DEFENSE BUDGET

Clearer Guidance Is Needed to Improve Visibility into Resourcing of Pacific Deterrence Efforts

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-26-107698, a report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Diana Moldafsky at MoldafskyD@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

To counter China’s growing military reach, the U.S. military has been strengthening its forces in the Indo-Pacific. In 2021, Congress required annual budget reporting on Department of Defense funding for the region. However, there are concerns that the reporting does not provide the intended visibility into deterrence efforts and funding priorities in the region.

GAO Key Takeaways

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) annual Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) budget exhibits for fiscal years 2023 through 2025 do not consistently reflect department-wide priorities or requirements and present an inconsistent mix of programs and funding. Because guidance is not clear about how programs should be selected, we found inconsistencies in the types of programs included in the PDI budget exhibits. For example:

· The Air Force and Marine Corps selected facilities sustainment programs, while the Army and Navy did not.

· Some military services included efforts east of the International Date Line, although the guidance focuses on efforts primarily west of it.

· Some DOD organizations included development programs unlikely to be effective within 5 years—despite the guidance’s near-term focus.

Additionally, the programs and funding presented in the annual budget exhibit are different from those included in the Indo-Pacific Command’s (INDOPACOM) independent assessment, which is based on its strategy and assumes unlimited resources. While some of the differences can be attributed to that assumption, there are also differences in the types of funded programs prioritized. This raises questions about the extent of DOD’s resourcing needs for the Indo-Pacific region.

These inconsistencies make it difficult for Congress to assess whether DOD’s resources are aligned with strategic goals and increase uncertainty about which priorities DOD considers most critical for the region.

How GAO Did This Study

We reviewed DOD’s PDI budget exhibits from fiscal years 2023 through 2025 and conducted quantitative analysis of over 500 budget line items. We also conducted site visits to INDOPACOM and its supporting commands.

What GAO Recommends

We are making two recommendations to DOD: (1) that it revise its guidance to clarify how programs are selected for inclusion in the PDI budget exhibit and (2) that the PDI budget exhibit considers funded priorities identified by INDOPACOM. DOD concurred with our recommendations.

Abbreviations

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FDI |

European Deterrence Initiative |

|

EUCOM |

U.S. European Command |

|

FY |

Fiscal Year |

|

INDOPACOM |

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command |

|

NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

OUSD Comptroller |

Office of the Under Secretary

of Defense |

|

PDI |

Pacific Deterrence Initiative |

|

RDT&E |

Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 25, 2025

Congressional Committees

To enhance U.S. deterrence and defense posture in the Indo-Pacific theater and increase capability and readiness in the region, Congress required the Department of Defense (DOD) to establish the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI).[1] PDI includes reporting requirements for the DOD to submit to Congress: 1) an annual detailed budget exhibit for the initiative, and 2) an annual independent assessment by the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) on the resources required.[2] These requirements are intended to provide Congress greater visibility into the resources required for the joint force in the Indo-Pacific region. However, the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 expressed the view that the annual PDI budget exhibit did not provide the visibility intended, stating that it was not properly focused on improving the joint posture and enabling capabilities necessary to enhance deterrence in the region.[3] PDI has similar characteristics as the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), which was established in 2014 to deter Russian military aggression in Eastern Europe and assure U.S. allies in that region.[4]

The conference report accompanying the NDAA for FY 2024 contains a provision for us to conduct a review of PDI, including DOD’s process for creating the PDI budget exhibit and a comparison of PDI to EDI.[5] In this report, we 1) assess the extent to which DOD’s selection of programs for PDI provides visibility into resourcing for the joint force in the Pacific and 2) describe how DOD’s implementation and direction for PDI compared to EDI.

To address these objectives, we reviewed DOD guidance and budget documentation related to PDI, including department-wide criteria for selecting programs for inclusion in annual budget exhibits. We analyzed data from the FY 2023 through FY 2025 PDI budget exhibits to determine whether there were any inconsistencies in program selection.[6] We also conducted data testing and interviewed officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Comptroller (OUSD Comptroller) about the data. We determined the PDI budget exhibit data was sufficiently reliable for evaluating whether the data provide sufficient visibility into the resourcing of the joint force in the Pacific. We conducted quantitative analysis of over 500 line items from the PDI budget exhibits on the types of programs and funding reflected in the budget exhibits. We interviewed financial management and budget officials from the military services, Joint Staff, relevant Offices of the Under Secretaries of Defense, and INDOPACOM to understand their roles and processes for selecting PDI programs to include in the budget exhibit. We also conducted in-person site visits to INDOPACOM headquarters and sub-commands to gather additional perspectives on PDI program selection.

To assess DOD’s process to select PDI programs, we compared the information described above to the PDI statute, as amended, and internal control principles outlined in GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[7] Specifically, we determined the information and communication component and underlying principles on quality information and internal communication were relevant to our review. To compare PDI to EDI, we also reviewed DOD policy on EDI and interviewed officials from U.S. European Command (EUCOM) to understand DOD’s implementation and combatant command direction for each of these initiatives. Appendix I provides additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to November 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DOD Budgeting Process

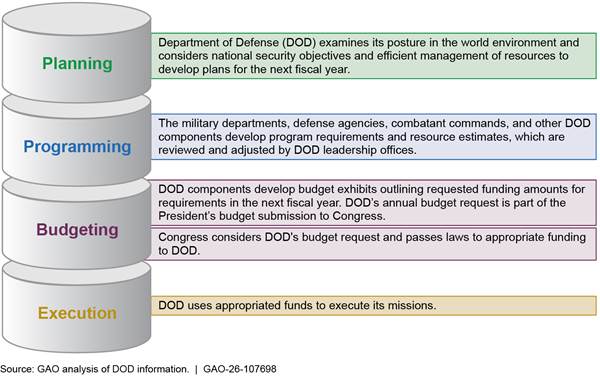

Each year, DOD decides how much funding to request through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process (see fig.1). During the budgeting phase of this process, DOD components develop budget exhibits outlining requested funding amounts (i.e. budget estimates) for requirements in the next fiscal year.[8] The PDI budget exhibit displays budget estimates by budget line item and program element number (hereafter referred to as programs).

Note: For the purpose of this review, DOD components include, but are not limited to, the military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps), combatant commands which are responsible for certain geographic or functional areas (e.g., U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. European Command, and Cyber Command), and other organizations such as the Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Space Force is not included in the PDI budget exhibits and has been excluded from our review.

DOD receives funds through different types of appropriation accounts, which may be used only for their intended purposes, and for fixed-period appropriations, only for a defined period of time. See table 1 for examples of the funding discussed in this report.

Table 1: Select Types of DOD Appropriation Accounts

|

Appropriation Account |

Period of availability |

Purpose |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

1 year |

For military service and department-wide expenses, including maintenance services, civilian salaries, Facilities Sustainment Restoration and Modernization, operating military forces, training and education, and other base operations support. |

|

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) |

2 years |

For expenses necessary for basic and applied scientific research, development, test and evaluation, including maintenance, rehabilitation, lease, and operation of facilities and equipment. Amounts generally fund the scientific research and military development of new technologies and also the normal operation and maintenance expenses of DOD components that engage in such work. |

|

Procurement |

3+ years |

For expenses necessary for the procurement, manufacture, and modification of missiles, armament, military equipment, spare parts, and accessories, plant equipment, appliances and machine tools, and installations in public and private plants, among other expenses. |

|

Military Construction |

5 years |

For acquisition, construction, installation, and equipment of temporary or permanent public works, military installations, facilities, and real property. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) budget information. | GAO‑26‑107698

Note: DOD has a fifth appropriation account for Military Personnel costs, which funds salaries, compensation, and related expenses for military personnel. These costs are excluded from the Pacific Deterrence Initiative budget exhibit.

PDI Reporting Requirements

PDI is not a separate funding source or appropriation. DOD implements PDI as two annual reports: 1) the DOD PDI budget exhibit, which is a compilation of budget estimates for a subset of budgeted programs that DOD components determined to have met the criteria for PDI, and 2) an annual report, known as the independent assessment, from INDOPACOM on the programs and other required resources the INDOPACOM Commander considers critical to U.S. deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.[9]

To develop the PDI budget exhibit, DOD components select qualifying programs based on department-wide guidance, which according to officials from Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (OUSD Policy), was drafted by and coordinated through their office in support of the Deputy Secretary of Defense. Specifically, in March 2022, the Deputy Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum (hereafter referred to as DOD’s PDI guidance) detailing the criteria for including or excluding programs from the PDI budget exhibit.[10] The guidance states the following:

· Components should include activities that enhance U.S. force posture, infrastructure, presence, and readiness in the Indo-Pacific region primarily west of the International Date Line. The PDI statute also states that PDI should focus on activities west of the International Date Line.[11]

· Included programs should generate substantial deterrence effects within 5 years.

· Components should identify any funding that provides allies and partners with enhanced deterrence capacity or capability west of the International Date Line.

· Components should not include activities that are 1) designed to address broader strategic threats, 2) easily transferrable between regions, or 3) routine activities and exercises that DOD would undertake regardless of China’s growing threat.

The guidance also gives examples of programs to include or exclude, for example including Guam missile defense and excluding Facilities Sustainment Restoration and Modernization.[12]

According to OUSD Comptroller officials, components first select programs for inclusion in the PDI budget exhibit; these selections are made in their individual budget systems.[13] Then, during the budgeting phase of the planning, programming, budgeting, and execution process, OUSD Comptroller compiles data from all the components on the selected programs to create the PDI budget exhibit.

The PDI budget exhibit is organized into the following six categories:

· Modernized and Strengthened Presence

· Improved Logistics, Maintenance Capabilities, and Prepositioning

· Exercises, Training, Experimentation, and Innovation

· Infrastructure Improvements to Enhance Responsiveness and Resiliency of U.S. Forces

· Building Ally/Partner Capabilities, Capacity, and Cooperation

· Improving Capabilities Available to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command

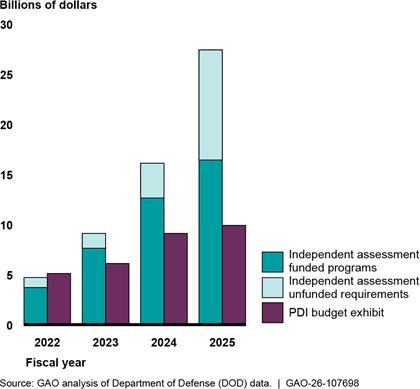

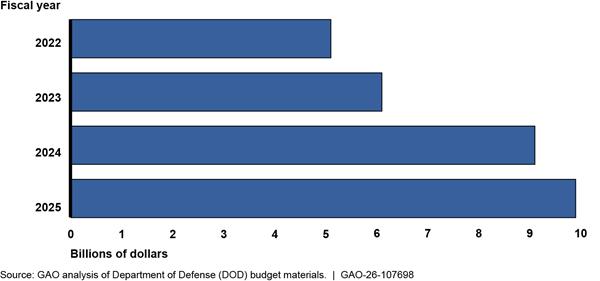

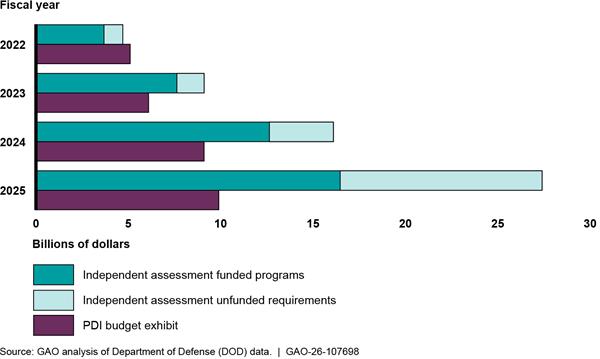

In total, DOD has identified approximately $30 billion for PDI since 2021, as shown in figure 2 below.[14]

Figure 2: Pacific Deterrence Initiative Total Budget Estimates, Fiscal Years 2022–2025 (in then-year dollars)

Officials said that INDOPACOM’s independent assessment is developed separately from the budget exhibit and highlights priority programs based on its strategy for the Indo-Pacific. As a geographic combatant command, INDOPACOM is responsible for coordinating and directing all military operations and activities in the Indo-Pacific region. INDOPACOM is supported by sub-commands from each military service.[15]

The PDI statute requires that the Independent Assessment identify the activities and resources required to 1) implement the National Defense Strategy with respect to the Indo-Pacific region, 2) maintain or restore comparative military advantage of the United States with respect to China, and 3) reduce the risk of executing contingency plans of the Department of Defense.[16]

INDOPACOM officials said that the basis for the Independent Assessment is the Commander’s strategy for the region. Based on the needs for that strategy, INDOPACOM subject matter experts identify priority programs for inclusion in the Independent Assessment. The officials identify both funded programs (i.e. programs that have been validated for funding through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process) as well as unfunded programs (programs that were not validated). INDOPACOM officials create budget estimates they think are needed for the programs to fulfill their requirements. The Independent Assessment is not subject to DOD’s PDI guidance but is organized in the same categories used for the PDI budget exhibit.

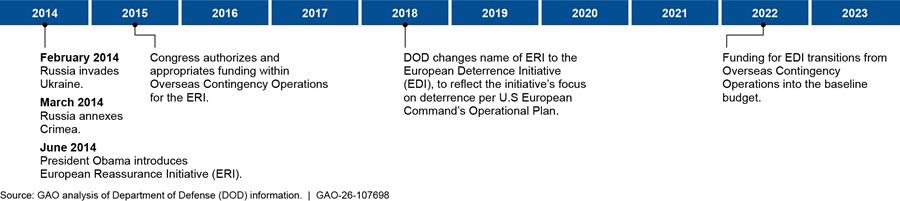

European Deterrence Initiative (EDI)

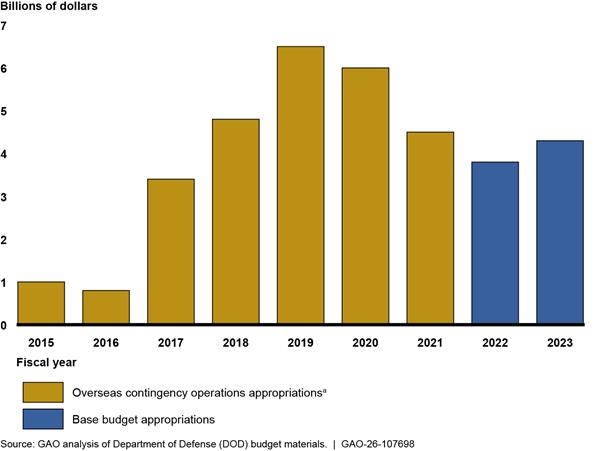

The executive branch established EDI in 2014, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, to assure North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies and deter further Russian aggression.[17] Unlike PDI, EDI was implemented as a program with dedicated funding, which enabled DOD to prioritize resources and enhance U.S. deterrence posture in Europe. From FY 2015 through FY 2021, amounts for EDI were provided through Overseas Contingency Operations appropriations.[18] In FY 2022, DOD stopped requesting amounts for EDI as part of Overseas Contingency Operations, and shifted its EDI funding requests into the base budget request. DOD organized EDI activities into five lines of effort: (1) Increased Presence, (2) Exercises and Training, (3) Enhanced Prepositioning, (4) Improved Infrastructure, and (5) Building Partnership Capacity. Figure 3 describes the evolution of EDI since 2014.

Our prior work found that EDI supported increased U.S. force presence and infrastructure improvements in Europe.[19] For example, EDI enhanced the presence of U.S. military forces throughout Europe—leading to increased numbers of rotational forces deployed to the region and increased levels of exercises conducted by those forces. Further, EUCOM and U.S. Army Europe officials told us that prior to EDI, the military services had limited forces rotating through Europe to supplement permanently stationed forces. EDI also helped establish defense cooperation agreements with several European countries, which enabled DOD to implement posture changes and make physical infrastructure improvements at various military bases and other facilities.

However, our past work also identified deficiencies related to how DOD monitored EDI performance. In 2023, we recommended that DOD establish performance measures for EDI to better position the department to assess EDI activities, support budget requests, and justify resource decisions.[20] DOD did not concur with this recommendation, stating at the time that EDI was no longer a distinct program or separate funding source and that it would be inappropriate to develop standalone performance measures.

Inconsistent PDI Program Selection and Priorities Limit Visibility into Resourcing for the Joint Force in the Pacific

DOD’s FY 2023 to FY 2025 PDI budget exhibits do not consistently reflect department-wide priorities or INDOPACOM’s requirements. The military services and other DOD components applied selection and review processes differently, leading to inconsistencies in the types of programs included in the budget exhibit. In addition, DOD’s PDI budget exhibit and INDOPACOM’s independent assessment identify different sets of priorities, complicating Congress’s visibility into priorities for resourcing the joint force in the Pacific.

DOD Components Inconsistently Select Programs for the PDI Budget Exhibit

DOD components applied PDI selection and review processes differently from one another, leading to variation in the types of programs included in the FY 2023 through FY 2025 budget exhibits. The military services varied in how they involved their Indo-Pacific sub-commands in the process. We found that the variations in how PDI programs were selected across the department contributed to broader inconsistencies in how components implement parts of the PDI guidance.

Enhanced forces and programs. According to DOD’s PDI guidance, DOD components should include programs that enhance U.S. force posture, infrastructure, presence, and readiness.[21] The Marine Corps selected most of its forces in the Indo-Pacific region for the PDI budget exhibits, while the Army and Air Force only selected certain forces, and the Navy selected virtually none of its forces. The guidance does not define “enhance,” leading components to interpret it differently. For example:

· Navy officials said they have never selected their Pacific surface or subsurface fleet for any of the PDI budget exhibits because these are existing forces that the Navy was already funding prior to PDI. Similarly, the Air Force did not select its major military units in the Pacific, although it did select programs that it determined “enhanced” those forces, such as aircraft modernization.[22]

· Conversely, the Marine Corps had a different interpretation of this PDI guidance, and thus selected the III Marine Expeditionary Force in Okinawa for all PDI budget exhibits DOD has submitted since 2023. According to the Marine Corps, III Marine Expeditionary Force activities contribute to day-to-day forward-deployed military activities necessary for integrated deterrence efforts against China and thus meet the intent of PDI.

· INDOPACOM selected certain headquarters’ programs, such as its headquarters staff, for the PDI budget exhibits.[23] However, the headquarters programs for the military services’ sub-commands that support INDOPACOM were not selected. According to officials from the military services, they did not consider such programs to be eligible for PDI because they are existing activities that they have undertaken for years rather than enhancements.

· The Joint Staff selected its exercise program and associated funding for exercises in the Indo-Pacific region, although two of those exercises predate PDI and thus may not be enhancements as defined by other components.

Budget and financial management officials from the U.S. Army Pacific, Pacific Air Forces, and Marine Corps Forces Pacific said that more programs could be selected for PDI. However, they also said they have limited roles and input in their components’ selection processes, including how the components define enhancements. For example, Pacific Air Forces officials said they do not have a role or input into PDI selections made by the Air Force. Officials from U.S. Army Pacific said that they believe PDI should be more inclusive of some of the exercises and forward presence activities undertaken by their forces, regardless of whether they are enhancements.

RDT&E programs. Similarly, DOD components were not consistent in their selections of RDT&E programs in the PDI budget exhibit. DOD’s PDI guidance states that in general selected programs should generate substantial deterrence effects within 5 years, with some exceptions. According to military service officials, RDT&E programs may not meet this criterion because their technology may not be operationally ready within 5 years. However, the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s Strategic Capabilities Office and Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve, two RDT&E offices, selected their own programs for PDI because, according to officials, they focus on deterring China. The Army selected RDT&E programs related to the defense of Guam, which is cited in DOD’s PDI guidance as an exception to the 5 years criteria noted above. Comparatively, the Navy and the Air Force selected lower amounts of RDT&E program funding, while the Marine Corps selected none, as shown in table 2. Officials from the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps acknowledged the different interpretations of PDI criteria in these selections.

Table 2: Budget Estimates for Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) Programs in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative Budget Exhibit, by Component

Budget estimates in then-year dollars in millions, fiscal years (FY) 2023–2025

|

DOD component |

FY 2023 |

FY 2024 |

FY 2025 |

|

Office of the Secretary of Defense |

$1,008 |

$981 |

$1,035 |

|

Missile Defense Agency |

$473 |

$632 |

$699 |

|

U.S. Cyber Command |

N/A |

$29 |

$24 |

|

Army |

$413 |

$853 |

$557 |

|

Navy |

$16 |

$20 |

$26 |

|

Air Force |

N/A |

$66 |

$2 |

|

Marine Corps |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Source: GAO analysis of PDI budget exhibits. | GAO‑26‑107698

Note: N/A (not applicable) indicates that the given component did not select RDT&E programs in the given fiscal year. Budget estimates for the Office of the Secretary of Defense include the Strategic Capabilities Office and the Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve.

According to officials from U.S. Cyber Command, they were directed to include certain Indo-Pacific funding in PDI, but they have no process to review their budget to identify other programs that might qualify. According to officials from Marine Corps Forces Pacific, they believe some of their RDT&E programs should be selected for PDI. However, they are not directly involved in the selection process, which is centralized in their Programs and Resources Department.

Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization. DOD components also varied in the extent to which they selected Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization programs in the PDI budget exhibit. DOD’s PDI guidance cites Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization as an example of the types of programs that should be excluded from the PDI budget exhibit. However, the Air Force and the Marine Corps included these programs in their FY 2023 to FY 2025 budget exhibits. Air Force and Marine Corps officials said they believe these programs qualify for PDI based on a section of the PDI guidance that allows inclusion of programs enhancing the resilience of existing bases—a concept that is not further defined in DOD’s PDI guidance. In contrast, Navy officials said they excluded similar programs because they interpreted the guidance as discouraging inclusion of routine sustainment activities. These differing interpretations resulted in inconsistent inclusion of facilities sustainment-related programs across PDI’s budget exhibits, as shown in table 3.

Table 3: Budget Estimates for Facilities Sustainment Programs in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative Budget Exhibit, by Component

Budget estimates in then-year dollars in millions, fiscal years (FY) 2023–2025

|

DOD component |

Budget line items |

FY 2023 |

FY 2024 |

FY 2025 |

|

Air Force |

Facilities Sustainment, Restoration & Modernization |

$8 |

$213 |

$194 |

|

Marine Corps |

Sustainment, Restoration & Modernization |

$127 |

$98 |

$116 |

|

Army |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Navy |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Source: GAO Analysis of PDI Budget Exhibits. | GAO‑26‑107698

Note: N/A (not applicable) indicates that the given component did not select facilities sustainment programs in the given FY. The funding amounts selected by Air Force and Marine Corps were operation and maintenance budget estimates.

According to officials from headquarters budget offices from the Army and the Navy, they do not have processes to annually review their PDI selections. They said that they believe the programs they initially selected for PDI remain valid for subsequent PDI budget exhibits and would only reevaluate if they were asked to do so by DOD leadership or Congress.

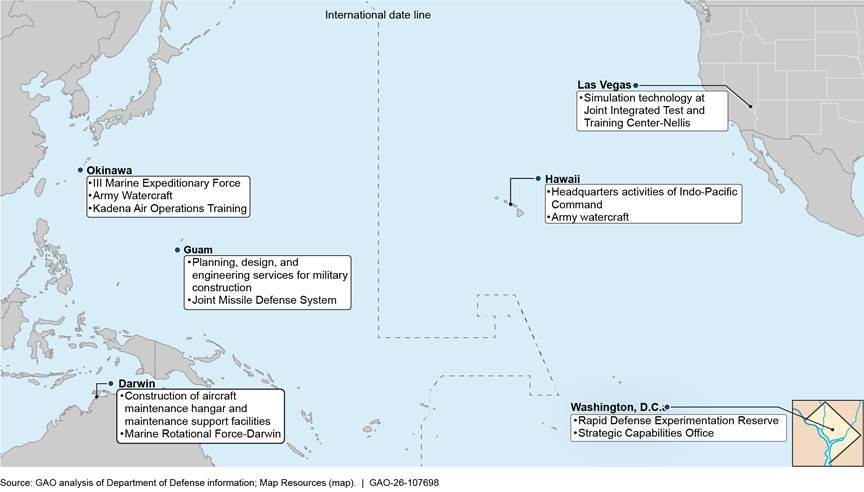

Geographic location. Some PDI program selections do not clearly align with the statutory requirement to prioritize efforts west of the International Date Line. Figure 4 shows the approximate location of selected programs, including some located east of the line.

Figure 4: Approximate Locations of Select Programs Included in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) Budget Exhibit

Note: Though headquartered in the Washington, D.C. area, officials for the Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve and the Strategic Capabilities Office said that their programs were spread throughout the continental United States. The capabilities they were developing were expected to be deployed west of the International Date Line. The programs shown do not represent all years of PDI budget exhibits.

The NDAA for FY 2021, which established PDI, indicated that the initiative should prioritize activities to improve the design and posture of the joint force in the Indo-Pacific region, primarily west of the International Date Line.[24] DOD’s PDI guidance states that components should select activities for the budget exhibit that are primarily west of the International Date Line, without providing any further clarification as to what is meant by “primarily.” As a result, DOD components, to varying degrees, have selected programs and forces east of the International Date Line. For example:

· The Air Force selected certain programs to enhance training infrastructure at its major training site in Nevada and Alaska, which are east of the International Date Line. According to Air Force officials, their interpretation is that enhancements of these training areas improve the training and readiness of their forces that are west of the International Date Line and thus qualify them for inclusion in the PDI budget exhibit.

· The Army selected forces stationed in the continental United States that temporarily deploy west of the International Date Line.[25] The Navy did not select such forces.

· The Marine Corps, which centralizes its selection process at the headquarters level, also annually selected its forces that temporarily deploy west of the International Date Line. However Marine Corps Pacific officials said that that the budget exhibit mainly contains the budget estimates related to costs incurred west of the International Date Line. These officials believe that interpretation of the guidance is too strict, as it generally excludes costs they incur preparing for the rotation and maintenance and repair costs incurred after the rotation because these costs occur east of the International Date Line.[26]

Army officials said they could not authoritatively confirm that certain activities were west of the International Date Line, although they believed that they were. Moreover, Army headquarters officials were not sure which office was responsible for PDI selections. Army headquarters’ Congressional Budget Liaison Office provided responses to our questions, but also stated that they were not directly responsible for PDI selections.

The NDAA for FY 2021 directed DOD to annually prepare a PDI budget exhibit, and the accompanying conference report called for correctly organized budgetary data for budgetary transparency and to inform Congress’ oversight responsibilities.[27] The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the NDAA for FY 2022 further emphasized Congress’ use of the PDI budget exhibit, noting the importance of identifying baseline activities and initiatives so Congress can evaluate year-over-year trends.[28] Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government emphasize the need for oversight bodies to receive quality information and note that management should design processes and identify information requirements to ensure the use of quality information.[29]

DOD issued the 2022 PDI guidance to implement the PDI legislation, but according to our analysis and headquarters officials from the military services, several aspects are vague and contradictory. For example, the guidance does not define what constitutes an “enhancement,” though it suggests excluding activities—such as routine operations—that DOD would undertake regardless of the rising threat from China. Military service officials noted that such distinctions are difficult to make now that China is the Department’s pacing threat. The guidance also requires selected programs to have deterrence effects within 5 years, leading to inconsistency in how components selected RDT&E programs. In addition, while the guidance suggests excluding Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization programs, it also contains criteria that some components interpret as allowing their inclusion. Finally, the guidance states that selected programs should be “primarily” west of the International Date Line, but does not define “primarily”, resulting in the inclusion of some programs east of the line depending on the interpretation of the DOD component.

The guidance also does not specify (1) the office within each component that should be responsible for selecting PDI programs (2) how comprehensively components should review their overall budget submissions to identify PDI-eligible programs, or (3) which other offices should be involved. For example, officials from the military services’ Indo-Pacific sub-commands provided us examples of additional program funding that could be included in the PDI budget exhibits but was not because the military services did not consult with these sub-commands as they developed the budget exhibits. Officials from one sub-command provided this input to its service headquarters, but the input was not incorporated. Officials from OUSD Policy and OUSD Comptroller acknowledged these issues and said it would be beneficial to have better defined PDI selection processes.

While officials from OUSD Comptroller and OUSD Policy acknowledged that the PDI guidance could be refined, they also noted that the PDI statute does not define certain criteria, such as “primarily” west of the International Date Line, and it does not address other issues such as the definition of enhancements or the inclusion of Facilities Sustainment Restoration and Modernization. In July 2025, Senate Report 119-39, which accompanies a bill for the NDAA for FY 2026, proposes clarity on these issues and others. For example, the Senate Report states that DOD should annually include operation and maintenance budget estimates for all operational forces and supporting enablers west of the International Date Line. The Senate Report also addresses the inclusion of Facilities, Sustainment, Restoration, and Modernization programs and other issues.[30]

The gaps we identified in clarity and coordination make it difficult to assess whether growth in PDI budget estimates reflect real growth in funding attributed to new priorities and enhanced programs or whether it is simply due to broader program selection over time. For example, the total budget estimates for programs selected for PDI in FY 2025 were nearly $9.9 billion, an increase of approximately 94 percent compared to the initial FY 2022 PDI budget exhibit. According to DOD officials, it is unreasonable to expect that PDI funding levels should remain steady or increase year over year given the eventual end dates for certain types of programs. For instance, when DOD completes Military Construction and Procurement programs the associated budget estimates are no longer listed in DOD’s annual budget and PDI totals would likely decrease.[31] These expected fluctuations make it critical for DOD to select and review PDI programs methodically—so Congress receives reliable information regardless of year-to-year funding changes.

Without clarifying its guidance in the areas we found discrepancies, and without establishing clear roles and processes for selecting programs for PDI, DOD cannot ensure the PDI budget exhibit provides Congress with a complete and accurate picture of how it is resourcing the joint force in the Indo-Pacific. This reduces budget transparency and Congress’s ability to exercise its oversight responsibilities.

The PDI Budget Exhibit Presents Different Priorities Than the Independent Assessment

DOD’s PDI budget exhibit presents different priorities than the INDOPACOM independent assessment, which presents the requirements for INDOPACOM’s strategy in the region and is based on an assumption of unconstrained resources. For example, the FY 2025 INDOPACOM independent assessment included programs totaling $26.5 billion, while the PDI budget exhibit included programs totaling $9.9 billion. Figure 5 compares the total budget estimates from FY 2022 through FY 2025 in the PDI budget exhibits and the INDOPACOM independent assessments.

Figure 5: Comparison of Budget Estimates in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) Budget Exhibits and the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) Independent Assessment, Fiscal Years 2022–2025

Note: INDOPACOM assumed it had unconstrained resources in its estimates. It therefore included program requirements that were not validated for funding through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process, and were thus not included in the DOD budget.

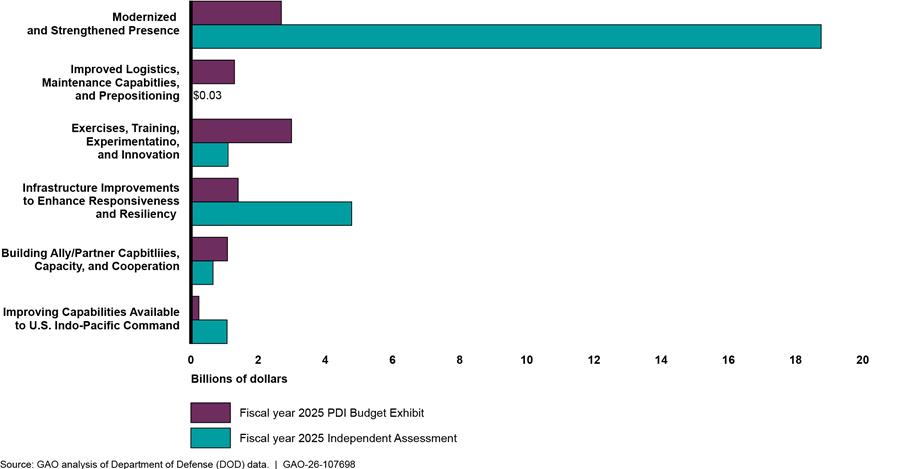

Figure 6 shows the differences in total budget estimates, by PDI category, in the FY 2025 PDI budget exhibit versus the FY 2025 INDOPACOM independent assessment

Figure 6: Comparison of Budget Estimates in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) Budget Exhibit and the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) Independent Assessment, by PDI Category, Fiscal Year 2025

Note: INDOPACOM assumed it had unconstrained resources in its estimates. It therefore included program requirements that were not validated for funding through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process, and were thus not included in the DOD budget.

According to INDOPACOM officials, the different budget estimates are partly due to how INDOPACOM included programs in its independent assessment. INDOPACOM assumed it had unconstrained resources in its estimates. It therefore included program requirements that were not validated for funding through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process, and were thus not included in the DOD budget. Congress has periodically provided funding for some of these unfunded requirements, even though they are not reflected in DOD’s budget request.[32]

INDOPACOM and OUSD Comptroller officials told us that the differences also stem from INDOPACOM’s independent assessment containing more funded programs than the PDI budget exhibit.[33] Specifically, INDOPACOM officials stated that many funded and budgeted requirements they deem necessary for their strategy, and thus include in the independent assessment, were not reflected in the PDI budget exhibits. For example, INDOPACOM’s independent assessment includes research and development programs for next generation national defense space architecture, which is a special access program totaling $1.3 billion in FY 2025. These programs are not included in the PDI budget exhibit because DOD’s PDI guidance suggests that, among other things, special access programs should be excluded, as well as programs that address broader strategic threats.[34] The Independent Assessment also includes $940 million in budget estimates for the Air Force and Navy’s Long Range Anti-Ship Missile. DOD’s PDI guidance suggests that munitions should be excluded from PDI budget exhibit. Additionally, INDOPACOM officials also acknowledged that some of the programs in the PDI budget exhibit are not in the INDOPACOM independent assessment. For example, the independent assessment does not include the Army watercraft program, which consisted of over $250 million in budget estimates in the PDI budget exhibits from FY 2023 to FY 2025.

DOD’s guidance on its budgeting process stresses aligning resources to prioritized capabilities based on an overarching strategy and implementing fiscally sound decisions in support of the National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy.[35] The Commission on Planning, Programming, Budget, and Execution Reform emphasized the need for better alignment between budget decisions and strategic priorities, urging DOD to overcome traditional divides between service requirements and those of the combatant commands.[36] DOD’s January 2025 Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Reform Implementation Plan noted several related objectives, including reinforcing the alignment between strategy and budgeting and improving communication of budget priorities to Congress.[37]

The PDI budget exhibit and INDOPACOM’s independent assessment present different priorities because they are developed in separate processes that do not involve consideration of funded programs identified in the independent assessment for inclusion in the PDI budget exhibit. INDOPACOM does select some of its own programs for the PDI budget exhibit. However, in the independent assessment, INDOPACOM includes programs from other DOD components that would only be included in the budget exhibit if those responsible components selected them. Officials from OUSD Comptroller, OUSD Policy, and INDOPACOM emphasized that some of the differences between the two documents relate to INDOPACOM’s inclusion of unfunded programs. However, the officials also acknowledged that to improve transparency to Congress, the budget exhibit could be better aligned with the independent assessment in terms of programs that have been validated for funding through DOD’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process.

Without updating the PDI budget process to ensure that funded programs highlighted by the independent assessment are also considered for the PDI budget exhibit, DOD risks sending mixed messages to Congress about the extent of its resourcing needs in the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, this misalignment may undermine DOD’s objectives for strategy-driven budgeting, create uncertainty about the totality of funded requirements in the Indo-Pacific, and complicate oversight—making it harder for Congress to assess whether resources are aligned with strategic goals for the joint force in the Pacific.

DOD Implemented and Directed PDI and EDI Differently

DOD implemented and directed PDI and EDI differently due to several factors, including the availability of funding and the regional contexts in which these programs were implemented. DOD developed different criteria to guide how each initiative reported to Congress, and INDOPACOM and EUCOM also played different roles in each initiative.

EDI Benefitted from Direct Funding and Unique Strategic Context

DOD officials said that PDI and EDI are different, with variation in the strategic context under which each initiative was created and the use of overseas contingency operations funding for EDI. From FY 2015 through FY 2021, DOD reported EDI programs and activities were funded through approximately $27 billion in overseas contingency operations appropriations. EUCOM officials said that overseas contingency operations appropriations for EDI allowed EUCOM to use EDI to prioritize activities that improved U.S. posture in Europe without competing for funding with other military service or department-wide priorities.

In our prior work, we reported that EUCOM and U.S. Army Europe officials told us that funding for EDI enabled the military to provide capabilities to the European region, accelerate existing projects, and support projects that might not have been funded through DOD’s base budget.[38] DOD transitioned EDI into the base budget in FY 2022 and EDI no longer receives overseas contingency operation appropriations.[39] Figure 7 shows EDI enacted amounts from FY 2015 through FY 2023.

aThis figure depicts enacted appropriated amounts for EDI as identified by DOD. From FY 2015 through FY 2021, overseas contingency operations appropriations provided funding for EDI. During this time period, EDI did not receive any base funding, although DOD continued to receive base budget funding for its existing programs in the European theater. In FY 2022 and FY 2023, funding for EDI was integrated into DOD’s base budget appropriations. DOD requested approximately 3.6 billion in FY 2024 and 2.9 billion in FY 2025 for EDI.

In contrast, PDI has not received any supplemental or dedicated appropriations from Congress, according to DOD officials. Officials from the military services said that without supplemental appropriations, PDI is implemented primarily as an accounting tool for Congressional reporting and is not used to prioritize resources or programs in the Indo-Pacific. Instead, OUSD (Comptroller) officials said that DOD uses its annual programming and budget review processes to identify and prioritize resources for the Indo-Pacific, which are then reflected in the PDI budget exhibit.

U.S. Army Pacific officials also said that EDI benefited from existing infrastructure and partnerships in Europe, such as NATO and related agreements. In 2023, we found that the defense cooperation agreements that DOD established with several European countries, such as Norway and Poland, enabled it to make additional posture changes in the European region through EDI.[40] Further we reported that the U.S. military used EDI to enhance force presence in Europe.

In contrast, U.S. Army Pacific officials said that DOD is still in the early stages of building major infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific, such as the military build-up in Guam.[41] While the United States has a series of strong bilateral alliances in the Pacific, officials from U.S. Army Pacific said it lacks a strong multinational security cooperative like NATO. The officials said this affects DOD’s ability to have consistent presence in the Indo-Pacific, including facilities for personnel and resources needed to execute PDI related activities.

Both Initiatives Implemented Distinct Criteria to Develop Budget Exhibits for Congress

Similar to PDI, EDI’s programs and associated funding were reported to Congress in a separate budget exhibit.[42] EUCOM officials said that when overseas contingency operations appropriations for EDI ended, the department took steps to more clearly define criteria for the types of programs that would be included in its EDI budget exhibit. In February 2023, the Deputy Secretary of Defense issued guidance outlining criteria for the selection of programs that supported EDI’s lines of efforts.[43] The criteria were intended to enable DOD components to identify programs and funding that aligned with deterring Russian aggression against NATO and thus should be reported in the EDI budget exhibit. DOD developed the EDI criteria using a similar format to its PDI guidance, according to EUCOM officials.

The PDI and EDI guidance is similar, but there are key differences in what types of programs DOD selected for inclusion in each budget exhibit. Per the guidance for each initiative, DOD components included programs in both PDI and EDI related to infrastructure and military construction, exercises and training, information sharing, and air and missile defense in their respective budget exhibits. However, unlike PDI, EDI’s guidance also allowed selection of certain military and civilian personnel costs and munitions.[44] Figure 8 compares activities included and excluded in PDI and EDI, per the criteria established for each initiative.

Figure 8: Comparison of Activities Included in the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) and the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI)

Notes: This figure compares included and excluded activities for PDI and EDI, based on the DOD criteria established for each initiative. Per the initiative’s criteria, PDI is generally focused on funding that enhances capabilities or capacity to deter China primarily west of the International Date Line. Building Partner Capacity generally involves the use of security cooperation authorities to build resilience, capacity, or capability of allies and partners.

Although PDI and EDI have implemented similar criteria to select programs, OUSD Comptroller officials said that more new or existing programs are tagged for inclusion in PDI each year compared to EDI. Based on the criteria established in guidance discussed earlier in this report, OUSD Comptroller officials said that components continue to add new budget estimates to the PDI budget exhibits, and the amount of requested funding included has generally increased each year since the initiative began. In contrast, EUCOM officials said that EDI had significantly scaled down since its FY 2022 transition to the base budget. EUCOM officials said that following this transition, DOD components rarely added new programs to the EDI budget exhibits, and the overall amount of requested funding included in the exhibits decreased each year.

EUCOM Played a Larger Role in EDI Than INDOPACOM Does in PDI

EUCOM played a larger role in directing the development of EDI budget exhibits compared to INDOPACOM’s role in PDI. EUCOM officials said that EUCOM developed the EDI budget exhibit each year in coordination with OUSD Comptroller.[45] DOD components and the military services identified programs as EDI in their respective budget systems, and EUCOM pulled this information to develop the exhibit. EUCOM, with military service input, also categorized selected programs under EDI’s five lines of effort and assisted in developing narrative descriptions for included programs.[46] Although EUCOM compiled the EDI budget exhibits, DOD components and the military services decided what programs or activities were included as part of the EDI initiative.[47]

In contrast, the PDI budget exhibit is developed by DOD components. DOD components have varying processes for selecting programs for the PDI budget exhibit. INDOPACOM officials said that the command provides input on its command-specific budget estimates through the Navy. However, as discussed earlier in this report, officials said that INDOPACOM plays a limited role in reviewing the PDI budget exhibit, including program selections made by other DOD components. Instead, INDOPACOM communicates required resources, as identified by the INDOPACOM Commander, through its annual independent assessment.

According to OUSD Comptroller officials, to align with priorities of the new administration, DOD did not develop an EDI budget exhibit as part of its FY 2026 budget request. The officials said that EDI related requirements are captured as part of the components’ overall base budget request in FY 2026, and that DOD continues to engage in the European region as directed by the Department’s strategic guidance.

Conclusion

PDI reporting requirements were designed to give Congress greater insight into how DOD is prioritizing and resourcing the joint force in the Indo-Pacific region. However, inconsistent program selection has limited visibility and weakened the initiative’s value. These issues stem, in part, from DOD’s unclear internal guidance on how to select programs for inclusion in the PDI budget exhibit. In addition, DOD’s PDI budget exhibit and INDOPACOM’s independent assessment are developed in separate processes that preclude consideration of some programs selected by INDOPACOM for inclusion in the budget exhibit. The result is a budget exhibit that may not reflect all the funded program priorities that INDOPACOM needs for its regional strategy. Unless DOD improves its internal processes and clarifies what the PDI exhibit is intended to convey, Congress will continue to face challenges in using it to assess progress toward deterrence and posture objectives in the Indo-Pacific region. Addressing these issues would help ensure the PDI budget exhibit provides clear, consistent and credible information on how the department is aligning resources to increase capability and readiness in the Indo-Pacific.

Recommendations

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense (Policy) revises DOD’s guidance on PDI to clarify program selection criteria—including those related to enhancements, RDT&E programs, facilities sustainment, and geographic location—and to establish processes, including roles and responsibilities, for selecting and validating PDI programs. [Recommendation 1]

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under

Secretary of Defense (Policy), in coordination with INDOPACOM, updates PDI

processes to ensure that DOD reviews and considers INDOPACOM’s funded

priorities for inclusion in the annual PDI budget exhibit.

[Recommendation 2]

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, DOD concurred with our recommendations and identified steps it would take to address them. DOD also provided a technical comment which we fully incorporated in the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, Secretaries of the Air Force, Army and Navy and the Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at moldafskyd@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Diana Moldafsky

Acting Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

List of Congressional Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

This report (1) examines the extent to which the Department of Defense (DOD) selection of programs for the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) provides visibility into resourcing for the joint force in the Pacific, and (2) describes how DOD’s implementation and direction for PDI compares to the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI).

For our first objective, we reviewed documentation and conducted interviews to assess DOD’s process for selecting programs for PDI budget exhibits from fiscal year (FY) 2023 through FY 2025.[48] We also reviewed available guidance for the development of the PDI budget exhibit. Additionally, we examined documentation from the annual independent assessment developed by United States Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), compared its content to the annual PDI budget exhibits, and interviewed command officials. Finally, we assessed all information collected against DOD criteria on budget development and internal control principles as outlined in GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[49] Specifically, we determined the information and communication component and underlying principles on quality information and internal communication were relevant to our review.

For our second objective, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials to compare PDI and EDI, including how the initiatives were implemented and directed. We also examined DOD policies that establish criteria for PDI and EDI to determine how DOD applies these criteria to report budgetary information for each initiative to Congress. Additionally, we interviewed financial management and budget officials from the military services and combatant commands, INDOPACOM, and U.S. European Command (EUCOM), to understand roles and responsibilities for developing the budget reports for each initiative.

For both objectives, we conducted in-person site visits to INDOPACOM headquarters, as well as the headquarters for U.S. Army Pacific, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Pacific, U.S. Pacific Air Forces, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and certain program offices collocated with these commands. We interviewed financial management and budget officials with these organizations about their perspectives on PDI, including the selection of PDI programs and their input into the selection process.

We also conducted in-person or virtual interviews with the following headquarters level offices:

· Offices of the Under Secretaries of Defense

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Policy

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Acquisition and Sustainment

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Research and Engineering

· Joint Staff

· Strategic Resource Management Office

· Joint Training and Exercise Program

· Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation

· Air Force

· A3T

· Financial Management- Budget Programs

· Army

· Army Financial Management and Budget

· Congressional Affairs

· G8

· Marine Corps

· Programs & Resources

· Navy

· Financial Management and Budget

· N8, Integration of Capabilities & Resources

To determine whether there were any inconsistencies in the programs DOD components selected for the PDI budget exhibit, we conducted quantitative analysis of over 500 line items from the PDI budget exhibits on the types of programs and funding included therein. The PDI budget exhibits are part of DOD’s budget materials in support of the President’s budget request to Congress and undergo review by the Office of Management and Budget, according to officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Comptroller. To further ensure the reliability of the data in the PDI budget exhibits, we conducted data testing to identify missing or anomalous line items and funding estimates. We also interviewed agency officials about the processes they use to create the data, which, as noted above, resulted in some inconsistencies in the programs selected for PDI. We determined that data from the PDI budget exhibits were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of evaluating whether the data itself provided adequate visibility into resourcing of the joint force in the Pacific.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to November 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Diana Moldafsky, moldafskyd@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff members made key contributions to this report: Marcus Oliver (Assistant Director), Usman Ahmad (Analyst-in-Charge), Jesse Andrews, David Ballard, Michelle Fejfar, Ali Hansen, Richard Skinner, Theologos Voudouris, and Emily Wilson.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]The William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 1251 (2021), as amended. Although initially authorized in FY 2021, the PDI statute has been annually reauthorized and extended and remains in effect as of FY 2025.

[2]INDOPACOM is a geographic combatant command and has responsibility for planning and executing all military operations and activities in the Indo-Pacific region. To perform its variety of missions around the world, DOD operates six geographic combatant commands, which manage all military operations in their respective areas of responsibility.

[3]See Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the NDAA for FY 2022, 167 Cong. Rec. H7327-28 (daily ed. Dec. 7, 2021).

[4]EDI began as the European Reassurance Initiative in June 2014. DOD began referring to the program as EDI in 2018.

[5]H.R. Rep. No. 118-301, at 1248-49 (2023) (Conf. Rep.).

[6]We generally excluded the first PDI budget exhibit (FY 2022) from our analysis because it had different categories than subsequent budget exhibits and also included some major programs that were excluded from subsequent budget exhibits. Nevertheless, we included the first PDI budget exhibit in summary analysis of total budget estimates to provide context on the history of the PDI budget exhibits.

[7]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[8]For the purpose of this review, DOD components include, but are not limited to, the military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps); combatant commands, which are responsible for certain geographic or functional areas (e.g., U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM); U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and Cyber Command); and other organizations such as the Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Space Force is not included in the PDI budget exhibits and has been excluded from our review.

[9]The annual PDI budget exhibit includes programs from across DOD components. Individual components do not have separate PDI budget exhibits.

[10]Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Pacific Deterrence Initiative Criteria for Fiscal Year 2023 and Beyond (Mar. 25, 2022).

[11]Specifically, the statute states that PDI is to carry out certain “prioritized activities to improve the design and posture of the joint force in the Indo-Pacific region, primarily west of the International Date Line.” Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 1251 (2021), as amended.

[12]Facilities Sustainment, Restoration, Modernization programs are intended to keep DOD’s facilities in good working order (e.g., day-to-day maintenance requirements). They also provide resources to restore facilities due to age or accident-related wear and tear, as well as alterations and updates to implement new or higher standards and requirements.

[13]Components only select from those programs that have been validated for funding through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process, according to OUSD Comptroller officials.

[14]From FY 2022 through FY 2025, Congress enacted appropriations that resulted $29.5 billion of funding for programs that were selected for PDI.

[15]The military services operate component commands around the world that support DOD’s geographic combatant commands. The Indo-Pacific component commands are U.S. Army Pacific, U.S. Pacific Fleet, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Pacific, and U.S. Pacific Air Forces, and U.S. Space Forces, Indo-Pacific. They provide administrative support to their respective forces that are assigned to INDOPACOM.

[16]National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-81, § 1242 (2021), as amended.

[17]EDI was announced by the executive branch in 2014 and was authorized in the NDAA for FY 2015. Carl Levin and Howard P. ‘Buck’ McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2015, Pub. L. No. 113-291, § 1535 (2014).

[18]From FY 2010 through FY 2021, Overseas Contingency Operations amounts were appropriated into and executed out of the military services’ existing appropriations accounts, such as Operation and Maintenance; Procurement; and RDT&E. DOD defines “contingency operations” as small, medium, or large-scale campaign-level military operations related to DOD, including, but not limited to, support for peacekeeping operations, foreign disaster relief efforts, and noncombatant evacuation operations.

[19]GAO, European Deterrence Initiative: DOD Should Establish Performance Goals and Measures to Improve Oversight, GAO‑23‑105619 (Washington, D.C.: July 10, 2023).

[21]Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Pacific Deterrence Initiative Criteria for FY 2023 and Beyond (Mar. 25, 2022).

[22]DOD’s PDI guidance suggests that aircraft modernization is an example of a program that should not be included in the PDI budget exhibit.

[23]INDOPACOM generally has a limited role in the PDI budget exhibit, but it does select some of its own programs for the PDI budget exhibit. Administratively, INDOPACOM programs are funded through the Navy and, as such, they are shown as Navy funding in the PDI budget exhibit. In contrast, INDOPACOM includes programs from across DOD for its annual independent assessment.

[24]Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 1251(b).

[25]According to Army officials, they only selected budget estimates for the amounts required for the deployments west of the International Date Line.

[26]The officials further noted that these costs are funded in the Marine Corps overall budget, just not selected for the PDI budget exhibit.

[27]Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 1251 (2021), as amended. H. R. Rep. No. 116-617, at 1790 (2020) (Conf. Rep).

[28]See Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2022, 167 Cong. Rec. H7327-28 (daily ed. Dec. 7, 2021).

[29]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Sept. 10, 2014).

[30]S. Rep. No. 119-39, at 220-21 (2025).

[31]DOD officials acknowledged that completed programs often require ongoing sustainment funding which would continue to be included in PDI in future years. However, they noted that annual sustainment costs are typically lower than initial military construction or procurement costs themselves.

[32]Specifically, the Indo-Pacific Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024 included $542.4 million for transfer to Operation and Maintenance, Procurement, and RDT&E accounts only for unfunded priorities of INDOPACOM for FY 2024. Pub. L. No. 118-50, div. C, tit. I, § 101 (2024).

[33]The FY 2025 Independent Assessment contained $11.0 billion of unfunded requirements, while the remaining $15.4 billion consisted of programs and budget estimates from across DOD that were approved for funding. Conversely, the PDI budget exhibit contained $9.9 billion worth of programs.

[34]Special access programs are a system of enhanced security measures for sensitive capabilities or information that imposes safeguarding and access requirements exceeding those normally required for information at the same level. See DOD Directive 5205.07, Special Access Program Policy (Sept. 12, 2024).

[35]DOD Directive 7045.14, The Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) Process (Jan. 25, 2013)(incorporating change 1, Aug. 29, 2017).

[36]Commission on PPBE Reform, Defense Resourcing for the Future Final Report, (March 2024). The Commission’s 2024 report, which was a comprehensive review with dozens of recommendations, cited PDI as a best practice in one area, but also noted limitations such as PDI’s reliance on extensive manual effort and subjective assessments of how to categorize resources.

[37]DOD, Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Reform Implementation Plan (Jan. 16, 2025).

[39]In FY 2022, DOD shifted amounts for EDI into the base budget request because overseas contingency operation requests were discontinued as a separate funding category.

[41]For example, see GAO, Marine Corps Asia Pacific Realignment: DOD Should Resolve Capability Deficiencies and Infrastructure Risks and Revise Cost Estimates, GAO‑17‑415 (Washington, D.C.: April 5, 2017).

[42]Unlike PDI, EUCOM did not submit a separate report similar to INDOPACOM’s independent assessment for EDI, according to EUCOM officials.

[43]Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, European Deterrence Initiative Criteria for FY 2024 and Future Budget Cycles, (Feb. 21, 2023). According to officials the guidance was issued in consultation with EUCOM.

[44]Specifically, the PDI guidance states that components should not include certain types of investments or activities and lists munitions and military and civilian personnel costs as examples.

[45]According to EUCOM officials, DOD began developing budget requests for EDI in FY 2015.

[46]In the EDI budget exhibit, DOD organized activities into five lines of effort: (1) Increased Presence, (2) Exercises and Training, (3) Enhanced Prepositioning, (4) Improved Infrastructure, and (5) Building Partnership Capacity.

[47]EUCOM officials said that when EDI received overseas contingency operations appropriations from FY 2015–2021, the EUCOM Commander had more input into the specific activities that would be included in EDI and receive funding. EUCOM would develop issue papers outlining these projects and propose them to OUSD Comptroller, who would make the final decision on what programs would receive appropriated funding. EUCOM would monitor the progress of these projects as they were implemented by DOD components.

[48]We generally excluded the first PDI budget exhibit (FY 2022) from our analysis because it had different categories than subsequent budget exhibits. In addition, the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2022 expressed the view that the first budget exhibit was improperly focused on platforms, including the DDG–51, T–AO fleet oiler, and F–35, as opposed to improving the joint posture and enabling capabilities necessary to enhance deterrence in the Indo-Pacific region. 167 Cong. Rec. H7327-28 (daily ed. Dec. 7, 2021). Nevertheless, we included the first PDI budget exhibit in summary analysis of total budget estimates, as such analysis is unaffected by individual program selection and categorization.

[49]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).