STREET DRUG ANALYSIS

Factors Affecting the Detection and Identification of Emerging Substances

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Karen L. Howard at HowardK@gao.gov or Triana McNeil at McNeilT@gao.gov

What GAO Found

Agencies at the federal, state, and local levels have facilities capable of analyzing emerging street drugs—psychoactive substances newly circulating in the drug market. For example, the Drug Enforcement Administration and U.S. Customs and Border Protection have forensic laboratories that can analyze seized drugs and identify emerging substances. Current laboratory-based technologies can detect and identify emerging street drugs when appropriate methods (protocols) and reference standards are available. Portable technologies can detect drugs at the point of seizure but face accuracy challenges due, in part, to user error. Technology manufacturers told GAO they are developing more lay-friendly user interfaces and operational methods.

From fiscal year 2019 through 2024, the Departments of Justice and Health and Human Services awarded a combined total of about $12.5 million in grants for the development of new methods and technologies for analyzing emerging street drugs. New methods and technologies may make laboratory processes more consistent, among other enhancements. Method development can be done on faster timelines than technology development.

While new methods and technologies could enhance some capabilities, forensic scientists face key challenges with analyzing emerging street drugs, including:

· Lack of resources. Laboratories GAO spoke to consistently referenced insufficient staffing and time.

· Unstandardized reporting. According to stakeholders, varying reporting requirements at the state and local levels can lead to gaps in data.

· Limited information sharing. Law enforcement may not always share up-to-date information about emerging drugs with medical examiners and hospitals.

If these challenges could be addressed, laboratories could be in a better position to meet the nation’s needs for emerging drug analysis. However, GAO is not making recommendations to address these challenges because they are primarily faced by state and local laboratories.

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. is facing a public health crisis with the rapidly changing and increasingly complex landscape of emerging street drugs. Overdose deaths related to fentanyl mixed with veterinary tranquilizers, such as xylazine and medetomidine, have increased in recent years according to agency data. This mixture can be fatal because opioid overdose reversal medication does not affect these tranquilizers. The ability to rapidly identify new street drugs as they emerge could save lives.

The Testing, Rapid Analysis, and Narcotic Quality Research Act of 2023 (Pub. L. No. 118-23, 137 Stat. 125, 126-27, § 3) includes a provision for GAO to review the capabilities of the federal government and state and local agencies to detect, identify, and analyze new psychoactive substances, which GAO refers to as “emerging street drugs” in this report. This report addresses (1) methods and technologies that are available or in development for emerging street drug analysis at federal and selected state and local laboratories and in the field, (2) timelines for developing new methods and technologies for the identification of emerging street drugs, (3) federal grant programs funding the development of new methods and technologies, and (4) federal and selected state and local facilities that analyze emerging street drugs and the key challenges they face.

GAO interviewed officials and reviewed documents from 16 components of seven federal agencies that have ongoing efforts in drug analysis. GAO also visited or interviewed officials from 15 state and local laboratories from three different regions in the U.S. Further, GAO reviewed scientific literature and interviewed additional stakeholders, including technology manufacturers and grantees.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

DART-MS |

direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry |

|

DEA |

Drug Enforcement Administration |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FTIR |

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

GC-MS |

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

|

GUARDS |

Global Uniform Analysis and Reporting of Drug-related Substances |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

Joint INTREPID Lab |

Joint Intelligence National Threat Response El Paso Illicit Drug Laboratory |

|

LC-MS |

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

NMR |

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

|

NPS |

novel psychoactive substances |

|

ONDCP |

Office of National Drug Control Policy |

|

RaDAR |

Rapid Drug Analysis and Research |

|

SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act |

Substance Use–Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act |

|

TRANQ Research Act of 2023 |

Testing, Rapid Analysis, and Narcotics Quality Research Act of 2023 |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 3, 2026

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Brian Babin

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The U.S. is facing a public health crisis with the rapidly changing and increasingly complex landscape of emerging street drugs.[1] The ability of officials at federal, state, and local agencies to quickly identify new substances as they emerge could save lives. In recognition of the significant loss of life and harmful effects resulting from drug misuse,[2] we added national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse to our High-Risk List in 2021.[3] From 2021 to 2023, the number of drug overdose deaths in the U.S. exceeded 100,000 per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Though overall overdose deaths have declined recently, the CDC estimated in September 2025 that the predicted provisional number of drug overdose deaths was more than 76,000 for the 12-month period ending in April 2025.[4]

Drug identification is a race against time, as new trends in street drugs can emerge within the span of a year or less. In October 2020, the nonprofit Center for Forensic Science Research and Education first released a public alert about the appearance of xylazine—a veterinary tranquilizer—in the street drug market. Tranquilizer use can be dangerous as their effects are not reversed by naloxone, a medicine used for opioid overdose reversal, and xylazine use specifically can also result in skin wounds. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reported that xylazine-related overdose deaths rose sharply across the country between 2020 and 2021, mainly in mixtures with fentanyl as a street drug called “tranq.” On April 12, 2023, the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) officially designated fentanyl combined with xylazine as an emerging drug threat to the U.S.[5] This designation led to the creation of a national response plan, including work on xylazine testing, treatment, and supply reduction strategies.[6] But a form of medetomidine—another even more potent veterinary tranquilizer with the street name “dex” for dexmedetomidine—may be competing with or even replacing xylazine in street drugs, according to officials from one High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area and data collected by the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Rapid Drug Analysis and Research (RaDAR) program.[7] Some states and localities, predominantly in the eastern U.S., have reported increases in overdose deaths correlated with the presence of medetomidine in drugs since mid-2024.

Agencies at the federal, state, and local levels all have a role to play in the analysis of emerging street drugs. As will be discussed in more detail later, federal agencies have different drug analysis jurisdictions, and officials told us that agencies collaborate when those roles overlap. For example, DEA analyzes seized drugs throughout the U.S. in its role as a federal law enforcement agency, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) analyzes suspected drugs with a border nexus including at and between the ports of entry along with international mail, and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service analyzes suspected drugs seized in domestic mail. State and local laboratories analyze emerging street drugs submitted from sources including their corresponding law enforcement agency and federal agencies through drug task forces, according to officials we spoke to.

The Testing, Rapid Analysis, and Narcotics Quality (TRANQ) Research Act of 2023 includes a provision for us to examine the capabilities of the federal government and state and local agencies to detect, identify, and analyze new psychoactive substances—referred to in this report as emerging street drugs.[8] This report describes (1) methods and technologies that are available or in development for emerging street drug analysis at federal and selected state and local laboratories or in the field, (2) timelines for developing new methods and technologies, (3) federal grant programs funding the development of new methods and technologies, and (4) federal and selected state and local facilities that analyze emerging street drugs and the key challenges they face.

To address these objectives, we gathered and analyzed documentation and interviewed officials from seven federal agencies that use, develop, or fund the development of drug analysis methods and technologies. We visited or interviewed officials from 15 state and local (i.e., county and city) laboratories selected from three distinct regions of the U.S. We also interviewed additional stakeholders, including grantees and technology manufacturers. We reviewed scientific literature describing drug analysis methods and technologies that are in use or in development. For more information on objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key Drug Analysis Definitions

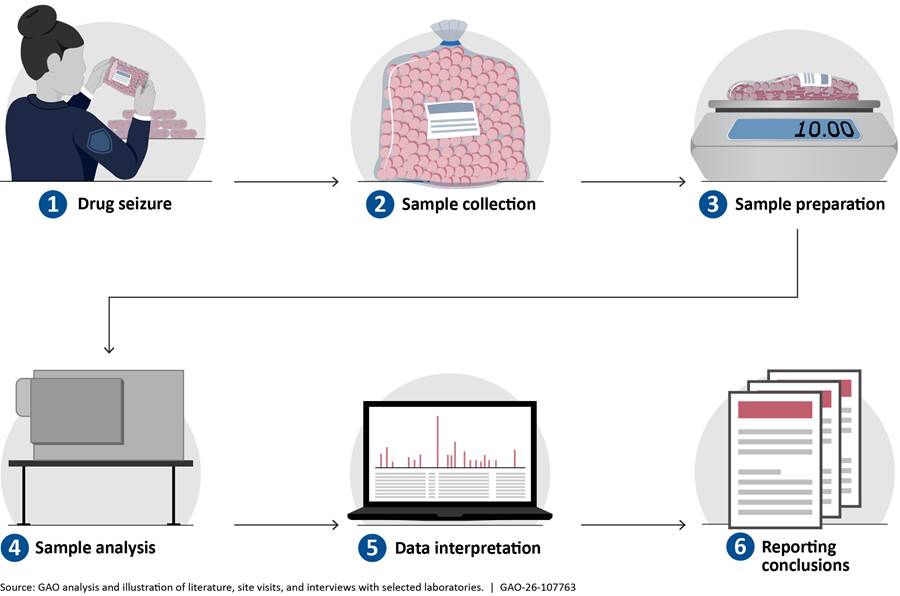

Drug analysis involves the detection and identification of drugs in samples using various methods and technologies. Detection refers to the determination that a drug or its metabolites are present in a sample.[9] Identification refers to the specification of which drug is present in a sample. In addition to detection and identification, analysis can also include studying how much of the drug is present in a sample and the drug’s corresponding chemical or physical properties.

There are two primary categories of drug analysis: drug chemistry and toxicology. Drug chemistry involves the testing of seized drugs or drug residues present on drug paraphernalia (e.g., syringes). Toxicology involves testing biological samples (e.g., blood, saliva, or urine) that may contain drugs or drug metabolites. Crime laboratories that do drug toxicology usually test urine or blood samples in suspected nonfatal drug use cases to determine impairment. Medical examiners, coroners, or similar officials are responsible for determining cause of death with postmortem toxicology (e.g., testing blood samples from people who died from a suspected overdose).

Federal Roles in Emerging Street Drug Analysis

Several federal agencies contribute to drug control efforts, including the analysis of emerging street drugs. Federal actions include policy development, drug analysis, and research funding. Multiple federal agencies, including DEA, analyze drugs, analyze drug paraphernalia, or conduct drug toxicology work, which we discuss in detail later in this report. Each agency has different testing jurisdictions, and officials told us that agencies collaborate when those jurisdictions overlap. Likewise, federal agencies may award grants related to drug analysis and other drug control initiatives. In addition to the grants discussed later in this report, the Department of Justice (DOJ) also provides annual funds under the Paul Coverdell Forensic Science Improvement Grants Program (Coverdell grants).[10] Coverdell grants for state and local laboratories aim to improve forensic services by providing funding to improve the quality and timeliness of forensic science or medical examiner services, address emerging forensic science issues, and train staff, among other things. Appendix II provides additional details on the key federal departments and agencies involved in emerging street drug analysis efforts.

Analysis Challenges for Emerging Street Drugs

The rapidly evolving landscape of emerging street drugs and other aspects of the street drug market present unique analysis challenges for scientists. First, even if a technology detects the presence of an emerging street drug, scientists usually cannot confirm the identity of that chemical without comparing their results to a reliable sample, known as a reference standard, which may not be available for a new substance.[11] Second, street drug mixtures are becoming increasingly complex, which may increase the need for technologies that separate chemicals or can differentiate similar chemical signals. Finally, chemicals of interest can be present in very small amounts in emerging street drugs and may be below the detection limits for some technologies or masked by larger amounts of other components, such as cutting agents.

Current Technologies Can Often Analyze Emerging Street Drugs, but New Methods and Technologies May Enhance Capabilities

Federal, state, and local entities identify emerging street drugs using a variety of laboratory- and field-based technologies. Although these technologies are often effective when the right methods and reference standards are available, stakeholders such as federal agencies, technology manufacturers, and academics are developing new methods and technologies to further enhance analytical capabilities. These efforts include methods to standardize data analysis between laboratories and technologies for drug analysis in the field.

Current Laboratory-Based Technologies Can Often Analyze Emerging Street Drugs

Scientists use multiple types of methods and technologies to analyze emerging street drugs during their routine casework. Routine drug chemistry analysis typically involves an initial screening to identify the class of chemicals (e.g., opioids) or the drug present in a sample, followed by an analysis to confirm the specific identity of chemicals present. See appendix III for more details on routine analysis procedures. Beyond routine analyses, some laboratories may use additional specialized technologies to identify emerging street drugs. Table 1 summarizes selected technologies available for drug analysis based on observations from our site visits and interviews with officials from selected federal, state, and local laboratories. For more detailed descriptions of the technologies, see appendix IV.[12]

Table 1: Technologies Commonly Used by Selected Federal, State, and Local Laboratories for Drug Analysisa

|

Technology type |

Technology |

Screening or confirmation |

Sample type |

Used by federal laboratories |

Used by state and local laboratories |

|

Mass spectrometry (MS) |

Gas chromatography-MS (GC-MS) |

Both |

Seized drugs Toxicology |

|

|

|

Liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS) |

Both |

Seized drugs Toxicology |

|

|

|

|

Spectroscopy |

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) |

Both |

Seized drugs |

|

|

|

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) |

Confirmation |

Seized drugs |

|

|

|

|

Other |

Color tests |

Screening |

Seized drugs |

|

|

Source: GAO analysis of site visits and interviews with selected laboratories. | GAO‑26‑107763

aThe selected federal laboratories are the six that we visited as a part of our methodology (see app. I). The selected state and local laboratories are those we either visited or interviewed. The selected technologies in this table are those that we observed in at least half of the selected federal, state, or local laboratories.

Mass Spectrometry Technologies

Most forensic scientists consider gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) the gold standard technology to detect and identify street drugs in drug chemistry laboratories (fig. 1). All federal, state, and local laboratories we visited or spoke to use GC-MS for confirmation of drug identities.

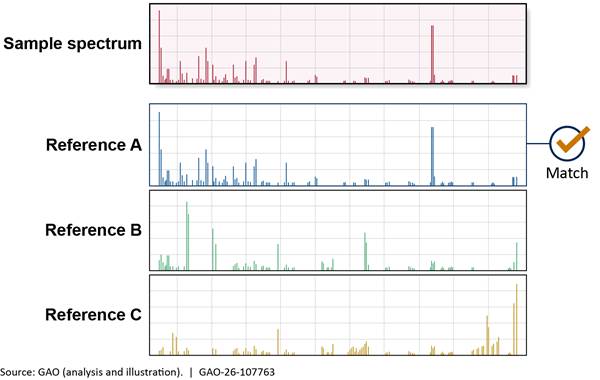

GC first separates the individual chemicals in a mixture, and then MS converts chemicals to ions (electrically charged particles) and provides information about a chemical’s identity based on the ions’ mass-to-charge ratios, creating a chemical “fingerprint” called a mass spectrum. Scientists then match the mass spectrum of the analyzed sample to a reference mass spectrum of a known reference standard to confirm the identity of the chemical (fig. 2).

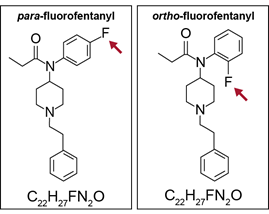

GC-MS has limitations, however, including inabilities to analyze some types of chemicals and to distinguish between some similar drugs. Because GC-MS requires a sample to be in the gas phase, it is not well-suited for chemicals that do not vaporize easily or that break down at high temperatures. Furthermore, GC-MS cannot always differentiate between chemicals that have the same chemical formula but different structural arrangements, such as para-fluorofentanyl and ortho-fluorofentanyl (see sidebar).[13] Researchers are working on new data processing methods that may overcome this limitation.

|

para- and ortho-Fluorofentanyl

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107763 Chemicals with identical chemical formulas but different structures, like para-fluorofentanyl and ortho-fluorofentanyl, pose a challenge in sample analysis. Both chemicals share the same chemical formula (C22H27FN2O), differing only in the position of a single fluorine atom in their chemical structure (see red arrows). While both are potent synthetic opioids related to fentanyl, their subtle structural differences mean that they may interact with biological systems in distinct ways, leading to varied potencies and effects. Source: GAO analysis of literature. | GAO‑26‑107763 |

Scientists also use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for drug detection and identification. Scientists generally use LC-MS more for toxicology than drug chemistry. This technology is well-suited for difficult-to-vaporize or thermally unstable compounds but often requires extensive sample preparation. Some specialized types of LC-MS incorporate technology that helps distinguish between similar chemicals. Scientists can use this technology to identify unknown chemicals at lower concentrations, but it is more expensive to acquire and maintain than GC-MS.

Direct analysis MS technologies are newer technologies for drug analysis and offer rapid screening capabilities. Two federal and one state laboratory we spoke to use direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry (DART-MS) as a screening technology, and several others expressed interest in using it. DART-MS can rapidly analyze street drugs with minimal sample preparation, but the cost and required operational expertise impede widespread use. An official at a local laboratory told us they recently incorporated a different type of direct analysis MS that is less expensive than typical DART-MS for screening. The official told us scientists have found it to be effective for identifying chemicals, such as nitazenes, in a few minutes that would otherwise require long (more than 30-minute) GC-MS methods.

Spectroscopy Technologies

Scientists can also use spectroscopy to identify drugs, but the usefulness of these technologies usually depends on the purity of the samples. Spectroscopy uses unique interactions between light and matter to identify chemicals. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy are complementary technologies that scientists use primarily to confirm the identity of relatively pure substances, though some laboratory officials we spoke to are beginning to use Raman more frequently in their screening procedures. Both technologies have limited capabilities for analyzing small amounts of drugs or complex mixtures. Raman can identify drugs through some types of sealed, transparent containers; however, it is also susceptible to fluorescence interference.[14]

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a highly specialized technology that scientists use to determine the chemical structure of unknown street drugs. This technology requires relatively pure samples, involves complex analysis, and is expensive to acquire and maintain. Therefore, state and local laboratories we visited generally do not have NMR. Instead, its users among laboratories we observed are primarily federal research-oriented facilities, such as DEA’s Special Testing and Research Laboratory and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s National Forensic Laboratory.

Available Field-Based Technologies Can Rapidly Analyze Drugs but Face Accuracy Challenges

Field-based technologies can provide user-friendly, rapid analysis of street drugs. Law enforcement uses these technologies—often miniaturized, portable versions of traditional laboratory benchtop technologies—for analysis at the point of seizure, and laboratory scientists use them for rapid screening tests. The most common field-based technologies for drug analysis include portable Raman, FTIR, and mass spectrometers (fig. 3). In addition, immunoassay test strips are inexpensive, rapid drug checking tests that function similarly to COVID-19 test strips.[15] CBP officers and agents use a range of portable technologies with varying capabilities, including FTIR, Raman, and a combination of both, for identifying drugs, drug precursors, cutting agents, and other chemicals. Four state and local laboratories we spoke to use portable Raman technologies in routine drug analysis.

Field-based drug detection technologies, however, can be less accurate in practice than laboratory-based technologies due to factors including user error and inherent technological limitations. Insufficient training can lead to improper use and inaccurate results. For example, scientists told us that untrained officers and agents may overload samples into the mass spectrometer, which can cause processing delays and contaminate subsequent drug tests. Furthermore, an untrained user may not always understand the strengths and limitations of field-based technologies well enough to interpret results accurately, especially for emerging street drugs. Technology manufacturing representatives told us they are working to create more lay-friendly user interfaces and operational methods.

Technological limitations further contribute to lower accuracy. Laboratory officials we spoke with expressed concerns about the reliability of drug test strips when used in the field. According to scientific literature, test strips may yield false positives from cross-reactivity with non-target chemicals and have inconsistent performance due to manufacturing variability. To address this challenge, NIST recently awarded a grant to AOAC International (an independent, nonprofit association) for developing standards to improve the reliability of drug test strips.[16] Additionally, DEA officials told us that using these strips according to manufacturer specifications, validating them appropriately, and using negative and positive controls can help address some of these limitations. Field-based Raman and FTIR technologies face the same limitations as the laboratory-based versions discussed above, as well as challenges unique to the field, such as environmental factors.

In addition to accuracy concerns, some organizations prohibit the use of certain field-based technologies that require officers and agents to directly handle a suspected street drug due to the risk of exposure. For example, four state and local laboratories we spoke to are in jurisdictions that discourage the use of test strips by officers and agents in the field because of safety concerns or reliability issues.

New Methods and Technologies May Enhance Analysis Capabilities

New methods and technologies present opportunities to enhance current drug analysis capabilities by developing new data processing methods through machine learning, standardizing laboratory processes, and enabling safer drug analysis in the field. The following details these potential advancements:

· New data processing methods. Federal agencies, academics, and technology manufacturers we spoke to are developing new data processing methods using machine learning and other algorithms to improve the interpretation of complex analytical data. For example, researchers developed a machine learning model to identify new fentanyl analogs from Raman spectra.[17] New data processing methods may also reduce reliance on spectral libraries.[18] Normally when scientists analyze an unknown sample, they compare the spectrum of the unknown substance to the spectral library to find the best match and identify the chemical. Many field-based technologies automate this matching process to make the analysis more accessible for users. However, if the spectral library has not been recently updated to include spectra of new chemicals, such as a new fentanyl analog, the field-based technology may yield an inconclusive result when analyzing a sample that contains the new chemical. According to the manufacturers, one commercially available portable mass spectrometry system uses advanced data processing algorithms to rapidly identify whether a sample contains a fentanyl analog without reference spectra, reducing reliance on traditional spectral library updates.

· New methods for standardized laboratory analysis. To promote standardized analysis and reporting, DEA Special Testing and Research Laboratory developed the Global Uniform Analysis and Reporting of Drug-related Substances (GUARDS) method. According to DEA officials, this GC-MS method was made available in December 2024, and a key benefit is the ability to enable easier cross-laboratory comparison of data. This method separates and identifies over 300 controlled and non-controlled substances in a single, 15-minute analysis. Officials told us this method is currently undergoing verification at a number of CBP laboratories, and DEA has begun introducing this method to forensic scientists, including those from state and local laboratories, at scientific conferences and meetings. Despite the intended benefits, officials at most of the 21 laboratories we spoke to were unaware of the method (nine laboratories—one federal and eight state or local) or were not interested in adopting it (six laboratories—one federal and five state or local).[19] Those that were not interested cited specific operational needs or described implementation as a hassle due to the number of changes required. At only three laboratories—two federal and one local—were officials interested in adopting the method.

· New methods and technologies for minimizing exposure risk in the field. Officials we spoke to at multiple agencies reported planning to fund projects to detect fentanyl vapor without requiring an officer or agent to handle the drug. The Department of Defense is funding the development of a portable technology designed to detect fentanyl vapor with high sensitivity.[20] The Department of Homeland Security’s Science & Technology Directorate, in collaboration with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and the DOJ’s National Institute of Justice, in collaboration with the Naval Research Laboratory, are also independently working on similar projects.

Updating or Developing Methods Is Faster and Can Be More Practical than Developing New Technologies

Forensic scientists often find it more practical to update or develop methods rather than integrate new technologies into their workflows for identifying emerging street drugs. Updating and developing methods—which we categorize below as operational methods, new applications methods, and data processing methods—generally require shorter timelines and fewer resources than developing new technologies. Developing a new technology can take a year or more and presents significant hurdles to adoption, such as high costs and lengthy validation requirements.

Updating and Developing Methods Can Take Minutes to Years Depending on Method Type, Validation, and Resources

Development timelines vary depending on the method type and associated requirements. We organized different types of methods into three categories: (1) operational methods – protocols for routinely used drug analysis technologies, (2) new application methods – protocols for applying existing technologies to drug analysis which had previously not been widely adopted for this purpose, and (3) data processing methods – protocols for processing output data from drug analysis technologies. While current operational methods may be updated quickly, developing new application or data processing methods that require validation can result in extended timelines, sometimes spanning years, before they are incorporated into routine analysis work. According to laboratory officials, forensic laboratories updated or developed new operational methods for current drug analysis technologies to help address changing regional drug trends. Academic and government research institutions also update methods or develop new operational, application, or data processing methods.

The following provides more detail on the timelines for these three categories of methods:

· Operational methods take minutes to 1 month to update or develop. According to officials, minor updates to current operational methods that do not require method validation can be done relatively quickly, sometimes within minutes.[21] Developing new operational methods can have variable timelines depending on complexity. For example, officials from the U.S. Postal Inspection Service told us they spent several days developing a new GC-MS method to separate a drug adulterant called BTMPS from the street drug carfentanil.[22] In contrast, officials from a local laboratory told us that it took 1 month to develop and implement a GC-MS method to separate the street drug phencyclidine (PCP) from a PCP analog.[23]

· New application methods may take months to years to develop. The timeline for developing new application methods varies. For example, NIST officials told us they developed a DART-MS method for drug analysis in about 4 months, though additional factors extended the timeline for implementation (see below). On the other hand, a representative from one academic institution told us that researchers are developing sample preparation methods to differentiate closely related chemical forms to make it easier for forensic scientists to identify the specific compounds present. These methods require more extensive research and optimization and may take several years before they are ready for routine use in a laboratory.

· Data processing methods often take at least 1 year to develop. Like new application methods, the timeline to develop data processing methods varies depending on the goals of the analysis. For example, a technology manufacturer told us they developed the data processing algorithm for their portable mass spectrometer discussed above in 18 months. Data processing methods for more complex analyses, such as distinguishing between chemicals that have the same chemical formula but different structural arrangements (see the para- and ortho-fluorofentanyl sidebar), may take longer to develop. For example, a representative of an academic institution told us researchers have spent 3 to 4 years developing such a method using GC-MS data. While the method is available now, these researchers estimate that 3 to 5 years of additional work are needed before the method can be incorporated into existing software for widespread use at forensic laboratories.

Beyond the initial development phase, method validation and resource constraints can extend the timelines required to implement new analytical methods in forensic laboratories, regardless of the method type. Method validation and verification may extend the timelines from months to a year or longer.[24] According to DEA officials, updating a method for a new analog of a known drug, like fentanyl, is generally faster than developing one for an entirely new chemical, primarily due to the time it takes to validate and verify the latter type of method. NIST officials told us their DART-MS method, discussed above, took 4 months to develop and an additional year to validate.

Resource constraints also affect method development timelines. According to government officials, creating a new method requires staff with the appropriate expertise and time to devote to the project. Officials at two local laboratories told us that a lack of staff with the time or skill set for method development is a challenge, while officials from another noted that they do not develop new GC-MS methods due to staffing constraints and large caseloads.

New Technology Can Take at Least a Year to Develop and May Not Be Practical to Adopt

Federal agency officials and technology manufacturing representatives said that it can take at least a year to develop new drug analysis technologies, including significant research and development, prototyping, and validation. Officials from the Naval Research Laboratory described this process as often occurring in multiple stages over several years before a technology is ready for the field. Even a successful prototype faces significant challenges in the transition to a fully operational and supported product, a phenomenon often referred to as the “valley of death.”[25]

The adoption of new technology can present practical challenges for state and local laboratories. Officials from several state and local laboratories told us that long development timelines and lengthy validation requirements can make adopting a new technology challenging. For any new technology, validation is necessary before laboratories can use it for accredited casework and can take 1 year, depending in part on technology complexity.

Training staff on a new technology also takes time away from casework, further affecting practicality. Revising established standard operating procedures can also delay adoption. These lengthy timelines and resource demands lead some laboratories to favor updating what they already have. For example, an official at a local laboratory told us their scientists prefer to update their existing, trusted technologies rather than acquire new types of technologies because they are more familiar with those technologies and know how to operate them.

Federal Agencies Award More Grants for Development of New Methods Than Technologies to Analyze Emerging Street Drugs

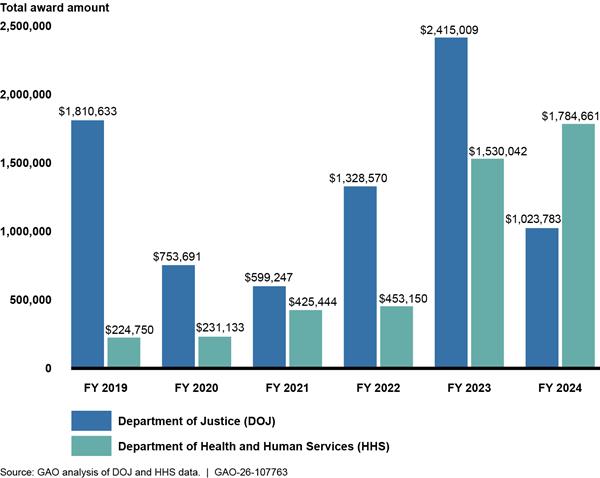

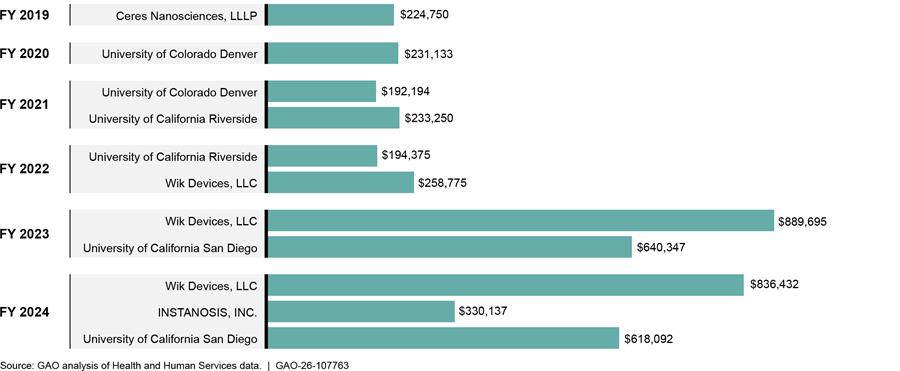

Federal grant programs awarded by two federal agencies, DOJ and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), funded method and technology development projects for the analysis of emerging street drugs from fiscal year (FY) 2019 through 2024 (fig. 4). As discussed above, we organized different types of methods into three categories: operational methods, new application methods, and data processing methods (see app. I for details of our methodology). The grants focused largely on the development of new application methods for analysis using existing technologies. Awards went to a variety of recipients, including academic institutions, nonprofits, federal agencies, and other drug analysis facilities.

Figure 4: Total Award Amount of DOJ and HHS Grants for Emerging Street Drug Analysis Method and Technology Development by Fiscal Year (FY), 2019 Through 2024

Note: The dollar amounts given in this figure are not adjusted for inflation. See appendix V for more details on the individual grants.

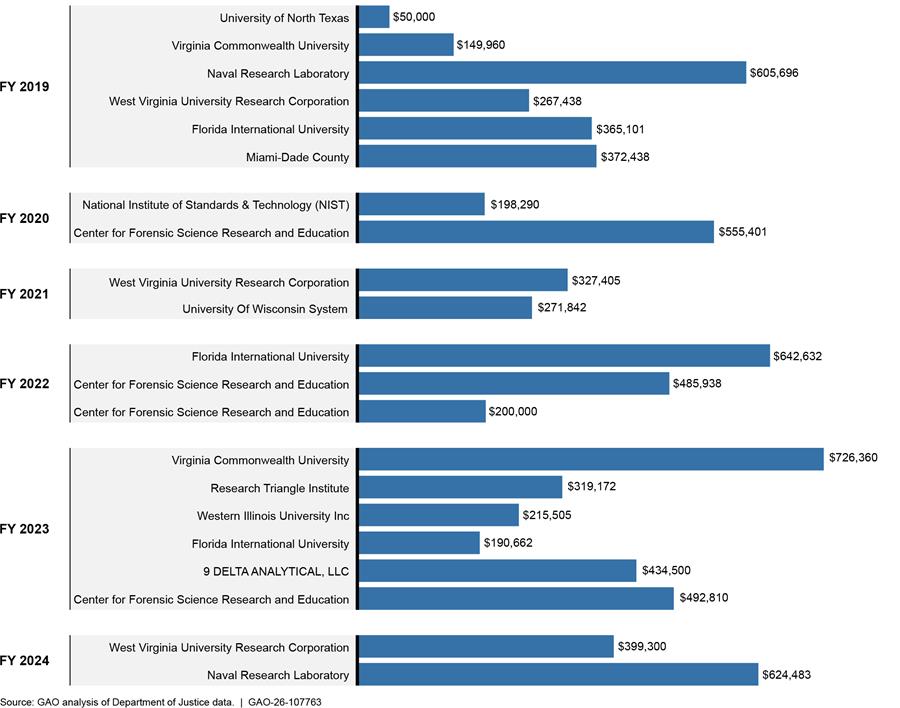

DOJ Awarded $7.9 Million in Grants Primarily to Fund Development of New Methods for Analyzing Emerging Street Drugs During FY 2019 through 2024

Over a 6-year period—FY 2019 through 2024—DOJ awarded about $7.9 million for 19 unique projects related to the development of new methods and technologies for analyzing emerging street drugs (an annual average of $1.3 million in awards, see fig. 5).[26] Seventeen of the 19 projects focused on the development of new methods and two on the development of new technologies. Grant recipients included academic institutions (11 projects), two nonprofits, one private company, two federal agencies, and one county medical examiner.

Figure 5: Department of Justice (DOJ) Grants for Emerging Street Drug Analysis Method and Technology Development by Fiscal Year (FY), 2019 Through 2024

Note: The dollar amounts given in this figure are not adjusted for inflation. All funds awarded to the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education were directly received by its parent foundation—the Fredric Rieders Family Renaissance Foundation. See appendix V for more details on the individual grants.

These awards were made from three different grant programs, none of which are specifically designated for drug analysis purposes but rather for general criminal justice and forensic science research activities. The following highlights the three projects that were awarded the most funding during the 6-year period:

· DOJ awarded the parent foundation of the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education—the Fredric Rieders Family Renaissance Foundation—a combined total of $978,748 in FY 2022 and 2023 for a project entitled “Implementation of NPS Discovery – An Early Warning Systems for Novel Drug Intelligence, Surveillance, Monitoring, Response, and Forecasting using Drug Materials and Toxicology Populations in the US.” This is a multidisciplinary project which includes developing new confirmatory methods in toxicology for emerging street drugs. The grantees have issued many publicly available reports under this grant.[27]

· DOJ awarded the parent foundation of the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education a combined total of $755,401 in FY 2020 and FY 2022 for another project entitled “Real-Time Sample-Mining and Data-Mining Approaches for the Discovery of Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS).” This project includes the development and validation of confirmation methods for the identification of emerging street drugs in toxicology. The grantees have issued many publicly available reports under this grant.[28]

· DOJ awarded the Virginia Commonwealth University $726,360 in FY 2023 for a project entitled “Analytical Challenges with Proliferating THC Analogues.” This project includes the development and validation of methods for analyzing e-liquids (used in e-cigarettes), edibles, and toxicological samples for emerging synthetic cannabinoids. As of August 2025, the grantees have issued two peer-reviewed publications under this grant.[29]

HHS Awarded $4.6 Million in Grants Largely for New Methods for Analyzing Emerging Street Drugs During FY 2019 through 2024

Over a 6-year period—FY 2019 through 2024—HHS awarded about $4.6 million for six unique projects related to the development of new methods and technologies for analyzing emerging street drugs (an annual average of $775,000 in awards, fig. 6).[30] Three of the six grants, totaling $2.6 million, focused on the development of new methods while the other three focused on development of new technologies. Grant recipients included three academic institutions and three private companies.

Figure 6: Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Grants for Emerging Street Drug Analysis Method and Technology Development by Fiscal Year (FY), 2019 Through 2024

Note: The dollar amounts given in this figure are not adjusted for inflation. See appendix V for more details on the individual grants.

HHS awarded four of the six identified grants through general National Institutes of Health research solicitations.[31] HHS funded the other two grants through Small Business Innovation Research programs.[32] Two of the grant solicitations aimed to fund research related to emerging street drugs. The other four grants originated from solicitations focused on other research and development efforts. The following highlights the three projects that were awarded the most funding during the 6-year period:

· HHS awarded Wik Devices, LLC a combined total of $1,984,902 in FY 2022, FY 2023, and FY 2024 for a project entitled “All-in-one Device for Forensic Toxicology Drug Screening.” This project proposed the development of a method to apply a unique type of mass spectrometry to drug analysis of toxicological samples. As of August 2025, the grantees have published three peer reviewed publications under this grant.[33]

· HHS awarded the University of California San Diego a combined total of $1,258,439 in FY 2023 and FY 2024 for a project entitled “Development and validation of a novel point-of-care technology for rapid non-targeted identification of emerging opioid and other drug threats.” This project proposed the development and validation of a new technology for rapid identification of emerging street drugs. As of August 2025, the grantees had no publications or patents associated with this grant.

· HHS awarded the University of California Riverside a combined total of $427,625 in FY 2021 and FY 2022 for a project entitled “Rapid and responsive development of ‘spice’ sensors using a novel recognition scaffold.” This project proposed the development of a new technology for detecting synthetic cannabinoids in toxicological samples using a sensor system that is found in plants. As of August 2025, the grantees have published four peer-reviewed publications under this grant.[34]

Crime Laboratories and Other Facilities Analyze Emerging Street Drugs but Report Key Challenges

Facilities across the country, such as crime laboratories and medical examiner offices, conduct emerging street drug analysis. Each of these facilities analyzes street drugs according to their mission, whether that is confirming drug identity for court proceedings or understanding the cause behind an overdose death. However, facilities consistently describe key resource and reporting challenges that can hinder their ability to effectively analyze emerging street drugs and contribute to the understanding of emerging drug trends across the country. If these challenges could be addressed, laboratories could be in a better position to meet the nation’s needs for emerging drug analysis. However, we are not making recommendations to address these challenges because they are primarily faced by state and local laboratories.

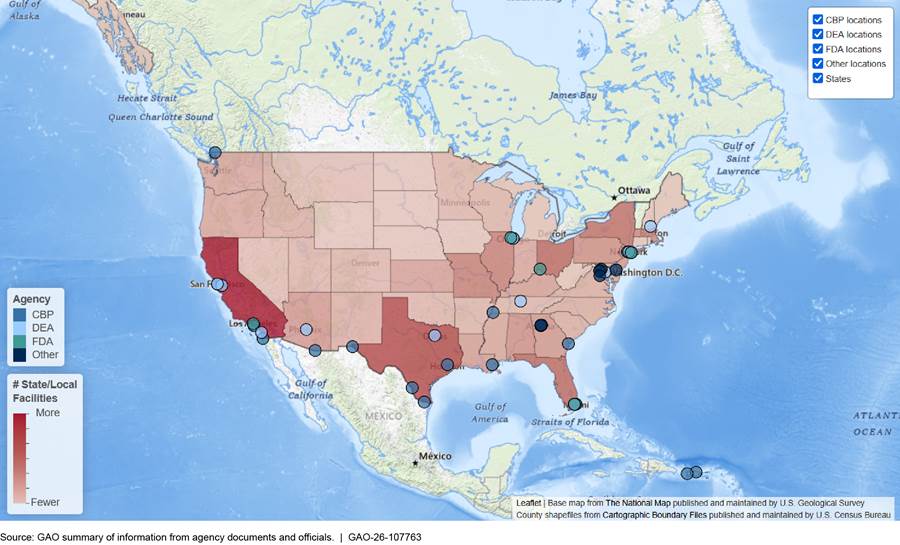

Facilities Analyze Emerging Street Drugs According to Their Missions

As can be seen in figure 7, numerous federal, state, and local laboratories analyze drugs across the country. See https://files.gao.gov/multimedia/gao-26-107763/interactive/index.html to view an interactive version of this map. At the state and local levels, the map includes only laboratories that participated in the DEA’s National Forensic Laboratory Information System in 2024. It does not include other types of facilities that analyze drugs, such as private laboratories, medical examiner offices, or other public health locations, such as drug-checking sites.

Note: This map shows the number of state and local laboratories that participated in the Drug Enforcement Administration’s National Forensic Laboratory Information System in 2024. State and local laboratories that did not participate in 2024 are not represented in this map.

Federal Laboratories

Federal agencies that we spoke to reported that their drug chemistry laboratories generally have separate facilities for complex and routine analyses. Centralized facilities, such as DEA’s Special Testing and Research Laboratory or the U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s National Forensic Laboratory, have technology and staff capable of complex analyses and research on drugs or drug paraphernalia, including determining the chemical structure of an unknown drug component.[35] Regional laboratories, on the other hand, generally conduct more routine drug identification work. For example, the DEA Mid-Atlantic regional laboratory does full analysis of DEA-seized drug samples from multiple states in its region. If scientists at this laboratory cannot identify a substance, they will send samples and data to the DEA Special Testing and Research Laboratory for further analysis. DEA, CBP, and NIST’s RaDAR program (see sidebar) also have mobile laboratories available or in development for rapid on-site drug chemistry analysis.[36]

|

RaDAR Mobile Laboratory The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Rapid Drug Analysis and Research (RaDAR) program is currently constructing a mobile laboratory. Once completed, it will be equipped with laboratory- and field-based technologies. According to NIST officials, the mobile laboratory has three primary objectives: 1. Enable acquisition of high-quality data in real time through on-site drug testing. 2. Define technology requirements and accelerate technology development and deployment by data-driven comparisons between laboratory- and field-based technologies. 3. Advance NIST RaDAR research to ensure agile analytical capabilities that can keep pace with the dynamic drug landscape. Source: NIST documents and officials. | GAO‑26‑107763 |

A few federal agencies reported analyzing emerging street drugs through toxicology. For example, the Department of Defense’s Office of Drug Demand Reduction operates a surveillance program out of its laboratory at the Dover Air Force Base that monitors emerging street drugs and trends in randomly selected samples from their military and civilian workforce drug testing program. DEA also sponsors the analysis of emerging street drugs in toxicological samples through their contract with the University of California San Francisco (see sidebar).

|

DEA Toxicology Testing Program The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Toxicology Testing Program tests biological samples from drug overdose victims for identification of emerging street drugs. Currently, the program analyzes submitted samples for 1,314 different drugs. This program emerged out of a collaboration between University of California San Francisco and DEA using the university laboratory’s discretionary funding from 2012 to 2018. In 2019, the DEA initiated a contract with investigators at the university to formalize the partnership after a bid solicitation process. DEA awarded the university a second contract in 2024, which extends the partnership into 2029. Source: DEA officials and DEA Toxicology Testing Program representatives. | GAO‑26‑107763 |

Federal agencies reported engaging in partnerships for drug identification with other federal agencies, state and local laboratories, academic laboratories, and private laboratories. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) partnered with CBP in 2018 pursuant to the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act to begin a satellite lab program for drug identification at the largest international mail facilities in Chicago, New York, Miami, and Los Angeles.[37] According to FDA officials, this program reduced infrastructure costs and facilitated more rapid information sharing between the two agencies. FDA and CBP also partner with DEA through the new Joint Intelligence National Threat Response – El Paso Illicit Drug Laboratory (Joint INTREPID Lab, see sidebar). As another example, CDC provides funding to NIST for the development of new testing methods for drug products and paraphernalia as well as rapid testing of up to 10,000 samples per year to support timely identification and tracking of emerging street drugs.[38] As an example of partnerships with state and local laboratories, NIST researchers worked with scientists at over 20 federal, state, and local laboratories to help them implement the NIST-developed DART-MS method.[39] Partnerships with private laboratories include the development of the Emergent Drug Panel kit by Cayman Chemical through a contract with CDC. This kit contains reference standards for multiple fentanyl analogs and other emerging drugs for free distribution to approved requesters. This contract expired in September of 2024, and renewal options, if any, have not been exercised, according to CDC officials and Cayman Chemical representatives.

|

Joint INTREPID Lab The Joint Intelligence National Threat Response – El Paso Illicit Drug (INTREPID) Laboratory is a collaboration between the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The mission of this collaboration is for these agencies to work together to provide actionable intelligence, scientific support, and research to the intelligence community. Work for the Joint INTREPID Lab is ongoing but is not currently fully integrated, according to officials. The Joint INTREPID Lab collaboration began in 2023 with a focus on fentanyl and affiliated emerging threats. In fiscal year 2024, the collaboration was able to process 77 unique samples at CBP, DEA, and FDA laboratories around the country. This collaboration will eventually be integrated and housed in the El Paso Intelligence Center. Source: DEA and CBP documents and officials. | GAO‑26‑107763 |

Selected State and Local Laboratories

As can be seen in figure 7 above, the number of public laboratories at the state and local levels varies widely from state to state. For example, Virginia has one state system with multiple regional laboratories and no local laboratories. In contrast, Louisiana has only one state laboratory but multiple local laboratories. We included a selection of 15 state and local laboratories in our review (see app. I for our selection methodology). All selected state and local laboratories conduct drug chemistry analysis and about half also do forensic drug toxicology. The laboratories that do not have toxicology facilities or technology may contract that testing out to private laboratories, according to the state and local laboratory scientists we spoke to.

Scientists at state and local laboratories reported analyzing samples submitted from many different sources, including federal agencies. All 15 state and local laboratories in our review analyze samples beyond their corresponding law enforcement entities. For example, a county laboratory affiliated with the local sheriff’s office may also analyze samples submitted by universities; detention centers; and federal, state, local, and tribal agencies within that county. Scientists we spoke to at one local crime laboratory said they serve 40 different law enforcement agencies. Fourteen of the 15 state and local laboratories also analyze samples submitted by federal agencies, such as DEA and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[40] An official from one state laboratory estimated that the laboratory spends millions of dollars each year analyzing federally submitted items. The official said the laboratory is not reimbursed by the federal agencies, straining an already limited operational budget. According to laboratory officials, federal agencies may submit samples to state and local laboratories if the drug seizure is linked with a state or local task force or because of faster turnaround times compared to federal laboratories. DEA officials agreed that they may submit samples to state and local labs if the drug seizure is affiliated with a state or local task force and added that having an alternate testing laboratory close to the seizure can be convenient when there is not a DEA laboratory nearby. DEA officials also told us that while turnaround times may have been an issue in the past, their laboratories currently analyze most pieces of evidence within 28 days.[41]

Scientists at state and local laboratories reported using a patchwork of funding to operate their drug analysis programs. Budget allocations are the primary funding source for law enforcement analysis programs. States and localities decide how much funding to allocate at each level, and those amounts vary across the country. Coverdell grants awarded by DOJ provide supplemental funds to state and local laboratories. In recent years, some state and local laboratories have also used funds from opiate settlement cases to support ongoing opioid-related enforcement efforts. For example, some have purchased updated equipment for their seized drug analysis department.

Other Laboratories and Facilities

Private laboratories across the U.S. analyze emerging street drugs and support public laboratories, according to officials we spoke with. For-profit laboratories can help offset caseloads from federal, state, and local laboratories or be a resource to regions of the U.S. that do not have public laboratories. For example, five of our 15 selected state and local laboratories outsource toxicology analysis to for-profit laboratories or did so in the past. Nonprofit laboratories can support public laboratories with emerging street drug identification and research. For example, the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education serves a unique role by fully determining the chemical structure of unknown drugs in toxicological samples, as well as rapidly sharing their findings with the public through their NPS Discovery program, which is funded by grants from DOJ, among other activities.

Public health services across the country also have drug analysis capabilities. Medical examiners may analyze emerging street drugs in postmortem toxicological samples themselves or outsource to other laboratories based on available resources, according to representatives from the National Association of Medical Examiners. CDC provides funding to state and local public health facilities through their Overdose Data to Action Program.[42] Through the state-focused program, CDC funds 49 states and Washington, DC to collect and report information about drug overdose deaths to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System and to distribute funds to medical examiner and coroner offices for enhanced postmortem toxicology testing.[43] CDC also funds 19 states and Washington, DC to establish toxicology testing of suspected nonfatal overdoses in emergency departments. And, CDC funds 18 local public health departments to test street drug products or paraphernalia. According to CDC officials, 12 of the 18 local health departments receive additional funding to support their medical examiner or coroner offices’ drug overdose investigations and data sharing with funded local public health departments. Finally, drug checking services, where drug users can confirm the contents of their drugs, may conduct some on-site analysis coupled with confirmatory testing or outsource the analysis to available laboratories.

Laboratories Described a Lack of Essential Resources

Most of the key challenges described by state and local laboratories we visited or interviewed stem from a lack of resources. We summarize these challenges in table 2 below. While we present the challenges separately, many of these challenges interrelate. For example, if a laboratory is understaffed, it also cannot afford to lose staff time to update new methods.

|

Challenge |

Examples |

Federal laboratories |

State and local laboratoriesb |

|

Staffing |

Understaffed High turnover Hiring freeze |

|

|

|

Funding |

Technology acquisition Technology maintenance |

|

|

|

Time |

Method development Technology validation Staff training |

|

|

|

Technology |

Aging technology Expensive service contracts |

|

|

|

Infrastructure |

Lack of space Maintenance challenges Retrofitted office buildings |

|

|

|

Reference standards |

Expensive to acquire Not available when needed |

|

|

Source: GAO analysis of site visits and interviews with officials at selected laboratories. | GAO‑26‑107763

aThe selected federal laboratories are the six that were visited as a part of our methodology (see app. I).

bIncluded in this count is an additional local laboratory that we spoke to as a part of our initial background information collection prior to our formal state and local selection process.

Staffing. One of the most frequently described challenges by officials from the selected federal, state, and local laboratories was staffing, which can affect a laboratory’s capacity for testing emerging street drugs and updating methods. Stakeholders we spoke to attributed staffing challenges to factors including insufficient funding to hire to the desired levels, competition with other laboratories, and space constraints. Laboratories with insufficient staff may not be able to develop or validate methods for emerging street drug analysis without taking time away from routine casework. Furthermore, laboratories may not have dedicated staff with a research and development skill set, which can limit their capacity to develop or implement new methods and technologies.

The recent national hiring freeze, which began in January 2025, has also affected staffing at federal laboratories. For example, officials from the DEA Mid-Atlantic laboratory stated that they were not sufficiently staffed, in part due to the current hiring freeze. CBP officials at one forward operating laboratory also stated that the hiring freeze prevented them from onboarding a fourth chemist. The officials at this forward operating laboratory consider four chemists to be the correct staffing level for their facility because two chemists need to be present to open narcotics samples. Having four chemists on staff would allow the laboratory to have two shifts of two chemists.

Funding. The other most frequently described challenge by officials from the selected state and local laboratories was the lack of funding to do drug analysis. Multiple stakeholders corroborated this challenge, pointing out that many state and local agencies have limited funding for acquiring new technologies, maintaining current technologies, and acquiring new reference standards, among other things. Funding for state and local laboratories originates from a patchwork of sources, as described above. Without appropriate funding to be fully equipped, modernized, and staffed, a laboratory may not be able to keep up with its caseload or analyze emerging street drugs.

Time. Officials from selected federal, state, and local laboratories described a lack of time as a key challenge affecting their ability to analyze emerging street drugs, especially given the rapidly changing street drug market. In addition to lengthy staff training procedures, laboratory officials and other stakeholders described time-consuming technology validation and method development procedures that take away time from drug analysis. Furthermore, laboratories may be under time constraints due to court proceedings, which can affect how scientists prioritize submitted samples for analysis. For example, officials from one county laboratory told us they do not have the time to test samples for cases the county is not going to prosecute.[44]

Technology. Officials from many of the selected state and local and some federal laboratories described having aging or insufficient quantities of technology, which can affect the laboratories’ capacity for emerging street drug analysis. For example, the CBP forward operating laboratory in Nogales, AZ has only one GC-MS. When it stops working or needs maintenance, analysts send samples to another forward operating lab. Officials from some state and local laboratories noted that it can be challenging to get local officials to approve funding to acquire replacement technologies.

Infrastructure. Officials from almost half of the selected state and local laboratories reported challenges relating to aging or otherwise insufficient infrastructure, including not having the physical space to house the technology needed to conduct their work. Some laboratories are in retrofitted structures or active office buildings, which can limit the amount and types of testing that scientists can perform. For example, CBP’s forward operating laboratory at the Los Angeles International Airport is in an office building, which restricts the types and amounts of solvents and the technology that can be housed there. According to the CBP officials, analysts transfer samples that need complex analysis to the field laboratory in Long Beach.[45]

Reference standards. Officials from almost half of the selected state and local laboratories reported challenges related to acquiring reference standards for confirmatory identification of emerging street drugs. Reference standards can be expensive and are generally only available from a few commercial suppliers in the U.S. Officials from some state and local laboratories described having to make judgment calls on which reference standards to acquire due to the cost. Reference standards for emerging street drugs may also not be immediately available for purchase because it can take manufacturers up to a few months to develop a standard for a new chemical.

While Laboratory Officials Described Effective Communication Through Some Channels, Reporting Challenges May Cause Knowledge Gaps

Information sharing is critical for identifying emerging street drugs and emerging drug trends. Scientists at state and local laboratories told us they often turn to state-level working groups or personal connections as the first step in identifying a new, recently detected unknown substance and generally experience no challenges with those connections. Challenges arise when it comes to formal reports and communication between law enforcement and public health entities. There are currently no national reporting standards for state and local laboratories to follow for seized drug analysis, which can lead to underreported or missed data, and public health facilities such as hospitals and medical examiner offices may not have the most up-to-date information about emerging street drugs.

Existing Communication Channels Reported to Be Effective

State-level working groups and personal connections are the primary channel through which forensic scientists learn about emerging street drugs, according to laboratory officials we spoke with. Officials at 13 of the 15 selected state and local laboratories reported no challenges collaborating with other laboratories in their state, and nine remarked that their state working group or other personal connections are among the first points of reference when trying to identify an unknown component in a drug mixture. For example, officials at one local laboratory noted that sharing information in their state working group is a crucial resource for monitoring regional drug trends, exchanging ideas, and ensuring consistent interpretation of controlled substance statutes.

Several regional and national information sharing groups have also had a positive effect in spreading knowledge about emerging street drugs to state and local laboratories, according to officials. Federally sponsored information sharing groups that officials we spoke with from selected state and local laboratories cited as good resources include ONDCP’s regional High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area initiatives and Scientific Trends Open Network Exchange and the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s National Drug Early Warning System. CDC officials also mentioned that monthly public newsletters published by NIST provide timely data to track emerging street drugs and trends.[46] Non-federal information sharing groups include NPS Discovery, run by the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, and the Clandestine Laboratory Investigating Chemists Association.

Information Reporting and Sharing Challenges

Unstandardized reporting. Reporting requirements and testing comprehensiveness vary among drug analysis laboratories, which can lead to missed data or underreporting of emerging street drugs. For example, in some areas, scientists may detect but not officially report substances not covered by the Controlled Substances Act like xylazine, whereas in other areas scientists may note on reports when they observe these substances if they may have an effect on public health. Such variation among laboratory systems can make it challenging to determine if an emerging street drug is a regional or a national threat, especially in the first year or two after a new street drug appears. For example, CDC officials stated that it is difficult to get a sense of which substances are a public health threat and which are outliers, because many local laboratories only test for known drugs or may take time to add new drugs, such as medetomidine, to their tests. Because of this, substances that could be dangerous to a person’s health may go unreported. NIST, through the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science, may be able to help provide guidance to standardize reporting from drug analysis laboratories.[47] The organization approved a standard for report content in forensic toxicology to be added to its registry in 2021 and, as of June 2025, has a proposed draft standard under development entitled “Standard Practice for Reporting Results of the Analysis of Seized Drugs.”[48]

Untimely communication. Timely communication between federal, state, and local laboratories about emerging street drugs can be a challenge. For example, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service officials told us that they find it difficult to get timely, detailed regional data on emerging street drugs because information from state and local bulletins does not always reach their laboratory. In the other direction, officials we spoke to at four state and local laboratories mentioned slow responses from federal agencies for unknown drug identification or confirmation of drug scheduling when an unknown substance is detected. Some state and local laboratory officials we spoke to received timely information from federal agencies due to their pre-existing personal connections. ONDCP’s 2025 Statement of Drug Policy Priorities includes enhancing information sharing and employing rigorous methodologies by modernizing federal, state, and local technologies and systems for data collection and sharing. In addition, through public and private partnerships, the current administration will closely monitor trends and available data to identify and rapidly address emerging threats, according to the statement.[49]

Stakeholders we spoke with pointed to the nonprofit Center for Forensic Science Research and Education and its NPS Discovery program as a resource for rapid information sharing about emerging street drug identification. According to representatives, the nonprofit prioritizes rapid data sharing, which it says it can accomplish due to its collaborative peer review processes and status as a nongovernmental entity. In the 2024 National Drug Control Strategy, ONDCP lists DOJ’s funding of the NPS Discovery program as an example of how the government is meeting its goal of developing methods for identifying emerging drug use trends in real time or near real time. ONDCP also writes in the strategy that DEA has used data from NPS Discovery for emergency scheduling actions.[50]

Limited information sharing between law enforcement and public health. Communication and information sharing between law enforcement and public health entities is sometimes limited, which can leave public health practitioners without the most up-to-date information on emerging street drugs in their region. Law enforcement-based laboratories may consider their findings as law enforcement sensitive, and High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area officials from one region remarked that many local laboratories do not see the need to share data with public health agencies. This reluctance can hinder efforts to provide a comprehensive public health response to drug threats. Toxicological samples can be much more complex than seized drug samples, and, according to representatives from the National Association of Medical Examiners, medical examiners rely on drug chemistry analysts and others to first identify emerging street drugs in seized drug samples to facilitate toxicological analysis. Officials from DEA’s Special Testing and Research Laboratory expressed an interest in developing partnerships with medical examiners’ offices but noted that such a partnership would require toxicological technologies that the DEA laboratory does not currently have. The SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act authorized appropriations for the development of a pilot program to improve coordination between public health laboratories and law enforcement laboratories.[51] The pilot program was not undertaken, however, because funds were not appropriated, according to officials. If this and the other challenges described in this section can be addressed, laboratories could be in a better position to meet the nation’s needs for emerging street drug analysis. However, we are not making recommendations to address these challenges because they are primarily faced by state and local laboratories.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Commerce, Department of Defense, HHS, Department of Homeland Security, DOJ, ONDCP, and the U.S. Postal Service for review and comment. The Department of Defense, HHS, Department of Homeland Security, and DOJ provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Department of Commerce, ONDCP and the U.S. Postal Service did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of Commerce, Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Justice; the Acting Director of National Drug Control Policy; the Postmaster General; and other interested parties. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Karen L. Howard at HowardK@gao.gov or Triana McNeil at McNeilT@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Karen L. Howard, PhD

Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

Triana McNeil

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

This report describes (1) methods and technologies that are available or in development for emerging street drug analysis at federal and selected state and local laboratories and in the field, (2) timelines for developing new methods and technologies, (3) federal grant programs funding the development of new methods and technologies, and (4) federal and selected state and local facilities that analyze emerging street drugs and the key challenges they face.

We define technologies as instrumentation used by scientists for drug analysis, which includes analysis of seized emerging street drugs, drug residues, and toxicological samples. We define methods as including (1) operational methods – operational protocols for routinely used drug analysis technologies, (2) new application methods – protocols for applying existing technologies to drug analysis which had previously not been widely adopted for this purpose, and (3) data processing methods - protocols for processing output data from drug analysis technologies.

To address the objectives, we interviewed federal agency officials (representing seven federal agencies and including 16 components) and requested information related to grant programs available for the development of methods and technologies for analyzing emerging street drugs.[52] We selected these agencies and components based on prior GAO work, our background research, and through conversations with agency officials.

We also selected a non-generalizable group of stakeholders to interview, which covered a range of different perspectives about methods, technologies, and grant programs available for federal, state, local, and private entities to analyze emerging street drugs. We identified relevant interviewees that met certain selection criteria, including:

1. Entities that use or develop technologies and analytical methods for analyzing emerging street drugs in seized drugs and toxicological samples, such as those in academia, private companies including technology manufacturers, and not-for-profit organizations.

2. Entities with knowledge about the time frames for identifying or developing new technologies and analytical methods for analysis of emerging street drugs in seized drugs and toxicological samples.

3. Entities with subject matter expertise about facilities, including laboratories for analyzing emerging street drugs in seized drugs and toxicological samples.

4. Entities, specifically in the federal government, funding the development of methods and technologies for the analysis of emerging street drugs.

5. Entities from academia, private industry, or non-governmental organizations that receive funding for the development of methods and technologies that analyze emerging street drugs.

We compared and supplemented the information obtained from the interviews with information from our review of agency reports and relevant scientific literature.

To address the state and local components of our objectives, we conducted site visits at a non-generalizable sample of drug analysis locations in three regions across the country. We visited regions with a high density of federal, state, local, and other drug testing laboratories. We compared labs that receive federal funding with those that do not, and we compared labs across different locality types (i.e., urban versus rural). These site visits provided perspectives on what methods and technologies laboratories use in the analysis of emerging street drugs, what new substances analysts encountered recently, available federal funding for analysis efforts, and what analysis capabilities exist for drug enforcement purposes in different geographic regions. We considered the following factors for selecting relevant geographic regions for site visits:

1. Each region selected must have a unique “most significant drug threat” or “second most significant drug threat” as described by the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area directors for calendar year 2024.

2. Each region selected must be in a different High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area region.

3. Each region selected must have seven or more federal, state, local, or other laboratories to diversify the types of labs available to visit. We identified state and local laboratories in High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area regions to reach out to for a site visit or interview based on their participation in the National Forensic Laboratory Information System or through information received in interviews.

4. At least one region selected must be at an international border location.

Based on the selection factors mentioned above and on the responses received from our outreach, we conducted site visits or interviewed officials at laboratories (six federal and 15 state and local) in the southwest, mid-Atlantic, and southeast regions of the U.S.[53]

To address the first objective, we also conducted a literature search for relevant articles published in the last 10 years that related to applicable technologies and analytical methodologies. To identify the articles, we conducted searches of databases such as ProQuest and SCOPUS. We also asked stakeholders we interviewed to recommend additional articles. From these sources, we identified 126 journal articles related to methods and technologies for the analysis of emerging street drugs.

To address our third objective, we reviewed relevant grant documentation, including agency solicitations, project proposals and summaries, agency grant program descriptions and annual award totals, and identified publications connected to federal funding. We reviewed the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s (ONDCP) tracking system for federally funded grant programs through usaspending.gov for historical data of federal grants provided during the selected period.[54] We also reviewed public grant archives maintained by federal agencies, like the National Institute of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the National Institutes of Health. In addition, we asked the agencies we interviewed to provide details of any funding awarded during the selected time frame—fiscal years (FY) 2019 through 2024—and we reviewed any additional follow up documents.[55] We compared the grant ID number and titles of the entries we identified to those that were provided to us by agencies to ensure no duplication and that each grant was unique.