RARE DISEASES

Funding for Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Research and Access to ALS Investigational Drugs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: John E. Dicken at dickenj@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) awarded about $276 million from fiscal years 2022 through 2025 to implement the Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act (ACT for ALS Act). Most of this funding was awarded by (1) NIH for grants that supported access to investigational drugs—drugs not yet approved for marketing by FDA—for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and related research (45 percent) and (2) NIH and FDA for a public-private partnership focused on rare neurodegenerative disease research (45 percent). FDA also awarded grants and contracts for research to further scientific knowledge on ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases and for the clinical development of therapies (10 percent). About 750 individuals with ALS are expected to receive access to investigational drugs through the NIH grants.

Summary of Funding Awarded by NIH and FDA to Implement the Accelerating Critical Therapies for ALS Act, Fiscal Years (FY) 2022 through 2025 (in millions)

|

|

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

TOTAL |

|

NIH grants for access to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) investigational drugs and related research |

$18.1 |

$32.5 |

$39.2 |

$35.4 |

$125.3 (45%) |

|

NIH and FDA funding for rare neurodegenerative disease public-private partnership |

$5.5 |

$42.3 |

$36.0 |

$40.6 |

$124.4 (45%) |

|

FDA grants and contracts for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative disease research |

$5.8 |

$5.1 |

$5.5 |

$10.1 |

$26.5 (10%) |

|

TOTAL |

$29.4 |

$79.9 |

$80.7 |

$86.2 |

$276.3 |

Source: GAO analysis of documentation from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and interviews with agency officials, as of December 2025. | GAO-26-107691

Note: The awarded funds include those appropriated by Congress specifically to implement the act, as well as funds identified by FDA from other sources. Totals may not add up due to rounding and do not include funds used to administer the funding awarded.

NIH and FDA officials identified challenges to implementing the ACT for ALS Act (particularly in fiscal year 2022) and took actions to address those within their control. For example, applicants had limited time to apply for NIH grants in fiscal year 2022 because appropriations were not available until midway through the fiscal year. As a result, in later years NIH posted requests for grant applications prior to appropriations being enacted. However, other challenges were outside the agencies’ control—including no direct appropriations to FDA to support its priorities for other rare neurodegenerative diseases for the public-private partnership, according to agency officials.

Stakeholder interviews, available literature, and NIH data indicated benefits of NIH and FDA funding, such as increases in the number and geographic diversity of clinic sites providing access to ALS investigational drugs. However, most of the research funded by NIH and FDA is ongoing and the full effects are not yet known. Anticipated benefits include increased data on ALS and addressing research gaps for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases. For example, stakeholders expect these data to be useful to ALS research because the data will meet high data quality standards and will be available for other researchers.

Why GAO Did This Study

ALS is a rare, progressive, and ultimately fatal neurological disorder. As with other rare diseases, diagnosis may be delayed, affecting the eligibility of individuals with ALS to participate in clinical trials. ALS has no cure and limited treatment options. Physicians or drug sponsors can request FDA authorization to make investigational drugs available outside of clinical trials for individuals with serious or life-threatening diseases through FDA’s expanded access pathway.

The ACT for ALS Act includes a provision for GAO to report on the funding NIH and FDA awarded to implement the act. This report describes the funding NIH and FDA awarded to implement the act, challenges NIH and FDA identified in awarding that funding, and what is known about the effect of the funding on research and development of therapies for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases.

GAO reviewed relevant laws, congressional reports, NIH and FDA documentation, and grant and contract applications and progress reports. GAO also reviewed relevant data in NIH databases as of November 2025 on the research studies funded to implement the act. GAO interviewed NIH and FDA officials and a nongeneralizable sample of 21 stakeholders—including national associations, NIH and FDA grant recipients, drug sponsors, clinic sites, public-private partnership entities, and a committee of individuals with ALS and caregivers. GAO selected stakeholders to attain variation in perspectives on ALS research implemented through the act and in organization type involved in clinical research. GAO also reviewed research relevant to the awarded funding published from January 2019 through September 2025.

Abbreviations

ACT for ALS Act Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act

ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

FDA Food and Drug Administration

NIH National Institutes of Health

RePORTER Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 4, 2026

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

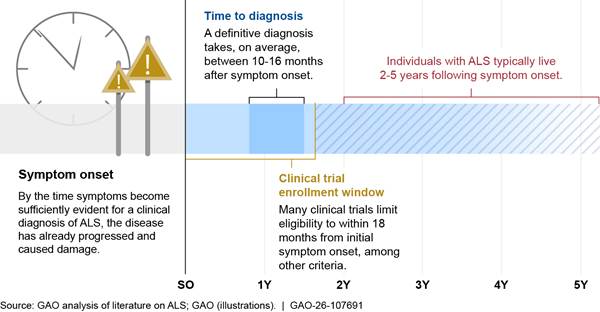

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease—is a rare, progressive, and ultimately fatal neurological disorder affecting nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that control muscle movement and breathing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 5,000 new individuals, on average, are diagnosed with ALS each year and approximately 34,000 individuals in the United States were living with ALS in 2025. Similar to other rare diseases, individuals with ALS may experience a delay in diagnosis. For ALS, it takes between 10 to 16 months on average for a definitive diagnosis after symptom onset. As a progressive disease, ALS symptoms worsen over time, and individuals with ALS typically survive 2 to 5 years after diagnosis, though the disease progression can vary and be shorter or longer for some individuals.

There is no known cure for ALS, and treatment options for the disease are limited. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a few drugs for ALS treatment; however, these provide only limited benefits for individuals with ALS. In addition, many individuals with ALS are also ineligible to participate in clinical trials of investigational drugs because of the rapid progression of the disease and delays in diagnosis.[1]

Through FDA’s expanded access pathway, physicians or drug sponsors can request authorization from FDA to make investigational drugs available to individuals with serious or life-threatening conditions, such as ALS, when enrollment in a clinical trial is not possible.[2] For the purposes of this report, we refer to the discrete programs that FDA allows to provide individuals with investigational drugs under FDA’s expanded access pathway as expanded access programs. Historically, access to investigational drugs for ALS through expanded access programs has been limited, according to research articles. Access has been limited in part due to the additional resources needed to operate an expanded access program, including resources for monitoring individuals who receive the investigational drugs.[3]

In December 2021, the Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act (ACT for ALS Act) was enacted to further research and development of therapies for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases and increase access to investigational drugs for individuals with ALS.[4] The ACT for ALS Act required the creation of specific programs to award funding that is provided by Congress through the annual appropriations process.[5] The funding—which is awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and FDA—is provided through the following programs authorized by the act.[6]

· Expanded access grants. NIH awards grants to institutions, such as healthcare facilities or academic institutions, to both conduct research on data collected from individuals with ALS and provide those individuals access to investigational drugs through expanded access programs (hereafter referred to as expanded access grants).

· Public-private partnership funding. NIH and FDA contribute funding to establish a public-private partnership for rare neurodegenerative diseases between NIH, FDA, and one or more other eligible entities.

· Rare neurodegenerative disease grants. FDA awards grants and contracts for research on ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases to further scientific knowledge about the diseases and to further the clinical development of therapies.

The ACT for ALS Act also includes a provision for us to report on funding awarded by NIH and FDA and what is known about the effect of this funding on ALS.[7] In this report we describe

1. the funding NIH and FDA have awarded to implement the ACT for ALS Act;

2. the challenges NIH and FDA identified in awarding funding to implement the ACT for ALS Act; and

3. what is known about the effects of the awarded funding on research or development of therapies for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases.

For all three objectives, we reviewed relevant laws and reports accompanying congressional appropriations as well as documentation from NIH and FDA about the programs and funding awarded to implement the ACT for ALS Act, any challenges encountered by the agencies, and any known effects of the funding. We also reviewed documentation from the entities that were awarded funding under the programs created by the act, including grant and contract applications, annual progress reports, and relevant publications. In addition, we interviewed NIH and FDA officials about the funding awarded, any challenges implementing the act, and the effect of the funding the agencies awarded.

To describe the funding NIH and FDA awarded, as well as the anticipated effect of the funding, we also reviewed grant summaries and data from two databases as of November 2025. First, NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results (NIH RePORTER) contains information about research projects funded by NIH and FDA, including funding amounts, length of the funding period, the funding recipient, and research goals. Second, ClinicalTrials.gov, also operated by NIH, contains additional information about expanded access programs, including those funded by the ALS expanded access grants, such as a description of the investigational drug and a list of participating clinic sites.[8] To assess the reliability of both databases we reviewed related documentation, interviewed agency officials knowledgeable about the databases, and compared the information in the databases to other publicly available information. On the basis of these steps, we found these data sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

To identify the potential effect of the funding, we also conducted a literature search for relevant peer-reviewed research published from January 2019 through October 2024. We conducted a structured search in multiple electronic databases using various terms related to our objective, including “expanded access” and “ALS” or “rare neurodegenerative disease,” and searches by grant number and recipient.[9] Additionally, we identified relevant articles through publications listed on NIH RePORTER as well as internet searches through September 2025. We reviewed search results to identify those that met the following criteria: (1) publications related to the specific grants and contracts awarded by NIH and FDA to implement ACT for ALS Act and (2) publications about individuals’ access to investigational drugs for ALS or other rare neurodegenerative diseases through expanded access programs both prior to and after the enactment of the act. As most of the grants and contracts awarded by the agencies are still ongoing, our literature search identified a relatively small number of articles describing the effects or potential effects.

Lastly, to further identify the potential effects of the funding, we interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 21 stakeholders.[10] This included representatives from five national ALS and rare disease organizations, six selected NIH and FDA grant and contract recipients, two drug sponsors with investigational drugs involved in the expanded access grants awarded by NIH, four selected clinic sites participating in the expanded access grants, the three public-private partnership entities, and one committee of individuals with ALS and caregivers. We selected national ALS and rare disease organizations for variation in their perspectives on the ACT for ALS Act, clinical trials, and expanded access programs. We selected grant and contract recipients for variation in the institution awarded the grant or contract, investigational drug, contract amount, or study topic. We selected drug sponsors and clinic sites for variation in their experience participating in clinical trials or expanded access programs before and after the act was enacted. The information we obtained from these stakeholders cannot be generalized to all ALS and rare disease organizations, grant and contract recipients, drug sponsors, clinic sites, or individuals with ALS and caregivers.[11]

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

ALS symptoms and disease progression vary by patient, contributing to a limited understanding of the disease and difficulties with new drug development. Due to the limited options of FDA-approved ALS treatments, individuals with ALS may seek out investigational drugs for treatment. Individuals may get access to investigational drugs in a variety of ways, such as through clinical trials or FDA’s expanded access pathway.

ALS Disease and Drug Development

Risk factors for ALS include genetic and environmental factors as well as age. According to the National Academies 2024 report Living with ALS, there are two main types of ALS—sporadic and familial—with sporadic ALS accounting for about 90 percent of the cases in individuals without a family history.[12] The report also notes that 70 percent of those with familial ALS are carriers of gene mutations associated with ALS. Presentation of symptoms is highly variable—two-thirds of individuals first experience symptoms of muscle weakness in limbs and another third experience difficulty speaking or swallowing. For all individuals with ALS, symptoms continue to progress to other parts of the body until the individual is fully paralyzed. Death occurs by respiratory failure typically within 2 to 5 years of symptom onset, though about 10 to 20 percent of individuals may live with ALS for longer than 10 years.

Due in part to the variability of risk factors, symptom presentation, and disease progression, there is limited understanding of the natural history of the disease or how to prevent or treat ALS.[13] For example, mutations in at least one of 50 or more genes are associated with both sporadic and familial ALS, contributing to the challenges of understanding and developing therapies to treat the disease. Furthermore, the lack of clinically proven, easy-to-measure biomarkers—specific molecular, biochemical, genetic, and imaging characteristics that can serve as a more accurate indicator of a disease or condition—makes it difficult to rapidly diagnose ALS and can confound drug development and clinical trials. In addition, the small population of individuals with ALS can make it challenging to test the safety and efficacy of drugs in clinical trials and also financially disincentivizes sponsors to develop therapies to treat ALS.[14] Thus, developing effective therapies for ALS has been difficult. As of September 2025, there were three FDA-approved therapies for ALS that moderately slow disease progression.[15]

Clinical Trials

When individuals are seeking access to investigational drugs, their first option is to consider whether they can obtain them through participation in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are a step in the drug development process through which a drug sponsor assesses the safety and efficacy—or effect—of its investigational drug through testing in humans. A clinical trial can take place in a variety of settings—such as research hospitals and clinics—and is led by a principal investigator who is typically a physician.

However, participating in clinical trials may be difficult for individuals with ALS due to the rapid progression of the disease and the length of time it typically takes to get an ALS diagnosis—anywhere from 10 to 16 months, on average. Meanwhile, clinical trials involving ALS investigational drugs typically have strict eligibility criteria—often within 18 months of symptom onset—that can create a narrow window for individuals with ALS to participate (see fig. 1).[16] In addition, traveling to the geographic locations where clinical trials are taking place can be difficult for individuals with ALS as these trials have generally been conducted in academic centers in urban areas.

Figure 1: Timeline of ALS Diagnosis and Disease Progression with Optimal Clinical Trial Participation

Notes: The rate of progression rate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and overall survival from the time of diagnosis varies. Some subtypes of ALS with more obvious symptoms are able to be diagnosed sooner, and about 10 to 20 percent of individuals with ALS survive longer than 10 years—particularly for those experiencing an onset of symptoms at a younger age.

To start a clinical trial, a sponsor must first submit an investigational new drug application to FDA for review. This application includes various components, including study protocols that define patient eligibility criteria, clinical procedures, and the drug and dosages to be studied.[17] In general, clinical trials that involve humans can begin after FDA has reviewed and allowed the investigational new drug application to proceed and after an institutional review board—which helps to ensure that humans are informed and protected during clinical trials—has granted approval.

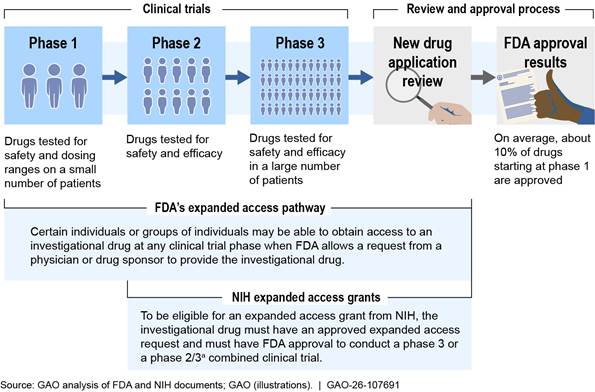

An investigational drug typically goes through three phases of clinical trials before a sponsor submits a marketing application to FDA for approval. In some cases when an investigational drug is being tested for a life-threatening condition, such as ALS, the drug development process may be expedited by going through only one or two phases of clinical trials before a marketing application is submitted to FDA for approval, according to FDA officials. The three clinical trial phases are the following.

· Phase 1 clinical trials. These generally examine the safety of the investigational drug in a small number of healthy volunteers. The goal of this phase is to determine the drug’s most frequent side effects and how it is metabolized and excreted. If the investigational drug does not show unacceptable toxicity in phase 1 clinical trials, it may move on to phase 2.

· Phase 2 clinical trials. These assess the safety and efficacy of the investigational drug on people who have a certain disease or condition. During this phase, some volunteers receive the investigational drug and are compared with others in a control group who are not receiving it, to see if the investigational drug works and is safe.[18] If there is evidence that the drug may be effective in phase 2 clinical trials, it may move on to phase 3.

· Phase 3 clinical trials. These collect more definitive evidence of the safety and efficacy of the investigational drug in a larger patient population and at different dosages, when being compared to a control group. Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials can also be designed as a combined trial, which can shorten the overall timeframe of the clinical trials, reduce the total number of individuals needed to participate, and may be helpful for rare diseases given the smaller patient population, according to NIH officials. If phase 3 clinical trials are successfully completed, the drug may move on to FDA’s process to review and approve the drug to be made available to the public.

FDA’s Expanded Access Pathway

Individuals with no comparable treatment options who are not able to participate in clinical trials may potentially gain access to an investigational drug through FDA’s expanded access pathway. The purpose of the expanded access pathway is different than that of clinical trials. Specifically, the expanded access pathway is intended to provide investigational drugs to individuals with serious or life-threatening diseases who have no other comparable treatment options, whereas clinical trials are intended to conduct research on investigational drugs as potential therapies for a disease. FDA’s goals for the expanded access pathway are to facilitate the availability of investigational drugs when appropriate, ensure safety, and preserve the clinical trial development process, according to FDA guidance.

Under FDA’s expanded access pathway, a licensed physician or drug sponsor can submit a request on behalf of an individual or group of individuals to gain access to an investigational drug for treatment outside of a clinical trial.[19] Requests are required to include information about the proposed clinical treatment plan, including safety monitoring procedures, and may be submitted during or after phase 1, 2, or 3 of a clinical trial (see fig. 2). To allow a request to proceed, FDA must determine that the individuals involved have a serious or immediately life-threatening disease or condition, have no other comparable medical options, and that allowing the request will not interfere with the clinical trials, among other criteria.[20] Drug sponsors must also agree to make their investigational drugs available. An institutional review board must also approve the clinical treatment plan and review the informed consent form.

Notes: This presents a simplified example of the process for individuals to access investigational drugs during the clinical trial period. For the purposes of this figure, an investigational drug is a drug or biologic used in a clinical trial that is not yet approved or licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for marketing, or is being tested in a clinical trial for an unapproved use or new patient population.

Other types of investigational products, such as medical devices and some biologics like vaccines, also go through a review process, and submit different applications to other centers within FDA.

According to National Institutes of Health (NIH) officials, for rare diseases, phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials are sometimes adapted by the drug sponsor into a single, combined phase 2/3 study design, which may address challenges such as the limited number of individuals with a particular rare disease. Additionally, for life-threatening conditions the drug development process may also be expedited by going through only one or two clinical trial phases before a marketing application is submitted to FDA for approval, according to FDA officials.

aThe Accessing Critical Therapies for ALS Act authorizes NIH to award grants to institutions, such as healthcare facilities or academic institutions, to both conduct research using data collected from individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and to provide those individuals with access to investigational drugs through FDA’s expanded access pathway, referred to as expanded access grants. The act specifies that eligible grant applicants must be participating clinical trial sites in a phase 3 clinical trial. However, according to NIH documents, NIH has included phase 2/3 combined trials in its definition of phase 3 clinical trials for the purpose of these grants, as clinical trial phases in combined trials are not always distinct.

The physician or drug sponsor submitting the expanded access request is also responsible for monitoring and reporting to FDA and the drug sponsor any adverse events that occur during treatment, including those for which there is a reasonable possibility that the drug caused the reaction and those that are not drug-related. Unlike clinical trials, no information about efficacy is required to be collected through expanded access programs, as the focus of these programs is on providing individuals with access to investigational drugs and ensuring their safety.

Cost and limited resources can often be barriers to participating in expanded access programs, including costs to drug sponsors, clinic sites and physicians, and individuals. For example, a drug sponsor’s capacity to manufacture an additional supply of the investigational drug may be limited, particularly for complex therapies. Additionally, the extra resources and physician time required for submitting an expanded access request to FDA and implementing the clinical treatment plan—including patient visits, drug administration, and safety monitoring, as well as other administrative tasks—may make participation cost-prohibitive for physicians or clinic sites.[21] Lastly, individuals may be prohibited from participating if treatment expenses are not covered by their insurance or if travel to the clinic site is needed, particularly if the clinic site is a long distance away.

NIH’s Expanded Access Grants

As authorized under the ACT for ALS Act, NIH awards expanded access grants to institutions to both conduct research on data collected from individuals with ALS and provide those individuals with access to investigational drugs through an expanded access program.[22] The lead researcher at the institution receiving the grant—known as the principal investigator—contracts with various other clinic sites to provide access to the investigational drugs and collect research data from individuals with ALS receiving that access. Specifically, the clinic sites screen and enroll participants to receive investigational drugs, administer the drug, implement study protocols, and collect biological samples and data from participants, among other things. Funds from the expanded access grants can be used to pay for a variety of expenses including paying the drug manufacturer or sponsor for the direct cost of the drug, the clinic sites for the costs of providing the investigational drug to participants, and the research institution and principal investigator for conducting the research and analyzing data.

The expanded access grants are subject to both FDA and NIH requirements. In order to receive an expanded access grant, applicants must first submit an expanded access request to FDA to allow access to the investigational drug. Applicants must also meet the grant eligibility requirements as defined by the act and NIH’s requirements for data and research quality, which are more typical of what is required for clinical trials.[23] NIH requires grant recipients to establish a data safety monitoring board—an independent group of experts—to review data quality and ensure the treatment and research plans are followed. NIH also requires grant recipients to have data management and statistical analysis plans describing how data will be collected and analyzed, and NIH may review and approve research and data plans and any proposed changes. Additionally, the grant applicants must describe how the data they collect will be used to support ALS research or development of therapies.

Most NIH and FDA Funding to Implement the ACT for ALS Act Supported ALS Research and Access to ALS Investigational Drugs

NIH and FDA awarded about $276 million to implement the ACT for ALS Act from fiscal years 2022 through 2025. Of those funds, NIH awarded about 45 percent for expanded access grants, NIH and FDA awarded about 45 percent for the public-private partnership, and FDA awarded about 10 percent for grants and contracts for research related to ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases.

NIH Funding for Research and Access to ALS Investigational Drugs

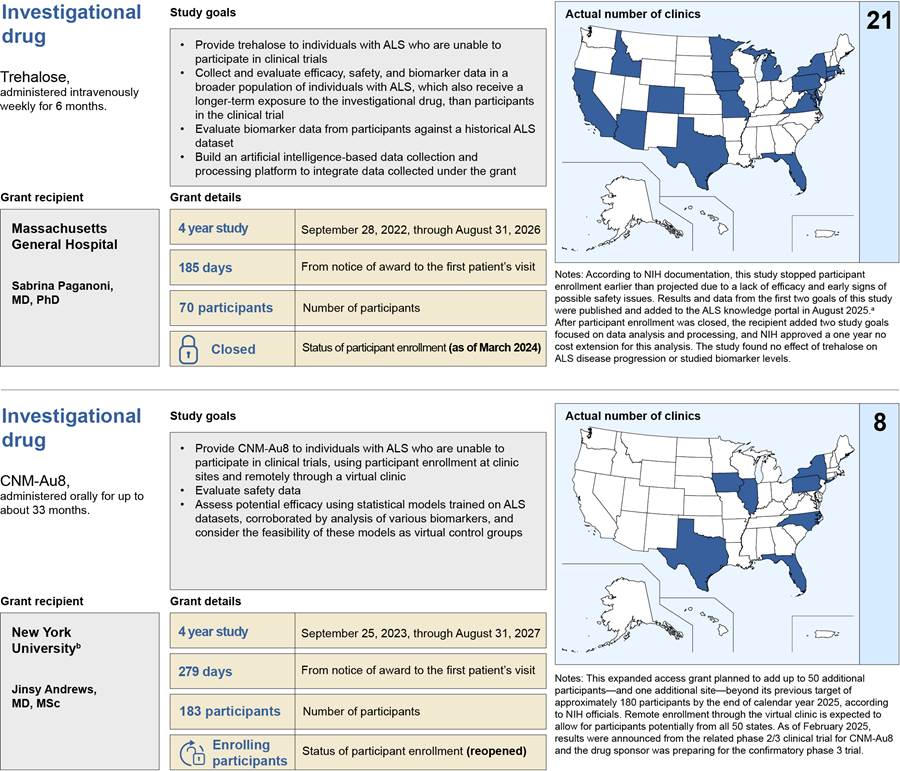

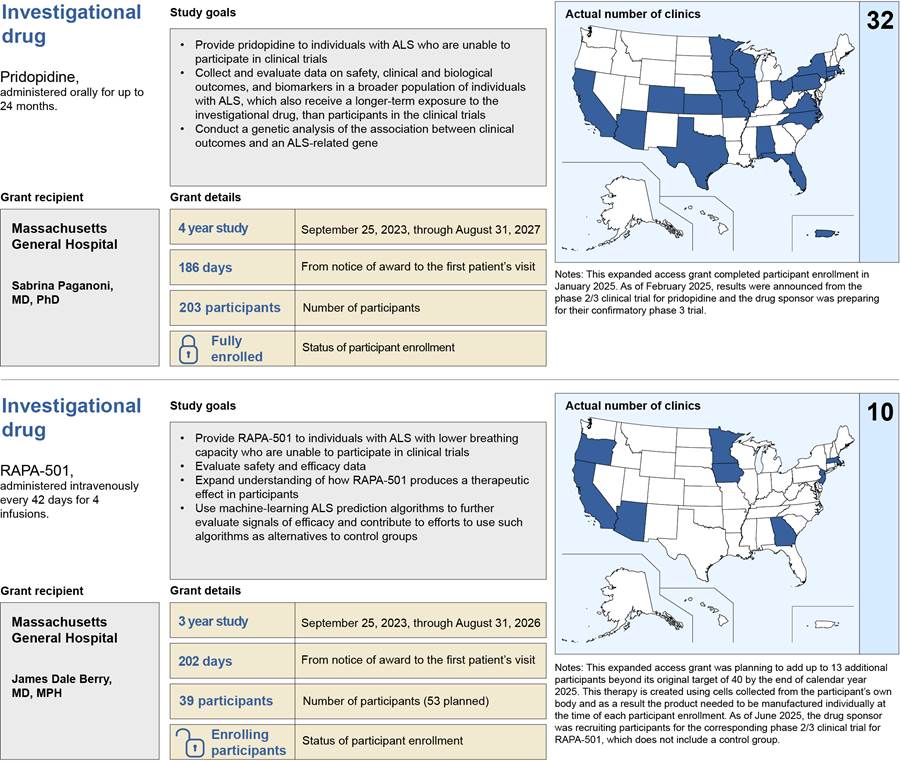

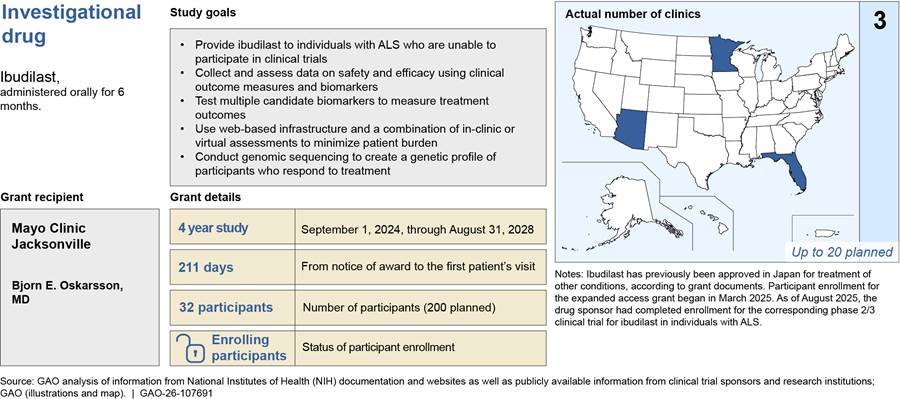

NIH awarded about $125 million through five expanded access grants to support research on and access to ALS investigational drugs from fiscal years 2022 through 2025, according to NIH documents (see table 1).

Table 1: Summary of Expanded Access Grants Awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Fiscal Years (FY) 2022 through 2025 (in millions), as of September 2025

|

ALS investigational drugs that are subjects of the expanded access grants |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

|

Trehalose |

$18.1a |

— |

— |

— |

|

CNM-Au8 |

— |

$11.2 |

$11.6 |

$11.6 |

|

Pridopidine |

— |

$10.1 |

$9.8 |

$7.9 |

|

RAPA-501 |

— |

$11.2 |

$11.7 |

$10.1 |

|

Ibudilast |

— |

— |

$6.1 |

$5.7 |

|

TOTAL |

$18.1 |

$32.5 |

$39.2 |

$35.4 |

Source: GAO analysis of information from NIH interviews, documents, and NIH RePORTER, as of September 2025. | GAO‑26‑107691

Notes: The Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act authorizes NIH to award grants, referred to as expanded access grants, until September 30, 2026. Expanded access grants are awarded to provide individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) access to investigational drugs outside of a clinical trial and to conduct research using data collected from participants. Grants awarded before this date will be allowed to continue until the project end date, according to NIH documentation. Funding for multi-year grant awards in future years will be contingent on future appropriations from Congress as well as the grant recipients’ successful demonstration of progress, continued evidence of safety, and other eligibility requirements. Totals may not add up due to rounding.

aNIH awarded the expanded access grant for trehalose in a lump sum, with the expectation that these funds would be spent over the course of 3 years. NIH later approved a 1-year, no-cost extension to allow for additional analysis to be conducted.

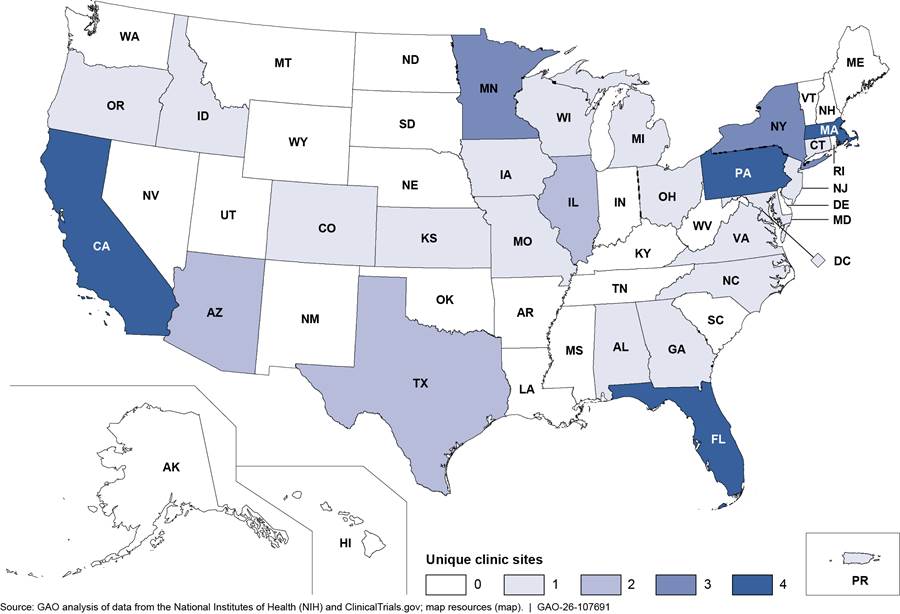

In total, approximately 750 individuals with ALS are expected to receive investigational drugs through the five expanded access grants that have been awarded from fiscal years 2022 through 2025.[24] Between 32 and 203 participants were enrolled for each expanded access grant at various clinic sites, as of August 2025. The average length of time from the notice that an expanded access grant was awarded to enrollment of the first participant was 213 days across all grants.[25] In total, 46 unique clinic sites were prepared to enroll participants across the United States for the five expanded access grants, as of August 2025.[26] This includes clinic sites in 25 states, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico, and a remote option with participants from all 50 states, according to grant documentation (see fig. 3).

Note: This map includes the 46 unique clinic sites that were prepared to enroll individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) for the five expanded access grants as of August 2025. A clinic site may have been included in more than one expanded access grant. Some of the clinic sites included in this figure may have been prepared to enroll participants but ultimately may not have enrolled anyone at their location. Expanded access grants were awarded by NIH to institutions to provide individuals with ALS access to investigational drugs outside of a clinical trial and to conduct research using data collected from participants.

One expanded access grant includes a virtual participation option, allowing individuals from all 50 states to enroll, according to grant documents. For the purpose of this map, we counted this virtual option as one clinic site based in Illinois, as it is documented in ClinicalTrials.gov.

In addition to research goals related to collecting and evaluating data on the safety and potential effects of the investigational drugs that are subjects of the expanded access grants, each grant recipient had additional research goals. Additional research goals described in the grant documentation for the awarded grants include the following.

· Using various methods, including using artificial intelligence, to predict participants’ expected disease progression so that it can be compared to the actual rate of progression measured while taking the investigational drug.

· Studying the association between genes and clinical outcomes—such as using gene sequencing to define the genetic profiles of individuals who respond better to the investigational drug.

· Exploring methods to improve participant recruitment and participation—such as fully remote participation through a virtual clinic and adapting clinical research infrastructure to allow for electronic consent and virtual evaluations.

As of August 2025, none of the investigational drugs involved in the expanded access grants had been approved for marketing by FDA to treat ALS. One investigational drug, trehalose, completed clinical trials in August 2023 and found no evidence of effect, according to ClinicalTrials.gov and published results.[27] As of August 2025, the other investigational drugs were in various stages of completing phase 2/3 combined trials, ongoing phase 3 trials, or planning subsequent phase 3 trials, according to ClinicalTrials.gov and publicly available documents from the drug sponsors.

See appendix I for more detailed information about the expanded access grants awarded by NIH.

NIH and FDA Funding for Research Coordination Through the Public-Private Partnership

NIH and FDA awarded about $124 million to the public-private partnership for coordination on rare neurodegenerative disease research from fiscal years 2022 through 2025. According to agency officials, the amount of funding planned to be awarded for fiscal years 2026 through 2027 is dependent upon appropriations.

|

Public-Private Partnership Entities Access for All in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Consortium (ALS Consortium), established in 2023, is run jointly by two clinical coordinating centers: Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (East—with about 15 clinical sites) and Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix (West—with about 19 clinical sites). The National Institutes of Health and members (including patient advisory committees) play a role. Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Accelerating Medicines Partnership) was launched in May 2024 as a 5-year project under the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, a non-profit entity established by Congress in 1990 and that convenes public private partnerships between NIH, academia, industry, and patient advocacy groups. The Critical Path for Rare Neurodegenerative Diseases, established in September 2022, is managed by the Critical Path Institute (Critical Path), a non-profit entity that has previously worked with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on other public-private partnerships. Members (including patient advisory committees and industry) also provide input. Source: GAO analysis of information from stakeholder groups and agency documents. | GAO‑26‑107691 |

The public-private partnership includes components led by three separate entities that have separate but interrelated goals, which they coordinate to implement. For example, each entity provides early input on the other entities’ goals and shares data and information across efforts. NIH and FDA awarded funds separately to each component and most of the funding has been focused on ALS. The goals of each of the three public-private partnership entities are provided below.

· Access for All in ALS Consortium (ALS Consortium). This entity’s goal is to establish the infrastructure needed to collect a wide range of data and biological samples via two large natural history studies, including from individuals with ALS, individuals at genetic risk for ALS who have not developed the disease, and control groups.[28] To encourage a more inclusive population of participants, the studies include an option for remote enrollment and monitoring. NIH awarded the ALS Consortium $36.4 million in fiscal year 2023, $30.1 million in fiscal year 2024, and $34.6 million in fiscal year 2025 to conduct the natural history studies. As of November 2025, 1,123 participants were enrolled in the two large natural history studies at 33 research sites in 25 states, Washington, D.C.; and Puerto Rico.

· Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Accelerating Medicines Partnership).[29] This entity’s goal is to establish a comprehensive strategy to expedite the development of effective new ALS therapies. Accelerating Medicines Partnership seeks to achieve this through several activities, including 1) establishing and managing the ALS knowledge portal, which became publicly available in August 2025;[30] and 2) molecular analyses of biological samples and clinical research—from the ALS Consortium and other research—to support early diagnosis and treatment assessment, such as by identifying and validating new biomarkers. Most direct funding for Accelerating Medicines Partnership is expected to come from the private sector through the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. As of August 2025, officials with Accelerating Medicines Partnership told us that $20.9 million had been raised from the private sector to support the goals of this entity. In addition, $6.1 million of the grant funding NIH awarded to the ALS Consortium from fiscal years 2023 through 2025 will be used to support functions in the ALS knowledge portal, according to NIH officials.

· Critical Path for Rare Neurodegenerative Diseases (Critical Path). This entity’s goal is to identify gaps and tools to help therapies for ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases receive FDA regulatory approval, according to documents and stakeholders. For example, Critical Path is conducting an analysis of current ALS clinical outcome assessments—measures that providers use to describe or reflect how an individual with ALS feels, functions, or survives—to determine gaps and recommendations for improvement. Additionally, Critical Path is curating existing ALS datasets to be added to the knowledge portal.[31] NIH awarded Critical Path $4 million in fiscal year 2022, $5 million in fiscal year 2023, $4 million in fiscal year 2024, and $2.3 million in fiscal year 2025.[32] FDA officials told us they awarded Critical Path $1.5 million in fiscal year 2022, $0.9 million in fiscal year 2023, $1.9 million in fiscal year 2024, and $2.8 million in fiscal year 2025.

FDA Funding for Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Research Priorities

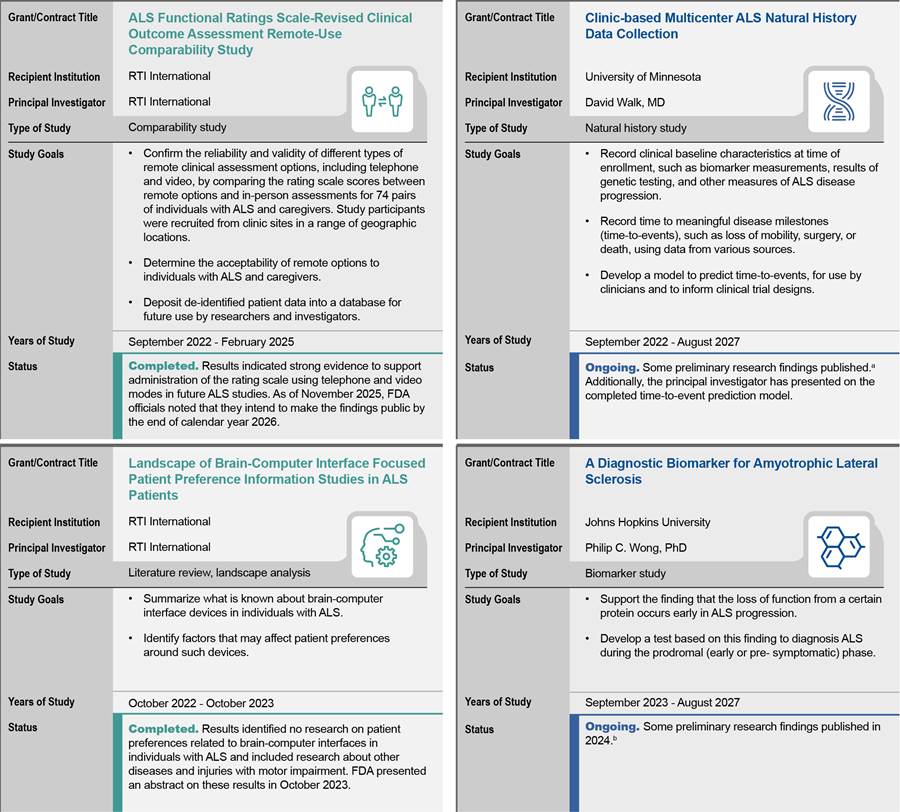

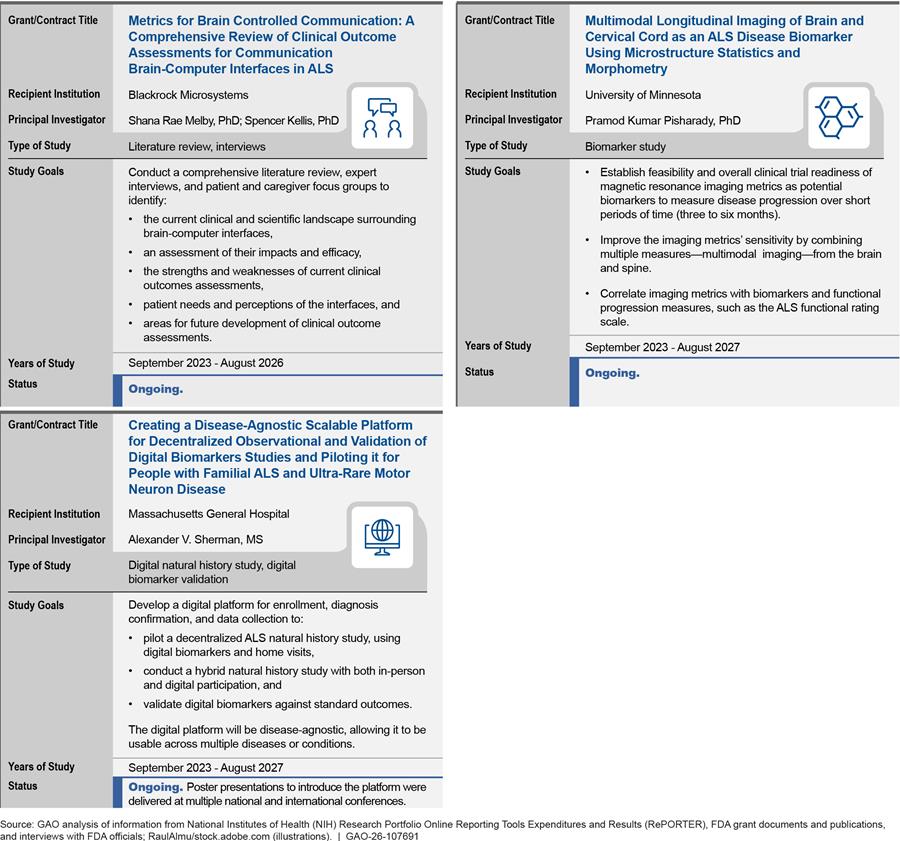

FDA awarded $27 million for rare neurodegenerative disease research to institutions under its Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program from fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2025.

To determine what types of studies to award funding under the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program, FDA conducted a gap analysis in February 2022 to identify the areas of largest need.[33] FDA’s analysis identified four priority areas.

· Comparability studies for the development and adaptation of clinical outcome assessments that can be used remotely to decrease travel burden for patients and their caregivers and increase clinical trial efficiencies.

· Natural history studies, especially with predefined genetic subsets providing subjects have consented.

· Tools to enhance development and regulatory review of devices with brain-computer interfaces, which are devices that can be implanted or attached on the surface of the head that communicate with the brain and transmit signals to restore lost motor and sensory capabilities as well as communication.

· In vitro diagnostic tests, which are tests conducted in a laboratory setting versus in the body of a patient. These can include tests to identify biomarkers. For example, while some biomarkers can be used to diagnose or monitor a disease, others can be used to measure or predict the effect of a treatment.

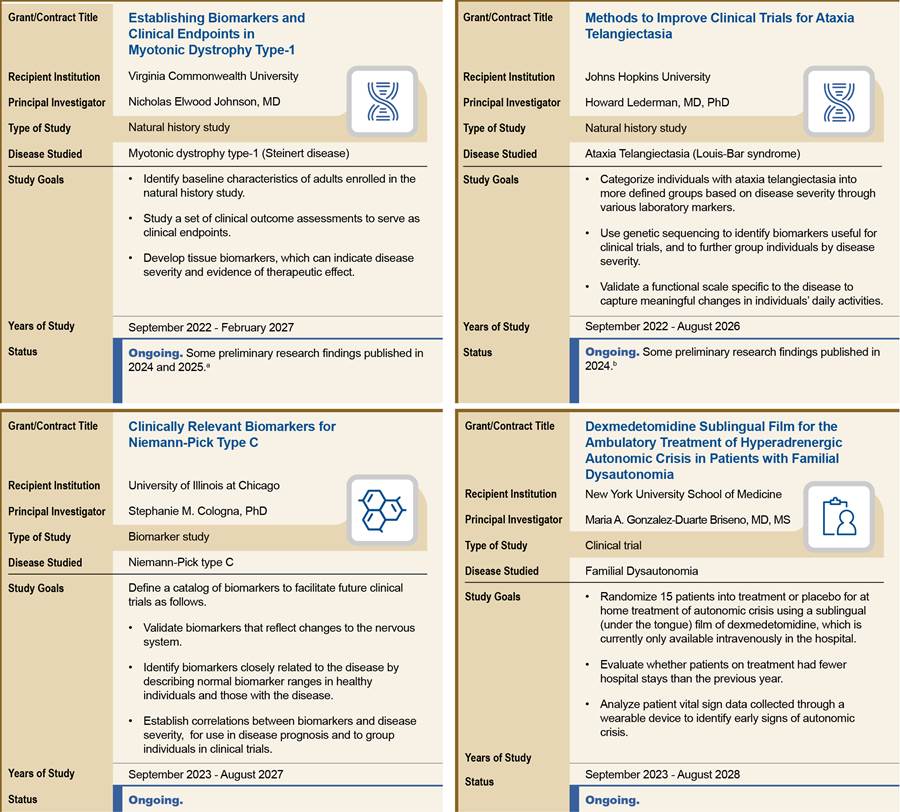

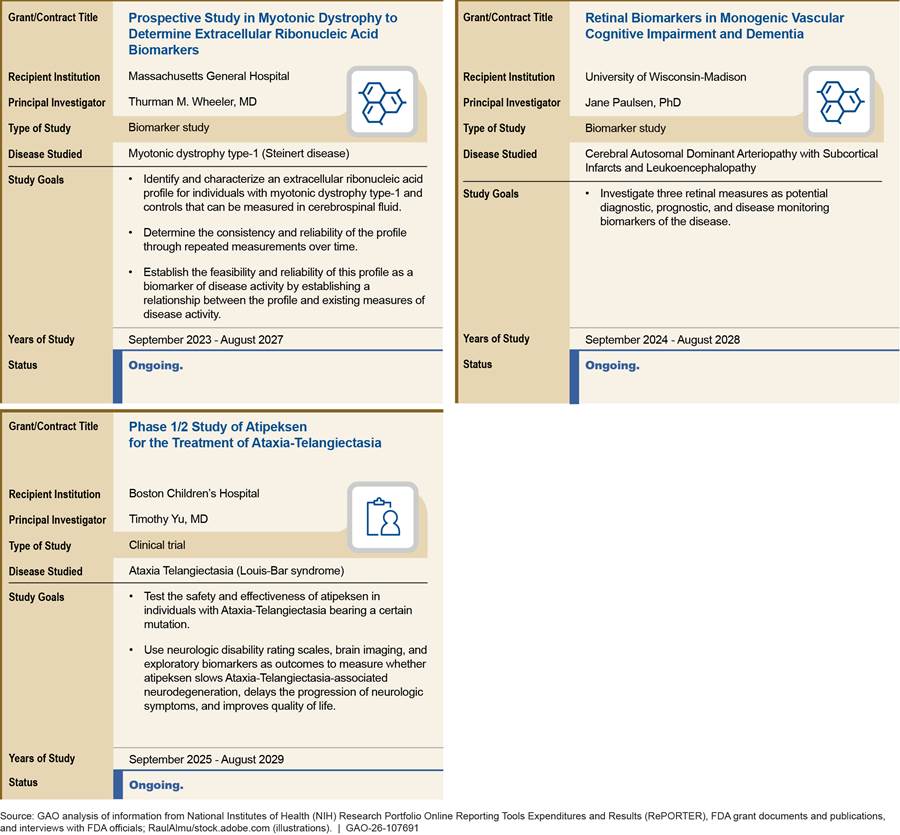

The grants and contracts awarded by FDA under the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program were for studies that generally aligned with the four priority areas identified in FDA’s gap analysis, according to our analysis. In total, FDA awarded 12 grants and two contracts under the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program from fiscal year 2022 through 2025 for research for ALS and five other rare neurodegenerative diseases (see table 2). Most grants were awarded for a 4-year grant period.

Table 2: Summary of Grants and Contracts Awarded by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from Fiscal Years (FY) 2022 through 2025 (in millions), as of December 2025

|

Type of Study & Rare Neurodegenerative Disease |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

|

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Functional Scale-Revised Clinical Outcome Assessment Remote Comparability Study – ALS |

$1.9 |

$0 |

$0.2 |

— |

|

Landscape Analysis of Brain-Computer Interface – ALS |

$0.3 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Natural history – ALS |

$1.6 |

$1.4 |

$1.5 |

$3.0 |

|

Natural history – Ataxia-telangiectasia |

$1.6 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Natural history – Myotonic dystrophy type-1 |

$0.4 |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

|

Biomarker – ALS |

— |

$1.6 |

— |

— |

|

Biomarker – ALS |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

|

Biomarker and natural history – Familial ALS and ultra-rare neuron diseases |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

|

Biomarker – Myotonic dystrophy |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

|

Biomarker – Niemann-Pick type C |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

$0.4 |

|

Literature review and Interviews for Brain-computer interfaces – ALS |

— |

$0.2 |

$0.3 |

— |

|

Clinical trial – Familial Dysautonomiaa |

— |

$0.4 |

$0.3 |

$0.4 |

|

Biomarker – Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) |

— |

— |

$1.3 |

$1.2 |

|

Clinical trial – Ataxia-telangiectasia |

— |

— |

— |

$3.6 |

|

TOTAL |

$5.8 |

$5.1 |

$5.5 |

$10.1 |

Source: GAO analysis of FDA interviews and documents, as of December 2025. | GAO‑26‑107691

Notes: The Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act authorizes FDA to award grants and contracts through the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program, through September 30, 2026. Grants awarded before this date will be allowed to continue until the project end date, according to FDA documentation. Totals may not add up due to rounding. Totals include $1.7 million from NIH and additional funding from another FDA grant program in fiscal year 2022. Funding for multi-year grant awards in future years will be contingent on future appropriations from Congress, among other things.

A clinical outcome assessment is a measure used to assess the impact of treatments or interventions on patients, generally made by a provider or clinician. Brain-computer interfaces are devices that can be implanted or attached on the surface of the head that communicate with the brain and transmit signals to restore lost motor and sensory capabilities as well as communication. Natural history studies are a type of observational study that track the course of a disease over time. Biomarkers—biological molecules in blood or tissue that are a sign of the disease or condition—help researchers understand disease risk factors.

aThis grant was co-funded with another FDA grant program, including $78,435 in fiscal year 2023. The ongoing clinical trial this grant supports is testing a new formulation of a previously FDA-approved drug.

See appendix II for more detailed information about the grants and contracts FDA awarded through the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program.

NIH and FDA Identified Challenges Stemming from Funding Timing and Requirements and Took Actions to Address Challenges Within Their Control

NIH and FDA identified some challenges to implementing the ACT for ALS Act, particularly during the initial year after the act’s enactment in fiscal year 2022. Both agencies took actions within their control to address challenges in that initial year and to prevent issues in subsequent years. However, NIH and FDA officials stated that other aspects of these challenges are outside the agencies’ control.

Shortened Timeframes for Agencies to Award Funding

According to agency officials, shortened timeframes, particularly in fiscal year 2022, made it difficult for both NIH and FDA to award funding using the agencies’ standard timeframes and processes.

NIH. NIH stated that it did not have enough time in fiscal year 2022 to award grant funding using its standard timeframes and processes because of the timing of appropriations to implement the ACT for ALS Act. This contributed to expired appropriations that year, according to agency officials.

· The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022, was enacted on March 15, 2022, and NIH published the request for grant applications May 12, 2022. The time between NIH publishing the request for grant applications and the application deadline was 36 days in fiscal year 2022, about one-third the length of the application period for fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

· The shorter timeframe in fiscal year 2022 may have contributed to the small number of applicants, NIH officials said. That year, NIH received only one application that ultimately met requirements for funding and awarded 3 years’ funding to the recipient in that 1 year as a result, according to NIH officials.[34]

· NIH officials also reported that $1.16 million of fiscal year 2022 funds expired because the agency was unable to award them in time, due in part to the timing of appropriations.

NIH officials said the agency has taken several steps to help address this challenge if it arises in the future and to help ensure that the agency is able to use all appropriations it receives. However, NIH officials said it is important to note that the agency has no control over the timing of appropriations.

· NIH officials noted they now publish the request for applications each year prior to receiving appropriations. This ensures sufficient time for applicants to prepare applications and NIH to review applications and make awards before the end of the fiscal year.

· NIH officials noted that the agency has prepared for the possibility that it may not receive enough expanded access grant applications that meet grant eligibility and review requirements for the agency to use all appropriated funds each year.[35] In these cases, the agency determined that it may apply remaining appropriations to the public-private partnership.[36]

In addition to steps taken by NIH, in fiscal years 2023 and 2024, explanatory statements accompanying NIH’s appropriations stated that any appropriations remaining after NIH has awarded the expanded access grants may be used to fund the public-private partnership.[37]

FDA. For the reasons explained above, FDA also did not have enough time in fiscal year 2022 to use its standard grant process to award funding to implement the ACT for ALS Act, according to agency officials. To address this, FDA selected grant recipients from a pool of eligible applicants for an existing request for applications under a different grant program for studies of rare diseases.[38] FDA officials said that using the existing applicant pool and grant review panel was more efficient than beginning a new full grant cycle that year. During subsequent years, FDA officials said they were able to write and post new requests for applications specifically for the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program.

In addition, FDA officials said they used an existing blanket purchase agreement to award two contracts for rare neurodegenerative disease research during fiscal year 2022 because of the shortened time frames. According to officials, this type of agreement allowed the agency to efficiently identify and select contract recipients from among vetted, pre-approved entities interested in performing defined research.[39]

Availability of Appropriations for FDA to Implement the Act

FDA officials noted several challenges with the availability of appropriations for the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program and took steps to address each one.

· No funding was directly appropriated to FDA for the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program in fiscal year 2022, according to HHS budget documents and FDA officials. Instead, FDA officials said they were directed by a letter from Congress to use a $2.5 million increase in agency funding for another grant program related to rare diseases to fund grants under the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program for fiscal year 2022. Additionally, according to FDA officials, NIH transferred funds initially appropriated to that agency to FDA to fund grants under the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program for fiscal year 2022.

· FDA received appropriations for the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program starting in fiscal year 2023. However, agency officials said the appropriations did not include funds for staff, infrastructure, and administrative costs to operate the program. FDA officials told us they absorbed the additional work for the FDA Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program by using existing staff assigned to administer the Orphan Products Grants Program.[40] They noted it was challenging for agency staff to administer a new grant program without infrastructure funds and an already heavy workload.

FDA was also not directly appropriated funds to support the public-private partnership from fiscal years 2022 through 2025, according to FDA officials. To address this, FDA reprioritized some funds from their existing budget and received transferred funds from NIH to support FDA’s contribution to the partnership, according to agency officials. FDA officials said that NIH funds initially made up about 80 percent of the annual funding the agencies have contributed to the Critical Path’s efforts under the partnership, but FDA has worked to increase the agency’s contribution. During fiscal year 2025, FDA’s contribution to Critical Path’s partnership efforts was nearly equal to that of NIH.

The lack of direct funding for FDA, and reliance on NIH funds to support the partnership has limited FDA’s ability to direct the Critical Path to pursue broader rare neurodegenerative disease priorities beyond ALS, officials told us. FDA officials also said that the use of appropriations transferred from NIH are limited to ALS-related activities. FDA officials stated that the agency has communicated with Congress about the need for the agency to receive funding directly to contribute to the partnership and meet the requirements of the ACT for ALS Act.

Eligibility Requirements for Expanded Access Grants

NIH has faced some challenges awarding grants because of the eligibility requirements for grant applicants, according to NIH officials.

· To be eligible for expanded access grants, the ACT for ALS Act requires that the investigational drug under study be in a phase 3 clinical trial.[41] NIH has considered this requirement to include both phase 2/3 combined trials and planned phase 3 clinical trials that are not yet enrolling participants, because clinical trial phasing is not always distinct, according to agency documentation. Agency officials stated that without using their interpretation of the phase 3 clinical trial requirement, NIH would not have had eligible applications to fund each year.[42]

· The act also requires the sponsors of the investigational drugs included in the expanded access grants to be U.S.-based small businesses, which agency officials said also limits the number of eligible applicants.

· Because of these eligibility requirements, the pool of potential candidates for the grants is limited, NIH officials said, and the agency receives a small number of applications each fiscal year. Officials also said that it is possible that the small number of potentially eligible entities could result in NIH receiving no applications for the grants in the future.[43]

To help address this challenge, NIH officials said that the agency has conducted extensive efforts to ensure all eligible and interested entities know about and have the opportunity to apply for expanded access grants. These outreach efforts included market research to identify potential candidates, outreach to potentially eligible entities, and webinars available on demand to answer questions about applying for the expanded access grants. Officials said they hope the continued availability of funding for the expanded access grants will promote further interest and encourage drug sponsors to move potential therapies through the clinical trial process to become eligible.

Review Requirements for Expanded Access Grant Applications

Current review requirements for initial funding of the expanded access grants under the ACT for ALS Act do not include a requirement that NIH assess the potential efficacy of the investigational drug, according to NIH officials.[44] Agency officials said this could result in continued funding for—and participant exposure to—investigational drugs that may not be effective or that are not moving towards FDA approval if a grant recipient were to apply for a grant renewal in future funding cycles.

NIH officials are taking steps to address this concern.

· According to NIH officials, the agency plans to evaluate applicants seeking renewed funding for expanded access grants in future, multi-year funding cycles for progress made in the last funding period. Progress could include progress toward the goal of FDA approval, according to NIH officials.

· They added that the request for applications for fiscal year 2026 will specify whether evaluation of renewal applications will include a review of progress in clinical trials intended to support FDA approval of the investigational drug.

Stakeholders and Literature Indicated Potential Benefits of NIH and FDA Funding for Ongoing Research and ALS Investigational Drugs

It is too early to assess the full effects of the funding awarded by NIH and FDA to implement the ACT for ALS Act, as most of the research is still underway. Accordingly, our literature search identified only a small number of articles describing the effects or potential effects of the funding. Most of the 21 stakeholders we interviewed identified current or anticipated benefits of the funding awarded by NIH for the expanded access grants, by NIH and FDA to support the public-private partnership, and by FDA for research on ALS and other rare neurodegenerative diseases.

Current and Potential Benefits of NIH Funding for Research and Access to ALS Investigational Drugs

|

Four Clinic Sites’ Experiences of NIH Grants We interviewed representatives from four clinic sites that provided investigational drugs to individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) through one or more grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) about their experiences under the grants. These included the following. · Representatives from all four clinic sites valued having an option for an investigational drug to offer individuals with ALS who were not able to participate in clinical trials. · No representatives saw their clinic’s participation in the NIH grants as overly burdensome, and three stated it was similar to what the clinic sites were doing to participate in clinical research. Three of the clinic sites already had the staff to participate in clinical research, and one added staff to participate in the NIH grants. · Representatives from all sites noted the value of the level of funding from the NIH grants, and two clinic sites stated that funding was important to their ability to participate. · Representatives from three clinic sites noted they had invested resources to participate in one of the NIH grants but were not able to provide investigational drugs to any individuals with ALS under that grant because enrollment slots had filled up at other clinic sites first. Source: GAO analysis of interviews with clinic sites. | GAO‑26‑107691 |

As of November 2025, recipients of all five of the NIH expanded access grants were still conducting research or data analysis related to investigational drugs provided to individuals with ALS, according to NIH documents and officials. As such, findings were not yet available to examine for potential effects for all of the expanded access grants. Our literature search identified one article describing the known effects of the funding for expanded access grants that was published in August 2025. As a result, we describe the current and anticipated benefits identified by many of the stakeholders we interviewed and our analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov data, supplemented by articles on expanded access programs not funded by the expanded access grants and the one article describing the results from the first expanded access grant.[45] These benefits are as follows.

Increased number and geographic diversity of clinic sites providing access to investigational drugs. Several stakeholders stated the expanded access grants have increased the number and geographic diversity of clinic sites where individuals with ALS could receive access to an investigational drug. Additional clinic sites, including in places which did not previously have clinic sites for ALS research, may allow for greater geographic diversity in the individuals with ALS who are able to access investigational drugs. Prior to the expanded access grants, expanded access programs were generally limited to a few clinic sites, according to some stakeholders. In contrast, stakeholders noted each expanded access grant has multiple sites, including clinic sites in geographic areas that previously had limited or no access to investigational products or expanded access programs.

Our analysis of the literature and data on expanded access programs in ClinicalTrials.gov supports stakeholder comments that the expanded access grants have likely increased the number of sites and the geographic diversity of where individuals with ALS can receive access to investigational drugs.[46] For example, data from ClinicalTrials.gov and literature on expanded access programs show that the expanded access grants have added clinic sites in less populated states, such as Idaho and Iowa, which otherwise would not have any clinic sites participating in expanded access programs. Additionally, the August 2025 article for the trehalose expanded access grant stated that clinic sites expressed much higher interest in participating in the expanded access grant than with previous expanded access programs offered to a similar group of clinic sites.[47]

Some stakeholders also stated that more clinic sites are ready to participate in ALS clinical research as a result of the expanded access grants. This may in turn further increase access in the future to investigational drugs for individuals with ALS. For example, some stakeholders noted that participating in an expanded access grant could increase the chance of that clinic site being selected by a drug sponsor as a clinical trial location in the future.

Increased number of individuals receiving access to investigational drugs. Several stakeholders we spoke with stated that the expanded access grants have increased the number of individuals with ALS who have access to investigational drugs. For example, some stakeholders noted that prior to the ACT for ALS Act, expanded access programs were generally small, with a few dozen participants in each expanded access program. In contrast, stakeholders pointed to the hundreds of individuals

|

Stakeholder Perspectives on Priorities for ALS Research Funding Stakeholders we interviewed differed on the right balance of priorities for grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as directed by the Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies for ALS Act. The NIH grants fund access to investigational drugs for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) who are not able to participate in clinical trials and research using collected data. · Some stakeholders felt NIH’s research and data quality requirements for the grants slowed enrollment, limited participant slots, and increased costs. They emphasized the unmet need in the ALS community for access to investigational drugs. · Several other stakeholders felt that such requirements were needed to meet the act’s goals and highlighted the benefits of collecting quality data. Additionally, some noted that the grants enrolled faster than clinical trials typically do. However, they acknowledged that the need for the requirements and the time it takes to properly implement them could be better communicated to the ALS community. In addition, some stakeholders identified other research priorities they felt could have a greater effect on developing potential therapies for ALS than the NIH grants. · These priorities included more funding for biomarker research, staffing at ALS clinics, research into the causes of the disease, and infrastructure for data collection, among others. · Investing in these priorities could lead to more therapies starting clinical trials and more eligible applicants for the NIH grants, according to some stakeholders. Source: GAO analysis of interviews with 21 stakeholders, including patient advocacy organizations, NIH grant recipients, and others. | GAO‑26‑107691 |

who have enrolled or are expected to enroll under the five expanded access grants. Several stakeholders stated that individuals with ALS benefit from participating in expanded access programs beyond any direct clinical outcomes because it gives them hope, the opportunity to contribute to research, and can strengthen their connection to clinical care. However, some stakeholders and the literature also noted the importance of clearly communicating to participants that these investigational drugs are not yet approved and may not be effective treatments to avoid creating false hope and manage expectations.[48]

Our analysis of data on expanded access programs in ClinicalTrials.gov and the literature supports stakeholder statements that the expanded access grants likely increased the number of individuals with ALS receiving access to investigational drugs through an expanded access program. However, the data were not sufficiently complete to determine the extent of the increase.[49]

In addition, several stakeholders noted that the expanded access grants have increased the diversity of individuals with ALS receiving access to investigational drugs, in part due to remote options and additional clinic sites in some states. For example, one stakeholder noted that clinic sites and individuals with ALS on the West Coast typically do not have access to investigational drugs until later stages of clinical trials, whereas the expanded access grants allowed earlier access to West Coast clinic sites. However, several stakeholders felt that variation in enrollment practices across individual clinic sites meant that getting enrolled in an expanded access grant could be a matter of personal connections or where an individual receives clinical care. For example, some clinic sites enrolled individuals on a first-come, first-served basis, while others may have used a lottery approach to select who to enroll, according to some stakeholders.

Additional data collected. Many stakeholders expected the data resulting from the expanded access grants to benefit ALS research and contribute to a broader understanding of the disease. This is because the data are required to meet higher data quality standards similar to those used in clinical trials and are collected from individuals with ALS typically excluded from clinical trials.[50] Furthermore, having these data available in the ALS knowledge portal being developed by the public-private partnership would contribute to researchers’ understanding of ALS, according to some stakeholders. Data from the first expanded access grant were added to the ALS knowledge portal created by the public-private partnership in August 2025, according to NIH officials, and became accessible online in September 2025. The published results from this first expanded access grant found no effect from the investigational drug (trehalose) on ALS disease progression or certain biomarker levels. However, the authors discuss their analysis of various data and biological samples collected as a part of the grant-funded research, which have been shared with other researchers for additional biomarker analysis and added to a larger ALS dataset.[51]

Additionally, several stakeholders anticipated that data collected under the expanded access grants could support the drug sponsor’s marketing application to FDA for approval of the investigational drug, while some other stakeholders were unsure if it could be used for this purpose. FDA officials stated that safety data from a well-conducted expanded access program may be used to support a marketing application. However, it is difficult to draw conclusions about efficacy from data from expanded access programs because they typically include a sicker and more diverse participation population, making treatment response hard to measure. Moreover, they lack control groups for comparison. FDA officials further stated it is rare for the agency to use data that is not from a clinical trial to inform its approval decisions.

Piloted innovative approaches. According to some stakeholders, grant documents, and NIH officials, the innovative approaches being piloted in the expanded access grants could help improve how future clinical trials are conducted. For example, one grant has an option for individuals to participate remotely through a virtual clinic site, in addition to in-person enrollment and participation at other clinic sites. Some stakeholders and the literature described how allowing remote participation could reduce the burden that traveling to participate in clinical trials or research places on individuals with ALS and their caregivers.[52] In addition, an artificial intelligence prediction tool being used by another grant could help replace control groups in clinical trials where having a control group who is not receiving the investigational drug is difficult, according to the grant documentation and the literature.[53]

However, some stakeholders also acknowledged that introducing new tools or approaches into clinical trials can be difficult, even when they have been piloted in other research. For example, one stakeholder noted that clinical assessments, new biomarkers, or other research tools may require additional validation or analysis to be considered fit-for-use for clinical trials in keeping with FDA’s guidance. This stakeholder further noted the need to fund FDA’s review and approval of such clinical research tools, and to hold the agency to completing such reviews in a timely manner, to allow drug sponsors to conduct more efficient clinical trials.

Current and Potential Benefits of NIH and FDA Funding for Research Coordination Through the Public-Private Partnership

Some stakeholders described how the public-private partnership, funded in part by NIH and FDA as required by the ACT for ALS Act, has increased coordination between the agencies and rare neurodegenerative disease research organizations since it began its work in 2022.[54] Several stakeholders also stated that the partnership is anticipated to advance ALS research as it continues to centralize ALS research data and conduct large-scale natural history studies, which could also lead to a better understanding of ALS, according to the literature we reviewed.

Increased coordination. The public-private partnership increased coordination and communication between NIH and FDA as well as between ALS and rare neurodegenerative disease stakeholders, according to agency officials and some stakeholders. For example, FDA and NIH officials stated that they meet monthly or more frequently if needed to discuss partnership activities.[55] The three partnership entities also described frequent communication and feedback between each other, the agencies, industry partners, and the ALS community on the design of partnership projects. However, some stakeholders also noted the need for the partnership and the ALS research community to better communicate with the rest of the rare neurodegenerative disease community. Much of the partnership’s work to date has focused on ALS and not other rare neurodegenerative diseases, as intended.

Centralized data. The ALS knowledge portal is expected to bring together data from the partnership’s natural history studies, the expanded access grants, and other existing ALS data sets and make them accessible to researchers, according to several stakeholders and NIH documents. Several stakeholders noted that having data in a central repository will promote open science and public access and could lead to important discoveries about ALS.[56] Similarly, literature we reviewed noted the need for centralized data repositories for ALS. For example, the National Academies report stated that the current fragmented state of ALS data collection raises the costs for individual projects and limits their ability to test multiple research theories.[57] As of September 2025, 16 datasets were listed in the ALS knowledge portal, with clinical or genetic data from various ALS research efforts.

Large ALS natural history studies. Some stakeholders and the literature we reviewed noted how data and biological samples from large-scale, natural history studies, such as the two conducted by the public-private partnership, could lead to a better understanding of ALS and the identification of new therapeutic targets.[58] One stakeholder added that certain questions—such as those about genetic profiles and risks, the different patterns of disease progression, and what biomarkers exist during the course of the disease—can only be answered with a larger sample size. Additionally, that stakeholder noted that the ALS Consortium relies on continued funding from NIH to allow these natural history studies to be conducted over the long term. The stakeholder added that, prior to the funding related to ACT for ALS Act, ALS research was often subject to interruptions due to lack of funds.

Some stakeholders also anticipated that these large studies could reduce the burden of participating in clinical trials for future research participants. For example, according to the National Academies report, data from a well-designed natural history study could be used as a control group in clinical trials and thus reduce the need for individuals with ALS to serve in control groups.[59] However, the National Academies report also notes that such natural history control groups are effective when the natural history of the disease is well defined, which is not yet the case for ALS.

Lastly, the large size of the studies conducted by the partnership will also allow the researchers to test the effectiveness of remote sample collection and several remote outcome measures, according to some stakeholders. This could eventually become standard for ALS clinical research if the studies show they are successful measures. Some stakeholders and the literature highlighted the remote options as particularly important for reducing the burden on individuals with ALS and enrolling a more inclusive population than prior ALS studies.[60]

Current and Potential Benefits of FDA Funding for Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Research Priorities

Of the research funded through FDA’s Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program from fiscal years 2022 through 2024, two contracted studies had been completed, and 11 research grants were still ongoing.[61] Agency documents, interviews of stakeholders and agency officials, and the literature we identified described the potential value of the research, including the following.

FDA expects to use findings from two contracted studies. FDA officials reported that they expect to use the results from the two completed research studies to inform ALS clinical trials and future research.

· One contracted study looked at the revised ALS functional scale—a common clinical outcome assessment for ALS—and found that remote telephone or video assessments of individuals with ALS were comparable to in-person assessments.[62] FDA officials stated that the agency expects to use this finding to advise ALS drug sponsors on clinical trial designs and will accept clinical trial data collected using such remote assessments as valid. FDA officials told us they may also use the study protocols as a model for similar comparability studies for outcome measures in other diseases. Some stakeholders pointed to FDA awarding funds for this study as an important step in improving ALS research and clinical trials. FDA officials stated they plan to publish the report from this study on FDA’s website by the end of 2026, along with the study protocols. The study data is already available to other researchers through the Rare Disease Cure Accelerator – Data and Analytics Platform run by the Critical Path Institute, according to FDA officials.

· Another contracted study reviewed the existing literature on ALS patient preferences regarding brain-computer interfaces, which FDA had identified as a priority area for the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program.[63] The literature review found no patient preference studies specifically addressing brain-computer interfaces in individuals with ALS but identified four studies on related topics that could inform the future development of such patient preference studies for ALS. If FDA uses this review to design an FDA study, it could inform FDA’s future regulatory review of new devices, according to contract and FDA documents and FDA officials.

Preliminary findings indicate progress on research goals. The principal investigators on four FDA Rare Neurodegenerative Disease grants have published preliminary research findings that indicate progress towards their grants’ goals, according to our analysis of the literature. For example, one grant’s research goal is to develop a biomarker test, which would allow for earlier ALS diagnosis. The principal investigator on this grant has published preliminary findings indicating that the biomarker they are studying occurs before clinical symptoms are evident.[64]

Grant goals target research gaps. Nine of the 11 grants awarded by FDA from fiscal years 2022 through 2024 are focused on disease natural history or biomarker research, areas where stakeholders and the literature have identified the need for, and potential effect of, additional research, such as the following.

· Some stakeholders described the importance of understanding the natural history and genetic factors of ALS and some commented on the need for better biomarkers or clinical outcome measures related to ALS. Four of the grants awarded by FDA focus on biomarkers or natural history studies for ALS. According to the National Academies report, understanding the complex variety of ways ALS manifests and addressing the lack of biomarkers could improve ALS diagnosis and accelerate the development of new therapies.[65]

· We also previously reported that the natural history of rare diseases in general is often poorly understood, which makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials or determine meaningful outcome measures.[66] Six of the grants focus on natural history or biomarkers for rare neurodegenerative diseases other than ALS.

· Grant documentation for all nine of these grants describes how achieving their planned natural history or biomarker research goals could inform or improve future clinical trials of potential therapies, though these grants are not directly developing potential therapies or alternative clinical trial designs. For example, multiple grants aim to help better identify and categorize clinical trial participants by disease type or severity, which in turn may help improve future clinical trial efficiency.

Some stakeholders also stated that the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program is valuable because it is flexible and can be used to fill gaps in research funding. One stakeholder stated that there are very few funding opportunities like the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grant Program for biomarker work, as funding for research bridging both early science and clinical research is rare.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.