have Disadvantaged Some Hospitals and Identified Other Funding Challenges

Representatives of selected stakeholders, including hospital associations, physician specialty societies, and other groups, described two key concerns related to the distribution of residency positions through Section 126: CMS’s prioritization of applications by HPSA score and the distribution of fewer positions to hospitals in some qualifying categories. In addition, representatives of stakeholders and selected hospitals identified other funding challenges that may affect the use of additional positions or discourage some hospitals from applying.

HPSAs. Representatives from selected stakeholders said that decisions CMS made related to prioritizing applications with the highest HPSA scores may have disadvantaged some hospitals. For example, stakeholders identified the following two challenges related to these decisions.

· CMS’s decision to prioritize the applications with the highest HPSA scores may have disadvantaged some hospitals, according to representatives of six stakeholders. For example, representatives of one stakeholder said hospitals in communities with smaller populations, including rural areas, may have lower HPSA scores or no score at all, in part, because the population-to-provider ratio has a significant effect on the HPSA score calculation. They said adding a small number of physicians to a community of a few thousand people could lead to the reduction in an area’s HPSA score or not having a HPSA designation at all.

· CMS’s decision to permit hospitals to submit a HPSA for prioritization only if 50 percent or more of resident training would take place within the specified HPSA may have disadvantaged some hospitals, according to representatives of three stakeholders.[45] For example, representatives of two stakeholders said some hospitals may train residents in HPSAs for less than 50 percent of their training time because a portion of the training occurs at partner sites located in an area outside of the specified HPSA. Additionally, though a hospital may not be in a shortage area, it may provide care to patients who reside in HPSAs and travel to hospitals outside of that area to receive care, according to representatives from three stakeholders.

In its fiscal year 2022 final rule, CMS noted that HPSA scores are relative measures applied uniformly to communities of all sizes.[46] The agency stated these scores are beneficial because, for example, they are transparent, widely used, and publicly available. The agency also stated that requiring 50 percent of training to take place in the HPSA specified on the application would help CMS allocate Section 126 residency positions to the hospitals most likely to provide care to communities with the greatest need and was, thus, appropriate given the limited number of positions available to distribute. It acknowledged that some hospitals provide care to patients who travel from other HPSAs and stated that adding a measure of care provided to patients from other HPSAs could warrant consideration in the future.

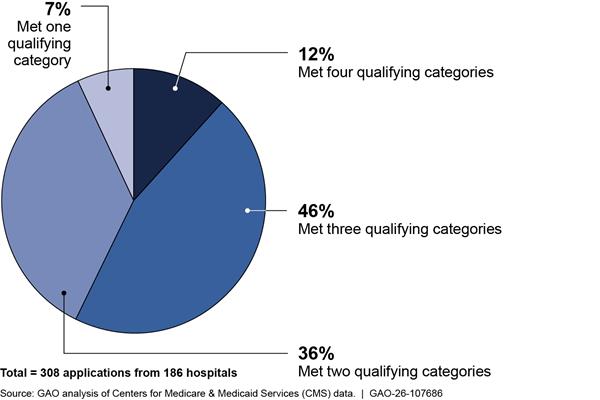

Qualifying categories. Stakeholder representatives provided their perspectives on the qualifying categories CMS used to distribute Section 126 positions. For example, representatives of four stakeholders said they were concerned that CMS had not distributed Section 126 residency positions equitably among hospitals in each qualifying category, in part, because of the reliance on HPSA scores to prioritize their distribution. In its fiscal year 2022 final rule, CMS responded to this concern by noting that applicant hospitals could meet multiple qualifying categories established by the CAA, 2021. As a result, CMS inferred that prioritizing applications by the highest HPSA score would allow it to meet the statutory requirement to distribute 10 percent of the 1,000 authorized GME residency positions to hospitals in each category.[47] We found that almost all (93 percent) of the 308 applications from hospitals that received additional positions were from hospitals that met two or more qualifying categories. (See fig. 7.)

Figure 7: Percentage of Applications from Hospitals That Received Section 126 Residency Positions, by Number of Qualifying Categories Met, 2023–2025

Notes: Under Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 hospitals have to meet at least one of four qualifying categories to receive positions. Qualifying category one refers to hospitals in a geographically rural area or treated as rural. Qualifying category two refers to hospitals training more residents than Medicare reimburses—that is, the hospital is training above its established DGME or IME caps. Qualifying category three refers to hospitals in a state or U.S. territory with a new medical school or branch campus established on or after January 1, 2000. Qualifying category four refers to hospitals serving areas designated as geographic health provider shortage areas. Hospitals could apply for positions in multiple distributions and therefore can have more than one application. Percentages do not add up to 100 due to rounding.

In its fiscal year 2022 final rule, CMS noted that it had considered an alternative prioritization approach that prioritized applicants that met the most qualifying categories.[48] According to the agency, CMS decided not to adopt this approach, in part, due to concerns it would disadvantage hospitals in states that did not have new medical schools or branch campuses (qualifying category three), including some rural states.

In addition, representatives of two stakeholders expressed concerns that the Section 126 statutory requirement to include rural reclassified hospitals with geographically rural hospitals in qualifying category one may have affected the distribution of residency positions to geographically rural hospitals.[49] Of the 98 rural and rural reclassified hospitals that received positions, we found that 91 percent were geographically urban hospitals that had been reclassified as rural. In addition, 89 percent of rural reclassified hospitals that received positions were designated as rural referral centers.[50] However, we also found that few geographically rural hospitals applied to receive positions in the first three annual distributions. Specifically, of the 393 hospitals that applied for positions in the first three distributions, 10 were geographically rural hospitals. Nine of these 10 hospitals received positions. CMS worked to help ensure geographically rural hospitals were aware of the additional positions available through Section 126, including by sharing information about the application process in three HRSA webinars.

In addition to comments regarding the qualifying categories established for Section 126, stakeholder representatives identified other ways to distribute residency positions. For example, representatives from eight stakeholders suggested that CMS create additional criteria to better target hospitals with the greatest level of need. CMS stated in its fiscal year 2022 final rule that the agency could only use additional criteria to further prioritize hospitals that met at least one of the four Section 126 qualifying categories. The criteria that stakeholder representatives suggested aligned with their interests and included distributing positions to hospitals that

· provide care to underserved communities, such as at safety-net hospitals or tribal hospitals;

· train physicians in medical specialties that align with community needs;

· use an interdisciplinary approach to care bringing together primary care and behavioral health providers, due to the need for mental health care services and shortages of those providers; and

· are in states with fewer residency programs, noting that some states without medical schools have more challenges attracting physicians, or are training above their Medicare caps.

|

Distribution of Residency Positions Planned for 2026 in Addition to Section 126 Section 4122 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 directs the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to distribute an additional 200 graduate medical education residency positions in 2026, with 100 of these positions allocated for psychiatric residency programs. These are separate from the positions funded through Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. Source: Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 Pub. L. No. 117-328. ꟾ GAO‑26‑107686 |

Position use. In addition to identifying challenges with the Section 126 residency position distribution criteria, selected stakeholders and hospitals also identified more general challenges with using and funding residency positions. Representatives from two of the seven selected hospitals we interviewed told us they have not been able to use the residency positions they received, in part, because they would have to self-fund a portion of the training for these additional residents not covered by the Section 126 funding. As of August 2025, neither hospital planned to use these positions, though they have the option to do so at a later date.[51] These two hospitals described their circumstances as follows.

· Representatives of one urban hospital told us they requested Section 126 positions for a new rural-focused training pathway within an existing 5-year surgery residency program. They requested five positions but received about 2.5 positions, which was the share of training time the hospital would be financially responsible for in the program. Representatives said they had intended to have residents spend 50 percent of their training time at a rural training site, but that plan was no longer viable due to a change in hospital leadership priorities. As a result, they said they would likely need to secure additional funding for additional residents in their surgery program, because nearly all training would occur at their hospital.

· Representatives of the other hospital told us they had not yet been able to use the Section 126 positions they received for their psychiatry program because they only received additional FTEs for IME and did not receive additional FTEs for DGME. This hospital’s request for additional FTEs for DGME was not fulfilled because it was one of 10 hospitals with the same HPSA score and CMS had too few remaining FTEs to fulfill their requests. CMS distributed the remaining FTEs to three other hospitals with fewer than 250 beds.

Representatives we interviewed from the other five selected hospitals said they had either fully used the positions they received or had no concerns with doing so within 5 years as attested in their applications.

In its final rule implementing Section 126, CMS stated it would consider actions for future rulemaking if hospitals were not using Section 126 residency positions for their intended purposes.[52] CMS officials told us in April 2025 that the agency did not currently have plans to review each hospital’s efforts to use these positions. They noted that Medicare Administrative Contractors conduct regular reviews of hospital Medicare Cost Reports, and these reviews could identify discrepancies related to residency positions distributed through Section 126.[53] The CAA, 2021 also includes a provision that we examine and report on the distribution of positions through Section 126 again by September 30, 2027.[54]

Lack of other funding. Stakeholder representatives also stated that hospitals needed to consider other sources of funding when beginning or expanding a residency program, including through Section 126. Specifically, they identified two key challenges.

· Hospitals can face significant up-front costs when starting new residency programs, according to representatives of nine stakeholders. It can be particularly challenging for hospitals that provide care to underserved or rural communities to fund the increases to staffing and additional space or equipment that may be required to begin a residency program, according to representatives of eight stakeholders. For example, representatives of one stakeholder group said there are only six residency programs based in tribal communities in the United States and noted that these communities are often in rural areas.[55] They said there is a need for more programs to help increase the physician workforce in these communities; however, these communities may lack the administrative staff or other resources to start new residency programs. In addition, representatives of three stakeholders said that Medicare GME funding does little to help hospitals with up-front costs because Medicare only reimburses hospitals for certain costs after a program is training residents.

· Hospitals may need other funding to maintain accreditation when increasing the size of an existing residency program, according to representatives of five stakeholders. For example, representatives of the three geographically rural hospitals we interviewed said they may need additional faculty to comply with the resident-to-faculty ratios required for accreditation if they expanded beyond the increase in residents supported by Section 126.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Administrator of CMS, the Administrator of HRSA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GordonLV@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in app. IV.

Leslie V. Gordon

Director, Health Care

List of Committees

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

This report describes the distribution of graduate medical education (GME) residency positions under Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 during the first three of five annual distributions.[56] Specifically, it describes (1) the number of hospitals that applied for and received Section 126 residency positions and the characteristics of these hospitals, (2) benefits of the Section 126 residency positions identified by selected stakeholders, and (3) challenges identified by selected stakeholders related to the application for and the distribution of these additional positions.

To address these objectives, we reviewed relevant statutes, regulations, and guidance, as well as agency documentation of the distribution process implemented for the first three annual distributions from 2023 through 2025, which were the distributions completed at the time of our review. We interviewed Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) officials responsible for distributing these positions. We also interviewed officials from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to better understand how the agency assesses health workforce shortages, categorizes rural and shortage areas, and supports graduate medical education through its grant programs.

To identify the number of hospitals that applied for and received additional positions in the first three annual distributions, we analyzed hospital application data that CMS collected to determine the first three annual distributions, as well as information CMS used to document its determinations. For example, we examined these data to describe the four qualifying categories of hospitals that received positions. To compare the hospitals that applied for Section 126 residency positions to hospitals that did not apply, we estimated the number of hospitals that may have been eligible for Section 126 distributions. Using 2023 Medicare Cost Reports, we identified hospitals that met one or more of the following criteria: Section 126 applicant, teaching hospital, or received a Medicare Direct Graduate Medical Education (DGME) or Indirect Medical Education (IME) payment in 2023.[57] We also limited the estimate to hospitals in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territory (Puerto Rico) where hospitals applied for and received positions under Section 126. We also limited the estimate to hospitals that had filed a Cost Report for fiscal year 2023 that covered a period of time from about 10 months to 14 months.

To describe distributions made, as well as the characteristics of hospitals and residency programs, we analyzed data from the following sources.

CMS application and distribution data. We analyzed CMS Section 126 application data submitted by hospitals that applied for and received Section 126 positions, as well as information CMS used to document its residency distribution determinations to examine

· geographic location of the hospital that applied for and received positions, including urban, rural, or geographic reclassification status;[58]

· whether the hospital applied for positions for either a new or an existing residency training program;[59] and

· type of Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) designation—a measure used to designate areas experiencing a shortage of providers, such as primary care or mental health providers in a geographic area or population group managed by HRSA—and the HPSA score submitted by hospitals.

CMS Medicare Cost Reports. We analyzed 2023 Medicare Cost Reports—the most recent reliable data available at the time of our analysis—for the following hospital characteristics:[60]

· number of beds;

· DGME and IME payments and resident caps;

· Medicare and Medicaid patient share—calculated as the percentage of Medicare or Medicaid inpatient days as a share of total days; and

· type (e.g., acute care, long-term care, inpatient psychiatric and rehabilitation, and cancer, and children’s).

CMS Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System’s Final Rule Impact File. We analyzed the fiscal year 2024 file to obtain additional information about the type of acute care hospital for those paid under the prospective payment system hospital type (e.g., rural referral center).

HRSA Federal Office of Rural Health Policy’s Eligible Rural Zip Codes. To understand if geographically urban hospitals that received positions were partnering with participating training sites in rural areas, we examined if the zip codes of hospitals’ participating sites were considered rural under the definition created by HRSA’s Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, as of October 2024.[61] We used this dataset because zip codes and rural indicators were available for participating training sites of hospitals that received positions.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education data. We analyzed residency program reported data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for the 2023-2024 academic year.[62] We used these data to analyze the following:

· residency program specialty and subspecialty;

· accreditation date, to determine how long the program has been accredited;

· training site information; and

· rural track programs.

In addition, for hospitals that applied for, but did not receive positions, and hospitals that may have been eligible for Section 126, we used two other CMS data sources. We used CMS’s Provider of Services’ Quarter Three 2024 file to determine urban or rural status. Additionally, we used the CMS Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System’s Fiscal Year 2024 Final Rule Impact File to determine whether a hospital was eligible for rural reclassification.

To assess the reliability of the data we analyzed—that is, data obtained from CMS, HRSA, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education—we obtained and reviewed relevant information and interviewed knowledgeable agency officials about the accuracy of the data. For these data sources, we performed checks to identify and take steps to adjust for missing or incorrect data. Based on these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

To describe the benefits and challenges identified by selected stakeholders related to the distribution of residency positions through Section 126, we interviewed or received comments from 14 stakeholders including representatives of hospitals, physicians, the accrediting body for GME programs, and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) advisory councils. The 14 stakeholders we interviewed were chosen to represent a broad range of perspectives. As a part of this, we spoke with representatives of an academic research center and a multistate GME program that encourages residents to practice in rural areas to better understand considerations that affect rural residency programs (see table 1 for a list of the 14 selected stakeholders). In addition, we analyzed Section 126 hospital application data and reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of public comments that discussed Section 126 and were part of CMS’s Inpatient Prospective Payment System rulemaking for fiscal years 2022 and 2025.

Table 1: List of Selected Stakeholders

|

Organization |

|

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education |

|

American Academy of Family Physicians |

|

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

|

American College of Surgeons |

|

American Hospital Association |

|

American Psychiatric Association |

|

America’s Essential Hospitals |

|

Association of American Medical Colleges |

|

Council on Graduate Medical Education |

|

Federation of American Hospitals |

|

Society of General Internal Medicine |

|

The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research |

|

Tribal Technical Advisory Group |

|

Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho Medical Education Program |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107686

Note: Some of these stakeholders provided written answers to our questions.

We also interviewed representatives of a nongeneralizable sample of seven hospitals that received Section 126 residency positions in the first two distributions. At the time of our selection, CMS had completed two annual distributions. We selected hospitals based on their geographic designations, census regions, medical specialties specified in their applications, and whether they applied using a new or existing residency program. The information we obtained from the selected 14 stakeholders and seven hospitals is not generalizable to the experiences or views of other entities.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021 requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services to distribute 1,000 additional graduate medical education (GME) residency positions to qualifying hospitals through permanent increases to their resident caps over at least 5 years.[63] Based on the requirements outlined in the CAA, 2021 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed and sought public comments on its distribution policies before finalizing them.[64]

Table 2 outlines selected provisions in the CAA, 2021 and the corresponding policy CMS implemented to distribute the Section 126 positions to hospitals.

|

Section 126 provision summarya |

CMS distribution policy |

|

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to consider likelihood the hospital would fill the residency positions within 5 years of the distribution effective date.b |

· Hospitals attested to filling graduate medical education (GME) residency positions within 5 years · Hospitals indicated on application to having · sought approval of new residency program from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education or American Board of Medical Specialties; · sought approval from those entities to expand size of existing residency program; or · unfilled positions previously approved.c |

|

Hospital may not receive more than 25 residency positions. |

· Hospitals permitted to request up to five GME residency positions per year, not to exceed the length of the residency programd · Hospitals permitted to submit one application per year for one residency program (i.e., specialty or subspecialty) · Hospitals attested that request for GME residency positions was only for the amount of training occurring at the applicant hospital or certain nonprovider sitese |

|

HHS to distribute residency positions to qualifying hospitals that submit timely applications, subject to other provisions (e.g., the limit on the number of positions available to distribute).f |

· Hospitals permitted to submit geographic or population Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) score with application, which CMS used to prioritize distributionsg · If HPSA submitted, hospitals attested that at least 50 percent of residents’ training time (to include Veterans Affairs’ facilities and non-provider sites) for the associated program occurs within the HPSAh |

|

HHS to distribute residency positions to hospitals meeting one of four criteria, one of which is serving geographic HPSAs. |

· Hospitals indicated on application the qualifying categories they meet · If hospitals indicated they serve a geographic HPSA, hospitals attested that at least 50 percent of residents’ training time for the associated program occurs within the HPSA (to include Veterans Affairs’ facilities and non-provider sites)h · Hospitals applying with mental health HPSAs must request GME residency positions for psychiatry or psychiatric subspecialty residency programs |

Source: GAO analysis of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021 and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) information. | GAO‑26‑107686

aPub. L. No. 116-260, div. CC, § 126, 134 Stat. 1182, 2967 (2020).

bThe CAA, 2021 permits hospitals to share Section 126 residency positions with other hospitals in their systems through affiliation agreements in the fifth year after the effective date of the full-time equivalent resident cap increases.

cAccording to CMS officials, hospitals in their initial 5-year cap setting period are not eligible to apply as a new program.

dDue to this requirement, a hospital requesting positions for a 3-year residency program, such as internal medicine, can request a maximum of three Section 126 residency positions in each annual distribution. However, due to the 5-year limit, a hospital requesting positions for a 7-year residency program, such as neurological surgery, can request a maximum of five Section 126 residency positions per distribution.

eA hospital may count resident training time spent at certain non-hospital training sites under certain circumstances. See 42 C.F.R. § 413.78 (2024).

fA qualifying hospital is defined as (1) hospitals in rural areas or treated as rural; (2) hospitals training above their caps; (3) hospitals in states with new medical schools or branch campuses of medical schools; and (4) hospitals that serve geographic HPSAs.

gHPSAs designate areas experiencing a shortage of providers, such as primary or mental health care providers. An area may have multiple HPSA designations, and HPSA scores for primary care and mental health care range from 0-25, with a higher HPSA score indicating a greater shortage.

hHospitals can meet the requirement with a lower threshold (5 percent within a HPSA) if, when combined with training time at Indian or tribal facilities located outside the HPSA, that time is at least 50 percent of the residents’ training time.

Appendix III: Characteristics of Hospitals That May Have Been Eligible for or Applied for Section 126 Residency Positions

This appendix provides additional information on hospitals that may have been eligible to apply for Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021 or hospitals that applied for and received additional positions in the first three annual distributions (2023 through 2025). Specifically,

· Table 3 provides information on the applications from hospitals for Section 126 positions by annual distribution.

· Table 4 provides information on the full-time equivalents (FTE) that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) distributed for Medicare Direct Graduate Medical Education (DGME) and Indirect Medical Education (IME) to hospitals under Section 126 of the CAA, 2021 by state.[65]

· Tables 5-9 provide information on hospitals by characteristic, and information on hospitals that may have been eligible to apply, as well as hospitals that applied for Section 126 positions.

· Table 5 provides information on rurality, bed size, and hospital type.

· Table 6 provides information on medical specialty, length of accreditation, and type of Section 126 program.

· Table 7 details percent quartiles for Medicare DGME and IME resident caps.

· Table 8 details percent quartiles for Medicare DGME and IME payment amounts.

· Table 9 details percent quartiles for Medicare and Medicaid patient share.

· Table 10 provides information on FTEs for Medicare DGME and IME that CMS distributed to hospitals in the first three distributions by hospital characteristic. Specifically, this table details rurality, bed size, hospital type, medical specialty, length of accreditation, and the type of Section 126 program.

Table 3: Section 126 Residency Position Applications from Hospitals, by Annual Distribution, 2023–2025

|

Annual distribution |

Total applications submitted by hospitals |

Hospitals that received positions |

Hospitals that did not receive positions |

|

Distribution 1 (2023) |

291 |

100 (34%) |

191 (66%) |

|

Distribution 2 (2024) |

229 |

99 (43%) |

130 (57%) |

|

Distribution 3 (2025) |

206 |

109 (53%) |

97 (47%) |

|

Total |

726 |

308 (42%) |

418 (58%) |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. ꟾ GAO‑26‑107686

Notes: Table represents applications from hospitals in the first three annual distributions of Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021. The total does not represent mutually exclusive hospitals because hospitals could apply for Section 126 of the CAA, 2021 in multiple distributions.

|

|

Number of FTEs received for DGME |

Number of FTEs received for IME |

|

All hospitals |

600 |

600 |

|

Alabama |

6.40 |

16.07 |

|

Alaska |

○ |

○ |

|

Arizona |

40.27 |

36.81 |

|

Arkansas |

◒ |

◒ |

|

California |

18.78 |

24.22 |

|

Colorado |

5.87 |

4.44 |

|

Connecticut |

2.58 |

4.85 |

|

Delaware |

8.83 |

8.17 |

|

District of Columbia |

1.85 |

0.00 |

|

Florida |

45.43 |

59.09 |

|

Georgia |

39.50 |

29.15 |

|

Hawaii |

◒ |

◒ |

|

Idaho |

1.50 |

5.75 |

|

Illinois |

54.60 |

52.32 |

|

Indiana |

5.20 |

6.47 |

|

Iowa |

11.67 |

11.67 |

|

Kansas |

13.39 |

11.17 |

|

Kentucky |

5.02 |

5.02 |

|

Louisiana |

1.59 |

2.92 |

|

Maine |

◒ |

◒ |

|

Maryland |

○ |

○ |

|

Massachusetts |

3.42 |

0.00 |

|

Michigan |

21.90 |

25.24 |

|

Minnesota |

16.12 |

11.71 |

|

Mississippi |

20.31 |

20.35 |

|

Missouri |

26.32 |

20.09 |

|

Montana |

4.00 |

0.65 |

|

Nebraska |

◒ |

◒ |

|

Nevada |

5.50 |

14.70 |

|

New Hampshire |

○ |

○ |

|

New Jersey |

◒ |

◒ |

|

New Mexico |

6.33 |

6.33 |

|

New York |

98.12 |

99.40 |

|

North Carolina |

29.43 |

23.17 |

|

North Dakota |

3.00 |

3.00 |

|

Ohio |

15.10 |

8.62 |

|

Oklahoma |

8.56 |

8.56 |

|

Oregon |

7.76 |

2.80 |

|

Pennsylvania |

8.94 |

0.08 |

|

Puerto Rico |

2.33 |

2.33 |

|

Rhode Island |

◒ |

◒ |

|

South Carolina |

2.50 |

11.50 |

|

South Dakota |

2.83 |

5.10 |

|

Tennessee |

15.18 |

13.74 |

|

Texas |

9.58 |

11.94 |

|

Utah |

◒ |

◒ |

|

Vermont |

◒ |

◒ |

|

Virginia |

7.76 |

7.18 |

|

Washington |

4.00 |

5.27 |

|

West Virginia |

16.03 |

13.36 |

|

Wisconsin |

2.52 |

6.75 |

|

Wyoming |

○ |

○ |

DGME = Direct Graduate Medical Education

FTE= full-time equivalent

IME = Indirect Medical Education

○ = Did not apply, did not receive positions; ◒ = Applied, but did not receive positions

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) information. | GAO‑26‑107686

Notes: Table depicts the 600 GME residency positions—that is, 600 FTEs for Medicare DGME and 600 FTEs for IME—that CMS allocated in the first three annual distributions under Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. Medicare DGME and IME payments to hospitals are each limited by a hospital-specific cap on the number of FTE medical residents used to calculate the payments, and a hospital’s Medicare resident caps are generally permanent. State includes the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Table 5: Number of Hospitals That May Have Been Eligible or Applied for Section 126 Residency Positions, by Characteristic, 2023–2025

|

|

|

|

Hospitals that applieda |

|

|

|

|

Number of eligible hospitalsb |

Number of hospitals that received positions (percent) |

Number of hospitals that did not receive positions (percent) |

|

All hospitals |

|

1,519 (100%) |

186 (47%) |

207 (53%) |

|

Ruralityc |

Urban |

1,396 (92) |

177 (95) |

206 (100) |

|

Rural |

123 (8) |

9 (5) |

1 (0) |

|

|

Bed size |

Small (138 or fewer beds) |

378 (25) |

13 (7) |

15 (7) |

|

Medium (139-390 beds) |

761 (50) |

72 (39) |

96 (46) |

|

|

Large (391 or more beds) |

377 (25) |

101 (54) |

96 (46) |

|

|

Hospital type |

Acute care, general hospitals |

1,357 (89) |

180 (97) |

194 (94) |

|

Acute care hospitals |

760 (50) |

82 (44) |

95 (46) |

|

|

Rural referral centers |

451 (30) |

80 (43) |

90 (43) |

|

|

Other rural hospitalsd |

145 (10) |

18 (10) |

9 (4) |

|

|

Indian health service |

1 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

|

Specialty hospitals |

162 (11) |

6 (3) |

13 (6) |

|

|

Children’s |

54 (4) |

6 (3) |

9 (4) |

|

|

Cancer |

11 (1) |

0 (0) |

2 (1) |

|

|

Long-term care |

7 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.5) |

|

|

Psychiatric |

56 (4) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.5) |

|

|

Rehabilitation |

34 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

DGME= Direct Graduate Medical Education

IME= Indirect Medical Education

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) information. | GAO‑26‑107686

Notes: Counts in the table may not add up to the number of hospitals due to missing data. Percentages do not add up due to rounding.

aRepresents the 393 hospitals that applied for or received positions in the first three annual distributions under Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021.

bTable includes the 1,519 eligible hospitals that met one or more of the following criteria: Section 126 applicant, teaching hospital, or received a graduate medical education payment in 2023. We also limited the analysis to hospitals in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territory (Puerto Rico) where hospitals applied for and received positions under Section 126.

cCMS generally considers a hospital to be geographically rural if it is located outside of a metropolitan statistical area—as defined by the Office of Management and Budget.

dOther rural hospitals may include hospitals, such as Sole Community Hospitals—geographically isolated hospitals that serve a disproportionate number of low-income Medicare and Medicaid inpatients—located in urban areas with active urban-to-rural reclassification under 42 C.F.R. § 412.103.

Table 6: Number of Section 126 Residency Position Applications from Hospitals, by Residency Program Characteristic, 2023–2025

|

|

|

Number of hospitals that received positions (percent) |

Number of hospitals that did not receive positions (percent) |

|

|

All hospitals |

|

308 (100%) |

418 (100%) |

|

|

Medical specialty |

Specialty |

277 (90) |

373 (89) |

|

|

Subspecialty |

31 (10) |

45 (11) |

||

|

Primary care specialtya |

Primary care specialty |

138 (45) |

187 (45) |

|

|

Non-primary care specialty |

170 (55) |

231 (55) |

||

|

Length of accreditation |

Less than 5 years |

46 (15) |

66 (16) |

|

|

5 to 10 years |

55 (18) |

70 (17) |

||

|

More than 10 years |

200 (65) |

258 (62) |

||

|

Type of Section 126 program |

New program |

44 (14) |

41 (10) |

|

|

Existing program |

264 (86) |

352 (84) |

||