VA LEASING

VA Should Systematically Identify and Address Challenges in Its Efforts to Lease Space from Academic Affiliates

Report to the Ranking Member Committee on Veterans' Affairs

U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: David Marroni at marronid@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) leases space from various external parties, including academic affiliates—medical schools and health education programs with an established relationship with VA. According to VA, its local officials leverage these relationships to identify leasing opportunities. In a 2022 law, VA received the authority to noncompetitively award (sole source) a lease to an academic affiliate if certain conditions are met. VA officials said that when sole sourcing a lease, they must still ensure VA receives a fair and reasonable rate. As of June 2025, VA had signed five leases using this authority, according to VA officials.

VA officials and academic affiliate representatives GAO interviewed identified benefits and challenges of entering into leases together, including sole source leases. Benefits they identified included (1) increased collaboration to enhance research; (2) improved veterans’ access to care and more modern facilities; and (3) for sole source leases, potentially quicker access to space. However, VA officials and academic affiliates also identified challenges specific to sole source leases, including (1) issues with VA’s communication about the status of these leases; and (2) difficulties determining how to apply VA’s standard processes when pursuing a more unique project. Interviewees also identified general challenges regardless of lease type, such as limited space availability and the time it takes to obtain VA funding for a project.

VA has taken actions to support implementation of its sole source leasing authority, such as providing training and guidance to VA staff. But VA has not developed and implemented a lessons-learned process to systematically identify and address any challenges. GAO previously reported that a lessons-learned process can be particularly important when an agency is implementing a new approach, and it is helpful to collect lessons learned during implementation rather than waiting until the end. VA officials said they informally review some leases to identify lessons, and they plan to implement a lessons-learned process after 10 sole source leases have been signed. However, it is unclear whether the plan as described aligns with key practices, such as validating lessons with academic affiliates. In addition, waiting until 10 leases have been signed before identifying lessons learned risks compounding existing challenges that VA and academic affiliates have already identified. This includes challenges that have led to confusion or delays for projects that improve veterans’ access to care and support VA research.

Why GAO Did This Study

VA provides health care to over 9 million veterans each year through its medical centers and outpatient clinics. However, VA faces challenges in managing its capital assets, including a significant maintenance backlog and aging infrastructure. To meet its capital asset needs, VA may construct, purchase, or lease medical facilities. VA received the authority to enter into sole source leases with academic affiliates as part of the 2022 Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act.

GAO was asked to review VA’s use of its new leasing authority. This report addresses (1) how VA identifies opportunities to lease from academic affiliates, (2) the benefits and challenges that VA and academic affiliates identified in entering into leases together, and (3) VA’s actions to support implementation of its sole source leasing authority.

GAO reviewed documents and interviewed VA officials. GAO also selected a non-generalizable sample of four academic affiliates with current or potential VA leases, selected to ensure variation in the purpose and status of the academic affiliates’ leases, among other things. For each lease, GAO reviewed available documents and interviewed regional and local VA officials, as well as representatives from the academic affiliate.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that VA develop and implement a lessons-learned process to capture information about its use of sole source leasing with academic affiliates now, rather than waiting until 10 leases have been signed. VA agreed with the recommendation and stated that it plans to implement it.

Abbreviations

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

PACT Act |

Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VHA |

Veterans Health Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 25, 2025

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

Dear Senator Blumenthal:

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates one of the largest health care systems in the country, serving over 9 million veterans each year. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a subcomponent of VA, provides health care services and pursues medical and scientific research in areas that directly affect veterans as well as the public, such as cancer, diabetes, and traumatic brain injuries. To provide these services, VHA relies on its capital assets, including 170 medical centers that offer a wide range of traditional and specialty health care services, and 1,193 outpatient clinics.[1] However, VA faces challenges in managing its capital assets, including a significant maintenance backlog and aging facilities across its system.[2] VA anticipates needing between $166 and $184 billion to cover infrastructure investments over the next 10 years, according to its fiscal year 2025 budget submission.[3] In addition, VA reported in 2023 that the average age of a VA hospital is 60 years, compared with 13 years for private sector hospitals.[4]

To help address its infrastructure needs, VA can construct or purchase facilities or it can lease facilities from other parties, such as private sector entities or academic affiliates. These include universities, medical colleges, and other schools of medicine with which VA has an established relationship. VA’s leased space can include health care facilities, such as hospitals, outpatient clinics, mental health clinics, and research facilities, as well as administrative, warehouse, data center, parking, and regional office space.

In August 2022, the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act was enacted.[5] The PACT Act expanded VA’s health care and benefits to newly eligible categories of veterans. VA has stated that it represents the most significant expansion of veteran benefits and care in more than 3 decades.

The PACT Act also provided VA with leasing flexibility. Specifically, the Act, as amended, authorizes VA to forego the typical competitive procurement process for leases with academic affiliates or covered entities if the leases meet certain requirements and when the VA Secretary determines it is in the interest of the department.[6] Instead, VA can award a lease without competition (sole source) if the lease is for the purpose of providing health care resources to veterans. As of June 2025, VA has used this authority to sign five leases with academic affiliates, according to VA officials.

You asked us to review VA’s use of the PACT Act leasing authority. This report (1) describes how VA identifies opportunities to lease from academic affiliates to address its space needs, (2) describes the benefits and challenges that selected VA officials and academic affiliates identified in entering into leases together, and (3) evaluates VA’s actions to support implementation of the sole source leasing authority.

To address all of our objectives, we reviewed documents and interviewed VA officials. For example, we reviewed VA’s Strategic Plan for Fiscal Year 2022 to 2028, VA’s budget submission for fiscal year 2025, and VA’s Supplement to the General Services Administration’s (GSA) Leasing Desk Guide. We interviewed VA officials from the Office of Construction and Facilities Management and the Office of Asset Enterprise Management.

We also selected a non-generalizable sample of four academic affiliates and examined current and potential leases between the institution and VA to use as illustrative examples.[7] We selected these academic affiliates as examples to ensure variation in location, intended purpose of the lease, status of the lease (i.e., a current lease versus a potential lease that has not yet been signed), and whether the lease uses the PACT Act authority.[8] We focused on VA’s experience leasing with academic affiliates in general as well as on its efforts to use the PACT Act authority, and we note in the report when benefits or challenges are specific to the authority. For each example, we reviewed documents and interviewed VA officials from the Veterans Integrated Services Network, which are VA’s regional networks, and local VA officials from the medical center or health care system, as well as representatives from the academic affiliate. Information obtained from our interviews with VA officials and academic affiliate representatives is not generalizable but provides perspective on VA’s leasing with academic affiliates.

To describe how VA identifies opportunities to lease from academic affiliates, we reviewed VA documents, including leasing policies that were updated in May 2024, and VHA’s Partnering Playbook.

To describe the benefits and challenges that selected VA and academic affiliates identified in entering into leases together, we reviewed available documents associated with our examples. We also interviewed representatives from a veterans’ service organization familiar with how VA leases space.

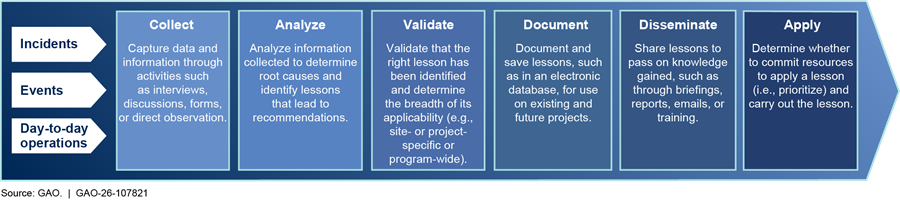

To evaluate VA’s actions to support its implementation of its sole source leasing authority, we compared VA’s actions with practices that we have previously identified as being important for agencies to follow when they are implementing a new approach or process. These practices are collecting data through interviews, analyzing information to identify root causes, validating lessons learned with stakeholders, documenting lessons, disseminating lessons to share knowledge gained, and applying lessons.[9] We also compared VA’s actions with principle 7 of the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, which states that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks.[10] In addition, we compared VA’s actions with the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) Standard for Program Management key practices, including program risk and issue governance.[11]

We conducted this performance audit from September 2024 to October 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Role of VA Offices in Leasing

Within VA, the Office of Construction and Facilities Management oversees lease acquisition through a range of activities. The office develops and issues policies and procedures for VA’s leasing professionals, including those in VA’s regional and local offices.[12] In addition, the office executes major and mid-level leases.[13] This includes overseeing the procurement process and collaborating with local VA officials on evaluating lease proposals and sites to identify the best lease solutions.

In addition, once leases are established, the Office of Construction and Facilities Management is responsible for annually reviewing leases. According to VA officials, the office reviews a random selection of leases for transaction-related elements, such as how the lease was negotiated and any ongoing issues with the lease. The result of these reviews is used to identify training needs and policy changes and to determine if there is regional variation in leasing, according to VA officials.

VHA’s regional offices and medical centers also play a major role in capital asset management. VHA is organized into 18 regional offices called Veterans Integrated Service Networks. Each of these regional offices can include multiple local VA medical centers. In addition to delivering care, these regional offices and medical centers have responsibilities related to capital assets. Each regional office has a Capital Asset Manager and capital planning staff that coordinate and oversee capital planning activities and work with planning officials at the medical center. In addition, based on space needs that are identified department-wide, the medical centers develop and submit proposed capital projects to the regional office. The regional office is responsible for reviewing these projects, working with the medical centers on revisions, and approving the projects for submission to VA’s Strategic Capital Investment Planning process, described in more detail below. In addition, VHA executes minor leases for its facilities.[14]

VA’s Leasing Process

The Strategic Capital Investment Planning process is VA’s mechanism for identifying and prioritizing capital projects, which include construction, non-recurring maintenance, and lease projects. As we have previously reported, the goal of the process is to identify the capital assets needed to address VA’s services and infrastructure gaps, and to demonstrate that all project requests are centrally reviewed in an equitable and consistent way throughout VA.[15]

As part of this process, VA analyzes information from models to identify its space needs (i.e., excesses or deficits in services at the local level). Using this information, local medical center officials are to develop 10-year action plans to address gaps in service, and then develop more detailed plans for capital projects, such as proposed leasing of additional space, that are expected to take place in the first year of the 10-year cycle. These projects are reviewed by regional officials. For example, according to regional officials, they review the medical center’s submission for elements like the cost of the first year’s rent and how the space is categorized. They also review the submission to ensure it identifies how the project will reduce national space gaps and how it fits into VA’s strategic priorities. Once the regional office approves the project, it is submitted to VA. VA validates, scores, and ranks the projects to create a priority list of projects. Budget targets are applied to the priority list to determine which projects will be funded, as we have previously reported.[16]

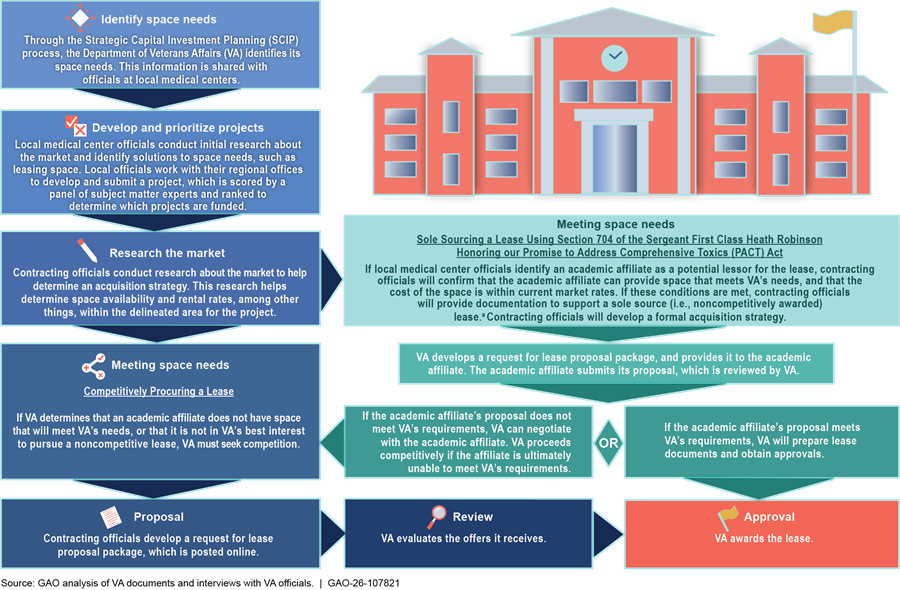

VA then researches the market to determine an acquisition strategy for a lease, according to VA documentation. Generally, an executive agency must employ competitive procedures in the solicitation and awarding of leases unless exceptions apply.[17] However, agencies can award a lease noncompetitively when explicitly permitted by statute. For instance, under Section 704 of the PACT Act (Section 704), VA can award a lease to an academic affiliate or covered entity noncompetitively when the Secretary determines it to be in the best interest of the department and for the purpose of providing health care resources to veterans. Throughout our report, we refer to this as sole sourcing a lease. VA officials told us that sole sourcing a lease with an academic affiliate may help to shorten the length of the leasing process because, for example, VA does not have to evaluate multiple lease offers. VA may select an existing property, or a lessor may construct a new facility to VA’s specifications.

Academic Affiliates

Following World War II, VA developed partnerships with medical schools through which medical students, physician residents, and faculty could help address the health care needs of the large population of returning veterans. VA continues these partnerships today with academic affiliates, which include educational institutions—such as medical schools, dental schools, and nursing schools—that have a relationship with VA medical centers for educational purposes.

VA medical centers partner with nearby academic affiliates to provide clinical training to health profession trainees, while also enhancing the quality of care for veterans.[18] The academic affiliate is responsible for its education programs, while VA provides care to veterans and administers its health care system. An affiliation agreement must be in place before health profession trainees from an affiliate receive training at VA medical centers. For example, the affiliation agreement between the University of Pennsylvania Health System and VA establishes an agreement for the purpose of educating residents and fellows. The University of Pennsylvania has overall responsibility for the educational program, including the program’s curriculum, and educating and assessing resident physicians. VA operates and manages the VA’s facility and collaborates with the academic affiliate to provide an appropriate learning environment. VA may have multiple agreements with one university, each covering different topics. For example, VA may have a lease for space in addition to an agreement regarding the education of medical students.

The Office of Academic Affiliations, an office within VHA, is responsible for supporting VA’s mission of educating and training health care professionals. This office establishes and maintains agreements with academic training programs, such as graduate education medical programs. As of June 2025, VA had agreements with at least 1,450 academic affiliates, according to officials from the Office of Academic Affiliations.[19]

As of June 2025, VA had leases with at least 18 academic affiliates.[20] According to VA, this includes five signed leases with academic affiliates that used VA’s sole source authority under the PACT Act, as of June 2025. In addition, VA identified four leases that it was currently working on that VA officials expected would use sole source leasing under the PACT Act. These sole source leases include space for research and providing clinical services, according to VA officials. See figure 1 for key characteristics of current and potential leases between VA and four selected academic affiliates.

Figure 1: Key Characteristics of Current and Potential Leases Between the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Four Selected Academic Affiliates, Including Use of Section 704 (Noncompetitive Leasing Authority)

Note: In some cases, VA is looking to lease space in the general area of these locations, according to VA documents. In addition, we use the term “potential lease,” because in some instances, VA may be considering leasing space from an academic affiliate but has not yet decided whether to lease space. VA may use other options, apart from leasing, to meet its space needs, such as construction. For the purposes of our report, we refer to subleases as leases.

aThis includes three leases between VA and the University Hospitals Trust, and one lease between VA and the University of Oklahoma. This amount refers to the net usable square footage, based on a spreadsheet VA provided to us.

Local VA Officials Leverage Academic Partnerships to Identify Lease Opportunities, and VA Considers Several Factors When Leasing Space

According to VA officials, VA relies on its local officials to leverage their long-standing relationships with academic affiliates to identify leasing opportunities. Under statute, when VA has an agreement with an academic affiliate, VA must establish an advisory committee to advise on policy matters and the operation of the relevant program. VHA policy operationalizes this by requiring local VA officials and academic affiliates to establish an affiliation partnership council comprised of representatives from both parties for advisory purposes, and to assist in coordinating and planning of the affiliate relationship.

Local VA officials may also meet with academic affiliates on a regular basis. For example, a local official for VA’s Northern California VA Health Care System stated that they attend regular meetings with the academic affiliate (University of California, Davis or UC Davis) that include topics such as the medical school’s strategic plan. The local official added that the opportunity for VA to lease research space in Aggie Square, UC Davis’s new research park, was identified through ongoing discussions they had with UC Davis.

According to VA officials and documentation, VA’s process to lease space from academic affiliates follows its typical leasing process. This process begins with VA identifying a space need and local officials identifying solutions to these space needs, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Overview of Selected Steps in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Process to Lease Space from Academic Affiliates

Note: These are examples of steps taken by VA and do not include all of VA’s efforts during each step. For example, to enter into a multiyear lease, VA must obtain a delegation of leasing authority from the General Services Administration (GSA). In addition, for major leases (defined as a lease with a net average annual rent that is equal to or above $3.961 million in annual unserviced rent in fiscal year 2026), VA must notify the relevant congressional committees and obtain approval of the lease from them. Unserviced rent refers to the base rent, including real estate taxes, insurance, and any amortized build-out. Unserviced rent excludes operating expenses. Lease proposals also require internal VA approvals by various offices at different points during the process.

aAccording to VA documentation, local VA officials obtain approval from the Office of Capital Asset Management and Support. This approval is required for any academic affiliate lease before obtaining GSA delegation of authority.

When submitting a potential lease to the Strategic Capital Investment Planning process, local officials must include certain information, such as how the project fits into VA’s strategic priorities, and a business case justification. In addition, local VA officials from all four selected examples confirmed that they considered many factors when determining whether to enter into a lease with an academic affiliate. These include:

· Cost. Local VA officials we interviewed from all four of our examples said that cost is a factor when determining whether to pursue a lease. Officials noted that even when sole sourcing a lease under the PACT Act, they must ensure the government is receiving a fair and reasonable rate. In addition, VA weighs the cost of leasing versus the cost of construction, as applicable. For instance, a local VA official said that leasing space from UC Davis using sole source leasing under the PACT Act enabled VA to sign a 10-year lease. The total cost of the lease is about $9.2 million in total rent.[21] Constructing a building would have cost VA about $24 million, according to VA officials. The local VA official also said that it is important to continually evaluate leases to ensure that VA is getting a good return on its investment and making the best use of its resources.

· Meeting veterans’ health care needs, including proximity to veterans. Local VA officials from all four of our examples said that they consider meeting veterans’ health care needs when assessing a lease, including, for instance, being located near the current veteran population. For example, local VA officials in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, said that they expect they will see increasing numbers of veterans with toxic exposure at their medical center.[22] They said that while the current Coatesville medical center could provide health care services to these veterans, partnering with the University of Pennsylvania to lease space at a new facility would allow even more veterans to be served.

· Meeting VA’s space needs. Local VA officials from all four of our examples said that meeting VA’s space needs and requirements was a factor. For example, local VA officials in Oklahoma said that they consider whether the space would meet VA standards for clinical care, including building codes. In another example, local VA officials in California said that they consider whether the space helps address a critical need. Specifically, a local VA official noted that the VA facility has a shortage of research space and the lease with UC Davis will allow VA to access specialized research space and expand its research activities.

· Proximity to other VA facilities. Local VA officials from two of our four examples added that VA considers how it can leverage proximity to its other facilities. For example, local VA officials said that the main factor they considered when leasing office space was proximity to VA’s clinical space at the Oklahoma City Health Care System. Additionally, local VA officials in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, said that leasing new space that is located close to the current Coatesville medical center will help ensure economies of scale. For example, if the new facility was located far from the current medical center, it would not be efficient because VA’s warehouse staff would have to drive long distances between the two facilities to deliver supplies.

· Opportunities for collaboration. Local VA officials from all four of our examples identified opportunities for collaboration as a factor. For example, a local VA official in California said that a goal of the leased space is to substantially grow their research program, and that the lease with UC Davis will support collaboration with colocated UC Davis researchers, as discussed later in this report.

· Other factors. VA headquarters officials and local VA officials identified other factors that they may consider when determining whether to pursue a lease with an academic affiliate, including access to other services. For example, if VA is looking to lease space for primary care services but would also benefit from being near an imaging suite, VA would consider whether leasing with an academic affiliate provides access to a nearby imaging suite. Then, VA could refer veterans to an adjacent facility, instead of building its own imaging suite. Similarly, officials said that VA considers whether there are additional reasons for VA to be in that location. For example, if VA is already sending veterans to an academic affiliate’s space for certain health care services, then it may be helpful for VA to lease space at the academic affiliate’s facility. Also, officials said that VA considers how quickly it can get access to the leased space. They added that academic affiliates may be aggressively and rapidly expanding their capital assets. This provides opportunities for VA to engage with the academic affiliate and open new facilities relatively quickly. VA also considers research specialties of each academic affiliate. According to a local VA official, academic affiliates have different specialties, and VA can consider how to leverage these specialties when determining whether to pursue a lease.

According to VA documentation, after VA’s space needs have been identified and approved through the Strategic Capital Investment Planning process, VA researches the market to help determine an acquisition strategy. Contracting officials conduct market research to understand space availability and rental rates, among other things. Contracting officials also have discussions with the academic affiliate to determine if the space the academic affiliate can provide will meet VA’s space needs. For example, according to a contracting official we interviewed, they will confirm the square footage of the space, and ensure it is in a suitable location. Finally, contracting officials confirm that the academic affiliate can provide the space for a price that is fair and reasonable (i.e., the price is within market rates), according to a VA document and a contracting official we interviewed. VA officials said that when it sole sources a lease with an academic affiliate, apart from foregoing competition, all other requirements and approvals apply to the lease.

If the lease can be sole sourced, contracting officials must complete documentation, such as the Justification for Other than Full and Open Competition form, obtain necessary approvals, and provide its lease package to the academic affiliate.[23] The Justification for Other than Full and Open Competition form describes, among other things, VA’s requirements for the space, the research VA conducted to determine if the academic affiliate’s offer was fair and reasonable, and how it determined that entering into a sole source lease is in VA’s best interests. The form also provides guidance on how to confirm whether an academic affiliate is considered an approved academic affiliate using the Office of Academic Affiliations’s website. This documentation is included in VA’s formal acquisition plan. VA must also generally obtain a delegation of leasing authority from GSA to enter into a multiyear lease.[24] However, according to VA, it has a categorical delegation for clinical leases less than 20,000 rentable square feet, which allows VA to execute these leases without a GSA delegation.[25] After receiving any needed GSA delegation of authority, VA provides its request for lease proposal to the academic affiliate, which then provides its proposal to VA.

Contracting officials are to review the academic affiliate’s proposal and confirm that the academic affiliate’s space meets VA’s space and cost requirements, among other things. If the proposal meets those requirements, VA prepares documentation, obtains approvals, and executes the lease. If the proposal does not meet requirements, VA can negotiate with the academic affiliate to try to obtain the academic affiliate’s compliance with its requirements. If negotiations do not result in space and cost that meets VA’s needs, then VA proceeds competitively, according to a VA document.

Selected VA Officials and Academic Affiliate Representatives Identified Multiple Benefits and Challenges of Entering into Leases Together

VA and Academic Affiliates We Interviewed Identified Benefits, Such as Greater Collaboration and Improved Access to Care

Local VA officials and academic affiliate representatives we spoke with identified a range of benefits from entering into leases together. These benefits include enhanced clinical and research collaboration, improved access to care and more modern facilities, and the ability to access these spaces quickly, depending on the lease.

Enhanced Clinical and Research Collaboration

Clinical or teaching collaboration. Local VA officials and three of the four academic affiliate representatives we spoke with noted that clinicians often work for both VA and the academic affiliate. For example, a physician may teach classes at the university in the morning and see VA patients in the afternoon. Local VA officials said that having colocated space furthers such collaboration and allows for more coordinated care for veterans. For example, local VA officials and academic affiliates stated that working in the same facility builds the teaching relationship between academic affiliate faculty and VA, including helping train residents. A veterans service organization noted that veterans can benefit from having access to specialized treatment from academic affiliates at the same facilities where they receive care from VA physicians. These representatives referred to this collaboration as a “natural fit,” since non-VA specialists likely received training at a VA facility and are already part of the community, helping ensure that veterans receive treatment when VA cannot provide direct services.

Research collaboration. Similarly, local VA officials and three of the four academic affiliate representatives we spoke with said that having VA and academic affiliate researchers in the same facility may result in greater research collaboration. For example, an academic affiliate noted that academic faculty can apply for VA research funding and work on topics specific to VA, including cancer and neuroscience-related research. In addition, a local VA official told us that research would likely decline from current levels if the VA does not stay near the academic affiliate, due to the difficulties in commuting across the area. Specifically, the official said that, when surveyed, researchers at the institution said they would likely stop their research work for VA if VA was not located nearby.

Improved Access to Care and More Modern Facilities

Proximity to care. VA prioritizes providing health care in markets where veterans live.[26] Local VA officials and the representatives of all four academic affiliates we spoke with cited proximity to each other as a benefit for their institutions and the populations they serve. According to local VA officials in Pennsylvania, leasing space in an academic affiliate’s building would enable VA to remain in an area with a large veteran population and limit the need for veterans to travel long distances for medical care.

Shared access at a lower cost. VA officials and two academic affiliate representatives told us one of the benefits to VA leasing at an academic affiliate is the ability to provide additional medical care to veterans by sharing and saving resources. For example, local VA officials told us that by leasing at an academic affiliate, VA will be able to access specialized equipment provided by the academic affiliate, including equipment needed for animal research. In addition, VA-leased spaces in buildings owned by academic affiliates may attract enough patients to support additional full-time medical specialists that each organization could not support individually, according to local VA officials. Thus, VA may be able to increase access to different kinds of medical specialists and sub-specialists for veterans. This could also benefit the public, as shared access between VA and the academic affiliate will likely allow both to expand medical services offered to veterans and the public. For example, a memorandum of understanding between VA and the University of Pennsylvania outlined how the two entities intend to develop additional medical care, including outpatient care, at a site in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, that does not have certain hospital services.

In addition, a VA official and representatives from an academic affiliate identified potential cost savings from sharing the same buildings and eliminating the need for additional construction. VA officials said that leasing space from an academic affiliate eliminates the need for VA to maintain or eventually dispose of a building that it owns, potentially saving costs in the long run. Academic affiliate representatives said that prioritizing locations near VA ensures that both organizations have access to enough patients to cover the costs of new facilities. For example, representatives from an academic affiliate said that it may build a small hospital on a property that is near VA’s current facility, and the property will have room for VA to build a retirement community.

Improved medical or research facilities. As we have reported, VA’s facilities are generally older and need to be updated to meet VA’s needs.[27] Local VA officials and representatives from an academic affiliate told us that by leasing sections of an academic affiliate’s building, VA could provide care to veterans in a modern facility and better meet current health care needs. For example, the current design of the VA hospital in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, built in 1929, does not meet modern health care standards because nurses do not have a direct line of sight to patients’ rooms, according to local VA officials. They added that the planned lease between the academic affiliate and VA would potentially remedy this problem by ensuring the new facility includes centrally located nurses’ stations with direct lines of sight into patients’ rooms. Other planned improvements at the new facility include renovating and constructing space to meet VA’s modern standards of care for psychiatric and geriatric care, as well as building small-house neighborhoods to enable better care for retired veterans.

Local VA officials and academic affiliate representatives also told us that leasing allows VA to access modern research space and attract specialists. For example, a local VA official in California told us that leasing space in a state-of-the-art laboratory at UC Davis will provide VA access to space that is not available at the current VA facility (see fig. 3). The official described how the lease will help VA meet its most pressing research space need—pre-clinical research space—which requires laboratory space as well as animal research facilities. It will also allow VA and the academic affiliate to conduct more research using supercomputers to analyze veteran patient data to benefit veterans specifically. The VA official noted that the more modern laboratory made possible by the lease helped VA recruit two experts in cancer and Alzheimer’s research. According to an academic affiliate representative, another potential lease in Charleston, South Carolina, would triple the amount of research space VA occupies to 140,000 square feet of new research space.

Figure 3: Examples of Research Spaces at the University of California, Davis Leased by the Department of Veterans Affairs

Potentially More Timely Access to Space

We have previously reported that it can take up to a decade for VA to build needed facilities and likely takes much longer than construction in the private sector.[28] VA officials told us using sole source leasing authority to work with academic affiliates may shorten the time needed to access the same space. For example, local VA officials who worked on the sole source lease with UC Davis stated that it took roughly 2 years from starting discussions to being ready to move into new, privately developed laboratory space. These officials said for VA to construct similar research space would take between 7 to 10 years, depending on the facility. In addition, local VA officials in Pennsylvania pursuing a sole source lease with the University of Pennsylvania said that they would have had to pursue multiple construction projects to build space to address their space needs in Coatesville and could forgo this lengthy process by leasing from their academic affiliate.

However, determining how much, if any, time is saved using this authority may be difficult, based on information provided by VA and academic affiliate representatives and our review of the examples of potential academic affiliate leases.[29] This is in part because it is too early to estimate how much time is saved using the sole source authority in the PACT Act when compared with competitively bid leases or constructing new VA facilities because, as of June 2025, VA had signed five leases under this authority.

In addition, in at least one case (UC Davis), the academic affiliate had already begun construction of its research campus, and the project would have been completed regardless of whether VA decided to lease some of the research space. Further, as we discuss later, academic affiliate representatives we spoke with said that navigating VA’s leasing processes, including filling out associated forms and completing requirements, may add time to completing even sole source leases.

VA and Academic Affiliates We Interviewed Identified Challenges, Such As Communication Issues

Local VA officials and selected academic affiliate representatives we spoke with identified several challenges to entering into leases together. While some of these challenges may occur regardless of lease type, affiliates and VA officials specifically identified these challenges as affecting their efforts to enter into sole source leases. For example, academic affiliate representatives identified challenges communicating with VA about the status of sole source leases and navigating VA processes to enter into these leases. They also identified challenges with VA’s lengthy approval time frames for leases more broadly, while VA officials told us about constraints on the availability of leased space when working with academic affiliates regardless of the type of lease.

Communicating with VA About Status and Process for Sole Source Leases

All of the academic affiliate representatives told us they experienced challenges during the leasing process because VA did not always communicate the status of proposed sole source leases. They added that it would be helpful for VA to provide additional information about the leasing process. For example, according to an academic affiliate representative, when there were problems with an initial planned location for a sole source lease with VA, VA officials began to look for alternative locations without telling the academic affiliate. VA headquarters officials and a local VA contracting official told us that when attempting to sole source a lease they limit information-sharing in accordance with federal regulations to ensure fairness if the lease is ultimately awarded competitively.[30]

VA officials noted that academic affiliates sometimes have little experience leasing with federal agencies, and that it can require additional time and resources to assist these academic affiliates through the process. For example, one VA official told us academic affiliates sometimes find reviewing and filling out a standard 50-page lease from VA to be a challenge. A different, local VA official said that as a result, VA may have to work with academic affiliates more closely than they would with others, including private developers that are familiar with agency requirements. An academic affiliate representative said they chose developers with experience in federal contracting, as they recognized working with VA may require additional steps.

Navigating VA Processes to Enter into Sole Source Leases

As previously described, VA generally follows many of the same leasing processes when VA is attempting to sole source a lease with academic affiliates under the PACT Act authority as when it is awarding a lease competitively. Academic affiliate representatives told us that VA processes are sometimes difficult to navigate and may add months to finalizing a sole source lease. For example:

· Representatives at one academic affiliate described how, when the leasing process began, VA provided forms for a lease instead of a sublease and that the space requirements in the forms did not match the specific project, adding time to completing the lease. Specifically, the space requirements in the form were for dedicated VA laboratory space (which is traditionally how VA leases laboratory space), but the new laboratory was designed to be an open space in which VA and the affiliate could both work and collaborate. The academic affiliate said they repeatedly submitted the forms and that it was not always clear which VA officials needed to be present in meetings to approve changes to the forms. Local VA officials confirmed that there are no specific templates for shared space leases, and said they used a variety of templates and forms to best match the specifics of the project.

· As part of a different lease, the academic affiliate proposed constructing a building in a floodplain for VA to lease. For 2 years, local VA officials worked through a federal process to mitigate the floodplain risks. However, according to the representative from the academic affiliate, at the end of the process, while local VA officials agreed that the lease should go forward, VA headquarters officials decided to not proceed with the lease.

Representatives from an academic affiliate and VA officials told us that in certain scenarios, VA faced challenges addressing specific issues with the implementation of Section 704 of the PACT Act. For example:

· A representative from an academic affiliate stated VA did not always have a sense of when steps in the process should occur or which steps were next. They added that VA officials seemed to be developing the process for sole sourcing a lease under the PACT Act as they were implementing it.

· A VA official said that additional guidance may be needed to help local VA officials if they are uncertain about whether a potential lessor is a “covered entity.” Section 704 allows VA to sole source certain leases with covered entities. The definition of covered entities includes a broad category—an institution or organization that the Secretary considers appropriate.[31] VA officials said that in instances where it is unclear if a potential lessor is a covered entity, the Office of General Counsel is responsible for deciding.

Lengthy Approval Time Frames with Potential Costs for Academic Affiliates

Local VA officials and academic affiliate representatives told us VA’s process for approving leases and obtaining the previously described applicable approvals needed from Congress adds time to complete the lease process in general, including for sole source leases.[32] In addition, VA officials noted that academic affiliates are responsible for certain costs before the lease begins, which can exacerbate the challenge of long approval time frames. Academic affiliates told us that this additional time, though sometimes expected, makes it difficult to know when the lease will be funded or signed or when the academic affiliate can begin working with VA.

For example, VA and an academic affiliate signed a memorandum of understanding in the summer of 2023, which allowed them to explore the feasibility of jointly working on a plan to renovate or construct new health care facilities and identified a lease as a potential solution. The academic affiliate said that it is difficult to know when VA’s strategic planning process at the local level will be complete so they can begin to work with VA. The academic affiliate representatives said that they can continue to wait for VA to finish its strategic planning process, but that other academic affiliates may not want to wait this long before beginning to work with VA.

VA officials said delays with signed leases may be costly for the academic affiliate, since the academic affiliate funds the new construction and must wait until VA moves in before it receives rent. Some academic affiliates may struggle to finance upfront costs of construction. For example, according to VA officials, the academic affiliate may be responsible for paying the upfront costs of a project for up to 36 months while construction of the leased space is underway. One academic affiliate said they can afford the upfront costs but added that this may not be the case for other academic affiliates. In addition, other potential cost savings may offset these costs for academic affiliates. For example, as previously mentioned, one academic affiliate said VA and the academic affiliate can share parking lots and other infrastructure, eliminating the need to construct these facilities.

Space Constraints

Local VA officials told us that they may face challenges leasing space if academic affiliates do not have enough space to meet VA’s needs, regardless of the type of lease. For example, local VA officials told us that when their lease ends, they may have to move out of an existing leased space that the academic affiliate owns because the space is needed by the university. In addition, local VA officials in another area said that their academic affiliate is facing its own space constraints and would not be able to lease space to VA.

In some cases, VA and the academic affiliate may mitigate this challenge by having the academic affiliate construct or renovate facilities that will then be leased to VA. For example, three of the four academic affiliates either constructed or told us they were willing to construct or renovate spaces for VA to lease. For example:

· At the UC Davis location, the academic affiliate designed the new research facilities, and VA officials worked with the academic affiliate to plan how to use the space to advance VA’s goal of improving veterans’ health through research. According to local VA officials, the space allows both VA and the academic affiliate to better work together.

· The University of Pennsylvania and VA entered into a memorandum of understanding to explore the feasibility of renovating existing space or building new space as part of its leases in downtown Philadelphia, where there is limited available land. According to the memorandum of understanding between VA and the academic affiliate, shared infrastructure allows the academic affiliate to further its research and teaching missions while giving VA more flexibility in how it provides health care.

VA Provided Resources to Support Use of the Sole Source Leasing Authority, but Has Not Systematically Identified and Addressed Challenges

VA has taken some actions to support its implementation of the sole source leasing authority. In January 2023, VA developed training specifically for VA officials about using the PACT Act authority. This includes online training resources to educate local VA contracting and engineering staff about sole source leases. VA officials told us they continue to provide training to staff, including through monthly office hours where local officials can ask questions about leasing, and through training on the PACT Act in June 2023 that was recorded and made available on VA’s internal website.

VA officials also developed and modified existing leasing forms to implement the leasing authority under the PACT Act that include sections meant to provide guidance on leasing with academic affiliates, specifically.

In addition, to help VA better work with academic affiliates and address any challenges, VA officials told us they developed a playbook in January 2023 that includes an overview of different potential challenges that VA and academic affiliates face when entering into leases and strategies for addressing those challenges. For example, VA officials told us they identified the need to further explain the affiliate’s responsibilities under the lease, including how affiliates will need to offer leases at market rates and provide building maintenance and daily operational support. In May 2024, VA also published a supplement to GSA’s Leasing Desk Guide that covers technical and procedural changes to leasing with academic affiliates under the PACT Act authority.

VA also took steps to help academic affiliates navigate the leasing process. However, VA officials and affiliates stated that VA’s initial efforts could have been improved. For example, VA officials told us they provided blank templates of existing leasing forms to academic affiliates to familiarize them with the leasing process. One academic affiliate representative said it would be helpful to make leasing documents publicly available, similar to competitive-bid documents.

Also, academic affiliate representatives we spoke with said they received little or no training regarding leasing with VA, or they did not receive training until after the leasing process was well underway. Academic affiliate representatives we spoke with stated that it would be helpful if VA provided more information about its processes earlier, including how VA determines whether to move forward at each step in the leasing process and better identify which VA officials make these decisions. Academic affiliates also told us they eventually received the information they needed during the leasing process. VA officials agreed that in some instances it may be possible to provide more information earlier to academic affiliates, but said they share limited information to ensure that academic affiliates do not have a competitive advantage if VA decides to competitively award the lease and to meet federal acquisition requirements. VA officials also told us that an interdisciplinary team, including contracting professionals, meets with academic affiliates early in the process to explain how VA’s leasing process works.

We have previously reported that adopting a lessons-learned process can be particularly important when an agency is implementing a new approach, as VA is now doing by entering into sole source leases with academic affiliates under the PACT Act. A lessons-learned process is a systematic means for agencies to learn from specific events or day-to-day operations and make decisions about when and how to use that knowledge to change behavior. It can also help agencies identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving its objectives, a key part of federal internal controls.[33] We have also reported that collecting lessons learned throughout the course of an event, rather than just at the end, can help to ensure that lessons learned are captured as close as possible to the learning opportunity.[34] Similarly, key practices state that risks and issues should be escalated in a timely manner or challenges that internal and external program stakeholders face may be compounded.[35]

In prior work, we identified six key practices for a lessons-learned process (see fig. 4).[36] These key practices also align with the Project Management Institute’s practices for program management, which include the need to capture lessons learned to improve program oversight.[37]

Note: This graphic was initially published in 2020 in GAO, VA Construction: VA Should Enhance the Lessons-Learned Process for Its Real-Property Donation Pilot Program, GAO‑21‑133 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 10, 2020 and was based on an analysis of prior reports (GAO, Telecommunications: GSA Needs to Share and Prioritize Lessons Learned to Avoid Future Transition Delays, GAO‑14‑63 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 5, 2013), GAO, Federal Real Property Security: Interagency Security Committee Should Implement A Lessons-Learned Process, GAO‑12‑901 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2012), and GAO, NASA: Better Mechanisms Needed for Sharing Lessons Learned, GAO‑02‑195 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 30, 2002)) and a Center for Army Lessons Learned report: Establishing a Lessons Learned Program: Observations, Insights, and Lessons. See GAO‑21‑133.

VA has not implemented a lessons-learned process for its efforts to enter into sole source leases with academic affiliates under the PACT Act. Local VA officials and VA headquarters officials stated that developing lessons learned for these efforts would be helpful. VA headquarters officials told us they informally review major leases for potential lessons, including leases that were not awarded. They also stated that they intend to implement a lessons-learned process after they sign 10 sole-source leases with academic affiliates, to ensure sufficient sampling. According to VA officials, such a lessons-learned process would focus on improving leasing time frames. Specifically, once VA signs the five additional sole source leases, VA officials said they will interview internal VA stakeholders and compare timelines for the 10 leases with VA’s typical timelines, to identify opportunities to lessen the time it takes for leases to be signed.

VA has not provided documentation of its planned lessons-learned process, and it is unclear whether the process will include the six key practices described above, such as validating lessons learned with specific stakeholders. Many of the challenges with potential leases between VA and academic affiliates we identified were based on discussions with academic affiliate representatives. If VA does not gather information from external stakeholders, such as academic affiliate representatives, and validate any lessons learned it identifies with them, it will be difficult to determine if VA has identified the right lessons and how they should be applied.

In addition, if VA waits to implement a lessons-learned process, it may not quickly identify and address challenges associated with its sole source leasing authority. As of June 2025, VA officials told us they had signed five sole source leases with academic affiliates, and it was unknown how long it could take to sign 10 leases. In addition, as mentioned previously, some academic affiliate representatives have already identified challenges that added time to the leasing process, including filling out forms and navigating forms when they did not match the specific project. VA identified some challenges in its initial efforts to use the sole source leasing authority and took steps to address them, such as providing more information on its leasing process to academic affiliates. However, implementing a lessons-learned process now will enable VA to identify lessons learned on an ongoing and systematic basis. By waiting until 10 leases are signed, VA may miss opportunities to identify lessons learned from additional sole source leases that could improve the process for entering into leases with academic affiliates. Without these improvements, there may be fewer signed leases.

VA’s use of this leasing authority is occurring at the local level, making it possible that VA will not have a holistic and real-time view of challenges or best practices that arise during the early stages of the process. Two local VA officials noted that successful partnerships depend in part on relationships between local VA medical center officials and academic affiliate representatives, which can change as personnel change. Without a lessons-learned process that collects and disseminates validated information across VA’s regions early on for sole source leases, VA officials may not have visibility into the experiences of other regions that are more successful. Further, by implementing a lessons-learned process now, the experiences of successful regions can be applied in real time to subsequent leases, and challenges will be addressed in a timely manner, rather than compounding.

While VA’s Office of Construction and Facilities Management responds to questions and collects information from local officials regarding the leasing process, it does not distill and validate information on lessons learned and disseminate this information across VA for sole source leases. Local VA officials told us that some regions meet regularly to discuss their experiences in establishing leases with academic affiliates, including leases that rely on the PACT Act’s sole sourcing authority. These same officials said implementing a lessons-learned process across VA with an associated toolkit for leasing with academic affiliates specifically would be helpful.

Conclusions

VA faces challenges in managing the capital assets it uses to provide care to veterans, including a significant infrastructure maintenance backlog and aging facilities across its system. In 2022, the PACT Act provided VA the authority to lease space from academic affiliates without using the typical competitive leasing process if the lease is for the purpose of providing health care resources to veterans. VA has taken some steps, such as providing training, to help its local officials use the sole source leasing authority. However, VA has not implemented a lessons-learned process to gather lessons specifically on its use of sole sourcing leases with academic affiliates, and it does not plan to do so until 10 such leases have been signed. VA did not have documentation of its planned lessons-learned process, and it is unclear whether the process will include the key practices described above, such as validating lessons learned with specific stakeholders. Further, as of June 2025, VA officials said that there are four sole source leases that VA is working on, in addition to the five sole source leases that have been signed. By waiting until 10 leases are signed to implement a lessons-learned process, VA could miss the opportunity to obtain and apply valuable insights into how it can more effectively use its leasing authority to address critical infrastructure needs.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of VA should develop and implement a lessons-learned process that aligns with key practices identified in GAO’s prior work to capture information about its efforts to use sole source leasing with academic affiliates now, rather than waiting until 10 leases have been signed. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to VA for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix I, VA agreed with our recommendation. VA stated that it will develop a lessons-learned process, using the six key practices identified in our prior work, for the five sole source leases with academic affiliates. VA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at marronid@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Sincerely,

David Marroni

Director, Physical Infrastructure

GAO Contact

David Marroni, marronid@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Crystal Huggins (Assistant Director), Amy Suntoke (Analyst in Charge), Melissa Bodeau, Laura Bonomini, Melanie Diemel, Elizabeth Dretsch, Deitra H. Lee, Alicia Loucks, Mark Luth, Todd Schartung, and Michael Zose made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In addition, veterans can receive care from community providers when they face certain challenges in accessing care at VA medical centers. For additional information, see GAO, Veterans Community Care Program: VA Needs to Strengthen Contract Oversight, GAO‑24‑106390 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 21, 2024).

[2]We have previously reported on VA’s capital assets and capital planning efforts. See, for example, GAO, VA Real Property: Improvements in Facility Planning Needed to Ensure VA Meets Changes in Veterans’ Needs and Expectations, GAO‑19‑440 (Washington, D.C.: June 13, 2019).

[3]This estimate includes activation costs. Activation is the process for bringing a new facility into full operation, such as purchasing and installing furniture and medical equipment and hiring staff.

[4]Department of Veterans Affairs, Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Submission: Budget in Brief (March 2023).

[5]Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-168, 136 Stat. 1759.

[6]Under Section 704 of the PACT Act, academic affiliates include medical schools, medical centers, academic health centers, and hospitals. According to VA, it interprets academic affiliate to encompass the institutions and organizations listed in the statute and, more broadly, includes other types of institutions involved in health professions education. Covered entities include state, local, or municipal governments and public and nonprofit agencies that own land controlled by an academic affiliate. Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-168 § 704, 136 Stat. 1759, 1799 (codified at 38 U.S.C § 8103).

[7]We use the term “potential lease,” because in some instances, VA may be considering leasing space from an academic affiliate but has not decided to lease space. VA may use other options, apart from leasing, to meet its space needs. In addition, for the purposes of this report, we refer to subleases as leases.

[8]For our four examples, we selected three potential sole source leases between an academic affiliate and VA: (1) the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the Coatesville, Pennsylvania, VA Medical Center; (2) the Medical University of South Carolina and the Charleston, South Carolina, VA Medical Center; and (3) the University of California, Davis and the Northern California VA Health Care System. We also included an academic affiliate with existing VA leases that did not rely on the sole source authority under the PACT ACT: the University of Oklahoma and the University Hospitals Trust. We considered the University of Oklahoma and the University Hospitals Trust that owns the property to be the same affiliate for the purposes of our report. The University of California, Davis and VA signed the lease that used the sole source authority in the PACT Act during our review.

[9]See GAO, VA Construction: VA Should Enhance the Lessons-Learned Process for Its Real-Property Donation Pilot Program, GAO‑21‑133 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 10, 2020) for an overview of how these key practices were identified and developed.

[10]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑25‑107721 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2025).

[11]The Project Management Institute is a not-for-profit association that, among other things, provides standards for managing various aspects of projects, programs, and portfolios. These standards are used worldwide and provide guidance on how to manage various aspects of projects, programs, and portfolios. For the specific program management standards for oversight that include capturing lessons learned see Project Management Institute, Inc., The Standard for Program Management, Fifth Edition (2024).

[12]Leases for VA medical facilities require additional approvals. VA must first receive a delegation of authority from the General Services Administration (GSA). VA maintains independent leasing authority to enter into a lease for medical space the Secretary deems necessary. 38 U.S.C. § 8103. However, agencies are prohibited from contracting for money before Congress provides funding or the agency is otherwise authorized by law. 31 U.S.C. § 1341. Congressional funding is typically provided on a yearly basis, and VA lacks the necessary statutory authorization to allow VA to undertake the multiyear contracts used for leases with academic affiliates. GSA has the explicit authority to enter into multiyear leases and can delegate this authority to the VA. 40 U.S.C. § 585. If the proposed lease exceeds a certain statutory threshold, it must be approved by GSA and subsequently by relevant Congressional committees. 38 U.S.C. § 8104. GSA may adjust this threshold annually to reflect changes in construction costs. 40 U.S.C. § 3307(h).

[13]Major leases are those with a net average annual rent that is equal to or above the prospectus level determined by GSA. In fiscal year 2026, the prospectus level was $3.961 million. Mid-level leases are leases that are between $1 million and the GSA prospectus level. Prospectus-level leases refer to proposed lease projects with a net average annual rent equal to or over a statutorily specified dollar threshold and for which VA is statutorily required to submit a prospectus for congressional funding approval prior to appropriations being made for such projects. 40 U.S.C. § 3307; 38 U.S.C. § 8104.

[14]Minor leases are leases that are $1 million or less in annual unserviced rent. Unserviced rent refers to the base rent, including real estate taxes, insurance, and any amortized build-out. Unserviced rent excludes operating expenses. See Dep’t of Veterans Affs., Directive 7815, Acquisition of Real Property by Lease and by Assignment from General Services Administration, (Jan. 20, 2012).

[15]GAO, VA Real Property: VA Should Improve Its Efforts to Align Facilities with Veterans’ Needs, GAO‑17‑349 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 5, 2017).

[16]For additional information about VA’s Strategic Capital Investment Planning process, see GAO‑17‑349.

[17]41 U.S.C. § 3301.

[18]If VA is sponsoring a program, VA can send its trainees to the academic affiliate for training. If an academic affiliate is sponsoring a program, the academic affiliate can send its trainees to VA for training. See Dep’t. of Veterans Affs., Directive 1400.03, Educational Relationships, (Feb. 23, 2022).

[19]According to VA officials, this number can vary. VA officials stated that academic affiliates managed by the Office of Academic Affiliations at the national level have approved agreements. However, they also noted that academic affiliates may have affiliation agreements that are tracked by local medical centers that the Office of Academic Affiliations would not be aware of.

[20]We identified these academic affiliates by reviewing VHA’s list of operational leases that was provided to us in July 2025. Because the list does not specifically identify leases between VA and academic affiliates, and VA officials told us they do not track which leases are academic affiliate leases, we reviewed the lessor/landlord business name and generally considered the lessor to be an academic affiliate when the name contained “university” or “college.” We also identified academic affiliates by reviewing VA’s list of sole source leases.

[21]According to the lease, this amount includes rents for the shell, operating costs, established tenant improvements, and parking.

[22]The PACT Act expanded benefits and health care for veterans exposed to toxic substances. According to an August 2024 press release, nearly 740,000 veterans enrolled in VA health care since August 2022, representing a 33-percent increase over the previous 2-year period. As we have previously reported, service members and veterans at the end of the 1991 Gulf War attributed symptoms and illnesses to toxic exposures, such as smoke from oil-well fires. Service members and veterans deployed after September 11th to Afghanistan and Iraq also reported health concerns from toxic exposures produced by open-air burn pits. See GAO, Military Health Care: DOD and VA Could Benefit from More Information on Staff Use of Military Toxic Exposure Records, GAO‑24‑106423 (Washington, D.C.: May 23, 2024).

[23]Justifications for other than full and open competition are required by regulation. 48 C.F.R. § 6.303-1. For leases that are above the Simplified Lease Acquisition Threshold, contracting officials complete the Justification for Other than Full and Open Competition form. For leases that are at or below this threshold, contracting officials complete the Lack of Competition Memo to File. Effective October 2025, the simplified lease acquisition threshold will increase from $250,000 net average annual rent to $350,000, to adjust for inflation.

[24]GSA is the main landlord and leasing agent for the federal government and is authorized to acquire space from private building owners for use by federal tenant agencies. GSA may delegate its leasing authority to other agencies. While VA has some leasing authority by statute, it needs GSA delegation of leasing authority to enter multi-year lease contracts.

[25]A categorical delegation is a standing delegation which allows VA to acquire an eligible type of space without an additional GSA delegation.

[26]We previously reported on efforts by VA to modernize and realign its infrastructure, including how it decides where to place facilities. See, for example, GAO, VA Health Care: Improved Data, Planning and Communication Needed for Infrastructure Modernization and Realignment, GAO‑23‑106001 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 20, 2023).

[28]GAO, VA Health Care Facilities: Leveraging Partnerships to Address Capital Investment Needs, GAO‑22‑106017 (Washington, D.C.; May 12, 2022); VA Construction: Additional Actions Needed to Decrease Delays and Lower Costs of Major Medical-Facility Projects, GAO‑13‑302 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 4, 2013). We also found delays continued in specific medical facility construction projects. See GAO, VA Construction: Actions Taken to Improve Denver Medical Center and Other Large Projects’ Cost Estimates and Schedules, GAO‑18‑329T (Washington, D.C: Jan. 17, 2018).

[29]We previously found that VA does not always track leases to identify how much it benefits from leases. See GAO, VA Real Property: Leasing Can Provide Flexibility to Meet Needs, but VA Should Demonstrate the Benefits, GAO‑16‑619 (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2016).

[30]Regulations govern exchanges between contracting agencies and offerors through stages of the leasing process and prohibit the disclosure of protected bid or proposal information which could compromise the fairness of the process.

[31]Covered entities also includes state, local, or municipal governments and public and nonprofit agencies that own property controlled by an academic affiliate. Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-168, 136 Stat. 1799 (2022) (codified at 38 U.S.C § 8103).

[32]Whenever VA submits a request for funding of a major lease, for instance through a fiscal year’s budget request, it must submit a prospectus including specific information on the proposed lease. By statute, Congress cannot appropriate funds, and VA may generally not obligate or expend funds, unless the relevant committees have approved the major lease. 38 U.S.C. § 8104. Major leases are leases with a net average annual rent that is equal to or above $3.961 million in annual unserviced rent in fiscal year 2026.

[34]GAO, Customs and Border Protection: Actions Needed to Enhance Acquisition Management and Knowledge Sharing, GAO‑23‑105472 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 25, 2023).

[35]Project Management Institute, Inc., The Standard for Program Management, Fifth Edition (2024).

[36]See GAO‑21‑133. For example, we identified six lessons-learned key practices in GAO, Telecommunications: GSA Needs to Share and Prioritize Lessons Learned to Avoid Future Transition Delays, GAO‑14‑63 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 5, 2013). We identified and refined these practices in several prior reports. These identified key practices were based on lessons-learned practices we had identified in GAO, Federal Real Property Security: Interagency Security Committee Should Implement a Lessons-Learned Process, GAO‑12‑901 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2012); NASA: Better Mechanisms Needed for Sharing Lessons Learned, GAO‑02‑195 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 30, 2002); and a report from the Center for Army Lessons Learned.

[37]Project Management Institute, Inc., The Standard for Program Management, Fifth Edition (2024).