INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Information on Draft Guidance to Assert Government Rights Based on Price

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Candice N. Wright at wrightc@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

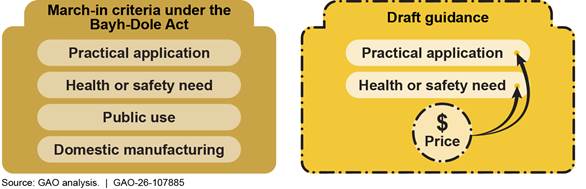

Under the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, federal agencies can, in certain circumstances, exercise the authority known as march-in rights when an invention that arose from federally funded research is involved. March-in-rights entail an agency requiring a recipient of its funding to issue a license to a third party to develop the invention. Agencies have never exercised march-in rights. In December 2023, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published draft guidance that sought to clarify when agencies could exercise this authority. It proposed using the price of a product resulting from a federally funded invention as a factor for exercising march-in rights. According to the guidance, price could be used under two of the four statutory criteria: practical application and health or safety need (see figure).

The draft guidance was developed through a NIST-led interagency process. As of December 2025, NIST did not have a timeline for finalizing the guidance, citing a lack of interagency consensus.

Among the 51,762 public comments on the draft guidance, more than 47,000 comments (about 91 percent) expressed support for the draft guidance, with the remainder expressing opposition. Most comments in favor of the guidance expressed concern about high prescription drug prices and support for using march-in rights to lower them. Comments opposing the guidance—including all comments submitted by universities—raised concerns about potential adverse effects, such as reducing universities’ ability to license inventions and businesses’ ability to attract investment to develop the inventions into products.

Because march-in rights have never been exercised, it is only possible to discuss hypothetical impacts of implementing the draft guidance. A federal agency could exercise march-in rights based on product price only if a product resulting from a federally funded invention has an unexpired patent subject to Bayh-Dole. Therefore, the potential for march-in is higher for technologies with a high volume of patenting activity arising from federally funded research, such as pharmaceuticals, computer technology, and electrical machinery. Although most public comments on the draft guidance expressed support for using march-in rights to lower drug prices, studies estimate that march-in based on price would likely affect a small number of drugs. This is because most drugs have patents that are not subject to Bayh-Dole.

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal agencies fund universities and other organizations to conduct research, which can lead to new inventions. Under the Bayh-Dole Act, recipients of federal funding can retain patent rights to the inventions and license them to other parties. To protect public interest in these inventions, the act allows federal agencies to retain certain rights, including march-in rights. These permit an agency to require a recipient to issue a license to a third party, when the circumstances meet at least one of four criteria specified in the act. If the recipient refuses, the agency itself can grant a license.

Agencies can initiate march-in proceedings on their own or in response to requests from external parties. Since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, agencies have received about a dozen march-in requests; most of these addressed lowering the price of drugs or other medical technologies. For all the requests, agencies declined to exercise march-in rights.

GAO was asked to review development of NIST’s draft guidance and its potential impacts. This report examines: (1) key elements of the draft guidance and the NIST-led interagency process for developing it; (2) stakeholder views on the draft guidance, as reflected in public comments; and (3) available information about the potential impacts of exercising march-in rights based on price.

GAO reviewed applicable laws and regulations, analyzed public comments and patent data, reviewed studies estimating how many drugs could be affected by exercising march-in rights based on price, and interviewed agency officials.

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

DOE Department of Energy

DOT Department of Transportation

draft guidance Draft

Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering

the Exercise of March-In Rights

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NIH National Institutes of Health

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

RFI request for information

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 18, 2026

Congressional Requesters

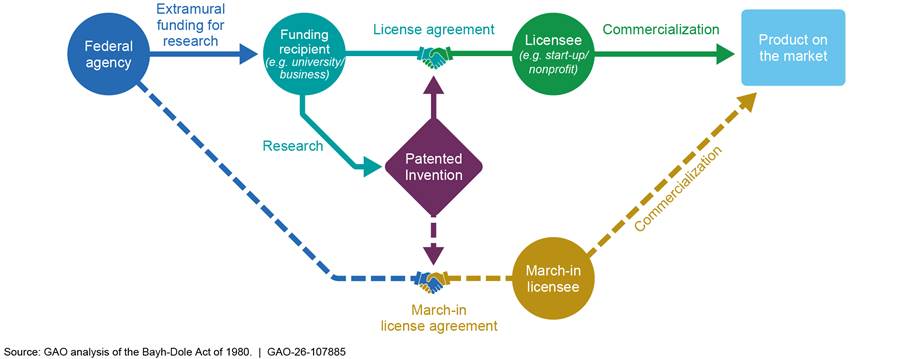

The federal government funds universities, businesses, and other organizations to conduct research, which can lead to new inventions. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 promotes the commercialization of these inventions into marketable products by allowing recipients of federal funding to retain patent rights to the inventions, among other things.[1] The recipients may commercialize the inventions themselves or license the patent(s) on those inventions to industry partners for commercialization.

At the same time, the act provides the government with rights intended to ensure that the public benefits from federal research investments, including certain use rights to federally funded inventions. It also provides federal agencies the authority known as “march-in rights.” Through march-in rights, a federal agency can require funding recipients to grant additional patent licenses—authorizing third parties to use the patents for inventions developed with the agency’s funding—or issue such licenses itself.

In December 2023, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published a request for information (RFI) on the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights.[2] NIST drafted the guidance in collaboration with the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole. According to the draft guidance, the price of a commercialized product resulting from a federally funded invention can be an appropriate consideration in a march-in determination. As stated in the draft guidance, the guidance would be nonbinding if it is finalized. The RFI invited public comment on factors a federal agency might consider when deciding whether to exercise march-in, including price.

You asked us to review issues related to the development of the draft guidance and its potential impacts. This report examines: (1) key elements of the draft guidance and the NIST-led interagency process for developing it; (2) stakeholder views, as reflected in public comments, on potential positive and negative impacts of the draft guidance; and (3) available information about the potential impacts of the draft guidance on the commercialization of federally funded inventions in different industries.

For all three objectives, we reviewed applicable laws, regulations, and the draft guidance. We analyzed public comments submitted in response to the NIST RFI and public data on patents developed with federal funding. We assessed the reliability of the patent data by reviewing related documentation and reviewing the data for errors and omissions, among other things. We determined the data to be reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

We obtained information about the drafting of the guidance from NIST, the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Transportation (DOT), as well as a range of stakeholders who submitted public comments supporting and opposing the draft guidance. (See app. I for more details about our scope and methodology.)

We conducted this performance audit from October 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Funding for Research

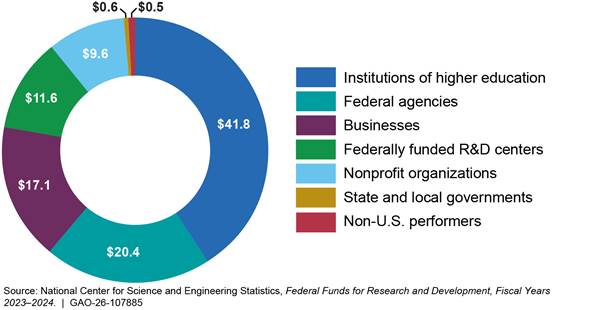

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, in fiscal year 2023, federal agencies obligated about $102 billion for basic and applied research.[3] The largest share of these obligations, about $42 billion, went to universities and other institutions of higher education (see fig. 1). Businesses, both small and large, also accounted for a significant share of this funding, receiving about $17 billion in federal obligations.

Figure 1: Federal Obligations for Basic and Applied Research in Fiscal Year 2023 by Performer of Research, in Billions

Federally funded research can lead to patentable inventions.[4] A patent is an exclusive right granted for a fixed period to an inventor.[5] A product developed from a federally funded invention can be associated with multiple patents.

Research conducted at universities generates a significant number of inventions and patents. The nonprofit association AUTM estimates that from 1996 through 2020, university-based scientific research, including federally funded research, resulted in more than 495,000 inventions and 126,000 U.S. patents.[6]

March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980

To promote the commercialization of federally funded inventions, the Bayh-Dole Act created a legal framework for permitting ownership of patent rights to “subject inventions” that arose from federally funded research and development (R&D).[7] Recipients of federal funding—the act refers to them as “contractors”—may elect to retain the patent rights to inventions made with such funding and may commercialize the inventions on their own or license the patent(s) to third parties for commercialization.[8] They are required to include in the patent application and issued patent a statement disclosing that the invention was developed with federal support.[9]

Under the act, the government retains certain rights to federally funded inventions. One of them is the authority to require the funding recipient, patent owner, or exclusive licensee of a subject invention to grant a license to a responsible applicant or applicants, upon terms that are reasonable under the circumstances, if one of the four statutory criteria is met. If the funding recipient, patent owner, or exclusive licensee refuses such a request, the act allows the government to grant a license itself. This authority, known as march-in rights, rests with the federal agency that funded the research leading to the subject invention (see fig. 2). Expiration of a patent eliminates the need for an agency to march in, because when the patent expires, the invention enters the public domain, and any person or company can use it without a license from the patent owner.[10]

Note: The federal agency may require the funding recipient, patent owner, or exclusive licensee of a subject invention to grant a license to a responsible applicant or applicants. If refused, the agency can issue the license itself.

|

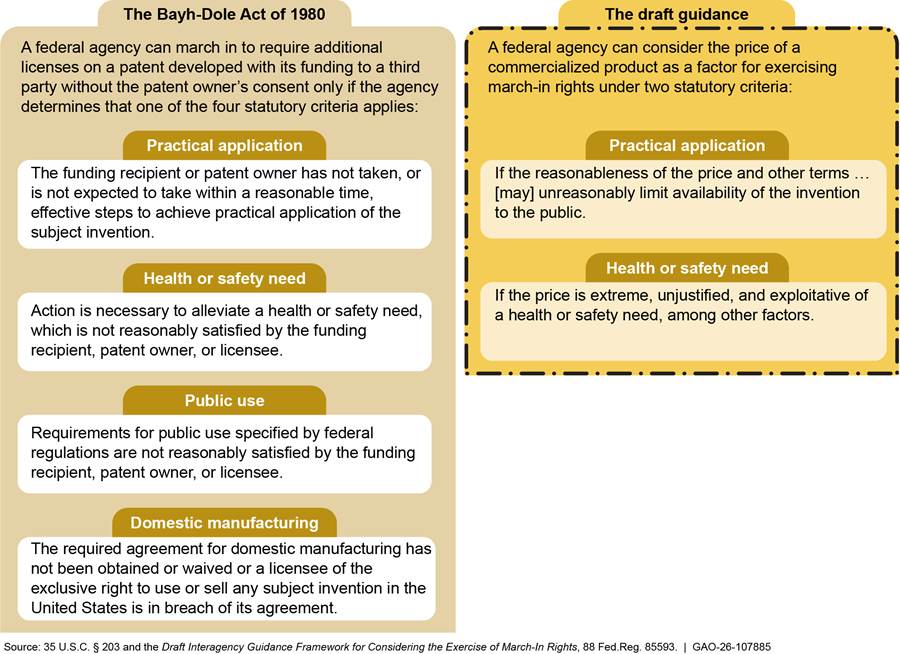

Statutory Criteria for Exercising March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 A federal agency can “march in” to require additional licenses on a patent developed with its funding to a third party without the patent owner’s consent only if the agency determines that at least one of the four statutory criteria applies: · The funding recipient or patent owner has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention. · Action is necessary to alleviate a health or safety need, which is not reasonably satisfied by the funding recipient, patent owner, or licensee. · Requirements for public use specified by federal regulations are not reasonably satisfied by the funding recipient, patent owner, or licensee. · The required agreement for domestic manufacturing has not been obtained or waived or a licensee of the exclusive right to use or sell any subject invention in the United States is in breach of its agreement. Source: 35 U.S.C. § 203. | GAO‑26‑107885 |

An exercise of march-in rights is an arduous process involving, among other things, establishing the facts of the invention at issue and following the required procedures with respect to the patent holder. An agency wishing to exercise march-in rights can only do so if at least one of the four criteria described in the statute is satisfied. The criteria address practical application, a health or safety need, public use, and domestic manufacturing (see text box).[11]

As stated in the draft guidance, the federal government has never exercised march-in rights, which has at least two implications. First, the application of march-in rights has not been tested in courts, which means that march-in provisions have never undergone judicial review that could clarify their interpretation. Second, since there is no empirical evidence for evaluating the impact of exercising march-in rights on licensing and commercialization activities, it is possible to discuss only potential or hypothetical impacts. Nevertheless, multiple stakeholders told us that march-in authority is valuable because of the leverage it provides to promote commercialization of federally funded inventions.[12]

NIST Draft Guidance on March-In Rights

NIST is responsible for promulgating government-wide regulations for the Bayh-Dole Act.[13] It also convenes the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole, which, according to NIST, reviews issues relating to extramural research activities within the field of technology transfer and works to create consensus and policy across agencies.[14] The working group includes representatives from multiple federal agencies that fund R&D, including the largest funders.

NIST drafted the guidance in collaboration with a subcommittee of the working group, and it was then reviewed and amended by the full working group. The draft guidance and the RFI were published in December 2023. In response to the RFI, NIST received more than 51,000 comments during a 60-day public comment period, which ended in February 2024.

March-In Petitions and Drug Pricing

Under the Bayh-Dole Act, agencies can initiate march-in proceedings on their own. Agencies may also receive requests to march in from external parties (commonly referred to as petitions). Prior to the release of the draft guidance, the public debate about march-in rights had largely revolved around whether the federal government could use them to lower the price of drugs developed with federal funding. This could be for several reasons:

· Drug prices are generally higher in the United States than in other countries. According to a study commissioned by HHS, in 2022, U.S. prices across all drugs (brand names and generics) were nearly 2.78 times the prices in the comparison countries, and U.S. prices for brand name drugs were at least 3.22 times the prices in the comparison countries.[15] The study also found that the gap was widening over time as U.S. drug prices grew faster than drug prices in other countries and the mix of drugs changed.

· Drugs are typically patented, which sets the pharmaceutical industry apart because patenting of new products varies by industry, and some industries rely more on other forms of intellectual property to protect their products.

· Biomedical research accounts for a significant share of federal research funding. According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) alone provided $44 billion—about 43 percent of all federal funding for research—in fiscal year 2023.

Since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, federal agencies received about a dozen march-in petitions but declined to exercise this authority. According to publicly available information, most of the petitions were addressed to HHS and requested the agency to exercise march-in rights to lower the prices of drugs or other medical technologies that could be linked to NIH-funded research.[16]

Several petitions submitted to HHS and DOD between 2016 and 2021 involved Xtandi, a drug for treating prostate cancer that could cost as much as $178,000 per year when not covered by health insurance. According to the petitions, during this period there were three patents for the drug resulting from research at the University of California under grants from HHS and DOD. The petitions argued that the drug’s high price in the United States violated the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in provision to make federally funded inventions available on “reasonable terms.” HHS and DOD declined to exercise march-in rights in response to the petitions. HHS, in the decision letter from March 2023 responding to a 2021 petition, stated the drug was widely available to the public on the market.[17] HHS also stated it did not believe the use of march-in authority would be an effective means for lowering the drug’s price given the remaining patent life and the lengthy march-in administrative proceedings.[18]

NIST Has No Timeline for Finalizing Draft Guidance That Proposed Price as a Factor for Exercising March-In Rights

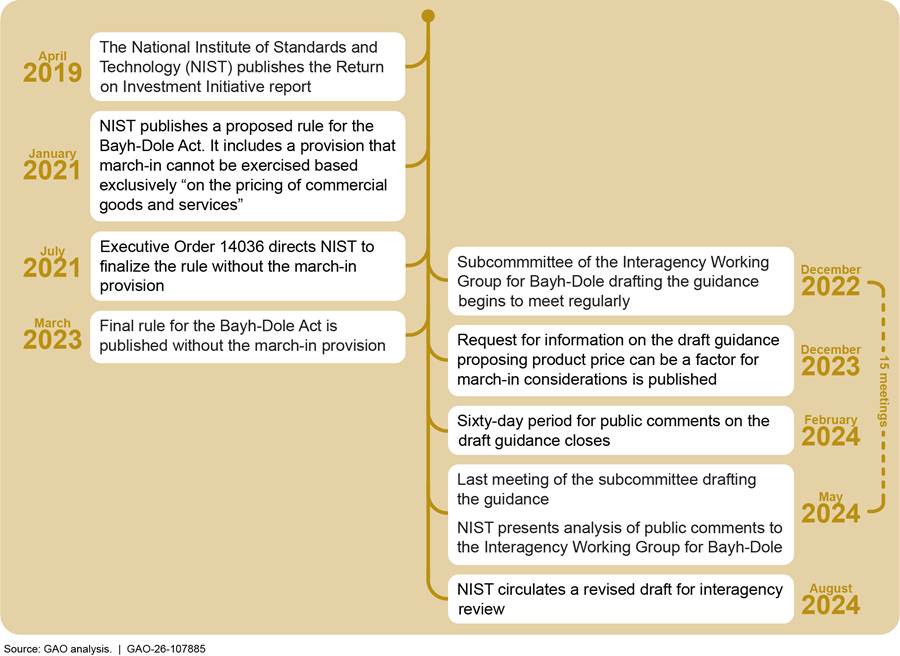

NIST’s draft guidance was developed with multiple objectives in mind, including to provide clear guidance on the prerequisites for exercising march-in rights and factors a federal agency would consider in determining whether to march in. According to the draft guidance, agencies may consider the price of a product resulting from a federally funded invention as a factor for exercising march-in rights under two statutory criteria: practical application and health or safety need. The draft guidance was developed through a NIST-led interagency process between December 2022 and December 2023. NIST sought and reviewed public comments on it between December 2023 and May 2024. As of December 2025, NIST had not finalized the draft guidance and did not have a timeline for doing so, according to NIST officials.

Draft Guidance Proposed Price as a Factor for Exercising March-In Rights

Under the Bayh-Dole Act, the authority to exercise march-in rights rests with the agency that funded the research leading to the invention under consideration. One stated goal of the draft guidance is to ensure a consistent and predictable application of the law by agencies considering an exercise of march-in rights. According to NIST, the guidance would be voluntary.

Another stated goal was to provide clear guidance on the prerequisites for exercising march-in, facts to be gathered by the agency, and factors to consider in determining whether to march in if the prerequisites are met. Before an agency can assess whether factors specific to the circumstances at hand meet one of the four statutory criteria for march-in, it would need to gather facts to ascertain linkage between the agency’s funding and the invention at issue. The draft guidance included eight hypothetical scenarios illustrating how an agency might balance various factors to ensure that its decision to exercise or not exercise march-in rights supports the commercialization and utilization objectives of the Bayh-Dole Act.

The following summarizes three elements of the draft guidance.

Subject Inventions

The first prerequisite for an agency considering march-in is that the invention under consideration be a subject invention under the Bayh-Dole Act. The draft guidance noted that determining whether an invention is a subject invention could be a complex and intensive fact-finding inquiry. The inquiry would involve gathering facts to determine whether (1) an agency provided funding covered by the Bayh-Dole Act, (2) a linkage exists between the funding agreement and invention in question, and (3) the invention meets the definition of a subject invention.

Establishing federal involvement in patented inventions is challenging. Patents for inventions arising from federally funded research are required to disclose federal support. However, some patents that disclose federal funding would not meet the statutory definition of a subject invention.[19] Conversely, as we found in prior work, some patents that may involve subject inventions do not disclose federal support or disclose it incorrectly (for example, failing to identify the relevant funding agreement), which may necessitate additional fact-finding.[20] As described in the draft guidance, an agency may want to consider if there are existing publications that describe the invention and disclose funding agreements supporting the research. It may also want to consider if an inventor named in the patent conducted research under a funding agreement with the agency, among other things.

Product Price as a Factor for March-In Consideration

The draft guidance described how an agency may assess each of the four statutory criteria for march-in. Whereas the Bayh-Dole Act’s provisions do not explicitly mention the price of a product commercialized from a federally funded invention as a basis for march-in, the draft guidance proposed including product price as a factor an agency could consider in deciding whether to exercise march-in rights (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: NIST Draft Guidance Proposed Using Price as a Factor Under Two Statutory Criteria for Exercising March-In Rights

Note: Under the Bayh-Dole Act, the term “practical application” means to manufacture in the case of a composition or product, to practice in the case of a process or method, or to operate in the case of a machine or system; and, in each case, under such conditions as to establish that the invention is being utilized and that its benefits are to the extent permitted by law or government regulations available to the public on reasonable terms.

Specifically, according to the draft guidance, an agency could consider price in deciding whether to exercise march-in rights under two statutory criteria (practical application and health or safety need):

· For practical application, an agency may consider whether the subject invention was licensed and whether there was a product embodying the invention on the market. If the funding recipient or licensee had commercialized the product, but the price or other terms at which the product was offered to the public were not reasonable, the agency might need to further assess whether march-in was warranted.

· For health or safety need, an agency may consider whether the funding recipient or the licensee was exploiting a health or safety need order to set a product price that was extreme and unjustified given the totality of circumstances. The agency could examine whether the funding recipient or licensee, in response to a disaster, implemented a sudden, steep price increase that was putting people’s health at risk. It might also review the initial price if it appeared that the price was extreme, unjustified, and exploitative of a health or safety need.

· For public use, the draft guidance suggested that a funding agency may evaluate whether any federal regulations applied to the use of products commercialized from the subject invention. It may assess whether the recipient of federal funding or licensee had taken reasonable steps to address any needs related to these federal regulations, including making the subject invention available to all who require it.

· The domestic manufacturing criterion relates to the requirement that exclusive licenses to use or sell in the United States include an agreement that products embodying subject inventions be manufactured substantially in the United States.[21] According to the draft guidance, a funding agency may evaluate whether the statutory requirement for domestic manufacturing applied, request specific details on where any products were being manufactured, and determine whether a manufacturing waiver was required and a request to waive the preference for U.S. industry had been granted.

The draft guidance did not define an unreasonable price or provide direction for how an agency would determine that the price of a product unreasonably limited its availability to the public.

Illustrative Scenarios

The draft guidance included eight hypothetical scenarios featuring a variety of technologies. The scenarios were developed with participation from different agencies participating in the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole. They illustrated how an agency might balance various factors to ensure that its decision to exercise or not exercise march-in rights supports the commercialization and utilization objectives of the Bayh-Dole Act.

Two of the scenarios included a discussion of price and six did not. The two scenarios—one involving a water purification technology and the other respiratory masks—discussed price as a factor for exercising march-in to alleviate health or safety needs in a public health emergency. Considering that much of the public debate about march-in rights has centered on drug prices, it is notable that none of the three drug development scenarios included in the draft guidance discussed price as a basis for march-in.

Draft Guidance Was Developed Through Interagency Process; NIST Does Not Have a Timeline for Finalizing It

The draft guidance was developed by a subcommittee of the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole through a process convened and led by NIST. The subcommittee comprised officials from 10 agencies, who volunteered to serve on it.[22] The subcommittee met 15 times between December 2022 and May 2024 (see fig. 4). NIST officials told us that in drafting the guidance the subcommittee considered feedback from two earlier efforts.[23] According to NIST officials, prior to the publication of the RFI in the Federal Register on December 8, 2023, the draft guidance was presented to the entire Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole for review and comment. Afterwards, a revised draft, based on working group members’ comments and suggested changes, was sent to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the Office of Management and Budget, which then facilitated a formal interagency review and comment process. After publication of the draft guidance in the Federal Register, NIST hosted a public informational webinar on December 13, 2023, to describe its elements and explain how to submit comments to the RFI.

According to NIST officials, the draft guidance was intended to represent interagency consensus. However, among the agencies we interviewed that participated in drafting the guidance (DOD, DOE, DOT, and HHS), some agency officials disagreed with the inclusion of price as a factor for exercising march-in rights because of concerns that it would hinder the commercialization of federally funded inventions. According to other officials, the agency coordination process considered concerns related to the inclusion of price, and agency concurrence with the draft guidance should not convey unanimity regarding every aspect of the guidance.

Public comments were submitted to Regulations.gov during the 60-day period, which ended on February 6, 2024. According to NIST officials, NIST analyzed the comments and presented a summary of its analysis to the entire Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole in May 2024. NIST also circulated revised guidance—which reflected changes, incorporating input from public comments, made by the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole subcommittee that drafted the guidance—among the working group members. Working group members provided comments and feedback before a revised draft guidance was once again submitted for interagency review process through the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the Office of Management and Budget. Comments from agencies and the National Economic Council led to another draft revision in August 2024.

As of December 2025, the draft guidance had not been finalized, and NIST did not have a timeline for finalizing it, according to NIST officials. They stated that after assessing the totality of the feedback from other federal agencies and from the public comments in response to the RFI, NIST recognized there was not enough consensus among the agencies and stakeholders regarding the draft guidance. In addition, with the change in the Administration in January 2025, NIST needed to deliberate on the next steps in the context of changing policy priorities, according to NIST officials.

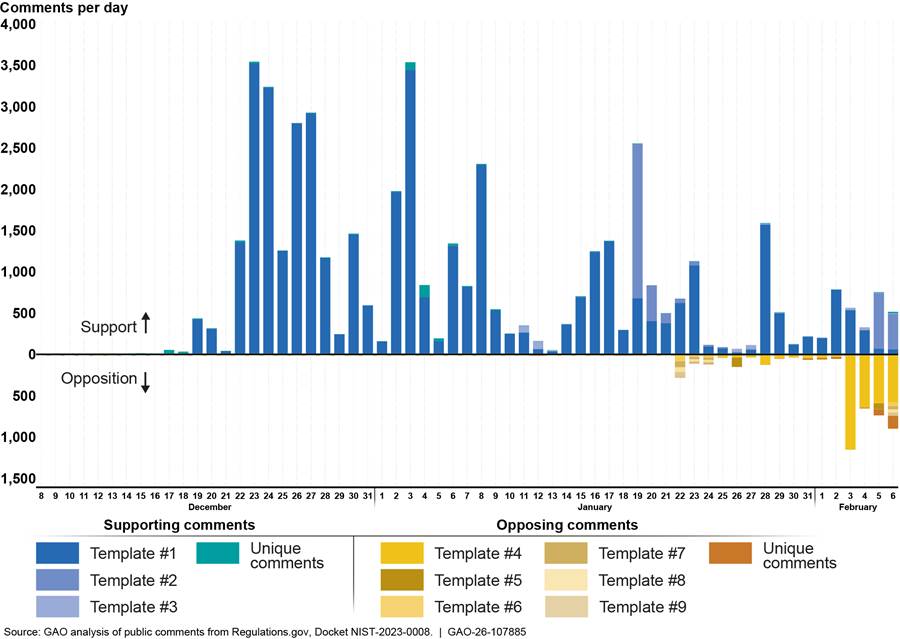

Most Public Comments Supported Draft Guidance, but Views Varied on Efficacy and Risks to Innovation

In response to the NIST RFI, 29,202 commenters submitted 51,762 comments expressing support for or opposition to the draft guidance (see table 1). The lower number of commenters—representing unique persons or organizations—indicates that some commenters submitted multiple comments. The majority of comments (47,337 comments, or about 91 percent) and commenters (24,850 commenters, or about 85 percent) expressed support for the draft guidance.[24]

|

Sentiment |

Comments |

Commenters |

||

|

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

|

Generally support |

47,337 |

91.45 |

24,850 |

85.10 |

|

Generally oppose |

4,425 |

8.55 |

4,352 |

14.90 |

|

Total |

51,762 |

100.00 |

29,202 |

100.00 |

Source: GAO analysis of public comments from Regulations.gov, Docket NIST-2023-0008. | GAO‑26‑107885

Note: A total of 51,845 public comments were posted in the Regulations.gov docket for the draft guidance. The table excludes 83 comments that did not express support or opposition, were unrelated to the draft guidance, or were exact duplicates of a comment included in the analysis. Comments are public comments submitted in response to the draft guidance. Commenters are persons and organizations that submitted comments. Some commenters submitted more than one comment.

Among the 47,337 supportive comments, most expressed concern about high prescription drug prices and support for using march-in rights to lower them.[25] Some comments suggested that although federally funded research contributed to the invention and development of a marketable product, unaffordable prices for consumers undermined the taxpayers’ return on investment. For example, one comment stated that a drug’s availability alone does not fulfill the criterion of practical application if its high price makes it inaccessible.

In an interview, one stakeholder cited the example of the prostate cancer drug Xtandi. They stated the drug was costing some U.S. patients around $190,000 in 2022 but was sold at a significantly lower price of $30,000 to $57,000 in other high-income countries. The stakeholder viewed this case as an illustration of why march-in action was warranted to address concerns about the high cost of drugs in the United States.

Two stakeholders we interviewed noted that exercising march-in rights on the basis of price would likely affect a small number of drugs, since the authority could apply only to drugs developed with federal funding. They noted that action could be valuable for patients taking those drugs. They believed march-in on its own would not solve drug affordability but could be one of several tools the federal government might use to address it.

Universities Submitted Comments Opposing the Draft Guidance

Universities submitted 52 comments, all of which expressed opposition to the draft guidance. Universities expressed several concerns about potential effects of exercising march-in rights on the basis of price.[26]

Most university comments emphasized that the draft guidance could create disincentives for licensing federally funded inventions. For example, 29 comments stated that exercising march-in rights based on price could reduce universities’ ability to license these inventions because private partners and industry may be deterred by the potential risk of march-in being exercised on technologies they have invested in. Thirty-two comments explained that technology transfer offices, which typically handle universities’ patent licensing operations, would have their bottom line or licensing revenue impacted if they are not able to secure or maintain license agreements with private partners and industry. Twenty-seven comments also noted that the draft guidance would have a broad impact across multiple technology sectors, not just the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, according to most university comments, fewer inventions would move from the laboratory to the market. This would undermine the Bayh-Dole Act’s goal of encouraging commercialization of inventions arising from federally funded research.

Universities also expressed concern that applying march-in based on price could deter private investment in companies that license inventions from universities. Fourteen comments emphasized that early-stage technologies developed with federal funding often require significant private capital to move from research to commercialization. If investors perceive a risk that government agencies might later intervene in a product’s pricing, they may be less willing to invest in companies working with federally funded intellectual property. Thirty-two comments noted this would be particularly concerning for startups and small businesses; several emphasized that those that rely on venture capital to fund product development and bring new technologies to market would be at risk.

Sixteen comments warned that, if implemented, the draft guidance could result in higher drug prices. Six stated a price-based march-in could discourage companies from licensing and developing new drugs based on university research. This would reduce the number of federally funded inventions that ultimately reach patients. The reduced pipeline could result in fewer drugs and possibly higher prices, according to these comments.

In addition, in interviews, officials from the universities that submitted comments noted that existing license agreements already include provisions to ensure the licensed inventions are commercialized for public use. One official pointed out that these agreements typically require licensees to meet due diligence milestones, which include deadlines for R&D and commercialization activities. For example, a licensee must bring the licensed invention to market and sustain marketing efforts until the agreement ends. The official stated that the university rarely has to intervene or remind licensees about these milestones. However, licensees do not always succeed in commercializing inventions, often due to funding or technical challenges. In such cases, the university terminates the license. The official further explained that the university could relicense the invention to another company if there is a suitable fit.

Other Opposing Comments Cited the Intent of Bayh-Dole and Potential Adverse Effects on Commercialization

In addition to the comments from universities, other comments opposing the draft guidance raised a range of concerns. These included that the guidance may contradict the Bayh-Dole Act’s primary goal of commercializing federally funded inventions, have unintended consequences across industries and public-private partnerships, and undermine the U.S. position in global innovation.

We analyzed a random sample of comments opposing the draft guidance, some of which viewed it as contradicting the Bayh-Dole Act’s primary goal of promoting the commercialization of federally funded inventions.[27] For example, four comments stated that using price as a consideration for march-in would discourage potential licensees and their investors from commercializing federally funded inventions, as they would be less willing to develop and fund early-stage technologies if there were a risk that federal agencies could exercise march-in rights based on product price.

The potential to lower the price for a small number of drugs needs to be weighed against the risk of undermining the broad innovation ecosystem enabled by Bayh-Dole, according to some comments in our sample. One comment noted that the draft guidance could affect multiple industries. It warned that exercising march-in based on price could unintentionally impact technology areas other than drug development—such as, semiconductors, or computing—where public-private partnerships also play a critical role in commercialization. According to most comments (21 in our sample), the success of the Bayh-Dole framework depends on reliable expectations for private entities investing in the development of federally funded inventions. Even a small perceived risk of price-based intervention, they noted, could have a chilling effect across the broader commercialization landscape.

In addition, some comments in our sample and commenters we interviewed said the draft guidance could unintentionally reduce interest in licensing federally funded inventions. Two comments raised concerns about the draft guidance’s potential effect on small businesses and startups, which often rely on licensing inventions from universities and a combination of federal funding and private capital to bring new technologies to market. In interviews, three commenters warned that without the protections and assurances historically offered by Bayh-Dole, fewer businesses and investors would choose to take on the risk of commercializing federally funded inventions.

According to seven comments in our sample, the draft guidance could negatively affect the U.S. position as a global leader in innovation, potentially placing the country at a competitive disadvantage. Moreover, two comments argued that introducing price as a basis for march-in could create uncertainty around the development of federally funded inventions, discouraging investment, and push industries to other countries.

Asserting March-In Based on Price Could Affect Federally Funded Technologies in Multiple Industries

Because no federal agency has exercised march-in rights, it is only possible to discuss hypothetical impacts of implementing the draft guidance. A federal agency could exercise march-in rights based on product price only if a product resulting from a federally funded invention has an unexpired patent subject to Bayh-Dole. The potential for march-in is higher for technologies with a high volume of patenting activity arising from federally funded research—such as pharmaceuticals, computer technology, and electrical machinery—and for products associated only with patents subject to Bayh-Dole. Although most public comments on the draft guidance expressed support for using march-in to lower drug prices, studies estimate that march-in based on price would likely affect a small number of drugs, because the majority of drugs have patents that are not subject to Bayh-Dole.

Exercising March-In Rights Could Impact Federally Funded Technologies in Multiple Industries

March-in on the basis of product price is possible only if a product is associated with at least one active patent that resulted from federally funded research and is subject to the Bayh-Dole Act. A patent disclosing federal research funding is known as a government interest patent. The potential for march-in is higher in industries with a lot of patenting activity arising from federally funded research, such as the pharmaceutical industry. However, federal research funding does not always entail patented technologies or products. For example, DOT’s Federal Highway Administration provides funding for R&D to improve road signing, but limits use of proprietary intellectual property in certain aspects of signing.[28]

To determine which industries may be affected by an exercise of march-in rights, including on the basis of price, we analyzed public data on U.S. government interest patents. According to our analysis, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted 129,643 U.S. government interest patents with application dates in calendar years 2000 through 2024.[29] The top 10 technologies represented in these patents include medical and biomedical technologies, which account for more than a third of the government interest patents (see numbers 1, 3, 5, and 7 in table 2), as well as measurement technology, computer technology, electrical machinery, chemical engineering, and optics.

Table 2: Technologies Represented in U.S. Patents Disclosing Federal Funding with Application Dates in Calendar Years 2000–2024

|

Technology |

Number of patents in which the technology is represented |

Percentage |

|

|

Top 10 |

186,627 |

69.1 |

|

|

1. Medical technology |

31,611 |

11.7 |

|

|

2. Organic fine chemistry |

28,716 |

10.6 |

|

|

3. Pharmaceuticals |

27,490 |

10.2 |

|

|

4. Measurement |

26,189 |

9.7 |

|

|

5. Biotechnology |

19,937 |

7.4 |

|

|

6. Computer technology |

13,720 |

5.1 |

|

|

7. Analysis of biological materials |

13,038 |

4.8 |

|

|

8. Electrical machinery, apparatus, energy |

10,573 |

3.9 |

|

|

9. Chemical engineering |

8,201 |

3.0 |

|

|

10. Optics |

7,152 |

2.6 |

|

|

Other |

83,603 |

30.9 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of PatentsView data. | GAO‑26‑107885

Note: According to our analysis, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted 129,643 U.S. patents that disclosed federal support, with application dates in calendar years 2000 through 2024. To determine the technologies represented by these patents, we analyzed the patents’ World Intellectual Property Organization field classifications. Because a patent can have more than one such classification, the numbers of patents in the table are not mutually exclusive.

It is difficult to estimate the extent to which products arising from these technologies—or what percentage of the products—are likely to be subject to march-in. Patenting activity in a technology area may not correspond to how often patents are licensed and subsequently incorporated into products. If a product is associated only with government interest patents, the funding agency may determine that the circumstances do not meet statutory criteria for march-in, product price may be an insufficient condition, or march-in may not work as a tool to lower price by introducing competition. If a product is associated with a mix of patents, the march-in considerations are more complicated because the agency would need to evaluate whether exercising march-in only on the subset of government interest patents is likely to have any impact.

According to one study, there were, on average, 3.5 patents per drug in 2005.[30] We did not find studies that estimated the average number of patents per product in non-pharmaceutical industries or how common it is for those patents to be a mix of government interest and other patents.

If the implementation of the guidance reduces the licensing of patents arising from federally funded research, the potential impacts on innovation are difficult to discern because the relationship between innovation and patenting is not always clear. Research shows that patenting is not always correlated with innovation, and the intensity of patenting activity varies by industry. One researcher estimates that only 50 percent of firms doing R&D patent their innovations, and some firms avoid patenting their most important innovations at all because patents expire.[31] According to another study, more than half of product innovation is generated by firms that do not patent.[32] One economist, who studied patenting extensively, argues that in the pharmaceutical industry, known for a high level of patenting activity, there is no real correlation over time between patenting and drug innovation. According to this economist, patents may be a better indicator of R&D inputs than R&D outputs.[33]

Studies Estimate That March-In Based on Price Would Likely Affect a Small Number of Drugs

Three studies published after the release of the draft guidance sought to estimate the number of drugs that could be affected if HHS were to exercise march-in rights, including on the basis of price. The starting point for the studies entailed identifying a universe of drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and linked to patents arising from federally funded research.[34] This was accomplished by determining which drugs were associated with at least one government interest patent. The following summarizes these studies:

· A study by the Congressional Research Service identified 39 FDA-approved drugs associated with at least one government interest patent unexpired at the time of the analysis.[35] Some drugs were associated with multiple such patents. The study noted, among other things, that not all the government interest patents associated with these drugs might be considered subject inventions under Bayh-Dole or meet the statutory criteria for march-in.

· A study by HHS researchers identified 39 FDA-approved drugs involving 63 drug products associated with at least one unexpired government interest patent.[36] Among the 63 products, 13 had only government interest patents, and 50 had a mix of government interest and other patents. Because the majority of the products involved a mix of patents and a federal agency can march in only on government interest patents (as long as they meet the definition of the subject invention and statutory criteria for march-in), the authors noted that their findings highlighted the potential complexity of exercising march-in rights on a product with a mix of patents.

· Whereas the two studies above sought to identify drugs covered by unexpired government interest patents, an academic study expanded the time frame by examining contemporary and historical data on FDA approvals going back to 1985.[37] According to this study, from 1985 through 2022, FDA approved 883 new drugs, including 68 drugs (8 percent) with at least one government interest patent.[38] The study assumed that march-in can be exercised to lower the price of a drug to its generic equivalent only if all unexpired patents on the drug were subject to Bayh-Dole. It estimated that only 18 (or 2 percent) of the 883 drugs were covered entirely by government interest patents and could be eligible for march-in.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to NIST, DOD, DOE, DOT, and HHS for review and comment. NIST, DOT, and HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. DOD and DOE did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of Commerce, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Transportation; and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have questions about this report, please contact me at WrightC@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Candice N. Wright

Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Requesters

The Honorable Thom Tillis

Chair

Subcommittee on Intellectual Property

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Darrell Issa

Chair

Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, Artificial Intelligence, and the

Internet

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

The Honorable Christopher A. Coons

United States Senate

The Honorable Jake Auchincloss

House of Representatives

This report examines: (1) key elements of the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights (draft guidance) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)-led interagency process for developing it; (2) stakeholder views, as reflected in public comments in response to the NIST request for information (RFI), on potential positive and negative impacts of the draft guidance; and (3) available information about the potential impacts of the draft guidance on the commercialization of federally funded inventions in different industries.[39]

To examine the guidance and the interagency process for drafting it, we reviewed the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, the structure and content of the draft guidance, and two earlier NIST-led efforts: the April 2019 Return on Investment Initiative for Unleashing American Innovation report and the January 2021 notice of proposed rulemaking that proposed changes to the Bayh-Dole regulations.[40] We also reviewed NIST’s summary of the public comments on the proposed rule. We interviewed officials involved in drafting the guidance from NIST, and the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), and Transportation (DOT). In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provided written responses. We selected these agencies because they are members of the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole and were represented on the working group’s subcommittee that drafted the guidance. In addition, these agencies provide funding for R&D, and three of them (DOD, DOE, and HHS) have received march-in petitions.

To examine stakeholder views, as reflected in public comments, on potential positive and negative impacts of the draft guidance, we conducted quantitative and qualitative analyses of the comments submitted in response to the NIST RFI between December 8, 2023, and February 6, 2024, and interviewed select stakeholders, including those who submitted comments. We downloaded 51,845 comments posted to the Regulations.gov docket for the RFI.[41] Using statistical software and manual analysis, we determined that 51,762 comments expressed support for or opposition to the draft guidance. We excluded from our analysis 83 comments that did not express support or opposition, were unrelated to the draft guidance, or were exact duplicates of the comments included in the analysis. To estimate the number of unique commenters, we used statistical software to analyze the names and locations associated with each public comment. Specifically, we identified instances where the same name, city, state, and postal code appeared across multiple comments, allowing us to distinguish between commenters who submitted more than one comment and those who submitted only one.

We further determined, using statistical software, that among the 51,762 comments in our analysis, 50,740 (98 percent) replicated templates, whereby comments with nearly identical content were submitted by multiple commenters. We identified nine templates, three of which expressed support for the guidance and six opposition to it. The remaining 1,022 comments (2 percent) were unique comments, and two analysts reviewed each of these comments to determine its position on the guidance. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved to ensure consistency and reliability. (See app. III for more detailed information about the results of this analysis). We assessed the reliability of the data by conducting electronic testing, confirming there were no missing or irregular values, and comparing the results of our analysis with the results of NIST’s public comment analysis. We determined the data to be reliable for the purposes of estimating the extent of support for and opposition to the draft guidance.

We also conducted a qualitative analysis of 102 comments, which were selected from the 1,022 unique comments and involved two different sets: the 52 comments submitted by universities and a random sample of 50 other comments. Universities submitted a total of 52 comments, all expressing opposition to the guidance. We analyzed the university comments using NVivo software to code for common themes and concerns.

We analyzed a random sample of 50 comments, which consisted of 25 expressing support for and 25 expressing opposition to the draft guidance. We analyzed these comments for common themes in favor and against the guidance. For each set of 25 comments, we use “some” to refer to 2–12 comments and “most” to refer to 13–25 comments.

To conduct the qualitative analysis, two analysts independently reviewed and coded each comment. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved to ensure consistency and reliability.

We also interviewed 20 stakeholders who submitted public comments or participated in related NIST initiatives that preceded the draft guidance. We selected stakeholders who supported and opposed the draft guidance and represented a range of institutions and viewpoints. We interviewed former NIST officials, academics who studied the management of federally funded intellectual property, a technology transfer professional, representatives of three universities and a university technology transfer association, business and venture capital associations, a law association, patient advocacy organizations, medical societies, an alliance of community health plans, and a labor union. These views are illustrative and cannot be generalized to all stakeholders.

To review available information about potential impacts of the draft guidance on the commercialization of federally funded inventions in different industries, we worked with a GAO research librarian to conduct a literature search of studies analyzing potential impacts of exercising march-in rights. From this search, we identified and selected relevant studies to include in our review. In addition, we conducted an analysis of data for patents with application dates in calendar years 2000 through 2024 from the public PatentsView database maintained by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. We identified 129,643 U.S. patents disclosing federal support in government interest statements. This number likely underestimates the patenting of inventions developed with federal funding for two reasons. First, we did not review certificates of correction for possible corrections to the government interest statements after the patents were granted. Second, as we and others found in the past, there are gaps in the disclosure of federal support in patents.[42]

We downloaded the following variables from PatentsView: patent ID, patent application and grant dates, government interest statement text, and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) field classification. We used WIPO field classification to identify the top ten technology fields represented in the 129,643 patents.

To assess the reliability of PatentsView data, we reviewed our prior reliability determination and the data used for this report for potential errors.[43] Based on our review, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting on the distribution of patents developed with federal funding among different industries that could be affected if federal agencies were to exercise march-in rights.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2024 to February 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole considered feedback from two earlier efforts in developing the draft guidance, according to NIST officials:

· The Return on Investment Initiative. In April 2019, NIST released the Return on Investment Initiative for Unleashing American Innovation report, which was the culmination of a NIST-led effort that sought to identify strategies to maximize the commercialization of federal investments in science and technology for public benefit.[44] The report presented findings from public comments, multiple stakeholder engagement sessions, and an extensive review of relevant studies. Regarding march-in rights, the report stated that stakeholders sought more clarity on (1) whether agencies could use march-in rights as a mechanism to control or regulate the market price of goods and services and (2) definitions for reasonable terms contained within the existing statutory definition of practical application. Following the report’s publication, NIST took several steps to implement the strategies it identified related to the Bayh-Dole Act, including a rulemaking process to update the Bayh-Dole regulations and the modernization of the iEdison database.[45]

· Proposed Rulemaking for the Bayh-Dole Act. Seeking to update the Bayh-Dole regulations, NIST initiated a rulemaking process. On January 4, 2021, NIST published a notice of proposed rulemaking, which proposed several changes to the Bayh-Dole regulations and requested public comments.[46] One of the proposed changes included a provision that march-in could not be exercised based exclusively on “the pricing of commercial goods and services arising from the practical application” of a federally funded invention. NIST received over 81,000 public comments on the proposed rulemaking, the majority of which addressed the march-in provision, according to NIST’s analysis of the comments.

At the direction of Executive Order 14036, NIST finalized the rule without the march-in provision.[47] In the final rule, published on March 24, 2023, NIST stated its intent to engage with stakeholders and agencies with the goal of developing a comprehensive framework for agencies considering the use of march-in rights. This separate effort resulted in the release of the draft guidance in December 2023. The position expressed in the draft guidance—that the price of a commercialized product resulting from a federally funded invention can be a factor among several for exercising march-in rights—is not inconsistent with the position expressed in the notice of proposed rulemaking that price cannot be the sole factor for exercising march-in rights.

A total of 51,845 public comments were posted for public download in the Regulations.gov docket for the Request for Information Regarding the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).[48] The comments were submitted during a 60-day period from December 8, 2023, through February 6, 2024.

According to our analysis, 51,762 comments expressed support for or opposition to the draft guidance.[49] Among them, 91.5 percent expressed support and 8.5 percent expressed opposition (see table 3). The vast majority of comments replicated templates, whereby comments with nearly identical content were submitted by multiple commenters. We identified nine templates (which accounted for about 98 percent of comments) and non-template “unique” comments (which accounted for about 2 percent).

|

Sentiment and type |

Number of comments |

Percentage |

|

Generally support |

||

|

Template 1 |

42,587 |

82.2 |

|

Template 2 |

3,715 |

7.2 |

|

Template 3 |

379 |

0.7 |

|

Unique |

656 |

1.3 |

|

Subtotal |

47,337 |

91.5 |

|

Generally oppose |

||

|

Template 4 |

3,241 |

6.3 |

|

Template 5 |

183 |

0.4 |

|

Template 6 |

175 |

0.3 |

|

Template 7 |

164 |

0.3 |

|

Template 8 |

149 |

0.3 |

|

Template 9 |

147 |

0.3 |

|

Unique |

366 |

0.7 |

|

Subtotala |

4,425 |

8.5 |

|

Total |

51,762 |

100.00 |

Source: GAO analysis of public comments from Regulations.gov, Docket NIST-2023-0008. | GAO‑26‑107885

Note: A total of 51,845 public comments were posted in the Regulations.gov docket for the draft guidance request for information. The table excludes 83 comments that did not express support or opposition, were unrelated to the draft guidance, or were exact duplicates (the same content submitted by the same commenter more than once) of a comment included in the analysis.

aPercentages may not sum to the “Generally oppose” subtotal due to rounding.

Generally, comments replicating the templates were submitted by members of the public, unique comments by members of the public and by organizations. Commenters included concerned individuals, patients, researchers, technology transfer professionals, former government officials, universities, research organizations, business groups, patient advocacy groups, and organizations focusing on specific diseases.

Figure 5 shows the submission dates for the 51,762 public comments submitted to the Regulations.gov docket for the draft guidance.

Figure 5: Public Comments on the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights Submitted Between December 8, 2023, and February 6, 2024

Table 4 shows examples of content in the templates.

|

Template 1 (expresses support for the draft guidance) OFFICIAL COMMENT NIST MARCH-IN RIGHTS RULE DOCKET NO. NIST-2023-0008. I SUPPORT THE USE OF MARCH-IN AUTHORITY TO LOWER PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRICES. AMERICANS SHOULDN’T PAY THE HIGHEST PRICES IN THE WORLD FOR MEDICINES THAT WERE DEVELOPED WITH OUR TAX DOLLARS. THE FINAL GUIDELINES MUST ALSO ENSURE THAT THE VAST MAJORITY OF DRUGS, WHICH ARE ALREADY PRICED AT EGREGIOUS LEVELS, WILL BE INCLUDED AS CANDIDATES FOR USE OF MARCH-IN RIGHTS. WE NEED THESE GUIDELINES TO BE IRON-CLAD AND BRING DOWN THE EXORBITANT PRICES OF PRESCRIPTION DRUGS! |

|

Template 2 (expresses support for the draft guidance) THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT SHOULD USE ITS AUTHORITY TO LOWER PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRICES. IT’S NOT RIGHT THAT AMERICANS OFTEN HAVE TO PAY MANY

TIMES MORE THAN PEOPLE IN PLEASE UPDATE THIS GUIDANCE TO DIRECT AGENCIES TO USE

THEIR MARCH-IN RIGHTS TO |

|

Template 3 (expresses support for the draft guidance) I SUPPORT THE USE OF “MARCH-IN” AUTHORITY TO LOWER PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRICES. UNDER THE 1980 BAYH DOLE ACT, THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

RETAINS “RESIDUAL RIGHTS” TO THE ADMINISTRATION SEES “MARCH-IN RIGHTS” AS AN

EFFECTIVE TOOL TO REDUCE PLEASE USE “MARCH-IN” AUTHORITY TO DECREASE

PRESCRIPTION DRUG COSTS FOR |

|

Template 4 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) MARYLAND IS A NATIONAL LEADER IN BIOPHARMACEUTICAL

INNOVATION, LEADING THE OUR CURRENT IP SYSTEM IS THE FOUNDATION FOR NEW

TREATMENTS AND CURES. HOWEVER, PLEASE PROTECT OUR NATION’S ABILITY TO BRING NEW

TREATMENTS AND CURES FROM A |

|

Template 5 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) I AM WRITING TODAY TO ASK THAT YOU NOT MOVE FORWARD

WITH FINALIZING THE RECENT AS SOMEONE WHO HAS A PERSONAL STAKE IN THE

DEVELOPMENT OF NEW MEDICINES, I HAVE THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD BE ENCOURAGING, NOT PUNISHING,

PARTNERSHIPS BETWEEN THE I HOPE YOU RECOGNIZE THIS AND WILL NOT FINALIZE THE

NEWLY PROPOSED MARCH-IN |

|

Template 6 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) THIS PROPOSAL POSES A SERIOUS THREAT TO THE SANCTITY

OF PRIVATE SECTOR |

|

Template 7 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) NIST’S DRAFT FRAMEWORK TO ALTER THE BAYH-DOLE ACT

THREATENS TO DISRUPT THE I URGE YOU TO WITHDRAW THIS GUIDANCE. |

|

Template 8 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) THE PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE BAYH-DOLE ACT ENDANGER

THE LIFELINE OF SMALL I URGE YOU TO WITHDRAW THIS GUIDANCE. |

|

Template 9 (expresses opposition to the draft guidance) THE PROPOSED FRAMEWORK BY NIST, INVOLVING PRICING

CONSIDERATIONS IN THE EXERCISE I URGE YOU TO WITHDRAW THIS GUIDANCE. |

Source: GAO analysis of public comments. | GAO‑26‑107885

Note: We identified public comments that followed a template by analyzing text for repeated phrases and standardized wording. To ensure accuracy, we used text analysis to find comments with identical or nearly identical language, as shown above, and categorized them as template submissions.

GAO Contact

Candice N. Wright, WrightC@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Tind Shepper Ryen (Assistant Director), Sada Aksartova (Analyst-in-Charge), Alejandro Gammel-Perera, Patrick Harner, Alec McQuilkin, Jenique Meekins, Joseph Rando, and Smon Tesfaldet made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act, Pub. L. No. 96-517, 94 Stat. 3015 (1980) (codified as amended at 35 U.S.C. §§ 200-212), commonly referred to as the Bayh-Dole Act.

[2]88 Fed. Reg. 85593 (Dec. 8, 2023).

[3]National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2023–2024.

[4]In addition to basic and applied research, the federal government funds experimental development that may also lead to patentable inventions.

[5]A patent grants the right to “exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling” the invention throughout the United States or importing into the United States. 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(1). This right can be assigned to other entities.

[6]AUTM, previously known as the Association of University Technology Managers, is a nonprofit association of more than 3,000 members who work in over 800 universities, research centers, hospitals, businesses, and government organizations in and outside the United States. AUTM conducts membership surveys to measure research funding as well as patenting and licensing activity, among other things.

[7]Under the Bayh-Dole Act, the term “subject invention” means any invention of a contractor conceived or first actually reduced to practice in the performance of work under a funding agreement with the federal government.

[8]In the context of the Bayh-Dole Act implementation, the term “contractor” can mean the recipient of a federal funding award, including a contract, grant, or cooperative agreement.

[9]This statement is known as the government interest statement or government support clause.

[10]Patents generally expire 20 years after the date the patent application was filed.

[11]The term “practical application” means “to manufacture in the case of a composition or product, to practice in the case of a process or method, or to operate in the case of a machine or system; and, in each case, under such conditions as to establish that the invention is being utilized and that its benefits are to the extent permitted by law or Government regulations available to the public on reasonable terms.” 35 U.S.C. § 201(f).

[12]Federal officials at DOD, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the National Institutes of Health expressed similar views in the past. See GAO, Federal Research: Information on the Government’s Right to Assert Ownership Control over Federally Funded Inventions, GAO‑09‑742 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2009).

[13]The Secretary of Commerce has delegated the authority to issue the implementing regulations for the Bayh-Dole Act to the NIST Director.

[14]Technology transfer includes the process by which inventions and technologies are transferred from federal labs, universities, or other research institutions to industry where they can be developed into commercial products or services.

[15]Andrew W. Mulcahy, Daniel Schwam, and Susan L. Lovejoy. International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Estimates Using 2022 Data (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, February 2024), https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/comparing-prescription-drugs, accessed July 9, 2025. The study compared prescription drug prices and availability in the United States and other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. According to the study, most new drugs were available first in the United States before being launched in other countries. According to the Food and Drug Administration, which approves drugs marketed in the United States, a brand name drug is a drug marketed under a proprietary, trademark-protected name, and a generic drug is the same as a brand name drug in dosage, safety, strength, how it is taken, quality, performance, and intended use.

[16]There is not an official public compendium of march-in petitions received by federal agencies. According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), as of August 2016, HHS received six march-in petitions; CRS, March-In Rights under the Bayh-Dole Act, R44597 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 22, 2016). According to the information on march-in petitions compiled by the public interest advocacy group Knowledge Ecology International, DOD, DOE, and the Federal Trade Commission also received them, and the first petition was submitted to HHS in 1997; see https://www.keionline.org/march-in-rights-timeline, accessed Sept. 9, 2025.

[17]The letter is available at https://www.techtransfer.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdfs/NIH_Decision_Xtandi_March-In_Request(2023), accessed Jan. 15, 2026.

[18]The three Xtandi patents cited in the petitions expire between May 2026 and August 2027.

[19]According to the draft guidance, an invention that arose under a funding agreement made primarily for educational purposes may not be a subject invention. In addition, not all funding awards issued by the federal government are subject to the Bayh-Dole Act: for example, other transaction agreements may not be subject to the act’s requirements. We examined the use of other transaction agreements in prior work. See, for example, GAO, Other Transaction Agreements: Improved Contracting Data Would Help DOD Assess Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107546 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 3, 2025).

[20]GAO, National Institutes of Health: Better Data Will Improve Understanding of Federal Contributions to Drug Development, GAO‑23‑105656 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 4, 2023) and Biomedical Research: Improvements Needed to the Quality of Information About DOD and VA Contributions to Drug Development, GAO‑24‑107061 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 26, 2024).

[21]35 U.S.C. § 204. The requirement for such an agreement may be waived by the agency under whose funding agreement the invention was made upon a showing by the small business firm, nonprofit organization, or patent owner that reasonable but unsuccessful efforts have been made to grant licenses on similar terms to potential licensees that would be likely to manufacture substantially in the United States or that under the circumstances domestic manufacture is not commercially feasible.

[22]The following agencies were represented on the subcommittee: the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and Homeland Security; DOD; DOE; DOT; HHS; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the National Science Foundation; and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

[23]The two earlier efforts were the Return on Investment Initiative, resulting in a report published in April 2019, and the 2021 proposed rulemaking for the Bayh-Dole Act. For more information about these efforts, see app. II.

[24]A total of 51,845 public comments were posted on Regulations.gov. Our analysis excludes 83 comments that did not express support or opposition, were unrelated to the draft guidance, or were exact duplicates of a comment included in the analysis. We identified unique commenters by using names and locations submitted to Regulations.gov. For more information about our methodology, see app. I.

[25]For more detailed information about the comments, see app. III.

[26]In addition to the 52 comments submitted by individual universities, several organizations representing universities submitted comments opposing the guidance and expressing concerns similar to those in the university comments. These organizations included AUTM, the Association of American Universities, the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, and the Association of American Medical Colleges. A nonprofit organization representing university students and recent alumni called Universities for Allied Medicines submitted a comment supporting the draft guidance.

[27]We analyzed a random sample of 25 comments opposing the draft guidance for common themes. For each set of 25 comments, we use “some” to refer to 2–12 comments, and “most” to refer to 13–25 comments. For more information about our methodology, see app. I.

[28]The Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways—which ensures uniformity of traffic control devices across the United States by setting minimum standards and providing guidance—prohibits patented products that alter or impact the message a sign conveys to the road user due to the adverse impacts on uniformity. For example, the shape and color of a stop sign or the meaning and sequencing of the red, yellow, and green colors of a traffic signal cannot be patented. The manual allows patents for unique aspects of technologies used in a sign (such as the specific design of a retroreflective coating on the sign so it can be more easily seen at night), a more durable material from which the signing could be made, or the internal workings of a traffic signal.

[29]This number is likely an undercount of patents for inventions developed with federal funding. As discussed in our prior work, not all such patents disclose federal funding fully and correctly; see GAO‑23‑105656 and GAO‑24‑107061.

[30]Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, “How Many Patents Does It Take to Make a Drug? Follow-On Pharmaceutical Patents and University Licensing,” Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review, vol. 17, 299 (2010). The study analyzed patents associated with chemical (small molecule) drugs.

[31]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Beyond Patents: Assessing the Value and Impact of Research Investments: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (Washington, D.C.: October 2017).

[32]David Argente, Salomé Baslandze, Douglas Hanley, and Sara Moreira, “Patents to Products: Product Innovation and Firm Dynamics,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper 2020-4 (April 2020).

[33]National Academies, Beyond Patents.

[34]The studies are limited to chemical (small molecule) drugs.

[35]Congressional Research Service, “Memorandum: FDA Orange Book Patents with Government Interest Statements” (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2024).

[36]Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, An Examination of March-in Rights and Drug Products with Government-Interest Patents (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 20, 2024). The study defined a drug at the ingredient level and a drug product at the level of ingredient strength, dosage form, and route of administration. For example, a 10-milligram tablet and a 15-milliliter vial of the same drug would represent one drug but two drug products.

[37]Lisa Larrimore Ouellette and Bhaven N. Sampat, “Using Bayh-Dole Act March-In Rights to Lower U.S. Drug Prices,” JAMA Health Forum, vol. 5 (2024).

[38]The authors defined a new drug as a new molecular entity (NME). An NME contains an active moiety (the core molecule or ion responsible for the physiological or pharmacological action of a drug substance) that FDA has not previously approved. Not all FDA-approved drugs are NMEs.

[39]The RFI on the draft guidance was published in 88 Fed. Reg. 85593 (Dec. 8, 2023).

[40]For more information about these earlier efforts, see app. II.

[41]Regulations.gov, Docket NIST-2023-0008. The docket indicates that 51,873 comments were submitted, but only 51,845 were posted and available for downloading.