FEDERAL CUSTODY

Bureau of Prisons and ICE Should Take Actions to Improve Access to Menstrual Products

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Gretta L. Goodwin at GoodwinG@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) institutions generally make menstrual products available to incarcerated and detained individuals; however, a few of the 29 institutions that housed women in fiscal year 2024 do not fully adhere to all required elements of BOP’s policy. For example, based on site visits and questionnaire responses, GAO found that not all institutions provide the five required types of products in common areas or replenish menstrual products within 24 hours. BOP has two oversight mechanisms to monitor whether institutions adhere to its policy. However, neither mechanism has systematically assessed, detected, and rectified all deficiencies across BOP institutions related to providing menstrual products. By conducting routine, systematic oversight, BOP could better ensure that menstrual products are consistently, appropriately, and equitably available and accessible to incarcerated and detained individuals.

Of the 31 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities GAO visited or whose officials responded to GAO’s questionnaire, facilities generally make at least some menstrual products available to detained individuals. However, ICE’s detention standards do not have specific detail to allow its oversight mechanism to detect variation in access to menstrual products. ICE conducts inspections of facilities against their assigned detention standards, which outline how facilities are to provide safe, secure, and humane confinement. Without more detailed language in these standards, inspections cannot detect deficiencies related to access to menstrual products. GAO found variation in (1) the types of menstrual products facilities provide, (2) how facilities provide products, and (3) the quantity limits that facilities apply. By revising the detention standards to clarify requirements, ICE could better ensure menstrual products are consistently, appropriately, and equitably available and accessible to detained individuals.

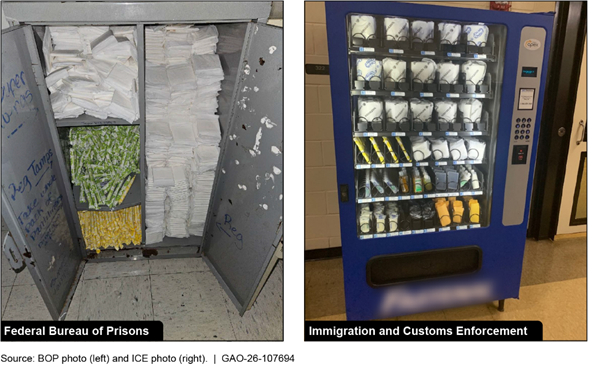

Examples of the Provision of Menstrual Products at Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Institutions and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities

Why GAO Did This Study

BOP and ICE incarcerated and detained tens of thousands of women in fiscal year 2024. These agencies are responsible for caring for the individuals in their custody. This includes providing hygiene items like menstrual products.

GAO was asked to review the availability and accessibility of menstrual products for vulnerable populations, including incarcerated and detained individuals. This report examines the extent to which (1) BOP provides access to menstrual products for incarcerated and detained individuals and (2) ICE provides access to menstrual products for detained individuals. GAO visited a nongeneralizable sample of five BOP institutions and three ICE facilities. These locations were selected based on the number of individuals housed and security level or facility type, among other criteria. During these visits, GAO observed the provision of menstrual products and interviewed facility staff and incarcerated and detained individuals. GAO also reviewed agency documents and conducted a web-based survey of 29 BOP institutions and 52 ICE facilities. GAO analyzed the responses received from officials from 100 percent of BOP institutions and 58 percent of ICE facilities (30).

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to BOP and one to ICE. GAO recommends that (1) BOP ensure its oversight activities monitor adherence to its policy on providing menstrual products, and (2) ICE clarify requirements related to providing menstrual products in its detention standards. BOP concurred. ICE did not, stating that its standards are intended to provide guidance and flexibility. GAO continues to maintain that the recommendation is warranted, as discussed in the report.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AIC |

adult(s) in custody |

|

BOP |

Federal Bureau of Prisons |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

SHU |

Special Housing Unit |

|

SMU |

Special Management Unit |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 2, 2026

Congressional Requesters

Within the Department of Justice, the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is responsible for detaining and incarcerating people in federal custody.[1] Within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is responsible for detaining a subset of noncitizens to ensure their presence for immigration proceedings, to facilitate removals to their countries of citizenship, and to protect public safety in cases where an individual’s criminal history may pose a risk to others.[2] BOP and ICE are responsible for the care of the people in their custody.

Individuals who menstruate may face challenges accessing menstrual products while incarcerated or detained, such as in BOP institutions and ICE facilities. Studies have highlighted the strategies individuals use to manage their menstruation when they cannot access sufficient products while incarcerated, such as bartering with others for menstrual products, wearing products for longer periods of time, and using homemade products. For example, a 2023 study showed that just over half of a nongeneralizable sample of individuals reported not receiving enough menstrual products when they needed them while they were incarcerated.[3] Almost 30 percent of individuals in the study sample reported that they had bartered food, items, and personal favors to obtain menstrual products. Moreover, that study showed just under half of their sample of individuals reported that they wore menstrual products for longer than they wanted to while they were incarcerated. About a quarter of the individuals in the study reported that they had negative health outcomes from the prolonged use of menstrual products.

In a 2024 study reviewing published media and research reports from incarcerated individuals, the authors found that individuals created homemade products from other absorbent materials, such as clothing, rags, bed sheets, mattress stuffing, and notebook paper. Individuals in this study reported that using homemade products caused negative physical health impacts, including infection and toxic shock syndrome.[4]

You asked us to review the availability and accessibility of menstrual products for vulnerable populations, including incarcerated and detained individuals.[5] This report examines the extent to which (1) BOP provides access to menstrual products for incarcerated and detained individuals and (2) ICE provides access to menstrual products for detained individuals.

To determine the extent to which BOP provides access to menstrual products for incarcerated and detained individuals, we conducted site visits to a nongeneralizable sample of five BOP institutions. During these visits, we observed what type of menstrual products—pads, tampons, panty liners—are provided, how they are provided, and when. We selected institutions to ensure variation in the number of women housed and security level, among other criteria. The evidence gathered from these site visits is not generalizable but provides examples of the types of menstrual products provided, as well as how and when BOP officials provide access to menstrual products.

Additionally, we reviewed agency policy, guidance, and other documents related to the provision of menstrual products, such as the Female Offender Manual.[6] Further, we reviewed policies and procedures that guide how oversight groups within BOP are to assess the extent to which institutions adhere to agency policy, such as BOP’s Program Review Division’s internal audit process. We reviewed documentation from these internal audits conducted in fiscal year 2024. We assessed the extent to which the agency’s audit process was effectively operating to identify deficiencies.

Further, we deployed a web-based questionnaire to officials at all 29 BOP institutions that housed women in fiscal year 2024.[7] The questionnaire included questions about the type of menstrual products available and how institutions make menstrual products available to incarcerated and detained individuals, among other topics. We received a response rate of 100 percent from BOP institutions. For more information about the survey design and administration, see appendix I. Additionally, appendix II contains the full questionnaire responses from officials from BOP institutions.[8]

Moreover, we interviewed officials from BOP headquarters to understand how they designed policies for their institutions regarding the provision of menstrual products and how they oversee the extent to which institutions are implementing these policies. Additionally, we interviewed officials at five BOP institutions during the site visits described above. In these interviews, we spoke with leadership at each institution, such as the warden or their designee. Further, we spoke with staff members responsible for selecting and procuring menstrual products, as well as employees who work with incarcerated and detained individuals on a regular basis, such as housing unit staff members and managers.

In addition, we spoke with individuals who were incarcerated or detained in those five institutions about their experiences accessing menstrual products while in these institutions, among other topics. In total, we conducted interviews with 45 English- and Spanish-speaking incarcerated and detained individuals in BOP institutions. We did not independently verify the veracity of all statements made by incarcerated and detained individuals, but we were sometimes able to corroborate their statements via direct observation or interviews with other staff or individuals at that institution. The information obtained during these interviews is not generalizable to all incarcerated and detained individuals, but it provides examples of the experiences of incarcerated and detained individuals in BOP custody.

To determine the extent to which ICE provides access to menstrual products for detained individuals, we conducted site visits to a nongeneralizable sample of three ICE facilities. On the visits to these facilities, we observed what types of menstrual products—pads, tampons, panty liners—are provided, how they are provided, and when. We selected facilities to ensure variation in the number of women housed and facility type, among other criteria.[9] The evidence gathered from these site visits is not generalizable but provides examples of the types of menstrual products provided, as well as how and when ICE officials provide access to menstrual products.

We also reviewed agency policy, guidance, and detention standards related to the provision of menstrual products at ICE facilities. Additionally, we reviewed policy and procedures that guide how oversight groups within ICE are to assess the extent to which facilities adhere to the detention standards. We determined that the control activities component of the federal standards for internal control was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principle that management should implement control activities through policies.[10] We assessed the design of the agency’s policies to determine whether they were documented in enough detail to allow management to effectively monitor the activity.

Further, we deployed a web-based questionnaire to officials at all 52 ICE facilities that housed women in fiscal year 2024.[11] The questionnaire included questions about the type of menstrual products available and how ICE facilities make menstrual products accessible to detained individuals. We received a response rate of 58 percent from ICE facilities (30 out of 52).[12] For more information about the survey design and administration, see appendix I. Also, appendix III contains the full questionnaire responses from officials from the ICE facilities.

Moreover, we interviewed ICE headquarters officials to understand how they designed the detention standards regarding provision of menstrual products in ICE facilities and how they oversee the extent to which facilities are implementing these standards. For example, we spoke with officials in ICE’s Office of Detention Oversight, which is a component of ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility. Additionally, we interviewed officials at three ICE facilities in our site visits described above. In these interviews, we spoke with leadership at each facility, such as the facility administrator or their designee. Further, we spoke with staff members responsible for selecting and procuring menstrual products, as well as employees who work with detained individuals on a regular basis, such as housing unit staff members and managers.

Finally, we spoke with detained individuals in those three facilities about their experiences accessing menstrual products, among other topics. In total, we conducted interviews with 23 English- and Spanish-speaking detained individuals in ICE facilities. We did not independently verify the veracity of all statements made by detained individuals, but we were sometimes able to corroborate their statements via direct observation or interviews with other staff or individuals in that facility. The information obtained during these interviews is not generalizable to all detained individuals, but it provides examples of the experiences of individuals detained in ICE facilities.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities

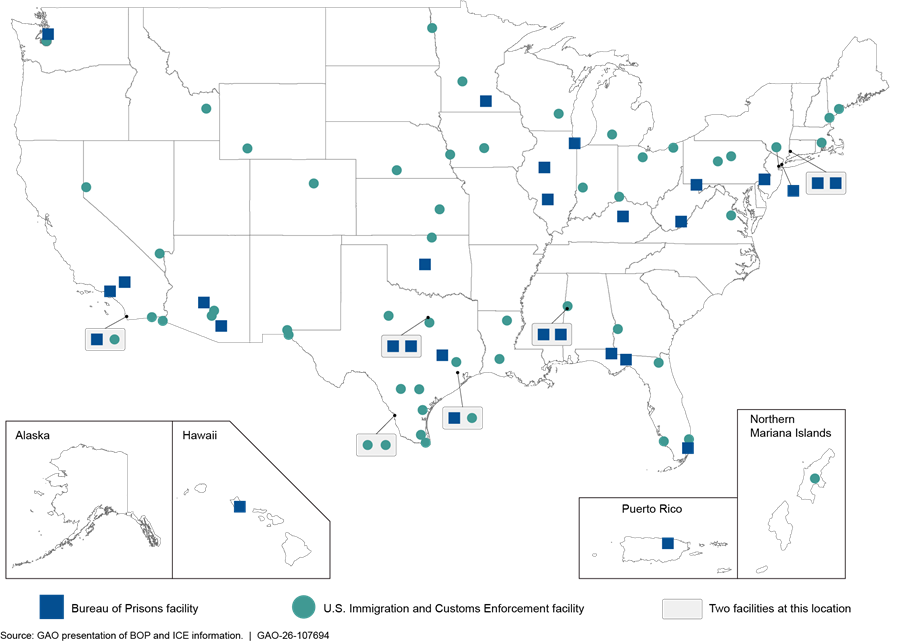

BOP incarcerated or detained women in 29 institutions in fiscal year 2024. According to BOP officials, 8,738 individuals were incarcerated or detained in women’s housing units in federal prisons as of September 28, 2024.[13] This accounted for 6.1 percent of all individuals incarcerated or detained in BOP institutions on this day.

ICE detained women in 52 facilities in fiscal year 2024. According to ICE officials, ICE had 53,081 detentions in women’s housing units in fiscal year 2024.[14] This accounted for 19.1 percent of detentions in ICE facilities in that fiscal year.

See figure 1 for a map of where these institutions and facilities are located.

Figure 1: Locations of Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Institutions and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities That Housed Women in Fiscal Year 2024

Oversight

According to BOP interim guidance issued in March 2024, within BOP’s central office, the Program Review Division conducts audits of BOP institutions.[15] According to this guidance, the Program Review Division is implementing a new internal audit process with a goal of auditing every institution at least once every 5 years. Audits are not comprehensive, as they are conducted based on the highest risks to site operations, such as staffing levels, administrative remedies, work orders, and medical information. Additionally, the Reentry Services Division, the Women and Special Populations Branch, and the Office of Internal Affairs assess the culture of BOP institutions that house women. According to BOP, this process assesses each institution’s use of care principles that are responsive to the needs of women and trauma informed, effective and appropriate communication, and level of sexual safety.[16]

ICE facilities are subject to inspections or investigation by entities within DHS. For example, within ICE, the Office of Detention Oversight conducts semiannual inspections of each facility that serve as the facility’s inspection of record.[17] The Office of Detention Oversight inspects whether each facility adheres to the detention standards they are obligated to meet according to their contract or agreement with ICE. ICE developed these standards for immigration detention to dictate how facilities should operate to ensure safe, secure, and humane confinement. ICE has updated or introduced new detention standards a few times since they were initially developed in 2000, resulting in various versions—or “sets”—of standards that differ with respect to their scope and rigor. Other DHS entities that may also inspect ICE facilities include the Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman, Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, and Office of the Inspector General.[18]

Accessibility

Literature in the field of access to health care defines “access” along five dimensions.[19] The dimensions, and how they might be applied to the accessibility of menstrual products, are the following:

· Availability, which might be assessed by considering the extent to which incarcerated and detained individuals receive an adequate supply of menstrual products. Individuals’ menstrual cycles, and thus their unique needs related to menstrual products, may vary significantly based on age, ethnicity, physical activity, certain health conditions, and body mass index, according to studies.[20]

· Accessibility, which might be assessed by whether menstrual products are provided in an open area or behind a locked door.

· Accommodation, which might be assessed by whether menstrual products are available at all times of day and replenished in a timely manner.

· Affordability, which might be assessed by comparing the cost of menstrual products to detained and incarcerated individuals’ incomes.

· Acceptability, which might be assessed by asking individuals how satisfied they are with the selection of menstrual products (pads, tampons, and panty liners) and how they are provided.

BOP Institutions Generally Make Menstrual Products Accessible, but a Few Institutions Do Not Fully Adhere to BOP Policy

The Female Offender Manual (referred to as the Manual) outlines BOP’s policy regarding how wardens at its institutions are to provide menstrual products to incarcerated and detained individuals. Generally, BOP institutions make products available to incarcerated and detained individuals; however, not all fully adhere to all elements of BOP’s policy. Moreover, BOP has oversight mechanisms to determine whether institutions comply with agency policy, but these mechanisms have not systematically assessed, detected, and rectified all deficiencies across BOP institutions related to the provision of menstrual products.

BOP Policy Requires Institutions to Provide Menstrual Products

The Manual states that all institutions housing females offer programs, services, and policies that address the unique needs of these incarcerated and detained individuals.[21] In alignment with a provision of the First Step Act of 2018, the Manual requires institutions to provide access to menstrual products.[22]

The Manual states that institution wardens are to provide—at no cost to incarcerated and detained individuals—five types of menstrual products: regular and super size tampons, regular and super size pads with wings, and panty liners.[23] For incarcerated and detained individuals in general population, all menstrual products must be made available in common areas, such as a bathroom or other accessible area of the housing unit. Individuals must have access to these items at all times of the day and may keep them in their cells, consistent with personal property requirements. Units must replenish pads, tampons, and panty liners within 24 hours of staff being notified that a particular product is lacking. Staff are prohibited from monthly issuance of these items, and products may not be rationed. For incarcerated and detained individuals in restrictive housing (more commonly referred to as the special housing unit, or the “SHU”), the Manual states that all five types of products must be available for issuance daily.

The Manual further states that misuse of items for other than their intended purpose is not cause for withholding access and instructs staff to manage misuse via routine disciplinary procedures.

BOP Institutions Provide Menstrual Products in a Variety of Ways

|

Menstrual Products: Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Admissions and Orientation Handbooks BOP policy requires that all institutions provide incarcerated and detained individuals with a copy of the admissions and orientation handbook when they arrive (Bureau of Prisons, Correctional Programs, G5000I.12. [Jan. 9, 2024]). The handbook provides information regarding institution programs, rules, and regulations individuals will encounter during their incarceration. Handbooks for institutions that house women are also to include a brochure that outlines issues directly pertaining to women. This brochure is called “Attachment D” and titled, “Empowering Women: A Guide to Successfully Navigating Your Institution.” The brochure includes sections on (1) the programs that institutions offer that are responsive to the needs of women; (2) legislation relevant to incarcerated and detained women, such as the Violence Against Women Act and the Prison Rape Elimination Act; and (3) details on policies relevant to incarcerated and detained women, such as requirements for institutions to provide menstrual products free of charge. Source: GAO analysis of BOP documents. | GAO‑26‑107694 |

During our site visits, we observed how five BOP institutions made menstrual products available to incarcerated and detained individuals. For example, at one institution, staff provided menstrual products in containers in the common area in the housing unit. At three institutions, staff provided products in containers in the bathrooms. Staff at these four institutions also maintained a storage cabinet with a backup supply of menstrual products and can access additional products from a warehouse located at the institution. At the fifth institution we visited, however, we observed an empty storage container for menstrual products inside the housing unit’s common area, which we discuss in more detail later in this report. See figure 2 for examples of how some BOP institutions we visited provided menstrual products.

Officials from all 29 BOP institutions that housed women in fiscal year 2024 responded to our web-based questionnaire, and their responses indicated there is variation in how institutions provided menstrual products similar to what we observed during our site visits.[24] For example, officials from 23 institutions reported providing menstrual products in housing unit

|

Menstrual Products: Product Quality in Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Institutions The First Step Act requires that the Director of BOP ensures that the menstrual products provided at its institutions conform with applicable industry standards for quality. According to BOP officials we interviewed, the Food and Drug Administration considers menstrual products to be medical devices but does not set minimum standards for product quality. Officials said they are not aware of any industry standards that govern the quality of menstrual products. The quality of products may influence whether these products are acceptable to incarcerated and detained individuals. According to officials, staff at individual institutions are responsible for purchasing menstrual products, and they should be assessing the quality of those products. Surveyed officials from 14 of the 29 institutions reported that they assess the quality of the menstrual products they provide for free. Officials at nine of these institutions reported that they seek feedback from the incarcerated and detained individuals about the quality of these menstrual products. Of the 41 incarcerated and detained individuals we spoke with who used the free menstrual products at their institutions, 20 said they were unsatisfied with either the quality or selection of the products. For example, individuals said that the pads were either too thin or too thick, were not sufficiently absorbent, or did not stick well enough to undergarments. Individuals said that the tampons were cheap, not absorbent enough, or the cardboard applicator was uncomfortable. Two dozen incarcerated and detained individuals we spoke with said they knew of someone or had themselves experienced soiled clothing or bedding while using free menstrual products. According to BOP officials, individuals may soil clothing or bedding for several reasons, including product quality or incorrect use. Officials said that individuals may purchase menstrual products from the commissary if they are unsatisfied with the free products. Twelve individuals we spoke with said they had purchased menstrual products from the commissary, and five of them said the commissary products are better quality than products provided for free. Source: GAO analysis of questionnaire responses from 29 BOP institutions that housed women in fiscal year 2024, interviews with BOP officials, and interviews with incarcerated individuals. I GAO‑26‑107694 |

common areas. Officials from 19 institutions reported that products were available in unit bathrooms. Outside the housing units, the most common locations for menstrual products were visiting rooms and receiving and discharge where individuals arrive and are processed into institutions (23 institutions offered products in each of these areas, respectively). Fewer institutions provided menstrual products in recreation areas (18 institutions) and dining areas (11 institutions). See appendix II for more information about where institutions made menstrual products available, according to officials’ questionnaire responses.

We also found variation in who replenishes menstrual products, which can lead to unequal distribution. For example, in our site visits, we found that at two institutions, only a staff member such as a housing unit counselor or correctional officer was responsible for replenishing menstrual products. At three institutions, we found that the institution also authorized incarcerated and detained individuals to stock menstrual products in their housing units. These individuals were often referred to as “orderlies,” and they sometimes had other duties, such as cleaning. Officials explained that relying on orderlies reduced staff workload.

However, according to half a dozen incarcerated and detained individuals we interviewed, orderlies do not consistently distribute menstrual products in an equitable way that ensures they are available to all individuals. For example, incarcerated and detained individuals we interviewed shared examples of times when orderlies gave menstrual products to certain individuals first and restocked for others only after those needs were met. A dozen incarcerated and detained individuals across three institutions we visited told us they had to rely on other incarcerated and detained individuals to share menstrual products with them. Housing staff at two institutions confirmed that they direct individuals to ask other incarcerated and detained individuals to share extra menstrual products if the unit runs low.

Most, but Not All, BOP Institutions Comply with BOP Policy on Provision of Menstrual Products

While most BOP institutions comply with all elements of BOP’s policy on the provision of menstrual products, not all do so fully or consistently. For example, we found that a few institutions do not provide the required types of products in common areas or replenish products within 24 hours as required by the Manual. Additionally, we found that BOP’s oversight mechanisms have not consistently assessed, detected, and rectified these deficiencies.

Most Institutions Provided the Five Required Menstrual Product Types at No Cost in a Common Area

The Manual states that institutions must provide five types of menstrual products at no cost; however, we found that not all do so. During our site visits, we observed that four of five institutions provided the five required types of products to incarcerated and detained individuals at no cost; the fifth did not. Moreover, surveyed officials from an additional two of the 29 BOP institutions reported that they do not provide all five required product types at no cost. For example, officials from one of these institutions reported providing only regular tampons and regular pads at no cost. Officials from the second institution reported providing only super size tampons and super size pads at no cost. See table 1 for how many of the 29 BOP institutions reported providing each type of required menstrual product at no cost.

Table 1: Number and Percent of Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Institutions That Reported Providing Each Type of Required Menstrual Product and at What Cost in Fiscal Year 2024

|

Product type |

Provided at no cost |

Provided for purchase only |

Not provided |

No answer |

|

|

Number (percenta) |

Number (percent) |

Number (percent) |

Number (percent) |

|

Tampons – regular |

27 (93) |

1 (3) |

0 (0) |

1 (3) |

|

Tampons – super |

28 (97) |

1 (3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Pads – regular |

28 (97) |

1 (3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Pads – super |

28 (97) |

1 (3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Panty liners |

27 (93) |

2 (7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Source: GAO analysis of questionnaire responses from 29 BOP institutions. I GAO‑26‑107694

Note: The question read, “Please indicate if your institution provided menstrual products (tampons, maxi-pads, and panty liners) to adults in custody (AIC) and at what cost during fiscal year 2024 (10/1/2023–9/30/2024). (Select one response per row).”

aPercentages of responses are presented to the nearest whole percentage point. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Additionally, we found that one institution did not provide menstrual products in a common area such as a bathroom, as required by the Manual. Specifically, according to their questionnaire response, officials from that institution reported that incarcerated and detained individuals in at least one housing unit must ask a staff member for menstrual products when needed.

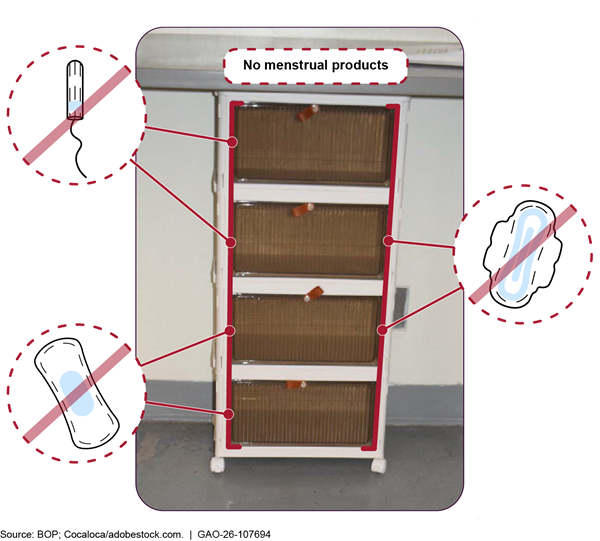

Most, but Not All, Institutions Replenish Menstrual Products Within 24 Hours

The Manual states that menstrual products must be replenished within 24 hours of staff being notified that a particular product is lacking. Based on our site visits, questionnaire responses, and interviews, we found that while most institutions comply with this requirement, not all do. At one institution, for example, we observed that menstrual products were designated to be placed in containers in the housing unit’s common area, but those containers were empty. We observed at this institution that when staff brought boxes of menstrual products to the housing unit, incarcerated and detained individuals immediately claimed them all and the containers were left empty. As a result, individuals who needed products may not have received them. We observed the containers were still empty the next day. See figure 3.

Note: This storage container allows incarcerated and detained individuals and staff members to see the contents inside without opening it. The four cabinet drawer doors are translucent plastic with ridges. In the picture, the bottom and back of each compartment is visible, and shows that this container is empty. On both days of our visit, we observed that the container was empty, and at no point did we observe staff putting products into the container. Staff acknowledged that the container was empty and stated that they bring menstrual products to the unit only once per week.

According to staff at that same institution, staff only bring menstrual products to the housing unit once per week on Mondays. Incarcerated and detained individuals at that institution affirmed statements made by staff on when and how often menstrual products are made available. Moreover, eight incarcerated and detained individuals at that institution reported to us that staff refused to provide more menstrual products when they specifically asked for them. Additionally, five individuals from this institution told us staff directed them to ask other incarcerated and detained individuals in the unit for menstrual products. Further, three incarcerated and detained individuals from this institution said this can sometimes lead to individuals selling, bartering, begging for, and stealing menstrual products.

At two other institutions we visited, incarcerated and detained individuals said their institutions had at times run out of one or more products for more than 24 hours. During our 45 interviews with incarcerated and detained individuals across five institutions, 32 mentioned relying on other incarcerated and detained individuals for menstrual products when they ran out or having to ask staff to provide more. According to officials at these institutions, maintaining an adequate supply of menstrual products in the units can be difficult. They noted that delays in delivery or purchasing from vendors sometimes leaves them without one or more required products. When shortages occur, staff said they may place orders with alternate vendors or authorize purchases from local stores until regular supplies arrive.

In addition to what we observed during our site visits, officials from two other institutions also reported in their questionnaire responses that they do not always replenish menstrual products within 24 hours of being notified that a particular product is low, as required by the Manual. See table 2.

Table 2: Number and Percent of Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Institutions That Reported Replenishing Menstrual Products by Time frame, fiscal year 2024

|

|

Number (percenta) |

|

Usually within 12 hours. |

25 (86) |

|

Not within 12 hours, but usually within 24 hours. |

1 (3) |

|

Not within 24 hours, but usually within 48 hours. |

2 (7) |

|

Sometimes it took longer than 48 hours. |

0 (0) |

|

Don’t know. |

1 (3) |

Source: GAO analysis of questionnaire responses from 29 BOP institutions. I GAO‑26‑107694

Note: The question read, “Once a staff member noticed, or an adult in custody notified a staff member, that menstrual products ran low or ran out, how quickly were products replenished? (Select one).”

aPercentages of responses are presented to the nearest whole percentage point. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

BOP’s Oversight Mechanisms Have Not Systematically Assessed for Deficiencies Related to Menstrual Products

BOP has two internal oversight mechanisms that are meant to determine the extent to which institutions comply with agency policy: internal audits by the Program Review Division and women’s institution cultural assessments by the Reentry Services Division and the Women and Special Populations Branch. Neither of these mechanisms have systematically assessed for, detected, and rectified all deficiencies related to the provision of menstrual products across BOP institutions. Further, officials said they are not certain that the Program Review Division will be able to meet its stated goal to assess all institutions at least once every 5 years.

First, BOP’s Program Review Division conducts internal compliance audits, which are used to identify causes of and mitigate common and recurring deficiencies at institutions.[25] Audit teams follow interim guidance that in March 2024 updated their internal process to inspect whether institutions comply with the agency’s policy requirements. However, not all audits assess all institutions against every policy requirement.

According to BOP, audits using the new internal process have been completed at three institutions. Two audits assessed the availability of menstrual products as part of their scope.[26] One of these audits had findings and recommendations to improve access to menstrual products, and the other did not have findings on this topic. Each audit team developed its own planned methodology, in accordance with the interim guidance. For the audit that had findings related to menstrual products, documentation shows that the team had a rigorous process, including direct observation and many interviews with institution staff and incarcerated and detained individuals.[27] However, this audit did not evaluate the institution’s adherence to all elements of BOP’s policy. For example, the audit did not ask staff or incarcerated and detained individuals about availability of menstrual products in the special housing unit, nor about whether individuals may keep menstrual products with their personal items.

For the audit that did not have findings related to menstrual products, documentation shows the audit had a less rigorous process than the other audit. For example, this audit team documented “a variety” of product sizes in the housing units, while the other audit team systematically documented the presence of each of the five required product types in each housing unit. Further, this audit team documented that they discussed availability of menstrual products with an unspecified number of incarcerated individuals, while the other audit team documented structured interviews with about 20 percent of the incarcerated individuals from each housing unit. Additionally, this audit team did not evaluate the institution’s adherence to all elements of BOP’s policy. For example, the team did not ask about availability in the special housing unit, keeping products with personal items, whether products were rationed, or whether incarcerated and detained individuals were denied products after they used them for alternative purposes.

Further, according to the interim guidance, BOP’s goal is to audit every institution at least once every 5 years. However, officials said the Program Review Division continues to assess resources, including funding, to be able to finalize its new internal audit process. Program Review Division officials said they do not know at this point whether the division will be able to audit institutions every 5 years due to resource limitations. As a result, the extent of BOP’s ability to conduct audits at all institutions on a recurring basis is unknown.

Second, BOP’s Reentry Services Division and the Women and Special Populations Branch are to conduct cultural assessments at institutions that house women. This assessment is a framework that provides a snapshot of operations, programming, and service gaps to identify institution needs specific to managing women’s institutions. From fiscal year 2022-2024, BOP conducted 32 such assessments. BOP officials stated that assessment teams assess the availability of menstrual products, and they follow the Women’s Institution Cultural Assessment Guide.[28] The guide outlines steps related to assessing the availability of menstrual products; however, these steps do not systematically address all aspects of BOP’s policy on menstrual products, and assessment teams are not required to conduct these steps. Specifically, assessment teams may ask incarcerated and detained individuals the one question listed in the Assessment Guide related to menstrual products: “How are free feminine hygiene products made available?” Additionally, assessment teams may discuss the availability of menstrual products at no cost with staff from two of 19 departments as applicable at the institution.

However, assessment teams are not required to discuss the suggested topics, such as the question about menstrual products. Additionally, language for the suggested topics in the cultural assessments does not address all elements of BOP’s policy related to menstrual products. For example, the language does not address whether the products are provided in sufficient quantity or if staff ration them. If assessment teams use other processes to evaluate the provision of menstrual products, those processes are not outlined in the Assessment Guide. Moreover, BOP officials did not provide other documents to support the extent to which these processes are systematic.

We found that of the 32 assessments in fiscal years 2022-2024, 13 had recommendations related to the provision of menstrual products, according to their final reports. This included two institutions that received a recommendation related to menstrual products in more than one cultural assessment, meaning the institutions did not sufficiently rectify the deficiency after the first assessment. The final reports for an additional two assessments discussed the provision of menstrual products but did not make recommendations on the topic. For the remaining assessments, their final reports do not mention menstrual products, so it is unclear whether and how teams assessed the availability of menstrual products.

Further, within individual institutions, oversight on the bins being filled or empty of menstrual products is ad hoc rather than systematic. Staff at three institutions we visited, for example, said they perform spot checks of the supply levels of menstrual products in the housing unit containers when they are in the units. Officials at one of these institutions also said they rely on orderlies to inform them when the supply of any menstrual product is low. Without consistently monitoring the extent to which institutions fully comply with agency policy regarding access to menstrual products, BOP cannot systematically identify and rectify deficiencies in access. Implementing recurrent, systematic oversight of the provision of menstrual products can help BOP leadership better ensure that menstrual products are consistently, appropriately, and equitably available and accessible to incarcerated and detained individuals.

ICE Facilities Generally Provide Menstrual Products, but Nonspecific Detention Standards Limit Oversight

ICE facilities generally make menstrual products available to detained individuals. However, detention standards that dictate how facilities should operate to ensure safe, secure, and humane confinement are not specific about the provision of menstrual products. As a result, oversight mechanisms cannot detect variation in access to menstrual products across facilities.

National Detention Standards. ICE information shows that each facility that houses women is assigned to one of three sets of detention standards within their contracts or other agreements: the National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities (revised 2019), Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (revised 2016), or Federal Performance-Based Detention Standards.[29] ICE assigns one of these sets of standards to each facility within their contracts or other agreements. Each set of detention standards outlines how facilities are expected to provide safe and secure environments, as well as requirements for providing food, medical care, and hygiene items for people in its facilities.

However, we found that these detention standards are inconsistent and lack detailed language regarding how facilities are to provide menstrual products to detained individuals. For example, of the two sets of detention standards that explicitly mention the provision of menstrual products, one set specifies that the facility must replenish products at no cost to detained individuals, while the other does not. The third set of detention standards does not mention menstrual products at all. The three sets of detention standards do not include information such as how individuals can access menstrual products and the size or quantity of products that must be provided. See table 3 for more information about the content related to menstrual products in each set of detention standards.

Table 3: Detention Standards for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities Regarding the Provision of Menstrual Products

|

Detention standarda |

Standard regarding provision of menstrual products |

|

National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities (revised 2019) |

Female detainees shall be issued and may retain sufficient feminine hygiene items, including sanitary pads or tampons, for use during the menstrual cycle. The facility shall replenish personal hygiene items at no cost to the detainee on an as-needed basis, in accordance with written facility procedures. |

|

Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (revised 2016) |

Female detainees shall be issued and may retain sufficient feminine hygiene items, including sanitary pads or tampons, for use during the menstrual cycle. The responsible housing unit officer shall replenish personal hygiene items on an as-needed basis, in accordance with written facility procedures. |

|

Federal Performance-Based Detention Standardsb |

Does not mention menstrual products. |

Source: GAO analysis of ICE and U.S. Marshals Service documents. | GAO‑26‑107694

aThese are the detention standards for the ICE facilities that housed women for over-72 hours in fiscal years 2023 or 2024. The National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities (revised 2019) is 226 pages. The Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (revised 2016) is 475 pages.

bICE information indicates that ICE housed women at 16 U.S. Marshals facilities under intergovernmental agreements in fiscal year 2024. According to U.S. Marshals officials, the intergovernmental agreements state that Federal prisoners shall be housed in a manner consistent with a subset of the Federal Performance-Based Detention Standards and any other standards required by an authorized agency (such as ICE) whose incarcerated or detained individuals are housed pursuant to the agreement. ICE information shows that during the two most recent inspections, ICE inspectors assessed these facilities against ICE detention standards. Most were assessed against ICE’s National Detention Standards for Non-Dedicated Facilities (revised 2019) in their inspections conducted between September 28, 2023, and July 11, 2024.

According to officials at ICE headquarters, the detention standards allow facilities the flexibility to develop their own procedures to meet the standards consistent with local conditions and constraints. These officials said ICE does not expect or require facilities to document the details of these procedures in local facility documents (such as handbooks) beyond the language that appears in the detention standards. As a result, while some facilities’ documents provide specific information on access to menstrual products (for example, times when products will be available or how many menstrual products facilities will provide to detained individuals), others are not any more specific than the detention standards. This can create inequity and confusion for detained individuals across ICE facilities.

Oversight of ICE detention facilities. ICE’s Office of Detention Oversight conducts biannual inspections of all over-72-hour facilities to ensure they are adhering to their assigned set of detention standards.[30] According to officials we spoke with, the inspections team go on facility tours and conduct interviews with detained individuals.[31] During the inspections, inspectors do a line-by-line review of whether the facility adheres to its assigned detention standard. According to officials, the line items in the inspection worksheet phrase the language in the standard as a question, and do not ask questions that do not appear directly in the standards. As a result, inspection teams are unable to consistently detect variation or potential problems if they are not specified in the standard.

According to officials, in fiscal year 2024, the Office of Detention Oversight inspected its facilities against the personal hygiene standard, which is present in two of the three detention standards.[32] The personal hygiene standard includes one question related to menstrual products: “Are female detainees issued and able to retain sufficient feminine hygiene items, including sanitary pads or tampons, for use during the menstrual cycle, and permitted brushes to replace combs?” Officials said they did not find any deficiencies related to menstrual products during these inspections. However, officials said they also did not observe the variation in methods that facilities provide menstrual products, the variation in types of products offered, or other details because these questions were not on their inspection worksheet. Further, officials stated that any denial of menstrual products to detained individuals would not comply with the detention standards. However, they could not detect whether officials deny menstrual products because this detail is not part of the detention standards.

Facility provision of menstrual products. Through our site visits, interviews with detained individuals, and questionnaire responses, we found that ICE facilities vary in (1) how they provide menstrual products to detained individuals, (2) the type of menstrual products they provide, and (3) the quantity they provide.

First, we found that ICE facilities use different methods to make menstrual products accessible to detained individuals. For example, in one facility we observed a vending machine located in the common area of each housing unit from which detained individuals can obtain menstrual products at no cost. Officials said individuals scan their ID card to access free hygiene items from the machine. However, we observed several detained individuals who attempted but were unable to access the products in the vending machine. According to staff, there are multiple reasons why an ID card might fail, including user error and improper card activation. We heard from detained individuals that it took 2 days for their ID cards to be activated, the vending machine sometimes does not work, and the machine sometimes runs out of products. As a result, detained individuals said they had to ask staff or other detained individuals for menstrual products.

At a second facility we observed a cart in the common area in the center of the housing units with personal hygiene items, including pads. At a third facility we observed two housing units within that facility provide products differently. In one housing unit, we observed that staff kept menstrual products locked in a desk and required individuals to ask for menstrual products. In the second housing unit, we observed menstrual products in small plastic bins in a common area that individuals could freely access. See figure 4 for pictures of how ICE facilities we visited provide menstrual products at no cost to detained individuals.

Figure 4: Examples of Different Methods for Providing Menstrual Products at No Cost in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities

|

Menstrual Products: Product Quality in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities The quality of menstrual products may influence whether these products are acceptable to detained individuals. Detained individuals at all three ICE facilities we visited expressed dissatisfaction with the type or quality of the products offered. For example, detained individuals said they must use more than one product at a time to be effective. One detained individual said she uses multiple pads at once because the pads are too thin and small to absorb appropriately. An individual at another facility said she uses two pads and a tampon to manage her heavy flow due to the quality of the products. Detained individuals said pads move around due to poor adhesive or lack of wings. More than one detained individual we spoke with said the pads do not stick well or remain in place. Additionally, detained individuals said the menstrual products provided are uncomfortable. For example, more than one detained individual said the quality of the pads irritated her skin. Officials from one facility said detained individuals also recently requested super absorbency pads with wings. At the time of our visit, they said they had just purchased some to test in one housing unit. Officials said if detained individuals tell them that the new product works better than the current product, they plan to make the change permanent across housing units. Source: GAO interviews with detained individuals at ICE facilities and ICE officials. | GAO‑26‑107694 |

The variation in how menstrual products were made accessible at facilities we visited was also apparent across the 30 ICE facilities whose officials responded to our questionnaire.[33] Officials from 12 facilities reported that detained individuals can retrieve menstrual products without asking staff for assistance. At three of these facilities, officials reported that menstrual products are available in the housing unit bathrooms. In addition, at 11 of the 12 facilities, officials reported that menstrual products are available in a common area other than the bathroom.

Similar to what we observed at one facility we visited, surveyed officials from two of the 30 facilities reported that in one housing unit, detained individuals must ask for menstrual products, while in another, individuals can obtain products without asking facility staff for assistance. Second, we found that facilities vary in the types of menstrual products that they offered. For example, at one ICE facility we visited, the facility provided regular and super absorbency options for both tampons and pads. At a second facility we visited, the facility provided regular absorbency pads without wings accessible on a cart, but they made panty liners available only upon request. Officials from this facility said detained individuals occasionally request tampons, but the facility does not provide them because they consider them to be a security risk.

The variation we saw across the three facilities we visited was also apparent across the 30 facilities whose officials responded to our questionnaire. Officials from 10 of 30 ICE facilities that house women (33 percent) responded that they offer only one type of menstrual product at no cost.[34] Officials from 13 of 30 facilities (48 percent) responded that they offer two types of menstrual products. See table 4 for more information about how many types of menstrual products officials responded that their facility provided at no cost in fiscal year 2024.

Table 4: Number and Percent of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities That Reported Providing Each Number of Menstrual Product Types at No Cost in Fiscal Year 2024

|

|

Number (percenta) |

|

No product types |

0 (0) |

|

One product type |

10 (33) |

|

Two product types |

13 (43) |

|

Three product types |

3 (10) |

|

Four product types |

3 (10) |

|

Five product types |

1 (3) |

Source: GAO analysis of questionnaire responses from officials from 30 ICE facilities. | GAO‑26‑107694

Note: The question read, “Please indicate if your institution provided menstrual products (tampons, pads, and panty liners) to detained noncitizens and at what cost during fiscal year 2024 (10/1/2023–9/30/2024). (Select one response per row).” We asked facilities if they provided regular and super pads, regular and super tampons, and panty liners.

aPercentages of responses are presented to the nearest whole percentage point. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

The most common types of menstrual product offered at no cost were regular absorbency pads (26 of 30 facilities offered these, or 87 percent) and regular absorbency tampons (16 of 30 facilities, or 53 percent).[35] The least common type of menstrual product offered at no cost was super absorbency tampons (four of 30 facilities, or 13 percent). See table 5 for more information about how many facilities reported providing each type of menstrual product and at what cost.

Table 5: Number and Percent of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Facilities That Reported Providing Each Type of Menstrual Product and at What Cost in Fiscal Year 2024

|

Product type |

Provided at no cost |

Provided for purchase onlya |

Not provided |

No answer |

|

|

Number (percentb) |

Number (percent) |

Number (percent) |

Number (percent) |

|

Tampons – regular |

16 (53) |

1 (3) |

11 (37) |

2 (7) |

|

Tampons – super |

4 (13) |

1 (3) |

15 (50) |

10 (33) |

|

Pads – regular |

26 (87) |

0 (0) |

2 (7) |

2 (7) |

|

Pads – super |

12 (40) |

1 (3) |

9 (30) |

8 (27) |

|

Panty liners |

4 (13) |

1 (3) |

13 (43) |

12 (40) |

Source: GAO analysis of questionnaire responses from officials from 30 ICE facilities. | GAO‑26‑107694

Note: The question read, “Please indicate if your institution provided menstrual products (tampons, pads, and panty liners) to detained noncitizens and at what cost during fiscal year 2024 (10/1/2023–9/30/2024). (Select one response per row).”

aFacilities may offer items for detained individuals to purchase from commissary, such as menstrual products like pads or tampons.

bPercentages of responses are presented to the nearest whole percentage point. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Third, in addition to variation in the products offered and the methods they use to provide them, we found that some ICE facilities limit the number of menstrual products they provide to detained individuals. According to questionnaire responses, officials from 18 facilities reported that they require detained individuals to ask staff, such as a detention officer, for menstrual products when they need them. Of those 18, officials from nine facilities said they do not have a specific limit for the number of products individuals can get at a time. However, officials from eight of these 18 facilities said detained individuals may only ask for two to five products at a time; while another facility said that was the limit for 1 day. Further, officials from the remaining facility said there was a limit of six to 10 products detained individuals may ask for at a time.

|

Menstrual Products: Detained Individuals’ Perspectives on the Availability of Assistance in Spanish Spanish-speaking detained individuals we spoke with said facility staff do not always provide information in Spanish, which could make it difficult to understand what menstrual products are available and how to access them. Officials told us they try to mitigate language barriers by seeking translation assistance from other detained individuals or facility staff, by using hand signals, or translation applications. At one facility we visited, one detained individual said she received an information booklet in Spanish during intake, but could not read. According to the individual, other detained individuals told her how to access personal hygiene products, including menstrual products. Another detained individual said that women at the facility rely on each other for information, especially Spanish-speaking individuals. Source: GAO interviews with detained individuals at ICE facilities and ICE officials. | GAO‑26‑107694 |

Additionally, at one facility we visited, officials said detained individuals can obtain up to 29 products per month at no cost. According to officials at this facility, detained individuals could obtain the monthly allotment at once. However, three detained individuals at this facility said they were unaware of how many menstrual products they are limited to obtaining per month. During our visit, detained individuals indicated that recent policy changes limited how much of the monthly allotment individuals can get at a time.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agency management should implement control activities through policies.[36] For example, units should document policies in the appropriate level of detail to allow management to monitor the activity. ICE facilities could further define policies related to the provision of menstrual products through day-to-day procedures in its detention standards. Procedures may include, for example, the timing of when menstrual products are made available, the number of products a detained individual is entitled to, and any follow-up corrective actions if deficiencies are identified. Without clearly defined requirements related to the provision of menstrual products in its detention standards, ICE’s oversight has limited ability to detect and address gaps in access to menstrual products. Revising these standards to clarify procedures would better ensure menstrual products are consistently, appropriately, and equitably available and accessible to detained individuals across facilities.

Conclusions

BOP and ICE incarcerated and detained tens of thousands of women in fiscal year 2024. These agencies are responsible for caring for incarcerated and detained individuals, including by providing hygiene items like menstrual products. Individuals have different needs for the types and number of menstrual products that will be sufficient for them. Staff at BOP institutions and ICE facilities generally make at least some menstrual products available to those who need them. However, our observations at several BOP institutions and ICE facilities, surveys of BOP and ICE officials, and interviews with staff and incarcerated and detained individuals revealed variation and shortcomings related to the accessibility of menstrual products. BOP’s oversight mechanisms have not routinely assessed whether institutions fully comply with BOP policy regarding provision of menstrual products. Additionally, ICE lacks clear and specific requirements in its detention standards regarding provision of menstrual products, which leads to significant variation within and across facilities that the agency’s monitoring office is not detecting. By improving policy and oversight, BOP and ICE can better ensure that incarcerated and detained individuals have consistent and equitable access to the menstrual products they need.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of two recommendations, including one recommendation to BOP and one recommendation to ICE. Specifically:

The Director of BOP should ensure the Bureau’s oversight activities systematically and routinely monitor adherence to BOP policy on the provision of menstrual products. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of ICE should revise each set of detention standards to clarify requirements related to the provision of menstrual products. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security for review and comment.

In its written comments, reproduced in appendix IV, the Department of Justice’s BOP concurred with our recommendation and identified steps the agency would take to address it. The Department of Justice also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix V, the Department of Homeland Security did not concur with our recommendation for ICE, as discussed below. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Regarding the recommendation that the Director of ICE should revise each set of detention standards to clarify requirements related to the provision of menstrual products. DHS officials stated that ICE’s detention standards serve as guidelines for facilities to operate according to their individual operational needs and security concerns. According to DHS, the ICE detention model provides flexibility in creating customized plans consistent with custody operations based on needs, strategic constraints, and geographic location. They further noted that variation in the types of menstrual products, how these products are provided, and quantity limits in each facility is to be expected. Officials stated that current standards are sufficient to ensure proper care for detainees and ensure needed menstrual products are available.

We maintain that while it is important to provide flexibility in operations, it is equally important to ensure that standards and policy are clear and adhered to. As we noted in our report, ICE’s detention standards lack the specificity to adequately assess the provision of menstrual products to detained individuals. For example, agency officials said their current inspection worksheet does not include questions that allow them to observe the details regarding the methods, types, and number of menstrual products that facilities provide. Inspection teams are limited in questions they ask about the provision of menstrual products because the detention standards lack specificity in this area. As such, inspection teams cannot adequately assess how and when menstrual products are provided and the type provided. Based on the non-specific standards and the limited inspection questions, officials are unable to adequately monitor the extent to which facilities provide sufficient menstrual products to individuals. Given the importance of detention center guidelines, the Director of ICE should revise the detention standards to clarify requirements related to the provision of menstrual products. This would improve DHS and ICE’s ability to monitor variation and ensure consistent and equitable access to menstrual products.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GoodwinG@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Gretta L. Goodwin

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Requesters

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Summer L. Lee

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Federal Law Enforcement

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jon Ossoff

United States Senate

The Honorable Yvette D. Clarke

House of Representatives

The Honorable Teresa Leger Fernández

House of Representatives

The Honorable Grace Meng

House of Representatives

The Honorable Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

House of Representatives

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

House of Representatives

You asked us to review the availability and accessibility of menstrual products for vulnerable populations, including incarcerated and detained individuals.[37] This report examines the extent to which (1) the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) provides access to menstrual products for incarcerated and detained individuals and (2) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) provides access to menstrual products for detained individuals.

To determine the extent to which BOP provides access to menstrual products for incarcerated and detained individuals, we conducted site visits to a nongeneralizable sample of five BOP institutions. During these visits, we observed what types of menstrual products—pads, tampons, panty liners—are provided, how they are provided, and when. We also observed where additional supplies of menstrual products are stored, such as storage closets and on-site warehouses. We selected BOP institutions to ensure variation in the number of women housed and security level. We also considered BOP institutions’ proximity to ICE facilities that house women. Finally, we considered which BOP institutions GAO teams had visited in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 to reduce burden on BOP institutions. We visited Federal Detention Center SeaTac, Federal Correctional Institution Marianna’s Satellite Prison Camp, Federal Correctional Institution Tallahassee, Metropolitan Detention Center Los Angeles, and Metropolitan Correctional Center San Diego. The evidence gathered from these site visits is not generalizable but provides examples of the types of menstrual products provided, as well as how and when officials at these locations provide access to menstrual products.

We also reviewed agency policy, guidance, and other documents related to the provision of menstrual products. For example, we reviewed the Female Offender Manual, which describes what menstrual products all BOP institutions that house women are required to provide and what restrictions, if any, may be placed on access to these products.[38] Further, we reviewed policies and procedures that guide how oversight groups within BOP are to assess the extent to which institutions adhere to agency policy, such as BOP’s Program Review Division’s internal audit process as well as documentation from these internal audits conducted in fiscal year 2024. We assessed the extent to which the agency’s monitoring activities were effectively operating to identify deficiencies.

Further, we deployed a web-based questionnaire to officials at all 29 BOP institutions across the U.S. and its territories that housed women in fiscal year 2024.[39] To identify the survey population, BOP provided us the names and points of contact for institutions that housed women in fiscal year 2024. The questionnaire included questions about the type of menstrual products available and at what cost, how BOP institutions made menstrual products available to incarcerated and detained individuals, and feedback that officials at each institution have received from incarcerated and detained individuals about menstrual products, among other topics. After we drafted the questionnaire, we asked for comments from subject matter experts within GAO. An internal survey specialist also completed a peer review of the questionnaire. We also sought comments from the Department of Justice. We made changes to the content and format of the questionnaire after both reviews.

Additionally, we conducted pretests to check that (1) the questions were clear and unambiguous, (2) terminology was used correctly, (3) the questionnaire did not place an undue burden on agency officials, (4) the information could feasibly be obtained, and (5) the questionnaire was comprehensive and unbiased. We selected six pretest sites within BOP to ensure variation in the number of women housed, institution type (for example, Federal Transfer Center, Secure Female Facility), and locations across a wide geographic area. We conducted pretests virtually, and we made changes to the content and format of the questionnaire after each of the pretests based on the feedback we received.

After finalizing the questions and format, we sent an e-mail announcement of the questionnaire to officials from the 29 BOP institutions. We also notified them via email when the questionnaire was available to be completed, and we sent follow-up e-mail messages to encourage those who had not yet responded to complete the questionnaire. In total, the questionnaire was available for 4 weeks for respondents to submit their responses. We received a response from officials at all 29 BOP institutions that house women, for a response rate of 100 percent. Appendix II provides all questionnaire responses from officials at the 29 BOP institutions.[40]

Moreover, we interviewed officials from BOP headquarters to understand how they designed policies related to the provision of menstrual products at their institutions. We also discussed how they oversee the extent to which institutions are implementing these policies. For example, we spoke with officials in BOP’s Program Review Division, Women and Special Populations Branch, Reentry Services Division, and Administration Division.

We also interviewed officials at five BOP institutions, as described above. In these interviews, we spoke with leadership at each location, such as the warden or their designee. Further, we also spoke with staff members responsible for selecting and procuring menstrual products, as well as employees who work with incarcerated and detained individuals on a regular basis, such as housing unit staff members and managers.

During our visits to BOP institutions, we also spoke with individuals who were incarcerated or detained about their experiences accessing, using, and disposing of menstrual products in these institutions. To select these individuals, prior to our visits, BOP provided de-identified rosters of the individuals housed in women’s units at each of our selected sites and their ages. We randomly selected 20 individuals ages 52 and younger to invite to speak to us during our visit. We also selected up to six alternate individuals at each location to invite if a selected individual was no longer at the institution when we arrived.

We provided BOP with a letter that described background information on GAO and on our review in both Spanish and English to provide to the selected individuals. In the letter, we indicated that their participation in an interview with us was voluntary, and they could choose to end the interview at any time. We also indicated that the interviews would be conducted in a private space, and that we would not disclose any identifying information about the individuals in our report. In total, we conducted interviews with 45 English- and Spanish-speaking incarcerated and detained individuals in BOP institutions.

We also held informal conversations with incarcerated and detained individuals during our tours of their housing units and common areas. We did not independently verify the veracity of all statements made by incarcerated and detained individuals, but we were sometimes able to corroborate their statements via direct observation or interviews with other staff or individuals. The information obtained during these formal interviews and informal conversations is not generalizable to all incarcerated and detained individuals, but it provides examples of the experiences of individuals incarcerated and detained in BOP institutions.

To determine the extent to which ICE provides access to menstrual products for detained individuals, we conducted site visits to a nongeneralizable sample of three ICE facilities. During these visits, we observed what types of menstrual products—pads, tampons, panty liners—are provided, how they are provided, and when. At one facility, we observed where they store additional supplies of menstrual products, such as storage closets and on-site warehouses. At the other two facilities, we discussed additional menstrual product storage areas with the facility leadership. We selected ICE facilities to ensure variation in the number of women housed and facility type.[41] We also considered ICE facilities’ proximity to BOP institutions that house women. We visited the Northwest ICE Processing Center in Tacoma, Washington; Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego, California; and Baker County Detention Center in Macclenny, Florida. The evidence gathered from these site visits is not generalizable but provides examples of the types of menstrual products provided, as well as how and when officials at these locations provide access to menstrual products.

We also reviewed agency policy, guidance, and other documents related to the provision of menstrual products. For example, we reviewed ICE’s detention standards for its detention facilities, such as the Performance Based National Detention Standards (revised 2016), among others. We also reviewed policies related to the provision of menstrual products from ICE facilities that housed women in fiscal year 2024. We also reviewed policy and procedures that guide how oversight groups within ICE are to assess the extent to which facilities adhere to agency policy or detention standards. We determined that the control activities component of internal control was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principle that management should implement control activities through policies.[42] We assessed the design of the agencies’ policies to determine whether they were documented in enough detail to allow management to effectively monitor the activity.

Further, we deployed a web-based questionnaire to officials at all 52 ICE facilities across the U.S. and its territories that housed women in fiscal year 2024.[43] To identify the survey population, ICE provided us the names and points of contact for facilities that housed women in fiscal year 2024. The questionnaire included questions about the type of menstrual products available and at what cost, how ICE facilities made menstrual products available to detained individuals, and feedback that officials at ICE facilities have received from detained individuals about menstrual products, among other topics. After we drafted the questionnaire, we asked for comments from subject matter experts within GAO. An internal survey specialist also completed a peer review of the questionnaire. We made changes to the content and format of the questionnaire after both reviews.