ILLICIT SYNTHETIC DRUGS

Trafficking Methods, Money Laundering Practices, and Coordination Efforts

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Michael E. Clements clementsm@gao.gov or Triana McNeil mcneilt@gao.gov

What GAO Found

Mexican transnational criminal organizations are a major supplier of the top two illicit synthetic drugs involved in overdose deaths in the U.S.—fentanyl and methamphetamine. To supply these drugs to U.S. users, these organizations

· source and purchase precursor chemicals primarily from China, using payment methods such as electronic funds transfers and virtual currency;

· produce or oversee the production of fentanyl and methamphetamine in clandestine labs in Mexico; and

· smuggle the drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border and supply them to U.S.-based drug trafficking groups.

Local drug trafficking groups sell these drugs to users through e‑commerce platforms, online marketplaces, mobile applications, and social media using payment methods such as cash, peer-to-peer payment applications, and virtual currency, according to Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reports.

Transnational criminal organizations launder the illicit proceeds from synthetic drug sales using methods such as

· bulk cash smuggling (moving physical currency across international borders),

· funnel accounts (bank accounts that collect deposits from members of the criminal network in multiple locations),

· trade-based money laundering (using goods in trade transactions to disguise the movement of illicit funds),

· virtual currency (exchanging bulk cash for virtual currency), and

· Chinese money laundering networks.

Chinese money laundering networks are largely decentralized and use both underground-banking mechanisms (which bypass formal banking channels) and other laundering methods within banking systems to convert, move, and obscure illicit proceeds for a fee. Mexican transnational criminal organizations are increasingly using these networks in part because their laundering schemes have lower costs than other organizations, according to law enforcement officials.

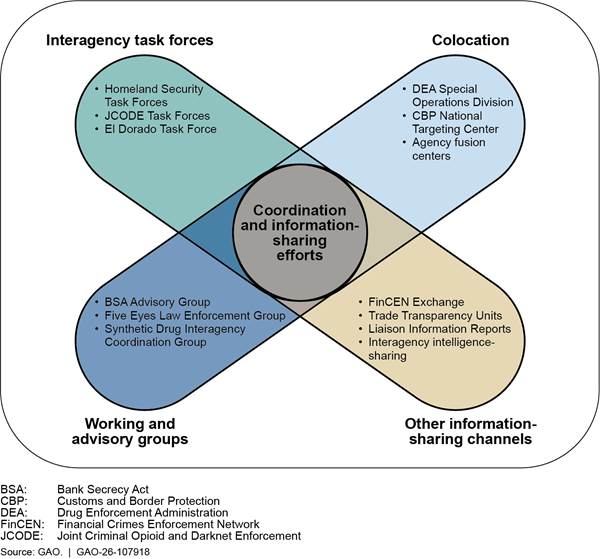

To combat drug trafficking and related money laundering, federal agencies coordinate and share information with each other and with state, local, and international partners through task forces, working and advisory groups, colocation, and other information-sharing channels. These mechanisms help agencies share resources and expertise, prevent overlapping investigations, and combine unique authorities. In addition, starting on January 20, 2025, the administration began instituting a variety of new policies, including some aimed at combating the flow of synthetic drugs into the U.S. For example, Executive Order 14159 requires the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security to jointly establish Homeland Security Task Forces in all 50 states to end the presence of cartels and transnational criminal organizations in the U.S. Agencies reported that it is too early to assess the full impact of these policies.

Why GAO Did This Study

Mexican transnational criminal organizations have fueled the U.S. synthetic drug crisis, contributing to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths over the last 5 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These organizations dictate the flow of nearly all illicit drugs into the U.S. They generate billions of dollars in profits from the sale of synthetic drugs and must launder those profits, often with the help of professional criminal money launders.

Since 2019, FinCEN and other federal agencies have intensified efforts to combat illicit finance related to synthetic drug trafficking. Additionally, within the Department of Justice, the DEA, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and United States Attorneys’ Offices have investigated and prosecuted cases related to these activities. GAO added drug misuse to its High-Risk List in 2021; the list highlights vulnerable areas across the federal government.

The Preventing the Financing of Illegal Synthetic Drugs Act contains a provision for GAO to study the trafficking of synthetic drugs into the U.S. and related illicit financing activity. This report describes (1) how Mexican transnational criminal organizations source, produce, and distribute synthetic drugs; (2) how these organizations launder their proceeds; and (3) information-sharing and coordination efforts by federal agencies to combat synthetic drug trafficking and related money laundering.

GAO reviewed federal agency documents and reports, recent executive orders, and recent court cases involving synthetic drug trafficking. GAO also interviewed federal agency officials, industry representatives, and other stakeholders with relevant expertise.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CBP |

Customs and Border Protection |

|

CDC |

Center for Disease Control and Presentation |

|

CMLN |

Chinese money laundering networks |

|

DEA |

Drug Enforcement Administration |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

FinCEN |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network |

|

ICE-HSI |

Immigration and Customs Enforcement-Homeland Security Investigations |

|

IRS-CI |

Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation |

|

TCO |

Transnational criminal organizations |

|

USPS |

United States Postal Service |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 18, 2025

The Honorable Tim Scott

Chairman

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Transnational criminal organizations (TCO) have played a central role in fueling the U.S.’s ongoing synthetic drug crisis.[1] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), this crisis has contributed to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths over the last 5 years. Provisional data show more than 42,200 overdose deaths from illicit synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl[2]—lab-manufactured substances often far more potent than natural opioids—during the 12-month period ending in April 2025.[3] We added drug misuse to our High-Risk List in 2021. The list highlights areas across the federal government that are seriously vulnerable to mismanagement or that need transformation. Drug misuse remains on the High-Risk List as of February 2025.[4]

TCOs generate billions of dollars in profits from the sale of illicit synthetic drugs. To conceal the origin of these funds and integrate them into the legitimate economy, TCOs often rely on professional money launderers and employ a range of tactics, according to federal law enforcement. These tactics include underground banking systems, trade-based money laundering schemes, and use of virtual currencies, among other methods.[5]

Since 2019, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and other federal agencies have intensified efforts to combat illicit finance related to synthetic drug trafficking. The Department of the Treasury launched the Counter-Fentanyl Strike Force in 2023, and FinCEN has issued multiple advisories, including one in June 2024, to help financial institutions identify suspicious activity linked to the manufacturing of illicit fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.[6] Additionally, the Department of Justice (DOJ), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and United States Attorneys’ Offices, have investigated and prosecuted TCOs involved in synthetic drug trafficking and laundering of the proceeds.

The Preventing the Financing of Illegal Synthetic Drugs Act includes a provision for us to study the trafficking of synthetic drugs into the U.S. and related illicit financing activity.[7] This report describes (1) how TCOs source, manufacture, and distribute synthetic drugs; (2) how these organizations launder their proceeds; and (3) coordination and information-sharing efforts by federal agencies, and recent policy changes. This report primarily focuses on Mexican TCOs, as they dictate the flow of nearly all illicit drugs, including synthetic drugs, into the U.S., according to DEA.[8]

For all objectives, we reviewed federal agency reports and guidance, executive orders, prior GAO reports, and think tank publications. We also reviewed indictments and adjudicated cases identified on the DOJ website for press releases, issued between January 1, 2023, and June 1, 2025, related to synthetic drugs, precursor chemicals, human smuggling, and money laundering.[9]

Additionally, we interviewed officials from federal agencies and offices responsible for identifying, investigating, and prosecuting synthetic drug trafficking and illicit finance, specifically: (1) components within DOJ, including the Criminal Division, FBI, DEA, Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys, and the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces; (2) components within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), including Immigration and Customs Enforcement-Homeland Security Investigations (ICE-HSI) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP); (3) Department of State; (4) components within Treasury, including FinCEN and the Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI); and (5) the U.S. Postal Inspection Service within the U.S. Postal Service (USPS).[10] We also interviewed stakeholders from three nonprofit policy entities: the RAND Corporation, the Brookings Institute, and InSight Crime.[11]

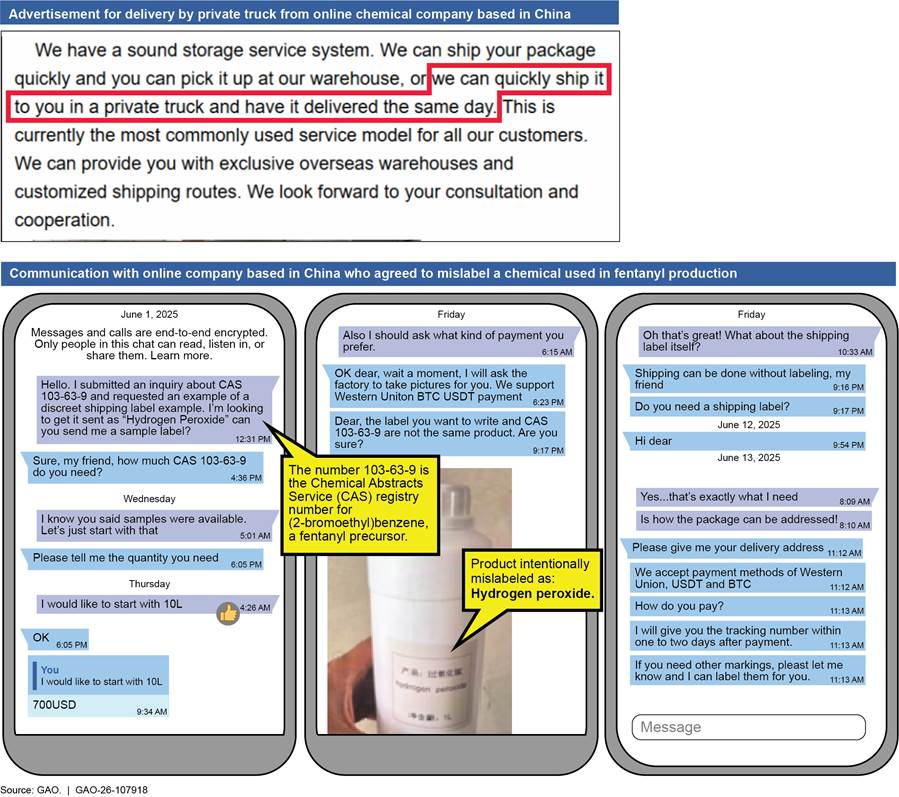

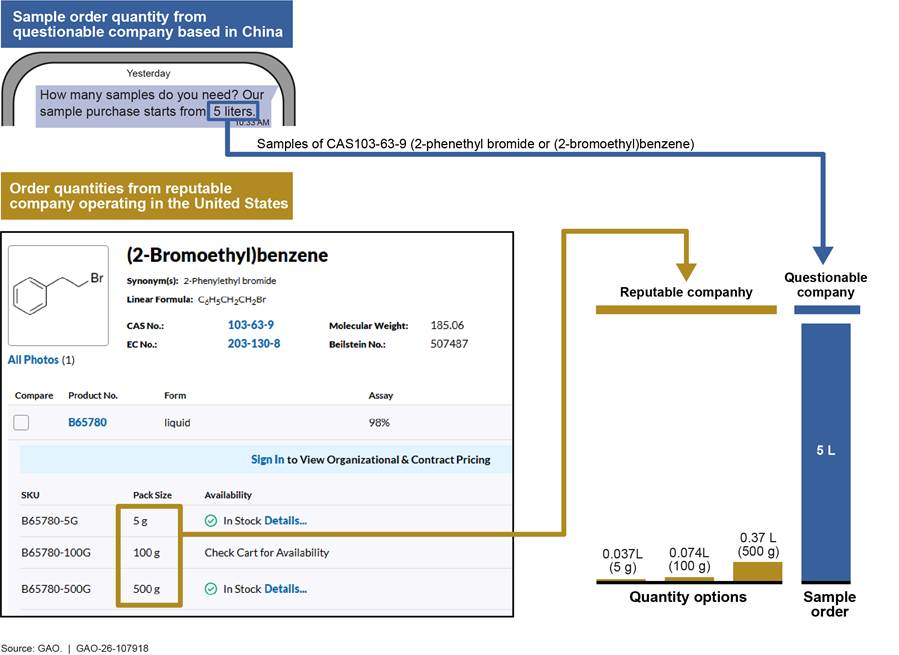

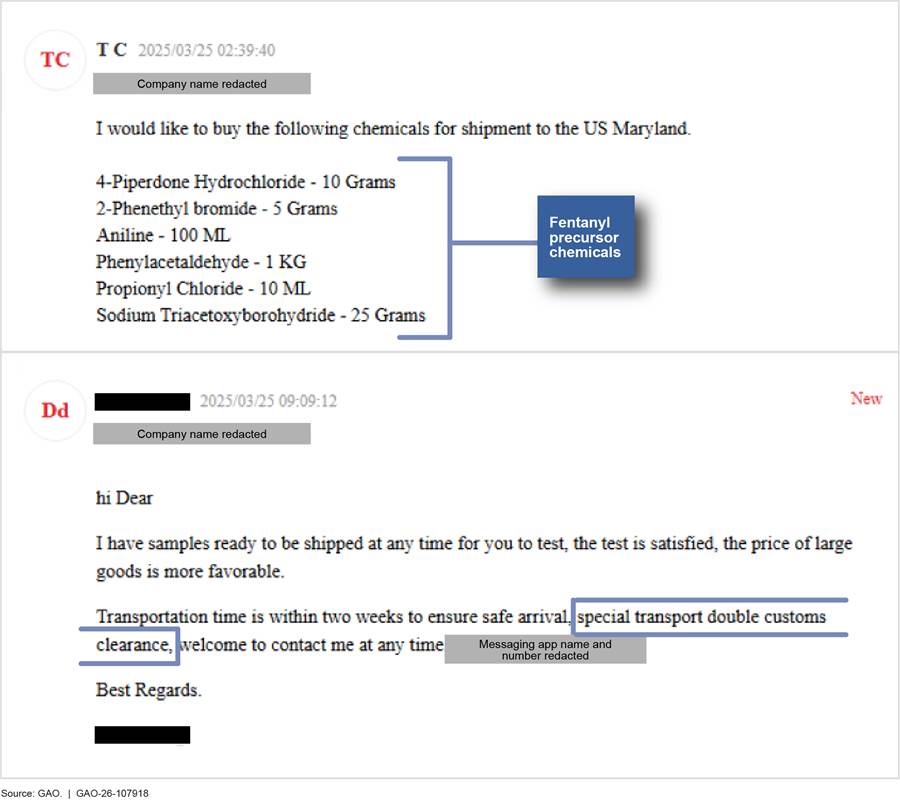

To address our first objective, we focused our work on fentanyl and methamphetamine as they were the top two synthetic drugs involved in overdose deaths,[12] according to CDC’s 2023 data.[13] We reviewed reports from federal agencies and other sources such as the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. In addition, we reviewed online listings for illicit drug manufacturing supplies and finished drugs. We used undercover identities to communicate with questionable China-based chemical companies and purported drug dealers.[14] Our investigative work did not confirm that the chemical companies in fact sold the listed chemicals or that the purported drug dealers in fact sold the listed drugs.

To address our second objective, we reviewed government reports, industry articles, research institute publications, and legislative materials published in the past five years on the use of payment methods and money laundering typologies associated with synthetic drug trafficking.[15]

We also requested and analyzed FinCEN data from August 2019 through March 2025 on suspicious activity reports that referenced a 2019 or 2024 FinCEN advisory related to synthetic drug trafficking. In addition, we analyzed suspicious activity reports that referenced certain activities, such as funnel accounts and electronic funds transfers.[16]

To address our third objective, we interviewed or received written responses from the agencies identified above on agency coordination and information-sharing efforts related to these issues.[17] We also reviewed agency memos, press releases, and websites that described coordination and information sharing among federal, state, local, international partners, and private sector partners.

We also reviewed recent policy changes implemented between January 20, 2025, and July 31, 2025, including presidential proclamations and executive orders and related amendments. We interviewed or received written responses from agencies about the policies. See appendix I for a complete description of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

We conducted our related investigative work in accordance with investigation standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

TCOs engage in a wide range of criminal activities that threaten U.S. public safety and national security, including the trafficking of humans, firearms, wildlife, and drugs. TCOs from Mexico are a major manufacturer of illicit synthetic drugs entering the U.S.

Illicit fentanyl and methamphetamine are the top two causes of drug- related deaths in the U.S. according to CDC’s 2023 data. According to DEA, fentanyl is a synthetic opioid typically used to treat patients with chronic severe pain. It is a controlled substance that is about 100 times more potent than morphine. Methamphetamine is also a highly addictive synthetic drug, though it has more limited legitimate uses. According to the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats, these drugs are often more lethal than plant-based drugs like cocaine and heroin.[18] Further, they can be made anywhere with widely available chemicals and equipment and can be shipped in small quantities.

Synthetic drugs are made by combining chemicals known as precursor chemicals.[19] While some of these precursor chemicals are regulated, others of them are unregulated and have safe and legitimate purposes, such as producing cosmetics, perfumes, and cleaning agents.[20]

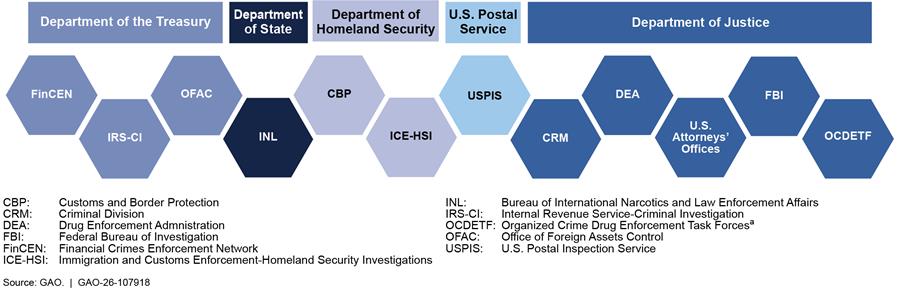

Multiple federal law enforcement and financial agencies are involved in efforts to combat synthetic drug trafficking and related money laundering (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Key Federal Agencies Involved in Combating Synthetic Drug Trafficking and Related Illicit Finance

Note: This list is not exhaustive, and tile placement does not indicate agency role or relationships.

aAccording to the Department of Justice, as of September 30, 2025, OCDETF has been shut down and its functions have been transferred to the new Homeland Security Task Forces described later in this report.

One way the federal government combats the illicit flow of money is through the Bank Secrecy Act. The act requires covered financial institutions (e.g., banks, broker-dealers, and money services businesses) to among other things, maintain detailed records and file suspicious activity reports and other records.[21] FinCEN enforces the Bank Secrecy Act and other requirements related to anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism. The information financial institutions report through suspicious activity reports and other records can help law enforcement identify and investigate potential money laundering and other illicit activity connected to synthetic drug trafficking.[22]

Federal agencies also partner with state and local agencies, as well as coordinate with international counterparts, to combat synthetic drug trafficking and related financial crimes. For example, DOJ has broad authority to investigate crime and prosecute offenders and conducts much of its work in offices located throughout the U.S. and overseas. Similarly, DHS works to secure and protect air, land, and water borders across the country and internationally. Through partnerships with other countries and international law enforcement, DHS works to identify and stop criminals and illegal activity, such as drug smuggling, prior to reaching the U.S. For example, DOJ has broad authority to investigate crime and prosecute offenders and conducts much of its work in offices located throughout the U.S. and overseas. Similarly, DHS works to secure and protect air, land, and water borders across the country and internationally.

Sourcing, Manufacturing, and Distribution of Synthetic Drugs

How do Mexican TCOs source precursor chemicals?

Mexican TCOs use diverse business strategies to directly or indirectly source fentanyl and methamphetamine precursor chemicals, primarily from China-based chemical companies.[23] According to DEA’s 2024 drug threat assessment and a nonprofit entity report, TCOs may obtain precursor chemicals through several channels: (1) directly from suppliers in China; (2) through intermediaries in the U.S., such as reshipping companies or complicit companies or individuals; and (3) via brokers who work independently of any TCO.[24] The nonprofit entity report also indicates that large TCOs rely on intermediaries who operate front companies to gather the chemicals in bulk in Mexico before selling them to criminal groups. According to Treasury officials, both China-based suppliers and TCOs use networks of front and shell companies in the sale and purchase of precursor chemicals.

FinCEN reported that Mexican TCOs began sourcing fentanyl precursor chemicals from China in 2019 after China placed controls on all fentanyl-related substances.[25] According to Department of State officials, the controls applied to the manufacture and export of these substances. Before 2019, Mexican TCOs sourced finished fentanyl from China, according to the reports. Mexican TCOs have sourced methamphetamine precursor chemicals from China and India since at least 2009, according to reports from DOJ and the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.[26]

Online Marketplaces

Chemical suppliers in China use e-commerce platforms and internet advertising to reach their customers, which may include those who purchase and supply the precursor chemicals to Mexican TCOs. DOJ has noted that many China-based suppliers openly advertise precursor chemicals on the internet. FinCEN likewise reported that these companies use darknet marketplaces, e-commerce and other public platforms, such as social media platforms, to market chemicals used to manufacture illicit fentanyl.[27] According to a private sector report, these platforms are used only to advertise the products, and buyers must contact the supplier directly to make purchases.[28] Consistent with this, the China-based chemical companies we identified in our web searches did not have an option for direct online purchases, but instead provided only options to contact the company.

DEA and others have reported that Chinese chemical suppliers use certain keywords and phrases to signal their willingness to supply the chemicals for illicit purposes.[29] These include offering discreet delivery options and guaranteeing customs clearance. Our web searches and undercover communication with China-based chemical companies identified examples of such listings, which are included in appendix II.

In its 2025 National Drug Threat Assessment,[30] DEA reported that some China-based chemical suppliers may be growing wary of supplying precursors controlled by China to their international customers, demonstrating an increasing awareness of the government of China’s efforts to comply with recent updates to the United Nations counternarcotics treaty.[31] To mitigate risks associated with controlled precursors, China-based chemical supply companies advertise and ship an ever-diversifying array of alternative precursor chemicals for fentanyl manufacturing, according to DEA. Later in this report, we discuss how Mexican TCOs have adapted to chemical restrictions by producing fentanyl and methamphetamine using less restricted chemicals.

Payment Methods

TCOs use various payment methods to purchase precursor chemicals, including electronic funds transfers and virtual currency, according to FinCEN. Payments can be structured as multiple low-value transactions from different senders to evade Bank Secrecy Act reporting and recordkeeping requirements and disguise links to drug trafficking.[32] Transfers may route through U.S. correspondent banks or the agents of money services businesses.[33] In its review of 2024 fentanyl-related Bank Secrecy Act filings, FinCEN found that 57 percent were filed by depository institutions and 32 percent by money services businesses.[34] FinCEN also found that electronic funds transfers, referenced in 80 percent of reports, were the most common payment method in fentanyl-related Bank Secrecy Act filings. According to FinCEN’s 2024 advisory, illicit actors often route payments through shell and front companies to disguise shipments and counterparties.

TCOs use virtual currency to purchase precursor chemicals, according to DEA and Treasury. Illicit actors use virtual currencies because they are somewhat anonymous, making detection by law enforcement more difficult. In a study of Chinese precursor manufacturers, a blockchain analytics firm reported that the amount of virtual currency deposited into wallets linked to these manufacturers increased by more than 600 percent from 2022 to 2023, and more than doubled in the first four months of 2024.[35] FinCEN’s review of 2024 Bank Secrecy Act filings for suspected fentanyl-related activity found that nearly 10 percent of reports had a potential nexus to virtual currency. Of those, 86 percent referenced Bitcoin.

A knowledgeable stakeholder in international crime told us that Mexican TCOs increasingly transmit funds directly to wallets controlled by sellers who accept virtual currency. For example, in April 2023, Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned two entities in China and five individuals based in China and Guatemala for supplying precursor chemicals to drug cartels in Mexico, which paid using a virtual currency wallet. In October 2023, DOJ announced indictments charging China-based chemical companies and Chinese nationals with trafficking fentanyl precursors and laundering drug proceeds using virtual currency (see text box).

|

Federal Court Case: Combating the Sale and Transit of Chemicals for Illicit Drug Manufacturing In October 2023, the Department of Justice announced the unsealing of eight indictments involving Hanhong Medicine Technology (HUBEI) Co., Ltd., a pharmaceutical company located in Wuhan, China, for the alleged sale of fentanyl precursor chemicals, xylazine, and other drugs to customers in the U.S. and Mexico. The indictment also lists two coconspirators: an alleged drug trafficker affiliated with a Mexican transnational criminal organization and an alleged drug trafficker in Pennsylvania. One of the indictments charges that HUBEI openly advertised online and sold an array of chemicals, including fentanyl precursors, methamphetamine precursors, nitazenes, and xylazine, using its website, storefront websites, and social media platforms to target customers in the U.S. and Mexico. HUBEI allegedly sold and shipped fentanyl precursors and xylazine from China to a fentanyl manufacturer in Mexico and a known drug trafficker based in Pennsylvania. The company is also charged with shipping more than 43 kilograms of fentanyl precursor chemicals to undercover federal agents in South Florida. According to the indictment, this amount is enough to manufacture approximately 15.2 million fentanyl-laced pills containing a 5-milligram dose of fentanyl each. The indictment charges that the sale was negotiated via an instant messaging application and that representatives of HUBEI operated a cryptocurrency wallet to accept payments. The defendants were indicted and charged with Conspiracy to Manufacture and Distribute Fentanyl (21 U.S.C. § 846), Manufacture and Distribution of a Fentanyl Precursor with Intent to Unlawfully Import into the U.S. (21 U.S.C. § 959(a)), and Conspiracy to Commit Money Laundering (18 U.S.C. § 1956(h)). The defendants were transferred to Fugitive Status on October 31, 2023, and the case remains on hold, as of December 1, 2025. The charges described above are not exhaustive and do not represent a comprehensive overview of the case. We highlighted aspects of the indictments that are most relevant to our work. Charges in an indictment are merely allegations. All defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law. For more information on this case, see U.S. v. Hanhong Medicine Technology (HUBEI) Co. Ltd., et al., (23-CR-20394), U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida. |

Source: GAO presentation of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑26‑107918

Shipping and Smuggling Methods

According to DEA’s 2024 drug threat assessment report, Mexican TCOs use seaports in Mexico as the main entry points for large quantities of methamphetamine and fentanyl precursor chemicals.[36] Further, some large TCOs exert control over multiple Mexican seaports, which they may charge other drug traffickers to use. While seaports are key to getting industrial-scale shipments from China to Mexico, most fentanyl precursors arrive via air cargo or through postal facilities, according to DEA.

Mexican TCOs and their chemical suppliers in China rely on evasive and diverse shipping methods to avoid detection by law enforcement or international chemical regulators, according to DEA and others.[37] These methods include

· exploiting de minimis shipments,[38]

· comingling precursors with larger shipments of other legitimate goods,

· mislabeling containers as pet food or household goods,

· using front companies to appear legitimate, and

· shipping through neighboring countries, such as routing them from China to the U.S. before crossing the border to Mexico.[39]

Mexican TCOs may also obtain the chemicals by diverting or stealing from company production lines, such as by siphoning chemicals from imports, according to DEA reports.[40]

How do Mexican TCOs manufacture fentanyl and methamphetamines?

Mexican TCOs manufacture or oversee the manufacture of fentanyl and methamphetamine using agile methods to respond to market and regulatory changes. According to DEA and nongovernment reports, these drugs are manufactured in crude, clandestine labs in Mexico, ranging from large open-air labs in rural areas to small labs in urban apartments.[41] Many of these labs do not require sophisticated chemistry equipment or elaborate operations to manufacture the drugs.

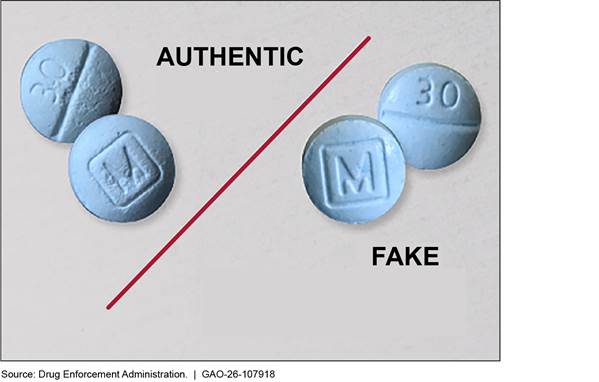

Mexican TCOs manufacture fentanyl and methamphetamine in several forms to appeal to various markets and drug users, including those who misuse prescription drugs, according to DEA.[42] These TCOs are also increasingly producing counterfeit prescription pills laced with fentanyl or methamphetamine (see fig. 2). Users may be unaware these pills contain fentanyl or methamphetamine, creating the risk of overdose or other harm.

Figure 2: Comparison of Authentic Prescription Pills and Fake Prescription Pills Laced with Illicit Fentanyl

Note: Authentic prescription oxycodone contains an imprint of “M30” to indicate that it contains 30 milligrams of oxycodone hydrochloride.

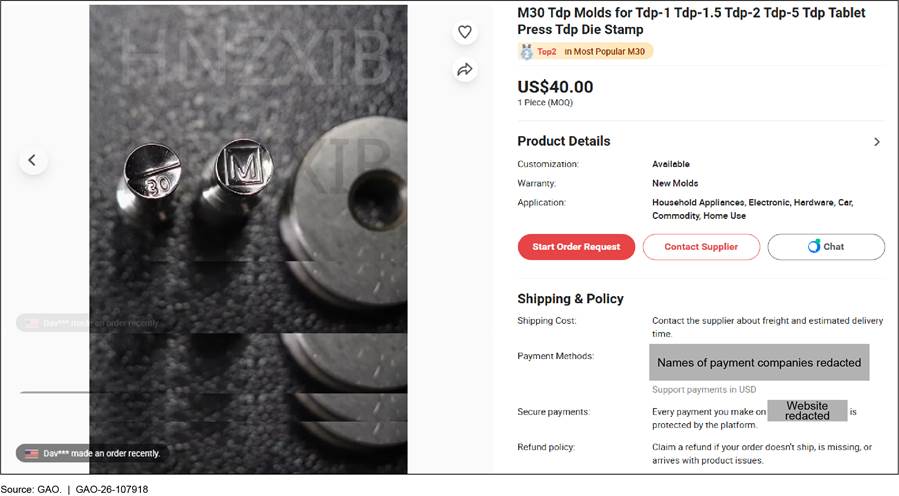

TCOs manufacture counterfeit prescription pills using pill press machines and die molds that replicate trademarked markings. These tools are advertised and sold online, primarily by companies based in China, according to DEA and FinCEN reports.[43] During our investigative work, we found a die mold for producing counterfeit oxycodone “M30” pills listed for sale online from a China-based company (see fig. 3).[44]

Note: Authentic prescription oxycodone contains an imprint of “M30” to indicate that it contains 30 milligrams of oxycodone hydrochloride. Counterfeit drugs often contain these markers, so they appear authentic.

TCOs have recently shifted away from manufacturing methods that rely on heavily restricted precursors in favor of less restricted, easier-to-obtain chemicals, according to DEA. DEA’s 2025 National Drug Threat Assessment indicates that this shift led to a decline in the purity of fentanyl beginning in 2024.[45] However, the assessment notes that lower purity does not make street-level fentanyl less dangerous because U.S.-based traffickers often adulterate it with other drugs, such as xylazine (a veterinary sedative), which can complicate the reversal of overdoses.

How do Mexican TCOs smuggle and distribute fentanyl and methamphetamine into the U.S.?

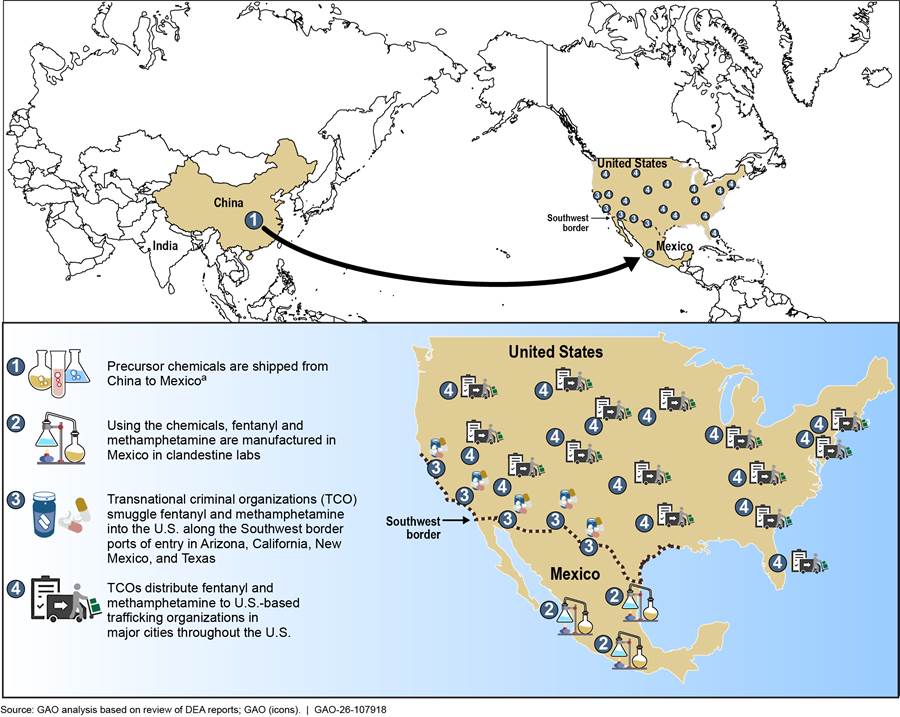

Mexican TCOs use their influence over Mexican transportation routes and maintain U.S. distribution networks to smuggle and distribute fentanyl and methamphetamine in the U.S., according to DEA’s 2024 and 2025 drug threat assessments (see fig. 4 for methods used).[46] TCOs move these drugs through Mexico and across the southwest U.S. border using tractor trailers, human mules, couriers, privately-owned vehicles, among other methods. Some traffickers pay other criminal organizations to access ports of entry, tunnels, or other smuggling routes.

Figure 4: How Mexican TCOs Generally Source Precursor Chemicals and Distribute Fentanyl and Methamphetamine into the U.S.

Note: This figure focuses on trafficking from Mexico as Mexican transnational criminal organizations are the largest supplier of illicit synthetic drugs to the U.S.

aPrecursor chemicals from China may also be shipped through neighboring countries, such as routing them from China to the U.S. before crossing the border to Mexico. While China is the primary source country for precursor chemicals, India is a secondary source country, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s National Drug Threat Assessment 2024.

Mexican TCO drug trafficking activities are linked to human trafficking, human smuggling, and firearms trafficking. According to DEA, TCOs may use trafficked women and children to smuggle drugs across the U.S. border.[47] In addition, people seeking to be smuggled may pay their fees by transporting drugs into or within the U.S., according to DOJ officials we interviewed. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported that firearms trafficking and drug trafficking benefit from the other’s established routes.[48] According to ICE, TCOs use illegally trafficked firearms to protect drug smuggling operations and secure smuggling routes. See text box below for a case involving TCO-linked defendants accused of drug distribution and human smuggling.

|

Federal Court Case: Combating Drug Trafficking, Human Smuggling, and Other Crimes In November 2023, a federal grand jury in Tucson, Arizona, returned an indictment against alleged members of Malas Manas, a transnational criminal organization operating in Mexico with the permission of the Sinaloa cartel, according to a DOJ press release. The indictment alleges that the defendants participated in a polycriminal network operating in the U.S. and Mexico that involved drug trafficking, human smuggling, and laundering the proceeds of the criminal activities. Between 2019 and 2023, the defendants allegedly distributed fentanyl, methamphetamine, and other illicit drugs in Arizona and elsewhere in the U.S. Additionally, they allegedly smuggled individuals unlawfully present in the U.S. from the U.S.-Mexico border region into Arizona. The indictment charges that the defendants used a social media platform to communicate with potential customers and to discuss smuggling fees and foot guide commissions. Payments were allegedly made by family members in the U.S. via bulk cash or wire transfer, and the money was allegedly moved subsequently to Mexico either in person or through financial institutions in Mexico. The defendants were indicted on November 29, 2023, and charged with various criminal violations, including Aiding and Abetting Distribution of Marijuana, Methamphetamine, Fentanyl, and Cocaine (21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1), 2), Conspiracy to Transport Aliens (8 U.S.C. § 1324), and Conspiracy to Launder Monetary Instruments (18 U.S.C. § 1956(h)). The accused leader of the human smuggling operation, Jorge Damian Roman-Figueroa, was arrested by Mexican law enforcement in October 2021, prosecuted, and sentenced to 8 years in prison, where he allegedly continues to direct his organization’s operations. As of December 1, 2025, the case remains open. The charges described above are not exhaustive and do not represent a comprehensive overview of the case. We highlighted aspects of the indictments that are most relevant to our work. Statements in an indictment are merely allegations. All defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law. For more information on this case, see U.S. v. Roman-Figueroa et al. (4:23-cr-01975), U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona. |

Source: GAO presentation of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑26‑107918

Most fentanyl and methamphetamine trafficking into the U.S. occurs through official ports of entry along the southwest border, according to DEA.[49] More than 90 percent of interdicted fentanyl is stopped at these locations, where TCOs primarily use vehicles driven by U.S. citizens to smuggle the drugs, according to DHS.[50] TCOs also smuggle some drug shipments between official ports of entry to evade detection, according to DOJ officials we interviewed. For example, TCOs have used river crossings located in the California desert to smuggle fentanyl and methamphetamine into the U.S.

DEA reports indicate that Mexican TCOs are generally not directly involved in local sale and distribution.[51] Rather, they leverage relationships with U.S.-based trafficking organizations who supply the drugs to local independent drug trafficking groups and gangs. The TCOs maintain large distribution hubs across the U.S. to supply fentanyl and methamphetamine to regional cartel-affiliated traffickers in key cities such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, Houston, Chicago, Atlanta, and Miami.

How do local drug traffickers distribute and sell fentanyl and methamphetamine?

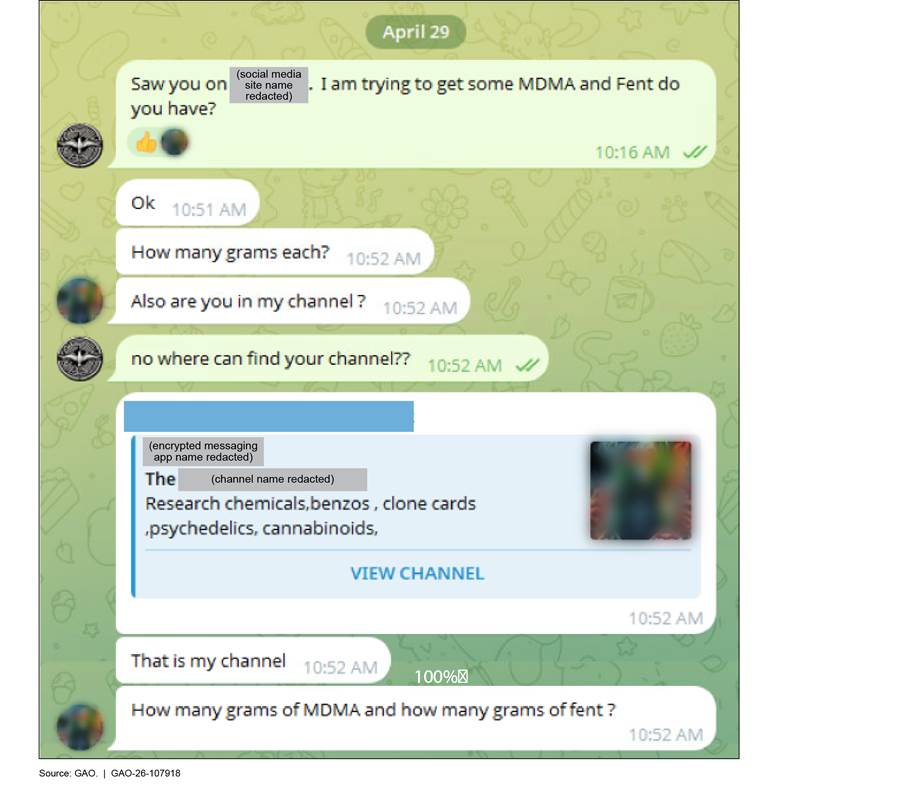

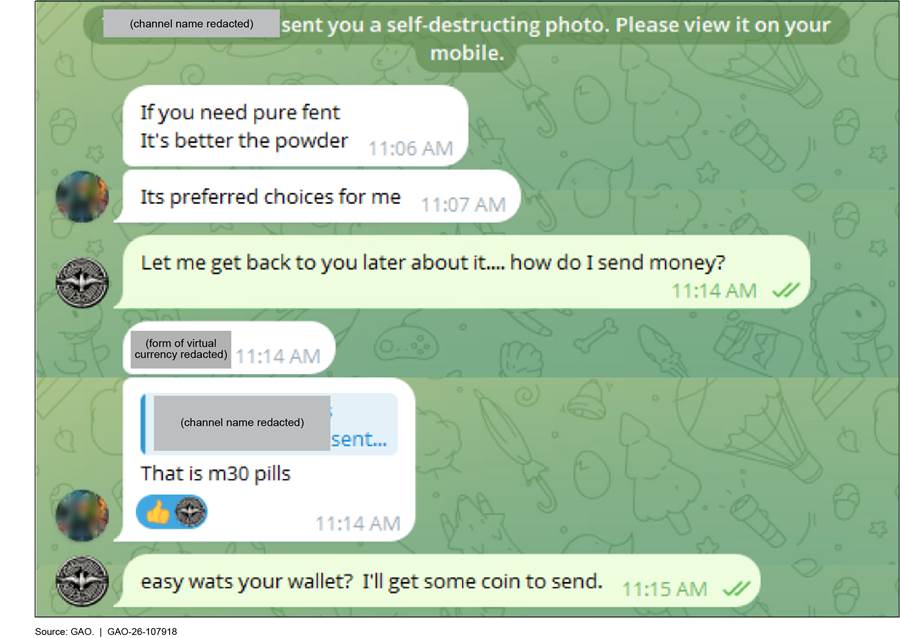

According to DEA, drug traffickers in the U.S. often use online platforms to advertise, communicate, and sell fentanyl and methamphetamine, among other drugs.[52] These platforms include social media sites and applications and encrypted messaging applications.[53] For example, in our undercover work we communicated with a purported drug trafficker we found through a social media site, who then directed us to a channel on an encrypted messaging app (see fig. 5). We plan to refer this instance of potential drug trafficking to DEA for follow-up as appropriate.

Figure 5: GAO Undercover Communication with Purported Drug Trafficker Who Uses a Social Media Site and Encrypted Messaging Application

Drug traffickers in the U.S. may adulterate Mexican TCO-supplied fentanyl and methamphetamine with other drugs before selling them to the local market, according to DEA.[54] U.S.-based drug traffickers may do this to increase profits by reducing the amount of costly drugs in a mixture or to cater to user preferences, such as a prolonged high. Fentanyl adulterants include xylazine, nitazenes (synthetic opioids that can match or surpass the potency of fentanyl), and medetomidine (a veterinary sedative 200–300 times more potent than xylazine).[55] U.S. traffickers can obtain these adulterant drugs directly from China, according to DEA.[56] In its 2025 National Drug Threat Assessment, DEA reported that its forensic analysis found that of the 5,058 polydrug (multiple-drug) samples, 75 percent had fentanyl or a fentanyl-related substance as the primary drug in 2024.[57]

Local drug trafficking groups in the U.S. use a variety of payment methods to facilitate the sale of synthetic drugs, which may occur both online (through marketplaces, e-commerce platforms, mobile applications, and social media platforms) and in person, according to FinCEN and DEA reports.[58] These reports noted that to complete sales, traffickers rely on cash, peer-to-peer payment applications, and increasingly, virtual currency.

While cash remains the primary method for street-level sales, DEA has reported a rise in the use of virtual currencies and peer-to-peer payment methods to conduct synthetic drug transactions and to obscure the origin of illicit funds. In one case, a dark web vendor pleaded guilty in 2024 to selling controlled substances, including fentanyl, and accepting virtual currency as payment (see text box). The drug trafficking organization laundered proceeds into virtual currency accounts.

|

Federal Court Case: Online Marketplaces and Virtual Currency in Synthetic Drug Trafficking A federal case involving a transnational criminal organization highlights how dark web marketplaces and virtual currencies are used to distribute synthetic drugs and conceal illicit proceeds. Between 2012 and 2017, Banmeet Singh led a transnational criminal organization responsible for distributing bulk quantities of illicit drugs, including fentanyl, across Europe and North America. Singh arranged the sale of drugs through accounts on dark web marketplaces such as Silk Road and Alpha Bay. Customers then paid for their purchases by transferring virtual currency. Singh and his co-conspirators also used wire transfers and cash shipments to conceal and move millions of dollars in drug proceeds. Singh shipped the drugs from Europe to his co-conspirators at distribution cells he controlled across the U.S., including in Ohio, Florida, and Washington. Singh was indicted on October 17, 2018, and extradited from the U.K. to the U.S. in 2023. He pled guilty to Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess with Intent to Distribute Controlled Substances (21 U.S.C. § 846) and Conspiracy to Commit Money Laundering (18 U.S.C. § 1956(h)). He was sentenced to 5 years imprisonment and forfeited approximately $150 million in virtual currency from drug proceeds, according to the DOJ press release. The charges described above are not exhaustive and do not represent a comprehensive overview of the case. We highlighted aspects of the case that are most relevant to our work. For more information on this case, see U.S. v. Singh (2:18-cr-00216-ALM) U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio (Eastern Division). |

Source: GAO presentation of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑26‑107918

Our investigative work also identified purported sellers on online marketplaces who requested virtual currency as payment for synthetic drugs. See figure 6 for an example of our undercover communication with a purported drug trafficker who requested payment in virtual currency. We plan to refer potential drug trafficking to DEA for follow-up as appropriate.

Figure 6: GAO Undercover Communication with Purported Drug Trafficker Seeking Payment in Virtual Currency

Laundering Proceeds from the Sale of Synthetic Drugs

How do TCOs launder the proceeds from synthetic drug sales?

TCOs use methods such as bulk cash smuggling, funnel accounts, wire transfers, trade-based money laundering, and virtual currency to launder proceeds from synthetic drugs sales.[59] Increasingly, TCOs are outsourcing money laundering to professional money-laundering networks, including Chinese money laundering networks (CMLN) due in part to their reliability and access to the U.S. financial system, as discussed in detail below.[60] Money laundering methods do not necessarily vary by drug type, according to IRS officials. IRS officials said TCOs tend to choose methods based on their own organization and location.

Bulk cash smuggling involves moving physical currency across an international border, often to be deposited in a financial institution in another country. TCOs favor bulk-cash smuggling to repatriate their illicit funds from or move funds into the U.S., according to Treasury’s 2024 National Money-Laundering Risk Assessment.[61] They move bulk cash across the U.S.-Mexico border using air transport, armored car services, privately owned vehicles, and commercial tractor-trailers, according to FinCEN’s recent alert.[62] FinCEN noted that when moving bulk cash into the U.S., TCOs may deposit the funds into U.S. depository accounts owned by Mexico-based businesses or wire them through money services businesses.

Funnel accounts are bank accounts used to collect deposits from various locations. Multiple individuals deposit the cash into a bank account available to other members of the criminal network in another part of the country. The depositors may be individuals outside the organization who are compensated for transferring the funds. Funnel accounts remain a key tool for moving funds across the Mexican border, according to Treasury’s 2024 National Money-Laundering Risk Assessment.

Trade-based money laundering relies on trade transactions to disguise the movement of illicit funds. TCOs may submit false invoices on import and export documentation that misrepresent the price, quantity, or type of goods involved. They then sell the goods for their real value in local currency in the importing country, laundering the difference between the invoiced and actual amount. Other schemes can involve merchants who, wittingly or not, accept payment in funds derived from illicit activity in exchange for exports of goods.

Virtual currencies can be used to launder drug proceeds. Brokers may accept bulk cash in exchange for transferring an equivalent sum in virtual currency to a digital wallet owned by the TCO, according to DEA’s 2025 National Drug Threat Assessment.

Treasury’s 2024 National Money-Laundering Risk Assessment indicated that virtual currency is used far less frequently for money laundering than cash and more traditional methods. A stakeholder knowledgeable about transnational crime we interviewed said TCOs prefer cash because it is more commonly used to buy goods such as vehicles, gas, weapons, and ammunition, especially in Mexico. However, U.S. law enforcement agencies have detected an increase in the use of virtual currency to launder criminal proceeds.

Professional money laundering organizations are third-party specialists that help launder illicit funds for a fee. They can be professional criminal networks or individuals employed in legitimate professional services—such as lawyers, accountants, or arts and antiquities dealers—who knowingly help launder criminal proceeds. They may pick up and transport drug proceeds and then deposit them into the banking system or transfer them elsewhere. Treasury’s 2024 risk assessment reports that TCOs are increasingly using professional money laundering organizations, especially CMLNs.

What are the characteristics of Chinese money laundering networks and why do TCOs use them?

According to law enforcement officials, CMLNs use underground-banking channels, virtual currency, and traditional laundering methods within banking systems to convert, move, and obscure illicit proceeds for a fee. CMLNs are largely decentralized, relying on a network of Chinese nationals living in the U.S., Mexico, and China to sell U.S. dollars to Chinese citizens seeking to move money offshore. These citizens seek such services to circumvent China’s capital flight laws, which restrict transfers of large sums abroad.[63]

TCOs are increasingly using CMLNs in part because their laundering schemes involve fewer interactions with the formal banking system and at a lower cost than other organizations, according to law enforcement officials we interviewed. According to FinCEN, CMLNs are typically able to offer lower rates than other money laundering organizations because most CMLN revenue comes from selling the illicit cash to Chinese citizens at a high rate. TCOs also use CMLNs, in part, due to the speed and effectiveness of their money laundering operations and their willingness to absorb financial losses and assume risks, according to FinCEN.

In a 2024 congressional hearing, a HSI official noted that in fiscal year 2023, many of the roughly 600 fentanyl-related cases connected to China involved CMLNs.[64] According to DOJ officials we interviewed, Colombian money launderers in New York once dominated the market, using traditional laundering schemes and charging higher commissions for the amount laundered. CMLNs offer lower-risk schemes and sometimes use the laundered money for other operations, allowing them to offer lower commission and dominate the market.

Below, we provide illustrative examples of schemes CMLNs may use in their money laundering operations; such schemes are not necessarily sequential.

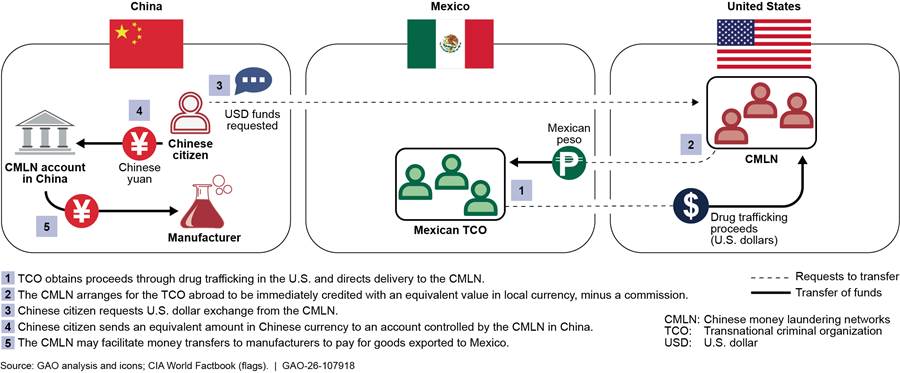

Some CMLNs use schemes that involve underground banking mechanisms that may bypass some aspects of formal banking channels and avoid the need to physically move currency across borders. One such process, known as a “mirror transaction,” is illustrated in figure 7. Based on our prior reports and review of FinCEN and DEA reports, an example of a mirror transaction involving CMLNs could work as follows (in practice, this may involve additional parties and steps):[65]

· A TCO delivers proceeds from synthetic drug trafficking in bulk U.S. dollars to a CMLN member in the U.S.

· The CMLN immediately credits the TCO’s counterpart abroad (for example, in Mexico) with an equivalent value in local currency, minus a commission. This is a “mirror transaction” in which funds do not cross borders.

· Subsequently, the CMLN sells the U.S. dollars to a Chinese citizen to use for expenses in the U.S., such as real estate or other transactions restricted by China’s capital flight laws.

· Those Chinese citizens transfer an equivalent amount from their Chinese bank accounts to the CMLN’s bank account in China.

· According to DOJ officials, the CMLN may use the funds in these bank accounts to purchase goods exported to Mexico, including precursor chemicals, for trade-based money laundering.

Mirror transactions exchange equivalent funds in different countries without crossing borders, helping obscure the origin of illicit drug proceeds.

This illicit finance system provides benefits for various parties: liquidity for CMLNs, evasion of China’s capital controls for clients, and concealment of the criminal origins of drug proceeds for TCOs.[66]

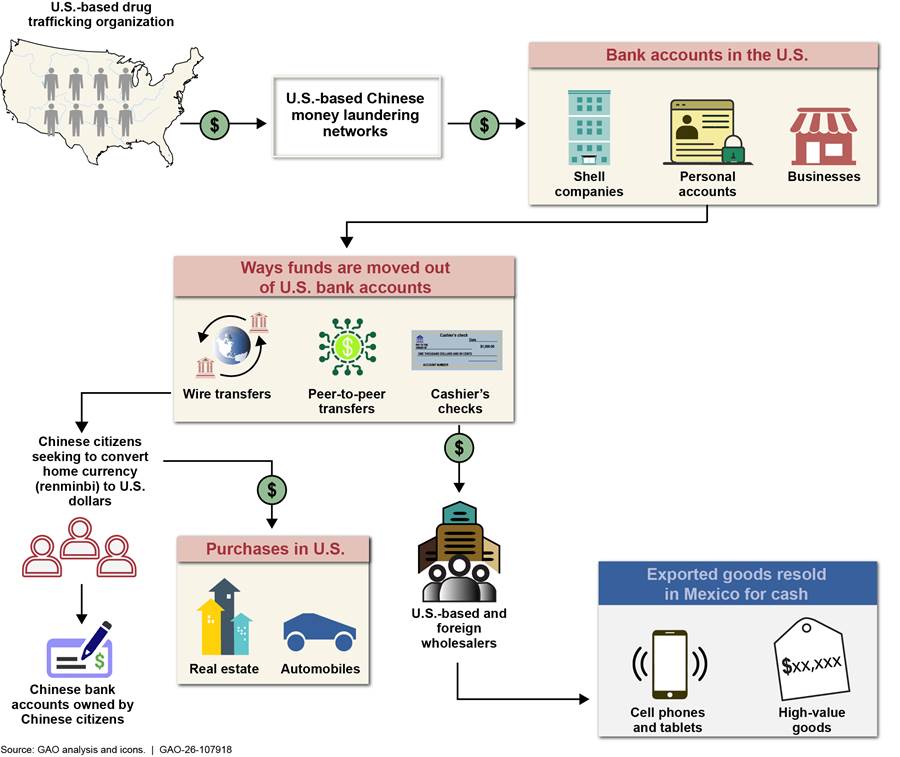

CMLNs may also use schemes that involve traditional money laundering methods within the banking system. For example, HSI has reported that CMLNs may recruit Chinese nationals living in the U.S. to open domestic bank accounts, often supplying them with counterfeit Chinese passports to do so. These accounts operate as funnel accounts: couriers deposit funds that are quickly withdrawn and used to purchase cashier’s checks made out to third parties not associated with the account.

According to an April 2025 FinCEN report, suspicious activity report filings revealed networks of suspected CMLN couriers, mostly Chinese passport holders, engaging in suspicious activity such as large cash deposits, cashier’s check purchases, and peer-to-peer payments.[67] These transactions often involved personal or business accounts tied to seemingly legitimate businesses like restaurants and salons, as well as to suspected shell companies used for potential laundering. CMLNs have also transferred funds from their bank accounts directly to Mexico-based financial institutions. In June 2025, FinCEN prohibited certain fund transfers to three such financial institutions, citing their role in laundering money for TCOs.[68]

Another method CMLNs might use is trade-based money laundering. For example, in a 2024 congressional hearing, a HSI official noted CMLNs recruit individuals to purchase high-value electronics and luxury goods in the U.S. CMLNs then export the merchandise to China and sell it for a profit.[69] The resulting funds can then be used to purchase real estate, precursor chemicals, or other assets—or re-laundered using additional methods.

CMLNs also leverage U.S. banks to facilitate laundering, using funnel accounts, shell companies, and traditional banking products (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Examples of How Chinese Money Laundering Networks Launder Drug Proceeds Through U.S. Banks

In June 2024, DOJ announced an indictment charging individuals with laundering drug proceeds through CMLNs using schemes such as the exchange of luxury goods and virtual currencies, as well as traditional banking methods, such as cashier’s checks (see text box).

|

Federal Court Case: Chinese Money Laundering Networks A 2023 federal indictment and 2024 superseding indictment in Los Angeles illustrates how Chinese money laundering networks help transnational drug traffickers clean and repatriate drug proceeds to Mexico through underground financial networks. The indictment charges that members of the Sinaloa cartel exported large quantities of illicit drugs, including cocaine and methamphetamine, from Mexico to coconspirators in the U.S. Between 2019 and 2023, the defendants allegedly distributed and sold the illicit drugs in California and elsewhere and laundered the proceeds by purchasing cryptocurrency, structuring assets to avoid federal reporting requirements, and using Chinese money laundering networks. For example, defendant Hang Su was charged with transporting bags of bulk cash from a codefendant who bought and sold U.S. currency in exchange for Chinese currency on the black market. According to the Department of Justice, more than $50 million in drug proceeds flowed between the Sinaloa Cartel members and Chinese underground money exchanges during the conspiracy. The defendants were indicted on October 26, 2023, and charged with various criminal violations, including Conspiracy to Aid and Abet the Distribution of Cocaine and Methamphetamine (21 U.S.C. § 846), Conspiracy to Launder Monetary Instruments (18 U.S.C. § 1956(h)), and Conspiracy to Operate an Unlicensed Money Transmitting Business (18 U.S.C. § 371). On June 27, 2025, defendant Hang Su plead guilty to Conspiracy to Operate an Unlicensed Money Transmitting Business and is awaiting sentencing. In August 2025, defendants Jiayong Yu, Xuanyi Mu, Shou Yang, and Oscar Eduardo Mayorga pleaded guilty to Conspiracy to Operate an Unlicensed Money Transmitting Business and are awaiting sentencing. In September 2025, Diego Acosta Ovalle pleaded guilty to Conspiracy to Operate an Unlicensed Money Transmitting Business and is awaiting sentencing. Numerous other defendants pleaded guilty to various charges, including conspiracy to launder monetary instruments and possession with intent to distribute certain controlled substances, in the case and are awaiting sentencing. The case remains on going as of December 1, 2025. The charges described above are not exhaustive and do not represent a comprehensive overview of the case. We highlighted aspects of the indictments that are most relevant to our work. Statements in an indictment are merely allegations. All defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law (defendant Hang Su pleaded guilty to the charge noted above). For more information on this case, see U.S. v. Martinez-Reyes et al. (2:23-cr-524), U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. |

Source: GAO presentation of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑26‑107918

How has FinCEN helped financial institutions identify and report money laundering related to synthetic drugs?

FinCEN issued advisories in 2019, 2024, and 2025 to assist financial institutions in identifying and reporting suspicious activity related to synthetic drug trafficking and the use of CMLNs. Additionally, FinCEN recently reviewed suspicious activity reports from 2020 through 2024 and identified related money laundering trends, including suspected CMLN activity.[70] Treasury’s 2024 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment noted that CMLNs are becoming one of the most significant money laundering threat actors to the U.S. financial system. Their use of mirror transactions can make it more difficult for U.S. law enforcement to investigate. FinCEN’s advisories are designed to help financial institutions understand how illicit synthetic drug operations are financed and support them in filing useful suspicious activity reports to FinCEN for law enforcement.

FinCEN, through its Advisory Program, communicates money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit finance threats and vulnerabilities to the U.S. financial system. Financial institutions may use this information in part to support their suspicious activity monitoring systems. These advisories can cover a range of illicit finance threats, financial typologies, “red flag” indicators, and other guidance developed in collaboration with law enforcement agencies. According to FinCEN officials, the advisories are intended to help institutions better understand illicit finance typologies and indicators of potentially suspicious activity to report to FinCEN as part of their anti-money laundering programs and Bank Secrecy Act requirements. Its 2019 and 2024 advisories highlight typologies and red flags in the illicit fentanyl and synthetic opioid supply chain to help financial institutions detect, prevent, and report suspicious activity. Its 2025 advisory highlights typologies and red flags related to TCO use of CMLNs (see table 1).

|

Date |

Advisory |

Description |

|

Advisory related to drug trafficking |

||

|

August 21, 2019 |

Advisory to Financial Institutions on Illicit Financial Schemes and Methods Related to the Trafficking of Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Opioids FIN-2019-A006 |

Alerts financial institutions to financial typologies and red flags linked to the trafficking of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Provides examples of the use of money services businesses, online payment processors, darknet marketplaces, and convertible virtual currency by traffickers. |

|

Advisory related to supply chains |

||

|

June 20, 2024 |

Supplemental Advisory on the Procurement of Precursor Chemicals and Manufacturing Equipment Used for the Synthesis of Illicit Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Opioids FIN-2024-A002 |

Supplements the 2019 advisory to reflect evolving supply chain trends. Focuses on procurement of precursor chemicals, pill presses, and die molds. Identified red flags for financial institutions related to customer and counterparty profiles, and transactions. |

|

Advisory related to Chinese money laundering networks (CMLN) |

||

|

August 28, 2025 |

FinCEN Advisory on the Use of Chinese Money Laundering Networks by Mexico-Based Transnational Criminal Organizations to Launder Illicit Proceeds FIN-2025-A003 |

Provides an overview of CMLNs and their connection to transnational criminal organizations. Discusses financial typologies associated with CMLNs, such as mirror transactions and trade-based money laundering. Highlights red flag indicators related to CMLN-affiliated money mules and trade-based money laundering schemes. |

Source: GAO analysis of Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Information. | GAO‑26‑107918

The 2019 and 2024 advisories reference press releases from prior cases along with customer and counterparty profiles and transactional red flags.[71] The 2025 advisory references CMLN-affiliated money mules and

|

“Red Flags” for Fentanyl Supply Chain Activity In 2024, FinCEN advised financial institutions to watch for the following indicators of illicit fentanyl supply chain activity: Customer and Counterparty Profiles · Customer or counterparty has previous drug-related convictions or is a suspicious chemical or pharmaceutical entity in China and shows signs of possible illicit shell company activity. · Customer or counterparty operates on an e-commerce or darknet marketplace that advertises precursor chemicals or manufacturing equipment for fentanyl. · Customer is a Mexican company that reportedly imports fentanyl precursor chemicals and manufacturing equipment without appropriate licenses or registrations. Transaction-Related Indicators · Customer sends low-dollar or virtual currency payments with no clear legitimate purpose to beneficiaries involved in chemical or pharmaceutical industries in China. · Entity is a Mexico-based or China-based entity in an unrelated industry that transacts across borders with a chemical or pharmaceutical firm in Mexico or China. · Customer is a Mexican company with no apparent link to chemical or pharmaceutical industries and engages in transactions involving fentanyl precursors or associated manufacturing equipment. Source: GAO analysis of Financial Crime Enforcement Network (FinCEN) information. | GAO‑26‑107918 |

trade-based money laundering schemes and included a list of red flags to help financial institutions detect, prevent, and report related suspicious activity. Examples of red flags include the following:

· A customer, especially one who presented a Chinese passport as identification, regularly receives funds not commensurate with the reported occupation or income.

· A customer presents a Chinese passport and a visa that contain the same photograph despite being allegedly issued years apart.

· A customer’s account, especially that of a Chinese national, receives numerous transfers or deposits and has a significant number of withdrawals or transfers, none of which appear to be related to customer’s stated expected activity.

· A business owned by a Chinese national regularly receives deposits from online marketplaces, but rarely, or never, engages in transactions that indicate the purchase of goods to maintain inventory.

· A small U.S.-based business in the electronics or real estate industry receives wires from Mexico, China, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates and has no known nexus to these countries.

· A business that sells electronics or other luxury goods has income that is not commensurate with the size and scale of the business.

According to members of the Independent Community Bankers of America, a banking industry trade group, FinCEN’s red flags and case examples help financial institutions improve their monitoring activities. Members of the American Bankers Association similarly noted that advisories provide useful information on priorities, including areas of critical concern.

FinCEN’s advisories also requested that filers reference the advisories in their suspicious activity reports through a unique key term for each advisory. According to FinCEN officials, the use of advisory key terms allows FinCEN and its law enforcement partners to search and monitor suspicious activity reports filed in response to the advisories for trend analysis and to support new or ongoing investigations.

What do recent suspicious activity report filings reveal about money laundering related to synthetic drug trafficking?

Our analysis of suspicious activity report data from August 2019 through March 2025 found that 86 percent of reports filed in response to FinCEN’s 2019 and 2024 advisories referenced fentanyl, methamphetamine, or other synthetic drugs.[72] Among the total 1,457 filings analyzed, 48 percent of the suspicious activities occurred at depository institutions and 51 percent at money services businesses. Additionally, 40 percent of the 1,457 filings in our analysis referenced suspicious electronic funds transfers or wire transfers, with such references increasing from 24 filings in 2020 to 293 in 2024.

In an April 2025 report, FinCEN’s analysis of 2024 Bank Secrecy Act data found that the fentanyl supply chain leverages U.S. financial institutions.[73] The report also found that money laundering schemes range from simple funds transfers to complex schemes, such as those involving CMLNs. According to FinCEN officials we interviewed—and consistent with findings we reviewed in FinCEN documents—CMLNs remain prominent among global professional money laundering groups. In an August 2025 report, FinCEN analyzed Bank Secrecy Act data from 2020 through 2024 and noted that banks filed the majority of potentially CMLN-related reports, with depository institutions filing 85 percent of the reports and money services businesses filing 9 percent.[74] FinCEN also found that the most common suspicious activity involved U.S.-based Chinese nationals making large cash deposits, with 33 percent of reports referencing these cash deposit transactions.

Agency Coordination, Information-Sharing Efforts, and Recent Policy Changes

How do federal agencies coordinate to combat synthetic drug trafficking and related money laundering?

Federal agencies coordinate and share information with each other and with state, local, and international partners through task forces, working and advisory groups, colocation, and other information-sharing channels, as shown in table 2.[75] These mechanisms are intended to help agencies share resources and expertise, deconflict investigations, and combine unique authorities in combating drug trafficking and money laundering organizations.[76]

Table 2: Examples of Interagency Efforts That Address Synthetic Drug Trafficking and Illicit Financing

|

Interagency effort |

Description |

Participating entitiesa |

|

Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group |

Public-private partnership led by FinCEN that convenes industry, regulator, and law enforcement representatives for discussions regarding administration of the Bank Secrecy Act, including how recordkeeping and reporting requirements can be improved to enhance utility to law enforcement and national security. |

DOJ Treasury USPIS State and local partners Private sector partners |

|

CBP National Targeting Center |

Uses data and law enforcement intelligence to identify international cargo shipments and travelers that may be connected to transnational criminal activities, including narcotics smuggling, human trafficking, and money laundering, and shares data and intelligence with law enforcement in support of investigations. |

DOJ DHS Treasury Department of State USPIS Private sector partners International partners |

|

DEA Special Operations Division |

Multiagency operational coordination center led by DEA aimed at dismantling drug trafficking and money laundering organizations by attacking their command, control, and communications. |

DOJ DHS Treasury USPIS Intelligence Community partners State, local, and international partners |

|

El Dorado Task Force |

Financial crimes task force led by HSI to disrupt and dismantle transnational money laundering organizations by conducting proactive investigations, engaging private sector partners, and leveraging federal and state laws and regulations. |

DOJ DHS Treasury State and local partners Private sector partners |

|

FinCEN Exchange |

Public-private information-sharing partnership led by FinCEN to enhance financial institutions’ ability to identify and report information that supports law enforcement in disrupting money laundering and other financial crimes. |

Treasury National Security agencies Federal, state, and local partners Private sector partners |

|

Five Eyes Law Enforcement Group |

Coalition of law enforcement agencies from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the U.S., led by the National Crime Agency.b Shares criminal intelligence and collaborates on operations to combat transnational crime, including drug trafficking and money laundering. |

DOJ DHS Treasury International partners |

|

Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement |

FBI-led team that coordinates efforts to detect, disrupt, and dismantle major criminal enterprises and supply chains reliant on the darknet for trafficking opioids and other illicit narcotics. |

DOJ DHS Treasury USPIS State, local, and international partners |

|

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forcesc |

Former DOJ component that used a prosecutor-led, multiagency approach to lead coordinated investigations of transnational organized crime, money laundering, and major drug trafficking networks. |

DOJ DHS Treasury Department of State USPIS State and local partners |

|

Synthetic Drugs Interagency Coordination Group |

ONDCP-led group that aims to exchange information and synchronize U.S. government efforts to combat synthetic drug manufacturing and trafficking. |

DOJ DHS Department of State ONDCP Embassy Mexico City Other U.S. law enforcement representatives |

|

Trade Transparency Unit |

International effort led by HSI to combat trade-based money laundering. As of August 2025, 19 partner countries have established units with HSI assistance. The units collaborate and exchange trade data to better identify anomalies that may indicate trade-based money laundering, such as discrepancies in the reported value of imported goods. |

DHS International partners |

CBP: Customs and Border Protection

DEA: Drug Enforcement Administration

DHS: Department of Homeland Security

DOJ: Department of Justice

FBI: Federal Bureau of Investigation

FinCEN: Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

HSI: Homeland Security Investigations

ICE: Immigration and Customs Enforcement

ONDCP: Office of National Drug Control Policy

Treasury: Department of the Treasury

USPIS: U.S. Postal Inspection Service

Source: GAO analysis of agency information. | GAO‑26‑107918

aThis list of participating entities is not exhaustive. Federal agencies shown are limited to those we interviewed (see app. I) and the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

bLeadership of the Five Eyes Law Enforcement Group rotates among member agencies every 2 years. The United Kingdom’s National Crime Agency formally assumed leadership from ICE-HSI in July 2025.

cIn accordance with the Deputy Attorney General’s July 23, 2025, memorandum entitled, “Transitioning [Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces] Resources for Homeland Security Task Forces,” the program concluded its investigative and prosecutorial operations and began the closure or transfer of executive functions as of July 25, 2025. On September 17, 2025, the Attorney General signed the Department of Justice’s Agency Reduction in Force and Reorganization Plan that terminated Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces and distributed select functions and resources among the FBI, DOJs Justice Management Division, and the DHS to support the establishment of Homeland Security Task Forces pursuant to Executive Order 14159.

Task Forces

A task force is a group of agencies formed to address a specific issue or threat, often by sharing resources and information. It is one of the primary ways law enforcement agencies coordinate with one another and with state, local, or international partners on synthetic drug trafficking and money laundering investigations. The distinct mission of a task force generally determines the type and number of agencies involved and its geographic scope. For example, the FBI’s Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team includes task forces comprised of several federal agencies that coordinate global operations targeting criminal activity on darknet marketplaces. See text box below for an example of a case involving the Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team.

|

Federal Court Case: Operation SpecTor An indictment against defendants Holly Adams and Devlin Hosner charged that they sold tens of thousands of counterfeit oxycodone pills containing fentanyl on darknet marketplaces, such as Darkode and ToRReZ, between 2021 and 2022. The defendants allegedly shipped the drugs and contraband to buyers across the U.S., using the U.S. Postal Service, United Parcel Service, and other means and received more than $800,000 in cryptocurrency. In March 2022, federal law enforcement officers seized more than 10,000 counterfeit oxycodone pills and approximately 60 grams of methamphetamine from the defendants’ residence. The Department of Justice reported that this case was part of more than 100 federal operations and prosecutions under Operation SpecTor. Led by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement team, Operation SpecTor is the largest international operation against darknet trafficking of fentanyl and opioids. From 2021 through 2023, the operation resulted in 288 arrests, the seizure of more than 850 kilograms of drugs (including 64 kilograms of fentanyl-related narcotics), and more than $50 million in cash and virtual currencies. It involved federal law enforcement from the Drug Enforcement Administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement-Homeland Security Investigations, Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation, with additional support from state, local, and international partners. Defendants Adams and Hosner were indicted on May 12, 2022, and charged with Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess with Intent to Distribute Fentanyl and Methamphetamine (21 U.S.C. §§ 846, 841(a)(1)) and Conspiracy to Launder Money (18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(1)(B)(i) and (h)). Defendant Holly Adams pleaded guilty to both counts and was sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment. In December 2025, defendant Devlin Hosner pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute and possess with intent to distribute certain controlled substances and is awaiting sentencing. For more information on this case, see U.S. v. Adams et al. (2:22-cr-00100-JAM), U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California. |

Source: GAO presentation of Department of Justice information. | GAO‑26‑107918

According to the Financial Action Task Force, task forces can be well-suited for large and complex investigations as they are designed to facilitate information sharing and allow agencies to leverage one another’s expertise and legal authorities.[77] For example, Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces used a prosecutor-led, multiagency approach to coordinate investigations. It included representatives from DOJ, DHS, Treasury, USPS, Department of State, and state and local law enforcement agencies.[78]

DOJ officials said new task forces were recently established in accordance with Executive Order 14159, Protecting the American People Against Invasion, signed January 20, 2025. The order required DOJ and DHS to jointly established Homeland Security Task Forces in all 50 states to end the presence of cartels and TCOs in the U.S. DHS officials said these new task forces would leverage the existing structures and capabilities of Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces and other interagency task forces to expand the counter-drug mission of the Homeland Security Task Forces in accordance with the executive order. Additionally, FBI officials said these task forces are being formed to increase collaboration with domestic law enforcement and Intelligence Community partners to combat synthetic drug trafficking and foreign terrorist organizations generally. According to DOJ officials, as of November 2025, the Homeland Security Task Forces National Command Center is operational.

Task forces can also help prevent duplicative investigations. For example, DOJ, DHS, USPS, and state and local agencies used an El Dorado Task Force to coordinate their investigation into a New York-based drug trafficking network. According to DOJ, the joint investigation resulted in four arrests in October 2023 and the seizure of approximately 24 kilograms of suspected fentanyl powder, more than 200,000 suspected fentanyl pills, and four commercial pill presses.[79] In cases such as this, agencies are able to deconflict law enforcement activities like surveillance or executing arrest warrants, reducing duplication and overlap.

Working and Advisory Groups

Working and advisory groups are formal mechanisms through which agencies and international partners or private sector partners collaborate to address a specific issue or shared goal.[80] Interagency working groups allow agencies with different authorities and resources to address common concerns, identify resource and capability gaps, and leverage resources, according to the Office of National Drug Control Policy.[81] Agencies use these groups to synchronize investigations, share intelligence and data, and build productive relationships over time.

Officials from several agencies told us that these groups are important to their efforts to combat synthetic drug trafficking and related money laundering. They noted that group goals are dynamic and can change to align with evolving criminal networks and strategies:

· Department of State officials told us that the Synthetic Drugs Interagency Coordination Group, which focuses on combating the manufacturing and trafficking of all synthetic drugs, was initially established in 2015 as the U.S. Embassy Interagency Heroin-Fentanyl Working Group in Mexico City. Its goal was to synchronize U.S. and Mexican investigative efforts to combat heroin and fentanyl manufacturing and trafficking.[82]

· FBI officials told us that the Five Eyes Law Enforcement Group recently prioritized addressing CMLNs due to their significant role in illicit finance related to drug trafficking.

· The

Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group provides an avenue for FinCEN to communicate

regularly with private-sector representatives on how Bank Secrecy Act reports

support law enforcement investigations and how reporting could be improved.[83] According to a June 18, 2025,

Treasury press release, FinCEN recently expanded the group’s membership to

increase the number of small community banks.

Colocation

Colocation is the practice of housing one or more entities, often in one location, to collaborate on shared mission projects. Agencies use colocated centers, divisions, and teams to deconflict and leverage resources with other law enforcement agencies, international partners, and the private sector. Ten components from DHS, DOJ, Treasury, and USPS reported using colocation to coordinate and share information, intelligence, and data to combat transnational criminal organizations and illicit finance.

For example, officials said CBP’s National Targeting Center houses personnel from five components of the agencies in our review and more than a dozen international and industry partners. The center aims to identify high-risk individuals and cargo prior to their arrival in the U.S. and to support related criminal investigations, including drug smuggling and money laundering. It operates through various divisions, units, and teams, such as the Executive Cargo Division, Counter Transnational Organized Crime Unit, and Industry and Partnership Alliance team.

Additionally, DEA leads the Special Operations Division, which is overseen by officials from DEA, FBI, and HSI, according to DEA officials. Officials said over 36 federal, local, and international agencies collaborate in the division to identify and dismantle international and domestic drug trafficking and money laundering organizations by targeting their command, control, and communications. DEA officials said colocation fosters open lines of communication, which they described as crucial to relationships between the agencies. We previously reported on interagency efforts to combat synthetic drugs at the National Targeting Center and to address illicit finance at the Special Operations Division.[84]

What other mechanisms do federal agencies use to share information?

Federal agencies share information with each other, the private sector, and state and local law enforcement through a variety of channels, including memorandums, liaison information reports, programs, and events. They also share intelligence and data with each other and international partners to identify, disrupt, and dismantle drug trafficking organizations and illicit financial activity.

For example, DHS officials told us the Trade Transparency Unit program, which is a data sharing program, supports their work combating illicit finance, including money laundering related to synthetic drug trafficking. Trade Transparency Units are the U.S. government’s primary partnership effort for sharing trade data to address trade-based money laundering.[85] They serve as a means for agencies in different countries to jointly analyze trade data and identify anomalies that may indicate laundering activity. FinCEN also reported sharing financial intelligence with U.S. law enforcement agencies and FinCEN’s financial intelligence unit foreign counterparts. For example, FinCEN uses memorandums of understanding that permit law enforcement agencies access to Bank Secrecy Act information.[86]

FBI officials reported using liaison information reports to share impactful and actionable content on issues relevant to the private sector. For example, officials said several FBI field offices produced reports in 2024 on synthetic drug trafficking or money laundering for private companies in the healthcare, agriculture, and transportation sectors. FBI officials told us they also share intelligence with other agencies to combat synthetic drug trafficking. For example, they regularly share intelligence with the Department of Defense on the flow of illicit drugs, including fentanyl, via air and maritime shipping routes, which has resulted in the seizure of both illicit drugs and illicit funds used to purchase them.

FinCEN has used an information sharing public-private partnership program, known as the FinCEN Exchange, for identifying illicit financial activity and to build relationships with and between financial institutions and law enforcement. In 2024, it held 10 informational exchange events in U.S. cities highly affected by the opioid epidemic as part of its Promoting Regional Outreach to Educate Communities on the Threat of Fentanyl series. During these events, representatives from financial institutions and law enforcement agencies discussed how to identify and track illicit financial flows tied to fentanyl-related activity. One participating financial institution representative described the exchange as informative and said it enhanced their institution’s monitoring processes for fentanyl-related and broader drug trafficking activity. DOJ officials said the exchanges help to build strong partnerships with the private sector.