WEST BANK AND GAZA

State’s Reporting on UN Efforts to Address Problematic Textbook Content Had Gaps Before Funding Ended

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-26-107708

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: LoveGrayerL@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Between 2018 and 2024, the U.S. Department of State (State) provided an estimated $375 million to support the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East’s (UNRWA) educational activities in the West Bank and Gaza. These funds supported UNRWA’s education system, including teacher salaries, facilities, and maintenance. Because the Palestinian Authority provides textbooks to UNRWA free of charge, no U.S. funds went toward the purchase of textbooks. Until July 2025, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) also supported education-related projects in the West Bank and Gaza, such as providing vocational training handbooks.

UNRWA and State took steps to identify and address problematic content in educational materials used in UNRWA schools. UNRWA reviewed textbooks and provided guidance to teachers on addressing identified content that did not align with UN values. However, UNRWA has faced some challenges in implementing its approach to address problematic content, such as teacher and community resistance. In addition, audits have found weaknesses in UNRWA’s educational activities and use of Palestinian textbooks, while also noting its commitment to principles such as neutrality. UNRWA has taken certain steps to address the issues raised in these audits. In the years that State provided funding to UNRWA, it monitored UNRWA’s actions to identify and address problematic content such as reviewing UNRWA reports and conducting field visits to schools.

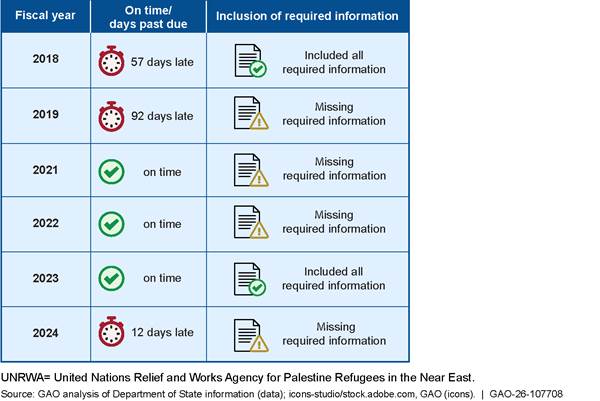

Since 2018, annual appropriations acts required State to report on certain UNRWA issues, including steps UNRWA took to ensure its educational materials are consistent with the values of human rights, dignity, and tolerance, and do not induce violence. State submitted six reports since 2018, three of which were submitted after the statutory deadline. This includes the 2019 report, which was submitted 92 days late. State also did not always address all the reporting requirements that Congress established. For example, in its 2022 report, State did not report on steps that UNRWA took to ensure that its educational materials did not induce incitement. Finally, although State developed standard operating procedures for ensuring report accuracy in response to a 2019 GAO recommendation, it did not always follow these procedures. Given the U.S. no longer funds UNRWA and State is no longer required to report to Congress on UNRWA, GAO is not making recommendations for improving State’s reporting.

Why GAO Did This Study

In the West Bank and Gaza, UNRWA schools use textbooks developed by the Palestinian Authority to educate students and prepare them for post-secondary education. However, UNRWA has identified problematic content in these textbooks, such as material that is counter to UN values of neutrality, nonviolence and nondiscrimination. The October 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel heightened concerns about UNRWA, including Israeli allegations that the textbooks radicalized youth and that UNRWA employees had connections to Hamas and other terrorist organizations. The U.S. is historically the largest source of funds to UNRWA, but additional funding was paused in January 2024 and subsequently all funding ended.

In June 2019, GAO reported that State had taken actions to address potentially problematic content in UNRWA educational materials but that its reporting to Congress omitted required information and contained inaccurate information. GAO was asked to update these findings. This report addresses (1) U.S. funding for educational assistance in the West Bank and Gaza for calendar years 2018 through 2024, (2) the extent to which UNRWA and State identified and addressed potentially problematic educational materials, and (3) the extent to which State submitted required related reports, and how it developed the reports and ensured their accuracy.

To address these objectives, GAO analyzed State and UNRWA financial data, reviewed relevant documents, analyzed State’s annual reports to Congress, and interviewed U.S. government officials. GAO also conducted fieldwork in Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan to visit an UNRWA school and interview Israeli, Palestinian Authority, and UNRWA officials, among others.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

Curriculum Framework |

Framework for the Analysis and Quality Implementation of the Curriculum |

|

DIOS |

Department of Internal Oversight Services |

|

IMPACT-se |

Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education |

|

PRM |

Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration |

|

State |

Department of State |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

|

UNRWA |

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East |

|

USAID |

United States Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 8, 2026

The Honorable Brian Mast

Chairman

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chris Smith

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bradley Scott Schneider

House of Representatives

Concerns of whether textbooks in United Nations (UN) schools contributed to antisemitism and incited violence in the West Bank and Gaza have persisted since we last reported on this issue in 2019, and have increased since the Hamas-led attack on Israel on October 7, 2023.[1] The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) provides humanitarian assistance to Palestinian refugees, including its education program that provides services for over 540,000 children in approximately 700 schools in its five fields of operation: Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the West Bank.[2] Prior to the conflict between Israel and Hamas, this included 96 schools with over 45,000 students in the West Bank and 288 schools with over 298,000 students in Gaza.

Citing it as an educational best practice for refugee communities, UNRWA uses the curricula developed by the host governments everywhere it operates. According to UNRWA, this ensures accreditation with host government ministries of education, which allows students to transition to higher forms of education, pass national exams, and qualify for entry to local and regional colleges and universities.[3] In keeping with this practice, UNRWA schools in the West Bank and Gaza use the Palestinian Authority curriculum and textbooks.[4]

The government of Israel, international donors, and others have expressed concerns about UNRWA’s use of host country curricula and textbooks, including that they may contribute to the promotion of antisemitism and incitement of violence. The October 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack on Israel heightened these concerns. The government of Israel also alleged that hundreds of UNRWA employees—including educators—had connections with Hamas or other terror networks and that the education program had led to radicalization in Gaza.

According to UNRWA, in the conflict following the October 7, 2023, attack, all its schools in Gaza have either been destroyed or turned into shelters, with all formal education at its schools having stopped. The United States has historically been the largest contributor to UNRWA, but because of ongoing concerns, additional funding was paused in January 2024 and subsequently all funding ended. According to UNRWA officials, a loss of contributions from the United States and the reduction of contributions from other donor countries may put its education program at risk.

In June 2019, we reported that UNRWA and the Department of State (State) had taken actions to address potentially problematic content in UNRWA schools in the West Bank and Gaza—content that promotes intolerance toward groups of people or incites violence—but that State’s reporting to Congress omitted required information and contained inaccurate information.[5] You asked us to update the findings of that report and review issues related to how UNRWA and State identify and address problematic textbook content. This report addresses (1) U.S. funding for educational assistance in the West Bank and Gaza for calendar years 2018 through 2024, (2) the extent to which UNRWA and State identified and addressed content that they identified as potentially problematic in educational materials for Palestinian refugees in the West Bank and Gaza, and (3) the extent to which State submitted required reports on UNRWA educational materials to Congress, and how it developed and ensured the accuracy of these reports.

To estimate the amount of U.S. funding for educational assistance in the West Bank and Gaza from calendar years 2018 through 2024, we analyzed State’s funding disbursements and UNRWA’s programming budgets to estimate annual U.S. funding to UNRWA’s educational programs in the West Bank and Gaza.[6] Because most U.S. contributions go to UNRWA’s general program budget, which is not earmarked, we prorated these contributions to the percentage of the general program budget that went to educational activities in the West Bank and Gaza. We assumed that State’s share of funding for educational activities out of total funding to UNRWA is the same as the share spent on educational activities by UNRWA from its total funding regardless of source. We also included U.S. contributions toward education-related special projects and emergency appeals as reported by State. To assess the reliability of the data, we conducted interviews with State and UNRWA officials and reviewed relevant documentation such as UNRWA’s program budgets and State’s disbursement data. We determined the data were reliable for the purposes of our review. We also analyzed program and funding information from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to identify any programming that included educational materials, such as technical training manuals.

We conducted fieldwork in Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan to determine how UNRWA identifies and addresses potentially problematic content and how State conducts oversight of these activities. We also conducted fieldwork to determine how State collects, analyzes, and verifies the information it includes in its required reports to Congress. Our fieldwork included a site visit to an UNRWA school in the West Bank to observe classrooms; review materials; and interview school administrators, teachers, and students. We also met with officials from the U.S. embassies in Israel and Jordan, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Palestinian Authority Ministry of Education, an Israeli think tank, and UNRWA leadership and field staff.

To examine the extent to which UNRWA and State have developed and implemented mechanisms to identify and address potentially problematic content in educational materials for Palestinian refugees since the beginning of fiscal year 2018, we reviewed relevant policies and procedures that both entities established and implemented. We reviewed the U.S.-UNRWA Frameworks for Cooperation—documents that outline shared goals and priorities and reflect policy commitments made by both parties—that were in effect during the timeframe of our review. We reviewed the commitments specified in these documents to guide our information requests and assessments of the actions UNRWA and State took to identify and address problematic content. We also reviewed documents that UNRWA provided, outlining its procedures for reviewing educational materials and addressing issues identified. We also reviewed documentation from State, including cables, to understand the mechanisms it uses to monitor UNRWA’s efforts to identify and address problematic content. In addition, we conducted interviews and obtained written responses from State and UNRWA officials to gather further information on these mechanisms.

To examine the extent to which State submitted required reports on UNRWA’s educational materials to Congress since the beginning of fiscal year 2018, and how it developed and ensured the accuracy of these reports, we reviewed relevant laws and reporting requirements, as well as State’s standard operating procedures for developing reports to Congress on UNRWA. Specifically, we examined the legal provisions that require State to report on the steps UNRWA is taking to ensure that the content of its educational materials aligns with the values of human rights, dignity, and tolerance, and does not induce incitement. We also reviewed other legal requirements related to UNRWA’s efforts to ensure staff adhere to principles such as neutrality. In addition, we identified and reviewed all the relevant reports that State submitted to Congress in fiscal years 2018 through 2024. We assessed whether State submitted the reports on time and if the reports complied with the applicable legal requirements. We also compared information in State’s reports to steps outlined in its standard operating procedures intended to ensure reporting accuracy. Additionally, we conducted interviews and obtained written responses from State officials to gather further information on how the reports were developed and how State ensured their accuracy. For more details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

History of UNRWA

The UN General Assembly established UNRWA in 1949 with a temporary mandate to provide humanitarian assistance and protection to registered Palestinian refugees.[7] UNRWA provides food and other essential supplies, health care, education, and other assistance directly to its beneficiaries living in Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the West Bank. With no political resolution on the Palestinian refugees’ status, the General Assembly has regularly extended UNRWA’s mandate, with the current mandate expiring on June 30, 2026. At the beginning of its operations, it was responding to the needs of about 860,000 Palestinian refugees. As of 2023, the number of Palestinian refugees numbered around 5.9 million. According to UNRWA, it provides services to approximately 2.5 million of these refugees—with the numbers shifting somewhat depending on the circumstances on the ground at any given point of time—across its five fields of operation.

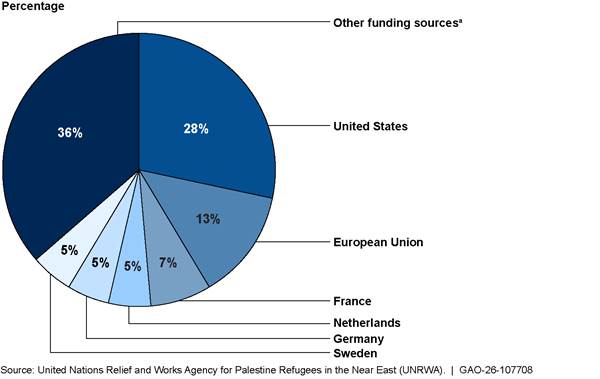

UNRWA is funded primarily through voluntary contributions from governments and also through the UN regular budget. In 2024, UNRWA received $1.4 billion in contributions, over 80 percent of which came from governments of UN member states and the European Union. UNRWA provides its services directly to its beneficiaries, making it one of the largest UN agencies with over 30,000 employees in 2023. The majority of UNRWA’s over 30,000 employees are Palestinian refugees with only about one percent of its employees being international staff. UNRWA is distinct from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, with each operating under separate organizational mandates and operational approaches.

UNRWA’s Educational Program and the Textbooks It Uses

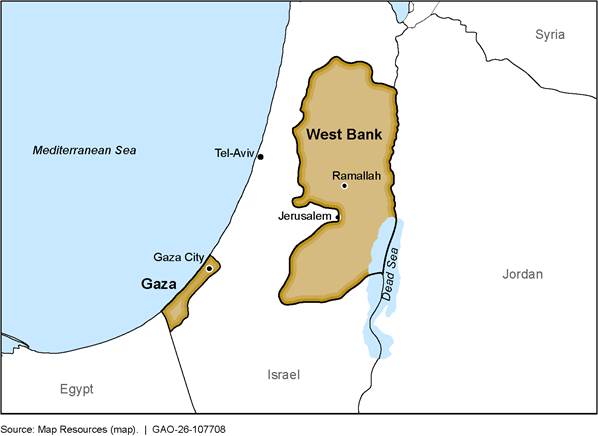

UNRWA’s schools educate over 540,000 students in approximately 700 schools in its five fields of operation. Prior to the October 7, 2023, attack on Israel, it operated 96 schools with over 45,000 students in the West Bank and 288 schools with over 298,000 students in Gaza, according to UNRWA. See figure 1. UNRWA uses textbooks provided by the Palestinian Authority in its schools in the West Bank and did the same in its schools in Gaza until formal schooling halted on October 7, 2023. UNRWA does this in keeping with the UN-recognized practice of using the curricula and textbooks of host governments. UNRWA says this helps ensure that UNRWA students can continue their education at government secondary schools and universities and can take national exams. According to UNRWA, Palestinian law requires UNRWA to use Palestinian Authority textbooks to maintain its accreditation. Also, developing a new curriculum for students in the West Bank and Gaza would be cost prohibitive by requiring ongoing funds for development, printing, and delivery of textbooks.

Figure 1: United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) School in the West Bank

The Palestinian Authority has provided its textbooks to UNRWA free of charge. The Palestinian Authority first developed its own textbooks in 2000, and it developed the current versions of its textbooks in 2016.[8] According to UNRWA, the Palestinian Authority has not issued entirely new textbooks since 2016 and the most significant revisions took place in the 2020–2021 edition of the textbooks. UNRWA shared these revisions with its donors, including the United States. In 2022, the Palestinian Authority paused textbook changes and stated that it planned to establish an independent Center for Curriculum Development to take over responsibility for textbooks and curriculum, according to UNRWA.

State and USAID Involvement in Education in the West Bank and Gaza

The United States has historically been the largest contributor to UNRWA, providing over $7 billion since it began operations in 1950. This funding came primarily from State, through its Migration and Refugee Assistance account, which is managed by State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM). PRM had a role in funding and overseeing education assistance provided by UNRWA in the West Bank and Gaza. State’s relationship with UNRWA was guided by the U.S.-UNRWA Framework for Cooperation, biennially negotiated between PRM and UNRWA. The frameworks included UNRWA’s commitment to not support terrorism—a condition tied to providing this assistance.

USAID did not fund UNRWA but has funded bilateral assistance programs in the West Bank and Gaza that include educational components, including some programs that provide training handbooks and other educational materials. USAID terminated most of its projects, including all its education-related projects, in the West Bank and Gaza in 2025 and transferred the remaining contracts and grants to State on July 1, 2025, according to USAID officials.

The Gaza Conflict

On October 7, 2023, after decades of tension and cycles of violence over Gaza, Hamas and other militant groups launched an attack on Israel from Gaza that killed roughly 1,200 people and took 251 people hostage. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has reported that over 60,000 people in Gaza were killed as a result of the Israeli military response, as of September 2025. These casualties included Hamas militants and civilians. Also, many homes as well as much of the infrastructure in the area were damaged. According to the United Nations Satellite Center, 83 percent of all structures in Gaza City were damaged. The UN estimates that over 684,000 people were displaced as of September 2025.

Israel has alleged that over one thousand UNRWA employees—including educators—had connections with Hamas or other terror networks, and that the education program had led to radicalization in Gaza.[9] Because of these allegations, the government of Israel passed legislation that, according to its sponsors (1) prohibited contact between UNRWA and the government of Israel, and (2) prohibited UNRWA from operating in what Israeli leaders consider to be Israeli territory, including East Jerusalem. According to the Congressional Research Service, these laws came into effect in January 2025.

UNRWA disputes these allegations, noting four independent investigations that have all concluded that UNRWA is a neutral and impartial organization. In addition, UNRWA states that the government of Israel has never provided it with evidence related to these allegations, despite its repeated requests that Israel do so.

According to UNRWA, the conflict and the Israeli legislation negatively affected much of its educational program throughout the West Bank and Gaza. As previously mentioned, prior to the October 7, 2023, attack on Israel, UNRWA operated 96 schools with over 45,000 students in the West Bank and 288 schools with over 298,000 students in Gaza. Since the attack:

· Gaza: UNRWA paused all formal education in Gaza. UNRWA reports that all its schools have either been destroyed or are now used as shelters and it instead uses an emergency program of self-learning materials. At times, UNRWA has also implemented some informal psychosocial support for students, according to UNRWA headquarters officials. UNRWA has also implemented some remote learning through smartphone apps such as WhatsApp that link small groups of students with a teacher for a few hours a day.

· The West Bank: UNRWA’s educational program continues to operate in the West Bank using the Palestinian Authority textbooks, but UNRWA reports that some of its schools in the northern areas have been closed due to Israeli military activity that has displaced an estimated 40,000 people. In these areas, UNRWA uses some of the same self-learning materials as in Gaza and is also trying to use remote learning through smartphone apps such as Microsoft Teams.

· East Jerusalem: Because of the legislation banning UNRWA activities in Israeli territory, the Israeli government ordered UNRWA’s six schools in East Jerusalem to close, according to UNRWA reports. Following Israeli enforcement actions, UNRWA reports that they closed the schools in May 2025.[10]

On October 13, 2025, the governments of the United States, Egypt, Qatar, and Türkiye announced a comprehensive peace plan to end the Gaza conflict. The 20-point plan included a hostage release, resumption of aid, economic development plan, international stabilization force, and provisions for temporary governance in Gaza, among other things. On November 17, 2025, the UN Security Council endorsed the plan and called on all UN member states to work toward comprehensive and enduring peace in the region.

State Funded UNRWA Education in the West Bank and Gaza, and USAID Directly Supported Education in this Region

State Provided an Estimated $375 Million to Support UNRWA’s Educational Activities in 2018 through 2024

Of the $1.1 billion that State disbursed to UNRWA from 2018 through 2024, we estimate that $375 million was used for UNRWA’s education-related activities in the West Bank and Gaza.[11] The $375 million that we estimate the U.S. provided for UNRWA’s education-related activities in the West Bank and Gaza fell into three budget categories:

· Program budget ($354 million, 94 percent): UNRWA’s program budget pays for its education program and includes teacher salaries, facilities, and maintenance. Because the Palestinian Authority provides textbooks to UNRWA free of charge, no U.S. funds went toward the purchase of Palestinian Authority textbooks. These funds did, however, support reviews of the textbooks to identify any problematic content.

· Emergency appeals ($18.5 million, five percent): Education-related emergency appeals from UNRWA included activities such as in-person or remote training for teachers in times of conflict, providing psychosocial support to children, and reducing barriers to access to education by using technology and remote learning.

· Special projects ($2.3 million, less than one percent): The U.S. provided funds for special projects related to education including Human Rights, Conflict Resolution, and Tolerance curriculums and UNRWA’s Digital Learning Platform.

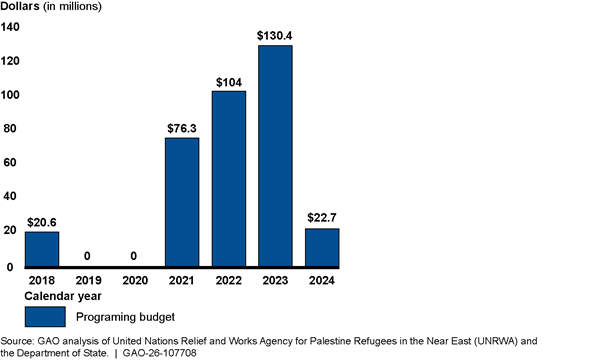

Total U.S. contributions to UNRWA varied greatly over time and were subject to pauses and prohibitions, including contributions to UNRWA’s educational activities. See figure 3. In August 2018, State ended all funding to UNRWA due to concerns raised about UNRWA’s operations. This pause lasted through fiscal years 2019 and 2020 and was lifted in April 2021.

Then, on January 26, 2024, the U.S. once again paused funding to UNRWA based on allegations that several UNRWA employees had participated in the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel. Fifteen other UNRWA donors also suspended their contributions, but later restarted them, according to the Congressional Research Service. Subsequently, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, prohibited any U.S. funds going to UNRWA through March 25, 2025. On February 4, 2025, the President signed Executive Order 14199—this prohibited U.S. executive branch agencies from providing funds to UNRWA and other selected UN agencies. The Executive Order also required the Secretary of State to conduct a review of all international intergovernmental organizations of which the U.S. is a member and provides any type of funding or other support, to determine which organizations are contrary to U.S. interests and whether such organizations can be reformed.[12]

Figure 3: Estimated U.S. Contributions to UNRWA’s Program Budget Used for Education Activities in the West Bank and Gaza (Calendar Years 2018–2024)

The United States has historically been the largest contributor to UNRWA.[13] In 2023, U.S. contributions to UNRWA accounted for 28 percent of UNRWA’s total donor contributions. See figure 4. The United States was also the largest contributor in 2021 and 2022, when contributions were not subject to a pause or prohibition.

aNote: Other funding sources include other

donor countries and organizations, and funding from the United Nations regular

budget.

As of March 2025, just 21 percent of UNRWA’s total program budget for calendar year 2025 had been funded due to the lack of a U.S. contribution and other donor countries reducing their normal contributions, according to UNRWA. According to UNRWA headquarters officials, UNRWA faces an acute budget shortfall, and it may have difficulty managing its cashflow on a month-to-month basis. UNRWA officials noted that this is putting its programs, including educating students, at risk.

On June 20, 2025, the UN issued a strategic assessment of UNRWA that sought to inform (1) deliberations on how best to safeguard UNRWA’s mandate under current conditions, and (2) the UN’s decision regarding UNRWA’s future role, structure, and sustainability. Regarding UNRWA’s education program, the assessment noted that UNRWA students consistently outperform their peers in host country schools and that, due in significant part to UNRWA, literacy in the West Bank and Gaza is at 98.2 percent, which it said is vital for development and sustainable peace.

The assessment also noted, however, that UNRWA’s financial model is not sustainable, and years of austerity have taken an increasing toll on services, including overcrowded classrooms and multi-shift schools. The assessment concluded that the current funding crisis is of a radically different magnitude, following the suspension or reduction of funding by several key donors. It identified four possible scenarios for the future of UNRWA: (1) inaction and the potential collapse of UNRWA, (2) reduction of services to align with a more predictable level of funding, (3) institutionalizing collective responsibility by securing multi-year funding, aligning UNRWA’s funding and services, and increasing accountability, and (4) maintaining UNRWA’s core while gradually transferring service delivery to host governments and the Palestinian Authority.

Some USAID Programs Included Educational Components, but USAID Did Not Provide Funding to UNRWA

USAID did not fund UNRWA but did provide funding for bilateral assistance programs in the West Bank and Gaza through nongovernmental organizations that included educational components, such as providing training handbooks and other educational materials.[14] According to USAID officials, USAID terminated most of its projects, including all of its education-related projects, in 2025 and transferred the remaining contracts and grants to State on July 1, 2025. Prior to these terminations, USAID had managed 24 projects in the West Bank and Gaza since 2018 that included technical training handbooks or other types of educational materials.

USAID disbursed these funds to various implementing partners, mostly U.S.-based nongovernmental organizations, to conduct these programs. These programs included a seven‐year program designed to provide safe spaces and support for 80,000 vulnerable and marginalized youth and young adults aged 10 through 29. These programs also included a cluster of vocational training programs on topics such as hybrid and electric vehicle maintenance and repair, maintaining and operating industrial machines, culinary art and food and beverage service, and low voltage electrical wiring.

To address concerns raised in our June 2019 report and by members of Congress, USAID educational programming included a content review, according to USAID officials.[15] For any program that included educational materials produced by an implementing partner, USAID officials said they reviewed the materials to ensure that they aligned with United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) standards.[16] For example, in January 2024, USAID officials reviewed children’s stories related to a youth program and prohibited the use of any of the program’s content until the implementing partner excluded two of the stories that included content that USAID officials deemed inappropriate. According to USAID officials, these technical training manuals and other materials usually did not mention anything related to politics, religion, geography, or history.

The USAID OIG has issued alerts to its implementing partners that no USAID funds should go toward UNRWA because of the current funding prohibition. For example, the OIG issued an alert to all of USAID’s acquisition and assistance partners on May 30, 2024, that said that the restriction applied to all contracts, assistance awards, and other transactions. According to USAID OIG officials, they have not received any credible reports of instances when USAID funds had gone to UNRWA.

In our 2019 report, we noted that USAID had several ongoing projects in the West Bank and Gaza related to education, including two programs directly with the Palestinian Authority. In 2018, the United States passed the Taylor Force Act, which generally prohibits U.S. funding going to the Palestinian Authority unless the Secretary of State certifies to congressional committees that the Palestinian Authority has taken certain steps related to ending violence against Israeli and U.S. citizens and payments to terrorists, among other things.[17] According to USAID officials, USAID has not provided any funding or engaged in any projects with the Palestinian Authority since the passage of the Taylor Force Act except when specifically permitted under the law.[18]

UNRWA Took Steps to Identify and Address Problematic Content, and State Monitored These Efforts

To identify and address problematic content, UNRWA took steps to review its educational materials, trained teachers, and provided supplementary teaching documents to teach around or ban certain problematic content, while State monitored and supported UNRWA’s efforts. UNRWA’s approach to address problematic content and deliver education has faced challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict in Gaza, operational constraints including limited funding, and internal factors related to teacher union strikes, according to UNRWA officials, teachers, and students. UNRWA’s educational activities and the Palestinian Authority textbooks, including some used in UNRWA schools, were evaluated by UNRWA’s internal audit office and external reviews, such as one funded by the European Union. UNRWA has taken steps to address the limitations identified. In addition to these oversight efforts, in the fiscal years that State provided funding to UNRWA, it monitored UNRWA’s actions to identify and address problematic content by reviewing UNRWA reports and conducting field visits, for example.

UNRWA Has Taken Steps to Identify and Address Problematic Content

UNRWA Reviewed Palestinian Authority Textbooks and Self- Learning Materials

To identify problematic content, UNRWA has taken steps to review the curriculum and content of the Palestinian Authority textbooks as well as its self-learning materials. Self-learning materials include worksheets, videos, and games, that are eligible for use by UNRWA teachers in classrooms and by students at home for core subjects across all grades in UNRWA’s five fields of operation. UNRWA seeks to identify problematic content through curriculum framework reviews, rapid reviews, and self-learning material reviews.

Curriculum framework review. UNRWA’s Framework for the Analysis and Quality Implementation of the Curriculum (Curriculum Framework) includes tools to evaluate classroom materials and teaching practices to ensure its schools meet educational needs while acknowledging the heritage and culture of Palestinian refugees.[19] Developed in 2013, the Curriculum Framework highlights the importance of reflecting UN values such as human rights and non-discrimination regarding race and sex throughout teaching and learning in UNRWA schools. UNRWA conducts the Curriculum Framework review at the field level in each of its fields of operation when new textbooks are released. The Curriculum Framework review is a more comprehensive, academic review compared to the rapid review process.

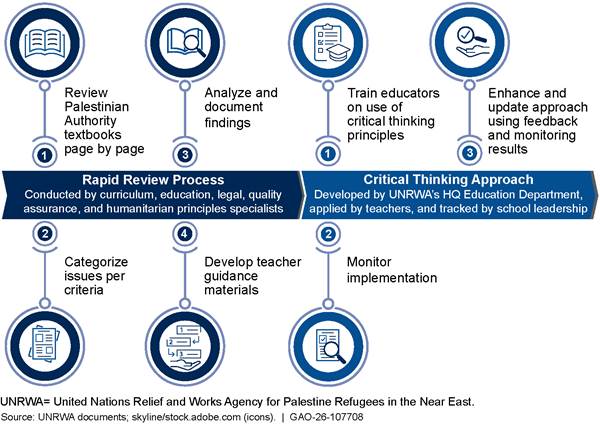

Rapid review process. In addition to the Curriculum Framework review, UNRWA reported that it conducts reviews of new textbooks in its five fields of operations as needed, which it calls the “rapid review” process, to identify content that may not align with UN values and UNESCO standards. The Palestinian Authority published new textbooks in 2016. Since then, UNRWA has conducted rapid reviews of the textbooks because of the urgent need to review them as soon as they were available, according to UNRWA. Although the Palestinian Authority has not published any new textbooks since 2016, it has revised existing textbooks. Therefore, UNRWA reviewed them each semester for updates. UNRWA’s Executive Office, curriculum and education specialists, quality assurance committee, humanitarian principles team, and Department of Legal Affairs collaborate to conduct these rapid reviews each semester.

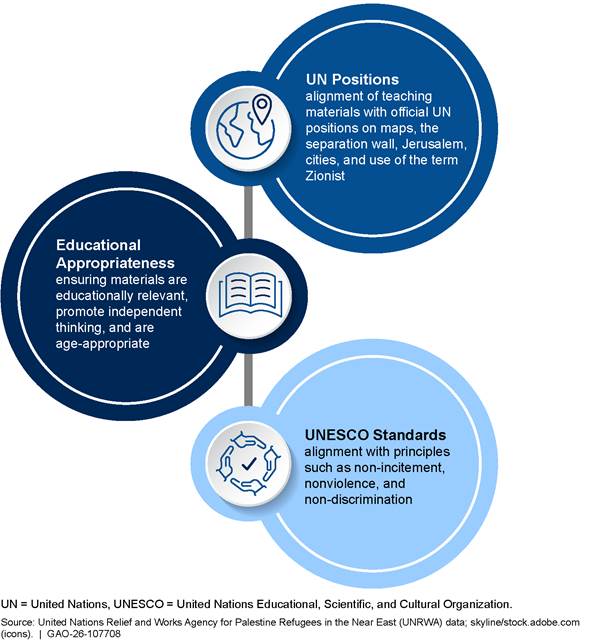

UNRWA initially reviewed the Palestinian Authority textbooks using criteria related to neutrality/bias, gender, and age appropriateness. However, in 2022, UNRWA updated its rapid review criteria to focus on UN positions, educational appropriateness, and UNESCO standards, as shown in figure 5 below. Each criterion includes subdomains. For example, the UN positions criterion includes a subdomain related to not using the term Zionist to describe occupiers or an occupation, which UNRWA considers neither neutral nor consistent with UN terminology.

Figure 5: UNRWA’s Criteria for Identifying Problematic Material in Palestinian Authority Textbooks Used in UNRWA Schools

As part of its 2024–2025 academic year rapid review, UNRWA reviewed 13,149 textbook pages and reported that it found issues on 507 of them, representing 3.85 percent of the total pages reviewed. In total, UNRWA reported that it identified 435 issues across the 507 pages, 349 of which (roughly 80 percent) involved material that did not align with UN positions, as shown in table 1 below.[20] Beyond its 2024–2025 review, UNRWA identified the following issues, among others, in the text:

· reference to Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine;

· a description of a boy who was shot and had a broken leg while participating in a demonstration in support of a prisoners’ strike in Zionist prisons;

· mathematics problems that compare the number of prisoners across two years and use the number of martyrs to teach a mathematical concept; and

· illustrations that fail to acknowledge women’s contributions to the Palestinian economy.

UNRWA identified most issues in Social Studies and Arabic textbooks, although issues sometimes appeared in other subjects such as Science and Mathematics.[21] Of the 349 identified issues that related to the UN positions criterion, 138 involved the use of the word Zionist and 95 involved maps.

A substantial number of the issues that UNRWA identified in its rapid review were included in 10th grade textbooks. According to UNRWA officials, when UNRWA stopped teaching 10th grade in East Jerusalem in June 2024, it resulted in about a 40 percent decrease in previously identified issues. A 2023 UNRWA report noted that in the West Bank, 91 students were enrolled in the 10th grade, out of a total of 336,354 students across the West Bank and Gaza.

Table 1: Number of Issues Identified by UNRWA in Its 2024–2025 Rapid Review of Palestinian Authority Textbooks Used in Its Schools

|

Criteria |

Total number of issues identified |

Number of pages with identified issues |

|

United Nations positions |

349 |

397 |

|

Educational appropriateness |

74 |

76 |

|

UNESCO standards |

12 |

34 |

|

Total |

435 |

507 |

Legend: UNESCO = United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

Source: United Nations Relief and Works Agency for

Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) | GAO‑26‑107708

Self-learning materials reviews. In addition to reviewing Palestinian Authority textbooks through the curriculum framework review and the rapid review process, UNRWA established a review process for its self-learning materials. UNRWA developed this review process as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and in support of continued learning during school closures. The curriculum team at UNRWA’s headquarters and a humanitarian principles team reviews the self-learning materials for content that does not align with UN principles and values. In cases of doubt or difference in opinion, a committee comprised of members from UNRWA’s legal department, protection and humanitarian principles team, education department, and executive office review the materials to reach a conclusion, according to UNRWA documentation and officials.

In 2024, UNRWA redesigned and updated its self-learning materials for the West Bank and Gaza and continues to use these materials in its classrooms and for emergencies, such as the conflict in Gaza, according to UNRWA officials. UNRWA uploaded its self-learning materials to its digital learning platform, which serves as the repository of UNRWA’s approved self-learning materials for use in its classrooms. The digital learning platform, launched in 2021, includes self-learning materials for all grade levels in core school subjects in each of UNRWA’s five fields of operation. In addition to its use of the digital learning platform, UNRWA officials told us that they established digital learning centers in 73 of its schools in the West Bank for grades 6–9 in September 2024. The digital learning centers support UNRWA’s strategy on information and communication technologies for education.[22] During our site visit to an UNRWA School in the West Bank, we observed a teacher and students at one of these centers as shown in figure 6 below.

Legend: UNRWA = United Nations Relief and Works Agency for

Palestine Refugees in the Near East

UNRWA experienced challenges in the rollout of its self-learning materials during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, in a 2021 press release, UNRWA explained that in the rush to maintain uninterrupted education, a small amount of host-country-provided material, which was previously flagged as inconsistent with UN values, was mistakenly distributed.[23]

UNRWA stated that upon identifying the issue, it conducted a thorough review of its self-learning materials and took steps to ensure only approved content was used going forward. According to UNRWA officials, another contributing factor was that some actors were independently creating materials and falsely branding them with UNRWA’s logo. To address this, UNRWA reported that it now embeds QR codes into its self-learning materials for identification and verification to help prevent UNRWA from being misrepresented or held accountable for materials it did not produce.[24]

UNRWA Provided Its Teachers with Supplementary Teaching Materials to Address Identified Problematic Content

In 2022, UNRWA started using the Critical Thinking Approach to address problematic content identified in Palestinian Authority textbooks, replacing its Teacher Centered Approach.[25] The Critical Thinking Approach aims to highlight UN values and encourages students to engage in discussions to explore a variety of perspectives related to issues identified in the textbooks. UNRWA also created the Critical Thinking Handbook in 2021 to provide teachers with techniques, concepts, and activities to support classroom discussions. As a part of the Critical Thinking Approach, UNRWA provided its teachers with supplementary teaching materials that included strategies to address issues identified during the rapid review process, as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Overview of UNRWA’s Rapid Review Process and Critical Thinking Approach in the West Bank and Gaza

The supplementary teaching materials include teacher reference grids and guidance for educators, provided by UNRWA’s HQ Education Department, as tools to use when addressing issues identified in the classroom. The teacher reference grids include information that outlines the grade, subject, textbook, and the relevant criteria and page number where issues were identified during the rapid review process. Further, the guidance for educators provides options for teachers to address the issues identified in the classroom while maintaining focus on the learning objective.

For example, UNRWA has identified issues related to educational appropriateness and relevance in a third-grade mathematics textbook where one of the possible answers referenced the number of Palestinian martyrs during a 2014 Gaza conflict. To address this issue in the classroom, UNRWA provided its teachers with options that included prioritizing the main objective of the lesson, which was to develop proficiency in adding numbers within millions. In addition, if a social studies textbook includes an issue related to a map of historical Palestine being used in a non-historical context, the teacher may note that the map is a part of historical Palestine, display a current UN map of the region, or describe the development of the map of Palestine over the last 100 years.

Although UNRWA provides its teachers with supplementary teaching materials to address identified problematic content, some external stakeholders have raised questions about UNRWA’s continued use of textbooks that contain problematic content, particularly given that UNRWA does not edit the textbooks that it receives from the Palestinian Authority. Nongovernmental organizations s stated that even if teachers provide additional context or do not discuss certain problematic portions of the materials, the students are still exposed to the problematic content. Views on the impact of this challenge vary. For example, in 2021, the Georg Eckert Institute reported, in a study funded by the European Union, that establishing a link between textbook content and students’ worldviews is difficult.[26]

According to its report on Palestinian textbooks, the Institute noted that several factors contribute to the challenge establishing such a link, including that students may have difficulty understanding textbooks, teachers may supplement or omit content, and students may critically reflect on or challenge the views presented in school textbooks. UNRWA officials told us that they recognize they are giving teachers a difficult task by asking them to implement the Critical Thinking Approach along with managing academic demands. However, they believe they have limited options.

UNRWA provided training to its teachers and monitored the use of the Critical Thinking Approach but faced financial and logistical challenges in doing so. For example, UNRWA reported that it trained 424 Gaza Field Office staff on its digital learning platform and assessed learning materials for compliance with the Critical Thinking Approach, humanitarian principles, and gender equity in 2020 and 2021. UNRWA also reported that the West Bank Field Office began training education specialists, school principals, and deputies in 2018, later extending training to teachers with follow-up activities and refresher sessions. In 2021 and 2022, UNRWA continued the training through follow-up activities using updated textbooks. UNRWA also provided training to 477 Gaza Field School Principals on school management, and monitoring of the Critical Thinking Approach late in 2022. However, additional training was postponed in the West Bank and Gaza due to the impact of the conflict.

In addition, UNRWA reported that it monitors the Critical Thinking Approach through oversight by school principals, observation and support visits from education specialists and the curriculum team, and classroom observation studies. UNRWA conducts classroom observation studies every three years, where it monitors teaching and learning practices across UNRWA’s five fields of operation, according to UNRWA officials.[27] Yet, due to budget constraints, UNRWA has not conducted a classroom observation study since 2021, according to UNRWA officials. UNRWA told us that it postponed its classroom observation study originally planned for 2024 and rescheduled its implementation for 2026.

UNRWA also has a human rights, conflict resolution, and tolerance education program designed to create an environment where human rights are practiced and experienced daily within UNRWA schools. Since piloting the program in 1999, UNRWA has continued to evolve it across its schools, according to UNRWA officials. For example, in 2013, UNRWA developed a Human Rights, Conflict Resolution and Tolerance Teacher Toolkit supported by U.S. funding. Over the years, the program has continued to focus on activities to highlight the importance of human rights education in its schools such as launching school parliaments and hosting a human rights enhancement and enrichment workshop in Amman. According to UNRWA officials, UNRWA faces challenges implementing the program at full capacity because the U.S. is no longer providing funding.

UNRWA Faced Challenges Delivering Education

UNRWA encountered a range of challenges that impacted its ability to provide consistent education. These challenges have included the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict in Gaza, limited funding and staffing, travel restrictions, teacher and community resistance, and teacher neutrality.

COVID-19 pandemic. UNRWA reported that the COVID-19 pandemic forced schools to close and disrupted the education of Palestine Refugees from 2020–2022. To ensure uninterrupted access to education and support during emergencies, UNRWA introduced remote learning using self-learning materials developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. UNRWA also operated schools on Saturdays when necessary. UNRWA reported that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, learning outcomes did not meet targets due to learning loss caused by the disrupted learning in two academic years and insufficient academic and technical support during periods of remote learning, for example. UNRWA fully resumed in person learning for its students in 2022.

Conflict in Gaza. Conflict in Gaza has disrupted education by affecting teachers and students, destroying schools or turning them into shelters, and contributing to severe humanitarian impacts, including the loss of life, widespread displacement, and food insecurity. UNRWA reported that these conditions have both academic and psychosocial effects that negatively impacted learning outcomes. UNRWA teachers and officials told us that the distractions caused by past and possible danger or suffering created difficult teaching environments, especially for sensitive or controversial topics.

During a visit to an UNRWA school in the West Bank, we observed a class where students said the sounds of drones, planes, and gunfire made it difficult to concentrate on their schoolwork. Also, as a part of our fieldwork in Amman and the West Bank, UNRWA officials, teachers, and students told us that students have become more likely to question the relevance of learning information related to human rights when they feel they personally do not experience those rights themselves. In addition, according to UNRWA officials, the conflict in Gaza has impacted students going to and from school. For example, UNRWA officials told us that following the October 7, 2023 attacks, the Israeli government introduced additional movement restrictions in the West Bank, which impacted UNRWA’s staff and students. Due to the escalation of violence since the October 7th attacks, UNRWA reported that it has prioritized providing mental health and psychosocial support for the students since 2023. UNRWA also reported that it has continued to rely on digital learning approaches to maintain access to education and improve learning outcomes. However, students told us that this also presents challenges, particularly in areas where reliable internet access is limited.

Funding, staffing, and travel limitations. Factors such as limited funding, staffing shortages, and travel restrictions impacted UNRWA’s ability to conduct educational activities. For example, limited funding impacted UNRWA’s ability to train its teachers on the use of the Curriculum Framework to review the Palestinian Authority textbooks and to address problematic content. When we reported on this issue in 2019, UNRWA similarly faced challenges training its teachers to address problematic content due to financial shortfalls and constraints.[28]

Teacher and community resistance. Teacher union strikes and community resistance have disrupted the implementation of the Critical Thinking Approach. According to UNRWA officials, this resistance began in 2017 when UNRWA removed and blacked out pages containing problematic content related to a controversial figure. Union members responded with strikes, and UNRWA lost its accreditation, according to UNRWA officials. Afterward, UNRWA resumed using the original pages while trying to apply the Critical Thinking Approach but reported strong resistance to this approach from local stakeholders.

The community and the Department of Refugee Affairs, for example, viewed the approach as an attempt to change the curriculum of the Palestinian Authority textbooks.[29] UNRWA also reported that its education staff, including the Chief of Education, received threats if they tried to move forward with implementing the Critical Thinking Approach. In January 2025, UNRWA stopped using a fifth grade Arabic textbook in which this figure appears and reported having banned the teaching related to the figure altogether, now relying on supplementary materials to teach the subject. UNRWA officials stated that there has been a more limited reaction within the Palestinian community to this decision than there was during UNRWA’s previous attempt to remove textbook material in 2017. UNRWA officials noted that this may be due to conflict in the West Bank and Gaza and because they had self-learning materials in place to teach the subject.

Teacher neutrality. Although UNRWA provides guidance and supplementary teaching materials to its teachers to support the implementation of the Critical Thinking Approach, the responsibility for implementing this approach in a neutral manner rests on its teachers. This expectation is shaped by UNRWA’s Neutrality Framework. The framework outlines standards for staff conduct, including the use of social media, and the importance of maintaining neutrality to preserve UNRWA’s reputation. During our site visit to an UNRWA school in the West Bank, UNRWA teachers and officials told us that maintaining neutrality in classroom settings can be challenging, particularly in conflict-affected environments.

The teachers themselves experience the emotional and physical effects of the conflict, which can further complicate their ability to support students and manage classroom dynamics, said UNRWA officials and teachers. For example, one teacher described difficulties teaching maps related to Jerusalem because people have different beliefs about who the city belongs to. She explained that students often share their own feelings about the conflict, which can lead to emotional discussions and make it harder to stay focused on the lesson. As a result, teachers often deviate from planned lessons to address problematic content, students’ emotional needs, and the tensions arising from the conflict, which reduces the time spent on delivering the curriculum, according to UNRWA officials.

Due to the difficulties teachers may face while implementing the Critical Thinking Approach, UNRWA officials told us that principals may reassign teachers who appear to be struggling to implement the approach as intended. Despite these concerns, students spoke positively about their teachers and experiences at UNRWA schools, frequently telling us how much they enjoyed learning and appreciated the support they received in the classroom.

UNRWA Has Taken Steps to Update Its Mechanisms to Identify and Address Problematic Content in Response to Criticism

UNRWA has taken steps to update its mechanisms to identify and address problematic content in Palestinian Authority textbooks in response to internal and external criticism. Internally, UNRWA’s Department of Internal Oversight Services (DIOS) conducted an audit on UNRWA’s rapid review process in 2022.[30] The audit concluded that UNRWA conducted extensive textbook reviews, developed teaching and training materials for classroom use, and remained agile during remote learning to mitigate risks of materials that did not align with UN values being uploaded to the digital learning platform. However, the DIOS also found that UNRWA’s rapid review process needed major improvement to provide reasonable assurance that its objectives are achieved.

The DIOS issued seven recommendations to effectively implement the rapid review process. The recommendations included establishing clear timelines and monitoring mechanisms to ensure the rapid review and related documents are completed and shared in a timely manner, developing a mechanism to monitor the implementation of its approach to address identified problematic content, and defining roles and responsibilities.

Externally, the 2024 Independent Review of Mechanisms and Procedures to Ensure Adherence by UNRWA to the Humanitarian Principle of Neutrality, commonly referred to as the Colonna report, assessed UNRWA’s efforts to ensure neutrality in education, among other things.[31] The report made a total of 50 recommendations, eight of which were related to education. The independent review group reported that UNRWA has a range of mechanisms and procedures in place to ensure alignment of educational materials with UN values and an emphasis on neutrality. The report also noted that UNRWA has been responsive to allegations of neutrality breaches and criticism of the textbooks. However, the report also recommended that UNRWA improve oversight of educational content, establish staff training on neutrality and human rights, expand digital learning, and develop stronger systems for accountability and inclusion.

In addition, the Georg Eckert Institute’s 2021 report on Palestinian textbooks reviewed a sample of the Palestinian Authority textbooks, including some textbooks for grades not taught at UNRWA schools.[32] It found that the textbooks adhere to UNESCO standards of non-incitement, nonviolence, and non-discrimination as well as reflect educational criteria common in international discourse. However, the report states that the textbooks also express a narrative of resistance within the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and demonstrate antagonism toward Israel.

Nongovernmental organizations such as the Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education (IMPACT-se), have also raised concerns about the content of the textbooks, as well as the transparency and effectiveness of UNRWA’s mechanisms to identify and address content that is not aligned with UN values. Specifically, in 2024, IMPACT-se reported that UNRWA has not publicly disclosed specific textbook pages it flagged within the Palestinian Authority curriculum, the criteria used in its reviews, or how it applies the Curriculum Framework. This makes it difficult to verify whether UNRWA is actively mitigating content that may incite antisemitic hate or violence, according to IMPACT-se.[33]

In response, UNRWA has taken steps to improve its educational activities by implementing some recommendations from both internal and external reviews. For example, to address a recommendation made in the Colonna report, UNRWA reported that it established a digital system to manage its learning materials and uses artificial intelligence to support faster, more consistent reviews and to streamline collection, analysis, and reporting. However, officials noted that progress has been challenged by limited funding. UNRWA reported that four out of the eight education-related recommendations from the Colonna report have been implemented while the implementation of the other four is planned to be completed by December 2026. UNRWA also established a structured process for its rapid review framework, with defined timelines and clearly assigned roles and responsibilities to address a recommendation made by DIOS.

Although UNRWA has accepted recommendations from both internal and external reviews and used them to update its processes, UNRWA officials told us that they believe certain organizations try to discredit its work. They stated that the organizations sometimes present examples of problematic content that, in their view, is taken out of context or cites material that is no longer in use. Likewise, the Georg Eckert Institute reported that some studies related to the content in the Palestinian Authority textbooks include findings that are generalized and exaggerated.

State Supported and Monitored UNRWA’s Mechanisms to Identify and Address Problematic Content

Prior to the end of U.S. funding to UNRWA, State used the U.S. and UNRWA Frameworks for Cooperation from 2018–2024, which set expectations for both the U.S. and UNRWA, to guide its oversight efforts related to UNRWA’s educational activities.[34] In particular, from 2018–2024, the U.S. and UNRWA Frameworks for Cooperation included shared goals and priorities, continued U.S support to UNRWA, monitoring and reporting actions, and communication and partnership arrangements. For example, the 2023–2024 framework included a priority focused on improving UNRWA’s capacity to review textbooks and educational materials to identify and address content inconsistent with UN principles.

State supported and monitored UNRWA’s efforts to identify and address problematic content through various activities. For example, State participated in UNRWA’s Advisory Commission, which met twice a year, to discuss issues affecting UNRWA and aimed to provide advice and support to UNRWA’s Commissioner General. State officials also engaged in ongoing conversations with UNRWA officials about its educational activities. In addition, State reviewed reports that it required UNRWA to submit twice a year. The reports described UNRWA’s activities to ensure neutrality so that the U.S. could assess whether UNRWA was meeting U.S. funding conditions. These reports also included updates on UNRWA’s educational activities.

State also conducted field visits and provided funding support. Specifically, PRM’s Refugee Coordinators conducted quarterly field visits to UNRWA schools to monitor and review the implementation of UNRWA’s educational activities, according to State officials. In August 2023, State also facilitated training for UNRWA teachers to address problematic content using the Critical Thinking Approach. As described earlier, State stopped providing funding to UNRWA in January 2024 and ended its monitoring of UNRWA’s educational activities.

Since 2018, State’s Required Reporting on UNRWA Activities Met Some, but Not All, Requirements

We found that State did not consistently submit reports to Congress by the statutory deadline, include all required information, or follow its procedures for accuracy. Because the United States has ended its assistance to UNRWA, State is also no longer required to provide any reporting on UNRWA to Congress and we are therefore not making recommendations for State to improve its congressional reporting.

State Submitted Reports to Congress, But Half Were Late and Most Omitted Required Information

From 2018–2024, State submitted six reports on UNRWA’s activities to Congress as required by annual appropriations acts. State’s reports to Congress typically included information on UNRWA’s financial status, facilities, and educational activities, among other things. For example, the reports discuss UNRWA’s efforts to ensure the neutrality of its staff, its use of Palestinian Authority textbooks, its human rights education program, its rapid review process, and its efforts to train its teachers to address problematic content. To develop these reports, State relied on information from a variety of sources, including UNRWA’s reports, briefings from UNRWA officials, input from PRM Refugee Coordinators in Jerusalem, engagements with other major donors, and information from nongovernmental organizations, according to State officials.[35]

State was typically required to report on UNRWA under two separate provisions, though it often addressed both provisions in a single report. These provisions were section 7048(d)(5) and section 7019(e) of the annual appropriations acts:[36]

· Section 7048(d)(5) required State to report on steps taken by UNRWA to ensure that its educational materials were consistent with the values of human rights, dignity and tolerance, and did not induce incitement.

· Section 7019(e) generally required State to report on information related to UNRWA’s actions to ensure its educational materials were consistent with the value of dignity for all persons; and did not induce or encourage incitement, violence, or prejudice; and that staff were following principles such as neutrality, among other things.

These provisions also established differing deadlines between 2018 and 2024 by which State was required to report. For example, in 2018, State was required to submit the Section 7048(d) report before funds were obligated for UNRWA and within 45 days of the enactment of the Consolidated Appropriations Act. Similarly, in 2022, State was required to submit the Section 7048(d) report before funds were obligated, but in this instance, State had to submit the Section 7019(e) report within 90 days of the enactment of the Consolidated Appropriations Act.

Of the six reports we reviewed on UNRWA’s activities since 2018, one report—the 2023 report—was submitted on time and also included all required information. State did not submit a report in 2020 because it did not provide funding to UNRWA that year. State submitted half of the reports late and most (four out of six) were missing required information, as shown in figure 8. Specifically:

· State’s 2018 report included all required information, but it was submitted after its statutory deadline.

· State’s 2019 report was submitted after its statutory deadline and omitted required information on UNRWA’s commitment and capacity to ensure that its materials are not utilized for political purposes or terrorist activities. State officials also told us that they do not have insight into the reason for these delays and omissions due to staff turnover.

· Although State submitted its 2021 report on time, it omitted the required breakdown of student enrollment data by age and did not describe steps taken by UNRWA to ensure its educational materials are consistent with the value of dignity and do not induce incitement to violence.

· State’s 2022 report to Congress was submitted on time, but it did not describe UNRWA’s actions to ensure its educational content did not induce incitement. State officials told us that they had no current staff from 2022 that could comment on this omission.

· State submitted its 2024 report after the statutory deadline and omitted required information on UNRWA’s procedures to substitute problematic material with curricula that emphasizes the importance of human rights, tolerance, and nondiscrimination. The report also omitted required information on the steps taken by UNRWA to respond to claims that are determined not to be credible. State officials told us that the 2024 report was delayed because of its efforts to fact check and clear the report internally to ensure accuracy in its submission.

Figure 8: GAO’s Analysis of the Department of State’s Compliance with Congressional Reporting Requirements on UNRWA’s Educational Activities, Fiscal Years 2018–2024

Note: State did not submit a report in 2020 because it did not provide funding to UNRWA that year and thus was not required to submit a report.

State Did Not Consistently Follow Procedures for Ensuring Accurate Reports on UNRWA Activities

We found that State did not consistently follow its procedures for sourcing information to ensure report accuracy. State developed standard operating procedures for preparing its reports to Congress on UNRWA in response to our prior recommendations. In 2019, we reported that State did not include some key information in its reports to Congress on UNRWA and at least one report contained inaccurate information.[37] We recommended that State take steps to ensure accuracy in its reports. As a result, State addressed the recommendation by developing standard operating procedures that included 16 steps related to:

· monitoring bill language;

· confirming deadlines;

· compiling and sourcing information by organization and source document;

· using the most current information as of the legislation date; and

· coordinating between State’s bureaus and offices.

However, State’s reports did not always cite education-related information by organization, document, and date.[38] In some cases, State cited the organization without a date, relied on oral discussions without identifying a corroborating document, or did not cite education-related information at all. State officials told us they could not comment on the sourcing practices used in some of the reports due to staff turnover. In addition, State officials told us that, prior to its change in engagement with UNRWA, PRM’s Refugee Coordinators and Monitoring and Evaluation team members scrutinized official documents and efforts regarding UNRWA with great diligence and attention to detail.

In March 2025, State severed all financial ties with UNRWA, which it formalized in a letter to UNRWA’s Commissioner General. [39] In June 2025, State also ceased its participation in UNRWA bodies, including the Advisory Commission and its Sub-Committee. Therefore, we are not making any recommendations for State to improve its congressional reporting.

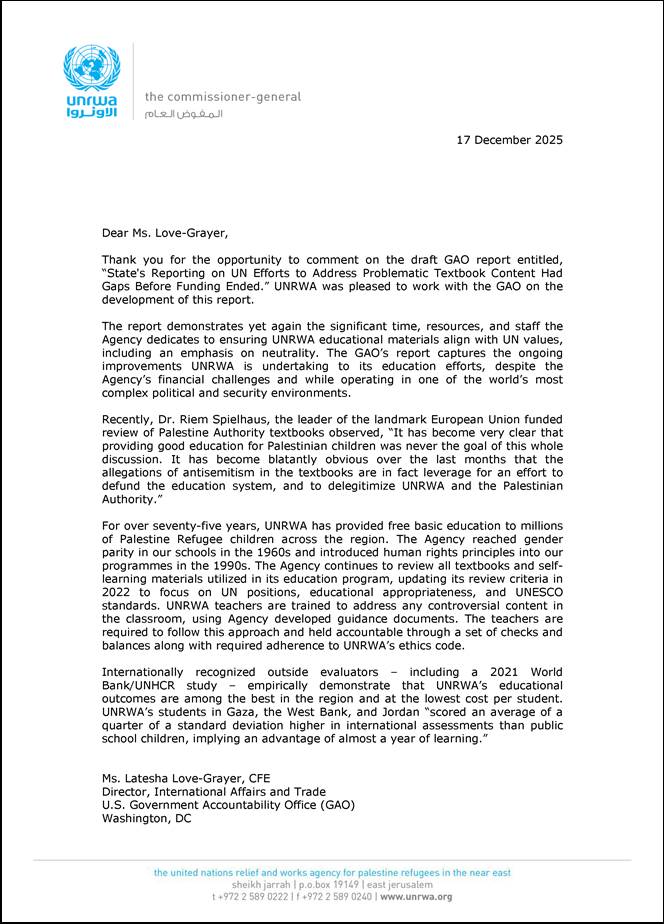

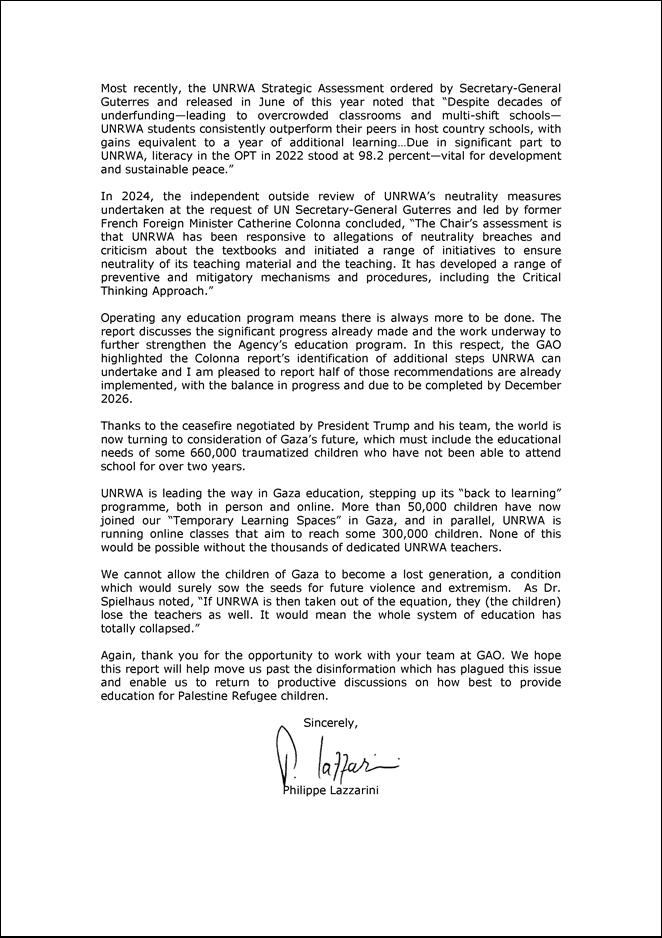

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to State, USAID, and UNRWA for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, UNRWA emphasized the importance of its mission to educate Palestinian children and noted steps it has taken to seek to ensure neutrality in its schools. State and UNRWA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of State, the Administrator of USAID, the Commissioner General of UNRWA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at LoveGrayerL@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Latesha Love-Grayer

Director, International Affairs and Trade

This report addresses (1) U.S. funding for educational assistance in the West Bank and Gaza for calendar years 2018 through 2024, (2) the extent to which the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and the Department of State (State) developed and implemented mechanisms to identify and address content that they identified as potentially problematic in educational materials for Palestinian refugees in the West Bank and Gaza, and (3) the extent to which State has submitted required reports on UNRWA educational materials to Congress, and how it has developed and ensured the accuracy of these reports.

To estimate the amount of U.S. funding for educational assistance in the West Bank and Gaza from 2018 through 2024, we analyzed State’s funding disbursements and funding of UNRWA’s programming budgets to estimate annual U.S. funding to UNRWA’s educational programs in the West Bank and Gaza. Because most U.S. contributions go to UNRWA’s program budget, which is not earmarked, we prorated these contributions to the percentage of the program budget that went to educational activities in the West Bank and Gaza. State provided us with actual disbursements from its Migration and Refugee Assistance account. We used the dates of these disbursements to convert the information they provided from fiscal year to calendar year to align with UNRWA’s program budget.

We assumed that State’s share of funding for educational activities out of total funding to UNRWA is the same as the share spent on educational activities by UNRWA from its total funding, regardless of source. For example, in 2023, the U.S. contributed 29.94 percent of UNRWA’s program budget ($230.7 million out of program budget of $770.6 million). That year, UNRWA spent $435.5 million on educational activities in the West Bank and Gaza. Therefore, we estimate that the U.S. contributed $130.4 million to UNRWA’s educational assistance to the West Bank and Gaza (29.94 percent of $435.5 million). We repeated this for all years from 2018 through 2024. We also included specific, non-estimated disbursements to emergency appeals and special projects that UNRWA considered education-related. This methodology is consistent with GAO’s prior reporting on this topic.

We conducted interviews with State and UNRWA officials and reviewed relevant documentation such as UNRWA’s program budgets and State’s disbursement data to determine that data were reliable for the purposes of our review. We also analyzed program and funding information from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to identify any programming during the same time period that included educational materials, such as technical training manuals.

We conducted fieldwork in Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan to determine how UNRWA identifies and addresses potentially problematic content and how State conducts oversight of these activities. We also conducted fieldwork to determine how State collects, analyzes, and verifies the information it includes in its required reports to Congress. Our fieldwork included a site visit to an UNRWA school in the West Bank to observe classrooms; review materials; and interview school administrators, teachers, and students. We also met with officials from the U.S. embassies in Israel and Jordan, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Palestinian Authority Ministry of Education, an Israeli think tank, and UNRWA leadership and field staff.

To examine the extent to which UNRWA and State identified and addressed potentially problematic content in educational materials for Palestinian refugees since the beginning of fiscal year 2018, we reviewed relevant policies and procedures that both entities established and implemented. We reviewed the U.S.-UNRWA framework agreements during the timeframe of our review to guide our information requests and assessments of the actions UNRWA and State took to identify and address problematic content. We assessed how UNRWA identifies and addresses problematic content within Palestinian Authority textbooks and its self-learning materials. We reviewed documentation from State, including cables and policy guidance, to understand the mechanisms it uses to monitor UNRWA’s efforts to identify and address problematic content.

To assess how UNRWA identifies and addresses problematic content within its educational materials, we reviewed documentation from UNRWA that included information on its textbook review process, as well as guidance provided to its teachers, semiannual reports provided to State, and donor briefing notes. We interviewed State officials in Washington, D.C., and overseas to further assess how they oversaw and monitored UNRWA’s processes, as well as UNRWA officials to understand the mechanisms they used to conduct rapid reviews of textbook content and address issues identified. In addition, we interviewed an official from the Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education (IMPACT-se), a non-governmental organization that we selected because it actively conducts research on educational materials used by UNRWA, to understand their perspectives on UNRWA’s educational activities.

We also reviewed studies conducted by IMPACT-se, UN Watch, an independent review group, and the Georg Eckert Institute to collect diverse perspectives on this topic. As part of our work, we also observed two UNRWA classes. During these observations, we saw how UNRWA incorporated technology into their lessons and how students expressed their feelings related to their lives and education. We conducted multiple follow-up discussions with relevant officials from State and UNRWA to understand actions taken related to UNRWA’s educational activities. It was not within the scope of our review to independently review the underlying documents, textbooks, or self-learning materials to fully assess the reliability of the results from UNRWA’s rapid review process.

To examine the extent to which State submitted required reports on UNRWA’s educational materials to Congress since the beginning of fiscal year 2018, and how it developed and ensured the accuracy of these reports, we reviewed relevant laws and reporting requirements. Specifically, we examined the legal provisions that require State to report on the steps UNRWA is taking to ensure that the content of its educational materials aligns with the values of human rights, dignity, and tolerance, and does not promote incitement. We also reviewed other legal requirements related to UNRWA’s efforts to ensure its facilities and staff adhere to principles such as neutrality. We compared State’s reports to Congress submitted in 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 to the legal requirements. We assessed whether State submitted the reports on time and if the reports complied with the applicable legal requirements.

To assess how State developed the reports and ensured their accuracy, we reviewed State’s standard operating procedures for preparing reports to Congress on UNRWA. We examined how State sourced and cited information, as outlined in those procedures. In addition, we interviewed and obtained written responses from State officials in Washington, D.C. and overseas to understand the processes they used to draft the reports, including how they gathered information, coordinated internally, and verified accuracy. We also interviewed UNRWA officials to understand how they coordinated with State during the report development process. In addition, we reviewed documents that UNRWA provided to State to inform the reporting.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Comments from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

GAO Contact

Latesha Love-Grayer, LoveGrayerL@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, Ryan Vaughan (Assistant Director), Kirstin Crook, Gergana Danailova, Bahar Etemadian, Brian Hackney, and Donna Morgan made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone