NAVY SHIP MAINTENANCE

Fire Prevention Improvements Hinge on Stronger Contractor Oversight

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Shelby S. Oakley at oakleys@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Navy has suffered significant losses from 13 fires on ships undergoing maintenance since 2008. The Navy investigated these fires, including one on board the USS Bonhomme Richard in 2020. Based on actions taken since that fire, the Navy has improved fire safety and culture in the Navy and among contractors—contributing to no major fires since 2020.

However, staffing shortages threaten progress and oversight. GAO found that key organizations responsible for fire safety oversight have personnel shortages. Such shortages limit the Navy’s oversight of fire safety standards and add a burden for sailors who are balancing other duties.

Further, the Navy did not fully assess challenges with contractor oversight. In reviewing the Navy’s key oversight tools, GAO found that these tools do not effectively address contractor compliance with fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods:

Corrective Action Requests. The Navy uses these requests to bring contractors into compliance with contract requirements. But this process does not incorporate monetary penalties to address persistent issues. As a result, the Navy issued many requests related to fire safety, including a severe warning prior to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire, but fire safety issues continued.

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans. These plans are a tool through which the Navy assesses monetary penalties. The Navy’s guidance and its quality assurance surveillance plans for the six ships GAO reviewed did not assess penalties for noncompliance with contractual safety standards.

Progress Payment Retention Rates. The Navy generally pays contractors as maintenance work is completed, retaining some payment until the work is done. The Navy’s continued use of a reduced retention rate implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic reduces the effectiveness of this tool.

Liability. The Navy has not adjusted its limitation on ship repair contractor liability for major losses since 2003. Inflation and the increased complexity and cost of ship maintenance mean that the limit is proportionally less than when established, placing increase financial risk on the government in the event of a loss, such as a major fire.

Why GAO Did This Study

Fire is a significant risk for Navy ships undergoing maintenance. A 2020 fire found to be caused by arson on board the USS Bonhomme Richard resulted in the ship’s decommissioning, decades earlier than planned.

This report assesses (1) the extent to which Navy actions taken following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire addressed contractor compliance with fire safety standards, and (2) the Navy’s use of various contracting tools for ensuring contractor accountability and compliance with fire safety standards.

GAO reviewed Navy actions based on lessons learned from the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. GAO also selected six nonnuclear surface ships undergoing major repair by four different contractors at four domestic maintenance centers, and analyzed Navy documentation of contractor compliance with fire safety standards. Additionally, GAO visited three regional maintenance centers and toured five ships.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to the Navy, including for the Navy to develop a mechanism to address resources across organizations responsible for fire safety oversight; review contractor compliance with fire safety standards when developing actions to address any future major fires during ship maintenance periods; assess how to improve the Corrective Action Request process; ensure Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans and guidance include safety standards; reassess the progress payment retention rate; and reassess the limitation of liability clause for ship repair contractors. The Navy concurred with all six recommendations.

Abbreviations

CAR Corrective Action Request

CNO Chief of Naval Operations

CNRMC Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center

CPARS Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System

DFARS Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement

DOD Department of Defense

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

NASSCO National Steel and Shipbuilding Company

NAVSEA Naval Sea Systems Command

QASP Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans

RMC regional maintenance center

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 17, 2025

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

Navy ships undergoing maintenance face a great risk of fire due to the nature of ship maintenance, including large amounts of welding and other “hot work.”[1] Fire incidents have endangered lives, caused significant physical and financial damage, and reduced the availability of ships for operations and training. In April 2023, we reported that there were 15 major fire incidents from May 2008 through July 2020 that resulted in billions of dollars in total damage, as calculated by the Navy.[2] Thirteen of these 15 incidents occurred on ships undergoing maintenance.

Completing ship maintenance safely and on schedule is critical if the Navy is to meet its ambitious goal of having 80 percent of its ships ready to surge on short notice by 2027. However, major fires can delay maintenance and have taken warships out of service. One of the most significant fire incidents in the Navy’s history occurred on July 12, 2020, when a major fire started in the lower vehicle storage compartment onboard the USS Bonhomme Richard, an amphibious assault ship.[3] The fire burned for several days, spread to 11 of 14 decks, and reached temperatures of more than 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit. When it caught fire, the ship was in the process of completing upgrades worth $250 million that would have allowed it to deploy with F-35B aircraft. The fire resulted in over $3 billion in damage, leading the Navy to decide that the ship was not salvageable. Subsequently, it was decommissioned 17 years sooner than planned. As a result, the Navy does not have the 10 large deck amphibious warfare ships required by statute.[4]

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the Navy determined that the cause of the fire was arson by a crewmember.[5] During the investigations, the Navy reported that repeated failures allowed for the accumulation of significant risk during the maintenance period. For example, the condition of the ship was significantly degraded due to offline heat detection capabilities and shipboard firefighting systems, clutter, and combustible materials accumulated on the ship. Further, numerous issues, including contractor oversight issues, contributed to the extent of the devastation caused by the fire and the complete loss of the ship. Figure 1 shows the fire aboard the USS Bonhomme Richard in July 2020.

According to two investigative reports, the lower vehicle stowage space of the USS Bonhomme Richard contained items belonging to the ship repair contractor, such as forklifts with fuel tanks, dozens of large cardboard containers filled with supplies, batteries, and other flammable materials that were improperly stowed in the space. The reports concluded that these items fed the fire. This is a fire safety risk often referred to by the Navy as “poor housekeeping.” Following the fire, the Navy conducted a July 2021 Major Fires Review that had a similar finding across the ship maintenance enterprise. Navy survey teams observed that some ships under repair had a reasonable level of contractor cleanliness, while others had trash, urine bottles, rags, gloves, and cigarette butts left onboard each day. Poor housekeeping, particularly in large open spaces, can enable fires to get out of control quickly rather than burn out due to lack of fuel.

During the course of our separate review assessing the Navy’s cruiser modernization efforts, we found the Navy had weakened its use of quality assurance tools—including for safety—during ship maintenance.[6] Given these findings, we performed this present work at the initiative of the Comptroller General. This report assesses (1) the extent to which Navy actions taken following the 2020 USS Bonhomme Richard fire addressed its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards, and (2) the Navy’s use of various contracting tools to ensure contractor accountability and compliance with fire safety standards.

To assess the extent to which the Navy’s actions sufficiently address its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards, we reviewed actions the Navy’s Learning to Action Board implemented based on actions taken following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. Specifically, we identified the status of these actions and how they addressed the Navy’s oversight of fire safety while ships are in a maintenance period. We specifically assessed the Navy’s oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards during nonnuclear surface ship maintenance work. Our review did not include oversight of new construction shipbuilding programs or private nuclear repair yards.

We also met with relevant officials within Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center (CNRMC) and visited regional maintenance centers (RMC) in Norfolk, Virginia; Mayport, Florida; and San Diego, California. We also interviewed officials from RMC Northwest at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Further, we collected information on staffing levels across the Navy’s primary offices responsible for enforcing fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods.

To identify the Navy’s tools for ensuring contractor accountability and compliance with fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods and to assess the effectiveness of these tools, we selected six nonnuclear surface ships undergoing major maintenance in fiscal years 2024 and 2025. The selected ships include amphibious assault ships, Arleigh Burke class destroyers, and a Ticonderoga class guided-missile cruiser. The selected ships were overseen by four RMCs in the U.S. with four different ship repair prime contractors. For each of these ships, we reviewed maintenance contracts to identify relevant contract terms and conditions, such as liability clauses, contract financing provisions, Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans (QASP), and Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) Standard Items (which outline fire safety requirements contractors are required to follow), among other documents.

Additionally, we collected and analyzed documents issued by the Navy to ship repair contractors as part of fire safety oversight, including fire safety inspection results, Corrective Action Requests, stop work orders, and other documents. We conducted site visits to three of the four RMCs we reviewed and toured five ships. We also interviewed contractor representatives and Navy officials from four RMCs, ship commanding officers and crews on each of the six selected ships, officials from NAVSEA offices, and other relevant officials.

Additional details about our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Navy Surface Ship Maintenance

Ship maintenance work increases the risk of fire, in part, because maintenance often involves spark-producing operations and welding—referred to as hot work—in confined and enclosed spaces in the presence of combustible materials. These variables complicate the Navy’s ability to prevent, detect, and respond to fires on ships. Figure 2 depicts welders cutting steel, an example of hot work.

The Navy undertakes a range of maintenance periods ranging from a few weeks to years depending on the extent and complexity of the work required. The most intensive maintenance and modernization periods are called Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) availabilities, which we will refer to as CNO maintenance periods. These periods can take years to complete. The Navy accomplishes major repair work during these periods. This level of work requires complex processes to complete restorative work, such as structural, mechanical, and electrical repairs. CNO maintenance also may include modernization work to upgrade a ship’s capabilities or extend the ship’s service life. During these periods, the ship’s fire safety posture changes. For example, the ship’s firefighting systems are taken offline at times and replaced by temporary systems, sailors move aboard or off the ship, and contractors complete hot work on the ship, among other things.

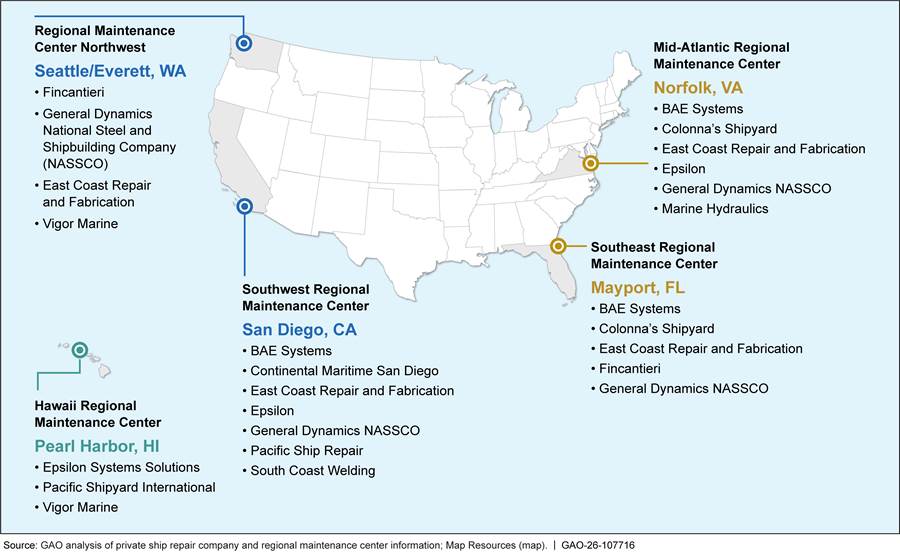

Navy Ship Repair Industrial Base

Private repair companies are a key part of the shipbuilding industrial base. Among other things, these companies conduct maintenance for the Navy’s nonnuclear surface fleet. This fleet generally includes destroyers, amphibious ships, and small surface combatants. As of May 2024, 12 companies—including some that operate in multiple locations—conducted CNO maintenance for the Navy’s amphibious and surface combatants. Each of these locations has a corresponding Navy oversight office, known as an RMC. Figure 3 shows the companies that conduct these maintenance periods and their locations, as well as the location of the Navy’s RMCs.

Figure 3: Map of Private Ship Repair Companies Conducting Navy Ship Maintenance Work and Regional Maintenance Centers as of May 2024

Note: The Navy uses a separate construct for ship maintenance for the Littoral Combat Ship. As a result, some companies that were excluded from this figure perform maintenance work for the Littoral Combat Ship.

In February 2025, we reported that private ship repair companies had not met the Navy’s shipbuilding and ship repair goals, in part due to infrastructure and workforce challenges.[7] For example, the private ship repair industrial base has not met the Navy’s schedule goals for completing maintenance periods, although there have been some recent improvements. According to the Navy’s maintenance plan, in fiscal year 2022, repair companies completed only 36 percent of non-nuclear powered surface ship maintenance periods on time.

Navy Fire Safety Policy and Standards

Major fire prevention requires that the Navy and its contractors effectively implement fire safety standards. The Navy has issued fire safety documents that include guidance on specific fire prevention and response procedures, firefighting training, and other processes. When followed, these standards can help prevent fires from starting and help ensure that personnel quickly extinguish fires that do start.

The two key policy documents are summarized below:

Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response. In February 2014, in response to a fire on a Los Angeles class attack submarine undergoing maintenance, the Navy released fire safety guidance, known as the “8010 Manual.” The Navy revised this guidance after the USS Bonhomme Richard fire in 2020.[8] The manual specifies the requirements that all Navy officials are to follow for the prevention of, detection of, and response to fires aboard Navy ships undergoing maintenance to ensure the safety of personnel and equipment. For example, it specifies what should be included in a fire safety plan, establishes training and qualification requirements for RMC fire safety officers and Navy fire safety watches, and provides information on fire protection systems, such as water supply systems. A fire safety watch is the person responsible for monitoring day-to-day fire safety conditions and initiating response actions in the event of a fire. The 8010 Manual applies to all ship maintenance and construction activities at public and private repair shipyards (via the associated NAVSEA Standard Items) and RMCs. It also governs industrial work (including maintenance, repair, modernization, and construction of ships) on Navy vessels.

NAVSEA Standard Items. The Navy applies standards and requirements—including those outlined in the 8010 Manual—to its ship repair contractors through NAVSEA Standard Items, which are clauses to be included in ship maintenance contracts. When included in contracts, the contractor must meet these standards when conducting maintenance and modernization work. If the contract and the 8010 Manual deviate from each other, a contractor is required to implement only those NAVSEA Standard Items incorporated in the maintenance contract. The Navy updates NAVSEA Standards Items at least annually through a process that seeks feedback from various Navy and private ship repair industry officials.

The 8010 Manual and NAVSEA Standard Items generally reflect fire safety elements outlined in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration Standard Number 1915, Occupational Safety and Health Standards for Shipyard Employment. These elements include housekeeping, hot work, and fire protection requirements, among other things.

Tools for Oversight of Contractors

The Navy uses several processes and tools to ensure contractor compliance with the requirements reflected in ship maintenance contracts.

The key processes and tools identified by the Navy are summarized below:

Corrective Action Request (CAR). CARs are the method by which the Navy requests the contractor to correct specific non-conformities with contractual requirements and to initiate preventive action to eliminate the cause of non-conformities. There are four levels, categorized as A through D—and referred to as “methods.” Method A CARs are the least severe and are issued for minor non-conformities, such as those that can be corrected within 3 days of discovery. Examples include administrative discrepancies in submittals of work specifications, as well as potential safety issues like incomplete forms that certify a space is approved for hot work posted at the work site, as required. Method D CARs are the most severe and are reserved for systemic or critical failures, either when a Method C has not yielded satisfactory results or when the severity of the violation justifies immediate escalation. For example, the Navy has issued Method D CARs for multiple repetitive safety and hot-work-related violations.

Letter of concern. Repeated instances of CARs may lead to the Navy issuing a letter of concern to the contractor. This is a formal written notification expressing serious concern about a contractor’s performance or compliance. A letter of concern typically describes the specific issues that occurred and requires the contractor to provide a plan for corrective action.

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan (QASP). According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), a QASP should be prepared along with the contract’s statement of work and should specify all work requiring surveillance and the method of surveillance.[9] A QASP is a contract administration tool that provides a contract’s performance criteria, standards, and procedures for government surveillance and oversight, including monetary penalties the Navy can assess if the contractor’s performance fails to meet the established standards. A QASP used to administer a ship maintenance contract typically outlines monetary deductions if specific deliverables, performance standards, or quality requirements are not met, per the terms of the contract.

Progress payments and retention rates. Progress payments are a type of contract financing that allows the contractor to receive payment before government acceptance of supplies or services.[10] Contract financing helps contractors manage expenses during performance by providing cash flow. Retentions are amounts withheld from a contractor’s progress payment per the terms of the contract. The retention above the specified progress payment percentage is paid upon submission of proper invoices for accepted products or services. By statute, the progress payment rate on a Navy contract for ship repair, maintenance, or overhaul of a naval vessel must not be less than 90 percent, or 95 percent for small businesses. Therefore, the Navy may withhold up to 10 or 5 percent of the progress payment from the contractor until contract completion. This amount may be adjusted as the contract approaches completion.[11]

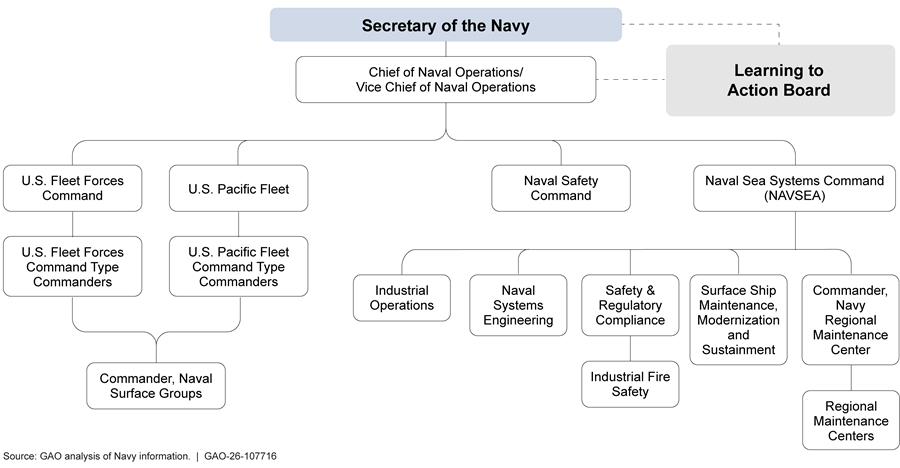

Navy’s Organizational Structure for Fire Safety Oversight

Navy organizations and commands across the Navy enterprise share responsibilities for providing fire safety, prevention, and response in areas such as oversight, training, and assistance for ships undergoing maintenance. Figure 4 lists key organizations responsible for fire safety oversight.

Figure 4: Key Navy

Organizations with Fire Safety Oversight Roles and Responsibilities for Ships

Undergoing Maintenance![]()

The Learning to Action Board—cochaired by the Under Secretary of the Navy and Vice Chief of Naval Operations—was established in November 2021. The intent of the board is to drive transparency and accountability for implementing and assessing corrective actions from reviews, investigations, reports, and studies, including from major incidents. These studies and investigations included the Major Fires Review, a comprehensive review of 15 major fires that occurred from 2008 through 2020. They also included the command investigation of the USS Bonhomme Richard fire.

In April 2023, we found that the Navy had taken initial steps through its Learning to Action Board to address some of the actions identified in the Major Fires Review.[12] We also reported that Navy organizations have ongoing efforts to improve safety, such as collecting and analyzing lessons learned from fires. However, the Navy did not have a process for consistently collecting, analyzing, and sharing these lessons learned across the Navy. We made three recommendations, including that the Navy establish a process for consistently collecting and sharing lessons learned.[13]

NAVSEA and its subordinate organizations help maintain ships to meet fleet requirements within cost and schedule goals, among other duties.

· Director, Surface Ship Maintenance, Modernization, and Sustainment (NAVSEA 21) manages life-cycle support for all nonnuclear surface ships and is responsible for the maintenance and modernization of surface ships operating in the fleet.[14]

· Commander, Navy Regional Maintenance Center (CNRMC) oversees the Navy’s RMCs. The RMCs provide ship repair, industrial, engineering, and technical support services for ships, including procurement, administration, and oversight of contracts for ship maintenance and modernization. Each RMC includes divisions and personnel that carry out oversight duties, including safety, quality assurance, production, and contracting divisions.

· NAVSEA Contracts awards contracts for large and complex ship maintenance and modernization, while the RMCs administer them.

Office of Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) is the office of the senior military officer of the Department of the Navy, overseeing the Navy’s fleet, among other organizations.

Commander, Naval Surface Forces of the Navy, including the fleet type commands (Surface Force Atlantic and Surface Force, U.S Pacific Fleet), typically assume full responsibility for manning, training, and equipping surface ships. Commander, Naval Surface Groups are responsible for the emergency management command and control structure for nonnuclear warships during shipboard safety incidents, among other things. These groups report to the fleet type commands.

Navy Implemented Actions After USS Bonhomme Richard Fire, but Staffing Shortfalls Threaten Continued Progress and Oversight

The Navy identified and implemented some actions related to fire safety in response to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. These actions have improved fire safety across the Navy ship maintenance enterprise and contributed to zero major fires since July 2020. However, staffing shortfalls across organizations responsible for implementing these actions limit the Navy’s ability to implement fire safety standards and contractor oversight practices. Specifically, the Navy is experiencing personnel shortages across organizations it established or modified in response to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire.

Navy Implemented Actions to Improve Fire Safety Oversight

The Navy implemented several actions to improve its oversight of fire safety standards following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and the subsequent July 2021 Major Fires Review. Specifically, the Learning to Action Board developed 220 items that it categorized into 11 topics to address findings from these reviews. The 11 topics cover a wide variety of fire safety issues, such as improving command and control across multiple organizations during a major fire event, implementing a formal process for pier-side fire protection requirements, and improving firefighting training. As of July 2025, the Navy had implemented nine of the 11 topics with two in progress. The Learning to Action Board considers a topic implemented when it transfers the topic to the owning organization(s) responsible for incorporating the changes. The Learning to Action Board plans to continually assess whether the actions within each topic are achieving intended outcomes. See table 1 for the status of the board’s topics.

|

Topic |

Statusa |

Number of action items per topic |

|

Modify Naval Safety Command missions to better address near-misses and minor events |

Implemented |

12 |

|

Develop ship safety system that identifies and corrects problems before becoming systemic issues |

Implemented |

6 |

|

Revise fleet organization relationships to improve coordination between various organizations during a maintenance availability |

Implemented |

9 |

|

Implement independent oversight model that evaluates and tracks compliance with the Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response, and revise the manual |

Ongoing |

40 |

|

Reconcile fire safety practices at public and private shipyards |

Implemented |

43 |

|

Improve organizational learning across the Navy |

Implemented |

23 |

|

Prioritize funding for automated shipboard fire detection, suppression, and firefighting systems |

Implemented |

7 |

|

Eliminate organizational ambiguity for fire safety during ship maintenance |

Implemented |

40 |

|

Implement formal process to improve pier-side fire protection compliance |

Ongoing |

16 |

|

Improve firefighting school training and career paths |

Implemented |

21 |

|

Address arson concerns through insider threat training and other methods |

Implemented |

3 |

GAO analysis of Navy data. I GAO‑26‑107716

Note: The information included in the table summarizes the Learning to Action Board topics and does not include all details for each topic.

aImplemented status reflects that the Learning to Action Board transferred the topic to the owning organization(s) responsible for incorporating the changes. The Learning to Action Board conducts periodic reviews of completed action items to ensure long-term implementation and assess the impact of implementation.

Within these topics, we identified the specific actions taken by the Navy that are related to oversight of ship crew or ship repair contractor compliance with fire safety standards. According to officials across the Navy, these changes have begun to improve the Navy’s fire safety culture during surface ship maintenance periods and contributed to zero major fires since July 2020. Specific actions taken by the Navy include:

· Revised Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response (8010 Manual). In August 2023, the Navy revised the 8010 Manual to:

· reflect some updated requirements for fire safety exercises;

· update direction for ensuring maintenance work is planned and executed to minimize the time when firefighting systems are out of service; and

· clarify the lines of authority, responsibility, and oversight if a ship’s force demonstrates substandard performance during training events, among other things.

The 8010 Manual revision was a complete rewrite from the previous version to improve fire safety principles. In November 2024, NAVSEA officials stated that the Navy is now beginning to assess the effectiveness of the 8010 Manual requirements to help inform future updates.

· Established a single NAVSEA Standard Item for Fire Safety. NAVSEA Standard Items are the requirements that contractors must follow, when they are embedded in the contract. In October 2022, via the release of the fiscal year 2024 NAVSEA Standard Items, CNRMC combined three NAVSEA Standard Items that included fire safety requirements into one consolidated NAVSEA Standard Item. This item contains fire safety requirements that are generally the responsibility of a contractor to follow. As part of this process, the Navy, with industry input, revised the NAVSEA Standard Items to better align with the fire safety standards included in the 8010 Manual. NAVSEA officials stated that they reassess fire safety standards included in the NAVSEA Standard Items on an annual basis.

· Created Area Command Organizations (Surface Groups). In September 2023, the Navy began establishing 11 Commander, Naval Surface Groups across the Navy’s fleet concentration areas. The intent of the new organizations was to simplify and lead the emergency management command and control structure for nonnuclear warships during shipboard safety incidents, among other things. Previously, these duties were fragmented across multiple Navy organizations. Once these groups are fully operational, they will also perform several fire safety roles. These roles include developing emergency response plans, working with ships’ crews to help them understand fire regulations, leading fire response, and conducting fire safety inspections.

· Improved Fire Safety Council. The Navy updated the membership qualification and representation requirements of the Fire Safety Council. This organization is responsible for ensuring compliance with fire safety standards during a ship’s maintenance period. The Navy also expanded the role of the Fire Safety Council to include the identification, elevation, and mitigation of risks when the 8010 Manual requirements will not be met. For instance, there can be circumstances in which compliance with the 8010 Manual is cost prohibitive or excessively complicates maintenance. In these instances, the Fire Safety Council reviews the Navy’s plans to mitigate fire risk and submits these plans to leadership.

· Increased Fire Safety Officer Staff. Following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire, the Major Fires Review identified that staffing shortfalls across the RMCs prevented the Navy from adequately carrying out fire safety oversight. In April 2022, CNRMC reported that RMCs were not resourced to support the 8010 Manual staffing requirements of one fire safety officer per one major ship maintenance period and one fire safety officer for every two minor ship maintenance periods.[15] Since that time, the Navy has increased civilian fire safety officer staffing across its RMCs.

· Implemented Fire Safety Assessment Program. In August 2022, Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic published the revised Fire Safety Assessment Program policy.[16] This policy outlines responsibilities for enforcing compliance and improving understanding of the risks associated with fire onboard surface ships during maintenance periods. Through the program, Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic conduct “no-notice” inspections on ships undergoing maintenance, among other actions.

In addition to the positive actions taken to date, the Navy also updated its Lessons Learned Program instruction in January 2024 in response to our previous recommendation.[17] The updated lessons learned guidance directs the Commander, Naval Safety Command to review mishap investigation reports, identify and analyze selected reports containing information of value to Navy organizational learning, and upload the reports to its lessons learned system. By implementing our recommendation to share fire-related lessons learned, the Navy is better positioned to improve behavior and reduce the risk of costly mistakes should a fire occur during a ship maintenance period. However, the Navy has yet to implement two additional recommendations we made related to analyzing fire incident data and establishing service-wide goals and performance measures for fire safety training activities.

Personnel Shortages Limit Navy’s Ability to Fully Implement Actions Taken

While the Navy has taken positive actions to address oversight of fire safety through its Learning to Action Board topics, staffing shortfalls across various organizations limit its ability to continue to implement these fire safety standards and oversight practices. The Navy previously reported that staffing shortfalls contribute to the risk of fire incidents. For instance, staffing shortages can leave key organizations without personnel to cover after-hours and weekend duties. The Navy’s Major Fires Review found that 11 of the 15 fire events included in the review occurred outside of the normal workday or workweek, or during holidays.

All three organizations responsible for fire safety oversight during ship maintenance reported having staffing shortfalls as of March 2025. Table 2 outlines the responsibilities and staffing levels for these Navy organizations responsible for fire safety oversight during ship maintenance.

Table 2: Responsibilities and Reported Staffing Levels of Navy Organizations Responsible for Fire Safety During Ship Maintenance Periods as of March 2025

|

Key organizations |

Primary fire safety role(s) |

Navy fire safety staffing levels as of March 2025 |

|

Regional maintenance centers (RMC) |

Conduct daily inspections and appoint the chair of the Fire Safety Council to ensure compliance with fire safety requirements. |

7 of 46 positions vacant. RMC officials stated that they need 21 additional full-time fire safety positions in addition to the 46 positions (67 total) to meet 8010 Manual requirements.b |

|

Commander, Naval Surface Groups |

Lead the response to a major fire; conduct progress-based fire safety inspections on ships undergoing maintenance; and support the ships’ crews in understanding fire safety regulations and oversight; among other things. |

9 of 20 positions vacant. Naval Surface Group officials stated that they need at least seven additional full-time fire safety positions in addition to the 20 positions (27 total). |

|

Type commands |

Carry out the Fire Safety Assessment Program, which includes “no-notice” inspections.a |

2 of 17 positions vacant. Fleet officials stated that they need seven additional full-time fire safety positions in addition to the 17 positions (24 total). |

Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation and interviews with Navy officials. I GAO‑26‑107716

Note: The table reflects personnel information for the following organizations: Mid-Atlantic RMC; Southeast RMC; Southwest RMC; RMC Northwest; Commander, Naval Surface Group Middle Atlantic; Commander, Naval Surface Group Southeast; Commander, Naval Surface Group Southwest; and Commander, Naval Surface Group Northwest. Type command reflects Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic.

aNo-notice inspections are fire safety assessments carried out by Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic on ships in port.

bNaval Sea Systems Command, Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response, Rev. 1, Technical Publication S0570-AC-CCM-010/8010 (Aug. 30, 2023).

Addressing these shortfalls will take years as the Navy has yet to fully budget for these positions. Further, because of civilian workforce hiring limitations put in effect in January 2025 by the Secretary of Defense in response to a presidential order, most of the RMCs we met with and the type commands have delayed hiring fire safety staff.[18] According to these officials, the Navy now needs additional fire safety officers in the near term to support the fiscal years 2026 and 2027 ship maintenance schedules. However, the current budget requests for these years do not include funding sufficient to hire the total fire safety staff necessary to meet maintenance demands. Further, officials stated that RMC staffing is based on the Office of Chief of Naval Operations maintenance model. In contrast, fleet staffing (Naval Surface Groups and type commands) is determined by a separate process. Thus, there is no mechanism, such as documented agreements, that maximizes available resources across the RMCs and fleet organizations to ensure an appropriate number of personnel to conduct fire safety oversight onboard ships during maintenance periods.

The Department of Defense’s October 2019 Fire and Emergency Services Program instruction states that DOD components will develop fire prevention programs to provide a safe environment at installations.[19] Further, the instruction states that proper staffing is critical to establishing and maintaining a quality fire prevention program. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that when designing an internal control system, management should balance the allocation of resources with the degree of risk, complexity, or other factors relevant to achieving the entity’s objectives. Further, management is responsible for evaluating pressure on personnel to help personnel fulfill their assigned responsibilities in accordance with the entity’s standards of conduct.[20]

To mitigate the staffing shortfalls across the RMCs, Naval Surface Groups, and type commands, these organizations can rely heavily on ship crews to monitor contractor performance and notify the RMC if safety issues arise. Doing so, however, adds further burden on the ship’s crew, who are also often operating with reduced personnel. In September 2024, we reported the Navy assigns fewer sailors fleetwide than required aboard ships because it does not fill all required ship positions, ensure sailors assigned to a ship are available for duty, and ensure sailors are prepared for positions they fill.[21]

All six ship crews that we interviewed said that they were operating with reduced personnel—including one ship that was operating at 55 percent of its recommended crew size that should have been on board during the maintenance period. The Navy’s July 2021 Major Fires Review found that a majority of fire events had occurred during maintenance periods and with reduced personnel levels. Specifically, 11 of the 15 fire events included in the review occurred outside of the normal workday or workweek when there were additional reductions in the number of ship personnel on duty. Reduced crews meant there were smaller crews available to detect a fire and fewer crewmembers to respond to fires. In April 2023, we reported that reduced personnel levels on ships during maintenance has contributed to the risk of fire incidents.[22]

Ship personnel may leave the ship during maintenance periods due to taking leave, fulfilling training requirements, or deploying to other missions.[23] Further, three of the six crews we met with told us that they have a limited number of damage control personnel. Damage control personnel include the engineer officer, damage control assistant, and fire marshal. These personnel are responsible for maintaining a ship’s propulsion plant and electric power generators, repairing a ship’s hull, and preventing and fighting fires, among other duties.

In many cases, crews take on routine fire safety tasks during maintenance in addition to their full-time duties. Further, on every ship we visited, we found examples where the ship’s crew reported having to take action due to Navy shortfalls or contractors not complying with fire safety standards. These examples add to the stress on the ship’s crew to keep the ship safe. As this stress builds, according to Navy investigations and leaders we met with, the accumulation of risk and burden can lead to hazardous situations—such as major fires—during ship maintenance periods. Examples of the ship’s crew taking action include the following:

· Mitigate inadequate contractor fire watch personnel. Per the NAVSEA Standard Items, when included in relevant contracts, contractors are required to provide trained fire watch personnel to monitor active hot work sites to ensure a fire does not occur. Five of the six ship crews we interviewed expressed distrust of contractor fire watch personnel. Multiple RMC officials and ship commanding officers explained that contractor fire watch personnel are often found on their phone, not paying attention, ill-equipped, and, in some cases, not present while hot work is being done. When fire watch personnel fail to meet fire safety standards, ship crew and fire safety officers either must stop hot work—thereby delaying work—or reallocate crew resources to ensure fire safety standards are met. Officials we met with recalled an incident where a fire started, and the crew had to put out the fire because the contractor’s fire watch personnel were not performing their responsibilities.

· Hot work site inspections. The 8010 Manual states that the contractor is to submit all hot work permits to the ship’s crew the day before the contractor plans to execute the work. To approve the permits, the crew is required to inspect every hot work site each day, which can range from up to 50 to 150 sites, depending on the ship class. However, the contractor may not conduct hot work at all approved sites. For example, the Navy’s NAVSEA Standard Items do not include a percentage of the total number of hot work permits the contractor must work in a day. Five of the six ships crews we interviewed noted that completing the daily hot work inspections was a significant burden on the crew. Crews also noted examples where they would inspect hot work sites and the contractor would not complete the work. The contractor would then submit a permit the next day and the crew would have to reinspect the same site again since the site conditions may have changed. In October 2022, the Navy sought to reduce the burden on the ship’s crew by releasing the fiscal year 2024 NAVSEA Standard Items that limit the number of hot work permits the contractor can submit in a single day.

The Navy’s personnel shortages across the organizations identified in table 2 further add to this burden as crew members often complete tasks that would otherwise be done by other staff were there no shortfalls. For example, one ship commanding officer told us that the ship’s crew tells contractors when they violate fire safety standards, but the ship needs additional fire safety officers from the RMC to effectively ensure that contractors correct their behavior and follow fire safety standards. Further, personnel shortages at the RMCs add risk to the ship maintenance period because ship personnel rely on the Navy’s RMCs for authority to instruct contractors. For example, a commanding officer can ask a contractor to address a nonconformance, such as a fire safety violation. However, if the contractor refuses to address the concern, the ship’s crew must report the incident to the RMC to officially notify the contractor.

All these factors that burden the crew may contribute to increased risk of a preventable fire that can damage a ship or harm personnel during a maintenance period. A Navy investigation and our previous reports demonstrate that overly stressed crew members can make the ship more vulnerable to potential accidents or losses, such as arson, as has occurred during prior maintenance periods.[24] In all, the ship’s crew can compensate for shortages among the organizations in table 2. However, without a mechanism, such as documented agreements, that outlines processes for maximizing existing resources across organizations carrying out fire safety oversight on ships in maintenance, the Navy is vulnerable to the accumulation of fire safety risks during maintenance periods, such as those experienced prior to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire.

Navy Can Improve Oversight Tools to Address Contractor Fire Safety Compliance During Ship Maintenance Periods

The Navy found that ineffective contractor oversight played a key role in the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. However, the Navy has yet to fully address challenges with its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards, in part because data on prior contractor compliance issues were not included in its investigations. Further, the Navy’s use of contractor oversight and accountability tools are largely ineffective at ensuring compliance with fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods.

Navy Did Not Fully Assess Known Contractor Oversight Issues That Contributed to USS Bonhomme Richard Fire

The Navy has not fully addressed challenges with its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards, though it concluded its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards was a contributor to the severity of the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. The Navy’s Learning to Action Board was tasked with developing actions to address lessons learned based on information included in the Major Fires Review and the Navy’s investigation into the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. However, we found that the board did not have all relevant information on existing contractor compliance issues to understand and prioritize contractor oversight as one of its topics. For example, neither the Navy’s Major Fires Review nor the Navy’s investigation into the USS Bonhomme Richard fire mentioned that a Method D Corrective Action Request (CAR) was issued in July 2019 by Southwest RMC. The CAR issued to the contractor documented a pattern of serious fire safety violations across multiple ships, including USS Bonhomme Richard. Additionally, these investigations failed to include other instances in which fire safety CARs were issued to the same contractor prior to and after the fire. Thus, the Learning to Action Board did not have the necessary information to address Navy oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards through its topics or corrective actions.

Specifically, we analyzed the Navy’s investigation of the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and CAR data before and following the fire. We found that the investigation excluded important data showing that ineffective oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards was a known issue prior to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and on other ships in maintenance periods following the fire. Table 3 provides the timeline for the documented fire safety events that led up to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and indicates whether these events were included in the Navy’s major investigation.

Table 3: Timeline of Contractor Fire Safety Performance Events Related to USS Bonhomme Richard Fire and Whether They Were Captured in the Navy’s Investigative Report

|

Event date |

Description |

Addressed in official Navy investigation of USS Bonhomme Richard fire |

|

July 2019 |

USS Bonhomme Richard Commanding Officer requested that all work stop due to multiple safety incidents involving contractor employees on the ship, including a fire. |

No |

|

July 2019 |

Navy’s Southwest Regional Maintenance Center issued a Method D Corrective Action Request (CAR) to the contractor due to systemic failure to maintain fire prevention during work on multiple ships, including USS Bonhomme Richard. |

No |

|

September 2019 |

Navy Fire Safety Officer position for the USS Bonhomme Richard became vacant. |

Yes |

|

January 2020 |

Navy’s Southwest Regional Maintenance Center closed Method D CAR as “satisfactory.” |

No |

|

March 2020 |

Navy’s Southwest Regional Maintenance Center issued a Method B CAR to the contractor after a minor fire occurred due to the contractor failing to follow fire safety standards. |

No |

|

July 2020 |

Major fire occurs on the USS Bonhomme Richard, resulting in the loss of the ship. |

Yes |

Source: GAO analysis of Navy documentation. I GAO‑26‑107716

Note: The Navy’s Southwest Regional Maintenance center issued at least five Method C or D CARs to the same contractor due to various systemic fire safety violations on multiple other ships between January 2021 and February 2023.

Navy guidance states that the Learning to Action Board shall implement a structure, process, and forum that drives transparency and accountability on matters that have Navy-wide importance.[25] Further, the board shall set objectives and outcomes for task recommendations, identify single accountable individuals, recommend the removal of or remove barriers, and where appropriate, advocate for resources for recommendation implementation. In all, the board is chartered to address the major issues that contributed to the incident under investigation. However, in establishing its action items pursuant to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire, the board did not have information about instances in which the Navy identified significant deficiencies in the contractor’s compliance with fire safety standards. Data on contractor compliance with fire safety standards, such as CARs, provides Navy leadership with insight into contractor performance and issues that put ships and their crews at risk during a maintenance period. Since key CAR data were not included in the Navy’s investigation report, the Learning to Action Board missed an opportunity to address known critical issues that factored into the severity of the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. Without reviewing key contractor oversight data, such as CAR data, the Navy may not address all areas that have a critical impact to fire safety.

Navy’s Use of Existing Tools Does Not Ensure Contractor Accountability for Compliance with Fire Safety Standards

The way the Navy currently uses its oversight and accountability tools inhibits its ability to adequately correct behavior when contractors fail to meet fire safety standards. For example, the Navy uses several contract oversight tools, but, in general, has not used these tools effectively to significantly change contractor behavior when contractors fall below required levels of performance outlined in the contract, including fire safety standards. In December 2024, we reported that Navy RMC leadership provided interim guidance in November 2018 that, effective immediately, RMCs were not to assess any monetary penalties through QASPs and liquidated damages to ship repair contractors without NAVSEA senior leadership approval.[26] In February 2025, the Navy issued guidance establishing procedures for RMCs to enforce monetary penalties through QASPs and liquidated damages. However, NAVSEA senior leadership approval is still required for RMCs to enforce monetary penalties. Additionally, the Navy has not recently updated its COVID-19-era policy on progress payment retention or revisited the limitation of liability clause. These tools are available to protect the government in the event of loss or damage to a ship in maintenance.

We identified five key oversight and accountability tools for ensuring that contractors comply with fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods and protect the government’s interests: (1) CARs, (2) QASPs, (3) progress payment retention rates, (4) a limitation of liability clause, and (5) the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS).

Corrective Action Requests

CARs are the Navy’s primary tool for addressing ship repair contractor fire safety violations. However, the Navy has not effectively used CARs to fully address recurring fire safety issues in the 5 years since the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. For the six selected ships we reviewed, all of which have undergone maintenance following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire, we found that the Navy issued 343 CARs, including five Method C or D CARs to four contractors for fire safety.[27] Officials stated that this number of fire safety violations reflects, in part, the increased oversight by the fire safety officers and other RMC officials since the USS Bonhomme Richard fire. Fire safety CARs, as opposed to CARs related to work quality, comprise 42 percent of total CARs issued for these ships.

For the six selected ships reviewed, we found that contractor noncompliance with fire safety standards were often recurring in nature. For example:

· In August 2024, the Navy issued a letter of concern to a contractor highlighting that even with 75 CARs being issued for various safety nonconformities—mainly fire safety—over the maintenance period, it had observed little improvement. Following this letter, safety issues persisted, resulting in the Navy issuing 22 additional fire-safety-related CARs from August 14, 2024 to October 15, 2024.

· In January 2024, the Navy issued a letter of concern to a contractor highlighting that the Navy had issued 105 CARs for infractions related to quality, management, and safety during the maintenance period. Following this letter of concern, between February 2024 and September 2024, it issued 47 additional CARs for fire-related nonconformities. Many of these nonconformities were for similar violations that were documented in the January 2024 letter, such as failure to: (1) comply with fire zone boundaries, (2) maintain the cleanliness of the work site, and (3) remove combustible material from hot work areas.[28]

· In June 2022, the Navy issued a Method C CAR to a contractor related to failures in maintaining safety and fire prevention standards during a ship maintenance period. Then, in February 2023, the Navy issued a Method D CAR to the same contractor after it failed to adequately address the previously issued Method C CAR. Following the issuance of the Method D CAR, the Navy issued six additional Method A and B CARs for similar violations.

We found that the Navy does not assess monetary penalties associated with CARs, regardless of the severity of the CAR. Data we reviewed illustrate that CARs do not lead to long-term improvements by contractors to address the occurrence of fire safety violations. RMC and fleet officials attribute the ineffectiveness of CARs to the fact that there are no monetary penalties linked to the issuance of repetitive CARs. This diminishes the urgency for contractors to address performance issues and allows serious safety violations to persist. In addition, crews from five of the six ships we met with told us that CARs had little to no long-term effect on contractor behavior. Similarly, officials we met with from all four RMCs stated that CARs are short-lived and often do not drive long-term changes. They added that issuing a Method D CAR often results in the Navy “resetting the clock” on cumulative violations that result in Method A or B CARs even if the underlying issues are not addressed.

The Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual states that RMCs should use CARs to request that contractors resolve nonconformities—including safety and quality deficiencies—before they become recurring issues. The manual states that when responding to CARs, contractors must rectify major, systemic, or critical nonconformances at their root causes to assure compliance, rather than merely correcting individual violations. Further, contractors are to be required to rectify specific nonconformities and implement preventative measures to eliminate their underlying causes.[29]

While the manual outlines that contractors must rectify non-conformances at their root causes, the same fire safety issues continued to resurface across the six ships we reviewed. Without assessing how to improve the CAR process to address contractor accountability when contract standards are not met—including how to use monetary penalties for serious fire safety issues—the Navy limits its ability to lessen the risk of fires during ship maintenance periods.

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans

QASPs in ship maintenance contracts, prepared by Navy acquisition officials, are a quality assurance tool used during contract performance to measure performance against established metrics for acceptable quality.[30] DOD generally requires a QASP be prepared for contracts for services, tailored to address the performance risks inherent in the work effort.[31] CNRMC’s February 2025 QASP guidance states that QASPs should provide the performance criteria, standards, and procedures for the government’s surveillance and oversight of the contractor’s performance to assure deliverables are timely and complete, and to assure performance is meeting the requirements specified in the contract.[32] The guidance further states that the QASP is a tool to assess monetary penalties for failure to meet contract performance standards. These standards include contract requirements related to safety specified in ship maintenance contracts, via NAVSEA Standard Items, that ship repair contractors are required to follow.

The Navy’s QASP guidance contains a template for noting which assessment areas a QASP should include, such as the timely submission of schedule and staffing reports, among other deliverables. However, the Navy’s guidance does not include safety as an assessment area. Therefore, the Navy does not structure its QASPs to enforce contractor compliance with safety standards or associate monetary penalties when contractors do not comply with safety standards included in ship maintenance contracts.

Furthermore, draft QASP guidance included a provision that associated monetary penalties with contractor responsiveness to CARs, but the published guidance does not include this provision. According to CNRMC officials, the provision was removed from the QASP guidance because CNRMC determined that QASP-related penalties were less impactful than taking actions against a contractor’s Quality Management System.[33] Such actions could include decertification. However, RMC officials stated that they have not decertified a contractor’s Quality Management System based on safety violations. We also found that the current Quality Management System process does not include information on contractor adherence to fire safety standards.

While assessment of penalties is made at the discretion of the contracting officer, we found that none of the six ships we reviewed included safety compliance in their QASP or administered a QASP penalty for fire safety even with hundreds of fire safety violations. In effect, the Navy does not use QASPs for ensuring safety in compliance with the contract. As a result, the Navy is missing an opportunity to strengthen oversight and mitigate risks associated with repeated contractor safety violations, including fire safety. Without updating the Navy’s QASP guidance to include safety compliance and CAR responsiveness as assessment categories, the Navy is not using this critical tool to ensure contractor compliance with fire safety standards, which may increase the likelihood of a major fire incident.

Progress Payment Retention Rates

Progress payments are a type of contract financing that provides cash flow to a contractor during contract performance, including for ship maintenance periods. However, contract administration officials are required to retain funds sufficient to protect the government’s interest. The Navy’s continued use of a retention rate implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic reduces the amount available for this purpose. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Navy used a progress payment rate of 90 percent, and withheld 10 percent of payments until the work was completed (referred to as 10 percent retention rate). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Navy reduced retentions to provide ship repair contractors with additional cash flow. Specifically, on March 24, 2020, Navy contracting leadership issued a memorandum directing the NAVSEA contracting enterprise to temporarily reduce retentions from 10 percent to 1 percent. A 1 percent retention rate means that the government has retained less money for protection prior to the contractor completing the ship maintenance period. During the same period, DOD similarly reduced its retention rate for large businesses from 20 percent to 10 percent and for small businesses from 10 percent to 5 percent in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[34]

The Navy adjusted the retention rate in response to a national emergency but continues to utilize a 1 percent retention rate for ship maintenance contracts, as of May 2025, even though the national emergency is now over, according to NAVSEA officials. In contrast, following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, on May 8, 2023, DOD reinstated its pre-pandemic progress payment retention rate of 20 percent for contracts awarded to large businesses on or after July 7, 2023—except for Navy maintenance contracts.[35] In May 2024, we reported that DOD reinstated its pre-pandemic progress payment retention rate after it completed an assessment of the effect its contract financing policies have on the defense industry, including evaluation of contractor cash-flow and industrial base health.[36] Based on this assessment, DOD proposed several actions, including the decision to return to the customary progress payment rate of 80 percent for large businesses and retain the 95 percent for small businesses set in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2025, NAVSEA officials told us they are considering increasing the retention rates to pre-pandemic levels but had yet to assess the effects the 1 percent retention rate for ship maintenance contracts has had on the government and the ship repair industrial base.

While retentions are not monetary penalties, Navy contracting officials told us that the decision to adjust retention rate levels is a risk-based judgment. The Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) clause for progress payments for ship maintenance contracts gives the contracting officer discretion to set the retention amount, within the parameters of statute.[37] Increasing the retention rate provides the Navy with funds to retain until successful contract completion, including meeting performance standards. For example, in October 2022, a contracting officer increased the retention rate on one contract we reviewed from 1 percent to 10 percent for 11 months due to the contractor’s lack of supervision and persistent safety concerns. These concerns included excessive flammable materials on the ship, poor housekeeping, safety violations during welding and metal cutting, and broader fire and safety risks. Based on our review of the contracts and an interview with Navy contracting officials, we found that the Navy did not adjust the retentions on the other five contracts in order to motivate contractor improvements in meeting safety standards.

The 1 percent COVID-19-era reduced retention rate is still in place at the Navy. Although officials said they would reconsider it, they have yet to do so. Reassessing this lowered rate—based on an analysis that balances the government’s risk and the health of the ship repair industrial base—would position the Navy to determine whether this practice is sufficiently effective to help address risks associated with contractor failure to meet contract requirements, including those pertaining to fire safety to protect the government’s interest.

Financial Liability

Navy ship repair contractors have limited financial liability in the event of a major fire during a ship maintenance period due, in part, to the limitation of liability clause for ship maintenance contracts. For example, the DFARS states generally that in ship maintenance the government assumes the risks of loss and damage to its property.[38] The DFARS also provides for the inclusion of a clause in certain contracts for repair of vessels, which states that the contractor shall exercise its best efforts to prevent accidents, injury, or damage to all employees, persons, and property, and to the vessel or part of the vessel upon which work is done.

In addition, a contract clause limiting a ship repair contractor’s financial liability in the event of a major loss or damage has not been adjusted since August 2003, when DOD set the liability amount to $50,000.[39] At the time, the limitation was increased from $5,000 to $50,000 after the Navy found that only 30 percent of contractor-incurred damages for ships in maintenance in a 3-year period were for $5,000 or less. However, due to inflation and the increasing length and scope of ship maintenance, the Navy does not have the same level of coverage as it did when it instituted the limitation. Factoring in inflation, $50,000 in fiscal year 2003 would be equal to nearly $83,000 in 2025—a 66 percent increase. The current $50,000 liability coverage proportionally provides less coverage when comparing the cost of a modern major ship maintenance period, which has gotten more complex and expensive in recent years, according to an RMC official. For example, the USS Bonhomme Richard maintenance period totaled $215 million worth of work on a multibillion-dollar ship.

In its 2003 assessment and revision of the liability clause, DOD reported in the Federal Register that the decision to increase the amount was driven, in part, by the need to incentivize contractors to reduce the number of contractor-caused damages, thereby improving ship maintenance. Further, DOD reported that the liability limitation increase was consistent with the commercial insurance practice of setting a deductible that lowers claim frequency, eliminates insubstantial claims, and provides an incentive for the insured to avoid losses.

Defense Pricing, Contracting and Acquisition Policy officials—who are responsible for DOD contract policy matters—stated that additional studies by the Navy are necessary to determine whether the current liability ceiling has been an effective tool for preventing losses or whether it should be increased. Further, Navy contracting officials said studies are needed to assess whether the average contractor-incident amount has increased above the $50,000 threshold. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that risk responses may include action taken to transfer or share risks across the entity or with external parties, such as insuring against losses.[40] Revisiting the DFARS 252.217-7012 liability clause to assess whether the current liability amount is still appropriate for ship maintenance provides an opportunity for the Navy to consider whether an increase would align risk sharing between the Navy and its contractors as well as incentivize contractors to take steps to prevent losses, such as from fires. If warranted, this assessment would position the Navy to recommend the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to update the DFARS clause to reflect the increased liability amount.

Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System

NAVSEA officials pointed to the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS) as another oversight mechanism to ensure contractor compliance with fire safety standards. CPARS is the government’s tool for evaluating and reporting on the contractor’s performance at certain intervals. However, despite several requests during our review, the Navy could not provide evidence that fire safety information was used to inform CPARS evaluations, even in instances when several higher-level CARs had been issued for fire-safety-related noncompliances. Additionally, in December 2024, we reported that Navy maintenance officials did not consistently complete CPARS evaluations as required for numerous reasons, such as they did not know it was required. We found that until the Navy consistently completes CPARS evaluations, it is at risk of not having the ability to fully evaluate and use past performance in awarding future contracts.[41] We recommended that the Navy reassess its approach to overall quality assurance, including the completion of CPARS evaluations. The Navy concurred with our recommendation, and it currently remains open. Further, legislation for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2026 includes a provision for DOD to revise CPARS regulations, including mandatory reporting of certain performance events, such as documented non-compliance with safety requirements.[42]

Conclusions

In July 2020, the Navy lost a multibillion-dollar ship during a major ship maintenance period due to a fire that became uncontrollable from significant flammable materials located in a vehicle stowage space on the ship. The Navy has made significant changes following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire to focus on improving fire prevention and response. Overall, these changes have helped to shape a cultural shift toward valuing fire safety within the Navy. However, without fully addressing oversight of contractors performing hot work and other dangerous ship maintenance tasks, the Navy risks creating an environment where unaccounted-for risks can accumulate in a manner that creates hazardous situations.

For example, the Navy identified several positions and organizations following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire to improve fire safety, but personnel shortfalls threaten the effectiveness of these organizations. These shortfalls place more burden on the ship’s crew who have the ultimate responsibility to protect the ship but have little authority to oversee the contractors. In turn, this increases the stress on the crew and the likelihood of risks accumulating to the point that the ship is vulnerable to catastrophic events, such as a major fire.

Further, following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire, the Navy has not fully addressed challenges with holding contractors accountable for complying with fire safety standards. We found that the Navy has several tools available to oversee contractor performance and hold contractors accountable, yet it has limited the effectiveness of these tools to address issues like persistent fire safety violations. In some cases, the current use of these tools, such as QASPs, and lack of updated policy, such as for progress payment retention rates, may increase financial risk to the government. The Navy has set an ambitious goal of having 80 percent of the fleet operationally ready by 2027. Achieving this goal requires increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of ship maintenance. However, without addressing its ineffective use of oversight tools, the Navy continues to face an elevated risk of experiencing a major fire, especially as it tries to speed up and improve ship maintenance to meet future threats.

Recommendations for Executive Action

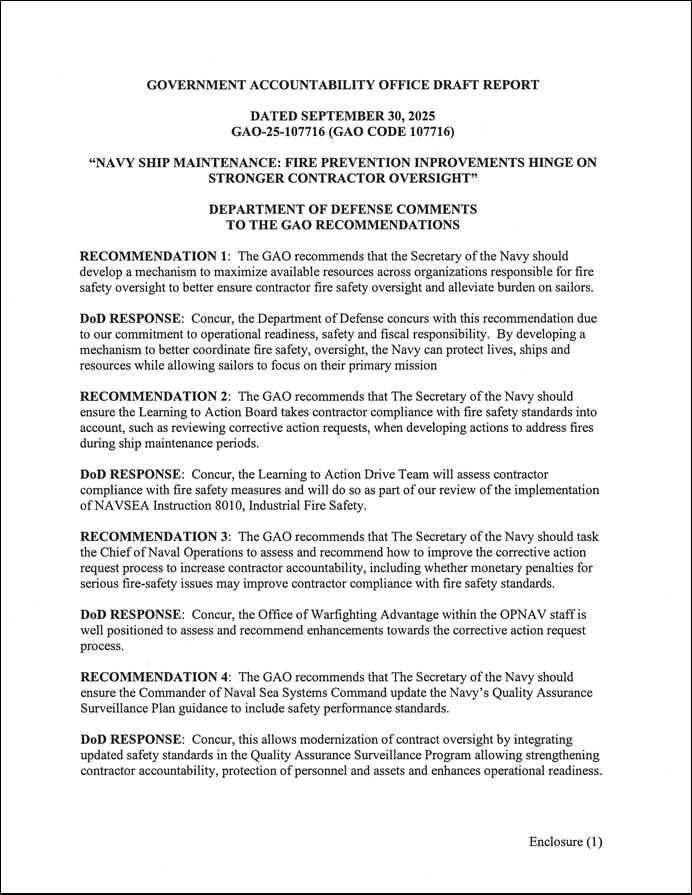

We are making the following six recommendations to the Navy:

The Secretary of the Navy should develop a mechanism to maximize available resources across organizations responsible for fire safety oversight to better ensure contractor fire safety oversight and alleviate the burden on sailors. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Learning to Action Board takes contractor compliance with fire safety standards into account, such as reviewing corrective action requests, when developing actions to address any future major fires during ship maintenance periods. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Navy should task the Learning to Action Board to assess how to improve the corrective action request process to increase contractor accountability, including whether monetary penalties for serious fire safety issues may improve contractor compliance with fire safety standards. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Commander of Naval Sea Systems Command updates the Navy’s Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan guidance to include safety performance standards. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Navy should reassess the progress payment retention rate for surface ship maintenance contracts based on an assessment of the government’s risk and health of the ship repair industrial base. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Navy should reassess the ship repair limitation of liability clause, as outlined in the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement, including whether adjustments to the contractor’s liability ceiling, such as to reflect inflation, are warranted and make a recommendation to the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to update the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement clause. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment in August 2025. In written comments provided by the Navy (reproduced in appendix II) in November 2025, DOD concurred with our recommendations.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and other interested parties, including the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of the Navy. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions concerning this report, please contact me at oakleys@gao.gov. Contact points for our offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Staff members making key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Shelby S. Oakley

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

This report assesses (1) the extent to which Navy actions taken following the USS Bonhomme Richard fire addressed its oversight of contractor compliance with fire safety standards; and (2) the effectiveness of the tools the Navy uses for ensuring contractors comply with fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods.

For the first objective, we reviewed Navy and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives reports on the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and the Navy’s 2021 Major Fires Review to determine what factors contributed to recent major fires and recommendations and lessons learned the Navy identified.[43] We also reviewed Navy documents—including briefing documents, policies, and memorandums—that outlined tasks the Navy implemented in response to the USS Bonhomme Richard fire and the Major Fires Review.

We reviewed the Learning to Action Board topic list to identify the extent to which the Navy developed topics related to addressing its processes for ensuring contractors follow fire safety standards during ship maintenance.[44] Through coordination with the Learning to Action Board, and other relevant officials, we collected documentation on the actions taken in response to the topics and whether the Navy is monitoring the outcomes. We also collected information on staffing levels across the primary organizations that implemented topics and tasks developed by the Learning to Action Board, and which are responsible for enforcing fire safety standards during ship maintenance periods.

We interviewed relevant officials involved in oversight to understand how actions taken have addressed the Navy’s oversight of contractors following fire safety standards. This included:

· Visiting three Regional Maintenance Centers (RMC) in Norfolk, Virginia; Mayport, Florida; and San Diego, California; interviewing officials from RMC Northwest at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard; Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) Surface Ship Maintenance, Modernization and Sustainment; NAVSEA Safety and Regulatory Compliance, Industrial Fire Safety; and Naval Safety Command.

· Meeting with officials from Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic—including officials from four Commander, Naval Surface Groups.

We also requested staffing information from the following organizations responsible for fire safety oversight:

· Mid-Atlantic RMC, Southeast RMC, Southwest RMC, and RMC Northwest, and

· Commander, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic; Commander, Naval Surface Group Middle Atlantic; Commander, Naval Surface Group Southeast; Commander, Naval Surface Group Southwest; and Commander, Naval Surface Group Northwest.

For the second objective, we selected six nonnuclear surface ships that were undergoing major maintenance in fiscal years 2024 and 2025 at Mid-Atlantic RMC, Southeast RMC, Southwest RMC, and Northwest RMC. To assess a variety of ship repair contractors and ship types, we selected ships that reflect work conducted by four major ship repair contractors on amphibious assault ships, Arleigh Burke class destroyers, and a Ticonderoga class guided-missile cruiser. The four contractors were BAE Systems, East Coast Repair, General Dynamics National Steel and Shipbuilding Company (NASSCO), and Vigor Marine. We interviewed officials from BAE Systems, General Dynamics NASSCO, and the Virgina Ship Repair Association, which represents the major ship repair companies, to gain their perspective on various fire safety issues during ship maintenance periods. We reviewed relevant Navy documents, including NAVSEA Standard Items and the Navy’s Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response (8010 Manual), to understand the fire safety standards that contractors and Navy officials are required to follow.[45]