BROADBAND INFRASTRUCTURE

States’ Reported Progress Implementing Requirements to Facilitate Deployment Along Federal-Aid Highways

Report to the Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Andrew Von Ah at vonaha@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

In 2021, the Federal Highway Administration issued a final rule—the “dig once” rule—establishing new broadband infrastructure regulatory requirements for state departments of transportation that receive federal-aid highway program funding. These requirements included (1) identifying a broadband utility coordinator, (2) establishing certain processes to register and notify internet service providers and other entities, and (3) coordinating initiatives with state and local plans.

· Broadband utility coordinator. In GAO’s national survey, 46 of 52 respondents reported their state department of transportation had identified a coordinator.

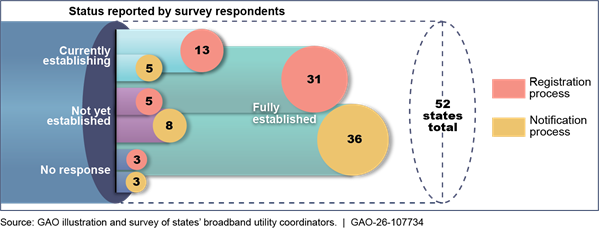

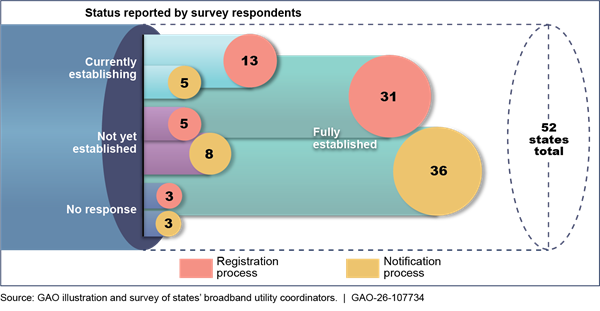

· Registration and notification. Over half of survey respondents reported their state had fully established processes to (1) register internet providers and other entities, and (2) electronically notify them of the state transportation improvement program. A few respondents noted barriers to implementing the processes, including limited availability of experienced staff, IT difficulties, and challenges engaging providers in the processes.

Survey Respondents’ Reported Progress Establishing Registration and Notification Processes Required by the Federal Highway Administration, as of May 2025

· Coordination. In responding to questions related to regulatory requirements for coordination, 46 of 52 survey respondents reported coordinating broadly with federal, state, or local agencies to facilitate broadband infrastructure deployment in federal-aid highway rights-of-way. For example, one respondent reported that the broadband utility coordinator and a county utility committee exchanged details on planned highway and broadband projects at the utility’s monthly meeting.

Survey respondents and stakeholders GAO interviewed said the rule’s effects on broadband deployment were not well known. However, a few respondents, state officials, provider representatives, and other stakeholders cited the overall goals of “dig once” as reasons for optimism. Specifically, they were optimistic about the potential for benefits such as reduced excavation and traffic disruptions, lower project costs, and greater broadband access.

Why GAO Did This Study

Installing the infrastructure necessary to expand broadband access can be costly. “Dig once” policies encourage coordination between broadband projects and road projects, which can minimize excavations and save money.

GAO was asked to review the implementation status of the Federal Highway Administration’s 2021 “dig once” rule that established regulatory requirements to facilitate broadband infrastructure deployment, as required by statute.

This report describes states’ progress implementing certain “dig once” rule requirements and states’ views on the effects of the rule on broadband deployment.

To address these objectives, GAO surveyed all 52 broadband utility coordinators or other appropriate contacts (50 states, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C.). GAO reviewed applicable statutes, regulations, and Federal Highway Administration documentation. GAO also interviewed or obtained written responses from Federal Highway Administration and National Telecommunications and Information Administration officials, and representatives from four broadband industry and state government associations, which GAO selected to obtain a cross section of stakeholder interests.

For three selected states, GAO reviewed documents; interviewed state department of transportation and broadband office officials; and interviewed representatives of five internet service providers. GAO selected these states to reflect a range of factors, based on information including survey responses and experience with broadband deployment projects in federal-aid highway rights-of-way since the final rule took effect.

Abbreviations

BEAD Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment

DOT Department of Transportation

FCC Federal Communications Commission

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

NEC National Economic Council

NTIA National Telecommunications and Information Administration

ROW right-of-way

state DOT state department of transportation

STIP state transportation improvement program

UDOT Utah Department of Transportation

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2026

The Honorable Doris Matsui

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Dear Ranking Member Matsui:

Expanding access to broadband—that is, high-speed internet, an essential service—requires infrastructure. This infrastructure includes “middle-mile” networks, which local internet service providers use to connect to the global internet.[1] According to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), some areas of the country have no middle-mile networks, and other areas are served by only one. To increase coverage and resilience, providers may deploy middle-mile infrastructure (e.g., fiber optic cable) along major transportation routes. Installing this infrastructure can be a costly undertaking, as we have previously reported.[2]

In recent years, Congress has appropriated over $65 billion to support expanding broadband access, including infrastructure deployment.[3] The federal government has a vested interest in maximizing benefits from these investments.

To decrease costs, federal, state, and local governments have explored “dig once” policies to help align excavations when deploying telecommunications infrastructure. For example, a “dig once” policy might encourage state officials to coordinate excavation for a highway project with the installation of pipeline to enclose fiber optic cables for broadband. We and others have reported on the benefits of coordinating projects. For example, in 2012 we found that coordination can reduce the need for multiple excavations.[4] Fewer excavations can decrease construction-related traffic congestion and potentially increase the lifespan of roadways, as frequent construction can reduce the integrity of road materials. We also found that coordination can save money by sharing costs for the road project and broadband infrastructure deployment. (See fig. 1.)

In 2018, the MOBILE NOW Act required the Secretary of Transportation to issue regulations to ensure states receiving certain federal funds meet specific requirements to facilitate broadband infrastructure deployment in the right-of-way (ROW) of applicable federal-aid highway projects.[5] In 2021, the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) issued the broadband infrastructure deployment final rule—commonly referred to as the “dig once” rule—establishing these regulations.[6] FHWA’s regulations generally require state departments of transportation (state DOT) to establish certain processes related to facilitating broadband infrastructure deployment and coordinating initiatives to minimize repeated excavations, so that the state DOTs and internet providers only “dig once” whenever possible.

You asked us to review the status of states’ implementation of FHWA’s “dig once” rule. This report describes states’ progress implementing the rule, which established regulatory requirements to (1) identify a broadband utility coordinator, (2) establish certain registration and notification processes for broadband infrastructure entities (e.g., providers), and (3) coordinate initiatives with other state and local plans, as well as (4) states’ views on the effects of the rule on broadband deployment.

To address each of these objectives, we reviewed relevant documentation. We reviewed applicable statutes and regulations, FHWA’s proposed and final “dig once” rule, and comments on the proposed rule. We examined FHWA documentation, including reports, publications, and presentation materials. We also reviewed our prior work on broadband deployment and the federal-aid highway program.

We surveyed state officials in all 50 states, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia (hereafter “states”). Specifically, to gather information on states’ implementation of FHWA’s requirements and views on the effects of those requirements, we conducted a web-based survey of all state broadband utility coordinators from February 2, 2025, through May 9, 2025.[7] All 52 states completed the online questionnaire.

We pretested the survey with officials from three states to: (1) minimize errors arising from differences in how respondents might interpret questions; and (2) reduce variability in responses due to misinterpretation. We selected the pretest participants to reflect variability in the following characteristics: state office employing the respondent, prior experience with state “dig once” policies, and geographic representation. We revised our survey based on feedback we obtained during these discussions. To reduce nonresponse bias, we followed up by phone or email with states that had not responded to the survey to encourage them to complete it. After closing the web survey, we reviewed the 52 completed questionnaires to check for data entry errors, missing values, and unclear responses. Where necessary for our purposes, we followed up with respondents or reviewed additional information on states’ web pages.

Our survey contained a mixture of closed- and open-ended questions. We analyzed the responses to the closed-ended questions to report the number of responses. For the open-ended questions, we reviewed the responses for illustrative examples or recurring comments. We conducted a content analysis of survey responses to several open-ended questions.[8] In reporting our results, we use “most” to indicate 40 to 51 states, “many” for 26 to 39, “some” for 13 to 25, and “few” for two to 12. See appendix I for more details about the survey, including the questions we asked.

To gain insight into states’ processes and the type of information states requested from broadband providers, we reviewed documentation from 10 selected states’ webpages related to their process for registering providers. We selected these states based on survey responses indicating that the state had (1) fully established or was establishing processes for registering providers and (2) provided a link to the necessary web addresses, as well as based on geographic diversity.[9]

Additionally, we interviewed (or reviewed written responses to questions posed to) federal and state officials as well as four stakeholders (i.e., industry representatives and national associations). These included (1) officials from FHWA headquarters and division offices; (2) officials from NTIA headquarters; and (3) representatives from two broadband infrastructure industry associations and two state government associations, which we selected to obtain a cross section of stakeholders’ interests.[10]

To obtain illustrative examples of selected states’ experiences, we reviewed documents (e.g., websites and policies) and interviewed state DOT and broadband office officials from three states—Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah. We selected these states based on responses to our survey, publicly available information about states’ prior experience with “dig once” policies, examples of coordination on broadband deployment projects since March 2022 (when FHWA’s rule took effect), and recommendations from knowledgeable stakeholders. We selected states to reflect a range of these factors. We conducted a site visit to one of these states (Utah), which we selected due to that state’s experience with implementing “dig once” policies. We also interviewed or received written responses from officials at state audit organizations and representatives of five providers operating in at least one of these three states. These stakeholders provided a variety of perspectives, but their views are not generalizable to those of all stakeholders.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FHWA’s Federal-Aid Highway Program

The federal-aid highway program is a collection of formula and non-formula grant programs.[11] The program provides funding to state DOTs for projects that include preserving, constructing, and improving about 1 million of the nation’s 4 million miles of roads, most of which are locally or state owned and operated. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act authorized an annual average of about $54.6 billion in funding for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 for the federal-aid highway formula programs.[12]

FHWA’s responsibilities for the federal-aid highway program include monitoring the efficient and effective use of funding and providing oversight and technical assistance. When using funds from the program, states must adhere to applicable federal and state statutes and regulations. FHWA has broad authority to take action to ensure state compliance with the terms and conditions of receiving the grants, including applicable federal laws and statutes.

FHWA uses a decentralized organizational structure to administer the federal-aid highway program. This means that FHWA delegates oversight and administration of the program to its division offices. As of June 2025, there were 52 division offices, one located in each of the 50 states, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. These offices provide technical expertise to state DOTs and authorize them to carry out individual federal-aid highway projects. State DOTs are responsible for developing, implementing, and overseeing these projects, including construction.

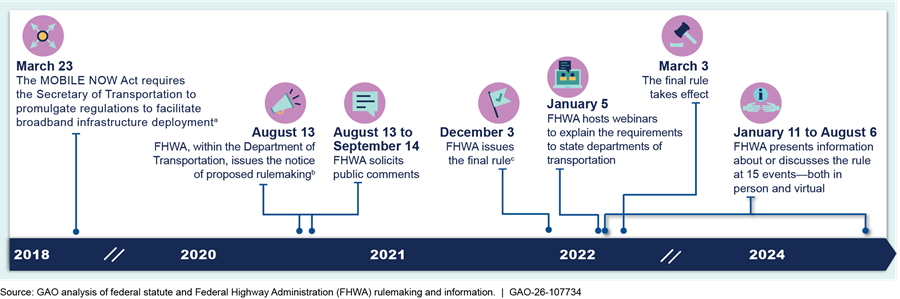

FHWA’s “Dig Once” Rule

In August 2020, FHWA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking in response to the 2018 statutory requirement for DOT to issue regulations related to broadband infrastructure deployment.[13] (See fig. 2.) The proposed rule sought to amend FHWA’s regulations governing the accommodation of utilities in the ROWs of federal-aid and direct federal highway projects to facilitate the installation of broadband infrastructure.

aSee Pub. L. 115‑141, div. P, tit. VI,

§ 607,132 Stat. 1097, 1104 (2018) (codified at 47 U.S.C.

§ 1504).

bSee FHWA, Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 85 Fed. Reg. 49328

(proposed Aug. 13, 2020).

cSee FHWA, Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 86 Fed. Reg. 68553

(Dec. 3, 2021).

FHWA received 29 submissions commenting on the proposed rule. A few commenters expressed support, noting potential benefits including financial savings, safety improvements due to reduced highway construction, and increased access to and reliability of broadband networks. By contrast, some commenters expressed concerns including the cost of implementing the proposed rule and potential redundancy with states’ existing policies and processes.

FHWA’s final “dig once” rule, which took effect on March 3, 2022, established new regulatory requirements for state DOTs that receive federal-aid highway program funding.[14] Generally, the regulations require state DOTs to

1. identify a broadband utility coordinator;

2. establish a registration process for broadband infrastructure entities seeking to participate in certain broadband infrastructure facilitation efforts;[15]

3. establish a process to, at minimum, electronically notify those entities on an annual basis of the state transportation improvement program (STIP);[16] and

4. coordinate initiatives with other statewide telecommunication and broadband plans, as well as with state and local transportation and land use plans.

The final rule gives states discretion as to how they meet these requirements by its effective date. In the final rule, FHWA recognized that each state has individual laws governing utilities and some states may have already implemented some of the requirements. FHWA also stated that states still have the autonomy to implement or amend their laws to meet the requirements of the rule in a manner that fits with their existing practices and meets their needs and objectives. Indeed, some states and local governments had some form of “dig once” statutes, regulations, or policies prior to FHWA’s rule, according to various analyses by a state DOT and industry organizations.[17] The 2018 statute requiring the rulemaking and FHWA’s implementing regulations also state that they do not require states to install or allow the installation of broadband infrastructure in a highway’s ROW.

Though FHWA has the general authority to monitor states’ compliance with and implementation of the requirements, the MOBILE NOW Act prohibits FHWA from withholding or reserving funds or project approval if it finds a state noncompliant. According to FHWA officials, FHWA takes a risk-based approach to overseeing the federal-aid highway program, consistent with federal requirements for it to monitor the effective and efficient use of federal-aid highway and certain other funds.[18] Further, FHWA officials said the general requirements established by the “dig once” rule do not impact the effective and efficient use of such funds. Thus, the officials said states’ noncompliance with those particular regulations presents a low risk to the federal-aid highway program, because installing broadband generally does not a) impact the operation of adjacent highways or b) affect the cost of federal-aid highway projects when carried out separately. Because of this low risk, FHWA does not track states’ compliance with those regulations.

To assist states in understanding and implementing the rule, FHWA provided them with information about the rule’s requirements and with compliance assistance upon request.[19] As shown in figure 2 above, FHWA conducted several presentations to inform states of its broadband infrastructure deployment requirements after it finalized the rule in December 2021. In addition, FHWA officials said they participated in a federal interagency broadband working group every 2 weeks from March 2017 through January 2025. The officials said they informed the group of the final rule and of challenges to broadband deployment in state ROWs.

Most States Reported Their DOT Employs a Coordinator to Facilitate Broadband Deployment

Most survey respondents reported their state DOT had identified a state broadband utility coordinator. Respondents also reported that coordinators’ areas of responsibility varied.

Employment and Tenure

Forty-six of the 52 survey respondents reported their state employed a broadband utility coordinator.[20] Of these, three indicated the coordinator was serving in an interim capacity. Among the six respondents that did not report having a broadband utility coordinator, one indicated the coordinator had recently left the position, and another two reported that although they did not have a coordinator, their states had implemented FHWA’s registration and notification requirements. Another reported their state had neither designated a coordinator nor established registration or notification processes.[21]

For most respondents, their state DOT employed the coordinators. However, five reported their coordinators worked in the state broadband office, which is permitted under FHWA’s regulations. According to NTIA officials, a benefit of having coordinators within state DOTs is that they may be able to better support and expedite broadband permitting and enforcement of FHWA rules. However, the officials said it is critical for the person in that role to have a close working relationship with the state broadband office.

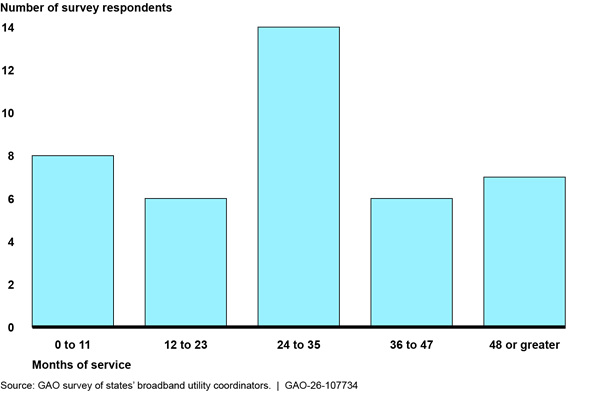

In its final rule, FHWA stated it expected coordinator duties to vary across states but would require less than a full-time commitment. Most respondents reported their state had one coordinator, but seven respondents reported their state employed multiple broadband utility coordinators. Of these seven, four indicated their coordinators shared the position responsibilities. At the time of our survey, there were coordinators who had served from 5 weeks to 19 years; the most frequently reported length of service was 24 to 35 months (see fig. 3).

Note: Length of service is rounded to the nearest month. “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on 41 states that had a coordinator and indicated how long their coordinator had served in the role. See question 6 in appendix I.

Coordinator Responsibilities

Survey respondents reported their state broadband utility coordinator’s responsibilities varied, as shown in figure 4. As previously noted, FHWA’s regulations require state DOTs to identify—in consultation with appropriate state agencies—a broadband utility coordinator to facilitate certain ROW efforts in their state. The regulations do not set forth specific responsibilities of the coordinator in facilitating those efforts but provide that coordinators may carry out other responsibilities within the state DOT or other state agency.[22]

Note: “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on responses from 44 respondents who reported they are the broadband utility coordinator in survey questions 1 and 2. The figure does not include non-responses, or respondents who reported they are not the coordinator. See question 7 in appendix I.

When asked about the responsibilities the coordinator oversees, half of the respondents reported the role included coordination with (1) providers and other entities; (2) government agencies; and (3) Tribal Nations. For example, officials from two states we interviewed said that as coordinators, they routinely communicate with providers. By contrast, a coordinator in another state said they work closely with the state broadband office, which has more direct communications with providers. We discuss these types of coordination efforts in more detail later in this report.

Moreover, while broadband utility coordinators are not generally responsible for receiving or applying for federal funding, they may assist with such efforts. When asked whether their state, either directly or by assisting providers and other entities, had applied for or received funding through a federal program that may support broadband infrastructure deployment in a federal-aid highway right-of-way, 14 respondents reported their state had done so. One state official we interviewed described working with providers to apply for federal funding.

Stakeholders and state officials we interviewed offered additional perspectives on coordinator responsibilities. For example, one stakeholder told us states often layer the coordinator responsibilities onto an engineer’s existing duties. By contrast, officials in two states we spoke with said the state DOT specifically hired them to fulfill coordinator responsibilities.

Many States Reported Establishing Registration and Notification Processes, but Some Cited Implementation Challenges

Over half (29 of 52) of survey respondents reported their state had fully established both the registration and notification processes required under FHWA’s regulations. Regarding each requirement, 31 respondents reported having established a registration process for providers and other entities interested in “dig once” opportunities, while 36 reported having established an electronic notification process to annually inform registered entities of the STIP and to provide additional notifications (see fig. 5).[23] Some states reported they were currently establishing or had not yet established the processes at the time of our survey, with a few citing challenges implementing the processes.[24]

Note: “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on closed-ended responses to two survey questions: (1) “Which best describes your state’s status in establishing a registration process for providers and other entities in your state’s broadband infrastructure ROW facilitation efforts?” and (2) “Which best describes your state’s status in establishing a process to electronically notify providers and other entities of your state’s transportation improvement program (STIP)?” See questions 8 and 16 in appendix I.

Registration Processes

Many respondents reported their state had fully established a registration process for providers and other entities. Of the 31 respondents who reported their state had fully established a registration process, four reported having a preexisting process while 18 indicated their state did not have a process in place before FHWA’s final rule went into effect.[25] When asked to describe any modifications made to the preexisting process, one respondent described how their state incorporated a permit application for those that wish to install broadband in the ROW.

Among the 31 states with fully established processes, 19 reported registering more than 20 providers and other entities.[26] Eight reported registering between one and 10 providers and other entities, and two reported registering between 11 and 20 providers and other entities. The number of registered providers and other entities illustrates engagement with the registration process, but it does not provide insight into whether this level of participation facilitated broadband deployment.

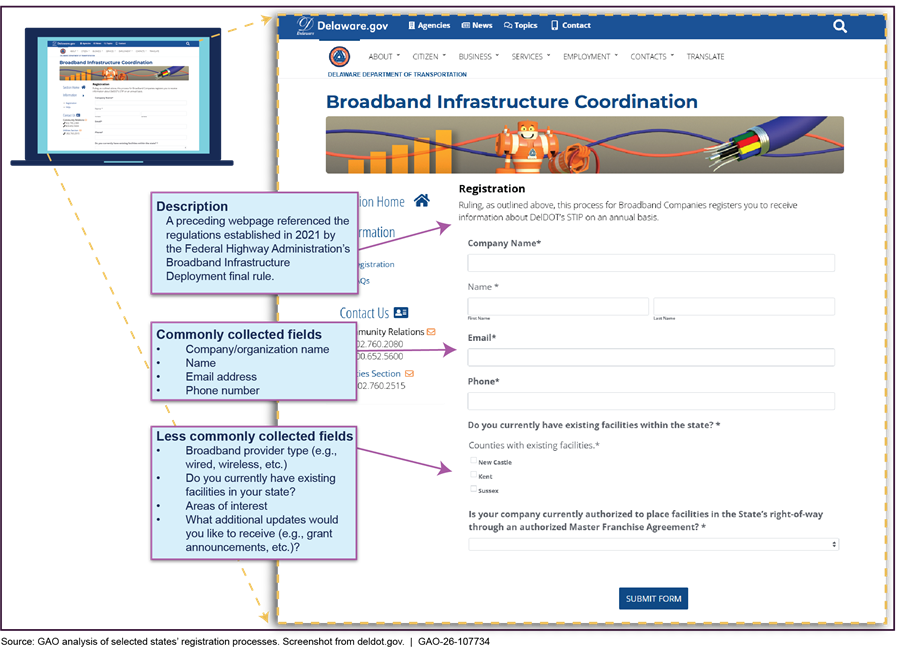

In reviewing states’ reported registration processes, we found states’ processes were similar but not uniform. In general, providers and other entities register either by completing an online form or by contacting the coordinator directly. The type and amount of information states requested through the process varied. However, the processes generally required providers and other entities to submit basic contact information (i.e., email address), as shown in figure 6. Also, we found states may request additional information, such as broadband provider type and confirmation of existing facilities. This additional information may be intended to help states better understand an entity’s operational presence, interests, needs, or preferences.

States generally use their respective state DOT websites for their registration process, according to survey responses. However, in a few states, another state agency managed the registration process and supported the notification process by sharing provider information with the state DOT. For example, one state official we interviewed said providers register through the state broadband office, which then shares the information with the state DOT coordinator. A few respondents from states without a registration process reported using alternative means to obtain provider contact information. For instance, officials in one state told us state statute and rules require internet providers to obtain a license to operate in the right-of-way, and the state DOT uses that information to coordinate with providers.

Notification Processes

Many respondents also reported that their state had fully established a notification process to inform providers and other entities of the state’s STIP. Specifically, 36 states reported having established such a process. Of these, 26 reported using email to inform and update providers and other entities about the STIP.[27] Some respondents also reported posting the STIP on their respective DOT websites, either in addition to or in place of email.

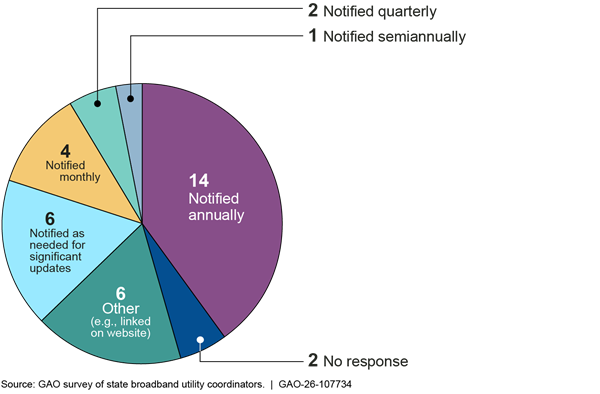

Fourteen of the 36 respondents from states with fully established notification processes indicated their state issued STIP notifications on an annual basis (see fig. 7). Seven other respondents reported more frequent notifications.

Note: “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on responses from 35 of 36 respondents who reported their state had fully established a process to electronically notify providers and other entities of the state’s transportation improvement program. The question was not applicable to one respondent. See questions 16 and 19 in appendix I.

In addition to sharing information about the STIP, 14 respondents reported their state used the notification process for other purposes including announcing meetings or events, sharing grant opportunities, providing active permit reports, and distributing general resources.

In the nine states in which respondents reported not having fully established notification processes, officials may be communicating the STIP information to providers by other means. For example, one state DOT official told us that in lieu of email notifications, they meet in person with providers several times a year to discuss the STIP and other matters. Furthermore, states with notification processes may conduct additional outreach. For example, officials in one state said providers and other entities can participate in monthly status calls with the state broadband office for more regular updates.

Reported Challenges

Some respondents identified challenges with respect to implementing the required registration and notification processes.[28] For example, a stakeholder cited resource constraints, specifically the limited availability of experienced staff, as a barrier to implementation. For instance, when asked to describe ongoing efforts or challenges related to establishing a registration process, one respondent reported their state DOT did not have sufficient staff and had hired a consultant to help develop the state’s registration process. Similarly, one stakeholder said state broadband offices have experienced significant staff turnover.

In addition to staffing, a few respondents cited IT-related implementation challenges. For example, one respondent noted that software issues had prevented their state from fully automating its registration and notification process. Another respondent noted updates to their state DOT’s website had resulted in broken links to their registration form.

States Reported Coordinating Across Agencies to Facilitate Broadband Infrastructure Deployment

FHWA’s regulations require states to coordinate broadband initiatives with other state and local plans. In responding to questions related to these requirements, most (46 of 52) survey respondents reported coordinating broadly with federal, other state, and local agencies on broadband infrastructure deployment. More respondents reported coordinating with FHWA and their state broadband office than with other federal and state agencies.

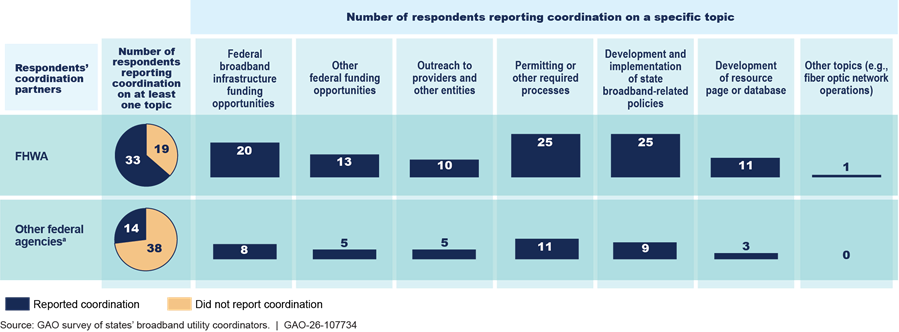

Coordination with Federal Agencies

Many respondents reported coordinating with FHWA, as shown in figure 8. The most frequently reported topics of coordination were development and implementation of state broadband-related policies and permitting or other required processes. Specifically, 25 of the 33 respondents who reported coordinating with FHWA about at least one topic also reported coordinating with FHWA on developing and implementing state broadband-related policies. For example, one respondent noted a FHWA division office reviewed their state’s draft procedures and provided recommendations for implementing FHWA’s final rule.

Note: “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on closed-ended responses to survey question 23 in appendix I: “In fulfilling the duties of coordinator, with which agencies have you coordinated on the following topics?”

aOf the states that reported coordinating with a federal agency other than the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), one or more reported coordinating with the (1) National Telecommunications and Information Administration; (2) U.S. Department of Agriculture; (3) Federal Communications Commission; or (4) National Economic Council.

Twenty-five respondents reported coordinating with FHWA on permitting or other required processes. One stakeholder we interviewed said state DOT officials sometimes perceived FHWA as not allowing broadband deployment in highway ROW, demonstrating why it is important for state officials to coordinate with FHWA to understand an FHWA official’s response to a project. For example, one state official said their stewardship and oversight agreement with FHWA did not allow them to deploy broadband infrastructure on interstate highway ROWs, but FHWA officials stated this may be a matter of state law.[29] FHWA officials added that the agency does not have any regulations, policies, or guidance that prohibits the installation of broadband infrastructure on an interstate highway ROW, so long as it does not impact the safety and operations of the highway.

Few survey respondents and state officials we interviewed reported coordinating with other federal agencies. However, 11 of the 14 respondents who did so reported coordinating with these other agencies on permitting and other required processes. For example, officials from one state mentioned coordinating permits for highway ROW with the Bureau of Land Management. Also, eight respondents reported coordinating with other federal agencies about funding opportunities. State officials mentioned that several federal funding sources have helped support broadband infrastructure deployment in highway ROW.[30]

A few respondents, stakeholders, and officials we interviewed identified areas for additional federal support or coordination, primarily from FHWA. These respondents suggested it would help to have (1) increased communication about the final rule and examples of successful state implementation; and (2) access to other coordinators’ contact information and assistance in organizing meetings with other coordinators. Three respondents noted they would like assistance facilitating permitting with federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and FHWA. Officials from two state DOTs, along with a few providers and one stakeholder, said clarification on permitting policies and regulations would also be helpful.

According to FHWA officials, FHWA’s division offices typically worked with states to implement the requirements of its rule and provide assistance upon request. For example, according to officials, one FHWA division office provided support to a state’s DOT when it asked for guidance on applying utility accommodation policies to broadband, given the state does not regulate broadband as a utility.

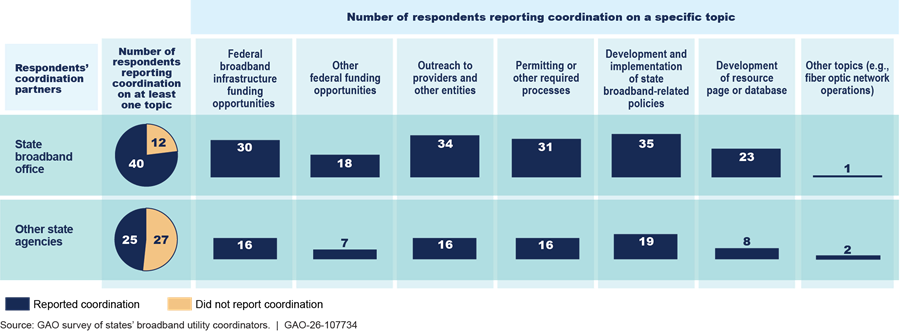

Coordination with State and Local Agencies

Many respondents and state officials we interviewed reported coordinating with state and local agencies on a range of topics, although more respondents reported coordination with the state broadband offices than other state agencies. Specifically, 40 respondents reported coordinating with their state broadband offices (see fig. 9). Furthermore, all the state officials we spoke with said their state DOT and state broadband office worked closely together. For example, one broadband office moved into the state DOT in 2025.

Note: “States” refers to the 50 states, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. This figure is based on closed-ended responses to survey question 23 in appendix I: “In fulfilling the duties of coordinator, with which agencies have you coordinated on the following topics?”

Respondents’ most frequently reported topics of coordination with state broadband offices were development and implementation of state broadband-related policies (35 respondents) and outreach to providers and other entities (34 respondents). For example, one state DOT official said they attend monthly meetings with the statewide broadband action team and 14 local broadband “action teams” within their state. Through these meetings, the official has discussed the state DOT’s long-range planning efforts. According to NTIA officials, after joint webinars held by FHWA and NTIA to inform states of FHWA’s “dig once” requirements, officials in the state broadband offices generally know the state broadband utility coordinators. However, they also said sustaining relationships between the broadband offices and utility coordinators will be needed to maintain coordination through staff changes.

A few respondents and state officials we interviewed reported coordinating with local officials. For example, one respondent indicated they met monthly with a county utility committee. As coordinator, the respondent shared the state DOT’s plans for an interchange project, and the utility committee shared updates on its project to deploy broadband on utility poles. In addition, one stakeholder we interviewed said some states, particularly in the Southwest, have been coordinating broadband deployment plans for a long time, not only within states but across groups of states.

A few stakeholders we interviewed emphasized the importance of coordination to achieve meaningful broadband deployment. One stakeholder said interagency coordination should be a priority, particularly when projects span multiple jurisdictions. For example, one provider’s representative said years before FHWA’s rule, the provider, city, and state DOT worked together on broadband deployment for a dangerous stretch of highway that needed traffic cameras and monitoring. The city and state DOT coordinated to ensure the provider’s access to the state DOT’s highway ROW. As a result, the provider was able to connect to a larger city, resulting in swift improvements to the company’s ability to provide cost-effective service to nearby rural areas.

States and Stakeholders Indicated the Effects of FHWA’s “Dig Once” Requirements Are Not Well Known

In general, survey respondents and stakeholders we interviewed indicated that the effects of FHWA’s “dig once” rule on broadband deployment were not well known at the time of our survey. This may, in part, reflect external factors that influence how effectively states can leverage the rule. Still, respondents expressed optimism about the rule’s potential to facilitate deployment and reported specific benefits.

Effects on Broadband Infrastructure Deployment

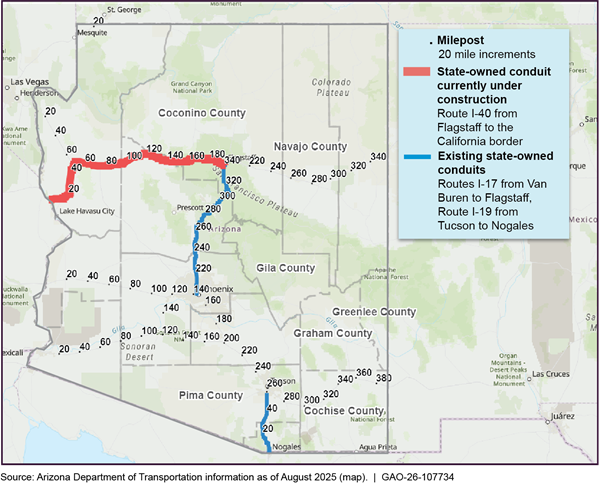

Fourteen respondents reported that their state used metrics to track deployment in the federal-aid highway ROW. This information may help inform a broader understanding of deployment efforts since the rule took effect. For example, Arizona DOT manages a map showing state-owned fiber optic conduit routes. As of August 2025, this map highlighted existing and planned installations along several federal-aid highways, including I-17 between Phoenix and Flagstaff (see fig. 10). Arizona DOT intends to lease this conduit to providers seeking to expand internet access to the state’s homes and businesses, and to use these routes to deploy intelligent transportation system technologies, such as message boards, traffic cameras, and weather stations.

Additionally, some survey respondents provided information on the number of broadband infrastructure deployment projects initiated or completed in the federal-aid highway ROW since the rule took effect. Specifically, 16 respondents reported their state had initiated or completed projects. For example, one survey respondent cited a planned project that is a 530-mile, open-access fiber optic network intended to expand connectivity across the state. The state plans to install portions of the network in the federal-aid highway ROW.

Despite this, respondents, along with state officials and stakeholders we interviewed, generally could not attribute specific projects or outcomes directly to FHWA’s rule. They suggested this was due, in part, to factors unrelated to the rule. For example, a few respondents indicated that their state had already implemented a “dig once” policy before FHWA’s rule. State officials, stakeholders, and a provider we interviewed also told us it was too early to reflect on the rule’s effects because some federal broadband funding programs that could benefit from the rule’s implementation had not yet awarded funds. For example, one stakeholder and officials from two states suggested it was too soon to evaluate projects that might receive funding under NTIA’s Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program. As of September 2025, NTIA had not yet fully approved states’ proposals, according to NTIA’s dashboard.[31] NTIA officials agreed that increased broadband funding was likely to increase instances of states needing to coordinate broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway ROW.

FHWA officials told us they decided not to systematically track states’ implementation of the rule’s requirements or projects in which states include broadband infrastructure deployment in the ROW. As previously discussed, FHWA determined the risk to federal-aid highway program funds to be low. FHWA officials also said that state DOTs are responsible for managing highway ROWs.

Coordination Benefits

As mentioned above, the specific effects of FHWA’s rule on broadband deployment are not well known, although respondents did cite general reasons for optimism about its potential effects. A few respondents indicated that the rule helped establish or reinforce a framework to support broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway ROW. For example, one respondent stated the rule resulted in their state adding broadband providers to its public utility list. As a result, the state is now able to approve broadband deployment in the ROW. Another respondent stated that it was helpful to see FHWA formally recognize the value of coordination on highway and broadband projects. The respondent added that the rule gave other states confidence to adopt practices that their state had implemented for years.

|

Utah Realizes Benefits from Coordination of Broadband Infrastructure Deployment Along Highway Rights-of-Way The Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) has been facilitating broadband infrastructure deployment in highway rights-of-way (ROW) since preparations for the 2002 Winter Olympics. UDOT officials said that the department grants internet service providers access along designated routes, facilitating deployment of middle-mile broadband across the state. According to state officials, Utah’s statutes, policies, and processes allow providers to use a highway ROW or UDOT’s existing conduit in that ROW in exchange for cash or in-kind compensation (i.e., a trade). In addition, UDOT officials said they incorporate broadband infrastructure deployment into Utah’s state transportation improvement program. As a result, UDOT officials said they have connected 97 percent of traffic signals in the state to UDOT’s fiber optic network, along with Intelligent Transportation Systems devices (e.g., sensors). UDOT officials and provider representatives said these efforts have improved traffic safety. For example, the officials said prior to a 10-mile-long “dig once” project down the center of a highway in Logan Canyon, the scenic byway lacked all forms of communication—including 911 service. In addition, provider representatives said they have seen improvements in real-time information for travelers. Source: Utah Department of Transportation officials and documentation, and internet service providers. | GAO-26-107734 |

Survey respondents also reported that FHWA’s rule contributed to specific coordination benefits. When asked about any benefits their state had observed in implementing FHWA’s final rule, 11 of 39 respondents reported the rule had improved coordination. Five respondents cited improved coordination with their state broadband office, while six cited improved coordination with providers and other entities.

While respondents reported that coordination with providers had improved, they also acknowledged persistent challenges in engaging providers in state registration processes. In particular, one respondent noted that providers may be reluctant to share information on existing or planned network facilities. Four providers said state statutes, policies, and culture can influence their willingness to coordinate and share plans with state officials. One stakeholder said some state and local governments appear to treat providers as a source of revenue rather than as a partner. By contrast, a state official said broadband infrastructure installed with transportation funding becomes a highway asset, and thus a provider must pay fair market value to access it. Additionally, one stakeholder and one state official said that from the state DOT perspective, while state DOTs accommodate utilities in the ROW, they prioritize highway purposes.

A few respondents also indicated that successful industry collaboration depends on the alignment of several factors, such as the location of future projects and construction schedules. In addition, three providers said residents’ ability to pay for services can influence whether providers can afford to deploy broadband in a particular area. Furthermore, successful coordination does not always deliver deployment. One state official said DOTs try to do as much as possible, but resource limitations can make it difficult for state DOT staff to keep up with the volume of permit applications they receive.

A few respondents described ongoing outreach efforts to inform providers of the registration process and encourage their participation. For example, one respondent stated that their state DOT leveraged contact information from providers with existing permits in the federal-aid highway ROW and from their state’s utilities and transportation commission. The state DOT used this list to notify providers of the state’s registration process.

Moreover, a few respondents, state officials, provider representatives, and other stakeholders we interviewed cited the broader goals of “dig once” as reasons for optimism about the benefits of the rule. These benefits included reduced excavation and traffic disruptions, lower project costs, and greater broadband access. For example, one provider representative said deploying broadband in highway ROW reduces the need to cross private property, or property managed by the U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management, which can make the project more efficient.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOT for review and comment. DOT provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Sincerely,

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure

The questions we asked in our survey of state officials on the implementation of the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) broadband infrastructure deployment final rule and the aggregated responses to the closed-ended questions are shown below.[32] Our survey comprised closed- and open-ended questions. We do not provide results for the open-ended questions or other written survey responses. We sent surveys to broadband utility coordinators from all 50 states, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia.[33] In instances where a state had not designated a coordinator, we surveyed the state official responsible for facilitating broadband deployment in the federal-aid highway right-of-way (ROW). We received 52 responses, for a 100-percent response rate. Counts may not total 52 for some questions that were not applicable to some respondents based on responses or item nonresponse to earlier questions. The methodology we used to administer this survey is described earlier in this report.

Q1. Are you a broadband utility coordinator in your state?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

41 |

|

No |

9 |

|

No answer/not checked |

2 |

Q2. Are you currently assuming utility coordinator duties on an interim basis?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

3 |

|

No |

6 |

|

No answer/not checked |

2 |

Q2a. If you are neither a permanent nor interim utility coordinator, please explain your role in relation to FHWA’s final rule.

(Written responses not included.)

Q3. How many broadband utility coordinators does your state have? (Please enter a numerical value)

(Written responses not included.)

Q4. How are duties divided among utility coordinators (e.g., by geographic area, area of expertise, or other factor(s))?

(Written responses not included.)

Q5. As utility coordinator, is your contact information made publicly available online?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes, my professional contact information as the utility coordinator is made publicly available online (please provide web address) |

21 |

|

Yes, my general contact information is made publicly available online (please provide web address) |

16 |

|

No |

5 |

|

No answer/not checked |

2 |

Q6. Approximately, how long have you served as utility coordinator or assumed utility coordinator responsibilities for your state? Please specify whether your answer is in years, months, and/or weeks.

(Written responses not included.)

Q7. In your role as utility coordinator, what responsibilities do you oversee?

(Written responses not included.)

Q8. Which best describes your state’s status in establishing a registration process for providers and other entities in your state’s broadband infrastructure ROW facilitation efforts?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Not yet established |

5 |

|

Currently establishing |

13 |

|

Fully established |

31 |

|

No answer/not checked |

3 |

Q9. Please describe any ongoing efforts or challenges related to your state’s establishment of a registration process for providers and other entities partnering on ROW facilitation efforts.

(Written responses not included.)

Q10. Which of the following methods, if any, does your state use to inform providers and other entities about the registration process concerning ROW facilitation efforts and solicit their participation?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

|

33 |

|

State agency press releases |

13 |

|

Website notifications |

24 |

|

Conferences or events |

25 |

|

Engagement with professional and industry groups |

28 |

|

Other (please specify): |

11 |

|

No answer/not checked |

4 |

Q11. Does your state use the following to manage registration of providers and other entities for ROW facilitation efforts?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Email List |

32 |

|

Custom-built electronic registration process (please specify) |

20 |

|

Customer relationship management or data collection programs (e.g., Salesforce, Google Forms/Sheets, etc.) |

9 |

|

Other (please specify): |

10 |

|

No answer/not checked |

6 |

Q12. Please enter the web address link to your state’s registration process for providers and other entities seeking to partner on ROW facilitation efforts. Please write “Not available” if you could not include a link or do not have a link to share.

(Written responses not included.)

Q13. Approximately how many providers and other entities are currently registered with your state?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

None |

0 |

|

1-10 |

11 |

|

11-20 |

3 |

|

More than 20 |

23 |

|

Registration process is not fully established |

7 |

|

No answer/not checked |

3 |

Q14. Prior to March 2022, the month in which FHWA’s December 2021 final rule went into effect, did your state have a registration process to coordinate broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

8 |

|

No |

23 |

|

Lack sufficient information to respond |

13 |

|

No answer/not checked |

3 |

Q15. Did your state modify any pre-existing processes to meet the general requirements of FHWA’s final rule?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

3 |

|

No |

5 |

|

Lack sufficient information to respond |

0 |

|

No answer/not checked |

44 |

Q15a. Please describe modifications to the pre-existing processes.

(Written responses not included.)

Q16. Which best describes your state’s status in establishing a process to electronically notify providers and other entities of your state’s transportation improvement program (STIP)?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Not yet established |

8 |

|

Currently establishing |

5 |

|

Fully established |

36 |

|

No answer/not checked |

3 |

Q17. Please describe any ongoing efforts or challenges related to your state’s establishment of an electronic STIP notification process.

(Written responses not included.)

Q18. Which processes does your state use to share STIP notifications with providers and other entities?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Email notifications |

29 |

|

Online portal or dashboard notifications (Please specify): |

12 |

|

State agency website notices |

21 |

|

Other (Please specify): |

6 |

|

No answer/not checked |

5 |

Q19. About how often does your state issue notifications to providers and other entities about the STIP?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Annually |

18 |

|

Semi-annually |

1 |

|

Quarterly |

2 |

|

Monthly |

5 |

|

As needed for significant updates |

7 |

|

Other (please specify): |

8 |

|

Not applicable |

1 |

|

No answer/not checked |

5 |

Q20. Has your state provided additional notifications to providers and other entities beyond notification of the STIP?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes (Please describe the nature of additional notifications) |

14 |

|

No |

17 |

|

Not applicable |

11 |

|

No answer/not checked |

5 |

Q21. How frequently does your state use the notification process to communicate additional information beyond the STIP with providers and other entities?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Annually |

2 |

|

Semi-annually |

1 |

|

Quarterly |

2 |

|

Monthly |

2 |

|

Other (please specify): |

5 |

|

Not applicable |

4 |

|

No answer/not checked |

4 |

Q22. In fulfilling the duties of utility coordinator, have you coordinated with the following federal agencies regarding broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) |

6 |

|

National Economic Council (NEC) |

1 |

|

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) |

13 |

|

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) |

6 |

|

U.S. Department of Transportation, Including the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) |

32 |

|

U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) |

6 |

|

Other (please specify): |

8 |

|

No answer/not checked |

5 |

Q23. In fulfilling the duties of coordinator, with which agencies have you coordinated on the following topics?

|

Responses |

Number of “yes” responses |

|

|||

|

FHWA |

Other federal agency |

Your state broadband office |

Other state agency |

|

|

|

Federal broadband infrastructure funding opportunities |

20 |

8 |

30 |

16 |

|

|

Other federal funding opportunities |

13 |

5 |

18 |

7 |

|

|

Outreach to providers and other entities |

10 |

5 |

34 |

16 |

|

|

Permitting or other required processes |

25 |

11 |

31 |

16 |

|

|

Development and implementation of state broadband-related policies |

25 |

9 |

35 |

19 |

|

|

Development of resource page or database |

11 |

3 |

23 |

8 |

|

|

Other (Please specify) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Note: Respondents were provided the option to select “yes,” “no,” or decline to provide a response. The table presents the count of “yes” responses.

Q24. In fulfilling the duties of utility coordinator, do you coordinate with your state or local agencies on broadband infrastructure deployment efforts?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes (Please specify which state or local agencies) |

37 |

|

No |

8 |

|

No answer/not checked |

7 |

Q25. What, if any, coordination have you had with your state’s broadband office or designated entity responsible for managing federal broadband initiatives or funding, such as grants received through the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program?

(Written responses not included.)

Q26. Prior to March 2022, the month in which FHWA’s December 2021 final rule went into effect, did your state have a formal process for coordinating initiatives related to broadband infrastructure deployment with other statewide and local plans (e.g., telecommunication, transportation, and land use/zoning plans)?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

11 |

|

No |

19 |

|

Lack sufficient information to respond |

18 |

|

No answer/not checked |

4 |

Q26a. Please describe your state’s process for coordinating initiatives.

(Written responses not included.)

Q27. Please share an example(s) of a project(s), if any, where your state has coordinated initiatives related to broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW with other state and local plans (e.g., telecommunication, transportation, and land use/zoning plans).

(Written responses not included.)

Q28. Since March 2022, the month in which FHWA’s December 2021 final rule went into effect, has your state, either directly or by assisting providers and other entities, applied for and received funding through federal programs to support broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

14 |

|

No |

32 |

|

No answer/not checked |

6 |

Q29. Since March 2022, the month in which FHWA’s December 2021 final rule went into effect, has your state initiated or completed any broadband infrastructure deployment projects in the federal-aid highway project ROW?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

16 |

|

No |

12 |

|

Lack sufficient information to respond |

21 |

|

No answer/not checked |

3 |

Q29a. Please share an example of broadband infrastructure deployment projects occurring within the ROW of federal-aid highways.

(Written responses not included.)

Q30. Does your state use metrics to track broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW, such as the number of projects, miles of infrastructure installed, or people served?

|

Response |

Number of responses |

|

Yes |

14 |

|

No |

12 |

|

Lack sufficient information to respond |

22 |

|

No answer/not checked |

4 |

Q30a. If the metrics to track broadband infrastructure deployment in the federal-aid highway project ROW are publicly available, where can they be accessed?

(Written responses not included.)

Q31. What benefits, if any, has your state observed in implementing FHWA’s final rule?

(Written responses not included.)

Q32. What recommended practices, if any, have emerged as a result of implementing FHWA’s final rule or, if applicable, from the adoption of “dig once” policies in your state?

(Written responses not included.)

Q33. What challenges, if any, has your state experienced in implementing FHWA’s final rule?

(Written responses not included.)

Q34. What assistance, if any, have FHWA or its division offices provided to your state in implementing the final rule?

(Written responses not included.)

Q35. What additional support, if any, could federal partners provide to help your state implement FHWA’s final rule?

(Written responses not included.)

Please provide the following information in case we need to contact you to clarify a response.

Name:

Title:

Agency:

Office or Division:

Telephone:

Email Address:

(Written responses not included.)

GAO Contact

Andrew Von Ah, vonaha@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Nalylee Padilla (Assistant Director), Jaclyn Mullen (Analyst in Charge), Melanie R.M. Diemel, Félix Muñiz Jr., M-Cat Overcash, Kelly Rubin, Paras Sharma, Michelle Weathers, and Alicia Wilson made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Generally, “middle mile” refers to the portion of the internet that connects the last mile (internet connections to homes or businesses) with the backbone (transmission lines linking global internet networks). Providers use various types of technologies for the different components of the internet. In middle-mile networks, fiber optic cable is the most common technology deployed.

[2]GAO, Planning and Flexibility Are Key to Effectively Deploying Broadband Conduit Through Federal Highway Projects, GAO‑12‑687R (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2012). For information on recent federal funding to support deployment of middle-mile networks, see GAO, Broadband Infrastructure: Middle-Mile Grant Program Lacked Timely Performance Goals and Targeted Measures, GAO‑24‑106131 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 19, 2023).

[3]See, e.g., Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Pub. L. No. 117-58, 135 Stat. 429, 1351, 1353-1355, 1382 (2021); American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9901, 135 Stat. 4, 223-236 (2021); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. N, tit. IX, § 905(b), 134 Stat. 1182, 2138 (2020); CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, div. B, tit. I, § 11004, 134 Stat. 281, 510 (2020).

[5]For the purposes of this federal statute, “state” refers to any of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. See MOBILE NOW Act, Pub. L. 115‑141, div. P, tit. VI, § 607,132 Stat. 1097, 1104 (2018) (codified at 47 U.S.C. § 1504). We refer to all transportation agencies in states as state departments of transportation (state DOTs). In total, there are 52 state DOTs.

[6]See FHWA, Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 86 Fed. Reg. 68553 (Dec. 3, 2021).

[7]We sent surveys to broadband utility coordinators from all 50 states, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. In instances where a state had yet to designate a coordinator, we surveyed the state official responsible for facilitating broadband deployment in federal-aid highway ROWs.

[8]Two analysts independently reviewed and categorized responses, coding recurrent themes and applying professional judgment as appropriate. If the analysts disagreed about the categorization, a third analyst reviewed the response.

[9]The 10 states we selected were: Arizona, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, New York, Oregon, Puerto Rico, Tennessee, and Texas.

[10]From industry, we interviewed representatives from the Fiber Broadband Association and the Wireless Infrastructure Association. We also interviewed representatives from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and the National Governors’ Association.

[11]For the purposes of this report, these grant programs are those through which funding is provided under 23 U.S.C. Chapter 1 and administered by FHWA. Under a formula grant program, DOT distributes funding to all eligible recipients using a statutory formula.

[12]See Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 11101(a)(1), 135 Stat. 429, 443 (2021).

[13]See FHWA, Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 85 Fed. Reg. 49328 (proposed Aug. 13, 2020). For more information on DOT’s rulemaking process, see U.S. Department of Transportation Rulemaking Handbook (May 2022) and DOT Order 2100.6B, Policies and Procedures for Rulemakings (Mar. 10, 2025).

[14]See Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 86 Fed. Reg. 68553 (Dec. 3, 2021). FHWA’s regulations containing these requirements are located at 23 C.F.R. Part 645, Subpart C.

[15]For the purposes of this report, we refer to broadband infrastructure entities as “providers and other entities.”

[16]A STIP is a statewide prioritized list of transportation projects covering a period of at least 4 years and is required for such projects to be eligible for certain funding, including FHWA’s federal-aid highway program funding.

[17]See, for example, Fiber Optic Sensing Association, Dig Once Policy: 16 State Models (July 2020). See also, Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, Dig Once: How Federal, State, and Local Governments Can Reduce the Cost of Broadband Deployment (Vanderbilt University, Dec. 2025), https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-URL/wp-content/uploads/sites/412/2025/12/12003228/Dig-Once.pdf.

[18]See 23 U.S.C. § 106(g).

[19]Compliance assistance is a tool to ensure regulated entities understand regulatory requirements and how to comply by providing guidance and other assistance. For more information on types of regulatory compliance, see GAO, Federal Regulations: Key Considerations for Agency Design and Enforcement Decisions, GAO‑18‑22 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 19, 2017).

[20]Forty-four respondents reported that they had a broadband utility coordinator. However, for the purposes of this report, we classified two additional states as having identified a coordinator based on information provided in those respondents’ responses to our open-ended survey questions.

[21]Two respondents did not respond to our questions about whether their state had identified a coordinator.

[22]See 23 C.F.R. § 645.307(a)(1).

[23]Seven respondents reported their state had fully established a notification process but had not yet fully established a registration process. Four of these respondents indicated their state DOT provided notification by making the STIP publicly available online. Of the five respondents who reported their state was currently establishing a registration process, two noted their state was developing registration web pages, with one of these two noting the state needed to conduct outreach to entities about the process.

[24]In describing their state’s status in establishing these processes, respondents were also asked to identify any challenges or ongoing efforts. A few respondents cited specific challenges and ongoing efforts, as discussed later in the report.

[25]The remaining nine respondents indicated they lacked sufficient information to say whether their state had a registration process in place prior to FHWA’s rule.

[26]The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) broadband data collection is the primary federal data source for the total number of internet service providers operating in the U.S. From this data, FCC reported over 2,100 fixed broadband providers offered services as of December 2023. See FCC, 2024 Communications Marketplace Report (Washington, D.C.: December 2024). Also, according to data from FCC’s National Broadband Map, over 3,300 internet service providers reported providing either fixed or mobile broadband to locations across the U.S as of December 2024.

[27]As previously mentioned, a STIP is a statewide prioritized list of transportation projects covering a period of at least 4 years and is required for such projects to be eligible for certain funding, including FHWA’s federal-aid highway program funding.

[28]Respondents also identified challenges related to provider participation in state registration processes, which we discuss later in the report.

[29]As previously mentioned, states must adhere to applicable federal and state statutes and regulations when using federal-aid highway program funds.

[30]For example, officials from one state praised the flexibility of the Department of Treasury’s Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund. By contrast, one stakeholder noted that requirements that must be met to federally fund eligible broadband infrastructure projects can limit some “dig once” and project bundling efforts. In addition, eligible projects might not always explicitly include broadband infrastructure deployment that is specifically along federal-aid highway ROWs.

[31]In June 2025, NTIA issued a notice that modified and replaced certain requirements contained in its 2022 notice of funding opportunity for the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program. The notice in part rescinded NTIA’s final proposal approvals that occurred prior to the notice’s issuance. Entities eligible for the program’s funding must comply with the notice to gain approval of their final proposals. See NTIA, Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program: BEAD Restructuring Policy Notice (June 6, 2025). In December 2025, we issued a legal decision finding that this notice was a rule for the purposes of the Congressional Review Act, because it is an agency statement of future effect, imposes new BEAD Program requirements, and none of the act’s exceptions applied. See GAO, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration—Applicability of the Congressional Review Act to Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program Restructuring Policy Notice, B-337604 (Dec. 16, 2025).

[32]See FHWA, Broadband Infrastructure Deployment, 86 Fed. Reg. 68553 (Dec. 3, 2021).

[33]We used the term “state” in our survey to refer to any of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, as that is how the term is defined for the purposes of FHWA’s broadband infrastructure deployment final rule.