SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY

Actions Needed to Improve CBP Management of the Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Program

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Heather MacLeod at MacLeodH@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has implemented the Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) program as part of a layered, risk-informed approach to supply chain security. CTPAT provides private companies in the supply chain with certain benefits (e.g., reduced cargo inspections or expedited processing) in exchange for voluntary adherence to additional security requirements. CBP monitors CTPAT participants’ involvement in security incidents, such as smuggling cargo that contains narcotics, which could result in participants’ suspension or removal from the program.

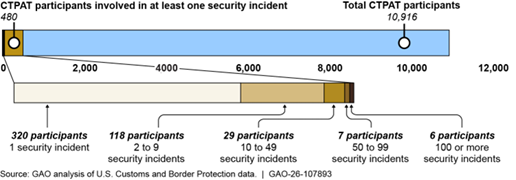

According to CBP data, about 4 percent of CTPAT program participants were involved in one or more security incidents. Specifically, 480 CTPAT program participants were involved in approximately 2,200 security incidents (about 1 percent of all incidents) in the cargo supply chain in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. The most common type of security incident that participants were involved in were drug-related, accounting for just under 50 percent of all incidents. However, CBP does not collect complete data on security incidents involving program participants, such as on incidents self-reported by participants. Ensuring data on CTPAT security incidents are complete and consistent would position CBP to better identify and understand possible risks to the cargo supply chain.

Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Involvement in Security Incidents That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain, Fiscal Years 2020-2024

Note: These data are estimates. While GAO determined that these data are sufficiently reliable to report approximate numbers, limitations in these data exist. For more details, see GAO-26-107893. The total number of CTPAT participants is as of August 2025.

CBP did not consistently investigate security incidents involving CTPAT participants or take enforcement actions against them. For example, GAO found several cases where CBP documented that they would not investigate a security incident involving a program participant and did not take enforcement action against them, but did not explain these decisions. In one instance, CBP did not take enforcement action against a participant involved in a security incident in 2021. This same participant was subsequently involved in dozens of additional incidents before it was suspended 2 years later. Without clear, documented decision criteria to determine appropriate enforcement actions against CTPAT participants involved in security incidents, CBP risks leaving the nation and supply chain vulnerable to additional security incidents.

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. economy depends on the quick and efficient flow of millions of tons of cargo each day throughout the global supply chain. However, U.S.-bound cargo can present security concerns, as there is a risk that terrorists could use cargo shipments to transport a weapon of mass destruction or other contraband into the U.S.

The Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Pilot Program Act of 2023 includes a provision for GAO to assess the effectiveness of the program. This report examines (1) the number and types of security incidents that occurred in the cargo supply chain in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 and the extent to which CTPAT participants were involved; (2) enforcement actions against CTPAT participants involved in security incidents during this timeframe; and (3) the extent to which CBP meets certain statutory requirements in its management of the CTPAT program.

GAO analyzed CBP data on CTPAT participant involvement in security incidents and CTPAT’s enforcement actions against these participants in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. GAO also reviewed CBP procedures for addressing program participant involvement in security incidents and interviewed CBP headquarters officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to CBP, including to improve the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of the CTPAT program’s data and update guidance to include clear, documented decision criteria for determining enforcement actions against CTPAT participants involved in security incidents. The Department of Homeland Security concurred with our recommendations.

Abbreviations

CBP U.S. Customs and Border Protection

CTPAT Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism

DHS Department of Homeland Security

FY Fiscal year

SAFE Port Act Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 27, 2026

Congressional Committees

The U.S. economy depends on the quick and efficient flow of millions of tons of cargo each day throughout the global supply chain—the flow of goods from manufacturers to retailers or other end users. Within the federal government, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is responsible for administering cargo security and reducing the vulnerabilities associated with the supply chain, while facilitating the flow of legitimate commerce.

However, U.S.-bound cargo can present security concerns, as there is a risk that terrorists could use cargo shipments to transport a weapon of mass destruction or other contraband into the United States. Such attacks using cargo shipments could cause disruptions to the supply chain and limit global economic growth and productivity.

CBP has implemented several programs as part of a layered, risk-informed approach to supply chain security. The Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006 (SAFE Port Act) established programs within CBP, which the agency considers key to its layered security strategy.[1] One such program, the Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT), began in November 2001 and is a voluntary program in which CBP officials work with private companies—such as air and sea carriers—to review and validate their supply chain security practices.[2] They also review the security practices of companies or entities in their global supply chains. This is to ensure they meet a set of minimum security criteria defined by CBP. In return, CTPAT participants are eligible to receive various benefits, such as reduced scrutiny or expedited processing of their U.S.-bound shipments. The CTPAT program reported that its participants accounted for over 51 percent (by value) of cargo imported into the United States in fiscal year 2023.

The Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Pilot Program Act of 2023 includes a provision for GAO to analyze security incidents in the cargo supply chain, whether these incidents involved CTPAT participants, whether these participants were suspended or removed, and the effectiveness of the program.[3] This report addresses the following:

1) What CBP data show about the number and types of security incidents that occurred in the cargo supply chain from fiscal years 2020 through 2024 and the extent to which CTPAT participants were involved.

2) What CBP data show about program actions taken to suspend, remove, or maintain the status of those CTPAT participants, if any, involved in security incidents during this timeframe.

3) The extent to which CBP meets certain statutory requirements in the SAFE Port Act in its management of the CTPAT program.

To address our first objective, we analyzed CBP record-level data from SEACATS—the official CBP system of record for tracking seized property, including drugs, and processing seizures—for fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to determine the number of security incidents that occurred in the cargo supply chain.[4] To assess the reliability of CBP’s data from SEACATS, we performed electronic testing of variables for missing values and duplicates; reviewed related documentation to understand how the data were entered; and interviewed officials knowledgeable about the data to identify data challenges and limitations, if any. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting the number of security incidents that occurred in the cargo supply chain in fiscal years 2020 to 2024.

Additionally, we analyzed CBP data on CTPAT participants involved in security incidents for fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Specifically, we produced summary statistics on CTPAT participants involved in security incidents during this timeframe by using statistical software to analyze the record-level data. To inform our analysis, we reviewed CBP’s procedures for CTPAT personnel conducting daily reviews of security incidents to identify program participant involvement, and the processes for logging these data.[5] We also interviewed CBP officials in headquarters on CTPAT’s processes for identifying security incidents, recording this information, and any efforts to synthesize and analyze data on participant involvement in security incidents.

To assess the reliability of CBP’s data on security incidents involving CTPAT participants, we performed electronic testing of variables for obvious errors in accuracy and consistency, reviewed related documentation, and interviewed knowledgeable agency officials. We determined that these data are sufficiently reliable to report approximate numbers of security incidents involving CTPAT participants, despite limitations that we address in the report. We assessed the completeness of these data and the program efforts to collect and analyze data against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[6]

To address our second objective, we analyzed CBP data from the CTPAT Portal on its enforcement actions (suspensions and removals) against CTPAT participants involved in security incidents for fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Specifically, we produced summary statistics on CBP enforcement actions during this time frame by using statistical software to analyze the record-level data on suspensions and removals. To inform our analysis, we reviewed CBP procedure documents on addressing CTPAT participant involvement in security incidents. We also interviewed CBP officials in headquarters to learn about CTPAT’s process for addressing program participant involvement in security incidents. We assessed the CTPAT program’s processes and criteria for taking enforcement actions against program participants involved in security incidents against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[7]

To assess the reliability of CBP data from the CTPAT Portal on CBP’s enforcement actions against CTPAT participants involved in security incidents, we analyzed the record-level data using statistical software to check for obvious errors, duplicates, inconsistencies or inaccuracies, and illogical values. We also interviewed officials knowledgeable about these data to identify data challenges and limitations, if any. Through our analysis and interviews with officials, we identified limitations with the CBP data from the CTPAT Portal on its enforcement actions and determined the data were not sufficiently reliable for our intended purposes. CBP officials confirmed these data limitations, which impacted the accuracy and consistency of the data and subsequently prevented us from using them in this report to address our researchable objective. As such, we include information on these limitations in our findings.

To address our third objective, we analyzed CBP documentation and information on its efforts to manage the CTPAT program pursuant to certain statutory requirements in the SAFE Port Act.[8] Specifically, we analyzed CBP documentation and information on (1) its efforts to review and update the CTPAT program’s minimum security requirements; (2) CTPAT’s annual plan for fiscal year 2025; and (3) its efforts to develop a 5-year strategic plan for the CTPAT program. We also interviewed CBP officials knowledgeable about these efforts to discuss the extent to which CBP’s efforts met these statutory requirements. For example, we interviewed CTPAT officials to discuss the details in the program’s annual plan to determine whether the plan included sufficient information on its needed resources to address the program’s projected workload. We evaluated CBP’s efforts to meet the statutory requirement for an annual plan against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and key performance management practices identified in our prior work.[9] Additional details regarding our objectives, scope, and methodology are provided in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

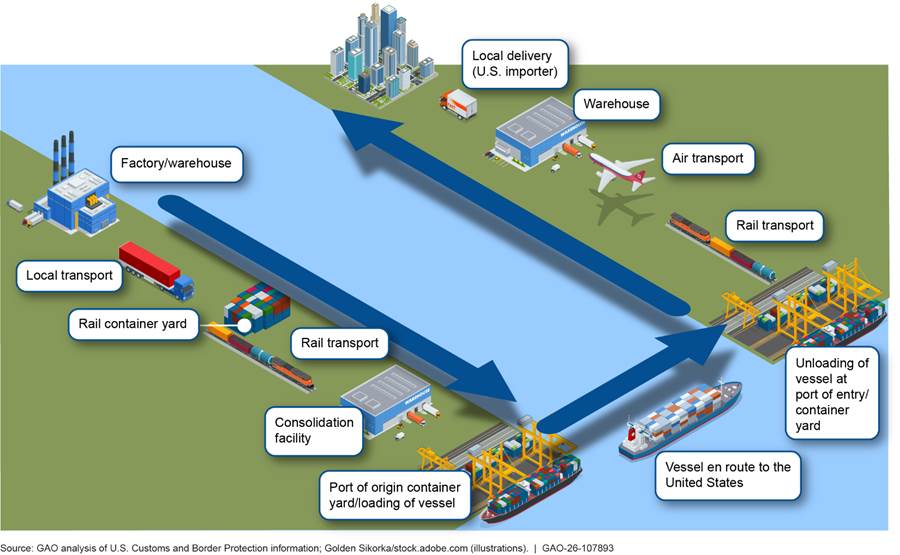

Overview of Key Points in the Global Cargo Supply Chain

The global supply chain consists of multiple key points of transfer from the time that a shipment is loaded with goods at a foreign factory to when it arrives at a U.S. port and ultimately is delivered to the end user. For example, air cargo’s movement depends on warehouses, trucks, roadways, and other ground-based infrastructure at and around airports, while transporting a shipping container involves many different participants and many points of transfer, such as facilities, vessels, and infrastructure within seaports.[10] In the post-9/11 environment, the movement of cargo shipments throughout the global supply chain is inherently vulnerable to terrorist actions. Every time responsibility for cargo shipments changes hands along the global supply chain, there is the potential for a security breach. For example, the cargo in a shipping container can be affected not only by the manufacturer or supplier of the material being shipped, but also by carriers who are responsible for getting the material to a port and by personnel who load containers onto the ships. Thus, vulnerabilities exist that terrorists could exploit by, for example, placing a weapon of mass destruction into a container for shipment to the United States or elsewhere. See figure 1 for an example of the global supply chain.

CTPAT Program Overview

CBP first established the CTPAT program in 2001, and the SAFE Port Act later codified the program in 2006.[11] CTPAT is a voluntary public-private partnership program that CBP leads to strengthen and improve security practices and overall standards of the supply chain, including in U.S. border security. The CTPAT program uses a risk management approach that allows CBP to provide participants certified as low-risk with reduced cargo inspections or expedited processing at the U.S. border. This risk-based approach enables CBP to focus its cargo targeting and examination resources on companies and imports that may be higher-risk or have unknown risk. The CTPAT program’s budget has been $40.5 million each fiscal year from 2020 to 2025. See table 1 for the types of entities eligible for the CTPAT program.

Table 1: Types of Entities Eligible for Participation in the Customs Trade Partnership Program Against Terrorism Program and Their Role in the Supply Chain

|

Entities |

Role in the supply chain |

|

Air/rail/sea carriers |

Carriers transport cargo from foreign nations into the United States via air, rail, or sea. |

|

Border highway carriers (U.S./Canada or U.S./Mexico) |

Highway carriers transport cargo for scheduled and unscheduled operations via road across the Canadian and Mexican borders. |

|

Consolidators |

Consolidators combine or coordinate cargo from a number of shippers that will deliver the goods to several buyers. |

|

Exporters |

Entities that actively export cargo from the United States to another country. |

|

Foreign manufacturers |

Entities located in Canada or Mexico that produce goods for sale to the United States. |

|

Importers |

During trade, importers bring articles of trade from a foreign source into a domestic market. |

|

Licensed U.S. customs brokers |

Entities that are licensed, regulated, and empowered by United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to assist importers and exporters in meeting federal requirements. Brokers submit necessary information and appropriate payments to CBP on behalf of clients and have expertise in the entry procedures, admissibility requirements, and the rates of duty, among other things for imported merchandise. |

|

Mexican long-haul highway carriers |

Companies that haul cargo within Mexico destined for the United States, but do not cross the U.S./Mexico border. |

|

Third party logistics providers |

Outsourced services that typically include integrated warehousing, transportation services, and customs and freight consolidation. |

|

U.S. or foreign-based marine port or terminal operators |

Port authorities are entities of state or local governments that own, operate, or otherwise provide wharf, dock, and other marine terminal investments at ports. This may include overseeing and unloading cargo from the ship to dock and checking the ship’s manifest against the ship’s actual cargo, documents authorizing a truck to pick up cargo, and overseeing the loading and unloading of railroad cars. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection information and 6 U.S.C. § 962. | GAO‑26‑107893

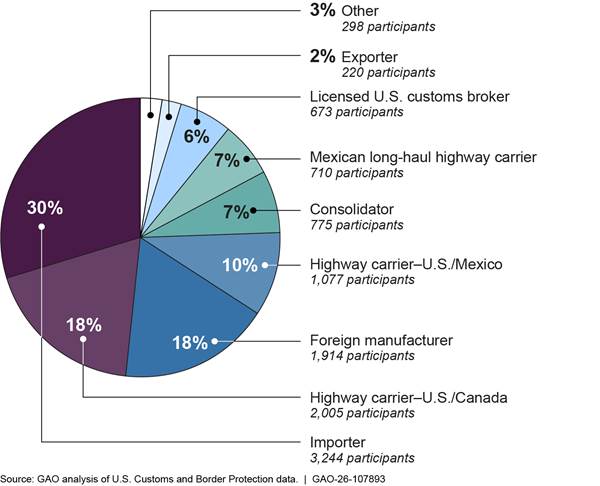

According to CBP officials, as of August 2025, the CTPAT program had almost 11,000 participants. Importers, representing 30 percent of all CTPAT participants, were the largest group, followed by U.S./Canada Highway Carriers and foreign manufacturers each representing 18 percent of the CTPAT program’s participants. The remaining 34 percent of CTPAT participants were distributed among other entities, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Number and Percentage of Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism Participants by Entity Type, as of August 2025

Note: “Other” entity types are (1) air carriers, (2) U.S. or foreign-based marine port terminal operators, (3) rail carriers, (4) sea carriers, and (5) third party logistics providers. Each of these other entity types individually represent about one percent or less of total participants. The percentages do not add up to 100 because of rounding.

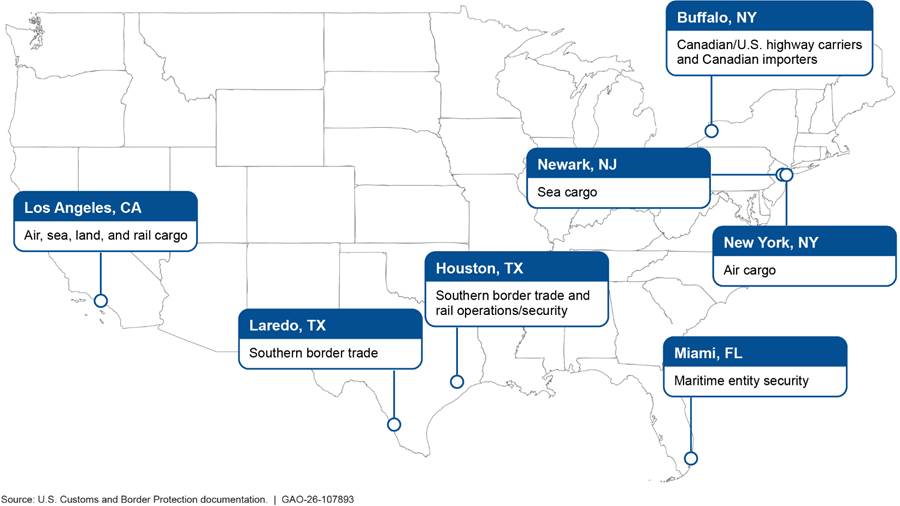

As of July 2025, CBP employed 157 personnel across the CTPAT program’s headquarters and seven field office locations.[12] Specifically, these CTPAT personnel operate from the program’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., and seven field offices located in the United States: Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; Newark, New Jersey; Buffalo and New York, New York; Houston, Texas; and Laredo, Texas. Each field office has a specific trade focus. For example, the Laredo, Texas field office focuses on southern border trade while the Newark, New Jersey field office focuses on sea containers. See figure 3 for more information on each field office’s trade focus.

CTPAT Program Validations of Participant Security Practices

Through the CTPAT program, CBP partners with private entities to review and validate supply chain security practices—both their own and those of entities in their global supply chains. This validation ensures compliance with minimum security criteria established by the program. The minimum security criteria help CTPAT participants develop effective security practices tailored to their industry. For example, sea carrier vessels must undergo third-party audits of their security practices for high-risk maritime routes at least five times a year. Air carriers with passenger flights carrying cargo must develop risk-based written policies and procedures that include more intrusive examination of the cargo, such as X-ray inspections. See table 2 for more information on the CTPAT program’s minimum security criteria.

Table 2: Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Minimum Security Criteria for Program Participants

|

Minimum security criteria |

Example of minimum security criteria |

|

Security vision and responsibility |

The participant’s CTPAT point(s) of contact must be knowledgeable about program requirements and provide regular updates to upper management on issues such as the progress or outcomes of any audits and CTPAT validations. |

|

Risk assessment |

CTPAT participants must conduct an overall risk assessment to identify where security vulnerabilities may exist and document this. |

|

Business partner requirements |

CTPAT participants must have a written, risk-based process for screening new participants and for monitoring current participants, including checks on activity related to money laundering and terrorist funding. |

|

Cybersecurity |

CTPAT participants using network systems must regularly test the security of their information technology infrastructure. If vulnerabilities are found, corrective actions must be implemented as soon as feasible. |

|

Conveyance and instruments of international traffic security |

The CTPAT inspection process must have written procedures for both security and agricultural inspections. |

|

Seal security |

CTPAT participants must have detailed, written high-security seal procedures that describe how seals are issued and controlled at the facility and during transit. |

|

Procedural security |

CTPAT participants must initiate their own internal investigations of any security-related incidents immediately after becoming aware of the incident. |

|

Agricultural security |

CTPAT participants must have written procedures designed to prevent visible pest contamination to include compliance with certain regulations. |

|

Physical security |

All cargo handling and storage facilities, including trailer yards and offices must have physical barriers and/or deterrents that prevent unauthorized access. |

|

Physical access controls |

CTPAT participants must have written procedures governing how identification badges and access devices are granted, changed, and removed. |

|

Personnel security |

Written processes must be in place to screen prospective employees and to periodically check current employees. |

|

Education, training, and awareness |

Personnel must be trained on how to report security incidents and suspicious activities. |

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection documentation. | GAO‑26‑107893

The CTPAT program follows a multistep process, led by its supply chain security specialists, to certify entities as program participants and to validate their supply chain security practices. As part of the vetting process, the applicant submits documentation of their compliance with the CTPAT program’s minimum security criteria. The CTPAT program’s supply chain security specialists review the information provided to vet the applicant before being accepted into the CTPAT program.

The CTPAT program designates its participants into one of three tier levels representing the participant’s status and implementation of minimum security criteria:[13]

· Tier 1: Certified. Upon entry into the CTPAT program participants are granted certified status, which means that the participants are conditionally entitled to program benefits.

· Tier 2: Validated. CTPAT participants whose supply chain practices have been validated by CTPAT supply chain security specialists are subsequently granted validated status. This means that the CTPAT program found that the participants met minimum security criteria.[14]

· Tier 3: Exceeding. CTPAT participants are granted exceeding status when the CTPAT program found that participants employ security practices that exceed minimum security requirements.[15]

In exchange for allowing CTPAT program personnel to review and validate their supply chain security practices, CTPAT participants become eligible to receive benefits. According to CBP, these benefits can include (1) reduced CBP cargo examination rates, (2) use of Advance Qualified Unlading Approval lanes (also known as AQUA lanes) for expedited unloading of vessel cargo at U.S. seaports, (3) access to Free and Secure Trade lanes (also known as FAST lanes) for faster processing of cargo at U.S. land ports, (4) reciprocal benefits in other countries, and 5) access to local supply chain security specialists who have knowledge of border operations and regional trade threats.[16]

As the CTPAT tier level increases, CBP may reduce the risk score—which is the result of a set of rules CBP applies in assessing the risk level for each arriving cargo shipment—associated with cargo shipments in its Automated Targeting System, which is a web-based decision support system.[17] CBP uses the Automated Targeting System risk score to identify potentially high-risk cargo for increased inspection, and a lower risk score generally reduces the likelihood that a CTPAT participant’s cargo will be examined upon entering U.S. ports.[18]

In 2017, we reported that the CTPAT program faced challenges in meeting its security validation responsibilities due to technical issues with the program’s data management system and limitations in CBP’s ability to determine the extent to which program participants were receiving benefits because of data problems. We recommended, among other things, that CBP develop standardized guidance for field offices regarding the tracking of information on security validations. CBP has taken actions to fully address these recommendations.[19]

CTPAT Program Identification of Participant Involvement in Security Incidents

According to CTPAT program guidance, CTPAT program personnel are responsible for identifying and addressing any security incidents that involve program participants. Specifically, they investigate, and if needed, take enforcement actions, which could include suspending or removing the participant entity from the CTPAT program. These security incidents may include the introduction of restricted, prohibited, or otherwise harmful cargo or individuals into the supply chain, which are in violation of laws and regulations enforced by CBP, or the laws and regulations enforced by other domestic or foreign government agencies. Examples of such security incidents can include a CTPAT participant not adhering to minimum security criteria, which could lead to (1) the introduction of cargo that contains narcotics (e.g., marijuana or fentanyl), weapons, or goods with trademark violations, or (2) trafficking individuals across U.S. borders at various points in the global supply chain.

According to CBP officials, CTPAT program personnel could become aware of CTPAT participant involvement in security incidents in several ways. Primarily, CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office conduct a daily review of information contained in CBP’s SEACATS system—the official CBP system of record for tracking seized property, including drugs, and processing seizures—to identify any security incidents involving CTPAT participants.[20] CTPAT personnel review security incidents from the prior 24 hours and conduct individual searches by specific modes of transportation—such as commercial air carrier and rail carrier—identified by CTPAT procedures.[21] Alternatively, according to CBP officials, CTPAT participants can self-report security incidents to the program or CTPAT supply chain security specialists located at the program’s field offices may also identify potential security incidents. According to CBP officials, these types of incidents are then entered into the CTPAT program’s information-sharing and data management system, the CTPAT Portal.[22]

According to program guidance, once headquarters CTPAT program personnel identify a security incident involving a CTPAT participant, they must enter this information into an incident log spreadsheet maintained by headquarters. Further, program guidance states that once personnel log this information, they report this information to program supervisors and CTPAT leadership.

When a security incident occurs in a participant’s supply chain, CTPAT supply chain security specialists are to conduct a review of the incident, which may include requesting information and documentation related to the incident, according to program documentation. In addition, CTPAT program personnel might conduct an onsite visit to observe the CTPAT participant’s activities and supply chain security practices. Further, according to CBP officials, CTPAT program personnel are to record key information from this review into the CTPAT Portal. Specifically, personnel record this information as narrative entries within the CTPAT Portal, which is used to document the steps the supply chain security specialists have taken to investigate and address security incidents, according to CBP officials.

CTPAT Participants Were Involved in a Small Share of Security Incidents, But CBP Data are Incomplete

Approximately 215,000 Security Incidents Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain in Fiscal Years 2020–2024

According to our analysis of CBP’s SEACATS data, approximately 215,000 security incidents occurred in the cargo supply chain in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Most security incidents involved express consignment carriers (81 percent) and commercial air carriers (10 percent).[23] See table 3 for security incidents by entity type recorded by CBP in fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Table 3: Security Incidents Recorded by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain, by Entity Type, Fiscal Years (FY) 2020–2024

|

Entity type |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

FY2022 |

FY2023 |

FY2024 |

Total |

|

Express consignment |

36,338 |

39,761 |

33,189 |

31,410 |

33,274 |

173,972 |

|

Commercial air carrier |

4,050 |

3,718 |

2,777 |

3,118 |

7,973 |

21,636 |

|

Commercial sea carrier |

1,821 |

2,217 |

2,137 |

2,170 |

2,351 |

10,696 |

|

Commercial truck carrier |

1,066 |

1,361 |

808 |

666 |

574 |

4,475 |

|

Other |

751 |

569 |

364 |

275 |

757 |

2,716 |

|

Auto |

231 |

176 |

154 |

115 |

185 |

861 |

|

Train |

52 |

71 |

58 |

61 |

81 |

323 |

|

Truck |

34 |

55 |

42 |

32 |

23 |

186 |

|

Bus |

6 |

6 |

12 |

11 |

6 |

41 |

|

Van |

5 |

7 |

5 |

15 |

3 |

35 |

|

Total |

44,354 |

47,941 |

39,546 |

37,873 |

45,227 |

214,941 |

Source: GAO analysis of CBP data. | GAO‑26‑107893

Note: An express consignment carrier is an entity operating in any mode or intermodally moving cargo by special express commercial service under closely integrated administrative control. Its services are offered to the public under advertised, reliable timely delivery on a door-to-door basis. An express consignment operator assumes liability to Customs for the articles in the same manner as if it is the sole carrier. 19 C.F.R. § 128.1(a).

Two thirds of security incidents in the cargo supply chain during this time involved counterfeit goods and drugs.[24] Specifically, counterfeit goods accounted for 39 percent of the security incidents, and drugs accounted for 27 percent of security incidents, collectively accounting for 66 percent of security incidents within the cargo supply chain.[25] Further, security incidents involving currency had the largest proportional decrease in security incidents, while arms, ammunition, and explosives had the largest proportional increase in security incidents during this time. See table 4 for more information on the types of security incidents that occurred during the period of our review.

Table 4: Security Incidents Recorded by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain by Incident Type, Fiscal Years (FY) 2020–2024

|

Incident type |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

FY2022 |

FY2023 |

FY2024 |

Total |

|

Counterfeit goodsa |

22,757 |

21,079 |

18,994 |

13,710 |

14,929 |

91,469 |

|

Drugsb |

10,349 |

11,778 |

10,084 |

13,576 |

17,585 |

63,372 |

|

Prohibited itemsc |

7,185 |

9,926 |

6,589 |

5,454 |

6,697 |

35,851 |

|

General merchandised |

5,994 |

6,771 |

5,278 |

5,427 |

4,557 |

28,027 |

|

Arms, ammunition, explosivese |

663 |

1,589 |

697 |

1,058 |

2,522 |

6,529 |

|

Otherf |

885 |

969 |

1,047 |

1,237 |

1,300 |

5,438 |

|

Currency |

300 |

324 |

175 |

234 |

183 |

1,216 |

|

Total |

48,133 |

52,436 |

42,864 |

40,696 |

47,773 |

231,902 |

Source: GAO analysis of CBP data. | GAO‑26‑107893

Note: The number of incident types is larger than the total number of security incidents because an individual security incident could have more than one incident type. For example, one security incident could involve both drugs and general merchandise. CBP established and defines these categories of incident types.

aA “counterfeit” is a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark. 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

bAccording to CBP’s Seized Assets Management and Enforcement Procedures Handbook, the category “drug” includes seizures of any form of controlled substance, whether prohibited, prescription, or over the counter.

cAccording to CBP officials, prohibited items includes items that can be labelled as prohibited and not safe between borders such as live animals, Cuban cigars, and fireworks.

dThe general merchandise category was originally called “general MDs.” According to CBP officials, this category includes general merchandise that is not categorized as one of the other property categories that CBP uses.

eWe combined two categories in the SEACATS database for the arms, ammunition, explosives incident type, which includes arms (low risk) and arms/ammo/explosives (high risk). According to CBP officials, the low-risk arms category includes items that are related to weapons but are not innately dangerous on its own. This includes bullet proof vests, magazines, and attachments for weaponry. The high-risk arms category includes actual weapons, such as guns and grenades, or ammunition used in weapons.

fWe combined four categories that CBP established into the “other” category, which includes aircraft, computers, vehicles, and vessels. CBP has the authority to seize conveyances–such as vehicles and vessels—if the conveyance has been or is being used in the commission of certain offenses, including by any person who, “knowing that a person is an alien, brings in or attempts the bring to the United States in any manner whatsoever such person at a place other than a designated port of entry or place.” 8 U.S.C. § 1324(b).

About 1 Percent of Security Incidents in the Cargo Supply Chain in Fiscal Years 2020–2024 Involved CTPAT Participants

According to our analysis of available CBP data on CTPAT security incidents, about 1 percent of security incidents in the cargo supply chain that occurred in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 involved CTPAT participants. Specifically, we found that 480 CTPAT participants were involved in an estimated 2,200 security incidents from fiscal years 2020 to 2024.[26] Of the 480 CTPAT participants involved in security incidents, licensed U.S. customs brokers and highway carriers accounted for the largest number of participants involved, totaling about 59 percent. See table 5 for a breakdown of the entity type of each participant that was involved in a security incident.

Table 5: Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Involvement in Security Incidents That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain by Entity Type, Fiscal Years 2020–2024

|

Entity type |

Participants involved in security incidents |

Percentage |

|

Licensed U.S. customs broker |

153 |

31.9% |

|

Highway carrier—U.S./Canada |

71 |

14.8% |

|

Highway carrier—U.S./Mexico |

58 |

12.1% |

|

Importer |

49 |

10.2% |

|

Sea carrier |

34 |

7.1% |

|

Air carrier |

31 |

6.5% |

|

Consolidator |

31 |

6.5% |

|

Foreign manufacturer |

22 |

4.6% |

|

Rail carrier |

22 |

4.6% |

|

Mexican long-haul highway carrier |

4 |

0.8% |

|

Third-party logistics provider |

3 |

0.6% |

|

Exporter |

1 |

0.2% |

|

U.S. marine port or terminal operator |

1 |

0.2% |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. | GAO‑26‑107893

Note: The number of CTPAT participants involved in security incidents includes incidents identified by CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office. These data do not include on CTPAT participants involved in security incidents reported from program field offices or self-reported from CTPAT participants. The total of the percentages adds up to over 100 percent due to rounding.

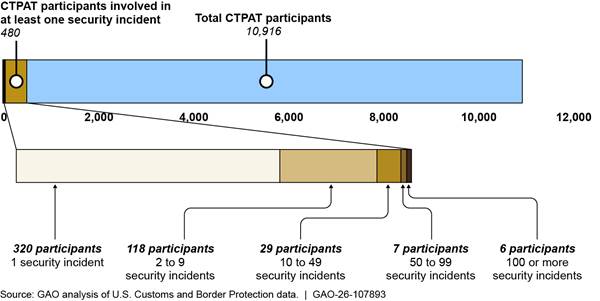

According to our analysis, of the 480 CTPAT participants identified as being involved in at least one security incident, 320 CTPAT participants (67 percent) were involved in one security incident in fiscal years 2020 through 2024. The other 160 CTPAT participants (33 percent) were involved in more than one security incident during this timeframe.[27] See figure 4 for a breakdown of the number of CTPAT participants that were involved in one or more security incidents during the period we reviewed.

Figure 4: Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Involvement in Security Incidents That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain, Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: The total number of CTPAT participants is as of August 2025. The number of CTPAT participants involved in at least one incident is a cumulation of 5 fiscal years data as of January 2025. The number of CTPAT participants involved in security incidents includes incidents identified by CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office. These data do not include information on CTPAT participants involved in security incidents reported from program field offices or self-reported from CTPAT participants.

Among the security incidents that occurred during our study time frame and that involved CTPAT participants, air carriers were involved in the highest proportion of such incidents (35 percent), followed by sea carriers (26 percent), despite these two entity types cumulatively making up less than one percent of all CTPAT participants.[28] See table 6 for more information on the number of security incidents that involved different entity types, by fiscal year in fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Table 6: Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Security Incidents That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain by Entity Type, Fiscal Years (FY) 2020–2024

|

Entity type |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

FY2022 |

FY2023 |

FY2024 |

Total |

|

Air carrier |

66 |

144 |

151 |

99 |

428 |

888 |

|

Sea carrier |

41 |

74 |

85 |

37 |

417 |

654 |

|

Licensed U.S. customs broker |

55 |

81 |

45 |

38 |

112 |

331 |

|

Highway carrier—U.S./Canada |

35 |

71 |

45 |

29 |

60 |

240 |

|

Rail carrier |

62 |

32 |

24 |

34 |

56 |

208 |

|

Highway carrier—U.S./Mexico |

22 |

26 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

66 |

|

Consolidator |

5 |

9 |

22 |

14 |

11 |

61 |

|

Importer |

14 |

17 |

13 |

5 |

12 |

61 |

|

Foreign manufacturer |

8 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

26 |

|

Third-party logistics provider |

8 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

|

Mexican long-haul highway carrier |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Exporter |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

U.S. marine port or terminal operator |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Total |

320 |

464 |

396 |

267 |

1,105 |

2,552 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. | GAO‑26‑107893

Note: The total number of security incidents for entity types is higher than the total number of security incidents because each security incident could have more than one participant—that are different entities—involved. For example, one security incident could involve a U.S./Mexico highway carrier and a licensed U.S. customs broker. The number of CTPAT participants involved in security incidents includes incidents identified by CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office. These data do not include information on CTPAT participants involved in security incidents reported from program field offices or self-reported from CTPAT participants.

|

Security Incidents Involving Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Partners According to CTPAT policy, security incidents include the introduction of restricted, prohibited, or otherwise harmful cargo or people into the supply chain, which are in violation of laws and regulations enforced by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or the laws and regulations enforced by other government agencies. Examples of security incidents involving CTPAT participants include the following: · A highway carrier transporting marijuana along the northern border. · A rail carrier transporting two people into the United States illegally along the southwest border. · A sea carrier transporting items with intellectual property rights violations at a seaport. · An air carrier transporting khat, a controlled substance, at a large international airport in the United States.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection photo by Mani Albrect. | GAO‑26‑107893 |

According to the data, the most common type of security incident that CTPAT participants were involved in was drug-related (49 percent), followed by the “other” category, which includes seizures of ammunition, weapons parts, and products violating consumer safety standards (20 percent), and intellectual property rights (16 percent).[29] Additionally, despite the number of security incidents remaining relatively stable in fiscal years 2020 through 2023, the number of security incidents involving CTPAT participants increased four-fold from fiscal year 2023 to fiscal year 2024. According to CBP officials, around this time, the CTPAT program began capturing data on security incidents involving fentanyl precursor chemicals and seizures with small trademark violations, leading to the increase in recorded security incidents. See table 7 for more information on the type of security incidents CTPAT participants were involved in.

Table 7: Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Security Incidents That Occurred in the Cargo Supply Chain by Incident Type, Fiscal Years (FY) 2020–2024

|

Incident Type |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

FY2022 |

FY2023 |

FY2024 |

Total |

|

Drugs |

210 |

355 |

258 |

200 |

99 |

1,122 |

|

Other |

1 |

8 |

56 |

16 |

371 |

452 |

|

Intellectual property rights |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

374 |

376 |

|

Entry without inspection |

45 |

13 |

7 |

15 |

32 |

112 |

|

Prescription medication |

1 |

3 |

21 |

12 |

57 |

94 |

|

Over the counter medications |

1 |

0 |

7 |

1 |

73 |

82 |

|

No category identified |

0 |

10 |

15 |

1 |

20 |

46 |

|

Identity documents |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

13 |

|

De minimisa |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

|

Total |

258 |

389 |

366 |

245 |

1,043 |

2,301 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. | GAO‑26‑107893

Note: CBP established these categories of incident types. The total number for incident types is higher than the total number of security incidents because each security incident could be more than one incident type. For example, one security incident could involve both intellectual property rights and over the counter medication. The number of security incidents includes incidents identified by CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office, with no information from field offices or self-reported from CTPAT participants.

aDe minimis refers to a duty exemption for certain low-value shipments entering the U.S. During the time frame covered by this table, goods valued at 800 dollars or less could enter the country without paying duties or certain taxes. See 19 U.S.C. § 1321(a)(2)(C). Since 2025, except for certain shipments of articles, the de minimus exemption has been suspended by Executive Order. Suspending Duty-Free De Minimis Treatment for All Countries, Exec. Order 14,324, 90 Fed. Reg. 37,775 (Aug. 5, 2025).

CBP Does Not Have Complete Data on Security Incidents Involving CTPAT Participants Due to Inconsistent Records and Missing Field-Based Information

Though our analysis of available CBP data on CTPAT security incidents shows that CTPAT participants were involved in an estimated 2,200 security incidents in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, the CTPAT program may not be able to accurately determine the total number of security incidents involving CTPAT participants because of incomplete data. Specifically, we analyzed data provided by CBP on security incidents involving CTPAT participants that occurred during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to determine the incident type, CTPAT participant entity type, locations where the security incidents occurred, and the frequency of CTPAT participants’ involvement in security incidents, among other things. In conducting this analysis, we found that data were (1) inconsistent or incomplete; (2) only included security incidents identified by CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office, with no information from field offices or self-reported from participants; and (3) the method of recording security incidents creates a risk of duplicate entries depending on how the information was entered.

Inconsistent and incomplete data entries. According to CTPAT program policy, if CTPAT program personnel identify a CTPAT participant’s involvement in a security incident, they are to record information about the incident, such as the location where the security incident occurred, in the CTPAT program’s incident log spreadsheet. To do so, according to CBP officials, CTPAT program personnel located at the headquarters office manually record information observed in CBP’s SEACATS system on each security incident involving CTPAT participants into the CTPAT program’s incident log spreadsheet. This process of manually recording data increases the potential for user error and the likelihood of inconsistent and incomplete data entries as a result. For example, we found that the data sourced from CTPAT’s security incidents log contained inconsistent location names. Specifically, in conducting our data analysis, we observed several spelling iterations and misspellings of locations, including locations with large ports such as Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; and Houston, Texas.

Several locations serve as ports with multiple modes of transit, but the records we reviewed did not sufficiently specify the mode of cargo conveyance relevant to the security incident identified. Without this information, it would be difficult for CTPAT program personnel to effectively conduct further analysis of locations and mode of transport where security incidents might be occurring. For example, Newark, New Jersey has both an air and seaport. While we observed nine records in the data provided by CBP that specify whether the identified security incident occurred at the airport or seaport, we separately observed another 323 records that did not include this information, listed the incorrect state, or were misspelled.

Further, we observed several data fields that did not have complete entries. For example, we found 35 records that were missing information on the location of the security incident identified, 83 records that were missing information on the type of security incident identified, and 1,493 records (39 percent of the data) that were missing a description of the commodity seized in the security incident, such as the type of drug or good seized.

Missing field-based information. Based on our analysis, we found the data provided by CBP only reflect security incidents collected by CTPAT program personnel located at the program’s headquarters office. The CTPAT program does not systematically collect or analyze information on security incidents identified by CTPAT supply chain security specialists located in field offices or that are self-reported by CTPAT participants. According to CBP officials, the data that were provided to us came from the CTPAT program’s incident log spreadsheet maintained by headquarters personnel, who use to it document security incidents they observe in CBP’s SEACATS system involving CTPAT participants.

CBP officials further explained that the information on security incidents identified by CTPAT field offices or self-reported by CTPAT participants are separately captured in the CTPAT Portal as narrative entries and are not included in the incident log spreadsheet maintained by the program’s headquarters office. When asked about the frequency of security incidents that are reported by CTPAT personnel located in the field or self-reported by CTPAT participants, the CTPAT Acting Director stated that, to his knowledge, self-reported incidents do not occur often. Other CBP officials we interviewed similarly could not provide a response or supporting information on the number of such security incidents that are identified in the field.

According to CBP officials, the CTPAT program does not document security incidents identified in the field or self-reported by CTPAT participants in the headquarters incident log spreadsheet because the CTPAT program’s approach is intended to be “top-down.” This means that headquarters personnel are responsible for daily screening of SEACATS and other sources of information on security incidents. Subsequently, they share information with personnel located in field offices for further research and investigation. Further, CBP officials stated that the CTPAT program’s field offices are separately responsible for managing self-reported security incidents from CTPAT participants.

Method of recording incidents. Our analysis of the data shows that the CTPAT program records information on security incidents based on each violation and identification of each CTPAT participant that is involved, which could lead to overcounting if multiple violations and CTPAT participants were involved in a single security incident. According to CTPAT program officials and procedures, CTPAT personnel are instructed to record a separate entry for each CTPAT participant involved in a security incident.

In cases with multiple CTPAT participants involved in a single security incident, program personnel are expected to record information in the headquarters incident log spreadsheet. When doing so, CTPAT personnel are to enter a commodity quantity for only one CTPAT participant and list a commodity quantity of zero for the other participants involved. For example, if two participants are involved in a seizure of 500 grams of marijuana, personnel are to enter 500 for the commodity quantity for one participant in the incident log and enter 0 for the other participant.

When reviewing the data, we also found several entries with identical dates, locations, incident types, and amounts seized, among other fields, but listed different CTPAT participants, which does not follow the CTPAT program’s procedure for recording incidents. For example, in four entries with the same date, location, amount seized, and type of narcotics seized, each entry listed a different CTPAT participant. When asked, CBP officials acknowledged that such entries could represent the same security incident despite being logged as multiple entries. Officials also said that the entries may represent when CTPAT personnel initiate an investigation, and all participants are recorded as being part of a security incident before the program conducts their investigation and determines which participant is culpable. Further, there were several records that were identical except for the trade sector designation. According to CBP officials, participants can have both a Trade Compliance and Security trade sector designation. As a result, duplicate entries with differing trade sectors may still represent one security incident.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that agency managers should use quality information to support internal control activities because reliable information is vital for the agency to achieve its mission and objectives.[30] In doing so, managers should design systems to obtain, store, and analyze reliable information in accordance with the agency’s objectives. Inconsistent and incomplete data entries could lead to CTPAT personnel missing out on key trends or circumstances related to security incidents, such as the types of commodities being smuggled, the modalities involved, and locations of security incidents. Furthermore, the exclusion of field-reported or self-reported incidents could lead to an undercount of security incidents overall and prevent CTPAT personnel from fully analyzing data to better understand trends involving participants. Ensuring data on CTPAT security incidents are complete and consistent would position CBP to better identify and understand possible risks to the cargo supply chain.

CBP Data Show It Has Not Consistently Addressed Security Incidents, and Data on Its Enforcement Actions Are Not Sufficiently Complete or Accurate

CBP Has a Process for Investigating and Taking Enforcement Action Against CTPAT Participants Involved in Security Incidents

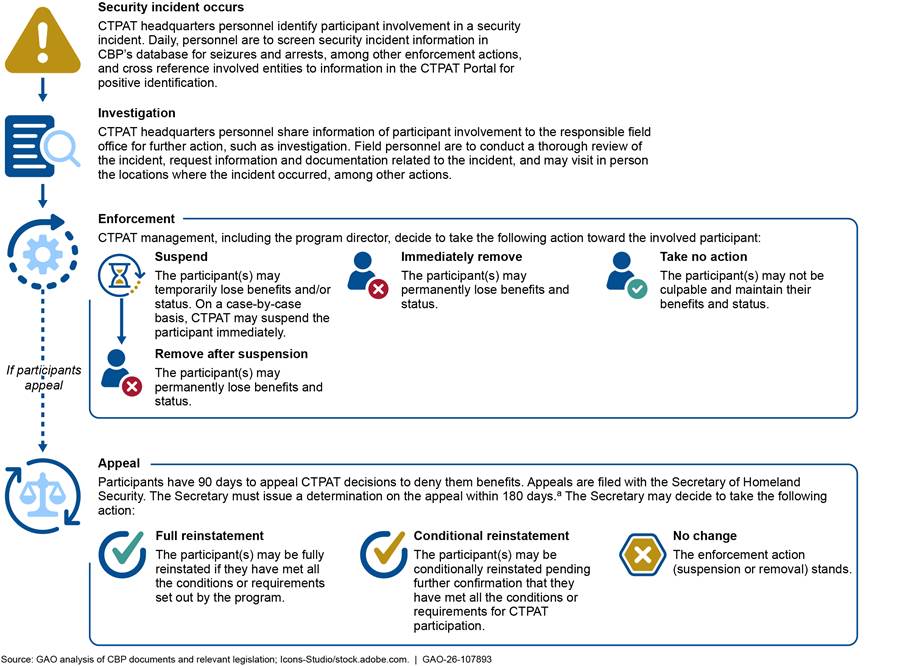

CBP developed guidance for its personnel to investigate CTPAT participants involved in security incidents and take appropriate enforcement actions against those participants. Specifically, according to CBP guidance, CTPAT program personnel are to follow a standard sequence of investigative steps for all security incidents that involve program participants—a process known as the post-incident analysis.

According to the guidance, the post-incident analysis process is intended to ensure that program personnel carry out consistent investigations and that only program participants that meet the minimum security criteria are allowed to remain in the program. Further, the guidance states that during this process, CTPAT personnel are to determine the culpability of each participant involved in a security incident and the appropriate enforcement actions (i.e., suspension or removal) for CBP to take against those program participants. In addition, CTPAT personnel are to document all investigative and enforcement actions in the program’s database, known as the CTPAT Portal. Figure 5 illustrates an overview of the post-incident analysis process.

Figure 5: Overview of U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Process for Addressing Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) Participant Involvement in Security Incidents

Note: Our analysis included CTPAT operating procedure documents and Pub. L. No. 109-347, tit. II, subtit. B, §§ 211-23, 120 Stat. 1884, 1909-15 (codified at 6 U.S.C. §§ 961-73).

a6 U.S.C. § 967(c)(1).

CBP Has Not Consistently Followed Its Guidance for Investigating CTPAT Participants Involved in Security Incidents

As we previously described, CTPAT personnel are to conduct a post-incident analysis for all program participants involved in security incidents. While our analysis shows that 480 CTPAT participants were involved in an estimated 2,200 security incidents in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, CTPAT personnel conducted a total of 35 post-incident analyses—less than 2 percent of the security incidents that occurred during that time.

According to CBP officials, program personnel only conduct post-incident analyses at the direction of program leadership. Furthermore, analyses are not done for all CTPAT participants involved in security incidents. According to CBP officials, CTPAT personnel determine whether a security incident involving a participant requires a post-incident analysis after they have reviewed additional information about the security incident. CTPAT personnel obtain the additional information from the involved participant. However, officials’ explanation of the agency’s process for conducting a post-incident analysis of security incidents involving CTPAT participants is inconsistent with CBP guidance. According to CBP guidance for conducting a post-incident analysis, program personnel are to conduct a post-incident analysis of all security incidents involving CTPAT participants, not just those incidents for which program personnel have decided warrant the additional investigative work.

In discussing the discrepancies between CBP guidance and personnel actions, CBP officials stated that the post-incident analysis guidance is outdated and, as of April 2025, CBP officials began internal conversations to plan to update the guidance to reflect their current practices. However, these officials did not provide more detailed information on specific updates to the guidance or their plans for when the updated guidance will be finalized.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, managers should implement control activities through policies. This includes management’s periodic review of policies, procedures, and related control activities for continued relevance and effectiveness in achieving the entity’s objectives or addressing related risks. For example, if there is a significant change in an entity’s process, management should review this process in a timely manner to determine that the control activities are designed and implemented appropriately.[31] Managers should develop policies necessary to operate the process based on the objectives and related risks for the operational process. With up-to-date guidance on the CTPAT program’s methods for investigating participants, including a risk-based approach to inform decisions on which methods program personnel are to use, CBP can ensure that CTPAT personnel are consistently investigating CTPAT participants involved in security incidents. This, in turn, will enhance CBP’s ability to achieve its objective of ensuring that only program participants that meet the minimum security criteria are allowed to remain in the program.

CBP Does Not Have Clear Criteria in Its Process for Determining Enforcement Actions Against CTPAT Participants Involved in Security Incidents

As we previously described, during the post-incident analysis process, CTPAT personnel are to determine the appropriate enforcement action for CBP to take against program participants involved in security incidents. While CBP is authorized to suspend or remove a participant from the CTPAT program if the participant’s security measures and supply chain practices fail to meet program requirements, it is not legally required to do so.[32] According to our analysis of CTPAT’s available suspensions and removals data, of the 480 CTPAT participants that were involved in a security incident in fiscal years 2020 through 2024, CTPAT personnel suspended and removed a total of 166 of those participants, or 35 percent of these participants. According to CBP officials, CBP may decide to not suspend or remove CTPAT participants because, in practice, program personnel attempt to work with participants to address any security deficiencies prior to taking enforcement action. In addition, according to CBP officials, program personnel decide whether to take enforcement action against participants on a case-by-case basis and based on the totality of circumstances and available information.

We reviewed CTPAT records of personnel actions against a sample of five participants involved in security incidents and found personnel documented that they would not investigate eight security incidents but did not include any further explanation. Furthermore, program personnel did not suspend or remove those participants at the time. For example, in September 2021, an air carrier was involved in a seizure of prescription medication in the United States and the record indicates that CTPAT would not conduct an incident analysis but did not include any further explanation. Program personnel did not suspend or remove this air carrier at the time. However, that same air carrier was involved in 37 additional security incidents until CBP suspended the participant in October 2023—more than two years after the 2021 security incident. While CTPAT personnel reinstated the air carrier as a program participant in April 2024, the air carrier was involved in an additional three security incidents from the date of suspension to the date of reinstatement. After CTPAT reinstated the air carrier in April 2024, the air carrier was involved in an additional 76 security incidents through the end of fiscal year 2024, including one incident on the same day of their reinstatement. Based on our review of available data on enforcement actions, CBP did not take additional enforcement actions against this CTPAT participant during the remainder of fiscal year 2024.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks, and design appropriate types of control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks.[33] Management establishes control activities through policies and procedures to mitigate risks to achieving the entity’s objectives and address related risks. For example, as part of the risk assessment component, management identifies the risks related to the entity and its objectives, including its service organizations, the entity’s risk tolerance, and risk responses. Management designs control activities to address identified risk responses. This includes management’s requirement that all transactions and other significant events need to be clearly documented and that the documentation should be readily available for examination. Without clear, documented decision criteria that include a risk-based approach to determine appropriate enforcement action against participants involved in security incidents, CBP risks taking inconsistent actions against participants involved in security incidents, which could undermine its mission of securing the supply chain.

In addition, without documentation of its basis for taking or declining to take an enforcement action against a participant involved in a security incident, CBP cannot sufficiently oversee this process, including to determine why repeat offenders were permitted to stay in the program. As we have previously reported, the CTPAT program goes beyond trade facilitation by awarding benefits that can reduce the scrutiny given to cargo arriving in the United States.[34] Given that CTPAT participants obtain benefits that reduce the likelihood of an inspection of their cargo, having documented decision criteria for when to act against participants and when to resolve issues without a change in benefits, and requiring that those decisions be documented, could help ensure the program is addressing potential supply chain vulnerabilities.

CBP Data on Enforcement Actions Are Not Sufficiently Complete or Accurate

Our analysis shows that CBP data on CTPAT’s enforcement actions may not be sufficiently complete or accurate. Specifically, we analyzed CTPAT Portal data on enforcement actions in fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to assess the reliability and produce summary statistics, among other results. Based on our analysis, we identified four types of issues in the enforcement actions data: (1) incomplete data entries, (2) inconsistent or inaccurate data entries, (3) missing records, and (4) the potential for duplicate records.

Incomplete data entries. We reviewed 166 records of CTPAT actions to suspend and remove its participants during this timeframe and identified 99 records (approximately 60 percent) with at least one missing data entry. For example, in 59 records (approximately 36 percent), CTPAT’s data were missing information on the incident type involving these participants. In 24 of the 59 records, program officials noted that they had removed participants due to their involvement in a security incident, but there was no incident type indicated. Where CTPAT’s data did include information on the incident type, we found that most of CBP’s enforcement actions against participants involved drug smuggling. In addition, the same 59 records with missing information on the incident type did not indicate the location of the security incident. Where CTPAT’s data did include information on the location of the security incident, we found that most of CBP’s enforcement actions against participants involved incidents occurring at the southwest border.

Inconsistent or inaccurate data entries. Our analysis also shows that records in the CTPAT Portal were not always consistent or accurate. For example, of the 107 records that included information on the location of the security incident, we identified 32 records (approximately 30 percent) with inconsistent location names for where the security incident occurred. In many of these records, the location names did not include the U.S. state. In one record, the location was misspelled, which would make it difficult to capture in an analysis of locations.

Missing records. Our analysis also shows that records in the CTPAT Portal were missing. As we previously described, CTPAT personnel are to record events and investigative actions in entries in the CTPAT Portal, such as the involvement of participants in a security incident and the outcomes. We reviewed the program’s enforcement actions data and found seven instances (approximately 4 percent) where a record was missing. We showed an example of one of these instances we found to CTPAT officials, and they confirmed that the record was missing, and personnel should have entered one.

Duplicate records. Lastly, our analysis shows that in some instances, the same enforcement action against a participant appears to have been recorded more than once in the CTPAT Portal. Specifically, out of 166 records of CTPAT actions to suspend and remove participants during this time frame, we identified 30 instances (approximately 18 percent) of multiple records of suspensions with the same incident date, type, and location, among other variables. We showed an example of one of these instances to CTPAT officials, and they confirmed that these records were duplicates.

CBP officials attributed the issues in the enforcement actions data to human error because CBP’s data entry practices are manual. We found that CBP does not have sufficient internal controls, such as controls over information processing, to ensure program personnel collect complete and accurate information on program enforcement actions.

The SAFE Port Act requires CTPAT to have sufficient internal quality controls and record management to support its management systems.[35] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that entities should design their information systems and related control activities to achieve their objectives.[36] Specifically, entities should design controls into information systems to achieve validity, completeness, and accuracy of transactions and data during processing activities. This includes controls over input, processing, and outputs of data, for example. Improving the CTPAT Portal with appropriate design controls, such as edit checks of data entered, to reduce the possibility for user errors would help the program ensure that it has complete and accurate data on the outcomes of participant involvement in security incidents. This information system is critical for CBP to conduct the basic functions of program management such as applying benefits to and removing benefits from program participants. Without complete and accurate data, CBP cannot ensure that it appropriately reviews participants who fail to meet minimum security criteria for continued participation and benefits from the program.

CBP Has Not Met Some Statutory Requirements in the SAFE Port Act in Its Management of the CTPAT Program

The SAFE Port Act establishes requirements for CBP to manage the CTPAT program. These requirements include (1) annual reviews of the minimum security requirements and updating them as necessary, (2) developing annual workload projections taking available resources into consideration, and (3) developing a 5-year strategic plan to identify outcome-based goals and performance measures.

Annual reviews of the minimum security requirements. The SAFE Port Act requires CBP to review the CTPAT program’s minimum security requirements at least once every year and update such requirements as necessary.[37] As we previously described, CTPAT participants are to meet the minimum security requirements specific to each industry type in the cargo supply chain.

In 2020, the CTPAT program updated minimum security requirements for all entities that participate in the program. According to CBP officials, the program’s 2020 update to the minimum security requirements was the first since the program established the original requirements in 2001, when the CTPAT program was first stood up. Since the last update to the minimum security requirements in 2020, CBP officials stated that program personnel have worked with rail carriers to address certain security risks in that supply chain environment. However, as of June 2025, the program has not updated this specific industry type’s minimum security requirements. While CBP officials told us that program personnel have reviewed the minimum security requirements of other specific industry types since 2020, they could not provide any documentation of such reviews having been conducted or any updates to the minimum security requirements for these industry types.

CBP officials stated that the program has not reviewed and updated the program’s minimum security requirements for industries annually because the CTPAT program does not have a formal mechanism in place to conduct this work. Without annually reviewing and updating as necessary the CTPAT program’s minimum security requirements, as required by law, CBP leaves the supply chain vulnerable to emerging risks not captured by the program’s 2020 standards. Developing a formal mechanism to perform this work would help CBP ensure minimum security requirements reflect the changing environment of and associated risks to the global supply chain.

In addition, leveraging CTPAT data on security incidents and outcomes could help CBP ensure any changes to these program requirements are informed by quality information. For example, such a mechanism could include regular, systematic analysis of all security incidents involving program participants, including those reported by field offices or self-reported by participants, to better and more accurately monitor information and trends on security incidents involving CTPAT participants nationwide on key facets such as incident types, locations, and business types. Using quality information and data analytics to support the required annual review of the CTPAT program’s minimum security requirements would position CBP to make better informed decisions in its management of the program and help ensure updates are made to the minimum security requirements as necessary to address identified risks.

Annual workload projections. The SAFE Port Act requires CBP to ensure that CTPAT has an annual plan for each fiscal year designed to match the program’s available resources to the projected workload.[38] However, the CTPAT program does not have an annual plan to meet this requirement.

According to CBP officials, the agency was not aware of the SAFE Port Act requirement that CBP develop an annual plan for each fiscal year designed to match the program’s available resources to the projected workload. Officials noted that they have plans for mission critical validation and revalidation work, in response to a separate provision of the SAFE Port Act, but do not have plans that reflect the full workload of the CTPAT program.[39] For example, such a plan should include the projected workload and resources associated with addressing security incidents involving CTPAT participants. As we previously described, these incidents require CTPAT personnel to investigate the facts and circumstances, determine culpability, and take appropriate enforcement actions such as a suspension from the program, according to CBP’s guidance for conducting a post-incident analysis.

Officials also stated that the agency has not projected the workload needed to respond to security incidents involving CTPAT participants, in part because they do not expect program participants to be involved in such incidents. Officials also told us that program personnel currently manage these cases as they arise and follow the standard operating procedures for this work.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should establish control activities by documenting in policies what is expected and in procedures specified actions that implement policies to mitigate risks to achieving the entity’s objectives to acceptable levels.[40] In CBP’s case, such control activities could include policies and procedures for developing an annual plan for each fiscal year to match resources to the projected workload of the CTPAT program, a requirement of the SAFE Port Act.

Establishing control activities to ensure CBP develops an annual plan for each fiscal year to match available resources to the projected workload of the CTPAT program would allow CBP to have a full understanding of the CTPAT program’s workload. Further, developing this annual plan for each fiscal year—a requirement in the SAFE Port Act—to include, for example, projecting CTPAT’s workload for addressing program participant involvement in security incidents, would better ensure that the CTPAT program effectively allocates its available resources across its offices to address all security incidents in a timely and thorough manner. Establishing such control activities and developing an annual plan could help CBP ensure that the CTPAT program is in compliance with the SAFE Port Act and has the capacity to meet both current and future mission requirements to address these security incidents. In addition, leveraging CTPAT data on security incidents and outcomes could help CBP project this workload for future fiscal year plans.

Strategic plan. The SAFE Port Act requires CBP to ensure that the CTPAT program includes a 5-year plan to identify outcome-based goals and performance measures of the program.[41] However, CBP has not published a strategic plan for the CTPAT program since November 2004.[42] In May 2025, CTPAT officials told us that senior CBP officials informed CTPAT personnel that they are not to produce such a plan because the program’s 5-year strategic plan would be integrated into CBP’s Office of Field Operations’ 5-year strategic plan.[43]

|

Definitions of Strategic Goals, Performance Goals, and Performance Measures In prior work, GAO has identified key practices that help agencies achieve results and improve performance, including: · Strategic goals: outcome-oriented statements of aim or purpose. They articulate what the organization wants to achieve in the long-term to advance its mission and address relevant problems, needs, challenges, and opportunities. · Performance goals: specific results an agency expects the program to achieve in the near term. Our prior work indicates that it can be beneficial for performance goals to have specific targets and time frames that reflect strategic goals. · Performance measures: concrete, objective, observable conditions that permit the assessment of progress made towards the agency’s goals. Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑107893 |